Abstract

Background:

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most important diseases related with endocrines. Its main manifestation includes abnormal metabolism of carbohydrates and lipids and inappropriate hyperglycemia that is caused by absolute or relative insulin deficiency. It affects humankind worldwide.

Objectives:

Our research was aimed to observe antihyperglycemic activity of thymoquinone and oleuropein.

Materials and Methods:

In this study, rats were divided into six groups, 6 rats in each. Diabetes was inducted by streptozotocin (STZ). The level of fasting blood glucose was determined for each rats during the experiment, doses of thymoquinone and oleuropein (3 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg) for both, were injected intraperitoneal. Pancreatic tissues were investigated to compare β-cells in diabetic and treated rats.

Result and Conclusion:

It was found that thymoquinone and oleuropein significantly decrease serum Glucose levels in STZ induced diabetic rats.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, oleuropein, streptozotocin, thymoquinone

INTRODUCTION

The increasing number of the aging population, consumption of high-calorie value diet, obesity and sedentary lifestyle has significantly increased number of diabetics worldwide generally and particularly among Saudis.[1] Diabetes mellitus (DM) is characterized by increased plasma glucose concentrations resulting from absolute or relative deficiency of insulin, insulin resistance, or both, leading to metabolic abnormalities in carbohydrates characterized by hyperglycemia.[2] DM is also associated with enhanced production of free radicals that further complicates the condition leading to oxidative stress, cardiovascular abnormalities, renal failure, neurodegeneration, and immune dysfunction.[3] Type I DM is notorious to damage irreversibly the pancreatic β islets, which produce insulin. Prevention and control of DM is a major challenge and requires a change in lifestyle towards more physical activity and low-calorie intake avoiding sedentary habits. However, many people find it difficult to change their lifestyle and search for easy alternatives. Some traditional constituents of food that can reduce appetite, glucose absorption from gastrointestinal tract, glucose synthesis in liver, serum glucose level, body weight, and can augment glucose induced secretion of insulin from β islets in pancreas, may prove to be useful for prevention and control of DM.[4] Use of antioxidant-rich diet may improve antioxidant defense mechanism and protect against oxidative damage caused by free radicals.[5] During the past few years, some of the newly discovered bioactive drugs isolated from glucose reducing plants have shown antihyperglycemic activity with promising efficacy comparable to currently available oral hypoglycemic agents used in clinical therapy.[6] World Health Organization recommends that people must use traditional medicine to satisfy their principal health needs.[7] It is reported that a great number of medicinal plants are in use to control the DM.[8,9]

Nigella sativa L. belongs to family Ranunculaceae and different parts of plant are in use for medicinal purposes to cure various diseases.[10] N. sativa (of the family Ranunculaceae) is a plant that is synonymous with nigella cretica and is commonly known as black cumin, fennel flower, or nutmeg flower despite being unrelated to the common cumin (Cuminum Cyminum), fennel (Foeniculumvulgare), and nutmeg (the Myristica genus). Other names of the plant include Kalonji seeds.[11] And Ajaji, black caraway seed, and HabbatuSawda.[12] It appears to be a fairly well regarded medicinal herb, with some religious usage calling it the remedy for all diseases except death' (prophetic hadith),[13] and Habatul Baraka “The Blessed Seed”.[12] The seeds are the main medicinal component, although a seed oil taken from the seeds (black cumin oil or black seed oil) also possess the same bioactives. The currently available literature reports that the plant is having antioxidant activity due to presence of bioactive molecules which are mainly concentrated in fixed or essential oil including tocopherols, phytosterols, polyunsaturated fatty acids, thymoquinone, ρ-cymene, carvacrol, t-anethole and 4-terpineol.[14] Several studies on the hypoglycemic effect of N. sativa and thymoquinone in diabetic animals have shown positive results.[15]

Thymoquinone has demonstrated to contain strong antioxidant properties.[16] Moreover, suppresses expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in rat macrophages.[17]

