Significance

Flavin mononucleotide (FMN) riboswitches are present in many bacteria and control genes responsible for biosynthesis and/or transport of the vitamin riboflavin. Riboflavin is the direct precursor of the flavoenzyme cofactors FMN and flavin adenine dinucleotide. When FMN levels are adequate, riboflavin biosynthesis and transport are shut down by FMN riboswitches. We now show that the protein RibR from Bacillus subtilis overrides this genetic decision of both FMN riboswitches. The function of RibR was previously unknown. When B. subtilis has an increased demand for flavins, RibR binding to FMN riboswitches allows riboflavin gene expression even in the presence of relatively high levels of FMN. Such an increased demand for flavins occurs when B. subtilis encounters sulphur compounds in its environment.

Keywords: RibR, FMN riboswitch, Bacillus subtilis, flavin mononucleotide, riboflavin

Abstract

Flavin mononucleotide (FMN) riboswitches are genetic elements, which in many bacteria control genes responsible for biosynthesis and/or transport of riboflavin (rib genes). Cytoplasmic riboflavin is rapidly and almost completely converted to FMN by flavokinases. When cytoplasmic levels of FMN are sufficient (“high levels”), FMN binding to FMN riboswitches leads to a reduction of rib gene expression. We report here that the protein RibR counteracts the FMN-induced “turn-off” activities of both FMN riboswitches in Bacillus subtilis, allowing rib gene expression even in the presence of high levels of FMN. The reason for this secondary metabolic control by RibR is to couple sulfur metabolism with riboflavin metabolism.

In the cytoplasm of Bacillus subtilis (as in other bacteria), riboflavin (vitamin B2) is synthesized in a series of enzymatic reactions starting from GTP and ribulose-5-phosphate (1) (see pathway and enzymes in SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The bifunctional flavokinase/flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-synthetase RibFC is responsible for the rapid and almost quantitative conversion of cytoplasmic riboflavin into its biologically active derivatives flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and FAD (2). FMN and FAD are cofactors of flavoenzymes, which carry out a large variety of different biochemical reactions (3). Notably, 1.4% of the B. subtilis proteins (58 out of 4,245) depend on either FMN or FAD (4), and it is the cytoplasmic FMN level that represents the measurand for the flavin gene regulatory system. The riboflavin biosynthetic genes ribDG, ribE, ribAB, ribH, and ribT of B. subtilis form a transcription unit (see SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). The 5′-untranslated region of the corresponding mRNA contains an FMN riboswitch (“ribDG FMN riboswitch”) that regulates expression of the gene cluster ribDG, ribE, ribAB, ribH, and ribT (5, 6). The ribDG FMN riboswitch consists of an FMN-responsive aptamer and an overlapping expression platform. FMN controls riboflavin biosynthesis in B. subtilis by binding to the aptamer portion of the ribDG FMN riboswitch. This leads to the formation of an intrinsic transcription terminator within the expression platform when FMN levels are high but to an alternative structure (allowing transcription of the downstream genes) when FMN levels are low. As a consequence of the latter, riboflavin is synthesized. A second FMN riboswitch (“ribU FMN riboswitch”) controls translation of the monocistronic ribU mRNA of the riboflavin importer RibU (see SI Appendix, Fig. S2B) (6, 7). The ribU FMN riboswitch operates by forming an intrinsic ribosomal binding site sequestrator when FMN levels are high but adopts an alternative structure when FMN levels are low (allowing translation of the ribU mRNA). As a consequence of the latter, riboflavin is transported into the cell.

B. subtilis RibR was described as a flavokinase with unknown cellular function (8). The gene ribR is part of a transcription unit comprising 12 genes (snaA, tcyJ, tcyK, tcyL, tcyM, tcyN, cmoO, cmoI, cmoJ, ribR, sndA, and ytnM) (Fig. 1A) (9). The gene products of this operon (except for RibR) are involved in the uptake and degradation of sulfur compounds, and expression of these genes was found to strongly be enhanced in the presence of methionine or taurine (2-aminoethanesulfonic acid) (9–11). Using a yeast three-hybrid system, it was shown that RibR specifically interacts with the B. subtilis ribDG FMN riboswitch in vivo (12). This interaction could be located to the carboxy-terminate part of the protein, whereas the flavokinase activity of RibR tentatively was assigned to the N-terminal part of RibR (N-RibR). We now show that RibR regulates the activity of both B. subtilis FMN riboswitches and couples riboflavin synthesis and transport to sulfur metabolism.

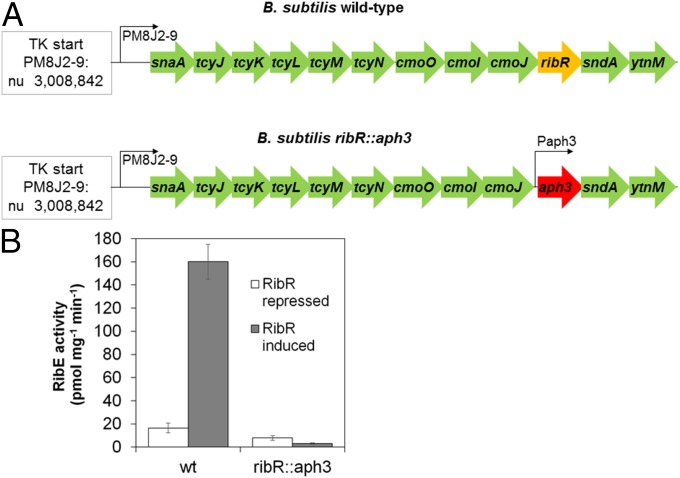

Fig. 1.

