Significance

Microorganisms are directly influenced by actions of their neighbors, and cooperative behaviors are favored among relatives. Only a few microbial species are known to discriminate between kin and nonkin, and distribution of this trait within sympatric bacterial populations is still poorly understood. Here we provide evidence of kin discrimination among micrometer-scale soil isolates of Bacillus subtilis, which is reflected in striking boundaries between nonkin sympatric conspecifics during cooperative swarming on agar. Swarming incompatibilities were frequent and correlated with phylogenetic relatedness, as only the most related strains merged swarms. Moreover, mixing of strains during colonization of a plant root suggested possible antagonism between nonkin. The work sheds light on kin discrimination on a model Gram-plus bacterium.

Keywords: swarming, biofilm, social evolution, kin recognition, antagonism

Abstract

Kin discrimination, broadly defined as differential treatment of conspecifics according to their relatedness, could help biological systems direct cooperative behavior toward their relatives. Here we investigated the ability of the soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis to discriminate kin from nonkin in the context of swarming, a cooperative multicellular behavior. We tested a collection of sympatric conspecifics from soil in pairwise combinations and found that despite their history of coexistence, the vast majority formed distinct boundaries when the swarms met. Some swarms did merge, and most interestingly, this behavior was only seen in the most highly related strain pairs. Overall the swarm interaction phenotype strongly correlated with phylogenetic relatedness, indicative of kin discrimination. Using a subset of strains, we examined cocolonization patterns on plant roots. Pairs of kin strains were able to cocolonize roots and formed a mixed-strain biofilm. In contrast, inoculating roots with pairs of nonkin strains resulted in biofilms consisting primarily of one strain, suggestive of an antagonistic interaction among nonkin strains. This study firmly establishes kin discrimination in a bacterial multicellular setting and suggests its potential effect on ecological interactions.

Living systems that exhibit cooperation such as insect colonies and multicellular organisms are theoretically open to exploitation by parasites or free-loaders that do not contribute, which can lead to collapse of the system. Kin discrimination is believed to stabilize cooperation by preferentially directing cooperative traits toward genetic relatives who likely share the genes for the traits (1–3). However, kin selection may not be the only mechanism driving evolution of kin discrimination. In fact, recent work indicates that bacterial kin discrimination can also evolve indirectly, possibly as a byproduct of other adaptations (4). The phenomenon of kin discrimination has been studied from many different angles and in different organisms including animals (5), plants (6), social insects (7), amoeba (8, 9), and bacteria (10). Microbes have a rich and varied social life, reflected in competition, cheating, altruism, and cooperation (11, 12). An example of bacterial cooperative behavior is surface swarming, a multicellular movement of flagellated bacteria over solid surfaces. It is dependent on secreted surfactants needed for efficient surface translocation (13). The ability to swarm is a potent survival strategy in low-nutrient, spatially structured environments such as soils and the rhizosphere, where plant exudates are a source of food for which microbes compete (14). Swarming is also important for biofilm assembly and colonization of plant roots (14, 15). Within swarms, kin discrimination may enhance cooperation among the kin swarmer cells by preventing the invasion of competing or antagonistic bacteria. However, in Proteus mirabilis, kin discrimination was associated with harmful behaviors, which occur only between nonkin (16).

Discrimination of self and nonself between interacting swarms has been well studied in P. mirabilis. This Gram-negative urinary tract pathogen exhibits merging of genetically identical swarms, whereas swarms composed of different strains form a visible boundary and do not merge (16–20). Swarm merging has not been strictly correlated with relatedness in P. mirabilis, however, due to the lack of a diverse set of strains. The ability to discriminate between self and nonself during swarming was also studied in Myxobacteria, where incompatibility was always observed between unrelated strains (10). Incompatibility was even detected among some strains with 100% multilocus sequence tag identity (10) and was recently shown to evolve through modifications in many independent genetic loci (4).

The soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis has been shown to exhibit several cooperative traits, yet its potential for kin discrimination during cooperative movement over surfaces has not been addressed before. We address this gap in knowledge by using a swarming assay and a collection of 39 highly related B. subtilis strains isolated from two 1-cm3 soil samples (21) that have been well-analyzed phylogenetically. The strains represent a sympatric population that coexisted at micrometer distances in soil and may have had a potential history of interactions in situ. These 39 strains are thus especially interesting candidates to study bacterial kin discrimination.

We show that this group of sympatric B. subtilis isolates can discriminate kin from nonkin. This phenomenon was reflected in the appearance of a striking boundary line between nonkin swarm groups, which was always observed between swarms of distantly related strains within our collection. The frequency of boundary lines was higher among strains with lower phylogenetic relatedness, whereas the opposite was the case for merging strains, which tended to have very high phylogenetic relatedness. Finally, a subset of strain pairs were mixed and used to inoculate Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Therein, kin strains coexisted close to each other, whereas nonkin strains generally did not. These observations suggest that antagonistic interactions among nonkin may shape B. subtilis sociality in a setting other than meeting swarms.

Methods

Strains and Media.

Strains used in this study and construction of their mutant derivatives are described in Table S1. Briefly, 39 B. subtilis wild-type strains isolated from two samples of 1 cm3 of soil from the sandy bank of the Sava River in Slovenia (21) were used. For fluorescence visualization and plant root experiments, wild-type B. subtilis strains were tagged with a yfp gene linked to a constitutive promotor (p43), yfp and cfp genes linked to the biofilm accessory protein (tapA) promoter, and the red fluorescent protein (mKate2) gene linked to a constitutive hyperspank promotor (SI Methods). Swarming assays were performed on swarming agar (SI Methods).

Table S1.

