Abstract

Objective

To accurately define venous thromboembolism (VTE) in the routinely collected Swedish health registers and quantify its incidence in and around pregnancy.

Study design

Cohort study using data from the Swedish Medical Birth Registry (MBR) linked to the National Patient Registry (NPR) and the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (PDR).

Setting

Secondary care centres, Sweden.

Participant

509 198 women aged 15–44 years who had one or more pregnancies resulting in a live birth or stillbirth between 2005 and 2011.

Main outcome measure

To estimate the incidence rate (IR) of VTE in and around pregnancy using various VTE definitions allowing direct comparison with other countries.

Results

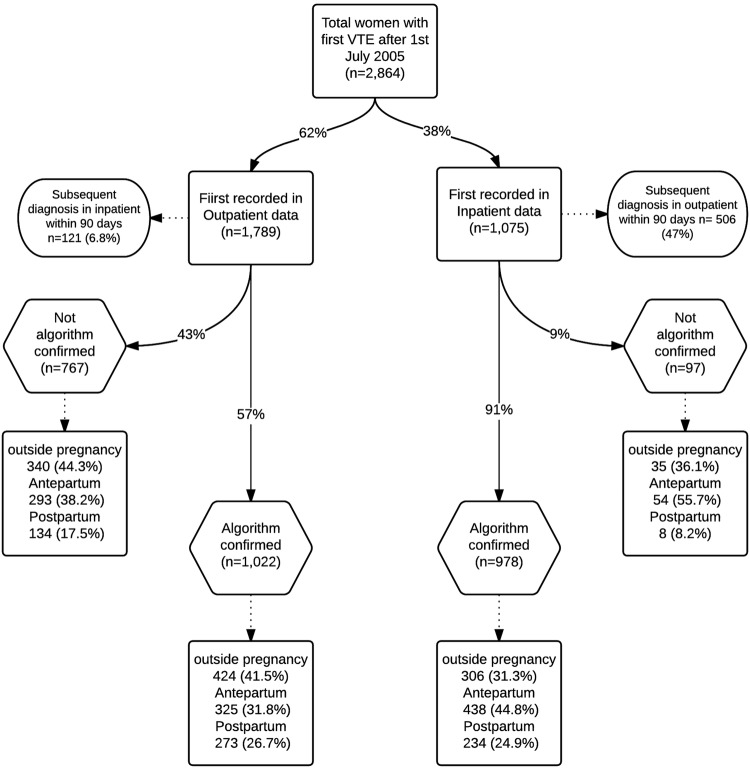

The rate of VTE varied based on the VTE definition. We found that 43% of cases first recorded as outpatient were not accompanied by anticoagulant prescriptions, whereas this proportion was much lower than those cases first recorded in the inpatient register (9%). Using our most inclusive VTE definition, we observed higher rates of VTE compared with previously published data using similar methodology. These reduced by 31% (IR=142/100 000 person-years; 95% CI 132 to 153) and 22% (IR=331/100 000 person-years; 95% CI 304 to 361) during the antepartum and postpartum periods, respectively, using a restrictive VTE definition that required anticoagulant prescriptions associated with diagnosis, which were more in line with the existing literature.

Conclusions

We found that including VTE codes without treatment confirmation risks the inclusion of false-positive cases. When defining VTE using the NPR, anticoagulant prescription information should therefore be considered particularly for cases recorded in an outpatient setting.

Keywords: OBSTETRICS, HAEMATOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We analysed more than 680 000 pregnancies to assess the robustness of the venous thromboembolism (VTE) diagnosis recorded in the Swedish National Patient Register using anticoagulant prescriptions in a way which has not been done before using these data.

The use of recent data from the national registries makes our study findings contemporary and generalisable to the majority of women of childbearing age.

Our VTE algorithm confirmation relies principally on anticoagulant prescriptions and we were not able to carry out any sort of external validation. However, our absolute rates of VTE in and around pregnancy are in line with the existing literature.

We may have incorrectly confirmed VTE cases for some women who were being prescribed low molecular weight heparin as thromboprophylaxis rather than therapy which we cannot accurately differentiate from registry data.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a serious and potentially fatal condition with an incidence of 1–3 per 1000 per year.1 Owing to its rarity, the use of large administrative healthcare data sets is a very cost-effective way to study the epidemiology of VTE in terms of incidence and identification of risk factors. While routinely collected administrative registry data have the advantage of being large, prospectively recorded, population based and with minimal selection or recall bias, ensuring their accuracy in diagnosis is paramount for the veracity of findings of studies using these data.

