Abstract

Objectives

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as a multisystemic disease has a measurable and biologically explainable impact on the auditory function detectable in the laboratory. This study tries to clarify if COPD is also a significant and clinically relevant risk factor for hearing impairment detectable in the general practice setting.

Design

Retrospective matched cohort study with selection of patients diagnosed with COPD.

Setting

12 general practices in Lower Austria.

Participants

Consecutive patients >35 years with a diagnosis of COPD who consulted 1 of 12 single-handed GPs in 2009 and 2010 were asked to participate. Those who agreed were individually 1:1 matched with controls according to age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease and chronic heart failure.

Main outcome measures

Sensorineural hearing impairment as assessed by pure tone audiometry, answers of three questions concerning a self-perceived hearing problem, application of the whispered voice test and the score of the Hearing Inventory for the Elderly, Screening Version (HHIE-S).

Results

194 patients (97 pairs of 194 cases and controls) with a mean age of 65.5 (SD 10.2) were tested. Univariate conditional logistic regression resulted in significant differences in the mean bone conduction hearing loss and in the total score of HHIE-S, in the multiple conditional regression model, only smoking (p<0.0001) remained significant.

Conclusions

The results of this study do not support the hypothesis that there is an association between COPD and hearing impairment which, if found, would have allowed better management of patients with COPD.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Hearing impairment, General Practice

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A key strength of this study lies in the recruitment of regular patients and controls in primary healthcare, considering major clinically relevant comorbidities and increasing statistical power by an individual 1:1 matching as well as by using questions and tests that could be integrated in the daily work of general practices.

Limitations of our study include the selection process of the 12 participating general practitioners who were recruited at various continuing medical education activities, the small number of practices, the over-representation of males in the study group, as well as a relatively low number of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease COPD stage III/IV.

Introduction

There is increasing evidence that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as a multisystemic disease has a significant number of comorbidities.1–3 COPD can also directly affect some organ systems including the central nervous system. In patients with severe COPD, a significant decline of the overall cognitive function and especially of the verbal memory can be observed.4

Special research has also been done on the impact of COPD and chronic hypoxaemia on the auditory function of these patients. Laboratory results showed a statistically significant difference for all auditory measures between patients with COPD and controls, but in general hearing impairment to date was not shown to be clinically relevant in patients with COPD.5 6 Also in stable patients with COPD and mild-to-moderate airflow obstruction, subclinical abnormalities of brainstem auditory evoked potentials have been observed.7 It remains unclear if these results would have any clinical relevance for unselected patients with COPD in all stages in the general practice setting.8 Other chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes or cardiovascular disease, which have been shown to deteriorate hearing as well, are frequently met in patients with COPD, making it difficult to judge the role of COPD.9–12 Therefore, an individual matching of patients suffering from COPD versus controls in the general practice setting was regarded to be most appropriate to answer the research question whether COPD is a significant and relevant risk factor for a hearing disorder to be considered in primary care.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study is a comparison of individually 1:1 matched patients suffering from COPD to comparable controls according to age and sex without COPD, but alike comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease and chronic heart failure. The aim of this study is to evaluate whether COPD is a clinically relevant risk factor for hearing impairment. The presence of a hearing impairment was detected by questions and tests applicable in general practice.

The main outcome measure is a sensorineural hearing impairment as assessed in bone conduction by pure tone audiometry (PTA) on the better ear using the average of the frequencies 0.5, 1 and 2 kHz. Secondary outcome measures are the results of the whispering voice test (WVT), the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly Screening Version (HHIE-S) (see online supplementary files 1 and 2) and the answer to three questions concerning self-perceived hearing problems.

