Abstract

Objective

To assess associations between secure patient–clinician email use and clinical services utilisation over time.

Design

Retrospective cohort study between July 2010 and December 2013. Controlling for a utilisation surge around first secure email use, we analysed difference of differences between propensity score-matched groups of secure patient–clinician email users and non-users for utilisation 1–12 months before and 7–18 months after first email (users) or a randomly assigned index date (non-users).

Setting

US integrated healthcare delivery system.

Participants

9345 adults with first secure email use between July 2011 and July 2012 and continuous enrolment for ≥30 months and 9345 adults without secure email use between July 2010 and July 2012 matched to users on demographics, health status, and baseline utilisation.

Primary Outcome Measures

Rates of office visits, patient-initiated phone calls, scheduled telephone visits, after-hours clinic visits, emergency department visits, and hospitalisations.

Results

After controlling for multiple factors, no statistically significant differences in utilisation between secure email users and non-users occurred. Utilisation transiently increased by 88–237% around first email use. Annual rates of patient-initiated phone calls decreased among secure email users, 0.2 fewer calls per person (95% CI −0.3 to −0.1), from a mean of 4.1 calls per person 1–12 months before first use to a mean of 3.8 calls per person 7–18 months after first use. Rates of patient-initiated phone calls also decreased among non-users, 0.1 fewer calls per person (95% CI −0.2 to 0.0), from a mean of 4.2 calls per person 1–12 months before the index date to mean of 4.1 calls per person 7–18 months after the index date.

Conclusions

Compared with non-users, patient use of secure email with clinicians was not associated with statistically significant differences in clinical services utilisation 7–18 months after first use.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study improved on previous methods by excluding data for 6 months after first secure email use, comprehensively adjusting for baseline utilisation, deriving propensity scores from a robust set of independent variables, and examining clinical services utilisation 7–18 months after the index date.

The population consisted of individuals who were late adopters of secure email use with clinicians and likely differed in systematic ways from those who opted for earlier use, which may limit the generalisability of the results.

This study focused on the use of secure e-mail between clinicians and patients, rather than the use of all patient portal functions.

Introduction

Under meaningful use requirements of the US Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009, patient portals are emerging as a key technology for engaging patients. In 2013, 40% of US physicians in ambulatory care settings had some type of patient portal.1 Patient portals tethered to electronic health records (EHRs) generally enable patients to communicate electronically and securely with healthcare clinicians, access their medical records, schedule appointments, pay bills, and refill prescriptions.2 Other functions typically include a problem list, list of medications, allergy list, test results, and links to personalised health information.3

A recent systematic review concluded that insufficient evidence existed that patient portals improve health outcomes, cost, or utilisation.4 However, it did not assess the impact of individual portal functions. Secure email communication between patients and clinicians via an online portal is a new care modality in which patients communicate clinical concerns and receive a reply.5 It is highly desirable to patients and holds the potential to improve healthcare quality and efficiency.6–10

To date, evidence about the association of secure patient–clinician email with utilisation of other clinical services is inconsistent. Patients and clinicians report time savings from avoided in-person visits and more efficient management of patient care and, conversely, some increased time demands on clinicians from using secure email with patients.11–14 A 2012 Cochrane review concluded that the effect of patient–clinician email on utilisation could not be assessed due to differing methodologies and measures, variable results, and missing data.5 Similarly, a 2014 systematic interpretive review concluded that heterogeneous reporting precluded assessing overall workload changes.15 Investigations of the association of secure patient–clinician email with utilisation of specific clinical services have most frequently examined telephone calls and office visits. In three reports, patients using secure email telephoned their clinicians at rates similar to those of patients in control or comparison groups; in a fourth study, increases over time in phone calls were smaller for patients using secure email than for non-users.16–19 Evidence regarding office visit utilisation is also mixed. In separate trials among patients with diabetes, a 10% increase in secure message threads was associated with a 1.25% increase in office visits, and the primary care visit rate was 32% higher among patients with at least 12 message threads per year.20 21 Secure email was also associated with decreased or unchanged rates of primary care office visits in three reports.19 22–24 Studies assessing other types of utilisation are rare. In a small trial among patients with congestive heart failure, secure patient–clinician email was associated with increased emergency department (ED) visits but unchanged hospitalisation rates.25

