Abstract

Objectives

Fluoroquinolone-associated tendon ruptures are a recognised complication, but other severe collagen-associated adverse events may also be possible. Our objectives were to confirm the association of fluoroquinolones and tendon rupture, to clarify the potential association of fluoroquinolones and retinal detachment, and to test for a potentially lethal association between fluoroquinolones and aortic aneurysms.

Setting

Population-based longitudinal cohort study in Ontario, Canada.

Participants

Older adults turning 65 years between April 1 1997 and March 31 2012 were followed until primary outcome, death, or end of follow-up (March 31 2014). Fluoroquinolone prescriptions were measured as a time-varying covariate, with patients considered at risk during and for 30 days following a treatment course.

Primary outcome measures

Severe collagen-associated adverse events defined as tendon ruptures, retinal detachments and aortic aneurysms diagnosed in hospital and emergency departments.

Results

Among the 1 744 360 eligible patients, 657 950 (38%) received at least one fluoroquinolone during follow-up, amounting to 22 380 515 days of treatment. The patients experienced 37 338 (2.1%) tendon ruptures, 3246 (0.2%) retinal detachments, and 18 391 (1.1%) aortic aneurysms. Severe collagen-associated adverse events were more common during fluoroquinolone treatment than control periods, including tendon ruptures (0.82 vs 0.26/100-person years, p<0.001), retinal detachments (0.03 vs 0.02/100-person-years, p=0.003) and aortic aneurysms (0.35 vs 0.13/100-person-years, p<0.001). Current fluoroquinolones were associated with an increased hazard of tendon rupture (HR 3.13, 95% CI 2.98 to 3.28; adjusted HR 2.40, 95% CI 2.24 to 2.57) and an increased hazard of aortic aneurysms (HR 2.72, 95% CI 2.53 to 2.93; adjusted HR2.24, 95% CI 2.02 to 2.49) that were substantially greater in magnitude than the association of these outcomes with amoxicillin. The hazard of retinal detachment was marginal (HR 1.28, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.65; adjusted HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.00) and not greater in magnitude than that observed with amoxicillin.

Conclusions

Fluoroquinolones are associated with subsequent tendon ruptures and may also contribute to aortic aneurysms.

Keywords: CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study reports a novel and important association of fluoroquinolone prescriptions with aortic aneurysms.

The study design involves a population-based, longitudinal analysis of 1.7 million older adults.

The findings are robust across multiple sensitivity, subgroup and tracer analyses.

Misclassification of fluoroquinolone exposure is possible, if some patients did not use their dispensed prescriptions.

Underdetection of mild or asymptomatic outcome events is possible.

Introduction

Fluoroquinolones are among the most frequently prescribed antibiotics,1–3 so that even rare toxicities can have large public health consequences. In 2008, the USA Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning for fluoroquinolones based on postmarketing surveillance data indicating that these medications were associated with subsequent tendonitis and tendon rupture.4 Several large epidemiological studies have confirmed this association.5 6 Secondary cell biology and animal research has elucidated the pathophysiology to involve upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases resulting in a reduction in the quantity and quality of collagen fibrils.7–9

Collagen is also a crucial component of the vitreous body and critical to maintaining retinal attachment. One large case–control study in British Columbia, revealed an increased risk of retinal detachment affecting 1/2500 patients prescribed a fluoroquinolone.10 In contrast, a subsequent cohort study in Denmark did not corroborate an increased risk.11 The potential association of fluoroquinolones with retinal detachment remains controversial, although it raises the possibility that fluoroquinolone-associated collagen toxicity might extend beyond the musculoskeletal system.

Type I and type III collagen comprise the majority of collagen in the Achilles tendon,9 and also comprise the majority (80–90%) of collagen in the aorta.12 Diseases of the aorta, including aortic aneurysms and dissections, are associated with alterations in collagen content, concentrations and structure.13 If fluoroquinolone-associated collagen degradation affects the aortic wall, these drugs would have the potential to cause aortic aneurysms. Such an association could be missed in routine clinical practice due to the very large numbers of patients required to be followed for an extended time.

In this population-based longitudinal cohort study we sought to confirm the association of fluoroquinolones with tendon rupture, explore the potential association of fluoroquinolones with retinal detachment, and test the previously unrecognised but potentially important association of fluoroquinolones with aortic aneurysms.

Methods

General study design

We conducted a population-based longitudinal cohort study of elderly patients in Ontario, Canada's most populous province, to assess whether fluoroquinolones were associated with an increased risk of subsequent collagen-associated severe adverse events. Patient confidentiality was maintained through privacy safeguards at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). Ethics approval was obtained from the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board including a waiver of informed consent.

