Abstract

Objective

To investigate reproducibility of outcomes for short-term associations between ambient air pollutants and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) hospitalisation in 2 urban populations.

Design

Using a time-stratified design, we conducted independent case-crossover studies of AMI hospitalisation events over the period 1999–2010 in the geographically close and demographically similar cities of Calgary and Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Patients with his/her first AMI hospitalisation event were linked with air pollution data from the National Ambient Pollution Surveillance database and meteorological data from the National Climatic Data Center database. Patients were further divided into subgroups to examine adjusted pollution effects. Effects of pollution levels with 0–3-day lag were modelled using conditional logistic regression and adjusted for daily average ambient temperature, dew point temperature and wind speed.

Setting

Population-based studies in Calgary/Edmonton.

Participants

12 066/10 562 first-time AMI hospitalisations in Calgary/Edmonton.

Main outcome measures

Association (adjusted OR) between daily ambient air pollution levels and hospitalisation for AMI.

Results

Among 600 potential air pollution effect variables investigated for the Calgary (Edmonton) population, only 1.17% (0.67%) was statistically significant by using the traditional 5% criterion. None of the effect variables were reproduced in the 2 cities, despite their geographic closeness (within 300 km of each other), and demographic and air pollution similarities.

Conclusions

Comparison of independent investigations of the effect of air pollution on risk of AMI hospitalisation in Calgary and Edmonton, Alberta, indicated that none of the air pollutants investigated—CO, NO, NO2, O3 and particulate matter (PM2.5)—showed consistent positive associations with increased risk of AMI hospitalisation.

Keywords: air pollution, acute mycardial infarction, case-crossover, reproducibility

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We considered reproducibility of air pollution effects on risk of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) hospitalisation in two Alberta cities.

We separately investigated a variety of air pollutants (CO, NO, NO2, O3 and particulate matter (PM2.5)) in each city.

We did not include SO2 because of data limitations.

We focused on reproducibility of findings as a step in identifying important associations between air pollution and AMI hospitalisation in the major population centres of Alberta.

Introduction

Numerous epidemiological studies have described evidence of adverse associations between air pollution and hospital admission or emergency room visits for myocardial infarction (MI).1–21 This included a recent systematic review that reported significant associations with MI for all air pollutants except ozone (O3).2 While the associations are to some extent plausible, mechanisms underlying these associations are not fully understood.19 In addition, concerns persist about the modelling approach, covariate selection and other confounders that can lead to very different results.22 23 To highlight this, we summarised literature from PubMed related to case-crossover studies of relationships between particulate matter (PM) air pollution and MI published before 15 March 2015. Nineteen studies3–21 of PM and MI with greater than 1000 MI events were identified and are listed in table 1. From table 1, it can be observed that study findings do not always agree with each other, even for studies with very large numbers of observations.3 5 19

Table 1.

Review of case-crossover studies in literature for association between PM and MI

| Study | Location | Participants | Exposure | Design | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talbott et al3 | Washington DC and 4 east coast US states | 688 715 cases of MI | PM2.5 | Time-stratified | No association for lag 0 and 1 day with acute MI in 2 east coast states for all seasons |

| Wichmann et al4 | Gothenburg, Sweden | 28 215 cases of MI | PM10, soot | Time-stratified | No association found |

| Milojevic et al5 | England and Wales | 452 343 cases of MI | PM2.5, PM10 | Time-stratified | No association found |

| Bard et al6 | Strasbourg, France | 2134 cases of MI | PM10 | Time-stratified | No association found |

| Hodas et al7 | New Jersey, USA | 1561 HA for transmural MI (age ≥18) | PM2.5 | Time-stratified | Refined ambient PM2.5 (24 h average before onset) was associated with transmural MI |

| Rich et al8 | New Jersey, USA | 1562 HA for transmural MI (age ≥18) | PM2.5 species | Time-stratified | PM2.5 species (24 h average before onset) was associated with transmural MI |

| Kioumourtzoglou et al9 | 3 US cities | Emergency HA | OC species | Modified bidirectional | No association found |

| Tsai et al10 | Taipei, Taiwan | 27 563 HA for acute MI | PM10 | Time-stratified | No association found |

| Bhaskaran et al11 | England and Wales | 79 288 HA for MI | PM10 | Time-stratified | PM10 (1–6 h average before onset) was associated with acute MI |

| Nuvolone et al12 | Florence, Italy | 11 450 HA for acute MI | PM10 | Time-stratified | PM10 (lag 2 day) was associated with acute MI |

