Abstract

The results of our third trial on epicutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy (EPIT) will be presented and discussed in the context of our previous trials. This monocentric, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase I/IIa trial included 98 patients with grass pollen rhinoconjunctivitis. Prior to the pollen season 2009, patients received six patches (allergen extract: n = 48; placebo: n = 50) with weekly intervals, administered onto tape-stripped skin. Allergen EPIT produced a median symptom improvement of 48% in 2009 and 40% in the treatment-free follow-up year 2010 as compared to 10% and 15% improvement after placebo EPIT (P = 0.003). After allergen EPIT but not placebo EPIT, conjunctival allergen reactivity was significantly decreased and allergen-specific IgG4 responses were significantly elevated (P < 0.001). In conclusion, our three EPIT trials found that allergen EPIT can ameliorate hay fever symptoms. Overall, treatment efficacy appears to be determined by the allergen dose. Local side-effects are determined by the duration of patch administration, while risk of systemic allergic side-effects is related to the degree of stratum corneum disruption.

Keywords: allergen-specific antibodies, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, epicutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy, needle-free immunisation, patch immunisation

Classic subcutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy (SCIT) (1) has two shortcomings: long treatment duration with numerous injections and local or systemic allergic side-effects. Introduction of sublingual allergen-specific immunotherapy (SLIT) made immunotherapy safer (2), but treatment duration could not be shortened and low treatment adherence is a problem in both (3), SCIT and SLIT. Allergen delivery to the epidermis, epicutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy (EPIT), represents a highly interesting route for allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT), as the epidermis contains a high density of antigen-presenting cells (4). This should reduce the number of required AIT administrations. Moreover, the epidermis is nonvascularized, which should reduce the risk of systemic allergic side-effects due to inadvertent intravascular allergen delivery. Here, we present our third clinical trial on EPIT and compare the results with our two previous trials.

Detailed methods are given in the online repository. This single-centre phase I/IIa, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study was conducted in Zurich, Switzerland. A total of 121 subjects were screened in November and December 2008. Ninety-nine patients were enrolled and assigned to receive allergen EPIT (n = 48, grass pollen extract in petrolatum 1.5 ml; 200 IR/ml; Stallergènes, Anthony, France) or placebo EPIT (n = 50, petrolatum 1.5 ml) using stratified randomization according to reported rhinoconjunctivits symptom severity (Fig. S1). Full treatment consisted of six patches, each applied to the upper arm and kept there for 8 h. Patches were administered in weekly intervals during December 2008 to February 2009, that is before the pollen season 2009. Before patch application, the treated skin area was prepared by adhesive tape-stripping ten times (Scotch-Tape®; 3M Company, St Paul, MN, USA). Before application of the first patch, skin preparation was performed by abrasion using a foot file (Pedic care® 100 grit; Migros, Zurich, Switzerland,) in the first 52 study subjects (Fig. S2A). This procedure was stopped due to high number of systemic allergic side-effects (5). Primary outcome treatment efficacy was assessed after the treatment year 2009 and after the treatment-free follow-up year 2010 (Table S1) by visual analogue scale to rate general improvement or deterioration on a scale ranging from −100 mm (worst conceivable symptom exacerbation) to +100 mm (total symptom relief).

