Abstract

Most Cellulomonas strains are cellulolytic and this feature may be applied in straw degradation and bioremediation. In this study, Cellulomonas carbonis T26T, Cellulomonas bogoriensis DSM 16987T and Cellulomonas cellasea 20108T were sequenced. Here we described the draft genomic information of C. carbonis T26T and compared it to the related Cellulomonas genomes. Strain T26T has a 3,990,666 bp genome size with a G + C content of 73.4 %, containing 3418 protein-coding genes and 59 RNA genes. The results showed good correlation between the genotypes and the physiological phenotypes. The information are useful for the better application of the Cellulomonas strains.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40793-015-0096-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cellulomonas, Cellulomonas carbonis, Cellulolytic, Comparative genomics, Genome sequence

Introduction

Strain T26T (= CGMCC 1.10786T = KCTC 19824 T = CCTCC AB2010450 T) is the type strain of Cellulomonas carbonis which was isolated from coal mine soil [1]. The genus Cellulomonas was first proposed by Bergey et al. in 1923 [2]. To date, the genus Cellulomonas contains 27 species and mainly isolated from cellulose enriched environments such as soil, bark, wood and sugar field [1–4]. The common characteristics of the Cellulomonas strains are Gram-positive, rods, high G + C content (69–76 mol%) and cellulolytic, containing anteiso-C15:0 and C16:0 as the major fatty acids, and menaquinone-9(H4) as the predominant quinone. Most Cellulomonas strains can degrade cellulose and hemicellulose, making the strains applicable in paper, textile, and food industries, soil fertility and bioremediation [5–8]. The characterization of cellobiose phosphorylase, endo-1,4-xylanase, xylanases and endo-1,4-glucanase of Cellulomonas strains have been previously published [9–12].

So far, three genomes of Cellulomonas have been published including Cellulomonas flavigenaDSM 20109T [13], Cellulomonas fimiATCC 484T [14] and “Cellulomonas gilvus”ATCC 13127T1 [14] and showed a wide variety of cellulases and hemicellulases in their genomes [13, 14]. In order to provide more genomic information about Cellulomonas strains for potential industrial application, we sequenced the genomes of Cellulomonas carbonis T26T [1], Cellulomonas cellaseaDSM 20118T [2] and Cellulomonas bogoriensisDSM 16987T [15]. Here we present a summary genomic features of C. carbonis T26T together with the comparison results of the six available Cellulomonas genomes.

Organism information

Classification and features

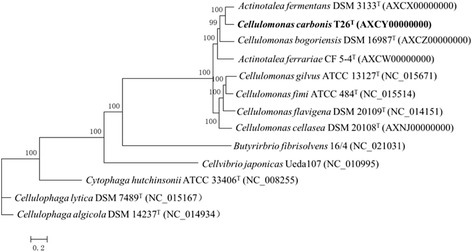

The taxonomic classification and general features of C. carbonis T26T are presented in Table 1. A total of 105 single-copy conserved proteins were obtained within the 13 genomes by OrthoMCL with a Match Cutoff 50 % and an E-value Exponent Cutoff 1-e5 [16, 17]. Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic tree of C. carbonis T26T and 12 related strains based on conserved gene sequences. The tree was constructed by MEGA 5.05 with Maximum-Likelihood method to determine phylogenetic position [18]. The genome based phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1) is similar to the 16S rRNA gene based phylogenetic tree [1].

Table 1.

Classification and general features of C. carbonis T26T

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [33] | |

| Phylum Actinobacteria | TAS [34] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [35] | ||

| Order Micrococcales | TAS [36] | ||

| Family Cellulomonadaceae | TAS [37] | ||

| Genus Cellulomonas | TAS [1, 38] | ||

| Species Cellulomonas carbonis | TAS [1] | ||

| (Type) strain: T26T = (CGMCC 1.10786T = KCTC 19824T = CCTCC AB2010450T) | |||

| Gram stain | Positive | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | Rod-shaped | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | Motile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | Non-sporulating | NAS | |

| Temperature range | 4-45 °C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 28 °C | TAS [1] | |

| pH range; Optimum | 6-10;7 | TAS [1] | |

| Carbon source | D-glucose, L-arabinose, mannose, N-acetyl | TAS [1] | |

| glucosamine, maltose, gluconate, sucrose, glycogen, salicin, D-melibiose, D-sorbitol, xylose, D-lactose, D-galactose, D-fructose, and raffinose. | |||

