Abstract

Patient: Male, 30

Final Diagnosis: Acute epidural hematoma

Symptoms: —

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Observation

Specialty: Neurosurgery

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Trauma is the leading cause of death in people younger than 45 years and head injury is the main cause of trauma mortality. Although epidural hematomas are relatively uncommon (less than 1% of all patients with head injuries and fewer than 10% of those who are comatose), they should always be considered in evaluation of a serious head injury. Patients with epidural hematomas who meet surgical criteria and receive prompt surgical intervention can have an excellent prognosis, presumably owing to limited underlying primary brain damage from the traumatic event. The decision to perform a surgery in a patient with a traumatic extraaxial hematoma is dependent on several factors (neurological status, size of hematoma, age of patients, CT findings) but also may depend on the judgement of the treating neurosurgeon.

Case Report:

A 30-year old man arrived at our Emergency Department after a traumatic brain injury. General examination revealed severe headache, no motor or sensory disturbances, and no clinical signs of intracranial hypertension. A CT scan documented a significant left fronto-parietal epidural hematoma, which was considered suitable for surgical evacuation. The patient refused surgery. Following CT scan revealed a minimal increase in the size of the hematoma and of midline shift. The neurologic examination maintained stable and the patient continued to refuse the surgical treatment. Next follow up CT scans demonstrated a progressive resorption of hematoma.

Conclusions:

We report an unusual case of a remarkable epidural hematoma managed conservatively with a favorable clinical outcome. This case report is intended to rather add to the growing knowledge regarding the best management for this serious and acute pathology.

MeSH Keywords: Brain Injuries; Cerebral Hemorrhage, Traumatic; Hematoma, Subdural, Acute

Background

Trauma is the leading cause of death in people younger than 45 years and head injury is the main cause of trauma mortality [1–4]. Although epidural hematomas are relatively uncommon (less than 1% of all patients with head injuries and less than 10% of those who are comatose), they should always be considered in evaluation of a serious head injury.

Patients with epidural hematomas who meet surgical criteria and receive prompt surgical intervention can have an excellent prognosis, presumably owing to limited underlying primary brain damage from the traumatic event. The decision to perform a surgery in a patient with a traumatic extraaxial hematoma is dependent on several factors (neurological status, size of hematoma, age of patients, CT findings) but also may depend on the judgement of the treating neurosurgeon [5–7]. We report an unusual case of a remarkable epidural hematoma managed conservatively with a favorable clinical outcome.

