Abstract

Introduction

Acute calculous cholecystitis represents one of the most common complications of cholelithiasis. While laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the standard treatment in mild and moderate forms, the need for antibiotic therapy after surgery remains undefined. The aim of the randomised controlled Cholecystectomy Antibiotic Randomised Trial (CHART) is therefore to assess if there are benefits in the use of postoperative antibiotics in patients with mild or moderate acute cholecystitis in whom a laparoscopic cholecystectomy is performed.

Methods and analysis

A single-centre, double-blind, randomised trial. After screening for eligibility and informed consent, 300 patients admitted for acute calculus cholecystitis will be randomised into two groups of treatment, either receiving amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or placebo for 5 consecutive days. Postoperative evaluation will take place during the first 30 days. Postoperative infectious complications are the primary end point. Secondary end points are length of hospital stay, readmissions, need of reintervention (percutaneous or surgical reinterventions) and overall mortality. The results of this trial will provide strong evidence to either support or abandon the use of antibiotics after surgery, impacting directly in the incidence of adverse events associated with the use of antibiotics, the emergence of bacterial resistance and treatment costs.

Ethics and dissemination

This study and informed consent sheets have been approved by the Research Projects Evaluating Committee (CEPI) of Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (protocol N° 2111).

Results

The results of the trial will be reported in a peer-reviewed publication.

Trial registration number

Keywords: INFECTIOUS DISEASES, laparoscopy, cholecystitis, postoperative, antibiotics

Introduction

More than 90% of the cases of acute calculus cholecystitis (ACC) are associated with gallstones.1 2 ACC represents one of the most common complications of cholelithiasis, which can be found in 20% of symptomatic patients. It is known that the initial event in ACC is the obstruction of the gallbladder's drainage due to an impacted gallstone in the Hartmann's pouch or the cystic duct. Intraluminal pressure increases, reducing blood irrigation and lymphatic drainage, which finally produces gallbladder inflammation. It is assumed that this inflammation is initially sterile. However, if the obstruction persists, infection can develop, commonly with bacteria of the family of Enterobacteriacea, Enteroccocus spp and anaerobes.2–4

The diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis have been well established in the 2007 Tokyo Guidelines, updated in 2013. According to these guidelines, ACC is classified as mild (grade I), moderate (grade II) and severe (grade III). Severe acute cholecystitis is associated with at least one organ dysfunction. Moderate acute cholecystitis is associated with any of the following conditions: elevated white cell count (WCC) (18 000/mm3); palpable tender mass in the right upper abdominal quadrant; duration of symptoms for more than 72 h; marked local inflammation (gangrenous cholecystitis, pericholecystic abscess, hepatic abscess, biliary peritonitis, emphysematous cholecystitis). Mild acute cholecystitis does not meet the criteria of any of the former conditions. It can also be defined as an acute cholecystitis in a healthy patient with no organ dysfunction with only mild inflammatory changes in the gallbladder.5

While laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the gold standard treatment of mild and moderate forms of ACC, the need for antibiotic therapy after surgery continues to be a matter of debate. There is a lack of evidence regarding duration and type of antimicrobial therapy after surgery.2–6 The updated Tokyo Guidelines propose to administer antibiotics only up to 24 h after surgery for mild ACC and 4–7 days in moderate or severe cases.4 It has been suggested that a β-lactam monoscheme (ie, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC)) would be adequate in patients with mild and moderate cholecystitis without intraoperative complications such as bile peritonitis, cholangitis, gallbladder perforation or abscesses.4–7 However, the real benefits of its use in these situations have not been well studied. Antibiotics are associated with common adverse effects such as allergic reactions and digestive intolerance (nausea, vomits and diarrhoea). Nowadays, there is a clear tendency towards the rational use of antibiotics in order to prevent bacterial resistance. Amoxicillin has been associated with a 7–8% incidence of toxicodermia, 1% of allergy reactions and a very low incidence of anaphylactic shock (0.01–0.04% with the use of penicillin).8 Hence, we decided to conduct a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in patients undergoing LC for mild and moderate ACC, randomising patients to receive AMC or placebo after surgery. The primary objective of the present trial is to assess whether antibiotic treatment after LC in mild or moderate ACC reduces the incidence of postoperative infectious complications. The hypothesis is that postoperative antibiotics have no positive impact on patient's outcome and therefore should not be indicated in this subset of patients.

