Abstract

The relationship between racial discrimination, parental functioning, and child adjustment is not well understood. The goal of the present study was to assess parental reports of discrimination in relation to depression and parenting practices, as well as on subsequent child internalizing and externalizing problems in low-income Black families. Data include a subsample of the Early Steps project, a multisite longitudinal study of financial and behaviorally at-risk families. Structural equation modeling was used to analyze our hypothesized model. Excellent model fit was established after removing externalizing problems from the model. As predicted, indirect associations were found from discrimination to parental depression, parenting, and child internalizing problems; and direct associations were found from discrimination to child internalizing problems. The results are consistent with findings suggesting that discrimination is negatively associated with adult well-being; moreover, contribute to the sparse literature on the effects of discrimination beyond the direct recipient. Finally, that parent discrimination was directly associated with child emotional problems suggests the continued need to address and treat discriminatory practices more generally.

Keywords: discrimination, psychosocial outcomes, low-income, Black families, parenting

It is widely accepted that parenting behaviors are associated with child well-being (Brody et al., 2008; Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000; Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson, & Gardner, 2009). Although parenting behaviors have been shown to vary in effectiveness across culture (Pinderhughes, Dodge, Bates, Pettit, & Zelli, 2000; Skinner, MacKenzie, Haggerty, Hill, & Roberson, 2011; Sorhkabi & Mandara, 2013), researchers often find that consistent and warm parenting is optimal for child development (Belsky, 1984; Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Furthermore, parenting skills and relationships are often contingent on the well-being of the parent (Arellano, Harvey, & Thakar, 2012; Wade, Giallo, & Cooklin, 2012). When parents face challenges to their own mental health, it may be difficult to rear a child with consistency and affection. Everyday stressors (e.g., problems at work, financial shortages, etc.) can affect the well-being of all parents, however, culturally specific stressors (e.g., discrimination) may be particularly debilitating for Black parents, given that discrimination has been negatively associated with well-being (Lee & Ahn, 2013). Although research has demonstrated the direct impact of discrimination on Black adult’s mental (Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, & Zimmerman, 2003) and physical (Brody et al., 2008) health, less is known about how parents’ experiences with discrimination may be associated with children’s well-being (McNeil, Harris-McKoy, Brantley, Fincham, & Beach, 2013; Simons et al., 2002). Thus, the purpose of the current study was to examine how parents’ experiences with discrimination, depression, and their parenting practices are related to child internalizing and externalizing problems.

Parental contributions to child well-being have been thoroughly documented in the literature (e.g., Belsky, 1984). Importantly, parenting processes are situated in broader contexts (e.g., residential environment, culture, etc.; Bronfenbrenner, 1979). As an example, low-income families residing in high crime areas may institute harsher parenting practices to prevent the child from interacting with youth in the neighborhood (Boyd-Franklin & Karger, 2012; Pinderhughes & Hurley, 2008) and prevent feared consequences from law enforcement (Stevenson, Davis, & Abdul-Kabir, 2001). Within ethnic minority families, moreover, unique stressors may emerge (McLoyd, Hill, & Dodge, 2005), contributing to a pile-up effect of stressors that other low-income families may not be exposed to (Ungar, 2013). As theorized by Garcia-Coll et al. (1996), discrimination as a stressor, whether direct or subtle (i.e., microaggressions), affects the adaptive culture and familial practices of ethnic-minority families. With consideration of the associations between parental well-being, parenting, and child outcomes (Belsky, 1984), and the influence of the environment on parental functioning (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Garcia-Coll et al., 1996; McLoyd, 1990), it may be expected that low-income Black children whose parents experience racial discrimination may evince poor functioning (e.g., greater internalizing and externalizing behaviors).

Associations Between Depressive Symptoms and Parenting

As posited by McLoyd (1990) in the family stress model, parents who are experiencing psychological distress are less able to develop positive bonds with their children, oftentimes as a result of the punitive parenting techniques that are employed because of displaced stress. Furthermore, unique cultural stressors may account for low-income Black mothers reporting more depressive symptoms than low-income Hispanic and White mothers (O’Neil, Wilson, Shaw, & Dishion, 2009). In turn, increased reports of depressive symptoms have been associated with less desirable and inconsistent parenting practices and fewer opportunities for parents to develop positive relationships with their young children (Arellano et al., 2012). Conger et al. (2002) employed the family stress model in a sample of two-parent Black households from varying regions in the United States. For these parents, economic disadvantage led to psychological distress, which in turn, led to conflict among parents. Through parental conflict, parents were less likely to have positive bonds with their children. However, the findings regarding maternal depressive symptoms and the parent-child relationship have not been consistent. Brody and Flor (1998) examined maternal psychological functioning and family processes for single Black mothers living in rural areas. Maternal self-esteem, not maternal depressive symptoms, was related to mother-child relationship quality. Thus, while literature has provided evidence to support negative associations between depression and parenting characteristics, additional research is needed to understand the link between parental depression and parent-child relationships within Black families.

