Abstract

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is commonly used for primary evaluation of thyroid nodules. Twenty to 30 percent of thyroid nodules remain indeterminate after FNA evaluation. Studies show the BRAF p.V600E to be highly specific for papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), while RAS mutations carry up to 88 percent positive predictive value for malignancy. We developed a two-tube multiplexed PCR assay followed by single-nucleotide primer extension assay for simultaneous detection of 50 mutations in the BRAF (p.V600E, p.K601E/Q) and RAS genes (KRAS and NRAS codons 12, 13, 19, 61 and HRAS 61) using FNA smears of thyroid nodules. Forty-two FNAs and 27 paired formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues were tested. All BRAF p.V600E-positive FNA smears (five) carried a final diagnosis of PTC on resection. RAS mutations were found in benign as well as malignant lesions. Ninety-two percent concordance was observed between FNA and FFPE tissues. In conclusion, our assay is sensitive and reliable for simultaneous detection of multiple BRAF/RAS mutations in FNA smears of thyroid nodules.

Keywords: BRAF, RAS, single nucleotide primer extension assay, cytology smears, thyroid nodules

Introduction

The prevalence of palpable thyroid nodules in the United States is approximately 4 to 7 percent [1]. With examination by high resolution ultrasound, the incidence increases dramatically (19 to 67 percent) [2,3], with many of the additional nodules representing small, incidental lesions that are palpable during physical examination. Although between 5 and 10 percent of palpable nodules are malignant [4], the incidence of malignancy is likely less for small incidental lesions. As the fundamental purpose of nodule evaluation is to determine the probability that a nodule is malignant, additional testing modalities are necessary to clarify the probability of malignancy and develop a definitive management plan.

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is the most commonly used method for further evaluation of palpable and radiologically detected thyroid nodules. While the majority of nodules can be classified definitively as benign or malignant with FNA, up to 20 to 30 percent of aspirated nodules fall into indeterminate categories, including follicular neoplasm (FN), follicular lesion of undetermined significance/atypia of undetermined significance (FLUS/AUS), and suspicious for malignancy [5-7]. Although some of these are due to issues of specimen cellularity and/or other qualitative features that may be clarified by repeat FNA, many of these patients undergo diagnostic thyroid lobectomy that may be followed by completion thyroidectomy if the cytologically indeterminate nodule turns out to be malignant [8].

Alternations in the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway have been found to be associated with malignant thyroid nodules [9-11]. Mutation in BRAF protooncogene has been identified in 50 percent of papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTCs), and the presence of BRAF p.V600E mutation is highly specific for PTC (positive predicted value for cancer: 99.3 percent) [12]. RAS (KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS) mutations are the second most common mutation detected in FNA biopsy samples from thyroid nodules and have a 74 to 88 percent positive predictive value for malignancy [13]. Molecular testing has been shown to improve the accuracy of FNA diagnosis, particularly for nodules with indeterminate cytology [8,14-15] and thus may help with patient management decisions [16].

Multiple test platforms have been developed to detect mutations in BRAF and the RAS genes. The majority of clinical laboratories are still using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue/cell blocks as the sole source for molecular testing. We developed a simple, cost-effective two-tube multiplexed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay followed by single-nucleotide primer extension (Snu-PE) assay to simultaneously detect 50 mutations at 20 sites in BRAF and the RAS gene family. The same diagnostic cytology smears were used for molecular testing, which allows direct visualization of the area of interest and maximizes the utility of FNA materials.

Methods

This study contains data from a clinical test validation using archived specimens. The study was approved by the Institutional Research Review Committee at the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA). No informed consent was required.

Case Selection

Forty-two thyroid FNA smears — Romanowsky-type and Papanicolaou (Pap) stained — from 41 patients were selected from archived cytology slides at the Department of Pathology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (Iowa City, IA). Corresponding FFPE tissues from resection specimens were available from 27 specimens. All cases were reviewed by both surgical pathologists and cytopathologists. Care was taken to conserve a diagnostic slide for the medical record.

DNA Isolation

We targeted only areas with at least 30 percent follicular cells on the FNA smears. Areas with the highest percentage of follicular cells and least amount of contaminating materials (inflammatory cells, debris, blood, and mucin) were marked by a cytopathologist, followed by etching using a diamond-tipped pen on the underside of the slide. The slide was then soaked in xylene until the coverslip could be removed with ease. The de-coverslipped slide was washed in xylene, followed by washing with 95 to 100 percent ethanol. After air-drying, a small amount of matrix capture solution (Pinpoint Slide DNA Isolation, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) was applied to the desired areas. Tissue bound to the solution was manually microdissected and resuspended in DNA extraction buffer included in the Pinpoint kit, and this was followed by proteinase K digestion at 55°C overnight. After the overnight digestion, the tissue was heat-inactivated at 98°C for 10 minutes followed by 2 minutes on ice. The crude cell lysate was centrifuged (16,000 g × 10 minutes) and the supernatant was directly used for molecular testing.

