Abstract

The accumulation of senile plaques composed of amyloid-β (Aβ) fibrils is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), although prefibrillar oligomeric species are believed to be the primary neurotoxic congeners in AD pathogenesis. Uncertainty regarding the mechanistic relationship between Aβ oligomer and fibril formation and the cytotoxicity of these aggregate species persists. β-Turn formation has been proposed to be a potential rate limiting step during Aβ fibrillogenesis. The effect of turn nucleation on Aβ self-assembly was probed by systematically replacing amino acid pairs in the putative turn region of Aβ (residues 24–27) with d-ProGly, an effective turn nucleating motif. The kinetic, thermodynamic, and cytotoxic effects of these mutations were characterized. It was found that turn formation dramatically accelerated Aβ fibril self-assembly dependent on the site of turn nucleation. The cytotoxicity of the three d-ProGlycontaining Aβ variants was significantly lower than that of wild-type Aβ40, presumably due to decreased oligomer populations as a function of more rapid progression to mature fibrils; oligomer populations were not eliminated, however, suggesting that turn formation is also a feature of oligomer structures. These results indicate that turn nucleation is a critical step in Aβ40 fibril formation.

Keywords: Amyloid-β, turn nucleation, Alzheimer’s disease, β-hairpin, fibril self-assembly

Introduction

Amyloid-β (Aβ) is a 39–43 residue amyloidogenic peptide that has been implicated as a causative agent in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).1–7 Symptoms of AD include impairment of episodic memory caused by severe neuronal atrophy and cell death caused by toxic conformers of the Aβ peptide. Though Aβ is present at low levels in the brain of healthy individuals, assembly of Aβ into cross-β structures leads to the accumulation of neuritic plaques that are among the hallmarks of AD.8–10 Evidence now suggests that prefibrillar, low molecular weight (LMW) Aβ oligomers, and not Aβ fibrils, are the major neurotoxic congeners in the AD brain.11, 12 Despite identification of oligomers as critical pathogenic forms of Aβ aggregates, uncertainty concerning oligomer structure, function, and formation persists due, in part, to the transient lifetimes of the early intermediates and the dynamic transition to thermodynamically favored fibrils.13–15 It is therefore important to characterize early events in the Aβ amyloid formation pathway and to correlate these events to cytotoxicity profiles in order to more fully understand the role of Aβ self-assembly in AD pathology.

Amyloid peptide self-assembly is a nucleation-dependent process that is defined by an initial lag phase preceding the formation of cross-β fibrils.16–19 During the lag phase, natively unfolded Aβ undergoes a chain reaction of association events that ultimately leads to the formation of cross-β fibrils.20 Aβ fibrils have been characterized using solid-state NMR and these structural models have been used to extrapolate structures that may be present in earlier intermediates.21–26 Several structural models for Aβ40 and Aβ42 cross-β fibrils have been reported; these models uniformly indicate the presence of a sheet-turn-sheet motif in the peptides within cross-β fibrils.15, 27–36 Tycko et al. have identified a turn motif between residues 24 and 27 in Aβ40 fibrils.23, 24,22 Riek et al. have proposed a model of Aβ42 fibrils with a turn comprising residues 26–30.28 Recently, Smith et al. have reported an Aβ42 fibril model with a turn spanning residues 24 to 27 in both oligomers and fibrils, consistent with the Tycko model.15 The precise structure of the turn region is unclear on the basis of these solid-state NMR studies. Formation of an α-helical intermediate has been reported to precede formation of β-sheet secondary structures during Aβ self-assembly and a solution structure of a stabilized Aβ α-helix has been reported to include a hinge between residues 24 and 27;37, 38 the location of the hinge corresponds to the turn region in fibril models, suggesting that turn nucleation may facilitate structural transitions from α-helix to β-sheet during Aβ self-assembly.

Turn nucleation has been proposed to be a rate-limiting step in Aβ self-assembly.39 Turn nucleation has been probed by creation of a lactam heterocyclic variant of Aβ in which the putative turn region of Aβ is constrained by a lactam ring formed by the D23 and K28 side chains; this variant exhibited abbreviated lag times for fibril self-assembly.39 Additionally, a β-hairpin conformer of Aβ has been stabilized by binding to an affibody ligand; this β-hairpin conformation has been proposed to be an early Aβ folding intermediate leading to fibrils.40 Collectively, this data implies that β-turn formation, and in particular β-hairpin formation, could be a rate-limiting step in Aβ fibril self-assembly. Turn formation is of particular interest since single point mutations in the turn region, including the E22G Arctic mutant, the D23N Iowa mutant and the ΔE22 Japanese mutant, among others, lead to aberrant folding of Aβ and are associated with early onset familial AD.25, 41, 42 While the origin of these increased toxicities remains unclear, a potential role for turn nucleation exists due to the proximity of these mutations to the reported turn region. A detailed functional probe of the role of turn formation in Aβ self-assembly will facilitate greater understanding of the mechanistic basis for Aβ amyloid formation and may inform strategies for perturbation of these processes.

Herein, we report the effect of incorporation of d-ProGly (DPG) mutations throughout the putative turn region of Aβ40 on the kinetics and thermodynamics of self-assembly and how these effects correlate to cytotoxicity. DPG, an efficient type II′ β-hairpin nucleator,43 was placed at three positions (24–25, 25–26, 26–27) throughout the turn region to investigate the positional effects of turn nucleation on self-assembly. Chen et al. have previously shown that DPG at positions 24–25 (Val 24 → DPro Aβ40) results in thermodynamic destabilization of the resulting fibril aggregates relative to the wild-type peptide.44 The studies reported herein complement Chen’s work by kinetically and thermodynamically characterizing the positional effect of DPG turn nucleation throughout the putative turn region in order to gain insight into 1) a possible role for β-hairpin formation early in Aβ self-assembly processes, 2) how the position of turn nucleation relative to formation of the D23/K28 salt bridge influences Aβ self-assembly, and 3) how turn nucleation correlates to cytotoxicity of the resulting aggregate species. We found that including a turn motif between residues 24 and 27 of Aβ40 generally enhanced the rate of selfassembly relative to wild-type, with the DPG-25,26 and DPG-26,27 variants forming fibrils without an apparent lag phase; the DPG-24,25 variant forms fibrils at a moderately faster rate than wild-type. The DPG-25,26 and DPG-26,27 variants formed fibrils with similar thermodynamic stability to the wild-type peptide, while the DPG-24,25 mutant was significantly thermodynamically destabilized. Neurotoxicity of the DPG variants was attenuated compared to wild-type, which is consistent with reduced lifetimes of neurotoxic oligomers as a function of more rapid fibril formation. These results are consistent with a prominent role for turn nucleation as an early step in Aβ self-assembly.

Results

Rationale and Design

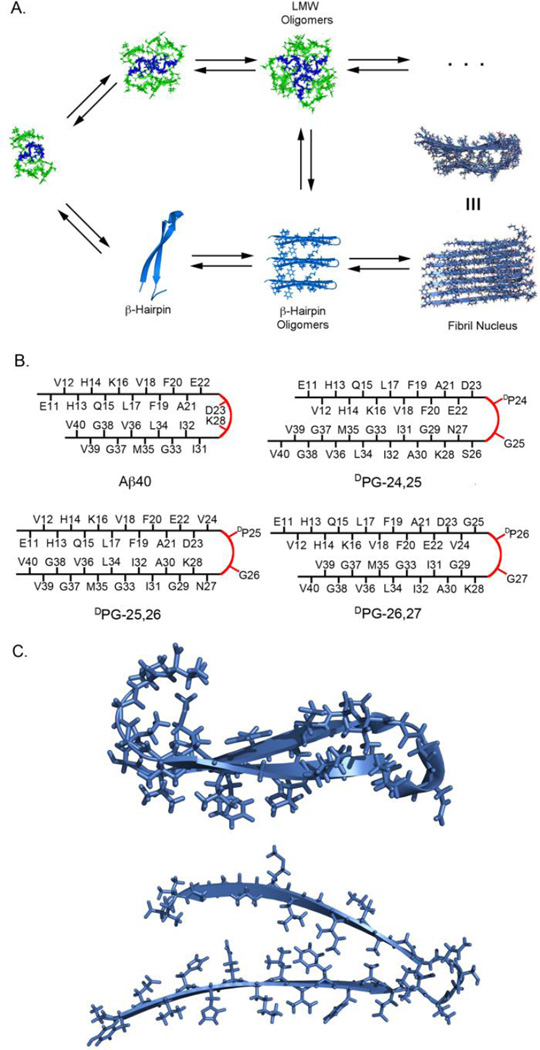

It has been hypothesized that turn formation is a potential rate-limiting step in Aβ self-assembly. 39 Recently, Aβ bound to an affibody was found to adopt a β-hairpin structure and it was hypothesized that a β-hairpin might be an early intermediate in the fibril nucleation pathway (Figure 1A).40 Spectroscopic analysis of early events in Aβ self-assembly indicates the transient formation of an extended β-hairpin structure;30 it has been proposed that the N- and C-terminal β-strands proximal to the turn in low order aggregates of this transient β-hairpin undergo a 90° rotation providing the observed parallel alignment of the Aβ sheet-turn-sheet motif within cross-β fibrils (Figure 1C).23 The incorporation of DPG throughout the turn region of Aβ facilitates kinetic, thermodynamic, and cytotoxicity studies to understand the functional consequences of β-hairpin formation and possible positional effects within the broadly defined turn region spanning residues 24–27 without relying on covalent cross-linking.

Figure 1.