The Role of Parenting in Child Well-Being

Given that socialization processes (e.g., parenting and parent-child relationships) may be negatively influenced by parental emotional distress, young children are likely to be susceptible to parental functioning problems (Belsky, 1984; Bowen, 1966). Children of parents who experience depressed mood and employ less effective parenting practices often have greater difficulty regulating their own mood and actions (i.e., internalizing and externalizing problems; Brenner & Salovey, 1997; Silk, Shaw, Forbes, Lane, & Kovacs, 2006). Internalizing problems, or problems that affect the child’s internal psychological well-being rather than the outside environment (Liu, 2004), and externalizing problems, or problems that are shown in children’s outward behavior that affect the external environment (Liu, 2004), are problematic with regard to school readiness and in school and societal environments as children develop. Although some parenting styles are not uniformly associated with the same outcomes across cultures, including for low-income Black parents (Pinderhughes et al., 2000; Skinner et al., 2011; Sorkhabi & Mandara, 2013), there is general agreement that providing no limits (i.e., laxness) or being excessively emotional (i.e., overreactive) are not typically associated with positive child outcomes (Guajardo, Snyder, & Petersen, 2009; Leung & Slep, 2006).

McLoyd (1990) focuses on the pathways through which low economic status hinders development within Black families. Parents who are experiencing economic hardship are likely to exhibit punitive and coercive patterns of behavior toward their children (Ceballo & McLoyd, 2002; McLoyd, 1990). Furthermore, social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) would suggest that children replicate the actions and reactions of those around them, particularly the most proximal influences (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), thus, depressed parental mood and punitive parenting practices may contribute to child emotional (e.g., internalizing) and conduct (e.g., externalizing) problems.

Relations Between Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms

The association between discrimination—or the unjust prejudicial treatment of different categories of people or things—and increased internalizing appears to be robust in the research literature. In particular, young Black adults who experience discrimination report distress and depression (Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, & Zimmerman, 2003; Williams, Chapman, Wong, & Turkheimer, 2012) and poor health outcomes (Fuller-Rowell, Doan, & Eccles, 2012; Fuller-Rowell, Evans, & Ong, 2012). Additionally, various forms of discrimination may be more prevalent in today’s society compared with blatant discriminatory practices during prior eras (e.g., Jim Crow and Civil Rights). Although blatant discrimination (e.g., being called derogatory names, refusing service or entry etc.)—which is largely illegal—may occur infrequently, microaggressions, or subtle forms of discrimination that are nuanced and commonplace, can cause confusion and a sense of inferiority in Black adults (Sue et al., 2008). Furthermore, both blatant and subtle acts of discrimination have been linked to distress among Black people (Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Sue, Capodilupo, & Holder, 2008; Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000).

While young children may be less able to report discriminatory practices toward them (Gillen-O’Neel, Ruble, & Fuligni, 2011; Hughes et al., 2006; Quintana, 1998; Spears Brown & Bigler, 2005), the report of discrimination by others has been found to be associated with Black child internalizing (Simons et al., 2002) and externalizing (McNeil et al., 2014) problems. As indicated by Garcia-Coll et al. (1996), the sociocultural experiences within an environment can contribute to later child development through the parent. Given that racial discrimination may contribute to increases in parents’ symptoms of depression and anxiety (Brody et al., 2008), discrimination may indirectly contribute to later functioning in children.

Study Aims

The current study aims to contribute to a small but growing body of literature investigating the impact of parental discrimination on child functioning (McNeil et al., 2014; Riina & McHale, 2012) using a sample of low-income Black parents and their children. Parent reports of child externalizing and internalizing behaviors were considered as outcome variables. Since child emotional (e.g., internalizing) and conduct (e.g., externalizing) problem behaviors are frequently used both in research and practical settings to measure child well-being, the factors associated with these variables are of special interest for children whose initial emotional and behavioral levels are elevated (see study inclusion criteria).

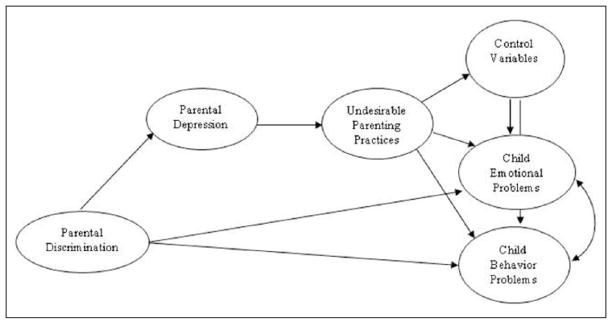

There was one primary question guiding our inquiry: Are parents’ experiences with discrimination related to later child psychosocial outcomes through the pathways of parent depression and parenting? Based on literature conceptualizing parental processes (e.g., Belsky, 1984; McLoyd, 1990) and systemic influences to familial functioning (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Garcia-Coll et al., 1996), we hypothesize that parental perceptions of racial discrimination will be positively associated with parental depressive symptoms, which in turn are expected to be positively associated with less desirable parenting behaviors and relationships, which in turn are expected to be positively associated with child emotional and conduct problems. In addition to the indirect pathways between parental discrimination and child functioning, we also hypothesize direct, positive associations between discrimination and child internalizing and externalizing variables as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

