Graves' orbitopathy (GO) is a disfiguring autoimmune condition, which can sometimes cause blindness (1). The disease has profound effects on quality of life (2), psychological health (3), and socioeconomic status (4). Progress in understanding and treating this disease has been slow. However, recent advances include delineation of plausible immunological mechanisms (5), development of an animal model (6), and publication of randomized studies defining the role and limitations of intravenous steroids (7), rituximab (8,9), and selenium (10). Yet, some of this knowledge remains to be translated into improvement in clinical care. Access of patients to specialist treatments is patchy and seems to depend on chance rather than clinical need (11). In 2009, 84 international, national, scientific, and patient-led organizations signed the Amsterdam Declaration for people with Thyroid Eye Disease (12). Signatories pledged to “improve the existing research networks and develop further international collaborative research.”

Patient and public involvement (PPI) is increasingly recognized as an important and positive influence in research (13). Research funding organizations often require that applicants provide evidence of PPI in research proposals. In 2012, the first ever PPI event for inflammatory ocular diseases was organized by the Moorfields National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre in London, United Kingdom, overseen by the James Lind Alliance (14). This resulted in setting priorities for future research in inflammatory ocular conditions (15).

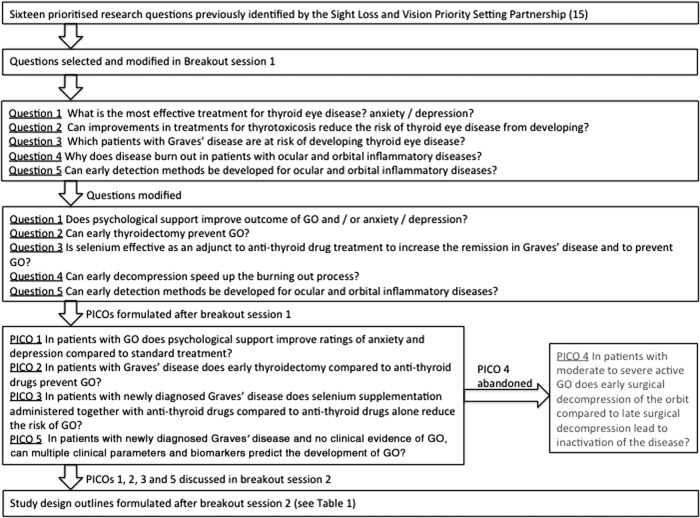

Here, we share our further experience with PPI leading to refinement of the priorities for future research, and translation into answerable research questions and study design outlines, through a two-day event. The event was planned by a committee representing professional and patient-led organizations (16,17). It was publicized in the media (newspaper, municipal Web sites on events, newsletters, general practitioner surgeries, patient organizations, professional organizations). Attendees registered as members of the public if they were not patients with thyroid disease or health professionals. Day 1 was aimed at patients, the public, experts, and professionals. It included an introductory session about GO for patients and the public, patient testimonies about their experience with the disease, and a breakout session into three working groups. Day 2 consisted of a scientific meeting aimed at professionals and six invited expert patients. It included reviews of the pathogenesis and clinical management of GO, highlighting recent advances in these areas. It was followed by a breakout session of three working groups for professionals, experts, and expert patients, allocated to translating the selected research questions formulated in breakout session 1, to study design outlines. The objectives of breakout session 1 were to discuss six questions per group previously set by the Sight Loss and Vision Priority Setting Partnership (15) and select a maximum of two questions per group based on scientific merit and relevance to unmet patient needs (Fig. 1). The chair and co-chair for each group were asked to use the PICO (patient, intervention, comparator, outcome) principle (18) in order to formulate the selected research questions for further elaboration in breakout session 2 on day 2. Groups in breakout session 2 consisted of a chair, co-chair, expert panelists (including two expert patients per group) and professionals. They were asked to discuss and translate the PICO questions of breakout session 1 into study designs.

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram outlining the processes for prioritization and formulation of research questions.

The event was successful in drawing a sizeable (147 on day 1 and 131 on day 2) and diverse audience (public, patients, endocrinologists, ophthalmologists, and basic scientists from 13 different countries), and met the previously set targets for attendance and participant mix by the organizing committee. PPI was achieved as judged by the number of people who attended and the significant influence exerted by patients and the public on selection and direction of potential studies. The outcomes from breakout sessions 1 and 2 are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. The net cost of the meeting (total cost minus registration fees) was £18,000 ($28,300).

Table 1.

