Significance

Successful induction of protective immunity is critically dependent on our ability to design vaccines that can induce dendritic cell (DC) maturation. Here, we investigated the mechanisms by which Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and TLR3 induce DC maturation. We discovered that TLR4 that recognizes LPS from Gram-negative bacteria uses the signaling adaptor Toll–IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β to induce robust activation of NF-κB and MAP kinases that can directly lead to transcription of genes necessary for DC maturation. However, TLR3 that recognizes viral RNA depends on interferon α/β receptor signaling to induce DC maturation. Discovery of these molecular distinctions by which TLRs that recognize bacteria and viruses induce DC maturation will be beneficial to gaining critical insights into induction of adaptive immunity and for successful design of vaccines.

Keywords: MAP kinases, LPS | Poly I:C | MAVS, NF-κB activation

Abstract

Recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on dendritic cells (DCs) leads to DC maturation, a process involving up-regulation of MHC and costimulatory molecules and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. All TLRs except TLR3 achieve these outcomes by using the signaling adaptor myeloid differentiation factor 88. TLR4 and TLR3 can both use the Toll–IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF)-dependent signaling pathway leading to IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) activation and induction of IFN-β and -α4. The TRIF signaling pathway, downstream of both of these TLRs, also leads to DC maturation, and it has been proposed that the type I IFNs act in cis to induce DC maturation and subsequent effects on adaptive immunity. The present study was designed to understand the molecular mechanisms of TRIF-mediated DC maturation. We have discovered that TLR4–TRIF-induced DC maturation was independent of both IRF3 and type I IFNs. In contrast, TLR3-mediated DC maturation was completely dependent on type I IFN feedback. We found that differential activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by the TLR4– and TLR3–TRIF axes determined the type I IFN dependency for DC maturation. In addition, we found that the adjuvanticity of LPS to induce T-cell activation is completely independent of type I IFNs. The important distinction between the TRIF-mediated signaling pathways of TLR4 and TLR3 discovered here could have a major impact in the design of future adjuvants that target this pathway.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a major family of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize conserved microbial products from a diverse class of pathogens (1). Upon recognition of cognate ligands, TLRs initiate a signaling cascade, resulting in activation of several transcription factors including NF-κB, AP-1, and IFN regulatory factors (IRFs) (1). The specificity of signaling is dictated both by the physical location of the receptor and by the signaling adaptor use by each TLR (2). The outcome of TLR signaling is robust activation of induced innate immunity in the form of enhanced phagocytosis (3) and increased reactive oxygen species production (4), as well as synthesis and secretion of several proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines by cells of myeloid lineage (5). TLRs also regulate adaptive immunity by induction of dendritic cell (DC) maturation. DC maturation is a process by which DCs up-regulate expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules. Mature DCs migrate to the draining lymph nodes, interact with antigen-specific T cells, and induce their activation and differentiation. DC maturation is therefore an important control point by which the innate immune system regulates the activation of naïve T cells (6).

All TLRs, with the exception of TLR3, use the adaptor molecule myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) for signal transduction (2). TLR3 recognizes double-stranded (ds) RNA in the endosomes and initiates signaling by using the adaptor Toll–IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF). TLR4 recognizes LPS and uses both MyD88 and TRIF as signaling adaptors (2). The MyD88-dependent signaling pathway, downstream of TLR4, uses the sorting adaptor TIRAP and induces activation of NF-κB and MAP kinases (2). The TRIF pathway of signaling, both downstream of TLR3 and TLR4, in addition to NF-κB, induces activation of IRF3, leading to production of IFN-β and -α4 (2). The type I IFNs induced by TLR3 and TLR4 activation play an important role in several facets of both innate and adaptive immunity (7). Because TLR3 recognizes viral RNA, type I IFN production is important for induction of antiviral immunity. It has also been also demonstrated that type I IFN induction by the TLR3 ligand poly(I:C) is important for DC maturation and its subsequent ability to activate CD4 T cells (8). In contrast, the importance of type I IFN production for innate immunity by the TLR4 signaling pathway is not entirely clear. It has been proposed that the up-regulation of costimulatory molecules on DCs by LPS is due to induction of type I IFNs by the TLR4–TRIF signaling axis (9).

Recently, there has been considerable interest in designing adjuvants for human vaccines that target the TRIF pathway of signaling downstream of TLR4 (10–13). It is clear that the TRIF signaling pathway can induce DC maturation that is sufficient for induction of adaptive immunity without the overwhelming inflammatory response induced by the MyD88 signaling pathway (14). Synthetic dsRNA, the ligand for TLR3, could also be an important candidate to be considered for its adjuvant effect in vaccine formulations. In this study, we examined the role of the TRIF signaling pathway downstream of TLR3 and TLR4 and discovered that TRIF signaling has differential outcomes downstream of these receptors. We find that the dsRNA analog poly(I:C) leads to effective DC maturation only when it also engages the cytosolic sensor and that DC maturation induced by dsRNA is completely dependent on type I IFNs secreted by DCs. However, the TRIF-dependent TLR4-signaling-pathway-induced DC maturation is independent of type I IFNs secreted by DCs. Furthermore, we find that this dependence on type I IFNs is dictated by differential activation of MAP kinases by the TRIF signaling pathway downstream of TLR3 and TLR4. These data illustrate that the up-regulation of costimulatory molecules and the adjuvanticity of LPS are direct outcome of TRIF-mediated signaling and not due to indirect effects of autocrine type I IFN production.

Results

TRIF-Mediated DC Maturation by LPS and Poly(I:C) Use Type I IFN-Independent and -Dependent Pathways, Respectively.