Method

Participants

Caregivers were parents of children recruited through the Early Steps multisite project of the Family Check-Up parenting intervention, which aimed to reduce the early emergence of externalizing and internalizing behaviors in young children (Dishion et al., 2008). Families with a child from 2 years, 0 months to 2 years, 11 months were recruited from Women, Infants, and Children Nutrition Program (WIC) centers in Eugene, Oregon; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and Charlottesville, Virginia between 2002 and 2003. Of the 1,666 families approached, 879 met eligibility criteria and 731 (83.2%) families consented for participation. Screening guidelines included families identifying above average child behavioral problems pertaining to socioeconomic status, family problems, and child behavior risk factors. The 731 participants enrolled in the study identified both themselves and children as European American, African American, Asian American, Native American, Hispanic, and biracial. Given the interest in racial discrimination specific to African American/Black families, the current study consists of the 163 Black primary caregivers living primarily in urban areas and their children at ages 5 and 7 (Waves 4 and 5, respectively).

Measures

A research team conducted assessments of parents during an annual 2.5-hour home visit. All assessments were conducted at most annually for each wave in the home beginning at age 2 with the primary parent, and if present, an alternative parent, such as a father or grandmother. The assessment involved the completion of questionnaires and parent-child interaction tasks, including free play and cleanup. At Wave 5, parents were asked to perform interactive tasks with their 7-year-old, complete additional questionnaires, and were compensated for their participation. Repeated measures were collected throughout the waves, moreover, the selection of measures for given ages (e.g., parental variables at child age 5 and child outcome variables at child age 7) reflect both the direction of expected change—that is, parent to child—and the anticipated advancement of children’s understanding of race-related issues over time and reflected in behaviors emphasized by school environments (Quintana, 1998).

Demographics Questionnaire

The Demographic Questionnaire assessed demographic characteristics of the family, such as annual income, parent education, and target child gender. At age 7 data collection, just over half of the children were female (53.4%; N = 87) while the vast majority of the parents (96.9%, N = 158) were female and ranged in age from 22 to 62 years (M = 32.15, SD = 7.58). Of the parents, 49.7% had attained a high school degree or less and 66.3% identified as single. With respect to income, 60.9% of the sample earned less than $20,000 per year. Please refer Table 1 for additional demographic information.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Primary Parents (PC) and Target Child (TC).

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| TC gender | ||

| Male | 76 | 46.6 |

| Female | 87 | 53.4 |

| PC education level | ||

| High school or less | 81 | 49.7 |

| Partial college or more | 82 | 50.3 |

| Family intervention status | ||

| Intervention | 78 | 47.9 |

| Control | 85 | 52.1 |

| PC annual gross income ($) | ||

| ≤19,999 | 95 | 60.9 |

| ≥20,000 | 68 | 39.1 |

Discrimination/Microaggression Scale

The Microaggression Scale (adapted from Walters, Simoni, & Evans-Campbell, 2002 is a nine-item measure assessing experiences of ethnic/racial discrimination from others. Parents rated the frequency of discrimination in specific situations at child age 5 (e.g., “Have you ever been expected to act in a stereotypical manner because of your ethnicity/race?”) on a 5-point scale ranging from almost never to almost always. High reliability (α = .87) was reported among the items.

Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression

The Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item measure of depressive symptoms with scoring based on the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV). Parents rated how frequently an event occurred during the past 2 weeks (e.g., “I had crying spells”) on a 4-point scale that ranged from rarely or none of the time (0–1 day) to most or all of the time (5–7 days). High reliability (α = .91) was reported for the total score. This measure was assessed at child age 5.

Parenting Scale

The Parenting Scale (PS; Arnold, O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker, 1993) is a 30-item measure that assesses discipline techniques that parents use, yielding three factors: laxness, overreactivity, and verbosity (Arnold et al., 1993). Participant responses ranged on a scale from 1 to 7 on a variety of items (e.g., “at meal times, I let my child decide how much to eat” (1) to “I decide how much my child eats” (7).) For the present study, only the overreactivity and laxness factors, which describe items related to the parent’s emotional reactivity and consistency in responding to the child’s behavior, respectively, were used. High reliabilities for both factors (αs > .80) were established, while the verbosity subscale fit poorly with this low-income Black sample (α = .47), which is consistent with other studies that exclude verbosity because of poor fit in Black samples (Steele, Nesbitt-Daly, Daniel, & Forehand, 2005). The PS was assessed at child age 5.