Since long olive tree (Olea europaea L.) leaves have been widely used in treatments in European and Mediterranean countries. They have been used in the human foods as extracts, herbal teas, and powder and contain many potentially bioactive compounds that may possess antioxidant, antihypertensive, antiatherogenic, anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic, and hypocholesterolemic properties.[18] The bioactivity of olive tree byproduct extracts may be related to antioxidant and phenolic components such as oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, oleuropein aglycone, and tyrosol.[19] Many studies have shown that oleuropein main constituent of olive leaf extract (up to 6–9% of dry matter in the leaves) have a wide range of pharmacologic and health-promoting properties.[20] Specially, oleuropein has been related to improved glucose metabolism. It is also reported to possess an antihyperglycemic effect in diabetic rats.[21,22] The hypoglycemic and antioxidant effects of oleuropein have been reported in alloxan-diabetic rabbits.[23] In streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats, olive leaf extract has decreased serum concentrations of glucose, lipids, uric acid, creatinine, and liver enzymes.[24] The mechanism through which olive leaf extract reduces hyperglycemia is still not well-recognized.[23]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of plant material

Leaves of O. europaea L. (IDC4.3). Family oleaceae cultivated in Rafha, KSA were collected in October, 2014 from the gardens of Rafha. The plant was identified and authenticated by Department of Natural Products and Alternative Medicine Faculty of Pharmacy, Northern Border University. The active constituents of olive leaf have a wide number of ingredients with the chief constituent oleuropein (60–90 mg/g).[25]

The air-dried powder of O. europaea L. leaves was extracted by percolation with 70% Ethyl alcohol. The combined ethanolic extracts were concentrated under vacuo at 40°C to dryness. The concentrated ethanolic extract was suspended in distilled water and defatted with hexane then with ethyl acetate to give crude ethyl acetate extract rich in oleuropein.

N. sativa (IDC 221.5) seeds were purchased from Al Qassim area, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. These were identified and authenticated by Department of Natural Products and Alternative Medicine Faculty of Pharmacy, Northern Border University.

The essential oil of N. sativa seeds was prepared by hydrodistillation using standard method according to Saudi Pharmacopoeia (Clevenger). The obtained oil was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and stored at 20°C in a dark bottle until to analysis.

The volatile oil was analyzed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis and the identification of its components was done by comparing their retention times and mass fragmentation pattern to those of the available reference samples and or Wiley's mass spectral database in addition to the published ones.[26] The percentage composition of the essential oil components was determined by computerized peaks area measurements.

STZ was obtained commercially from Sigma-Aldrich Co. Germany, for induction of DM in experimental animals.

Experimental animals

Adult male Wistar rats (body weight range 250–300 g), 10–11 weeks of age, were obtained from the Animal House of King Fahd Medical Research Center, King Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. They were housed and maintained at 22°C under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, with free access to food and water.

Induction of diabetes

The rats were made to fast overnight before the induction of diabetes by a single intraperitoneal injection of 60 mg/kg STZ freshly dissolved in distilled water.[27] Hyperglycemia was confirmed 4 days after injection by measuring the tail vein blood glucose level with an Accu-Check Sensor Comfort glucometer. Only the animals with fasting blood glucose levels ≥250 mg/dl were selected for the study.

Experimental design

In this study, total 36 rats were used out of which 30 were diabetic, and 6 were normal. They were divided into 6 groups, 6 in each as follows: Group 1 was control group given only normal saline, without induction of diabetes and given normal diet. Group 2 with STZ but without any treatment (control diabetic) and given the same diet for group one. Group 3 was given STZ and treated with 3 mg/kg oleuropein. Group 4 was given STZ and treated with 5 mg/kg Oleuropein. Group 5 was given STZ and treated with 3 mg/kg thymoquinone. Group 6 was given STZ and treated with 5 mg/kg. Treatments were given for 56 days by intraperitoneal injections.

Blood glucose was determined using glucose (hk) assay kit Sigma-Aldrich Co. Germany.