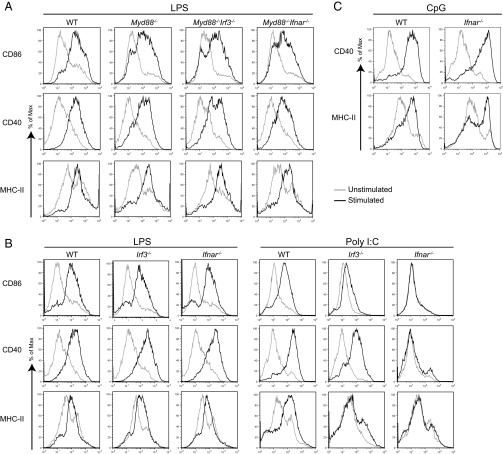

To understand the importance of type I IFNs in TRIF-mediated DC maturation, we generated MyD88–interferon α/β receptor (IFNAR) and –IRF3 double-knockout (DKO) mice. We stimulated bone marrow-derived DCs from these mice with LPS and analyzed DC maturation by measuring up-regulation of CD40, CD86, and MHC class II on CD11c-positive DCs. We found that MyD88–IFNAR DKO DCs had comparable expression of DC maturation markers to MyD88 KO, suggesting that IFNAR signaling is dispensable for TLR4–TRIF-driven DC maturation (Fig. 1A). We obtained similar results when we stimulated WT, IFNAR KO, and IRF3 KO DCs using TLR4 ligand LPS (Fig. 1B). However, when DCs were stimulated by using poly(I:C), a TLR3 ligand, IRF3 KO DCs were partially compromised in their ability to undergo maturation, but IFNAR KO DCs did not undergo any maturation (Fig. 1B). This result was also evident when we measured DC maturation at different time points after stimulation with poly(I:C) (Fig. S1). When we tested the importance of type I IFNs for DC maturation induced by other nucleic acid-sensing TLRs, we found that TLR9, which recognizes CpG DNA, activates IRF7, leading to IFN production, downstream of MyD88 (15), induced DC maturation independent of IFNAR signaling in DCs (Fig. 1C). Similarly, TLR7, which recognizes ssRNA, induced DC maturation independent of IFNAR signaling, suggesting that the dependency on type I IFN feedback for DC maturation was restricted to dsRNA recognition. We also found that the kinetics and magnitude of DC maturation was similar when DCs were stimulated by poly(I:C) or when exogenous type I IFN was directly added to DC cultures (Fig. S2).

Fig. 1.

TRIF-mediated DC maturation by LPS and poly(I:C) use IFN-independent and -dependent pathways, respectively. BMDCs of indicated genotypes were stimulated with LPS (A and B, 100 ng/mL), poly(I:C) (B, 20 µg/mL), or CpG (C, 1 µM) for 12 h and stained for surface expression of CD11c, CD86, CD40, and MHC-II. Histograms show CD11c+ cells expressing different maturation markers. Data are representative of two to five independent experiments.

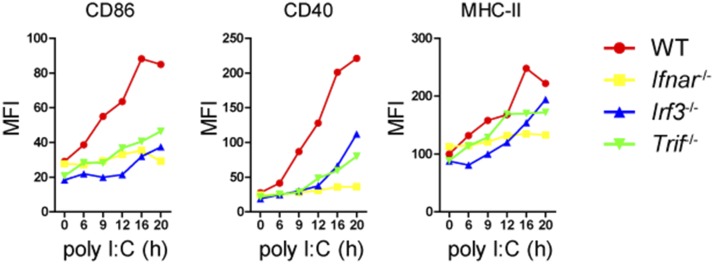

Fig. S1.

Poly(I:C) induces DC maturation in a type I IFN-dependent manner. BMDCs of indicated genotypes were stimulated with poly(I:C) (20 µg/mL) for indicated times and stained for surface expression of CD86, CD40, and MHC-II. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

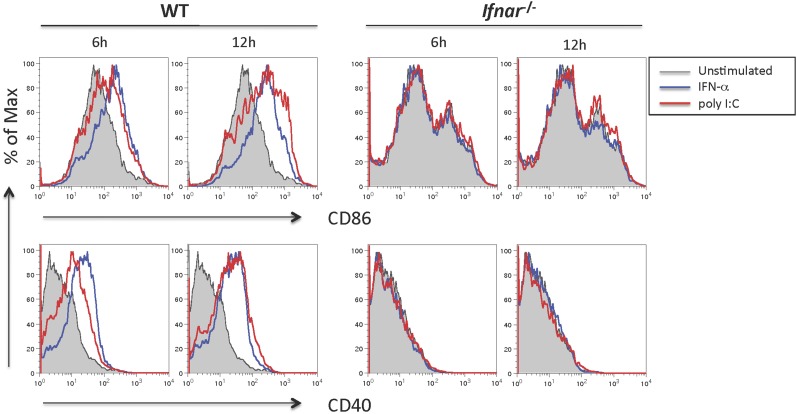

Fig. S2.

Poly(I:C) and type I IFNs induce similar extent of DC maturation. BMDCs of indicated genotypes were stimulated with poly(I:C) (20 µg/mL) or IFN-α (1,000 units/mL) for indicated times and stained using antibodies against CD11c, CD86, and CD40. Histograms of CD11c+ cells expressing CD86 and CD40 are shown here. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

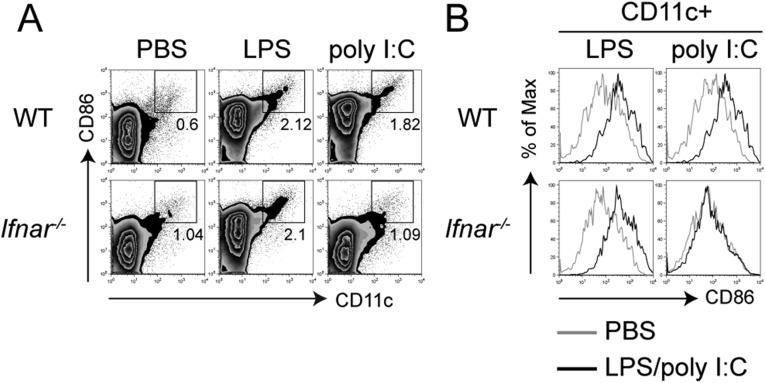

It has been reported that both LPS- and dsRNA-induced DC maturation is fully dependent on type I IFNs (8, 9). To validate our findings in vivo, we injected LPS or poly(I:C) subcutaneously into mice and measured DC maturation in the draining lymph nodes. Consistent with our in vitro data, we observed that LPS was able to induce comparable DC migration (Fig. S3A), as well as maturation (Fig. S3B) in both WT and IFNAR KO mice, whereas the ability of poly(I:C) to induce both DC migration to the draining lymph nodes and DC maturation in vivo was completely dependent on IFNAR signaling (Fig. S3). These results provide clear evidence for the differential dependence of LPS and poly(I:C) on type I IFNs to induce TRIF-dependent DC maturation in vivo.