Study Design Outlines Proposed

| Study identification | PICO | Study title/aim | Design | Setting/duration of follow-up | Inclusion criteria | Intervention | Assessments | Primary outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | PICO 1: In patients with GO, does psychological support improve ratings of anxiety and depression compared to standard treatment? |

Title: Psychological support in GO Aim: To determine the effect of psychological support on psychological well-being and quality of life |

Prospective, randomized, single blinded |

Setting: Multiple site, tertiary centers Duration of follow-up: 1 year |

Patients with new onset GO, scoring above a predetermined threshold using a tool such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | Formal psychological intervention (such as cognitive behavior therapy) versus standard care | Demographics, history, clinical/ophthalmological assessments (20), questionnaire-based measures of psychological well-being and quality of life (2) at baseline and at the end of the intervention period | Questionnaire-based measures of psychological well-being and quality of life (2) |

| B | PICO 2: In patients with Graves' disease, does early thyroidectomy compared to antithyroid drugs prevent GO? |

Title: Early total thyroid ablation in prevention of GO Aim: To determine whether total thyroid ablation prevents the development of GO |

Prospective, randomized single blind design |

Setting: Multiple site, endocrine clinics with access to tertiary centers Duration of follow-up: 1 year |

Newly diagnosed patients with Graves' disease without GO who are at high risk of developing GO | Total thyroid ablation (21) versus antithyroid drugs | Assessments and follow-up as described in Leo et al. (21) | Rate of new onset of GO |

| C | PICO 3: In patients with newly diagnosed Graves' disease, does selenium supplementation administered together with antithyroid drugs compared to antithyroid drugs alone reduce the risk of GO? |

Title: Prevention of GO with selenium Aim: To determine whether selenium supplements prevent GO |

Prospective, randomized, double-blinded study |

Setting: Multiple site, endocrine clinics with access to tertiary centers Duration of follow-up: 1.5 years |

Newly diagnosed patients with Graves' disease and no GO and low serum selenium | Selenium supplements 200 μg daily with antithyroid drugs versus antithyroid drugs only | Demographics, history, clinical/ophthalmological assessments (20) | Development of GO, and disease-specific quality of life assessments (2) |

| PICO 4: In patients with moderate to severe active GO, does early surgical decompression of the orbit compared to late surgical decompression lead to inactivation of the disease? | Abandoned | |||||||

| D | PICO 5: In patients with newly diagnosed Graves' disease and no clinical evidence of GO, can multiple clinical parameters and biomarkers predict the development of GO? |

Title: Prediction of GO Aim: To determine whether clinical parameters and biomarkers can predict GO in patients with Graves' disease |

Prospective, observational study |

Setting: Multiple site, endocrine clinics with access to tertiary centers Duration of follow-up: 1.5 years |

Newly diagnosed patients with Graves' disease and no GO planned to be treated with antithyroid drugs for 24 months | Establishment of biobank using blood and tear fluid | Demographics, history, clinical/ophthalmological assessments (20) every 6 months. Proteomic, genomic, metabolomics, markers at baseline. | Development of GO over 1.5 years of follow-up and correlation with biomarkers |

PICO, patient, intervention, comparator, outcome; GO, Graves' orbitopathy.

The selection of psychological intervention as one of the priorities was not anticipated by the authors, but clearly this is of great interest to patients and the public, and it has now been documented as an unmet need worthy of future research. What also emerged as a priority was the importance of developing a method for predicting the development of GO with a high degree of accuracy. The number of patients with GO seems to be declining (19), and we anticipate that the emphasis of future interventions will be in prevention. In order to conduct meaningful randomized controlled trials, there is a need to target patients with Graves' disease who have no clinical expression of GO at the time of recruitment but are likely to develop the disease, and such a study was given high priority.

In conclusion, we were able to conduct a successful PPI event on GO, which prioritized 6/16 previously set research questions, and translated them into four outlines of study designs, two of which emerged as highest priorities. Unmet patient needs informed and guided the selection process. This will provide strong evidence of PPI in future bids by the thyroid community for funding these studies, and may be a useful model for PPI in research planning and prioritization for other thyroid diseases.

