Significance

The oxidation of water by photosystem II underpins autotrophic productivity in the Earth’s biosphere and represents a blueprint for developing sustainable, carbon-neutral technologies. Presently, the crucial catalytic steps leading to O2 formation remain obscure, although high-resolution kinetic and structural information has led to discussion of possible chemical intermediates. By genetically manipulating the inner surface polarity of a protein cavity holding a water cluster adjacent to the catalytic metal center, a previously unobserved intermediate is revealed. The results have implications for the understanding of the natural mechanism as well as the highly desirable biomimetic devices currently envisioned of solar energy production.

Keywords: photosynthesis, water oxidation, oxygen release kinetics, photosystem II, activation energy

Abstract

Photosynthetic water oxidation is catalyzed by the Mn4CaO5 cluster of photosystem II. Recent studies implicate an oxo bridge atom, O5, of the Mn4CaO5 cluster, as the “slowly exchanging” substrate water molecule. The D1-V185N mutant is in close vicinity of O5 and known to extend the lag phase and retard the O2 release phase (slow phase) in this critical last transition of water oxidation. The pH dependence, hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) isotope effect, and temperature dependence on the O2 release kinetics for this mutant were studied using time-resolved O2 polarography, and comparisons were made with WT and two mutants of the putative proton gate D1-D61. Both kinetic phases in V185N are independent of pH and buffer concentration and have weaker H/D kinetic isotope effects. Each phase is characterized by a parallel or even lower activation enthalpy but a less favorable activation entropy than the WT. The results indicate new rate-determining steps for both phases. It is concluded that the lag does not represent inhibition of proton release but rather, slowing of a previously unrecognized kinetic phase involving a structural rearrangement or tautomerism of the S3+ ground state as it approaches a configuration conducive to dioxygen formation. The parallel impacts on both the lag and O2 formation phases suggest a common origin for the defects surmised to be perturbations of the H-bond network and the water cluster adjacent to O5.

Oxygenic photosynthesis depends on the light-driven water-plastoquinone oxidoreductase, photosystem II (PSII), which catalyzes the complete oxidation of H2O molecules to O2. The electrons extracted from H2O oxidation are the reductant for autotrophic metabolism, and the liberated protons contribute to the transmembrane proton motive force powering ATP production (reviewed in refs. 1–4). The byproduct, O2, has transformed our Earth’s atmosphere and makes heterotrophic life in the biosphere possible. A metal cluster, the Mn4CaO5, functions as the catalytic site of H2O oxidation and is buried in a protein domain of PSII referred to as the H2O oxidation complex (WOC). The primary photochemical electron donor of the reaction center (RC) complex is a dimeric chlorophyll moiety designated P680 that is coordinated by the pseudosymmetrically arranged D1 and D2 polypeptides. Together, the D1/D2 heterodimer are responsible for the coordination of most of the photochemically active cofactors of the RC. Photoexcitation of P680 initiates transmembrane charge separation with the activated electron moving to plastoquinone species, QA and QB, on the acceptor side of the RC. The resultant electron hole functions as the powerful oxidant for the extraction of electrons from substrate H2O bound to the Mn4CaO5 (Fig. 1A). However, the oxidation of the Mn4CaO5 occurs through a redox active tyrosyl of the D1 protein, D1-Tyr161 (YZ), located between P680 and the metal cluster. Thus, YZ functions as a secondary donor to the photochemical RC and the primary oxidant of the Mn4CaO5. Oxidation of YZ creates a neutral tyrosine radical because of a coupled proton transfer from the tyrosine to the nearby D1-His190, which is H-bonded to YZ. Accordingly, YZ oxidation leads to the formation of the positive charged pair His190+ by moving the proton within the H bond (5–9). According to the “proton rocking” mechanism, this proton returns to YZ on its reduction by the Mn4CaO5 cluster. The transient formation of the positive charge in the immediate vicinity of the cluster may have a critical electrostatic effect in promoting proton transfer and/or H-bond rearrangements elsewhere in the WOC.

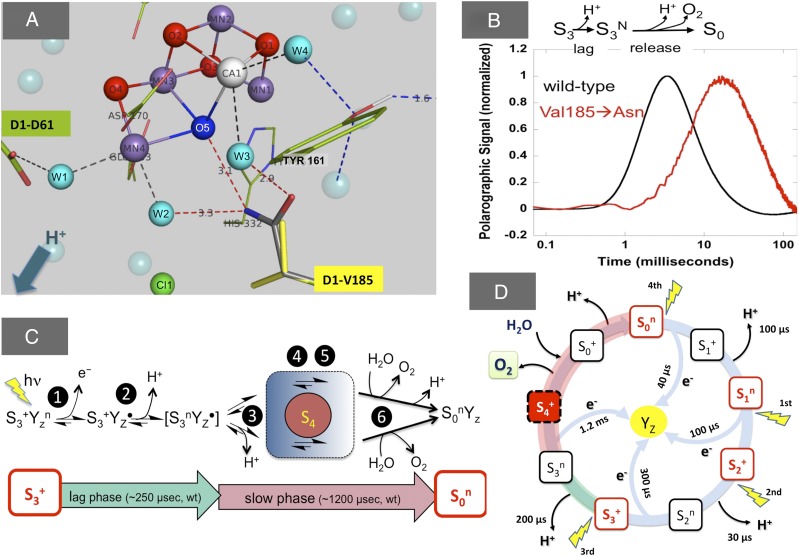

Fig. 1.

(A) Mutations constructed in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 to D1 residue Val185 (rendered with yellow sticks) and Val185Asn substitution showing one possible configuration of the amide extending into the water cavity H bonding (red dashes) with the water molecules (cyan spheres) close to oxo bridge atom, O5 (bright blue), of the Mn4CaO5 cluster. Rudimentary analysis of crystal structure with PyMol indicates multiple rotamer configurations of the asparagine side chain without steric clashes, except displacements of the water molecules. The amide moiety introduces four potential H-bonding sites: two acceptor (-C = O) and two donor (-NH2) sites. Other energetically feasible rotamers may interact with the essential chloride anion cofactor (Cl1; green). (B) A large retardation of O2 release kinetics during was found in D1-V185N mutant (23), similar to D1-D61N and D1-D61A mutants (16, 20, 32). (C) Proposed intermediates after excitation of PSII in the state. Step 1: oxidation of YZ by P680+ forming . Step 2: loss of the proton forming . Step 3: reduction of /oxidation of the Mn cluster. Step 4: reduction of the cluster by oxidation of substrate. Step 5: O-O bond formation. Step 6: H2O binding and O2 release. The S4 state. (D) Representation of the entire S-state cycle, emphasizing the alternating electron and proton removal from the cluster. Classic Kok S-states correspond to those shown in red outline.

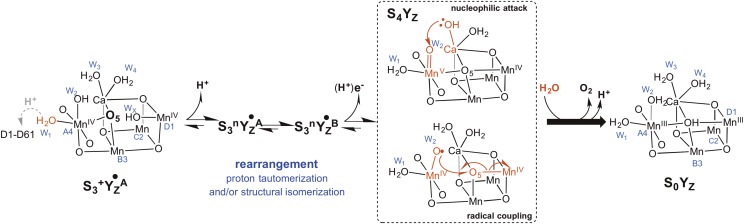

Charge separation in the photochemical RC is a single-electron process, but it must be coupled with the four-electron oxidation: 2H2O→O2 + 4e− + 4H+. PSII solves the valence mismatch problem by accumulating oxidizing equivalents within the Mn4CaO5 cluster as deduced from early observations of period 4 oscillatory O2 release under flash illumination (10) that led to the formulation of a model invoking storage (S) states consisting as four semistable states produced by flash illumination (S0, S1, S2, and S3) and a transient state (S4) (11). O2 formation and release occurs during the transition, with a hypothetical intermediate S4 that forms on oxidation of S3 followed by the formation of O2 and the reduction of Mn4CaO5 by substrate H2O (11). Proton release to the lumen of the thylakoids occurs at specific points during the catalytic cycle (reviewed in ref. 12). Deprotonation minimizes the accumulation of positive charge on the Mn4CaO5 cluster and provides a “redox leveling” effect that ensures that successive withdrawals of electrons from the metal center remain energetically feasible through all of the S states of the catalytic cycle. Detailed analyses have revealed an alternation of electron transfer and proton transfer events (13, 14), leading to the reformulation for the cycle, where the indices n and + refer to the electrostatically neutral and positive states, respectively, relative to the S1n state (Fig. 1D). Because of the paucity of identified reaction intermediates in the transition, the mechanism of water oxidation by PSII still remains elusive. In this step, the O-O bond is formed, O2 and two protons are released, and at one substrate, water binds to the Mn4CaO5 cluster. Possible intermediates in this poorly understood final stage are depicted in Fig. 1C. A 30- to 250-μs lag phase preceding the release of O2 and the reduction of the Mn4CaO5 has been assigned to the release of a proton (step 2 in Fig. 1C) (5, 13–19). Step 3 in Fig. 1C refers to the oxidation of the Mn cluster by and has been observed to initiate 250 μs after the excitation of the S3+ ground state (18). The initiation of step 3 marks the end of the lag phase and leads to formation of the transient and chemically undefined S4 state. It should be pointed out that the lag phase is multiphasic (13), and thus, step 2 and perhaps, step 3 in Fig. 1C consist of more than one process—a point that is significant to the experiments described below. Mutational analysis (16, 20–23) and substitution of the Ca2+ and Cl− cofactors (24) result in a slowdowns of the transition, including an increase in the duration of the lag phase. These slowdowns in the lag phase could be attributed to an impairment of proton release to the solvent bulk, but as shown in this work, they may be better ascribed to a slowdown of some other molecular rearrangement that precedes the release of O2 and becomes rate-determining in the mutants studied here.