Histopathological examination

The expert histopathologist at King Fahad Medical Research Center, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, performed the histological examination. The experimental animals were euthanized with a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital, and histological samples of pancreas were fixed. Hematoxylin and eosin stain technique was used to stain the histopathology slides. Under the microscope, number and status of β islets of Langerhans were observed.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) Statistical analysis of data for blood glucose was performed one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post-hoc test was used to compare differences among the experimental groups The statistical analysis was performed using statistical package (IBM Corp. Released 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

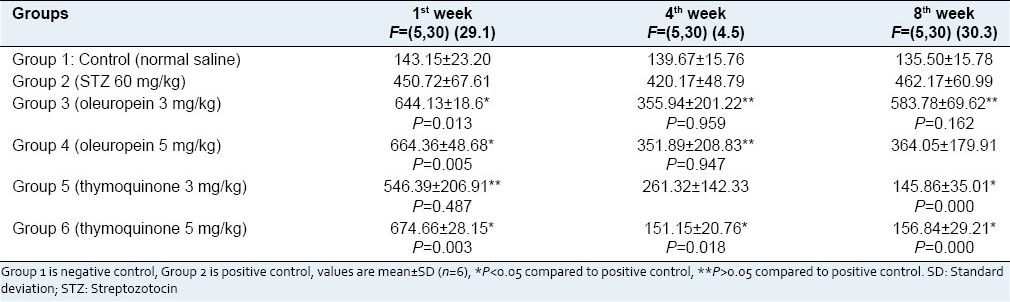

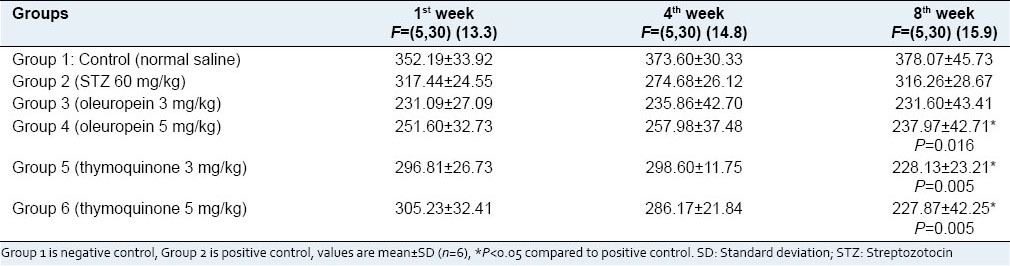

The effect of oleuropein and thymoquinone on blood glucose was presented as mean values ± SD in Table 1.

Table 1.

Fasting blood glucose (mg/dl) levels in experimental rats

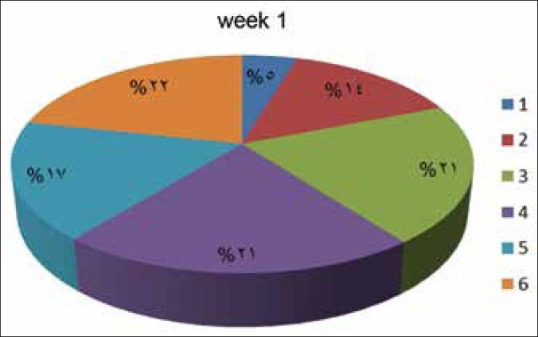

The negative control (nondiabetic) and positive control (diabetic) group showed a change in blood glucose levels during experiment time there was an increase in the positive control group [Figure 4].

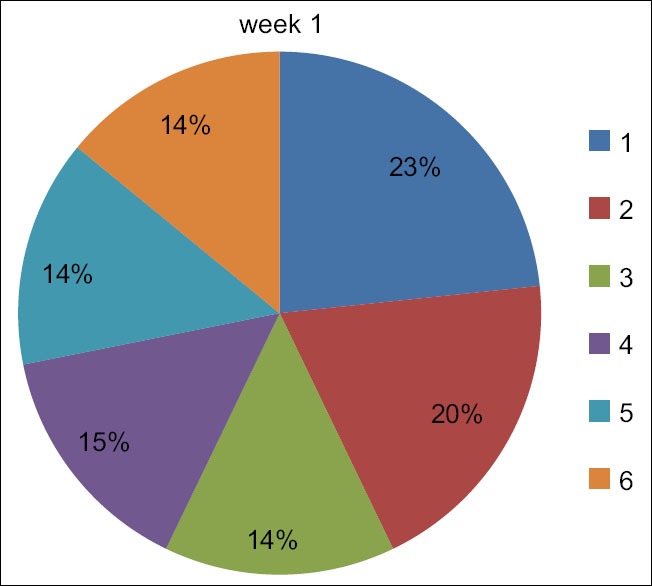

Figure 4.

