Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a currently incurable neurodegenerative disorder and the most common form of dementia in people over the age of 65. The predominant genetic risk factor for AD is the ε4 allele encoding apolipoprotein E (ApoE4). The secreted glycoprotein Reelin, which is a physiological ligand for the multifunctional ApoE receptors Apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (Apoer2) and very low-density lipoprotein receptor (Vldlr), enhances synaptic plasticity. We have previously shown that the presence of ApoE4 renders neurons unresponsive to Reelin by impairing the recycling of the receptors, thereby decreasing its protective effects against amyloid β (Aβ) oligomer-induced synaptic toxicity in vitro. Here, we show that when Reelin was knocked out in adult mice, these mice behaved normally without overt learning or memory deficits. However, they were strikingly sensitive to amyloid-induced synaptic suppression, and had profound memory and learning disabilities at very low amounts of amyloid deposition. Our findings highlight the physiological importance of Reelin in protecting the brain against Aβ-induced synaptic dysfunction and memory impairment.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by the buildup of plaques of amyloid-beta (Aβ) and neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau. An early-onset form of AD is caused by familial mutations in the Aβ-generating machinery and accounts for a small percentage of patients. The primary genetic risk factor for the far more common late-onset form of AD is possession of the ε4 allele encoding apolipoprotein E (ApoE4), which is present in 20% of the population, but has a prevalence of 50–80% in AD patients (1).

We have previously shown that ApoE4 disrupts synaptic function by impairing the recycling of apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (Apoer2) in the neuron (2). Apoer2, together with the very-low-density lipoprotein receptor (Vldlr), also binds the protein Reelin, a large secreted neuromodulator that regulates central nervous system (CNS) development and enhances synaptic plasticity (3, 4). Reelin clusters Apoer2 and Vldlr, leading to the activation of the cytosolic adaptor protein Disabled-1 (Dab1), which has several important consequences (3, 5). First, Dab1 activation leads to the PI3K-dependent inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), which results in the dephosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (3, 6). Second, Dab1-mediated activation of Src family kinases leads to the tyrosine phosphorylation of the NR2 subunit of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs), resulting in reduced NMDAR endocytosis and greater calcium influx when NMDARs are activated (7–10). Consequently, Reelin application to acutely isolated hippocampal slices enhances long-term potentiation (LTP) (11). On the other hand, direct application of Aβ oligomers to slices inhibits LTP, which can be prevented by co-application of Reelin (12, 13). Because ApoE4 reduces the availability of Reelin receptors at the synaptic surface by impairing receptor recycling, Reelin cannot effectively protect against the Aβ-mediated impairment of synaptic plasticity in the presence of ApoE4 (2). Consistent with this, intrathecal injection of Reelin strengthens learning and memory (14). Moreover, unphysiological overexpression of Reelin delays plaque deposition and memory impairment in a transgenic mouse model (15). However, there has been no in vivo evidence to show that activation of the Apoer2 signaling pathway by Reelin protects the brain against the pathological consequences of rising amyloid accumulation in AD.

In addition to its roles in adult synaptic function, Reelin is expressed early in development by Cajal-Retzius cells and directs the positioning of postmitotic neurons (16). Reelin knockout (reeler) mice have inverted cortical layering, disrupted hippocampal structure, and a lack of foliation in the cerebellum, which leads to a severe ataxic phenotype and early lethality (17, 18). Heterozygous reeler mice have normal neuronal migration but exhibit reduced LTP, impaired learning, and reduced sensorimotor gating (19, 20). It remains unclear if the phenotype in the heterozygous reeler mouse is due to developmental or adult effects of Reelin deficiency, for example due to subtle neuroanatomical and/or morphological changes or defects in synaptic transmission.

To address these fundamental questions, we have investigated the effect of complete Reelin loss on synaptic function and behavior in normal and in mice that moderately overproduce Aβ. To bypass the deleterious consequences of embryonic absence of Reelin for brain development, we generated an inducible conditional Reelin knockout (cKO) mouse. Following Reelin inactivation at 2 months of age, Reelin cKO mice were morphoanatomically indistinguishable from their wild-type littermate controls with a normal cortical architecture, but they did exhibit a subtle behavioral and electrophysiological phenotype. However, modest transgenic expression of human Aβ in these mice resulted in impaired spatial learning and memory. Together, our results suggest that while a healthy adult CNS can compensate for Reelin loss, Reelin signaling is vital to protect against the incipient Aβ toxicity that induces synaptic dysfunction during the early stages of aging.

Results

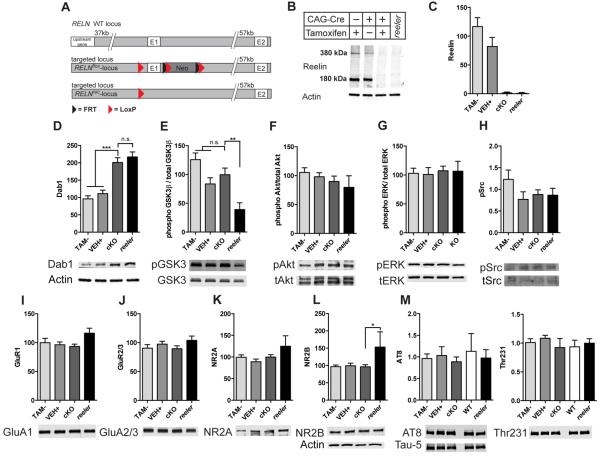

Conditional knockout mice exhibit complete loss of Reelin upon tamoxifen induction and recapitulate the reeler phenotype when induced in the germline

To determine the role of Reelin in adult synapse function and behavior, we first had to separate the adult effects of Reelin loss from its absolute requirement for brain development. Because Reelin-deficient (reeler) mice have a severe developmental phenotype that effectively compromises all studies of Reelin loss in the adult brain (18), we generated a conditional Reelin knockout mouse line. Relnflox/flox mice were derived using a construct in which first exon of the Reln gene was flanked with loxP sites (Materials and Methods and Fig. 1A), bred to homozygosity, and crossed with an inducible Cre recombinase expressing line, from here on referred to as the CAG-CreERT2 line (21). This mouse line ubiquitously expresses a fusion protein comprised of Cre recombinase and a mutated form of the estrogen receptor (Cre-ERT2), and tamoxifen administration induces nuclear Cre activity and knockout of the floxed gene. Western blotting showed that Reelin amounts in the hippocampi of tamoxifen-injected Relnflox/flox mice were reduced to less than 5% of that in vehicle-injected mice and that Reelin was undetectable in most mice (Fig. 1B,C). The brain-wide loss of Reelin was confirmed through immunohistochemistry, which revealed a total loss of Reelin throughout the brain (Fig. S1). Reelin-induced phosphorylation of Dab1 targets this protein for proteasomal degradation, and thus loss of Reelin signaling results in higher Dab1 protein abundance (22, 23). Immunoblotting showed that the Reelin cKO mice exhibited increased Dab1 protein abundance, similar to reeler mice and confirming complete loss of Reelin function (Fig. 1D). Moreover, this observation also confirms that the Reelin signaling pathway is physiologically active in the adult brain, because Dab1 turnover depends on pathway activation.

Fig 1.

A) Relnflox/flox mice were generated by flanking Exon 1 of the Reln gene with LoxP sites. The mice were bred to homozygosity and crossed with CAG-CreERT2 line, which expresses a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase ubiquitously. B) Western blot of whole hippocampal lysates with G10 antibody, demonstrating inducible Reelin knockout. The positions of the180 and 380 kDa Reelin forms are indicated. TAM−: Tamoxifen-injected Relnflox/flox mouse; VEH+: vehicle-injected CAG-CreERT2:Relnflox/flox mouse; cKO: Tamoxifen-injected CAG-CreERT2:Relnflox/flox mouse; reeler. C) Quantification of 180 kDa Reelin band Western blotting. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. (VEH−, TAM−, VEH+ n=10 mice, cKO n=11 mice, reeler n=4 mice). D–M) Whole hippocampal lysates from mice of the indicated genotypes were evaluated by Western blot. Total Dab1 abundance normalized to actin (same samples as in B) (D) (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.0001, post-hoc TAM− compared to cKO p < 0.001, VEH+ compared to cKO p < 0.001) (TAM− n=11 mice, VEH+ n=12 mice, cKO n=12 mice, reeler n=7 mice), phosphorylated (p) GSK3β (Ser9) normalized to total GSK3β (E) (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.0012, post-hoc cKO compared to KO p < 0.001), phosphorylated Akt normalized to total Akt (F), phosphorylated ERK normalized to total ERK (G), phosphorylated Src normalized to total Src (H), GluA1 (I) and GluA2/3 (J), NR2A (K) (one-way ANOVA, ppAkt/tAkt = 0.5329, ppERK/tERK = 0.9946, ppSrc = 0.2660, pGluR1 =0.1458, pGluR2/3 = 0.3996, pNR2A = 0.1168), and NR2B (L) are shown (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.0593, post-hoc cKO compared to reeler p < 0.05) For (E)–(G) and (I)–(L), TAM− n=8 mice, VEH+ n=11 mice, cKO n=11 mice, reeler n=5 mice). For (H), TAM− n=6 mice, VEH+ n=6 mice, cKO n=6 mice, reeler n=5 mice. Phosphorylated tau normalized to total tau (M) (one-way ANOVA pAT8 = 0.9610, pThr231 = 0.7995, n=4 mice per genotype) is also shown. All samples in (D)–(L) were normalized to actin or RAP then to the control (TAM− and VEH+) mice. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

To confirm that the Relnflox/flox line can fully recapitulate the reeler phenotype, Relnflox/flox mice were crossed with the Meox-Cre line, which induces recombination in epiblast-derived tissues and thus also in the germline (24). These mice showed the typical reeler phenotype with inverted cortical layering and a lack of cerebellar foliation (Fig. S2). Together, these data demonstrate that Cre-recombinase readily and rapidly inactivates the gene in Relnflox/flox mice and thus these mice constitute an effective conditional knockout model in which the consequences of adult Reelin loss can be investigated.