A. Schematic of major events and potential intermediates in amyloid-β self-assembly. These intermediate conformations feature a turn between residues 23 and 28. B. Cross-strand registry in Aβ40 (based on published fibril structures derived by solid-state NMR) and proposed strand alignment based on DPG nucleation at various positions throughout the proposed turn region spanning residues 24–27. C. NMR-derived structures of the turn region in Aβ hairpin stabilized by the ZAb affibody (top) and Aβ40 fibril structure (bottom).23, 40

The role of turn nucleation was assessed by systematically replacing two-residue sequences within the 24–27 region of Aβ40 as indicated in Table 1 and Figure 1B. Aβ40 is less prone to aggregation than Aβ42 and was thus chosen as the preferred model sequence to facilitate accurate quantification of kinetic and thermodynamic effects of DPG incorporation. DPG is a dipeptide turn nucleator that strongly favors the formation of a type II′ β-turn.43, 45, 46 While DPG favors β-turn formation, it does not prohibit peptides from adopting alternative conformations. Thus, once β-hairpin formation occurs, the peptide chains proximal to a DPG turn in Aβ can rotate 90° to form the parallel β-sheets observed in wild-type fibrils. We predicted β-hairpin strand alignment as a function of DPG position (Figure 1B); based on these proposed alignments we hypothesized that self-assembly rate would be most accelerated for the DPG-25,26 peptide since the hairpin positions the D23 and K28 side chains in a cross-strand alignment, facilitating formation of the salt bridge that has been observed in Aβ fibril models.23, 28 If turn nucleation that leads to fibril formation is position sensitive, then self-assembly of the DPG-24,25 or DPG-26,27 variants may be less efficient, since proper strand alignment may require more time to sample assembly-competent conformations. The DPG analysis of the putative turn region reported herein provides fundamental understanding of a possible role for β-hairpin formation along the Aβ self-assembly pathway to cross-β fibrils and structural insight into the possible nature of the hairpin nucleation site. Correlation of self-assembly characteristics to cytotoxicity also provides insight into the effect turn nucleation has on the formation of neurotoxic oligomer species.

Table 1.

Aβ40 and Aβ40 DPG variant peptides.

| Peptide | Sequence | Substitution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | wild-type | - |

| 2 | DPG-24,25 | Val24, Gly25 → DPG |

| 3 | DPG-25,26 | Gly25, Ser26 → DPG |

| 4 | DPG-26,27 | Ser26, Asn27 → DPG |

Kinetic analysis of Aβ variant self-assembly

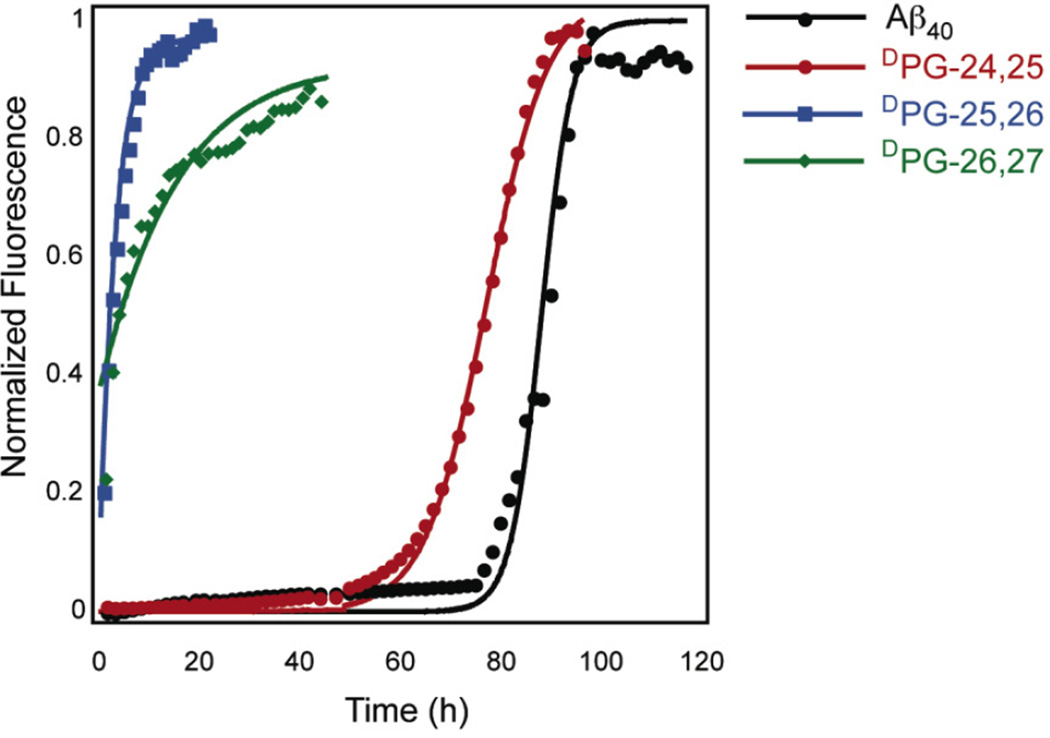

The influence of turn nucleation on the rate of self-assembly for the Aβ variants was monitored by ThT fluorescence assay. ThT is a fluorescent benzothiazole that binds selectively to amyloid fibrils and undergoes a red shift in its emission spectrum when bound, making it a useful fluorophore to measure the kinetics of fibril formation.47 Kinetics of self-assembly were monitored at 100 µM freshly disaggregated peptide.48 This concentration was chosen to ensure self-assembly of Aβ and the DPG variants in a convenient time frame. Aβ self-assembly is a nucleation-dependent process in which an initial lag phase precedes exponential fibril growth. During the lag phase, Aβ undergoes conformational transitions leading to fibril nucleus formation after which exponential fibril elongation occurs.49 The lag time (equation 2, Materials and Methods) that precedes the exponential increase in ThT fluorescence at 485 nm is an indication of the nucleation rate. Elongation rates can be inferred by comparing apparent pseudofirst order rate constants, k (equation 3, Materials and Methods). The time at which the fluorescence at 485 nm is half the maximal value, t1/2, is a reflection of both the nucleation and elongation rates. It has been shown that fragmentation plays a role in fibril nucleation through secondary nucleation by breakage of fibrils.50 d-ProGly mutations could potentially disturb the fibrils, leading to increased fibril breakage and faster fibrillization kinetics. While models that more accurately describe nucleation and elongation as a function of fibril breakage may more fully explain the mechanistic effects of DPG incorporation, we have opted to use a more simplified mechanistic approach that focuses on the relative effects that the reported DPG mutations have on the rates of self-assembly.

The rate of self-assembly was accelerated relative to wild-type for all DPG variants of Aβ40 (Figure 2, Table 2). The lag times and t1/2 for self-assembly of the peptides under consideration decreased in the order Aβ40 > DPG-24,25 > DPG-26,27 ≈ DPG-25,26; no apparent lag time was observed for the DPG-25,26 and DPG-26,27 variants. These results confirm that predisposing the 24–27 region to turn nucleation favors the formation of Aβ fibrils; these findings are consistent with turn nucleation as a rate-limiting step in Aβ self-assembly. It is interesting that the DPG-25,26 and DPG-26,27 variants exhibited no observable lag phase. It was expected that self-assembly of the DPG-25,26 variant would be dramatically accelerated due to its predicted strand alignment, which enables formation of a D23/K28 salt bridge. It should be noted, however, that D23/K28 salt bridge formation may be an intermolecular phenomenon (that is, the salt bridge may actually form between D23 and K28 on neighboring peptides within the fibril), so intramolecular D23/K28 alignment may not be relevant in predicting kinetics of selfassembly.23 The lack of a lag phase for DPG-26,27 self-assembly and the 71 h lag phase for DPG-24,25 self-assembly indicate that there is a positional sensitivity for turn nucleation leading to fibril formation in the 25–27 region of Aβ. The presence of a long lag phase in the DPG-24,25 variant is consistent with previous observations with this specific variant; Chen, et al. have reported high critical concentration and aberrant fibril morphology for fibrils derived from this peptide compared to wild-type Aβ.

Figure 2.

Normalized thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence analysis of Aβ40 and DPG Aβ variant peptide fibril formation. Peptide stock solutions were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (25 µM ThT, pH 7.4) and incubated at room temperature.

Table 2.

Experimental kinetic and thermodynamic parameters for Aβ40 and Aβ40 DPG variant fibril self-assembly.

| Kinetic effects | Thermodynamic effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | t1/2 | k (h−1) | lag time (h) | Cr (µM) | ΔG (kcal mol−1) [kJ/mol] |

ΔΔG (kcal mol−1) [kJ/mol] |

| wild-type | 91 ± 7 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 83 ± 7 | 5.7 ± 2.3 | −7.2 ± 0.2 [−30 ± 1] |

- |

| DPG-24,25 | 71 ± 8 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 60 ± 7 | 51.7 ± 1.8 | −5.8 ± 0.1 [−24 ± 1] |

1.4 ± 0.1 [6 ± 1] |

| DPG-25,26 | < 10 ha | - | - | 9.3 ± 2.0 | −6.9 ± 0.1 [−29 ± 1] |

0.3 ± 0.1 [1 ± 1] |

| DPG-26,27 | < 20 ha | - | - | 18.0 ± 1.7 | −6.5 ± 0.1 [−27 ± 1] |

0.7 ± 0.1 [3 ± 1] |

Data could not be fit to a sigmoid equation because there was no observable lag phase; t1/2 was approximated as the time at which ThT emission reaches half the maximal value.