The Swedish National Patient Register (NPR) was established in 1964 with complete national coverage from 1987 onwards. To date, various validation studies have been conducted to ensure the quality of data for a wide range of acute and chronic conditions. For instance, a review of NPR validation studies conducted by Ludvigsson et al2 concluded that the positive predictive value (PPV) varies based on the diagnosis but generally ranges between 85% and 95%. However, it is noteworthy that the previous validation studies were only based on inpatient cases (those admitted) and did not specifically validate the outcome of VTE. The recent inclusion of the Swedish outpatient data (those presenting to hospital but not admitted) from 2001 onwards and the availability of linked data from the Prescribed Drug Register (PDR) now allows for the assessment of different definitions of VTE to determine the one most appropriate for use in epidemiological studies.3

A particular setting in which VTE has been commonly studied is in and around pregnancy as, although rare, VTE is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in developed countries.4 Our previous work using England's linked primary and secondary healthcare data has shown that the rate of VTE in and around pregnancy varies markedly depending on the data source and VTE definition used.5 A separate VTE validation study among pregnant women from Denmark6 reported the overall PPV to be 75% for inpatient cases but a much lower PPV (31%) for those only presenting to the emergency department. Similarly, Virkus et al7 in their study reported that 35% of women who received a diagnosis of VTE in the Danish NPR during pregnancy/postpartum were not validated (ie, they were false-positives).

The need to identify a robust definition of VTE for use in epidemiological studies is clear. Studying this rare event in and around pregnancy gives us the ability to directly compare estimates of incidence arising from the Swedish data with those from other countries where validation of definitions has previously been undertaken. The aim of our study was to use the Swedish NPR to determine the incidence rate of VTE in and around pregnancy using various VTE definitions and compare these with rates from other countries and healthcare settings.

Method

Data source

The Swedish Medical Birth Registry (MBR) was established in 1973 and collects information on antenatal and perinatal factors (eg, gestational length, mode of delivery) and their impact on the health of the mother and infant. The registry was standardised and computerised from 1982 onwards.8 It contains information on birth and delivery records from across Sweden with the addition of 100 000 births each year. Apart from delivery and birth information, the MBR also contains up to 12 diagnoses which may occur during pregnancy or in the course of the women's stay in the delivery unit. These are coded using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. The MBR has been subjected to numerous quality checks in the past and the data recorded are of a high standard.8 9 The personal identity number assigned to each resident in Sweden allows merging of data between registries such as the NPR and PDR at an individual level.10 The NPR initially only included the information on hospitalised patients (inpatient data); however, since 2001, it also includes outpatient consultations (outpatient data). The data contained within the NPR can mainly be categorised as patient-related data (eg, personal identity number, sex), administrative data (eg, visit date, admission and discharge dates) and medical data (eg, diagnosis and procedure information). Each diagnosis recorded within the NPR may be categorised as either a primary or secondary diagnosis. The primary diagnosis should be the main condition that was treated or investigated at the end of a hospital episode, whereas the secondary diagnosis may or may not be directly relevant to the primary diagnosis. Finally, filled drug prescriptions are recorded in PDR with the date of dispensing, drug name, strength and preparation according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification.11

Study population

For the purpose of this study, we included all women aged 15–44 years from the MBR who experienced a pregnancy between 1 July 2005 and 31 December 2011. Using data from 2005 allowed us to obtain prescription data for all of our study population.

Defining venous thromboembolism

Initially, our working VTE definition included all cases of VTE recorded in either the NPR (inpatient/outpatient) or MBR occurring at any time women were between 15 and 44 years of age, while pregnant or not. We used the relevant ICD, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes (as previously used,5 online supplementary table S1) to identify VTE diagnosis regardless of its hierarchical position in the diagnostic field (primary or secondary). These were then stratified by the source where the first VTE case was identified (inpatient vs outpatient data). All VTEs identified in the birth registry were categorised as inpatient VTEs. For the purpose of this study, we only included the first recorded VTE and therefore excluded all subsequent VTE diagnoses. Since the complete NPR coverage dates back to 1987, we also used the relevant ICD-9 codes (415, 451, 452, 453, 671 or 673) to exclude anyone with VTE prior to their entry into the study period. For all women with first VTE, we extracted information on anticoagulant therapy along with information on date and cause of death from the cause of death register, if the woman died within the study period.

