Abstract

Introduction

We compared the gestational weight gains of black and white women with the 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations to better understand the potential for successful implementation of them in clinic settings.

Methods

We abstracted prenatal and delivery data for 2760 18-40 year-olds with term singleton deliveries in 2004-2007. We examined race differences in mean trimester gains with adjusted linear regression and race differences in the distribution of women who met the IOM recommendations with chi-square analyses. We stratified all analyses by pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI).

Results

Among normal-weight and obese women, black women gained less weight than white women in the first and second trimesters. Overweight black women gained significantly less than white women in all trimesters. In all BMI categories, for both races, a minority of women (range, 9.9-32.4%) met the IOM recommended gains for the second and third trimesters. For normal-weight, overweight and obese black and white women, 49-80% exceeded the recommended gains in the third trimester, with higher rates of excessive gain for white women.

Discussion

Less than half of the sample gained within the IOM recommended ranges, in all BMI groups, and in all trimesters. The risk of excessive gain is higher for white women. For both races, excessive gain begins by the second trimester, suggesting that counseling about the importance of weight during pregnancy should begin earlier, in the first trimester or prior to conception.

Keywords: body weight, pregnancy, pregnant women, prenatal care

Excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) is associated with gestational diabetes, hypertension, cesarean delivery, and long-term weight retention for women.1-4 Offspring health is also associated with GWG. In a study of 20,456 non-diabetic term singleton births, excessive maternal GWG (compared with normal weight gain) was associated with delivery of infants who had lower 5-minute Apgar scores, higher risks for seizure, hypgoglycemia, and were large for gestational age.5 Insufficient GWG, compared with normal weight gain, was associated with an increased risk of delivery of infants who were small for gestational age (SGA), experienced seizures, and were hospitalized for more than five days.5

To reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended optimal ranges of GWG based on maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) in 1990.6 In 2009, the IOM revised its GWG guidelines using body mass index cupoints from the World Health Organization7 to replace those derived from the Metropolitan Life Insurance Table. These new cutpoints result in fewer women being classified as underweight and more classified as overweight.8,9 The revised guidelines also included an upper limit of recommended GWG for obese women and mean ranges for weekly recommended gains, by pre-conception BMI, during the second and third trimesters.8 Importantly, the 2009 report reversed its 1990 recommendation that black women and adolescents should strive for total GWG in the upper half of recommended ranges, citing insufficient evidence to support any variation in recommendations based on maternal age or race. For example, several investigators have reported that, while black women had smaller infants than white women, gains in the upper half of the recommended ranges did not significantly decrease their risks for delivery of low birthweight (LBW) and/or SGA infants.10-14

Although differential GWG may not explain black-white differences in infant birthweight, race differences in GWG have been observed, with obese and overweight white women more likely than their black peers to gain more weight than recommended.13,14 Further, there are race differences in pre-pregnancy weight, which could influence fetal growth: black women are more likely than white women to enter pregnancy overweight or obese.15

The purpose of our study was to examine whether there were differences in total and trimester-specific weight gains for black and white women with singleton term births. We also wanted to determine how black and white women gained in comparison to the BMI-specific trimester gains outlined in the 2009 IOM guidelines.8

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

In 2008, we obtained prenatal and delivery data from outpatient medical records from two sources, a large managed care organization and four urban community clinics that serve a high proportion of minority women. All were located in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area. We reviewed the medical records of women with an estimated due date (EDD) between April 2004 and March 2008. Of 9466 prenatal records (8853 from the managed care system and 613 from the community clinics), 6599 records were from women who met our initial eligibility criteria: they were between 18 and 40 years of age at the time of the last menstrual period (LMP) and had delivered a singleton live infant between 37 and 42 weeks gestation based on the EDD or a first trimester ultrasound (if available). We excluded all records that lacked adequate data on measured weight and height; 918 records lacked at least two prenatal weight measurements and 152 records lacked a height measurement. Of the remaining 5529 records in the sample, we excluded 1476 that lacked a baseline prenatal/pre-conception weight measurement, documented in the medical record within 90 days either before or after the LMP, or a final prenatal weight, measured within 14 days of delivery. Thus, of the 6599 eligible records, 4053 records (61% of the total reviewed) had complete data for analysis. Women who were excluded because of insufficient weight data did not vary significantly (P≤.05) by race from included women. For those for whom comparisons were possible, those who had limited weight data did not vary significantly from the included women in GWG or baseline BMI. Our analyses were limited to non-Hispanic black and white women, so we excluded Asian (n=317), Hispanic (n=250), Native American (n=23), multi-racial/bi-racial/other (n=105) women and women who were missing data on race or Hispanic ethnicity (n=598). This resulted in a final sample of 2760 women. The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Minnesota and HealthPartners Research Foundation approved the study protocol.