Selection of patients with COPD and controls

Included were consecutive patients diagnosed in general practice with COPD stages I–IV (ICD 10: J44.0, J44.1, J44.8, J44.9; ICPC 2: R95) and suitable controls with a minimum age of 35 years recruited by 12 general practitioners (GPs) from their own practices in the province of Lower Austria in the years 2009 and 2010. The GPs were approached by the authors at various continuing medical education activities and asked to participate. The recruitment of patients and controls took place in all 12 surgeries until a statistically sufficient number of 97 cases (clearly surpassing the required minimum of 60) was reached. COPD cases were selected in the order they came to get their regular (not only COPD-specific) prescriptions. Matching controls from the same 12 surgeries were selected by searching the electronic records and randomly allocated to COPD cases. Of the 100 recruited patients with COPD, 3 refused to participate, so finally 97 patients and 97 controls could be included. The diagnosis of COPD required the fulfilling of the GOLD criteria and the affirmation of the diagnosis by a pulmonary physician documented in the electronic record of the participating GP.13 14 Excluded were bedridden patients and patients unable to give their consent (eg, patients with dementia). Controls were matched 1:1 according to age group (range 5 years), sex and the presence of diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease and chronic heart failure.

Additionally, all participants were tested by a mobile research team in the respective practice offices using spirometry, audiometry and a questionnaire to assess the actual pulmonary function of patients with COPD, to assure a normal lung function of controls, to assess a possible hearing impairment by bone-conduction and air-conduction PTA and to investigate the impact of a hearing impairment on social life as measured by HHIE-S.

All participants were clinically stable at the time of testing and used their standard medication. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Lower Austria. All participants provided written informed consent. Neither the participating GPs nor the tested participants received financial remuneration for their participation.

Spirometry

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and the FEV1/FVC ratio were determined (Spirolab III spirometer; Medical International Research (MIR); Rome, Italy). Spirometries were performed by a medical assistant with operating experience over several years. In addition, an extra preparatory training of 3 h was given to consider various aspects of the specific study situation.

Audiometry

The primary outcome measure was a hearing loss in bone conduction assessed by PTA (ST 20 KL audiometer; MAICO Diagnostic GmbH; Berlin, Germany) on the better ear using the frequencies 0.5, 1 and 2 kHz. According to a broadly accepted definition of a sensorineural hearing impairment, the average of the hearing loss at the frequencies of 0.5, 1 and 2 kHz in the better ear was calculated.15 It was also recorded if the patient had a hearing loss exceeding 40 dB at the frequencies of 1 or 2 kHz in both ears or at 1 and 2 kHz in one ear according to the definition of a relevant hearing impairment given by Ventry and Weinstein.16

Additional questions, testing and application of the HHIE-S questionnaire

The patients were asked three questions concerning problems with hearing in general or in a face-to-face or group conversation.17 18 We then applied the WVT,19 20 and asked the patient to complete the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly, Screening version questionnaire (HHIE-S)21 22 in a validated German language version.23

Protocol

Patients with COPD and controls were asked to come to the surgery of their GP in the morning of the study day and to take their usual medication. After being informed about the aim of the study and procedures, patients with COPD and controls were asked to sign an informed consent form. Then the demographic and baseline characteristics of the patient with COPD or the control were recorded. This was followed by an inspection of the outer ear canal for a possible obstruction due to ear wax or other abnormalities of the ear canal or eardrum (eg, perforation). Subsequently, the three aforementioned questions concerning a self-perceived hearing disorder were asked, followed by a filling in of the HHIE-S questionnaire and performing the WVT. WVT is an easily applicable screening test for hearing impairment in general medicine. In short: The examiner stands arm’s length (0.6 m) behind the seated person and whispers a combination of numbers and letters (eg, 4-K-2) and then asks the patient to repeat the sequence. Each ear is tested separately and the test can be repeated once with a different combination of three numbers/letters. The test is passed if at least three out of a possible six numbers/letters are repeated correctly.

Afterwards, the patient was tested by pure-tone audiometry to detect a hearing loss in air or bone conduction.

Finally, the lung function of patients with COPD and of the controls was tested by spirometry. The whole testing procedure lasted between 25 and 30 min.

All testing was done by the research team consisting of one GP and one practice assistant in the absence of the patient’s own GP.

