Abstract

Objectives

To examine whether the strengths of the associations between chronic diseases and overall choking differ from those of the associations between chronic diseases and only food-related choking.

Design

This cross-sectional study used nationwide multiple cause mortality files.

Setting

The USA.

Participants

Older adults aged 65 years or more died between 2009 and 2013.

Main outcome measures

Mortality ratio (observed/expected) of number of deaths from both causes (chronic diseases and choking) and 95% CIs.

Results

We identified 76543 deaths for which the death certificates report choking (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes W78, W79 and W80 combined) as a cause of death and only 4974 (6.5%) deaths were classified as food-related choking (ICD-10 code W79). Schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease and oral cancer are four chronic diseases that had significant associations with both overall and food-related choking. Stroke, larynx cancer and mood (affective) disorders had significant associations with overall choking, but not with food-related choking.

Conclusions

We suggest using overall choking instead of only food-related choking to better describe the associations between chronic diseases and choking.

Keywords: ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, GERIATRIC MEDICINE, THORACIC MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The present study used the nationwide population-based data set.

The study examined more chronic diseases than previous studies.

Both chronic diseases and choking might be under-reported on the death certificates by the coroners or medical examiners.

Introduction

Many older adults with chronic diseases experience dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing) and have a higher risk of choking deaths.1–3 By using multiple cause mortality files, one US study determined that older adults whose death certificates report chronic diseases (such as Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease) exhibited a higher risk of having food-related choking as a cause of death.4 However, inconsistent with the current knowledge that suggests that dysphagia is a common problem among people with stroke,5–7 no significant association between stroke and food-related choking was noted in that study. One possible explanation, as indicated by the authors, is that the deaths of many older adults involving food-related choking were misclassified as obstruction of the respiratory tract by an unspecified object.

Regarding the proper classification of national cause of death statistics, the three categories related to choking listed in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) are as follows: ICD-10 code W78 ‘Inhalation of gastric contents’, ICD-10 code W79 ‘Inhalation and ingestion of food causing obstruction of respiratory tract’ and ICD-10 code W80 ‘Inhalation and ingestion of other objects causing obstruction of respiratory tract’.8 It is highly likely that many food-related choking deaths were misclassified as ICD-10 code W80 instead of ICD-10 code W79. The problem of misclassification would bias the estimation of the associations between chronic diseases and choking deaths. Thus, we examined whether the strengths of the associations between chronic diseases and overall choking (ICD-10 codes W78, W79 and W80 combined) might differ from those of the association between chronic diseases and only food-related choking (ICD-10 code W79). Furthermore, we added more chronic diseases than those listed in the study of Kramarow et al,4 because one systematic review indicated that patients with some psychiatric disorders have a higher risk of choking deaths.9

Data and methods

The number of deaths among older adults in the USA aged 65 years or older for whom various types of chronic diseases and choking are listed on the death certificates from 2009 to 2013 were obtained from the Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC WONDER).10

To examine the magnitude of the association between particular chronic disease and choking, we used the ratio method proposed by Israel et al.11 This method consists of calculating the ratio of the number of observed pairs (O) of causes to the expected number (E) of pairs of causes based on the assumption of independence. An O/E ratio >1 indicates that more deaths with paired causes were reported than could be expected by chance if the paired causes were independent. This method has been used by many scholars.4 12–15

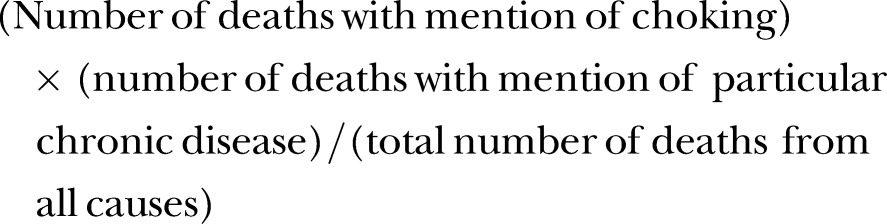

The expected number of deaths is calculated as:

|

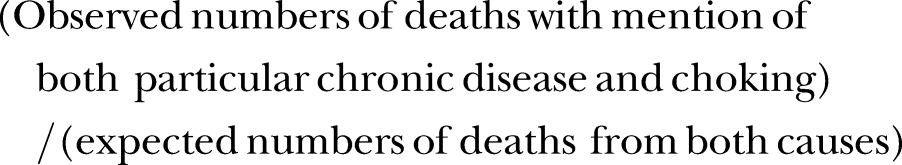

The ratio is calculated as:

|

We also estimated 95% CIs of the O/E ratio according to the Poisson distribution.