Effect of oleuropein and thymoquinone on percentage change in blood glucose levels among experimental Groups (1–6) in week 1

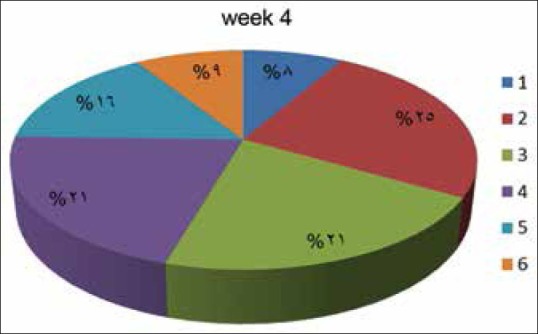

On the 1st and the 8th week, there was a gradual increase in blood glucose mean values ± SD levels due to the administration of STZ (451 mg/dl) and (462 mg/dl), respectively. The mean ± SD of blood glucose concentration in Group 5 (3 mg/kg TQ) decreased in the 8th week, and in Group 6 (5 mg/kg TQ) decreased in the 4th week. It indicates that 5 mg dose is more effective in decreasing STZ-induced hyperglycemia. Moreover, this result was significant when compared to positive control group P < 0.05 [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

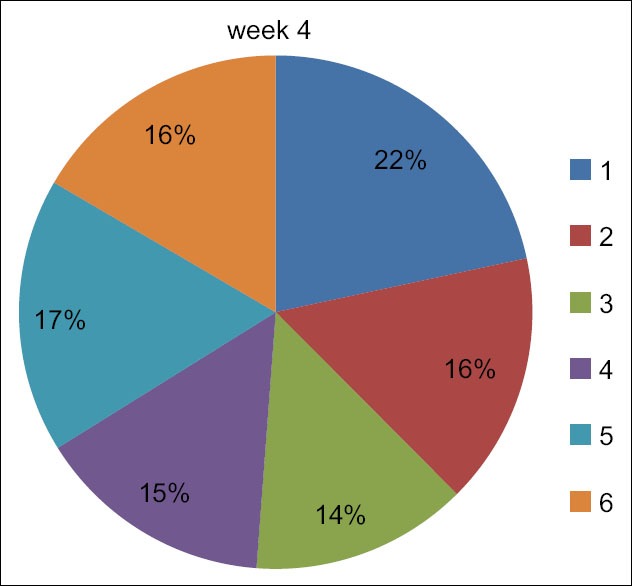

Effect of oleuropein and thymoquinone on percentage change in blood glucose levels among experimental Groups (1–6) in week 4

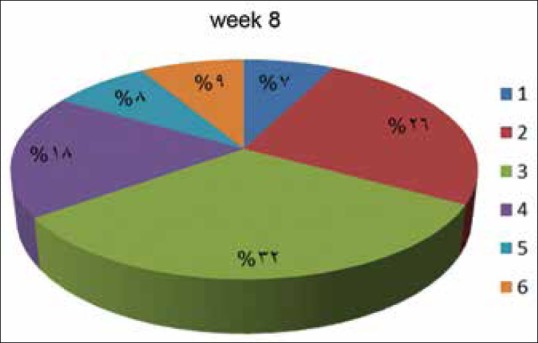

The mean ± SD of blood glucose concentration in Group 3 (oleuropein 3 mg/kg) decreased in the 4th week and increased in the 2nd week and this was significant compared to the control positive group P < 0.05 regarding Group 4 (oleuropein 5 mg/kg) there was a decrease in blood glucose concentration in the 4th week [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Effect of oleuropein and thymoquinone on percentage change in blood glucose levels among experimental Groups (1–6) in week 8

Table 2 shows the mean body weight ± SD of all experimental groups. There was a significant decrease in the weight compared to the duration. An increase in the body weight for the positive control (diabetic) group in the week 8 was observed [Figure 7–9].

Table 2.

Body weight expressed in grams for the experimental groups

Figure 7.