For FFPE cell blocks/tissues, one hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slide and 10 unstained sections (6 microns in thickness) were cut. Areas with the highest percentage of tumor (percentage of tumor cells in all cases were above 85 percent) were marked on the H&E slide by a surgical pathologist, and corresponding areas from the unstained slides were manually microdissected using a razor blade. Depending on amount of tissue present, two to 10 sections were used. The paraffin flakes were placed in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube, deparaffinized with 1200 µL of xylene, vortexed, and centrifuged (16,000 g × 5 minutes). The tissue pellet was washed with 1200 µL of 95 percent ethanol twice before proceeding with the extraction. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from the microdissected FFPE sections using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Extracted gDNA from both cytology smears and FFPE tissues was quantified with the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). The quality of the DNA was assessed with the ratio of absorbances at 260 and 280 nm. The final volume for DNA from both sources was 60 µl.

PCR Amplification

Exon 15 of the BRAF gene; codons 12, 13, 19, and 61 of the KRAS gene; codons 12, 13, 61 of the NRAS gene; and codon 61 of the HRAS gene were PCR-amplified in two multiplexed reactions using primers as described previously [17-18]. For specimens with lower DNA concentration, the specimens were dried with a vacuum concentrator and resuspended in 5 µl of deionized water. The amplification products were purified using the Qiagen QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Positive Controls and Cell Lines

One NRAS mutant cell line, CRL 1572 (c.35G>A, p. G12D), and two HRAS mutant cell lines, CRL-1671 (c.183G>T, p.Q61H) and CRL-8083 (c.182A>G, p.Q61R), were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Positive controls for the rest of the mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange® Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (catalog #210518, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) followed by cloning into plasmids. Leucocytes from a healthy donor were used as a negative control.

BRAF (p.V600 and p.K601) and RAS (KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS) Mutation Analysis by Snu-PE

Snu-PE was performed using the SNaPshot Multiplex Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a two-tube assay. The approximate sizing locations of individual primers were determined by following the kit protocol from the SNaPshot Primer Focus Kit (Applied Biosystems), which allows separation of mutant peaks from wild-type peaks or non-specific peaks by both size and color. PCR amplification was performed as described above. After PCR amplification, the products were subjected to probe annealing and the addition of a single fluorescently labeled dideoxynucleotide. The primer extension probes were designed with various lengths of deoxythymidine monophosphate homopolymers ranging from 14 to 76 bases to allow discrimination of the products by size (see Table 1 for probe sequences). The probes were designed to be in the sense or antisense direction and end one base 5’ of the following positions: c.1799 and c.1801 of the BRAF gene; c.34, c.35, c.37, c.38, c.57, c.181, c.182, and c.183 of the KRAS gene; c.34, c.35. c.37, c.38, c.181, c.182, and c.183 of the NRAS gene; and c.181, c.182, and c.183 of the HRAS gene. Tube 1 contained BRAF p.V600 and p.K601, and codons 12, 13, 19, and 61 of the KRAS gene. Tube 2 included codon 61 of the HRAS gene and codons 12, 13, and 61 of the NRAS gene. The primer extension products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis (CE). The limit of detection (LOD) for mutations in all four genes was 5 percent.

Table 1. Probe sequences for BRAF and RAS Primer Extension Assay.

| Probes | Sequence (T# = poly “T” primer header) | Observed bp size | Strand | WT | MT |

| BRAF Probes | |||||

| BRAF V600E | T14 GGT GAT TTT GGT CTA GCT ACA G | 46 | sense | T | A |

| BRAF K601Q/E | T21 GGA CCC ACT CCA TCG AGA TT | 49 | antisense | T | G/C |

| KRAS Probes | |||||

| KRAS pos.34 | T30 GGC ACT CTT GCC TAC GCC AC | 55 | antisense | C | G/A/T |

| KRAS pos.35 | T36 AAC TTG TGG TAG TTG GAG CTG | 62 | sense | G | C/A/T |

| KRAS pos.37 | T44 CAA GGC ACT CTT GCC TAC GC | 67 | antisense | C | G/A/T |

| KRAS pos.38 | T49 CTT GTG GTA GTT GGA GCT GGT G | 77 | sense | G | C/A/T |

| KRAS pos.57 | T54 ATG ATT CTG AAT TAG CTG TAT CGT | 84 | antisense | C | G/A/T |

| KRAS pos.181 | T63 CTC ATT GCA CTG TAC TCC TCT T | 88 | antisense | G | C/A/T |

