Abstract

Oxygen-derived free radicals, collectively termed reactive oxygen species (ROS), play important roles in immunity, cell growth, and cell signaling. In excess, however, ROS are lethal to cells, and the overproduction of these molecules leads to a myriad of devastating diseases. The key producers of ROS in many cells are the NOX family of NADPH oxidases, of which there are seven members, with various tissue distributions and activation mechanisms. NADPH oxidase is a multisubunit enzyme comprising membrane and cytosolic components, which actively communicate during the host responses to a wide variety of stimuli, including viral and bacterial infections. This enzymatic complex has been implicated in many functions ranging from host defense to cellular signaling and the regulation of gene expression. NOX deficiency might lead to immunosuppression, while the intracellular accumulation of ROS results in the inhibition of viral propagation and apoptosis. However, excess ROS production causes cellular stress, leading to various lethal diseases, including autoimmune diseases and cancer. During the later stages of injury, NOX promotes tissue repair through the induction of angiogenesis and cell proliferation. Therefore, a complete understanding of the function of NOX is important to direct the role of this enzyme towards host defense and tissue repair or increase resistance to stress in a timely and disease-specific manner.

Keywords: alcohol, COPD, NLRs, NOX, TLRs

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are small, oxygen-derived molecules that include oxygen radicals, such as superoxide and hydroxide, and certain non-radicals, such as hydrochlorous acid and ozone. ROS play dual, opposing roles dependent on the context. ROS-mediated stress has been implicated in various malfunctions and diseases, including cardiovascular pathology, immunodeficiency and pulmonary diseases.1,2,3,4,5 However, the NADPH oxidase (NOX)-mediated release of ROS, also called oxidative burst, leads to the elimination of invading microorganisms in macrophages and neutrophils and thereby serves as an inflammatory mediator.6 For many years, superoxide generation through NOX was thought to occur only in phagocytes; however, several enzymes responsible for ROS production have been recently identified in various tissues, which differ at the molecular level. These enzymes show similarities to phagocytic NOX (aka NOX2) and are collectively referred to as the NOX family. The NOX genes produce the transmembrane proteins responsible for transporting electrons across biological membranes, which leads to the reduction of oxygen into superoxide.7 The common functions of NOX proteins has been attributed to the conserved structural properties of these enzymes including the NADPH-binding site at the C-terminus, the flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-binding region located proximal to the C-terminal transmembrane domain, six conserved transmembrane domains, and four conserved heme-binding histidines.8 NOX enzymes mediate diverse functions in various organisms through redox signaling. The importance of ROS in host immunity has been clearly determined through the discovery of the genetic disorder, chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), which reflects defects in NOX2 (or associated subunits).9 CGD is characterized by defective neutrophil killing due to extremely low respiratory burst in these cells during phagocytosis.10,11 Patients with CGD are hypersensitive to various bacterial and fungal infections, and the accumulation of bacteria-containing phagocytes leads to the development of granulomas. This phagocyte accumulation reflects the inability of these cells to kill ingested pathogens or undergo apoptosis, due to defective NOX2 activity.12,13

The role of NOX has also been well established under non-pathological conditions. Vascular NOX generate ROS important for maintaining normal cardiovascular health through the regulation of blood pressure, which is essential to health, as aberrations from normal levels can be lethal.14,15 The presence of ROS reduces the bioavailability of the endothelial-derived relaxation factor, nitric oxide (NO), which regulates blood pressure.16,17 In normal kidneys, ROS is produced through NOX3, and these molecules regulate renal function through the control of Na+ transport, tubuloglomerular feedback and renal oxygenation.18,19,20 Furthermore, oxygen radicals increase NaCl absorption in the loop of Henle, resulting in the modulation of Na+/H+ exchange.21,22 Pulmonary NOX2 has been implicated in airway and vascular remodeling.22 The p22phox-dependent NOX2 regulates the proliferation23 and differentiation24 of smooth muscle cells through the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). ROS generation through Duox and NOX1 in the colon mucosa promotes serotonin biosynthesis, which is essential in regulating secretion and motility.25 NOX2 is involved in the normal functioning of the central nervous system through angiotensin II signaling in the nucleus tractus solitarius and the hypothalamic cardiovascular regulator nuclei.26,27 Moreover, microglial cells express NOX2 and p22phox, and both of these enzymes participate in the regulation of microglial proliferation and neuronal apoptosis during nerve growth factor deprivation.28 Thus, the importance of NOX in health and disease has been well established, and herein, we will discuss the structural and functional details of this enzyme.

History

Although respiratory burst was initially characterized in the early 20th century, the molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon were not deciphered until much later. In 1959, Sbarra and Karnovsky29 demonstrated that hydrogen peroxide production is dependent upon glucose metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation and is an energy-requiring process. In 1961, Iyer et al.30 observed the production of hydrogen peroxide during phagocytic respiratory burst, whereas in 1964, Rossi and Zatti31 demonstrated that NADPH is the primary substrate for generating oxidative burst-generating enzyme system. Almost a decade later, in 1973, Babior et al.32 reported that superoxide is the initial product of respiratory burst. These initial studies established the first clear picture of the biochemical role of the NOX system, and further studies deduced the intricate details of this pathway. In 1978, Segal et al.33,34 showed that cytochrome b558 (a complex of gp91phox and p22phox) is responsible for the production of ROS. In addition, mutations in the CYBA, NCF1, NCF2, or NCF4 genes (which encode p22phox, p47phox, p67phox or p40phox, respectively) were associated with the development of CGD.34 Subsequently, gp91phox, the catalytic subunit of the phagocyte NOX,35 and other components of the enzyme complex, including the transmembrane protein p22phox and the cytosolic subunits p40phox, p47phox and p67phox,36,37,38 were cloned and characterized. In 1970, Karnovsky et al.39 was the first to report the expression of NOX in neutrophils. Since then, knowledge concerning leukocyte oxide production has extensively increased, and several isoforms of this enzyme have been identified and characterized in various tissues and cells (Table 1).

Table 1. Expression of NOX family members and their components in various tissues or cells.

| NOX type/component | Expression observed in | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Cells | ||

| NOX isoforms | |||

| 1 | NOX1 | Colon and vascular smooth muscle, prostate, uterus79 | Endothelial cells79 |

| Colon epithelia125 | Osteoclasts79 | ||

| Uterus and placenta59 | Retinal pericytes, neurons, astrocytes and microglia272 | ||

| Rectum60 | |||

| 2 | NOX2 (gp91phox) | Phagocytes/granulocytes—induced through bacterial LPS165 | |

| Human umbilical vein endothelial cells166 | |||

| Coronary microvascular endothelial cells168 | |||

| Cardiomyocytes179 | |||

| CNS, endothelium, VSMCs, fibroblasts, skeletal muscle, hepatocytes and hematopoietic stem cells180 | |||

| 3 | NOX3 | Fetal kidney79 | |

| Liver, lung and spleen. Low levels in the adult colon and kidney273 | |||

| Inner ear127 | |||

| 4 | NOX4 | Kidney128 | Mesangial cells125 |

| Liver129 | Smooth muscle cells79 | ||

| Ovary and eye95 | Fibroblasts182 | ||

| Keratinocytes180 | |||

| Osteoclasts180,274 | |||

| Endothelial cells40 | |||

| Neurons159 | |||

| Hepatocytes170 | |||

| 5 | NOX5 | Spleen, testis, mammary glands and cerebrum79 | VSMCs276 |

| Fetal brain, heart, kidney, liver, lung, skeletal muscle, spleen, thymus239 | |||

| Prostate169 | |||

| Lymphatic tissue, endothelial cells275 | |||

| 6 | Duox1 | Thyroid, cerebellum and lungs139 | Thyroid cells79 |

| Ileum, cecum, and floating colon 146 | |||

| Respiratory tract epithelium278 | |||

| 7 | Duox2 | Colon pancreatic islets and prostrate279 | Thyroid cells in primary culture90 |

| Stomach, duodenum, ileum, jejunum, cecum, sigmoidal colon, floating colon and rectum280 | |||

| Pancreas281 | |||

| Tracheal and bronchial epithelium282 | |||

| Thyroid283 | |||

| Components of NOX | |||

| 1 | p67phox (NCF-2) | Kidney284 | Neutrophil37,38 |

| 2 | p47phox (NCF-1) | Neutrophils285 | |

| 3 | p40phox (NCF-4) | Mononuclear cells286 | |

| 4 | p22phox | Human coronary arteries208 | |

| 5 | RAC1 (p21) | Neutrophils287 | |

| 6 | RAC2 | Hematopoietic cells288 | |

| 7 | NOXO1, NOXA1 | Colon79 | |

Abbreviations: NOX, NADPH oxidase; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