In addition to the demographic and baseline characteristics, the research team recorded the smoking status, an occupational exposure to noise, the body mass index, the O2 saturation and the pCO2 of the patients with COPD measured in the practice office of the lung specialist within the past 2 years, the usage of a long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) and the diagnosis of a depression (F32) as defined by ICD-10, as there is strong evidence for a high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disorders as well as for its significant association with subsequent all-cause mortality.

Statistical analysis

The data were recorded and analysed using Epi Info, V.3.2.2, CDC, Atlanta, Minitab 17 and the R Language and Environment for Statistical Computing and Graphics, V.2.9. Standard methods are used for the description of the data (frequencies and percentages for categorical data, mean and SD for continuous data). Differences and correlations between groups were calculated by paired t test, χ2 test, analysis of variance(ANOVA), Pearson’s correlation coefficient and linear regression. Univariate conditional logistic regression analysis for the healthy group and the COPD group was computed for the hearing impairment variables controlling for matching variable age. All other matching variables were perfectly matched and were thus not included in the model. p Values, ORs and the corresponding 95% CIs are reported. Multiple conditional logistic regression analyses were performed for the significant variables.

A p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Sample size calculation

Previous audiometries in patients without COPD which were performed due to other reasons resulted in a mean hearing loss of 12.5 dB (SD 11.3). Using a paired t test with a significance level of 0.05 (α) to detect a hearing loss of 18.5 dB in the COPD group compared to 12.5 dB in the control group, assuming an SD of 11.3 dB for both groups, resulted in a total number of 120 (cases and controls) with a statistical power of 80%. The total number of participants in the present study is 194 and clearly surpasses the required minimum. As patients with COPD were matched to controls with regard to age, sex and significant comorbidities, a higher statistical power can be expected.

Results

Demographic parameters and proportions of relevant comorbidities of the 12 participating surgeries as well as demographic data of the Austrian population are listed in table 1. The participating surgeries show a good comparability in all demographic parameters and the proportion of comorbidities used for matching. It is of interest that the mean age of males and females 35> years in the surrounding health districts is 59.4 years, whereas the mean age of COPD cases and controls in the investigated surgeries is 65.5 years, which parallels the higher global mean age of 49.6 years found in surgery patients, in comparison to the mean age of 41.4 years in the Austrian population, pointing in the direction of a higher mean age in the investigated surgeries.24 It is of further interest that the overall prevalence of COPD in our study population was as low as 4.5%, which is in accordance with the results of the Austrian data of the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study in which a doctor-diagnosed COPD was found in only 5.6% in the general population.25

Table 1.

Demographic parameters and proportions of relevant comorbidities in 12 participating surgeries and demographic data of the Austrian population

| Mean number (N) of patients/surgery/year | N=1967 (SD 373) |

| Mean age (years) of patients visiting surgeries | 49.6 years (SD 3.2) |

| Distribution between the sexes (%) in surgeries | 45.3% males 54.7% females (SD 3.8) |

| Average proportion (%) of COPD cases in surgeries | 4.5% (SD 2.3) |

| Distribution between the sexes (%) in COPD cases in surgeries | 55% males 45% females (SD 3.8) |

| Average proportion (%) of diabetes cases in surgeries | 8.5% (SD 2.8) |

| Average proportion (%) of hypertension cases in surgeries | 23.2% (SD 3.9) |

| Average proportion (%) of coronary heart disease cases in surgeries | 5.7% (SD 1.3) |

| Average proportion (%) of chronic heart failure cases in surgeries | 2.5% (SD 1.1) |

| Mean age of the whole population of Austria 2010 | 41.4 years |

| Distribution between the sexes (%) in Austria 2010 | 49% males, 51% females |

| Mean age of males and females >35 years in surrounding health districts | 59.4 years |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