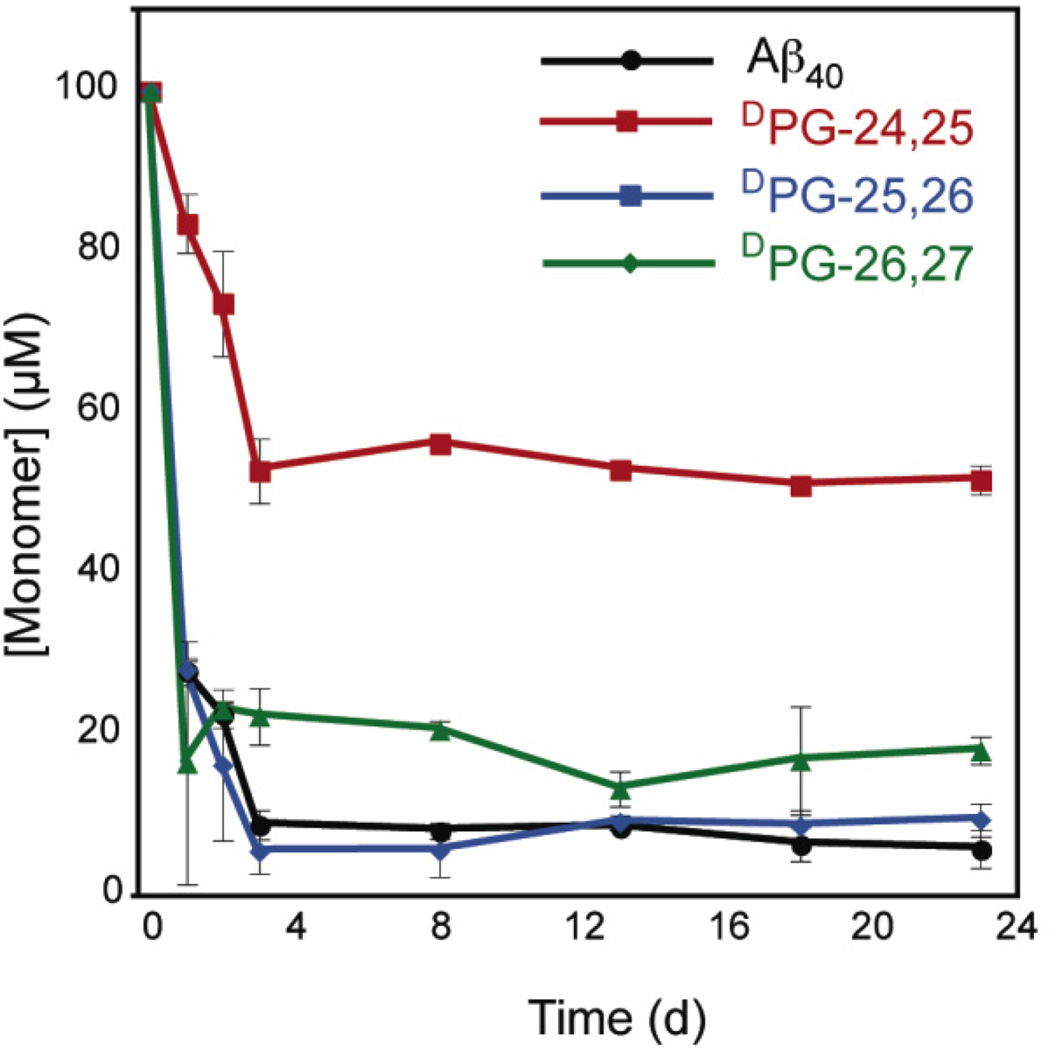

The influence of turn position on fibril thermodynamic stability

The relative thermodynamic effect of turn position was assessed using an HPLC sedimentation assay (See Materials and Methods).48 At equilibrium, fibril and monomer exist in dynamic equilibrium reflected by the expression fibriln + monomer ↔ fibriln+1. The fibril critical concentration, Cr, is related to the association constant Ka for the addition of one molecule of monomer to fibril by equation 4 (Materials and Methods).48 It should be noted that centrifugation may not be able to separate fibril and higher order oligmer species from lower-order non-fibrillar aggregates (dimer, trimer, etc.). Further, amorphous aggregates may represent a common intermediate during the complex folding pathway of Aβ variants;44 these aggregates would be indistinguishable from cross-β fibrils during centrifugation. Nevertheless, this sedimentation HPLC assay has become a standard technique to approximate fibril stability.48, 51 An expression of fibril thermodynamic stability, ΔG, can be determined using Ka. Critical concentrations (Cr) for each Aβ variant were determined by following changes in monomer concentration over time (Figure 3). From these Cr values, the free energy of association, ΔG, was determined relative to Aβ40 (Table 2). The order of fibril stability decreased in the order DPG-25,26 ≈ Aβ40 > DPG-26,27 >> DPG-24,25.

Figure 3.

HPLC sedimentation analysis of fibril formation of Aβ40 and Aβ40 DPG variant peptides. Disaggregated peptide stock solutions were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and incubated at room temperature prior to sedimentation analysis. Note that the x-axis is displayed as units of days, not hours.

Our thermodynamic analysis mirrored the kinetic rates of self-assembly; DPG-26,27 and DPG-25,26 sedimented immediately to equilibrium values within the first day. Aβ40 and DPG-24,25 formed sedimenatable aggregates within the first day, but only after three days did the monomer concentration drop to an asymptotic value. This initial drop in monomer concentration that precedes ThT responses has previously been attributed to the formation of pre-fibril oligomers in Aβ40, which accounts for the observed lag times in Aβ40 and DPG-24,25 ThT kinetics that are not observed during sedimentation. Based on our models of the predicted DPG hairpin alignment (Figure 1B), it was not surprising that DPG-25,26 was of comparable stability to wild-type Aβ40 since the predicted strand alignments are similar. The DPG-26,27 variant was less stable than Aβ40 by only 0.7 kcal. Previous studies have found that mutations of the salt bridge residues D23/K28 reduce fibril stability by < 1 kcal mol−1; the subtle difference in stability between the DPG-26,27 and DPG-25,26 variants and the wild-type peptide may therefore be due to perturbation of salt bridge formation. The DPG-24,25 variant had the highest Cr (51.7 µM) corresponding to the lowest fibril stability (ΔΔG = 1.4 kcal mol−1 relative to wild-type).52, 53 This large disparity in ΔG cannot be attributed to the lack of D23/K28 alignment alone and may represent a position sensitivity to turn formation or hydrophobic side chain effects as a result of Val 24/Gly 25 replacement with DProGly. Notably, Val 24 is the most hydrophobic amino acid replaced in this analysis. Chen et al. have reported a Cr of 29.44 µM for this peptide;44 the difference in Cr between Chen’s report and our work is most likely due to differences in solvent composition. Our fibril samples contain a final DMSO concentration of 5%, which has a destabilizing effect on fibril stability. Therefore, our results are consistent with Chen’s finding that DPG incorporation at position 24,25 of Aβ40 is destabilizing.

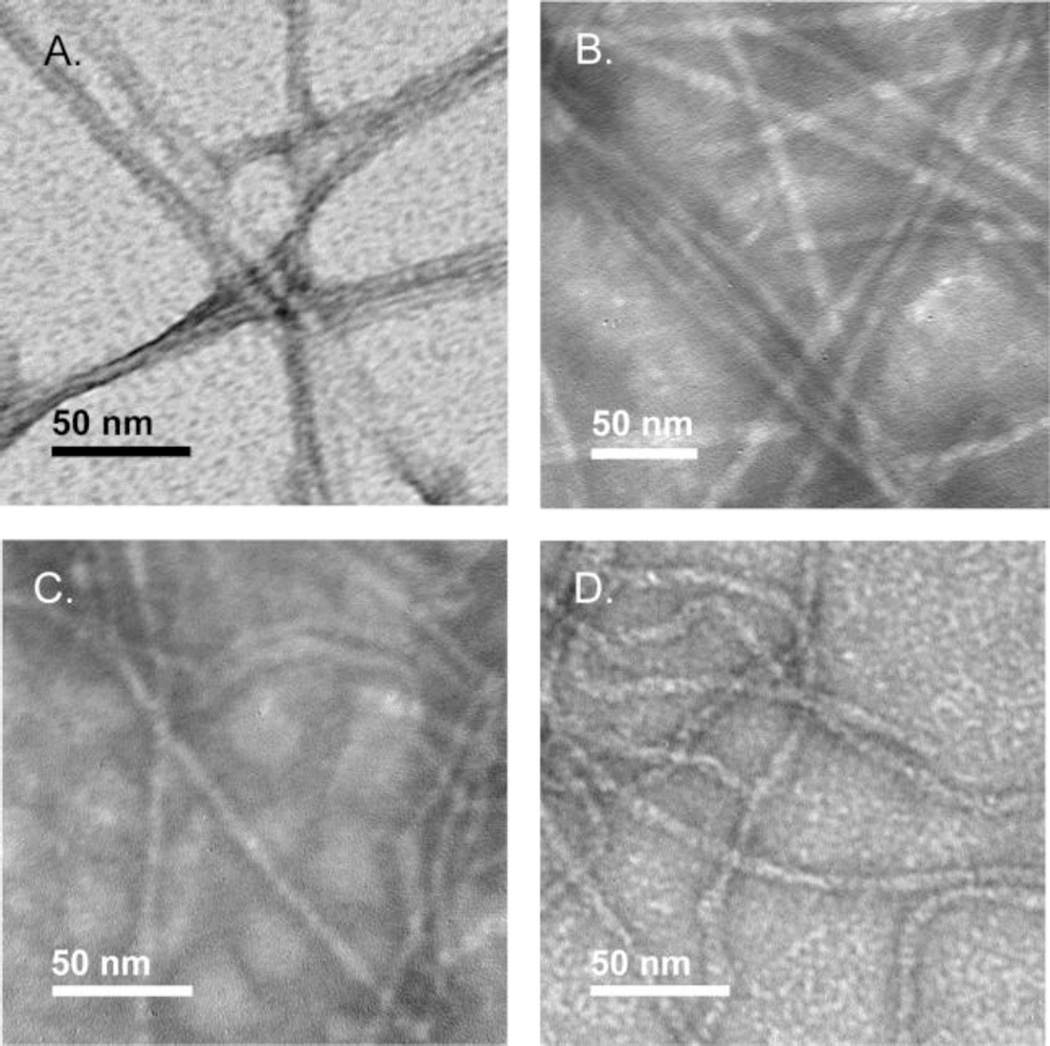

The effects of turn formation on cross-β fibril morphology

Negative stain transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to image the amyloid fibrils derived from Aβ40 and the DPG variants (Figure 4). Aβ40 and DPG-24,25 were morphologically similar; both peptides formed striated ribbons with diameters of 7.4 ± 1.5 nm and 8.2 ± 2 nm respectively. Fibrils derived from DPG-25,26 and DPG-26,27 adopted visually distinctive, more flexible morphologies relative to wild-type fibrils, although the fibrils had similar dimensions. Fibrils derived from DPG-25,26 and DPG-26,27 had fibril diameters of 6.9 ± 1 nm and 7.6 ± 1 nm respectively. Flexible morphologies have been previously observed in Aβ variants that form fibrils without a lag phase.42, 54

Figure 4.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of fibrils formed by A. Aβ40; B. DPG-24,25; C. DPG-25,26; D. DPG-26,27.