The aim of this study was to assess the association of secure patient–clinician email with utilisation of various clinical services over time. We hypothesised that: (1) patients who initiated secure e-mail with clinicians would use the same level of clinical services over the longer term that they did before using secure email; and (2) patients who initiated secure e-mail with clinicians would use the same level of clinical services as matched patients who did not use secure e-mail with clinicians.

Methods

The study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO), one of seven regions of Kaiser Permanente, among the largest not-for-profit integrated healthcare delivery systems in the USA, serving 10 million members. At KPCO, 1000 physicians and 6000 staff members provide care for 615 000 members at 28 medical offices. Inpatient care is provided through contracts with non-Kaiser Permanente hospitals. KPCO members represent a diverse racial/ethnic mix similar to that of the general population in the Denver metropolitan area, where Kaiser Permanente facilities are predominantly located. Members select KPCO as their healthcare provider in a number of ways. The Colorado Affordable Care Act Health Exchange, which is primarily for people without other health insurance options, includes KPCO membership as an option. Employers may offer KPCO membership as one of several options from which employees can select healthcare coverage. Government-subsidised programmes are available for individuals 65 years of age and those qualifying on the basis of low income. Patients may also privately purchase coverage, choosing from a variety of KPCO health plans that include a traditional health maintenance organisation plan and high-deductible cost sharing plans.

KP HealthConnect, KPCO's integrated EHR, was implemented in 2004. The patient portal, MyHealthManager (MHM), was implemented in 2006 and allows members to securely access parts of their medical record, such as test results, active medications, and care plans, and to schedule appointments, request prescription refills, and exchange secure email with healthcare clinicians. Members receive information about the patient portal and instructions for registering in multiple ways, including mailed materials, notices posted in KPCO clinics, and while checking in for clinic visits. All KPCO members aged 13 and above can register for an account. In 2012, 66% of KPCO members with internet access meeting the age requirement were registered for an account. Registered members can access all MHM functionalities. Although members may use any portal function after registering, we focused on patients initiating secure email communication with clinicians, in contrast to earlier evaluations at Kaiser Permanente that assessed the use of any portal function and yielded conflicting findings about the impact of use on clinical services utilisation.19 26

Although we did not assess the types of clinicians that patients emailed, secure messages are primarily delivered to the inboxes of physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners providing primary and specialty care. Clinicians may choose to respond directly to all patient email messages or to have a medical assistant or registered nurse on the care team review all incoming secure email from patients, respond to any requests or concerns within their scopes of practice, and forward the remainder of patient secure email messages to the clinician's attention.

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of secure patient–clinician email use and clinical services utilisation between July 2010 and December 2013. For study inclusion, members were required to be at least 18 years of age and continuously enrolled for at least 30 months with either first use of secure patient–clinician email between July 2011 and July 2012 or no use between July 2010 and July 2012. We did not assess the portal registration status of members with no secure email use. After excluding members in the top 1% of baseline utilisation, we separated the population into secure email users and non-users. To eliminate bias arising from seasonal variations in utilisation, we assigned each non-user a randomly selected index date between July 2011 and July 2012.