Structure and assembly of NOX

NOX refers to the first characterized isoform NOX2, comprising six different subunits that interact to form an active enzyme complex responsible for the production of superoxide.40 Two NOX subunits, gp91phox (also known as the β subunit) and p22phox (also known as the α subunit), are integral membrane proteins that together comprise the large heterodimeric subunit flavocytochrome b558 (cyt b558). Under unstimulated conditions, the multidomain regulatory subunits, p40phox, p47phox and p67phox, exist in the cytosol as a complex.41 Upon stimulation, p47phox undergoes phosphorylation, and the entire complex subsequently translocates to the membrane and associates with cyt b558 to form the active oxidase (Figure 1). The activated complex transfers electrons from the substrate to oxygen through a prosthetic group, flavin, and a heme group(s), which carries electrons. The activation of the complex also requires two low-molecular-weight guanine nucleotide-binding proteins, Rac2 and Rap1A.42 Rac2 is localized in the cytosol in a dimeric complex with Rho-GDI (guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor), while Rap1A is a membrane protein.43,44 Upon activation, Rac2 binds guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and translocates to the membrane along with p40phox, p47phox, and p67phox (cytosolic complex) (Figure 1).45,46 During phagocytosis, the plasma membrane is internalized and ultimately becomes the interior wall of the phagocytic vesicle. Subsequently, O2− is released into the vesicle through the enzyme complex, and upon conversion of O2− into its successor products, the internalized target becomes submerged in a toxic mixture of oxidants.47 Rap1A and cyt b558 are delivered to the plasma membrane through the fusion of secretory vesicles, thereby facilitating the release of these proteins to the exterior. ROS production is not restricted to phagocytic cells, and the discovery of gp91phox homologs has significantly improved our understanding of free radical production. Collectively known as the NOX family, these gp91phox homologs include several differentially expressed members: NOX1, NOX2 (formerly known as gp91phox), NOX3, NOX4, NOX5, Dual oxidase Duox proteins (Duox1 and Duox2) (Table 1).

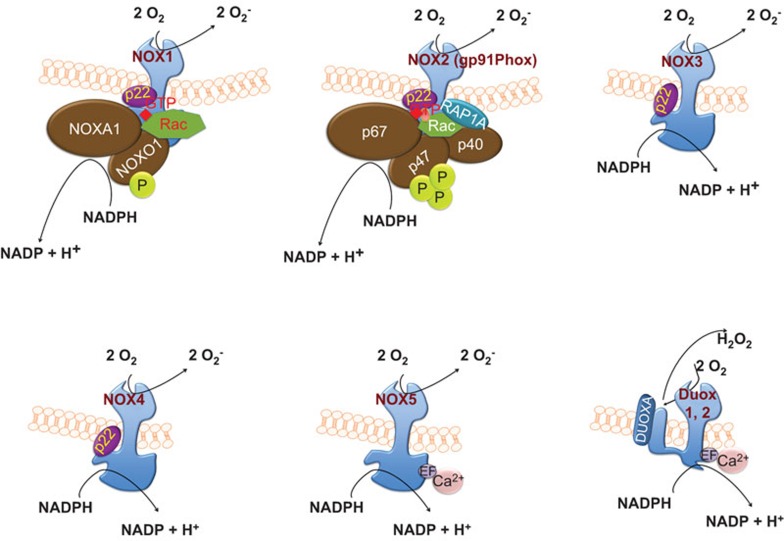

Figure 1.

Assembly and activation of NOX enzymes: NOX1 and NOX2 activation involves the phosphorylation of NOXO1 and p47phox, respectively, the translocation of the entire multidomain complex, including p40phox, p67phox and Rac from the cytosol to the membrane and the transfer of electrons from the substrate to oxygen. Similar to NOX1 and NOX2, NOX3 is p22phox-dependent, but it does not bind to Rac. NOX4 activation involves p22phox and Poldip2. In contrast, NOX5 and Duox activation is calcium-dependent. Duox proteins isolated from the thyroid gland possess a peroxidase-like domain. The mature form of Duox generates hydrogen peroxide, which may be the ultimate end product, likely reflecting the rapid dismutation of superoxide. NOX, NADPH oxidase.

Some NOX family members possess additional features, including an additional N-terminal transmembrane domain and/or peroxide homology domain.48 NOX2, commonly referred to as gp91phox, possesses six transmembrane domains, with both the C- and N-terminus facing the cytoplasm. In addition, constitutive association with p22phox stabilizes NOX2.49,50 The activation of NOX2 requires translocation and association with phosphorylated p47phox for the binding of other cytosolic components, including p67phox and p40phox, to the NOX2/p22phox complex.51,52,53 Upon complex assembly, the GTPase Rac first interacts with NOX2 and subsequently interacts with p67phox, resulting in an activated complex for the production of superoxide through electron transfer from cytosolic NADPH to oxygen on the luminal or extracellular region.42,54 The subcellular distribution of NOX varies according to cell type and localization ranges from the plasma membrane to intracellular compartments, including secondary and tertiary granules. NOX1 was identified as the first homolog of NOX2 and shares 60% amino-acid identity.55,56 Data concerning the subcellular localization of NOX1 are scarce; however, it has been suggested that this protein is membrane localized and potentially present within caveolar rafts.57 NOX1 is widely expressed in various cell types (Table 1),58,59,60 with notably high expression in the colon epithelium.61 Evidence of the dependency of NOX1 activity on cytosolic subunits was supported through the discovery of NOX organizer 1 (NOXO1), a homolog of p47phox, and NOX activator 1 (NOXA1), a homolog of p67phox.62,63,64 For activation, NOX1 requires the membrane subunit (p22phox), cytosolic subunits, and the Rac GTPase. The stringency of dependence on the cytosolic subunits varies between NOX2 and NOX3, which shares 56% amino acid identity with NOX2 and was first identified by Kikuchi et al. in 2000.65,66,67,68,69 Similar to NOX1 and NOX2, NOX3 is p22phox-dependent; however the in vivo relevance of p22phox for NOX3 function remains unclear.70,71 Furthermore, the requirement for NOXO1 and NOXA1 for the activation of NOX3 has been shown in some studies, although the involvement of p47phox and p67phox has not been demonstrated under physiological conditions, and the role for Rac in NOX3 activation remains controversial.66,70,72,73

NOX4, identified by Geiszt et al.74 in 2000, shares approximately 39% sequence homology with NOX2.48,74 The activity of NOX4 strongly depends on p22phox75 but not on cytosolic subunits.76 Furthermore, the involvement of Rac in the activation of NOX4 remains questionable.77 Poldip2, a polymerase (DNA-directed) delta-interacting protein, interacts with NOX4/p22phox as a positive regulator in vascular smooth muscle cells.78 The association of Poldip2 with p22phox has been demonstrated using GST pull-down assays.78 The analysis of NOX4-rich tissues (e.g., aorta, lung and kidney) using western blotting, qRT-PCR and immunohistochemistry indicates increased Poldip2 expression.78,79 The role of Poldip2 as a positive regulator of NOX4 in association with p22phox has been demonstrated using siRNA against Poldip2 in vascular smooth muscle cells.78

Two independent research groups identified NOX5, and this protein comprises five isoforms. Banfi et al.80 identified isoforms α, β, γ and δ, while Cheng et al.81 identified a fifth isoform, NOX5ε or NOX5-S. NOX5 isoforms α–δ possess a long, intracellular N-terminal domain that contains a Ca2+-binding EF-hand region,80,82 whereas the fifth isoform lacks the EF-hand region and is structurally similar to NOX1-4.81 NOX5 isoforms α–δ do not require p22phox or cytosolic subunits for activation, but rather, depend on cytosolic calcium for activation, reflecting the presence of a Ca2+-binding domain.71 In contrast, the NOX5ε isoform, which lacks a Ca2+-binding domain, depends on the cAMP response element binding protein for activity.83

The dual oxidases (Duox1 and Duox2, also known as thyroid oxidases) contain a NOX homology domain similar to that of NOX1-4, an EF-hand region like NOX5, and a seventh transmembrane at N-terminus which is a peroxidase-like domain but lacking the few functionally essential amino acids.84,85,86 The dual oxidases were first identified in the thyroid gland in 1999,87 and these enzymes share approximately 50% amino acid identity with NOX2. Both Duox1 and Duox2 have two N-glycosylation states88,89 and have been identified as glycosylated proteins in the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum.88,90,91 The retention of Duox proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum depends on maturation factors DuoxA1 and DuoxA2.92 The partially glycosylated, immature form of Duox2 generates O2, whereas the mature form generates H2O2.93 Although studies have shown the direct physical interaction of Duox proteins with p22phox, there is no direct evidence regarding whether the activation of these proteins requires p22phox.88,93,94 Furthermore, Duox proteins do not require cytosolic activator or organizer subunits for activation, but can be activated through Ca2+.93

NOX family members not only regulate normal physiological functions, but also contribute to the pathogenesis associated with infections, vascular disorders and impaired immune responses due to environmental factors. In this review, we will highlight the structure and pathogenesis associated with NOX, including the role for this enzyme in bacterial/viral infections, vascular disorders and impaired immune responses due to cigarette smoke and alcohol exposure.