Induction of RibR leads to induction of the riboflavin biosynthetic enzyme RibE. (A) Schematic representation of the snaA, tcyJ, tcyK, tcyL, tcyM, tcyN, cmoO, cmoI, cmoJ, ribR, sndA, and ytnM operon of a wild-type B. subtilis strain (Top) and of a recombinant strain (ribR::aph3) (Bottom) in which ribR has been replaced by a kanaymcin resistance gene (aph3). Expression of aph3 is driven by a promoter that also ensures expression of the downstream genes sndA and ytnM. The promoter PM8J2-9 and the transcription start of the operon are shown. (B) Cell-free extracts of B. subtilis wild-type and the ribR deletion strain ribR::aph3 were tested for RibE activity. The strains were either grown in a culture medium containing MgSO4 (RibR repression) or in a medium containing methionine and taurine (RibR induction). In the wild-type strain, RibE activity was increased 10-fold upon induction of RibR. In contrast, RibE activity was not increased in the ribR::aph3 strain in the presence of methionine/taurine. The results of this experiment indicated that RibR is a regulator.

Results

Synthesis of RibR Is Induced When Methionine and Taurine Are Present in the Growth Medium.

The objective of this experiment was to verify the previous finding that synthesis of RibR is induced by methionine and taurine in B. subtilis (10). If true, this would allow us to selectively stimulate the production of RibR in a variety of experiments. To monitor RibR synthesis by Western blot analysis, a recombinant B. subtilis strain carrying ribR fused to nucleotides coding for a tandem affinity purification tag (“TAP-tag”) was generated. This strain was cultivated in a growth medium containing methionine and taurine as the sole sulfur sources or in a medium containing MgSO4 as a sulfur source. As expected, the gene product RibR–TAP-tag was found to be synthesized only when methionine and taurine were present in the growth medium (see SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Induction of RibR Leads to Enhanced Riboflavin Synthase Activity.

The result of the following experiment indicated that RibR is involved in the regulation of riboflavin biosynthesis. Riboflavin synthase (RibE) catalyzes the last step in riboflavin biosynthesis (see SI Appendix, Fig. S1) and was used as a “reporter enzyme” to monitor expression of the riboflavin biosynthesis genes ribDG, ribE, ribAB, ribH, and ribT. Expression of this transcription unit is controlled by the FMN-sensing ribDG FMN riboswitch (see SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). B. subtilis wild-type and a ribR deletion strain (Fig. 1A) were cultivated in the presence of either MgSO4 (RibR repression) or methionine and taurine (RibR induction). In cell-free extracts of RibR-induced wild-type cells, RibE activity was increased 10-fold compared with the noninduced cells (Fig. 1B). The ribR deletion strain, however, did not show enhanced RibE activity upon treatment of the cells with methionine and taurine (Fig. 1B). Western blot analysis confirmed that the amount of RibE was higher in RibR-induced wild-type cells compared with the noninduced cells (see SI Appendix, Fig. S4), ruling out the possibility that a RibR-mediated modification of RibE was responsible for the observed increase in enzymatic activity. Induction of RibR in a recombinant B. subtilis strain using an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible expression plasmid (pHT01-ribR) validated the results obtained by RibR induction of a B. subtilis wild-type strain with methionine and taurine. In the recombinant strain, induction of RibR was achieved by adding IPTG instead of methionine/taurine. As expected, the addition of IPTG as well led to an increased level of RibE activity in cell-free extracts of the recombinant strain (52.0 ± 5.1 pmol·min−1·mg·protein−1) compared with the control strain containing an empty expression vector (8.0 ± 0.9 pmol·min−1·mg·protein−1).

Because RibR was reported to be an RNA binding protein (12) and riboflavin biosynthesis/transport (rib) genes are regulated by FMN riboswitches (6, 7), we hypothesized that RibR would interfere with FMN riboswitch function. The following experiments show that this indeed is the case and that there is a physiological need for such a secondary control.

RibR Induces Synthesis of the Riboflavin Transporter Gene ribU.

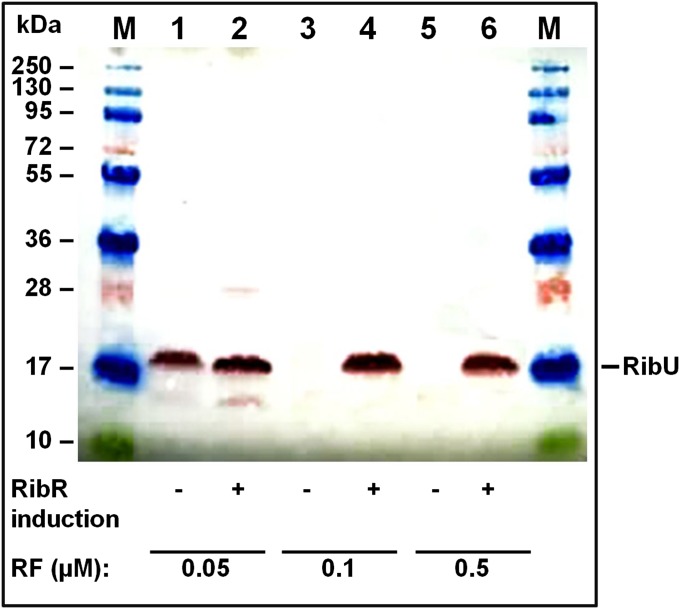

The result of the next experiment suggested that RibR not only stimulates riboflavin biosynthesis but also is involved in regulation of riboflavin transport. The riboflavin transporter RibU of B. subtilis catalyzes uptake of riboflavin from the growth medium (13), and expression of the corresponding gene ribU is controlled by a second FMN riboswitch present in B. subtilis, the FMN-sensing ribU FMN riboswitch (6). To monitor synthesis of the membrane protein RibU by Western blot analysis, a recombinant B. subtilis strain (ΔribE::tetr/ribU-his8) was used that produced a His8-tagged version of RibU (13). In addition, this strain was riboflavin auxotrophic (due to the deletion of ribE), which allowed us to control cytoplasmic riboflavin levels by adding different amounts of riboflavin to the culture medium. B. subtilis ΔribE::tetr/ribU-his8 was cultivated in a medium containing MgSO4 (RibR repression) or methionine and taurine (RibR induction). Riboflavin was added to the culture medium to allow growth of this riboflavin auxotrophic B. subtilis strain. Western blot analysis of membrane fractions revealed that RibU was produced upon induction of RibR at all riboflavin concentrations tested (Fig. 2). Upon repression of RibR, however, RibU synthesis occurred only at a comparably low riboflavin concentration of 0.05 µM riboflavin (not at 0.1 µM or 0.5 µM). We concluded from this that the second FMN riboswitch present in B. subtilis is also regulated by RibR.

