Abstract

Background:

Potential harms associated with hookah smoking are largely unrecognized and it is emerging as a trendy behavior. To help inform policy and preventive interventions, we used responses from a population survey of US adults to examine risk factors associated with hookah involvement.

Method:

An online survey of 17 522 US adults was conducted in 2013. The nationally representative sample was drawn from GfK Group’s KnowledgePanel plus off-panel recruitment. Multinomial logistic regression was used to examine the relationships between tobacco use patterns across multiple products (cigarettes, cigars, and dissolvables), perceived harms towards regular pipe/hookah use, and demographic characteristics with hookah involvement (never used, ever used with/without reusing intent).

Result:

Nearly one in five (16%) of the respondents had smoked hookah at least once in their life (“ever users”). Ever users of hookah were at higher risk of having used cigarettes, cigars, and dissolvable tobacco products (all P < .01). Odds for hookah use were greater for those who perceived regular pipe/hookah use as less dangerous (P < .05). Odds for hookah involvement were higher among young adults (P < .001), individuals with higher educational attainment (P < .01), and Hispanics/Latinos (P < .05).

Conclusions:

Information about the public health harms associated with hookah smoking should be delivered to individuals at-risk for hookah smoking. It is likely that misconceptions about the safety of hookah smoking could be driving, at least in-part, its increase in popularity.

Introduction

Despite the significant progress made towards decreasing the use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products in the United States,1,2 the prevalence of hookah smoking has been increasing.3,4 According to the latest Centers for Disease Control National Adult Tobacco Survey (2009–2010), nearly 6% of US adults had tried hookah smoking at least once in their lifetime and hookah smoking was most prevalent among 18–24 year olds (29%).5,6 In more recent years, hookah cafes and bars have emerged as a growing industry, especially in cities and near or around college campuses.7 As an example, in California alone, there are currently over 2000 shops that sell hookah tobacco and 175 hookah lounges and cafes.8 These findings would seem to suggest that hookah smoking is emerging as a trendy behavior, especially among young adults. Correspondingly, the prevalence of young adults who have tried hookah smoking at least once in their lifetime ranges from 15% to 48%9–12; however, the most recent estimates of hookah smoking are largely based on convenience samples such as college university populations and/or adults recruited from hookah cafes/bars.9,11,13,14 Large-scale studies that examine the current prevalence and correlates of hookah use are critically needed.

The positive social norms surrounding hookah use undoubtedly play a role in its rising popularity. Hookah smoking is often viewed as a healthy alternative to regular cigarettes11,15–18 even though it can involve enough exposure to the addictive drug nicotine to cause addiction.19,20 Still, hookah smoking is often an intermittent behavior and this may be why individuals tend to have confidence in their ability to discontinue hookah smoking without anticipating any challenges to quitting.21–23 Hookah smoking is also distinctive from other tobacco products, in that it is commonly practiced in groups of people and thereby promotes social interaction.24 Within a group, users can either share one hose that is passed between multiple individuals, or in some cases there are several hoses attached to a single device.23 This group activity is commonly practiced at hookah bars or cafes, which are particularly appealing to young adults.25

Hookah sessions typically last half an hour or more, during which it has been estimated that total puff volume could approach that of a cigarette smoker consuming 100 or more cigarettes.26,27 Moreover, hookah smokers can inhale nicotine, carbon monoxide, and excess amounts of smoke, including toxicants and carcinogens.28,29 Emerging research suggests numerous health consequences that are associated with hookah use. Specifically, hookah smoking can damage lung function30 and increase risk for lung cancer, respiratory illness, oral disease, and low birth weight outcomes and such health harms are not well known by the general public.13

The increase in use and the potential harms associated with hookah smoking that are largely unrecognized suggest a potential public health threat. Yet, currently no federal tobacco control policies address hookah smoking. To help inform policy and preventive interventions, we examine prevalence of hookah involvement (ie, ever use and intent to use again) and associations with cigarette smoking and use of other alternative tobacco products (ie, cigars and dissolvable products) among a nationally representative sample of US adults. We additionally examine how perceived health harms towards pipe or hookah use vary across hookah involvement. Last, we examine key sociodemographic variables associated with hookah involvement among adults. A better understanding of the risk factors associated with hookah use and intent to use hookah again can help to develop explanatory models of hookah smoking and identify targets for prevention strategies.