Fig. S3.

In vivo DC maturation induced by LPS is independent of IFNAR signaling. WT or Ifnar−/− mice were injected in the fp with LPS (5 μg per fp) or poly(I:C) (25 μg per fp). After 16 h, cells from the popliteal lymph nodes were stained for CD11c and CD86. (A) Zebra plots show accumulation of CD11c+ CD86hi cells. (B) Histograms show the expression levels of CD86 by DCs (CD11c+). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

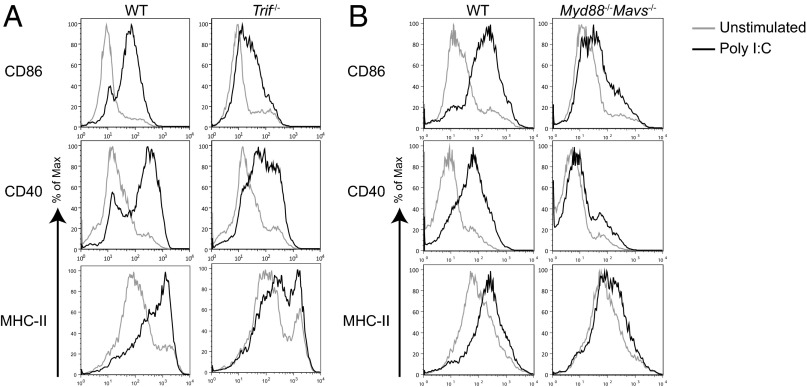

Optimal DC Maturation Induced by dsRNA Requires both TRIF- and MAVS-Dependent Signaling.

The poly(I:C) stimulation experiments described above are in agreement with previous findings that IFNAR signaling is important for dsRNA-mediated DC maturation (8, 9, 16). Type I IFN synthesis and secretion can be induced by dsRNA by activating either TLR3–TRIF signaling axis or RIG-I/MDA5–mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) signaling axis (17–21). To address the relative contribution of these pathways in DC maturation, we stimulated either TRIF KO bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) or MyD88–MAVS DKO BMDCs with poly(I:C) and measured up-regulation of CD86, CD40, and MHC class II. Absence of either MAVS or TRIF reduced the ability of the KO DCs to mature, suggesting that both TRIF and MAVS contributed to DC maturation (Fig. 2). It is also clear that the MAVS pathway had a larger contribution to the magnitude of DC maturation compared with the TRIF pathway (Fig. 2). This result could in part be due to the ability of the RIG-I–MAVS pathway to induce higher type I IFNs compared with TLR3–TRIF signaling axis (22), suggesting that type I IFN-positive feedback plays an important role in dsRNA-induced DC maturation.

Fig. 2.

Optimal DC maturation induced by dsRNA requires both TRIF- and MAVS-dependent signaling. WT, Trif−/− (A), or Myd88−/−Mavs−/− (B) BMDCs were stimulated with poly(I:C) (20 µg/mL) for 12 h and stained for surface expression of CD11c, CD86, CD40, and MHC-II. Histograms show maturation markers on CD11c+ population. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

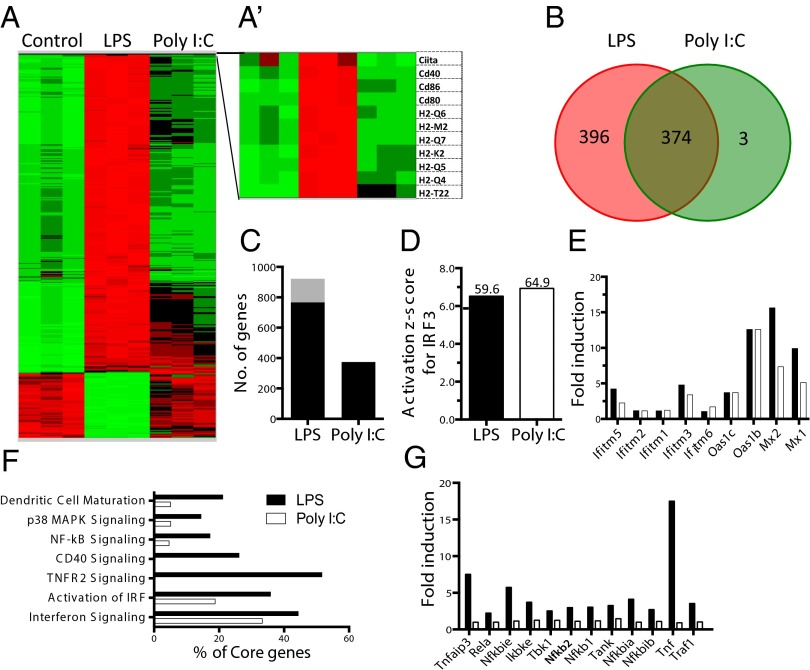

TLR3–TRIF Signaling Axis Fails to Directly Induce Genes Associated with DC Maturation.