Study Variables

The primary outcome variables were total measured GWG and the amount of measured weight gained in each trimester of pregnancy. The first measured baseline weight was within 90 days of the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP); 5% were prior to the LMP, 19% were in the first 30 days after the LMP, and 48% were 31 to 60 days after the LMP. On average, the baseline weight was 43.7 days (29.2 SD) after the LMP. The last measured prenatal weight was within 14 days of delivery; 93% were within 7 days of delivery. On average, the last measured weight was 3.6 days (2.7 SD) before delivery. We defined GWG as the difference between the last measured prenatal weight and the measured baseline weight. First trimester weight gain was defined as the difference between the measured weight at the end of week 12 and the measured baseline weight. Second trimester gain was the difference between measured weights at 27 weeks and 13 weeks. Third trimester weight gain was the difference between the last measured prenatal weight and the measured weight at the beginning of week 28.

Since the timing of prenatal visits and associated weight measurements varied among women, we used locally weighted regression analysis to predict gestational weight gain at the start and end of a trimester. Prenatal weights measured closer to those points carried a higher weight in the prediction.16 Differences in the number of prenatal visits between black and white women could have resulted in differences in the quality and/or number of prenatal weights available for analyses. However, we found no significant differences in the mean number of visits between black and white women (12.3 vs. 12.7, respectively). Both groups had a median of 12 visits and similar spacing of visits.

The secondary outcomes were whether trimester gains fell within the 2009 IOM recommendations for weekly gains in the second and third trimesters by baseline BMI (ie, underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese).8 To convert the IOM ranges for weekly weight gains into recommendations for total trimester gains in the second and third trimesters, we multiplied the upper and lower bound of the recommended range by the number of weeks in the applicable trimester. We calculated BMI-specific ranges for first trimester gain by taking the difference between the IOM recommendations for total gain and the sum of the second and third trimester gains. Table 1 shows the ranges we used to define meeting the IOM recommendations.

Table 1.

Ranges for Recommended Total and Trimester Gestational Weight Gain in pounds, by Maternal Baseline Body Mass Index BMI), based on 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Guidelinesa

| Baseline Body Mass Index | Total Gain, lbs | First Trimester Change, lbs | Second Trimester Gain, lbs | Third Trimester Gain, lbs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 28 – 40 | 0 – 3.6 | 15 – 19.5 | 13 – 16.9 |

| Normal Weight (18.5 – 24.9) | 25 – 35 | 2.6 – 7 | 12 – 15 | 10.4 – 13 |

| Overweight (25.0 – 29.9) | 15 – 25 | 1 – 5.4 | 7.5 – 10.5 | 6.5 – 9.1 |

| Obese (≥ 30.0) | 11 – 20 | (−) 0.2 – 3.2 | 6 – 9 | 5.2 – 7.8 |

Abbreviations: Body mass index, BMI; Institute of Medicine, IOM; lbs, pounds; wk, week.

The IOM Guidelines assume a 1.1 to 4.4 pound weight gain during the first trimester for all BMI categories. They specify a mean range by BMI category in pounds per week (lbs/wk) for second and third trimesters as follows: underweight 1 to 1.3 lbs/wk, normal weight 0.8 to 1 lbs/wk; overweight 0.5 to 0.7 lbs/wk; and obese 0.4 to 0.6 lbs/wk. In this table, ranges for meeting IOM Guidelines are calculated based on 15 weeks in the second trimester (weeks 13-27) and 13 weeks in the third trimester (weeks 28-40), multiplied by the upper and lower values of the IOM recommended ranges. First trimester weight change is calculated by taking the difference between the IOM recommendations for total gain and the sum of the calculated second and third trimester gains. Our first trimester weight gains are slightly different than those assumed by the IOM as a result of this calculation.

We chose the following independent variables because of their association with GWG: baseline BMI, height, parity, infant sex, infant birth weight (grams), infant gestational age at birth (weeks), prenatal smoking status, partnered status, and insurance status.1,12,14,15 These variables were either self-reported or clinician-reported in the medical records. Race was self-reported and assessed according to standard categories:18 “black” refers to those who reported they were non-Hispanic black/African-American and “white” refers to those who reported they were non-Hispanic white. We calculated baseline BMI using measured weight and height (kg/m2) within 90 days of the LMP. We categorized women into the four baseline BMI groups outlined in the 2009 IOM report: underweight (BMI<18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5-24.9), overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9), and obese (BMI>30).8 Partnered status was dichotomized as either married/partnered or single/divorced/widowed. Insurance type was categorized as employer-based, government-based, or none. Women were categorized as smokers if they had documentation of self-reported smoking at any time during the prenatal period. We dichotomized parity as either nulliparous or multiparous prior to delivery of the study infant.