Methods

Sample

The study population consists of US adults (age ≥18 years) who participated in a March 2013 online survey (n = 17 552) as part of the Tobacco Control in a Rapidly Changing Media Environment study, which assessed individuals’ tobacco-related attitudes, beliefs, and behavior, and media consumption patterns. The majority of respondents (75%) were panel members from KnowledgePanel, created by Knowledge Networks, a GfK company.31 KnowledgePanel is an online access panel and panel members are randomly recruited through probability-based sampling with a published sample frame of residential addresses that covers approximately 97% of US households. Tobacco users were oversampled to ensure sufficient sample size for that group. In order to recruit sufficient numbers of tobacco users from small population areas, the KnowedgePanel sample was supplemented with respondents recruited by online advertisements with geographic stratification optimizing demographic diversity. All participants were required to provide their consent online before taking the survey. Of the KnowledgePanel members, 61% completed the screening and most of the eligible respondents (97%) completed the survey; because the off-panel sample frame is unknown, we cannot calculate response rates for off-panel respondents. All participants received an incentive for taking part in our survey. GfK developed analysis survey weights to offset known deviations from equal probability sampling and adjust nonresponse, oversampling of tobacco users, and other sources of non-sampling error. The study received institutional review board approval from University of Illinois at Chicago.

Measures

The survey described hookah to respondents as follows: “A hookah pipe is sometimes called a water pipe or “narghile” pipe. From now on, we will use “hookah” to refer to a water pipe or narghile pipe. There are many types of hookahs. People often smoke hookahs in groups at cafes or in hookah bars.” Generic images of hookah were also provided to the respondents. Next, one item assessed awareness of hookah: “Have you ever heard of a hookah?” (yes/no). Respondents who had heard of a hookah received a question about their use: “Have you ever used a hookah, even one time?” (yes/no). Participants who responded “yes” were defined as an ever user of hookah. A follow-up item about intent to use hookah again was also asked: “Do you plan to use a hookah again in the future?” Responses were as follows: “definitely not,” “probably not,” “not sure,” “probably yes,” and “definitely yes.” Three-levels of hookah use and intent to use were created to determine hookah involvement: never used hookah, used hookah without reusing intent (ie, participants responded “definitely not,” “probably not,” or “not sure” for plan to use hookah in the future), and used hookah with reusing intent (ie, participants responded “probably yes” or “definitely yes” for plan to use hookah in the future). Respondents were also asked about their perceived harms of hookah use: “How dangerous do you think smoking tobacco in a regular pipe or hookah is to a person’s own health?” Responses were collapsed into two groups: “not, little, or moderately dangerous” versus “very or extremely dangerous.”

The survey assessed demographics and tobacco use status. To determine if participants were never users or current users of cigarettes, they were asked if they “now smoke cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all” an item from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and the National Health Interview Survey32,33. Participants were also asked if they had ever smoked cigarettes at least 100 times in their life and if so, they were labeled as former users. Cigar smoking status was similarly obtained and participants were also asked if they had ever used dissolvable tobacco products.

Data Analysis

Multinomial logistic regression was used to examine the relationships between tobacco use patterns across multiple products (cigarettes, cigars, and dissolvable), perceived harms towards regular pipe/hookah use, and demographic characteristics with hookah involvement (never used, used but no reusing intent, used with reusing intent). Having never used hookah was the reference group. Bivariate relationships were first examined. Multinomial logistic regression models were used to examine the relationship between hookah involvement and other tobacco use patterns, perceived harms toward regular pipe/hookah use, and demographic characteristics known to be associated with tobacco use, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, employment status, and region of the country. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are reported.

All analyses were performed using survey procedures in SAS version 9.3 for Windows, incorporating survey weights as appropriate. Approximately 2% of the respondents had missing data for one or more of the variables of interest and were excluded from analysis, resulting in an unweighted total sample of 17 164. Unweighted sample sizes but weighted percentages are presented throughout the results.

Results

Most of the participants (n = 13 877; 84.3%) had never used hookah, while 11.4% (n = 2295) reported ever use of hookah, with no intention to use again, and 4.3% (n = 992) reported ever use of hookah, with intentions of reusing. Of the ever users of hookah, 27.3% had reusing intent. Most (71.0%) of the participants perceived smoking tobacco in a regular pipe/hookah to be very or extremely dangerous while 29.0% perceived that it was not/a little/moderately dangerous. More than half of respondents (51.5%) were never-smokers, 27.7% were former smokers, and 20.8% smoked every day or some days. Most of the participants had never smoked cigars (61.1%) while 29.6% were former cigar smokers and 9.4% were current cigar smokers. Only 1.6% of the participants had ever used dissolvable tobacco products. Approximately 52.1% of the sample was female and 68.3% were White.