Adult loss of Reelin affects the abundance of Dab1, but not that of downstream effectors or glutamate receptor

To determine the extent of the disruption of the Reelin signaling pathway in Reelin cKO mice, we next assessed the activity of downstream effectors of Dab1 signaling. We found that although reeler mice exhibited reduced phosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9 (an inhibitory phosphorylation site)(6), our Reelin cKO mice showed no change relative to controls (Fig. 1E) suggesting that the increased GSK3β activity in the reeler mouse brain (who lack Reelin during development) is caused and maintained by the persistent disruption of the brain architecture. We similarly observed no changes in the phosphorylation of Akt, ERK, or Src (Fig. 1F,G, H), two other downstream effectors of Reelin signaling, including in the germline reeler mice that survive to two months of age (25, 26). We then determined the whole cell abundance of glutamate receptors, since these are altered in heterozygous reeler mice (27). GluA1 and GluA2/3 abundance were unaltered in all mice (Fig. 1I,J). NR2A abundance was similar in all mice (Fig. 1K). NR2B abundance was increased in reeler mice, but not in the cKO mice (Fig. 1L).

Tau is hyperphosphorylated in reeler mice, which likely contributes to neuronal dysfunction in these mice (3). We examined the phosphorylation of tau at two sites in the cKO mice, the AT8 epitope and at Thr231. Neither were altered in the either the cKO or the reeler mice (Fig. 1M). We further showed previously that strain background-dependent tau phosphorylation correlates with early postnatal death in these lines, which readily explains the absence of tau phosphorylation in adult reeler mice (28). Together, these biochemical results indicate that while we successfully disrupted Reelin signaling in the cKO mice, other adaptive responses may be able to compensate to some extent for Reelin loss in young, healthy mice.

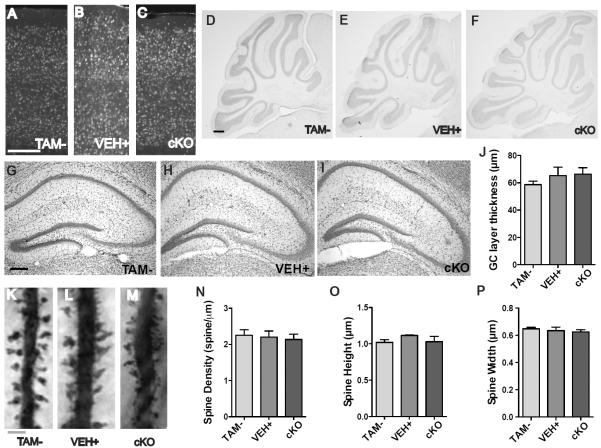

Adult Reelin cKO mice have normal CNS architecture

Reelin is required for the development of layered brain structures, particularly for cortical lamination and the formation of the cerebellum. Moreover, disruptions of the Reelin signaling pathway have been shown to cause granule cell dispersion (29). To confirm that we were successful in bypassing the severe developmental effects of Reelin gene disruption, we evaluated sections from Reelin cKO mice for altered cytoarchitecture. reeler mice have disorganized cortical layering; by contrast, the cKO mice exhibited normal cortical layering, as judged by NeuN labeling, one month after tamoxifen injection (Fig. 2A–C). Similarly, while reeler mice have a loss of foliation in the cerebellum, cKO mice cerebella appeared grossly normal (Fig. 2D–F), as did the hippocampi (Fig. 2G–I). These data suggest that Reelin is not required for the maintenance of CNS layering in the adult.

Fig 2.

Adult Reelin cKO mice have normal architecture, no granule cell dispersion, and no alterations in dendritic spine density. (A to P) Sections were compared from TAM− (A,D,G,K), VEH+ (B,E,H,L), and cKO (C,F,I,M) mice. Cortical sections were evaluated for disrupted layering by NeuN immunohistochemistry (A,B,C). Scale bar, 200 μm. Cerebellar (D,E,F) (scale bar, 200 μm) and hippocampal (G,H,I) (scale bar, 200 μm) sections were stained with cresyl violet. The granule cell layer thickness was measured to assess granule cell dispersion (J) (one-way ANOVA p = 0.5016). For A–F, n=3 sections per mice, 3 mice per genotype. For G–J, n=6 sections per mice, 3 mice per genotype. Golgi-stained CA1 apical dendrites (K,L,M) were analyzed for changes in spine density (N) and spine morphology (O,P) (scale bar = 5 μm) (one-way ANOVA, pDensity = 0.8681, pHeight = 0.4822, pWidth = 0.7753) (TAM− n = 38, VEH+ n = 29, cKO n = 25, where n represents total neurons analyzed from 3 mice per genotype). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

After normal development, interference with Reelin signaling through application of the CR-50 antibody causes granule cell dispersion (30), yet we found no evidence of granule cell dispersion in the Reelin cKO mice one month after tamoxifen injection (Fig. 2J). This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that CR-50 blocks the oligomerization of Reelin, which interferes with signaling through the canonical Reelin pathway, but may not prevent the binding of Reelin to other receptors, such as members of the Eph/Ephrin family or integrins, thereby potentially causing dominant negative interference (31–33). Moreover, injection of the functionally neutralizing CR-50 into the dentate gyrus may effectively establish a Reelin signaling gradient, leading to the dispersion; in our model, Reelin is homogenously knocked out, thus preventing the development of such a gradient.

Finally, because primary cultures of reeler neurons have reduced spine density and Reelin supplementation increases dendritic spine density (14, 34), we measured dendritic spine density in the cKO mice. Brains were stained using the Golgi method, and the spine density of apical CA1 dendrites was measured. We found no differences between cKO and control dendritic spine density (Fig. 2K–N). Moreover, while heterozygous reeler mice have altered spine morphology (35), we observed no difference in cKO mice (Fig. 2 O,P). Together, these data indicate that interruption of Reelin signaling in the adult and fully formed brain results in no obvious structural changes.

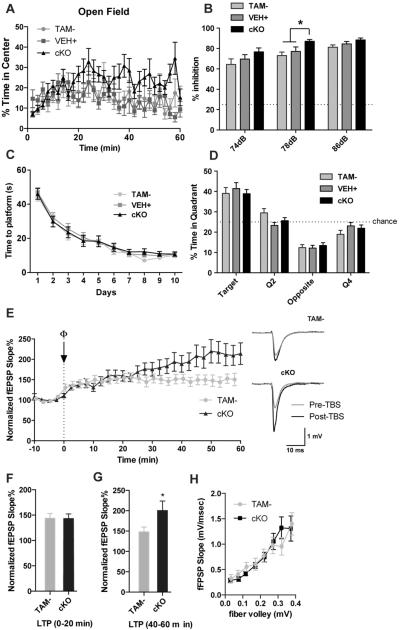

Reelin cKO mice have a mild behavioral phenotype

Because we found that adult loss of Reelin has no effect on brain structure, we sought to explore the behavioral phenotypes of the Reelin cKO mice. Reeler mice have a stereotypical ataxia, which precludes equal comparison with wild-type mice on most behavioral tasks. Moreover, heterozygous reeler mice have an age-dependent reduction in ability to perform the rotarod task (36). To determine if adult loss of Reelin affects motor skills, we tested motor learning and coordination in 3-month-old Reelin cKO mice on the rotarod. We found no difference in the performance of cKO mice compared to their littermate controls over the course of 10 days of training (Fig. S3A).

Next, we evaluated the Reelin cKO mice for changes in anxiety, because heterozygous reeler mice have reduced anxiety (37). First, mice were tested on the open-field task, in which they were put into an open field box and the time spent in the center versus the periphery was measured. Reelin cKO mice spent slightly more time than controls towards the end of the hour in the center of the field compared to the periphery, which may suggest reduced anxiety (Fig. 3A). To further evaluate this potential reduced anxiety phenotype, we tested the mice on the elevated plus maze task. In this task, mice were placed on an elevated central platform and allowed to explore the four arms extending from it: two “closed” arms with high walls and two “open” arms with no walls. More time spent in the closed arm is considered to reflect increased anxiety. We found that all genotypes spent similar amounts of time in the closed arm (Fig. S3B). Together, these two measures of anxiety suggest that Reelin cKO mice have low hypo-anxiety that emerges with time.