Cytosolic components of the oxidase

The cytosolic components of NOX include p40phox, p47phox and p67phox. p47phox is phosphorylated in stimulated neutrophils, which increases the binding of this component to p67phox and Rac approximately 100- and 50-fold, respectively, and these interactions lead to the translocation of the cytosolic complex to the membrane.95 Neutrophils deficient in p47phox do not show the efficient transfer of the cytosolic oxidase complex to the membrane; however, p67phox-deficient neutrophils exhibited normal p47phox translocation.95 p47phox stabilizes or facilitates the interaction of p67phox and Rac1 with cytochrome b558; however, at high molar concentrations of p67phox and Rac1, p47phox is not required for these interactions.96,97

Electron flow from NADPH to oxygen through the redox centers is activated subsequent to the assembly of the cytosolic components with cyt b558. The individual roles of p47phox and p67phox in electron flow have been further demonstrated using a cell-free system with samples from normal and CGD patients.98 The results of this study showed that p67phox alone can facilitate electron transfer from NADPH to the flavin center, whereas p47phox is required for electron transfer from the flavin center to cytochrome b558. Furthermore, p67phox contains a catalytically essential binding site for NADPH; however, an NADPH-binding site is also present on cytochrome b558.99,100,101 The relationship between these two NADPH-binding sites has not been determined, although notably, cyt b558 alone catalyzes active O2− production using NADPH as a reductant.40 The reduced interaction of mutated p67phox with Rac and impaired translocation of the cytosolic oxidase complex in the activated phagocytes of CGD patients have recently been reported.46,102 These findings suggest that both p47phox and p67phox are important components of NOX2. Other NOX isoforms are either regulated through a similar complex (NOX1, NOX3 and NOX4) or via Ca2+ (NOX5 and Duox).

Membrane components of the oxidase

The NOX flavocytochrome b558 mediates the terminal steps in electron transfer and generates O2− during respiratory burst. In phagocytes, flavocytochrome b558 is a membrane-bound heterodimer comprising the large glycosylated subunit gp91phox and the small non-glycosylated subunit, p22phox, also known as β-and α-subunits, respectively. FAD and NADPH bind to the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of gp91phox, whereas the N-terminal 300 amino acids are predicted to form six transmembrane α-helices.103 There are also two membrane-embedded non-identical heme groups per flavocytochrome b558 heterodimer, which are non-covalently coordinated by histidines.104,105,106 The electrons are first transferred from NADPH to FAD, followed by transfer to the heme group, which reduces O2 to O2−.107 These two electron transfer steps are accomplished through gp91phox in complex with the necessary cofactors.

The α-subunit, p22phox, comprising 195 amino acids, is another membrane-bound subunit of NOX.108 p22phox associates with gp91phox in a 1∶1 complex and contributes to both the maturation and stabilization of this protein. The N-terminal portion of p22phox is predicted to contain three transmembrane α-helices, whereas the C-terminal cytoplasmic portion is devoid of predictable structure, but rather, is a proline-rich region that undergoes phosphorylation at a threonine residue. Notably, the physiological role for the addition of this phosphate group is not understood.109,110 The coexpression of the flavocytochrome b558 subunits, gp91phox and p22phox in COS7 cells resulted in the expression of functional flavocytochrome, while the expression of either gp91phox or p22phox alone in COS7 membranes did not rescue the flavocytochrome b558 function in cell-free NOX assays. Thus, both flavocytochrome subunits are required for the functional assembly of the oxidase.111

The GTPase Rac

Rac is a member of the Rho-family of small GTPases, and this protein plays an indispensable role in the regulation of various signaling pathways, including cytoskeletal remodeling and chemotaxis.112 There are two differentially expressed isoforms of Rac, Rac1 and Rac2. Rac1 is ubiquitously expressed and activates NOX in non-hematopoietic cells, while Rac2 expression is confined to hematopoietic cells, specifically neutrophils, where this protein acts as a major NOX2-activating Rac GTPase.113,114 However, both proteins comprise 192 amino acids and share 92% sequence homology. Most of the differences between Rac1 and Rac2 occur in the insertion helix and hypervariable C-terminus, although the mediation of O2− production through these enzymes is similar in reconstituted, cell-free systems using purified proteins.115,116 Guanosine diphosphate maintains Rac in an inactive state, while GTP induces the active state. The activation of Rac mediates the interaction of this enzyme with downstream effectors and the propagation of the signaling responses, regulated through GTPase-activating proteins and guanine-nucleotide-exchange factors. GTPase-activating proteins mediates the hydrolysis of GTP into guanosine diphosphate, whereas guanine-nucleotide-exchange factors facilitate the detachment of guanosine diphosphate and binding of GTP.117

Rac proteins, similar to other small GTPases, contain an effector region in the N-terminus that mediates interactions with effector proteins, including p67phox.97,118 Activated Rac recruits p67phox, which associates with p47phox and cytochrome.119,120,121 Specifically, a recent study showed the absolute requirement for Asp57 in this region of Rac2 based on a mutation in a CGD patient who showed severely impaired neutrophil responses, including adhesion, chemotaxis, and superoxide production.122,123,124 NOX1 activation is mediated through Rac1, and there is increasing evidence of an important role for the Rac-mediated activation of NOX proteins in various cardiovascular ailments, making these signaling complexes important therapeutic targets.125

NOX, innate immunity and bacterial infections

In addition to NOX, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) have also been identified as key components of innate immunity. PRRs are germline-encoded proteins that recognize conserved structures on microorganisms called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). PAMPs include lipopolysaccharides, lipoteichoic acids and lipoproteins located on the pathogen surface, and PRRs include Toll-like (TLRs), nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like (NLRs), RIG-like and C-type lectin receptors.

TLRs are type 1 integral membrane glycoproteins that function as homodimers and possess extracellular lectin-like receptors and cytoplasmic signaling domains that recruit signaling molecules.126 The stimulation of TLRs leads to downstream signaling events, ultimately resulting in the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines important for controlling infections. TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5 and TLR6 are located on the cell surface, whereas TLR3, TLR7 and TLR9 are localized to the endosomal membrane. TLR1/TLR2 and TLR2/TLR6 heterodimerize and recognize structures associated with bacteria, viruses and fungi. TLR2 activation leads to the recruitment of the Toll-interleukin receptor domain, containing adaptor protein and MyD88, which results in the activation of NF-κB and the production of cytokines and chemokines.127,128 TLR4 recognizes lipopolysaccharides (LPS) on the surface of Gram-negative bacteria, and this receptor plays a role in establishing commensal colonization and maintaining tolerance to commensal bacteria.129 TLR5 recognizes flagellin, a constituent of the flagella of motile bacteria and is important for the detection of invasive flagellated bacteria at the mucosal surface.127 TLR5 plays an indispensable role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis through the regulation of host defenses against enterobacterial infections. TLRs 3, 7 and 8 recognize viral RNAs and synthetic viral RNA analogs, while TLR9, which is localized intracellularly in the endosomal compartment, recognizes bacterial unmethylated CpG DNA, and TLR11 senses profilin and uropathogenic bacteria.130

In addition, NLRs belong to a family of cytosolic PRRs that recognize intracellular PAMPs. The NLR family, also referred to as the NOD, NALP, or CATERPILLER protein family,131 comprises more than 20 cytosolic proteins132 and has been classified into two subfamilies, the CARD and Pyrin subfamilies, based on the presence of a specific death domain. The former is also known as the NLRC (NACHT, lectin-like receptor and CARD domains-containing proteins), whereas the latter is known as the NLRP (NACHT, lectin-like receptor and PYD domains-containing proteins). NOD1 recognizes peptidoglycan, a component of the bacterial cell wall, whereas NOD2 recognizes muramyl dipeptide, a peptidoglycan constituent of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Figure 2).133 A different set of NLRs, including Ipaf and Naip, are activated through bacterial flagellin. NLRP3 (cryopyrin) is activated through a variety of molecules, including bacterial RNA, pore-forming toxins and endogenous ligands, including uric acid crystals and ATP.134,135,136,137 NLRP1, NLRP3 and NLRC4 form inflammasomes that are involved in inflammatory caspase maturation.138 In addition to direct activation through PAMPs, inflammasomes can also be activated via ROS.

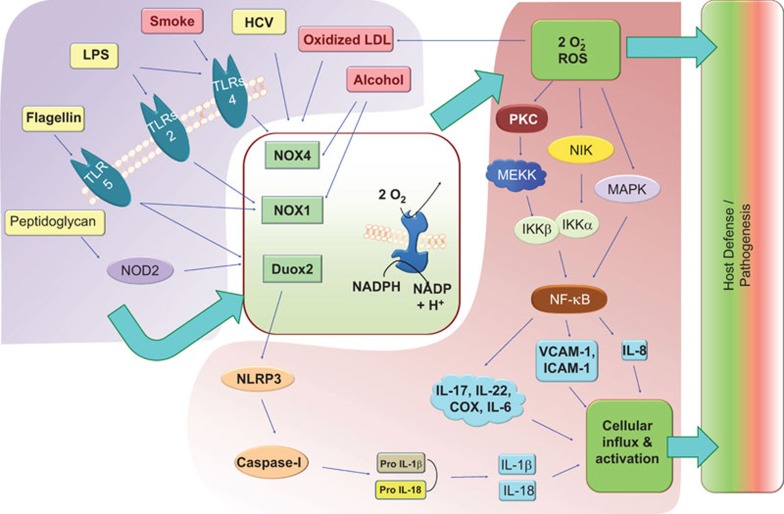

Figure 2.