Case Report

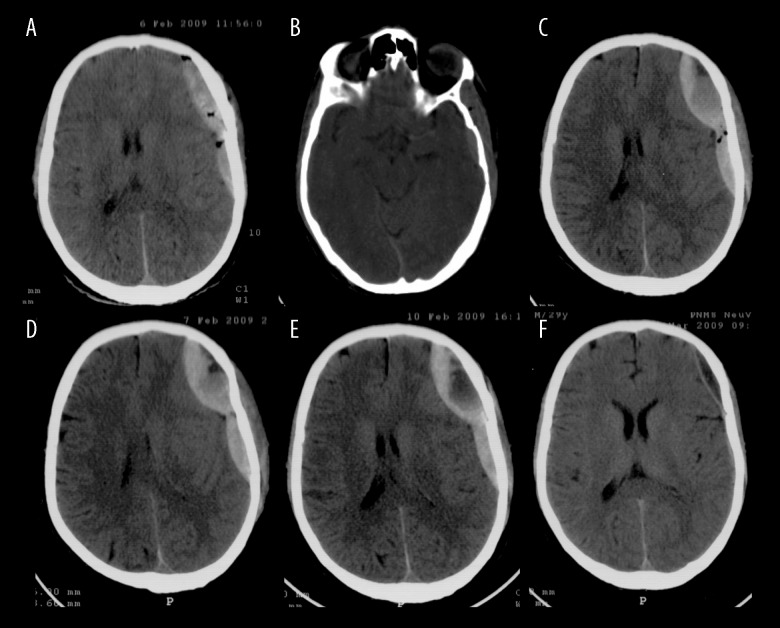

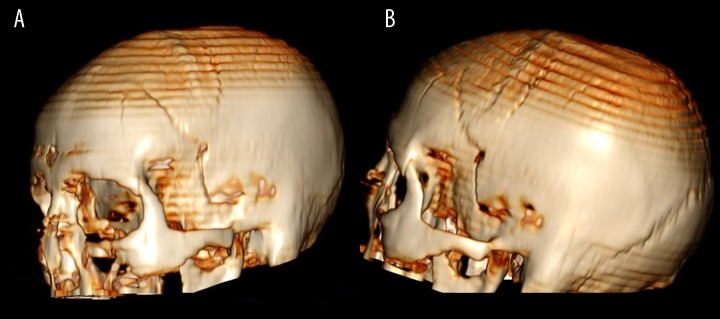

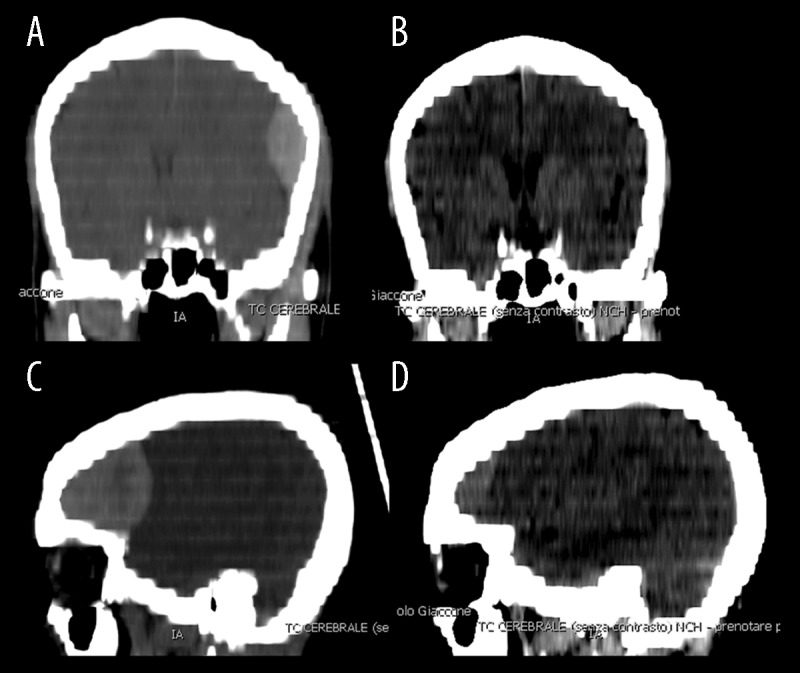

A young 30-year-old man arrived at our Emergency Department approximately 7 hours after a traumatic brain injury (TBI) with a loss of consciousness due to a bicycle accident. General examination of the patient was remarkable for a left parietal scalp laceration, left periorbital hematoma, and a swollen and tender left wrist due to a distal radius fracture. Funduscopic examination was normal. Mental status examination demonstrated an alert patient who was oriented to place and person but not to time. Sensory and motor examinations were normal. The patient reported an intense headache but denied emesis. The remainder of the neurological examination was normal. Skull films revealed a left parietal linear skull fracture. The patient was admitted to the hospital for observation. A CT scan was promptly obtained, which revealed a left fronto-parietal epidural hematoma (EDH) (2.4 cm in maximum thickness, with 8 mm of midline shift) (Figure 1A, Figure 2A, 2C) under the skull fracture (Figure 1B, Figure 3A, 3B). Because of these findings, surgical evacuation was offered to the patient. However, the patient refused surgery and he was therefore placed in the Neurosurgical ward with continuous electrocardiographic and respiratory monitoring. His vital signs and neurological status were initially checked every 60 minutes, with particular attention to alterations in the level of consciousness, subtle evidence of cranial neuropathies, hemiparesis, or changes in his cardiorespiratory patterns. A follow-up CT scan was performed 6 (Figure 1C) and 24 hours (Figure 1D) following the initial study. Both studies demonstrated a minimal increase in the size of the hematoma and no worsening of the midline shift. Monitoring was continued with serial examinations and daily head CT scans until the 5th post-injury day (Figure 1E). At this point, the hematoma was noted to be slightly enlarged and demonstrated increased midline shift (1.2 cm). The patient continued to remain neurologically intact and continued to refuse surgical intervention. Intracranial pressure monitoring was excluded on the basis of a good GCS (14/15). All laboratory values were within the normal limits, with no evidence of electrolyte disorder or coagulopathy. Continuing follow-up CT scans demonstrated progressive reabsorption of the hematoma. The patient was discharged in stable condition on the 14th hospital day. Repeated CT scans were obtained on the 20th (Figure 1F, Figure 2B, 2D) and 30th post-injury days and demonstrated gradual and ultimately complete resolution of the epidural hematoma.