As shown in Fig. 1A, the Mn4CaO5 cluster resembles a distorted chair, where four oxygen atoms link the three Mn atoms and one Ca atom together by μ-oxo bridges to form the cuboidal unit. The fourth dangling Mn (Mn4) is located outside the cube and linked to one of the Mn corners (Mn3) by a μ-oxo bridge ligation (O4) and a fifth bridging μ-oxo (O5) to the Ca (25, 26). The bonding arrangement of O5 is proposed to be flexible and consequently, provides flexibility to the entire structure (27): The S2+ state may exist in two nearly isoenergetic configurations as suggested by the alternative EPR signals (27): a low-spin open cube, where O5 is bonded to Mn4 and not Mn1 as depicted in Fig. 1A, or the high-spin, closed cube state, where O5 is bonded to Mn1 and not Mn4. The slowly exchanging substrate water is assigned to O5, and the envisioned structural flexibility would account for the unexpectedly fast rate of exchange of O5 with external water (28). The Mn4CaO5 cluster is ligated to the D1 and CP43 subunits of PSII by six carboxylate ligands and one histidine. Other than the first sphere ligands, the geometry of the Mn4CaO5 cluster is also maintained by second sphere amino acids and a number of water molecules situated in the cavity of the catalytic site. Water molecules not only are substrate but also, participate in a reticulated H-bond network (HBN), interacting the first and second sphere ligands of the Mn4CaO5 cluster and forming paths connecting the cluster with the external aqueous phase of the thylakoid lumen (reviewed in ref. 29). This HBN includes the participation of second sphere ligand D1-Asp61, which may be the initial residue of a main proton egress pathway through its interaction with a water molecule designated W1 (30). Recently, point mutations were generated to interfere with the water molecules surrounding the Mn4CaO5 cluster by altering the shape and polarity of the protein surface facing the aqueous pockets (23). Mutations of a valine, D1-V185, exhibit the most interesting phenotypes. D1-Val185 is part of the broad channel, because it passes the Mn4CaO5 cluster and is in the close vicinity of O5 (31) (Fig. 1A). The D1-V185N mutation has a strong effect on the oxygen evolution. In contrast to the short lag (<250 µs) and short half-lifetime of 1−2 ms of the transition in the WT, the mutant has a drastically prolonged lag phase followed by a drastically slowed rate of oxygen release (Fig. 1B; see below), which opens a new window for the study of the reaction pathway during the dioxygen-forming stage of the catalytic cycle. Here, we carefully characterized the pH and temperature dependence and deuterium isotope effect on the O2 release kinetics of the D1-V185N mutant and made comparison with the WT and D1-D61N and D1-D61A mutants (16, 20, 32). The goal is to gain insight into the nature of the elusive intermediates formed during the lag and O2 release phases of the transition.

Results

The O2 release kinetics associated with the S3 to S0 transition can be monitored by measuring polarographic transients with a bare platinum electrode resulting from flashes given to a thin film of thylakoid membranes centrifugally deposited on the platinum surface. The bare platinum electrode allows very high time resolution measurements of O2 evolution by PSII under flashing light. The polarographic transient generated after flash illumination features an initial lag phase followed by a sigmoidal rise to a maximum value (slow phase) and a slow decay toward the preflash level. Quantitative description of the kinetics of O2 evolution was facilitated by implementation of a physical model (16, 33) that takes into account the production of O2 from PSII, the diffusive processes governing the concentration of O2 at the platinum electrode surface, and the electrode reaction consuming O2 at that surface. Because the occurrence of a lag phase before the onset of the rise of the O2 signal has been observed, most notably in the mutant, the O2 production terms of the kinetic model include an intermediate, designated I for the sake of generality (Scheme 1):

The model used for fitting the O2 release curves divides the volume of the deposited PSII sample and the buffer above it into layers. The simulated lines and parameters of the O2 release signals are indicated in Fig. S1 and Table S1. The signal from the oxygen electrode is proportional to the O2 concentration in the lowest layer in contact with the surface of the electrode. Eq. 1 is used to calculate the concentration of O2 in the bottom layer (x = 0) of the thylakoid membrane sample at each time point t. Rel refers to the rate constant of O2 consumed by the electrode. D represents the value of the O2 diffusion constant. The delay in the rise of the electrode signal is described by the rate constant k1 and an additional time offset (toffset in Eq. 1); toffset and k1 (sigmoidal rise) are used to simulate the overall delay resulting from both the O2 reduction reaction at the electrode and delayed O2 production in PSII (additional discussion of the O2 release model is in SI Materials and Methods). The overall delay is referred to as lag phase or lag hereafter:

| [1] |

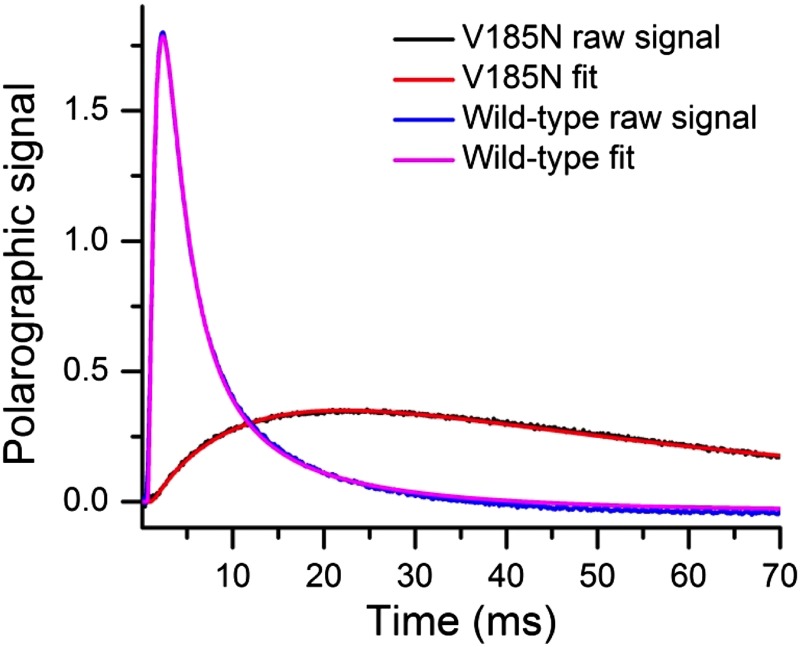

Fig. S1.

Raw data and simulated data of oxygen release kinetics of WT and V185N thylakoid membranes. The O2 release transients of WT (blue) and the D1-V185N mutant (black) were measured at room temperature (27 °C and pH 6.5). The simulated lines of the WT (pink) and the D1-V185N mutant (red) were obtained by simulation based on the physical model that takes into account oxygen diffusion and consumption of the electrode system used for detection of the oxygen release kinetics. The fits used a custom-made program (16), which calculates two rise constants for the release of O2 as well as the thickness of the thylakoid membrane layer, diffusion processes, and consumption of O2 at the surface of the electrode. Simulation parameters were optimized by means of a least squares fit using the electrode reaction parameters for WT and V185N data.

Table S1.

Simulation parameters of the O2 transients shown in Fig. S1

| Parameter | WT | D1-V185N |

| Lag phase τlag (ms) | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| Slow phase τ2 (ms) | 1.1 | 29.3 |

| PSII layer (μm) | 9.5 | 11.0 |

| Electrode constant RElec (ms−1) | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| Data range for fitting (ms) | ∼0.4–70 | ∼0.9–150 |

| R2 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

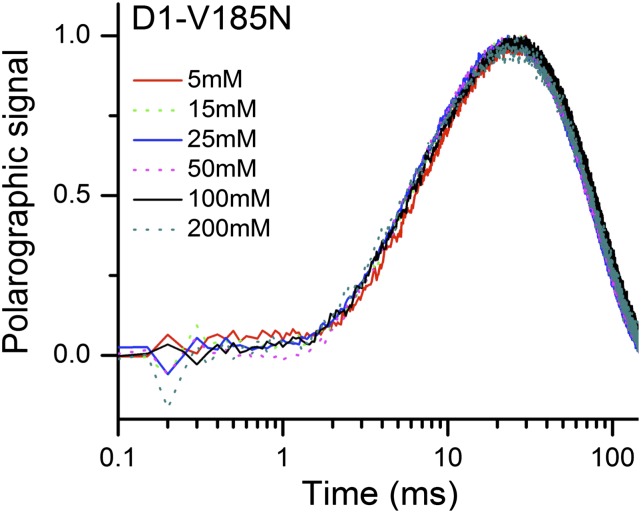

pH Dependence of O2 Release Kinetics on .