Statistical Analysis

We examined race differences in sample characteristics and infant outcomes with t-tests and chi-square statistics. We compared individual trimester gains for black and white women to the 2009 IOM recommendations7 with chi-square tests to evaluate differences in insufficient, recommended, and excessive gains. We also examined race differences in trimester gains for all women and for women stratified by baseline BMI with linear regression, adjusted for age at conception , height, baseline BMI (continuous), parity, prenatal tobacco use, previous trimester(s) gain, infant sex, and weeks gestation at delivery. To assess the independent role of race in mean GWG, we also conducted multivariate analyses that included race and the previously listed covariates. We used SAS 9.1 software package (SAS Institute INC. Cary, NC) and considered P ≤ .05 to be statistically significant in all analyses.

RESULTS

Black women were younger and taller, while white women were more likely to be married or partnered, smoke during pregnancy, and receive employer-based insurance (Table 2). Approximately half of the white women in this sample were nulliparous (54%), compared to only 35% of black women. Nearly half of the white women in the sample (47%) entered pregnancy at a normal weight. Black women were significantly more likely than white women to enter pregnancy as overweight (30% vs 28%) or obese (34% vs 24%). White women gained a mean total of 6.7 pounds more than black women during pregnancy.

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics and Infant Outcomes of 2760 Black and White Women who Delivered Term Infants

| Characteristics | Black Women (n = 717) | White Women (n = 2043) | Total (n = 2760) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sample characteristics

|

||||

| Age at conception, mean (SD), y | 26.9 (5.4) | 28.5 (5.2) | 28.1 (5.3) | < .0001 |

| Married or living with a partner, (%)b | 48.5 | 70.6 | 64.5 | < .0001 |

| Insurance status, (%) | < .0001 | |||

| Employer based | 41.3 | 82.4 | 71.7 | |

| Government based | 50.6 | 11.0 | 21.3 | |

| None | 8.1 | 6.7 | 7.0 | |

| Employer based | ||||

| Government based | ||||

| None | 8.1 | |||

| Nulliparous, (%) | 34.6 | 53.9 | 48.8 | < .0001 |

| Baseline weight, mean (SD), lbs | 167.8 (45.9) | 160.5 (37.3) | 162.3 (39.2) | < .0001 |

| Baseline height, mean (SD), in | 64.4 (2.6) | 65.1 (2.5) | 64.9 (2.6) | < .0001 |

| Baseline body mass index, (%) | < .0001 | |||

| Underweight, <18.5 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 2.03 | |

| Normal weight, 18.5-24.9 | 32.9 | 47.0 | 43.3 | |

| Overweight, 25.0-29.9 | 30.4 | 27.6 | 28.3 | |

| Obese, ≥ 30 | 34.0 | 23.6 | 26.3 | |

| Prenatal smoker, (%) | 12.3 | 22.9 | 20.1 | < .0001 |

| Total pregnancy gain, mean (SD), lbs | 24.1 (13.9) | 30.8 (13.1) | 29.1 (13.6) | < .0001 |

| First trimester gain, mean (SD), lbs | 2.2 (4.2) | 3.7 (3.6) | 3.3 (3.9) | < .0001 |

| Minimum-Maximum | −27.6 - 16.0 | −17.1 - 25.3 | −27.6-25.3 | |

| Second trimester gain, mean (SD), lbs | 10.3 (6.4) | 13.4 (6.2) | 12.6 (6.4) | < .0001 |

| Minimum-Maximum | −7.0 - 30.5 | −8.9 - 48.1 | −8.9-48.1 | |

| Third trimester gain, mean (SD), lbs | 11.7 (7.0) | 13.6 (6.5) | 13.1 (6.7) | < .0001 |

| Minimum-Maximum | −8.0 - 38.6 | −15.1 - 42.4 | −15.1-42.4 | |

| Infant characteristics | ||||

| Infant birthweight, mean (SD), gm | 3364.1 (462.3) | 3506.4 (448.7) | 3463.5 (457.4) | < .0001 |

| Minimum-Maximum | 2126.2-5017.9 | 1927.8-5216.3 | 1927.8-5216.3 | |

| Infant gestational age, mean (SD), lbs, wk | 39.2 (1.3) | 39.1 (1.1) | 39.09 (1.16) | .008 |

| Minimum-Maximum | 37-42 | 37-42 | 37-42 | |

| Infant sex, (%) | < .0001 | |||

| Female | 37.0 | 32.2 | 33.4 | |

| Male | 41.7 | 30.4 | 33.4 | |

| Missing | 21.3 | 37.4 | 33.2 |

Abbreviations: gm, grams; in, inches; lbs, pounds; SD, standard deviation; wk, weeks; y, years.