Patient selection and follow-up

Using the Ontario Registered Persons Database we identified an inception cohort with uniform accrual of all Ontario adults turning age 65, during a 15-year period between 1 April 1997 and 31 March 2012. We excluded patients who remained less than 65 years throughout the study interval or the rare patients with a missing health card identifier under universal healthcare. We excluded younger patients because prescription data are not reliably available in Ontario for those less than 65 years old. Individuals were accrued on their 65th birthday and followed until death, an outcome event, or the end of the study period (31 March 2014), thereby providing a minimum of 2 years and a maximum of 17 years follow-up.

Fluoroquinolone prescriptions

Fluoroquinolone prescriptions were measured in the Ontario Drug Benefits (ODB) database which records medications prescribed to older Ontario patients. The database is comprehensive because the programme provides free medication to individuals over the age of 65, with minimal copayment. The database is accurate, yielding more than 99% concordance with pharmacy chart review.14 The database is well validated and has been used heavily in population-based research in Ontario,15 including prior studies of antibiotic treatment in general,16 and fluoroquinolone treatment in particular.3 17 The fluoroquinolones available in this setting included ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and ofloxacin. There was no information on inpatient fluoroquinolone use. We quantified fluoroquinolones based on the number of days of treatment supplied, and considered patients at risk for up to 30 days following a treatment course. We used a 30-day at risk window based on the observed time lapse from fluoroquinolone initiation to tendon complications in postmarketing surveillance reports (mean 18±24.5 d).18

Primary outcomes: collagen-associated adverse events

The primary study outcomes were collagen-associated severe toxicities, defined by International Classification of Diseases 9th and 10th diagnoses (ICD-9 and ICD-10) in the hospitalisation and emergency department databases. The outcomes included all tendons rupture (ICD-9 code 727.6, ICD-10 codes M620-M659), retinal detachments (ICD-9 code 361.0, ICD-10 code H330) and aortic aneurysms (ICD-9 code 441, ICD10 codes I710-I719).6 10 19 20 Among aortic aneurysm diagnoses we also measured the proportion that were complicated by aortic rupture or dissection (ICD-9 codes 441.0, 441.1, 441.2, 441.3, 441.5; ICD-10 codes I710–11, I1713, I715, I718) and the proportion that were labelled as the primary most responsible diagnoses.20

Additional risk factors

Using a 1-year look back-window in hospital,21 emergency department22 and physician23 databases, we measured baseline patient characteristics potentially associated with either the likelihood of a fluoroquinolone prescription or the likelihood of subsequent tendon rupture, retinal detachment or aortic aneurysm. We did not introduce a time dependent covariate for age because all patients were enrolled at their 65th birthday, so that age was already accounted for in duration of follow-up.24 25 Demographic risk factors included sex and income quintile; prior healthcare utilisation included total hospital admissions and physician visits in the year prior to enrolment; comorbidities of interest included prior urinary tract infections, prior pneumonia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, atherosclerosis (coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease), chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignancy, liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, hypothyroidism and depression.

Statistical analysis

We evaluated the overall amount of fluoroquinolone prescribed to patients for descriptive analyses by numbers of prescriptions and days of treatment per patient day of follow-up. We compared baseline patient characteristics among those who did and did not receive at least one fluoroquinolone prescription, with χ2 test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

The primary analyses examined the association of current fluoroquinolone treatment and the hazard of tendon rupture, retinal detachment or aortic aneurysm. Fluoroquinolone prescriptions were measured as a time-varying covariate, with a patient considered exposed for up to 30 days following each fluoroquinolone treatment course. Each outcome was examined in a separate multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to allow coefficients to differ for the primary predictor (fluoroquinolone exposure) as well as for other risk factors. Patients were censored on the primary outcome event, death or the end of the study. Models were examined with and without adjustment for demographic, healthcare utilisation and comorbidity variables. Owing to the large cohort size and lengthy longitudinal follow-up, multivariable models were performed on a 50% random subset of the study cohort and confirmed by replication on the remaining 50% subset of the cohort.

To test the robustness of findings we also performed a sensitivity analysis limited to only those patients who received at least one fluoroquinolone prescription during follow-up. We also performed prespecified subgroup analyses stratified by baseline patient characteristics, and also assessed the association separately for ciprofloxacin (the most common fluoroquinolone prescribed) compared to other fluoroquinolones. Given that aortic aneurysms can be diagnosed incidentally during admissions for other causes, we performed a sensitivity analysis limited to those aortic aneurysm events coded as primary diagnoses; given that aortic aneurysm admissions can sometimes relate to elective surgical repair, we performed another sensitivity analysis limited to emergency admissions for aortic aneurysm events.