Strains used in this study

| B. subtilis strain name | Genetic background | Reference | Figure |

| PS-11* | WT | (21) | Fig. S1 |

| CY49 | NCIB 3610 amyE::Phyperspank-mKate2 (Cm) | (41) | — |

| CA018 | NCIB 3610 amyE::PtapA-yfp (Sp) | (42) | — |

| CA019 | NCIB 3610 amyE::PtapA-cfp (Sp) | (42) | — |

| PS-216 | amyE::P43-YFP (Sp) | This work | Fig. 1 |

| PS-216 | amyE::Phyperspank-mKate2 (Cm) | This work | Fig. 1 |

| PS-209 | amyE::P43-YFP (Sp) | This work | Fig. 1 |

| PS-218 | amyE::Phyperspank-mKate2 (Cm) | This work | Fig. 1 |

| PS-216† | amyE::PtapA-yfp (Sp) | This work | Fig. 6 and Fig. S2 |

| PS-216‡ | amyE::PtapA-cfp (Sp) | This work | Fig. 6 and Fig. S2 |

| PS-13 b | amyE::PtapA-yfp (Sp) | This work | Fig. 6 and Fig. S1 |

| PS-218‡ | amyE::PtapA-cfp (Sp) | This work | Fig. 6 |

| PS-209‡ | amyE::PtapA-cfp (Sp) | This work | Fig. 6 and Fig. S1 |

| PS-218† | amyE::PtapA-yfp (Sp) | This work | Fig. S1 |

| PS-209† | amyE::PtapA-yfp (Sp) | This work | Fig. S1 |

| PS-13‡ | amyE::PtapA-cfp (Sp) | This work | Fig. S1 |

| PS-18† | amyE::PtapA-yfp (Sp) | This work | Figs. S1 and S2 |

| PS-18‡ | amyE::PtapA-cfp (Sp) | This work | Fig. S1 |

| PS-51† | amyE::PtapA-yfp (Sp) | This work | Figs. S1 and S2 |

| PS-51‡ | amyE::PtapA-cfp (Sp) | This work | Fig. S1 |

| PS-53† | amyE::PtapA-yfp (Sp) | This work | Figs. S1 and S2 |

| PS-53‡ | amyE::PtapA-cfp (Sp) | This work | Figs. S1 and S2 |

| PS-196† | amyE::PtapA-yfp (Sp) | This work | Figs. S1 and S2 |

| PS-196‡ | amyE::PtapA-cfp (Sp) | This work | Figs. S1 and S2 |

| Escherichia coli plasmids | |||

| Pkm003 | amyE::PspoIIQ-yfp (Sp) | (43) |

The PS-11 strain is a part of the microscale collection of 39 B. subtilis strains used for swarm boundary assays published previously (1).

Strains are shown in yellow font on the figures.

Strains are shown in blue font on the figures.

Swarm Boundary Assay.

For testing discrimination between approaching swarms of different B. subtilis isolates, 7- or 9-cm plates containing B-medium with 0.7% agar were always prepared fresh. Strains were inoculated from fresh LB plates into 3 mL of B-medium and shaken overnight at 37 °C. Overnight cultures were then diluted to 10−4, and 2 μL were spotted on the plates at different locations. Plates were then dried for 5 min, incubated for 2 d at 37 °C, and photographed. The phenotypes of the meeting swarms were assigned from the photos.

Sequencing of recA Houskeeping Gene and Construction of a Phylogenetic Tree of Four Concatenated Genes.

The recA genes of 39 riverbank and 14 desert B. subtilis isolates were amplified by PCR targeting positions 4–1041 of the recA gene (SI Methods). The phylogenetic tree of the four concatenated housekeeping genes was drawn using the minimum evolution method in Mega 4.0 software (SI Methods).

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers.

Accession numbers of the riverbank and reference partial recA nucleotide sequences have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers KR820450–KR820491.

Data Analysis.

Sequences of the four concatenated housekeeping genes were aligned using ClustalW (22) in BioEdit version 7.0.9.0 (23). Distance matrices were exported to Excel, where the data were analyzed and graphically presented. To calculate Pearson correlation coefficients between the nucleotide identity of the four concatenated genes and the swarm interaction phenotypes, the three phenotypes were given the number values as follows: Merging was considered as complete swarming compatibility, to which a value of 1 was assigned; a clearly visible boundary as no swarming compatibility, to which a value of 0 was assigned; and the swarming compatibility between the strains that formed the intermediate phenotype was set to 0.5. Recognition network was conducted in Cytoscape software platform (24).

Plant Colonization Experiments.

Sterilized A. thaliana Col-0 seeds were germinated on Murashige–Skoog medium (Sigma) supplemented with 0.05% glucose and 0.5% plant agar for 6–8 d in a growth chamber at 25 °C. Seedlings were then suspended in 300 µL liquid minimal salts nitrogen glycerol (MSNg) medium in a 48-well plate. Wells were inoculated to OD600 0.02 with equal parts of each bacterial strain, and incubated overnight (15–16 h) with gentle shaking (3 × g) at 25 °C. Plants were then taken out and set on a slide for epifluorescent microscopic imaging of the entire root, from which single images were selected. Each strain combination was tested on three separate roots per experiment, and each experiment was repeated twice. For these experiments, only a subset of strain combinations, which were representative of each swarm interaction phenotype (merging, intermediate, and full boundary), were selected, and the selected strains were affiliated with the three different putative ecotypes (PEs): PS-216, PS-13, PS-18, and PS-51 from PE10; PS-218 and PS-53 from PE32; and PS-196 and PS-209 from PE22. Additionally, the selection was limited to the strains from our collection, which were naturally transformable, thus simplifying strain constructions.

SI Methods

Strains and Media.

Thirty-nine B. subtilis wild-type strains isolated from two samples of 1 cm3 of soil from the sandy bank of the Sava River in Slovenia (21) were used in this study. Strains PS-216-Phyperspank-mKate2 and PS-218-Phyperspank-mKate2 were obtained by transforming the WT PS-216 and PS-218, respectively, with DNA isolated from the strain CY49 (41). The amyE::PtapA-yfp and amyE::PtapA-cfp constructs were created previously (42) and transferred to new strains by transformation. Wild-type B. subtilis strains were tagged with a yfp gene linked to a constitutive promotor (p43), which was inserted at the amyE locus. PkM003 plasmid (43) was used to construct the Pkm3-p43-YFP by EcoRI and HindIII digestion and removal of the spoIIQ region from the original plasmid. The B. subtilis p43 region was amplified with primers p43-F1-EcoRI 5′ CGCGAATTCTGATAGGTGGTATGTTTTCGCTTG 3′ and p43-R1-HindIII 5′ GCGAAGCTTCCTATAATGGTACCGCTATCAC 3′ and was ligated into the PkM003 EcoRI and HindIII sites. The DNA (plasmid or genomic) was introduced to the amyE site of B. subtilis using a standard transformation protocol. For fluorescent protein construction and experiments, appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations were used: 5 μg/mL of chloramphenicol (Cm) and 100 μg/mL of spectinomycin (Sp). Swarming assays were performed on swarming agar (final agar concentration 0.7%), which was based on B-medium composed of 15 mM (NH4)2SO4, 8 mM MgSO4 × 7H2O, 27 mM KCl, 7 mM sodium citrate × 2H2O, 50 mM Tris∙HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM CaCl2 × 2H2O, 1 μM FeSO4 × 7H2O, 10 μM MnSO4 × 4H2O, 0.6 mM KH2PO4, 4.5 mM sodium glutamate, 0.86 mM lysine, 0.78 mM tryptophan, and 0.2% glucose. For plant colonization experiments, liquid MSNg medium containing 5 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7, 0.1 M Mops pH 7, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.05 mM MnCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2, 2 μM thiamine, 700 μM CaCl2, 0.2% NH4Cl, and 0.05% glycerol was used.