A total of 194 study participants (97 cases and 97 controls) (144 males; 50 females) with a mean age of 65.5 (SD 10.2) years were tested. Ages ranged from 36 to 91 years. Participants’ baseline data of cases and controls are listed in table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline data of participants with COPD and controls (matched according to age, sex, hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes and chronic heart failure)

| Baseline personal data | Participants with COPD (n=97) | Controls (n=97) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age | 65.5 (10.1) | 65.4 (10.4) |

| Women, N (%) | 25 (25.8) | 25 (25.8) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 54 (55.7) | 54 (55.7) |

| Coronary heart disease, N (%) | 18 (18.6) | 18 (18.6) |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 15 (15.5) | 15 (15.5) |

| Chronic heart failure, N (%) | 12 (12.5) | 12 (12.5) |

| Smoking, N (%) | 74 (76.2) | 34 (35.1) |

| Mean (SD) of BMI | 29.6 (SD 5.5) | 28.9 (SD4.3) |

| Mean duration of COPD (years) | 10.2 (SD 6.9) | |

| LTOT, N (%) | 11 (11.3) | |

| Mean (SD) PaO2 (mm Hg)* | 64.5 (9.3) | |

| Mean (SD) PaCO2 (mm Hg)* | 39.8 (7.0) | |

| Mean FEV1(SD) (percentage of predicted value) | 58 (19.8) | 86 (19.5) |

| Depression, N (%) | 25 (25.8) | 10 (10.3) |

*PO2 and pCO2 values were available in only 64% of the participants with COPD.

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; LTOT, long-term oxygen therapy.

COPD prevailed in men, as only one quarter of cases and controls were females, a finding which is only partly explainable by the distribution between the sexes (55% males in COPD cases) found in the surgeries and which is only partly supported by the literature.26 27 The most frequent comorbidity was hypertension with more than a half of the cases, followed by coronary heart disease, diabetes and chronic heart failure, all in the range from 18% to 12%. As expected from epidemiological data, the portion of smokers in the COPD group exceeded three quarters.28 11 cases (11.3%) of patients with COPD needed LTOT, two belonging to the COPD III stage and nine to the COPD IV stage. The mean pO2 and pCO2 values were 64.5 mm Hg (SD 9.3) and 39.8 mm Hg (SD 7.0), respectively, values which reflect a stable and controlled clinical condition of patients with COPD typical for primary care, which in accordance with the literature does not cause a significant impact on the cognitive function of patients with COPD.29 As expected, the mean percentage of FEV1 (58% of predicted value) was markedly reduced in patients with COPD and in accordance with the fact that the majority of them belonged to COPD stage II (FEV 50–80%). 25.8% of participants suffering from COPD and 10.3% of controls had a diagnosis of a depression in the electronic health record of the GP.30–32

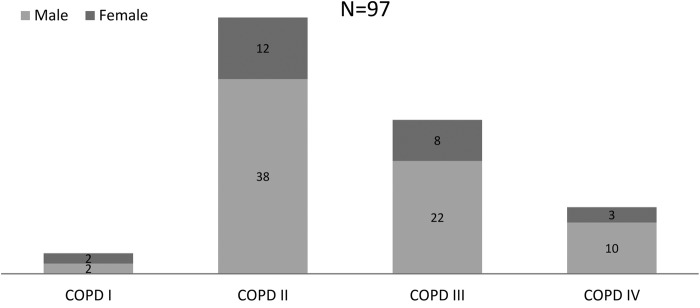

Figure 1 shows the distribution of male and female COPD cases according to different stages with the majority of cases belonging to stage II. This distribution differs from the published national Austrian and international data of the general population investigated by the BOLD study which found a percentage of 34% of COPD II and 61% of COPD stage I.25 33 No significant differences in the mean hearing loss between the different COPD stages I–IV were detectable by ANOVA (p value=0.7).

Figure 1.

Distribution of COPD stages I–IV in males and females. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

By testing the age cohort—correlation of hearing loss in the COPD and control groups, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficients of medium strength (0.56, 0.61, p value<0.001) in the COPD and control groups, respectively. In addition, we investigated the age-dependency of hearing loss in the COPD and control groups by linear regression. A very similar rise in hearing loss with increasing age was found in the COPD (coefficient 0.78) and control groups (coefficient 0.80), but differing constant terms in the COPD (−23.58) and control groups (−28.77) indicates a tendency towards an overall higher hearing loss in the COPD group (all p values<0.001).