A spike in utilisation of clinical services occurs around the time of the first use of secure patient–clinician messaging or patient portal registration, which may be prompted by a new illness or medical concern.19 23 26 Previous studies excluded 1–2 months before and 1 month after the index date, and a recent study at Kaiser Permanente adjusted for baseline office visit utilisation in the year before the index date.19 23 26 We adjusted for the utilisation spike in two ways that substantially strengthened the study design. First, to eliminate its effect and focus on longer term effects, we excluded a period of 6 months after the index date. Thus, we assessed clinical utilisation from 1 to 12 months before the index date (the pre period) and from 7 to 18 months after the index date (the post period). Second, because variable baseline utilisation may reflect unmeasured differences between patients who do and do not use secure email with clinicians, we matched users and non-users on all baseline utilisation up to and including the index date. We collected data from the EHR and administrative databases on age, gender, benefit type, number of chronic illnesses, distance from the nearest medical office building, utilisation of office, after-hours clinic, and ED visits, patient-initiated and scheduled telephone calls, and inpatient admissions. We used DxCG risk scores (Verisk Health, Inc; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) to characterise illness severity. A commercial product, DxCG relative risk scores predict healthcare costs relative to the population mean, based on age, gender, diagnoses, and drug codes.27

Statistical analyses

We assessed differences between secure email users and non-users with Student t tests for DxCG risk scores and χ2 tests for categorical variables. To adjust for differences between users and non-users, we calculated propensity scores using a logistic regression model and a robust selection of independent variables to estimate the probability of secure email use. Independent variables included index month and year, age, gender, benefit type, DxCG risk score, number of chronic illnesses, distance from the nearest medical office building, and baseline utilisation of office, urgent care, and ED visits, patient-initiated and scheduled telephone calls, and inpatient admissions. Matching on baseline utilisation occurred in two steps. We first matched users and non-users on utilisation for the first 11 months of the pre period and then on utilisation for the month immediately before the index date. Finally, we created matched pairs of users and non-users whose individual propensity scores differed by 0.001 or less and assessed differences between the groups of matched users and non-users with Student t tests for DxCG risk scores and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

We calculated utilisation rates for clinical services and analysed difference of differences for utilisation before and after the index date using bootstrapping methods, comparing the matched groups of secure email users and non-users. Office visits and patient-initiated phone calls were reported as per member per year rates. Clinicians may schedule telephone visits to follow-up with members; these were reported as per 1000 members per year rates. After-hours clinic visits, ED visits, and hospitalisations occurred less frequently and were also reported as per 1000 members per year rates. All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute), with two-sided statistical tests and a 0.05 level of statistical significance.