Fig. 2.

Induction of RibR induces synthesis of the riboflavin transporter RibU. Membrane fractions of a recombinant B. subtilis strain (ΔribE::tetr/ribU-his8) that produced a His8-tagged version of RibU (20 kDa; see bar) were analyzed by SDS/PAGE/Western blot using anti–penta-His6 antibodies. The same amount of total protein was applied to each lane. Positions of molecular weight standards (in kDa) of a prestained protein marker (M) are shown. B. subtilis ΔribE::tetr/ribU-his8 is riboflavin auxotrophic, and thus riboflavin had to be added to the growth medium to support growth of the cells. Riboflavin is almost completely converted to FMN in the cytoplasm of B. subtilis (2). FMN turns off FMN riboswitches. (Lane 1) Analysis of a membrane fraction prepared from cells grown in the presence of MgSO4 (no RibR induction, –) and 0.05 µM riboflavin (RF). Due to low riboflavin/FMN levels, the FMN riboswitch was turned on and RibU was produced. (Lane 2) RibU was synthesized in the presence of methionine and taurine (RibR induction, +) and 0.05 µM riboflavin. (Lane 3) In the presence of MgSO4 (no RibR induction, –) and 0.1 µM riboflavin, RibU was not produced. The high amount of riboflavin (and consequently of FMN) turned off FMN riboswitch-mediated expression of ribU. (Lane 4) In the presence of methionine/taurine (RibR induction, +) and 0.1 µM riboflavin, RibU was synthesized although high levels of riboflavin/FMN were present. In lanes 5 and 6 (0.5 µM riboflavin), the same effects (as in lanes 3 and 4) were observed, and RibR appears to override the genetic decision of the riboswitch.

Coexpression of ribR Affects Expression of a Reporter Gene Coupled to B. subtilis FMN Riboswitches.

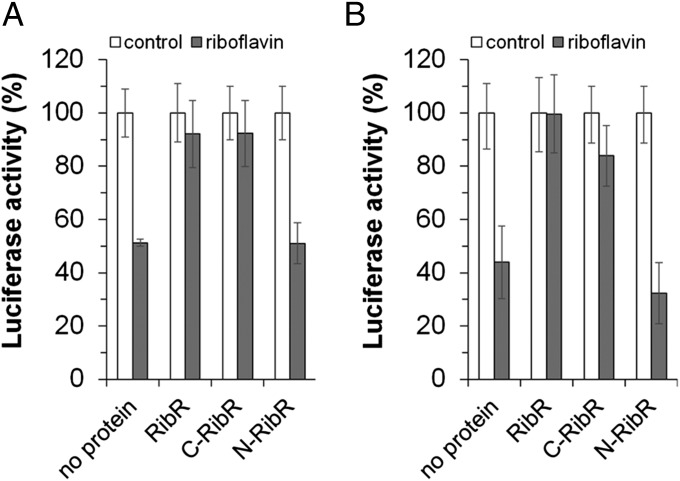

To study the presumed regulatory function of RibR in vivo, a specialized Escherichia coli strain CpXFMN was used (see SI Appendix, Fig. S5). This strain was transformed with a first plasmid that allowed monitoring of FMN riboswitch controlled luciferase gene (luc) expression. A second plasmid was introduced into the same strain allowing (co)production of different forms of RibR (see below in this section). Luciferase (Luc) activity was determined in the different strains, and the results of these experiments are summarized in Fig. 3A. In the absence of RibR, Luc activity was reduced upon treating the cells with riboflavin, suggesting that the ribDG FMN riboswitch of B. subtilis reduced expression of the reporter gene luc when exposed to the flavin. The coproduction of full-length RibR alleviated the regulating effect of the riboswitch and led to almost full Luc activity. This effect of RibR could be located to the C-terminal part of RibR (C-RibR, amino acids 90–230), as coproduction of N-RibR (amino acids 1–89) did not show this alleviating effect. Similar experiments with similar results were obtained by testing the ribU FMN riboswitch coupled to luc, and the corresponding data are summarized in Fig. 3B. The presence of the different versions of RibR (all His6-tagged) in the test strain was confirmed by Western blot analysis using anti–penta-His antibodies. In all strains, similar amounts of RibR (or N-RibR or C-RibR) were found.

Fig. 3.