The Adult-Child Relationship Scale

The Adult-Child Relationship Scale (adapted from the Student-Teacher Relationship Scale; Pianta & Nimetz, 1991), assesses the quality of the parent’s perception of the relationship with the child. A 5-point scale (1 = definitely NOT; 5 = definitely) was used to gauge beliefs on parent-child relationship (e.g., “This child and I always seem to be struggling with each other.”) Two factors (Positive Relationship [reverse-coded] and Conflict in Relationship) were utilized from this measure to yield a total score. Acceptable reliability (α = .80) was established within this sample. This measure was assessed at child age 5.

Child Behavior Checklist

The Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2004) assesses parental beliefs of children’s behavioral (i.e., externalizing) and emotional (i.e., internalizing) problems and competencies. Seventy-three items measured problems and three open-ended items were provided for additional problems. A 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true) was used to assess parental perceptions of child behavior (e.g., “My child is inattentive or easily distracted”). With regard to externalizing/conduct behavior problems, examples of items include cruelty, bullying, or meanness to others and gets in many fights. On the other hand, items assessing internalizing/emotional problems include feels worthless or inferior and too fearful or anxious. High reliabilities for both subscales (αs < .90) have been established in multiple studies with low-income and diverse populations (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2004). Parents provided responses at child age 7.

Design and Analyses

The current study examined the associations between racial discrimination, parental functioning and behaviors, and child outcomes. Structural equation modeling was used with Mplus Version 7 to evaluate the fit of our hypothesized model and to examine whether parental experiences with discrimination were related to children’s emotional and behavioral problems directly and indirectly through parent depression and parenting behaviors. Structural equation modeling was applied to test the conceptual model through relational paths while accounting for measurement errors. Bias corrected bootstrapping was used and standardized asymmetrical confidence intervals were created with 5,000 bootstrapped iterations to account for missing data and limited sample size. Comparative fit index (CFI) values greater than or equal to .95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values equal to or less than .06, and standardized root mean residual (SRMR) values equal to or less than .08 were used as indicators of good model to data fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Table 2 shows the correlation matrix with means and standard deviations for the study variables. Emotional and behavioral problems were highly correlated (r = .65), so the variables were allowed to covary within the model rather than being examined separately.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Study Variables (N = 163).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | — | ||||||

| 2 | .299** | — | |||||

| 3 | .027 | .201* | — | ||||

| 4 | .065 | .158 | .344** | — | |||

| 5 | .073 | .424** | .329** | .403** | — | ||

| 6 | .307** | .365** | .154 | .235** | .372** | — | |

| 7 | .151 | .322** | .152 | .331** | .474** | .650** | — |

| M | 1.67 | 15.04 | 3.13 | 2.82 | 33.79 | 55.05 | 59.62 |

| SD | .77 | 9.86 | 1.10 | .86 | 8.94 | 10.80 | 11.56 |

Note: 1= racial discrimination (MIC); 2 = depressive symptoms (CES-D); 3 = parental laxness (PS); 4 = parental overreactivity (PS); 5 = adult and child relationship (ACRS); 6 = child emotional problems (CBCL); and 7 = child behavior problems (CBCL). MIC = Microaggression; CESD = Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression; PS = Parenting Scale; ACRS = Adult-Child Relationship Scale; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Preliminary analyses were conducted to examine whether the study variables differed by income, intervention group, and child gender. Significant differences were found for parent depression by child gender. Parents of female children reported significantly greater depressive symptoms than parents of male children (M = 16.34, SD = 10.97; M = 13.92, SD = 8.65; p < .01). To account for the differences between groups and improve ecological validity, annual income, child gender, and intervention status were included as control variables in the initial model. No hypothesized control variables were significant in the final model, however, and thus were removed as covariates in the final analysis.

Results

Preliminary Analysis: Descriptive Statistics

Black participants reported fairly low levels of discrimination and microaggressions (M = 1.67, SD = .77). Although the focus of the current study is on the Black subsample within the Early Steps project, it is important to note that the discrimination scores were significantly higher than the White sub-sample within the larger study (N = 310, M = 1.24, SD = .46, p < .001). The reports of children’s emotional problems (M = 55.05, SD = 10.80) and behavioral problems (M = 59.62, SD = 11.58) were both considered normative with respect to clinical standards, although the mean score of behavioral problems was close to the “at-risk” criteria of T = 60.

Parents reported experiencing depression at a rate just below the threshold of 16 on the CES-D for clinical significance, although there was notable variation in depressive symptomatology (M = 15.04, SD = 9.86). Parents reported moderately low lax (M = 3.13, SD = 1.10) and overreactive parenting behaviors (M = 2.82, SD = .86), and perceived having average relationships with their child (M = 33.79, SD = 8.94). After mean scores were recorded, variables were centered to adjust for statistical collinearity between constructs.