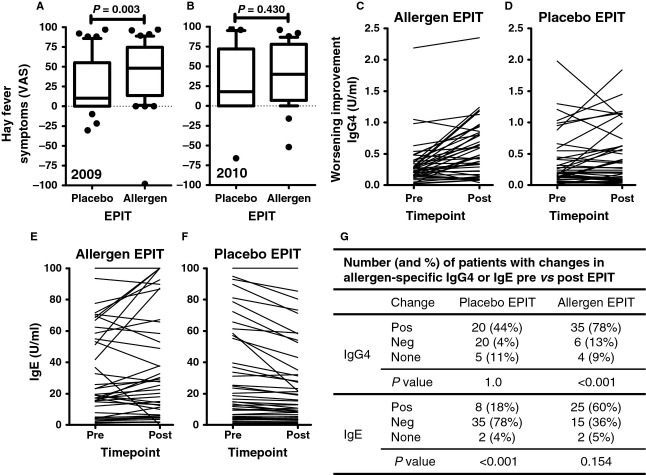

The allergen EPIT and the placebo EPIT groups did not differ in demographic and disease-specific baseline characteristics, except that more women than men were randomized to receive allergen EPIT (Table S2). After treatment in the year 2009, a median hay fever symptom improvement of 48% was reported after allergen EPIT (without significant difference between subgroups receiving abrasion or tape-stripping prior to the first patch, Fig. S2B), while improvement after placebo EPIT was 10% (Fig.1A, P = 0.003). In 2010, without any further immunotherapy, median improvement was still 40% after allergen EPIT, but only 18% after placebo EPIT (Fig.1B, P = 0.430). For the combined symptom and medication score, no difference between the treatment groups was observed. However, a significant decrease in conjunctival reactivity was recorded after the first season of allergen EPIT (2009, P = 0.005), while the conjunctival provocation test threshold did not change after placebo EPIT (P = 0.218). Furthermore, allergen-specific IgG4 significantly increased after allergen EPIT in 2009 (Fig.1C, median increase 58%, P < 0.001), but not after placebo EPIT (median increase 0%, P = 1.0, Fig.1D). For allergen-specific IgE, there was no significant increase after allergen EPIT in 2009 (Fig.1E, P = 0.154) but a decrease after placebo-EPIT (Fig.1G, P < 0.001). Exact frequencies of improvement for the different treatment groups are given in the inset table (Fig.1G). After 2010, no significant effect was seen anymore for IgG4 and IgE as compared to pre-EPIT values for any treatment group.

Figure 1.

(A) Improvement/deterioration of hay fever symptoms after treatment year 2009 and (B) treatment-free follow-up year 2010 as compared to pretreatment years recorded on a scale from −100 (worst possible deterioration) to +100 (best possible improvement). Box plots show the median, the 10th, 25th, 75th and 90th percentiles and outliers. (C, D) Allergen-specific IgG4 and (E, F) IgE responses pre- and posttreatment in 2009. One outlier is not shown in the placebo epicutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy (EPIT) group IgG4 pre- (3.92)/posttreatment (4.32). (G) Inset table showing number and frequencies of patients with enhanced (pos) or reduced (neg) antibody response after EPIT in 2009.

Eight systemic allergic reactions led to study exclusion. Six reactions occurred after abrasion and allergen EPIT (one grade 1 and five grade 2 reactions). Only one reaction occurred after tape-stripping and allergen EPIT (grade 2). One systemic grade 2 reaction was observed in the placebo group (Table S3). No serious adverse events were recorded.

Table 1 summarizes and compares our three EPIT trials and suggests a pattern. Within the second trial (6), there was a clear dose–response relationship, and similarly, the present trial may be interpreted as the medium dose version of the second trial. Hence, clinical efficacy appears to depend on the allergen dose. Local eczematous reactions after EPIT strongly correlated with the duration of patch application, with more and stronger reactions after 48 h (7) as compared to 8 h applications (6). We assume that 8 h is sufficient to pulse antigen-presenting cells, but later, when T cells start infiltrating, the allergen is already vanishing. Hence, a reduction from 48 to 8 h patch application was accompanied by roughly 50% reduction in local eczema reactions, while clinical efficacy was still comparable. Systemic side-effects, however, primarily correlated with the degree of stratum corneum disruption (5) with six systemic allergic reactions after skin preparation by abrasion (n = 26; 23%) and only one systemic reaction after skin preparation by adhesive tape-stripping (n = 239, 0.4%), which was not more than in the placebo group (n = 277, 0.4%).

Table 1.

Epicutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy trials comparison

| First trial (pollen season 2006) (7) | Second trial (pollen season 2007) NCT00719511 (6) | Third trial (pollen season 2009) NCT00777374 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Proof of concept | Dose–response study | Immune response |

| Allergen extract | 5 Graminées, Stallergènes, France | 6 Graminées, Inmunotek, Spain | 5 Graminées, Stallergènes, France |

| Solvent | Petrolatum | Glycerol 50% | Petrolatum |

| Allergen extract potency | 200 IR/ml, 1.5 ml (=1× atopy patch test) =21 μg Phl p 5 | 10 HEP/ml, 1 ml (=1× prick test) =3 μg Phl p 5 | 200 IR/ml, 1.5 ml (=1× atopy patch test) =21 μg Phl p 5 |

| 50 HEP/ml, 1 ml (=5× prick test) =15 μg Phl p 5 | |||

| 100 HEP/ml, 1 ml (=10× prick test) =30 μg Phl p 5 | |||

| Time of tape-stripping | 6× | 6× | 10× |

| Number of patches | 12 patches | 6 patches | 6 patches |

| Cumulative dose | 252 μg Phl p 5 | 10 HEP: 18 μg Phl p5 50 HEP: 90 μg Phl p5 100 HEP: 180 μg Phlp5 | 126 μg Phl p 5 |

| Patch application time (h) | 48 | 8 | 8 |

| Efficacy: first year (median VAS symptom improvement) | 50% | 10 HEP: 44% 50 HEP: 51% 100 HEP: 63% | 48% |

| Efficacy: follow-up (median VAS symptom improvement) | 72% | 10 HEP: 31% 50 HEP: 53% 100 HEP: 70% | 40% |

| Safety: eczema (eczema/allergen patch application) | 160/252 (63.5%) | 10 HEP: 29/174 (16.6%) 50 HEP: 51/171 (29.8%) 100 HEP: 44/171 (25.7%) | 48/265 (18.1%) |

| Safety: systemic side-effects (n = study participants, y = total patches) | 0 (n = 21, y = 252) | 10 HEP: 3 (n = 33, y = 174) 50 HEP: 3 (n = 33, y = 171) 100 HEP: 4 (n = 33, y = 175) | 1 (after tape-stripping, n = 24, y = 239) 6 (after abrasion, n = 26, y = 26*first patch) |

VAS, visual analogue scale.

The current trial was the first to measure induction of allergen-specific IgG4 after allergen EPIT. In SCIT, IgG4 has been shown to increase IgG4 by a factor of 30–40 (8,9), while SLIT increased IgG4 by factor of 3–4 (8). After allergen EPIT, IgG4 increased by 58%, or a factor of 1.58.

In summary, this and two previous allergen EPIT trials from our groups suggest that this novel therapeutic strategy may find potential application in the management of IgE-mediated allergies. However, further research and development is needed to define an optimal regime that balances clinical efficacy and safety. Our three EPIT trials have shown that the skin preparation method, the allergen dose in the patch, the number of patches administered, and the duration of each patch application are parameters that affect efficacy and side-effects. Moreover, the interval between each patch and the additional use of adjuvants or other immune response modifiers (10–12) may be parameters to be integrated into the development of allergen-EPIT. Targeted methods of allergen delivery such as the use of microneedles (13) or laser microporation (14) may also improve allergen-EPIT. Finally, while we used allergen extracts in our three EPIT trials, peptides, recombinant allergens (15) or other hypoallergenic allergen preparations may represent a safety benefit in allergen EPIT as in AIT in general.

Acknowledgments

We thank study nurses Mirjam Blattmann, Miriam Hunziker and Andrea Nef for their support.

Glossary

- AE

adverse event

- AIT

allergen-specific immunotherapy

- CPT

conjunctival provocation test

- EPIT

epicutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy

- SCIT

subcutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy

- SLIT

sublingual allergen-specific immunotherapy

- SPT

skin prick test

- VAS

visual analogue scale

Funding

This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (320030_140902).

Conflicts of interest

Gabriela Senti and Thomas Kündig are named as inventors on a patent on EPIT. This patent is owned by the University of Zurich.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Data S1. Methods.