Fig 3.

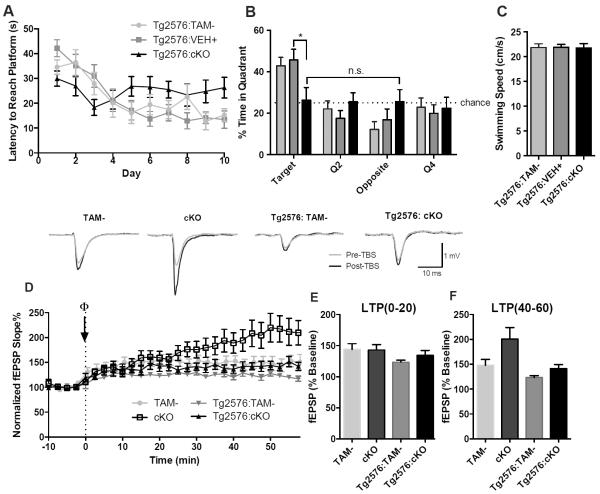

Reelin cKO mice have mild behavioral changes and increased LTP. A–D) Reelin cKO mice have hypo-anxiety and mildly enhanced PPI, but no changes in learning. A) The percent time mice spent in the center of an open-field apparatus for each 2-minute bin is shown. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA shows a strong effect of time (p < 0.001), a non-significant trend of genotype (p = 0.0783), and a significant interaction between the two (p = 0.0129) (TAM− n=11 mice, VEH+ n=10 mice, cKO n=14 mice). B) Mice were tested for pre-pulse inhibition with the indicated tones preceding a 120 dB tone. Data shown is reduction of startle at each pre-pulse relative to the startle when no pre-pulse was played prior to the 120 dB tone (two-way ANOVA, pInteraction = 0.876, pPre-pulse Intensity < 0.0001, pGenotype = 0.0008; post-hoc at 78 dB - TAM− compared to cKO: p = 0.0013, VEH+ compared to cKO: p = 0.0306) (TAM− n=16 mice, VEH+ n=18 mice, cKO n=17 mice). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. C, D.) Morris water maze results from cKO mice. The latency of mice to find a hidden platform over a 10 day training period was measured (C) (two-way repeated measures ANOVA, p Interaction = 0.9993, p Time < 0.0001, p Genotype = 0.5616, n=10 per group). On the 11th day, the platform was removed, and the time spent in the quadrant that had previously contained the platform was measured (D) (two-way ANOVA, p Genotype > 0.999, pQuadrant < 0.0001, pInteraction = 0.1874) (TAM− n=16 mice, VEH+ n=17 mice, cKO n=17 mice). E–H) Reelin cKO mice have enhanced late LTP. E) Field recordings were made from the stratum radiatum of the CA1 region of hippocampal slices from 7-month-old Reelin cKO mice before and after application of theta-burst (TBS) LTP. Every 2 minutes were averaged for analysis. Sample traces are shown pre- and post-TBS (right). F, G) The average LTP at 0-20 minutes was similar between control and CKO mice (F) (unpaired t-test p = 0.9511). At 40-60 minutes cKO mice had increased LTP (G) (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0483). H) The input-output curves were unaltered between cKO and control mice (unpaired t-test p = 0.9828) (TAM− n = 15 slices from 6 mice, cKO n = 11 slices from 4 mice). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

In addition to anxiety and motor deficits, heterozygous reeler mice have reduced pre-pulse inhibition (PPI), which is an indication of disrupted sensorimotor gating (20). We tested PPI in the cKO mice, which had normal startle amplitudes in response to tones ranging from 70–120 dB (Fig. S3C), at three pre-pulse tones: 74 dB, 78 dB, and 86 dB. Surprisingly, Reelin cKO mice showed no alterations in PPI at 74 dB and 86 dB, with a significant, though only slight, increase in PPI at 78 dB (Fig. 3B). Together, these mild phenotypes suggest that the anxiety and sensorimotor deficits found in heterozygous reeler mice are caused by the loss of developmental functions of Reelin, and further validate the importance of the cKO model for understanding the roles of Reelin in the adult and aging brain.

Reelin cKO mice have no deficits in learning and memory

Given the mild phenotype on anxiety and sensorimotor tests in these mice, we wondered about the effect of Reelin loss on learning and memory. Reelin modulates learning and memory: notably, heterozygous reeler mice are impaired on some memory tasks, and intra-ventricular injection of Reelin enhances Morris water maze performance (14, 15, 19). To investigate the role of Reelin in adult memory acquisition, we subjected 3-month-old cKO mice to the Morris water maze and Fear Conditioning tasks. First, in the Morris water maze, mice were trained to find a platform hidden in cloudy water over the course of 10 days, followed by a 60 second probe trial on day 11, in which the platform was removed. Reelin cKO mice showed no differences in acquisition of the platform location (Fig. 3C) and a similar preference for the target quadrant during the probe trial (Fig. 3D). Next, mice were tested for alterations in fear learning with contextual and cued fear conditioning. Similar to the Morris water maze results, cKO mice showed normal acquisition and memory in both contextual (Fig. S3D) and cued fear conditioning (Fig. S3E).

Reelin cKO mice have enhanced LTP

Given that the Reelin cKO mice are virtually indistinguishable from wild type littermates by biochemical and behavioral assessments, we wanted to determine if there were any differences in neuronal function, specifically synaptic plasticity. Because Reelin application enhances theta-burst LTP, and heterozygous reeler mice have reduced LTP, we hypothesized that LTP in Reelin cKO mice would be reduced. To investigate the electrophysiological effects of Reelin loss, we performed theta-burst LTP experiments on acutely isolated hippocampal slices from 7-month-old cKO mice. Briefly, we recorded field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) from CA1 dendrites after stimulating afferent CA3 axons (Schaeffer collaterals) and compared the fEPSP slope before and after theta-burst stimulation (TBS) (Fig. 3E). Although initial LTP (0–20 minutes) was the same between control and cKO mice (Fig. 3F), the late component of LTP (between 40–60 minutes) in cKO mice was increased nearly 50% percent compared to control mice (Fig. 3G). Input-output curves were similar between the two genotypes, suggesting that the LTP change was not caused by differences in baseline synaptic transmission (Fig. 3H). These electrophysiological results suggest that, although Reelin cKO mice appear normal according to standard behavioral tests, the electrophysiology of their hippocampi is altered.

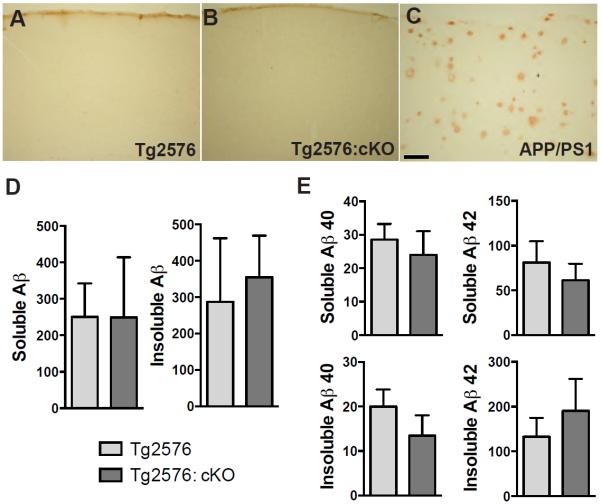

Reelin loss does not accelerate plaque deposition or increase Aβ amounts in Tg2576 mice

The changes of synaptic plasticity in the Reelin cKO mice raised the possibility that these mice might be more sensitive to toxicity induced by Aβ oligomers. We have previously shown that Reelin directly protects against Aβ toxicity at the synapse in acutely isolated hippocampal slices (12). Despite the mild behavioral and synaptic alterations in the Reelin cKO mice, we suspected that adult loss of Reelin might exacerbate this Aβ toxicity. To investigate the in vivo consequences of Reelin loss on Aβ toxicity, we crossed the Reelin cKO line with the Tg2576 (APPSwe) AD model mouse line, which overexpresses a mutant form of APP bearing the Swedish mutation (KM670/671NL), resulting in increased Aβ amounts starting around 4 months of age (38).

Aβ concentration may correlate with cognitive decline (39), and Reelin haploinsufficiency increases Aβ abundance and accelerates plaque development in one particular strain of mutant APP transgenic mice (40). We therefore investigated whether adult Reelin deficiency accelerated plaque development in mice injected with tamoxifen or vehicle at 2 months of age and aged for 5 months. To quantify amyloid plaque formation, we performed immunohistochemistry for Aβ using the 4G8 antibody (41) in 7-month-old mice and found a lack of plaques in the cortex in these mice (Fig. 4A,B). As a positive control for our immunostaining, we also stained brain sections from a 9-month-old APP/PS1 transgenic mouse, which showed readily detectable plaque deposition (Fig. 4C). We next quantified the PBS-soluble (monomers) and –insoluble (fibrillar) Aβ in the brains of Tg2576: Reelin cKO and Tg2576 control (TAM−) mice by Western blot. Aβ abundance was low but detectable in the Tg2576 mice, but varied widely among all the genotypes, and we found no significant difference between the Tg2576: Reelin cKO and Tg2576 mice in either the soluble or insoluble fractions (Fig. 4D). Quantification of the species of Aβ present by ELISA also revealed no difference in the amount of of PBS-soluble or –insoluble Aβ40 or Aβ42 (Fig. 4E).