It was recently shown that the D1-V185N mutant (23), similar to D1-D61 mutations (D61N and D61A), displays a large retardation of the kinetics of O2 release during the (16, 20, 32). Compared with the WT, D1-V185N exhibits an extension of lag phase and a slowdown of the slow phase (Figs. 1 and 2). The lag phase is of particular interest, because it has been ascribed to a proton release event on formation of in the WT PSII (step 2 in Fig. 1C) (5–9). In spinach WT preparations, the lag phase is extended at low pH and by D2O substitution, indicating a deprotonation of the Mn complex after formation but before the onset of electron transfer and O-O bond formation (13, 14, 19). To identify the nature of the unusually long period of lag in the D1-V185N, the kinetics of O2 evolution were recorded under a range of pH conditions (Fig. 2). The pH effect was investigated at room temperature (27 °C) and for the WT, lower temperature (6 °C). At room temperature, the lag phase of the WT is too fast to be sufficiently resolved for analysis of its pH dependence in our polarographic system (Fig. S2). By lowering temperature, the period of lag in the WT is significantly extended, allowing better discrimination of the differences in the lag phase as a function of pH. We observed a pronounced pH dependence of the lag-phase duration in the WT at 6 °C (Fig. 2A). The effects of pH on time constants of the lag and slow phases, which were determined by curve fitting of O2 release transients at different pH regimes, are summarized in Table 1 (details of curve fitting are in SI Materials and Methods and ref. 16). It shows that the period of lag of the WT detected at low temperature (6 °C) increases from 1.8 to 2.7 ms by lowering pH from 7.5 to 5.0. This strong pH dependence of the lag is consistent with earlier observations with spinach preparations indicating that the higher [H+] creates a proton “back-pressure,” limiting the rate of a requisite deprotonation (13, 14, 19). In contrast, the lag-phase duration of 1.4 ms in D1-V185N is pH-independent and much longer than the WT as shown in Fig. 2 and Table 1. Additional evidence for the pH independence of the mutant is the absence of a buffer concentration effect on the kinetics (Fig. S3). Taken together, the results indicate that the lag phase of D1-V185N is not rate limited by proton transfer processes and that there is no H+ product back-pressure effect on the lag phase in D1-V185N in contrast to the WT. Of course, rate-limiting internal proton transfer that is not affected by external pH cannot be ruled out.

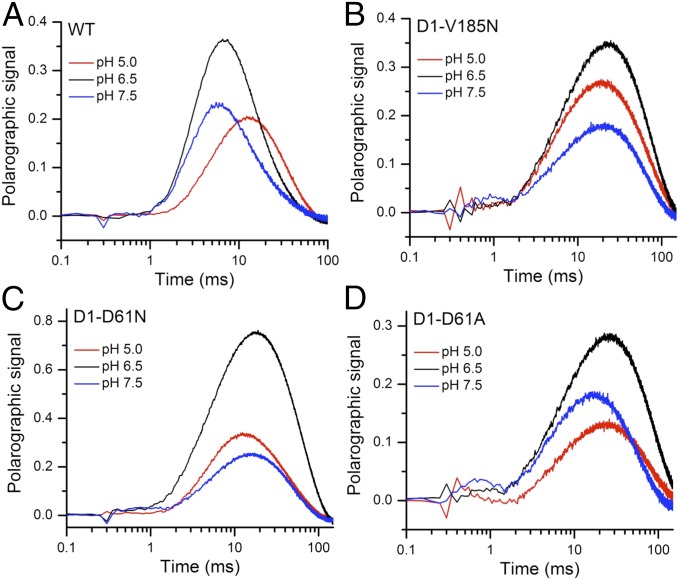

Fig. 2.

O2 release kinetics of (A) WT, (B) D1-V185N, (C) D1-D61N, and (D) D1-D61A thylakoid membranes measured at pH 5.0 (red), 6.5 (black), and 7.5 (blue). The O2 release transients shown are the averages of six trials. Each trial is the averaged polarographic signal resulting from 240 successive flashes from a red light-emitting diode, excluding the first 3 initial flashes. The measurements were taken at (A) 6 °C and (B–D) 27 °C.

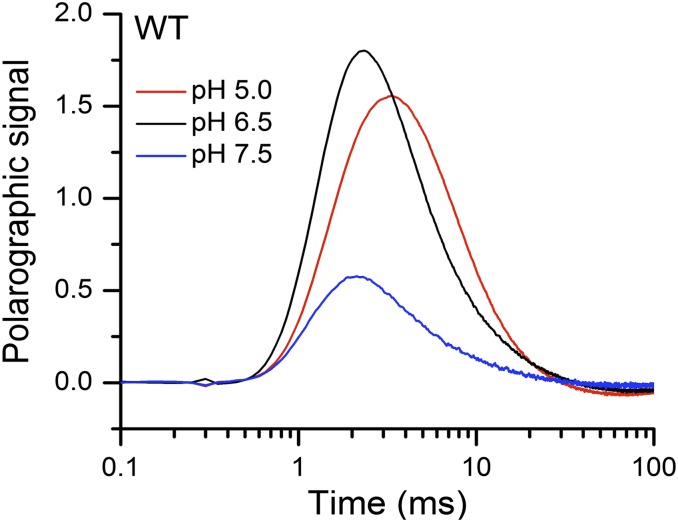

Fig. S2.

O2 release kinetics of WT thylakoid membranes measured at pH 5.0 (red), pH 6.5 (black), and pH 7.5 (blue). The O2 release transients shown are the averages of six trials. For each trial, the transient obtained is the averaged polarographic signal induced by a series of 240 flashes from a red light-emitting diode, excluding the first 3 initial flashes. The measurements were taken at 27 °C.

Table 1.

Time constants for the release of O2 at different pH

| Sample | Temperature (°C) | Lag phase tlag (ms) | Slow phase tslow (ms) | ||||

| pH 5.0 | pH 6.5 | pH 7.5 | pH 5.0 | pH 6.5 | pH 7.5 | ||

| WT | 6 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 11.7 | 3.7 | 2.6 |

| WT | 27 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| V185N | 27 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 28.6 | 29.3 | 27.5 |

| D61A | 27 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 31.7 | 32.8 | 20.9 |

| D61N | 27 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 15.1 | 22.9 | 17.4 |

Time constants were estimated using fits of the data to the reaction–diffusion model defined by Scheme 1 and are detailed in ref. 16 and SI Materials and Methods.

Fig. S3.

Normalized O2 release kinetics of D1-V185N thylakoid membranes measured at pH 6.5 with a serious of concentration of MES-NaOH buffer. The O2 release transients shown are the averages of six trials. For each trial, the transient obtained is the averaged polarographic signal resulting from 240 flashes from a red light-emitting diode, excluding the first 3 initial flashes. The measurements were taken at 27 °C.

D1-D61 is a residue that is located at the beginning of a proposed proton exit pathway in PSII and proposed to facilitate proton release from WOC (Fig. 1A). To make a comparison with V185N, the pH dependence of lag phase in D1-D61N and D1-D61A mutants was also investigated. D1-D61N is a well-studied mutant that has been found to have long lag and slow O2 release kinetics similar to D1-V185N (20, 23, 32). The lag time in D1-D61N at pH 6.5 is 1.2 ms, which is shorter than the 1.4 ms of lag in D1-V185N. However, unlike the pH-independent lag of V185N, the lag of D61N became much longer at both high and low pH compared with pH 6.5 (Fig. 2C and Table 1) as observed previously (16). In contrast, the pH dependence of the lag phase in D61A has a similar trend as the WT, albeit that the lag is greatly extended in comparison. The different pH-dependent behavior of the lag phase between D61N and D61A suggests that the asparagine and alanine substitutions perturb the proton release mechanism differently. This difference may relate to the fact that the asparagine substitution retains both H-bond donor and acceptor functionality but lacks proton exchange capability. In contrast, the alanine substitution is incapable of offering polar interactions, but its smaller size may allow water to intercede at that location and provide a channel to communicate protons. Interestingly, similar pH dependence trends occur for the slow-phase kinetics (steps 3–6 in Fig. 1C) as with the lag phases for each of the PSII variants. For the WT, the slow phase, like the lag phase, has a strong pH dependence (Fig. 2A, Table 1, and Fig. S2), which is more clearly evident in the low-temperature (6 °C) experiment. In contrast, no pH dependence of slow phase is observed in D1-V185N as observed for the lag. The D1-D61N and D1-D61A mutants also exhibited pH dependencies that mirrored the pH effects on their lag phases: more alkaline pH values favored faster O2 kinetics for D1-D61A, whereas a nonlinear response was obtained for D1-D61N.

Hydrogen/Deuterium Isotope Effect on O2 Release Kinetics.