Coexpression of ribR affects expression of a reporter gene coupled to B. subtilis FMN riboswitches. (A) Different E. coli strains containing the expression plasmid pPrib–RibDG–RFN–luc (Luc reporter gene luc transcriptionally fused to the B. subtilis ribDG FMN riboswitch) in addition to either pET28a–ribRfull (producing full-length RibR, RibR), pET28a–ribRC-terminus (producing the C-RibR, amino acids 90–230), or pET28a–ribRN-terminus (producing the N-RibR, amino acids 1–89) were cultivated in the absence (control) or presence of 5 µM riboflavin. Transcription of the reporter gene initiated at the E. coli promoter pPrib (16). The strains were grown to the exponential phase, and RibR synthesis was induced by IPTG. Luc activity was determined in cell-free extracts prepared from these cells. In the absence of IPTG-induced proteins (no protein), Luc activity was reduced upon addition of riboflavin (which was converted to the effector FMN by the cells). IPTG-induced coproduction of RibR and of C-RibR alleviated the regulating effect of the riboswitch. Luc activity was not reduced even though FMN was present in the cells. Coproduction of N-RibR did not show this alleviating effect. (B) Similar expression experiments (using pPrib–RibU–RFN–luc) with similar results were produced using the B. subtilis ribU FMN riboswitch (“RibU-RFN”) translationally coupled to luc.

Purification and Biochemical Characterization of RibR.

To study B. subtilis RibR functions in vitro, we set out to purify His6-tagged RibR from a recombinant E. coli strain (see SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). Purified RibR-His6 rapidly precipitated, and thus these preparations could not be used in our subsequent in vitro studies. However, purified maltose binding protein (MBP) fusions of RibR (and variants thereof) (see SI Appendix, Fig. S6B) were soluble. The different fusion proteins (MBP–RibR, full-length RibR fused to MBP; MBP–N-RibR, RibR amino acids 1–89 fused to MBP; MBP–C-RibR, RibR amino acids 90–230 fused to MBP) were tested for flavokinase activity (see SI Appendix, Table S1). The data revealed that it was N-RibR that had flavokinase activity and that this enzymatic activity of RibR was about 21 times lower compared with the major flavokinase RibFC of B. subtilis (2). We concluded that RibR does not contribute significantly to the FMN pool within cells. Our biochemical studies also confirmed the previous finding (14) that RibR represents a flavokinase that is specific for reduced riboflavin (dihydroriboflavin or riboflavinH2) (SI Appendix, Table S1).

FMNH2 Is a Stronger Effector of the B. subtilis ribDG FMN Riboswitch Compared with FMN.

FMN is a planar compound, whereas the reduced form of FMN (FMNH2) has a roof-like shape (15). Moreover, RibR was shown to be specific for reduced flavins (see Purification and Biochemical Characterization of RibR). In light of this, we hypothesized that FMN riboswitches in general may have a different reactivity with regard to FMN and FMNH2 and tested the regulating activity of these structurally different effectors. A plasmid carrying the E. coli ribB promoter Prib (16) and the B. subtilis ribDG FMN riboswitch transcriptionally fused to the reporter gene luc was used as a template in an in vitro transcription/translation reaction (17). We measured a reduction of luc expression in the presence of FMN and also of FMNH2 (see SI Appendix, Fig. S7). The amount of flavin needed for a 50% reduction (T50) of Luc activity in the in vitro transcription/translation assay is a measure for the apparent ligand affinity of the FMN riboswitch aptamer domain and was estimated from the data in SI Appendix, Fig. S7. T50 for FMN was 12.4 µM and T50 for FMNH2 was 3.2 µM, indicating that FMNH2 was a more efficient effector. As a consequence, we used FMNH2 as an effector in the subsequent assays.

C-RibR Counteracts the “Turn-Off” Activities of FMN Riboswitches.

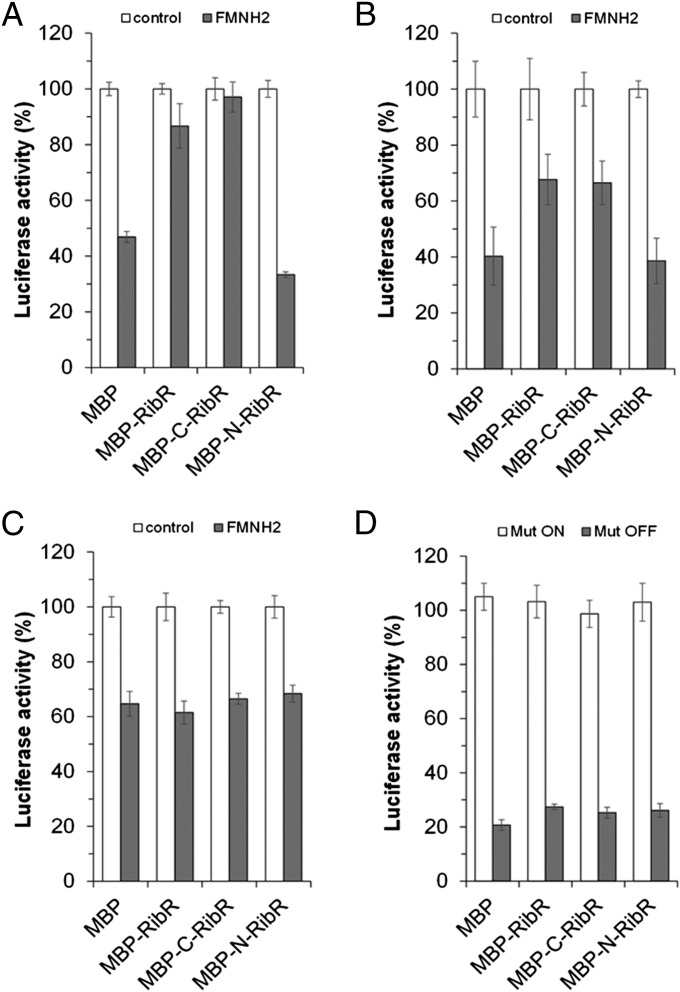

To validate the results of the coexpression experiments suggesting a regulatory role for RibR, in vitro transcription/translation assays were carried out in the presence or absence of purified MBP–RibR or truncated versions thereof (MBP–N-RibR or MBP–C-RibR; see SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). We measured a reduction of reporter enzyme (Luc) activity upon addition of FMNH2 to the assay where only MBP was present (Fig. 4A). The addition of MBP–RibR and MBP–C-RibR alleviated the regulating effect of the ribDG FMN riboswitch; that is, almost full Luc activity was found even though the effector FMNH2 was present (Fig. 4A). This was not the case when MBP–N-RibR was added to the assay. Very similar results were obtained when the B. subtilis ribU FMN riboswitch was tested (Fig. 4B). In the case of the B. subtilis ribU FMN riboswitch, the alleviating effect of RibR appeared to be less pronounced but again could be allocated to the C-terminal part of the protein.