Testing for the main outcome measure by t test resulted in a significant difference in the mean bone conduction hearing loss in the PTA as well as in the score of the HHIE-S questionnaire (tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

t Test (for paired data) for a difference in mean bone conduction hearing loss (better ear) in COPD cases and controls

| COPD cases and controls tested by PTA | Mean bone conduction hearing loss (better ear) in dB |

|---|---|

| COPD cases N=97 | 27.9 (SD 14.2)* |

| Controls N=97 | 23.7 (SD 13.5) |

*Significant difference p=0.006.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PTA, pure tone audiometry.

Table 4.

t Test (for paired data) for a difference in the HHIE-S total score in COPD cases and controls

| COPD cases and controls tested with HHIE-S | HHIE-S total score |

|---|---|

| COPD cases N=97 | 7.79 (SD 8.56)* |

| Controls N=97 | 5.53 (SD 8.08) |

*Significant difference p=0.036.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HHIE-S, Hearing Inventory for the Elderly, Screening Version.

We also assessed the medication of commonly prescribed drugs known to cause a hearing impairment34 like ACE inhibitors, AT2-receptor- antagonists, furosemid, torasemid, xipamid, NSRAs and ASA, opioids, chloroquine and a history of chemotherapy by using a χ2 test which resulted in non-significant ORs in COPD cases and matched controls. The prescription of antibiotics could not be investigated reliably from the EHRs of the GPs due to the high probability of a short time prescription by other physicians without recalling this by the patient, leading to a considerable information bias.

To evaluate the influence of other variables on the observed differences of mean bone conduction hearing loss and the HHIE-S total score, a univariate conditional logistic regression analysis was performed.

Table 5 shows the results for the hearing variables, occupational noise exposure, smoking and depression controlling for age. Significant differences in the hearing parameters between COPD cases and controls were only observed in the mean value of the (sensorineural) hearing loss at the frequencies of 0.5, 1 and 2 kHz in the bone conduction of the better ear (p=0.0098) and in the total score of HHIE-S (p=0.043).

Table 5.

Univariate conditional logistic regression analysis for hearing impairment variables, occupational noise exposure, BMI, smoking and depression in COPD cases and controls controlling for age

| p Value | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing problems in general | 0.34 | 0.85 (0.51 to 1.19) |

| Difficulties in a face-to-face conversation | 0.20 | 1.45 (0.88 to 2.02) |

| Difficulties in a group conversation | 0.17 | 1.38 (0.92 to 1.84) |

| Whispering voice test | 0.84 | 1.08 (0.37 to 1.79) |

| Mean air conduction hearing loss (better ear) | 0.39 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) |

| Mean bone conduction hearing loss (better ear) | 0.0098 | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.07) |

| Mean sound conduction loss* | 0.08 | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.06) |

| HHIE-S total score | 0.0432 | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.08) |

| Hearing loss ≥40 dB at 1 or 2 kHz in both ears | 0.51 | 1.34 (0.47 to 2.20) |

| Hearing loss ≥40 dB at 1 and 2 kHz in one ear | 0.82 | 1.12 (0.16 to 2.07) |

| Sensorineural hearing loss (better ear) ≥25 dB† | 0.16 | 1.67 (0.95 to 2.38) |

| Occupational noise exposure | 0.81 | 1.04 (0.71 to 1.38) |

| BMI | 0.40 | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.08) |

| Smoking | <0.0001 | 10.15 (9.19 to 11.11) |

| Depression | 0.010 | 2.87 (2.07 to 3.68) |

*Sound conduction loss means the difference between hearing loss in bone and air conduction.

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HHIE-S, Hearing Inventory for the Elderly, Screening Version.

†A hearing loss in the bone conduction of at least 25 dB is considered as moderate hearing impairment.