Table 1 shows the distribution of tobacco use, harm beliefs, and demographic characteristics by the different levels of hookah use (never used, used without reusing intent, and used with reusing intent). The last two columns of the table also show the results of bivariate associations. Those who used hookah without and with intent to use again are each compared with the reference group of never having used hookah.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants by Levels of Hookah Use, Unadjusted Odds Ratios (n = 17 164)

| Ever hookah user (n = 3287) | Bivariable results from multinomial logistic regression models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never used hookah (n = 13 877) | No intent to use again (n = 2295) | Intent to use again (n = 992) | No intent to use again vs. never used | Intent to use again vs. never used | |

| n (weighted %) | n (weighted %) | n (weighted %) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Other tobacco use | |||||

| Cigarette smoking status | |||||

| Never | 5922 (55.1) | 526 (32.6) | 155 (32.4) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Former | 3402 (27.4) | 609 (34.9) | 82 (13.4) | 2.2 (1.8, 2.6) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) |

| Some days | 654 (2.6) | 199 (7.2) | 170 (13.9) | 4.7 (3.5, 6.3) | 9.0 (6.3, 13.1) |

| Every day | 3899 (14.9) | 961 (25.3) | 585 (40.2) | 2.9 (2.4, 3.4) | 4.6 (3.5, 6.0) |

| Cigar smoking status | |||||

| Never | 8503 (67.0) | 665 (31.7) | 163 (21.8) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Former | 3889 (26.2) | 1092 (51.8) | 298 (37.2) | 4.2 (3.5, 5.0) | 4.4 (3.1, 6.1) |

| Current | 1485 (6.8) | 538 (16.6) | 531 (41.0) | 5.2 (4.2, 6.4) | 18.6 (13.6, 25.4) |

| Ever used dissolvable products | |||||

| No | 13 647 (99.0) | 2184 (96.7) | 834 (90.0) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 230 (1.0) | 111 (3.3) | 158 (10.0) | 3.5 (2.4, 5.0) | 11.4 (8.1, 15.9) |

| Attitudes/beliefs | |||||

| How dangerous do you think smoking tobacco in a regular pipe or hookah is to a person’s own health? | |||||

| Pipe/hookah is not/little/ moderately dangerous | 4021 (26.3) | 938 (37.9) | 561 (58.9) | 1.7 (1.5, 2.0) | 4.0 (3.2, 5.0) |

| Pipe/hookah is very/extremely dangerous | 9856 (73.7) | 1357 (62.1) | 431 (41.1) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age | |||||

| 18–24 y | 668 (7.8) | 223 (12.4) | 326 (35.7) | 2.0 (1.5, 2.7) | 7.3 (5.1–10.3) |

| 25–34 y | 1622 (17.2) | 529 (31.0) | 371 (40.1) | 2.2 (1.8, 2.8) | 3.7 (2.6, 5.2) |

| 35–44 y | 1887 (15.1) | 303 (12.1) | 123 (9.5) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 45–54 y | 2723 (23.4) | 415 (20.3) | 95 (11.0) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.2) |

| 55–64 y | 3358 (16.7) | 592 (16.9) | 57 (3.0) | 1.3 (0.995, 1.6) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.5) |

| ≥65 y | 3619 (19.9) | 233 (7.2) | 20 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.6) | 0.05 (0.03, 0.09) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 11 168 (69.0) | 1833 (67.1) | 664 (56.9) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Black | 1098 (12.3) | 107 (7.1) | 83 (9.9) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 884 (12.5) | 188 (16.4) | 138 (23.8) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.7) | 2.3 (1.7, 3.2) |

| Other/multiple races | 727 (6.3) | 167 (9.5) | 107 (9.5) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.1) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 6070 (46.3) | 1127 (56.5) | 449 (56.5) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.9) |

| Female | 7807 (53.7) | 1168 (43.5) | 543 (43.5) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Education | |||||

| High school or less | 3793 (45.0) | 461 (30.4) | 243 (36.7) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Some college | 4845 (30.3) | 927 (35.1) | 447 (36.4) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.1) | 1.5 (1.1, 1.9) |

| Bachelor’s or more | 5239 (24.7) | 907 (34.4) | 302 (26.9) | 2.1 (1.7, 2.5) | 1.3 (1.003, 1.8) |

| Income | |||||

| <$25 000 | 2760 (18.4) | 555 (18.5) | 312 (25.7) | Ref. | Ref. |

| $25 000–49 999 | 3780 (24.0) | 602 (20.7) | 270 (24.3) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.98) |

| $50 000–74 999 | 2883 (19.7) | 470 (19.8) | 186 (16.1) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) |

| $75 000–99 999 | 1980 (18.0) | 316 (23.3) | 95 (16.2) | 1.3 (1.02, 1.6) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) |