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Soil | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | 0-7 % NaCl (w/v) | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free-living | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | non-pathogen | NAS |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Tianjin city,China | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | 2012 | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 39°01'49.77" N | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 117°11'20.20" E | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not reported | TAS [1] |

aEvidence codes - IDA Inferred from Direct Assay, TAS Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature), NAS Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [23]

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing the position of C. carbonis T26T (shown in bold) based on aligned sequences of 105 single-copy conserved proteins shared among the 13 genomes. The conserved protein was acquired by OrthoMCL with a Match Cutoff 50 % and an E-value Exponent Cutoff 1-e5 [15, 16]. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using MEGA version 5.05 and the tree was built using the Maximum-Likelihood method [17] with 1000 bootstrap repetitions were computed to estimate the reliability of the tree. The corresponding GenBank accession numbers are displayed in parentheses

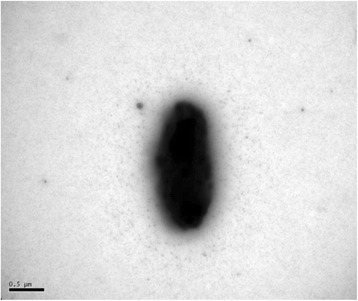

Strain C. carbonis T26T is Gram-positive, aerobic, motile and rod-shaped (0.5–0.8 × 2.0–2.4 μm) (Fig. 2). The colonies are yellow-white, convex, circular, smooth, non-transparent and about 1 mm in diameter after 3 days incubation on R2A agar at 28 °C [1]. The optimal growth occurs at 28 °C (Table 1). The strain was able to hydrolyse CM-cellulose, starch, gelatin, aesculin and positive in catalase and nitrate reduction [1]. C. carbonis T26T was capable of utilizing a wide range of sole carbon sources including D-glucose, L-arabinose, mannose, N-acetyl glucosamine, maltose, gluconate, sucrose, glycogen, salicin, D-melibiose, D-sorbitol, xylose, D-lactose, D-galactose, D-fructose and raffinose [1, Table 1].

Fig. 2.

A transmission electron micrograph of strain T26T grown on LB agar at 28 °C for 48 h. The bar indicates 0.5 μm

Chemotaxonomy

C. carbonis T26T contains anteiso-C15:0 (33.6 %), anteiso-C15:1 A (22.1 %), C16:0 (14.4 %) and C14:0 (12.1 %) as the major fatty acids and menaquinone-9(H4) as the predominant respiratory quinone. The major polar lipids of this strain were diphosphatidylglycerol and phosphatidylglycerol [1].

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing particularly due to its cellulolytic activity and other applications. Genome sequencing was performed by Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology in April-June, 2013. The raw reads were assembled by SOAPdenovo v1.05. The genome annotation was performed at the RAST server version 2.0 [19] and the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline and has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under accession number AXCY00000000. The version described in this study is the first version AXCY01000000. The project information are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Illumina Paired-End library (300 bp insert size) |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina Miseq 2000 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 343.5× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | SOAPdenovo v1.05 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | GeneMarkS+ |

| Locus tag | N868 | |

| GenBank ID | AXCY00000000 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | October 17, 2014 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi0055591 | |

| BIOPROJECT | PRJN215138 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | T26T |

| Project relevance | Genome comparison |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

Strain C. carbonis T26T was grown aerobically in 50 ml LB medium at 28 °C for 36 h with 160 rpm shaking. Cells were collected by centrifugation and about 20 mg pellet was obtained. Genomic DNA was extracted, concentrated and purified using the QiAamp kit (Qiagen, Germany). The quality of DNA was assessed by 1 % agarose gel electrophoresis and the quantity of DNA was measured using NanoDrop Spectrophotometer 2000 (Equl-Thermo SCIENTIFIC, USA). About 8.8 μg of genomic DNA was sent to Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd for library preparation and sequencing.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome of C. carbonis T26T was sequenced by Illumina Hisep2000 pair-end technology at Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd. A 300 bp Illumina standard shotgun library was constructed and generated 7,703,453 × 2 reads totaling 1,556,097,506 bp Illumina data. Raw reads were filtered using the FastQC toolkit and optimizing through local gap filling and base correction with Gap Closer. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found at the Illumina’s official website [20]. Using SOAPdenovo v1.05 version [21], 7,324,578 × 2 paired reads and 349,082 single reads were assembled de novo. Due to very high GC content, the final draft assembly yield 547 contigs arranged in 414 scaffolds with 343.5 × coverage. The final assembly results showed that 97.6 % of the bases present in larger contigs (>1000 bp), and the contig N50 is 29,777 bp. The draft genome of C. carbonis T26T is present as a set of contigs ordered against the complete genome of C. flavigenaDSM 20109T using Mauve software [22].