| KRAS pos.182 | T73 CAT TGC ACT GTA CTC CTC T | 98 | antisense | T | C/G/A |

| KRAS pos.183 | T76 CCT CAT TGC ACT GTA CTC CTC | 102 | antisense | T | C/G/A |

| HRAS Probes | |||||

| HRAS pos.181 | T15 CAT GGC GCT GTA CTC CTC CT | 41 | antisense | G | C/A/T |

| HRAS pos.182 | T20 GCA TGG CGC TGT ACT CCT CC | 49 | antisense | T | G/A/C |

| HRAS pos.183 | T5 GCA TGG CGC TGT ACT CCT C | 34 | antisense | C | G/A/T |

| NRAS Probes | |||||

| NRAS pos.34 | T28 CAA ACT GGT GGT GGT TGG AGC A | 56 | sense | G | C/A/T |

| NRAS pos.35 | T36 CTG GTG GTG GTT GGA GCA G | 61 | sense | G | C/A/T |

| NRAS pos.37 | T41 GGT GGT GGT TGG AGC AGG T | 65 | sense | G | C/A/T |

| NRAS pos.38 | T44 GTC AGT GCG CTT TTC CCA ACA | 69 | antisense | C | G/A/T |

| NRAS pos.181 | T53 CTC ATG GCA CTG TAC TCT TCT T | 80 | antisense | G | C/A/T |

| NRAS pos.182 | T58 GAC ATA CTG GAT ACA GCT GGA C | 85 | sense | A | C/G/T |

| NRAS pos.183 | T63 CTC TCA TGG CAC TGT ACT CTT C | 91 | antisense | T | G/A |

Mutation Analysis by Massively Parallel Sequencing

A laboratory-developed/validated next generation sequencing (NGS) panel that can detect hotspot mutations in 10 cancer-related genes (BRAF, KRAS, NRAS, HRAS, CTNNB, EGFR, FLT3, KIT, PDGFRA, and PIK3CA) was used to confirm some of the Snu-PE findings. Briefly, 20 ng of gDNA was used for preparation of the amplicon libraries using the Ion AmpliSeq™ 2.0 technology (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The AmpliSeq™ library was clonal amplification by emulsion PCR, followed by simultaneous/parallel sequencing of the clonally amplified DNA templates. The data were analyzed using the Ion Torrent Suite Software (Life Technologies), followed by a laboratory-developed and -validated pipeline. The assay has an analytic sensitivity of 5 percent.

Results

Characteristics of the Snu-PE Assay

The method of extracting gDNA from direct cytology smears (both Romanowsky-type and Pap) was previously validated at our Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified molecular pathology laboratory [19]. Genomic DNA was isolated from 42 FNA smears (35 Romanowsky-type and seven Pap). The number and percentage of follicular cells ranged from approximately 200 to 10,000 and 30 to 95 percent, respectively. The total DNA yields ranged from 6.9 ng to 1.65 µg. The DNA yield of FFPE tissue ranged from 0.18 to 14.52 µg.

The sensitivity of the assay was determined by mixing mutant gDNA with wild-type (WT) DNA from previously tested healthy individuals at different dilutions. Mutant cell lines for NRAS (one cell line) and HRAS (two cell lines) or plasmid DNAs that carry nine different mutations in five sites of KRAS codons 12 and 13, and p.V600 and p.K601, of the BRAF gene were used. The sensitivity of the assay for all mutations in four genes was 5 percent. A mixture of DNAs with different known mutations in BRAF/KRAS and HRAS or NRAS genes, each representing a final mutant allele frequency of 5 percent, was included as a positive control and sensitivity control in each run.