| Cadum et al13 | 10 Italian cities | HA for acute MI | PM10 | Time-stratified | PM10 was associated with acute MI |

| Rich et al14 | New Jersey, USA | 5864 HA for first-time AMI | PM2.5 | Time-stratified | PM2.5 (24 h average before onset) was associated with transmural MI |

| Hsieh et al15 | Taipei, Taiwan | 23 420 HA for MI | PM10 | Time-stratified | PM10 (3-day average before onset) was associated with MI |

| Cheng et al16 | Kaohsiung, Taiwan | 9349 HA for MI | PM10 | Time-stratified | PM10 (3-day average before onset) in cool days (<25°C) was associated with MI |

| Zanobetti and Schwartz17 | Boston, USA | 15 578 HA for acute MI | PM2.5, BC | Time-stratified | PM2.5 (lag 0-day) was associated with acute MI |

| Barnett et al18 | 5 cities in Australian and New Zealand | HA for CVD (age ≥15) | PM2.5, PM10 | Time-stratified | PM2.5 (24 h average before onset) was associated with MI |

| Zanobetti and Schwartz19 | 21 US cities | 302 453 HA for MI (age ≥65) | PM10 | Time-stratified | PM10 (lag 0-day) was associated with MI |

| Sullivan et al20 | Washington, USA | 5793 cases of acute MI | PM2.5, PM10 | Time-stratified | No association found |

| D'Ippoliti et al21 | Rome, Italy | 6531 HA for first-time AMI | TSP | Time stratified | TSP (lag 0–2 days) was associated with acute MI |

Here we focus only on studies of association between PM and MI, they could be partial results from larger studies. Only studies with >1000 MI events are reported.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BC, black carbon; HA, hospital admission; MI, myocardial infarction; OC, organic carbon; PM, particulate matter; TSP, total suspended particulate.

Another feature of the studies in table 1 was the difference in location of populations studied, including populations in cities of USA,3 7–9 14 17 19 20 Europe,4–6 11–13 21 Australia/New Zealand18 and Taiwan.10 15 16 Our interest was in understanding whether population characteristics might play a role in influencing outcomes for these types of studies. To explore this further, we hypothesised that two demographically similar Canadian cities with similar large populations, climate (weather) and air pollution characteristics should exhibit comparable (reproducible) air pollution effects for MI. We undertook and compared results for independent case-crossover studies in the two main cities of Alberta (Calgary and Edmonton) to test this hypothesis.

Calgary (∼1.10 million people, elevation 1045 m above sea level, latitude 51° 2′ N, longitude 114° 3′ W) and Edmonton (∼820 000 people, elevation 645 m above sea level, latitude 53° 32′ N, longitude 113° 29′ W) are geographically close to each other (<300 km apart) and both located on the east side of Rock Mountains in western Canada. The Calgary-Edmonton population centres and corridor in between is the most urbanised area in Alberta. Both cities have a relatively moderate semiarid climate with warm summers and cool winters. Both can be subject to wide variation in weather patterns; for example, temperature below −35°C in winter and above 35°C in summer. Both cities share similarities in air pollution characteristics (described later), population structure (age distributions), as well as in some important risk factors for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) disease (table 2). There are also dissimilarities between the cities, such as average prevalence rates of smoking, diabetes and obesity. Our objective was to establish whether air pollution effects for MI were consistent between the cities in order to confirm their reliability beyond traditional statistical significance (ie, p<0.5). Being able to independently reproduce results in the two cities leads to more realistic effects that represent our target population of interest (urban Alberta), not just Calgary or Edmonton.

Table 2.

Demographic information and important risk factors of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) for Edmonton and Calgary populations

| Prevalence in Calgary |

Prevalence in Edmonton |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMI risk factor | Both | Female | Male | Both | Female | Male |

| Smoking | 14.89 | 12.75 | 16.99 | 18.13 | 14.68 | 21.57 |

| Hypertension | 8.66 | 8.59 | 8.76 | 8.77 | 8.65 | 8.92 |

| Diabetes | 4.01 | 3.56 | 4.52 | 4.78 | 4.42 | 5.19 |

| Obesity | 15.07 | 13.20 | 16.77 | 17.16 | 15.22 | 18.93 |

| History of coronary heart disease | 2.40 | 1.79 | 3.06 | 2.34 | 1.72 | 3.02 |

| Age 0–19 years | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.26 |

| Age 20–64 years | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.61 |

| Age ≥65 years | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.13 |

| Unemployment | 4.10 | 4.40 | 3.90 | 4.70 | 4.70 | 4.80 |

Unemployment data for the two cities were from Census 2006 (http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/index-eng.cfm); all other data were from Alberta Interactive Health Data Application (http://www.ahw.gov.ab.ca/IHDA_Retrieval/) and calculated from annual prevalence rates over the period 2000–2010. Prevalence of smoking is the rate of current daily smokers; prevalence rate of obesity is the rate of people with body mass index ≥30; unemployment is the rate of unemployment for those aged 15 years or over.

