Abstract

Objective

To determine the effect of preoperative patient and hospital factors on resource use, cost and length of stay (LOS) among patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCAB).

Design

Observational retrospective study.

Settings

Data from the Japanese Administrative Database.

Participants

Patients who underwent isolated, elective OPCAB between April 2011 and March 2012.

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcomes of this study were inpatient cost and LOS associated with OPCAB. A two-level hierarchical linear model was used to examine the effects of patient and hospital characteristics on inpatient costs and LOS. The independent variables were patient and hospital factors.

Results

We identified 2491 patients who underwent OPCAB at 268 hospitals. The mean cost of OPCAB was $40 665 ±7774, and the mean LOS was 23.4±8.2 days. The study found that select patient factors and certain comorbidities were associated with a high cost and long LOS. A high hospital OPCAB volume was associated with a low cost (−6.6%; p=0.024) as well as a short LOS (−17.6%, p<0.001).

Conclusions

The hospital OPCAB volume is associated with efficient resource use. The findings of the present study indicate the need to focus on hospital elective OPCAB volume in Japan in order to improve cost and LOS.

Keywords: CABG, Costs and cost analysis, Length of stay, Health resources, Multi-level analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Limited information is available on the effects of preoperative patient and hospital factors on resource use among patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCAB).

The findings of this study can contribute to the efficient use of healthcare resources in a country with a rapidly growing ageing population and to the reduction of healthcare expenditure.

This study did not compare on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting and OPCAB. Only patients who underwent isolated, elective OPCAB were included in this study.

This study was based on an administrative database. Therefore, it is difficult to account for underestimation/overestimation of comorbidities or postoperative complications and other factors that may influence the use of resources.

Data on the quality of care and the specific processes of care were lacking. These factors may influence the relationship between hospital volume and cost or length of stay.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the main causes of death in many countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).1 Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is one of the treatment approaches for revascularisation in patients with ischaemic heart disease. CABG can be performed both with and without cardiopulmonary bypass, and these are referred to as on-pump CABG and off-pump CABG (OPCAB), respectively.

A number of studies, including the CORONARY and ROOBY trials, have investigated the outcomes of both on-pump CABG and OPCAB and contributed to improving outcomes.2–8 However, there is little evidence about the cost of OPCAB, as other studies have focused on clinical outcomes and data on costs are less frequently available.

Many OECD countries are facing the challenges of rapid growth in the ageing population and in healthcare expenditure. Given this background and the continuing ageing of the population worldwide, it is necessary to explore determinants of resource use, such as the cost and length of stay (LOS) associated with various medical procedures, with a view to achieving a sustainable healthcare system.

Previous studies have examined the relationship between the resource use associated with CABG procedures, patient characteristics,9–11 clinical techniques or revascularisation procedures,12–14 and postoperative morbidity or complications.15 16 While OPCAB accounted for 60% of all CABG procedures in 2009 and is a major surgical procedure in Japan,17 few studies have been conducted to investigate the effect of both preoperative patient and hospital factors on OPCAB cost and LOS using multilevel analysis. Although Saleh et al18 investigated the effect of preoperative patient and hospital factors on CABG cost in the USA, the majority of the patients in their study underwent on-pump CABG.

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of preoperative patient and hospital factors on resource use, cost and LOS among patients undergoing OPCAB in Japan.

Materials and methods

Data source

We conducted a retrospective observational study using data from the Japanese Administrative Database, diagnosis procedure combination/per diem payment system (DPC/PDPS), gathered by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The details of the DPC/PDPS database have been described elsewhere.19 DPC/PDPS is a case-mix patient classification system that has been linked to payments at acute care hospitals in Japan since 2003.

The DPC/PDPS-based hospital reimbursement system had been adopted by more than 1400 hospitals by 2011, accounting for more than half of the total 910 000 hospital beds nationwide. The system covers approximately 50% of acute care inpatients discharged from hospitals in Japan. Among all the DPC/PDPS participating hospitals, 980 agreed to provide data for our research purposes, representing approximately 6.3 million cases and covering 77% of all admission cases tracked by DPC/PDPS.