Detection of BRAF and KRAS/NRAS/HRAS Mutations by Snu-PE

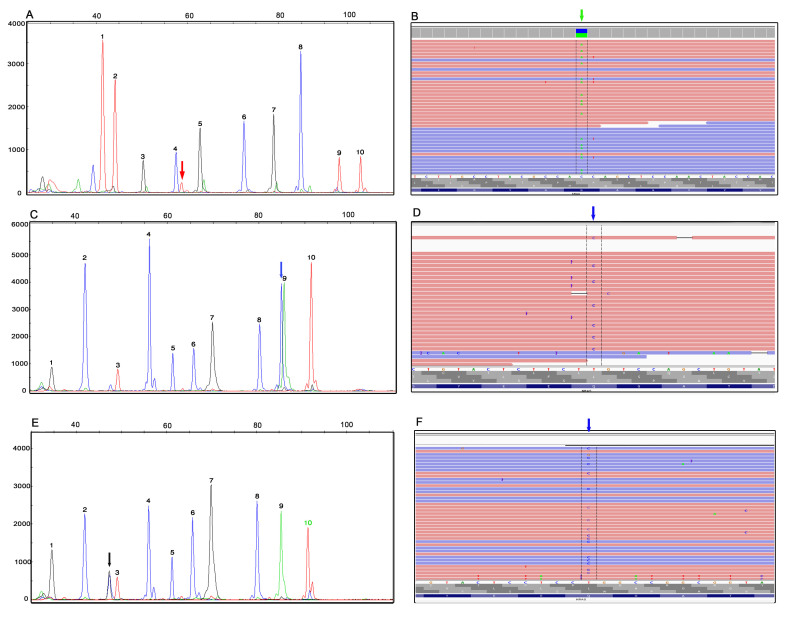

Mutation analysis for BRAF p.V600E, p.K601E, p.K601Q; KRAS codons 12, 13, 19, and 61; NRAS codons 12, 13, and 61; and HRAS codon 61 was performed using gDNAs extracted from both direct cytology smears as well as FFPE tissues. Seven BRAF p.V600E mutations, two KRAS mutations, six NRAS mutations, and one HRAS mutations were identified in 16 of 42 FNA smears (38 percent) (Table 2). Twelve mutations (four BRAF, two KRAS, and six NRAS) were identified in 27 FFPE specimens (44 percent). Two cases (18 and 22) had a weak BRAF p.V600E peak in FNA smears but not in corresponding FFPE tissues. Both BRAF p.V600E and NRAS p.Q61K mutations were found in the cytology smear in Case 34. Coexistent PTC and hyperplastic nodule were identified on the same block in the resection specimen. Areas with PTC and nodular hyperplasia were microdissected separately from FFPE tissues and tested for BRAF/RAS mutations. A BRAF p.V600E mutation was identified in PTC and a NRAS p.Q61K mutation was found in the hyperplastic nodule. Representative Snu-PE findings of a KRAS p.G12V mutation in a Hürthle cell nodule (Case 6), a NRAS p.Q61R mutation in an adenomatoid nodule (Case 35), and a HRAS mutation in a follicular variant of PTC (FVPTC) (Case 41) are shown in Figure 1 (A, C, and E). The mutant peak (black) in 1E overlapped with a non-specific peak (blue) but was the right color and size based on SNaPshot Primer Focus Kit.

Table 2. Correlation of Molecular Findings with Cytologic and Surgical Pathologic Diagnosis.

| Case | FNT Diagnosis | Resection Diagnosis | BRAF | KRAS | NRAS | HRAS | Stain | Smear: DNA yield (ng/µl) | FFPE: DNA yield (ng/µl) | Confirmation by NGS | Concordance with FFPE |

| 1 | AUS | FVPTC | p.V600E | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 3.30 | 3.0 | NT | YES |

| 2 | AUS | Multinodular hyperplasia | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 2.91 | 111 | NT | YES |

| 3 | FN | PTC, CV | WT | WT | p.Q61R | WT | Pap | 0.69 | 65 | YES | YES |

| 4 | AUS | Adenomatoid nodule | WT | WT | WT | WT | Pap | 0.68 | 74 | YES | YES |

| 5 | AUS | FA | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 9.78 | 47 | NT | YES |

| 6 | HN | Hurthle cell nodule | WT | p.G12V | WT | WT | DQ | 7.22 | 88 | YES | YES |

| 7 | Sus PTC | PTC | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 11.00 | 242 | NT | YES |

| 8 | Sus PTC | PTC | p.V600E | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 2.20 | 22 | NT | YES |

| 9 | Sus PTC | PTC | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 1.48 | 46 | YES | YES |

| 10 | Sus PTC | PTC | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 10.80 | NT | NT | NT |

| 11 | FN | FA | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 12.50 | 81 | NT | YES |

| 12 | FN | FA | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 21.20 | 9.0 | NT | YES |

| 13 | Sus PTC | PTC | p.V600E | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 9.0 | NT | NT | NT |

| 14 | FN | FA | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 5.08 | 221 | NT | YES |

| 15 | AUS | Adenomatoid nodule | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 30.00 | 47 | NT | YES |

| 16 | Sus FN | FVPTC | WT | p.Q61R | WT | WT | DQ | 11.70 | 80 | YES | YES |

| 17 | Sus FN | FC | WT | WT | WT | WT | Pap | 0.13 | 45 | NT | YES |

| 18 | AUS | FA | Weak p.V600E | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 7.00 | NT | NO | NO |

| 19 | Sus FN | FA | WT | WT | p.Q61K | WT | Pap | 0.3 | 96 | NT | YES |

| 20 | FN | FA | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 23.40 | 232 | NT | YES |

| 21 | AUS | FVPTC | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 7.00 | 21 | NT | YES |

| 22 | Sus FN | FVPTC | Weak p.V600E | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 20.04 | 30 | NO | NO |

| 23 | Sus FN | FVPTC | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 5.00 | 21 | NT | YES |

| 24 | AUS | Nodular hyperplasia | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 2.16 | NT | NT | NT |

| 25 | Sus FN | Benign nodule | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 9.24 | NT | NT | NT |

| 26 | AUS | FA | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 0.20 | NT | NT | NT |

| 27 | HN | HC | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 13.00 | NT | NT | NT |

| 28 | Sus HN | HC | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 2.96 | NT | NT | NT |

| 29 | Hurthle cell nodule | Hyperplastic nodules with hurthle cell change | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 1.62 | NT | NT | NT |

| 30 | AUS | FC | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 0.15 | NT | NT | NT |

| 31 | HN | PTC | WT | WT | WT | WT | Pap | 18.20 | NT | NT | NT |

| 32 | HN | HC | WT | WT | WT | WT | Pap | 4.52 | NT | NT | NT |

| 33 | AUS | microcarcinoma | WT | WT | WT | WT | Pap | 2.06 | NT | NT | NT |

| 34 | FN | PTC | p.V600E | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 2.3 | 14.5 | YES | YES |