Fig. 4.

The C-RibR counteracts the turn-off activities of FMN riboswitches in vitro. (A) The reporter plasmid pPrib–RibDG–RFN–luc (see Fig. 3A) was used as a template for in vitro transcription/translation assays in the absence (control) or presence of FMNH2 (the reduced form of FMN) and in the presence or absence of RibR (and variants thereof) purified as MBP fusions (see SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Transcripts were generated using E. coli RNA polymerase. In the presence of MBP, the addition of FMNH2 led to the reduction of the reporter enzyme Luc, indicating an FMN riboswitch-mediated reduced luc expression. In contrast, the presence of full-length RibR (MBP–RibR) as well as the presence of C-RibR (MBP–C-RibR, amino acids 90–230) led to almost full Luc activity (control levels), although FMNH2 was present. The addition of MBP–N-RibR (amino acids 1–89) did not have such an effect. (B) Same as in A, however the reporter plasmid pPrib–RibU–RFN–luc was used as a template for in vitro transcription/translation assays. The presence of MBP–RibR or MBP–C-RibR counteracted the turn-off activity of the B. subtilis ribU FMN riboswitch. (C) Same as in A, however the reporter plasmid pPrib–RibE–RFN–luc was used containing the ribE FMN riboswitch from S. davawensis. No alleviating effect of RibR was observed in this reaction—that is, the FMN riboswitch from a different bacterial species was not affected by RibR. (D) The B. subtilis ribDG FMN riboswitch variants Mut ON and Mut OFF (5) were tested in in vitro transcription/translation assays in the presence of FMNH2 using pPrib–RibDG–RFNMutOn–luc and pPrib–RibDG–RFNMutOff–luc. No modulating effect of RibR was observed, indicating that a functional FMN riboswitch is required for RibR activity.

When the B. subtilis FMN riboswitches used in the in vitro transcription/translation assays were replaced by the well-characterized ribE FMN riboswitch of the bacterium Streptomyces davawensis (18), no alleviating effect of RibR was observed (Fig. 4C), showing that RibR activity was specific for the B. subtilis ribDG– and ribU FMN riboswitches. In another control experiment, two different previously described B. subtilis ribDG FMN riboswitch variants (5) were tested. The variant “Mut ON” (see SI Appendix, Fig. S8A) was reported to not be able to terminate transcription even in the presence of high levels of FMN (5). The variant “Mut OFF” (see SI Appendix, Fig. S8B) was reported to terminate transcription constitutively regardless of whether FMN was present or not (5). Both FMN riboswitch variants were tested in the presence of FMNH2 and were found to not be affected by MBP–RibR, MBP–C-RibR, or MBP–N-RibR (i.e., no alleviating effect of RibR was observed) (Fig. 4D). This result showed that the regulating activity of RibR depended on a functional riboswitch and, in combination with the other results, strongly supported the idea that the regulatory function of RibR has been adapted to the B. subtilis FMN riboswitches—that is, that this protein has been “tailored” to the particular regulatory needs of B. subtilis.

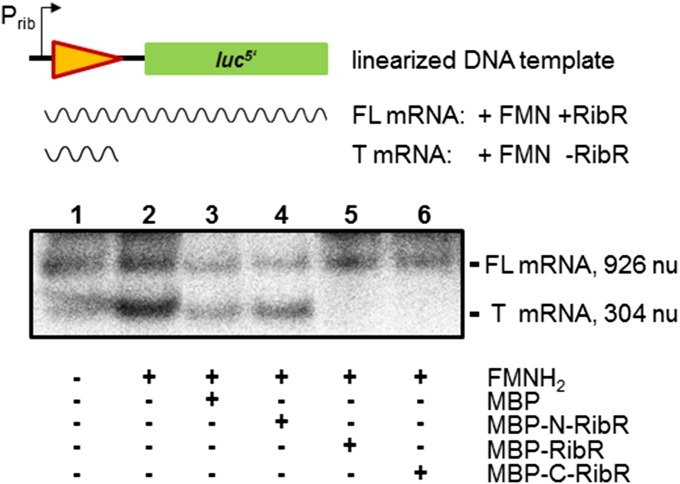

RibR Prevents Transcription Termination of the ribDG FMN Riboswitch.

The following experiment was performed to show that RibR overrides the genetic decision of FMN riboswitches, which would explain why RibR leads to high levels of reporter enzyme activity even in the presence of FMNH2 (which otherwise reduces luc gene expression; see C-RibR Counteracts the “Turn-Off” Activities of FMN Riboswitches). A linear DNA that contained the E. coli ribB promoter Prib (16) and the B. subtilis ribDG FMN riboswitch transcriptionally fused to a truncated reporter gene luc was used as a template in an in vitro transcription reaction using E. coli RNA polymerase (Fig. 5). The DNA template was transcribed in the presence or absence of purified MBP (controls), MBP–RibR, or truncated versions thereof (MBP–N-RibR or MBP–C-RibR; see SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). As expected (6), we found a reduction of the full-length product mRNA upon addition of FMNH2 to the assay reaction where only MBP was present and an increase of a shorter transcript representing the prematurely terminated mRNA (Fig. 5). The addition of MBP–RibR and MBP–C-RibR alleviated the regulating effect of the ribDG FMN riboswitch. An increased amount of the full-length transcript was detected even in the presence of FMNH2, which in the absence of RibR led to transcription termination. The addition of MBP–N-RibR did not have such an effect, indicating that the C-RibR was responsible for the prevention of transcription termination (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