To gain deeper insights into the mechanisms of DC maturation downstream of the TRIF signaling pathway, we decided to examine the global gene transcription of early genes, induced by TLR4 and TLR3 signaling restricted to TRIF. To eliminate the contribution of MAVS- and MyD88-dependent signaling, we performed the RNA sequencing in MyD88–MAVS DKO BMDCs after 3 h of stimulation with poly(I:C) and LPS, respectively. This approach allowed us to directly compare outcome of TRIF signaling downstream of TLR3 and TLR4 (Fig. 3A). Although we found that LPS was able to induce robust transcription of close to 800 genes (Fig. 3B), including genes associated with DC maturation (Fig. 3 A and A′), poly(I:C) could induce only a subset of those genes (Fig. 3 B and C). Both the TLR4– and TLR3–TRIF signaling axes were able to induce genes associated with IRF3 activation (Fig. 3D). TLR3–TRIF signaling was also capable of inducing several IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) (Fig. 3E), comparable to TLR4–TRIF signaling. Although activation of IRF and genes associated with type I IFN receptor signaling were similar in LPS and poly(I:C) stimulation (Fig. 3 E and F), pathway analysis revealed that TRIF signaling downstream of TLR3 was defective in inducing genes associated with NF-κB, TNFR2, p38MAP kinase signaling, and CD40 signaling (Fig. 3F). Absence of TNF-α induction and genes associated with TNFR2 signaling (Fig. 3G) by the TLR3–TRIF signaling axis is particularly important because it has been shown that TNF-α induced by TLR4–TRIF signaling axis is important for stable NF-κB activation (23). We therefore tested whether TNF-α induced by TLR4–TRIF signaling is important to induce DC maturation and found that it was dispensable for LPS-induced drive DC maturation via the TRIF pathway (Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

TRIF signaling induces robust transcription of genes associated with DC maturation downstream of TLR4, but not TLR3. BMDCs (CD11c+) from Myd88−/−Mavs−/− mice were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) or poly(I:C) (20 µg/mL) for 3 h, and RNA was prepared for RNA sequencing analysis. (A) Heat map represents the gene expression values of LPS or poly(I:C)-treated vs. untreated DCs. (A′) Heat map of selected genes critical for antigen presentation. (B) Venn diagram represents number of genes up-regulated more than twofold, uniquely or in both LPS (red) and poly(I:C) (green) compared with unstimulated DCs. (C) Total number of genes up-regulated (black) or down-regulated (gray), more than twofold, upon stimulation compared with unstimulated control. (D) Activation z-score for IRF3 calculated based on the IPA Upstream Regulator analysis. Overlap –logP values are shown above the bars. IRF3 in both conditions is predicted to be activated. (E) Fold induction of ISGs upon stimulation with LPS and poly(I:C). (F) Pathway analysis was performed on the genes induced >1.5-fold (P < 0.05). Each bar represents the percentage of core genes of the pathway induced upon stimulation based on ingenuity pathway analysis software. (G) Expression of core genes of TNFR2 signaling pathway upon stimulation with LPS and poly(I:C).

Fig. S4.

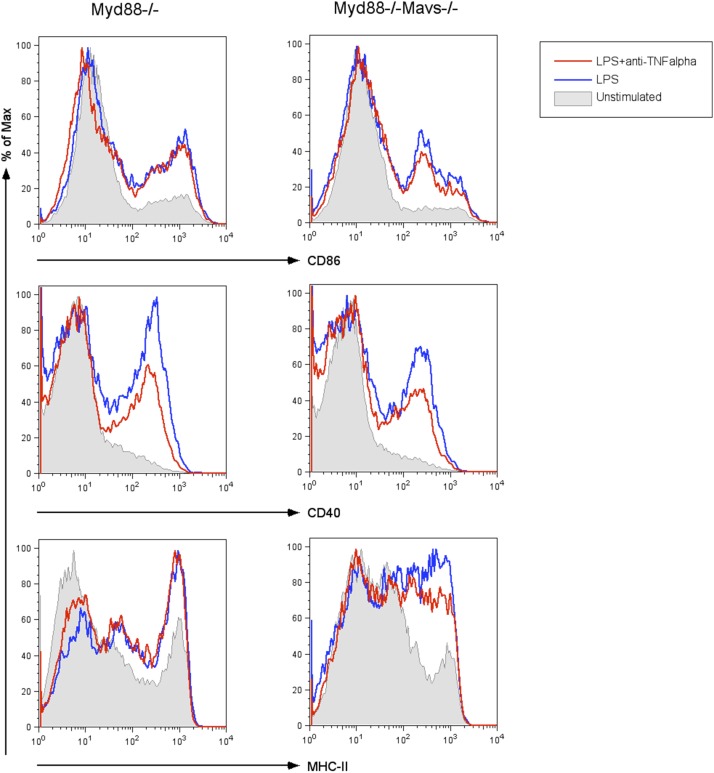

LPS-induced DC maturation via TLR4–TRIF signaling axis is independent of TNF-α. BMDCs of indicated genotypes were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of neutralizing anti–TNF-α antibody (10 μg/mL; BioLegend clone MP6-XT22). BMDCs are then stained for maturation markers CD86, CD40, and MHC-II, after 6–12 h of stimulation. Histograms shown maturation markers on CD11c+ population. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

