Abstract

In the last two decades the strategy of treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis has changed. Endoscopic therapy of patients with symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis has a high rate of efficiency. Here we present a description of a patient with parenchymal limited necrosis of the pancreas and a disruption of the main pancreatic duct. In the treatment, active transpapillary drainage of the pancreatic necrosis (through the major duodenal papilla) was performed and insertion of an endoprosthesis into the main pancreatic duct (through the minor duodenal papilla) was applied, which enabled a bypass over the infiltration and resulted in complete resolution.

Keywords: walled-off pancreatic necrosis, acute pancreatitis, endoscopic drainage, transpapillary drainage

Introduction

In the last two decades the strategy of treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis and its consequences have changed [1–5]. Previously, the treatment of pancreatic necrosis was limited to surgical intervention [6]. Procedures of open necrosectomy are associated with high morbidity and mortality [6, 7]. In the past decades technological progress has led to development of minimally invasive techniques of walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) treatment [1–3]. These techniques include procedures performed with an endoscope, a laparoscope and a nephroscope, which enable a transperitoneal, retroperitoneal, transmural or transpapillary approach to necrosis [2]. Widening of an access to necrosis in a step-up approach to treatment creates better drainage conditions [1]. In the randomised trial performed by van Santvoort et al. the two methods of treatment of necrotising pancreatitis were compared [7]. The researchers found that a minimally invasive step-up approach significantly reduces the number of complications or deaths in comparison to open necrosectomy [7]. Similar results proving higher efficiency of minimal invasive methods of infected pancreatic necrosis treatment were published by Szeliga et al. [8].

Endoscopic treatment of necrosis of the pancreas consists of transmural drainage (through the gastric or duodenal wall), transpapillary drainage or a combination of both methods of approach to the necrotic cavity [9, 10].

Here we describe the treatment of a patient with parenchymal pancreatic necrosis who was treated with transpapillary drainage, being the only route of access to the necrosis.

Case report

A 32-year-old man with pancreatic ascites in the course of chronic pancreatitis was admitted to the department in April 2012. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen showed a reservoir of parenchymal necrosis measuring 58 mm × 45 mm in the area of the head of the pancreas and a large amount of fluid in the peritoneal cavity. The patient experienced five attacks of acute pancreatitis – the last one in December 2011. During the stay in the department paracentesis was performed twice and a total of 12 l of ascitic fluid was collected. Amylases in ascitic fluid reached 5746 U/l. During endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) the guidewire was introduced into the collection of WOPN through the major duodenal papilla and the outflow of dense and foul-smelling necrotic content was observed (Photos 1, 2 A, B). Injected contrast medium filled the cavity of the necrosis and confirmed its location in the area corresponding to the ventral pancreas and its communication with the duct of the dorsal pancreas in the area of the pancreatic isthmus. Constant medium did not leak outside the duct, but was drained into the duodenum solely through the minor duodenal papilla. On the basis of fluoroscopic imaging the anatomical variation of incomplete pancreas divisum was diagnosed (Photo 1). Sphincterotomy of major duodenal papilla was performed. Attempts to insert the guidewire into the body of the pancreas did not succeed. Through the major duodenal papilla a 7 Fr endoprosthesis and 7 Fr nasogastric tube were inserted into the cavity of the WOPN (Photos 3 A, B). Lavage through the nasogastric tube with 40 ml of saline solution every four hours was administered. After 7 days of active drainage and in the absence of disease symptoms and total regression of the necrotic cavity on imaging, the decision of nasogastric tube removal was made, but the prosthesis was left in the necrotic cavity. After 2 days ERCP was carried out for the second time. Through the minor duodenal papilla the guidewire was introduced into the accessory pancreatic duct (the duct of Santorini) and into the distal part of the main pancreatic duct in the body and tail of the pancreas. After injection of contrast medium a leak in the body of the pancreas into the peritoneal cavity was observed. Sphincterotomy of minor duodenal papilla was performed. The duct of Santorini was mechanically enlarged using a 7 Fr dilator. Next a 7 Fr endoprosthesis was introduced into the main pancreatic duct through the minor duodenal papilla (Photo 4). Its distal end was placed in the tail of the pancreas, creating a bypass over disruption of the duct. The patient was discharged in good health condition. During 6-month follow-up the patient did not report any symptoms. Neither ascites nor recurrence of the necrotic collection were observed on imaging.

Photo 1.

Contrast medium delivered though the major duodenal papilla filled the necrotic cavity, which was located in the region corresponding to the ventral pancreas and communicated by a thin duct with the dorsal pancreas in the area of the isthmus of the pancreas

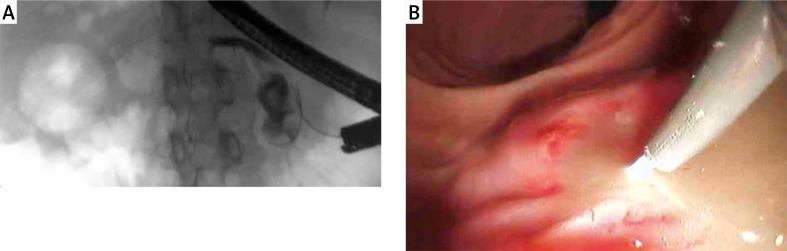

Photos 2 A, B.