RibR prevents transcription termination of the ribDG FMN riboswitch. A fragment of the reporter plasmid pPrib–RibDG–RFN–luc (see Fig. 3A) was used as a template for an in vitro transcription assay in the absence (–) or presence (+) of FMNH2 as indicated and in the presence or absence of RibR (and variants thereof) purified as MBP fusions (see SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Transcripts were generated using E. coli RNA polymerase. In the absence of FMNH2 (lane 1), transcription continued until RNA polymerase reached the end of the DNA template (see scheme; triangle represents the B. subtilis ribDG FMN riboswitch; arrow represents E. coli ribB promoter; luc5′ represents the 5′ part of the luc gene), resulting in a full-length mRNA (FL). The transcripts were separated by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis and detected using ethidium bromide staining. The intensity of the band indicated the amount of product mRNA synthesized. In the presence of FMNH2, transcription termination was mediated by the B. subtilis ribDG FMN riboswitch, and a shorter transcript of 304 nu was synthesized (T) (lane 2). This shorter transcript was also observed in the presence of FMNH2 and MBP (lane 3). The presence of full-length RibR (MBP–RibR) as well as the presence of the C-RibR (MBP–C-RibR) alleviated this terminating FMN riboswitch function and resulted in an increased amount of the full-length transcript (FL; 926 nu) (lanes 5 and 6). The addition of the N-RibR (MBP–N-RibR) did not have such an effect (lane 4).

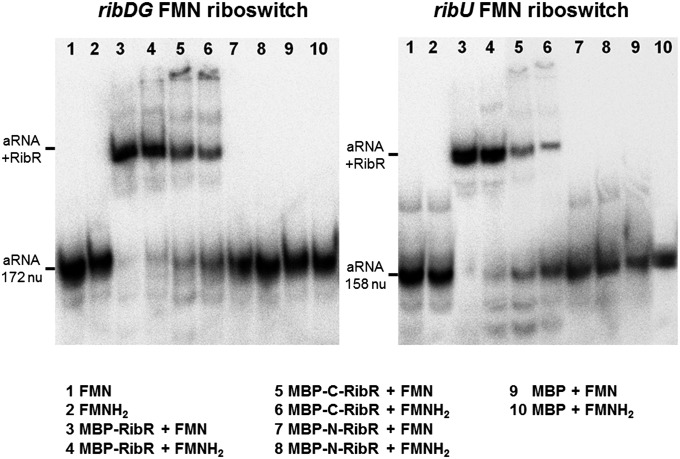

RibR in Vitro Binds to the Aptamer Domains of Both FMN Riboswitches in B. subtilis.

The following experiment was carried out to in vitro verify binding of RibR to FMN riboswitch RNAs, which previously has been shown to occur in vivo using a yeast three-hybrid system (12). An RNA molecule representing the aptamer domain of the ribDG FMN riboswitch was synthesized by in vitro transcription, radiolabeled, and incubated with purified preparations of either MBP–RibR, MBP–N-RibR, or MBP–C-RibR. Only the addition of MBP–RibR or MBP–C-RibR (representing the RNA binding part of RibR) produced a characteristic shift toward a higher molecular mass in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay. This indicated that a complex between the full-length aptamer RNA and RibR had formed (Fig. 6). The addition of MBP (control) or MBP–N-RibR (representing the flavokinase domain of RibR) did not result in such a shift. A shift was observed in the presence of FMN or FMNH2 only. Similar results were obtained testing the aptamer domain of the B. subtilis ribU FMN riboswitch (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

RibR binds to FMN riboswitch RNAs in vitro. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays of different FMN riboswitch RNA aptamer domains from B. subtilis (aRNA) in the presence of purified RibR–MBP fusions (and variants thereof). The full-length FMN riboswitch RNA aptamer domains were synthesized in vitro, gel-purified, and 5′-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and incubated in the presence or absence of proteins and/or flavins. Lanes 1–10 were loaded as shown. The mixtures were separated on a polyacrylamide gel. In the Left panel, radiolabeled ribDG FMN riboswitch RNA aptamers (172 nucleotides) were analyzed with regard to RibR binding, whereas in the Right panel ribU FMN riboswitch RNA aptamers (158 nucleotides) were tested. The FMN riboswitch effector FMN or FMNH2 was present at a concentration of 5 µM. The presence of MBP–RibR or the presence of the C-terminal portion of MBP–RibR (MBP–C-RibR) produced a gel shift (see “aRNA” and “aRNA + RibR”), indicating that RibR interacted with the riboswitch RNA aptamers and thus changed the mobility of the RNA molecules in an electrical field.

RibR Is Not Directly Involved in Sulfur Metabolism.