Figure 1.

Head CT scan reveals an epidural hematoma on left fronto temporal region. (A) Admission; (B) temporal skull fracture; (C) after 6 hours; (D) after 24 hours; (E) after 5 days; (F) after 20 days.

Figure 2.

Head CT scan with coronal (A, B) and sagittal (C, D) reconstruction reveals an epidural hematoma on left fronto temporal region. (A) Admission; (B) after 20 days; (C) admission; (D) after 20 days.

Figure 3.

Head CT scan with 3D (A, B) reconstruction reveals a left temporal skull fracture.

Discussion

Head injury remains the single greatest cause of death and disability among children and young adults. Fortunately, patients with extradural hematoma (EDH) are generally treatable and often have a favorable clinical outcome [5] when free of other injuries [8–10]. The mortality rate associated with this condition has improved radically since the time of Rose and Carless, who in 1927 reported mortality rates of 86% [11]. With modern surgical and anaesthesia techniques, the mortality rate of epidural hematomas has been reduced to almost 0% in non-comatose patients [12]. New surgical options have been analyzed for replacing the classic surgical technique of craniotomy [13,14].

Epidural hematoma often has a traumatic origin and in most of cases is caused by a medial meningeal artery lesion. The blood collection grows rapidly in the epidural space, compressing the underlying brain parenchyma. Several observations on EDH have shown that clots confined to the temporal fossa produce uncal herniation more rapidly and with a smaller critical volume than clots located elsewhere [15].

Ford and McLaurin demonstrated that EDH achieves nearly full size within a very brief period following the injury, suggesting that physical and chemical effects other than increasing size may be the cause of neurologic deterioration in untreated cases. Several authors emphasized the effects of cerebral edema, hypoxia, and/or impaired cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage as causing the deleterious effects of the hematoma [16,17].

In the era before computerized tomography (CT), extradural hematomas were usually diagnosed by invasive and less accurate techniques, such as cerebral angiography, pneumoencephalography, or exploratory burr holes. Thus, the philosophy for immediate and universal evacuation to avoid the inevitability of brain stem compression is understandable. However, with the advent of CT, an increasing number of patients receive imaging despite minimal neurologic findings. In some cases, an EDH may be identified and the surgeon must decide whether to recommend surgical intervention.

Despite the risks of a serious and untreated EDH, it has become increasingly apparent that many small epidural hematomas resolve with nonsurgical management without neurologic sequelae. Some series [18–22] and a few single case reports [23–30] described good outcome with conservative management of selective epidural hematoma (Table 1). In some series, a few cases, managed conservatively, needed surgical treatment on the basis of worsening neurological status [17,31–33]. Small EDH can often spread along the convexity of the brain and do not cause midline shift or significant mass effect [34]. This type of EDH can safely be managed by simple observation, especially in pediatric patients. In this group, mental status, serial neurological examination, and radiographic findings should guide the need for surgical evacuation [35,36]. The role of a CT follow-up is controversial in pediatric patients with good GOS scores [37].

Table 1.

Literature series of conservative management of intracranial epidural hematoma.

| Authors | Year | No. of patients | Outcome in conservative management | No. of surgical treatment | Time to resorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xuxiang | 1981 | 9 | Favorable | 0 | Unknown |

| Weaver | 1981 | 2 | Favorable | 0 | 30–49 days |

| Pang | 1983 | 11 | 9 cases favorable (1 case of transitory vi nerve paresis) | 2 | 4–7 weeks |

| Tochio | 1984 | 3 | Favorable | 0 | Unknown |

| Bullock | 1985 | 123 | 111 cases favorable | 12 | 3–15 weeks |

| Pozzati | 1986 | 22 | Favorable | 0 | 30 days |

| Aoki | 1988 | 2 | Favorable | 0 | 9 hours–13 days |

| Sakai | 1988 | 37 | Unknown | 0 | Unknown |

| Servadei | 1989 | 42 | 38 favorable, 3 with minor sequelae,1 death | 0 | Unknown |

| Negishi | 1989 | 4 | 3 cases favorable, 1 case mild motor deficit (other intracranial hemorrhages) | 0 | Unknown |

