Abstract

Objective

To translate, adapt, and test the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Korean version of the Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ) and the Shoulder Rating Questionnaire (SRQ).

Methods

The international guideline for the adaptation of questionnaires was referenced for the translation and adaptation of the original SDQ and SRQ. Correlations of the SDQ-K and SRQ-K with the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) were assessed to determine the reliability and validity of the questionnaires. To evaluate reliability, surveys were performed at baseline and a mean of 6 days later in 29 subjects who did not undergo any treatment for shoulder problems. To evaluate responsiveness, assessments were performed at baseline with 4-week intervals in 23 subjects with adhesive capsulitis who were administered triamcinolone injection into the glenohumeral joint.

Results

Fifty-two subjects with shoulder-related problems were surveyed. Cronbach alpha for internal consistency was 0.82 for the summary SDQ-K and 0.75 for the summary SRQ-K. The test-retest reliability of the SDQ-K, SRQ-K, and domains of the SRQ-K ranged from 0.84 to 0.95. The SDQ-K and SRQ-K summary scores correlated well with the SPADI and NRS summary scores. Generally, the effect sizes and standardized response means of the summary scores of the SDQ-K, SRQ-K, and domains of the SRQ-K were large, reflecting their responsiveness to clinical changes after treatment.

Conclusion

The reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the SDQ-K and SRQ-K were excellent. The SDQ-K and SRQ-K are feasible for Korean patients with shoulder pain or disability.

Keywords: Disability evaluation, Questionnaires, Shoulder, Translations, Validation studies

INTRODUCTION

The shoulder joint has the largest range of motion (ROM) in the human body and is affected by many diseases. Most shoulder joint diseases cause pain and functional impairment, and patients with shoulder disease may have difficulties in their activities of daily living (ADL) such as work, housekeeping, and recreational activities [1]. Adhesive capsulitis and rotator cuff disorder are the most common causes of shoulder joint pain in the adult population.

The assessment of function in patients with shoulder disorders is essential for the treatment and evaluation of treatment outcomes. Nowadays, there are many scoring systems and questionnaires to assess shoulder joint function, which have been assessed in variable groups of patients [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Of these, Roach et al. [5] developed the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) for the assessment of patients with shoulder pain. The SPADI was translated into Korean, and its validity and reliability were assessed [14]. However, there are still few Korean versions of questionnaires for the evaluation of shoulder pain and function in the clinical setting in South Korea. Before using questionnaires in subjects speaking different languages, appropriate translation taking different language and cultural characteristics into consideration, adaptation, and assessment of the reliability and validity must be performed [15]. Thus, we planned the translation, adaptation, and assessment of other questionnaires in English that are used worldwide. In the present study, two self-reported questionnaires that are focused on the assessment of pain and function in subjects with shoulder complaints were evaluated. The Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ) and the Shoulder Rating Scale (SRQ) were chosen because a previous study of the Dutch SDQ, United Kingdom SDQ, the SPADI, and the SRQ showed that the summary scores of these 4 questionnaires have a substantial intercorrelation [16]. The Constant-Murley scale was excluded because it is focused on objective evaluation parameters that place more emphasis on ROM than pain and function, and it is not a disability scale [17]. One of the most important processes during the translation and adaptation of questionnaires is to compare the questionnaire with other scales or questionnaires with proven validity and reliability. Because of the absence of such a questionnaire in South Korea for shoulder pathology except for the Korean version of the SPADI (SPADI-K), the correlation of the Korean version of the SDQ and SRQ (SDQ-K and SRQ-K) with the SPADI-K and Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) was evaluated. The shoulder ROM was excluded because previous studies have not shown sufficient evidence for significant correlation between function and ROM. Furthermore, ROM is not sensitive for detection of the disability associated with the shoulder disorder [10,16].

The purpose of this study was to translate and adapt the original SDQ and SRQ into the Korean language version and evaluate its internal consistency, reliability, validity, and responsiveness to clinical change in patients with shoulder pain or disability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and design

This was a prospective study. The data were collected from 52 subjects who visited the outpatient clinic of the department of rehabilitation for shoulder joint pain or limitation of function from March 2014 to September 2014. Inclusion criteria were the following: 1) age ≥20 years, 2) shoulder pain or limitation of function persisting over 1 month, 3) proficiency in Korean, and 4) no significant cognitive impairment. Exclusion criteria were subjects with cerebral infarction, peripheral neuropathy, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, ankylosing spondylitis, metastatic cancer, hemophilia, multiple sclerosis, history of fracture or surgery in the affected shoulder, and wound or skin defect in the affected shoulder.