Fig 4.

Loss of Reelin does not accelerate amyloid pathology in 7-month-old Tg2576 mice. A, B) Immunohistochemistry with 4G8 antibody was performed on brains of (A) Tg2576 and (B) Tg2576: cKO mice to evaluate plaque deposition (n=3 mice/genotype). Scale bar = 200 μm. C) 9-month-old APP/PS1 mice were used as a positive control because they had no obvious plaques. D) The abundance of PBS-soluble and -insoluble Aβ was measured with Western blot and quantified. No difference was observed between cKO and control mice (unpaired t-test psoluble = 0.9945, pinsoluble = 0.7554) (n=6 mice/genotype). E) The abundance of PBS-soluble and – insoluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 were measured by ELISA. No difference was observed between cKO and control mice (unpaired t-test Aβ40 psoluble = 0.6016, pinsoluble = 0.3398, Aβ42 psoluble = 0.6116, pinsoluble = 0.4789) (n=9 Tg2576 mice, n = 4 Tg2576:cKO mice). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Reelin loss accelerates cognitive impairment in Tg2576 mice

Next, we explored if Reelin loss left mice susceptible to amyloid toxicity. 7-month-old cKO mice were tested in the Morris water maze. At this age, Tg2576 mice accumulate minute amounts (less than 10 pmol/g) of Aβ, and cognitive deficits in the Morris water maze are typically not detectable until Aβ concentrations are over a hundred fold higher (42). Morris water maze testing revealed that Tg2576 mice demonstrated normal learning and memory at this age as expected, whereas Tg2576: Reelin cKO mice showed severely impaired acquisition and performance on the probe trial equivalent to chance (Fig. 5A,B). There was no difference in swim speed (Fig. 5C), indicating that the impairment was caused by a hippocampal-dependent learning and memory deficit and not a sensorimotor defect. To confirm that the impairment was not due to an age-dependent effect of Reelin loss, we tested naïve 7-month-old Reelin cKO mice in the Morris water maze and found that they performed as well as wild-type (Fig. S4). These data thus provide direct evidence that Reelin protects against memory impairment caused by Aβ toxicity.

Fig 5.

Low amounts of endogenously produced Aβ induce severe memory impairment and reduce hyperexcitability in Tg2576: Reelin cKO mice. A, B, C) Morris water maze testing of 7 month old Tg2576: Reelin cKO mice showed that they had impaired acquisition of the task (A) (two-way ANOVA: F(18,306)Interaction = 3.370, p <0.0001, F(9,306)Time = 10.38, p < 0.0001, F(2,34)Genotype = 0.564, p = 0.5742) and poor performance on the probe trial (B). Swim speeds (C) between genotypes were similar (one-way ANOVA p = 0.9866). (Tg2576:TAM− n=9 mice, Tg2576: VEH+ n= 12 mice, Tg2576: cKO n= 16 mice). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. D,E,F) Theta-burst LTP was performed in the Tg2576: Reelin cKO mice (D). No difference was observed at the 0-20 minute time point (E). However, at 40-60 minutes the cKO mice had increased LTP, whereas the Tg2576:cKO mice showed similar LTP to control mice (F). One-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference at 40-60 minutes, with post-hoc analyses indicating a significant difference between the cKO mice and all other genotypes (p < 0.05 compared to TAM−, p < 0.01 compared to Tg2576, p < 0.05 compared to Tg2576:cKO), but no difference between the other genotypes, including the Tg2576:Reelin cKO. (TAM− n = 15 slices from 6 mice, cKO n = 11 slices from 4 mice, Tg2576: TAM− n= 11 slices from 4 mice, Tg2576: cKO n = 10 slices from 4 mice). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Tg2576:Reelin cKO mice do not have increased LTP

To determine how the presence of Aβ affected the increased late component of LTP in cKO slices, we assessed hippocampal synaptic plasticity in Tg2576:Reelin cKO mice and Tg2576 control brains. Because all four genotypes were recorded in parallel, the cKO and TAM-measurements are recast from Figure 3. Quantification of TBS-induced LTP indicated that the increased late component of LTP in Reelin cKO slices was abolished in Tg2576:Reelin cKO slices (Fig. 5D–F). These results show that Aβ affects synaptic responses in Reelin cKO mice to a greater extent than in control mice, which mirrors the cognitive impairment elicited by low amounts of Aβ in these mice.

Discussion

We investigated the physiological importance of Reelin for behavior, synaptic function, and protection against Aβ toxicity in the adult brain. Using a conditional Reelin knockout mouse model, we found that the isolated loss of Reelin had only subtle effects on neuronal physiology and function of an adult mouse. However, loss of Reelin rendered excitatory synapses susceptible to functional suppression by Aβ, which resulted in impaired learning and memory in a commonly used AD mouse model. Taken together, our findings provide in vivo evidence that highlights the key role of Reelin signaling for the protection against Aβ toxicity in the adult brain.

Since the identification of the reeler mouse phenotype (18) with its severe ataxic phenotype, disrupted layering in several brain regions, and early lethality, and the discovery of the Reelin gene (17), researchers have studied the role of Reelin in brain development, synaptic function, and neuronal disease. Several studies have pointed to a prominent role for Reelin in adult synaptic function. First, application of Reelin to acute hippocampal slices enhances theta-burst LTP (11). Likewise, intra-ventricular injection of Reelin into wild-type mice enhances learning and memory (14). Conversely, heterozygous reeler mice have reduced amounts of Reelin and deficits in both LTP and learning and memory (19).

Given the behavioral deficits observed in heterozygous reeler mice, we tested the Reelin cKO mice on a battery of behavioral measures and were surprised to find that the mice were indistinguishable from their wild-type littermate controls by most parameters, except for slow-onset hypoanxiety and minor enhancement in pre-pulse inhibition. These findings suggest that most phenotypes described in heterozygous or homozygous reeler mice are caused by developmental changes of the brain, and not by acute loss of Reelin signaling in the adult brain. They also stress the importance of using a conditional knockout model to study the consequences of loss of Reelin function in the adult brain. Our findings contrast those found in mice with a postdevelopmental loss of Dab1, which is the primary cytosolic adaptor protein for Reelin. Dab1 cKO mice have a marked deficit in spatial learning (25). Though these behavioral differences could be explained by different mouse backgrounds, there are other possible explanations. Although they are generally viewed as primary signaling partners, Reelin and Dab1 have various other binding partners, resulting in divergent extracellular as well as intracellular branches of several distinct signaling pathways in which Reelin and Dab1 participate and which can readily explain why loss of Reelin does not recapitulate the learning phenotype of the Dab1 cKO mice. For example, Reelin also binds to integrins, APP, and EphB receptors (31, 33, 43) and there are other ligands for the Reelin receptors, such as ApoE, ApoJ (Clusterin) and F-Spondin (44–46). Moreover, Dab1 binds to several NPXY motif-containing receptors, including APP, integrins and LRPs (47–49). Thus, Dab1 loss may also suppress synaptic plasticity through these partners (48, 50). Intriguingly ApoJ (also known as Clusterin) is also a late-onset AD risk gene (51). Thus, the products of several AD risk genes - ApoE, ApoJ and APP - converge upon their common binding partner Apoer2 at the synapse. This convergence further emphasizes the importance of Reelin signaling through ApoE receptors and underscores the pivotal role of this ligand-receptor complex in protecting the synapse from Aβ-mediated suppression.

The reeler mouse shows defective neuronal migration, and disruption of Reelin signaling with CR-50, an anti-Reelin antibody, leads to granule cell dispersion (30). This dispersion is observed in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE), the most common form of epilepsy (52). Intra-hippocampal kainic acid injection causes granule cell dispersion in mice (53), which is associated with reduced Reelin abundance in the hippocampus (30). Supplementation with Reelin can prevent granule cell dispersion following kainic acid injection (54). We found that complete loss of Reelin in adult mice resulted in no dispersion of the granule cell layer, suggesting that additional signaling cascades are activated in response to enhanced glutamate release in MTLE and experimental kainate application, respectively, eventually leading to increased granule cell motility and dispersion (55).

Despite relatively normal behavioral and histological findings, Reelin cKO mice showed electrophysiological changes, including enhancement in the late component of LTP, in contrast to the reduced theta-burst LTP found in heterozygous reeler mice (19). The LTP phenotype in the Reelin cKO mice is similar to that observed in ApoE4 knock-in mice, which also show enhanced LTP (56) and Reelin resistance, i.e. a state of impaired response to endogenous or exogenously provided Reelin analogous to the impaired cellular response to insulin in type 2 diabetes, by electrophysiological assessment (2). Several synaptic modifications can cause enhanced LTP. One is a change in baseline synaptic transmission, but is unlikely to be the underlying cause because the input-output curves were similar in cKO and control mice. Another possible mechanism for enhanced LTP is reduced inhibition (57). Because Reelin is found primarily in inhibitory interneurons in adults, future studies will also need to focus on the effect of Reelin loss on inhibitory function. Alternatively, alterations in glutamate receptor trafficking can change excitability, and Reelin regulates both glutamate receptor trafficking and thereby promotes their function, as well as synapse maturation (34, 58–60). Finally, Reelin activation of Apoer2 initiates a transcriptional program through CREB that underlies learning and memory (8, 61, 62). Loss of this transcriptional program may be a cause for the synaptic and electrophysiological alterations we observed(4).