Methods and analysis

Trial design, setting and randomisation

The Cholecystectomy Antibiotic Randomised Trial (CHART) is a randomised, controlled and blind to patient, investigator and data analysts study, which compares antibiotic treatment after LC due to mild and moderate ACC versus no antibiotic treatment. From February 2014, surgeons initiated this study (protocol V.1.0) at Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (HIBA). This is a teaching hospital affiliated to the University of Buenos Aires Medical School and the HIBA University Medical School.

All patients admitted with acute calculous cholecystitis will receive parenteral hydration, gastric protection with proton pump inhibitors, analgesics and intravenous treatment with AMC. This treatment is continued until the operation. Surgery will be performed within the first 5 days after admission. Those patients who worsen during the waiting time will be explored as soon as possible. Potential complications (such as bile peritonitis, cholangitis, gallbladder perforation or abscesses) or evidence of greater severity of cholecystitis may occur and this can only be diagnosed during surgery. These patients will not be eligible for randomisation and will be dismissed from the statistical analysis. Nevertheless, this group will be considered in the final flow chart.

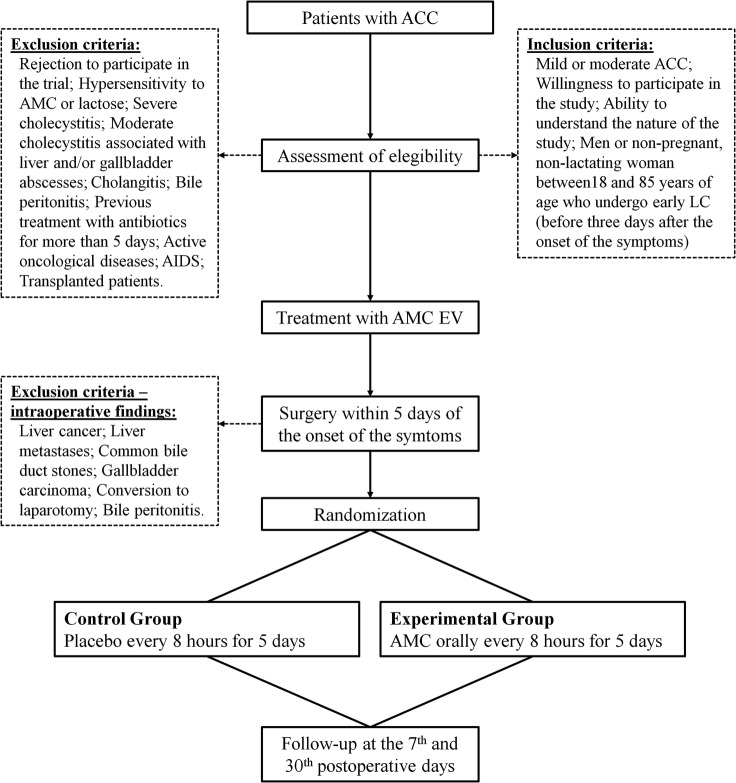

After screening for eligibility and informed consent is obtained, patients will be randomised in a 1:1 ratio into one of the following study groups (figure 1):

Antibiotic treatment

Placebo

Figure 1.

Trial design chart (ACC, acute calculous cholecystitis; AMC, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; EV, endovenous; LC, laparoscopic cholecystectomy).

In summary, patients are recruited prior to surgery but are randomised only after surgery, once the investigators confirm that no exclusion criteria are present intraoperatively.

Patients will be randomised using the online randomiser provided by the Hospital Italiano Statistics Department (http://protocolos.hospitalitaliano.org.ar). This randomiser provides a list with a sequence of numbers from 1 to 300, each one randomly assigned to one of the study groups. Patients will be assigned to each number in order according to the moment they enter the protocol. Neither the researchers nor the patients will have knowledge of the assigned treatment until the end of the study. Each Treatment Pack (TP) will have a code to retrospectively help identify which group of treatment modalities the patient was assigned to. Each TP contains capsules for a 5-day treatment to be administered three times per day. The capsules will be provided by the HIBA Central Pharmacy according to the randomisation list. The antibiotic and placebo capsules will be packaged and labelled identically. These capsules will be made of insipid gelatine material and will have the same colour.