To test the specificity of our findings, we tested for an absence of an association between amoxicillin prescriptions and the same adverse events (negative tracer exposure). To ensure the fidelity of our methods, we further tested the anticipated presence of an association between fluoroquinolones and the risk of Clostridium difficile infection (positive tracer outcome). This final tracer analysis was conducted on a subset of the cohort enrolled after 1 April 2002, because C. difficile codes were only available in Ontario hospital and emergency room databases from this time point forward.

Finally, we estimated the number of preventable tendon ruptures, retinal detachments and aortic aneurysms in our cohort if the numbers or durations of fluoroquinolone prescriptions were reduced by 50%. These calculations were extrapolated from the rate difference in these outcomes observed during time on fluoroquinolone treatment as compared to time off of fluoroquinolone treatment. All analyses were conducted in SAS Statistical Software V.9.3 (Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Fluoroquinolone use

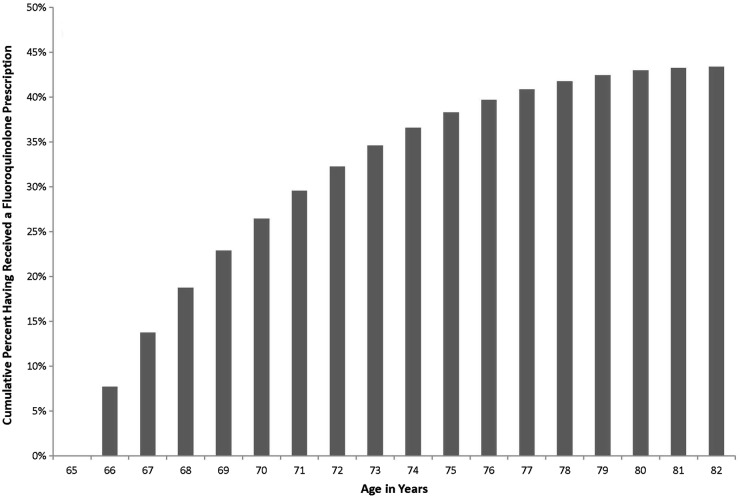

Between 1 April 1997 and 31 March 2012, we identified 1 744 360 patients who turned 65 years of age and were enrolled into the study. More than one-third received at least one fluoroquinolone prescription during follow-up (657 950, 38%), with a mean of 1.3±3.6 prescriptions per patient, amounting to a total of 2 260 994 fluoroquinolone prescriptions (figure 1). The most common fluoroquinolone was ciprofloxacin (50%), followed by norfloxacin (18%), moxifloxacin (16%), levofloxacin (15%) and ofloxacin (0.5%). The most common prescription duration was 7 days (35%), but nearly half the prescriptions exceeded 7 days (1 056 492, 47%). In total, we observed 22 380 515 total patient-days of fluoroquinolone treatment.

Figure 1.

Cumulative percentage of elderly patients exposed to at least one fluoroquinolone prescription with each advancing year of age beyond their 65th birthday.

Baseline characteristics of patients

Among the 1 744 360 patients who turned 65 years old during our study, about half were male (850 581; 49%), and many were diagnosed with hypertension (487 459, 28%), diabetes mellitus (231 805; 13%) or atherosclerotic disease (177 338, 10%). All baseline comorbidities were more common among the 657 950 (38%) patients who received at least one fluoroquinolone prescription compared to the 1 086 410 (62%) who received no fluoroquinolone prescription (table 1). Importantly, this study did not compare these two groups of patients, but rather considered periods of fluoroquinolone use among individual cohort members.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients prescribed and not prescribed fluoroquinolones

| Baseline characteristic | Overall n=1 744 360 |

Fluoroquinolone Yes* n=657 950 N (%) |

Fluoroquinolone No* n=1 086 410 N (%) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 65† | 65† | 65† | – |

| Sex—male | 850 481 (48.8) | 319 485 (48.6) | 530 996 (48.9) | <0.001 |

| Income quintile | 363 246 (20.8) | 137 594 (20.9) | 225 652 (20.8) | |

| 5 (highest) | ||||

| 4 | 339 798 (19.5) | 130 626 (19.9) | 209 172 (19.3) | |

| 3 | 332 740 (19.1) | 130 524 (19.8) | 202 216 (18.6) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 336 910 (19.3) | 132 211 (20.1) | 204 699 (18.8) | |