Algorithm confirmation

A VTE code was considered to be algorithm confirmed if it was accompanied by an anticoagulant prescription (based on ATC codes; online supplementary table S2) within 90 days of the event or if the woman died within 30 days of the event and the underlying cause of death was VTE. This VTE definition has been validated previously in English healthcare data with a PPV of 84%.12 On the basis of the above information, we considered two VTE definitions.

VTE definition A: Any first VTE recorded in either inpatient or outpatient records regardless of algorithm confirmation.

VTE definition B: A first VTE event recorded as an inpatient or outpatient that was confirmed by our algorithm. As such, definition B consists of cases that are a subset of definition A.

Defining exposure time

Women's follow-up time between age 15–44 years was divided into time associated with pregnancy (defined from the date of conception based on a woman's gestational age until 12 weeks postpartum for each and every pregnancy identified) and ‘time outside pregnancy’ (all other available follow-up times as described previously).5 Time associated with pregnancy was subsequently split into antepartum and postpartum time. In order to minimise the potential misclassification5 between antepartum and postpartum events, a third category of ‘time around delivery’ was also considered. Therefore, the time associated with pregnancy was divided into the antepartum period (from the estimated date of conception until 2 days before the date of delivery), time around delivery (1 day before until 2 days after delivery) and the postpartum period, which was defined from 3 days after delivery until 12 weeks postpartum. Postpartum time was then further split into early postpartum (up to 6 weeks after delivery) and late postpartum (7–12 weeks after delivery).

Statistical analysis

We calculated the frequency and proportion of first identified VTE stratified by whether it was registered as an inpatient or outpatient visit. For each VTE definition, we calculated the rate of VTE per 100 000 person-years in and around pregnancy separately. We compared our absolute rate of VTE from each VTE definition during specific antepartum and postpartum periods with other similar studies from England5 and Denmark.13 The VTE incidence estimates in the English data were derived from a proportion of the English representative population. The diagnosis of VTE, whether they first presented as a hospital admission or in primary care, was confirmed using the same algorithm as used in the present study. The Danish VTE estimates were derived from the Danish NPR13 where the diagnosis of VTE recorded in the hospital discharge data had been previously validated in a small subset of the data. Finally, we compared the rate of VTE during the antepartum and postpartum periods to time outside pregnancy using a Poisson regression model to calculate incidence rate ratios (IRR) adjusted for age and calendar year. All analyses were performed using Stata V.12, Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA. This study was approved by the ethical review board.

Results

Study population

Our cohort consisted of 509 198 women who experienced at least one pregnancy resulting in a live birth or a stillbirth during the study period. Of the 681 756 pregnancies analysed, 2389 (0.4%) ended in a stillbirth. Our person-years of follow-up associated with different time periods of pregnancy and outside pregnancy are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study population

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of women aged 15–44 | 509 198 |

| Total number of pregnancies | 681 756 |

| Median follow-up | 6.5 years |

| Person-years of follow-up | |

| Outside pregnancy | 2 625 033 |

| Antepartum | 486 170 |

| Around delivery | 7438 |

| Postpartum | 153 465 |

| First VTE type (n=VTE events) | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 678 (24) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2186 (76) |

| Birth outcome (n=pregnancies) | |

| Live birth | 681 756 (99.6) |

| Stillbirth | 2389 (0.4) |

All figures are number (%) unless otherwise specified.

VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Confirmation of VTE cases

We identified a total of 2864 patients with first incident diagnosis of VTE from 2005, 1789 (62%) of which were first recorded at an outpatient visit (figure 1). We observed that 91% of VTEs first recorded during the inpatient visit were algorithm confirmed compared with 57% for those recorded as an outpatient. Of the total of 2000 patients with validated VTEs, 46% (n=928) received heparin/low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) within 90 days of the event, whereas 54% were prescribed warfarin (mostly during the postpartum period and time outside pregnancy). When comparing VTE cases between data sources, we found that 22% (n=627) of the patients with VTE had a diagnosis recorded both in inpatient and outpatient data within 90 days of the initial event with 20% (n=569) and 58% (n=1668) solely recorded in inpatient and outpatient data, respectively. Confirmation of VTE cases based on VTE type and position of diagnosis (primary vs secondary) is presented as online supplementary table S3. Of 757 cases of non-specific thrombophlebitis diagnoses, 25% (n=190) had evidence of hirudoid (C05BA01) prescriptions within 90 days of the event of which 44% (n=83) were confirmed based on our algorithm.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the first recorded venous thromboembolism (VTE) using the inpatient and outpatient register.