Results

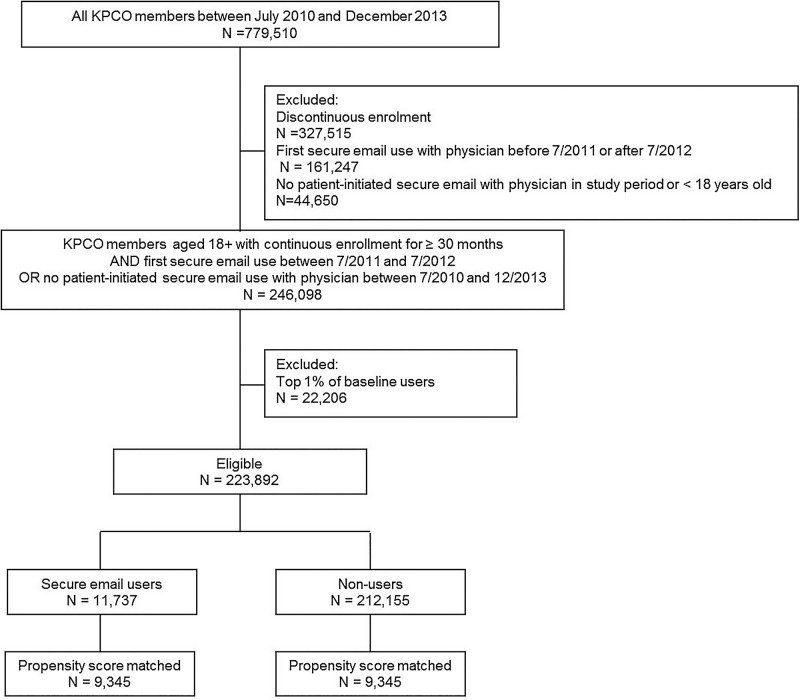

We identified 11 937 KPCO members aged 18 and above who were continuously enroled for at least 30 months and first used secure patient–clinician email between July 2011 and July 2012 and 212 155 members with the same age and enrolment characteristics but with no secure patient–clinician email use between July 2010 and December 2013 (figure 1). Applying propensity score matching, we refined the cohorts to include 9345 matched pairs of users and non-users, which we used to examine differences in clinical services utilisation associated with secure patient–clinician email use. After applying propensity score matching between secure email users and non-users, some statistically significant differences persisted related to age, type of insurance benefits, and baseline utilisation of telephone calls and scheduled telephone visits (table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants. Creation of propensity score-matched cohorts (KPCO, Kaiser Permanente Colorado).

Table 1.

Prematching and postmatching population characteristics

| Unmatched, N (%) |

Matched, N (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHM users (n=11 737) | Non-users (n=212 155) | p Value | MHM users (n=9345) | Non-users (n=9345) | p Value | |

| Age categories, years | <0.001 | <0.01 | ||||

| 18–19 | 283 (2.4) | 7494 (3.5) | 238 (2.5) | 244 (2.6) | ||

| 20–44 | 4750 (40.5) | 80 419 (37.9) | 3734 (40.0) | 3662 (39.2) | ||

| 45–64 | 4713 (40.2) | 81 156 (38.3) | 3741 (40.0) | 3710 (39.7) | ||

| ≥65 | 1991 (17.0) | 43 086 (20.3) | 1632 (17.5) | 1729 (18.5) | ||

| Sex | <0.001 | 0.63 | ||||

| Female | 6758 (57.6) | 108 360 (51.0) | 3896 (41.7) | 3861 (41.3) | ||

| Male | 4979 (42.4) | 103 795 (48.9) | 5449 (58.3) | 5484 (58.7) | ||

| Benefit type | <0.001 | <0.01 | ||||

| DHMO plan | 3751 (32.0) | 71 577 (33.7) | 3072 (32.9) | 2845 (30.4) | ||

| HMO plan | 5134 (43.8) | 80 928 (38.1) | 3974 (42.5) | 4086 (43.7) | ||

| Medicare | 1862 (15.9) | 37 790 (17.8) | 1532 (16.4) | 1618 (17.3) | ||

| Medicaid | 60 (0.5) | 3397 (1.6) | 48 (0.5) | 54 (0.6) | ||

| Other | 930 (7.9) | 18 463 (8.7) | 719 (7.7) | 742 (7.9) | ||

| DxCG score, mean | 1.75 | 1.85 | 0.002 | 1.79 | 1.82 | 0.39 |

| Number of chronic illnesses | <0.001 | 0.39 | ||||

| 0 | 10 288 (88.0) | 188 254 (88.7) | 7877 (86.8) | 8285 (86.2) | ||

| 1 | 1322 (11.3) | 21 367 (10.1) | 1096 (12.1) | 1207 (12.6) | ||

| 2 | 112 (10.0) | 2228 (1.1) | 90 (1.0) | 109 (1.1) | ||

| 3 | 15 (0.1) | 271 (0.1) | 13 (0.1) | 11 (0.1) | ||

| 4 | 0 (0.0) | 35 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | ||

| Distance to nearest medical office building, miles | <0.001 | 0.17 | ||||

| 0–4.9 | 8144 (69.4) | 143 368 (67.6) | 6154 (67.8) | 6639 (69.1) | ||

| 5–19.9 | 2954 (25.2) | 54 127 (25.5) | 2406 (26.5) | 2461 (25.6) | ||

| ≥20 | 639 (5.4) | 14 660 (6.9) | 516 (5.7) | 514 (5.3) | ||

| Annual utilisation, per member | ||||||

| Inpatient stays | 0.07 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.94 |

| ED visits | 0.13 | 0.11 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.23 |

| After-hours office visits | 0.08 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Low-acuity office visits | 0.24 | 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.88 |

| Low-acuity patient calls | 0.08 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.17 |

| Office visits | 3.27 | 2.18 | <0.001 | 3.30 | 3.28 | 0.69 |

| Patient calls | 3.83 | 3.03 | <0.001 | 3.83 | 4.07 | <0.01 |

| Scheduled telephone visits | 0.29 | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.03 |

DHMO, deductible health maintenance organisation; ED, emergency department; HMO, health maintenance organisation; MHM, MyHealthManager.