PCR Amplification.

The recA genes of 39 riverbank and 14 desert B. subtilis isolates were amplified by PCR with recAF forward primer (5′ AGT GAT CGT CAG GCA GCC 3′) and recAR reverse primer (5′ TTA TTC TTC AAA TTC GAG TTC TTC TTG TGT 3′) targeting positions 4–1041 of the recA gene in a 50 µL reaction mixture containing 20 pmol of each primer, 10 nmol of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Fermentas), 2 µL of template DNA, 5 µL of 10× PCR buffer (Roche), 3 µL of 25 mM MgCl2 (Promega), and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche) (final concentrations). The PCR consisted of 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 53 °C for 60 s, extension at 72 °C for 90 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The amplification of 14 desert Bacillus sp. recA genes and a B. subtilis natto NAF4 recA gene was performed using the same primers and protocol, except PCR consisted of 32 cycles and 2 U Taq DNA polymerase (Roche) and 3 µL template DNA was added in the reaction mixture.

Phylogenetic Tree Construction.

The phylogenetic tree of the four concatenated housekeeping genes was drawn using the Minimum Evolution method (44) in Mega 4.0 software (45). The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 1,000 replicates is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analyzed. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) is shown next to the branches. Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 50% bootstrap replicates are collapsed.

Results

Boundary Line Formation Between Swarms of B. subtilis Soil Isolates.

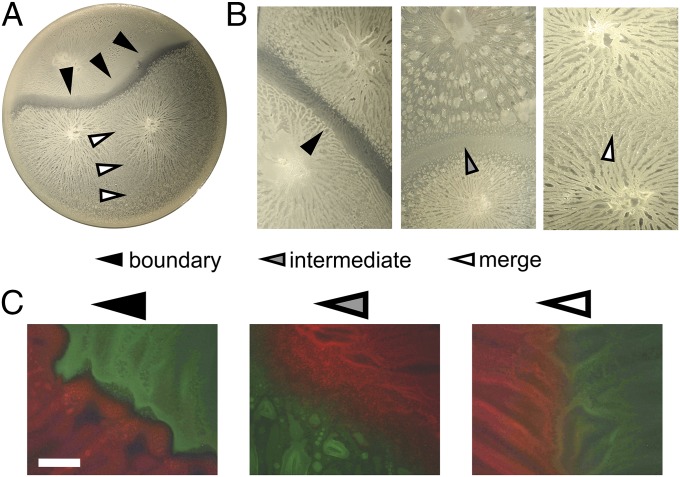

Swarming is a social event, where cells actively and cooperatively move over surfaces colonizing new territory in search of new nutrients. Here we examined interactions between swarms of 39 B. subtilis microscale soil isolates. Although swarms of the same strain always merged, we repeatedly observed a visible boundary at the meeting point of most nonself strains (Fig. 1A). Although we could determine whether or not the dendrites of the two swarms merged, there was considerable variability in the boundary phenotype of different strain combinations (Fig. 1B). Boundaries ranged from very clear and rather striking lines, which we refer to as “boundary” lines (black triangle in Fig. 1B) to those that were less striking but still visible, which we refer to as “intermediate” lines (gray triangle in Fig. 1B). In general, merging or boundary lines were highly reproducible, whereas combinations giving intermediate lines were more variable and had to be repeated more than two times before they were properly categorized. The small inconsistencies and the differences between the boundaries could also be due to minor difficult-to-control environmental changes during cultivation, as was reported in P. mirabilis, where strains subjected to a different cultivation temperature completely lost the ability to identify nonself (25).

Fig. 1.

Different phenotypes of approaching B. subtilis swarms. (A) Merging swarms (white mark) and swarms forming a boundary (black mark) on a 9-cm-wide plate. (B) Close-up of boundary formation on the Left (black mark), intermediate lines in the Middle (gray mark), and merging on the Right (white marks). (C) Swarms of B. subtilis strains constitutively expressing yellow or red fluorescent proteins, imaged under a stereomicroscope. (Scale bar, 1 mm.)

To check whether these boundary lines really represented territorial limits between the strains, fluorescent markers were introduced into a set of strains and photos were taken by fluorescent stereoscope (Fig. 1C). Fluorescent images indicated that the two swarms did not mix when the boundary line or the intermediate line formed between them. The boundary line was associated with a clear zone between two swarms where little or no fluorescent cells were detected, whereas in the case of the intermediate line, cells were still visible in the zone between swarms as though they were in contact but did not mix. In contrast, swarms of identical strains showed a clearly visible, albeit spatially limited, zone of intermixing, probably due to the area exclusion principle. Therefore, some degree of territoriality on the semisolid medium is maintained simply by the “first come, first served” rule. However, when nonself swarms meet, a specific mechanism that prevents mixing between the two strains and promotes formation of the visible boundary lines takes place.

Swarms Affiliated with Different Ecotypes Recognize Each Other as Nonkin.