Absolute rate of VTE in and around pregnancy using various VTE definitions

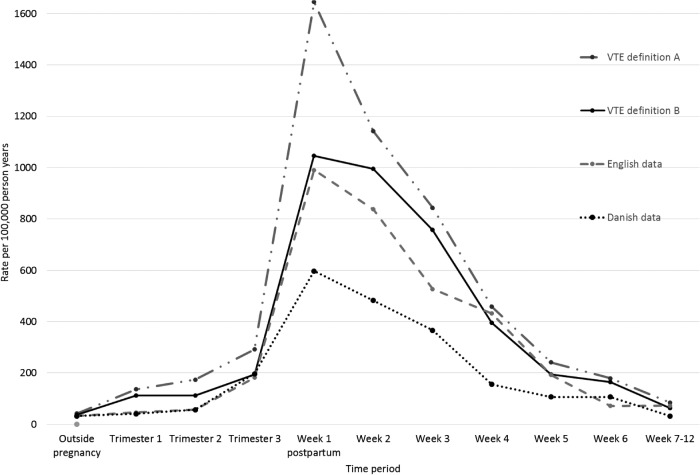

Using VTE definition A (any recording of VTE without confirmation), we found the absolute rate of VTE during the time outside pregnancy to be 42 per 100 000 person-years (table 2). This rate decreased to 38 per 100 000 person-years when we used our restricted VTE definition (VTE definition B). Figure 2 shows the rate of VTE by weeks of postpartum which shows variation during the first 3 weeks postpartum based on the VTE definition. The rates of VTE during specific antepartum and postpartum periods using VTE definition A were much higher than in previous studies using the Danish and English data with no overlapping CIs except for the time around delivery and the late postpartum period. However, the absolute rates using VTE definition B during the third trimester of antepartum, postpartum period and time outside pregnancy were broadly in line with the Danish and/or English data with overlapping CIs.

Table 2.

Absolute rate of first VTE per 100 000 person-years in and around pregnancy and outside pregnancy

| Time period | VTE definition A (using any code for VTE regardless of confirmation) | VTE definition B (using only algorithm-confirmed VTE) | English data5 |

Danish data13 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Rate (95% CI) | N | Rate (95% CI) | N | Rate | N | Rate | |

| Outside pregnancy | 1105 | 42 (40 to 44) | 1015 | 38 | 1480 | 32 (30–33) | 2895 | 36 (34–37) |

| Antepartum | 995 | 205 (192 to 218) | 690 | 142 (132 to 153) | 156 | 99 (85–116) | 491 | 107 (97–116) |

| Trimester 1 | 207 | 136 (118 to 155) | 172 | 113 (97 to 131) | 23 | 46 (31–70) | 61 | 41 (32–52) |

| Trimester 2 | 275 | 174 (154 to 196) | 178 | 112 (97 to 130) | 30 | 58 (41–83) | 75 | 57 (46–72) |

| Trimester 3 | 513 | 292 (268 to 319) | 340 | 194 (174 to 216) | 103 | 182 (150–221) | 355 | 197 (177–219) |

| Around delivery | 115 | 1546 (1288 to 1856) | 79 | 1061 (851 to 1323) | 34 | 1428 (1020–1998) | – | |

| Postpartum | 649 | 423 (392 to 457) | 509 | 331 (304 to 361) | 135 | 274 (231–324) | 218 | 175 (153–200) |

| Early postpartum | 584 | 754 (696 to 818) | 460 | 593 (541 to 650) | 177 | 468 (391–561) | 199 | 304 (264–350) |

| Late postpartum | 65 | 85 (70 to 109) | 49 | 64 (49 to 85) | 18 | 73 (46–116) | 319 | 32 (19–50) |

Early postpartum (first 6 weeks after delivery).

Late postpartum (6 weeks after delivery).

VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Figure 2.