Anonymous clinical and administrative claims data were collected annually for all patients admitted to and discharged from the participating hospitals. Clinical data consist of patient information, diagnosis information and detailed medical information, such as all major or minor procedures, medication and device use. Diagnosis information includes principal diagnosis, comorbidities on admission, and complications during hospitalisation, coded using the International Classification of Diseases and Injuries, 10th revision (ICD-10). Administrative claims data include all the prices for every procedure performed, which are evenly determined under a standardised fee-for-service payment system and listed in the nationally uniform fee table. The total medical costs of each hospitalisation are represented by the sum of these data. We defined cost according to the aforementioned criteria because fee-for-service-based payment represents resource use more directly, and we did not use the cost data based on the per diem payment schedule. Hospital information was also collected under the DPC/PDPS.

The board waived the requirement for patient informed consent because of the anonymous nature of the data.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We identified patients who underwent isolated, elective OPCAB in Japan between 1 April 2011 and 31 March 2012 (Japanese original operative codes K552-21 and K552-22).

We excluded the following three categories of OPCAB patients, in order to avoid confounding factors for the estimation of resource use, given the possibility of excessive use of healthcare resources: (1) patients with other major surgical procedures based on Japanese original operative codes; (2) non-elective OPCAB patients, such as ambulance or emergency admissions and (3) patients who underwent multiple OPCAB procedures or who died during hospitalisation. Additionally, observations with outlier costs (outside mean±2 SD), outlier preoperative LOS (>14 days) and missing data were excluded.

We obtained data regarding both individual-level and hospital-level characteristics. The individual variables included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina grade, number of anastomotic grafts per operation (patient), preoperative LOS, duration of anaesthesia, use of intra-aortic balloon pumping, and Elixhauser comorbidities based on Quan's methodology.20 Comorbidities appearing in fewer than 10 patients were not considered in this analysis. The DPC/PDPS database does not include information on operative time, but the duration of anaesthesia generally reflects operative time. The following four categories were defined for the duration of anaesthesia: ≤4, 4.5–6, 6.5–8, and ≥8.5 h.

The structural characteristics of the hospitals included academic status (teaching or not teaching), hospital ownership (private not-for-profit or public), hospital charge index (7:1 or 10:1), size and OPCAB volume. Hospital charge index is related to the nurse-to-bed ratio, and is reflected in the per diem medical expense (hospital charge index 7:1 receives a higher compensation than 10:1 as part of the basic medical fees for medical treatment and management during hospitalisation, based on a fee-for-service payment system).

Each hospital's OPCAB volume was calculated on the basis of the total number of patients who underwent OPCAB, including those with the aforementioned exclusion criteria, determined using the unique hospital identifier. Each hospital's OPCAB ratio (the number of OPCAB procedures divided by the total number of on-pump and off-pump CABG procedures) was also obtained (on-pump CABG; Japanese original operative codes K-552-1 and K-552-2). Hospital size was categorised according to the number of beds as follows: ≤449, 450–799 and ≥800, and hospital volume was categorised according to the number of procedures as follows: lowest quartile (≤14), second quartile (15–29), third quartile (30–59) and highest quartile (≥60).

Regarding the analysis of medical cost, costs were converted from Japanese yen to US$ (US$1=82.37 yen) based on purchasing power parities in March 2012.

Primary outcome

The primary outcomes of this study were inpatient cost and LOS associated with OPCAB.

Statistical analysis

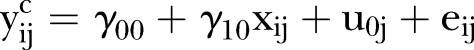

Descriptive statistics were obtained for patient and hospital factors. Hospital segment characteristics according to the hospital OPCAB volume were also described. Multivariate analysis was conducted using a two-level hierarchical linear model to examine the effect of patient and hospital characteristics on inpatient cost and LOS associated with OPCAB. The hierarchical linear regression model was used because of concerns about the potential clustering effect in a hospital, and it has been previously applied for analyses of volume-cost associations.18 21 A two-level hierarchical model was fitted to predict log-normalised cost and log-normalised LOS. The level 1 model incorporated patient-level characteristics, and the level 2 model investigated the influence of hospital-level factors. The model takes the following general form:

|

Level 1 units are indexed by i and level 2 units are indexed by j, where  is the logarithmic dependent variable (cost or LOS) of patient i in hospital j,

is the logarithmic dependent variable (cost or LOS) of patient i in hospital j,  is the hospital-level mean intercept,

is the hospital-level mean intercept,  is the constant regression coefficient (subject j is unnecessary because the slope is constant across hospitals),

is the constant regression coefficient (subject j is unnecessary because the slope is constant across hospitals),  is the explanatory variable of patient i in hospital j,

is the explanatory variable of patient i in hospital j,  is the hospital-dependent deviation and

is the hospital-dependent deviation and  is the residual error for patient i in hospital j.

is the residual error for patient i in hospital j.