Materials and methods

Data source

From the provincial ministry of health, we requested all historical records of hospital admission for AMI (International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10 code I21-I22 or ICD-9 code 410) for Calgary and Edmonton urban dwellers, respectively, for the study. We received de-identified records with a unique scrambled ID of first-time hospitalisation events for AMI occurring during 1 April 1999 to 31 March 2010 with patients aged 20 or over and living in the urban areas of both Calgary and Edmonton. Forward sortation areas (FSAs) are geographical regions in Canada in which all postal codes start with the same three characters. Patients in urban Calgary and Edmonton eligible for the study were from FSAs shown in online supplementary file 1.

We classified a patient's event with an AMI code as I214 (ICD-10) or 4107 (ICD-9) as having non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and the others as ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The validity of NSTEMI/STEMI classification in the early years of the data set was uncertain. Because of this we only considered first-time hospitalisation events for AMI occurring during 1 April 2002 to 31 March 2010 for classification of NSTEMI/STEMI. Secondary diagnosis codes (diagnosis 2–25) were used to define comorbidities for each patient, including hypertension (ICD-10 codes I10-I13 and I15, or ICD-9 codes 401), diabetes (ICD-10 codes E10-E14, or ICD-9 codes 250) and dysrhythmia (ICD-10 codes I47-I49, or ICD-9 codes 427). First-time hospitalisation events for AMI occurring during 1 April 1999 to 31 March 2010 were used for classification of these comorbidities.

Sex and age (at the start date of an AMI hospitalisation event) were used to define four subcohorts (male, female, patients age <65, patients age ≥65). Patients in the main cohort or in one of the four subcohorts were further divided into subgroups defined by AMI type or comorbidities, including all patients in the cohort or subcohort, patients with NSTEMI, patients with STEMI, patients with diabetes, patients with hypertension and patients with dysrhythmia.

Air pollution time-series data for Alberta were obtained from the Environment Canada National Ambient Pollution Surveillance (NAPS) database24 for the period 1 March 1999 to 30 April 2010. Four stations in the urban area of Calgary (NAPS ID 90218, 90222, 90228 and 90302) and four stations in urban area of Edmonton (NAPS ID 90120, 90121, 90122 and 90130) provide hourly records of five criteria air pollutants—that is, carbon monoxide (CO), nitric oxide (NO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), O3 and particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 µm (PM2.5). Daily average levels of the five pollutants were calculated from hourly concentration and further averaged across the four stations. The time series of daily average levels of the five pollutants were linked with AMI hospitalisation data for each of the two cities. We did not consider sulfur dioxide (SO2) in the analysis because of lack of data. SO2 is primarily monitored at stations close to industrial activities which, for the most part, are located away from where the populations are in Alberta.

Daily meteorological data during the study period were obtained from the US National Climatic Data Center (NCDC).25 Four stations in the metropolitan area of Calgary (NCDC ID 712350, 713930, 718770 and 718778) and four stations in metropolitan area of Edmonton (NCDC ID 711210, 711570, 713510 and 718790) provide historical daily meteorological records for air temperature (daily average, minimum and maximum temperature in °C), daily average dew point temperature (in °C) and daily average wind speed (in knots). These records were further averaged across the four stations to represent daily average levels of temperature, dew point temperature and wind speed in each city. These time-series data were linked with AMI data for each of the two cities.

Study design and analysis

The case-crossover design26 was used to study each city separately. The case-crossover design was developed from the case–control design to study associations of transient exposures with acute events. An investigator samples only cases with this design and compares each patient's exposure during a short time period just before a case event (hazard period) with the participant's exposure at other times (reference periods) without leading to case event.26 Because there is almost perfect matching of all measured and unmeasured individual characteristics that do not vary or that vary slowly over time (ie, age, gender, education, social economic status, personal lifestyle characteristics, body mass index, comorbidity conditions, etc), this design intrinsically adjusts for these characteristics.