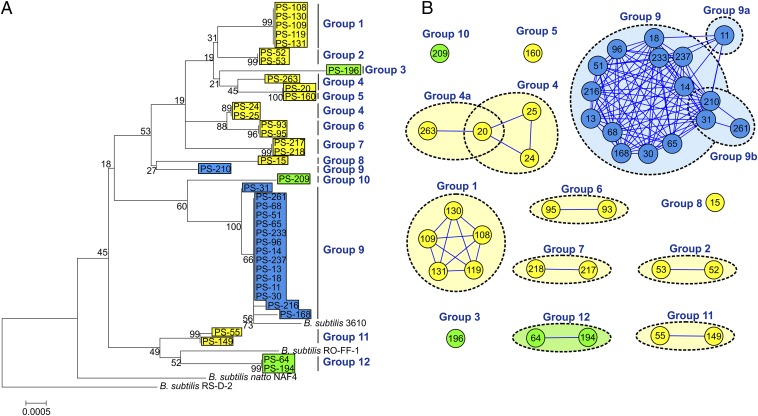

Our collection of 39 B. subtilis strains was isolated from two closely located 1-cm3 soil samples (21) where strains in close proximity may have had a history of interaction. The collection is therefore ideal to correlate swarming interactions with other properties of the strains such as genetic relatedness and ecotype affiliations. To test this, we examined 39 isolates by swarming assay in all 741 pairwise combinations (780 combinations including self–self pairs). All combinations were tested at least twice. Overall, 68% of pairwise combinations formed boundary lines, 16% formed intermediate lines, and 16% merged. We identified 12 different recognition groups among 39 isolates, with a median of two strains per group (Fig. 2), indicating a high threshold for merging between swarms.

Fig. 2.

Recognition groups of a sympatric B. subtilis population. (A) Phylogenetic reconstruction of four concatenated housekeeping genes (gyrA, rpoB, dnaJ, and recA; 3,412 bp) from the 39 B. subtilis microscale soil isolates. Ecotypes are designated by different colors (blue, PE10; green, PE22; yellow, PE32), and swarming recognition groups are indicated on the Right. (B) Recognition network of the microscale soil isolates. Connected nodes represent strains with merging swarms; no connection indicates intermediate or full boundary formation. Colors depict different ecotypes.

These strains have been previously classified into three ecologically distinct groups (ecotypes): PE10, PE22, and PE32 (26) (Fig. 2A, blue, green, and yellow boxes). We therefore speculated that ecologically different strains would discriminate one from another and thus form a boundary line at the contact point of the two swarms. Consistent with our prediction, swarms of different ecotypes never merged, whereas merging strains were always from the same ecotype (Fig. 3). However, more than one recognition group was observed within ecotypes PE22 and PE32 (Fig. 2). Strains of PE32 formed nine separate recognition groups (1, 2, 4–8, 11), whereas four strains of PE22 formed three groups, suggesting a high diversity of swarming interactions can exist within ecotypes. In contrast, most strains of PE10 merged their swarms and fell in a single recognition group. There were only two outliers, PS-11 and PS-261, which sometimes formed intermediate phenotypes with some of the PE10 strains. This could be the early stages of separation of these strains into a new group. Based on these results, we concluded that affiliation with an ecotype is not sufficient to predict merging of swarms, but if two strains are classified into different ecotypes, they will always discriminate between each other.

Fig. 3.

Boundary formation between and within ecotypes. The percent of swarm pairs displaying each phenotype from every ecotype combination, with the total number of combinations given above each column. Boundary lines (blue) and intermediate lines (red) always form between strains of different ecotypes, and merging swarms (yellow) occur only within the same ecotype.

Swarm Interaction Phenotype Correlates with Genetic Relatedness.

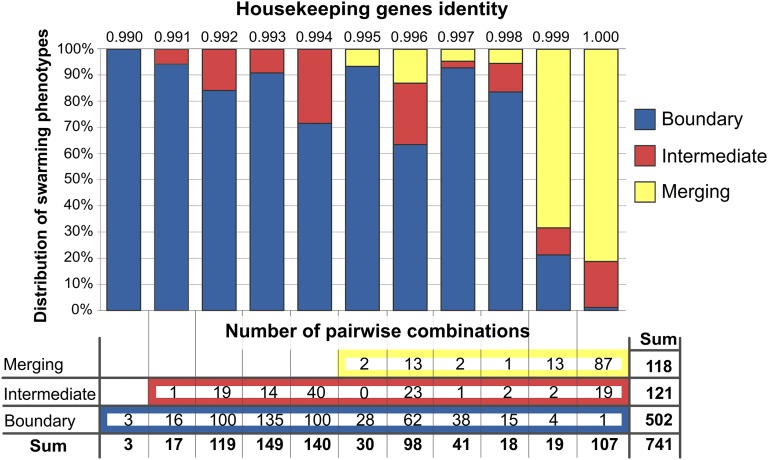

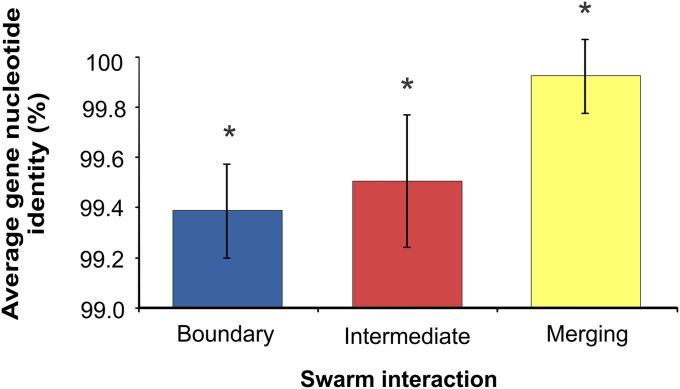

The ability to discriminate those who are genetically dissimilar could stabilize cooperation among kin during swarming. We hypothesized that strains that merged on swarming agar were genetically kin, whereas those that formed a boundary line or intermediate line were nonkin. To test this, we asked whether phylogenetic relatedness correlated with the three different swarming interaction phenotypes: merging of swarms, intermediate line formation, or boundary line formation. To test this, we aligned four concatenated partial housekeeping genes (gyrA, rpoB, dnaJ, and recA; 3,412 bp total) by ClustalW (22). Pairwise distances were rounded off to three decimal digits and grouped in intervals of 0.001 nucleotide identity. In Fig. 4, distributions of swarming interaction phenotypes in each of the pairwise identities of the 741 strain combinations are shown. The distribution of the three swarming interaction phenotypes in each phylogenetic identity group varied considerably, indicating that the diversity within our collection of strains is in the right range to test for kin effects. Out of 118 merging swarm combinations, 100 had at least 0.999 identical housekeeping genes. Some merging strain pairs showed lower nucleotide identity, namely 15 strains from recognition group 9 that merged with PS-210 and three strains from recognition group 4 that merged with PS-20 (Fig. 2B), where the lowest identity associated with merging was still 0.995 (Fig. 4). In contrast, only 1% of strain pairs that formed clear boundary lines (5 combinations out of 512) shared a genetic identity of 0.999 or higher at these loci. In addition, 121 combinations showed an intermediate line, and their genetic identity ranged from 0.991 to 1 (Fig. 4). Overall, the average identity of housekeeping genes between strains that merged was significantly higher than between strains that formed intermediate or boundary lines (Fig. 5). We therefore concluded that the swarm discrimination phenotype correlates with relatedness at the level of housekeeping genes (Pearson correlation r = 0.68), which supports the hypothesis that the boundary line formation represents kin discrimination.