First, a stepwise multivariate regression analysis was performed, using patient demographics and risk factors, to predict log-cost and log-LOS. All variables significant at the 0.05 level were then included as level 1 factors and modelled as random effects for each model. The level 1 intercept was modelled as random, with hospital factors as fixed-effect predictors. Among the individual variables, age, sex and clinical risk factors were level 1 predictors, while academic status, ownership, hospital charge index, size and hospital OPCAB volume were level 2 predictors.

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±SD or median (25th, 75th centile) depending on the overall variable distribution, and categorical variables are expressed as proportions. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.22.0 (IBM Japan Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). The analyses were two-tailed, and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient and hospital characteristics

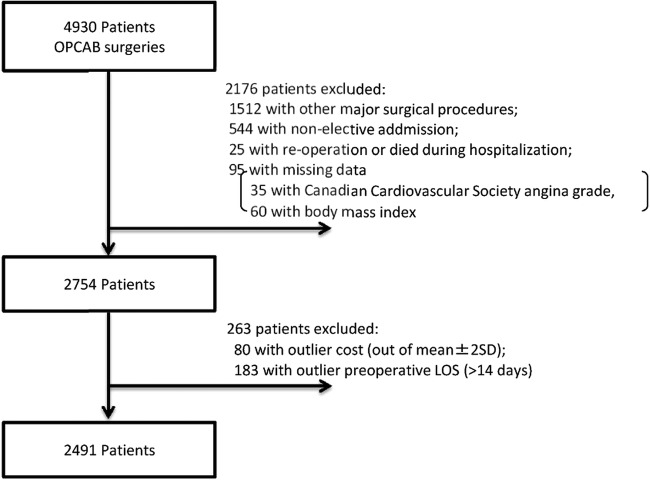

The data of 4930 patients who underwent OPCAB were extracted. However, we excluded 2176 patients (1512 who underwent other major surgical procedures, 544 who had non-elective admissions, 25 who underwent multiple OPCAB procedures or died during hospitalisation, and 95 who had missing data (35 who had missing Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina grade and 60 who had missing BMI data)). Additionally, 80 patients who had outlier costs (outside mean±2 SD) and 183 patients who had outlier preoperative LOS (>14 days) were excluded. Our final sample included 2491 patients who were treated at 268 hospitals (figure 1). Patient and hospital characteristics are presented in table 1. The mean cost associated with OPCAB was $40 665±7774, and the mean LOS associated with OPCAB was 23.4±8.2 days. More than two-thirds of the patients were 65 years of age or older (67.5%) and most patients were male (79.3%). Patients with a BMI <25 kg/m2 accounted for approximately two-thirds (66.5%) of the study patients. The most common comorbidity was uncomplicated hypertension (58.5%).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing initial patient eligibility, application of exclusion criteria and final inclusion of patients in the study (n=2491) (LOS, length of stay; OPCAB, off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting).

Table 1.

Patient and hospital characteristics

| Characteristics (n=2491) | n/mean | Per cent/SD |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| <65 | 810 | 32.5 |

| 65–74 | 1052 | 42.2 |

| ≥75 | 629 | 25.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1976 | 79.3 |

| Female | 515 | 20.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| <25 | 1657 | 66.5 |

| 25–29 | 723 | 29.0 |

| ≥30 | 111 | 4.5 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Not smoking | 1095 | 44.0 |

| Smoking | 1396 | 56.0 |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina grade | ||

| 1 and 2 | 1685 | 67.6 |

| 3 and 4 | 806 | 32.4 |

| Number of anastomotic grafts | ||

| 1 | 198 | 7.9 |

| ≥2 | 2293 | 92.1 |

| Use of IABP | ||

| No | 2263 | 90.8 |

| Yes | 228 | 9.2 |

| Preoperative LOS (days) | ||

| ≤3 | 879 | 35.3 |

| 4–6 | 900 | 36.2 |

| 7–9 | 482 | 19.3 |

| ≥10 | 230 | 9.2 |

| Duration of anaesthesia (hours) | ||

| ≤4 | 1495 | 60.0 |

| 4.5–6 | 429 | 17.2 |

| 6.5–8 | 390 | 15.7 |

| ≥8.5 | 177 | 7.1 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities* | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 551 | 22.1 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 239 | 9.6 |

| Valvular disease | 110 | 4.4 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 253 | 10.2 |