The result of the multiple conditional logistic regression for the significant variables shows that smoking (OR 9.72, 95% CI 3.62 to 26.05, p<0.0001) remained a significant factor, but that the mean value of the hearing loss at the frequencies of 0.5, 1 and 2 kHz in the bone conduction of the better ear turned out to be non-significant (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.07, p<0.23) and that depression (OR 2.44, 95% CI 0.88 to 6.78, p=0.09) and the HHIE-S total score (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.06, p=0.72) lost its significance as well.

Discussion

The results of this study do not support the hypothesis that there is a clinically relevant difference in the hearing performance of patients with COPD which can be measured with practicable tools for use in general medical practice. This was assessed by pure tone bone-conduction and air-conduction audiometry (PTA), the WVT, the application of HHIE-S and by asking three questions concerning a self- perceived hearing disorder. Therefore, routine diagnostic testing for hearing impairment of elderly patients with COPD do not provide benefits which go beyond possible benefits of screening for hearing loss in the general population in elderly patients.35 However, our study confirmed findings of other authors that cigarette smoking is a significant risk factor for hearing loss.36 As known in other epidemiological studies and in accordance with the literature, we could observe significantly more cases of depression in patients suffering from COPD when applying univariate logistic regression analysis.3 30 32 37 Since patients were matched with respect to other common chronic diseases known to be risk factors for a depression (eg, diabetes), the magnitude of association between COPD and depression could have been weakened.38 39

Though we found a small but significant difference in the mean hearing loss in bone conduction as well as in the HHIE-S total score, further analysis using multiple conditional logistic regression analysis for the significant variables, however, resulted in a loss of significance of the HHIE-S score and mean hearing loss in bone conduction, so only smoking retained its significance as a risk factor in COPD patients.

One reason to initiate this study was our clinical impression that patients with COPD more often show a hearing impairment. Although there is evidence from specialised research in auditory laboratories that COPD and chronic hypoxaemia have a measurable impact on the auditory function of patients suffering from COPD concerning significant differences for all auditory measures,5–7 clinically relevant differences between an individually matched group of patients with COPD and controls with the same relevant comorbidities in the general practice setting of this study are not detectable. The lack of differences in the mean hearing loss between different COPD stages can possibly be explained by the high number of cases with a near-normal pO2, by an individually different susceptibility to a low pO2 and by the difficulty of judging the influence of LTOT.

Besides all considerations on hearing impairment, the study confirmed the correlation of COPD and smoking, as we detected a much larger number of smokers in the COPD group.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first matched cohort study to investigate the role of COPD as a possible risk factor for hearing impairment which was performed in comparable average general practices using individual matching to increase the statistical power. The strength of our study lies in the recruitment of regular patients and controls in primary healthcare, considering major clinically relevant comorbidities by matching. Although the study needed extra time, it is shown that the questions and tests used in the study could be integrated in the daily work of average general practices. By these measures, we were able to clarify that COPD is not a significant risk factor for a clinically relevant hearing impairment in the general practice setting.

There are some limitations in our study, especially concerning the selection process of the 12 participating GPs who were recruited at various continuing medical education activities.

Since only one quarter of the study population were females, a selection bias cannot be excluded, although an inquiry at the biggest health insurance company of Lower Austria (covering approximately 63% of all insured) concerning the prescription of COPD-specific anticholinergic drugs (ATC R03BB) revealed significantly more prescriptions in males (OR m/f:1.59, CI 1.55 to 1.64, p<0.0001) (MS, personal communication, 2015). Also, since there is evidence in the literature that women may be more vulnerable to smoking, the results of our study could underestimate the influence of COPD on hearing impairment in women.40

We could test patients and controls in only a relatively small number of practices in just two health districts of Lower Austria which impairs the generalisation of our findings.

The testing was not done blinded, as the mobile testing team knew if the patient suffered from COPD or not. Since the majority of our cases belonged to the COPD II group, the chronic hypoxia was perhaps not severe enough to cause a pronounced and clinically meaningful effect on the inner ear, leading to a more conservative estimate of the differences.6

Implication for clinical practice and public health

Though COPD is a chronic disease affecting various organ systems and also causing a significant influence on the auditory function, the clinical relevance in the primary care setting is not given. We therefore cannot recommend a special screening for hearing impairment in elderly patients with COPD.