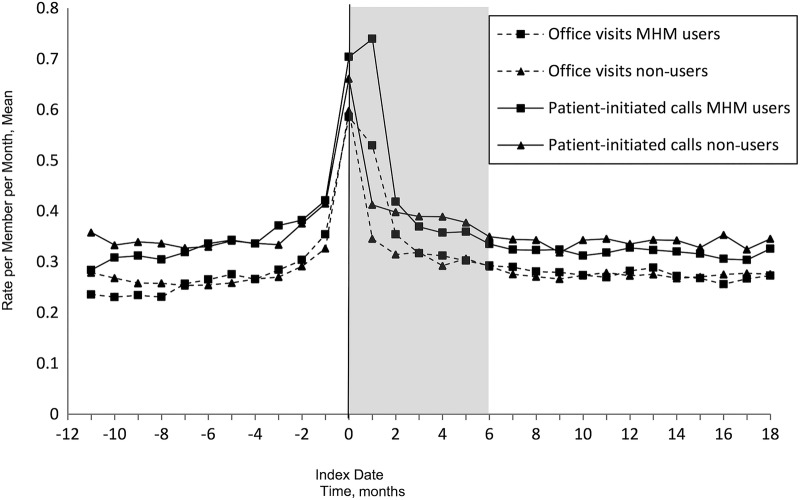

A pronounced surge in utilisation occurred around the time of first use of secure email. Peak utilisation occurred in the index month for all clinical services except patient-initiated and scheduled telephone calls, which peaked in the month following the index date. Across all services, the unweighted average relative increase in utilisation was 143%. Relative increases in monthly utilisation rates for specific clinical services ranged from 88% for after-hours clinic visits, an increase of 0.006 visits per member, from 0.006 in months 1–12 before the index date to 0.012 in the index month, to 238% for scheduled telephone visits, an increase of 0.55 visits per member, from 0.23 in months 1–12 before the index date to 0.78 per member in the month following the index date. The surge in utilisation largely dissipated by 6 months after the index date.

Only two statistically significant changes in utilisation occurred between the pre and post periods. Among secure email users, patient-initiated phone calls decreased by 0.2 calls per member per year (95% CI −0.3 to −0.1), from an annual mean of 4.1 patient-initiated calls per member 1–12 months before the index date to a mean of 3.8 calls per member 7–18 months after the index date. Patient-initiated phone calls also decreased among non-users by 0.1 calls per member (95% CI −0.2 to −0.0), from a mean of 4.2 patient-initiated phone calls per member 1–12 months before the index date to a mean of 4.1 calls per member 7–18 months after the index date. No other differences in utilisation before and after the index date within user and non-user groups were statistically significant (table 2).

Table 2.

Annual healthcare utilisation before and after the index date among secure patient–clinician email users and non-users

| MHM users |

MHM non-users |

Difference in differences (95% CI) | p Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | p Value | Before | After | p Value | |||

| Office visits* | 3.2 | 3.3 | 0.06 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0.57 | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.2) | 0.33 |

| Patient-initiated calls* | 4.1 | 3.8 | <0.0001 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 0.05 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.0) | 0.14 |

| Scheduled telephone visits† | 279.2 | 280.9 | 0.89 | 287.8 | 310.1 | 0.07 | 20.7 (−57.2 to 12.9) | 0.23 |

| After-hours office visits† | 77.0 | 81.6 | 0.37 | 72.8 | 74.1 | 0.76 | 3.3 (−11.2 to 15.1) | 0.62 |

| ED visits† | 130.2 | 127.6 | 0.69 | 131.4 | 134.5 | 0.63 | 5.6 (−21.6 to 12.0) | 0.53 |

| Inpatient stays† | 64.6 | 65.8 | 0.81 | 64.1 | 65.0 | 0.85 | 0.35 (−13.9 to 15.7) | 0.96 |

*Mean per member per year.