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 1456 | 58.5 |

| Hypertension, complicated | 11 | 0.4 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 76 | 3.1 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 797 | 32.0 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 340 | 13.6 |

| Hypothyroidism | 19 | 0.8 |

| Renal failure without dialysis | 116 | 4.7 |

| Renal failure with dialysis | 161 | 6.5 |

| Liver disease | 55 | 2.2 |

| Peptic ulcer disease excluding bleeding | 260 | 10.4 |

| Solid tumour without metastasis | 81 | 3.3 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis collagen vascular disease | 14 | 0.6 |

| Coagulopathy | 30 | 1.2 |

| Deficiency anaemia | 91 | 3.7 |

| Depression | 13 | 0.5 |

| Hospital characteristics | ||

| Academic status | ||

| Not teaching | 1836 | 73.7 |

| Teaching | 655 | 26.3 |

| Ownership | ||

| Public | 859 | 34.5 |

| Private not-for-profit | 1632 | 65.5 |

| Hospital index charge | ||

| 10:1 | 230 | 9.2 |

| 7:1 | 2261 | 90.8 |

| Size | ||

| ≤449 | 630 | 25.3 |

| 450–799 | 1298 | 52.1 |

| ≥800 | 563 | 22.6 |

| Hospital OPCAB volume | ||

| ≤14 | 498 | 20.0 |

| 15–29 | 680 | 27.3 |

| 30–59 | 727 | 29.2 |

| ≥60 | 586 | 23.5 |

| Resource use per patient | ||

| Total cost (US$; mean, SD) | 40 665 | 7774 |

| LOS (days; mean, SD) | 23.37 | 8.17 |

*Comorbidities present in <10 patients were not considered in this analysis.

BMI, body mass index; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pumping; LOS, length of stay; OPCAB, off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting.

The number of hospitals and patients according to the hospital OPCAB volume groups are described in table 2. About a quarter of the patients were treated at academic hospitals (26.3%). Additionally, more than half of the hospitals had private, not-for-profit ownership (57.8%), and these hospitals treated approximately two-thirds of the patients (65.8%). Some of the biggest hospitals had the least OPCAB volumes, and this may have occurred because these hospitals provide on-pump CABG or percutaneous coronary intervention instead of OPCAB or because other hospitals in the region are in charge of handling heart surgeries, with regard to functional differentiation of hospitals.

Table 2.

Hospital segment characteristics according to hospital OPCAB volume

| Hospitals (patients) | Hospital procedure volume |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest quartile (≤14) |

Second quartile (15–29) |

Third quartile (30–59) |

Highest quartile (≥60) |

|||||

| All hospitals (all patients) | 148 | (498) | 67 | (680) | 40 | (727) | 13 | (586) |

| Teaching | 25 | (73) | 20 | (199) | 11 | (208) | 5 | (175) |

| Private not-for-profit ownership | 81 | (267) | 41 | (435) | 22 | (404) | 11 | (526) |

| Hospital index charge (7:1) | 125 | (414) | 58 | (582) | 37 | (701) | 12 | (564) |

| Size | ||||||||

| ≤449 | 55 | (179) | 22 | (217) | 8 | (135) | 3 | (99) |

| 450–799 | 77 | (265) | 32 | (315) | 20 | (346) | 7 | (372) |

| ≥800 | 16 | (54) | 13 | (148) | 12 | (246) | 3 | (115) |

| OPCAB ratio, mean (SD) | ||||||||

| All | 34.3% | (23.5%) | 61.3% | (16.8%) | 67.0% | (13.8%) | 69.1% | (11.9%) |

| ≤449 | 36.7% | (27.8%) | 62.9% | (17.7%) | 77.0% | (12.6%) | 52.4% | (6.1%) |

| 450–799 | 35.0% | (20.9%) | 64.6% | (15.7%) | 69.3% | (13.1%) | 76.3% | (6.9%) |

| ≥800 | 22.5% | (15.9%) | 50.4% | (14.0%) | 56.4% | (8.6%) | 69.2% | (8.3%) |

A total of 268 hospitals and 2491 OPCAB procedures were considered during the study period.

OPCAB ratio: the number of OPCAB procedures divided by the total number of on-pump CABG and OPCAB procedures.

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; OPCAB, off-pump.

Medical cost

The results of the multivariate hierarchical linear model of the OPCAB cost are shown in table 3. The OPCAB cost was 3.0% higher among patients aged 65–74 years than among those aged <65 years, and the cost was 5.2% higher among patients aged ≥75 years than among those aged <65 years. Within comorbidities, renal failure (with or without dialysis) was significantly associated with high cost. Additionally, a long duration of anaesthesia was associated with high cost. However, peptic ulcer disease without bleeding was associated with low cost.