| FN | Nodular hyperplasia | WT | WT | p.Q61K | WT | DQ | 2.3 | 250 | YES | YES | |

| 35 | FN | Adenomatoid nodule | WT | WT | p.Q61R | WT | DQ | 3.04 | 141 | YES | YES |

| 36 | FN | PTC | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 10.80 | NT | NT | NT |

| 37 | Hurthle cell lesion | Adenomatoid nodule with Hurthle cell change | WT | WT | p.Q61R | WT | DQ | 9.52 | 107 | NT | YES |

| 38 | FN | Adenomatoid nodule | WT | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 5.20 | NT | NT | NT |

| 39 | FN | FA | WT | WT | p.Q61R | WT | DQ | 0.12 | 4.5 | YES | YES |

| 40 | PTC | FVPTC | p.V600E | WT | WT | WT | DQ | 0.54 | 65 | NT | YES |

| 41 | FN | FVPTC | WT | WT | WT | p.Q61R | DQ | 12.9 | NT | YES | NT |

Abbreviations: AUS, atypia of undetermined significance; Dud, suspicious; FVPTC, follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma; CV, columna cell variant; FN, follicular neoplasm; FA, follicular adenoma; FC, follicular carcinoma; HC, Hurthle cell carcinoma; HN, Hurhtle cell neoplasm; WT, wild-type; DQ, Diff-Quick stain; Pap, Papanicolaou stain; FFPE, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded; NGS, next generation sequencing; NT, not tested.

Figure 1.

Detection of RAS mutations by Snu-PE assay and confirmation by NGS. The mutation analysis for the RAS family genes was performed with a 2-tube multiplexed polymerase chain reaction followed by a Snu-PE assay. A) KRAS c.35G>T (p.G12V) mutation (red peak indicated by the arrow) in a FNA of Hurthle cell nodule (Case 6). Peaks 1 to 10 represent the wild-type alleles at positions c.1799 and c.1801 of the BRAF gene; and c.34, c.35, c.37, c.38, c.57, c.181, c.182, and c.183 of the KRAS gene, respectively. B) The presence of KRAS c.35G>T mutation in A (green arrow, reverse strand) was confirmed by NGS. Integrative genomic viewer (IGV). C) NRAS c.182A>G (p.Q61R) mutation (blue peak indicated by the arrow) in FNA smear of an adenomatoid nodule (case #35). D) NGS confirmation of NRAS c.182A>G mutation (blue arrow, reverse strand) detected in C. IGV view. E) HRAS c.182A>G (p.Q61R) mutation (black peak indicated by the arrow, antisense probe) in a follicular variant of PTC (Case 41). F) NGS confirmation of HRAS c.182A>G mutation (blue arrow, reverse strand) detected in E. IGV view. Peaks 1-10 in C and E represent the wild-type alleles at positions c. 183, c.181, and c.182 of HRAS and c.34, c.35, c.37, c.38, c.181, c.182, and c.183 of the NRAS gene, respectively. Labels on the x-axis are the size markers. Labels on the y-axis indicate the intensity of the fluorescence, which can be used as a relative assessment of the mutant sequence represented in the sample. Ref, reference sequence; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; NGS, next generation sequencing; Snu-PE, single-nucleotide primer extension; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Confirmation of Snu-PE Findings by NGS

A laboratory-developed and validated NGS panel, which includes all BRAF and RAS mutations in our Snu-PE assay, was used to confirm findings of the Snu-PE assay. Eight positive case that include all the cases with low mutant allele frequency and sufficient remaining DNA and two negative cases were tested. Representative results of NGS confirmation are shown inFigure 1 (B, D, and F). The weak BRAF p.V600E peaks in the FNA smear of Cases 18 and 22 were not identified by NGS. A low level (4.9 percent) of NRAS p.Q61R mutation was identified in the FNA smear of Case 39, and an even lower frequency (2.5 percent) was seen in the corresponding FFPE tissue. The presence of this mutation was confirmed by NGS at an allele frequency of 4.1 percent in FNA smear of Case 39 but not in the paired FFPE tissue. The BRAF p.V600E mutation in Cases 18 and 22 FNA smears were considered as false positives, but the NRAS mutation in the Case 39 FNA smear was considered as a true positive.