The following experiment was done to investigate the physiological role of RibR. A B. subtilis wild-type strain and a ribR deletion strain (B. subtilis ribR::aph3) were cultivated to the exponential growth phase. Two different sulfur sources were used during cultivation, MgSO4 (RibR repression) or methionine/taurine (RibR induction). Polar intracellular metabolites were extracted and analyzed using nontargeted flow injection time-of-flight mass spectrometry (19). In total, 11,161 ions were detected, of which 1,441 ions could be annotated as metabolites based on matching their accurate masses with the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) B. subtilis compound database (20) (see Dataset S1). To determine the metabolic consequences of ribR deficiency, we computed fold changes and statistical significance of all detected metabolite ions between the ribR deletion strain and the wild-type in both growth media. The metabolomics data are consistent with ribR being expressed in the presence of methionine/taurine only, as we observed stronger metabolic changes in the methionine/taurine medium compared with the MgSO4 medium (see SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). The data further strongly suggest that ribR is not directly involved in sulfur metabolism, as the replacement of ribR by a kanamycin resistance gene did not affect levels of metabolites of the major sulfur assimilation pathways (see SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Induction of RibR did not result in increased levels of riboflavin/FMN/FAD or intermediates of their biosynthesis (see SI Appendix, Fig. S9C), although RibR induction enhanced RibE activity. An explanation for this may be that an increased level of FMN/FAD-dependent flavoproteins was present that reduced the total amount of soluble flavins. This prompted us to investigate whether levels of substrates and products of known B. subtilis flavoenzymes were affected by ribR inactivation. Indeed, we observed that several metabolites processed by flavoenzymes were present in higher amounts in the ribR-deficient strain compared with wild-type B. subtilis in the methionine/taurine medium (see SI Appendix, Fig. S9D).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report showing that the activity of a metabolite-sensing riboswitch is modulated by a protein. Whereas it was obvious from our experiments that RibR affected FMN riboswitch-mediated control of gene expression, the physiological meaning of this regulator function was less clear. The B. subtilis gene cluster snaA, tcyJ, tcyK, tcyL, tcyM, tcyN, cmoO, cmoI, cmoJ, ribR, sndA, and ytnM was reported to be transcribed only when sulfur-containing organic compounds such as methionine or taurine were present in the growth medium. This was in line with the finding that many of the enzymes and transporters of the cluster were involved in metabolization of these sulfur compounds (9, 21, 22). In an earlier work, the presence of the flavokinase gene ribR (14) in the gene cluster snaA, tcyJ, tcyK, tcyL, tcyM, tcyN, cmoO, cmoI, cmoJ, ribR, sndA, and ytnM tentatively was explained by the fact that the flavoenzymes CmoI and CmoO required flavin cofactors for activity and that the flavokinase RibR would provide the cell with additional FMN. Our data follow a similar line but suggest that it is not the flavokinase activity of RibR that is of physiological relevance (RibR has a comparably low activity only) but rather its regulating function: RibR prevents transcription termination and consequently allows expression of the riboflavin biosynthesis genes ribDG, ribE, ribAB, ribH, and ribT even at high levels of FMN. This biologically active end product of the riboflavin pathway otherwise would shut down gene expression. Accordingly, RibR prevents sequestration of the ribosomal binding site of the gene ribU, allowing synthesis of the riboflavin transporter RibU even at high levels of FMN. Both activities of RibR lead to an increased amount of riboflavin/FMN/FAD necessary to generate fully cofactor-loaded (active) flavoenzymes. In summary, RibR represents a superordinate regulator that is able to affect the activities of the mechanistically very different FMN riboswitches present in B. subtilis, allowing this bacterium to fine-tune riboflavin metabolism.

At present, it is unclear where exactly RibR binds the aptamer portions of the analyzed FMN riboswitch RNAs, how the RibR/RNA complexes look, and how FMN/FMNH2 affects complex formation of RibR. Also the function of the N-terminal flavokinase domain of RibR is unclear, as the C-terminal FMN riboswitch binding domain of RibR seems to be sufficient to carry out the regulator function. Structural studies are underway that hopefully will also shed light on the question of how RibR binding could prevent formation of the terminator or sequestrator structures to promote the alternative antitermination/antisequestrator stem loops. Structural work on RibR could also lead to a better understanding of riboswitch function in general.

Materials and Methods

An extended version of the materials and methods is available in SI Appendix.

Chemicals.

All chemicals and oligonucleotides were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions.

Information with regard to strain construction, plasmids, and growth conditions can be found in SI Appendix.

Purification of Recombinant Proteins.

His6-tagged RibR was purified from cell-free extracts by column chromatography using Ni2+–nitrilotriacetic–agarose (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing the purified enzyme were pooled and desalted using Vivaspin columns of the 10 kDa cutoff column (GE Healthcare). The different forms of RibR were produced as fusions to the well-soluble MBP of E. coli and purified according to standard protocols. Protein was determined according to Bradford (23).

Assay of RibE.

RibE was assayed as described (18). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Coexpression Experiments.

These experiments were performed using E. coli CpXFMN transformed with either pPrib–RibDG–RFN–luc or pPrib–RibU–RFN–luc generating two different recombinant strains. These two strains were transformed with pET28a either carrying ribR, ribR-C, or ribR-N. The strains were aerobically grown at 37 °C in LB to an OD600 of 0.4 (either in the absence or presence of 5 µM riboflavin). At this point, 100 µM IPTG was added to the cultures. The cells were grown for another 2 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 4 °C, 10 min) and suspended in 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.5. Cell-free extracts were prepared by passing the cells through a French press at 2,000 bar. Centrifugation (8,500 rpm, 4 °C, 20 min) removed cell debris and unbroken cells. Aliquots of 10 µL of a dilution of these cell-free extracts were mixed with 50 µL Luciferase Assay Reagent (Promega). Luc activity was determined using a microtiter plate reader (Tecan Genios Pro microplate reader) as described (17). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4).

In Vitro Transcription/Translation Assay.

The transcription/translation assay was performed using the E. coli T7 S30 Extract System for Circular DNA Kit (Promega), which contains T7 RNA polymerase and, in addition, E. coli RNA polymerase (24). Luc activity was determined as described above. Reducing conditions were achieved by adding 100 µM Na2S2O4. If not otherwise indicated, FMN or FMNH2 was present at a concentration of 5 µM. Preparations of purified MBP–RibR, MBP–N-RibR, and MBP–C-RibR were added to a concentration of 1 µM. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4).

Run-Off Transcription Assay.