Results

For 76543 older adults in the USA aged 65 years or more who died between 2009 and 2013, choking was reported as a cause of death (ie, died with) on the death certificates, and choking was assigned as the underlying cause of death (ie, died from) in only one-fifth (21.6%) of the death certificates (table 1). Furthermore, only 6.5% (4974) of overall choking occurrences (ICD-10 codes W78, W79 and W80 combined) were classified as food-related choking (ICD-10 codes W79).

Table 1.

Number of deaths for which choking was assigned as either the underlying COD or mentioned among older adults aged 65 years or more in the USA according to CDC WONDER for the years 2009–2013

| Category of choking (ICD-10 codes) | Underlying COD |

Mentioned |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Per cent | N | Per cent | |

| Overall choking (W78–W80) | 16531 | 100.0 | 76543 | 100.0 |

| Inhalation of gastric contents (W78) | 804 | 4.9 | 2617 | 3.4 |

| Inhalation and ingestion of food causing obstruction of respiratory tract (W79) | 3113 | 18.8 | 4974 | 6.5 |

| Inhalation and ingestion of other objects causing obstruction of respiratory tract (W80) | 12614 | 76.3 | 68980 | 90.1 |

COD, cause of death; CDC WONDER, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision.

As shown in table 2, the percentage of death certificates reporting both chronic diseases and overall choking as causes of death was the highest for patients with schizophrenia (2.66%), followed by Parkinson's disease (2.25%), larynx cancer (1.75%) and Alzheimer's disease (1.44%). However, the percentage of death certificates reporting both chronic diseases and food-related choking as causes of death was the highest for patients with schizophrenia (0.52%), followed by Parkinson's disease (0.15%), oral cancer (0.09%), larynx cancer (0.08%), mood (affective) disorders (0.07%) and Alzheimer's disease (0.07%).

Table 2.

Number and percentage of deaths where choking was mentioned* among the deaths aged 65 years or more where the particular chronic disease was mentioned in the USA according to CDC WONDER from 2009 to 2013

| Chronic disease (ICD-10 codes) | Particular chronic disease was mentioned | Particular chronic disease and overall choking were both mentioned | Per cent | Particular chronic disease and food- related choking were both mentioned | Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral cancer (C00–C14) | 30469 | 412 | 1.35 | 27 | 0.09 |

| Oesophageal cancer (C15) | 49860 | 391 | 0.78 | 6 | 0.01 |

| Larynx cancer (C32) | 15391 | 270 | 1.75 | 12 | 0.08 |

| Diabetes mellitus (E10–E14) | 901854 | 6329 | 0.70 | 430 | 0.05 |

| Schizophrenia (F20–F29) | 13697 | 365 | 2.66 | 71 | 0.52 |

| Mood (affective) disorders (F30–F39) | 55508 | 644 | 1.16 | 37 | 0.07 |

| Parkinson’s disease (G20–G21) | 178482 | 4024 | 2.25 | 273 | 0.15 |

| Alzheimer’s disease (G30, F03) | 1502141 | 21692 | 1.44 | 1026 | 0.07 |

| Heart disease (I00–I09, I11, I13, I20–I51) | 4441643 | 27398 | 0.62 | 1710 | 0.04 |

| Stroke (I60–I69) | 925559 | 12210 | 1.32 | 487 | 0.05 |

| Chronic lower respiratory disease (J40–J47) | 1157788 | 8360 | 0.72 | 271 | 0.02 |

| Nephrotic disease (N00–N07, N17–N19, N25–N27) | 940209 | 6009 | 0.64 | 122 | 0.01 |

*‘Mention’ can be as either an underlying or a contributory cause of death.

CDC WONDER, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision.

Seven chronic diseases were significantly associated with overall choking, with significance ratios being higher than 1; however, only four chronic diseases had significant associations with food-related choking (table 3). Chronic diseases associated with overall choking at a ratio >1 were ranked in the following order: schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease, larynx cancer, Alzheimer's disease, oral cancer, stroke and mood (affective) disorders. By contrast, chronic diseases associated with food-related choking were ranked in the following order: schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease, oral cancer, larynx cancer, Alzheimer's disease and mood (affective) disorders.

Table 3.