The k-th day (k ranging from 0 to 3) before onset of an AMI hospital admission was selected as the hazard exposure period for a patient in the cohort. A time-stratified reference-selection design27 28 was used for selection of the reference periods. The whole study period was stratified into calendar months, and all days in the same year, same month and matching weekday of the hazard exposure day were selected as controls. A time-stratified reference-selection design is reported as a preferred approach for minimising referents that are not chosen a priori and are functions of the observed event times (referred to as overlap bias).29

A conditional logistic regression model was fitted and statistical parameters (coefficient, p value, OR and lower/upper bounds of 95% CI) were calculated for each of the cities and each of 600 effect variables, defined by five cohort or subcohorts (main, male, female, agecat1 (age <65), agecat2 (age ≥65)), six subgroups (whole, STEM, NSTEMI, hypertension, diabetes, dysrhythmia), five pollutants (CO, NO, NO2, O3, PM2.5) and 4 lag times (0–3 days). Each of the models was adjusted with three metrological variables (daily average of temperature, dew point temperature and wind speed). A stepwise selection procedure was adopted to eliminate redundant meteorological variables with critical level for variable entry and critical level for variable stay in the model both set at 0.25. Coefficient estimation and OR estimation were calculated for the IQR difference (between the 25th and the 75th centiles) for the covariate of interest. For example, for female hypertension patients, we built a logistic regression model on a subset of the data (for Edmonton or Calgary) that included all female hypertension records in each cohort when checking whether 3-day lag daily average PM2.5 level was associated with AMI hospitalisation. The model included one variable for 3-day lag PM2.5 level and three variables for 3-day lag meteorological condition.

Results

Descriptive analysis

There were a total of 12 066 (10 562) first-time AMI hospitalisation events in the urban areas of Calgary and Edmonton over the period 1 April 1999 to March 2010—an average of 2.62 (3.00) hospitalisations per day. The number of hospitalisations for predefined subgroups is listed in table 3.

Table 3.

First-time hospitalisations for acute myocardial infarction in different subgroups

| City | Cohort | Whole | STEMI | NSTEMI | HTN | Diabetes | Dysrhythmia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary | Main | 12 066 (100%) | 4206 (34.9%) | 4834 (40.1%) | 6060 (50.2%) | 2844 (23.6%) | 2127 (17.6%) |

| Male | 8191 (67.9%) | 3009 (24.9%) | 3106 (25.7%) | 3846 (31.9%) | 1858 (15.4%) | 1413 (11.7%) | |

| Female | 3875 (32.1%) | 1197 (9.9%) | 1728 (14.3%) | 2214 (18.3%) | 986 (8.2%) | 714 (5.9%) | |

| Agecat1 | 5330 (44.2%) | 2210 (18.3%) | 1804 (15.0%) | 2240 (18.6%) | 1068 (8.9%) | 585 (4.8%) | |

| Agecat2 | 6736 (55.8%) | 1996 (16.5%) | 3030 (25.1%) | 3820 (31.7%) | 1776 (14.7%) | 1542 (12.8%) | |

| Edmonton | Main | 10 562 (100%) | 3492 (33.1%) | 4754 (45.0%) | 6154 (58.3%) | 2825 (26.7%) | 1935 (18.3%) |

| Male | 6991 (66.2%) | 2446 (23.2%) | 3008 (28.5%) | 3772 (35.7%) | 1773 (16.8%) | 1201 (11.4%) | |

| Female | 3571 (33.8%) | 1046 (9.9%) | 1746 (16.5%) | 2382 (22.6%) | 1052 (10.0%) | 734 (6.9%) | |

| Agecat1 | 4613 (43.7%) | 1813 (17.2%) | 1790 (16.9%) | 2262 (21.4%) | 1039 (9.8%) | 449 (4.3%) | |

| Agecat2 | 5949 (56.3%) | 1679 (15.9%) | 2964 (28.1%) | 3892 (36.8%) | 1786 (16.9%) | 1486 (14.1%) |

Frequency of STEMI and NSTEMI was based on the period 1 April 2002 to 31 March 2010; frequency of other subgroups was based on the period 1 April 1999 to 31 March 2010. Percentages=number of patients in subgroup divided by 12 066 (for Calgary) or 10 562 (for Edmonton).

Agecat1, age <65; Agecat2, age ≥65; HTN, hypertension; NSTEMI, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction.