Unanswered questions and future research

Since the number of COPD GOLD III/IV cases with and without LTOT was low in our study, the possibility of a clinically relevant hearing impairment in this group of patients cannot be excluded. To overcome the study’s limitations concerning the low number of COPD stage III/IV cases, the low number of practices as well as the over-representation of women, the study should be re-performed with a larger set of COPD GOLD III/IV patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mag. Manfred Hinteregger, member of the Austrian health and social insurance companies, for providing the literature on frequencies of COPD in Austria and Europe, and the staff of the NOEGKK (Lower Austrian area health insurance) for providing data on prescription frequencies of specific anticholinergic drugs used in COPD treatment in male and female patients (MS, personal communication, 2015).

Footnotes

Contributors: GK initiated the study and contributed to data acquisition; GK, WF and SZ contributed to the conception and design of the study; GK, AS and SZ did the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. WS was involved in developing the research questions and in analysing the data. He also contributed in drawing the scientific conclusions from the results and in writing the paper. JB contributed to the literature research and draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. GK and SZ had full access to the data of the study and take responsibility for their correctness and completeness. All authors made a significant contribution to the research and the development of the manuscript and approved the final version for publication. GK and SZ are the guarantors.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: ‘All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/downloads/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; GK reports grants for the “Karl Landsteiner Institute for Systematics in General Medicine” from Actavis, Novartis, Richter Pharma, Kwizda, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Merck, Menarini, NOEGAM (Lower Austrian Society for General Practice) and personal fees for reviews of the German translation of the EBM Guidelines for General Medicine (Editor: “Oesterreichischer Aerzteverlag)”; there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work’.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Lower Austria.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Baty F, Putora PM, Isenring B et al. Comorbidities and burden of COPD: a population based case-control study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e63285 10.1371/journal.pone.0063285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunik ME, Roundy K, Veazey C et al. Surprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disorders. Chest 2005;127:1205–11. 10.1378/chest.127.4.1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Voogd JN, Wempe JB, Koëter GH et al. Depressive symptoms as predictors of mortality in patients with COPD. Chest 2009;135:619–25. 10.1378/chest.08-0078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Incalzi RA, Gemma A, Marra C et al. Verbal memory impairment in COPD: its mechanisms and clinical relevance. Chest 1997;112:1506–13. 10.1378/chest.112.6.1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.el-Kady MA, Durrant JD, Tawfik S et al. Study of auditory function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Hear Res 2006;212:109–16. 10.1016/j.heares.2005.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atiş S, Ozge A, Sevim S. The brainstem auditory evoked potential abnormalities in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology 2001;6:225–9. 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2001.00337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta PP, Sood S, Atreja A et al. Evaluation of brain stem auditory evoked potentials in stable patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Thorac Med 2008;3:128–34. 10.4103/1817-1737.42271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine BA, Shelton C, Berliner KI et al. Sensorineural loss in chronic otitis media. Is it clinically significant? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1989;115:814–16. 10.1001/archotol.1989.01860310052021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Moraes Marchiori LL, de Almeida Rego Filho E, Matsuo T. Hypertension as a factor associated with hearing loss. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2006;72:533–40. 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31001-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bainbridge KE, Hoffman HJ, Cowie CC. Diabetes and hearing impairment in the United States: audiometric evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:1–10. 10.7326/0003-4819-149-1-200807010-00231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torre P III, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE et al. The association between cardiovascular disease and cochlear function in older adults. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2005;48:473–81. 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/032) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gates GA, Cobb JL, D'Agostino RB et al. The relation of hearing in the elderly to the presence of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993;119:156–61. 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880140038006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. http://www.thoracic.org/clinical/copd-guidelines/resources/copddoc.pdf.