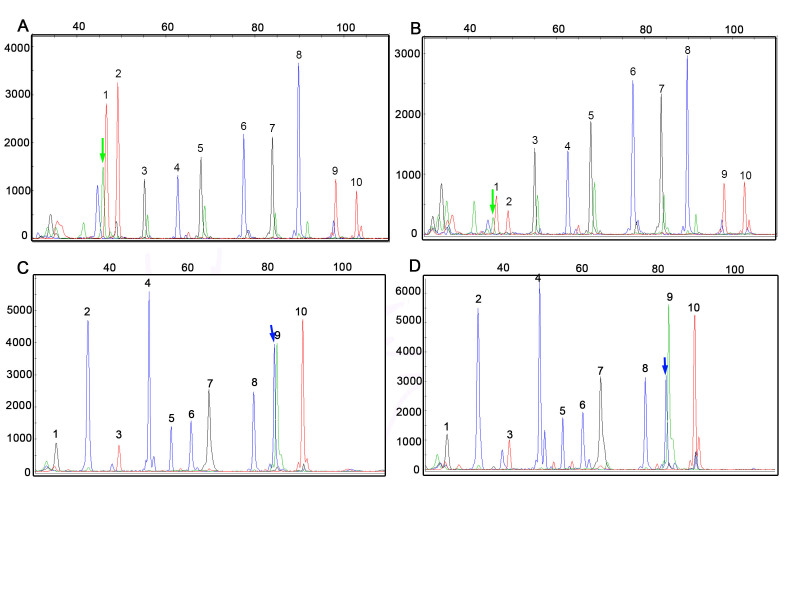

Correlation of Cytology Smear with FFPE Tissue

DNAs from 27 cases with available corresponding FFPE tissue were tested by Snu-PE in parallel. Concordance between cytology smears and FFPE tissue was found in 25 cases (92.5 percent, n = 17). Representative Snu-PE findings in cytology smears and corresponding FFPE tissues were shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

BRAF and NRAS mutations detected by Snu-PE in FNA smears and paired FFPE tissues. A) BRAF c.1799T>A (p.V600E) mutation (green peak indicated by the arrow) detected in a follicular variant of PTC (Case 40). B) Paired FFPE tissue of Case 40 in A. Peaks 1-10 in A and B represent wild-type alleles at positions c.1799 and c.1801 of the BRAF gene and c.34, c.35, c.37, c.38, c.57, c.181, c.182, and c.183 of the KRAS gene, respectively. C) NRAS c.182A>G (p.Q61R) mutation (blue peak indicated by the arrow) in a second case of follicular variant of PTC (Case 3). D) Paired FFPE tissue of Case 3 in C. Peaks 1-10 in C and D represent the wild-type alleles at positions c. 183, c.181, and c.182 of HRAS and c.34, c.35, c.37, c.38, c.181, c.182, and c.183 of the NRAS gene, respectively. Labels on the x-axis are the size markers. Labels on the y-axis indicate the intensity of the fluorescence, which can be used as a relative assessment of the mutant sequence represented in the sample. The blue peak at c.1799 and the green peaks at c.34, c.37, c.57 and c.181 in (A) and (B) are artifacts which were not present in primer focus. SNu-PE, single-nucleotide primer extension; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; FFPE, formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded.

Correlation of Molecular Findings with Pathologic Diagnosis of Thyroid Nodules

The cytologic diagnosis of the 42 FNA cases included in this study were 11 atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance (AUS/FLUS), 25 follicular neoplasm (FN)/suspicious for FNs, five suspicious for malignancy and one PTC. The initial cytologic diagnosis for the 5 BRAF V600E-positive cases were AUS (1), suspicious for FN (1), suspicious for PTC (2), and PTC (1), all of which carried a final diagnosis of PTC on resection. The six NRAS-positive cases were FN/suspicious for FN (4), follicular lesion (1), and Hürthle cell lesion (1). The surgical pathology diagnoses were follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (FVPTC) (1), follicular adenoma (FA) (2), and benign follicular nodules (3). One KRAS-positive case had a FNA and surgical pathology diagnosis of FN (Hürthle cell) and Hürthle cell nodule, respectively. The second KRAS-positive case had a FNA diagnosis of suspicious for FN and tissue diagnosis of FVPTC. The only HRAS-positive case was diagnosed as FN by FNA and FVPTC on resection. The correlation of molecular findings with cytologic and histologic diagnosis is summarized in Table 2. The risk of malignancy and benign lesions associated with FNA diagnosis and mutation is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Risk of Malignancy and Benign Lesions Associated with FNA Diagnosis and Mutation.

| FNA Diagnostic Category | Malignancy Associated with FNA Diagnosis | Malignancy Associated with Mutations | Benign Lesions Associated with Mutation |

| FLUS/AUS | 36% (n=11) | 25% (n=4) | 0 (n=7) |

| FN or Suspicious for FN | 48% (n=25) | 33% (n=12) | 46% (n=13) |

| Suspicious for Malignancy | 100 % (n=5) | 40% (n=5) | 0 (n=0) |

| Malignant | 100% (n=1) | 100% (n=1) | 0 (n=0) |

| Total | 52% (n=42) | 66% (n=22) | 30% (n=20) |

Abbreviations: FLUS/AUS, follicular lesion of undetermined significance/atypia of undetermined significance (FLUS/AUS); FN, follicular neoplasm.