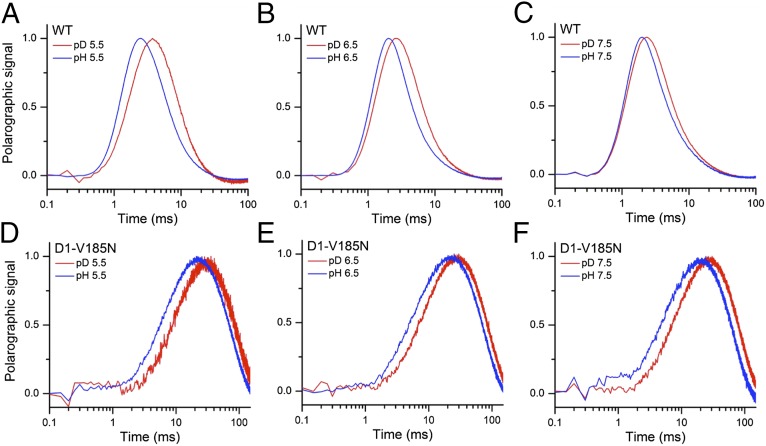

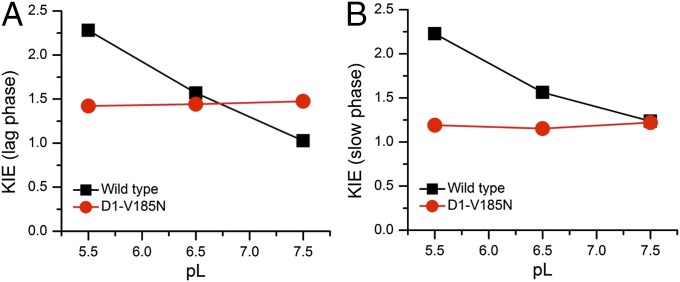

Fig. 3 compares the O2 transients in H2O and D2O at different pH (or pD) for the WT and D1-V185N. The pD was calculated as pDread + 0.4, where pDread is the pH meter reading for D2O solution. Unique molecular interpretations of kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) remain a difficult problem, but comparisons of KIEs in the mutant and the WT can offer clues regarding structure–function relationships. The lag-phase duration is found to be increased in D2O, and an overall slowdown of O2 release is observed at all tested pD values relative to its corresponding pH values in both the WT and D1-V185N mutant, consistent with previous polarographic analyses of the WT and D1-D61N mutant (16) and studies of other PSII preparations (ref. 13 and references therein). However, the pL (pH or pD) dependence of isotope effect in D1-V185N is different from that in the WT (Figs. 3 and 4). For WT, the KIEs on the lag phase and slow phases reveal similar profiles: highest at pL 5.5 and lowest at pL 7.5 (Fig. 4). It should be noted that caution needs to be taken when the KIE on the lag-phase duration is assessed, because the precision of the deconvolution based on a consecutive reaction scheme and the contribution from the electrode response are both critical for duration of lag phase. Nevertheless, the variation of the value does not call into question the pH dependence of the isotope effect on the lag. This pL dependence of the WT suggests that a titratable group(s) with a pKa < pH 6 needs to be deprotonated to accept rate-determining protons from the WOC and that the protonation of this group presents the higher KIE (∼2.4). At higher pH values, this group tends to its deprotonated state, and the correspondingly lower KIE likely reflects the switch of rate limitation by a different process (Fig. 4). Indeed, for pL 7.5, the deuterium KIE of the lag phase in the WT disappears so that another process, perhaps a chemical process or structural rearrangement, governs the lag period at higher pH. This KIE is also the case for the slow phase in the WT, where a chemical or structural rearrangement step governs the rate of the O2 release phase at higher pH. In contrast, both the lag and slow phases in D1-V185N have almost constant KIEs of ∼1.4 and ∼1.2, respectively, because pL is varied (Fig. 4). In principal, KIEs in this range can reflect proton transfer through water (34), but the absence of a pH dependence, as shown in the previous section, argues against this possibility, at least as far as it being a communication of the proton to the exterior of the protein. However, the rate of proton transfer through water is itself governed by rotational rearrangements of water, and this conclusion is the basis for the estimated KIE of 1.4 (34). Therefore, the observed KIEs for these kinetic phases in the mutant could more simply reflect rearrangements of water. This interpretation would be consistent with the analysis of the thermal activation parameters, indicating changes in the entropic term of the activation energy described below. Moreover, the fact that both the lag and slow phases have similar pH dependence trends and similarly changed KIE characteristics suggests that the lag and slow phases (step 2 and steps 3–6, respectively, in Fig. 1C) may have similarly perturbed mechanistic features.

Fig. 3.

O2 release kinetics of (A–C) WT and (D–F) D1-V185N thylakoid membranes measured in H2O (blue) and D2O (red) at pH (or pD) 5.5, 6.5, or 7.5. The O2 release transients shown are the averages of six trials. For each trial, the transient obtained is the averaged polarographic signal resulting from 240 successive flashes from a red light-emitting diode, excluding the first 3 initial flashes.

Fig. 4.

KIE of (A) the lag phase and (B) the slow phase as a function of pL (pH or pD) for WT (black square) and V185N (red circles).

Temperature Dependence of O2 Release Kinetics: Change of Rate-Determining Step During Dioxygen Formation in D1-Val185Asn.

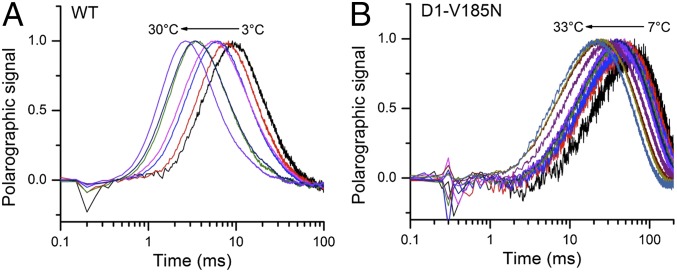

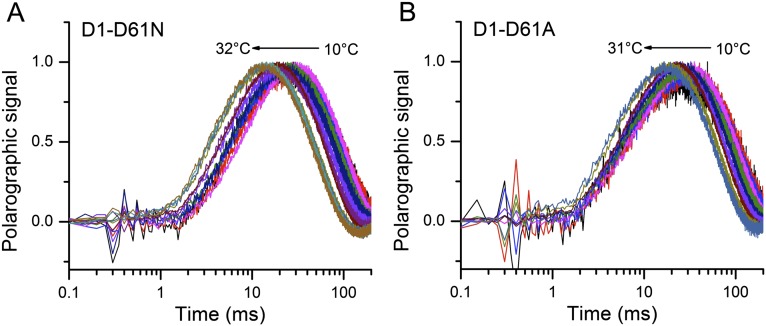

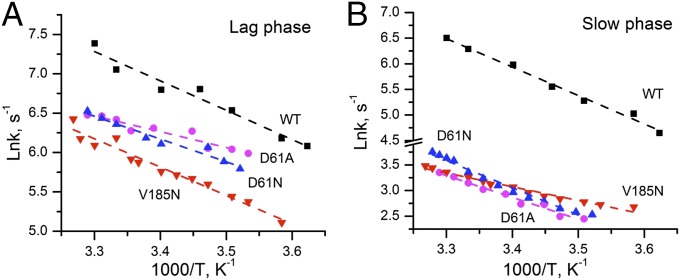

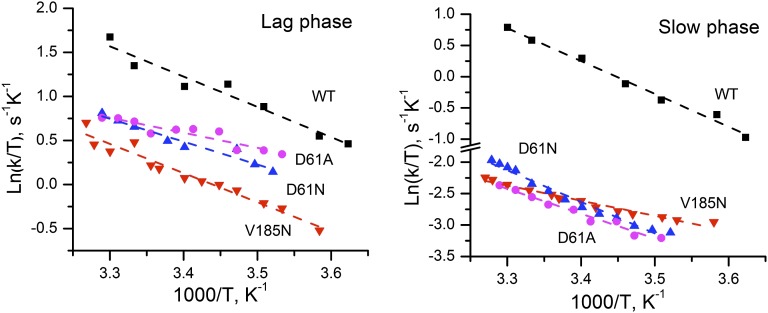

To evaluate the thermal activation characteristics of the transition in the mutants, the temperature dependence of the O2 release kinetics was studied. The polarographic transients were collected over a range of temperatures from 3 °C to 33 °C. Fig. 5A shows that the lag time and half-rise time of polarographic transient gradually increase as temperature falls in the WT and D1-V185N (Fig. S4 shows D61N and D61A mutants). Arrhenius plots of the lag phase yielded an activation energy (Ea) of 31.0 kJ/mol in the WT, which is consistent with previous results (20). Correspondingly, the preexponential frequency factor, A0, for the lag in the WT was estimated as 3.2 × 108 s−1 (Fig. 6A and Table 2), with the caveat that the relatively narrow range of feasible experimental temperatures limits the accuracy of the frequency factor coefficient estimate and thus, the estimate of the entropy of activation, ΔSǂ, discussed below. The activation energy of the lag of V185N (30.0 kJ/mol) is similar to that of the WT, whereas the frequency factor of V185N (7.0 × 107 s−1) is lower than the WT, accounting for the fact that, despite the similar activation energy, the approach of the reaction coordinates to the transition state occurs much less frequently and hence, the reaction proceeds at a lower rate. In general, the frequency factor (A0) of the Arrhenius equation reflects the nature of the rate-limiting process. The lower frequency factor in the D1-V185N suggests that the amino acid substitution changes the rate-determining step (RDS) governing the lag phase (step 2 in Fig. 1C). The lower activation energies and frequency factors were also observed in D61 mutants. The most significant difference in activation energy was obtained in D61A, which has no H-bonding capacity, because a carboxyl is replaced by a methyl group. Here, the energy barrier is only 16.7 kJ/mol, and the frequency is three magnitudes lower than the WT, again suggesting a new RDS. This activation energy is slightly greater than the energy of pure diffusion controlled process (13 kJ/mol).

Fig. 5.

Normalized oxygen release kinetics of (A) WT and (B) V185N under various temperatures over the range from 3 °C to 33 °C.

Fig. S4.

Normalized polarographic transients from (A) D1-D61N and (B) D1-D61A under various temperatures over the range from ∼10 °C to 32 °C.

Fig. 6.