Subjects were divided into two groups: those who did not undergo any treatment for shoulder problems for analysis of test-retest reliability (29 subjects) and those who underwent specific intervention for shoulder problems for analysis of responsiveness (23 subjects). All subjects completed the SDQ-K, SRQ-K, SPADI-K, and NRS twice: at baseline and follow-up (the 29 subjects who did not undergo any treatment revisited after a mean of 6 days [range, 0-21 days], and the 23 subjects who underwent specific intervention for shoulder problems with 4-week intervals). A rehabilitation specialist evaluated and diagnosed shoulder-related problems in all subjects, which involved history taking, physical examination, and image review such as conventional radiography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the shoulder. Adhesive capsulitis was diagnosed when the subject had passive and active ROM limitation at the same time. Subjects with calcific depositions in plain radiography were diagnosed as calcific tendinitis. Rotator cuff tear was diagnosed if they had partial or full thickness tear on ultrasound or MRI. Acromioclavicular or glenohumeral (GH) joint osteoarthritis was diagnosed if they had significant degenerative lesions on conventional radiography. The most common cause of shoulder problems was adhesive capsulitis (42/52, 80.8%), followed by rotator cuff tear and impingement syndrome (6/52, 11.5%), calcific tendinitis (2/52, 3.8%), osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular joint (1/52, 1.9%), and superior labral tears from anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesion (1/52, 1.9%). All subjects who underwent specific intervention for shoulder problems had adhesive capsulitis. Demographic and clinical characteristics were recorded by history taking and physical examination. For the measurement of the NRS, all subjects were educated to describe pain intensity on a 10-point scale in which '0' is no pain and '10' is the most intense pain imaginable.

Translation and adaptation

Before translating the original SDQ and SRQ, permission was obtained by email from the authors of the original studies.

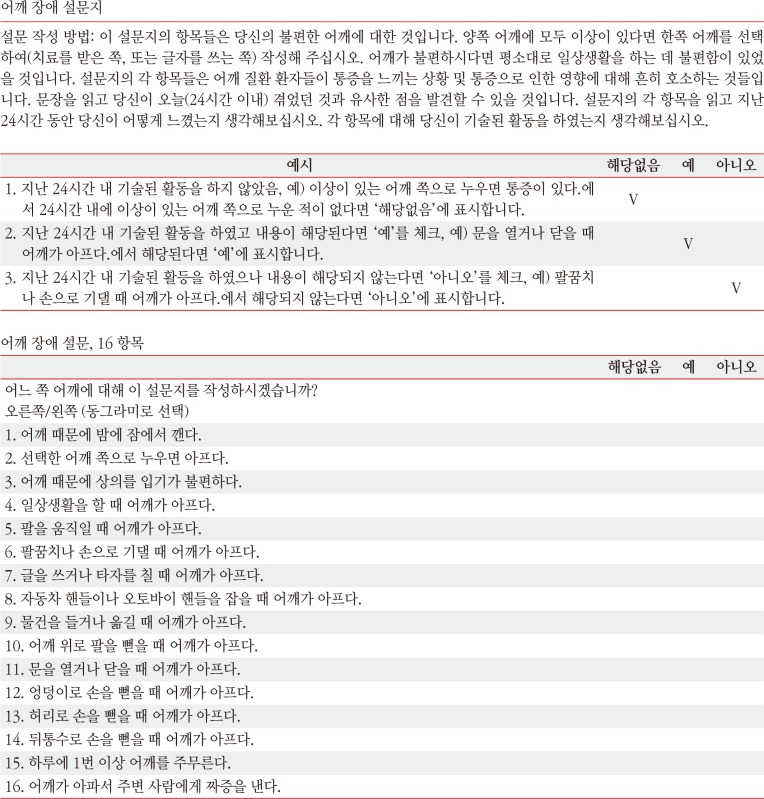

The SDQ was developed by van der Heijden et al. [2] for the evaluation of change over time in pain-associated disability of patients with shoulder disorders. The SDQ seems to be sensitive for detecting clinical changes, and its responsiveness was evaluated in a randomized clinical trial [18]. The usefulness of the SDQ for cross-sectional discriminative aims has also been assessed [19]. It is an easy to comprehend, reliable, and valid self-administered questionnaire that does not require special instruments for its application. The SDQ includes 16 questions describing common situations that may cause symptoms in patients who have shoulder problems. All questions of the SDQ apply to the preceding 24 hours. Answers are 'yes', 'no', or 'not applicable'. The answer 'not applicable' must be chosen when the situation has not happened during the past 24 hours. The final SDQ score is calculated by dividing the number of 'yes' by the total number of applicable answers, and multiplying this score by 100. The SDQ score can range from 0 to 100 with a higher score meaning more severe condition [2].