Chi-square or t-test comparison, black and white women.

42% missing data about marital status.

The Association of Race and Total and Trimester Gestational Gain

Black women gained significantly less weight than white women in all three trimesters. After adjusting for baseline BMI, black women gained 1.0 pound less in the first trimester (P≤.0001), 1.4 pounds less in the second trimester (P ≤.0001), and 0.6 pounds less in the third trimester (P≤.01) (data not shown).

In multivariate analyses, normal weight, overweight, and obese white women gained significantly (P ≤.0001) more total GWG than black women (Table 3). Black normal weight women gained 1.4 pounds less in the first trimester and 0.9 pound less in the second trimester than white normal weight women. Black overweight women gained significantly less than white overweight women in all three trimesters. During the first and third trimester, black overweight women gained 1.0 pound less than white overweight women. The difference in black and white trimester gains was largest in the second trimester: overweight black women gained 2.2 pounds less than white women. Compared with obese white women, black obese women gained 0.7 pounds less in the first trimester and 1.5 pounds less in the second trimester.

Table 3.

Adjusted Mean Total and Trimester Gains for 2760 Black and White Women by Baseline Body Mass Index (BMI)

| Adjusteda mean (SEM) gestational weight gains (lbs) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trimester | |||||

| Baseline BMI | N | Total gestational weight gain (lbs) | First (lbs) | Second (lbs) | Third (lbs) |

| Underweight, <18.5 | |||||

| Black | 19 | 32.6 (2.7) | 4.1 (0.7) | 14.1 (1.0) | 14.0 (1.1) |

| White | 37 | 33.2 (1.8) | 4.9 (0.5) | 15.0 (0.8) | 13.2 (0.8) |

| P value | .82 | .35 | .41 | .50 | |

| Normal weight, 18.5 - 24.9 | |||||

| Black | 236 | 30.4 (0.9) | 3.2 (0.3) | 13.8 (0.4) | 14.2 (0.4) |

| White | 960 | 34.0 (0.4) | 4.6 (0.1) | 14.7 (0.2) | 14.3 (0.2) |

| P value | <.0001 | < .0001 | .03 | .91 | |

| Overweight, 25.0-29.9 | |||||

| Black | 218 | 25.7 (1.0) | 2.8 (0.3) | 11.6 (0.4) | 12.7 (0.5) |

| White | 563 | 32.2 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.2) | 13.8 (0.3) | 13.7 (0.3) |

| P value | <.0001 | .003 | <.0001 | .045 | |

| Obese, ≥ 30 | |||||

| Black | 244 | 17.9 (1.1) | 1.6 (0.3) | 7.8 (0.4) | 9.6 (0.4) |

| White | 483 | 23.1 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.2) | 9.3 (0.3) | 10.5 (0.3) |

| P value | <.0001 | .04 | .001 | .06 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; lbs, pounds; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Adjusted for baseline BMI, height, age at conception, parity, prenatal tobacco use, previous trimester(s) gain, infant sex and weeks gestational at delivery.