| Knuckey | 1989 | 22 | 15 cases favorable | 7 | Unknown |

| Hamilton | 1992 | 18 | Favorable | 1 | Unknown |

| Cucciniello | 1993 | 57 | Favorable | 0 | 1–3 months |

| ChenTzu-Yung | 1993 | 111 | Favorable | 14 | Unknown |

| Tuncer | 1993 | 15 | Favorable | 0 | 4 weeks |

| Kuroiwa | 1993 | 1 | Favorable | 0 | 12 hours |

| Lahat | 1994 | 14 | 8 favorable | 6 | Unknown |

| Malek | 1997 | 1 | Favorable | 0 | 18 hours |

| Sullivan | 1999 | 160 | Favorable | 0 | Unknown |

| Miller | 1999 | 2 | Favorable | 1 | 6 weeks |

| Kang | 2005 | 1 | Dead for cerebral edema | 0 | 21 hours |

| Offner | 2006 | 54 | 47 Cases favorable | 7 | Unknown |

| Balmer | 2006 | 13 | 12 Cases favorable | 1 | 2–3 months |

| Eom | 2009 | 1 | Favorable | 0 | 16 hours |

| Jamous | 2009 | 6 | Favorable | 0 | 2–3 months |

| Dolgun | 2011 | 1 | Dead for thoracic trauma | 0 | 3 hours |

| Gülşen | 2013 | 1 | Favorable | 0 | 12 hours |

| Chauvet | 2013 | 1 | Favorable | 0 | Unknown |

| Khan | 2014 | 17 | 15 Cases favorable | 2 | Unknown |

Xuxiang et al. reported a series of 9 Chinese patients with large EDH and signs of herniation who were treated by herbal medicines without surgery. All patients reportedly recovered without neurologic deficits and demonstrated angiographically proven resolution of their hematomas [38].

Weaver et al. reported 2 cases: 1 patient with a temporal EDH in whom CT was performed 16 hours after injury, and the other with a temporoparietal extradural hematoma diagnosed 3 days after injury; both were treated conservatively and the hematomas resolved spontaneously by 30 and 49 days following injury, respectively [39].

In 1985, Bullock et al. reported 22 patients with an epidural hematoma (12 to 38 ml in volume), all managed conservatively and with a complete reabsorption of the hematoma. All the patients made a complete neurological recovery and showed resolution of the hematoma on CT scanning over a period of 3 to 15 weeks [40]. Pozzati et al. published a series of 22 patients managed without surgery for acute extradural hematomas. All patients in this series were either asymptomatic or had only minimal neurological findings on admission.

In all cases, serial CT scanning documented progressive resolution of the clots, most within 1 month after the injury [41]. Servadei et al. reported a study conducted at 3 Italian neurosurgical centers involving 158 patients admitted following minor head trauma who had CT evidence of significant extradural hematoma. The size of the hematoma (rather than location) and the degree of midline shift were the factors influential in decision for surgical treatment. Conservative management was utilized for hematomas having a maximum thickness of less than 10 mm with a midline shift of less than 5 mm. Both groups of patients had favorable outcomes in this study [42].

Chen Tzu-Yung et al. reported a series of 74 patients with a traumatic epidural hematoma and a Glasgow Coma Scale score of greater than 12, managed nonoperatively; 14 subsequently underwent surgical evacuation. They reported that only supratentorial EDH with volume more than 30 ml, a thickness more than 15 mm, and a midline shift more than 5 mm required surgery [43].

Sullivan et al. reported a large series of 252 consecutive patients with acute epidural hematomas. Overall, 160 of the cases where managed nonsurgically with generally favorable outcomes [44].

Offner et al. studied 84 patients with epidural hematoma using the Saint Anthony Central Hospital trauma registry. The goal of the study was to compare patients who succeeded or failed nonoperative care to identify risk factors for failure. Overall, 64% of patients in the series were initially treated nonsurgically. Of these, 87% of the nonsurgically treated patients were able to be successfully managed without surgery. However, those who failed nonsurgical management were successfully treated surgically in a delayed fashion without adverse outcome [45].

Bullock et al. suggested criteria for the management of EDH in 2006. They strongly recommended urgent surgical management for patients in coma (GCS score <9) with anisocoria and for those with a hematoma larger than 30 cm3 in size, regardless of the patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score. Patients with an EDH less than 30 cm3, less than 15-mm in thickness, with less than 5-mm of midline shift, and a GCS score greater than 8 without focal deficits were felt to be candidates for nonsurgical management with close observation and serial CT scans [46].