Discussion

Molecular testing for follicular lesions of the thyroid has recently gained attraction and can help direct clinical and surgical management in a subset of thyroid nodules [8,14-16]. The management for obviously malignant and benign thyroid lesions is usually straightforward. However, for indeterminate follicular lesions, patients may first undergo lobectomy, followed by completion thyroidectomy if necessary. Nikiforov et al. [8,14-16] proposed the role of molecular oncology tests on indeterminate thyroid lesions and showed that the presence of BRAF p.V600E mutation was highly specific for PTC. Although RAS gene mutations can also be seen in benign conditions such as FAs and adenomatoid nodules, they carry a 74 to 88 percent positive predictive value for malignancy [14,16,19].

In the majority of laboratories, molecular tests are only performed on FFPE cell blocks derived from aspirate materials. The diagnosis of thyroid nodules by FNA rarely/never requires cell blocks. The only purpose for the preparation of cell block is for molecular analysis. A pitfall of cell block is the inability to evaluate cellularity of this material on-site, and many times there is insufficient tissue in the block. When this situation arises, a decision has to be made whether to take the patient back for repeat FNA or for a more invasive procedure. Cytologic smears almost always contain sufficient material for diagnosis and are a unique reservoir of DNA for molecular testing. We recently demonstrated that DNAs from direct cytology smears could be used on multiple platforms for molecular oncology testings [19]. In the current study, amplifiable gDNA was extracted from all 42 FNA smears. The low DNA yield from some smears was due to the paucity of cells on the slides.

Twenty-seven FNA cases had paired FFPE tissues from surgical resections. Discordance was seen in two cases. Cases 18 and 22 had a low a level of BRAF p.V600E (around 3 percent of WT allele) in FNA smears using Snu-PE, but not in paired FFPE tissues. This mutation was not detected by NGS in either FNA smear or paired FFPE tissues. The tumor percentage was over 50 percent in the cytology smear and 85 percent in FFPE tissue. A much higher mutant allele frequency is expected if the mutation is true. In addition, the LOD of the assay is 5 percent. Mutant peaks below LOD could represent non-specific background peak. These two FNA smears were, therefore, considered as false positives. The third case (39) had a weak NRAS p.Q61R mutation from the tested FNA smear with mutant content of 4.9 percent by Snu-PE and allele frequency of 4.1 percent by NGS. The mutant had an allele frequency of 2.5 percent in the FFPE tissue by Snu-PE but was detected by NGS. This case most likely represents a true-positive finding. We have observed that DNA extracted from cytology preparations seemed to have better quality on the basis of the relative mutant allele present in the cytology specimens [19]. The discrepancy between cytology smear and FFPE tissue could also be due to the presence of inhibitory factors in the FFPE tissue. The risk of PCR contamination also should be taken into consideration when working with small number of cells, especially using sensitive test platforms such as NGS and our Snu-PE assay. For cases with mutation peaks below or at the LOD, especially when the tumor percentage was high, we routinely confirm the Snu-PE findings by an alternative method of similar or higher sensitivity and correlate them with the tumor percentage and pathologic diagnosis.

In our small cohort, we detected 14 mutations in 42 FNA smears from 41 patients. The case with co-existing PTC and hyperplastic nodule (No. 34) had two different mutations: the BRAF p.V600E mutation was only seen in PTC, and the NRAS mutation was identified in the benign follicular hyperplasia. The overall mutation frequency was 33 percent (n = 42). Thirty-eight percent (n = 21) of the malignancies had BRAF or RAS mutations. In benign lesions, the frequency of mutation was 25 percent (n = 20) (Table 3). The positive predictive value of BRAF V600E for PTC was 100 percent, consistent with the reports in the literature [8,14-16]. RAS mutations were associated with malignant as well as benign follicular lesions. The predicted value of RAS mutation for malignancy was lower than reported in the literature, which is most likely due to the limited number of cases in this study.

Multiple test platforms with different LODs are available in our laboratory for the detection of BRAF and RAS mutations. Sanger sequencing has been considered the gold standard for detection of point mutations and small deletion/duplications. It is labor-intensive and has a low analytical sensitivity of 20 percent. We also have two NGS platforms that are more sensitive than Sanger but have a longer turn-around time and higher cost. Our Snu-PE assay requires a minimum of 6 ng input gDNA. When probes were carefully designed in sense and anti-sense directions and of various lengths, we were able to detect 50 mutations at 20 sites, which include the most commonly mutated sites in BRAF and the RAS gene family. The analytic sensitivity of the assay is 5 percent, similar to our NGS platforms. The test has a quick turn-around time and a direct cost of less than $150. It is not only useful for mutation detection in thyroid FNA nodules; it can also be used to determine the eligibility of patients with colorectal carcinoma or malignant melanoma, which commonly harbor BRAF p.V600E or RAS mutations, for targeted therapies and as a confirmatory test for low level of mutations identified by Sanger sequencing and NGS.

The limitation of this assay is its inability to detect dinucleotide changes in the BRAF gene. This is less of a problem in thyroid cancers, since almost all BRAF mutations in PTC are p.V600E, with mutations in other BRAF codons exceedingly rare. NGS or Sanger sequencing can be used to confirm the findings when double mutant peaks are seen.