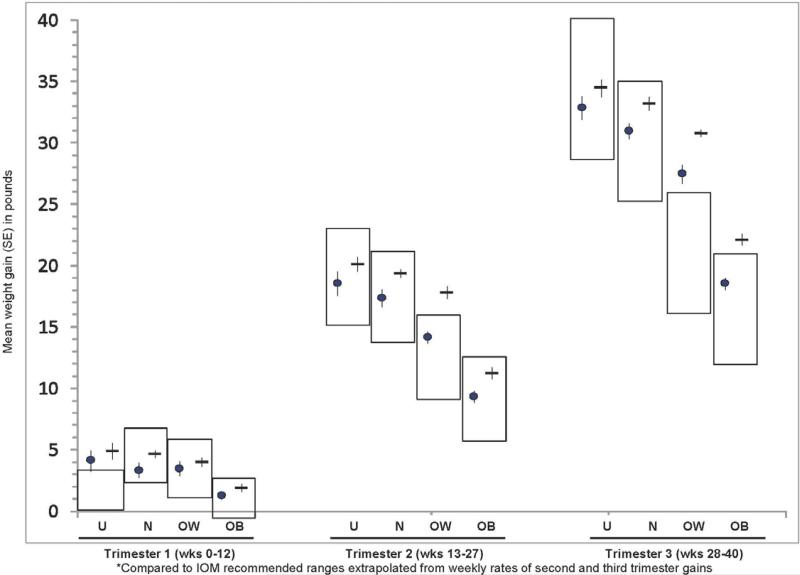

Except for underweight women, the mean first trimester gains of black and white women were within the IOM recommendations (Figure 1). Mean gains were also within the IOM recommendations for black and white underweight and normal weight women in the second and third trimesters. White overweight and obese women and black overweight women had mean second and third trimester gains that exceeded the recommended range.

FIGURE 1.

Mean pregnancy weight gain by trimester, pre-pregnancy BMI, and race*

The percentage of women with insufficient, recommended, and excessive total GWG differed significantly (P ≤.0001) by race for normal weight, overweight, and obese women (Table 4). There were no significant differences between black and white underweight women in meeting trimester-specific recommendations. Black normal weight women were nearly twice as likely as white normal weight women to gain insufficiently in the first (48% vs. 27%, respectively) and second trimesters (47% vs. 28%, respectively). By the third trimester, approximately 20% of black and white normal weight women gained within the IOM recommendations and 50 to 58% gained excessively.

Table 4.

Proportion of Women Who Met the 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Gestational Weight Gain Recommendations by Baseline Body Mass Index (BMI), Race and Trimester (n=2760)

| Baseline BMI, race, and timing of gain | Attainment of 2009 IOM Gestational Weight Gain Recommendations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient gain (%) | Recommended gain (%) | Excessive gain (%) | P value | ||

| Underweight (BMI<18.5) | |||||

| Total | Black, n=19 | 42.1 | 36.8 | 21.1 | .09 |

| White, n=37 | 21.6 | 67.6 | 10.8 | ||

| Trimester 1 | Black | 10.5 | 47.4 | 42.1 | .08 |

| White | 0 | 37.8 | 62.2 | ||

| Trimester 2 | Black | 73.7 | 10.5 | 15.8 | .20 |

| White | 54.1 | 32.4 | 13.5 | ||

| Trimester 3 | Black | 52.6 | 31.6 | 15.8 | .95 |

| White | 51.4 | 29.7 | 18.9 | ||

| Normal Weight (BMI 18.5-24.9) | |||||

| Total | Black,n=236 | 36.0 | 31.8 | 32.2 | <.0001 |

| White,n=960 | 18.6 | 41.9 | 39.4 | ||

| Trimester 1 | Black | 48.3 | 41.5 | 10.2 | <.0001 |

| White | 27.3 | 57.3 | 15.4 | ||

| Trimester 2 | Black | 46.6 | 19.5 | 33.9 | <.0001 |

| White | 27.8 | 28.7 | 43.5 | ||

| Trimester 3 | Black | 30.1 | 20.8 | 49.2 | .05 |

| White | 23.7 | 18.9 | 57.5 | ||

| Overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9) | |||||

| Total | Black,n=218 | 20.6 | 34.4 | 45.0 | <.0001 |

| White,n=563 | 6.0 | 23.5 | 70.5 | ||

| Trimester 1 | Black | 29.4 | 53.2 | 17.4 | .0001 |

| White | 16.7 | 57.4 | 25.9 | ||

| Trimester 2 | Black | 30.7 | 22.9 | 46.3 | <.0001 |

| White | 12.3 | 15.5 | 72.3 | ||

| Trimester 3 | Black | 21.6 | 13.8 | 64.7 | <.0001 |

| White | 10.1 | 10.3 | 79.6 | ||

| Obese (BMI≥30) | |||||

| Total | Black,n=244 | 30.7 | 25.0 | 44.3 | .0005 |

| White,n=483 | 18.2 | 26.5 | 55.3 | ||

| Trimester 1 | Black | 28.3 | 40.2 | 31.6 | .04 |

| White | 19.9 | 45.8 | 34.4 | ||

| Trimester 2 | Black | 41.4 | 21.3 | 37.3 | .002 |

| White | 32.5 | 16.4 | 51.1 | ||

| Trimester 3 | Black | 29.9 | 13.9 | 56.2 | .002 |

| White | 20.7 | 9.9 | 69.4 | ||

BMI = body mass index; IOM = Institute of Medicine.