Model-Fit Testing

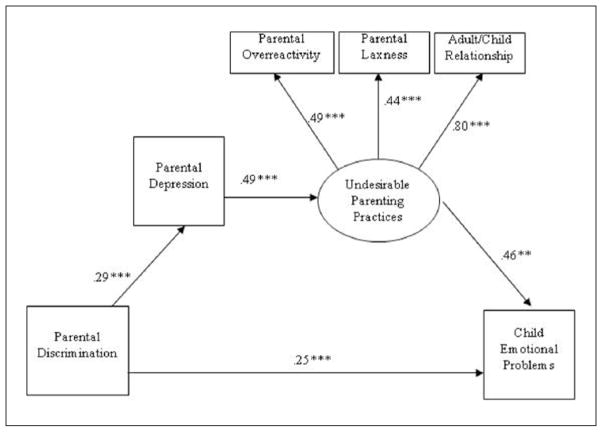

Although model fit was acceptable for the hypothesized model (p = .27; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .04), the path between parental discrimination and child problem behaviors (e.g., externalizing problems) was found to be nonsignificant. This path was subsequently removed, and the reduced model with child emotional problems (e.g., internalizing problems; Figure 2) demonstrated excellent model fit, χ2(11, N = 163) = 13.58, p = .26; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .04.

Figure 2.

Statistical model for relationships between discrimination, depression, parenting, and child emotional problems.

***p < .001.

Direct and Indirect Effects

The direct relationship between parent reports of discrimination and subsequent child adjustment was tested. Parent reported discrimination was positively related to children’s emotional problems (β = .25, p < .01). The association between discrimination and child emotional problems via parent functioning was also tested. As predicted, parent discrimination positively predicted parent’s depressive symptoms (β = .29, p < .001), and depressive symptoms were positively associated with undesirable parenting behaviors (β = .39, p < .001). Similarly, undesirable parenting behaviors were positively associated with child internalizing problems (β = .59, p < .001). The model also showed significant indirect effects for the pathways from discrimination, depression, and parenting to emotional problems (β = .07, p = .01), and was affirmed by the bias corrected standardized confidence intervals (95% confidence interval = [.035, .123]). Thus, greater reports of discrimination were associated with greater child emotional problems (i.e., internalizing problems) through higher levels of depressive symptoms and undesirable parenting behaviors.

Discussion

Racial discrimination can be a major stressor for Black people, and it is critical to understand how parents’ experiences with discrimination—like other stressors and hassles—might directly and/or indirectly contribute to child well-being. The current study evaluated how low-income Black parents’ experiences with discrimination contribute to children’s psychosocial outcomes. Consistent with other research, we found that parent self-reported levels of discrimination were directly related to Black children’s emotional symptoms (Simons et al., 2002). Additionally, as a novel contribution to the literature, parental discrimination was found to be indirectly related to child emotional problems via parental depression and parenting practices. Specifically, a greater perception of discrimination was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, which were in turn associated with less effective parenting practices and, subsequently, higher levels of child internalizing problems. Our findings, therefore, suggest that children can be both directly and diffusely exposed to the effects of discrimination.

Although all families can experience difficulty in psychosocial well-being and socialization practices, ethnic-minority families in the United States may have particular challenges related to their ethnic and racial status. Historical and systemic factors may contribute to more frequent experiences of discrimination relating to financial and ethnic status. Consequently, in order to fully understand the development of minority children, it is critical to incorporate these factors given their potential direct and indirect impact on child well-being (Garcia-Coll et al., 1996). Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological theory posits that youth development may be most affected by proximal processes that occur in immediate, microsystem environments (e.g., parent-child relationships). However, the systems perspective also recognizes that exosystem-level contexts that parents inhabit directly that youth do not, as well as macrolevel factors contributing to the persistence of social stratification and racism, can shape the nature of the proximal parent-child interactions and therefore indirectly influence child well-being. Our study affirms this model by identifying that mechanisms through which discrimination was indirectly associated with child outcome were parent depression and parenting practices. That is, we found greater parent depressive symptoms yielding inconsistent and less desirable parenting practices, which led to poorer child outcomes (Arellano et al., 2012; Belsky, 1984; Wade et al., 2012).

The finding that Black youth’s internalizing problems (e.g., depression and anxiety) were associated with familial-level discrimination is consistent with prior literature (Ford, Hurd, Jagers, & Sellers, 2013; Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004; Riina & McHale, 2012). Importantly, we assessed child outcomes at age 7, which leaves open the possibility that the indirect effects of parents’ experiences with discrimination may contribute cumulatively to toxic levels of stress in the child’s environment as they get older (Evans & Kim, 2013). Indeed, there is evidence that cumulative risk factors like family turmoil and harsh parenting can be considered as mediators of the relation between living in chronic poverty and negative physiological outcomes (e.g., chronic dysregulation of cortisol and other factors, as measured by high allostatic load; Evans & Kim, 2007). As we found in our study, exposure to racial discrimination directly contributed to parental depressive symptoms and negative parenting practices, which can be considered as indictors of cumulative risk. Moreover, there is growing evidence that even as young as age 7, ethnic minority children are aware of negative stigmas associated with their racial group membership (Gillen-O’Neel et al., 2011). Thus, research on cumulative stress in Black families should consider racial discrimination as a critical factor that may negatively impact child outcomes both directly and indirectly through multiple pathways.