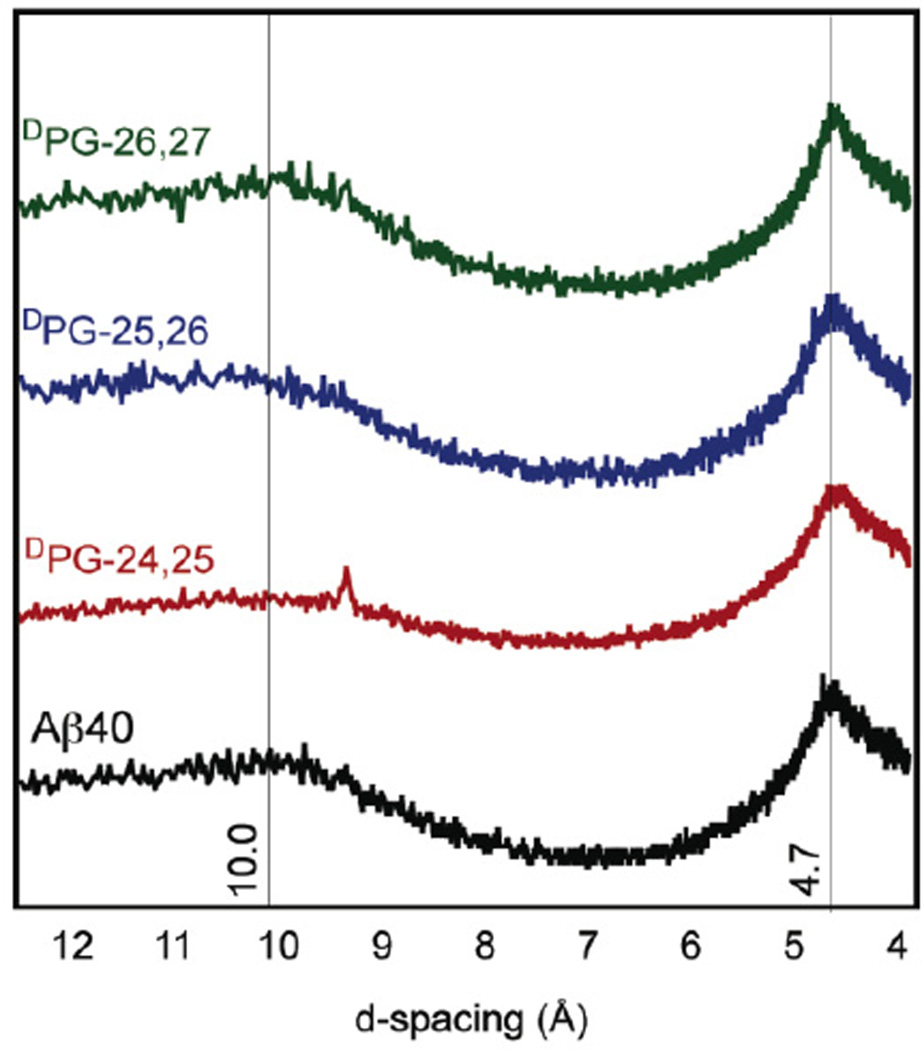

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirmed that the fibrils observed by electron microscopy were consistent with a cross-β morphology. Cross-β structures exhibit characteristic scattering patterns in X-ray diffraction experiments that include strand-strand distances of 4.7 Å and sheet-sheet lamination distances of ~10 Å.55 Fibril d-spacing values were calculated from scattering patterns (Figure 5). A d-spacing of 4.7 Å was observed for all variant fibrils, consistent with formation of β-sheet structures. A spacing of ~10 Å confirmed a cross-β morphology within the peptide variant fibrils. Electron diffraction was also used to confirm fibril β-sheet structure. Electron diffraction can be conveniently conducted directly on fibrils deposited on TEM grids. All variants exhibited a d-spacing of 4.7 ± 0.1 Å, consistent with β-sheet secondary structure (Figures S9–S13).

Figure 5.

X-ray diffraction d-spacings obtained from fibrils derived from Aβ40 and Aβ40 DPG variants.