Trial organisation

Trial population and patient recruitment

All consecutive patients with the new diagnosis of mild or moderate ACC according to the Revised Tokyo Guidelines5 admitted to the HIBA will be screened for eligibility to be enrolled in the CHART.

Patients will be approached for randomised inclusion if they meet each of the following inclusion criteria: diagnosis of mild or moderate ACC; willingness to participate in the study; ability to understand the nature of the study and what will be required of them; men and non-pregnant, non-lactating women between 18 and 85 years of age who undergo early LC (before 3 days after the onset of the symptoms).

Exclusion criteria are rejection to participate in the trial or the process of informed consent; hypersensitivity to AMC or lactose (used in placebo); severe ACC; moderate ACC associated with liver and/or gallbladder abscesses, cholangitis or bile peritonitis; intraoperative findings such as liver cancer, liver metastases, common bile duct stones or gallbladder carcinoma; conversion to laparotomy; previous treatment with antibiotics for more than 5 days; active oncological diseases; AIDS transplanted patients.

Trial interventions

All patients admitted to HIBA from February 2014 with mild or moderate ACC were invited to participate in the study. Surgeons from the hepatobliopancreatic section of the HIBA will recruit participants. Patients will receive parenteral hydration, gastric protection with proton pump inhibitors, analgesics and treatment with 1000 mg of AMC intravenously every 8 h until surgery, which has to be performed within 5 days after admission. No extra dose of AMC will be administered during surgery.

If there are no intraoperative criteria for exclusion, patients will be randomly assigned to either group of intervention:

Experimental group: antibiotic treatment after surgery:

Patients in the experimental group will receive 1000 mg of AMC orally every 8 h for 5 days, immediately after the surgery.

Control group—placebo treatment after surgery:

Patients in the control group will receive placebo orally every 8 h for 5 days, immediately after the surgery.

Study objectives and end points

The primary objective of the present trial is to assess whether antibiotic treatment after LC in mild or moderate ACC reduces the incidence of postoperative infectious complications.

Primary end point

The primary efficacy end point is postoperative infectious complications, defined as any infection occurring within the first 30 postoperative days, classified according to the Clavien-Dindo Classification.9 After randomisation, patients will be followed up for 30 days.

Secondary end points

Length of hospital stay: number of days from admission to hospital discharge.

Readmission: need of readmission due to postoperative complications that require hospital care (hydration, intravenous antibiotics, percutaneous drainage, surgical treatment).

Reintervention: need of surgical treatment under general anaesthesia or percutaneous procedure in complicated patients.

Overall mortality: deaths occurring during the first postoperative month.

Trial implementation

Inclusion, evaluation and follow-up

Patients will be screened according to the eligibility criteria and asked for written informed consent. Afterwards, they will be allocated randomly to each of both study groups.

Study schedule

The evaluation schedule for all patients will be as follows:

Stage 1: Every patient included in the protocol will be registered in a sheet containing personal information and data on the primary and secondary end points.

TP will be administered during the five postoperative days. Each patient will receive a medicament control sheet where they will register every dose. On days 7 and 30, patients will be monitored in the outpatient's office. Patients will be given contact telephone numbers in case they have any concern or need to report any event during follow-up. All data collected will be registered in the follow-up sheet.

Stage 2: During this stage, researchers will carry out a statistical analysis of the analysed variables and their relations.

Sample size

We hypothesised that the absence of postoperative antibiotic treatment would not be inferior to receiving antibiotics after surgery for the development of surgical site and distant infections after cholecystectomy. Our sample size calculation was based on published data10–13 and on an expected postoperative infection rate in the antibiotic group of 3%. Assuming a non-inferiority margin of 5%, a one-tailed α error of 5% and a power of 80% to reject this null hypothesis, we estimated that the required sample size would be 150 cases in each group.