Although we did not find a direct association between parental discrimination and child externalizing problems, there is evidence in the literature that notes the link between discrimination and youth conduct problems. Brody et al. (2006) found that discrimination against young adolescents resulted in both conduct and emotional problems, however, less is known about the transmission of discriminatory processes from parent to child. Thus, while our study did not result in associations between parental well-being and child conduct problems, it is conceivable that child age and/or gender may unearth problems for the child in the future because of lack of support, frequency of environmental discrimination, and changing relationship between parent and child. Additionally, given that Black families are not monolithic, it is of interest that McNeil et al. (2014) found evidence for child externalizing problems in middle-class Black families, whereas our study only identified problems related to child internalizing symptoms with low-income families. It is worthwhile to investigate how economic and ecological systems influence the functioning of Black families; furthermore, how discrimination manifests in children of varying economic backgrounds via parental well-being.

Limitations

Our study findings should be interpreted in the context of methodological limitations. The sample size was relatively small; however, we were intentional about exploring Black participants’ experiences separately from other ethnic-minority families within our sample given their unique sociocultural history in the United States. Additionally, measurement of the variables, particularly those that are based on perceptions of racial discrimination, were limited to the perspective of the participant. Actual discriminatory experiences, for example, may not be accounted for if participants perceive discrimination as a result of chronic community exposure (Simons et al., 2002). Conversely, discrimination may be overreported if participants are more sensitive to racial concerns because of their ethnic identity (Shelton & Sellers, 2000). It should be noted, however, that parent reports of their own experiences with discrimination were not correlated with their perceptions of their child’s experiences with discrimination.

Finally, Black families were examined as a whole, however, previous literature notes differences in several of the variables (e.g., discrimination and parenting) based on residential location (e.g., urban vs. rural; Anderson, Wilson, Shaw, & Dishion, 2011; Wilson et al., 2009). Families may be more likely to face racial discrimination in certain environments compared to others, thus, it is critical to understand which communities may foster differing experiences of discrimination. Given that our sample size precluded the division of families between multiple sites, it would be of interest to examine these differences within larger multi-site studies.

Conclusions and Directions for Future Research

For purposes of the current study, child gender was treated as a control variable, however, parenting practices (Hill, 2006; Mandara, Varner, & Richman, 2010) and conduct problems (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Florsheim, Tolan, & Gorman-Smith, 1996) have been shown to vary by gender. An extension of this work could be to assess the differences within externalizing problems between ethnic minority boys and girls, given differences in parenting and experience with discrimination (Brody et al., 2006). Indeed, the socialization experiences of Black boys has been found to differ from that of Black girls, particularly around the intersection of race and gender (Brown, Barbarin, & Scott, 2013; Hill, 2006).

Similarly, parental gender should be explored in future research. Since the vast majority of primary parents were female, perceived racial discrimination cannot be generalized across sexes. The unique perspective of Black fathers, as a result of the intersectionality of gender and race experiences, may provide different accounts of discrimination from that of Black mothers (Thomas, Barrie, & Tynes, 2009; Thomas, Caldwell, & DeLoney, 2012). Same-sex couples with intersecting identities (e.g., ethnic minority and gay) may also provide interesting perspectives on cumulative forms of discrimination and perspectives of child outcomes.

Although this study did not include racial socialization, future research would greatly benefit from the inclusion of socialization in sociocultural studies involving parental transmission of discriminatory experiences. Racial socialization is the developmental process by which parents shape their children’s knowledge about their own race as it relates to personal and group identity, intergroup and interindividual relationships, and position in the social hierarchy (Thornton, Chatters, Taylor, & Allen, 1990). Although racial socialization has been examined as a moderator between negative adolescent outcomes and racial discrimination (Hughes et al., 2006; Neblett, Terzian, & Harriott, 2010; White-Johnson, Ford, Sellers, & 2010), less is known about the effects of racial discrimination on young children. While older children may be explicitly socialized for experiences of racial discrimination, parents of younger children may be less prepared or feel less equipped to talk about discrimination (Peters, 1985). Indeed, research has shown that ethnic minority families typically begin socializing children at age 7 (Hughes et al., 2006), thus, children may enter into larger social settings (e.g., school, neighborhoods, etc.) without an understanding of their emotions associated with racial encounters. This study helps to illuminate some of the problems associated with racial discrimination in familial processes involving young children.

Finally, further exploration of racial discrimination more generally within ethnic populations would be of great benefit. The microaggression scale measure assesses only the frequency of discriminatory experiences. It would behoove researchers to be aware of other elements of the experiences, such as the type and duration, thus mixed methodology in future studies may improve investigators’ knowledge of causal pathways. Qualitative data collection and experimental methodology may improve our understanding of discriminatory experiences and perceptions and contribute to more precise measurement.