Dysfunctional Reelin signaling in human disease has been implicated in schizophrenia, where approximately 50% reduction of Reelin has been reported, due to hypermethylation of the promoter region (8, 63). Heterozygous reeler mice and human schizophrenic patients display reduced pre-pulse inhibition, a defect not present in the cKO mice. In fact, these animals showed a small increase in pre-pulse inhibition, which points to a developmental origin for the schizophrenia caused by Reelin deficiency.

Impairment of Reelin signaling has been implicated in the cognitive impairment that manifests itself in AD. Patients with AD have alterations in Reelin abundance and glycosylation (64), and disease-associated SNPs have been identified in the RELN locus in female AD patients (65). Additionally, a Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) found an association between SNPs in RELN and a high Braak score (high plaque and tangle load) in cognitively normal individuals. Individuals with high Braak scores and normal cognition also have increased Reelin abundance (66). This correlation of increased Reelin abundance with increased AD pathology and lack of cognitive deficits could be an indirect effect of the RELN SNPs promoting AD pathology. However, based on our finding that loss of Reelin accelerates cognitive decline in Tg2576 mice independent of AD pathology, we suggest that these RELN SNPs render neurons resistant to Aβ-accumulation by increasing the bioavailability of Reelin.

ApoE4 is the primary genetic risk factor for AD (1). We have previously identified a direct synaptic role for ApoE4 in impairing the active recycling of the ApoE receptors Apoer2 and Vldlr, which also bind Reelin, to and from the synaptic surface through an unknown mechanism, which leaves neurons unable to effectively respond to Reelin signaling (2). Because ApoE4 also promotes AD pathogenesis through other mechanisms (for example, increasing inflammatory processes, increasing tau phosphorylation, and reducing clearance of Aβ (67)), we sought to isolate the effects of Reelin loss on the background of increasing Aβ accumulation, which occurs in the early stages of AD. To do this, we crossed our Reelin cKO mice with the Tg2576 AD mouse model line, which has a relatively slow rate of Aβ accumulation that starts around 4 months and cognitive decline not occurring until old age (42). We studied these mice at 7 months of age, at a time when Aβ oligomers have started to appear, but no amyloid deposition or cognitive decline has occurred (68).

Previous studies of Reelin in mouse models of AD have shown that Reelin affects Aβ abundance and amyloid deposition (15, 40). Aβ overproducing mice that are haploinsufficient for Reelin deposit amyloid plaques more rapidly and uncharacteristically develop neurofibrillary tangles at 15 months of age (40). Typically, Aβ overproducing mice that are not transgenic for human tau do not develop tangles. In addition, unphysiological and ectopic overexpression of Reelin in APP/PS1 transgenic mice slows plaque deposition and rescues memory impairment on the novel object recognition task (15). We have shown that the loss of adult Reelin in the context of minimal Aβ overproduction did not accelerate plaque development, despite severe impairments in memory formation. Our findings contrast with those of Pujadas et al., who were using an artificial overexpression system and animals expressing Reelin in the wrong cell type, which precludes conclusions as to the physiological functions of Reelin. As predicted by our earlier studies (12), the overexpression of Reelin can strengthen the intrinsic synaptic defense mechanisms against Aβ-mediated suppression; however, simple overexpression of Reelin in vivo does not allow us to deduce whether Reelin is indeed important for controlling synapse function in the presence of physiological amounts of Aβ. Moreover, using a conditional Reelin knockout in a mouse model that produces low amounts of human Aβ, we have established an animal model that allows us to gauge the importance of this evolutionarily ancient signaling pathway in protecting against a prevalent neurodegenerative diseases of humans. While our findings do not exclude an effect of Reelin loss on amyloid abundance at later stages of disease progression, they do suggest that it is indeed impaired Reelin signaling, through resistance to Reelin signaling induced by ApoE4, by which ApoE4 sensitizes the synapse to damage by Aβ (2).

Alzheimer's disease is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. Thus far, Aβ-directed therapeutics have proven unsuccessful in treating patients, suggesting that a novel therapeutic approach is called for. We have shown that reduction of Reelin signaling in the adult brain, as occurs in aging and the presence of ApoE4, leaves neurons susceptible to toxic damage caused by Aβ. Our results suggest that protecting and promoting Reelin signaling could be an effective method to prevent AD. This opens a new avenue to the identification of new types of therapeutics that can enhance Reelin abundance or restore normal lipoprotein receptor-mediated signaling in ApoE4 carriers.

Materials and Methods

Animals

B6.Cg-Tg(CAG-cre/Esr1)5Amc/J mice, which we referred to as CAG-CreERT2 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (21). The B6.129S4-Meox2tm1(cre)Sor/J mice, which we referred to as Meox-Cre, were kindly provided by Michelle Tallquist (24). Tg2576 mice were obtained from Taconic (38). Animals were group-housed in a standard 12-h light cycle and fed ad libitum standard mouse chow. All animal care protocols were followed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and the University of Freiburg.

In light of the complexity of the genetic crosses and the different origin of the animal strains involved in this study, it has not been possible to conduct all experiments on a strictly homogenous C57BL/6 strain background. To ensure a minimal effect of strain background on the behavioral results we have found, all animals that were compared were brother/sister crosses that only differ by the absence or presence of Cre recombinase. Moreover, discovering a robust response like the one discussed here in a mixed background, as opposed to an inbred one, further strengthens the validity of the conclusions, rather than diminishing them. Most importantly perhaps, it further supports the applicability of the results to the even more genetically heterogeneous human population.

Generation of the Reln flox mouse

To create the targeting vector for the conditional Reelin knockout mouse line, pJB1 (described in (69)) was used as background vector and murine SV129J ES cell DNA as template DNA to amplify the short homology arm (SA, 1.35 kb), the fragment containing the first exon (EX1, 1.25 kb), and the long homology arm (LA, 9 kb). To incorporate the first loxP site a ClaI and a PvuI restriction site were included in the SA reverse and the EX1 forward primer, respectively. By three-fragment ligation, the (1) SA (cut with SalI and ClaI) and (2) EX1 (cut with SalI and PvuI) fragments were combined by a (3) LoxP coding linker (two annealed oligos with sticky ends for ClaI and PvuI) and cloned between the Neo and HSVTK selection marker genes (XhoI site, compatible ends with SalI) of pJB1. The resulting vector was opened with NotI to insert the 9 kb LA fragment 3'-downstream of the loxP/FRT flanked Neo-cassette. The primers used were: SA_for, 5'- ATCGATGTCGACGGAAGTTTTGCTTCTTCCGGTG-3' (SalI); SA_rev, 5'-CAATCGATGTTGTTTGTCTACGCCGGCTGCAAC-3' (ClaI); EX1_for, 5'-CCTTCTCGCGATCGCGCGTCCTCGCAGAACGGGCAGCC-3' (PvuI); EX1_rev, 5'-GCGGCCGCGTCGACTGGGCAGCCACCGACCAAAGTGCTC -3' (SalI); LA_for, 5'-TGTTGCGGCCGCGGCGGCCAGTTAAAAGTTCCCGCTG-3' (NotI); LA_rev, 5'-GTCGACGCGGCCGCTTCCATAAAAGGGAAGAGCAAGATG-3' (NotI). The oligos used were: LoxP_for, 5'-CGATAACTTCGTATAGCATACATTATACGAAGTTATAT-3'; LoxP_rev, 5'-CGATATAACTTCGTATAATGTATGCTATACGAAGTTATCGAT-3'. The final construct containing the SA-LoxP-EX1-LoxP-Neo-LoxP-LA-HSVTK cassette was linearized and electroporated into SV129J ES cells. Gene-targeting-positive ES cells (PCR screen) were injected into C57Bl/6J blastocysts resulting in chimeric mice. The chimeras were crossed to C57Bl/6J mice, resulting in Relnfl/wt mice, verified by PCR and Southern blot. Heterozygous animals were backcrossed to Meox-Cre on the BL6 background to yield germline mutant reeler mice. Heterozygous animals were also backcrossed to CAG-CreERT2 mice to obtain homozygous Relnfl/fl; CAG-Cre mice. These were again backcrossed to Tg2576 mice and offspring used in the experiments were brother/sister crossed CAG-Cre hemizygous and Tg2576 hemizygous mice. To ensure a minimal effect on the behavioral results we have found, all animals that were compared were brother/sister crosses that only differ by the absence or presence of Cre recombinase. Moreover, discovering a robust response like the one discussed here in a mixed background, as opposed to an inbred one, further strengthens the validity of the conclusions, rather than diminishing them. Most importantly perhaps, it further supports the applicability of the results to the even more genetically heterogeneous human population.