Monitoring

All data will be registered in follow-up sheets by the investigators. These sheets will be exported weekly to Microsoft Access (V.2013, Microsoft Corporation). The Research Projects Evaluating Committee (CEPI) of HIBA will audit this trial every 6 months. An interim analysis will be performed once 150 patients are recruited.

Statistical analysis

Confirmatory analysis

A non-inferiority design was chosen. The results will be analysed on an intention-to-treat basis. The association between outcome and the assigned treatment will be evaluated using the χ2 TEST in discrete variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. All data analysis will be performed using the SPSS software package V.17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Clinical management and abandonment

Patients included are warned not to take medications from other doctors outside the study. In case a patient requires antibiotics for some reason, the blind will be revealed to ensure the proper treatment for this patient. This event will be registered and the patient will be considered in the statistical analysis.

Each patient is informed to be free to abandon the treatment at any time by informing the researchers. If the medical team or researchers consider that the patient is at risk due to the study, the patient will be removed and the doctors will provide feedback to the patient.

Damage and complications

If the patient presents any infectious complication during the postoperative stage or any sign of persistent infection such as leukocytosis (defined as a WCC of 10 000/mm3 or more), fever over 38°C (100.4°F), hepatogram alterations, cholangitis or hepatic abscesses, the medical team will proceed to stop the administration of TP and decide which medical actions need to be taken according to each particular case. Any adverse event detected during outpatient monitoring will be registered and classified according to its severity into mild, moderate and severe.

Mild: Transitory events that do not require special treatment. These events do not affect a patient's daily life.

Moderate: Events that interfere in the patient's daily routine that require minimal, local or non-invasive intervention.

Severe: Medically significant, disabling or immediately life-threatening events that require hospitalisation and/or urgent intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval

The CHART is conducted in line with the current national and international regulations: World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki, Regulation 5330/07 ANMAT, the Standards of Good Practices ICH E6 and the laws and regulations of the country, providing the greatest protection to the patient. The CHART has been registered at Clinicaltrial.gov database (ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier: NCT02057679).

Informed consent and confidentiality

In all cases, the participation in the study is voluntary and certified by the process of informed consent. The right to refuse to participate in the study will be respected at all times without any implications in the treatment of the patient disease. The antibiotics proposed correspond to the empirical initial scheme that is in use in our institution for patients with inflammatory/infectious hepatobiliary affections acquired in the community. All data collected will be treated with confidentiality and anonymously. Authorised personnel can only access the records of the study in compliance with the current legal regulation: National Law of Personal Information Protection No. 25.326 (Habeas Data Law).

All patients will be informed of the aims of the study, the possible adverse events, the procedures and possible hazards to which they will be exposed, and the mechanism of treatment allocation. Furthermore, it is the responsibility of the investigator to explain to the patients their duties within the trial. They will be informed about the strict confidentiality of their personal data, but that their medical records may be reviewed for trial purposes by authorised individuals other than their treating physician. Trial findings will be stored in accordance with local data protection law/ICH GCP-Guidelines and will be handled in the strictest confidence. For protection of these data, organisational procedures are implemented to prevent distribution of data to unauthorised people.

Dissemination

Anonymised results of the study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal, and will be presented at academic meetings and scientific conferences. Only the registered investigators will have access to the individual patient data.

Discussion

Although ACC is one of the most common diseases in general surgery, few trials have assessed the role of antibiotic therapy after LC. Most publications on the subject analyse the use of antibiotics after conventional procedures, or mix in the same design open and laparoscopic procedures.

In the late 1980s, Lau et al randomised 203 patients and compared a short course of two doses versus a long course of 7 days of cefamandole after early open cholecystectomy. They found that the short course was as effective as the long one in reducing postoperative infectious complications with the additional advantages of lower costs, risks of adverse events and length of hospital stay.14 This was the first study to suggest that a reduction in the use of postoperative antibiotics may be possible. However, this study is outdated given the many changes in bacterial resistance over time and the modern surgical therapies. In addition to these findings, Mazeh et al3 conducted a RCT in which they demonstrated that the addition of intravenous antibiotic treatment to supportive care has limited, if any, effect in patients with mild ACC.