†Mean per 1000 members per year.

ED, emergency department; MHM, MyHealthManager.

When comparing changes between secure patient–clinician email users and non-users in clinical services utilisation before and after the index date, we found no statistically significant differences (table 2). Figure 2 depicts monthly mean rates for office visit and patient-initiated telephone calls. Similar figures for all types of utilisation are available online (see online supplementary figures S1 and figure S2).

Figure 2.

Matched cohort mean office visits and patient-initiated calls per month. Each data point represents mean office visits from the preceding month. The tinted area indicates the period from which data were excluded for the rates reported in table 2 (MHM, MyHealthManager).

Discussion

We had hypothesised that: (1) patients who initiated secure e-mail with clinicians would use the same level of clinical services over the longer term that they did before using secure email; and (2) patients who initiated secure e-mail with clinicians would use the same level of clinical services as matched patients who did not use secure e-mail with clinicians. Our hypothesis was confirmed. We observed no differences between patients who did and did not use secure patient clinician email in utilisation of office visits, scheduled telephone visits, patient-initiated phone calls, ED visits, after-hours clinic visits, and hospitalisations 7–18 months after the index date. Very small decreases in patient-initiated phone calls between the pre and post periods for secure email users and non-users were likely clinically meaningless, despite statistical significance.

Strengths of the study include adjustment for a utilisation spike around the index date by matching on all baseline utilisation data and excluding data for 6 months after the index date. The inclusion of a robust array of independent variables in the propensity score matching model is also a strength. Several limitations deserve mention. Although secure clinician–patient email had been available since 2006, we studied individuals who had not used secure email with clinicians after 1 (users) to 2 (non-users) years of membership. They comprised a minority population; in 2012, 66% of all eligible KPCO members were registered for the patient portal, and secure email is second only to viewing laboratory results in frequency of use by members. The members we included in our study likely differed in systematic ways from those who opted for earlier use, but the potential impact of these differences on our findings is unknown. We also lacked data on the volume of secure patient–clinician email messages among study participants. A study of proxy personal health record (PHR) use by caregivers of paediatric patients found that increased use of clinical services occurred only among those with the highest use.28 Finally, our study took place in an integrated care delivery system. The degree to which the findings are generalisable to other settings is unknown.

The present findings contrast with those of previous studies at Kaiser Permanente exploring the association of portal registration with the use of clinical services.19 26 Potential explanations for differing results include the likelihood that the association with utilisation of clinical services is different for secure patient–clinician email than for other portal functions. This explanation is supported by a recent report examining the association between secure patient–clinician email use and office visit rates, which found that the latter were unchanged.23 A previous study that found increased utilisation of clinical services after portal registration excluded a month before and after the index date, in comparison to the 6-month exclusion period used here.26 A shorter exclusion period likely captured some of the utilisation surge that, in the present study, abated by approximately 6 months after the index date. A second previous study at Kaiser Permanente examined associations between portal registration and clinical services utilisation among members who registered when overall portal registration rates were only 6%, finding that registration was associated with decreased rates of office visits and telephone contacts.19 As noted earlier, early and late adopters of portal use may differ from each other in ways that affect their patterns of clinical services use over time. Differences in this series of studies are summarised in online supplementary table S1.

The potential short-term and long-term impacts on workloads of the utilisation surge around the time of registration for clinician–patient email should be considered. The initial surge in utilisation of clinical services was followed by a return to utilisation levels similar to those of patients who did not securely email clinicians. Although we did not directly investigate the causes of the surge, we believe two types of utilisation surges may occur at the same time. First, when new individuals have a clinic visit, they are actively encouraged to also register for the patient portal and to communicate by secure email with clinicians. In this case, initial utilisation around first secure email use is due to how Kaiser Permanente promotes portal registration. Second, we also speculate that increased use of clinical services for this cohort of late-registrant patients signals acute and/or serious health event, such as acute illness or identification of a new medical condition. Such an event may prompt patients to increase many types of clinical utilisation and, for some, to also initiate secure email as a result of the need to interact more frequently with clinicians and staff members. Users and non-users were matched on baseline utilisation immediately before the index date, as well as for the preceding 11 months (figure 2, online supplementary figure S3). This suggests that the surge in utilisation of clinical services we observed may be an artefact of a natural association between a new health concern, increased utilisation, and, for some patients, portal registration and first secure email use.