Absolute rate of venous thromboembolism (VTE) per 100 000 person-years in and around pregnancy using different methods and data sources compared with the English5 and Danish data.13

IRR of VTE in and around pregnancy compared with time outside pregnancy

Using VTE definition A, we found a 5-fold (IRR=5.08; 95% CI 4.66 to 5.54) and 10-fold (IRR=10.2; 95% CI 9.27 to 11.25) higher rate of VTE during the antepartum and postpartum periods, respectively, compared with time outside pregnancy (table 3). Compared with time outside pregnancy, the overall IRRs during the antepartum (IRR=3.80) and postpartum (IRR=8.72) periods using definition B were very similar to the English data (IRR=3.10 and 8.54, respectively). In contrast, using VTE definition B in the Swedish data gave a statistically significant increased risk of VTE during the first trimester, which was not seen in the English or Danish data.

Table 3.

IRR of the rate of VTE using various analysis methods

| VTE definition A IRR* (95%CI) |

VTE definition B IRR* (95%CI) |

English data5 IRR (95%CI)† |

Danish data13 IRR (95%CI)† |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | ||||

| Outside pregnancy | Reference | |||

| Antepartum | 5.08 (4.66 to 5.54) | 3.80 (3.44 to 4.19) | 3.10 (2.63 to 3.66) | 2.95 (2.68 to 3.25) |

| Trimester 1 | 3.42 (2.95 to 3.98) | 3.04 (2.58 to 3.56) | 1.46 (0.96 to 2.20) | 1.12 (0.86 to 1.45) |

| Trimester 2 | 4.31 (3.78 to 4.93) | 3.01 (2.56 to 3.53 | 1.82 (1.27 to 2.62) | 1.58 (1.24 to 1.99) |

| Trimester 3 | 7.14 (6.43 to 7.94) | 5.12 (4.53 to 5.80) | 5.69 (4.66 to 6.95) | 5.48 (4.89 to 6.12) |

| Around delivery | 37.5 (30.9 to 44.45) | 27.97 (22.24 to 35.17) | 44.5 (31.68 to 62.54) | – |

| Postpartum | 10.21 (9.27 to 11.25) | 8.72 (7.83 to 9.70) | 8.54 (7.16 to 10.19) | 4.85 (4.21 to 5.57) |

| Early postpartum | 19.27 (16.53 to 20.21) | 15.62 (14.00 to 17.45) | 14.61 (12.10 to 17.67) | 8.44 (7.27 to 9.75) |

| Late postpartum | 2.06 (1.60 to 2.64) | 1.69 (1.26 to 2.25) | 2.29 (1.44 to 3.65) | 0.89 (0.53 to 1.39) |

Early postpartum (first 6 weeks after delivery).

Late postpartum (6 weeks after delivery).

*Adjusted for age and calendar year.

†Unadjusted ratio calculated based on the data provided.

IRR, incidence rate ratios; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Discussion

Main finding

Using a nationwide cohort of pregnant women, we have shown that the majority of first VTEs recorded in the Swedish inpatient data (91%) were accompanied by anticoagulant therapy following the event. This proportion, however, was much lower for those first recorded as outpatients. We also found that the rate of VTE in and around pregnancy and outside pregnancy varied based on the VTE definition used. Our most inclusive VTE definition (VTE definition A) gave us absolute rates of VTE in and around pregnancy which were much higher compared with those obtained from the English and Danish data. However, using a more restrictive definition of VTE which largely relied on confirmation of VTE cases based on anticoagulant therapy from the prescription register, we found absolute and relative rates of VTE to be more comparable with the English and/or Danish data which used similar definitions.

Strength and limitations

Using Swedish national registries, we analysed more than 680 000 pregnancies resulting in a live birth or stillbirth to determine how the incidence of VTE in and around pregnancy varies based on the VTE definition and data set used. The ability to combine national data from inpatient, outpatient, birth and prescription registers allowed us to directly assess the robustness of the VTE diagnosis occurring in different data sources in a way which has not been done before using these data. Furthermore, the use of recent data from the national registries makes our study findings contemporary and generalisable to the majority of women of childbearing age.

For our VTE definition B, we used an algorithm that mimics a previously validated VTE definition in the UK's primary care data with a PPV of 84%.12 This definition, though itself specifically validated in an outside pregnancy setting, has been shown to produce absolute rates of VTE during the antepartum and postpartum periods which are comparable to pooled estimates from several countries published in the existing literature.5 While we did not have the data to externally validate our VTE confirmation algorithm in the Swedish data, a similar VTE definition has been externally validated in the Danish patient register with a PPV of 99%.14 The study also highlighted that cross-linkage with the national register of medicinal products provides reliable validation of the VTE event. It is noteworthy that such a validation does not give us any indication of the negative predictive value and we cannot rule out that, particularly within pregnancy, certain women with VTE may receive anticoagulant prescription from hospital immediately following diagnosis not routinely recorded in the PDR. In this study, however, we believe that the impact of this will be minimal as women diagnosed with VTE are likely to be on anticoagulant therapy for at least 4 weeks, which should therefore be captured in the PDR.