Effect of oleuropein and thymoquinone on percentage change in weight among experimental Groups (1–6) in week 1

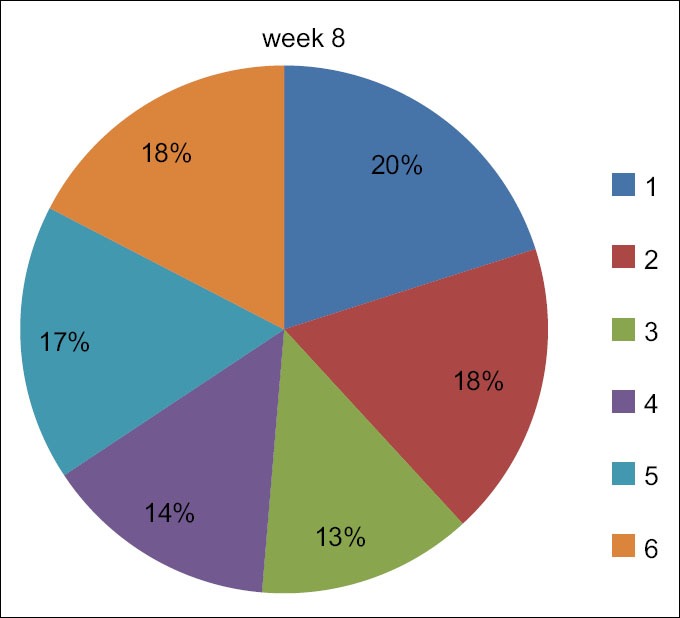

Figure 9.

Effect of oleuropein and thymoquinone on percentage change in weight among experimental Groups (1–6) in week 8

Figure 8.

Effect of oleuropein and thymoquinone on percentage change in weight among experimental Groups (1–6) in week 4

DISCUSSION

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic systemic disease characterized by hyperglycemia. Oxidative stress is thought to increase in a system where the rate of free radical production increases, and/or the antioxidant mechanisms are impaired. In recent years, the oxidative stress-induced free radicals have been implicated in the pathology of insulin dependent DM.[16,28,29]

In the present research, we tried to see the effect of thymoquinone and oleuropein in STZ induced DM in rats. Results of this study showed that diabetic rats exhibited a significant increase in blood glucose level after injection of STZ. This is similar with the researches that have been done throughout the world for induction of diabetes.[27]

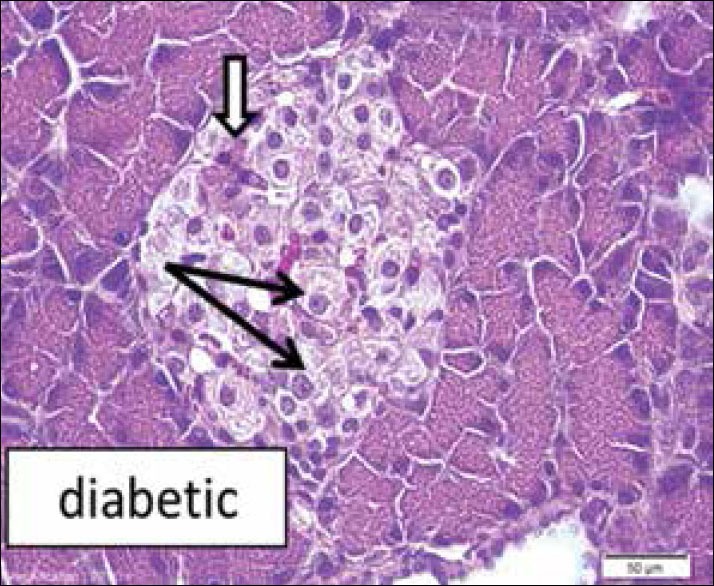

In this study, we used STZ (60 mg/kg), which has been used by many researchers to induce experimental diabetes.[27] A study on the induction of diabetes by STZ in rats showed that after 3 days, a dose of 60 mg/kg STZ made the pancreas swell and degeneration in the β-cells leading to experimental diabetes in rats [Figure 1].[30]

Figure 1.