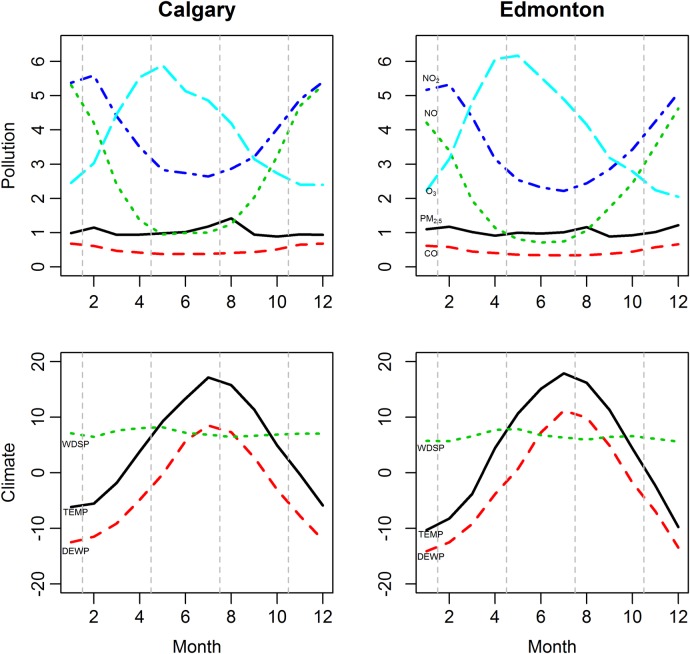

Figure 1 shows a summary of monthly average concentrations of the five air pollutants and the three climate factors over the 1 April 1999 to 31 March 2010 period in the two cities. Monthly average air pollution concentrations were not widely divergent among the cities. Obvious seasonal trends are apparent for several of the air pollutants. Much higher (lower) NO and NO2 levels occur during winter (summer) which is opposite to that of O3, which has lower (higher) levels occurring during winter (summer). The highest monthly PM2.5 levels occur during the summer period (mid-June to mid-September). Overall, figure 1 did not indicate any major differences in monthly average pollution levels and trends between Calgary and Edmonton.

Figure 1.

Seasonal trends of monthly average concentrations of air pollutants and monthly levels of climate factors (April 1999–March 2010). Left (right) column represents Calgary (Edmonton); while the top (bottom) row represents pollution (climate) levels. Unit of the monthly average concentrations of pollutants was adjusted: CO (1 unit=1 mg/m3); NO (1 unit=10 µg/m3); NO2 (1 unit=10 µg/m3); O3 (1 unit=10 µg/m3); PM2.5, fine particulate matter (1 unit=10 µg/m3). Unit of the monthly average values of climate factors: TEMP, temperature (1 unit=1°C); DEWP, dew point temperature (1 unit=1°C); WDSP, wind speed (1 unit=0.1 knots).

Estimated effects of the pollutants

The same analysis procedure—time-stratified case-crossover design and conditional logistic regression—was repeated for each of the cities and each of the 600 effect variables. For each model, we focused on reporting the estimated effect of an air pollution variable, which was adjusted with the three meteorological factors (daily mean temperature, dew point temperature and wind speed). Parameter estimates for all 600 effect variables (including coefficient, SD, p value, and OR and 95% CI) for Calgary and Edmonton are saved in the online supplementary file 2. Variables with estimated p value less than 0.05 are summarised in table 4. There were 7 (4) effect variables that exhibited significant associations (p<0.05) in Calgary (Edmonton) from 600 effect variables examined (table 4). If results for only a single city (Calgary or Edmonton) are reported, most of the variables in table 4 for that city could be suggested as exhibiting positive associations with AMI hospitalisations. However, comparing the findings from each city allows us to consider the issue of reproducibility of effects.30 31 As stated previously, both cities share similarities in air pollution levels (figure 1) as well as in some important risk factors for AMI disease (table 2) and similar air pollution effects for MI would be anticipated for each city.

Table 4.

Parameter and OR estimates for multivariate logistic regression models

| Cohort | Subgroup | N | Variable | Lag | Estimate | SE | p Value | OR | Lower CL | Upper CL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary | ||||||||||

| Main | Whole | 12 066 | NO2 | 1 | 0.0452 | 0.0194 | 0.0199 | 1.046 | 1.007 | 1.087 |

| Female | Whole | 3875 | NO2 | 1 | 0.0709 | 0.0342 | 0.0381 | 1.073 | 1.004 | 1.148 |

| Female | NSTEMI | 1728 | PM2.5 | 0 | –0.0627 | 0.0319 | 0.0489 | 0.939 | 0.882 | 1.000 |

| Agecat1 | Dysrhythmia | 585 | PM2.5 | 1 | –0.1285 | 0.0589 | 0.0292 | 0.879 | 0.784 | 0.987 |