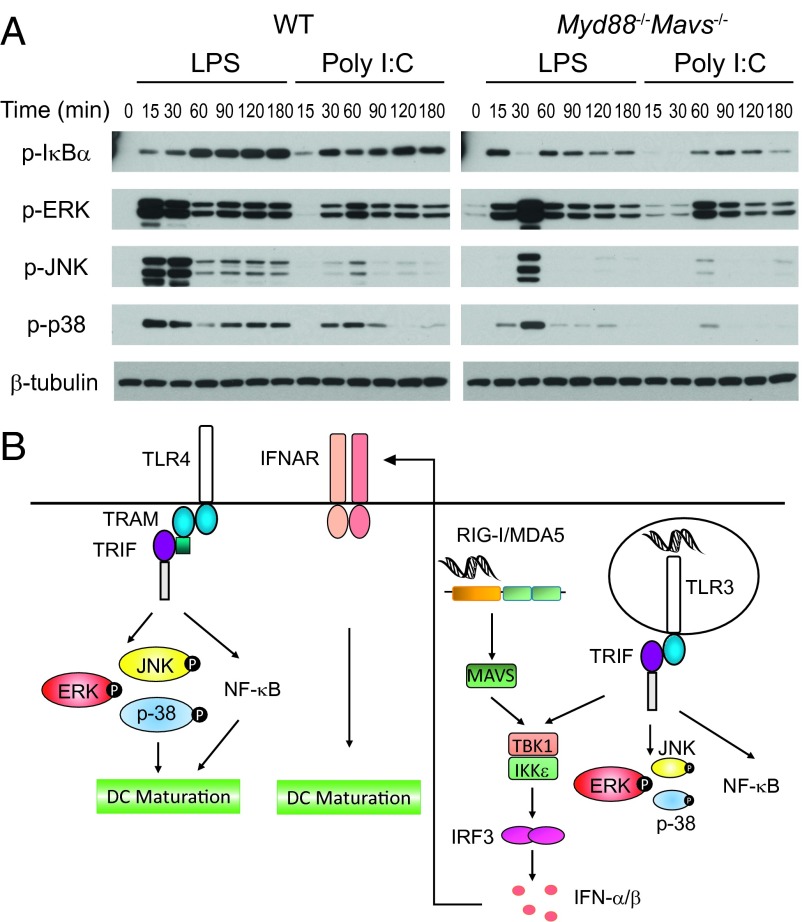

Differential Activation of MAP Kinases, JNK and P38, by the TRIF Signaling Pathway Downstream of TLR4 and TLR3.

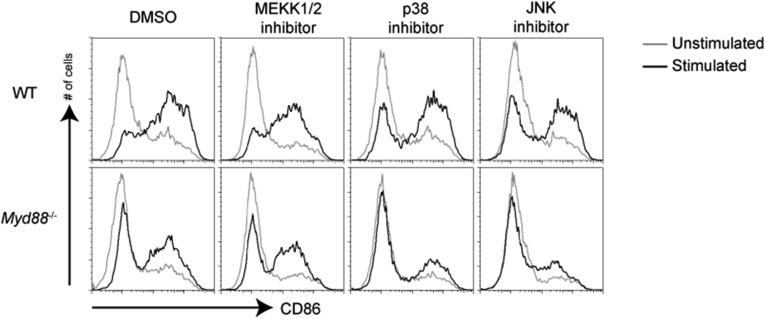

Our DC maturation and gene expression data above prompted us to examine early upstream signaling events after TRIF signaling downstream of TLR3 and TLR4. Although NF-κB and ERK activation by poly(I:C) was delayed compared with LPS, in MyD88–MAVS DKO macrophages, there was a striking deficiency in activation of MAP kinases JNK and P38 (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that strong NF-κB and MAP kinases downstream of the TLR4–TRIF axis can directly induce transcription of genes necessary for DC maturation, whereas dsRNA recognition pathways depend on type I IFN–IFNAR signaling axis to achieve DC maturation (Fig. 4B). Based on the above results, we predicted that, in the absence of p38 and JNK activation, TRIF-mediated signaling downstream of TLR4 would no longer be able to induce DC maturation. To test this hypothesis directly, we performed DC maturation experiments in the presence of MAP kinase inhibitors. Consistent with the above experiments, we saw that LPS-mediated maturation of MyD88-deficient DCs was abrogated by both p38 and JNK inhibitors, but not by a MEKK1/2 inhibitor (Fig. S5) that functions to inhibit MEKK1/2, which has been shown to control ERK activation (24). Although there could be potential off-target effects of these inhibitors, these data are consistent with differential ability of TLR4 and TLR3 to induce MAP kinase activation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

TRIF signaling pathway downstream of TLR4 induces stronger p38 and JNK activation compared with TLR3. (A) WT or Myd88−/−Mavs−/− BMDMs were stimulated with LPS or poly(I:C) for indicated times. Phosphorylation of IκBα, ERK, JNK, and p38 were analyzed by Western blot. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Schematic representation of signaling molecules involved in DC maturation downstream of TLR4, TLR3, and RIG-I/MDA5. Although TLR4–TRIF signaling can directly induce DC maturation, TLR3–TRIF cooperates with MDA5/RIG-I–MAVS signaling pathway to induce DC maturation through type I IFN feedback. Even though TLR4-TRIF axis induces type I IFNs (not drawn in the schematic), DC maturation after LPS stimulation is independent of IFN–IFNAR signaling.

Fig. S5.

JNK and p38 inhibition blocks MyD88-independent maturation induced by LPS. WT or Myd88−/− DCs were pretreated for 1 h with inhibitors for MEKK1/2, p38, or JNK and then stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 12 h. Surface expression of CD86 on CD11c+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Adjuvanticity of LPS Is Not Dependent on IFNAR Signaling.