Table 3.

Hierarchical linear model (random intercept model) for OPCAB cost

| Characteristics | Multiplier* (95% CI) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Intercept, $ | 31 110 | (29 526 to 32 779) | <0.001 |

| Preoperative LOS (days) (ref ≤3) | |||

| 4–6 | 1.024 | (1.010 to 1.038) | 0.001 |

| 7–9 | 1.058 | (1.034 to 1.063) | <0.001 |

| ≥10 | 1.112 | (1.074 to 1.110) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) (ref <65) | |||

| 65–74 | 1.030 | (1.015 to 1.035) | <0.001 |

| ≥75 | 1.052 | (1.031 to 1.055) | <0.001 |

| Number of anastomotic grafts (ref 1) | |||

| ≥2 | 1.118 | (1.079 to 1.116) | <0.001 |

| Use of IABP (ref no) | |||

| Yes | 1.202 | (1.147 to 1.186) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure with dialysis | 1.190 | (1.136 to 1.177) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure without dialysis | 1.127 | (1.083 to 1.128) | <0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease excluding bleeding | 0.981 | (0.970 to 0.999) | 0.037 |

| Liver disease | 1.044 | (1.007 to 1.066) | 0.014 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.011 | (0.998 to 1.020) | 0.091 |

| Duration of anaesthesia (hours) (ref ≤4) | |||

| 6.5–8 | 1.046 | (1.022 to 1.054) | <0.001 |

| ≥8.5 | 1.135 | (1.088 to 1.135) | <0.001 |

| Hospital characteristics | |||

| Teaching | 1.058 | (1.012 to 1.086) | 0.009 |

| Private not-for-profit ownership | 1.037 | (1.004 to 1.058) | 0.023 |

| Hospital index charge (ref 10:1) | |||

| 7:1 | 1.015 | (0.979 to 1.047) | 0.481 |

| Size (ref ≤449) | |||

| 450–799 | 1.018 | (0.987 to 1.043) | 0.307 |

| ≥800 | 0.991 | (0.952 to 1.036) | 0.732 |

| OPCAB hospital volume (ref ≤14) | |||

| 15–29 | 0.985 | (0.962 to 1.015) | 0.379 |

| 30–59 | 1.008 | (0.975 to 1.039) | 0.700 |

| ≥60 | 0.934 | (0.901 to 0.992) | 0.024 |

*Exponentiated parameter estimates from a log model.

IABP, intra-aortic balloon pumping; LOS, length of stay; OPCAB, off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting.

At the second level of the hierarchical structure, the OPCAB cost was 5.8% higher among academic hospitals than among non-academic hospitals, and the cost was 3.7% higher among private not-for-profit hospitals than among public hospitals. The hospital size was not associated with cost. The OPCAB cost was 6.6% lower among hospitals with a total OPCAB volume of ≥60 than among hospitals with a total OPCAB volume of ≤14.

Length of stay

The results of the multivariate hierarchical linear model of OPCAB LOS are shown in table 4. OPCAB LOS was 3.8% longer among patients aged 65–74 years than among those aged <65 years, and LOS was 9.3% longer among patients aged ≥75 years than among those aged <65 years. OPCAB LOS was 4.3% longer among female patients than among male patients. Several comorbidities were found to increase OPCAB LOS, and these included renal failure (with or without dialysis), complicated or uncomplicated diabetes, cardiac arrhythmias, liver disease and coagulopathy. In contrast, LOS was short among patients with deficiency anaemia.

Table 4.

Hierarchical linear model (random intercept model) for OPCAB LOS

| Characteristics | Multiplier* (95% CI) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Intercept, days | 18.0 | (16.5 to 19.6) | <0.001 |

| Preoperative LOS (days) (ref ≤3) | |||

| 4–6 | 1.137 | (1.109 to 1.166) | <0.001 |

| 7–9 | 1.284 | (1.246 to 1.323) | <0.001 |

| ≥10 | 1.516 | (1.462 to 1.572) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) (ref <65) | |||