Arrhenius plots for (A) the lag phase and (B) the slow phase of O2 release in WT (black) and mutants D1-V185N (red), D1-D61N (blue), and D1-D61A (pink). The symbols correspond to experimental data, and the dashed lines are obtained from linear fits of these points. Rate vs. temperature data are plotted as . Ln is the natural logarithm of both sides of Arrhenius’ equation, where k is the estimated rate constant, A0 is the preexponential “frequency factor” term, and Ea is the activation energy obtained from the y intercept and slope.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of the lag phase for WT and mutant thylakoid membranes

| Ea (kJ·mol−1) | A (s−1) | tlag* (ms) | ΔSǂ (J·mol−1 K−1) | ΔHǂ (kJ·mol−1) | |

| WT | 31.0 | 3.2 × 108 | 0.6 | −89.9 | 28.7 |

| V185N | 30.0 | 7.0 × 107 | 1.4 | −101.5 | 27.9 |

| D61N | 24.1 | 9.0 × 106 | 1.2 | −120.3 | 21.5 |

| D61A | 16.7 | 4.9 × 105 | 1.1 | −144.1 | 14.3 |

The uncertainties in the activation energies are of the order of ±1.

The values for the individual time constants are measured at 27 °C.

The Arrhenius plot of rate constant of slow phase (kox) is shown in Fig. 6B, and the derived activation parameters are listed in Table 3. Over the temperature range from 3 °C to 33 °C, the data fit with a straight line yield an activation energy of 45.8 kJ/mol for the WT, which is in good agreement with previous reports (ref. 20 and references therein). Surprisingly, the activation energy for D1-V185N is only 22.3 kJ/mol, which is only one-half that of the WT. However, the corresponding frequency factor of 1.9 × 105 is five orders of magnitude lower than the WT, accounting for the large decrease in the rate of O2 formation. The lower frequency factor in the D1-V185N suggests that the amino acid substitution results in the change in RDS during one of the steps associated with Mn rereduction, dioxygen redox chemistry, and water insertion (step 4 in Fig. 1C). The corresponding Eyring treatment (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. S5) indicates that the new rate limitation in D1-V185N is characterized by a lower activation enthalpy (ΔHǂ) and a much less favorable entropy of activation (ΔSǂ). For both of the D1-D61 mutants, the retardation in the O2 release phase is also largely because of less favorable ΔSǂ, suggesting that the mutational defects impose a greater requirement to reorganize the reactants to achieve the optimal reaction configuration similar to the D1-V185N mutant.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters of O2 release (slow phase) for WT and mutant thylakoid membranes

| Ea (kJ·mol−1) | A (s−1) | tslow* (ms) | ΔSǂ (J·mol−1 K−1) | ΔHǂ (kJ·mol−1) | |

| WT | 45.8 | 5.2 × 1010 | 1.1 | −47.1 | 43.7 |

| V185N | 22.3 | 1.9 × 105 | 29.3 | −150.9 | 20.1 |

| D61N | 44.2 | 1.5 × 109 | 22.9 | −77.4 | 41.8 |

| D61A | 35.3 | 3.3 × 107 | 32.8 | −109.2 | 32.9 |

The uncertainties in the activation energies are of the order of ±2.

The values for the individual time constants are measured at 27 °C.

Fig. S5.

Eyring plots for (Left) the lag phase and (Right) the slow phase of O2 release in WT (black) and mutants D1-V185N (red), D1-D61N (blue), and D1-D61A (pink). The symbols correspond to experimental data, and the dashed lines were obtained from linear fits of these points.

SI Materials and Methods

Strains and Growth Conditions.

The naturally transformable, glucose-using strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 and the mutant derivatives were maintained on solid BG-11 (57) plates and in liquid BG-11 media buffered with HBG-11 supplemented with 5 mM glucose and 10 μM 3-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) (solid media only). Synechocystis cell cultures were first inoculated from plates into 100 mL HBG-11 with 5 mM glucose and grown while shaking under ∼80 μM m−2 s−1 cool white fluorescent lights at 30 °C. Then, the cultures were inoculated into 800 mL HBG-11 medium with 5 mM glucose and grown with bubbling filter sterilized air under the same photon flux density and temperature. Light intensity was measured with a Walz Universal Light Meter 500 (Effeltrich). Mutations of D1-V185N, D1-D61N, and D1-D61A were constructed in the psbA2 gene and introduced into a recipient strain of Synechocystis lacking all three psbA genes and containing a hexahistidine tag genetically fused to the C terminus of the CP47 protein. A hexahistidine-tagged control strain was similarly constructed using the same psbA-less recipient strain but transformed with the WT psbA2 gene, resulting in a strain possessing PSII activity similar to the true WT that is referred to as the WT.

Isolation of Thylakoid Membranes.

Thylakoid membranes were isolated essentially as described previously. Synechocystis cells were grown to midlog phase, harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 8,000 × g, and then, resuspended in 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1.2 M betaine, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM CaCl2 to a concentration of 1 mg chlorophyll mL−1. The resuspended cells were incubated in the dark and on ice for 1 h. Before cell breakage, benzamidine, ε-amino-η-caproic acid, and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride were added to the cell suspension to a concentration of 1 mM each. The cells were broken by five cycles (5 s on and 5 min off) of agitation with 0.1-mm-diameter zirconium/silica beads in a Bead-Beater (BioSpec Products) in a water–ice jacket. The extracted thylakoid membranes were collected by centrifugation at 40,000 rpm (Type 70 Ti rotor, Beckman) for 20 min at 4 °C in an ultracentrifuge (L8-70M; Beckman). The pelleted thylakoid membranes were resuspended in 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1.2 M betaine, 20 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM MgCl2 to a chlorophyll concentration of 1–1.5 mg mL−1 before being snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Polarographic Measurements of O2 Evolution.

Measurement of O2 release kinetics was performed with isolated thylakoid membranes using a bare platinum electrode that allows for the deposition of samples by centrifugation as described before. For each measurement, a sample of thylakoid membranes containing 3 µg chlorophyll was added to 500 µL 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH values of 5.0, 6.5, and 7.5), 1 M sucrose, 10 mM CaCl2, and 200 mM NaCl. Samples were centrifuged onto the electrode surface at 8,000 × g for 10 min at 20 °C in a Sorvall HB-4 Swing-Out Rotor. The temperature of electrode was regulated by circulating thermostated water through a copper jacket that surrounds the electrode. Polarization of the electrode (0.73 V) was turned on 10 s before the start of data acquisition, and the flash sequence was started 333 ms after that. The response time of the polarographic amplifier is ∼100 µs, whereas the electrode–electrolyte system responds within ∼200–400 µs at the specified NaCl concentration in the measuring buffer. Acquisition of the data and the control of the instrumentation were implemented using a plug-in data acquisition circuitry and LabView software (National Instruments) that permitted timing and coordination of the flash illumination and data acquisition in a synchronous mode with nanosecond accuracy (independent of computer motherboard and operating system). Before measurement of O2 release kinetics, the sample on the electrode was thermally equilibrated to the temperature of the water jacket for 10 min, exposed to a train of 50-µs flashes from a red (nominally 627 nm) light-emitting diode Luxeon III Emitter (Philips Electronics) driven by a strobe current generator (Pulsar 710; Advanced Illumination), and placed 0.9 cm from the surface of the electrode given at 4 Hz. The sample was exposed to/given up to 240 flashes in each measurement, and the signals were averaged.

Mathematical Model for Simulation of the O2 Electrode Signal.

The model used for fitting the O2 release curves divides the volume of the deposited PSII sample and the buffer above it into layers as developed previously (16, 34). The signal from the oxygen electrode is proportional to the O2 concentration in the lowest layer in contact with the surface of the electrode. Three processes are considered by the model:

-

i)

O2 diffusion—in the whole volume (all layers);

-

ii)

O2 production from PSII—only in the layers containing PSII; and

-

iii)

O2 consumption from the electrode only in the lowest PSII-containing layer, which is in contact with electrode surface.

At each time point, the model calculates the concentration of O2 in discrete layers of equal thickness (Δx), which contain either thylakoid membranes or only buffer. The model accounts for the effect of the thickness of the thylakoid membrane sample on the rate of diffusion of O2 from the electrodes surface by varying the number of thylakoid membrane-containing layers above the bottom layer (x = 0). On the bottom layer (x = 0), not only oxygen diffusion and production by PSII are considered but also, the oxygen consumption by the electrode. The three processes are described by a mathematical model, and the differential equations are solved by numerical integration. The equation used to calculate O2 concentration in the lowest (x = 0) layer as a result of diffusion from the neighboring layer (x = 1) in every moment t is

| [S1] |

After the laser flash, the evolved O2 is modeled to be a result of the reaction as shown in Scheme 1, and the O2 generation in the layer (x = 0) with PSII is calculated as

| [S2] |

In the simulation of Eq. S2, an additional time lag (tlag) is added as an additional shift of the time axis. The time offset (tlag) and k1 (sigmoidal rise) are used to simulate the overall delay resulting from the O2 production in PSII. The electrode processes are ill-understood and cannot be described sufficiently well by any physicochemical model, which means that the delayed rise of the O2 signal is described in a purely phenomenological way. Because the values of the two parameters used to describe the delay of the rise of the O2 signal are strongly correlated, we will report the sum of tlag and as lag phase.

O2 assumption from the electrode is calculated as

| [S3] |

Eq. S4 is used to calculate the concentration of O2 in the bottom layer (x = 0) of the thylakoid membrane sample at each time point t:

| [S4] |

Application of this model to O2 transients of WT and mutants resulted in an excellent match of experimental and simulated transients in previous studies (16, 34) and this study.