Genome annotation

The draft genome sequence of C. carbonis T26T was annotation through the RAST server version 2.0 and the National Center for Biotechnology Information Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline. Genes were identified using the gene caller GeneMarkS+ with the similarity-based gene detection approach [23]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the NCBI Nonredundant Database, Pfam [24], KEGG [25], and the NCBI Conserved Domain Database through the Batch web CD-Search tool [26]. The miscellaneous features were prediction by WebMGA [27], TMHMM [28] and SignalP [29]. The putative cellulose-degrading enzymes were identified through Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes Database (CAZymes) Database [30].

Genome properties

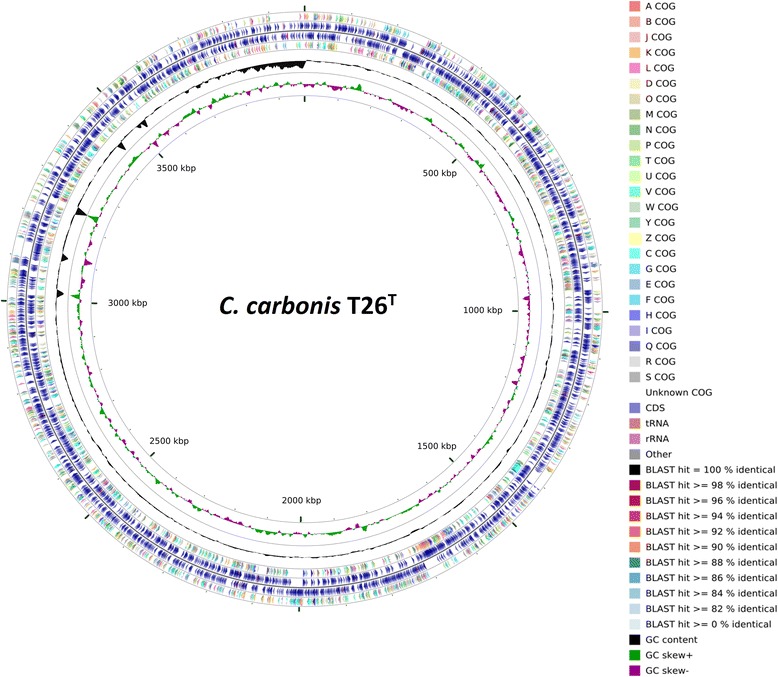

The whole genome of C. carbonis T26T is 3,990,666 bp in length, with an average GC content of 73.4 %, and comprised of 547 contigs. The genome properties and statistics are summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 3. From a total of 3513 genes, 3418 protein-coding genes were identified and 71 % of them were assigned putative functions, while the remainder was annotated as hypothetical proteins. In addition, 36 pseudogenes, 11 rRNA, 46 tRNAs and 1 ncRNA were identified. The distributions of genes among the COGs functional categories are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Genome statistics

| Attribute | Value | % of totala |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,990,666 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 2,927,153 | 73.35 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 3,368,220 | 84.40 |

| DNA scaffolds | 414 | 100.00 |

| Total genes | 3513 | 100.00 |

| Protein-coding genes | 3418 | 97.30 |

| RNA genes | 59 | 1.68 |

| Pseudo genes | 36 | 1.02 |

| Genes in internal clusters | 1435 | 40.85 |

| Genes with function prediction | 2481 | 71.00 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1450 | 41.28 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 2231 | 63.51 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 253 | 7.20 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 764 | 21.75 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | - |

aThe total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome

Fig. 3.

A graphical circular map of the C. carbonis T26T genome performed with CGview comparison tool [39]. From outside to center, ring 1, 4 show protein-coding genes colored by COG categories on forward/reverse strand; ring 2, 3 denote genes on forward/reverse strand; ring 5 shows G + C% content plot, and the innermost ring shows GC skew

Table 4.