| Agecat2 | Whole | 6736 | CO | 1 | 0.0264 | 0.0130 | 0.0428 | 1.027 | 1.001 | 1.053 |

| Agecat2 | Whole | 6736 | NO | 1 | 0.0324 | 0.0139 | 0.0193 | 1.033 | 1.005 | 1.061 |

| Agecat2 | Whole | 6736 | NO2 | 1 | 0.0734 | 0.0260 | 0.0047 | 1.076 | 1.023 | 1.132 |

| Edmonton | ||||||||||

| Main | Diabetes | 2825 | PM2.5 | 3 | 0.0532 | 0.0247 | 0.0314 | 1.055 | 1.005 | 1.107 |

| Main | Dysrhythmia | 1935 | PM2.5 | 0 | –0.0616 | 0.0312 | 0.0480 | 0.940 | 0.885 | 0.999 |

| Agecat1 | Whole | 4613 | PM2.5 | 1 | 0.0397 | 0.0192 | 0.0391 | 1.040 | 1.002 | 1.080 |

| Agecat1 | Diabetes | 1039 | PM2.5 | 1 | 0.0836 | 0.0423 | 0.0485 | 1.087 | 1.001 | 1.181 |

Data were calculated for an IQR increase of CO (0.27 mg/m3), NO (26.3 µg/m3), NO2 (21.9 µg/m3), O3 (26.7 µg/m3), PM2.5 (7.1 µg/m3) in the Calgary study, or of CO (0.27 mg/m3), NO (20 µg/m3), NO2 (23.8 µg/m3), O3 (30 µg/m3), PM2.5 (7.8 µg/m3) in the Edmonton study. Frequency of NSTEMI was based on the period 1 April 2002 to 31 March 2010; frequency of other subgroups was based on the period 1 April 1999 to 31 March 2010.

Agecat1, age <65; Agecat2, age ≥65; CL, 95% confident level; N, number of first-time hospitalisations for acute myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; PM, particulate matter.

Table 4 illustrates that all of the effect variables exhibiting positive associations with AMI hospitalisations are not reproduced for each city; significant effect variables identified in Calgary were not reproduced in Edmonton, and vice versa. For example, NO2 was suggested as a risk factor for several subgroups identified in Calgary, whereas no positive effect was found for NO2 in any of the subgroups identified in Edmonton in table 4. Likewise, PM2.5 was suggested to be a risk factor for several Edmonton subgroups, whereas no positive effect was found for PM2.5 in any of the subgroups identified in Calgary.

Discussion

Among the 600 potential effect variables investigated for the study in Calgary (Edmonton), we found that only 1.17% (0.67%) was statistically significant by using the traditional 5% criterion. None of the associations was reproduced in the two cities. A previous time-series analysis of emergency department visits for angina/MI at 14 hospitals in seven Canadian cities, including Edmonton, during the 1990s and early 2000s examined associations with CO, NO2, O3 and PM2.5.32 The strongest associations with increased emergency department visits for angina/MI were only related to 24 h average concentrations of CO and NO2 lag 0 days in Edmonton, but not for any of the other Canadian cities studied (Halifax, Montreal, Ottawa, Saint John, Toronto and Vancouver). Our study observed increased hospital visits for AMI with several subgroups in Calgary associated with 24 h average concentrations of CO and NO2 lag 1 day, but not in Edmonton (table 4). As stated previously, different modelling approaches, covariate selection and other confounders22 23 and different data sets can lead to dissimilar results.

Lack of reproducibility of a PM2.5 pollution effect on AMI in our study is not completely unexpected. Although numerous studies have reported PM2.5 as an important risk factor for MI,7 8 14 17 18 including a recent systematic review concluding that most air pollutants were associated with increased short-term risk of MI,2 an earlier review stated that less than half of literature studies showed clear evidence of elevated MI risk from exposure to air pollutants.1

In light of this, we believe that being able to reproduce findings from independent investigations employing similar methods is a useful feature for exploring air pollution effects. It is worthwhile to examine possible reasons for differences in most of the findings for these two cities. First, we speculate that there are differences in population characteristics at the individual level that the analysis did not account for—such as an omitted risk factor or a difference in air pollution exposure, susceptibility and/or response—in the two cities. If this is true, we should seek out these differences and further investigate air pollution-health associations at the individual level separately for each city. Meta-analysis would be unreasonable because of a specific effect instead of a random effect among the two cities. The data on population characteristics (table 2), monthly average air pollution characteristics (figure 1) and air pollutant IQR concentrations used in the analysis for each city (table 4) are not widely divergent such that a specific difference(s) among the two cities might be an explanation.