The distribution of black and white overweight women meeting the IOM recommendations differed significantly in all trimesters, although most of the overweight women gained excessively in the second and third trimesters. The distribution of black and white obese women meeting the recommendations differed significantly in all trimesters. Almost half of the obese black and white women gained within the recommendation during the first trimester. In the second trimester, 41% of the obese black women gained below the recommendations and 37% gained in excess of the recommendations while about 33% of obese white women gained below and 51% gained in excess of the recommendations. In the third trimester, 56% of obese black and 69% of obese white women gained excessively.

Correlates of Gestational Weight Gain

Race was consistently and significantly associated with trimester-specific mean gestational weight gain in multivariate analyses, stratified by baseline BMI. In addition to race, these analyses yielded other significant correlates of gain for normal weight, overweight, and obese women. For normal weight women, first trimester gains among were positively associated with prenatal smoking (P =.002) and age (P=.03); second trimester gains were positively associated with parity (P <.0001) and height (P =.03); and third trimester gains were negatively associated with age (P <.0001) and positively associated with parity (P =.02) For overweight women, parity was positively associated (P =.001) with first trimester gains, but not with gains in the second or third trimesters. Age was positively associated with first trimester gains (P =.0003), but negatively associated with second (P =.02) and third (P =.0002) trimester gains. For obese women, maternal age was negatively associated with second (P =.008) and third (P <.0001) trimester gains, but was not associated with gain in the first trimester. Third trimester gain was negatively associated with prenatal smoking (P =.012). In addition, maternal height and weeks gestation at delivery each showed significant positive association with third trimester weight gain for women in all BMI categories (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is one of the first detailed analyses of the 2009 IOM recommendations for GWG by trimester, as applied to a large sample of black and white women. Similar to previous studies, we found that black women gained less weight overall than white women.10,11,13,14 Further, we found that significant differences in GWG between black and white women began in the first trimester, with white women showing greater gains. Normal weight and obese black women gained less in the second trimester, and overweight black women gained significantly less in all three trimesters. Among underweight women, black women gained less overall and in the first and second trimesters, but the differences were not significant.

Our data reflect clinical experience prior to the 2009 IOM report, but we believe it is appropriate to examine the new, stricter guidelines to this earlier time period in order to gauge potential future issues in implementation. We also appreciate that guidelines and clinical outcomes vary, confirmed when we ran the analyses using 1990 cutpoints and recommended GWG ranges6 and saw the same general pattern: about 10 to 20% of women gained within recommendations; about one-third to one-half of normal weight women gained excessively; about 50 to 75% of overweight and obese women gained excessively; and white women were more likely than black women to gain excessively.

It is not clear why white women gain more gestational weight than black women. Race is highly correlated with socioeconomic factors23,24 that could influence GWG,25 and our data did not include sensitive or relevant social indicators like persistent poverty,23 labor force transitions,23 or food insecurity25 that could have helped us better understand race differences. Provider assumptions and counseling behaviors may also contribute to differences. One study showed that African American women are more likely than white women to report having been given a GWG goal that was less than the IOM recommendation.19 It is possible that providers may deemphasize risks of excessive GWG for white women, given their overall lower risks for poor maternal and infant outcomes.

Our results suggest that practical interventions, in addition to advice, for appropriate GWG must begin early in pregnancy, or before pregnancy, and that both black and white women may benefit. Our medical record review did not allow us to capture information regarding the quality of advice about GWG or the number of women who received any GWG recommendations from their prenatal care providers. However, the participating clinics used standard prenatal forms and supplementary gestational weight gain educational materials, so we believe that our sample is representative of women who attend urban prenatal care clinics where GWG advice is available either verbally from providers or in printed materials.

Existing research points out deficits in counseling efforts, although it is not clear whether such reports reflect that women do not actually receive advice, have poor recall of advice, or are reluctance to report advice. Olson and Strawderman examined the predictors of inadequate and excessive GWG and found that only 40% of their sample reported receiving any advice about how much weight they should gain during pregnancy.17 Stotland et al. reported that overweight and obese women were particularly likely to report a GWG goal that was in excess of IOM recommendations.19