| ≥$100 000 | 2474 (19.9) | 352 (17.8) | 129 (17.6) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 0.6 (0.4, 0.9) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 7780 (56.6) | 961 (45.4) | 269 (26.4) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Divorced/separated | 2123 (12.0) | 413 (14.5) | 88 (6.5) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.8) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) |

| Never married | 2181 (19.5) | 532 (26.8) | 414 (45.8) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.1) | 5.0 (3.8, 6.6) |

| Living with partner | 954 (7.0) | 313 (11.4) | 207 (20.4) | 2.0 (1.6, 2.6) | 6.3 (4.5, 8.7) |

| Widowed | 839 (4.8) | 76 (2.0) | 14 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.9) |

| Employment | |||||

| Employed | 7095 (55.3) | 1403 (64.4) | 648 (67.1) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Laid off/looking for work | 1114 (9.3) | 245 (11.9) | 165 (16.8) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) |

| Retired/disabled | 4703 (27.0) | 472 (15.3) | 88 (8.4) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.6) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.4) |

| Not working—other reason | 965 (8.5) | 175 (8.5) | 91 (7.7) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.1) |

| Region of the country | |||||

| Midwest | 3654 (22.8) | 541 (19.9) | 212 (19.9) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Northeast | 2363 (17.7) | 421 (20.5) | 185 (22.4) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.03, 2.0) |

| South | 4860 (37.7) | 723 (34.7) | 316 (33.9) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) |

| West | 3000 (21.8) | 610 (24.9) | 279 (23.8) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.7) |

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

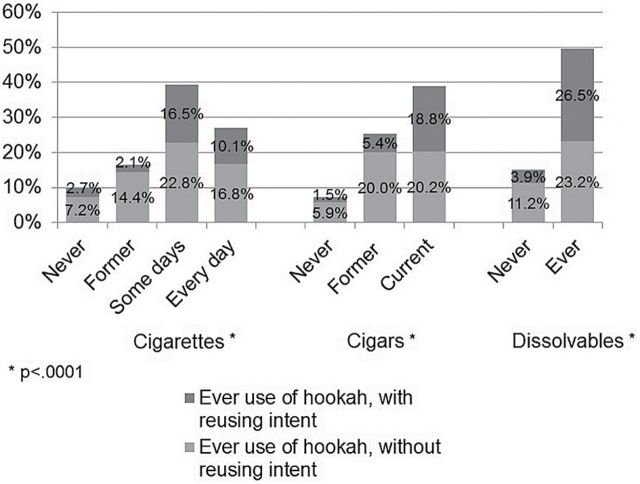

Hookah Involvement and Use of Other Tobacco Products

Figure 1 shows the distribution of ever use (used hookah with/without reusing intent) by other types of tobacco use. Among cigarette users, those who smoked cigarettes some days had the greatest prevalence of ever hookah use (39%), and 42% of these ever users had reusing intent. Current cigar users also had a high prevalence of ever use of hookah (39%), and 48% of the ever users had reusing intent. Finally, 50% of participants who had ever tried dissolvable tobacco products were ever users of hookah, and 53% of the ever users had reusing intent.

Figure 1.

The distribution of hookah use without reusing intent and with reusing intent differed significantly by cigarette use (Rao-Scott chi-square = 443.5, df = 6, P < .0001), cigar use (Rao-Scott chi-square = 855.4, df = 4, P < .0001), and use of dissolvable products (Rao-Scott chi-square = 285.9, df = 2, P < .0001).

In the multivariate logistic regression model (Table 2), compared to non-hookah users (lowest risk group), cigarette smokers had about three times the odds of being ever users of hookah with and without reusing intent, irrespective of the type of cigarette smoker (ie, smokes some days or smokes every day). Similarly, both former and current cigar smokers had over three times the odds of being ever users of hookah without reusing intent versus non-cigar smokers. In addition, both former and current cigar had even higher odds of reusing intent, particularly for current cigar smokers where the odds was eight times versus non-cigar smokers. For participants who had used dissolvable products, the odds of having used hookah with the intent of reusing it was two times the odds for those who had never used hookah.

Table 2.