Another limitation of this study is that our algorithm confirmation relies principally on anticoagulant prescriptions and we were not able to carry out any sort of external validation (review of medical records). Second, our algorithm only examines one dimension of case confirmation. The optimal validation study would examine specificity, sensitivity, and positive and negative predictive values for which no other data sources were available. However, the absolute rates using VTE definition B for antepartum and the early postpartum period of 142 and 593 per 100 000 person-years, respectively, are broadly in concordance with the pooled estimates5 from previous studies conducted after 2005 (118 and 424 per 100 000 person-years, respectively) with overlapping CIs.

Comparison with other studies

This study is not a traditional validation study as previously conducted in other settings,6 7 12 15 (ie, validating VTE cases by reviewing patients’ medical records). However, Rosengren et al16 carried out external validation of VTE cases identified in a random sample of men born between 1915 and 1922 and between 1924 and 1925 in a particular Swedish county in their study to quantify the impact of psychosocial factors on VTE using NPR. The study found that 85% and 70% of their inpatient recorded pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) cases, respectively, were externally validated. Our algorithm was able to confirm 94% and 88% of inpatient recorded PE and DVT cases, respectively, which may be due to changes in the diagnostic modalities and improvements in the recording of VTE from 1998 onwards. Our higher and lower number of cases confirmed in the outpatient and inpatient, respectively, have also been previously demonstrated in the Danish data6 where VTE diagnosis was validated by conducting a manual review of medical records for each patient. One possible explanation for the lower number of outpatient cases confirmed by our algorithm could be the potential inclusion of superficial thrombophlebitis treated with hirudoid. However, only 26% (n=98) of non-confirmed cases (based on our algorithm) of non-specific thrombophlebitis (ICD-10: I809, I821, I808, I803; ICD-9: 451, 671) recorded in the outpatient were prescribed hirudoid within 90 days of the event. Therefore it may be possible that those with suspected VTE seen in the outpatient are erroneously given VTE diagnosis before case confirmation which may require further investigation.

We found that, using our restrictive VTE definition, our absolute rates of antepartum and postpartum VTE were 31% and 22% lower, respectively, than VTE without confirmation (VTE definition A). This finding is consistent with another Danish validation study7 which reported that 40% and 21% of the VTE diagnosis during the antepartum and postpartum periods, respectively, are not validated. We do acknowledge that there may be differences between the Danish and Swedish registers in terms of data recording; therefore, the above comparisons should be interpreted with caution.

Our absolute rates of VTE during the first and second trimesters using VTE definition A were slightly higher than those reported by the English and Danish data. This finding is supplemented by the lower maternal VTE-related mortality observed in Sweden17 compared with England4 and Denmark.18 This may reflect better management/treatment of VTE, particularly during early pregnancy in Sweden. On that note, we cannot ignore the fact that there is a possibility that we have incorrectly included as VTE cases some women who were being treated with LMWH as preventive thromboprophylaxis rather than as a therapy for a newly occurring VTE event. There is, however, considerable difficulty in knowing the exact dosage of LMWH that a woman would or should receive for thromboprophylaxis as this is dependent on a combination of risk factors and physician judgement which we cannot presume to infer from registry data. The lower rate of VTE during the postpartum period in the Danish data might be due to the potential inclusion of only inpatient VTE cases (although this is not clearly stated in the study). However, even with the inclusion of outpatient data, concerns over their coverage and the use of many different definitions to record this information within the register should not be overlooked.19 Finally, our absolute rate of VTE during the antepartum and postpartum periods were much higher using VTE definition A compared with the previous studies done on the subject using data up to or after 2005.13 20 21 While our incidence rate of VTE in and around pregnancy varied based on VTE definition used, our IRR during the antepartum and postpartum periods compared with time outside pregnancy remained broadly similar. This, however, needs to be further investigated for other risk factors which may be more sensitive to VTE definition in these data.