The SRQ was developed by L'Insalata et al. [3] for the assessment of function in patients with shoulder disorders. The authors performed validation by correlating the scores of the SRQ with the domains of the arthritis impact measurement scale. The reliability was assessed in 40 patients who repeated the SRQ after a mean of 3 days. The test-retest reliability of the summary scale and its subscales was evaluated using the Spearman-Brown test. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used as an additional measurement of the test-retest reliability. The SRQ is a self-administered questionnaire that not only includes domains on pain, improvement and satisfaction, global assessment, and areas for daily activities, but also includes 2 additional domains: work and sports/recreational activities. The SRQ consists of 7 domains with 21 questions. The work domain includes a non-graded question that categorizes the form of work (Question 15). The satisfaction domain (Question 20) and the importance domain (Question 21) are not included in the summary score. Five domains are graded respectively by averaging the scores of the questions and multiplying the averages by 1.5 or 2 and a weighting factor of each domain. The global assessment domain of the original version was 10-cm-long line visual analogue scale with the lower indicator as a severe pain. We modified this global assessment domain to a NRS in which the highest number indicates severe pain for the subject's convenience during translation. The maximum score was 15 points for the global assessment domain (subtract the value from 10 and multiply it by 1.5; range 0-15). Each of the other scored domains consisted of a series of multiple-choice questions with 5 selections scored from 1 (poorest) to 5 (best) based on an equal interval. Each domain was scored separately by averaging the scores of the completed questions and multiplying the average by 2. A suggested weighting system for the calculation of a summary score was developed by L'Insalata et al. [3] after consultation with several shoulder surgeons and patients regarding the relative importance of each of the domains in the original article. The maximum score is 40 points for the pain domain (multiplied by 2 and by a weighting factor of 4; range 8-40), 20 points for the ADL domain (multiplied by 2 and by a weighting factor of 2; range 4-20), 15 points for the sports/recreational activities domain (multiplied by 2 and a weighting factor of 1.5; range 3-15), and 10 points for the work domain (multiplied by 2 and by a weighting factor of 1; range 2-10). Therefore, the summary score can range from 17 to 100 points, and 17 is the most severe condition [3].

The English version of the SDQ and SRQ were translated into Korean by two physiatrist specialists whose first language was Korean, and the cross-cultural adaptation method of Beaton et al. [20] was referenced. The two physiatrist specialists only performed the translation and did not participate in the practice and survey. The two translated versions were reviewed, and a first draft version was made. This draft version was translated back into English by two native English speakers. These two back-translation versions were reviewed, and a second draft version was produced. The first and second draft versions were compared by members of a translation committee, and discrepancies were corrected. Subsequently, final editions of the Korean version of the SDQ and the SRQ were constructed (see Appendixes 1, 2).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 21.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All variables were assessed for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The internal consistency of the SDQ-K and the SRQ-K was evaluated using Cronbach coefficient alpha for the domains and summary scores. Construct validity between the SDQ-K summary score, the SRQ-K summary score, SPADI-K summary score, and NRS was tested using Spearman correlation coefficient. Although there are no standards for how high correlations must be between a new questionnaire and other questionnaires to set up construct validity, a value of 0.6 may be in favor of construct validity [21]. Test-retest reliability is a measure of the reproducibility of the questionnaire, that is, the ability to provide consistent scores over time in a stable population [22]. To assess test-retest reliability, the SPADI-K, NRS, SDQ-K, and SRQ-K of 29 subjects who did not undergo any treatment for shoulder problems were explored twice because no significant change is needed in the intervening period. The test-retest reliability was evaluated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). An ICC of 0.70 is regarded as sufficient for group comparisons, however, an ICC of >0.90 is required for individual comparisons [23]. ICCs were assessed for the summary scores of the SDQ-K, SRQ-K, and the global assessment, pain, ADL, sports/recreational activities, work domains of the SRQ-K. The SPADI-K, NRS, SDQ-K, and SRQ-K of 23 subjects with adhesive capsulitis who were treated with triamcinolone injection into the GH joint were explored twice with 4-week intervals, in order to assess responsiveness to clinical change. The changes were described as effect size (ES) and standardized response mean (SRM):

Cohen's interpretation of the ES (a value of 0.2 is small, 0.5 is moderate, and 0.8 is large) can also be referred to the SRM [24].