Second, differences in the findings of table 4 may be attributed to a weak association33 between air pollution and AMI hospitalisation in each city and/or a false finding.34 If this is true, larger scale data sets would be needed to reveal these associations with sufficient power. From a practical point of view, we should be ignoring weak associations. If we had to depend on a large number of health events (eg, over 300 000 AMI events3 5 19) to demonstrate a weak association between air pollutants and a health outcome, the findings would be less meaningful in public health practice.

The study was an exploratory analysis comparing independent investigations of air pollution effects on risk of AMI hospitalisation in two geographically close and demographically similar cities of Alberta, Canada. It was assumed that both cities had large enough populations to satisfy epidemiological design criteria. We emphasised reproducibility of findings in the investigations as a way to explore air pollution effects on risk of hospitalisation of urban populations in Alberta. This approach, in our view, was a simple way to identify associations between air pollution and short-term health outcomes in these urban populations. The study was limited in that it was an ecological study with the exposure variables (air pollutants and meteorological variables) measured at central monitoring locations, and thus they did not represent actual exposures for patients with AMI. In addition, we only considered effects from CO, NO, NO2, O3 and PM2.5. Because of data limitations we could not consider other potentially important factors such as SO2, other factors (eg, alcohol consumption, physical activity), exposure location prior to onset of AMI (eg, outdoor vs indoor) or special drug usage prior to onset of AMI.

Summary

Comparison of independent investigations of air pollution effects on risk of AMI hospitalisation in Calgary and Edmonton, Alberta, indicated that none of the pollutants investigated—including CO, NO, NO2, O3 and PM2.5—showed consistent positive associations with increased risk of AMI hospitalisation. The methodology used here is proposed as a way to explore reproducibility of air pollution effects on risk of hospitalisation of urban populations in Alberta.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Alberta Health Public Health Information Network project.

Footnotes

Contributors: XW participated in the design of the study, contributed in the acquisition of air pollution and meteorological data, performed the statistical analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript. WK conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. PK contributed in the acquisition of health data. All authors read the draft paper, provided critical comments and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board-Health Panel (IREB Pro00010852).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Air pollution data are freely available and can be accessed from the Environment Canada National Ambient Pollution Surveillance (NAPS) database.24 Daily meteorological data can be obtained from the United States National Climatic Data Center (NCDC).24 The health administrative data can be obtained with an ethics approval by contacting one of the co-authors who now resides with an agency that provides anonymised and de-identified health administrative data to researchers: XW, Research Innovation & Analytics, Alberta Health Services, 7235 2nd Floor, West Wing 11402 University Avenue Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2J3. Email: Xiaoming.Wang@albertahealthservices.ca; Tel: (780) 407-4679; Fax: (780) 407-8979.