Implications

Our study has important implications in the way VTE is defined in the Swedish NPR. While a higher proportion of VTEs first recorded in the inpatient data are accompanied by an anticoagulant prescription, this proportion was far lower for those first recorded in the outpatient data. If all outpatient cases were to be included in future research studies, they are likely to include false-positives, leading to an overestimation of risk if prescription information is not used. Our restrictive VTE definition provided absolute rates of VTE during the antepartum and postpartum periods that were more comparable to the estimates from the previously published English data, which used similar methodology for case confirmation. Although this study only assessed women of childbearing age (15–44 years) and further comparative studies should be recommended in other patient groups, we believe it is not unreasonable to suggest that prescription confirmation of VTE should be carefully considered when studying the epidemiology of VTE using the Swedish health registries.

Footnotes

Contributors: AAS, LJT, JW, KMF, MJG and DH conceived the idea for the study, with OS and JFL also making important contributions to the design of the study. AAS carried out the data management and analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors were involved in the interpretation of the data, contributed towards a critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final draft. AAS had full access to all of the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: AAS is jointly funded by the Nottingham Digestive Disease Centre and CORE/Coeliac UK. The collaboration between the University of Nottingham and the Karolinska Institute has been enabled by funding from JW's University of Nottingham/Nottingham University Hospital's NHS Trust Senior Clinical Research Fellowship which also pays his salary. DH is funded by an NIHR postdoctoral fellowship.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data are available by emailing the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Rashid S, Thursz M, Razvi N et al. . Venous thromboprophylaxis in UK medical inpatients. J R Soc Med 2005;98:507–12. 10.1258/jrsm.98.11.507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A et al. . External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martineau M, Nelson-Piercy C. Venous thromboembolic disease and pregnancy. Postgrad Med J 2009;85:489–94. 10.1136/pgmj.2009.079822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight M KS, Brocklehurst P, Neilson J, et al, eds, on behalf of MBRRACEUK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers' Care - Lessons learned to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–12. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdul Sultan A, Tata LJ, Grainge MJ et al. . The incidence of first venous thromboembolism in and around pregnancy using linked primary and secondary care data: a population based cohort study from England and comparative meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e70310 10.1371/journal.pone.0070310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Severinsen MT, Kristensen SR, Overvad K et al. . Venous thromboembolism discharge diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry should be used with caution. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:223–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virkus RA, Løkkegaard EC, Lidegaard Ø et al. . Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and the puerperal period: a study of 1210 events. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013;92:1135–42. 10.1111/aogs.12223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centre for Epidemiology, The National Board of Health and Welfare. The Swedish Medical Birth Registry—a summary of content and quality 2003. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/10655/2003–112-3_20031123.pdf (04/07/2014).

- 9.Cnattingius S, Ericson A, Gunnarskog J et al. . A quality study of a medical birth registry. Scand J Public Health 1990;18:143–8. 10.1177/140349489001800209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU et al. . The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659–67. 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM et al. . The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:726–35. 10.1002/pds.1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrenson R, Todd JC, Leydon GM et al. . Validation of the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in general practice database studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2000;49:591–6. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00199.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virkus RA, Løkkegaard ECL, Bergholt T et al. . Venous thromboembolism in pregnant and puerperal women in Denmark 1995–2005. A national cohort study. Thromb Haemost 2011;106:304–9. 10.1160/TH10-12-0823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lidegaard Ø, Nielsen LH, Skovlund CW et al. . Risk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses: Danish cohort study, 2001–9. BMJ 2011;343:d6423 10.1136/bmj.d6423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen TB, Johnsen SP, Møller CI et al. . A review of medical records and discharge summary data found moderate to high predictive values of discharge diagnoses of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and postpartum. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:316–19. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosengren A, Fredén M, Hansson PO et al. . Psychosocial factors and venous thromboembolism: a long-term follow-up study of Swedish men. J Thromb Haemost 2008;6:558–64. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02857.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The National Board of Health and Welfare. Statistical Database 2014. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistics/statisticaldatabase (accessed 02/01/2015).

- 18.BØDker B, Hvidman L, Weber TOM et al. . Maternal deaths in Denmark 2002–2006. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2009;88:556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyall H, Myers B. Incidence and management of 82 cases of pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism occurring at a single centre—comparison with Voke et al. Br J Haematol 2008;142:309–11; author reply 11–2 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07174.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Connor DJ, Scher LA, Gargiulo NJ III et al. . Incidence and characteristics of venous thromboembolic disease during pregnancy and the postnatal period: a contemporary series. Ann Vasc Surg 2011;25:9–14. 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]