Results of Multivariable Multinomial Logistic Regression Model Predicting Hookah Use (Weighted n = 17 164)

| Ever hookah user | ||

|---|---|---|

| No intent to use again vs. never used | Intent to use again vs. never used | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Other tobacco use | ||

| Cigarette smoking status | ||

| Never | Ref. | Ref. |

| Former | 2.5 (2.0, 3.0) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.3) |

| Some days | 3.2 (2.3, 4.4) | 3.7 (2.3, 5.9) |

| Every day | 2.7 (2.2, 3.3) | 3.3 (2.2, 4.9) |

| Cigar smoking status | ||

| Never | Ref. | Ref. |

| Former | 3.4 (2.8, 4.0) | 4.2 (2.9, 6.2) |

| Current | 3.0 (2.4, 3.9) | 8.0 (5.3, 12.0) |

| Ever used dissolvable products | ||

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.3 (0.9, 2.0) | 2.0 (1.3, 3.1) |

| Attitudes/beliefs | ||

| How dangerous do you think smoking tobacco in a regular pipe or hookah is to a person’s own health? | ||

| Pipe/Hookah is not/little/moderately dangerous | 1.2 (1.03, 1.4) | 2.3 (1.8, 3.0) |

| Pipe/Hookah is very/extremely dangerous | Ref. | Ref. |

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| 18–24 y | 3.0 (2.1, 4.3) | 8.6 (5.6, 13.1) |

| 25–34 y | 2.2 (1.7, 2.9) | 3.5 (2.4, 5.1) |

| 35–44 y | Ref. | Ref. |

| 45–54 y | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.5) |

| 55–64 y | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.6) |

| ≥65 y | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) | 0.1 (0.04, 0.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | Ref. | Ref. |

| Black | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.3 (1.01, 1.7) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.6) |

| Other/multiple races | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.1) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.0 (0.8, 1.1) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) |

| Female | Ref. | Ref. |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | Ref. | Ref. |

| Some college | 1.6 (1.3, 2.0) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.1) |

| Bachelor’s or more | 2.6 (2.1, 3.3) | 2.4 (1.6, 3.7) |

| Income | ||

| <$25 000 | Ref. | Ref. |

| $25 000–49 999 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) |

| $50 000–74 999 | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) |

| $75 000–99 999 | 1.4 (1.1, 1.9) | 1.2 (0.7, 1.9) |

| ≥$100 000 | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.0) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | Ref. | Ref. |

| Divorced/separated | 1.6 (1.3, 2.1) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.1) |

| Never married | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.8) |

| Living with partner | 1.5 (1.1, 1.9) | 2.6 (1.7, 4.0) |

| Widowed | 1.0 (0.7, 1.6) | 1.5 (0.6, 3.5) |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | Ref. | Ref. |

| Laid off/looking for work | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) |

| Retired/disabled | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.3) |

| Not working—other reason | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) |

| Region of the country | ||

| Midwest | Ref. | Ref. |

| Northeast | 1.5 (1.2, 1.9) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.8) |

| South | 1.2 (0.996, 1.5) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) |

| West | 1.3 (1.1, 1.7) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) |

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Hookah Involvement and Perceived Health Harms Towards Hookah Use

Approximately 24% of participants who felt that regular pipe/hookah use is not, a little or moderately dangerous were ever hookah users (37% of these had intent to use again), while 12% of those who thought it was very or extremely dangerous were ever hookah users (20% of these had intent to use again). In the multivariable model (Table 2), participants who perceived that regular pipe/hookah use is not, little, or moderately dangerous versus very or extremely dangerous were significantly more likely to have used hookah without reusing intent. These participants who perceived less harm from smoking tobacco in a regular pipe/hookah had even higher odds of having used hookah with reusing intent.

Hookah Involvement and Associations with Sociodemographic Variables

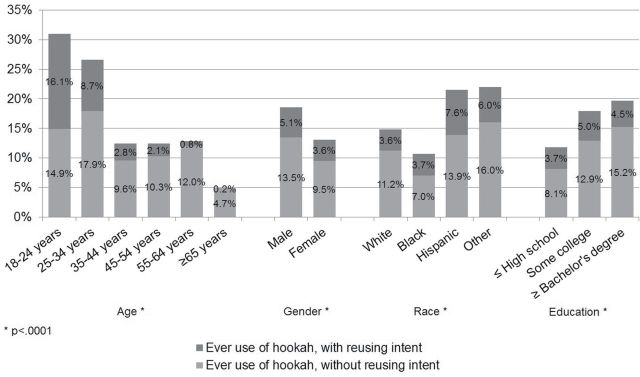

Figure 2 shows the bivariate distribution of hookah use (ever use with/without reusing intent) by some demographic characteristics. Nearly one-third of the 18–24 year old participants in our sample had used hookah at least once in their lifetime (31%), and over half (52%) of these young adult ever hookah users reported reusing intent (Figure 2). Males (19%) were more likely than females (13%) to be ever hookah users. In addition, Hispanic/Latino respondents (22%) were more likely than Whites (15%) or Blacks (11%) to have used hookah at least once in their lifetime. About one-third of the Hispanic/Latino ever hookah users reported reusing intent. Participants with at least some college education (18% for some college, 20% for bachelor’s degree or more) had a greater prevalence of ever hookah use than those with a high school degree or less (12%).