A strength of our study was the use of multiple measured weights (median=12) and measured baseline heights, in contrast to studies that may have been limited by the use of self-reported data.1,11,12 Although the qualitative difference between self-reported and measured data is debated,20-22 a review by Engstrom, et al. reported that women tend to underestimate their weight and overestimate their height, resulting in misclassification of BMI.21 We limited our sample to women who delivered term infants and in doing so restricted our analyses to generally healthy pregnancies. The exclusion of women who delivered preterm infants was appropriate because the IOM recommendations reflect assumptions about term pregnancies and our objective was to examine the total (ie, reflective of a full-term pregnancy) and trimester-specific recommendations. Thus our sample is representative of women with term pregnancies who are reasonably compliant and attended routine prenatal visits. While we found no significant difference between the sample population and those excluded women in terms of race, mean GWG, and mean baseline BMI, the included and excluded women may have had different patterns of weight gain by trimester. Finally, we had a substantial number of normal weight, overweight, and obese women for our analysis, but the small sample of underweight women (n=56) was a limitation in assessing statistically significant GWG for this group by race.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Our objective was to apply the 2009 BMI-specific trimester weight gain recommendations to a large sample of black and white women in order to provide baseline picture of the challenges providers may face in helping their patients to meet the guidelines going forward. We identified three patterns that we suspect are common in prenatal care practices: (1) Although race is increasingly recognized as a limited proxy for biological differences, our data describe a pattern where nearly half of normal-weight black women in our study population had insufficient weight gain by the second trimester, while half had excessive gain in the third trimester; (2) many overweight women had gained in excess of IOM recommendations by the second trimester and continued this pattern in the third trimester; and (3) more than half of the overweight and obese women had excessive total weight gains. While race differences exist, our data suggest that both black and white women are likely to struggle with the new IOM recommendations and it is unlikely they will easily meet them without considerable support.

A common-sense implication is that supportive and individualized GWG counsel and education should begin early in pregnancy and be continuously reinforced. However, our sample represented a group of women who had consistent and continuous prenatal care that likely involved weight gain counsel and monitoring (albeit reflecting older recommendations), as such practice was standard in our the urban clinics represented in this study. It is possible that both the timing—and the content—of weight counseling and education require modification.

About one-third of normal weight women and at least half of overweight women gained in excess of the IOM recommendations. We did not have the data to study behaviors that preceded pregnancy, such as nutrition and exercise practices, but they may inform gestational weight gain (as they may be intractable to change over the short period of pregnancy) and they certainly influence baseline weight. There is no doubt about the value of preconception health care as a standard mechanism for CNM/CM and other professionals to promote screening and interventions to optimize diet, exercise, and other health behaviors.26 We did not have the data to assess how many women in our sample received preconception counseling, but we suspect that the number is low. The professional nursing organization with the most highly developed preconception health standards is the American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM),26 but we are further uncertain about whether health practices and insurors uniformly support their commitment to providing preconception care or whether Health Care Reform will meaningfully address the generally sporadic and brief reproductive counsel currently received by non-pregnant women in the U.S.

The content of prenatal care counsel is notoriously difficult to quantify and we did not have sufficient data to attempt an exploration of weight counseling-related content. Nonetheless, we are intrigued about why white women gained more gestational weight than black women, in our study and in other studies. Is it possible that black and white providers may, directly or indirectly, present weight gain counseling differently to women based on their race? Perhaps weight gain is de-emphasized among white women, given their overall better perinatal outcomes compared with those of black women.

Finally, brief counseling about weight recommendations, and in-clinic monitoring of progress, may not be enough. We know very little about how women prioritize and value GWG, thus future work is needed to identify how GWG recommendations can be accessible and motivating to women. Women may have practical limitations to following diet and exercise recommendations or have other, more persuasive health-behavior influencers than their health care providers. Relationship-building and relevant educational materials may address such barriers. Formative studies about other prenatal and postpartum health concerns reinforce the value women place on frequent, supportive education from providers who care about their patients28 and on informational resources provided in a variety of modalities.28,29

Precis.

Excessive gestational weight gain begins by the second trimester for black and white women and is greater for white women.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by a grant from the UCare Foundation, Minnesota Medical Foundation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN and a HealthPartners Research Foundation (Bloomington, MN) Discovery Pilot grant.

Biography

Patricia L. Fontaine, MD, MS, is a Family Medicine physician and Senior Clinical Investigator at HealthPartners Research Foundation, Bloomington, MN.

Wendy L. Hellerstedt, MPH, PhD is an epidemiologist and an Associate Professor in the Division of Epidemiology & Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Caitlyn E. Dayman, MPH is a Study Coordinator at the Medical School, Dartmouth College, Lebanon, NH.