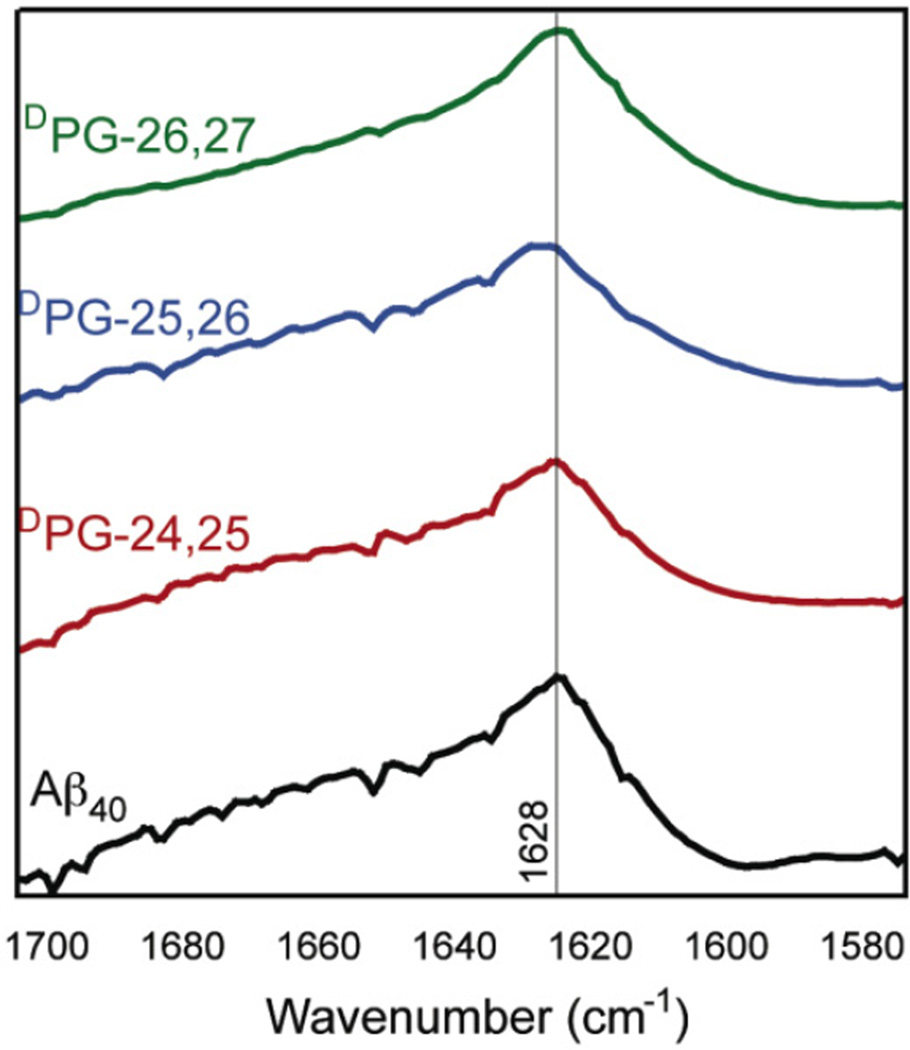

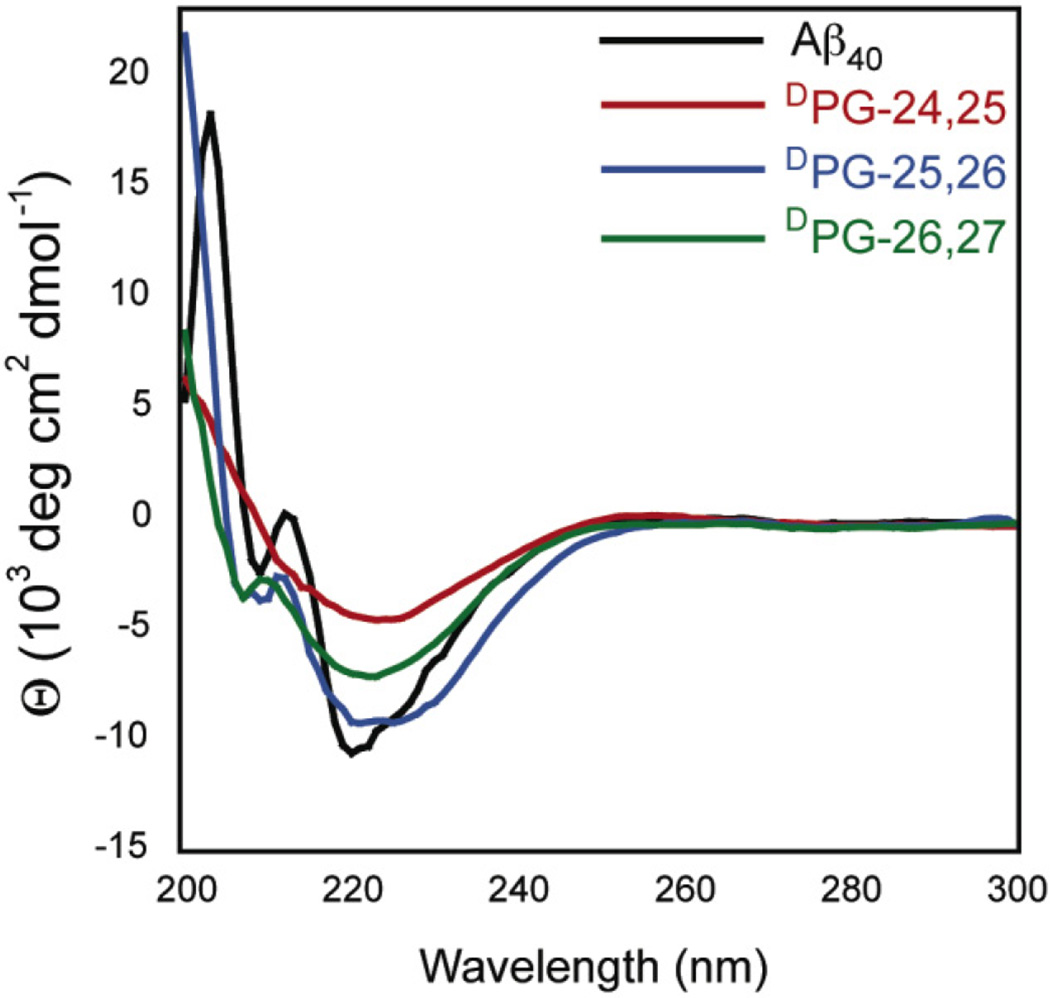

Fibril structure was further investigated using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Aβ40 displays a characteristic IR amide I stretch at ~1630 cm−1, consistent with the formation of a β-sheet, and a broad stretch from 1640–1700 cm−1 which has been attributed to amide I stretches throughout the turn region of the Aβ peptide in the context of cross-β fibrils.57, 58 Fibrils from all variants were collected by sedimentation, frozen and lyophilized, and characterized by FT-IR in the solid state (Figure 6). All the variants displayed a characteristic maximum intensity at 1628 ± 2, consistent with a cross-β morphology. The variant fibrils also exhibited a broad stretch from 1640–1700 cm−1 similar to that found in wild-type Aβ40 fibrils. Further secondary structure characterization was conducted using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Aβ fibrils exhibit a characteristic minimum at 218 nm in CD spectra consistent with β-sheet secondary structures.59 CD spectra were obtained of fibril mixtures for each of the Aβ variants (Figure 7). These results are consistent with DPG variant peptides forming fibrils that are similar to those formed by Aβ40 in terms of molecular packing and secondary structure even though the fibrils do not appear to be visually identical in morphology. It should be noted that a CD signal at ~ 210 nm is observed for Aβ40, and the DPG-25,26 and DPG-26,27 variants. We attribute this peak to a population of soluble α-helical intermediates that result because CD spectroscopy is used to determine the secondary structure of soluble sample components, and not insoluble, β-sheet fibrils. The absence of this peak in the DPG-24,25 sample indicates that the population of soluble intermediates is different from the other variants, and may self-assemble by a different folding mechanism.

Figure 6.

FT-IR spectra of Aβ40 and Aβ40 DPG variant fibrils.

Figure 7.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of Aβ40 and Aβ40 DPG variant fibril solutions.

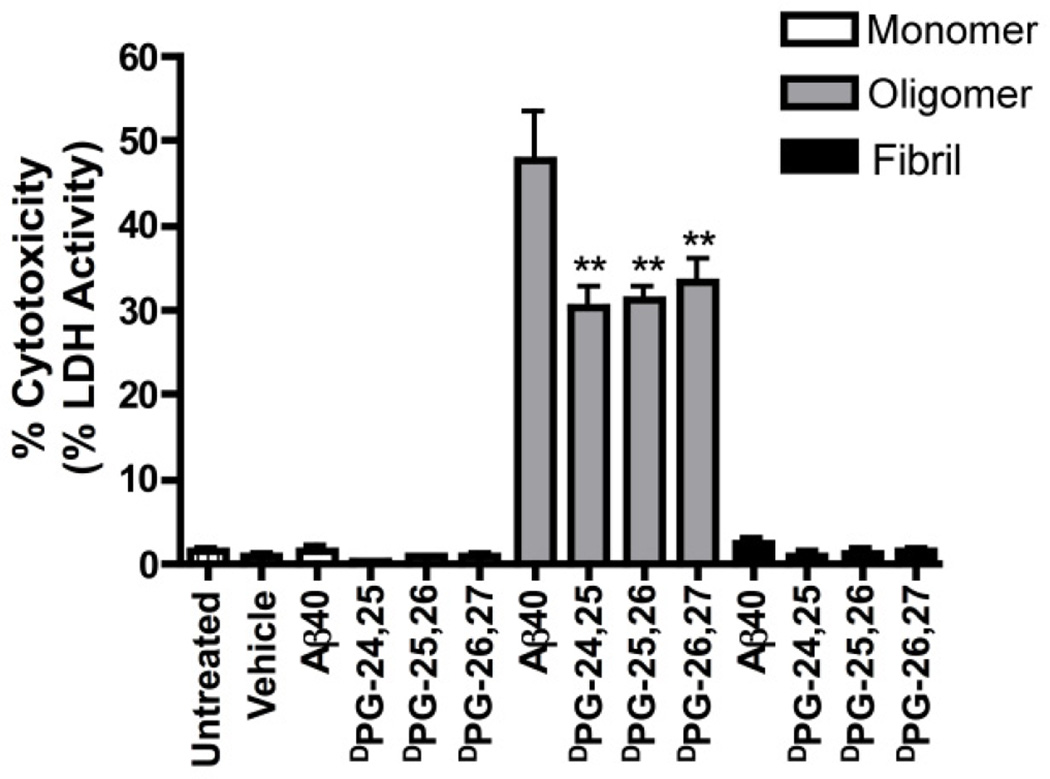

Effect of turn nucleation on aggregate cytotoxicity

The neurotoxicity of aggregates of each Aβ40 variant was also characterized. C17.2 neural precursor cells were exposed to Aβ peptides that were freshly disaggregated (monomeric), or that had been incubated under conditions that favor the formation of either oligomers (4 °C) or fibrils (37 °C) (Figure 8).60, 61 Cytotoxicity was determined by measuring the activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) that leaks into the growth medium upon membrane permeabilization that occurs after cell death. Addition of monomer and mature fibril to the cell culture medium (1 µM Aβ) had a minimal effect on cell viability for all variants. As expected, freshly disaggregated Aβ monomer was not cytotoxic.60–62 Similarly, fibrils exhibited relatively low cytotoxicity, although this may be due to sedimentation of insoluble fibrils during incubation with cells and might not truly reflect the toxicity of fibrils; however, low toxicity of fibrils has been frequently reported in the literature and our results are consistent with these observations.14

Figure 8.

Cytotoxicity profiles of C17.2 neural progenitor cells after exposure to: 1) freshly disaggregated Aβ40 and Aβ40 DPG variants (monomer); 2) Aβ40 and Aβ40 DPG variants grown under conditions that favor the formation of oligomers (oligomer); 3) Aged Aβ40 and Aβ40 DPG variants grown under conditions that favor the formation of fibrils (fibril).

Conversely, oligomer species were highly toxic. Oligomers derived from wild-type Aβ40 exhibited 48 ± 6% cytotoxicity by LDH activity relative to detergent controls; oligomers of the DPG variants were less toxic than wild-type oligomers by ~30%, but the variants displayed similar cytotoxicity to each other regardless of the position of DPG incorporation. It has been established that Aβ40 oligomers are highly cytotoxic;11, 12, 62, 63 it has been shown, however, that increasing the rate of fibril formation can lead to significantly lower toxicity for aggregates of Aβ, strengthening the argument that oligomers, and not fibrils, are the main toxic congeners of Aβ .64 Based on this precedent, we hypothesized that rapidly fibrillizing DPG variants would be significantly less toxic than wild-type Aβ40 since oligomer populations may be rapidly depleted; it was posited that variants that formed fibrils without a lag phase may even be nontoxic since oligomer populations might be practically nonexistent. While oligomers of DPG variants were significantly less cytotoxic than wild-type peptides, they were still considerably toxic. This finding implies that turn nucleation is a feature of oligomer formation as well as fibril formation.15 It should be noted that incorporation of a d-ProGly hairpin motif is not a functionally conservative mutation and substitution of native functional groups in the DPG variants may have an effect on the cytotoxicity of resulting oligomers.

Discussion

Mechanistically, fibril nucleation is proposed to occur through a general hydrophobic collapse resulting in the formation of an intermolecular molten globule.18, 19, 65 Evidence suggests that during fibril nucleation, turn formation plays a significant structural role in the equilibrium leading to fibrils (Figure 1, pathway B).27, 40, 54 Sandberg, et al. have recently proposed a two-pathway model for Aβ self-assembly in which fibril nucleation occurs through a β-sheet rich pathway.66 Lasagna-Reeves et al. have proposed a similar mechanism of fibril nucleation in which turn formation has been hypothesized to occur prior to hydrophobic collapse. In this case, β-turn formation would likely pre-align the N- and C-termini in an antiparallel β-sheet arrangement to form a β-hairpin that promotes aggregation and nucleates fibril formation, thereby representing a rate-limiting step in Aβ self-assembly.