Number of genes associated with general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | %agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 152 | 4.45 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 4 | 0.12 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 244 | 7.14 | Transcription |

| L | 136 | 3.98 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.03 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 29 | 0.85 | Cell cycle control, Cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| V | 58 | 1.70 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 195 | 5.71 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 141 | 4.13 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 54 | 1.58 | Cell motility |

| U | 61 | 1.78 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 106 | 3.10 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 181 | 5.30 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 298 | 8.72 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 198 | 5.79 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 72 | 2.11 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 116 | 3.39 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 91 | 2.66 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 130 | 3.80 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 48 | 1.40 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 340 | 9.95 | General function prediction only |

| S | 199 | 5.82 | Function unknown |

| - | 1968 | 57.58 | Not in COGs |

aThe percentage is based on the total number of protein-coding genes in the annotated genome

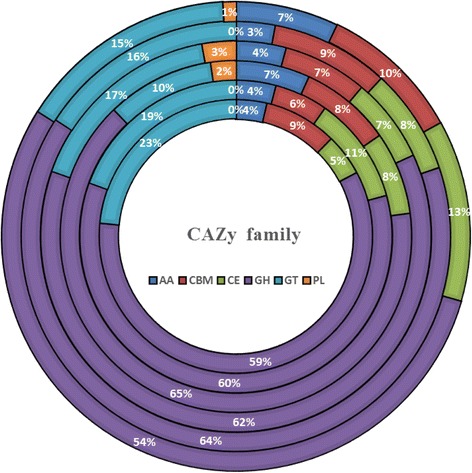

Insights from the genome sequence

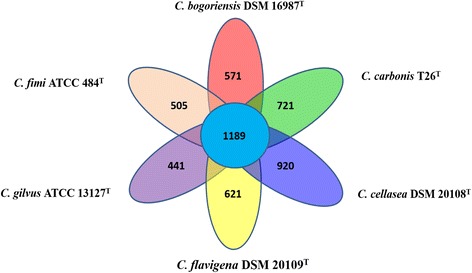

In order to reveal more genomic information for better application of the Cellulomonas strains, the genomic features of C. carbonis T26T together with the comparison results of the six Cellulomonas genomes were analyzed (Table 5). OrthoMCL analysis with a Match cutoff of 50 % and an E-value Exponent cutoff of 1-e5 identified 1189 single-copy conserved proteins among the six Cellulomonas genomes (Fig. 4). Several carbohydrate-active enzymes have been identified and classified into different families of glycoside hydrolases, carbohydrate binding modules, carbohydrate esterases, auxiliary activities and polysaccharide lyases [31] (Fig. 5, Additional file 1: Table S1). Some putative glycoside hydrolases may be responsible for the ability of Cellulomonas spp. to utilize various sole carbon sources.

Table 5.

General features of the six Cellulomonas genomes

| Strain | Isolation source | Genome size (Mb) | Coverge | CDSs | RNA | G + C content | GenBank No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. gilvus ATCC 13127T | feces | 3.53 | - | 3164 | 54 | 73.8 % | NC_015671 |

| C. fimi ATCC 484T | soil | 4.27 | - | 3761 | 54 | 74.7 % | NC_015514 |

| C. flavigena DSM 20109T | soil | 4.12 | - | 3678 | 54 | 74.3 % | NC_014151 |

| C. bogoriensis DSM 16987T | sediment and water | 3.19 | 368.2 x | 2898 | 51 | 72.2 % | AXCZ00000000 |

| C. carbonis T26T | coal mine soil | 3.99 | 343.5 x | 3418 | 59 | 73.3 % | AXCY00000000 |

| C. cellasea DSM 20108T | NR | 4.66 | 724.0 x | 3560 | 44 | 74.6 % | AXNJ00000000 |

Fig. 4.

Ortholog analysis of the six Cellulomonas genomes conducted using OrthoMCL. The total numbers of shared proteins among the six genomes and unique proteins from each species were tabulated and presented as a Venn diagram

Fig. 5.

Comparative analysis of putative proteins of CAZy family of six Cellulomonas genomes. From outside to center, ring 1 is C. flavigena DSM 20109T; ring 2 is C. gilvus ATCC 13127T; ring 3 is C. fimi ATCC 484T; ring 4 is C. cellasea DSM 20108T; ring 5 is C. bogoriensis DSM 16987T; ring 6 is C. carbonis T26T. AA, auxiliary activities; CBM, carbohydrate binding module; CE, carbohydrate esterase; GH, glycoside hydrolases; GT, glycosyltransferase; PL, polysaccharide lyase