The NOX system is central to host defense. When induced through various triggering elements (top-left block), NOX family members become activated, producing ROS (central block). The block arrows represent the main signal pathway. While ROS directly kills microorganisms, additional downstream cellular factors work in an orchestrated manner to mount pressure against the invading pathogens or the cells harboring these microbes (right block). However, when non-pathogenic inducers, such as cigarette smoke or alcohol, induce the NOX system, ROS exerts damaging effects on the host, causing pathogenesis. The signaling mechanisms illustrated in this figure include the induction of TLR4-mediated signaling through cigarette smoke and LPS, leading to the activation of NOX4. TLR5 recognizes flagellin and activates NOX1 and Duox2. Virus-like HCV also activates NOX4, leading to ROS production. TLR5 and NOD2, when activated through flagellin or peptidoglycan, respectively, activate Duox2, leading to NLRP3 binding and activation. Furthermore, the NLRP3-mediated induction of caspase-1 activity leads to the maturation of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, promoting the influx and activation of lymphocytes. ROS, produced through NOX, activates NF-κB through various intermediates, including PKC, MEKK and NIK, thereby inducing the upregulation of IL-8, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 and promoting the lymphocyte influx important for host defense/pathogenesis. HCV, hepatitis C virus; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; MEKK, MEK kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NIK, NF-κB-inducing kinase; NOX, NADPH oxidase; PRC, protein kinase C; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TLR, Toll-like receptor; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

Crosstalk between TLRs and NOX

NOX2-mediated respiratory burst plays an indispensible role in antimicrobial innate immune responses. Moreover, it has been shown that PRR receptor-mediated ROS generation is coupled with NOX isozymes in phagocytic cells.139 However, the molecular mechanisms underlying ROS generation downstream of PRRs reportedly differ. In response to LPS, the cytoplasmic region of TLR4 recruits MyD88, linking TLR4 to IL-1R kinase associated with TRAF6. The sequential activation of IL-1R kinase and TRAF6 results in NF-κB activation.140 In 2004, Park et al. reported the direct interaction of NOX4 through TLR4 in kidney epithelial cells (HEK293T) and U937 monocytic cells.141 Specifically, the TIR region of TLR4 physically interacts with the C-terminus of NOX4, and this interaction is important for LPS-mediated NF-κB activation in human aortic endothelial cells.142 NOX1, which is predominantly expressed in colon epithelial cells, 55 is activated through a TLR5-mediated pathway through p41NOXA and p51NOX homologs of p47phox and p67phox, respectively.143,144,145 Recombinant flagellin from Salmonella enteritidis stimulates ROS generation through TLR5 in T84 cells, and the cotransfection of p41NOXA and p51NOX significantly enhances ROS production.146 In the nasal airway epithelium, ROS generation and IL-8 expression has been associated with interactions between TLR5 and another NOX isozyme, Duox2, in response to flagellin exposure.147,148 Furthermore, in response to flagellin, the TIR domain of TLR5 interacts with the C-terminal region of Duox2 for the activation of this protein in a calcium-dependent manner.149 These studies reveal that ROS production is associated with TLR, and the induction mechanisms are different between TLR4 and TLR5.

Crosstalk between NLRs and NOX

Studies using diphenyliodinium, a NOX inhibitor, have shown that ROS is generated in response to the activation of NOX2.150 NLRP3 inflammasome activators, including silica and ATP, require ROS production for activation.151 Thus, these studies suggest that NOX functions upstream of NLR signaling.152 Furthermore, another NOX family member, Duox2, is involved in NOD2-dependent ROS production in response to muramyl dipeptide induction.153

Hyperhomocysteinemia (hHcys) is a significant risk factor for many degenerative diseases and pathological processes, including cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, and neurological and renal diseases. The lethal consequences of hHcys, including glomerular dysfunction, result from the activation of the NALP3 inflammasome. The ROS-mediated activation of inflammasomes in podocytes is one of the putative underlying mechanisms of hHcys.154,155 NOX4 is reportedly expressed in kidney cells and is a major producer of ROS.156 In addition, normal renal function is restored after the inhibition of NOX,157 and either the inhibition of NOX4 or silencing of the gp91phox gene attenuates hHcys-induced inflammasome formation in podocytes.158 As NALP3 activation leads to caspase-1 induction and IL-1β production, it is reasonable that the inhibition of NOX also attenuates hHcys-induced caspase-1 activity and IL-1β production in podocytes. Furthermore, apocynin, diphenyleneiodonium, gp91ds-tat and gp91phox siRNA are all inhibitors of NOX-mediated ROS production, and these proteins have been used to show the involvement of this complex in disease.159 Therefore, we concluded that NOX activation leads to ROS production, which induces NLR signaling and the formation of inflammasomes, resulting in inflammation and tissue injury in hHcys.

Mutual tuning between chemokines and NOX

The NOX system is activated in pulmonary neutrophils in response to bacterial infection. This activation is regulated through the chemokines CXCL1 and LTB4, as demonstrated in CXCL1−/− mice infected with Klebsiella. The intrapulmonary administration of LTB4 reverses immune defects and leads to improved survival, cytokine/chemokine expression, NF-κB/MAPK activation and ROS/RNS production. Similarly, the chemokine MCP-1 causes lysosomal enzyme release and H2O2 production in monocytes.160 Furthermore, decreased p47phox expression in both neutrophils and macrophages from MCP-1 and CCR-2 gene-deficient mice suggests that the MCP-1/CCR-2 axis regulates the expression and activation of the NOX system.161

The silencing of NOX4 using short, interfering RNA leads to a reduction in ROS production, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and MCP-1 expression in response to LPS.141 Moreover, treatment with antioxidants or the inhibition of p22phox using neutralizing antibodies or antisense oligonucleotides in vascular smooth muscle cells inhibited p38 MAP kinase activation and MCP-1 expression in response to thrombin.162 Similarly, treatment with antioxidants abolished angiotensin II-induced ROS production and MCP-1 expression in cultured human mesangial cells.163 A recent study also demonstrated that the treatment of Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric epithelial cells with red ginseng extract inhibited MCP-1 and inducible NOS expression through the inhibition of NOX activity and the JAK2/STAT3 pathway.164 Each of these studies highlights a direct link between chemokine signaling and NOX activation.

Role of NOX in viral pathogenesis

Acute respiratory tract infections resulting from influenza virus infection leads to cell death, reflecting an over-exuberant immune response that causes localized tissue damage and systemic illness via the induction of a cytokine storm.165,166 The production of superoxide downstream of NOX limits influenza virus propagation through the death of the infected cells; 167 however, ROS also acts as second messengers to activate redox-sensitive transcription factors, which elicit immune and subsequent inflammatory responses that eventually cause damage (Figure 2).168 Reduced ROS generation through the genetic depletion or malfunction of NOX enzymes favors pulmonary influenza infection potentially through the promotion of professional phagocyte populations. Inhibitors of superoxide effectively improve lung pathology and survival during viral pneumonia, suggesting that superoxide contributes to the pathogenesis of viral disease.169 Hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes mortality due to the induction of various liver diseases and liver cancer. The occurrence of chronic infection and liver injury likely reflects HCV-mediated oxidative stress. The HCV polyprotein undergoes proteolytic processing, giving rise to the viral core proteins, non-structural protein 3 (NS3), NS4 and NS5, which trigger ROS production in human monocytic cells.170 The translocation of p47phox and p67phox from the cytoplasm to the membrane has been visualized in HCV-infected cells, confirming the involvement of NOX2 during infection. Furthermore, the role of calcium influx in the NS3-induced activation of NOX has been confirmed using digital microscopy to visualize rapid calcium signaling. The calcium channel inhibitor, lanthanum chloride, not only reduces calcium signaling but also inhibits oxidative burst.170 NOX4 is also responsible for superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generation in hepatocytes during HCV infection.171,172 Human hepatoma cells transfected with HCV cDNA exhibit increased NOX4 mRNA and protein expression and prominent NOX4 localization in the nuclear compartment.171 Furthermore, human hepatocytes (Huh-7) infected with HCV showed a fivefold increase in NOX4 mRNA expression compared with cells transfected with vector alone.172 Gene silencing studies using siRNA directed against NOX4 have revealed reduced levels of ROS and nitrotyrosine in HCV-infected liver tissue, confirming that NOX4 is a major source of oxidative stress during HCV infection.171 Interestingly, a role for transforming growth factor (TGF-β1) as a mediator in the upregulation of NOX4 during HCV infection has been established, as the HCV-induced over-expression of NOX4 was restricted using antibodies against TGF-β1.171 Moreover, it has been reported that TGF-β1 induces NOX4 expression, and the concentration of TGF-β1 is elevated in hepatitis C patients.173,174