Fig. 4.

Swarm interaction phenotype in relation to phylogenetic relatedness of the interacting strains. Distribution of the three different phenotypes of meeting swarms in each bin of housekeeping gene identity (concatenated dnaJ gyrA recA rpoB). Strains with 99.9% identity and above generally merged with each other, whereas a dramatic boundary line usually formed between swarms showing 99.8% or lower nucleotide identity. Above each column the housekeeping genes identity is shown, and the number of pairwise combinations displaying each phenotype (merging, intermediate, and swarming) in each phylogenetic group is indicated below.

Fig. 5.

Average housekeeping gene identity of the pairwise strain combinations for different interaction phenotypes. Average gene nucleotide values for the three phenotypes differ significantly (*P < <0.001). Error bars represent SD of the average value.

The clustering of strains into recognition groups 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 12 was mostly consistent with their phylogenetic positions (Fig. 2A). The clustering was less consistent for groups 4, 5, and 9, where we found interesting exceptions to the rule. For example, PS-20 (group 4) showed 100% housekeeping gene identity with PS-160 (group 5), but a clear boundary line was still formed. Also, strains from group 9 with 100% core gene identity mostly merged, but two strains, PS-11 and PS-261, deviated from this rule by forming an intermediate line with other strains from the group (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, PS-210, also belonging to group 9, is phylogenetically less related to the rest of group 9 (Fig. 2A), yet it still merged with the strains of this group (Fig. 2B). Only one true boundary formed between strains with 100% identity of the housekeeping genes (PS-20 and PS-160), whereas merging never occurred between strains with identity lower than 99.5% (Fig. 4). These observations suggest that other loci outside the core genome contribute to kin discrimination phenotype and that complete information, although helpful, cannot be obtained by phylogenetic analysis of four housekeeping genes. This is a common problem in kin discrimination systems, as it can be hard for the genes determining phylogenetic relatedness to be in perfect accord with the rest of the genome (3, 27), but the B. subtilis system overall is very accurate.

Coinoculations on Plant Roots.

Having established a genetic correlation to the interactions of swarms on agar plates, we wondered what effect relatedness would have on the lifestyle of B. subtilis in a setting other than swarms meeting in a Petri plate. Because B. subtilis is primarily a soil bacterium and is often found associated with plants, we used an A. thaliana root colonization assay to explore the behavior of kin and nonkin strains in coinoculation experiments. In this assay, B. subtilis cells incubated in liquid containing an A. thaliana seedling swim toward the plant and form a biofilm on its root (28). The question was whether nonkin pairs, as determined in the swarm assay, might not cocolonize on the same regions of a root and whether kin strains would show a stronger tendency to mix.

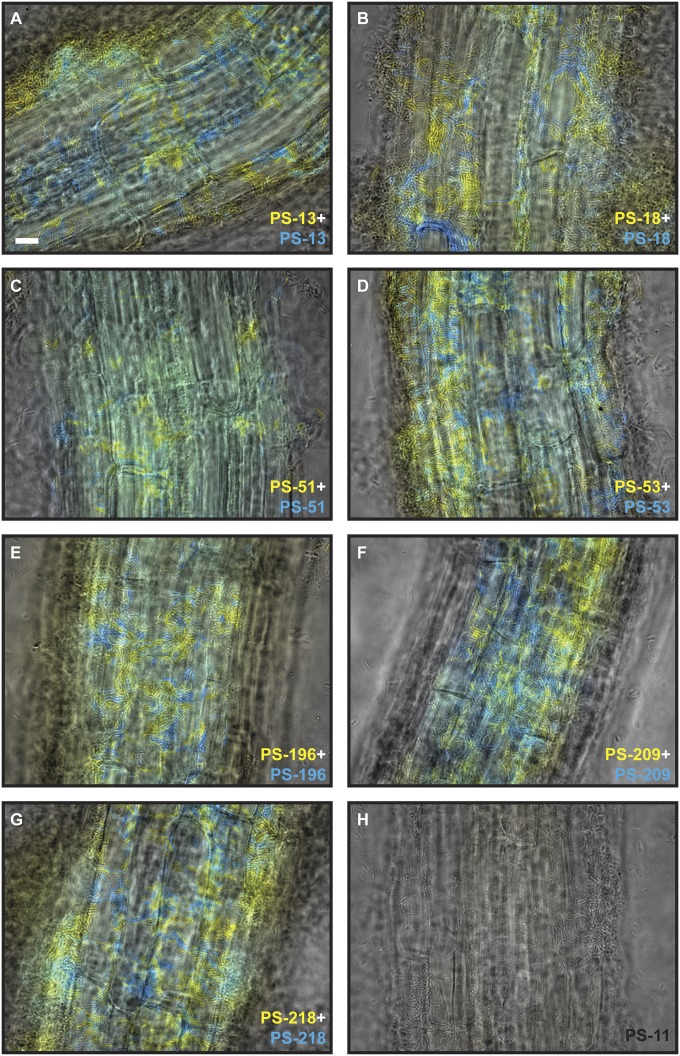

We inoculated plants with equal mixtures of two strains expressing different color fluorescent proteins and then imaged the cells growing on the roots with epifluorescent microscopy. First, we tested the potential differences in ability of different strains to colonize the root as monocultures. Approximately equal colonization of the roots was found, indicating there is no major interstrain difference in ability to attach and grow on A. thaliana (Fig. S1). When two isogenic but differentially labeled strains were combined, the resulting biofilm on the root contained similar numbers of cells expressing each fluorophore and the cells were spatially well mixed (Fig. 6A and Fig. S1).