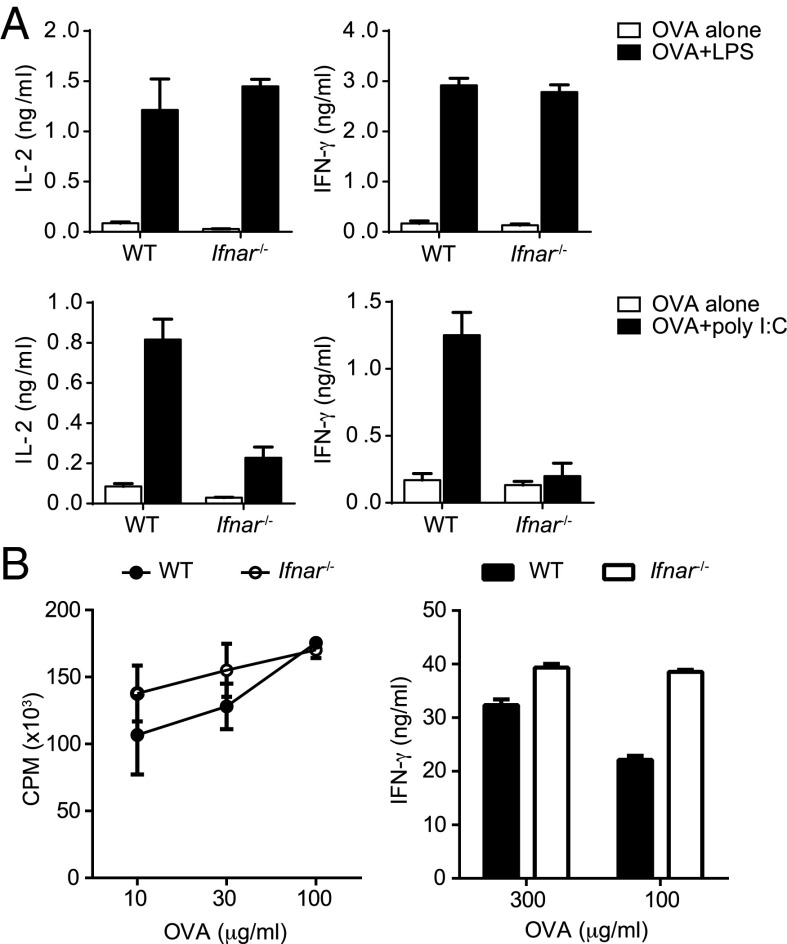

There is very good evidence that poly(I:C)-mediated activation T- and B-cell responses in vivo is completely dependent on type I IFNs and IFNAR signaling (8, 25), and our data support these findings because DC maturation is completely abrogated in the absence of IFNAR signaling. However, because our data demonstrate that LPS can induce DC maturation in the absence of IFNAR signaling, we decided to test the role of IFNAR signaling in LPS-mediated T-cell activation. We primed OT-II T cells in vitro using WT and IFNAR KO DCs and observed that LPS induced comparable IL-2 secretion by activated T cells, irrespective of the source of the DCs (Fig. 5A). Consistent with previous studies (8), poly(I:C)-stimulated IFNAR KO DCs were unable to prime T cells (Fig. 5A). We also found that IFNAR signaling in DCs was necessary for poly(I:C), but dispensable for LPS to instruct Th1 commitment in vitro (Fig. 5A). It has been demonstrated that IFNAR signaling is important for T-cell activation in vivo, when poly(I:C) was used as the adjuvant (8). However, we were more interested in understanding whether IFNAR signaling is important for the adjuvant effects of LPS in vivo and examined CD4 T-cell priming in IFNAR-deficient mice. We found that TLR4 activation in vivo resulted in comparable CD4 T-cell priming in both WT and IFNAR-deficient mice (Fig. 5B). Additionally, the primed CD4 T cells were also able to differentiate and commit to a Th1 lineage in the absence of IFNAR signaling. These results clearly establish that the ability of TLR4 to drive DC maturation in vivo (Fig. S3A), and subsequent activation of the adaptive CD4 T-cell responses is completely independent of type I IFNs.

Fig. 5.

The ability of LPS to induce T-cell priming is independent of IFNAR signaling. (A) Purified OT-II T cells were cultured with WT or Ifnar−/− BMDCs in the presence of OVA and LPS (100 ng/mL) or poly(I:C) (20 µg/mL) for 3 d. IL-2 or IFN-γ in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. (B) WT or Ifnar−/− mice were immunized in the foot pad (fp) with OVA (25 μg per fp) and LPS (2.5 μg per fp) emulsified in IFA. Draining lymph nodes were harvested on day 7 after immunization, and purified CD4 T cells were restimulated in the presence of Tlr2−/−Tlr4−/− B cells as APCs and titrating doses of OVA for 72 h. Proliferation of CD4 T cells was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation. IFN-γ concentrations in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

DC maturation is a critical first step in priming and differentiation of antigen-specific naïve T cells (26). DC maturation can be induced by a variety of ligands that activate different classes of PRRs (27). Two TLR ligands in particular have been of great interest because of their clinical use. Poly(I:C), a mimic of dsRNA that activates TLR3, has been used for treatment of cancer due it its ability to induce type I IFNs (28–31). In addition, derivatives of LPS that specifically activate the TRIF pathway of signaling downstream of TLR4 are being considered as vaccine adjuvants (10, 13). Earlier studies have found that the autocrine IFNAR signaling is important for DC maturation by poly(I:C) to induce CD4 T-cell priming and Th1 differentiation (8). It has also been proposed that the DC maturation induced by LPS via TLR4 is also dependent on IFNAR signaling (9). In this study, we carefully examined the need of IFNAR signaling for DC maturation downstream of TLR4– and TLR3–TRIF signaling axes and discovered that, although dsRNA-mediated DC maturation is dependent on IFNAR signaling, TLR4–TRIF-mediated DC maturation is completely independent of both type I IFN production and IFNAR signaling.

Both LPS and poly(I:C) have the ability to induce maturation of MyD88-deficient DCs (21, 32). Although the MyD88-dependent signaling pathway downstream of TLR4 is important for induction of most proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-12, TNF-α, etc., the MyD88-independent pathway or the TRIF-dependent pathway of signaling is responsible for activation of IRF3 and subsequent transcription of IFN-β and -α4 (21). Evidence for utilization of IFN-α/β for DC maturation and subsequent induction of adaptive immunity by dsRNA has been presented before (16–18). Our studies establish that dependency on type I IFNAR signaling to induce DC maturation is restricted only to dsRNA.

The obvious question is how and why the TRIF signaling pathway downstream of TLR4 and TLR3 are different. It has become apparent that both TLR4 and TLR3 engage TRIF from an endosomal compartment (33, 34). Direct comparison of signaling induced by LPS and poly(I:C) is not very informative because of participation of MyD88-mediated and RIG-I–mediated signaling pathways, respectively. The MyD88–MAVS DKO mouse allowed us to compare gene expression, as well as signaling outcomes, downstream of TRIF in response to LPS and poly(I:C). Pathway analysis of RNA sequencing data from LPS- or poly(I:C)-stimulated MyD88–MAVS DKO BMDCs provides enormous distinctions between the two groups. TLR3–TRIF signaling axis, although capable of inducing ISGs, is unable to activate genes that are dependent on NF-κB and MAP kinases. Strikingly, TRIF also fails to robustly activate MAP kinases JNK and P38, downstream of TLR3 compared with their activation downstream of TLR4. Inhibition of p38 and JNK, but not ERK, led to reduction in the ability of LPS to induce TRIF-dependent DC maturation, suggesting that activation of these MAP kinases is critical for TLR4–TRIF signaling to induce DC maturation. Failure of poly(I:C) to robustly induce MAP kinase activation is reflected by its inability to induce direct DC maturation. One possible explanation for lack of robust MAP kinase activation downstream of TLR3 could be differential use of TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM) for signaling. It would be then possible to predict that altering the C-terminal domain of TLR3 to engage TRAM would make it behave similar to TLR4 and induce robust NF-κB and MAP kinase signaling and type I IFN-independent DC maturation.