| 1 (lowest) | 310 477 (17.8) | 122 722 (18.7) | 187 755 (17.3) | |

| Healthcare utilisation—mean (SD) | ||||

| Hospital admissions in previous year | 0.09 (0.40) | 0.13 (0.48) | 0.07 (0.35) | <0.001 |

| Physician visits in previous year | 9.6 (11.7) | 12.8 (13.2) | 7.6 (10.2) | <0.001 |

| Comorbid illnesses | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 231 805 (13.3) | 106 894 (16.2) | 124 911 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 487 459 (27.9) | 216 062 (32.8) | 271 397 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| Atherosclerosis | 177 338 (10.2) | 90 521 (13.8) | 86 817 (8.0) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 34 580 (2.0) | 18 764 (2.9) | 15 816 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 115 205 (6.6) | 69 813 (10.6) | 45 392 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 42 876 (2.5) | 19 047 (2.9) | 23 829 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 39 286 (2.3) | 19 718 (3.0) | 19 568 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 7978 (0.5) | 4176 (0.6) | 3802 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 14 911 (0.9) | 6979 (1.1) | 7932 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 1701 (0.1) | 801 (0.1) | 900 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia in past year | 35 851 (2.1) | 21 704 (3.3) | 14 147 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Urinary tract infection in past year | 58 687 (3.4) | 38 041 (5.8) | 20 646 (1.9) | <0.001 |

*Here patients are compared according to any versus no prescriptions of fluoroquinolones during their entire follow-up, but in primary analyses fluoroquinolone prescriptions are measured as a time-varying covariate, with at-risk periods of patient-time during fluoroquinolone prescriptions compared to patient- time not on fluoroquinolones.

†Age at accrual is 65 years for all patients.

Severe collagen-associated adverse events

Tendon ruptures occurred in 37 338 patients (2.1%), retinal detachments in 3246 patients (0.2%) and aortic aneurysms in 18 391 patients (1.1%). Aortic aneurysms were clinically important given that 12 583 (68%) were coded as primary diagnoses, 9717 (53%) were emergency admissions, and 3126 (17%) resulted in rupture or dissection on initial diagnosis or during subsequent follow-up.

All three main outcomes were more common in patients who received at least one fluoroquinolone prescription than among patients who never received a fluoroquinolone prescription, including a higher risk of tendon rupture (3.5 vs 1.3%, p<0.001), retinal detachment (0.26 vs 0.14%, p<0.001) and aortic aneurysm (1.7 vs 0.7%, p<0.001). All three outcomes were distinctly more common during at-risk periods of current fluoroquinolone prescriptions than during time periods when patients were not prescribed fluoroquinolones including an increased rate of tendon rupture (0.82 vs 0.26 per 100-person years, p<0.001), retinal detachment (0.03 vs 0.02/100-person years, p=0.003) and aortic aneurysm (0.35 vs 0.13/100-person years, p<0.001). The median time from fluoroquinolone initiation to tendon rupture, retinal detachment and aortic aneurysm was 19, 20 and 20 days, respectively.

Relative risk of collagen-associated adverse events

Current fluoroquinolone use was associated with an increased hazard of tendon rupture (HR 3.13, 95% CI 2.98 to 3.28), and increased hazard of aortic aneurysms (HR 2.72, 95% CI 2.53 to 2.93). The relative hazard of these two collagen-associated adverse events were slightly attenuated after multivariate adjustment, but remained clinically meaningful and statistically significant (table 2). The relative hazard of retinal detachment was modest in magnitude, and only statistically significant after multivariate adjustment (table 2). The magnitude of the association of fluoroquinolones and aortic aneurysm events was stronger than the association observed with other aneurysm risk factors such as hypertension and atherosclerosis (table 3).

Table 2.

Current fluoroquinolone use* and the hazard of collagen-associated adverse events

| Antibiotic exposure outcome event | Unadjusted HR | 95% CI | Adjusted† HR |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoroquinolones | ||||

| Tendon rupture | 3.13 | 2.98 to 3.28 | 2.40 | 2.24 to 2.57 |

| Retinal detachment | 1.28 | 0.99 to 1.65 | 1.47 | 1.08 to 2.00 |

| Aortic aneurysm | 2.72 | 2.53 to 2.93 | 2.24 | 2.02 to 2.49 |

| Amoxicillin (negative tracer) | ||||

| Tendon rupture | 1.56 | 1.46 to 1.66 | 1.41 | 1.29 to 1.54 |

| Retinal detachment | 1.44 | 1.14 to 1.81 | 1.47 | 1.08 to 2.00 |

| Aortic aneurysm | 1.74 | 1.59 to 1.90 | 1.50 | 1.32 to 1.70 |

*Patients considered exposed during fluoroquinolone course and for 30 days following treatment.