| 65–74 | 1.038 | (1.015 to 1.061) | 0.001 |

| ≥75 | 1.093 | (1.065 to 1.122) | <0.001 |

| Sex (ref male) | |||

| Female | 1.043 | (1.017 to 1.070) | 0.001 |

| Smoking status (ref not smoking) | |||

| Smoking | 0.978 | (0.958 to 0.999) | 0.040 |

| Use of IABP (ref no) | |||

| Yes | 1.039 | (1.002 to 1.076) | 0.041 |

| Renal failure with dialysis | 1.099 | (1.056 to 1.143) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure without dialysis | 1.079 | (1.032 to 1.131) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 1.050 | (1.020 to 1.083) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 1.031 | (1.009 to 1.054) | 0.005 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 1.051 | (1.018 to 1.086) | 0.003 |

| Peptic ulcer disease excluding bleeding | 0.971 | (0.939 to 1.004) | 0.082 |

| Deficiency anaemia | 0.934 | (0.886 to 0.984) | 0.012 |

| Liver disease | 1.071 | (1.005 to 1.143) | 0.034 |

| Coagulopathy | 1.112 | (1.020 to 1.215) | 0.016 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1.110 | (0.997 to 1.237) | 0.056 |

| Hypertension, complicated | 1.113 | (0.966 to 1.289) | 0.139 |

| Duration of anaesthesia (hours) (ref ≤4) | |||

| 6.5–8 | 1.026 | (0.994 to 1.055) | 0.107 |

| ≥8.5 | 1.071 | (1.028 to 1.135) | 0.001 |

| Hospital characteristics | |||

| Teaching | 1.075 | (1.001 to 1.144) | 0.046 |

| Private not-for-profit ownership | 1.013 | (0.961 to 1.068) | 0.622 |

| Hospital index charge (ref 10:1) | |||

| 7:1 | 1.044 | (0.974 to 1.122) | 0.225 |

| Size (ref ≤449) | |||

| 450–799 | 1.005 | (0.950 to 1.067) | 0.862 |

| ≥800 | 0.960 | (0.881 to 1.055) | 0.350 |

| OPCAB hospital volume (ref ≤14) | |||

| 15–29 | 0.947 | (0.897 to 1.001) | 0.053 |

| 30–59 | 0.988 | (0.927 to 1.054) | 0.719 |

| ≥60 | 0.824 | (0.748 to 0.909) | <0.001 |

*Exponentiated parameter estimates from a log model.

IABP, intra-aortic balloon pumping; LOS, length of stay; OPCAB, off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting.

Few hospital characteristics showed association with prolonged LOS, only academic hospitals was associated with 7.5% longer LOS. However, OPCAB LOS was 17.6% shorter among hospitals with a total OPCAB volume of ≥60 than among hospitals with a total OPCAB volume of ≤14.

Discussion

Many OECD countries are facing the challenge of rapid growth in the ageing population, which is creating an extra economic burden through growing healthcare expenditure. According to OECD health data, the growth of health expenditure has exceeded economic growth in most OECD countries, despite efforts to restrain health expenditure.22 However, analyses of healthcare resource use, especially cost, for many procedures have lagged behind as a means of improving efficiency in healthcare systems.

Our study showed that specific patient and hospital factors affected OPCAB cost and LOS. Among hospital factors, academic hospitals and private not-for-profit hospitals were associated with high cost. Additionally, a high OPCAB volume was associated with low cost and a short LOS.

Interestingly, the patient factors affecting OPCAB cost do not exactly correspond to those affecting LOS. For example, coagulopathy was associated with a long LOS but not with high cost. Patients with coagulopathy may require extended hospitalisation with careful monitoring to achieve stable control of clotting, without aggressive treatments, leading to a long LOS with a minor increase in cost. Additionally, there were some differences in the effects of common patient factors on cost and LOS. LOS was 1.3 days longer and the cost was $1375 higher ($1077 per day) among patients with liver disease than among patients without, and LOS was 1.8 days longer and the cost was $5896 higher ($3318 per day) among patients with renal failure than among patients without. Understanding the different effects of the patient factors could help reduce the use of resources. Our findings imply that various approaches for revealing how these factors affect resource use are needed to reduce healthcare resource expenditure on OPCAB procedures.

In terms of hospital factors, our study found an association between procedure volume and healthcare resource use for elective isolated OPCAB procedures. The association implies the need to concentrate on the hospital-level OPCAB volume, which will contribute to cost reduction18 23 and may contribute to patients’ outcomes regarding volume-outcome association.4 8 24 In parallel, analyses of geographical aspects in relation to OPCAB patients need to be considered. It is very important to achieve good outcomes, as well as access to healthcare services under the universal healthcare service system.1 However, some reports in the literature did not demonstrate any volume-cost association25 or volume-outcome relationship for CABG procedures.26 Further studies evaluating the difference in the use of resources, such as medications, medical devices, preoperative or postoperative care, and facility equipment, between high-volume and low-volume hospitals will help to effectively provide healthcare services.