We finally evaluated the ability of LPS to induce T-cell activation and differentiation in vivo in the absence of type I IFN signaling. This investigation is important because induction of CD4 Th1 immunity when poly(I:C) is used as an adjuvant in vivo is critically dependent on type I IFNs (8). Another study demonstrated that LPS-induced DC maturation and its adjuvanticity were also dependent on type I IFNAR-signaling–induced DC maturation (9). We found no defect in the ability of LPS to induce DC migration and maturation in IFNAR KO mice. Consistently, LPS was able to induce robust activation and differentiation of antigen-specific Th1 cells in both WT and IFNAR-deficient mice. These results are clearly different from the earlier study, in which LPS-induced DC maturation was completely abrogated in IFNAR-deficient mice (9). Our experiments clearly demonstrate that earlier conclusions on the role of type I IFNs in regulating DC maturation and adaptive immune responses need to be revisited to highlight the differences between LPS and dsRNA mediated signaling pathways.

Together, our data demonstrate that TRIF signaling pathway has differential outcomes downstream of TLR4 and TLR3 and that there is a restricted role for type I IFNs in regulating DC activation and T-cell differentiation in vivo. As we move forward with designing adjuvants for human use, it will be important to understand the ability of PRR ligands to directly activate DCs themselves or indirectly through induction of cytokines such as type I IFNs as that might affect the specificity of the response. This study provides important insights that would need to be considered in future design and use of vaccine adjuvants that target TRIF pathway of signaling.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Myd88−/−, Myd88−/−Ifnar−/−, Myd88−/−Irf3−/−, Myd88−/−MAVS−/−, Trif−/−, Ifnar−/−, Irf3−/−, OT-II, and Tlr2−/−Tlr4−/− mice were bred and maintained at the animal facility of University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical Center. Control C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the UT Southwestern mouse breeding core facility. All mouse experiments were performed as per protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

DC–T-Cell Cocultures.

Purified OT-II T cells (4 × 105 per well) and BMDCs (8 × 104 per well) were cultured in 48-well plates with 3 μg/mL ovalbumin (OVA) for 3 d. Concentrations of IL-2 and IFN-γ in the supernatant were measured by using paired antibody ELISAs from BD Biosciences.

T-Cell Proliferation Assay.

Purified CD4 T cells (2 × 105) from draining the lymph nodes of immunized mice were cultured in flat-bottom 96-well plates with Tlr2−/−Tlr4−/− B cells (3 × 105) and titrating doses of antigen for 72–84 h. Tlr2−/−Tlr4−/− B cells were used to rule out any possibility of B-cell proliferation induced by potential contamination of LPS in OVA. Proliferation of T cells was determined by incorporation of 3H-thymidine for the last 12–16 h of the culture.

Western Blotting.

BMDMs were plated in six-well plates (1 × 106 per well) and stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) or poly(I:C) (20 μg/mL). Cells were lysed in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.6) containing 1% Triton X-100, 30 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 20 mM glycerol 2-phosphate, and Complete Protease Inhibitor Mixture (Roche). Lysates were resolved on 10% (wt/vol) SDS/PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and blotted with the relevant antibodies. Stained membranes were developed by using Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific) and exposed to film (Kodak).

RNA Sequencing and Analysis.

BMDCs were stimulated with LPS or poly(I:C) for 3 h. RNA was extracted by using the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen). Methods for data normalization and analysis are based on the use of “internal standards” (35–37), which was slightly modified to the needs of RNA sequencing data analysis. Functional analysis of identified genes was performed with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems). The two-step normalization procedure and the Associative analysis functions were implemented in MatLab (Mathworks) and are available from authors upon request. Functional analysis of identified genes was performed with IPA (Ingenuity Systems).

SI Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Reagents.

Anti-CD11c (clone N418), anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5), anti-CD86 (clone GL1), anti–TNF-α, and anti–MHC-II (clone M5/114.15.2) antibodies, and recombinant mouse IFN-α1 (catalog no. 751802) were purchased from Biolegend. Anti-CD16/CD32 (clone 2.4G2) and anti-CD40 (clone 1C10) antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences. Anti–phospho-IκBα, anti–phospho-ERK, anti–phospho-JNK, anti–phospho-p38, and anti–β-tubulin antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling. Inhibitors for MEKK1/2 (U0126), p38 (SB203580) and JNK (SP600125) were purchased from EMD Millipore, dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich), and used at a concentration of 2 µM in cell culture. Ultrapure LPS and poly(I:C) were purchased from Invivogen. CpG (ODN-1826) was purchased from Keck facility at Yale University. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% or 10% FCS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 μg/mL of streptomycin, and relevant growth factors.

BMDC and BMDM Culture.

Bone marrow was isolated from femurs and tibia and depleted of erythrocytes. For BMDCs, cells were cultured at 7.5 × 105 per mL in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% FCS and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Medium was replaced every 2 d. Cells were stimulated after 5 d of culture. For BMDMs, bone marrow cells were seeded in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and 30% conditioned medium from L929 cells in tissue culture dishes. The remaining suspension cells were harvested the next day and plated in non–tissue-culture-treated petri plates in the same medium. Adherent macrophages were harvested and replated after 4 d of culture.

Staining and Flow Cytometry.

Cells were blocked with anti-CD16/CD32 antibody for 10 min and stained with relevant antibodies for 30 min on ice. The stained cells were then washed and analyzed by using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed by using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

CD4 T-Cell Purification.