†Adjusted for baseline characteristics including sex, income quintile, prior hospital admissions, prior physician visits, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, atherosclerosis, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypothyroidism, depression, inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, liver disease, prior pneumonia, prior urinary tract infection.

Table 3.

Multivariable model assessing association of fluoroquinolones with aortic aneurysm events

| Patient characteristic | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current fluoroquinolone use | 2.24 | 2.02 to 2.49 | <0.001 |

| Demographics | |||

| Sex—male | 3.23 | 3.08 to 3.39 | <0.001 |

| Income quintile | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 5 (highest) | |||

| 4 | 1.05 | 0.99 to 1.13 | 0.117 |

| 3 | 1.08 | 1.01 to 1.16 | 0.017 |

| 2 | 1.17 | 1.10 to 1.25 | <0.001 |

| 1 (lowest) | 1.20 | 1.12 to 1.28 | <0.001 |

| Healthcare utilisation | |||

| Hospital admissions in previous year | 1.05 | 1.01 to 1.10 | 0.029 |

| Physician visits in previous year | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.01 | <0.001 |

| Comorbid illnesses | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.65 | 0.61 to 0.70 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.33 | 1.28 to 1.39 | <0.001 |

| Atherosclerosis | 2.20 | 2.09 to 2.31 | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.49 | 1.32 to 1.69 | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.47 | 1.37 to 1.59 | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1.01 | 0.87 to 1.17 | 0.873 |

| Depression | 1.12 | 0.99 to 1.29 | 0.083 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 0.98 | 0.73 to 1.30 | 0.867 |

| Malignancy | 0.92 | 0.73 to 1.15 | 0.457 |

| Liver disease | 0.88 | 0.46 to 1.69 | 0.698 |

| Pneumonia in past year | 1.24 | 1.10 to 1.39 | <0.001 |

| Urinary tract infection in past year | 0.91 | 0.81 to 1.03 | 0.141 |

Aortic aneurysms diagnosed during fluoroquinolone prescriptions were no less severe than those diagnosed during periods when patients were not prescribed fluoroquinolones. The subsequent risk of rupture or dissection was 155/762 (20.3%) among aneurysms diagnosed during fluoroquinolone prescriptions, as compared to 2971/17629 (16.9%) among aneurysms diagnosed during periods without fluoroquinolone use.

Sensitivity analyses

The association of fluoroquinolones with collagen-associated severe adverse events was consistent in a sensitivity analysis limited to only those patients who had received at least one fluoroquinolone during follow-up (an analysis that excluded all patients that never received a fluoroquinolone during the course of the study). This analysis again yielded a substantial increased hazard of tendon rupture (HR 2.27, 95% CI 2.17 to 2.39) and aortic aneurysm (HR 2.01, 95% CI 1.87 to 2.17) and no significantly increased hazard of retinal detachment (HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.45).

The association of fluoroquinolone prescriptions and aortic aneurysms remained robust in a secondary analysis limited to events that were coded as primary diagnoses; the hazard of aortic aneurysm was higher during fluoroquinolone prescriptions in univariate (HR 2.39, 95% CI 2.18 to 2.62) and multivariate analyses (adjusted HR 2.03, 95% CI 1.77 to 2.32). The association of fluoroquinolone prescriptions and aortic aneurysms was accentuated in secondary analyses limited to emergency aneurysm admissions in both univariate (HR 3.93, 95% CI 3.61 to 4.27) and multivariate comparisons (adjusted HR 3.19, 95% CI 2.82 to 3.60). Finally, the association with fluoroquinolone use persisted when outcomes were limited to emergency admissions for aortic ruptures or dissections (HR 3.17, 95% CI 2.58 to 3.90; adjusted HR 2.84, 95% CI 2.32 to 3.50).