Discussion

In previous work, mutations designed to perturb the aqueous channels surrounding the Mn4CaO5 of PSII were described (23). Among these, mutations at the hydrophobic D1-V185 located in the proximity of O5, a strong candidate for the slowly exchanging substrate water (Ws) (35, 36), proved to have the most dramatic effects on the catalytic properties of the Mn4CaO5. The bulky phenyalanine substitution (D1-V185F) permitted assembly of Mn clusters that could advance at least to the state but were otherwise inactive with respect to O2 evolution. The asparagine substitution (D1-V185N), further studied here, exhibited dramatic slowdowns of both the lag phase and the O2 release phase of the transition. These observations are reminiscent of mutations at nearby D1-D61, which also greatly retard both kinetic phases (16, 20, 32). From a structural perspective, both D61 and V185 interact with a cluster of water, including W1, W2, W3, and W4 that form an HBN connecting the polar atoms of YZ, Cl−, and the atoms Mn4, Ca, and O5 of the Mn4CaO5 (Fig. 1). Because the carboxyl group of D1-D61 very likely mediates the egress of protons from the Mn4CaO5, it is reasonable to suppose that D1-V185N also interferes with proton release during the transition. However, this slowdown of the transition proved to have characteristics suggesting a more complex molecular rearrangement, perhaps including but not limited to proton movement.

pH-Independent Lag Phase in V185N.

Little is known of the site of origin and the egress pathway of the released proton, although an extensive HBN connected with the D1-D61 is proposed to be involved (16, 29, 30, 37, 38). Computational analyses suggest that an H bond-mediated proton donation to the D1-D61 carboxylate from W1, one of two waters coordinated with dangler Mn4, occurs on oxidation of the WOC in the higher S states (39–41). The fact that mutations of D1-D61 produce large extension of the lag is consistent with the idea that this carboxylate mediates a rate-limiting proton release during through this residue. However, a similarly protracted lag phase exists in the D1-V185N mutant, and its duration is insensitive to both pH and buffer concentration (Fig. 2, Fig. S3, and Table 1). Likewise, the O2 release phase is only weakly dependent on pH and independent of buffer concentration. This pH independence in D1-V185N contrasts with the WT, where we were able to confirm previous results (13, 19), indicating that low pH creates, in effect, a proton back-pressure that becomes rate-limiting for the transition. Therefore, the long lag in the D1-V185N mutant is caused by another RDS that may be distinct from proton transfer per se. Two possibilities could account for this: option i is that proton release from the WOC to the bulk phase remains fast but that another process, such as a molecular rearrangement within the WOC, becomes rate-limiting, and option ii is that the proton is transferred within PSII but not released to solution. In this case, transfer is scarcely affected by pH of bulk phase because of its isolation within the PSII. Both options are consistent with the altered thermal activation properties that clearly indicate an alternative RDS (Fig. 6 and Table 2). However, these two possibilities are not mutually exclusive: if a mutationally impaired molecular rearrangement involves the repositioning of water molecules (or another titratable group), then the hindered repositioning could impair an internal proton transfer. The results of the hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) KIE isotope experiments (Figs. 4 and 5) shed light on the nature of the defect and point to the impaired movement of water as the origin of the defect in the lag phase. The monotonic KIE of 1.4 across the range of pL for the lag phase is exactly the value anticipated for either a proton transfer process or a process that depends on the reorganization of water molecules (34). Although the proton transfer per se also has an expected KIE of 1.4, actual proton transfers occur in the picosecond time domain, and it is the slower rearrangement of water that limits the formation of productive Grotthuss proton conduction pathways where mobile water is involved (34). Because the asparagine is not titratable, it is unlikely that it competes with titratable groups along the native proton transfer pathway. Moreover, the slowdown seems dominated by an entropic penalty (Fig. 6 and Table 2). Therefore, it is more likely that the mutation alters the HBN in a manner that disturbs the organization of water molecules and thereby, imposes a kinetic requirement for a more drastic rearrangement of the water and possibly, other moieties to enable proton transfer (or proton tautomerization within the WOC). This proposal is represented schematically in Fig. 7. This interpretation is consistent with findings that the transition is multiphasic, even in the WT, although the additional kinetic phases remain to be defined and could involve secondary movements of protons (ref. 13 and references therein).

Fig. 7.

Representative models for the transition, accounting for the deduced structural rearrangement occurring before dioxygen formation. The nature of the rearrangement affected by the mutations remains to be defined chemically and may include a structural isomerization and/or a proton tautomerization likely involving the movement of water molecules (in the text). The structure in Left represents the recently deduced S3+ structure (45) immediately after oxidation of YZ and highlights bridging oxo, O5, that is close to the site of the D1-V185N mutation. Two alternative mechanisms involving either (Upper Center) nucleophilic attack or (Lower Center) radical coupling are shown for the formation of the transient S4 state. Please note that there are a number of proposed O-O bond formation trajectories for either the nucleophilic attack model (46–48) or radical coupling model (28, 35, 45, 49–52). Experimental evidence for an S4 intermediate state is not yet available, and possibilities include the limiting cases of a metal-centered MnV ≡ O intermediate species or a ligand-centered oxidation intermediate as an MnIV-O● radical. Similarly, there have been multiple radical coupling type mechanisms proposed between O5 and an Mn-O radical species involving either an open or closed cubane structure (28, 50, 52, 54). The binding of at least one H2O molecule during is suggested by water exchange experiments (36), and impeded movement could account for the slowdown in the O2 release phase of the transition.

Perturbations in the Water Cluster Underlie the Mutational Slowdowns of Both Phases of Transition.

If a structural rearrangement involving water movement becomes the new RDS governing the lag phase in D1-V185N, how does the mutation affect both the lag and slow phases in a seemingly correlated fashion? In other words, as with other cases where chemical or mutational alteration results in the slowdown of the transition, it is not just the lag phase or just the slow phase that is affected, but it is both that are retarded (16, 20, 42). Other than reinforcing the above conclusions on the imposition of a new RDS involving rearrangement of water in the lag phase, the thermal activation experiments are consistent with the pH and KIE experiments in revealing that the lag and slow phases share similar defects as a result of the mutations. Remarkably, the activation enthalpy barrier, ΔHǂ, for the lag is virtually unchanged compared with the WT (both ∼28 kJ mol−1) and is actually lower for the slow phase, where ΔHǂ is one-half the WT value (20 vs. 44 kJ mol−1). Instead, the slowdowns of both the lag and slow phases of the transition are because of less favorable entropies of activation, ΔSǂ (Tables 2 and 3). These trends also apply to the D1-D61 mutants, although subtle differences exist as briefly discussed below. These increased entropic penalties can be interpreted to mean that the mutational slowdowns (lag and slow phases) result from the additional time required for the reactants to reorganize to realize the optimal transition-state configuration(s). We imagine that the mutation creates a nonoptimal ground-state configuration of reactants that imposes a slower reorganization step required to reach the transition states on each of these phases and that this corresponds to the less favorable entropy of reaction, . Accordingly, the mutation results in an altered ground state, where the reactants are misconfigured and must reorganize to reach the transition state required for passage through the lag phase. Likewise, a similar reorganization penalty is imposed in D1-V185N to reach the transition state required for passage through the O2-forming phase. Analogous alterations of the thermal activation characteristics have been observed in other enzyme systems. For example, certain mutations of β-gal reduce catalytic rates because of a conformational perturbation affecting the active site that causes the appearance of a new RDS (43). In that case, the effects of the mutation were reversed by the binding of an antibody that stabilizes the native conformation of the enzyme. In the absence of antibody, the mutant enzyme was characterized by a decrease in the preexponential term of the Arrhenius equation and a correspondingly less favorable ΔSǂ, which is interpreted to indicate that the enzyme (without antibody) may pass through a larger spectrum of conformation states before arriving at the transition-state configuration. The stimulatory effect of the antibody is caused by a narrowing of this spectrum of accessible conformational states and allows the antibody-constrained enzyme to find the transition state more quickly, because it samples a smaller conformation space. However, the best comparison is with altered forms of PSII itself: the substitution of Ca2+ with quasifunctional Sr2+ slows both phases of the transition because of a decrease in , albeit to different extents for the fast and slow phases compared with D1-V185N (42). It was argued that there are differences between coordination geometry and chemistry between Ca2+ and Sr2+ with respect to a less favorable ΔSǂ of the dissociation of coordinated H2O. It was proposed that the slowdowns reflect the less favorable entropic term associated with delivery of H2O from Sr2+ (rather than Ca2+) to one of the Mn atoms of the cluster. In the case of the D1-V185N mutation, an alteration in the structure of the water cluster is a distinct possibility, because the mutation introduces a strong H-bonding moiety in a place where there was none. Interestingly, the Sr2+/Br−-substituted PSII samples seem to retain rapid proton release (supplemental figure 8 in ref. 36), despite longer lag and slower release phases measured polarographically (24). By analogy, we might expect proton release to be rapid on His190+ formation in D1-V185N but that the protracted lag corresponds to another process, such as the movement of water and a corresponding rearrangement of the HBN. This interpretation is consistent with the conclusion that the mutation imposes new RDSs for both the lag and O2 release phases.

Effects of D1-D61 Mutations Distinct from D1-V185N.

Despite outward similarities in slowing down of the lag and O2 release phases of the transition, the D1-D61 mutations proved to be distinct from the D1-V185N mutant with respect to their pH and thermal activation characteristics (Tables 1–3). Unlike the D1-V185N mutation, where the enthalpy of activation for the lag phase is virtually unchanged, the ΔHǂ values for both D1-D61 mutants are significantly decreased compared with the WT, with the replacement of the carboxyl group with a methyl group in D1-D61A being the most decreased. Molecular simulations suggest that the D1-D61 carboxyl may adopt different conformations and different H-bonding interactions/protonation states that may relate to the proposed role as a mediator of proton efflux (39, 44), and FTIR studies using the D1-D61A mutant are consistent with these predictions (29). Therefore, we tentatively assign the decrease in the ΔHǂ values in the D1-D61 mutants as reflecting the loss of bonding interactions of the carboxyl group that must normally be broken during the lag phase. This assignment is consistent with D1-D61 acting as a gate that involves proton transfer and provides directionality by adopting different H-bond and ionic configurations with adjacent groups depending on the state of the enzyme (44).