All the subjects provided informed consent to participate in this study. The study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital (IRB No. 2014-03-005).

RESULTS

Cronbach alpha for internal consistency of 52 subjects was 0.82 for the summary SDQ-K (0.80, 0.81, 0.81, 0.81, 0.81, 0.80, 0.80, 0.79, 0.81, 0.82, 0.81, 0.81, 0.82, 0.82, 0.81, and 0.80 after extraction of each question in sequence) and 0.75 for the summary SRQ-K (0.65, 0.82, 0.66, 0.73, and 0.71 after extraction of each domain of general assessment, pain, ADL, sports/recreational activities, and work in sequence). Cronbach alpha for internal consistency of 42 subjects with adhesive capsulitis was 0.81 for the summary SDQ-K (0.79, 0.80, 0.81, 0.80, 0.81, 0.80, 0.79, 0.78, 0.80, 0.82, 0.81, 0.82, 0.81, 0.81, 0.80, and 0.79 after extraction of each question in sequence) and 0.79 for the summary SRQ-K (0.70, 0.83, 0.71, 0.78, and 0.76 after extraction of each domain of general assessment, pain, ADL, sports/recreational activities, and work in sequence).

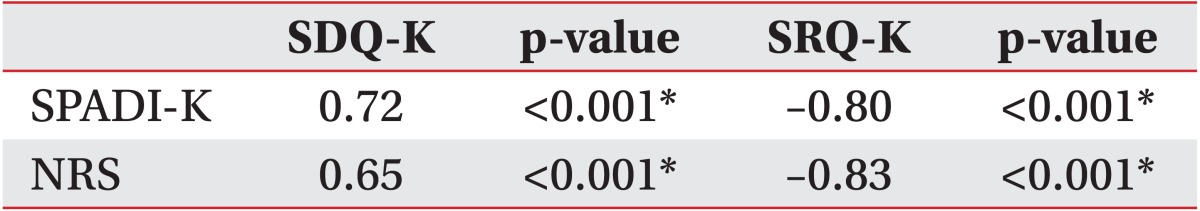

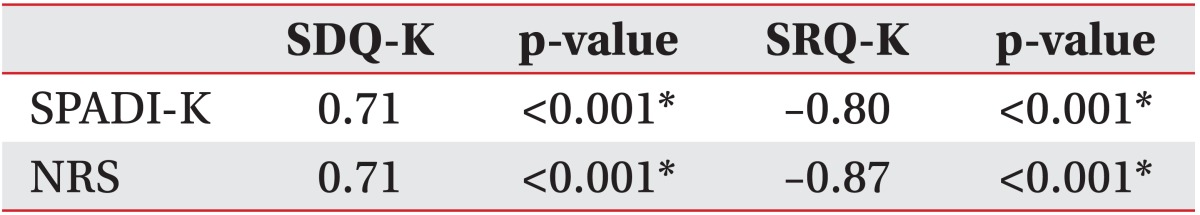

Spearman correlation coefficients of 52 subjects between the SDQ-K, SRQ-K, and SPADI-K, NRS were shown in Table 1. Generally, correlations of the SDQ-K and SRQ-K summary scores with the SPADI-K summary score and NRS were statistically significant and strong. Spearman correlation coefficients of 42 subjects with adhesive capsulitis between the SDQ-K, SRQ-K, and SPADI-K, NRS were shown in Table 2. The correlations of the SDQ-K and SRQ-K summary scores with the SPADI-K summary score and NRS were stronger than the former.

Table 1. Spearman correlation coefficients between the summary score of the SDQ-K, SRQ-K, SPADI-K, and NRS in 52 subjects with shoulder problems.

SDQ-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Disability Questionnaire; SRQ-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Rating Questionnaire; SPADI-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale.

*p<0.001 (derived from correlation analysis).