Cigarette smoke exposure/COPD and NOX

Cigarette smoke is one of the most potent risk factors for peripheral cardiovascular-related and cerebrovascular diseases. The cigarette smoke contributes to cellular oxidative stress, leading to pulmonary inflammation, asthma, and tumors.175,176 Human alveolar epithelial NOX is activated through ligand binding to the kinin B1 receptor, and this interaction contributes to superoxide anion production and leads to downstream detrimental effects.177 The principal ligand of this receptor is bradykinin, which is involved in various neurological and cardiovascular diseases, the chronic phase of inflammation, trauma, burns, shock and allergy.178 Cigarette smoke also induces p47phox translocation and TLR4/MyD88 complex formation. The direct effects of smoking on cardiac remodeling include alterations in ventricular mass, volume and geometry, and heart function. In addition, smoking not only induces morphological alterations and systolic dysfunction but also augments heart stress, which is characterized by an increase in NOX activity. Furthermore, a reduction in the activity of antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase and superoxide dismutase, has also been observed following exposure to cigarette smoke. These perturbations in the oxidant and anti-oxidant balance lead to lung and airway inflammation. Several studies have reported that cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E-2 play a critical role in respiratory inflammation. Prostaglandin E-2 increases both IL-6 production and leukocyte counts in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid.179 In human tracheal smooth muscle cells, the induction of cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E-2 is dependent on NADPH signaling.180 In addition, leukocyte influx into BAL fluid was also reduced using an NOX inhibitor following exposure to cigarette smoke.180 Thus, these studies have revealed that cigarette smoke-induced ROS generation is mediated through NOX, and these events leads to the eventual induction of cyclooxygenase and IL-6-dependent airway inflammation (Figure 2).180

Compared with non-smokers, the neutrophil count in COPD patients is higher in both BAL fluid and in the sputum, a hallmark of COPD.181 Furthermore, circulating neutrophils from patients with stable COPD produce a larger respiratory burst than neutrophils from non-smokers.182 Mac-1 is an integrin molecule expressed on neutrophils, and this molecule plays a role in neutrophil emigration and recruitment and the adhesion of these cells to the endothelium. COPD patients exhibit the significant upregulation of Mac-1 and ROS, thus causing excessive neutrophil recruitment.182 The in vitro phosphorylation of Mac-1 leads to NOX activation, and the crosslinking of Mac-1 induces neutrophil respiratory burst.183,184,185 In COPD patients, increased oxidants present in cigarette smoke or excessive ROS production in leukocytes enhance inflammation through the activation of NF-κB,186 which regulates genes for many inflammatory mediators, such as the cytokines IL-8, TNF-α and nitric oxide.187 Furthermore, the increased oxidant burden causes the upregulation of antioxidant genes that play protective roles. For example, the induction of the GSH gene increased the accumulation of GSH in the epithelial lining fluid in the airspaces, which is important for prevention against oxidative injury.188

Chronic alcohol exposure and oxidative stress

Chronic alcohol abuse is one of the most important risk factors for a type of lung injury called acute respiratory distress syndrome. Previous studies have shown that alcohol abuse causes significant oxidative stress within the alveolar space and impairs both alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages.189 This alcohol-induced lung dysfunction is attenuated through treatment with glutathione precursors, 190 and glutathione depletion in the alveolar space is associated with oxidative stress and alveolar macrophage dysfunction.191 Alveolar macrophages play an indispensable role in innate and acquired immunity, and the ability of alveolar macrophages to bind and internalize pathogens is impaired through chronic alcohol ingestion.192 The expression of NOX2 in alveolar macrophages is the main source of ROS generation in the lungs.193 The ligation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma regulates NOX2 expression in the lungs following chronic alcohol ingestion.194 In addition, chronic alcohol ingestion reduces the level of the antioxidant glutathione in BAL fluid through the augmentation of the activity of the renin-angiotensin system.195 Of the two classes of angiotensin, angiotensin II stimulates NOX2 expression and induces intracellular oxidative stress. Because renin-angiotensin system regulates the level of antioxidant glutathione after chronic alcohol ingestion, the use of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, such as lisinopril, prevents ethanol-induced glutathione depletion and provides protection against epithelial dysfunction.196 Alcohol abuse is also correlated with bacterial pneumonia, as alcoholic patients are more prone to Klebsiella pneumoniae infections than non-alcoholic patients.197 In addition, chronic alcohol abuse augments the colonization of the mouth and pharynx by Gram-negative bacteria.198 Considering the deleterious effects of alcohol abuse on the entire airway from the mouth to the alveolus, the overlapping risk for pneumonia and lung injury is not surprising.

Alcohol exposure also negatively affects the liver, with fibrosis and cirrhosis being major histological features.199 Alcohol increases the gut permeability to bacterial endotoxins, leading to the activation of resident hepatic macrophages and Kupffer cells through the induction of NOX1 and NOX2 ROS production in response to endotoxins.200,201 The chronic ethanol treatment of wild-type or p47phox knockout mice with severe liver injury resulted in detectable free radical production and NF-κB activation only in the wild-type group, therefore, p47phox might be a potential therapeutic target for alcohol-induced liver injury. These findings suggest that the oxidants generated through NOX, most likely derived from Kupffer cells, play an important role in alcohol-induced liver injury.199

Vascular disorders: role of NOXs/innate immunity/Rac

Although several sources, including xanthine–xanthine oxidase, lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase and NOS contribute to the generation of vascular superoxide, the NOX-mediated generation of superoxide has been clinically associated with atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by lipid retention and atherosclerotic lesions.202 The expression of NOX1 and NOX4 in human vascular smooth muscles and NOX4 in endothelial cells has been associated with the development of cardiovascular disorders.57,203 Oxidized LDL induces NOX4 expression in the endothelium, thereby increasing oxidant production.204 The formation of compromised atherosclerotic lesions has been reported in cases of reduced monocyte infiltration into the blood vessel wall and in LDL receptor-deficient mice.205,206,207 Expression of adhesion molecules (such as selectins, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) induced by NF-kB downstream of ROS in the vascular endothelium play indispensable roles in atherogenesis. The activation of NF-κB downstream of ROS induces the expression of adhesion molecules in the vascular endothelium, such as selectins, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and ICAM-1, which play indispensable roles in atherogenesis.209,210 Additionally, ROS induces the inactivation of endothelial NO through superoxide anions, which reduce the bioavailability of NO, an important vasodilator, and promote vasoconstriction.206,207,211,212,213

Interestingly, the exposure of macrophages to LPS from Chlamydia pneumoniae stimulates the over-expression of the fatty acid-binding protein, adipocyte protein 2 (ap2), and augments the uptake of LDL and foam cell formation.214,215 Activated macrophages dramatically affect vascular cell function through the release of bioactive molecules, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS.212

Innate immune cells provide the first line of defense against invading pathogens.205 In contrast, these cells play a detrimental role in atherosclerosis. TLR ligands, such as LPS and aldehyde-derivatized proteins, are not only involved in microbial pathogenesis but also in atherogenesis, thereby establishing a close link between innate immunity and atherosclerosis.216 Hektoen and Osler reported the co-existence of tuberculosis and atherosclerosis characterized by aberrant changes in the arterial wall.217 Moreover, in vivo studies in rabbits and serological evidence have shown an association between Chlamydia pneumoniae and the development of atherogenesis. 218 The studies also suggest that TLR-mediated signaling plays a mechanistic role in atherosclerosis. TLRs recruit adaptor molecules to the intracellular signaling domain, leading to the activation of NF-κB and mediators of innate immunity, such as cytokines, vasoactive peptides, histamine, and eicosanoids, which are also involved in atherogenesis.219 The TLR-mediated activation of cytokines and growth factors, such as platelet-derived growth factor and heparin-binding growth factor, promote the proliferation of vascular cells.220 Intriguingly, a direct link between TLRs and NOX has also been proposed. LPS activates NOX4 through TLR4, and the siRNA-mediated silencing of NOX4 in the U937 monocytic cell line expressing NOX4 attenuates LPS-induced superoxide production.141 This evidence suggests a correlation between atherosclerosis, innate immunity and NOX.