Fig. S1.

Root cocolonization controls. (A–G) Same-strain pairs of B. subtilis expressing PtapA-yfp or PtapA-cfp were inoculated on A. thaliana roots and tested for their ability to coexist. All same-strain pairs formed biofilms with equal amounts of both differentially labeled strains. (H) Control strain with no fluorescent protein. (Scale bar, 10 µm.)

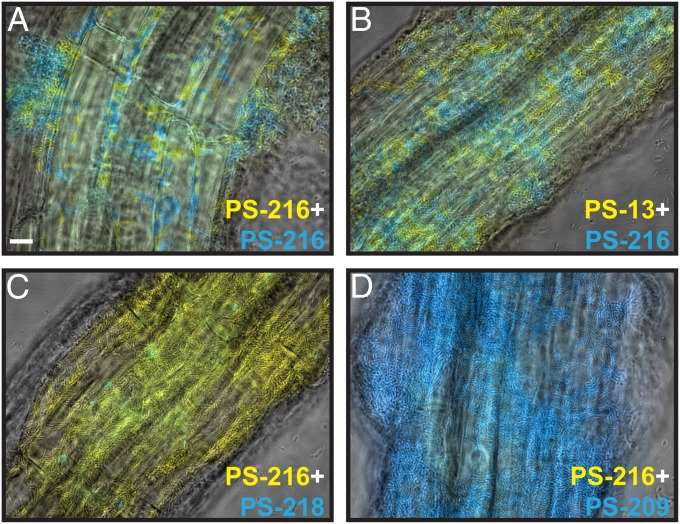

Fig. 6.

Colonization of A. thaliana roots by B. subtilis strains. Shown are overlays of transmitted and fluorescent light micrographs of root-adhered cells expressing PtapA-yfp or PtapA-cfp. Mixture of cells from the same background (A) or strains whose swarms merge (B) results in a biofilm on the root containing similar numbers of both populations. (C and D) Two strains that form a swarm boundary on semisolid agar do not colonize the root equally. (Scale bar, 10 µm.) Shown are representative single images from one root out of at least three replicate plants from two independent experiments.

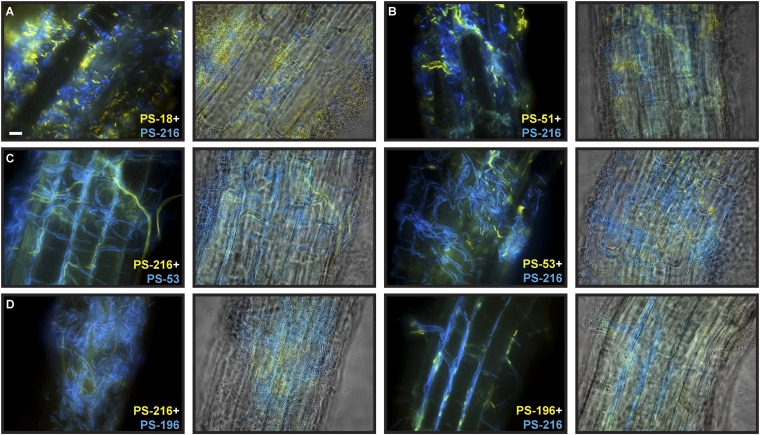

The same pattern was seen when we mixed two strains whose swarms merged on agar: PS-216 combined with either PS-13, PS-18, or PS-51 formed a well-mixed biofilm with visually comparable amounts of both strains attached to the root surface (Fig. 6B and Fig. S2 A and B). However, when strains that formed boundaries between their swarms were mixed, one of the strains dominated on the roots. In the cases of PS-216 + PS-218 and PS-216 + PS-209, one strain dominated over the other strain in every experiment, with only a few cells of the minority strain seen on each root (Fig. 6 C and D). In the PS-216 + PS-53 and PS-216 + PS-196 nonkin mixtures, the dominant strain varied from plant to plant (Fig. S2 C and D). This implies that the observed dominance is likely not simply a consequence of more effective colonization by one strain and that there is some degree of randomness in the determination of dominance. Interestingly, whenever PS-216 cells were among PS-53 or PS-196 cells (nonkin pairs), the PS-216 cells were often long and filamented, possibly indicating activation of a stress response in PS-216. However, these experiments were of a qualitative nature and only provide estimations of coexistence or dominance between strains. In total, all three kin strains and all four nonkin strains behaved as predicted; that is, only nonkin were incompatible (P = 0.03, Fisher exact probability test). These results suggest that the boundaries observed between meeting swarms may represent a discrimination phenomenon that could extend to other multicellular contexts.

Fig. S2.

Colonization of roots by B. subtilis strains. (A and B) Two strains whose swarms merge on semisolid agar plates form a biofilm on A. thaliana roots with equal amounts of both strains. (C and D) Some nonkin strain combinations vary in dominance from root to root. Left and Right panels of A–D show colonization without and with root layer overlay, respectively. (Scale bar, 10 µm.)

Discussion

Here we provide the first evidence, to our knowledge, of kin discrimination during swarming of B. subtilis strains on agar surfaces. We show that 39 strains isolated from the soil micrometer scale were able to discriminate between less and more phylogenetically related swarms by forming remarkable boundaries when meeting nonkin. In addition, nonkin bacteria competed with each other to colonize plant roots, whereas kin strains cocolonized the same root surface. Boundary formation has been previously studied in the soil bacterium Myxococcus xantus (10) and in the pathogen P. mirabilis (16–18, 20). In M. xanthus, the phenomenon was associated with competitive incompatibility of strains (10). In P. mirabilis, a type VI secretion system is responsible for the boundary phenotype (16). This secretion system is a highly specific killing machine directed only toward aggressors that are in the vicinity (29) and have been found only in Gram-negative bacteria (30). The lack of cells in many swarm boundaries (Fig. 1C) and the competition for root surface colonization between nonkin strains (Fig. 6C) may suggest a similar antagonistic mechanism preventing coexistence of nonkin in B. subtilis.

Kin Discrimination Precedes Ecological Diversification.