In practical terms, the workload impact of surges in individual utilisation concomitant with new health events and first use of secure email is unlikely to be perceived by clinicians and organisations as distinct from expected demand for clinical services. However, in our experience, widespread use over time among patients of a portal offering secure email with clinicians is associated with an increase in secure email workload that must be taken into account. Unpublished KPCO data indicate that, on average, physicians with more than 500 patients send 6–7 emails to patients per day, spending 3–4 min on each email response; some of these emails may avert clinical services use, but many will not.

Further study is required to more fully understand the relationship between secure patient–clinician email use and clinical services utilisation. Applying the strengths of this study—the extended data exclusion period and the robust matching on baseline characteristics—to a population of earlier adopters would validate the findings. In a previous study, clinical services utilisation patterns varied by diagnosis; future research should examine associations between secure email use and utilisation patterns within and across diagnostic groups.26 Although our study expands the time period within which secure patient–clinician email has been studied, longitudinal studies on the order of 3–5 years are needed that track the relationship between secure email use and clinical service utilisation as organisational experience with patient portals accumulates. Our findings confirmed our original hypothesis. After controlling for the initial surge in utilisation after the index date, clinical services utilisation for late-stage enrollees returned to baseline, indicating that secure patient–clinician email may be a distinct form of patient contact that does not substitute for office and telephone contacts or avert ED and after-hours clinic visits and inpatient stays when there is a sudden and serious health event. Similar utilisation of clinical services by users and non-users over the longer term also suggests that patients who use secure email with clinicians are not inherently more likely to use all types of clinical services. However, more research is needed to understand the specific benefits to patients of secure email with clinicians and to investigate the use of healthcare services and health outcomes for patients who send multiple emails and are frequent portal users, compared with patients who send occasional emails and are low or moderate users of the portal. Doing so requires rigorous study designs. Conducting a randomised trial of secure patient–provider email communication within the USA would be difficult because this capability is a requirement of stage 2 meaningful use implementation of EHRs. Stepped wedge designs that can be conducted as implementation proceeds and RCTs conducted in other countries hold promise for adding to our understanding of the relationship between the use secure patient–clinician email and other types of clinical services.29–31

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to John F Steiner, MD, MPH, for his close review of the manuscript and incisive comments.

Footnotes

Contributors: DM, TEP, TG and HQ were involved in the conception and design of the study. MM and JT acquired the data that were analysed. DM, TEP, TG, JT and HQ analysed and interpreted the data. DM, TG, MM and JT drafted the manuscript. DM, TEP, TG, HQ and JT revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript. DM is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This data-only retrospective study required only approval by the KPCO Institutional Review Board for the use of data from the EHR database (reference number CO-14-2073); an ethics review was not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Frost & Sullivan. Market disruption imminent as hospitals and physicians aggressively adopt patient portal technology [news release] 2013. http://www.frost.com/prod/servlet/press-release.pag?docid=285477570