Table 2. Spearman correlation coefficients between the summary score of the SDQ-K, SRQ-K, SPADI-K, and NRS in 42 subjects with adhesive capsulitis.

SDQ-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Disability Questionnaire; SRQ-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Rating Questionnaire; SPADI-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Pain And Disability Index; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale.

*p<0.001 (derived from correlation analysis).

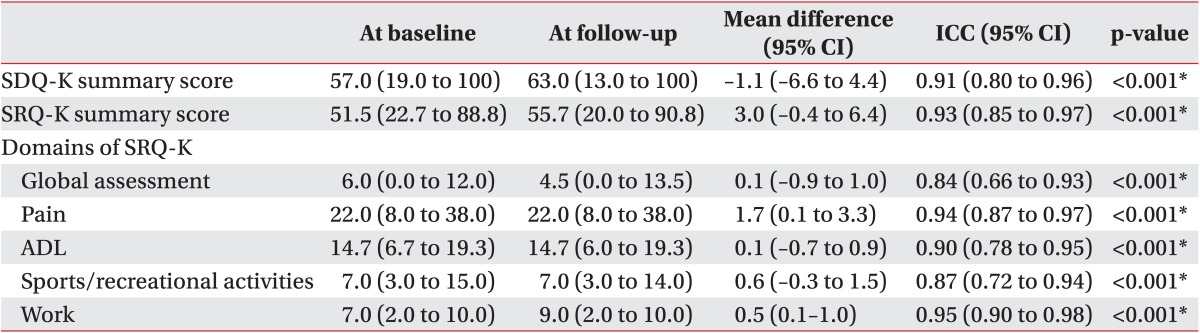

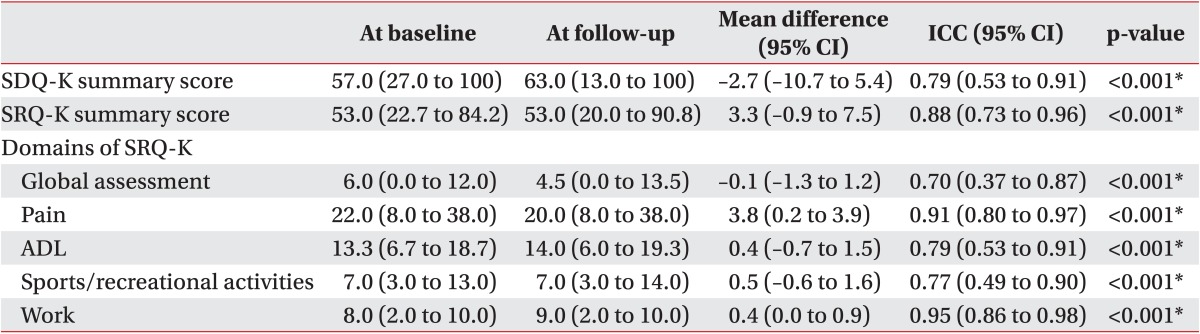

In the 29 subjects who did not undergo any treatment for shoulder problems, test-retest reliability of the SDQ-K, SRQ-K, and its domains was good to almost perfect (Table 3). ICCs for the SDQ-K summary score, SRQ-K summary score, and the domains of pain, ADL, and work of SRQ-K were almost perfect (all 0.90 or higher), while the ICCs for the domains of global assessment and sports/recreational activities were good at 0.84 and 0.87, respectively. In the 19 subjects with adhesive capsulitis who did not undergo any treatment, test-retest reliability of the SDQ-K, SRQ-K, and its domains was sufficient to almost perfect, but generally lower than the former (Table 4).

Table 3. Test-retest scores of the SDQ-K and SRQ-K to evaluate reliability in 29 subjects who did not undergo any treatment for shoulder problems.

Values are presented as mean (range).

SDQ-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Disability Questionnaire; SRQ-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Rating Questionnaire; CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; ADL, activities of daily living.

*p<0.001 (derived from reliability analysis).

Table 4. Test-retest scores of the SDQ-K and SRQ-K to evaluate reliability in 19 subjects with adhesive capsulitis who did not undergo any treatment.

Values are presented as mean (range).

SDQ-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Disability Questionnaire; SRQ-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Rating Questionnaire; CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; ADL, activities of daily living.

*p<0.001 (derived from reliability analysis).