Bacterial surface motility is an adaptive trait that allows bacteria to disperse and invade new environments when nutrients are limited (31). However, in a spatially structured and less hydrated environment, such as soil, dispersal rates are low (32), and thus closely related bacteria may remain in the vicinity of each other and compete for the same nutrients and space (33). In fact, we found that 39 strains isolated from two 1-cm3 soil samples diversified into 12 recognition groups, which supports the hypothesis of intense competition and antagonism between sympatric relatives. This is in agreement with Vos and Velicer (10), who identified 45 unique recognition types in their collection of 78 M. xanthus isolates from a 16 × 16 cm soil patch. High numbers of recognition types within sympatric populations suggest that kin discrimination occurs early during diversifying evolution. This idea is also supported by the observation that we find more than one recognition group within an ecotype cluster. Strains within an ecotype are more related (less diversified) than those from different ecotypes (34), but members of one ecotype, although highly related, are still genetically different strains with an estimated overall genome identity of 99.4% (35). This is less related than the lowest gene identity we found that still counted as kin (99.5% of four housekeeping genes), indicating there is plenty of room within ecotypes for multiple kin groups.

In this work, we tested the hypothesis that swarm boundaries will be more frequently observed between ecotypes than within ecotypes. Our data confirmed this prediction, as strains within the recognition group consisted always of the same ecotype. However, we also found more than one recognition type within an ecotype. This indicates that diversification of kin recognition types is more rapid than that of ecotypes. Some kin recognition loci, like ids genes that participate in P. mirabilis boundary formation, show increased polymorphism within species (17), which is a phenomenon usually associated with diversifying selection (36, 37). In B. subtilis, the major quorum-sensing system encoded by the comQXPA genes is also under diversifying selection (26, 38, 39). However, kin discrimination loci seem to diversify even faster, as we find three quorum-sensing types (21) but 12 kin recognition types in the collection of 39 strains.

Boundary Formation Is Associated with Genetic Relatedness.

Except for a study performed with M. xanthus (10), to our knowledge no other studies have addressed correlations between phylogenetic relatedness and self/nonself discrimination in sympatric bacterial populations. In our collection of B. subtilis strains, the majority of strain pairs (68%) formed a dramatic boundary line between swarms. This phenotype was the most frequent at 99.8% or lower nucleotide identity of four housekeeping genes (Fig. 4). Although we observed boundary formation even in a few combinations of strains that showed 99.9% identity (and one at 100% identity) as well as intermediate lines among those that shared 100% identity, merging was the most frequent among strains that were in this relatedness group. Merging has not been observed below the 99.5% identity cutoff (Fig. 4). Overall, the frequency of pairs forming the boundary line increased with decreasing identity of housekeeping genes.

Although phylogenetic relatedness corresponded to boundary phenotype in most cases, there were some exceptions. For example, strains PS-20 and PS-160 had 100% identical housekeeping genes but still belonged to different recognition groups (4, 5). This suggests that at least some of the loci responsible for kin discrimination may be under different evolutionary pressure than the phylogenetic markers. Evolution of kin discrimination may be a gradual process where several loci need to match for recognition to occur or need to be different for discrimination to occur. In fact, recognition groups were not always transitive, meaning that if one strain recognized two other strains as kin, these two strains did not necessarily recognize each other as kin. For example, the strain PS-20 merged with PS-263, PS-24, and PS-25, but PS-263 did not merge with PS-24 or PS-25 (Fig. 2B). This would be unlikely to occur if there were just one recognition locus. Also, swarms displayed different phenotypes of boundaries, ranging from striking to rather weak, further suggestive of multiple factors contributing to recognition as kin.

Sorting of Strains on Plant Roots Implies Antagonistic Sociality.

In social settings, within-group genotype richness was found to correlate negatively with group performance, such as swarming in M. xanthus (40), and neighboring strains thus tend to be antagonistic. In the amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum, fruiting bodies composed preferentially of kin cells promote cooperation during multicellular development (8, 9). These results are in line with our observation that only kin strains were able to efficiently coexist in biofilms on plant roots, however we do not observe actual boundaries between nonkin strains on the roots. In the swarm assay, all of the conflict between strains occurs in a narrow region where swarms meet, whereas the root colonization features antagonism throughout and is a conflation of both attaching to and staying on the root. Thus, the results on the root were often more striking (displacement of one strain), but this phenotype could be due to multiple additional factors or even represent different underlying mechanisms. Discriminatory aggressions associated with swarm boundaries were reported previously for P. mirabilis (16) and may also be responsible for B. subtilis swarming incompatibilities. Thus, kin discrimination would be expected to cause a massive increase in diversity within B. subtilis and over time would likely lead to further diversification and ultimately speciation.

We showed here, for the first time to our knowledge, that 39 sympatric B. subtilis isolates, all of which have the ability to swarm on semisolid agar, could discriminate kin from nonkin. This phenomenon was revealed during collective swarming where highly related strains had a tendency to merge, whereas phylogenetically less related ones were separated by a striking boundary line. Remarkably, within only two 1-cm3 soil samples, we altogether determined 12 recognition groups among 39 isolates. We also tested a subset of strains for colonization of plant roots and found coexistence of kin but exclusion of nonkin from common patches on the roots, indicating antagonistic behavior between nonkin.

Altogether, our work demonstrates that Gram-positive bacteria also use kin discrimination mechanisms, which may contribute to territorial sorting of strains according to their genetic relatedness. A high frequency of swarming incompatibilities within a sympatric population suggests that kin discrimination occurred early during their evolutionary trajectory. The phenotypic variability of the boundary lines formed between swarms may imply that multiple loci or alleles are involved in kin discrimination, which might have evolved indirectly as byproducts of selection for some other traits (4). Further studies into the mechanisms behind B. subtilis kin discrimination should shed more light on its evolutionary origins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kevin Foster for valuable discussions and Pascale Beauregard for assistance with the plant root colonization experiments. This work was supported by two grants from Slovenian Research Agency: the Program Grant JP4-116 (to I.M.-M.) and the Slovenia-USA collaboration grant. It was also supported by NIH Grant GM58218 and a John Templeton Foundational Questions in Evolutionary Biology grant (to R.K.) and a Helen Hay Whitney Foundation fellowship (to N.A.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. KR820450–KR820491).