Evidence supports the presence of an early β-hairpin intermediate as represented in folding pathway B. NMR structures of an Aβ β-hairpin intermediate stabilized by an affibody ligand shows a β-hairpin localized between G25 and K28, indicating that Aβ can exist in a hairpin conformation.40 Additionally, structures of α-helical Aβ intermediates indicate a bend located between residues S26 and N27. Taken together, these structural models suggest that turn formation in this region occurs prior to β-sheet formation along a common pathway. Sciarretta et al. showed that nucleation of a turn by forming a D23/K28 lactam in Aβ40 accelerated self-assembly, indicating that turn formation could represent a rate-limiting step. Caution must be exercised in interpreting the lactam and disulfide variant results in the context of β-hairpin formation, however, since covalent modification undoubtedly limits the conformations that can be sampled leading to hairpin structures; this conformational restriction may ultimately perturb the pathways leading to self-assembly. Recent work by Chen et al. shows that turn nucleation by DPG incorporation at position 24/25 destabilizes the resulting aggregates thermodynamically; these results indicate that β-hairpin nucleation of the monomeric peptide perturbs the selfassembly pathway.44 Given this recent evidence that a β-hairpin intermediate may exist during fibrillogenesis, the role of β-hairpin formation on Aβ fibril self-assembly has not been thoroughly addressed in terms of position of turn nucleation. The possible role of turn nucleation in the formation of cytotoxic prefibrillar oligomers has also not been thoroughly characterized.

Our findings are consistent with turn formation as an early, rate-limiting event in Aβ fibrillization. This conclusion is based on the accelerated rates of fibrillization for the DPG-25,26 and DPG-26,27 variants while the DPG-24,25 variant assembles at a similar rate to the wild-type peptide. The lack of a significant lag phase in the self-assembly of the DPG-25,26 and DPG-26,27 variants suggests that turn formation occurs before (perhaps contributing to) oligomerization in these variants; this observation is in good agreement with the mechanistic model proposed by Sandberg et al. suggesting that β-hairpin formation occurs before hydrophobic collapse along the fibril pathway.66 Our results are consistent with turn formation, particularly in the segment in which the turn is indicated by solid-state NMR studies, as promoting more rapid formation of Aβ40 aggregates.23, 24 As suggested by Smith et al., our results suggest that an early β-hairpin intermediate may promote hydrophobic collapse and oligomerization; rotation of the β-strands within the hairpin oligomer structures to non-hairpin cross-β morphologies results in nucleation of cross-β fibril seeds.15 Unfortunately, our data does not unequivocally indicate the presence of a distinct β-hairpin structure. If such a β-hairpin intermediate does exist, it may be extremely short-lived and other methods must be leveraged to directly detect it. At best, we can conclude that the incorporation of DPG β-turn nucleators in the turn region of Aβ promotes more rapid self-assembly in a position dependent manner.

Functional cytotoxicity data in which Aβ DPG variants were cytotoxic under conditions that favor stabilization of oligomers also provides interesting commentary on the role of turn nucleation in the formation of prefibrillar aggregates. Despite an inherently higher propensity to self-assemble into fibrils, the DPG variants discussed herein still formed functionally cytotoxic aggregates albeit to a lesser degree than the wild-type peptide. Thus, oligomer structures also appear to feature turn structures. It should be noted that there has been significant debate about whether Aβ oligomers exist on- or off-pathway leading to fibrils;67 the data presented herein could be consistent with either possibility and additional studies that clarify the specific nature of oligomeric β-hairpin structures would be of great interest in this regard.

Identifying the major physicochemical determinants that drive amyloid peptide self-assembly is paramount to understanding the role of amyloid species in the pathophysiology of amyloid-related disorders. Herein, we have shown evidence that formation of an Aβ β-hairpin intermediate with the hairpin centered between residues 25 and 27 early in the folding pathway represents a rate-limiting step during fibrillogenesis. Aβ turn formation therefore represents a plausible target for antiamyloid therapeutics. Molecules that stabilize non-aggregating structures have been useful for inhibition of amyloid formation of structured amyloid proteins;68 while the development of ligands that have the same effect on a disordered peptide like Aβ is significantly more challenging, the identification of specific secondary structures that lead to self-assembly indicates that this may, in principle, be possible. A recent report that compares molecular simulation data for prefibrillar Aβ42 structures with solution state NMR indicates that characterization of Aβ as an intrinsically disordered peptide is an oversimplification.69 It was found that prefibrillar Aβ42 actually exists as an ensemble of many discrete secondary structures.69 Ligands that stabilize non-aggregating structural isoforms of Aβ would prevent assumption of aggregating conformations, including β-hairpin structures. Additional studies that explicitly determine the effect of stabilizing other secondary structures in prefibrillar Aβ will be of great interest in this regard.

Materials and Methods

Peptide synthesis and purification

Peptides synthesis was carried out on a CEM Liberty microwave-equipped peptide synthesizer using Fmoc solid-phase methodology with HBTU/HOBt activation. Peptide cleavages were performed by suspending the resin in TFA:TIS:H2O (95:2.5:2.5, v/v/v) for 2 h; the resulting free peptide was isolated by precipitation from diethyl ether. Peptides were purified by reverse-phase HPLC on a Shimadzu LC-AD HPLC with a C18 column (19 mm×250 mm; Waters, Milford, MA) using a linear gradient of acetonitrile and water (0.1% TFA) at 60 °C as a mobile phase. Eluent was monitored by UV absorption at 215 nm. Peptide purity and relative hydrophobicity was determined by analytical HPLC analysis using a reverse phase C4 column (Grace or Vydac) at 55°C (Figures S1–S4, Table S1 in the Supporting Information). The identity of the peptide was confirmed by MADLI-TOF MS (Figures S5–S8, Table S2).

Peptide disaggregation

A modified Wetzel protocol was used to disaggregate peptides prior to self-assembly studies.48 Lyophilized peptides were dissolved in TFA and sonicated for 10 min at room temperature. TFA was removed through evaporation under a gentle stream of dry nitrogen. The dried film was quickly dissolved in HFIP and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. HFIP was removed using dry nitrogen and the peptide was again dissolved in HFIP. Peptide concentration was determined from this HFIP solution by HPLC injection and correlation of the integrated peak area to a concentration curve calibrated by amino acid analysis (AIBiotech, Richmond, VA) (Figure S13). Peptides were then apportioned into individual low-bind centrifuge tubes to the desired amount. HFIP was removed and the peptides dried in vacuo for at least 1 h prior to dissolution in DMSO for self-assembly studies.

Kinetics of fibril self-assembly

Peptide self-assembly kinetics were characterized by a thioflavin-T (ThT) fluorescence assay. Fluorescence experiments were performed in a Tecan Infinite M1000 plate fluorimeter using 96-well clear bottom microtiter plates with excitation at 450 nm and emission monitored at 485 nm (10 nm bandwidth). Freshly disaggregated peptide was dissolved in DMSO (4 mM) and peptide concentration was confirmed by correlation of HPLC peak area to a standard concentration curve. DMSO stock solutions of peptide were diluted to 100 µM by addition of phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) containing 25 µM ThT. This solution was then added to a 96-well, non-binding microtiter plate and fluorescence was monitored. Fluorescence data was fit to the empirical sigmoid equation 1. y0 and ymax represent initial fluorescence and maximum, respectively; k is the apparent rate constant and t1/2 is the time when the fluorescence intensity reaches one-half the maximum value.70 Equation 2 was used to calculate lag time.70

| (1) |

| (2) |

Thermodynamic sedimentation analysis

Disaggregated peptides were dissolved in DMSO and diluted with phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4). Solutions were incubated at 25 °C under quiescent conditions. An aliquot was removed and centrifuged (14,000 × g, 1 h, 4 °C) to remove fibrillar aggregates every 24 h for the first three days and every 120 h thereafter. The amount of monomeric peptide in the supernatant was quantified by correlation to HPLC concentration curves. The concentration of monomer at endpoint defines the critical concentration, Cr, for the system; Cr is indicative of the dynamic equilibrium between fibril and monomer at endpoint (Ka) represented by the expression: fibriln + monomer ↔ fibriln+1 (equation 3).48 At equilibrium, Cr is inversely related to the association constant, Ka, for the growth of the fibril by a single monomer unit (equation 4).48 Ultracentrifugation has been shown to separate fibrils, amorphous aggregates and lower order aggregates from monomer. However, it should be noted that soluble low-order aggregates (dimer, trimer, and tetramer) may be present in the supernatant and that sedimentation protocols cannot accurately account for these species.

| (3) |

| (4) |

Fibril growth for TEM, X-ray diffraction, and FT-IR analysis

Disaggregated peptides were dissolved in DMSO (4 mM). Peptide concentration of DMSO solutions was determined by correlation of HPLC peak area to a standard concentration curve. DMSO solutions were diluted to 100 µM by addition of phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4). Peptides were incubated for 2 weeks and the resultant fibrils were used for Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), and negative-stain transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Negative stain transmission electron microscopy and electron diffraction

10 µL aliquots of mature fibril suspensions were applied to 200 mesh, carbon-coated copper grids. After 3 min, excess fluid was removed by capillary action. Residual salts and buffer were washed by application of 10 µL water for 10 s followed by removal by capillary action (repeated twice). The grids were then stained by applying 10 µL of 5% uranyl acetate for 5 min and removing the excess solvent by capillary action. The stained grids were air dried for at least 10 min prior to imaging. A Hitachi 7650 transmission electron microscope was used in high contrast mode with an accelerating voltage of 80 kV to obtain electron micrographs. Fibril width was determined by performing at least 100 measurements on unique fibrils for each peptide using the program ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).71 Electron diffraction experiments were performed on the TEM grids on a spot size of 30 nm and a camera length of 2 m. Diffraction profiles were obtained using the program imageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).71 Fibril d-spacings were calculated from the diffraction profile as previously described.56

X-ray powder diffraction

Mature fibrils were harvested by centrifugation and washed with water. The pellet was resuspended in water frozen, and lyophilized. Powder diffraction measurements were performed on a Bruker X8 APEX II X-ray diffractometer.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Mature fibrils were prepared as previously described. The sample was centrifuged to collect the fibrils. The resulting fibril pellets were washed with D2O, resuspended in a minimal amount of D2O, frozen, and lyophilized. The lyophilized fibril was loaded onto the ATR stage of a Shimadzu FTIR-8400S spectrometer and IR spectra were obtained at a resolution of 2 cm−1. IRSolution Data smoothing and a multipoint baseline correction were performed with IRSolution

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

Peptides were disaggregated using a modified Wetzel protocol.48 purified, lyophilized peptides were dissolved in TFA and sonicated for 10 min at room temperature; TFA was then evaporated under a gentle stream of dry nitrogen. The resulting material was immediately dissolved in HFIP and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. HFIP was then evaporated under a stream of nitrogen and the peptide was again dissolved in HFIP. DMSO cannot be present during CD spectrum collection. To avoid taking the peptide film up phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4), which could potentially lead to seeding, the HFIP solution was frozen and lyophilized. To initiate self-assembly, the lyophilized powder was dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) to a concentration of 100 µM. After 2 weeks, the CD spectrum was obtained for each variant on an Aviv CD Spectrophotometer. Spectra were obtained from 260–190 nm with a 1.0 nm step, 1.0 nm bandwidth, and a 3 s collection time per step at 25°C in a 0.1 cm path length quartz cuvette (Hellma). The AVIV software was used for background subtraction, conversion to molar ellipticity, and data smoothing with a least-squares fit.