Compared with the hospital procedure volume in a previous volume-cost study in the USA,18 the hospital procedure volume was not well concentrated in our study. We categorised hospital procedure volumes as ≤14, 15–29, 30–59 and ≥60, while the previous study categorised them as ≤99, 100–249, 250–499 and ≥500. This situation may support the concentration of hospital OPCAB volume.

Comparison of the cost of surgeries among countries is difficult owing to differences in the medical service fee system; however, our results may be generalised to other countries that have a case-mix payment system because the reimbursements were mainly adjusted on the basis of cost estimation. Regarding international generalisation, it is important to investigate the mechanisms that aid hospitals in achieving cost-effectiveness, which will help identify cost-effectiveness factors that can be applied or introduced in hospitals in other countries.

We used a hierarchical linear model (random intercept model) that allows the consideration of both patient and hospital factors, while a previous study exploring variations in cost and LOS across hospitals for diagnosis-related groups used a two-step multilevel model.27 We did not use the two-step multilevel model, avoiding a step of consideration of which DPC/PDPS payment group patients allocated, this is because (1) we used cost data based on fee-for-service schedule, not on DPC/PDPS schedule, (2) a couple of clinical processes were considered instead of the DPC/PDPS group and only includes isolated elective OPCAG patients. The DPC/PDPS-based cost data comprise the DPC component and fee-for-service component. Economic analysis with the DPC/PDPS-base cost data may need the establishment of a methodological approach. The selection of the model should be well considered according to the aim of the study and available data with its characteristics.

This study had some potential limitations. First, although it had a large sample size with detailed medical data, the Japanese administrative database of the DPC/PDPS study group does not cover all patients and only approximately 40% of the total number of patients nationally are covered with two stages of sample selection. Second, the use of an administrative claims database could have led to an underestimation/overestimation of comorbidities or postoperative complications as a result of incomplete reporting. For example, peptic ulcer disease excluding bleeding was associated with a low OPCAB cost in this analysis. We speculate that the presence of such a comorbidity might indicate a patient who is only mildly symptomatic, apart from the primary ischaemic heart event. Third, several factors that may affect resource use, such as the use of clinical pathways, were not considered in our study because of lack of available data. Fourth, we were unable to determine complications and deaths that occurred after discharge or transfer to another hospital, which may have resulted in an underestimation of the cost and LOS. Fifth, we were also unable to distinguish the primary OPCAB from others due to the study period, which may exist as a compounding factor.

Our study focused on the hospitalisation cost of OPCAB, which would reflect the use of healthcare resources in acute care hospitals. We analysed cost according to the patient-level payment to hospitals because it is difficult to obtain actual cost data for each patient. The difference between cost and payment may be a potential limitation of this study. Our analyses included only Elixhauser comorbidities. Other comorbidities or conditions may have existed as potential confounders. The procedure volume per surgeon/anaesthesiologist was not included in our analysis owing to the lack of data. Moreover, an adjustment according to teaching status may not be sufficient because it is difficult to measure teaching activity in each hospital.

Data on quality of care and the specific processes of care that may contribute to the causal pathway linking hospital volume and cost or LOS were lacking. Relationships such as that between the hospital complication ratio and the episode payment28 may also affect the volume-cost relationship. Further study of the relationship between hospital volume and cost, considering the quality of care in more detail, will be needed to address this issue.

Conclusion

Several patient and hospital factors affect OPCAB resource use. It is necessary to explore ways to obtain better outcomes, as well as to reduce healthcare resource use in order to achieve a sustainable healthcare system. The findings of this study indicate the need to focus on hospital elective OPCAB volume in Japan in order to improve cost and LOS.

Footnotes

Contributors: DS conceived of the study. DS and KF contributed to the refinement of the study protocol and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Research on Policy Planning and Evaluation (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, H25-SEISAKU-SITEI-010 and H26-SEISAKU-SITEI-011) and by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 24590604).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the institutional review board at Tokyo Medical and Dental University (Tokyo, Japan).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.OECD. Health at a Glance 2013: OECD indicators. http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Health-at-a-Glance-2013.pdf (accessed 15 Dec 2014).