Tamoxifen Injections

At 2 months of age, mice were given daily intra-peritoneal injections for 5 days with 135 mg/kg tamoxifen (Sigma) dissolved in sunflower oil. Control mice were injected with sunflower oil vehicle.

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used for the described experiments: NeuN (Millipore Mab377 1:300), NMDAR2B (Cell Signaling 4212S 1:2000), NR2A (Cell Signaling 4205S 1:500), GluR1 (Abcam ab7260 1:2000), GluR2/3 (Millipore 07-598 1:2000), β-actin (Abcam ab8227 1:3000), G10 ((70) 1:1000 for western blotting, 1:500 for immunohistochemistry), 6E10 (Covance SIG-39320), 4G8 (Covance SIG-39220), Dab1 (5091 (71) 1:1000), pGSK3β (Cell Signaling 9336S 1:3000), GSK3β (BD Transduction 610201 1:3000), phosphoTau (Thr231, Invitrogen 44746G 1:5000), AT8 (Thermo #MN1020 1:2000), Tau-5 (Invitrogen AHB0042, 1:5000), pAkt (Ser473, Cell Signaling 9271S, 1:1000), Akt (Cell Signaling 9272S 1:1000), pERK (Cell Signaling 4370 1:1000), ERK (Cell Signaling 4696S 1:1000), pSrc (Biosource 44660 1:1000), Src (Biosource 44-656Z 1:1000), receptor-associated protein (RAP) (692 1:1000). Secondary antibodies used were: goat anti-mouse AlexaFluor 488 (Molecular Probes, 1:1000, for immunohistochemistry), donkey anti-rabbit ECL, HRP-linked (Amersham NA934 1:3000), and donkey anti-mouse 800 and donkey anti-rabbit 680 (Licor, 1:3000, for western blotting).

Western Blotting

Mice were deeply anesthetized with Isoflurane, decapitated, and the hippocampi and cortices rapidly dissected on ice. Tissues were immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. The tissue was homogenized in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, .1% SDS, .5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP40) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 minutes to remove debris and nuclei. To analyze tau protein, tissues were homogenized in buffer (0.1 M MES [pH 6.8], 0.5 mM MgSO4, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 M NaCl, 2 mM PMSF, 20 mM sodium fluoride, 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM benzamidine, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate, 10 μm/ml aprotinin, 10 μm/ml leupeptin, 1 μM okadaic acid), then clarified at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4C. The supernatant was boiled for 5 min in a water bath, put on ice for 5 minutes, and the precipitated proteins removed by centrifugation 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes. The supernatant was saved for analysis, as previously described (3). Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay. 10 μg of protein were resolved on 4–15% Bio-Rad polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in Odyssey (LI-COR) blocking buffer for an hour at room temperature, then incubated overnight in primary antibody. Membranes were protected from light and incubated with 1:3000 Odyssey secondary antibodies, then imaged on the Odyssey CLx Infrared Imaging System. pSrc was quantified using ECL secondary and developed using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate due to low signal (Life Technologies). Blot quantification was performed using Image Studio software.

Behavioral Characterization

All animals were allowed to acclimate in their home cage in the behavior facility for at least an hour prior to experimentation. Experiments were performed between 14:00 and 18:00. After completion of behavioral studies, Reelin knockout was confirmed by western blot, and cKO mice that did not show greater than 95% reduction of Reelin in the forebrain were removed from data analysis.

Rotarod

Mice were placed on a Rotamex rotarod apparatus facing away from the experimenter. The rod was initially rotating at 2 rpm and then accelerated at a rate of 1 rpm/5 sec until the mice fell off the rod or 300 seconds had passed. The time to falling off or the first “spin”, when the mouse completed a full rotation holding on to the rod, ended the trial. The mice received four trials per day over the course of 10 days with a 15-minute inter-trial interval. The slowest of the four trials was thrown out, and the remaining three trials were averaged.

Open Field

Mice were individually placed in the center of a VersaMax animal activity monitor, which contained a 16.5 in × 16.5 in acrylic box with a small layer of bedding. Activity was measured by beam breaks over the course of 60 minutes in bins of 2 minutes each. Movement was analyzed using the VersaDat analysis software.

Elevated Plus Maze

Mice were placed at the center of the elevated plus maze, which consisted of two `open' arms and two `closed' arms. Mice were allowed to explore the maze for 5 minutes, and the time spent in each arm was scored automatically.

Pre-Pulse Inhibition

Mice were placed in a SR-LAB startle response system. After 5 minutes acclimation to a background 70 dB noise, the mice first received five 120 dB tones to record baseline startle. They were then given a series of pseudo-random pairings of a 120 dB tone immediately preceded by a 0 dB, 74 dB, 78 dB, or 86 dB tone. Pre-pulse inhibition was calculated as the percentage of the average startle at each decibel over the average startle at 0 dB (no tone). After prepulse inhibition training, mice were tested for startle amplitude over a range of decibels from 70 to 120 dB.

Morris Water Maze

Mice received a 2-day pre-training prior to Morris water maze in which they were placed in a small tub (12 in × 24 in) to find a fixed, hidden platform. They received 8 trials per day in which they were given 30 seconds to find the platform. Mice who did not reach the platform within 10 seconds for 6 out of 8 trials on the second day did not proceed to the Morris water maze. More than 95% of the mice passed the pre-training. For the Morris water maze, mice were placed in a 120 cm diameter pool that was made opaque with white washable paint. A 10 cm diameter platform was placed in the center of the northeast (`target') quadrant of the pool, 1 cm under the surface of the water. Mice were placed in the pool starting in each of the 4 ordinary (N,S,E,W) directions in a pseudo random order. A mouse was allowed 60 seconds to find the platform, and if unsuccessful they were guided to the platform by the experimenter. After reaching the platform, mice remained there for 5 seconds prior to removal from the pool. Four trials happened per day, with a 5-minute inter-trial interval. Mice were trained for a total of 10 days. On day 11, the platform was removed for the probe trial, in which the mice swam in the pool for 60 seconds, and the time spent in each quadrant was recorded. On day 12, the platform was moved to the southeast corner and its location made obvious using a flag for the visible probe trial. Mouse movements were recorded and analyzed by the HVS Water software (HVS Image).

Fear Conditioning

On day 1, mice were placed in a shock chamber for a 6-minute training period, during the last 3 minutes of which they were exposed to three pairings of a 20-second shock followed by a 2-second 0.6 mA shock. On day 2, mice were placed in the chamber without the tone for 3-minutes and the extent of freezing was recorded. Four hours later, mice were placed in a different context for 7 minutes, and during the last 4 minutes they received 3 exposures to the tone. Mouse freezing was recorded with the FreezeFrame program and analyzed using the FreezeView program (Actimetrics).

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Mice were sacrificed with isoflurane and perfused with 20 mL ice cold PBS followed by 20 mL ice cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Brains were removed and post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C. Brains were immobilized in 5% agarose in PBS and 50 μm thick sections were sliced on a Leica VT1000 S vibratome. Sections were stored in 0.02% sodium azide in PBS at 4 °C. For cresyl violet staining, sections were mounted on charged slides and dried at room temperature overnight. Slides were serially placed in 100% EtOH, 95% EtOH, and ddH2O, then stained in 0.1% cresyl violet. Slides were destained in 95% EtOH, then placed in 100% EtOH and xylene and mounted. NeuN and Reelin immunohistochemistry were done by blocking slices in 3% goat serum for 3 hours at 4 °C, then overnight in 1:300 NeuN or 1:500 G10 antibody. AlexaFluor 594 goat anti-mouse secondary was applied for 2 hours at room temp, and then hippocampi were imaged at 20X for NeuN. Sequential images of the anti-Reelin sections were acquired using the 10X objective and stitched together using Microsoft Image Composite Editor. For Aβ immunostaining, sections were blocked in 3% H2O2 in methanol for 20 minutes followed by 88% formic acid pre-treatment for 3 minutes. The sections were blocked for 2 hours at room temperature with TBS containing 10% normal horse serum, 2% DL-lysine, 0.25% Triton-X and a Fab Mouse IgG (H&L) antibody fragment of anti-mouse IgG (1:1000; Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc. Gilbertsville, PA, USA). Aβ was detected by the antibody 4G8 (1:1000; Covance, Dedham, MA, USA) followed by incubation with biotinylated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody. Bound antibodies were visualized by using ABC-complex (ABC-kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and diaminobenzidine (DAB) kit (Sigma, St Louis, MI, USA).

Golgi Staining

Golgi staining was performed using the FD Rapid GolgiStain Kit (FD Neurotechnologies) according to the kit's instructions. 200 μm thick slices were acquired by vibratome (4). Z-sections of the Golgi-stained brains were acquired to measure the spine density of CA1 apical dendrites. Images were zoomed in 4X to measure the height and width of the spines.

Granule Cell Dispersion

Six serial sections of dorsal hippocampus were taken from each fixed brain and stained with cresyl violet. Images were taken at 20X. The length of the dentate gyrus was divided into 100 μm segments, and at the center of each segment the width was measured. The average width per animal was taken for each n.