Implications for the Mechanism of O2 Formation.

The S3 ground state () seems to exist with four Mn ions in the IV oxidation state, each having octahedral local geometry, and the O5 oxo bonded to Mn4, which puts the overall arrangement of the Mn4CaO5 as being in the “open cube” configuration, structurally analogous to the S2+ low-spin conformational isomer (45). Presently, there are two classes of dioxygen formation mechanisms that are most actively discussed: models involving nucleophilic attack of a free water or Ca2+-bound hydroxide (identified as Ws) with an MnV = O or MnIV-O● (oxyl radical) (46–48). Alternatively, radical coupling between either a Ca-oxyl radical and an MnIV-oxyl radical or between an MnIV-oxyl radical and a bridging μ-oxo are proposed (28, 35, 45, 49–52). Regarding the role of water movement in relation to the nucleophilic attack models, a deprotonation on W2 (-OH) preceding the oxidation of Mn4 or a deprotonation yielding the nucleophilic hydroxide may require rearrangements of titratable moieties, such as water, and may account for at least part of the polyphasic lag that could be altered by mutations. The proposed subsequent attack reaction is proposed to be promoted by substitution of the Ca2+-bound hydroxide by a water molecule in the second coordination sphere (53). Such a substitution reaction is inherently a rearrangement, and its retardation caused by the mutation could account for longer slow phase. Fig. 7 illustrates the key finding of a rearrangement occurring before dioxygen formation presents two possible S4 intermediates after the rearrangement.

Recent analysis indicates that both fast and slowly exchangeable substrate waters (Wf and Ws, respectively) are bound to Mn and that Ws is either O5 or possibly, W2 (28, 35, 36, 45, 51, 54). These results have been interpreted to favor a direct radical coupling mechanism. Siegbahn (50) proposed a model involving the reaction between an oxyl radical and a bridging oxo. In this model, the Mn cluster is in the open cube configuration (O5 bound to dangler Mn4), and radical coupling was proposed to occur between the O5 oxo and an oxyl radical that forms after deprotonation of a hydroxide on the proximal Mn1. This model is consistent with the recent ground-state model, including the deduced electronic structure steering the spin configuration of the reacting oxygen atoms (45). It was hypothesized that the release of O2 and the refilling of the vacant substrate site occur as a concerted process (28). If so, then the proton release might trigger the insertion of water; however, this possibility would mean that the water insertion should have the same kinetics as O2 release, and therefore, insertion could not account for the rearrangement during the lag occurring between the initial proton release and the appearance of O2. Recently, Siegbahn (50) described an alternative model for bond formation between MnIV-oxyl radical and bridging μ-oxo described to involve the formation of the radical on Mn4 rather than Mn1 with the Mn4CaO5 in the closed cube configuration (52) in contrast to the original prediction (50). This model seemingly contradicts recent results, providing good support for the cluster occurring as the open cube in the ground state (45). However, if the lag phase involves an open–closed isomerization (Fig. 7, Lower Center), by analogy with the proposed isomerization during the transition (41), then this alternative model would be feasible. Because the open–closed isomerization is proposed to be accompanied by extensive rearrangements of water (28, 41, 55, 56), this alternative, therefore, also fits with this conclusion that critical water rearrangements, perhaps coupled to structural rearrangements, precede the dioxygen chemistry.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Sample Preparation.

The naturally transformable, glucose-using strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 and the mutant derivatives were maintained on solid BG-11 (57) plates and in liquid BG-11 media buffered with 20 mM Hepes-NaOH, pH 8.0 (HBG-11) supplemented with 5 mM glucose and 10 μM 3-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) (solid media only). Synechocystis cell cultures were first inoculated from plates into 100 mL HBG-11 with 5 mM glucose and grown while shaking under ∼80 μΜ m−2 s−1 cool white fluorescent lights at 30 °C. Then, the cultures were inoculated into 800 mL HBG-11 medium with 5 mM glucose and grown with bubbling-filter sterilized air under the same photon flux density and temperature. Light intensity was measured with a Walz Universal Light Meter 500 (Effeltrich). Mutations of D1-V185N, D1-D61N, and D1-D61A were constructed in the psbA2 gene and introduced into a recipient strain of Synechocystis lacking all three psbA genes and containing a hexahistidine tag genetically fused to the C terminus of the CP47 protein. The details of strains and growth conditions are described in SI Materials and Methods. A hexahistidine-tagged control strain was similarly constructed using the same psbA-less recipient strain but transformed with the WT psbA2 gene, resulting in a strain possessing PSII activity similar to the true WT that is referred to as the WT.

Isolation of Thylakoid Membranes.

Thylakoid membranes were isolated essentially as described previously. Synechocystis cells were grown to midlog phase, harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 8,000 × g, and then, resuspended in 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1.2 M betaine, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM CaCl2 to a concentration of 1 mg chlorophyll mL−1. The resuspended cells were incubated in the dark and on ice for 1 h. Before cell breakage, benzamidine, ε-amino-η-caproic acid, and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride were added to the cell suspension to a concentration of 1 mM each. The cells were broken by five cycles (5 s on and 5 min off) of agitation with 0.1-mm-diameter zirconium/silica beads in a Bead-Beater (BioSpec Products) in a water–ice jacket. The extracted thylakoid membranes were collected by centrifugation at 40,000 rpm (Type 70 Ti rotor, Beckman) for 20 min at 4 °C in an ultracentrifuge (L8-70M; Beckman). The pelleted thylakoid membranes were resuspended in 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1.2 M betaine, 20 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM MgCl2 to a chlorophyll concentration of 1–1.5 mg mL−1 before being snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Polarographic Measurements of O2 Evolution.