Diabetic rat pancreas (H and E ×10) shows apparent decrease in cell density. Beta cells looked enlarged with faint stained cytoplasm or vacuoles (black arrows) indicate less insulin content, few cells looked dark and degenerated (white arrows)

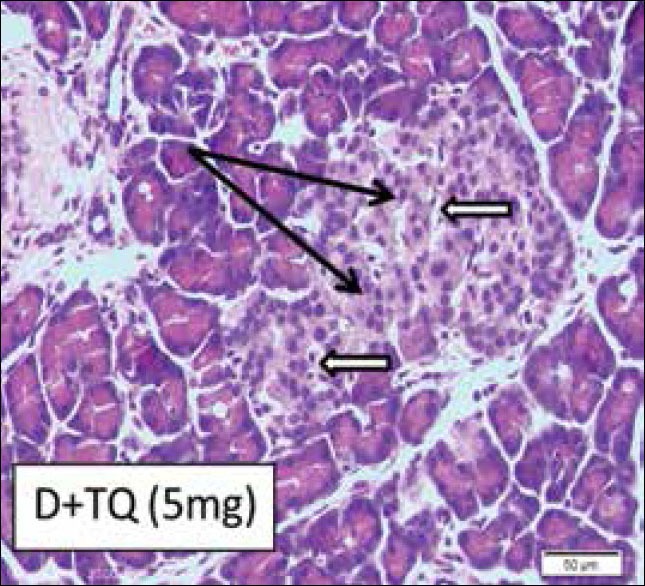

As insulin is the main, recognized hormone that keeps the serum glucose levels in normal range. The normal function of insulin-releasing cells (β-cells in the pancreas), as well as other cellular mechanisms, are distorted by oxidative stress, which would contribute in the induction of DM.[31,32] In our study, we found that 5 mg/kg dose of thymoquinone showed a significant hypoglycemic effect in STZ-induced diabetic rats by decreasing the fasting blood glucose levels which are in agreement with Alimohammadi et al.[27] The most probable mechanism of the effect may be the preservation of β-cells in the pancreas as was found in the histopathological examination, shown in the [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Diabetic rat pancreas (H and E ×10) treated with thymoquinone 5 mg (Group 6). Nearly normal density of beta cells (arrows) in the central region of islets

Several studies support the fact that olive leaf extracts are rich in oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol and these compounds confer the antioxidant activities to the olive leaves.[19] Thus, these phenolic compounds could prove to be beneficial in the protection against metabolic diseases associated with oxidative stress such as diabetes.[20]

In the present study, we found a significant decrease in blood glucose level in the 4th week with 3 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg of oleuropein.