Furthermore, calcification, an important step in the progression of atherosclerosis, is strengthened through TGF-β.220 In addition, immunogenic cross-reactions between bacterial and human heat shock-protein 60 have also been reported in atherogenesis.221,222 Moreover, it has been reported that the proliferation of human vascular smooth muscle cells through Chlamydial heat shock-protein 60 is driven in a TLR4-dependent manner.223

As a key signaling molecule, Rac plays an indispensable role in both healthy and diseased cardiovascular systems. In mice, Rac is responsible for the progression of hypercholesterolemia, which includes increased NADPH-derived superoxide production, impaired endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation, increased macrophage infiltration into the vasculature and enhanced plaque rupture.224 In the atherogenic mouse, Rac1–NOX-mediated ROS generation inhibits NO synthesis and promotes the formation of LDL and various inflammatory mediators, such as ICAM-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, which contribute to the progressive development of atherosclerosis.225 A transgenic mouse model constitutively expressing Rac v12 under the control of the α-actin promoter for smooth muscle selective expression exhibited hypertension and enhanced superoxide production.226 Furthermore, angiotensin II-induced hypertension has been directly associated with elevated vascular NOX-mediated superoxide production and high blood pressure, which is regulated through the translocation of Rac1-GTPase to the cell membrane.227,228 High blood pressure induces biochemical stress, which causes NOX1/NOX4-mediated superoxide generation, resulting in vascular dysfunction.229 Moreover, Rac is responsible for the development of thrombogenicity of the vascular wall, which attributes to vascular remodeling through the activation of NF-κB and ROS.230 Thus, these studies suggest a direct role for Rac activation in cardiovascular diseases. Thus, it is apparent that Rac and mediators of innate immunity/NOX play important roles in vascular diseases.

NOX inhibitors

Previous studies have focused on strategies to enhance the removal of ROS using either antioxidants or drugs that enhance endogenous antioxidants. Recent studies have focused on proteins further upstream to reduce oxidative stress using blocking enzymes that promote ROS production. Unfortunately, the currently available NOX inhibitors that target the catalytic site lack specificity. Because the structure of NOX2 enzymes has been elucidated and it has been shown that the correct assembly of NOX2 enzymes is critical for function, the inhibition of assembly represents a novel therapeutic approach. For example, the membrane association of the GTPase Rac 1, which is essential for NOX activation, is prevented using HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors.231 Similarly, apocynin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyacetophenone) is an orally active agent that also blocks NOX assembly.232 Originally isolated from the medicinal plant Picrorhiza kurroa, apocynin inhibits both intracellular and extracellular ROS production through the inhibition of the phagosomal association of the cytosolic protein p47phox.233,234 However, a limitation of apocynin is that this protein requires peroxidase for activation, and therefore, apocynin activity is not instantaneous.235,236 The nitration and nitrosylation also lead to the inhibition of NOX. For example, the NO donor, DETA-NONOate, suppresses basal NOX-dependent superoxide production.237 In addition, ethyl pyruvate plays a significant role in oxidative decarboxylation and is an effective inhibitor of NOX.238 Furthermore, there are inhibitors that perturb the signal transduction of NOX-related pathways. Aqueous solutions of pyruvate rapidly undergo an aldol-like condensation reaction to form 2-hydroxy-2-methyl-4-ketoglutarate (parapyruvate), a potent inhibitor of both the extracellular and intracellular production of ROS through transferrin receptor targeting for the recognition of LPS in microglia cells.239 Membrane channel blockers also act as NOX inhibitors.165 Angiotensin II stimulates NOX-derived ROS production in smooth muscle cells through the activation of calcium channels. 240 Therefore, calcium channel antagonism is an important approach to reduce NOX activity, specifically NOX5 or Duox proteins. Felodipine and amolodipine are two commonly used calcium channel blockers that significantly suppress NOX activity.241 Gomicin C, a lignin extract from Schizandra chinensis, decreases cytosolic calcium levels in intracellular stores and exhibits weak inhibitory action against NOX2.242 Compounds, such as 6-aminonicotinamide, dearth the availability of electron donors, such as NADPH, and inhibit the pentose phosphate pathway, which precludes NOX activation.243,244 Furthermore, NOX activation is also regulated through angiotensin II, platelet-derived growth factor and TGF, all of which are blocked through valsartan.245,246

Small molecule inhibitors also offer a powerful tool for NOX inhibition due to their high affinity towards targets. For example, sulfhydryl-modifying reagents, such as N-ethylmaleimide or p-chloromercuribenzoate, inhibit the assembly and activation of NOX2.247,248 Honokiol, isolated from the herb Magnolia officinalis, blocks oxidative burst in both intact cells and particulate neutrophil fractions. This molecule is potentially useful in pathological conditions because it completely inhibits superoxide production at a low concentration, even after the enzyme is activated.242,249 Another plant-derived compound, Plumbagin, inhibits NOX4 oxidase activity and exerts anticarcinogenic and anti-atherosclerosis effects in animals.250 The decreased activity of NOX4 has been demonstrated in plumbagin-treated human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) and brain tumor LN229 cells.250 Prodigiosins are natural red pigments produced from the bacteria Serratia marcescens that inhibit NOX2 through membrane binding and the inhibition of the interaction between Rac and p47phox.251 ten Freyhaus et al. characterized a novel NOX inhibitor, 3-benzyl-7-(2-benzoxazolyl)thio-1,2,3,-triazolo[4,5,-d]pyrimidine (VAS2870) in vascular smooth muscle cells.252 The pre-treatment of smooth muscle cells with VAS2870 completely abolished NOX activity and platelet-derived growth factor-dependent intracellular ROS production.252 Furthermore, VAS2870 treatment inhibited ROS production and restored endothelium-dependent aorta relaxation in spontaneously hypertensive rats.253 Pyrazolopyridine derivatives, such as GK-136901, which are structurally related to VAS2870, were recently identified as potent inhibitors of NOX1 and NOX4.254 Although the mechanisms underlying the effects of these compounds have not been deciphered, the structural resemblance to NADPH suggests that these inhibitors might act as competitive substrates.255

Peptide inhibitors have many benefits over other oxidase inhibitors, such as good tissue penetration, a high degree of purity, low toxicity of degradation products and well-developed strategies for the synthesis of inhibitors with domain selectivity.256 However, the greatest challenge is to design peptides that specifically target individual NOX isoforms. Peptides corresponding to domains in the oxidase components involved in NOX assembly, such as NOX2, p22phox, p47phox and Rac, are inhibitory when added prior to complex assembly.256 Small peptides of 7–20 amino acid residues, designed to bind natural whole protein targets, can serve as inhibitors through the inhibition of intermolecular or intramolecular protein–protein or protein–lipid interactions during the assembly of the oxidase complex through competitive mechanisms.257 Two such NOX2 peptides, spanning 559–565 and 78–94 amino acids have been examined.258,259 Furthermore, NOX2 peptide 86–94 possesses a NOX2 B loop sequence essential for the activity and translocation of cytosolic components.260,261 NOX2 peptide 86–94 has been well studied and demonstrated as an oxidase inhibitor in cells, organs and whole animals. Endogenous proline-arginine (PR)-rich antibacterial peptide (PR39) is another peptide inhibitor produced in neutrophils, which blocks interactions between the Src homology 3 domain of the p47phox subunit and proline-rich regions and inhibits NOX.262,263,264

The catalytic subunit of NOX differs between each NOX isoform. Therefore, NOX1 and NOX2 are the best candidates for drug targeting to achieve isoform selectivity.255 However, the functional domains of the different NOX catalytic subunits are highly conserved, which prevents selective pharmacological targeting.81 For example, diphenyleneiodonium, which acts on the electron transport chain and prevents electron flow through interactions with FAD, does not discriminate between NOXs and other FAD-containing enzymes, including NOS, xanthine oxidase and cytochrome P450.255,265,266 Thus, this compound inhibits all NOX and Duox isoforms at low micromolecular concentrations.267

Due to cytosolic and membrane-associated components, the optimal functioning of NOX depends on post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation and lipidation. Compactin and lovastatin block NOX activation through the inhibition of post-translational Rac1 isoprenylation. Studies using differentiated HL-60 cells have shown that lovastatin and compactin-sensitive components of NOX localize to the cytosolic fraction. These effects were reversed upon the administration of rRac1 to the system.268 Gliotoxin (mycotoxin), produced in A. fumigatus, significantly inhibits PMA-induced O2 generation in PMNs,269 reflecting a reduction in the phosphorylation and incorporation of p47phox into the cytoskeleton. Gliotoxin also inhibits the membrane translocation of p67phox, p47phox and p40phox; however, there are no reports regarding the inhibition of Rac2 using this compound. The SUMO-1 and SUMO-specific conjugating enzyme, UBC-9, also significantly suppresses the activity of several NOX isoforms.268 The irreversible serine protease inhibitor, 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride, reduces the production of ROS through the inhibition of NOX2 assembly with p47phox in both intact, stimulated macrophages and cell-free systems.270 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride interferes with the activation of NOX, but not with electron flow. NOX activation and electron flow are two separate steps in the NOX pathway, and the effect of 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride is likely mediated through the chemical modification of cytochrome b558.270,271

Taken together, these data suggest that NOX inhibitors might reduce ROS-mediated stress in various malfunctions and diseases; however, these compounds must first be assessed for safety, selectivity, toxicity, bioavailability and the absence of significant side effects.