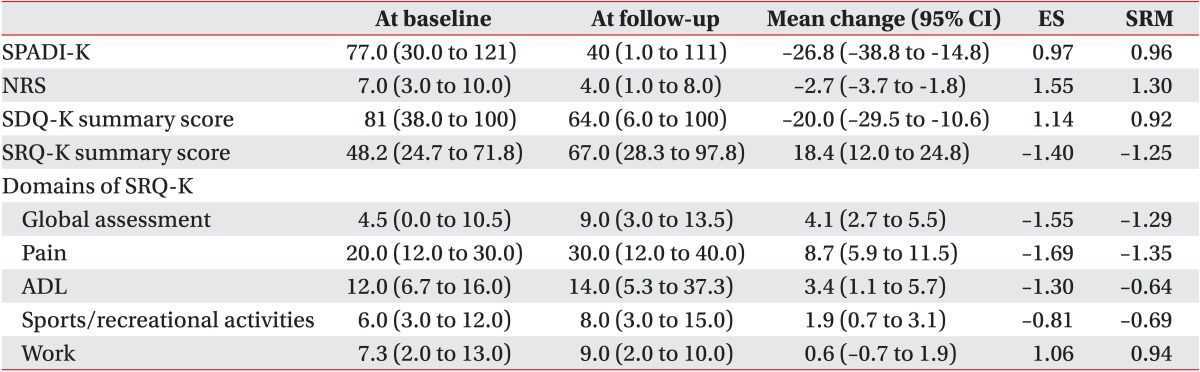

The ES and SRM of the SPADI-K, NRS, SDQ-K, and SRQ-K of 23 subjects with adhesive capsulitis who were treated with triamcinolone injection into the GH joint were good to excellent, indicating high sensitivity of detection of clinical change (Table 5). The SRM of the domains of ADL and sports/recreational activities of SRQ-K were moderate at -0.64 and -0.69, respectively.

Table 5. Scores at baseline and follow-up, mean change (SD), ES, SRM in 23 subjects who underwent triamcinolone injection into the GH joint.

Values are presented as mean (range).

SD, standard deviation; ES, effect size; SRM, standardized response mean; SDQ-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Disability Questionnaire; SRQ-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Rating Questionnaire; SPADI-K, Korean version of the Shoulder Pain And Disability Index; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; ADL, activities of daily living.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the translation and adaptation of the SDQ and SRQ into the Korean language appeared satisfactory. The internal consistency, validity, test-retest reliability, and responsiveness to clinical change of the SDQ-K and SRQ-K for the subjects with shoulder pain or disability were good and similar to the results of the original versions.

Previously, the SRQ was translated and adapted into Dutch [25], and the SDQ was translated and adapted into Turkish [17]. In these studies, the reliability and validity were good. This was the first time that the SDQ and the SRQ were translated and adapted into Korean. International guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures were referenced to maintain equivalence of the questionnaires in Korean [20].

In both the original and the present study, the Cronbach alpha of the SRQ was above the 0.70 threshold for the summary score and all domains. In both, the study by de Winter et al. [19] and the present study, the Cronbach alphas of the SDQ were above the 0.70 threshold.

In the present study, the significant correlation of the summary scores of the SRQ-K and SDQ-K with the SPADI-K and NRS indicated the ability of the SRQ-K and SDQ-K to measure shoulder pain or disability. Moreover, the overall responsiveness of the SRQ-K and SDQ-K were excellent.

In both, the original and present study, the test-retest reliabilities of the SRQ were good. In the SDQ, there is no data about reliability in the original study, however, in the study of the Turkish language version, the test-retest correlation coefficient was 0.88, which was similar to that found in the present study.

There has been some criticism regarding the lack of reliability of the SDQ and SRQ [23]. Desai et al. [23] reported no data to validate the reliability of the SDQ; in addition, the reliability of the SRQ was assessed in only 40 patients who repeated the SRQ after a mean of 3 days, and 3 days was insufficient for patients to forget their original score. In the present study, the reliability of the SDQ-K and SRQ-K was tested in only 29 subjects; however, they repeated the questionnaire after a mean of 6 days (0-21 days), and the ICCs were good to excellent.

Before the use of other questionnaires developed in foreign countries, we recommend referencing the international guidelines for cross-cultural adaptations of questionnaires, a process that seemed satisfactory in this study.