Amyloid Beta Quantification

Protein extraction from fresh frozen mouse forebrain (0.4 g) was carried out in 1 mL of 1X TBS containing a protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The tissue was homogenized with Micropestle (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) followed by sonication. The homogenate was centrifuged for 30 minutes at 14,000g at 4 °C. The supernatant (soluble fraction) was transferred into fresh tubes and kept at −80 C until further use. The remaining pellet was re-suspended into 1 ml PBS containing 1% Triton-X followed by sonication and centrifugation as previously mentioned. For the Aβ ELISA, the tissue was homogenized in PBS and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 25 min at 4C. The supernatant was reserved (soluble fraction) and the pellet was homogenized in 0.5M Guanidine, allowed to solubilize for 3 hrs, and then spun at 14,000 rpm for 25 min (insoluble fraction). A sandwich ELISA was performed using antibodies kindly donated by Dr. David Holtzman. Briefly, Nunc Maxi Sorp (Thermo) plates were coated with either HJ2 (anti-Aβ40) or HJ7.4 (anti-Aβ42) and incubated overnight at 4C. Plates were then incubated with blocking buffer for 1.5 hrs. Plates were incubated overnight with the soluble and insoluble tissue samples. The plates were then incubated with HJ5.1 Biotin, which recognizes both forms of Aβ. The plates were coated with Strep-poly-HRP40 (Pierce), and then developed with SuperSlow TMB (Sigma).

Field Electrophysiology and Theta-Burst LTP

Theta-burst LTP was performed as previously described(2). Briefly, mice were deeply anesthetized with Isoflourane and their brains quickly removed and placed in ice-cold high-sucrose slicing solution (in mM: 110 sucrose, 60 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 28 NaHCO3, 0.5 CaCl2, 5 glucose, 0.6 ascorbic acid, 7 MgSO4). 350-μm transverse slices were cut using a Leica VT1000S vibratome. Slices were allowed to recover in ACSF (in mM: 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 10 D-glucose, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4) for 1 hour at room temperature prior to experiments. For recording, slices were transferred to an interface chamber perfused with ACSF at 31 °C. Slices were stimulated in the stratum radiatum using concentric bipolar electrodes (FHC) using an Isolated Pulse Stimulator. The stimulus intensity was set to 40–60% of the maximum peak amplitude, as determined by measuring the input-output curve. After the baseline stabilized, a theta-burst was applied using a train of 4 100-Hz pulses repeated 10 times with 200 ms intervals, and the train was repeated 5 times at 10 second intervals. The resulting LTP was measured for an hour following theta-burst stimulation. Data was analyzed using Labview 7.0.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0, GraphPad Softward, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank David Holtzman for providing the Ab antibodies used for the ELISA studies.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grant F30 AG047799 (to C.L.D.), NIH grant R37 HL63762 (to J.H.), the American Health Assistance Foundation, the Consortium for Frontotemporal Dementia Research, the Bright Focus Foundation, the Lupe Murchison Foundation, and The Ted Nash Long Life Foundation. This work was also supported by the DFG (FR 620/12-1 to M.F.) and Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF, e:bio ReelinSys, to H.B.). M.F. is Senior Research Professor of the Hertie Foundation. Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (grant numbers SFB 780/TP5 to J.H., H.B., and M.F.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: C.L.D., G.T.P., C.R.W., M.S.D., H.H.B., and J.H. designed experiments. C.L.D., G.T.P., C.R.W., M.S.D., A.U., T.P., L.S. and C.C. performed experiments. L.S., T.P., T.K., and I.M. generated and validated the mouse model. C.L.D. and J.H. prepared the manuscript. M.F., H.H.B., and J.H. supervised the project.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The Reelin cKO mice require an MTA from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