Conclusions

The primary function of NOX proteins in the immune system is to produce a respiratory burst that facilitates the killing of bacteria and fungi. This function is underscored by the fact that people with an inherited deficiency in NOX2 develop CGD and are unable to fight off common infections. However, while NOX isoforms play important roles in immunity, the short-term or incomplete inhibition of this pathway could potentially have therapeutic effects without disabling antibactericidal activity. Considering that the currently available pharmacological and natural compounds targeting NOX show encouraging results against ROS production, these compounds might also be effective against tissue damage and inflammation.

Summary

ROS-mediated stress contributes to a number of diseases, including pneumonia, COPD, emphysema, and cardiovascular pathology. The activation of various PRRs, including TLRs and NLRs, leads to ROS production and inflammation, mediated through the NOX system. This system plays a significant role in the protection against both exogenous and endogenous pathogens, and excess ROS might cause tissue damage and many other diseases. Currently, researchers are focusing on various strategies to remove excess ROS, including the use of antioxidants and drugs that enhance endogenous antioxidants. One interesting approach is to block ROS production using either small molecules or peptide inhibitors, plant-based compounds or inhibitors of post-translational modifications. Therefore, it is important to fully characterize the mechanisms of ROS production and determine the effects of ROS in various tissues. Moreover, it is critical to understand the NOX system and the roles of other NOX family enzymes as major sources of ROS production at specific sites of injury/inflammation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through funding from the Flight Attendant Medical Research Award YCSA-123253, the National Institutes of Health (grant R15-1R15ES023151-01) and a SVM Corp LAV-3383 grant to SB.

References

- 1Smeyne M, Smeyne RJ. Glutathione metabolism and Parkinson's disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2013; 62: 13–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Aliev G, Priyadarshini M, Reddy VP, Grieg NH, Kaminsky Y, Cacabelos R et al. Oxidative stress mediated mitochondrial and vascular lesions as markers in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Curr Med Chem 2014; 21: 2208–2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Robert AM, Robert L. Xanthine oxido-reductase, free radicals and cardiovascular disease. A critical review. Pathol Oncol Res 2014; 20: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Deken XD, Corvilain B, Dumont JE, Miot F. Roles of DUOX-mediated hydrogen peroxide in metabolism, host defense, and signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014; 20: 2776–2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Xin G, Du J, Wang YT, Liang TT. Effect of oxidative stress on heme oxygenase-1 expression in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Exp Ther Med 2014; 7: 478–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Franchini AM, Hunt D, Melendez JA, Drake JR. FcgammaR-driven release of IL-6 by macrophages requires NOX2-dependent production of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 25098–25108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Cross AR, Segal AW. The NADPH oxidase of professional phagocytes—prototype of the NOX electron transport chain systems. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004; 1657: 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Touyz RM, Briones AM, Sedeek M, Burger D, Montezano AC. NOX isoforms and reactive oxygen species in vascular health. Mol Interv 2011; 11: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Winkelstein JA, Marino MC, Johnston RBJr, Boyle J, Curnutte J, Gallin JI et al. Chronic granulomatous disease. Report on a national registry of 368 patients. Medicine 2000; 79: 155–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Quie PG, White JG, Holmes B, Good RA. In vitro bactericidal capacity of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes: diminished activity in chronic granulomatous disease of childhood. J Clin Invest 1967; 46: 668–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Holmes B, Quie PG, Windhorst DB, Good RA. Fatal granulomatous disease of childhood. An inborn abnormality of phagocytic function. Lancet 1966; 1: 1225–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Bylund J, Goldblatt D, Speert DP. Chronic granulomatous disease: from genetic defect to clinical presentation. Adv Exp Med Biol 2005; 568: 67–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Quinn MT, Ammons MC, Deleo FR. The expanding role of NADPH oxidases in health and disease: no longer just agents of death and destruction. Clin Sci 2006; 111: 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Brandes RP, Kreuzer J. Vascular NADPH oxidases: molecular mechanisms of activation. Cardiovasc Res 2005; 65: 16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reactive oxygen species in vascular biology: implications in hypertension. Histochem Cell Biol 2004; 122: 339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Moncada S, Higgs EA. The discovery of nitric oxide and its role in vascular biology. Br J Pharmacol 2006; 147(Suppl 1): S193–S201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Cifuentes ME, Pagano PJ. Targeting reactive oxygen species in hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2006; 15: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Wilcox CS. Oxidative stress and nitric oxide deficiency in the kidney: a critical link to hypertension? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2005; 289: R913–R935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Wilcox CS. Redox regulation of the afferent arteriole and tubuloglomerular feedback. Acta Physiol Scand 2003; 179: 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Zou AP, Cowley AWJr. Reactive oxygen species and molecular regulation of renal oxygenation. Acta Physiol Scand 2003; 179: 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Juncos R, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Differential effects of superoxide on luminal and basolateral Na+/H+ exchange in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2006; 290: R79–R83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Hoidal JR, Brar SS, Sturrock AB, Sanders KA, Dinger B, Fidone S et al. The role of endogenous NADPH oxidases in airway and pulmonary vascular smooth muscle function. Antioxid Redox Signal 2003; 5: 751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Brar SS, Kennedy TP, Sturrock AB, Huecksteadt TP, Quinn MT, Murphy TM et al. NADPH oxidase promotes NF-kappaB activation and proliferation in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002; 282: L782–L795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Piao YJ, Seo YH, Hong F, Kim JH, Kim YJ, Kang MH et al. Nox 2 stimulates muscle differentiation via NF-kappaB/iNOS pathway. Free Radic Biol Med 2005; 38: 989–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Kojim S, Ikeda M, Shibukawa A, Kamikawa Y. Modification of 5-hydroxytryptophan-evoked 5-hydroxytryptamine formation of guinea pig colonic mucosa by reactive oxygen species. Jpn J Pharmacol 2002; 88: 114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Wang G, Anrather J, Huang J, Speth RC, Pickel VM, Iadecola C. NADPH oxidase contributes to angiotensin II signaling in the nucleus tractus solitarius. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 5516–5524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Erdos B, Broxson CS, King MA, Scarpace PJ, Tumer N. Acute pressor effect of central angiotensin II is mediated by NAD(P)H-oxidase-dependent production of superoxide in the hypothalamic cardiovascular regulatory nuclei. J Hypertens 2006; 24: 109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Mander PK, Jekabsone A, Brown GC. Microglia proliferation is regulated by hydrogen peroxide from NADPH oxidase. J Immunol 2006; 176:1046–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Sbarra AJ, Karnovsky ML. The biochemical basis of phagocytosis. I. Metabolic changes during the ingestion of particles by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Biol Chem 1959; 234: 1355–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Iyer GY, Islam MF, Quastel JH. Biochemical aspects of phagocytosis. Nature 1961; 192: 535–541. [Google Scholar]