In conclusion, our study confirms that the FNA smear from thyroid nodules is a reliable source of DNA for mutation analysis of BRAF and RAS genes. Our laboratory-developed Snu-PE assay worked well on DNA isolated from both Romanowsky-type and Pap stained slides. It is simple, cost-effective, and has a short turn-around time. This approach allows molecular assays to be performed on specific cells of interest and maximizes the utility of FNA materials. It may also save patients from an additional, unnecessary procedure.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the molecular pathology and histology laboratories for their technical support.

Abbreviations

- FNA

fine-needle aspiration

- PTC

papillary thyroid carcinomas

- FN

follicular neoplasm

- FLUS/AUS

follicular lesion of undetermined significance/atypia of undetermined significance

- FFPE

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded

- Snu-PE

single-nucleotide primer extension

- LOD

limit of detection

- NGS

next generation sequencing

- Pap

Papanicolaou

Author contributions

AAS performed all the molecular tests; MPG identified and reviewed all the cytology cases; RAS and CSJ provided guidance with case selection and editing of the manuscript; DM designed the project and provided guidance of the entire study. All authors contributed with manuscript preparation.

References

- Welker MJ, Orlov D. Thyroid nodules. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(3):559–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaferri EL. Thyroid cancer in thyroid nodules: finding a needle in the haystack. Am J Med. 1992;93(4):359–362. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan GH, Gharib H. Thyroid incidentalomas: management approaches to nonpalpable nodules discovered incidentally on thyroid imaging. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(3):226–231. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-3-199702010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito JP, Yarur AJ, Prokop LJ, McIver B, Murad MH, Montori VM. Prevalence of thyroid cancer in multinodular goiter versus single nodule: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2013;23(4):449–455. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The Bethesda System For Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132(5):658–665. doi: 10.1309/AJCPPHLWMI3JV4LA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohori NP, Schoedel KE. Variability in the atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance diagnosis in the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: sources and recommendations. Acta Cytol. 2011;55(6):492–498. doi: 10.1159/000334218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloch ZW, LiVolsi VA, Asa SL, Rosai J, Merino MJ, Randolph G. et al. Diagnostic terminology and morphologic criteria for cytologic diagnosis of thyroid lesions: a synopsis of the National Cancer Institute Thyroid Fine-Needle Aspiration State of the Science Conference. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36(6):425–437. doi: 10.1002/dc.20830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov YE, Yip L, Nikiforova MN. New strategies in diagnosing cancer in thyroid nodules: impact of molecular markers. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(9):2283–2288. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura ET, Nikiforova MN, Zhu Z, Knauf JA, Nikiforova YE, Fagin JA. High prevalence of BRAF mutations in thyroid cancer: genetic evidence for constitutive activation of the RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF signaling pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63(7):1454–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frattini M, Ferrario C, Bressan P, Balestra D, De Cecco L, Mondellini P. Alternative mutations of BRAF, RET and NTRK1 are associated with similar but distinct gene expression patterns in papillary thyroid cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23(44):7436–7440. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova MN, Lynch RA, Biddinger PW, Alexander EK, Dorn GW 2nd, Tallini G. et al. RAS point mutations and PAX8-PPAR gamma rearrangement in thyroid tumors: evidence for distinct molecular pathways in thyroid follicular carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(5):2318–2326. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova YE, Nikiforov MN. Molecular genetics and diagnosis of thyroid cancer. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(10):569–580. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaijee F, Nikiforov YE. Molecular analysis of thyroid tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2011;22(3):126–133. doi: 10.1007/s12022-011-9170-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov YE, Steward DL, Robinson-Smith TM, Haugen BR, Klopper JP, Zhu Z. et al. Molecular testing for mutations in improving the fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of thyroid nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(6):2092–2098. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohori NP, Nikiforova MN, Schoedel KE, LeBeau SO, Hodak SP, Seethala RR. et al. Contribution of molecular testing to thyroid fine-needle aspiration cytology of “follicular lesion of undetermined significance/atypia of undetermined significance”. Cancer Cytopathol. 2010;118(1):17–23. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov YE, Ohori NP, Hodak SP, Carty SE, LeBeau SO, Ferris RL. et al. Impact of mutational testing on the diagnosis and management of patients with cytologically indeterminate thyroid nodules: a prospective analysis of 1056 FNA samples. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(11):3390–3397. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurkin I, Stoehr R, Hurst CD, van Tilborg AA, Knowles MA, Hartmann A. et al. Two multiplex assays that simultaneously identify 22 possible mutation sites in the KRAS, BRAF, NRAS and PIK3CA genes. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gailey MP, Stence AA, Jensen CS, Ma D. Multiplatform comparison of molecular oncology tests performed on cytology specimens and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123(1):30–39. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantara S, Capezzone M, Marchisotta S, Capuano S, Busonero G, Toti P. et al. Impact of proto-oncogene mutation detection in cytological specimens from thyroid nodules improves the diagnostic accuracy of cytology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1365–1369. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]