- 2.Emont S. Measuring the impact of patient portals: what the literature tells us. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates DW, Wells S. Personal health records and health care utilization. JAMA 2012;308:2034–6. 10.1001/jama.2012.68169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldzweig CL, Orshansky G, Paige NM et al. . Electronic patient portals: evidence on health outcomes, satisfaction, efficiency, and attitudes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:677–87. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atherton H, Sawmynaden P, Sheikh A et al. . Email for clinical communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:CD007978 10.1002/14651858.CD007978.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blue Ribbon Panel of the Society of General Internal Medicine. Redesigning the practice model for general internal medicine. A proposal for coordinated care: a policy monograph of the Society of General Internal Medicine. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:400–9. 10.1007/s11606-006-0082-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America; Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone JH. Communication between physicians and patients in the era of E-medicine. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2451–4. 10.1056/NEJMp068198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:759–69. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schickedanz A, Huang D, Lopez A et al. . Access, interest, and attitudes toward electronic communication for health care among patients in the medical safety net. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:914–20. 10.1007/s11606-012-2329-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baer D. Patient-physician e-mail communication: the Kaiser Permanente experience. J Oncol Pract 2011;7:230–3. 10.1200/JOP.2011.000323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenwood DA, Hankins AI, Parise CA et al. . A comparison of in-person, telephone, and secure messaging for type 2 diabetes self-management support. Diabetes Educ 2014;40:516–25. 10.1177/0145721714531337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wade-Vuturo AE, Mayberry LS, Osborn CY. Secure messaging and diabetes management: experiences and perspectives of patient portal users. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20:519–25. 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liederman EM, Lee JC, Baquero VH et al. . The impact of patient-physician Web messaging on provider productivity. J Healthc Inf Manag 2005;19:81–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Lusignan S, Mold F, Sheikh A et al. . Patients’ online access to their electronic health records and linked online services: a systematic interpretative review. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006021 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin CT, Wittevrongel L, Moore L et al. . An internet-based patient-provider communication system: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2005;7:e47 10.2196/jmir.7.4.e47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz SJ, Moyer CA, Cox DT et al. . Effect of a triage-based e-mail system on clinic resource use and patient and physician satisfaction in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:736–44. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20756.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz SJ, Nissan N, Moyer CA. Crossing the digital divide: evaluating online communication between patients and their providers. Am J Manag Care 2004;10:593–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou YY, Garrido T, Chin HL et al. . Patient access to an electronic health record with secure messaging: impact on primary care utilization. Am J Manag Care 2007;13:418–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris LT, Haneuse SJ, Martin DP et al. . Diabetes quality of care and outpatient utilization associated with electronic patient-provider messaging: a cross-sectional analysis. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1182–7. 10.2337/dc08-1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liss DT, Reid RJ, Grembowski D et al. . Changes in office visit use associated with electronic messaging and telephone encounters among patients with diabetes in the PCMH. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:338–43. 10.1370/afm.1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kummervold PE, Trondsen M, Andreassen H et al. . [Patient-physician interaction over the internet]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2004;124:2633–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.North F, Crane SJ, Chaudhry R et al. . Impact of patient portal secure messages and electronic visits on adult primary care office visits. Telemed J E Health 2014;20:192–8. 10.1089/tmj.2013.0097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergmo TS, Kummervold PE, Gammon D et al. . Electronic patient-provider communication: will it offset office visits and telephone consultations in primary care? Int J Med Inform 2005;74:705–10. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross SE, Moore LA, Earnest MA et al. . Providing a web-based online medical record with electronic communication capabilities to patients with congestive heart failure: randomized trial. J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e12 10.2196/jmir.6.2.e12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palen TE, Ross C, Powers JD et al. . Association of online patient access to clinicians and medical records with use of clinical services. JAMA 2012;308:2012–19. 10.1001/jama.2012.14126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hui RL, Yamada BD, Spence MM et al. . Impact of a Medicare MTM program: evaluating clinical and economic outcomes. Am J Manag Care 2014;20:e43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou YY, Leith WM, Li H et al. . Personal health record use for children and health care utilization: propensity score-matched cohort analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22:748–54. 10.1093/jamia/ocu018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:182–91. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mdege ND, Man MS, Taylor Nee Brown CA et al. . Systematic review of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials shows that design is particularly used to evaluate interventions during routine implementation. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:936–48. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woertman W, de Hoop E, Moerbeek M et al. . Stepped wedge designs could reduce the required sample size in cluster randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:752–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]