The major limitations of this study were the small sample size and concentration of the pathology of subjects. The most common pathology was adhesive capsulitis (80.8%). In another study, adhesive capsulitis was the most common pathology with an incidence of 63.6% among subjects [25]. Hence, the SRQ-K and SDQ-K may not accurately reflect the severity of other shoulder pathologies except for adhesive capsulitis. The internal consistency and correlations with SPADI-K and NRS in subjects with adhesive capsulitis were generally greater than those of the parent population, but the ICCs in subjects with adhesive capsulitis were generally lower than those of the parent population. The small sample size (19 subjects) may be the contributing factor for lower ICCs because the 95% confidence intervals were generally greater than those of the parent population. Another limitation is the lack of correlation tests to identify the validities. In this study, there were only two tests (NRS and SPADI-K) in the correlation analyses. However, there were few available questionnaires for shoulder pain and disability in the Korean language.

In conclusion, we satisfactorily translated and adapted the SRQ and SDQ into the Korean language. Our study findings indicated that the SRQ-K and SDQ-K are reliable, valid, and responsive questionnaires that may be applied in patients with shoulder pain or disability, especially, adhesive capsulitis. Further studies should investigate the applicability of the SDQ-K and SRQ-K in patients with shoulder pain or disability of various causes in a large sample size.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Croft P, Pope D, Silman A. The clinical course of shoulder pain: prospective cohort study in primary care. Primary Care Rheumatology Society Shoulder Study Group. BMJ. 1996;313:601–602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7057.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Heijden GJ, Leffers P, Bouter LM. Shoulder disability questionnaire design and responsiveness of a functional status measure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.L'Insalata JC, Warren RF, Cohen SB, Altchek DW, Peterson MG. A self-administered questionnaire for assessment of symptoms and function of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:738–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright RW, Baumgarten KM. Shoulder outcomes measures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:436–444. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201007000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, Lertratanakul Y. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res. 1991;4:143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croft P, Pope D, Zonca M, O'Neill T, Silman A. Measurement of shoulder related disability: results of a validation study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:525–528. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.8.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heald SL, Riddle DL, Lamb RL. The shoulder pain and disability index: the construct validity and responsiveness of a region-specific disability measure. Phys Ther. 1997;77:1079–1089. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.10.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams JW, Jr, Holleman DR, Jr, Simel DL. Measuring shoulder function with the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:727–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaton DE, Richards RR. Measuring function of the shoulder: a cross-sectional comparison of five questionnaires. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:882–890. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199606000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(214):160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romeo AA, Bach BR, Jr, O'Halloran KL. Scoring systems for shoulder conditions. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:472–476. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bot SD, Terwee CB, van der Windt DA, Bouter LM, Dekker J, de Vet HC. Clinimetric evaluation of shoulder disability questionnaires: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:335–341. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.007724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seo HD, Lee KW, Jung KS, Chung YJ. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of shoulder pain and disability index. J Spec Educ Rehabil Sci. 2012;51:319–336. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt SM. Cross-cultural issues in the use of sociomedical indicators. Health Policy. 1986;6:149–158. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(86)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul A, Lewis M, Shadforth MF, Croft PR, Van Der Windt DA, Hay EM. A comparison of four shoulderspecific questionnaires in primary care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1293–1299. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.012088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozsahin M, Akgun K, Aktas I, Kurtais Y. Adaptation of the Shoulder Disability Questionnaire to the Turkish population, its reliability and validity. Int J Rehabil Res. 2008;31:241–245. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e3282fb7615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Windt DA, van der Heijden GJ, de Winter AF, Koes BW, Deville W, Bouter LM. The responsiveness of the Shoulder Disability Questionnaire. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:82–87. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.2.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Winter AF, van der Heijden GJ, Scholten RJ, van der Windt DA, Bouter LM. The Shoulder Disability Questionnaire differentiated well between high and low disability levels in patients in primary care, in a crosssectional study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:1156–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDowell I. Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, Lohr KN, Patrick DL, Perrin E, et al. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desai AS, Dramis A, Hearnden AJ. Critical appraisal of subjective outcome measures used in the assessment of shoulder disability. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:9–13. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12518836440522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang MH, Fossel AH, Larson MG. Comparisons of five health status instruments for orthopedic evaluation. Med Care. 1990;28:632–642. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vermeulen HM, Boonman DC, Schuller HM, Obermann WR, van Houwelingen HC, Rozing PM, et al. Translation, adaptation and validation of the Shoulder Rating Questionnaire (SRQ) into the Dutch language. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19:300–311. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr811oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]