Single cell suspensions from the spleens and lymph nodes of OT-II mice, or draining lymph nodes of immunized mice, were incubated with anti-Class II (Y3JP), anti–Mac-1 (TIB-128), anti-CD8 (TIB-105 and -150), and anti-B220 (TIB-146 and -164) hybridoma supernatants. Antibody-labeled cells and B cells were depleted by using BioMag goat anti-mouse IgM (Polysciences), goat anti-mouse IgG, and goat anti-rat IgG beads (Qiagen). More than 95% of the remaining cells were CD4-positive.

Immunization.

Mice were immunized in the hind fp with 25 µg per fp of OVA and 2.5 µg per fp of LPS emulsified in IFA.

B-Cell Purification.

Splenocytes were incubated with anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8 (TIB-105 and -150), anti-Thy1 (Y19), and anti–Mac-1 (TIB-128) hybridoma supernatants on ice for 30 min, followed by rabbit complement (Cedarlane Laboratories) for 60 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed three times after complement lysis. More than 95% of the remaining cells were CD19-positive.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhijian (James) Chen from University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center for generous sharing of MyD88 mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) double-knockout (DKO) mice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI082265, AI115420, and AI113125 (to C.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. A.I. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1510760112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Regulation of phagosome maturation by signals from toll-like receptors. Science. 2004;304(5673):1014–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.1096158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West AP, et al. TLR signalling augments macrophage bactericidal activity through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2011;472(7344):476–480. doi: 10.1038/nature09973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(5):373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(10):987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stetson DB, Medzhitov R. Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity. 2006;25(3):373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longhi MP, et al. Dendritic cells require a systemic type I interferon response to mature and induce CD4+ Th1 immunity with poly IC as adjuvant. J Exp Med. 2009;206(7):1589–1602. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoebe K, et al. Upregulation of costimulatory molecules induced by lipopolysaccharide and double-stranded RNA occurs by Trif-dependent and Trif-independent pathways. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(12):1223–1229. doi: 10.1038/ni1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mata-Haro V, et al. The vaccine adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A as a TRIF-biased agonist of TLR4. Science. 2007;316(5831):1628–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1138963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAleer JP, Rossi RJ, Vella AT. Lipopolysaccharide potentiates effector T cell accumulation into nonlymphoid tissues through TRIF. J Immunol. 2009;182(9):5322–5330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhee EG, et al. TLR4 ligands augment antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocyte responses elicited by a viral vaccine vector. J Virol. 2010;84(19):10413–10419. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00928-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowen WS, et al. Selective TRIF-dependent signaling by a synthetic Toll-like receptor 4 agonist. Sci Signal. 2012;5(211):ra13. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casella CR, Mitchell TC. Putting endotoxin to work for us: Monophosphoryl lipid A as a safe and effective vaccine adjuvant. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(20):3231–3240. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawai T, et al. Interferon-alpha induction through Toll-like receptors involves a direct interaction of IRF7 with MyD88 and TRAF6. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(10):1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/ni1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honda K, et al. Selective contribution of IFN-alpha/beta signaling to the maturation of dendritic cells induced by double-stranded RNA or viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(19):10872–10877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934678100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413(6857):732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato H, et al. Length-dependent recognition of double-stranded ribonucleic acids by retinoic acid-inducible gene-I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5. J Exp Med. 2008;205(7):1601–1610. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Q, et al. The specific and essential role of MAVS in antiviral innate immune responses. Immunity. 2006;24(5):633–642. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar H, et al. Essential role of IPS-1 in innate immune responses against RNA viruses. J Exp Med. 2006;203(7):1795–1803. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto M, et al. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003;301(5633):640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar H, Koyama S, Ishii KJ, Kawai T, Akira S. Cutting edge: Cooperation of IPS-1- and TRIF-dependent pathways in poly IC-enhanced antibody production and cytotoxic T cell responses. J Immunol. 2008;180(2):683–687. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Covert MW, Leung TH, Gaston JE, Baltimore D. Achieving stability of lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kappaB activation. Science. 2005;309(5742):1854–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.1112304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Symons A, Beinke S, Ley SC. MAP kinase kinase kinases and innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2006;27(1):40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proietti E, et al. Type I IFN as a natural adjuvant for a protective immune response: Lessons from the influenza vaccine model. J Immunol. 2002;169(1):375–383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392(6673):245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Vliet SJ, den Dunnen J, Gringhuis SI, Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y. Innate signaling and regulation of dendritic cell immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19(4):435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krown SE, Kerr D, Stewart WE, 2nd, Field AK, Oettgen HF. Phase I trials of poly(I,C) complexes in advanced cancer. J Biol Response Mod. 1985;4(6):640–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lacour J, et al. Polyadenylic-polyuridylic acid as an adjuvant in resectable colorectal carcinoma: A 6 1/2 year follow-up analysis of a multicentric double blind randomized trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1992;18(6):599–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laplanche A, et al. Polyadenylic-polyuridylic acid plus locoregional radiotherapy versus chemotherapy with CMF in operable breast cancer: A 14 year follow-up analysis of a randomized trial of the Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte contre le Cancer (FNCLCC) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;64(2):189–191. doi: 10.1023/a:1006498121628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams M, et al. The rationale for combined chemo/immunotherapy using a Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) agonist and tumour-derived exosomes in advanced ovarian cancer. Vaccine. 2005;23(17-18):2374–2378. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Hoshino K, Akira S. Endotoxin-induced maturation of MyD88-deficient dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166(9):5688–5694. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kagan JC, et al. TRAM couples endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4 to the induction of interferon-beta. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(4):361–368. doi: 10.1038/ni1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnsen IB, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 associates with c-Src tyrosine kinase on endosomes to initiate antiviral signaling. EMBO J. 2006;25(14):3335–3346. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dozmorov I, Centola M. An associative analysis of gene expression array data. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(2):204–211. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dozmorov I, Lefkovits I. Internal standard-based analysis of microarray data. Part 1: Analysis of differential gene expressions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(19):6323–6339. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dozmorov MG, Guthridge JM, Hurst RE, Dozmorov IM. A comprehensive and universal method for assessing the performance of differential gene expression analyses. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e12657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]