Table S1. Study outline.

Table S2. Baseline characteristics.

Table S3. Side effects.

Figure S1. Flow chart with patient numbers that were screened, randomised and assigned to the two treatment arms (Placebo EPIT vs Allergen EPIT) and treated accordingly.

Figure S2. (A) Flow chart showing skin pre-treatment before administration of the first patch. (B) Comparison of improvement/deterioration of hay fever symptoms after allergen EPIT between subgroups receiving tape-stripping or abrasion as skin pre-treatment prior to first patch administration.

References

- 1.Ring J, Gutermuth J. 100 years of hyposensitization: history of allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT) Allergy. 2011;66:713–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox LS, Larenas Linnemann D, Nolte H, Weldon D, Finegold I, Nelson HS. Sublingual immunotherapy: a comprehensive review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1021–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiel MA, Roder E, Gerth van Wijk R, Al MJ, Hop WC, Rutten-van Molken MP. Real-life compliance and persistence among users of subcutaneous and sublingual allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Igyarto BZ, Kaplan DH. Antigen presentation by Langerhans cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Moos S, Johansen P, Tay F, Graf N, Kundig TM, Senti G. Comparing safety of abrasion and tape-stripping as skin preparation in allergen-specific epicutaneous immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:965–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senti G, von Moos S, Tay F, Graf N, Sonderegger T, Johansen P, et al. Epicutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy ameliorates grass pollen-induced rhinoconjunctivitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled dose escalation study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senti G, Graf N, Haug S, Ruedi N, von Moos S, Sonderegger T, et al. Epicutaneous allergen administration as a novel method of allergen-specific immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lima MT, Wilson D, Pitkin L, Roberts A, Nouri-Aria K, Jacobson M, et al. Grass pollen sublingual immunotherapy for seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:507–514. doi: 10.1046/j.0954-7894.2002.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James LK, Shamji MH, Walker SM, Wilson DR, Wachholz PA, Francis JN, et al. Long-term tolerance after allergen immunotherapy is accompanied by selective persistence of blocking antibodies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Moos S, Johansen P, Waeckerle-Men Y, Mohanan D, Senti G, Haffner A, et al. The contact sensitizer diphenylcyclopropenone has adjuvant properties in mice and potential application in epicutaneous immunotherapy. Allergy. 2012;67:638–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creticos PS, Schroeder JT, Hamilton RG, Balcer-Whaley SL, Khattignavong AP, Lindblad R, et al. Immunotherapy with a ragweed-toll-like receptor 9 agonist vaccine for allergic rhinitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1445–1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mothes N, Heinzkill M, Drachenberg KJ, Sperr WR, Krauth MT, Majlesi Y, et al. Allergen-specific immunotherapy with a monophosphoryl lipid A-adjuvanted vaccine: reduced seasonally boosted immunoglobulin E production and inhibition of basophil histamine release by therapy-induced blocking antibodies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:1198–1208. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bal SM, Ding Z, van Riet E, Jiskoot W, Bouwstra JA. Advances in transcutaneous vaccine delivery: do all ways lead to Rome? J Control Release. 2010;148:266–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheiblhofer S, Thalhamer J, Weiss R. Laser microporation of the skin: prospects for painless application of protective and therapeutic vaccines. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2013;10:761–773. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.773970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valenta R, Niespodziana K, Focke-Tejkl M, Marth K, Huber H, Neubauer A, et al. Recombinant allergens: what does the future hold? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:860–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Methods.

Table S1. Study outline.

Table S2. Baseline characteristics.

Table S3. Side effects.

Figure S1. Flow chart with patient numbers that were screened, randomised and assigned to the two treatment arms (Placebo EPIT vs Allergen EPIT) and treated accordingly.

Figure S2. (A) Flow chart showing skin pre-treatment before administration of the first patch. (B) Comparison of improvement/deterioration of hay fever symptoms after allergen EPIT between subgroups receiving tape-stripping or abrasion as skin pre-treatment prior to first patch administration.