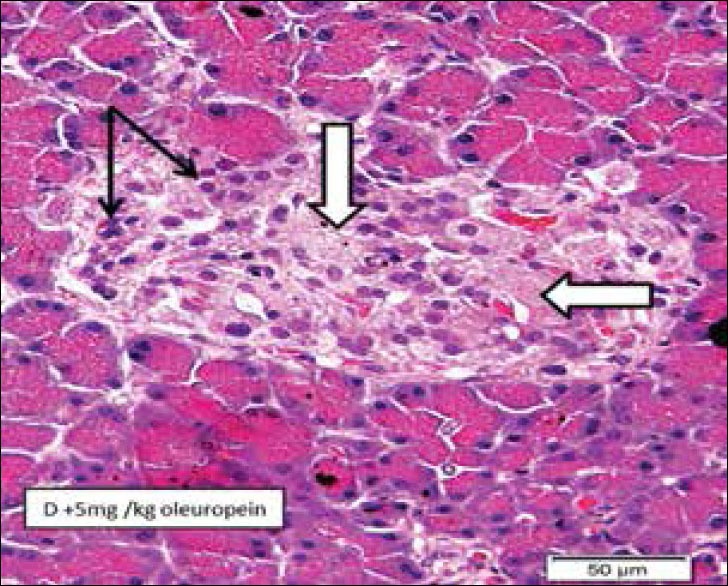

In the previous studies two possible mechanisms have been suggested to explain the hypoglycemic effect of the olive leaf extract, oleuropein:[33] (1) Improved glucose-induced insulin release, and (2) increased peripheral uptake of glucose. It has been observed that oleuropein in olive leaves has been shown to accelerate the cellular uptake of glucose, leading to reduced plasma glucose. As oleuropein has been found to be a glycoside, that potentially accesses a sodium-dependent glucose transporter (SGLT1) found in the epithelial cells of the small intestine, to get its entry into the cells. Experimental data indicated an interaction between dietary flavonolmonoglucosides with the intestinal SGLT1 and inhibited Na-independent glucose uptake. Other mechanism through which olive leaf extract might produce its hypoglycemic effect is through the inhibition of pancreatin amylase activity.[33] As glucose-induced release of insulin is directly proportional to preservation of β islets in the pancreas and histopathological examination [Figure 3] shows no improvement in the damage to the β islets caused by STZ, after treatment with olive leaf extract so this mechanism cannot be associated with hypoglycemic effect of olive leaf extract.

Figure 3.

Diabetic rat pancreas (H and E ×10) treated 5 mg oleuropein (Group 4) showing islets of Langerhans with regions of fibrosis (white arrows) indicating loss of beta cells. Many cells showed small degenerated nuclei (black arrows)

Our results and findings are in agreement with other findings regarding the hypoglycemic effect of oleuropein. It has been observed that decreased activities of hepatic antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase and catalase found in diabetic rats were restored by the use of oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol, thereby attenuating the oxidative stress associated with diabetes.[34]

The intraperitoneal injections of thymoquinone caused peritoneal inflammation in the experimental rats along with an increase in the weight and size of the liver.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the findings of this study, it was revealed that intraperitoneal administration of N. sativa (thymoquinone) significantly decreases hyperglycemia in STZ-induced DM in the rats. However, it was also observed that intraperitoneal administration of thymoquinone also produced peritonitis and hepatomegaly in the experimental animals. A reduction in glucose levels was also found with olive leaf extract oleuropein.

It is suggested that, further studies with larger sample size and different parameters will be helpful to determine exact antidiabetic dose, its mechanism of action and safer route of administration especially for thymoquinone as it is having a potential to be used as hypoglycemic agent in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The research project was approved and funded by Deanship of Scientific Research, Northern Border University, Saudi Arabia; grant NO. (3-109-435) in 2014–2015.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The research project was approved and funded by Deanship of Scientific Research, Northern Border University, Saudi Arabia; grant NO. (3-109-435) in 2014–2015