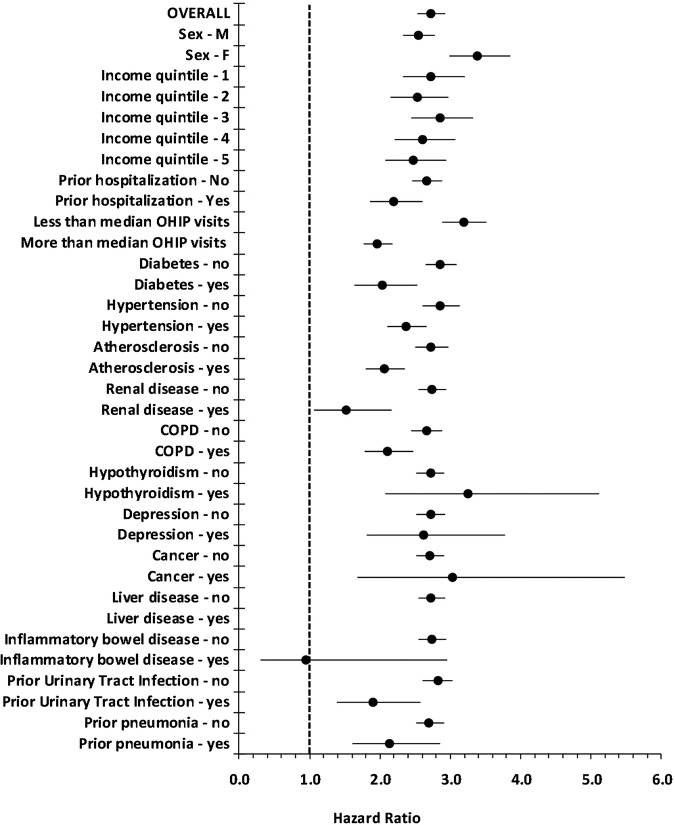

Subgroup analyses

The association of fluoroquinolones with subsequent aortic aneurysms was robust across multiple prespecified subgroups stratified by baseline demographic, healthcare utilisation and patient comorbidity (figure 2). The association extended to ciprofloxacin (adjusted HR 2.01, 95% CI 1.73 to 2.34) and other fluoroquinolones (adjusted HR 2.43, 95% CI 2.11 to 2.80).

Figure 2.

The association of fluoroquinolone prescriptions with the risk of aortic aneurysm events, stratified by baseline patient characteristics. OHIP visits=physician visits documented in Ontario Health Insurance Plan database.

Negative tracer exposure: amoxicillin

To test the specificity of the association of fluoroquinolones with collagen-associated adverse events, we examined for an absence of an association between amoxicillin and subsequent tendon rupture, retinal detachment and aortic aneurysm. Although amoxicillin was associated with tendon rupture and aortic aneurysm, the magnitude of this association was significantly more modest compared to fluoroquinolones; the 95% CIs were non-overlapping (table 2).

Positive tracer: fluoroquinolones and C. difficile infection

To test the fidelity of our approach examining a fluoroquinolone association with collagen-associated adverse events we tested for the expected association of fluoroquinolones with the recognised antibiotic complication of C. difficile infection. Current fluoroquinolone use was associated with a markedly increased risk of C. difficile (HR 14.8, 95% CI 13.9 to 15.7), which persisted after multivariable adjustment (adjusted HR 10.2, 95% CI 9.61 to 10.87).

Number of preventable adverse events

Based on the observed rate difference in adverse events during fluoroquinolone treatment compared to periods of no fluoroquinolone treatment, a 50% reduction in fluoroquinolone prescriptions or a 50% reduction in fluoroquinolone treatment durations would have resulted in an estimated reduction of 602 tendon ruptures, 245 aortic aneurysms and 11 retinal detachments in patients.

Discussion

In this longitudinal cohort of 1.7 million older patients, fluoroquinolone prescriptions were remarkably common, with more than one-third receiving at least one prescription, amounting to over 20 million days of total fluoroquinolone treatment. Overall, fluoroquinolones were associated with almost a tripling of the risk of tendon ruptures—a recognised collagen-associated adverse event induced by these medications. Fluoroquinolones were associated with a similar increase in the risk of aortic aneurysms—a more ominous complication that has not been previously described. The association of fluoroquinolones with aortic aneurysms was robust across patient subgroups and aneurysm severity, similar in magnitude to the risk associated with hypertension, persisted after multivariate adjustment for baseline patient characteristics, extended to the subsequent hazard of dissection or rupture, and significantly exceeded any association observed with amoxicillin. Reducing unnecessary fluoroquinolone treatments or prolonged treatment courses, might have possibly prevented more than 200 aortic aneurysms in this population.

Our findings agree with prior observational studies documenting a two to threefold increased risk of tendon ruptures with fluoroquinolones,26 27 and therefore support the USA Food and Drug Administration's black box safety warning.4 A prior case–control study describing an increased risk of retinal detachment with fluoroquinolones10 was not supported by the current analysis because we observed a modest estimate of the increased hazard of retinal detachment with fluoroquinolones that was not above that observed with amoxicillin and likely related to residual confounding. Our study is the first to observe an association of fluoroquinolones with aortic aneurysms.