Plasmid pPrib–RibDG–RFN–luc was treated with EcoRI/SspI, and the resulting fragment carrying Prib, the ribDG FMN riboswitch, and a 578-bp fragment of luc was used as a template in a run-off transcription assay using E. coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme in a reaction containing 40 mM Tris∙HCl pH 7.9, 6 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 500 µM each rNTP, and 100 U Recombinant RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Promega). When indicated, 50 µM FMN in 100 mM sodium dithionite (FMNH2) and 2 µM of protein were added. The transcripts were separated by using denaturing 2% (wt/vol) agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays.

A 20 pmol sample of gel-purified in vitro-transcribed RNA was 5′-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase. A 20 fmol sample of labeled RNA was mixed with 1 µg yeast tRNA and 1 µg heparin in a 15 µL reaction containing 100 mM Tris∙HCl pH 7.0, 1.0 M KCl, 100 mM MgCl2, and 50 µM FMN or FMNH2. After 15 min of incubation at 37 °C, each sample was mixed with loading buffer (50 %, vol/vol, glycerol; 0.2 % bromophenol blue; 0.5× Tris-borate buffer) and loaded onto a running 6 % native polyacrylamide gel, precooled to 4 °C, with 0.5× Tris-borate as a running buffer. The gel was dried for 30 min at 80 °C, and radioactivity was detected using a FUJI FLA-5000 phosphoimager.

Metabolome Analysis.

The B. subtilis strains were cultivated in a minimal medium until reaching an OD600 of 1.5. Methionine/taurine or MgSO4 was added to the growth medium. Six replicates were performed for each culture and processed as described in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Sekowska (AMAbiotics SAS) for providing us with B. subtilis ΔribR::aph3, and J. Stolz (TU München) for providing us with B. subtilis ΔribE::tetr/ribU-his8. This work was funded by the research training group NANOKAT (FKZ 0316052A) of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: A patent application has been filed describing the potential use of the protein RibR in optimizing riboflavin production strains.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1515024112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fischer M, Bacher A. Biosynthesis of flavocoenzymes. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22(3):324–350. doi: 10.1039/b210142b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack M, van Loon AP, Hohmann HP. Regulation of riboflavin biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis is affected by the activity of the flavokinase/flavin adenine dinucleotide synthetase encoded by ribC. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(4):950–955. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.950-955.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraaije MW, Mattevi A. Flavoenzymes: Diverse catalysts with recurrent features. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25(3):126–132. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macheroux P, Kappes B, Ealick SE. Flavogenomics--A genomic and structural view of flavin-dependent proteins. FEBS J. 2011;278(15):2625–2634. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mironov AS, et al. Sensing small molecules by nascent RNA: A mechanism to control transcription in bacteria. Cell. 2002;111(5):747–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkler WC, Cohen-Chalamish S, Breaker RR. An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding FMN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(25):15908–15913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212628899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sklyarova S, Mironov A. Bacillus subtilis ypaA gene regulation mechanism by FMN riboswitch. Russ J Genet. 2014;50(3):319–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solovieva IM, Kreneva RA, Errais Lopes L, Perumov DA. The riboflavin kinase encoding gene ribR of Bacillus subtilis is a part of a 10 kb operon, which is negatively regulated by the yrzC gene product. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;243(1):51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burguière P, et al. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis ytmI operon, involved in sulfur metabolism. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(17):6019–6030. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.17.6019-6030.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coppée JY, et al. Sulfur-limitation-regulated proteins in Bacillus subtilis: A two-dimensional gel electrophoresis study. Microbiology. 2001;147(Pt 6):1631–1640. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-6-1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan CM, Danchin A, Marlière P, Sekowska A. Paralogous metabolism: S-alkyl-cysteine degradation in Bacillus subtilis. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16(1):101–117. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higashitsuji Y, Angerer A, Berghaus S, Hobl B, Mack M. RibR, a possible regulator of the Bacillus subtilis riboflavin biosynthetic operon, in vivo interacts with the 5′-untranslated leader of rib mRNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;274(1):48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogl C, et al. Characterization of riboflavin (vitamin B2) transport proteins from Bacillus subtilis and Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(20):7367–7375. doi: 10.1128/JB.00590-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solovieva IM, Kreneva RA, Leak DJ, Perumov DA. The ribR gene encodes a monofunctional riboflavin kinase which is involved in regulation of the Bacillus subtilis riboflavin operon. Microbiology. 1999;145(Pt 1):67–73. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-1-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strohbach D, Novak N, Müller S. Redox-active riboswitching: Allosteric regulation of ribozyme activity by ligand-shape control. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45(13):2127–2129. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendoza-Vargas A, et al. Genome-wide identification of transcription start sites, promoters and transcription factor binding sites in E. coli. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedrolli DB, Mack M. Bacterial flavin mononucleotide riboswitches as targets for flavin analogs. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1103:165–176. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-730-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedrolli DB, et al. A highly specialized flavin mononucleotide riboswitch responds differently to similar ligands and confers roseoflavin resistance to Streptomyces davawensis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(17):8662–8673. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuhrer T, Heer D, Begemann B, Zamboni N. High-throughput, accurate mass metabolome profiling of cellular extracts by flow injection-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2011;83(18):7074–7080. doi: 10.1021/ac201267k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanehisa M, et al. Data, information, knowledge and principle: Back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D199–D205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auger S, Danchin A, Martin-Verstraete I. Global expression profile of Bacillus subtilis grown in the presence of sulfate or methionine. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(18):5179–5186. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.18.5179-5186.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Even S, et al. Global control of cysteine metabolism by CymR in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(6):2184–2197. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.6.2184-2197.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedrolli D, et al. The ribB FMN riboswitch from Escherichia coli operates at the transcriptional and translational level and regulates riboflavin biosynthesis. FEBS J. 2015;282(16):3230–3242. doi: 10.1111/febs.13226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.