References

- 1.Bhaskaran K, Hajat S, Haines A et al. Effects of air pollution on the incidence of myocardial infarction. Heart 2009;95:1746–59. 10.1136/hrt.2009.175018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mustafic H, Jabre P, Caussin C et al. Main air pollutants and myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;307:713–21. 10.1001/jama.2012.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talbott EO, Rager JR, Benson S et al. A case-crossover analysis of the impact of PM(2.5) on cardiovascular disease hospitalizations for selected CDC tracking states. Environ Res 2014;134:455–65. 10.1016/j.envres.2014.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wichmann J, Sjöberg K, Tang L et al. The effect of secondary inorganic aerosols, soot and the geographical origin of air mass on acute myocardial infarction hospitalisations in Gothenburg, Sweden during 1985–2010: a case-crossover study. Environ Health 2014;13:61 10.1186/1476-069X-13-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milojevic A, Wilkinson P, Armstrong B et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on a range of cardiovascular events in England and Wales: case-crossover analysis of the MINAP database, hospital admissions and mortality. Heart 2014;100:1093–8. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bard D, Kihal W, Schillinger C et al. Traffic-related air pollution and the onset of myocardial infarction: disclosing benzene as a trigger? A small-area case-crossover study. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e100307 10.1371/journal.pone.0100307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodas N, Turpin BJ, Lunden MM et al. Refined ambient PM2.5 exposure surrogates and the risk of myocardial infarction. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2013;23:573–80. 10.1038/jes.2013.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rich DQ, Özkaynak H, Crooks J et al. The triggering of myocardial infarction by fine particles is enhanced when particles are enriched in secondary species. Environ Sci Technol 2013;47:9414–23. 10.1021/es4027248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kioumourtzoglou MA, Zanobetti A, Schwartz JD et al. The effect of primary organic particles on emergency hospital admissions among the elderly in 3 US cities. Environ Health 2013;12:68 10.1186/1476-069X-12-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai SS, Chen PS, Yang YH et al. Air pollution and hospital admissions for myocardial infarction: are there potentially sensitive groups? J Toxicol Environ Health A 2012;75:242–51. 10.1080/15287394.2012.641202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhaskaran K, Hajat S, Armstrong B et al. The effects of hourly differences in air pollution on the risk of myocardial infarction: case crossover analysis of the MINAP database. BMJ 2011;343:d5531 10.1136/bmj.d5531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nuvolone D, Balzi D, Chini M et al. Short-term association between ambient air pollution and risk of hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction: results of the cardiovascular risk and air pollution in Tuscany (RISCAT) study. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:63–71. 10.1093/aje/kwr046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cadum E, Berti G, Biggeri A et al. The results of EpiAir and the national and international literature (article in Italian). Epidemiol Prev 2009;33(6 Suppl 1):113–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rich DQ, Kipen HM, Zhang J et al. Triggering of transmural infarctions, but not nontransmural infarctions, by ambient fine particles. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:1229–34. 10.1289/ehp.0901624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh YL, Yang YH, Wu TN et al. Air pollution and hospital admissions for myocardial infarction in a subtropical city: Taipei, Taiwan. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2010;73:757–65. 10.1080/15287391003684789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng MF, Tsai SS, Yang CY. Air pollution and hospital admissions for myocardial infarction in a tropical city: Kaohsiung, Taiwan. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2009;72:1135–40. 10.1080/15287390903091756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Air pollution and emergency admissions in Boston, MA. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:890–5. 10.1136/jech.2005.039834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett AG, Williams GM, Schwartz J et al. The effects of air pollution on hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease in elderly people in Australian and New Zealand cities. Environ Health Perspect 2006;114:1018–23. 10.1289/ehp.8674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. The effect of particulate air pollution on emergency admissions for myocardial infarction: a multicity case-crossover analysis. Environ Health Perspect 2005;113:978–82. 10.1289/ehp.7550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan J, Sheppard L, Schreuder A et al. Relation between short-term fine-particulate matter exposure and onset of myocardial infarction. Epidemiology 2005;16:41–8. 10.1097/01.ede.0000147116.34813.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Ippoliti D, Forastiere F, Ancona C et al. Air pollution and myocardial infarction in Rome: a case-crossover analysis. Epidemiology 2003;14:528–35. 10.1097/01.ede.0000082046.22919.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koop G, McKitrick R, Tole L. Air pollution, economic activity and respiratory illness: evidence from Canadian cities, 1974–1994. Environ Model Software 2010;25:873–85. 10.1016/j.envsoft.2010.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stylianou M, Nicolich MJ. Cumulative effects and threshold levels in air pollution mortality: data analysis of nine large US cities using the NMMAPS dataset. Environ Pollut 2009;157:2216–23. 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Air Pollution Surveillance Network, Environment Canada. http://www.etc-cte.ec.gc.ca/NapsData/Default.aspx (accessed Jan 2013).

- 25.Land-Based Station Data, National Climatic Data Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/land-based-station-data (accessed Jan 2013).

- 26.Maclure M. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133:144–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy D, Lumley T, Sheppard L et al. Referent selection in case-crossover analyses of acute health effects of air pollution. Epidemiology 2001;12:186–92. 10.1097/00001648-200103000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janes H, Sheppard L, Lumley T. Case-crossover analyses of air pollution exposure data—referent selection strategies and their implications for bias. Epidemiology 2005a;16:717–26. 10.1097/01.ede.0000181315.18836.9d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janes H, Sheppard L, Lumley T. Overlap bias in the case-crossover design, with application to air pollution exposures. Stat Med 2005;24:285–300. 10.1002/sim.1889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernán MA, Wilcox AJ. Epidemiology, data sharing, and the challenge of scientific replication. Epidemiology 2009;20:167–8. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318196784a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng RD, Dominici F, Zeger SL. Reproducible epidemiologic research. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:783–9. 10.1093/aje/kwj093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stieb DM, Szyszkowicz M, Rowe BH et al. Air pollution and emergency department visits for cardiac and respiratory conditions: a multi-city time-series analysis. Environ Health 2009;8:25 10.1186/1476-069X-8-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz J. Particulate air pollution and mortality: a synthesis. Public Health Rev 1991;19:39–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ioannidis JA. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med 2005;2:e124–30. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]