Understanding sociocultural and familial factors that impact Black children’s psychological well-being is especially important since they underutilize psychological services (Broman, 2012) and face greater rates of suspension than their peers (Kaushal & Nepomnyaschy, 2009). This study suggests that intervening in familial processes related to parental well-being may be a worthwhile attempt at decreasing both parental depression and school-age children’s emotional problems, which may help to address the differential diagnoses and disparities within schools and mental health care services for Black youth. Further research and applied methods are also necessary to decrease discriminatory experiences that can cause parental and child emotional problems in Black families.

Our work indicates a need to consider how to effectively bolster components of familial interventions with low-income Black families to address issues of discrimination directly. Even with fairly low levels of perceived discrimination reported, the direct association between discrimination and child emotional problems conveys the need for additional clinical and intervention responses that address more than just depressive symptoms and parenting struggles. Although the current project did not differentiate families reporting varying levels of discrimination, depression, and/or parenting problems, the high variability in responses indicates a line of future study that investigates the potential impact of discrimination on these variables with relatively average group-means (e.g., a profile approach). Community based participatory research and clinicians within at-risk communities should engage local leaders to determine whether discrimination is perceived as problematic, and assess ways that the communities themselves feel solutions can be reached. Working collaboratively with those who are experiencing the effects of discriminatory practices not only enables participants to contribute to their well-being, but also informs the practitioners of additional ways that their interventions can be adapted to account for the needs of community members. It is our hope that this study contributes to an understanding of the potentially damaging associations with discrimination and encourages more efforts to decrease the painful outcomes in Black children’s emotional well-being.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported in part by a grant from National Institute on Drug Abuse–DA022772.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. The Achenbach system of empirically based assessment (ASEBA) for ages 1.5 to 18 years. In: Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Vol.2. Instruments for children and adolescents. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 179–213. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R, Wilson M, Shaw D, Dishion T. Unpublished master’s thesis. University of Virginia; Charlottesville, VA: 2011. Demographic factors impacting parenting style in low-income families. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano PAE, Harvey EA, Thakar DA. A longitudinal study of the relation between depressive symptomatology and parenting practices. Family Relations. 2012;61:271–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00694.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DS, O’Leary SG, Wolff LS, Acker MM. The parenting scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Oxford, England: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen M. The use of family theory in clinical practice. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1966;7:345–374. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(66)80065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N, Karger M. Intersections of race, class, and poverty: Challenges and resilience in African American families. In: Walsh F, editor. Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 273–296. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner EM, Salovey P. Emotion regulation during childhood: Developmental, interpersonal, and individual considerations. In: Salovey P, Sluyter DJ, editors. Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1997. pp. 168–192. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen YF, Kogan SM, Murry VM, Logan P, Luo Z. Linking perceived discrimination to longitudinal changes in African American mothers’ parenting practices. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen YF, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL. Maternal resources, parenting practices, and child competence in rural, single-parent African American families. Child Development. 1998;69:803–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL. Race differences in the receipt of mental health services among young adults. Psychological Services. 2012;9:38–48. doi: 10.1037/a0027089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist. 1979;34:844–850. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Barbarin O, Scott K. Socioemotional trajectories in Black boys between kindergarten and the fifth grade: The role of cognitive skills and family in promoting resiliency. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83(2 Pt. 3):176–184. doi: 10.1111/ajop.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo R, McLoyd VC. Social support and parenting in poor, dangerous neighborhoods. Child Development. 2002;73:1310–1321. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty and health cumulative risk exposure and stress dysregulation. Psychological Science. 2007;18:953–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self-regulation, and coping. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Family processes and risk for externalizing behavior problems among African American and Hispanic boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1222–1230. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford KR, Hurd NM, Jagers RJ, Sellers RM. Parent experiences of discrimination and African American adolescents’ psychological health over time. Child Development. 2013;84:485–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell TE, Doan SN, Eccles JS. Differential effects of perceived discrimination on the diurnal cortisol rhythm of African Americans and Whites. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell TE, Evans GW, Ong AD. Poverty and health: The mediating role of perceived discrimination. Psychological Science. 2012;23:734–739. doi: 10.1177/0956797612439720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, McAdoo HP. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen-O’Neel C, Ruble DN, Fuligni AJ. Ethnic stigma, academic anxiety, and intrinsic motivation in middle childhood. Child Development. 2011;82:1470–1485. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guajardo NR, Snyder G, Petersen R. Relationships among parenting practices, parental stress, child behaviour, and children’s social-cognitive development. Infant and Child Development. 2009;18:37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE. Disentangling ethnicity, socioeconomic status and parenting: Interactions, influences and meaning. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2006;1:114–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal N, Nepomnyaschy L. Wealth, race/ethnicity, and children’s educational outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:963–971. [Google Scholar]