Acknowledgments

The event was supported financially from grants and donations from the European Thyroid Association, Society for Endocrinology, Biomedical Research Centre, Moorfields Hospital London, Tynesight Trust, Apitope, and RSR Limited. The authors also wish to thank Sir Leonard Fenwick, Chief Executive, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and Frances Blackburn, Head of Nursing, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, for their support.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Perros P, Neoh C, Dickinson J. 2009. Thyroid eye disease BMJ 338:b560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Mourits MP, Gerding MN, Baldeschi L, Kalmann R, Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM. 2001. Interpretation and validity of changes in scores on the Graves' ophthalmopathy quality of life questionnaire (GO-QOL) after different treatments. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 54:391–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahaly GJ, Petrak F, Hardt J, Pitz S, Egle UT. 2005. Psychosocial morbidity of Graves' orbitopathy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 63:395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponto KA, Merkesdal S, Hommel G, Pitz S, Pfeiffer N, Kahaly GJ. 2013. Public health relevance of Graves' orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Smith TJ. 2014. Current concepts in the molecular pathogenesis of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55:1735–1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moshkelgosha S, So PW, Deasy N, Diaz-Cano S, Banga JP. 2013. Cutting edge: retrobulbar inflammation, adipogenesis, and acute orbital congestion in a preclinical female mouse model of Graves' orbitopathy induced by thyrotropin receptor plasmid-in vivo electroporation. Endocrinology 154:3008–3015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartalena L, Krassas GE, Wiersinga W, Marcocci C, Salvi M, Daumerie C, Bournaud C, Stahl M, Sassi L, Veronesi G, Azzolini C, Boboridis KG, Mourits MP, Soeters MR, Baldeschi L, Nardi M, Currò N, Boschi A, Bernard M, von Arx G. 2012. Efficacy and safety of three different cumulative doses of intravenous methylprednisolone for moderate to severe and active Graves' orbitopathy. European Group on Graves' Orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:4454–4463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salvi M, Vannucchi G, Currò N, Campi I, Covelli D, Dazzi D, Simonetta S, Guastella C, Pignataro L, Avignone S, Beck-Peccoz P. 2015. Efficacy of B-cell targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with active moderate to severe graves' orbitopathy: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100:422–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stan MN, Garrity JA, Carranza Leon BG, Prabin T, Bradley EA, Bahn RS. 2015. Randomized controlled trial of rituximab in patients with Graves' orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100:432–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcocci C, Kahaly GJ, Krassas GE, Bartalena L, Prummel M, Stahl M, Altea MA, Nardi M, Pitz S, Boboridis K, Sivelli P, von Arx G, Mourits MP, Baldeschi L, Bencivelli W, Wiersinga W. 2011. Selenium and the course of mild Graves' orbitopathy. N Engl J Med 364:1920–1931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perros P, Chandler T, Dayan CM, Dickinson AJ, Foley P, Hickey J, Macewen CJ, Lazarus JH, McLaren J, Rose GE, Uddin JM, Vaidya B. 2012. Orbital decompression for Graves' orbitopathy in England. Eye (Lond) 26:434–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perros P, Wiersinga WM. 2010. The Amsterdam Declaration on Graves' orbitopathy. Thyroid 20:245–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, Suleman R. 2014. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect 17:637–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fight for sight. Available at: www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Sight-Loss-and-Vision-Priority-Setting-Partnership-FINAL-REPORT.pdf (accessed October7, 2015)

- 15.Smith HB, Porteous C, Bunce C, Bonstein K, Hickey J, Dayan CM, Adams G, Rose GE, Ezra DG. 2014. Description and evaluation of the first national patient and public involvement day for thyroid eye disease in the United Kingdom. Thyroid 24:1400–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.TEAMED. Available at: www.btf-thyroid.org/index.php/campaigns/teamed (accessed October7, 2015)

- 17.European Group on Graves' Orbitopathy. Available at: www.eugogo.eu (accessed October7, 2015)

- 18.Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB. 1997. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. Churchill Livingston, New York [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perros P, Zarkovic M, Azzolini C, Ayvaz G, Baldeschi L, Bartalena L, Boschi A, Bournaud C, Brix TH, Covelli D, Ćirić S, Daumerie C, Eckstein A, Fichter N, Führer D, Hegedüs L, Kahaly GJ, Konuk O, Lareida J, Lazarus J, Leo M, Mathiopoulou L, Menconi F, Morris D, Okosieme O, Orgiazzi J, Pitz S, Salvi M, Vardanian-Vartin C, Wiersinga W, Bernard M, Clarke L. Currò N, Dayan C, Dickinson J, Knežević M, Lane C, Marcocci C, Marinò M, Möller L, Nardi M, Neoh C, Simon Pearce S, von Arx G, Törüner FB. 2015. PREGO (Presentation of Graves' Orbitopathy) study: changes in referral patterns to European Group On Graves' Orbitopathy (EUGOGO) centres over the period from 2000 to 2012. Br J Ophthalmol 2015. May 7 [Epub ahead of print]; pii: . doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartalena L, Baldeschi L, Dickinson AJ, Eckstein A, Kendall-Taylor P, Marcocci C, Mourits MP, Perros P, Boboridis K, Boschi A, Currò N, Daumerie C, Kahaly GJ, Krassas G, Lane CM, Lazarus JH, Marinò M, Nardi M, Neoh C, Orgiazzi J, Pearce S, Pinchera A, Pitz S, Salvi M, Sivelli P, Stahl M, von Arx G, Wiersinga WM. 2008. Consensus statement of the European group on Graves' orbitopathy (EUGOGO) on management of Graves' orbitopathy. Thyroid 18:333–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leo M, Marcocci C, Pinchera A, Nardi M, Megna L, Rocchi R, Latrofa F, Altea MA, Mazzi B, Sisti E, Profilo MA, Marinò M. 2012. Outcome of Graves' orbitopathy after total thyroid ablation and glucocorticoid treatment: follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:E44–E48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]