See Commentary on page 13757.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1512671112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hamilton WD. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. J Theor Biol. 1964;7(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West SA, Griffin AS, Gardner A. Evolutionary explanations for cooperation. Curr Biol. 2007;17(16):R661–R672. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strassmann JE, Gilbert OM, Queller DC. Kin discrimination and cooperation in microbes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:349–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rendueles O, et al. Rapid and widespread de novo evolution of kin discrimination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(29):9076–9081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502251112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldman B, Frumhoff PC, Sherman PW. Problems of kin recognition. Trends Ecol Evol. 1988;3(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(88)90075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dudley SA, File AL. Kin recognition in an annual plant. Biol Lett. 2007;3(4):435–438. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsutsui ND. Dissecting ant recognition systems in the age of genomics. Biol Lett. 2013;9(6):20130416. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert OM, Foster KR, Mehdiabadi NJ, Strassmann JE, Queller DC. High relatedness maintains multicellular cooperation in a social amoeba by controlling cheater mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(21):8913–8917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702723104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostrowski EA, Katoh M, Shaulsky G, Queller DC, Strassmann JE. Kin discrimination increases with genetic distance in a social amoeba. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(11):e287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vos M, Velicer GJ. Social conflict in centimeter- and global-scale populations of the bacterium Myxococcus xanthus. Curr Biol. 2009;19(20):1763–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West SA, Griffin AS, Gardner A, Diggle SP. Social evolution theory for microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(8):597–607. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster KR. The secret social lives of microorganisms. Microbe. 2011;6(4):183–186. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kearns DB, Losick R. Swarming motility in undomesticated Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49(3):581–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whipps JM. Microbial interactions and biocontrol in the rhizosphere. J Exp Bot. 2001;52(Spec Issue) suppl 1:487–511. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.suppl_1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietel K, Beator B, Budiharjo A, Fan B, Borriss R. Bacterial traits involved in colonization of Arabidopsis thaliana roots by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Plant Pathol J. 2013;29(1):59–66. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.10.2012.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alteri CJ, et al. Multicellular bacteria deploy the type VI secretion system to preemptively strike neighboring cells. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(9):e1003608. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbs KA, Urbanowski ML, Greenberg EP. Genetic determinants of self identity and social recognition in bacteria. Science. 2008;321(5886):256–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1160033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibbs KA, Wenren LM, Greenberg EP. Identity gene expression in Proteus mirabilis. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(13):3286–3292. doi: 10.1128/JB.01167-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbs KA, Greenberg EP. Territoriality in Proteus: Advertisement and aggression. Chem Rev. 2011;111(1):188–194. doi: 10.1021/cr100051v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wenren LM, Sullivan NL, Cardarelli L, Septer AN, Gibbs KA. Two independent pathways for self-recognition in Proteus mirabilis are linked by type VI-dependent export. MBio. 2013;4(4):e00374-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00374-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stefanic P, Mandic-Mulec I. Social interactions and distribution of Bacillus subtilis pherotypes at microscale. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(6):1756–1764. doi: 10.1128/JB.01290-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall TA. A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/ NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shannon PT, Grimes M, Kutlu B, Bot JJ, Galas DJ. RCytoscape: Tools for exploratory network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:217. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Senior BW. The Dienes phenomenon: Identification of the determinants of compatibility. J Gen Microbiol. 1977;102(2):235–244. doi: 10.1099/00221287-102-2-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stefanic P, et al. The quorum sensing diversity within and between ecotypes of Bacillus subtilis. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14(6):1378–1389. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitri S, Foster KR. The genotypic view of social interactions in microbial communities. Annu Rev Genet. 2013;47:247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beauregard PB, Chai Y, Vlamakis H, Losick R, Kolter R. Bacillus subtilis biofilm induction by plant polysaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(17):E1621–E1630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218984110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basler M, Ho BT, Mekalanos JJ. Tit-for-tat: Type VI secretion system counterattack during bacterial cell-cell interactions. Cell. 2013;152(4):884–894. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benz J, Meinhart A. Antibacterial effector/immunity systems: It’s just the tip of the iceberg. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;17:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hagai E, et al. Surface-motility induction, attraction and hitchhiking between bacterial species promote dispersal on solid surfaces. ISME J. 2014;8(5):1147–1151. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dechesne A, Wang G, Gülez G, Or D, Smets BF. Hydration-controlled bacterial motility and dispersal on surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(32):14369–14372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008392107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadell CD, Foster KR, Xavier JB. Emergence of spatial structure in cell groups and the evolution of cooperation. PLOS Comput Biol. 2010;6(3):e1000716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koeppel A, et al. Identifying the fundamental units of bacterial diversity: A paradigm shift to incorporate ecology into bacterial systematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(7):2504–2509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712205105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kopac S, et al. Genomic heterogeneity and ecological speciation within one subspecies of Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80(16):4842–4853. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00576-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Latta RG. Gene flow, adaptive population divergence and comparative population structure across loci. New Phytol. 2004;161(1):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le Corre V, Kremer A. Genetic variability at neutral markers, quantitative trait land trait in a subdivided population under selection. Genetics. 2003;164(3):1205–1219. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.3.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tortosa P, et al. Specificity and genetic polymorphism of the Bacillus competence quorum-sensing system. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(2):451–460. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.451-460.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ansaldi M, Dubnau D. Diversifying selection at the Bacillus quorum-sensing locus and determinants of modification specificity during synthesis of the ComX pheromone. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(1):15–21. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.1.15-21.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendes-Soares H, Chen I-CK, Fitzpatrick K, Velicer GJ. Chimaeric load among sympatric social bacteria increases with genotype richness. Proc R Soc B. 2014;281:20140285. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Y, et al. A Bacillus subtilis sensor kinase involved in triggering biofilm formation on the roots of tomato plants. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85(3):418–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vlamakis H, Aguilar C, Losick R, Kolter R. Control of cell fate by the formation of an architecturally complex bacterial community. Genes Dev. 2008;22(7):945–953. doi: 10.1101/gad.1645008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sullivan NL, Marquis KA, Rudner DZ. Recruitment of SMC by ParB-parS organizes the origin region and promotes efficient chromosome segregation. Cell. 2009;137(4):697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rzhetsky A, Nei M. A simple method for estimating and testing minimum evolution trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9(5):945–967. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA 4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]