- Lee DL, Ahn S. The relation of racial identity, ethnic identity, and racial socialization to discrimination-distress: A meta-analysis of Black Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;60:1–14. doi: 10.1037/a0031275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung DW, Slep AM. Predicting inept discipline: The role of parental depressive symptoms, anger, and attributions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:524–534. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Childhood externalizing behavior: Theory and implications. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2004;17:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2004.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandara J, Varner F, Richman S. Do African American mothers really ‘love’ their sons and ‘raise’ their daughters? Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:41–50. doi: 10.1037/a0018072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Hill NE, Dodge KA. Introduction: Ecological and cultural diversity in African American family life. In: McLoyd VC, Hill NE, Dodge KA, editors. African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil S, Harris-McKoy D, Brantley C, Fincham F, Beach SR. Middle Class African American mothers’ depressive symptoms mediate perceived discrimination and reported child externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23:381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Terzian M, Harriott V. From racial discrimination to substance use: The buffering effects of racial socialization. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4:131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil J, Wilson MN, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ. The relationship between parental efficacy and depressive symptoms in a diverse sample of low income mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2009;18:643–652. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9265-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MF. Ethnic socialization of young Black children. In: McAdoo HP, McAdoo JL, editors. Black children: Social, educational, and parental environments. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1985. pp. 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Nimetz SL. Relationships between children and teachers: Associations with classroom and home behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1991;12:379–393. [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Hurley S Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Disentangling ethnic and contextual influences among parents raising youth in high-risk communities. Applied Development Science. 2008;12:211–219. doi: 10.1080/10888690802388151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Zelli A. Discipline responses: Influences of parents’ socioeconomic status, ethnicity, beliefs about parenting, stress, and cognitive-emotional processes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:380–400. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM. Children’s developmental understanding of ethnicity and race. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 1998;7:27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Riina EM, McHale SM. Adolescents’ experiences of discrimination and parent-adolescent relationship quality: The moderating roles of sociocultural processes. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33:851–873. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11423897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone K, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Connell A, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, Gardner F. Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:417–439. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Sellers RM. Situational stability and variability in African American racial identity. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Lane TL, Kovacs M. Maternal depression and child internalizing: The moderating role of child emotion regulation. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:116–126. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Murry V, McLoyd V, Lin K, Cutrona C, Conger RD. Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: A multilevel analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:371–393. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner ML, MacKenzie EP, Haggerty KP, Hill KG, Roberson KC. Observed parenting behavior with teens: Measurement invariance and predictive validity across race. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:252–260. doi: 10.1037/a0024730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkhabi N, Mandara J. Are the effects of Baumrind’s parenting styles culturally specific or culturally equivalent? In: Larzelere RE, Morris AS, Harrist AW, editors. Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Spears Brown C, Bigler RS. Children’s perceptions of discrimination: A developmental model. Child Development. 2005;76:533–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele RG, Nesbitt-Daly JS, Daniel RC, Forehand R. Factor structure of the Parenting Scale in a low-income African American sample. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14:535–549. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Davis G, Abdul-Kabir S. Stickin’ to, watchin’ over, and gettin’ with: An African American parent’s guide to discipline. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Holder AMB. Racial microaggressions in the life experience of Black Americans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39:329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Nadal KL, Capodilupo CM, Lin AI, Torino GC, Rivera DP. Racial microaggressions against Black Americans: Implications for counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2008;86:330–338. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Barrie R, Tynes BM. Intimate relationships of African Americans. In: Neville HA, Tynes BM, Utsey SO, editors. Handbook of African American psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Caldwell CH, De Loney EH. Black like me: The race socialization of African American boys by nonresident fathers. In: Sullivan JM, Esmail AM, editors. African American identity: Racial and cultural dimensions of the Black experience. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books/Rowman & Littlefield; 2012. 249 pp.272 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton MC, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Allen WR. Sociodemographic and environmental correlates of racial socialization by Black parents. Child Development. 1990;61:401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. Family resilience and at-risk youth. In: Becvar DS, editor. Handbook of family resilience. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. pp. 137–152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wade C, Giallo R, Cooklin A. Maternal fatigue and depression: Identifying vulnerability and relationship to early parenting practices. Advances in Mental Health. 2012;10:277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell T. Substance use among American Indians and Alaska natives: Incorporating culture in an “indigenist” stress-coping paradigm. Public Health Report. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S104–S117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White-Johnson R, Ford KR, Sellers RM. Parental racial socialization profiles: Association with demographic factors, racial discrimination, childhood socialization, and racial identity. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:237–247. doi: 10.1037/a0016111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Williams-Morris R. Racism and mental health: The African American experience. Ethnicity & Health. 2000;5:243–268. doi: 10.1080/713667453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MT, Chapman LK, Wong J, Turkheimer E. The role of ethnic identity in symptoms of anxiety and depression in African Americans. Psychiatry Research. 2012;199:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MN, Hurtt CL, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Gardner F. Analysis and influence of demographic and risk factors on difficult child behaviors. Prevention Science. 2009;10:353–365. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0137-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]