Recently, Regimbeau et al15 published a multicentre RCT in which patients admitted with mild and moderate ACC were randomised to antibiotics or no treatment after surgery. In the author's opinion, the main limitation of this study is that it includes both conventional and laparoscopic approaches (15% open cholecystectomies and a 10% conversion rate). It has been widely demonstrated that one of the advantages of the laparoscopic approach is that it is associated with the less surgical side infections rate.16 Thus, both approaches should be studied separately. Another limitation of this study is that it does not include a placebo group, which may lead placebo effect bias.

The trial proposed here is an original study in which, for the first time, antibiotics are compared with placebo after LC in cases of ACC. The CHART is a double-blind RCT designed to evaluate the need for and safety of antibiotic treatment after LC for mild or moderate ACC. The results of this trial will provide strong evidence for decision-making in this matter. This could avoid the unnecessary use of antibiotics after surgery, decreasing the incidence of associated adverse events, as well as the emergence of bacterial resistance and treatment costs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Central Pharmacy staff of the HIBA. The CHART is funded exclusively by the institutional/departmental sources.

Footnotes

Contributors: The concept of the study was derived from MdS. This study was designed by PP, JGo, AD and MdS. The article was written by PP, JPC and MdS. DG performed the sample size calculation and planned the statistical analyses. PP, AD, JGo, JGl, JPC, DG, LB, OM, FA, RSC, MP, GA,VA, EdS, RSC, JP and MdS were involved in trial implementation and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Research Projects Evaluating Committee (CEPI) of Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (protocol N° 2111).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Yusoff IF, Barkun JS, Barkun AN. Diagnosis and management of cholecystitis and cholangitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2003;32:1145–68. 10.1016/S0889-8553(03)00090-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strasberg SM. Clinical practice. Acute calculous cholecystitis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2804–11. 10.1056/NEJMcp0800929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazeh H, Mizrahi I, Dior U et al. . Role of antibiotic therapy in mild acute calculus cholecystitis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. World J Surg 2012;36:1750–9. 10.1007/s00268-012-1572-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida M, Takada T, Kawarada Y et al. . Antimicrobial therapy for acute cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007;14:83–90. 10.1007/s00534-006-1160-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokoe M, Takada T, Strasberg SM et al. . TG13 diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013;20:35–46. 10.1007/s00534-012-0568-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanafani ZA, Khalifé N, Kanj SS et al. . Antibiotic use in acute cholecystitis: practice patterns in the absence of evidence-based guidelines. J Infect 2005;51:128–34. 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuks D, Cossé C, Régimbeau JM. Antibiotic therapy in acute calculous cholecystitis. J Visc Surg 2013;150:3–8. . 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johannes CB, Ziyadeh N, Seeger JD et al. . Incidence of allergic reactions associated with antibacterial use in a large, managed care organisation. Drug Saf 2007;30:705–13. 10.2165/00002018-200730080-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML et al. . The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009;250:187–96. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yildiz B, Abbasoglu O, Tirnaksiz B et al. . Determinants of postoperative infection after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 2009;56:589–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agabiti N, Stafoggia M, Davoli M et al. . Thirty-day complications after laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy: a population-based cohort study in Italy. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii: e001943 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jatzko GR, Lisborg PH, Pertl AM et al. . Multivariate comparison of complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy and open cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 1995;221:381–6. 10.1097/00000658-199504000-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lujan JA, Parrilla P, Robles R et al. . Laparoscopic cholecystectomy vs open cholecystectomy in the treatment of acute cholecystitis: a prospective study. Arch Surg 1998; 133:173–5. 10.1001/archsurg.133.2.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau WY, Yuen WK, Chu KW et al. . Systemic antibiotic regimens for acute cholecystitis treated by early cholecystectomy. Aust N Z J Surg 1990;60:539–43. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1990.tb07422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regimbeau JM, Fuks D, Pautrat K et al. . Effect of postoperative antibiotic administration on postoperative infection following cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:145–54. 10.1001/jama.2014.7586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coccolini F, Catena F, Pisano M et al. . Open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2015;18:196–204. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.04.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]