Assessment of aggregate cytotoxicity

C17.2 Cell Culture

C17.2 neural precursor cells were maintained in DMEM cell culture media supplemented with phenol red, 5% horse serum (HS), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 4 mM LGlutamine, 1 mM pyruvate and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. Media was changed every 2–3 days. Cells were grown in culture dishes to subconfluence before analysis.

Lactate Dehydrogenase Release Assay

The percentage of extracellular lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage in the cell culture media served as a cytotoxicity indicator of the various Aβ peptides. This assay is based on the reduction of NAD+ by LDH and the conversion of pyruvate into lactate. The oxidation of NADH results in decreased absorbance at 340 nm and the rate of decrease in absorbance is directly proportional to LDH activity. C17.2 cells were first seeded overnight in 96-well plates (BD Falcon) at a density of 3×103 cells per well in feeding media. Cells were then exposed for 24 hours to a vehicle (DMSO) or 1 µM Aβ peptides prepared as monomer, oligomer or fibrils. For treatment with monomeric Aβ, freshly disaggregated Aβ was dissolved in DMSO, sterilized by filtration, diluted to 1 µM in phenol red- and serum-free DMEM media and immediately applied to cells. Oligomers were prepared as previously described by incubating Aβ in phenol red- and serum-free DMEM media overnight at 4°C (50 µM) and then diluting to 1 µM for application to cells.60, 61 Finally, 100 µM fibrils were prepared in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) for 1 week prior to dilution to 1 µM in phenol red- and serum-free DMEM media before addition to cells. 1% Triton X-100 was used as a positive control for total LDH release. Following the exposure period, 100µL of the cell culture media were collected and spun down at 4,000 rpm for 7 minutes at 4°C. LDH release was measured by a diode array spectrophotometer utilizing UV-Visible HP ChemStation software. LDH activity was calculated based on the µM extinction coefficient of NADH at 340nm and pH 7.5. The percentage of extracellular LDH release is expressed as the percentage of the total LDH released from the 1% Triton X-100 control.

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from a minimum of 3 independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed with 1-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) (GraphPad Prism 4.0). Analyses were considered significant when p < 0.05. Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to further analyze significant ANOVAs.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

β-Hairpin nucleation was modeled in Aβ using d-ProGly mutations in order to probe the influence of turn formation on Aβ amyloid self-assembly.

Incorporation of d-ProGly into the putative turn region of the Aβ peptide sequence (residues 24–27) enhanced cross-β amyloid self-assembly rates in a position-dependent manner.

Aggregates formed by Aβ variants containing d-ProGly were cytotoxic, but at lower levels than aggregates of the wild-type sequence.

These findings indicate turn nucleation is a relevant step in Aβ oligomer and fibril formation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Karen Bentley of the University of Rochester Medical Center Electron Microscope Research Core for assistance with transmission electron microscopy experiments. This work was supported by a DuPont Young Professor Award to B.L.N. and by the Alzheimer’s Association (NIRG-08-90797). This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health: No. P30ES01247 and T32ES07026 (to S.E.L. and L.A.O.). Mass spectroscopy instrumentation was partially supported by a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (CHE-0840410, CHE-0946653).

Abbreviations

- Aβ

Amyloid-β

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- DPG

d-ProGly

- LMW

low molecular weight

- Fmoc

9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HBTU

O-benzotriazole-N,N,N',N'-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate

- HOBt

hydroxybenzotriazole

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TIS

triisopropyl silane

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry

- HFIP

2-hexafluoroisopropanol

- ThT

thioflavin T

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- FT-IR

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors maybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer's Disease: Progress and Problems on the Road to Therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soto C. Unfolding the role of protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;4:49–60. doi: 10.1038/nrn1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiti F, Dobson CM. Protein Misfolding, Functional Amyloid, and Human Disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jakob-Roetne R, Jacobsen H. Alzheimer's Disease: From Pathology to Therapeutic Approaches. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3030–3059. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roychaudhuri R, Yang M, Hoshi MM, Teplow DB. Amyloid β-Protein Assembly and Alzheimer Disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:4749–4753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800036200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campioni S, Mannini B, Zampagni M, Pensalfini A, Parrini C, Evangelisti E, Relini A, Stefani M, Dobson CM, Cecchi C, Chiti F. A causative link between the structure of aberrant protein oligomers and their toxicity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:140–147. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ittner LM, Gotz J. Amyloid-β and tau - a toxic pas de deux in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;12:67–72. doi: 10.1038/nrn2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haass C, Schlossmacher MG, Hung AY, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Mellon A, Ostaszewski BL, Lieberburg I, Koo EH, Schenk D, Teplow DB, Selkoe DJ. Amyloid β-peptide is produced by cultured cells during normal metabolism. Nature. 1992;359:322–325. doi: 10.1038/359322a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Esch F, Lee M, Dovey H, Davis D, Sinha S, Schlossmacher M, Whaley J, Swindlehurst C, McCormack R, Wolfert R, Selkoe D, Lieberburg I, Schenk D. Isolation and quantification of soluble Alzheimer's β-peptide from biological fluids. Nature. 1992;359:325–327. doi: 10.1038/359325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoji M, Golde TE, Ghiso J, Cheung TT, Estus S, Shaffer LM, Cai X-D, McKay DM, Tintner R, Frangione B, Younkin SG. Production of the Alzheimer Amyloid β Protein by Normal Proteolytic Processing. Science. 1992;258:126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1439760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid-β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Aβ Oligomers — a decade of discovery. J. Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bucciantini M, Giannoni E, Chiti F, Baroni F, Formigli L, Zurdo J, Taddei N, Ramponi G, Dobson CM, Stefani M. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature. 2002;416:507–511. doi: 10.1038/416507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common Structure of Soluble Amyloid Oligomers Implies Common Mechanism of Pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed M, Davis J, Aucoin D, Sato T, Ahuja S, Aimoto S, Elliott JI, Sostrand WEV, Smith SO. Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-β(1–42) oligomers to fibrils. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:561–567. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly J. Mechanisms of amyloidogenecity. Nat. Struc. Biol. 2000;7:824–826. doi: 10.1038/82815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamley IW. Peptide Fibrillization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:8128–8147. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Senguen FT, Lee NR, Gu X, Ryan DM, Doran TM, Anderson EA, Nilsson BL. Probing aromatic, hydrophobic and steric effects on the self-assembly of an amyloid-β fragment peptide. Mol. BioSyst. 2011;7:486–496. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00080a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senguen FT, Doran TM, Anderson EA, Nilsson BL. Clarifying the influence of core amino acid hydrophobicity, secondary structure propensity, and molecular volume on amyloid-β 16–22 self-assembly. Mol. BioSyst. 2011;7:497–510. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00210k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang S, Iwata K, Lachenmann MJ, Peng JW, Li S, Stimson ER, Lu Y-a, Felix AM, Maggio JE, Lee JP. The Alzheimer's Peptide Aβ Adopts a Collapsed Coil Structure in Water. J. Struct. Biol. 2000;130:130–141. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balbach JJ, Petkova AT, Oyler NA, Antzutkin ON, Gordon DJ, Meredith SC, Tycko R. Supramolecular Structure in Full-Length Alzheimer's β-Amyloid Fibrils: Evidence for a Parallel β-Sheet Organization from Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1205–1216. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petkova AT, Leapman RD, Guo Z, Yau W-M, Mattson MP, Tycko R. Self-Propagating, Molecular-Level Polymorphism in Alzheimer's β-Amyloid Fibrils. Science. 2005;307:262–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1105850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petkova AT, Yau W-M, Tycko R. Experimental Constraints on Quaternary Structure in Alzheimer's β-Amyloid Fibrils. Biochemistry. 2006;45:498–512. doi: 10.1021/bi051952q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paravastu AK, Leapman RD, Yau W-M, Tycko R. Molecular structural basis for polymorphism in Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:18349–18354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tycko R, Sciaretta KL, Orgel JPRO, Meredith SC. Evidence for Novel β-Sheet Structures in Iowa Mutant β-Amyloid Fibrils. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6072–6084. doi: 10.1021/bi9002666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tycko R. Solid-State NMR Studies of Amyloid Fibril Structure. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2011;62:279–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazo ND, Grant MA, Condron MC, Rigby AC, Teplow DB. On the nucleation of amyloid β-protein monomer folding. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1581–1596. doi: 10.1110/ps.041292205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lührs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Döbeli H, Schubert D, Riek R. 3D structure of Alzheimer's amyloid-β(1–42) fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 2005;102:17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whittemore NA, Mishra R, Kheterpal I, Williams AD, Wetzel R, Serpersu EH. Hydrogen-Deuterium (H/D) Exchange Mapping of Aβ(1–40) Amyloid Fibril Secondary Structure Using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4434–4441. doi: 10.1021/bi048292u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Habicht G, Haupt C, Friedrich RP, Hortschansky P, Sachse C, Meinhardt J, Wieligmann K, Gellermann GP, Brodhun M, Götz J, Halbhuber K-J, Röcken C, Horn U, Fändrich M. Directed selection of a conformational antibody domain that prevents mature amyloid fibril formation by stabilizing Aβ protofibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:19232–19237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703793104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sgourakis NG, Yan Y, McCallum SA, Wang C, Garcia AE. The Alzheimer's Peptides Aβ40 and 42 Adopt Distinct Conformations in Water: A Combined MD/NMR Study. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;368:1448–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y, Derreumaux P, Guo Z, Mousseau N, Wei G. Thermodynamics and dynamics of amyloid peptide oligomerization are sequence dependent. Proteins. 2008;75:954–963. doi: 10.1002/prot.22305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerf E, Sarroukh R, Tamamizu-Kato S, Breydo L, Derclaye S, Dufrene YF, Narayanaswami V, Goormaghtigh E, Ruysschaert J-M, Raussens V. Antiparallel β-sheet: a signature structure of the oligomeric amyloid β-peptide. Biochem. J. 2009;421:415–423. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu L, Edalji R, Harlan JE, Holzman TF, Lopez AP, Labkovsky B, Hillen H, Barghorn S, Ebert U, Richardson PL, Miesbauer L, Solomon L, Bartley D, Walter K, Johnson RW, Hajduk PJ, Olejniczak ET. Structural Characterization of a Soluble Amyloid β-Peptide Oligomer. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1870–1877. doi: 10.1021/bi802046n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitternacht S, Staneva I, Härd T, Irbäck A. Comparing the folding free-energy landscapes of Aβ42 variants with different aggregation properties. Proteins. 2010;78:2600–2608. doi: 10.1002/prot.22775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertini I, Gonelli L, Luchinat C, Mao J, Nesi A. A New Structural Model of Aβ40 Fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011 doi: 10.1021/ja2035859. Just Accepted Manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crescenzi O, Tomaselli S, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, D'Ursi AM, Temussi PA, Picone D. Solution structure of the Alzheimer amyloid β-peptide (1–42) in an apolar microenvironment. Eur. J.Biochem. 2002;269:5642–5648. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomaselli S, Esposito V, Vangone P, Nuland NAJv, Bonvin AMJJ, Guerrini R, Tancredi T, Temussi PA, Picone D. The α-to-β Conformational Transition of Alzheimer's Aβ-(1–42) Peptide in Aqueous Media is Reversible: A Step by Step Conformational Analysis Suggests the Location of β Conformation Seeding. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:257–267. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sciarretta KL, Gordon DJ, Petkova AT, Tycko R, Meredith SC. Aβ40-Lactam (D23/K28) Models a Conformation Highly Favorable for Nucleation of Amyloid. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6003–6014. doi: 10.1021/bi0474867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoyer W, Grönwall C, Jonsson A, Ståhl S, Härd T. Stabilization of a β-hairpin in monomeric Alzheimer's amyloid-β peptide inhibits amyloid formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:5099–5104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711731105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nilsberth C, Westlind-Danielsson A, Eckman CB, Condron MM, Axelman K, Forsell C, Stenh C, Luthman J, Teplow DB, Younkin SG, Näslund J, Lannfelt L. The 'Arctic' APP mutation (E693G) causes Alzheimer's disease by enhanced Ab protofibril formation. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:887–893. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cloe AL, Orgel JPRO, Sachleben J, Tycko R, Meredith SC. The Japanese Mutant Aβ (ΔE22-Aβ1–39) Forms Fibrils Instantaneously, with Low-Thioflavin T Fluorescence: Seeding of Wild-Type Aβ1–40 into Atypical Fibrils by ΔE22-Aβ1–39. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2026–2039. doi: 10.1021/bi1016217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stanger HE, Gellman SH. Rules for Antiparallel β-Sheet Design: D-Pro-Gly Is Superior to L-Asn-Gly for β-Hairpin Nucleation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4236–4237. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang ES-H, Liao T-Y, Lim T-S, Fann W, Chen RP-Y. A New Amyloid-Like β-Aggregate with Amyloid Characteristics, Except Fibril Morphology. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385:1257–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haque TS, Little JC, Gellman SH. "Mirror Image" Reverse Turns Promote β-Hairpin Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:4105–4106. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haque TS, Gellman SH. Insights on β-Hairpin Stability in Aqueous Solution from Peptides with Enforced Type I' and Type II' β-Turns. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:2303–2304. [Google Scholar]