- 14.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Updated 2013. http://www.goldcopd.org

- 15.Bagai A, Thavendiranathan P, Detsky AS. Does this patient have hearing impairment? JAMA 2006;295:416–28. 10.1001/jama.295.4.416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ventry IM, Weinstein BE. Identification of elderly people with hearing problems. ASHA 1983;25:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Schaik V, Hörchner C, Bartelink M et al. Value of a four-item questionnaire in the diagnosis of presbyacusis. Eur J Gen Pract 1997;3:62–4. 10.3109/13814789709160325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voeks SK, Gallagher CM, Langer EH et al. Self-reported hearing difficulty and audiometric thresholds in nursing home residents. J Fam Pract 1993;36:54–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macphee GJ, Crowther JA, McAlpine CH. A simple screening test for hearing impairment in elderly patients. Age Ageing 1988;17:347–51. 10.1093/ageing/17.5.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pirozzo S, Papinczak T, Glasziou P. Whispered voice test for screening for hearing impairment in adults and children: systematic review. BMJ 2003;327:967 10.1136/bmj.327.7421.967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lichtenstein MJ, Bess FH, Logan SA. Diagnostic performance of the hearing handicap inventory for the elderly (screening version) against differing definitions of hearing loss. Ear Hear 1988;9:208–11. 10.1097/00003446-198808000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtenstein MJ, Bess FH, Logan SA. Validation of screening tools for identifying hearing-impaired elderly in primary care. JAMA 1988;259:2875–8. 10.1001/jama.1988.03720190043029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuck AE, Kharicha K, Dapp U et al. Development, feasibility and performance of a health risk appraisal questionnaire for older persons. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:1 10.1186/1471-2288-7-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. http://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/bevoelkerung/bevoelkerungsstruktur/bevoelkerung_nach_alter_geschlecht/031395.html.

- 25.Schirnhofer L, Lamprecht B, Vollmer WM et al. COPD prevalence in Salzburg, Austria: results from the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) Study. Chest 2007;131:29–36. 10.1378/chest.06-0365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viegi G, Pistelli F, Sherrill DL et al. Definition, epidemiology and natural history of COPD. Eur Respir J 2007;30:993–1013. 10.1183/09031936.00082507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherrill DL, Lebowitz MD, Knudson RJ et al. Longitudinal methods for describing the relationship between pulmonary function, respiratory symptoms and smoking in elderly subjects: the Tucson Study. Eur Respir J 1993;6:342–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet 2009;374:733–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozora E, Filley CM, Julian LJ et al. Cognitive functioning in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and mild hypoxemia compared with patients with mild Alzheimer disease and normal controls. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1999;12:178–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleland JA, Lee AJ, Hall S. Associations of depression and anxiety with gender, age, health-related quality of life and symptoms in primary care COPD patients. Fam Pract 2007;24:217–23. 10.1093/fampra/cmm009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J 2009;33:1165–85. 10.1183/09031936.00128008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust 2009;190(7 Suppl):S54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet 2007;370:741–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cary R, Clarke S, Delic J. Effects of combined exposure to noise and toxic substances—critical review of the literature. Ann Occup Hyg 1997;41:455–65. 10.1016/S0003-4878(97)00006-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moyer VA, Force USPST. Screening for hearing loss in older adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:655–61. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Tweed TS et al. Prevalence of hearing loss in older adults in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. The Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. Am J Epidemiol 1998;148:879–86. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quint JK, Baghai-Ravary R, Donaldson GC et al. Relationship between depression and exacerbations in COPD. Eur Respir J 2008;32:53–60. 10.1183/09031936.00120107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer C, Vorderstrasse A, Weil A et al. Evaluation of a depression screening and treatment program in primary care for patients with diabetes mellitus: insights and future directions. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2015;27:131–6. 10.1002/2327-6924.12149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walters P, Barley EA, Mann A et al. Depression in primary care patients with coronary heart disease: baseline findings from the UPBEAT UK study. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e98342 10.1371/journal.pone.0098342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Connett JE, Murray RP, Buist AS et al. Changes in smoking status affect women more than men: results of the Lung Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:973–9. 10.1093/aje/kwg083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]