Melanie M. Wall, MS, PhD is a statistician and Professor in the Department of Biostatistics, Mailman School of Public Health and in the Division of Biostatistics and Data Coordination, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Nancy E. Sherwood, MA, PhD, is a clinical psychologist and an Associate Professor in the Division of Epidemiology & Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN and a Senior Investigator at HealthPartners Research Foundation, Bloomington, MN.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest associated with the production of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Viswanathan M, Siega-Riz AM, Moos M-K, et al. Outcomes of maternal weight gain, evidence report/technology assessment No. 168. AHRQ Publication No. 08-E009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mamun AA, Kinarivala M, O'Callaghan MJ, Williams GM, Najman JM, Callaway LK. Associations of excess weight gain during pregnancy with long-term maternal overweight and obesity: Evidence from 21 yr postpartum follow-up. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1336–1341. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu GC, Rouse DJ, Dubard M, Cliver S, Kimberlin D, Hauth JC. The effect of the increasing prevalence of maternal obesity on perinatal morbidity. Am J Obst Gynecol. 2002;185:845–849. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowell H, Miller DC. Weight gain during pregnancy: Adherence to Health Canada's guidelines. Health Reports. 2010;21:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoltand NE, Cheng YW, Hopkins LM, Caughey AB. Gestational weight gain and adverse neonatal outcome among term infants. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 Pt 1):635–643. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000228960.16678.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. Subcommittee on Nutritional Status and Weight Gain during Pregnancy. Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Subcommittee on Dietary Intake and Nutrient Supplements during Pregnancy. Nutrition during pregnancy: part I, weight gain: part II, nutrient supplements. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization [April 27, 2011];Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation. WHO technical report series, 894. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_894.pdf. 2000. [PubMed]

- 8.Institute of Medicine . Weight gain during pregnancy: Reexamining the guidelines. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siega_Rz AM, Deierlein A, Stuebe A. Implementation of the new Institute of Medicine gestational weight gain guidelines. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeVader SR, Neeley HL, Myles TD, Leet TL. Evaluation of gestational weight gain guidelines for women with normal prepregnancy body mass index. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:745–751. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000284451.37882.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickey CA, McNeal SF, Menefee L, Ivey S. Prenatal weight gain within upper and lower recommended ranges: Effect on birth weight of black and white infants. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(4 Pt 1):489–494. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen JN, O'Brien KO, Witter FR, et al. High gestational weight gain does not improve birth weight in a cohort of African American adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:183–189. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schieve LA, Cogswell ME, Scanlon KS. An empiric evaluation of the Institute of Medicine's pregnancy weight gain guidelines by race. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:878–884. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caulfield LE, Witter FR, Stoltzfus RJ. Determinants of gestational weight gain outside the recommended ranges among black and white women. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(5 pt 1):760–766. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vahratian A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of childbearing age: Results from the 2002 national survey of family growth. Matern Child Health J. 2008;13:268–273. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0340-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleveland WS, Devlin SJ. Locally weighted regression: An approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83:596–610. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson CM, Strawderman MS. Modifiable behavioral factors in a biopsychosocial model predict inadequate and excessive gestational weight gain. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:48–54. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institutes of Health [April 11, 2011];NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/women_min/guidelines_amended_10_2001.htm. Amended October 2001.

- 19.Stotland NE, Haas JS, Brawarsky P, Jackson RA, Fuentes-Afflick E, Escobar GJ. Body mass index, provider advice, and target gestational weight gain. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:633–638. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000152349.84025.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunner Huber LR. Validity of self-reported height and weight in women of reproductive age. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:137–144. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engstrom JL, Paterson SA, Doherty A, Trabulsi M, Speer KL. Accuracy of self-reported height and weight in women: An integrative review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2003;48:338–345. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(03)00281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Davey GK, Key TJ. Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC-oxford participants. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:561–565. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scharoun-Lee M, Kaufman JS, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. Obesity, race/ethnicity and life course socioeconomic status across the transition from adolescence to adulthood. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:133–139. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.075721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laria BA, Siega-Riz AM, Gundersen C. Household food insecurity is associated with self-reported pregravid weight status, gestational weight gain, and pregnancy complications. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:692–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson K, Posner SF, Biermann J, et al. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care--United States. A report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-6):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM) [May 5, 2011];Preconception health and health care: The role of the CNM/CM. http://midwife.org/siteFiles/position/Preconception_Care_5.07.pdf. May, 2007.

- 28.Yee L Simon M. Urban minority women's perceptions of and preferences for postpartum contraceptive counseling. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56:54–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2010.00012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leiferman J, Swibas T, Koiness K, Marshall JA, Dunn AL. My baby, my move: Examination of perceived barriers and motivating factors related to antenatal physical activity. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2010.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]