Figure 2.

The distribution of hookah use without intent to use again and with intent to use again differed significantly by age (Rao-Scott chi-square = 717.7, df = 10, P < .0001), gender (Rao-Scott chi-square = 41.9, df = 2, P < .0001), race (Rao-Scott chi-square 66.1, df = 6, P < .0001), and education level (Rao-Scott chi-square = 77.1, df = 4, P < .0001).

In the multivariate model (Table 2), 18–24 year olds had the greatest odds of using hookah; this age group had three times the odds of using hookah without reusing intent and over eight times the odds of using hookah with reusing intent compared to 35–44 year olds. Ever hookah users without reusing intent were more likely to be Hispanic/Latino and less likely to be Black (reference group was Whites) in comparison to non-hookah users. Similarly, ever users of hookah with reusing intent were more likely to be Hispanic/Latino in comparison to non-hookah users. Compared to participants with only a high school diploma or less, the odds of hookah ever-use—with or without intentions to reuse—were twice as high for participants who had completed college.

In addition, controlling for other correlates, those who were not married (divorced, never married, or living with a partner) were more likely to be ever hookah users without reusing intent versus those who were married. Similarly, those who were never married or living with a partner were more likely to be ever hookah users with reusing intent. Finally, compared to people living in the Midwest, those in the Northeast were more likely to use hookah, irrespective of their intent to reuse. Those living in the West were more likely to have used hookah without reusing intent.

Discussion

In a nationally representative sample of US adults, we examined the prevalence of hookah involvement and identified associated key risk factors. We found that approximately one in six (16%) respondents in our sample had smoked hookah at least once in their life. Nearly one-third of individuals who had tried hookah smoking intended to smoke hookah again.

Furthermore, we found that ever hookah users were significantly more likely to be former or current users of other tobacco products versus nonusers of other tobacco products. Our findings were consistent, irrespective of the individuals’ intent to use hookah again and across multiple tobacco products including cigarettes and cigars; ever hookah users with reusing intent were significantly more likely to have used dissolvable products than non-hookah users. Our findings stress the concurrent use of multiple tobacco products that appears to be relatively common among hookah users, and complements existing national studies of adolescents and college students that have likewise found risk for hookah use to be higher among cigarette smokers and individuals who use non-hookah alternative tobacco products (eg, dissolvables and cigars).34–36 Unlike existing studies, a unique contribution of our study is measuring intentions to use hookah again, which may be helpful for understanding increased risk for hookah smoking among individuals who have already tried hookah smoking on at least one occasion. There is still much to learn about the harmful health effects and degree of toxin exposure associated with hookah use; nevertheless, our findings signal a concerning trend that hookah users are potentially exposing themselves to toxicants and carcinogens via hookah smoking as well as through the use of other tobacco products.

It is also worrisome that ever hookah users reported lower perceived harm to health with regular pipe/hookah use versus non-hookah users. In fact, hookah users with reusing intent had over twice the odds of non-hookah users to perceive regular pipe/hookah as less dangerous. There is evidence that typical hookah smoking (often occurring within a hookah bar) is associated with significant nicotine intake and carcinogen exposure.37–39 Our findings are based on a unique online and nationally representative sample of adults and help to corroborate the existing studies that suggest that misperceptions about the consequences of hookah smoking may facilitate its use.40–42 Health professionals are encouraged to work towards increasing awareness of the associated harms and addictive potential that is linked to hookah use in an effort to counter such misperceptions and curb this new potential health threat.

We identified key sociodemographic factors correlated with hookah involvement, including young adulthood age, higher educational status, and Hispanic/Latino race. Our findings corroborate past studies that indicate hookah smoking is increasingly popular among young adults, especially those who have or are working towards obtaining a college degree.36,40,43,44 There are currently many hookah establishments that have emerged and these locations tend to be in “trendy” locations such as cafes and lounges in metropolitan areas that are often located near college campuses. Our findings might be related to the strategic locations of hookah establishments near and/or around college campuses, or perhaps they are due to the social networking and marketing of hookah use that is clustered among college students. Moreover, young people tend to frequent bars and clubs more often than older adults45 which can additionally facilitate risk for hookah smoking. It is concerning that hookah smoking is most popular among a younger demographic because young adults are at a vulnerable age of development when tobacco use behaviors often transition to addiction.46,47

Our findings also signaled an increase for hookah use among Hispanics/Latinos, which is consistent with existing studies.48–50 Compared to Whites and Blacks, Hispanics/Latinos tend to report lower rates of tobacco use in national surveys51; thus, our findings warrant cause for concern and action with regards to targeting risk behaviors that may increase health disparities.