Measurement of O2 release kinetics was performed with isolated thylakoid membranes using a bare platinum electrode that allows for the deposition of samples by centrifugation as described before. For each measurement, a sample of thylakoid membranes containing 3 µg chlorophyll was added to 500 µL 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH values of 5.0, 6.5, and 7.5), 1 M sucrose, 10 mM CaCl2, and 200 mM NaCl. Samples were centrifuged onto the electrode surface at 8,000 × g for 10 min at 20 °C in a Sorvall HB-4 Swing-Out Rotor. The temperature of electrode was regulated by circulating thermostated water through a copper jacket that surrounds the electrode. Polarization of the electrode (0.73 V) was turned on 10 s before the start of data acquisition, and the flash sequence was started 333 ms after that. The response time of the polarographic amplifier is ∼100 µs, whereas the electrode–electrolyte system responds within ∼200–400 µs at the specified NaCl concentration in the measuring buffer. Acquisition of the data and the control of the instrumentation were implemented using a plug-in data acquisition circuitry and LabView software (National Instruments) that permitted timing and coordination of the flash illumination and data acquisition in a synchronous mode with nanosecond accuracy (independent of computer motherboard and operating system). Before measurement of O2 release kinetics, sample on the electrode was thermally equilibrated to the temperature of the water jacket for 10 min and then, exposed to a train of 50-µs flashes from a red (nominally 627 nm) light-emitting diode Luxeon III Emitter (Philips Electronics) driven by a strobe current generator (Pulsar 710; Advanced Illumination) placed 0.9 cm from the surface of the electrode given at 4 Hz. Sample was given up to 240 flashes in each measurement, and the signals were averaged. Mathematical fitting of the resultant O2 signals was performed using a reaction–diffusion model summarized in Scheme 1 and Eq. 1 as previously described (16, 33). The model takes into account the production of O2 from PSII, the diffusive processes governing the concentration of O2 at the platinum electrode surface, and the electrode reaction consuming O2 at that surface. SI Materials and Methods and ref. 16 have information on the implementation of the model and the details of the fitting.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Richard Debus, Prof. Charles Yocum, and Prof. Robert Gennis for stimulating discussions and Prof. Chuck Dismukes for suggesting varying buffer concentrations for evaluating the potential rate limitation by proton release. The authors also thank Prof. Richard Debus for the D1-D61 strains. This work was funded by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-1244586.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1512008112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Barber J. Photosystem II: The water-splitting enzyme of photosynthesis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2012;77:295–307. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2012.77.014472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardona T, Sedoud A, Cox N, Rutherford AW. Charge separation in photosystem II: A comparative and evolutionary overview. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817(1):26–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dau H, Zaharieva I, Haumann M. Recent developments in research on water oxidation by photosystem II. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16(1-2):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox N, Pantazis DA, Neese F, Lubitz W. Biological water oxidation. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46(7):1588–1596. doi: 10.1021/ar3003249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahlbrink R, et al. Function of tyrosine Z in water oxidation by photosystem II: Electrostatical promotor instead of hydrogen abstractor. Biochemistry. 1998;37(4):1131–1142. doi: 10.1021/bi9719152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haumann M, Mulkidjanian A, Junge W. Tyrosine-Z in oxygen-evolving photosystem II: A hydrogen-bonded tyrosinate. Biochemistry. 1999;38(4):1258–1267. doi: 10.1021/bi981557i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hays AM, Vassiliev IR, Golbeck JH, Debus RJ. Role of D1-His190 in proton-coupled electron transfer reactions in photosystem II: A chemical complementation study. Biochemistry. 1998;37(32):11352–11365. doi: 10.1021/bi980510u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rappaport F, et al. Probing the coupling between proton and electron transfer in photosystem II core complexes containing a 3-fluorotyrosine. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(12):4425–4433. doi: 10.1021/ja808604h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito K, Shen J-R, Ishida T, Ishikita H. Short hydrogen bond between redox-active tyrosine Y(Z) and D1-His190 in the photosystem II crystal structure. Biochemistry. 2011;50(45):9836–9844. doi: 10.1021/bi201366j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joliot P, Barbieri G, Chabaud R. Un nouveau modele des centres photochimique du systeme II. Photochem Photobiol. 1969;10(5):309–329. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kok B, Forbush B, McGloin M. Cooperation of charges in photosynthetic O2 evolution-I. A linear four step mechanism. Photochem Photobiol. 1970;11(6):457–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1970.tb06017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bao H, Dilbeck PL, Burnap RL. Proton transport facilitating water-oxidation: The role of second sphere ligands surrounding the catalytic metal cluster. Photosynth Res. 2013;116(2-3):215–229. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9907-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klauss A, Haumann M, Dau H. Seven steps of alternating electron and proton transfer in photosystem II water oxidation traced by time-resolved photothermal beam deflection at improved sensitivity. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119(6):2677–2689. doi: 10.1021/jp509069p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klauss A, Haumann M, Dau H. Alternating electron and proton transfer steps in photosynthetic water oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(40):16035–16040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206266109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rappaport F, Blanchard-Desce M, Lavergne J. Kinetics of electron transfer and electrochromic change during the redox transitions of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1184(2-3):178–192. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dilbeck PL, et al. The D1-D61N mutation in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 allows the observation of pH-sensitive intermediates in the formation and release of O₂ from photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2012;51(6):1079–1091. doi: 10.1021/bi201659f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Razeghifard MR, Pace RJ. EPR kinetic studies of oxygen release in thylakoids and PSII membranes: A kinetic intermediate in the S3 to S0 transition. Biochemistry. 1999;38(4):1252–1257. doi: 10.1021/bi9811765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haumann M, et al. Photosynthetic O2 formation tracked by time-resolved x-ray experiments. Science. 2005;310(5750):1019–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.1117551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerencsér L, Dau H. Water oxidation by photosystem II: H(2)O-D(2)O exchange and the influence of pH support formation of an intermediate by removal of a proton before dioxygen creation. Biochemistry. 2010;49(47):10098–10106. doi: 10.1021/bi101198n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clausen J, Debus RJ, Junge W. Time-resolved oxygen production by PSII: Chasing chemical intermediates. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1655(1-3):184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Razeghifard MR, Wydrzynski T, Pace RJ, Burnap RL. Yz. reduction kinetics in the absence of the manganese-stabilizing protein of photosystem II. Biochemistry. 1997;36(47):14474–14478. doi: 10.1021/bi970116g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burnap RL, Shen JR, Jursinic PA, Inoue Y, Sherman LA. Oxygen yield and thermoluminescence characteristics of a cyanobacterium lacking the manganese-stabilizing protein of photosystem II. Biochemistry. 1992;31(32):7404–7410. doi: 10.1021/bi00147a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dilbeck PL, Bao H, Neveu CL, Burnap RL. Perturbing the water cavity surrounding the manganese cluster by mutating the residue D1-valine 185 has a strong effect on the water oxidation mechanism of photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2013;52(39):6824–6833. doi: 10.1021/bi400930g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boussac A, et al. Biosynthetic Ca2+/Sr2+ exchange in the photosystem II oxygen-evolving enzyme of Thermosynechococcus elongatus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(22):22809–22819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen JR, Kamiya N. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å. Nature. 2011;473(7345):55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature09913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suga M, et al. Native structure of photosystem II at 1.95 A resolution viewed by femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature. 2015;517(7532):99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature13991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pantazis DA, Ames W, Cox N, Lubitz W, Neese F. Two interconvertible structures that explain the spectroscopic properties of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II in the S2 state. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(39):9935–9940. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox N, Messinger J. Reflections on substrate water and dioxygen formation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1827(8-9):1020–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debus RJ. FTIR studies of metal ligands, networks of hydrogen bonds, and water molecules near the active site Mn₄CaO₅ cluster in Photosystem II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1847(1):19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Debus RJ. Evidence from FTIR difference spectroscopy that D1-Asp61 influences the water reactions of the oxygen-evolving Mn4CaO5 cluster of photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2014;53(18):2941–2955. doi: 10.1021/bi500309f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho FM, Styring S. Access channels and methanol binding site to the CaMn4 cluster in Photosystem II based on solvent accessibility simulations, with implications for substrate water access. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777(2):140–153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hundelt M, Hays AM, Debus RJ, Junge W. Oxygenic photosystem II: The mutation D1-D61N in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 retards S-state transitions without affecting electron transfer from YZ to P680+ Biochemistry. 1998;37(41):14450–14456. doi: 10.1021/bi981164j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavorel J. Determination of the photosynthetic oxygen release time by amperometry. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1101(1):33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agmon N. The Grotthuss mechanism. Chem Phys Lett. 1995;244(5-6):456–462. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rapatskiy L, et al. Detection of the water-binding sites of the oxygen-evolving complex of Photosystem II using W-band 17O electron-electron double resonance-detected NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(40):16619–16634. doi: 10.1021/ja3053267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilsson H, Rappaport F, Boussac A, Messinger J. Substrate-water exchange in photosystem II is arrested before dioxygen formation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4305. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferreira KN, Iverson TM, Maghlaoui K, Barber J, Iwata S. Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Science. 2004;303(5665):1831–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.1093087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Service RJ, Hillier W, Debus RJ. Network of hydrogen bonds near the oxygen-evolving Mn(4)CaO(5) cluster of photosystem II probed with FTIR difference spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2014;53(6):1001–1017. doi: 10.1021/bi401450y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amin M, et al. Proton-coupled electron transfer during the S-state transitions of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119(24):7366–7377. doi: 10.1021/jp510948e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Retegan M, Cox N, Lubitz W, Neese F, Pantazis DA. The first tyrosyl radical intermediate formed in the S2-S3 transition of photosystem II. Phys Chem Phys. 2014;16(24):11901–11910. doi: 10.1039/c4cp00696h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Narzi D, Bovi D, Guidoni L. Pathway for Mn-cluster oxidation by tyrosine-Z in the S2 state of photosystem II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(24):8723–8728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401719111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rappaport F, Ishida N, Sugiura M, Boussac A. Ca2+ determines the entropy changes associated with the formation of transition states during water oxidation by Photosystem II. Energy Environ Sci. 2011;4(7):2520–2524. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Messerw, Melchers F (1970) Genetic analysis of mutants producing defective β-galactosidase which can be activated by specific antibodie. Mol Gen Genet 109(2):152–161. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Rivalta I, et al. Structural-functional role of chloride in photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2011;50(29):6312–6315. doi: 10.1021/bi200685w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cox N, et al. Photosynthesis. Electronic structure of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II prior to O-O bond formation. Science. 2014;345(6198):804–808. doi: 10.1126/science.1254910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pecoraro VL, Baldwin MJ, Caudle MT, Hsieh W-Y, Law N. A proposal for water oxidation in Photosystem II. Pure Appl Chem. 1998;70(4):925–929. [Google Scholar]

- 47.McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW. Water-splitting chemistry of photosystem II. Chem Rev. 2006;106(11):4455–4483. doi: 10.1021/cr0204294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vinyard DJ, Khan S, Brudvig GW. Photosynthetic water oxidation: Binding and activation of substrate waters for O-O bond formation. Faraday Discuss. October 8, 2015 doi: 10.1039/c5fd00087d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Messinger J. Evaluation of different mechanistic proposals for water oxidation in photosynthesis on the basis of Mn4OxCa structures for the catalytic site and spectroscopic data. Phys Chem Phys. 2004;6(20):4764–4771. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siegbahn PE. Water oxidation mechanism in photosystem II, including oxidations, proton release pathways, O-O bond formation and O2 release. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1827(8-9):1003–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pérez Navarro M, et al. Ammonia binding to the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II identifies the solvent-exchangeable oxygen bridge (μ-oxo) of the manganese tetramer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(39):15561–15566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304334110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li X, Siegbahn PE. Alternative mechanisms for O2 release and O-O bond formation in the oxygen evolving complex of photosystem II. Phys Chem Phys. 2015;17(18):12168–12174. doi: 10.1039/c5cp00138b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sproviero EM, Gascón JA, McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW, Batista VS. Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics study of the catalytic cycle of water splitting in photosystem II. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(11):3428–3442. doi: 10.1021/ja076130q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nilsson H, Krupnik T, Kargul J, Messinger J. Substrate water exchange in photosystem II core complexes of the extremophilic red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1837(8):1257–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bovi D, Narzi D, Guidoni L. The S2 state of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II explored by QM/MM dynamics: Spin surfaces and metastable states suggest a reaction path towards the S3 state. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52(45):11744–11749. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siegbahn PEM. Substrate water exchange for the oxygen evolving complex in PSII in the S1, S2, and S3 states. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(25):9442–9449. doi: 10.1021/ja401517e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury JB, Herdman M, Stanier RY. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]