Extensive cell biology and animal research has identified mechanisms by which fluoroquinolones lead to tendon rupture.7–9 These medications appear to upregulate multiple matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) including MMP-1,8 MMP-29 and MMP-13,8 resulting in reductions in the diameter7 and amount of type I collagen fibrils.8 9 Fluoroquinolones also cause degenerative changes in tenocyte cells, with vacuole formation,7 organelle dilatation7 and apoptosis.8 Collagen constitutes 70% of tendon dry weight, of which 90% is type I collagen and 10% is type III collagen.9 In the aortic wall, type I and type III are also the dominant forms of collagen,12 thereby suggesting that a medication contributing to tendon ruptures could also lead to aortic aneurysms. Indeed, pathological sections of aortic aneurysms and aortic dissections demonstrate abnormalities of collagen content, concentrations and ratios.13 Although aortic aneurysms typically develop slowly, our data suggest that fluoroquinolone prescriptions can contribute acutely to aneurysm progression and rupture.

The lack of an association of fluoroquinolones with retinal detachment may relate to differences in specific collagen types in retinal tissue. Type II collagen might be the critical type of collagen in retinal adhesion, given that type II collagen is present in abundance at the vulnerable vitreoretinal border,28 and recent research has linked a mutation in type II collagen with an autosomal dominant syndrome of vitreoretinopathy.29 Another potential explanation for the lack of observed association with retinal detachments, is that tendons and the aorta are exposed to high tension, unlike the retina. However, our study may have been underpowered to detect a small magnitude association, and we focused on a general population of elderly patients rather than only on those with a history of ophthalmology visits.10 Therefore, we have only added to the debate rather than providing a definitive answer regarding the potential association of fluoroquinolones and retinal detachment.

One limitation of our study is potential confounding-by-indication if infections were causally related to the outcome events. However, we doubt that infections are associated with collagen damage to this degree, and the association with fluoroquinolones far exceeded the association observed with amoxicillin (another antibiotic popular for treating community-acquired infections). Misclassification of fluoroquinolone exposure is possible, and we cannot be sure that patients complied with treatment. Misclassification of outcome events is also possible in administrative databases because these codes have not been directly validated.30 Diagnostic detection bias is unlikely given that aneurysms diagnosed following fluoroquinolone prescriptions were no less likely to rupture or dissect than those diagnosed during periods without fluoroquinolone use. Our outcome events can be multicausal (eg, tendon ruptures from osteonecrosis or trauma, retinal detachments from globe injuries, and aortic aneurysms from hypertension) which might dilute our estimates of relative hazard. We cannot rule out residual confounding, since our neutral tracer (amoxicillin) was not entirely null. Our population based analysis in a large jurisdiction enhances generalisability of our findings, but we cannot extrapolate to patients younger than 65 years old.

Our study confirms a doubling of the risk of tendon ruptures during fluoroquinolone treatment, checks the risk of retinal detachments with these medications, and identifies a novel association with aortic aneurysms. The findings suggest that patients receiving fluoroquinolone treatment could be warned about a rare but potentially lethal risk to the aorta. Although fluoroquinolones remain essential treatments for common bacterial infections, alternate agents or shorter courses might be considered for patients already diagnosed with an aortic aneurysm. In addition, aortic aneurysms should weigh on the mind of clinicians considering prescribing fluoroquinolones for inappropriate indications or durations.16 31 Reducing unnecessary fluoroquinolone prescriptions may be a simple and modifiable means to reduce the risk of aortic aneurysms in patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: ND and DAR conceived the study question, designed the analysis plan, interpreted the results of the analysis, and contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript. HL conducted the statistical analysis, aided in its interpretation, and helped to revise the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission. All authors contributed to conception of study design, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript for important content, and approval of the final version. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: ND is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) clinician scientist award. DAR is supported by a CIHR Canada Research Chair in Medical Decision Sciences. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are subject to the privacy and confidentiality safeguards of the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. For additional data analysis requests, please contact the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Steinman MA, Kaplan CM. Geographic variation in outpatient antibiotic prescribing among older adults. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1465–71. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linder JA, Huang ES, Steinman MA et al. . Fluoroquinolone prescribing in the United States: 1995 to 2002. Am J Med 2005;118:259–68. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mamdani M, McNeely D, Evans G et al. . Impact of a fluoroquinolone restriction policy in an elderly population. Am J Med 2007;120:893–900. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Information for Healthcare Professionals Black Box Warning Fluoroquinolones and Tendinitis and Tendon Rupture. 7-8-0008. 1-30-2014.