- 31Rossi F, Zatti M. Biochemical aspects of phagocytosis in polymorphonuclear leucocytes. NADH and NADPH oxidation by the granules of resting and phagocytizing cells. Experientia 1964; 20: 21–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Babior BM, Kipnes RS, Curnutte JT. Biological defense mechanisms. The production by leukocytes of superoxide, a potential bactericidal agent. J Clin Invest 1973; 52: 741–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Segal AW, Jones OT. Novel cytochrome b system in phagocytic vacuoles of human granulocytes. Nature 1978; 276: 515–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Segal AW, Jones OT, Webster D, Allison AC. Absence of a newly described cytochrome b from neutrophils of patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Lancet 1978; 2: 446–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Teahan C, Rowe P, Parker P, Totty N, Segal AW. The X-linked chronic granulomatous disease gene codes for the beta-chain of cytochrome b-245. Nature 1987; 327: 720–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Dinauer MC, Orkin SH, Brown R, Jesaitis AJ, Parkos CA. The glycoprotein encoded by the X-linked chronic granulomatous disease locus is a component of the neutrophil cytochrome b complex. Nature 1987; 327: 717–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37Nunoi H, Rotrosen D, Gallin JI, Malech HL. Two forms of autosomal chronic granulomatous disease lack distinct neutrophil cytosol factors. Science 1988; 242: 1298–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38Volpp BD, Nauseef WM, Clark RA. Two cytosolic neutrophil oxidase components absent in autosomal chronic granulomatous disease. Science 1988; 242: 1295–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39Baehner RL, Gilman N, Karnovsky ML. Respiration and glucose oxidation in human and guinea pig leukocytes: comparative studies. J Clin Invest 1970; 49: 692–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40Babior BM. NADPH oxidase: an update. Blood 1999; 93: 1464–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41Touyz RM, Chen X, Tabet F, Yao G, He G, Quinn MT et al. Expression of a functionally active gp91phox-containing neutrophil-type NAD(P)H oxidase in smooth muscle cells from human resistance arteries: regulation by angiotensin II. Circ Res 2002; 90: 1205–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42Diebold BA, Bokoch GM. Molecular basis for Rac2 regulation of phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Nat Immunol 2001; 2: 211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43Grizot S, Faure J, Fieschi F, Vignais PV, Dagher MC, Pebay-Peyroula E. Crystal structure of the Rac1–RhoGDI complex involved in nadph oxidase activation. Biochemistry 2001; 40: 10007–10013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44Takahashi M, Dillon TJ, Liu C, Kariya Y, Wang Z, Stork PJ. Protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of Rap1 regulates its membrane localization and cell migration. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 27712–27723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45Heyworth PG, Knaus UG, Settleman J, Curnutte JT, Bokoch GM. Regulation of NADPH oxidase activity by Rac GTPase activating protein(s). Mol Biol Cell 1993; 4: 1217–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46Dusi S, Donini M, Rossi F. Mechanisms of NADPH oxidase activation: translocation of p40phox, Rac1 and Rac2 from the cytosol to the membranes in human neutrophils lacking p47phox or p67phox. Biochem J 1996; 314(Pt 2): 409–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47Flannagan RS, Cosio G, Grinstein S. Antimicrobial mechanisms of phagocytes and bacterial evasion strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009; 7: 355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48Abate C, Patel L, Rauscher FJ3rd, Curran T. Redox regulation of fos and jun DNA-binding activity in vitro. Science 1990; 249: 1157–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49Borregaard N, Heiple JM, Simons ER, Clark RA. Subcellular localization of the b-cytochrome component of the human neutrophil microbicidal oxidase: translocation during activation. J Cell Biol 1983; 97: 52–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50Huang J, Hitt ND, Kleinberg ME. Stoichiometry of p22-phox and gp91-phox in phagocyte cytochrome b558. Biochemistry 1995; 34: 16753–16757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51Groemping Y, Rittinger K. Activation and assembly of the NADPH oxidase: a structural perspective. Biochem J 2005; 386(Pt 3): 401–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52Nauseef WM. Assembly of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Histochem Cell Biol 2004; 122: 277–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53Sumimoto H, Miyano K, Takeya R. Molecular composition and regulation of the Nox family NAD(P)H oxidases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 338: 677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54Koga H, Terasawa H, Nunoi H, Takeshige K, Inagaki F, Sumimoto H. Tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) motifs of p67(phox) participate in interaction with the small GTPase Rac and activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 25051–25060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55Suh YA, Arnold RS, Lassegue B, Shi J, Xu X, Sorescu D et al. Cell transformation by the superoxide-generating oxidase Mox1. Nature 1999; 401: 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56Banfi B, Maturana A, Jaconi S, Arnaudeau S, Laforge T, Sinha B et al. A mammalian H+ channel generated through alternative splicing of the NADPH oxidase homolog NOH-1. Science 2000; 287: 138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57Hilenski LL, Clempus RE, Quinn MT, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Distinct subcellular localizations of Nox1 and Nox4 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004; 24: 677–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58Balamayooran G, Batra S, Theivanthiran B, Cai S, Pacher P, Jeyaseelan S. Intrapulmonary G-CSF rescues neutrophil recruitment to the lung and neutrophil release to blood in Gram-negative bacterial infection in MCP-1−/− mice. J Immunol 2012; 189: 5849–5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59Fukata M, Hernandez Y, Conduah D, Cohen J, Chen A, Breglio K et al. Innate immune signaling by Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) shapes the inflammatory microenvironment in colitis-associated tumors. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15: 997–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60Wada T, Furuichi K, Sakai N, Iwata Y, Yoshimoto K, Shimizu M et al. Up-regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in tubulointerstitial lesions of human diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 2000; 58: 1492–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61Szanto I, Rubbia-Brandt L, Kiss P, Steger K, Banfi B, Kovari E et al. Expression of NOX1, a superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase, in colon cancer and inflammatory bowel disease. J Pathol 2005; 207: 164–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62Banfi B, Clark RA, Steger K, Krause KH. Two novel proteins activate superoxide generation by the NADPH oxidase NOX1. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 3510–3513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63Cheng G, Lambeth JD. NOXO1, regulation of lipid binding, localization, and activation of Nox1 by the Phox homology (PX) domain. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 4737–4742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64Geiszt M, Lekstrom K, Witta J, Leto TL. Proteins homologous to p47phox and p67phox support superoxide production by NAD(P)H oxidase 1 in colon epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 20006–20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65Takeya R, Ueno N, Kami K, Taura M, Kohjima M, Izaki T et al. Novel human homologues of p47phox and p67phox participate in activation of superoxide-producing NADPH oxidases. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 25234–25246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66Ueyama T, Geiszt M, Leto TL. Involvement of Rac1 in activation of multicomponent Nox1- and Nox3-based NADPH oxidases. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26: 2160–2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67Kikuchi H, Hikage M, Miyashita H, Fukumoto M. NADPH oxidase subunit, gp91(phox) homologue, preferentially expressed in human colon epithelial cells. Gene 2000; 254: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68Miyano K, Ueno N, Takeya R, Sumimoto H. Direct involvement of the small GTPase Rac in activation of the superoxide-producing NADPH oxidase Nox1. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 21857–21868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69Park HS, Lee SH, Park D, Lee JS, Ryu SH, Lee WJ et al. Sequential activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, beta Pix, Rac1, and Nox1 in growth factor-induced production of H2O2. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 4384–4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70Ueno N, Takeya R, Miyano K, Kikuchi H, Sumimoto H. The NADPH oxidase Nox3 constitutively produces superoxide in a p22phox-dependent manner: its regulation by oxidase organizers and activators. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 23328–23339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71Kawahara T, Ritsick D, Cheng G, Lambeth JD. Point mutations in the proline-rich region of p22phox are dominant inhibitors of Nox1- and Nox2-dependent reactive oxygen generation. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 31859–31869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72Cheng G, Ritsick D, Lambeth JD. Nox3 regulation by NOXO1, p47phox, and p67phox. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 34250–34255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73Kiss PJ, Knisz J, Zhang Y, Baltrusaitis J, Sigmund CD, Thalmann R et al. Inactivation of NADPH oxidase organizer 1 results in severe imbalance. Curr Biol 2006; 16: 208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74Geiszt M, Kopp JB, Varnai P, Leto TL. Identification of renox, an NAD(P)H oxidase in kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 8010–8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75Ambasta RK, Kumar P, Griendling KK, Schmidt HH, Busse R, Brandes RP. Direct interaction of the novel Nox proteins with p22phox is required for the formation of a functionally active NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 45935–45941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76Martyn KD, Frederick LM, von Loehneysen K, Dinauer MC, Knaus UG. Functional analysis of Nox4 reveals unique characteristics compared to other NADPH oxidases. Cell Signall 2006; 18: 69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77Gorin Y, Ricono JM, Kim NH, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE. Nox4 mediates angiotensin II-induced activation of Akt/protein kinase B in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2003; 285: F219–F229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78Lyle AN, Deshpande NN, Taniyama Y, Seidel-Rogol B, Pounkova L, Du P et al. Poldip2, a novel regulator of Nox4 and cytoskeletal integrity in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 2009; 105: 249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 2007; 87: 245–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80Banfi B, Molnar G, Maturana A, Steger K, Hegedus B, Demaurex N et al. A Ca2+-activated NADPH oxidase in testis, spleen, and lymph nodes. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 37594–37601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81Cheng G, Cao Z, Xu X, van Meir EG, Lambeth JD. Homologs of gp91phox: cloning and tissue expression of Nox3, Nox4, and Nox5. Gene 2001; 269: 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82Banfi B, Tirone F, Durussel I, Knisz J, Moskwa P, Molnar GZ et al. Mechanism of Ca2+ activation of the NADPH oxidase 5 (NOX5). J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 18583–18591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83Fu X, Beer DG, Behar J, Wands J, Lambeth D, Cao W. cAMP-response element-binding protein mediates acid-induced NADPH oxidase NOX5-S expression in Barrett esophageal adenocarcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 20368–20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84Colas C, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Autocatalytic radical reactions in physiological prosthetic heme modification. Chem Rev 2003; 103: 2305–2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85Daiyasu H, Toh H. Molecular evolution of the myeloperoxidase family. J Mol Evol 2000; 51: 433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86Nauseef WM. Contributions of myeloperoxidase to proinflammatory events: more than an antimicrobial system. Int J Hematol 2001; 74: 125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87Dupuy C, Virion A, Ohayon R, Kaniewski J, Deme D, Pommier J. Mechanism of hydrogen peroxide formation catalyzed by NADPH oxidase in thyroid plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 1991; 266: 3739–3743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88De Deken X, Wang D, Dumont JE, Miot F. Characterization of ThOX proteins as components of the thyroid H2O2-generating system. Exp Cell Res 2002; 273: 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89Morand S, Chaaraoui M, Kaniewski J, Deme D, Ohayon R, Noel-Hudson MS et al. Effect of iodide on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity and Duox2 protein expression in isolated porcine thyroid follicles. Endocrinology 2003; 144: 1241–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]