The findings of this study were limited by several factors. Our study is cross-sectional, preventing the determination of temporal relationships. However, the survey did provide information on potential correlates, such as age, socioeconomic status, and employment and educational status; thus, we could control for these important demographic variables in our multivariate models. We also rely on participants’ self-report for all of the data, and thus risk some unknown level of reporting error. Non-tobacco substances, including alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs were not queried and were therefore omitted from our analyses. In addition, given the exploratory nature of our study, participants were not asked their reason(s) for not wanting to re-use hookah, nor did we ask participants follow-up questions to find out if hookah was one’s primary tobacco product and/or how often and where participants smoked hookah. Participants under 18 years old did not take part in our study; thus, our findings are not generalizable to youth. Although we recruited a supplementary convenience sample, they were blended with the probability-based sample to resemble the US adult population with respect to demographics, and potential bias due to convenience sampling has been adjusted by weighting. Additionally, we queried participants about their perceptions of harms associated with smoking tobacco in a “regular pipe or hookah” and it is possible that participants could have different perceptions of harm for tobacco smoking via a regular pipe versus hookah. Thus, it is difficult to distinguish perceptions of harm by regular pipe versus hookah.

Nevertheless, our findings demonstrated a clear pattern of increased odds for hookah involvement among young adults with higher educational attainment (versus a high school education or less), and Hispanics/Latinos. In addition, cigarette, cigar, and dissolvable users and individuals who perceived low risk perceptions of harm associated with pipe or hookah use were also more likely to smoke hookah and have intent to smoke hookah in the future. Our findings suggest that college campuses might be an ideal location for health professionals to target their prevention efforts; current tobacco users and individuals of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity are also worthy of targeted intervention. Scott-Sheldon et al. and Webb et al. recently published reviews of efficacious interventions that could potentially be used to target these at-risk groups.52,53 Accordingly, educational information about the public health harms associated with hookah smoking should be delivered to individuals at-risk for hookah smoking given the likelihood that misconceptions about the safety of hookah smoking could be driving, at least in-part, one’s intent to smoke hookah again. In summary, our study enables prevention efforts to more accurately delivery targeted messages to individuals who are at increased risk for hookah use and may benefit from preventive intervention.

Funding

This study and the preparation of this report was funded by National Institute of Health grants R01-DA032843 (PACR) and U0-CA154254 (SE).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in current cigarette smoking among high school students and adults, United States, 1965–2011 www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/tables/trends/cig_smoking/ Accessed September 1, 2014.

- 2. Nelson DE, Mowery P, Tomar S, Marcus S, Giovino G, Zhao L. Trends in smokeless tobacco use among adults and adolescents in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):897–905. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.061580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnston L, O’Malley P, Bachman J, Schulenberg J. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings, 2011 Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2012. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED529133.pdf Accessed October 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Interventions for waterpipe smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005549. 10.1002/14651858.CD005549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Codebook for 2009–2010 National Adult Tobacco Survey http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nats/pdfs/codebook.pdf Accessed June 20, 2014.