- 47.LeVine H. Quantification of β-Sheet Amyloid Fibril Structures with Thioflavin T. Methods in Enzymol. 1999;309:274–284. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Nuallain B, Thakur AK, Williams AD, Bhattacharyya AM, Chen S, Thiagarajan G, Wetzel R. Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Amyloid Assembly Using a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Based Sedimentation Assay. Methods in Enzymol. 2006;413:34–74. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferrone F. Analysis of Protein Aggregation Kinetics. Methods in Enzymol. 1999;309:256–274. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knowles TPJ, Waudby CA, Devlin GL, Cohen SIA, Aguzzi A, Vendruscolo M, Terentjev EM, Welland ME, Dobson CM. An Analytical Solution to the Kinetics of Breakable Filament Assembly. Science. 2009;326:1533–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.1178250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Nuallain B, Shivaprasad S, Kheterpal I, Wetzel R. Thermodynamics of Aβ(1–40) Amyloid Fibril Formation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12709–12718. doi: 10.1021/bi050927h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams AD, Portelius E, Kheterpal I, Guo J-t, Cook KD, Xu Y, Wetzel R. Mapping Aβ Amyloid Fibril Secondary Structure Using Scanning Proline Mutagenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:833–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams AD, Shivaprasad S, Wetzel R. Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis of Aβ(1–40) Amyloid Fibril Stability. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;357:1283–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sciaretta KL, Gordon DJ, Petkova AT, Tycko R, Meredith SC. Aβ40-Lactam (D23/K28) Models a Conformation Highly Favorable for Nucleation of Amyloid. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6003–6014. doi: 10.1021/bi0474867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malinchik SB, Inouye H, Szumowski KE, Kirschner DA. Structural Analysis of Alzheimer's β(1–40) Amyloid: Protofilament Assembly of Tubular Fibrils. Biophys. J. 1998;74:537–545. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77812-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mehta AK, Lu K, Childers WS, Liang Y, Dublin SN, Dong J, Snyder JP, Pingali SV, Thiyagarajan P, Lynn DG. Facial Symmetry in Protein Self-Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9829–9835. doi: 10.1021/ja801511n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szabó Z, Klement É, Jost K, Zarándi M, Soós K, Penke B. An FT-IR Study of the β-Amyloid Conformation: Standardization of Aggregation Grade. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1999;265:297–300. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chu H-L, Lin C-Y. Temperature-induced conformational changes in amyloid β(1–40) peptide investigated by simultaneous FT-IR microspectroscopy with thermal system. Biophys. Chem. 2001;89:173–180. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(00)00228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Greenfield N, Fasman GD. Computed Circular Dichroism Spectra for the Evaluation of Protein Conformation. Biochemistry. 1969;8:4108–4116. doi: 10.1021/bi00838a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB, Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stine WB, Dahlgren KN, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. In vitro characterization of conditions for amyloid-β-peptide oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11612–11622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walsh DM, Townsend M, Podlisny MB, Shankar GM, Fadeeva JV, Agnaf OE, Harley DM, Selkoe DJ. Certain Inhibitors of Synthetic Amyloid β-Peptide (Aβ) Fibrillogenesis Block Oligomerization of Natural Aβ and Thereby Rescue Long-Term Potentiation. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:2455–2462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4391-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, Ashe KH. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-β protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim JR, Murphy RM. Mechanism of Accelerated Assembly of β-Amyloid Filaments into Fibrils by KLVFFK6. Biophys. J. 2004;86:3194–3203. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liang Y, Lynn DG, Berland KM. Direct Observation of Nucleation and Growth in Amyloid Self-Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6306–6308. doi: 10.1021/ja910964c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sandberg A, Luheshi LM, Söllvander S, Barros TPd, Macao B, Knowles TPJ, Biverstål H, Lendel C, Ekholm-Petterson F, Dubnovitsky A, Lannfelt L, Dobson CM, Härd T. Stabilization of neurotoxic Alzheimer amyloid-β oligomers by protein engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:15595–15600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001740107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Necula M, Kayed R, Milton S, Glabe CG. Small molecule inhibitors of aggregation indicate that amyloid β oligomerization and fibrillization pathways are independent and distinct. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:10311–10324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Choi S, Reixach N, Connelly S, Johnson SM, Wilson IA, Kelly JW. A substructure combination strategy to create potent and selective transthyretin kinetic stabilizers that prevent amyloidogenesis and cytotoxicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1359–1370. doi: 10.1021/ja908562q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ball KA, Phillips AH, Nerenberg PS, Fawzi NL, Wemmer DE, Head-Gordon T. Biochemistry. ASAP; 2011. Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Tertiary Structure Ensembles of Amyloid-β Peptides. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1021/bi200732x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nielsen L, Khurana R, Coats A, Frokjaer S, Brange J, Vyas S, Uversky VN, Fink AL. Effect of Environmental Factors on the Kinetics of Insulin Fibril Formation: Elucidation of the Molecular Mechanism. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6036–6046. doi: 10.1021/bi002555c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.