Number of observed deaths, expected deaths and the observed/expected ratio of deaths where particular chronic disease and choking were both mentioned* among the deaths aged 65 years or more where the particular chronic disease was mentioned in the USA according to CDC WONDER from 2009 to 2013

| Chronic disease | Overall choking |

Food-related choking |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Observed/expected | (95% CI) | Observed | Expected | Observed/expected | (95% CI) | |

| Schizophrenia | 365 | 115 | 3.19 | (2.87 to 3.53) | 71 | 7 | 9.54 | (7.92 to 12.8) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 4024 | 1492 | 2.70 | (2.61 to 2.78) | 273 | 97 | 2.82 | (2.49 to 3.17) |

| Larynx cancer | 270 | 129 | 2.10 | (1.86 to 2.36) | 12 | 8 | 1.44 | (0.74 to 2.51) |

| Alzheimer’s disease* | 21692 | 12559 | 1.73 | (1.70 to 1.75) | 1026 | 816 | 1.26 | (1.18 to 1.34) |

| Oral cancer | 412 | 255 | 1.62 | (1.46 to 1.78) | 27 | 17 | 1.63 | (1.07 to 2.38) |

| Stroke | 12210 | 7739 | 1.58 | (1.55 to 1.61) | 487 | 503 | 0.97 | (0.88 to 1.06) |

| Mood (affective) disorders | 644 | 464 | 1.39 | (1.28 to 1.50) | 37 | 30 | 1.23 | (0.87 to 1.70) |

| Oeophageal cancer | 391 | 417 | 0.94 | (0.85 to 1.04) | 6 | 27 | 0.22 | (0.08 to 0.49) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6329 | 7540 | 0.84 | (0.82 to 0.86) | 430 | 490 | 0.88 | (0.80 to 0.96) |

| Chronic lower respiratory disease | 8360 | 9680 | 0.86 | (0.85 to 0.88) | 271 | 629 | 0.43 | (0.38 to 0.49) |

| Nephrotic disease | 6009 | 7861 | 0.76 | (0.75 to 0.78) | 122 | 511 | 0.24 | (0.20 to 0.29) |

| Heart disease | 27398 | 37137 | 0.74 | (0.73 to 0.75) | 1710 | 2413 | 0.71 | (0.68 to 0.74) |

*‘Mention’ can be as either an underlying or a contributory cause of death.

CDC WONDER, Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that only 6.5% of all deaths with mention of any type of choking were classified as food-related choking and 9 of 10 overall choking occurrences were classified as obstruction of the respiratory tract by an unspecified object. We also found that the strengths of the associations between chronic diseases and overall choking differed from those of the associations between chronic diseases and only food-related choking. Schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease and oral cancer are four chronic diseases that had significant associations with both overall and food-related choking. However, stroke, larynx cancer and mood (affective) disorders had significant associations with overall choking and not with food-related choking.

Some forensic studies, suggested that majority of unintentional choking deaths among older adults were food related and only a few choking deaths were due to foreign bodies other than food, such as broken teeth or dentures.16–20 We did not have autopsy data to determine the proportion of choking deaths been classified as ICD-10 code W80. However, according to previous forensic studies,16–20 many of deaths been classified as ICD-10 code W80 were in actually involving food. Furthermore, the misclassification would vary by characteristics of the deceased and certifiers. These misclassifications would certainly bias the estimation of the strengths of the associations between chronic diseases and choking, as indicated in this study. Reports of choking as a cause of death among older adults with stroke, larynx cancer and mood (affective) disorders could be overlooked if only food-related choking is considered in assessments.

In the study of Kramarow et al,4 only two chronic diseases (Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease) had significant associations with food-related choking. We did not include pneumonitis (aspiration pneumonia) and influenza and pneumonia in this study because these two diagnoses are acute conditions. We identified five more chronic diseases with significant associations with overall choking. Two of them were psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia and mood (affective) disorders), two were cancers (oral cancer and larynx cancer) and one was stroke, which is consistent with current knowledge. The caretakers of older adults with chronic diseases and a higher risk of death from choking should pay close attention to food preparation and carefully monitor patients during mealtimes.16 However, we should not concern only the relative associations but also the absolute number of deaths, as number of deaths with mention Alzheimer's disease were 100 times more than the number of deaths with mention schizophrenia, in which the public health implications are quite different.

Despite using broader definitions for choking to include more cases in examining the associations between chronic diseases and choking, this study had some limitations. First, our analysis depended only on the information reported on the death certificates, and both chronic diseases and choking might have been under-reported by medical certifiers. Many sudden and unexpected deaths occurring during meals because of accidental occlusion of the airway by swallowed food might have been incorrectly attributed to acute myocardial infarction (ie, café coronary), resulting in the under-reporting of choking deaths.17 A choking death is an unnatural death and should be certified by medical examiners or coroners. Different medical examiners or coroners might have different opinions and habits in reporting chronic diseases as the contributory causes of death. We assume that the under-reporting of both choking and chronic diseases is non-differential misclassification.