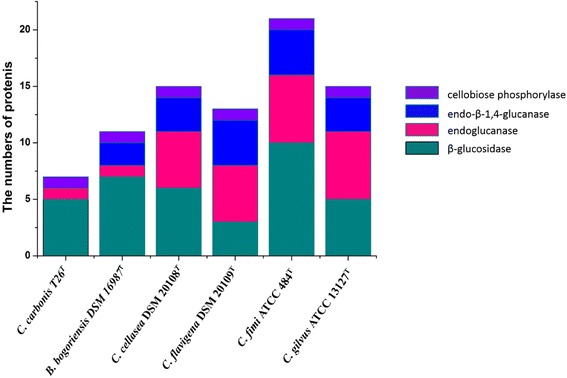

Some potential cellulose-degrading enzymes were found and analyzed (Fig. 6, Additional file 1: Table S2). C. fimiATCC 484T possesses the highest number of putative cellulases, including ten members of β-glucosidases (GH1 and GH3); six members of endoglucanases (GH6 and GH9); four endo-β-1,4-glucanases (GH48 and GH5) and one cellobiose phosphorylase (GH94). C. carbonis T26T has the fewest putative cellulases, including one cellobiose phosphorylase (GH94); one endoglucanase (GH6) and five β-glucosidases (GH1 and GH3). Cellulose activity assays were performed on Congo-Red agar media [32] and all of the six Cellulomonas strains yielded a cellulose clearing zone on the media (data not shown). The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes was used to construct metabolic pathways and all of the six Cellulomonas strains have the complete cellulose degradation pathways (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

The distribution of cellulases in six Cellulomonas genomes. The cellulases are β-glucosidase, endoglucanase, endo-β-1,4-glucanase and cellobiose phosphorylase

In addition to the utilization of cellulose, the Cellulomonas strains are also known to degrade hemicelluloses. A large number of putative intracellular and extracellular xylan degrading enzymes have been identified in the Cellulomonas genomes, such as endo-1-4,-β-xylanase, β-xylosidase, α-L-arabinofuranosidase, acetylxylan esterase and α-glucuronidase (Additional file 1: Table S3) which suggests the capacity to degrade hemicelluloses. We also found a large number of α-amylases which are responsible to the degradation of starch in the six Cellulomonas genomes (Additional file 1: Table S4) suggest the potential application in bioremediation of food industrial wastewater.

Conclusions

The genomic information of C. carbonis T26T and the comparison results of the six Cellulomonas genomes revealed a high degree of putative cellulases, hemicellulases. In addition, we found that the genomes also contain members of α-amylases. These information provides a genomic basis for the better application of Cellulomonas spp. in industry and environmental bioremediation. In addition, the genomes possess many putative carbohydrate-active enzymes which is in agreement with their physiological ability to utilize various sole carbon sources.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31470227).

Abbreviations

- RAST

Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology

- PGAP

Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline

Additional file

Putative CAZy family and locus_tag number in the six cellulomonas genomes. Table S2. Putative cellulases in the six cellulomonas genomes. Table S3. Putative hemicellulases in the six cellulomonas genomes. Table S4. Putative amylases in the six cellulomonas genomes. (XLSX 29 kb)