- 2.Shroyer AL, Grover FL, Hattler B et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1827–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa0902905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamy A, Devereaux PJ, Prabhakaran D et al. Off-pump or on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting at 30 days. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1489–97. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyata H, Motomura N, Ueda Y et al. Effect of procedural volume on outcome of coronary artery bypass graft surgery in Japan: implication toward public reporting and minimal volume standards. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;135:1306–12. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.10.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deb S, Wijeysundera HC, Ko DT et al. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery vs percutaneous interventions in coronary revascularization: a systematic review. JAMA 2013;310:2086–95. 10.1001/jama.2013.281718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auerbach AD, Hilton JF, Maselli J et al. Shop for quality or volume? Volume, quality, and outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:696–704. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drenger B, Fontes ML, Miao Y et al. Patterns of use of perioperative angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in coronary artery bypass graft surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: effects on in-hospital morbidity and mortality. Circulation 2012;126:261–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.059527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sepehripour AH, Athanasiou T. Is there a surgeon or hospital volume-outcome relationship in off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013;16:202–7. 10.1093/icvts/ivs448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurki TS, Häkkinen U, Lauharanta J et al. Evaluation of the relationship between preoperative risk scores, postoperative and total length of stays and hospital costs in coronary bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:1183–7. 10.1016/S1010-7940(01)00988-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokolovic E, Schmidlin D, Schmid ER et al. Determinants of costs and resource utilization associated with open heart surgery. Eur Heart J 2002;23:574–8. 10.1053/euhj.2001.3031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maziarz DM, Koutlas TC. Cost considerations in selecting coronary artery revascularization therapy in the elderly. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2004;4:219–25. 10.2165/00129784-200404040-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gershlick T, Thomas M. PCI or CABG: which patients and at what cost? Heart 2007;93:1188–90. 10.1136/hrt.2007.124750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anastasiadis K, Fragoulakis V, Antonitsis P et al. Coronary artery bypass grafting with minimal versus conventional extracorporeal circulation; an economic analysis. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:5336–43. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner TH, Hattler B, Bishawi M et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: cost-effectiveness analysis alongside a multisite trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:770–7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speir AM, Kasirajan V, Barnett SD et al. Additive costs of postoperative complications for isolated coronary artery bypass grafting patients in Virginia. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:40–5; discussion 45–46 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.03.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaPar DJ, Crosby IK, Rich JB et al. A contemporary cost analysis of postoperative morbidity after coronary artery bypass grafting with and without concomitant aortic valve replacement to improve patient quality and cost-effective care. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:1621–7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakata R, Fujii Y, Kuwano H, Committee for Scientific Affairs. Thoracic and cardiovascular surgery in Japan during 2009: annual report by the Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;59:636–67. 10.1007/s11748-011-0838-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saleh SS, Racz M, Hannan E. The effect of preoperative and hospital characteristics on costs for coronary artery bypass graft. Ann Surg 2009;249:335–41. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318195e475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fushimi K, Hashimoto H, Imanaka Y et al. Functional mapping of hospitals by diagnosis-dominant case-mix analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:50 10.1186/1472-6963-7-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin CS, Lee HC, Lin CT et al. The association between surgeon case volume and hospitalization costs in free flap oral cancer reconstruction operations. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;122:133–9. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181773d71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.OECD. Health: spending continues to outpace economic growth in most OECD countries. http://www.oecd.org/newsroom/healthspendingcontinuestooutpaceeconomicgrowthinmostoecdcountries.htm (accessed 16 Dec 2014).

- 23.Auerbach AD, Hilton JF, Maselli J et al. Case volume, quality of care, and care efficiency in coronary artery bypass surgery. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1202–8. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hockenberry JM, Lien HM, Chou SY. Surgeon and hospital volume as quality indicators for CABG in Taiwan: examining hazard to mortality and accounting for unobserved heterogeneity. Health Serv Res 2010;45:1168–87. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01137.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regenbogen SE, Gust C, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital surgical volume and cost of inpatient surgery in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg 2012;215:758–65. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaPar DJ, Kron IL, Jones DR et al. Hospital procedure volume should not be used as a measure of surgical quality. Ann Surg 2012;256:606–15. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826b4be6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Street A, Kobel C, Renaud T et al. EuroDRG group. How well do diagnosis-related groups explain variations in costs or length of stay among patients and across hospitals? Methods for analysing routine patient data. Health Econ 2012;21(Suppl 2):6–18. 10.1002/hec.2837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birkmeyer JD, Gust C, Dimick JB et al. Hospital quality and the cost of inpatient surgery in the United States. Ann Surg 2012;255:1–5. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182402c17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]