In the current report, we describe a more severe and well documented epidural hematoma managed conservatively, with a favorable outcome. In our case, the “worst” CT scan demonstrated a maximum thickness of 2.5 cm and 1.2 cm of midline shift. The approximate volume of the hematoma was estimated to be 30 ml. A key point of the current report is that the patient’s neurologic examination remained stable throughout the period of observation. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the few well documented cases of an epidural hematoma of this magnitude managed successfully by nonsurgical care.

Many factors may play a role in the patient’s ability to tolerate a given clot volume, including rapidity of volume accumulation, presence of associated intradural lesions, elasticity of the brain, combined volume of the sulci and other anatomic variations, and the location of the hematoma. EDH, both supratentorial and in the posterior fossa, can be managed nonsurgically. A large volume EDH (>30 cm3) can be managed nonsurgically provided the GCS at presentation and follow-up remains the same, with symptomatic improvement [47].

It can be speculated that in our case not the arterial bleeding but the venous one was the driving force of the enlarging EDH. So far studies on influencing factors as age, cerebral atrophy, the type of the trauma, the relationship of the primary lesion with intra and extra axial vascular structures and general metabolic parameters are not been published.

Conclusions

This case report is intended to add to the growing knowledge regarding the best management of this serious and acute pathology. Posttraumatic epidural hematoma presenting a maximum thickness of 2.5 cm, a midline shift of 1.2 cm, and approximate volume of 30 ml can be successfully managed in a conservative fashion. Further studies on influencing factors must be taken into consideration to allow an updated and more reliable systematization of this complex and challenging issue.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References:

- 1.Grenvik A, Stephen MA, Ayres SM, et al. Management of Traumatic Brain Injury in the Intensive Care Unit. Critical Care. (4th ed) 2000:322–26. [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKenzie EJ. Epidemiology of injuries: Current trends and future challenges. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:112–19. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Wald MM. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: A brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:375–78. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall LF. Head injury. Recent past, present and future. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:546–61. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200009000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tallon JM, Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Karim SA, Clarke DB. The epidemiology of surgically treated acute subdural and epidural hematomas in patients with head injuries: a population-based study. Can J Surg. 2008;51(5):339–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cordobes F, Lobato RD, Rivas JJ, et al. Observations on 82 patients with extradural hematoma. Comparison of results before and after the advent of computerized tomography. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:179–86. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.54.2.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irie F, Le Brocque R, Kenardy J, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic epidural hematoma in young age. J Trauma. 2011;71(4):847–53. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182032c9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolgun H, Türkoğlu E, Kertmen H, et al. Rapid resolution of acute epidural hematoma: case report and review of the literature. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011;17(3):283–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang SH, Chung YG, Lee HK. Rapid disappearance of acute posterior fossa epidural hematoma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2005;45(9):462–63. doi: 10.2176/nmc.45.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Negishi H, Lee Y, Itoh K, et al. Nonsurgical management of epidural hematoma in neonates. Pediatr Neurol. 1989;5(4):253–56. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(89)90086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson WHA. On middle meningeal haemorrhage. Guys Hosp Rep. 1886;43:147–308. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rehman L, Khattak A, Naseer A, Mushtaq Outcome of acute traumatic extradural hematoma. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18(12):759–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang AP, Huang SJ, Hong WC, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for acute noncomplicated epidural hematoma: an innovative endoscopic-assisted method. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(3):774–77. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824a7974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lammy S, McConnell R, Kamel M, et al. Extradural haemorrhage: is there a role for endovascular treatment? Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27(3):383–85. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.717981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooper R. Observations on extradural haemorrhage. Br J Surg. 1959;47:71–87. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004720114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford LE, McLaurin RL. Mechanisms of extradural hematomas. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:760–69. doi: 10.3171/jns.1963.20.9.0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knuckey NW, Gelbard S, Epstein MH. The management of “asymptomatic” epidural hematomas. A prospective study. J Neurosurgm. 1989;70:392–96. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.3.0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cucciniello B, Martelotta N, Nigro D, Citro E. Conservative management of extradural haematomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1993;120:47–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02001469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton M, Wallace C. Nonoperative management of acute epidural hematoma diagnosed by CT: the neuroradiologist’s role. Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;13:853–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamous MA, Abdel Aziz H, Al Kaisy F, et al. Conservative management of acute epidural hematoma in a pediatric age group. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2009;45:181–84. doi: 10.1159/000218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakai H, Takagi H, Ohtaka H, et al. Serial changes in acute extradural hematoma size and associated changes in level of consciousness and intracranial pressure. J Neurosurg. 1988;8:566–70. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.4.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuncer R, Kazan S, Uçar T, et al. Conservative management of epidural haematomas: prospective study of 15 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1993;121:48–52. doi: 10.1007/BF01405182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aoki N. Rapid resolution of acute epidural hematoma. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1988;68(1):149–51. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.1.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chauvet D, Reina V, Clarencon F, et al. Conservative management of a large occipital extradural haematoma. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27(4):526–28. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2013.769499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eom K, Park J, Kim T, Kim J. Rapid spontaneous redistribution of acute epidural hematoma: case report and literature review. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;45:96–98. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2009.45.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gülşen I, Ak H, Sösüncü E, et al. Spontaneous rapid resolution of acute epidural hematoma in childhood. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:956849. doi: 10.1155/2013/956849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuroiwa T, Tanabe H, Takatsuka H, et al. Rapid spontaneous resolution of acute extradural and subdural hematomas. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(1):126–28. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.1.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malek AM, Barnett FH, Schwartz MS, Scott RM. Spontaneous rapid resolution of an epidural hematoma associated with an overlying skull fracture and subgaleal hematoma in a 17-month-old child. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1997;26(3):160–65. doi: 10.1159/000121182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller DJ, Steinmetz M, McCutcheon IE. Vertex epidural hematoma: surgical versus conservative management: two case reports and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1999;45(3):621–24. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199909000-00036. discussion 624–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tochio H, Waga S, Tashiro H, et al. Spontaneous resolution of chronic epidural ematoma: report of 3 cases. Neurosurgery. 1984;15:96–100. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198407000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balmer B, Boltshauser E, Altermatt S, Gobet R. Conservative management of significant epidural haematomas in children. Child’s nervous system: ChNS. Off J International Soc Pediatr Neurosurg. 2006;22:363–67. doi: 10.1007/s00381-005-1254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan MB, Riaz M, Javed G. Conservative management of significant supratentorial epidural hematomas in pediatric patients. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014;30(7):1249–53. doi: 10.1007/s00381-014-2391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lahat E, Livne M, Barr J, et al. The management of epidural haematomas – surgical versus conservative treatment. Eur J Pediatr. 1994;153(3):198–201. doi: 10.1007/BF01958986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pang D, Horton JA, Herron JM, et al. Nonsurgical management of extradural hematomas in children. J Neurosurg. 1983;59(6):958–71. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.59.6.0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flannery AM. Cautions in the conservative management of epidural hematomas. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2009;45(3):185. doi: 10.1159/000222667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flaherty BF, Loya J, Alexander MD, et al. Utility of clinical and radiographic findings in the management of traumatic epidural hematoma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2013;49(4):208–14. doi: 10.1159/000363143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skadorwa T, Zygańska E, Eibl M, Ciszek B. Distinct strategies in the treatment of epidural hematoma in children: clinical considerations. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2013;49(3):166–71. doi: 10.1159/000359954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xuxiang Q, Juemin H, Ruixian Z. Nonsurgical traditional Chinese medicine in extradural hematomas. Chin Med J. 1981;94:241–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weaver D, Pobereskin L, Jane JA. Spontaneous resolution of epidural hematomas. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1981;54(2):248–51. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.54.2.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bullock R, Smith RM, van Dellen JR. Nonoperative management of extradural hematoma. Neurosurgery. 1985;16(5):602–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pozzati E, Tognetti F. Spontaneous healing of acute extradural hematomas: study of twenty-two cases. Neurosurgery. 1986;18(6):696–700. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198606000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Servadei F, Faccani G, Roccella P, et al. Asymptomatic extradural haematomas: results of a multicenter study of 158 cases in minor head injury. Acta Neurochirur (Wien) 1989;96:39–45. doi: 10.1007/BF01403493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen TY, Wong CW, Chang CN, et al. The expectant treatment of “asymptomatic” supratentorial epidural hematomas. Neurosurgery. 1993;32(2):176–79. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sullivan TP, Jarvik JG, Cohen WA. Follow-up of conservatively managed epidural hematomas: implications for timing of repeat CT. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Offner PJ, Pham B, Hawkes A. Nonoperative management of acute epidural hematomas: a “no-brainer”. Am J Surg. 2006;192(6):801–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, et al. Surgical management of acute epidural hematomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(3 Suppl.):S7–15. discussion Si-iv. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zakaria Z, Kaliaperumal C, Kaar G, et al. Extradural haematoma – to evacuate or not? Revisiting treatment guidelines. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(8):1201–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]