- 5.Wise BL, Peloquin C, Choi H et al. . Impact of age, sex, obesity, and steroid use on quinolone-associated tendon disorders. Am J Med 2012;125:1228 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wahl PM, Gagne JJ, Wasser TE et al. . Early steps in the development of a claims-based targeted healthcare safety monitoring system and application to three empirical examples. Drug Saf 2012;35:407–16. 10.2165/11594770-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shakibaei M, Stahlmann R. Ultrastructure of Achilles tendon from rats after treatment with fleroxacin. Arch Toxicol 2001;75:97–102. 10.1007/s002040000203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sendzik J, Shakibaei M, Schafer-Korting M et al. . Synergistic effects of dexamethasone and quinolones on human-derived tendon cells. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010;35:366–74. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Chen CP et al. . Ciprofloxacin up-regulates tendon cells to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 with degradation of type I collagen. J Orthop Res 2011;29:67–73. 10.1002/jor.21196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etminan M, Forooghian F, Brophy JM et al. . Oral fluoroquinolones and the risk of retinal detachment. JAMA 2012;307:1414–19. 10.1001/jama.2012.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasternak B, Svanstrom H, Melbye M et al. . Association between oral fluoroquinolone use and retinal detachment. JAMA 2013;310:2184–90. 10.1001/jama.2013.280500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berillis P. The role of collagen in the aorta's structure. Open Circulation Vascular J 2013;6:1–8. 10.2174/1877382601306010001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Figueiredo BL, Jaldin RG, Dias RR et al. . Collagen is reduced and disrupted in human aneurysms and dissections of ascending aorta. Hum Pathol 2008;39:437–43. 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy AR, O'Brien BJ, Sellors C et al. . Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2003;10:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS et al. . Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. N Engl J Med 2004;351:543–51. 10.1056/NEJMoa040135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daneman N, Gruneir A, Bronskill SE et al. . Prolonged antibiotic treatment in long-term care: role of the prescriber. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:673–82. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park-Wyllie LY, Juurlink DN, Kopp A et al. . Outpatient gatifloxacin therapy and dysglycemia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1352–61. 10.1056/NEJMoa055191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khaliq Y, Zhanel GG. Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy: a critical review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36: 1404–10. 10.1086/375078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McPhee JT, Hill JS, Eslami MH. The impact of gender on presentation, therapy, and mortality of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the United States, 2001–2004. J Vasc Surg 2007;45:891–9. 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clouse WD, Hallett JW Jr, Schaff HV et al. . Acute aortic dissection: population-based incidence compared with degenerative aortic aneurysm rupture. Mayo Clin Proc 2004;79:176–80. 10.4065/79.2.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canadian Health Information Management Association. Reabstraction Study of the Ontario Case Costing Facilities: For Fiscal Years 2002/2003 and 2003/2004 2005.

- 22.NACRS CIHI Data Quality Study of Ontario Emergency Department Visits for 2004–2005—Executive Summary. Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2007.

- 23.Redelmeier DA, Thiruchelvam D, Daneman N. Introducing a methodology for estimating duration of surgery in health services research. J Clin Epidemiol 2008. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thiebaut AC, Benichou J. Choice of time-scale in Cox's model analysis of epidemiologic cohort data: a simulation study. Stat Med 2004;23:3803–20. 10.1002/sim.2098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using SAS a Practical Guide 2015.

- 26.van der Linden PD, Sturkenboom MC, Herings RM et al. . Fluoroquinolones and risk of Achilles tendon disorders: case-control study. BMJ 2002;324:1306–7. 10.1136/bmj.324.7349.1306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Linden PD, Sturkenboom MC, Herings RM et al. . Increased risk of Achilles tendon rupture with quinolone antibacterial use, especially in elderly patients taking oral corticosteroids. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1801–7. 10.1001/archinte.163.15.1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ponsioen TL, van der Worp RJ, van Luyn MJ et al. . Packages of vitreous collagen (type II) in the human retina: an indication of postnatal collagen turnover? Exp Eye Res 2005;80:643–50. 10.1016/j.exer.2004.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran-Viet KN, Soler V, Quiette V et al. . Mutation in collagen II alpha 1 isoforms delineates Stickler and Wagner syndrome phenotypes. Mol Vis 2013;19:759–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austin PC, Daly PA, Tu JV. A multicenter study of the coding accuracy of hospital discharge administrative data for patients admitted to cardiac care units in Ontario. Am Heart J 2002;144:290–6. 10.1067/mhj.2002.123839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hecker MT, Aron DC, Patel NP et al. . Unnecessary use of antimicrobials in hospitalized patients: current patterns of misuse with an emphasis on the antianaerobic spectrum of activity. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:972–8. 10.1001/archinte.163.8.972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]