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vats V, Yadav SP, Grover JK. Ethanolic extract of Ocimum sanctum leaves partially attenuates streptozotocin-induced alterations in glycogen content and carbohydrate metabolism in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iso H, Date C, Wakai K, Fukui M, Tamakoshi A. the relationship between green tea and total caffeine intake and risk for self-reported type 2 diabetes among Japanese adults. Diabetes Care. 2006;144:554–62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung HY, Qian K, Morris-Natschke SL, Hsu CS, Lee KH. Recent discovery of plant-derived anti-diabetic natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:580–606. doi: 10.1039/c2np00074a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathur ML, Gaur J, Sharma R, Haldiya KR. Antidiabetic properties of a spice plant Nigella sativa. J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guarrera PM, Savo V. Perceived health properties of wild and cultivated food plants in local and popular traditions of Italy: A review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;146:659–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marles RJ, Farnsworth R. Plants as sources of antidiabetic agents. Econ Med Plants Res. 1994;6:149–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bavarva JH, Narasimhacharya AV. Antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of Costus speciosus in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Phytother Res. 2008;22:620–6. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maghrani M, Michel JB, Eddouks M. Hypoglycaemic activity of Retama raetam in rats. Phytother Res. 2005;19:125–8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrade-Cetto A, Becerra-Jiménez J, Martínez-Zurita E, Ortega-Larrocea P, Heinrich M. Disease-Consensus Index as a tool of selecting potential hypoglycemic plants in Chikindzonot, Yucatán, México. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tauseef Sultan M, Butt MS, Anjum FM. Safety assessment of black cumin fixed and essential oil in normal Sprague Dawley rats: Serological and hematological indices. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:2768–75. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qidwai W, Hamza HB, Qureshi R, Gilani A. Effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of powdered Nigella sativa (kalonji) seed in capsules on serum lipid levels, blood sugar, blood pressure, and body weight in adults: Results of a randomized, double-blind controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:639–44. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gali-Muhtasib H, El-Najjar N, Schneider-Stock R. The medicinal potential of black seed (Nigella sativa) and its components. Adv Phytomed. 2006;2:133–53. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad A, Husain A, Mujeeb M, Khan SA, Najmi AK, Siddique NA, et al. A review on therapeutic potential of Nigella sativa: A miracle herb. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2013;3:337–52. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butt MS, Sultan MT. Nigella sativa: Reduces the risk of various maladies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010;50:654–65. doi: 10.1080/10408390902768797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bamosa AO. A review on the hypoglycemic effect of Nigella sativa and thymoquinone. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2015;3:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houghton PJ, Zarka R, de las Heras B, Hoult JR. Fixed oil of Nigella sativa and derived thymoquinone inhibit eicosanoid generation in leukocytes and membrane lipid peroxidation. Planta Med. 1995;61:33–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Mahmoudy A, Matsuyama H, Borgan MA, Shimizu Y, El-Sayed MG, Minamoto N, et al. Thymoquinone suppresses expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in rat macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:1603–11. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El SN, Karakaya S. Olive tree (Olea europaea) leaves: Potential beneficial effects on human health. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:632–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Visioli F, Poli A, Gall C. Antioxidant and other biological activities of phenols from olives and olive oil. Med Res Rev. 2002;22:65–75. doi: 10.1002/med.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briante R, Patumi M, Terenziani S, Bismuto E, Febbraio F, Nucci R. Olea europaea L. leaf extract and derivatives: Antioxidant properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:4934–40. doi: 10.1021/jf025540p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez M, Zarzuelo A, Gamez MJ, Utrilla MP, Jimenez J, Osuna I. Hypoglycemic activity of olive leaf. Planta Med. 1992;58:513–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-961538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jemai H, El Feki A, Sayadi S. Antidiabetic and antioxidant effects of hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein from olive leaves in alloxan-diabetic rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:8798–804. doi: 10.1021/jf901280r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Azzawie HF, Alhamdani MS. Hypoglycemic and antioxidant effect of oleuropein in alloxan-diabetic rabbits. Life Sci. 2006;78:1371–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eidi A, Eidi M, Darzi R. Antidiabetic effect of Olea europaea L. in normal and diabetic rats. Phytother Res. 2009;23:347–50. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Tutour B, Guedon D. Antioxidant activities of Olea europaea leaves and related phenolic compounds. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:1173–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams RP. Identification of Essential Oils by Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry. San Diego, New York, Berkeley, Boston, London, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto: Academic Press, Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alimohammadi S, Hobbenaghi R, Javanbakht J, Kheradmand D, Mortezaee R, Tavakoli M, et al. Protective and antidiabetic effects of extract from Nigella sativa on blood glucose concentrations against streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic in rats: An experimental study with histopathological evaluation. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:137. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28.Al-Hader A, Aqel M, Hasan Z. Hypoglycemic effect of the volatile oil of Nigella sativa seeds. Int J Pharmacogn. 1993;31:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Bremen T, Drömann D, Luitjens K, Dodt C, Dalhoff K, Goldmann T, et al. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (Trem-1) on blood neutrophils is associated with cytokine inducibility in human E. coli sepsis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akbarzadeh A, Norouzian D, Mehrabi MR, Jamshidi Sh, Farhangi A, Verdi AA, et al. Induction of diabetes by Streptozotocin in rats. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2007;22:60–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02913315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baynes JW. Role of oxidative stress in development of complications in diabetes. Diabetes. 1991;40:405–12. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szaleczky E, Prechl J, Fehér J, Somogyi A. Alterations in enzymatic antioxidant defence in diabetes mellitus – A rational approach. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:13–7. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.75.879.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wainstein J, Ganz T, Boaz M, Bar Dayan Y, Dolev E, Kerem Z, et al. Olive leaf extract as a hypoglycemic agent in both human diabetic subjects and in rats. J Med Food. 2012;15:605–10. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El-Amin M, Virk P, Elobeid MA, Almarhoon ZM, Hassan ZK, Omer SA, et al. Anti-diabetic effect of Murraya koenigii (L) and Olea europaea (L) leaf extracts on streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2013;26:359–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]