Second, detailed information relevant to injury prevention programme design, such as the types of foods, mealtimes and places of injury, was not specifically recorded in the death certificates in most cases. Furthermore, we did not have information of the level of dependence on particular chronic disease. The dead with very dependent especially in degenerative diseases with a high prevalence of dysphagia is difficult to attribute death by choking food. It is not surprising that the choking is more common in patients with psychiatric illness (schizophrenia) or Parkinson’s disease with low functional dependence.

In conclusion, only a few food-related choking occurrences were correctly classified as ICD-10 code W79, whereas most of the cases were classified as ICD-10 code W80. Consequently, to effectively assess the strengths of the associations between chronic diseases and choking, it is appropriate to use overall choking (ie, combining ICD-10 codes W78, W79 and W80) instead of only food-related choking. Moreover, the caretakers of older adults with chronic diseases (schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease, larynx cancer, Alzheimer's disease, oral cancer, stroke and mood (affective) disorders) should be alert in preventing choking.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Bai-Huan Lin for her efforts in data analyses.

Footnotes

Contributors: T-HL conceived the study, guided the analyses, wrote the article draft and is the guarantor. W-SW, T-JC and K-CS helped conduct the literature review, analysed the data, interpreted the results and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: This study was partially funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (NSC102-2314-B-006-054) and partially funded by the Chi Mei and National Cheng Kung University Joint Program (CMNCKU10410).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at National Cheng Kung University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Forster A, Samaras N, Gold G et al. . Oropharyngeal dysphagia in older adults: a review. Eur Geriatr Med 2011;2:356–62. 10.1016/j.eurger.2011.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller N, Patterson J. Dysphagia: implications for older people. Rev Clin Gerontol 2014;24:41–57. 10.1017/S095925981300021X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clavé P, Shaker R. Dysphagia: current reality and scope of the problem. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:259–70. 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramarow E, Warner M, Chen LH. Food-related choking deaths among the elderly. Inj Prev 2014;20:200–3. 10.1136/injuryprev-2013-040795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altman KW, Richards A, Goldberg L et al. . Dysphagia in stroke, neurodegenerative disease, and advanced dementia. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 2013;46:1137–49. 10.1016/j.otc.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang CY, Cheng TJ, Lin CY et al. . Reporting of aspiration pneumonia or choking as a cause of death in patients who died with stroke. Stroke 2013;44:1182–5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walshe M. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in neurodegenerative disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res 2014;3:1265–71. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2015/en (accessed 20 Jun 2015).

- 9.Aldridge KJ, Taylor NF. Dysphagia is a common and serious problem for adults with mental illness: a systematic review. Dysphagia 2012;27:124–37. 10.1007/s00455-011-9378-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER. http://wonder.cdc.gov (accessed 20 Jun 2015).

- 11.Israel RA, Rosenberg HM, Curtin LM. Analytical potential for multiple cause-of-death data. Am J Epidemiol 1986;124:161–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coste J, Jougla E. Mortality from rheumatoid arthritis in France, 1970–1990. Int J Epidemiol 1994;23:545–52. 10.1093/ije/23.3.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziade N, Jourgla E, Coste J. Population-level influence of rheumatoid arthritis on mortality and recent trends: a multiple cause-of-death analysis in France, 1970–2002. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1950–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ascoli V, Minelli G, Kanieff M et al. . Cause-specific mortality in classic Kaposi's sarcoma: a population-based study in Italy (1995–2002). Br J Cancer 2009;101:1085–90. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Souza DC, Santo AH, Sato EI. Mortality profile related to systematic lupus erythematosus: a multiple cause-of-death analysis. J Rheumatol 2012;39:496–503. 10.3899/jrheum.110241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berzlanovich AM, Fazeny-Dörner B, Waldhoer T et al. . Foreign body asphyxia: a preventable cause of death in the elderly. Am J Prev Med 2005;28:65–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wick R, Gilbert JD, Byard RW. Café coronary syndrome-fatal choking on food: an autopsy approach. J Clin Forensic Med 2006;13:135–8. 10.1016/j.jcfm.2005.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolkas L, Stanley C, Smith AM et al. . Deaths associated with choking in San Diego County. J Forensic Sci 2007;52:176–9. 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00297.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boghossian E, Tambuscio S, Sauvageau A. Nonchemical suffocation deaths in forensic setting: a 6-year retrospective study of environmental suffocation, smothering, choking, and traumatic/positional asphyxia. J Forensic Sci 2010;55:646–51. 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2010.01351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kikutani T, Tamura F, Tohara T et al. . Tooth loss as risk factor for foreign-body asphyxiation in nursing-home patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012;54:e431–5. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]