Footnotes

Editorial note – although designated as a type strain of Cellulomonas gilvus by Christopherson et al., this strain continues to be listed as a non-type strain of Cellvibrio gilvus in the ATCC catalogue. At present, neither name has standing in the taxonomic literature.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZW performed the sequence annotation and genomic analysis and wrote the draft manuscript. ZS and XX helped performing the comparative genomic analysis. GW organized the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Shi Z, Luo G, Wang G. Cellulomonas carbonis sp. nov., isolated from coal mine soil [J] Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62(Pt 8):2004–10. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.034934-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imhoff JF. Genus I. Rhodobacter. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, second edition. vol. 2 (The Proteobacteria), part C (The Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, and Epsilonproteobacteria) New York: Springer; 2005. p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funke G, Ramos CP, Collins MD. Identification of some clinical strains of CDC coryneform group A-3 and A-4 bacteria as Cellulomonas species and proposal of Cellulomonas hominis sp. nov. for some group A-3 strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(8):2091–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2091-2097.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elberson MA, Malekzadeh F, Yazdi MT, Kameranpour N, Noori-Daloii MR, Matte MH, et al. Cellulomonas persica sp. nov. and Cellulomonas iranensis sp. nov., mesophilic cellulose-degrading bacteria isolated from forest soils. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50 Pt 3:993–6. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-3-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhad RC, Gupta R, Singh A. Microbial cellulases and their industrial applications. Enzyme Res. 2011;2011:280696. doi: 10.4061/2011/280696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaur A, Mahajan R, Singh A, Garg G, Sharma J. Application of cellulase-free xylano-pectinolytic enzymes from the same bacterial isolate in biobleaching of kraft pulp. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101(23):9150–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han W, He M. The application of exogenous cellulase to improve soil fertility and plant growth due to acceleration of straw decomposition. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101(10):3724–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.12.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saratale GD, Saratale RG, Lo YC, Chang JS. Multicomponent cellulase production by Cellulomonas biazotea NCIM-2550 and its applications for cellulosic biohydrogen production. Biotechnol Prog. 2010;26(2):406–16. doi: 10.1002/btpr.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wildberger P, Brecker L, Nidetzky B. Examining the role of phosphate in glycosyl transfer reactions of Cellulomonas uda cellobiose phosphorylase using D-glucal as donor substrate. Carbohydr Res. 2012;356:224–32. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayorga-Reyes L, Morales Y, Salgado LM, Ortega A, Ponce-Noyola T. Cellulomonas flavigena: characterization of an endo-1,4-xylanase tightly induced by sugarcane bagasse. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;214(2):205–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santiago-Hernández A, Vega-Estrada J, del Carmen M-HM, Hidalgo-Lara ME. Purification and characterization of two sugarcane bagasse-absorbable thermophilic xylanases from the mesophilic Cellulomonas flavigena. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;34(4):331–8. doi: 10.1007/s10295-006-0202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutiérrez-Nava A, Herrera-Herrera A, Mayorga-Reyes L, Salgado LM, Ponce-Noyola T. Expression and characterization of the celcflB gene from Cellulomonas flavigena encoding an Endo-1,4-Glucanase. Curr Microbiol. 2003;47(5):359–63. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-4016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abt B, Foster B, Lapidus A. Complete genome sequence of Cellulomonas flavigena type strain (134 T)[J] Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;3(1):15. doi: 10.4056/sigs.1012662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christopherson MR, Suen G, Bramhacharya S, Jewell KA, Aylward FO, Mead D, et al. The genome sequences of Cellulomonas fimi and “Cellvibrio gilvus” reveal the cellulolytic strategies of two facultative anaerobes, transfer of “Cellvibrio gilvus” to the genus Cellulomonas, and proposal of Cellulomonas gilvus sp. nov[J] PloS one. 2013;8(1):e53954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones BE, Grant WD, Duckworth AW. Cellulomonas bogoriensis sp. nov., an alkaliphilic cellulomonad [J] Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55(4):1711–4. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13(9):2178–89. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer S, Brunk BP. Chen F, Gao X. Harb OS: Iodice JB, et al. Using OrthoMCL to assign proteins to OrthoMCL-DB groups or to cluster proteomes into new ortholog groups. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, Disz T, et al. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(D1):206–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Illumina [http://www.illumina.com.cn/]

- 21.SOAPdenovo v1.05 [http://soap.genomics.org.cn/]

- 22.Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(D):222–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa A, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(W):182–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchler-Bauer A, Lu S, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(D):225–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu S, Zhu ZW, Fu L, Li W. WebMGA: a customizable web server for fast metagenomic sequence analysis. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:444. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krogh A, Larsson BÈ, Von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305(3):567–80. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyrlov Bendtsen J, Nielsen H, von Heijne G. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340(4):783–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lombard V, Golaconda Ramulu H, Drula E, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. The Carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D490–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sangrila S, Tushar KM. Cellulase production by bacteria: a review. British Microbiology Research Journal. 2013;3(3):235–58. doi: 10.9734/BMRJ/2013/2367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teather RM, Wood PJ. Use of Congo red-polysaccharide interactions in enumeration and characterization of cellulolytic bacteria from the bovine rumen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:777–80. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.4.777-780.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woese CR, Kandler O, Weelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms. Proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4576–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ventura M, Canchaya C, Tauch A, Chandra G, Fitzgerald GF, Chater KF, et al. Genomics of Actinobacteria: Tracing the Evolutionary History of an 173 Ancient Phylum. Microbiol Mol Biol R. 2007;71(3):495–548. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00005-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997;47:479–91. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009;59:589–608. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stackebrandt E, Schumann P, Prauser H. The family Cellulomonadaceae. The prokaryotes. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 983–1001. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stackebrandt E, Seiler H, Schleifer KH. Union of the genera Cellulomonas Bergey et al. and Oerskovia Prauser et al. in a redefined genus Cellulomonas. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Parasitenkd. Infektionskr. Hyg. Abt. 1 Orig. 1982;C3:401–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grant JR, Arantes AS, Stothard P. Comparing thousands of circular genomes using the CGView Comparison Tool. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:202. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]