A guidewire inserted through the major duodenal papilla into the necrotic cavity with the outflow of dense fluid with fragments of solid debris

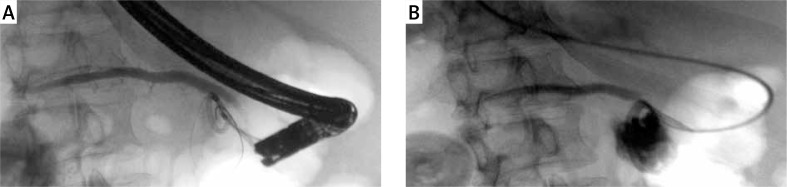

Photos 3 A, B.

A 7 Fr endoprosthesis and nasogastric tube inserted into the walled-off pancreatic necrosis though the major duodenal papilla

Photo 4.

A 7 Fr endoprosthesis was inserted into the main pancreatic duct though the minor duodenal papilla, creating a bypass over the damaged fragment of the duct

Discussion

Pancreas divisum is the most common congenital anatomical variation of the pancreas and a frequent cause of recurrent acute pancreatitis [11], which may lead to the development of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatic ascites as one of the symptoms of chronic pancreatitis is due to damage of the Wirsung duct [12]. In imaging it is visible as a contrast medium leak into the peritoneal cavity. Introduction of an endoprosthesis creating a bypass over the damaged area into the main pancreatic duct leads to leak removal and improvement of health [13].

In the last three decades many reports on the efficiency of transpapillary drainage of pseudocysts have been published [14]. Papers recommending the use of this method as a single route of approach to WOPN are sparse in the literature. Baron et al. [9], who presented the results of endoscopic treatment in patients with WOPN, applied transpapillary drainage as a single method of approach in one out of 11 patients. Similarly, Papachristou et al. [10] used this method in one out of 53 subjects. The transpapillary approach is performed much more frequently in combination with transmural or percutaneous drainage as one of several methods of approach to the necrotic cavity [9, 10, 15].

Endoscopic treatment of patients with symptomatic WOPN shows a high rate of efficiency [15]. If a cavity of necrosis communicates with a pancreatic duct, transpapillary drainage is an efficient method of treatment especially in collections below 6 cm [16]. Bhasin et al. [17] proved that transpapillary drainage may serve as an effective method of treatment without increasing the risk of cavity infection, including in cases when the diameter of the pseudocyst exceeds 6 cm. However, it should be kept in mind that due to the presence of solid debris in the cavity the results of endoscopic drainage of WOPN are worse than those obtained during endotherapy of pseudocysts, which makes the comparison of the two mentioned groups difficult. Baron et al. [18] succeeded in the drainage of pseudocysts in 92% of patients, in comparison to 72% of patients with WOPN.

Conclusions

In the described case, transpapillary drainage of the WOPN through the major duodenal papilla and insertion of the endoprosthesis into the main pancreatic duct through the minor duodenal papilla, creating a bypass over the infiltration, led to complete recovery.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Freeman ML, Werner J, van Santvoort HC, et al. Interventions for necrotizing pancreatitis: summary of a multidisciplinary consensus conference. Pancreas. 2012;41:1176–94. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318269c660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loveday BP, Mittal A, Phillips A, Windsor JA. Minimally invasive management of pancreatic abscess, pseudocyst, and necrosis: a systematic review of current guidelines. World J Surg. 2008;32:2383–94. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9701-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Šileikis A, Beiša V, Beiša A, et al. Minimally invasive retroperitoneal necrosectomy in management of acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2013;8:29–35. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2011.30943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Šileikis A, Beiša V, Zdanytè E, et al. Minimally invasive management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2013;8:211–5. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2011.33809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czernik M, Stefańczyk L, Szubert W, et al. Endovascular treatment of pseudoaneurysms in pancreatitis. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2014;9:138–44. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2014.41621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley EL., 3rd A fifteen year experience with open drainage for infected pancreatic necrosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:215–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. New Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szeliga J, Jackowski M. Minimally invasive procedures in severe acute pancreatitis treatment – assessment of benefits and possibilities of use. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2014;9:170–8. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2014.41628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron TH, Thaggard WG, Morgan DE, Stanley RJ. Endoscopic therapy for organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:755–64. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8780582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papachristou GI, Takahashi N, Chahal P, et al. Peroral endoscopic drainage/debridement of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Ann Surg. 2007;245:943–51. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000254366.19366.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernard JP, Sahel J, Giovanni M, Sarles H. Pancreas divisum is a probable cause of acute pancreatitis: a report of 137 cases. Pancreas. 1990;5:248–54. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varadarajulu S, Noone TC, Tutuian R, et al. Predictors of outcome in pancreatic duct disruption managed by endoscopic transpapillary stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:568–75. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02832-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shrode CW, Macdonough P, Gaidhane M, et al. Multimodality endoscopic treatment of pancreatic duct disruption with stenting and pseudocyst drainage: how efficacious is it? Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:129–33. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumonceau JM, Macias-Gomez C. Endoscopic management of complications of chronic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7308–15. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i42.7308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smoczyński M, Marek I, Dubowik M, et al. Endoscopic drainage/debridement of walled-off pancreatic necrosis – single center experience of 112 cases. Pancreatology. 2014;14:137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron TH. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic fluid collections and pancreatic necrosis. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;6:91–9. doi: 10.1016/s1052-5157(03)00100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhasin DK, Rana SS, Nanda M, et al. Comparative evaluation of transpapillary drainage with nasopancreatic drain and stent in patients with large pseudocysts located near tail of pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:772–6. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baron TH, Harewood GC, Morgan DE, Yates MR. Outcome differences after endoscopic drainage of pancreatic necrosis, acute pancreatic pseudocysts, and chronic pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:7–17. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]