References and Notes

- 1.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y, Durakoglugil MS, Xian X, Herz J. ApoE4 reduces glutamate receptor function and synaptic plasticity by selectively impairing ApoE receptor recycling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:12011–12016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914984107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiesberger T, Trommsdorff M, Howell BW, Goffinet A, Mumby MC, Cooper JA, Herz J. Direct binding of Reelin to VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of disabled-1 and modulates tau phosphorylation. Neuron. 1999;24:481–489. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80861-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasser CR, Masiulis I, Durakoglugil MS, Lane-Donovan C, Xian X, Beffert U, Agarwala A, Hammer RE, Herz J. Differential splicing and glycosylation of Apoer2 alters synaptic plasticity and fear learning. Science signaling. 2014;7:ra113. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strasser V, Fasching D, Hauser C, Mayer H, Bock HH, Hiesberger T, Herz J, Weeber EJ, Sweatt JD, Pramatarova A, Howell B, Schneider WJ, Nimpf J. Receptor clustering is involved in Reelin signaling. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:1378–1386. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1378-1386.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beffert U, Morfini G, Bock HH, Reyna H, Brady ST, Herz J. Reelin-mediated signaling locally regulates protein kinase B/Akt and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:49958–49964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bock HH, Herz J. Reelin activates SRC family tyrosine kinases in neurons. Current biology : CB. 2003;13:18–26. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grayson DR, Jia X, Chen Y, Sharma RP, Mitchell CP, Guidotti A, Costa E. Reelin promoter hypermethylation in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:9341–9346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503736102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takasu MA, Dalva MB, Zigmond RE, Greenberg ME. Modulation of NMDA receptor-dependent calcium influx and gene expression through EphB receptors. Science. 2002;295:491–495. doi: 10.1126/science.1065983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, Paul S, Moran T, Choi EY, Nairn AC, Salter MW, Lombroso PJ, Gouras GK, Greengard P. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nature neuroscience. 2005;8:1051–1058. doi: 10.1038/nn1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weeber EJ, Beffert U, Jones C, Christian JM, Forster E, Sweatt JD, Herz J. Reelin and ApoE receptors cooperate to enhance hippocampal synaptic plasticity and learning. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:39944–39952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durakoglugil MS, Chen Y, White CL, Kavalali ET, Herz J. Reelin signaling antagonizes beta-amyloid at the synapse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:15938–15943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908176106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers JT, Rusiana I, Trotter J, Zhao L, Donaldson E, Pak DT, Babus LW, Peters M, Banko JL, Chavis P, Rebeck GW, Hoe HS, Weeber EJ. Reelin supplementation enhances cognitive ability, synaptic plasticity, and dendritic spine density. Learn Mem. 2011;18:558–564. doi: 10.1101/lm.2153511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pujadas L, Rossi D, Andres R, Teixeira CM, Serra-Vidal B, Parcerisas A, Maldonado R, Giralt E, Carulla N, Soriano E. Reelin delays amyloid-beta fibril formation and rescues cognitive deficits in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature communications. 2014;5:3443. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Arcangelo G, Homayouni R, Keshvara L, Rice DS, Sheldon M, Curran T. Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors. Neuron. 1999;24:471–479. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature. 1995;374:719–723. doi: 10.1038/374719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falconer DS. Two new mutants, 'trembler' and 'reeler', with neurological actions in the house mouse (Mus musculus L.) Journal of genetics. 1951;50:192–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02996215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiu S, Korwek KM, Pratt-Davis AR, Peters M, Bergman MY, Weeber EJ. Cognitive disruption and altered hippocampus synaptic function in Reelin haploinsufficient mice. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2006;85:228–242. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tueting P, Costa E, Dwivedi Y, Guidotti A, Impagnatiello F, Manev R, Pesold C. The phenotypic characteristics of heterozygous reeler mouse. Neuroreport. 1999;10:1329–1334. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199904260-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi S, McMahon AP. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Developmental biology. 2002;244:305–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnaud L, Ballif BA, Forster E, Cooper JA. Fyn tyrosine kinase is a critical regulator of disabled-1 during brain development. Current biology : CB. 2003;13:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bock HH, Jossin Y, May P, Bergner O, Herz J. Apolipoprotein E receptors are required for reelin-induced proteasomal degradation of the neuronal adaptor protein Disabled-1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:33471–33479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tallquist MD, Soriano P. Epiblast-restricted Cre expression in MORE mice: a tool to distinguish embryonic vs. extra-embryonic gene function. Genesis. 2000;26:113–115. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<113::aid-gene3>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trotter J, Lee GH, Kazdoba TM, Crowell B, Domogauer J, Mahoney HM, Franco SJ, Muller U, Weeber EJ, D'Arcangelo G. Dab1 is required for synaptic plasticity and associative learning. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:15652–15668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2010-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee GH, Chhangawala Z, von Daake S, Savas JN, Yates JR, 3rd, Comoletti D, D'Arcangelo G. Reelin induces Erk1/2 signaling in cortical neurons through a non-canonical pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:20307–20317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.576249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isosaka T, Hattori K, Yagi T. NMDA-receptor proteins are upregulated in the hippocampus of postnatal heterozygous reeler mice. Brain research. 2006;1073–1074:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brich J, Shie FS, Howell BW, Li R, Tus K, Wakeland EK, Jin LW, Mumby M, Churchill G, Herz J, Cooper JA. Genetic modulation of tau phosphorylation in the mouse. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23:187–192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00187.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haas CA, Frotscher M. Reelin deficiency causes granule cell dispersion in epilepsy. Experimental brain research. 2010;200:141–149. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1948-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinrich C, Nitta N, Flubacher A, Muller M, Fahrner A, Kirsch M, Freiman T, Suzuki F, Depaulis A, Frotscher M, Haas CA. Reelin deficiency and displacement of mature neurons, but not neurogenesis, underlie the formation of granule cell dispersion in the epileptic hippocampus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26:4701–4713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5516-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouche E, Romero-Ortega MI, Henkemeyer M, Catchpole T, Leemhuis J, Frotscher M, May P, Herz J, Bock HH. Reelin induces EphB activation. Cell research. 2013;23:473–490. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Utsunomiya-Tate N, Kubo K, Tate S, Kainosho M, Katayama E, Nakajima K, Mikoshiba K. Reelin molecules assemble together to form a large protein complex, which is inhibited by the function-blocking CR-50 antibody. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:9729–9734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160272497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dulabon L, Olson EC, Taglienti MG, Eisenhuth S, McGrath B, Walsh CA, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES. Reelin binds alpha3beta1 integrin and inhibits neuronal migration. Neuron. 2000;27:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niu S, Yabut O, D'Arcangelo G. The Reelin signaling pathway promotes dendritic spine development in hippocampal neurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:10339–10348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1917-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogers JT, Zhao L, Trotter JH, Rusiana I, Peters MM, Li Q, Donaldson E, Banko JL, Keenoy KE, Rebeck GW, Hoe HS, D'Arcangelo G, Weeber EJ. Reelin supplementation recovers sensorimotor gating, synaptic plasticity and associative learning deficits in the heterozygous reeler mouse. Journal of psychopharmacology. 2013;27:386–395. doi: 10.1177/0269881112463468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podhorna J, Didriksen M. The heterozygous reeler mouse: behavioural phenotype. Behavioural brain research. 2004;153:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ognibene E, Adriani W, Granstrem O, Pieretti S, Laviola G. Impulsivity-anxiety-related behavior and profiles of morphine-induced analgesia in heterozygous reeler mice. Brain research. 2007;1131:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gordon MN, King DL, Diamond DM, Jantzen PT, Boyett KV, Hope CE, Hatcher JM, DiCarlo G, Gottschall WP, Morgan D, Arendash GW. Correlation between cognitive deficits and Abeta deposits in transgenic APP+PS1 mice. Neurobiology of aging. 2001;22:377–385. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kocherhans S, Madhusudan A, Doehner J, Breu KS, Nitsch RM, Fritschy JM, Knuesel I. Reduced Reelin expression accelerates amyloid-beta plaque formation and tau pathology in transgenic Alzheimer's disease mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:9228–9240. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0418-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim KS, Miller DM, Sapienza VJ, Chen CJ, Bai C, Grundke-Iqbal I, Currie JR, H.M. W. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies reactive to synthetic cerebrovascular amyloid peptide. Neurosci. Res. Commun. 1988;2:121–130. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Saido TC, Shoji M, Ashe KH, Younkin SG. Age-dependent changes in brain, CSF, and plasma amyloid (beta) protein in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21:372–381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00372.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoe HS, Lee KJ, Carney RS, Lee J, Markova A, Lee JY, Howell BW, Hyman BT, Pak DT, Bu G, Rebeck GW. Interaction of reelin with amyloid precursor protein promotes neurite outgrowth. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:7459–7473. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4872-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leeb C, Eresheim C, Nimpf J. Clusterin is a ligand for apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) and very low density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) and signals via the Reelin-signaling pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:4161–4172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.529271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim DH, Iijima H, Goto K, Sakai J, Ishii H, Kim HJ, Suzuki H, Kondo H, Saeki S, Yamamoto T. Human apolipoprotein E receptor 2. A novel lipoprotein receptor of the low density lipoprotein receptor family predominantly expressed in brain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:8373–8380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoe HS, Wessner D, Beffert U, Becker AG, Matsuoka Y, Rebeck GW. F-spondin interaction with the apolipoprotein E receptor ApoEr2 affects processing of amyloid precursor protein. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:9259–9268. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9259-9268.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trommsdorff M, Borg JP, Margolis B, Herz J. Interaction of cytosolic adaptor proteins with neuronal apolipoprotein E receptors and the amyloid precursor protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:33556–33560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmid RS, Jo R, Shelton S, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES. Reelin, integrin and DAB1 interactions during embryonic cerebral cortical development. Cerebral cortex. 2005;15:1632–1636. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwon OY, Hwang K, Kim JA, Kim K, Kwon IC, Song HK, Jeon H. Dab1 binds to Fe65 and diminishes the effect of Fe65 or LRP1 on APP processing. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2010;111:508–519. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Homayouni R, Rice DS, Sheldon M, Curran T. Disabled-1 binds to the cytoplasmic domain of amyloid precursor-like protein 1. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19:7507–7515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07507.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lambert JC, Heath S, Even G, Campion D, Sleegers K, Hiltunen M, Combarros O, Zelenika D, Bullido MJ, Tavernier B, Letenneur L, Bettens K, Berr C, Pasquier F, Fievet N, Barberger-Gateau P, Engelborghs S, De Deyn P, Mateo I, Franck A, Helisalmi S, Porcellini E, Hanon O, I. European Alzheimer's Disease Initiative. de Pancorbo MM, Lendon C, Dufouil C, Jaillard C, Leveillard T, Alvarez V, Bosco P, Mancuso M, Panza F, Nacmias B, Bossu P, Piccardi P, Annoni G, Seripa D, Galimberti D, Hannequin D, Licastro F, Soininen H, Ritchie K, Blanche H, Dartigues JF, Tzourio C, Gut I, Van Broeckhoven C, Alperovitch A, Lathrop M, Amouyel P. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nature genetics. 2009;41:1094–1099. doi: 10.1038/ng.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Houser CR. Granule cell dispersion in the dentate gyrus of humans with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain research. 1990;535:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91601-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suzuki F, Junier MP, Guilhem D, Sorensen JC, Onteniente B. Morphogenetic effect of kainate on adult hippocampal neurons associated with a prolonged expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroscience. 1995;64:665–674. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00463-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muller MC, Osswald M, Tinnes S, Haussler U, Jacobi A, Forster E, Frotscher M, Haas CA. Exogenous reelin prevents granule cell dispersion in experimental epilepsy. Experimental neurology. 2009;216:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chai X, Munzner G, Zhao S, Tinnes S, Kowalski J, Haussler U, Young C, Haas CA, Frotscher M. Epilepsy-induced motility of differentiated neurons. Cerebral cortex. 2014;24:2130–2140. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Korwek KM, Trotter JH, Ladu MJ, Sullivan PM, Weeber EJ. ApoE isoform-dependent changes in hippocampal synaptic function. Molecular neurodegeneration. 2009;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levenga J, Krishnamurthy P, Rajamohamedsait H, Wong H, Franke TF, Cain P, Sigurdsson EM, Hoeffer CA. Tau pathology induces loss of GABAergic interneurons leading to altered synaptic plasticity and behavioral impairments. Acta neuropathologica communications. 2013;1:34. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Groc L, Choquet D, Stephenson FA, Verrier D, Manzoni OJ, Chavis P. NMDA receptor surface trafficking and synaptic subunit composition are developmentally regulated by the extracellular matrix protein Reelin. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:10165–10175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1772-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sinagra M, Verrier D, Frankova D, Korwek KM, Blahos J, Weeber EJ, Manzoni OJ, Chavis P. Reelin, very-low-density lipoprotein receptor, and apolipoprotein E receptor 2 control somatic NMDA receptor composition during hippocampal maturation in vitro. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:6127–6136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1757-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang YP, Shimizu E, Dube GR, Rampon C, Kerchner GA, Zhuo M, Liu G, Tsien JZ. Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature. 1999;401:63–69. doi: 10.1038/43432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zurhove K, Nakajima C, Herz J, Bock HH, May P. Gamma-secretase limits the inflammatory response through the processing of LRP1. Science signaling. 2008;1:ra15. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1164263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Telese F, Ma Q, Perez PM, Notani D, Oh S, Li W, Comoletti D, Ohgi KA, Taylor H, Rosenfeld MG. LRP8-Reelin-Regulated Neuronal Enhancer Signature Underlying Learning and Memory Formation. Neuron. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Impagnatiello F, Guidotti AR, Pesold C, Dwivedi Y, Caruncho H, Pisu MG, Uzunov DP, Smalheiser NR, Davis JM, Pandey GN, Pappas GD, Tueting P, Sharma RP, Costa E. A decrease of reelin expression as a putative vulnerability factor in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Botella-Lopez A, Burgaya F, Gavin R, Garcia-Ayllon MS, Gomez-Tortosa E, Pena-Casanova J, Urena JM, Del Rio JA, Blesa R, Soriano E, Saez-Valero J. Reelin expression and glycosylation patterns are altered in Alzheimer's disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:5573–5578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601279103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seripa D, Matera MG, Franceschi M, Daniele A, Bizzarro A, Rinaldi M, Panza F, Fazio VM, Gravina C, D'Onofrio G, Solfrizzi V, Masullo C, Pilotto A. The RELN locus in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2008;14:335–344. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-14308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]