- 6. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009–2010 National Adult Tobacco Survey, Demographic Crosstabs. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nats/pdfs/demog-crosstabs.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cobb C, Ward KD, Maziak W, Shihadeh AL, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: an emerging health crisis in the United States. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34(3):275. 10.5993/AJHB.34.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rezk-Hanna M, Macabasco-OʼConnell A, Woo M. Hookah smoking among young adults in southern California. Nurs Res. 2014;63(4):300–306. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eissenberg T, Ward KD, Smith-Simone S, Maziak W. Waterpipe tobacco smoking on a U.S. College campus: prevalence and correlates. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(5):526–529. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith SY, Curbow B, Stillman FA. Harm perception of nicotine products in college freshmen. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(9):977–982. http://ntr.oxfordjournals.org/content/9/9/977.long Accessed January 20, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Primack BA, Sidani J, Agarwal AA, Shadel WG, Donny EC, Eissenberg TE. Prevalence of and associations with waterpipe tobacco smoking among U.S. university students. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(1):81–86. 10.1007/s12160-008-9047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith-Simone SY, Curbow BA, Stillman FA. Differing psychosocial risk profiles of college freshmen waterpipe, cigar, and cigarette smokers. Addict Behav. 2008;33(12):1619–1624. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Akl EA, Gunukula SK, Aleem S, et al. The prevalence of waterpipe tobacco smoking among the general and specific populations: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):244–255. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grekin ER, Ayna D. Argileh use among college students in the United States: an emerging trend. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(3):472–475. www.jsad.com/jsad/article/Argileh_Use_Among_College_Students_in_the_United_States_An_Emerging_Trend/2251.html Accessed October 2, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jackson D, Aveyard P. Waterpipe smoking in students: prevalence, risk factors, symptoms of addiction, and smoke intake. Evidence from one British university. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:174. 10.1186/1471-2458-8-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward K, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(2):393–398. 10.1080/14622200701825023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roskin J, Aveyard P. Canadian and English students’ beliefs about waterpipe smoking: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):10. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holtzman AL, Babinski D, Merlo LJ. Knowledge and attitudes toward hookah usage among university students. J Am Coll Health. 2013;61(6):362–370. 10.1080/07448481.2013.818000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maziak W, Ward K, Afifi Soweid R, Eissenberg T. Tobacco smoking using a waterpipe: a re-emerging strain in a global epidemic. Tob Control. 2004;13(4):327–333. 10.1136/tc.2004.008169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shafagoj Y, Mohammed F, Hadidi K. Hubble-bubble (water pipe) smoking: levels of nicotine and cotinine in plasma, saliva and urine. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;40(6):249–255. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12078938 Accessed January 22, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Akl EA, Jawad M, Lam WY, Co CN, Obeid R, Irani J. Motives, beliefs and attitudes towards waterpipe tobacco smoking: a systematic review. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:12. 10.1186/1477-7517-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nuzzo E, Shensa A, Kim KH, et al. Associations between hookah tobacco smoking knowledge and hookah smoking behavior among US college students. Health Educ Res. 2013;28(1):92–100. 10.1093/her/cys095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maziak W, Eissenberg T, Ward K. Patterns of waterpipe use and dependence: implications for intervention development. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;80(1):173–179. 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gatrad R, Gatrad A, Sheikh A. Hookah smoking. BMJ. 2007;335(7609):20. 10.1136/bmj.39227.409641.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aljarrah K, Ababneh ZQ, Al-Delaimy WK. Perceptions of hookah smoking harmfulness: predictors and characteristics among current hookah users. Tob Induc Dis. 2009;5(1):16. 10.1186/1617-9625-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shihadeh A, Azar S, Antonios C, Haddad A. Towards a topographical model of narghile water-pipe café smoking: a pilot study in a high socioeconomic status neighborhood of Beirut, Lebanon. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79(1):75–82. 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Djordjevic MV, Stellman SD, Zang E. Doses of nicotine and lung carcinogens delivered to cigarette smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(2):106–111. 10.1093/jnci/92.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Daher N, Saleh R, Jaroudi E, et al. Comparison of carcinogen, carbon monoxide, and ultrafine particle emissions from narghile waterpipe and cigarette smoking: Sidestream smoke measurements and assessment of second-hand smoke emission factors. Atmos Environ. 2010;44(1):8–14. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):518–523. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raad D, Gaddam S, Schunemann HJ, et al. Effects of water-pipe smoking on lung function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2011;139(4):764–774. 10.1378/chest.10–0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. GfK Knowledge Networks. Knowledge Panel overview 2014. www.gfk.com/us/Solutions/consumer-panels/Pages/GfK-KnowledgePanel.aspx Accessed March 31, 2014.

- 32. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2015. www.cdc.gov/brfss/ Accessed January 20, 2015.

- 33. Blackwell D, Lucas J, Clarke T. Summary health statistics for us Adults: national health interview survey, 2012. Vital Health Stat. 2014;10(260):1–161. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_260.pdf Accessed January 20, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Palamar JJ, Zhou S, Sherman S, Weitzman M. Hookah use among U.S. high school seniors. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):227–234. 10.1542/peds.2014-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Amrock SM, Gordon T, Zelikoff JT, Weitzman M. Hookah use among adolescents in the United States: results of a national survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(2):231–237. 10.1093/ntr/ntt160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jarrett T, Blosnich J, Tworek C, Horn K. Hookah use among U.S. college students: results from the National College Health Assessment II. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(10):1145–1153. 10.1093/ntr/nts003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barnett TE, Curbow BA, Soule EK, Jr, Tomar SL, Thombs DL. Carbon monoxide levels among patrons of hookah cafes. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(3):324–328. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jacob P, III, Abu Raddaha AH, Dempsey D, et al. Comparison of nicotine and carcinogen exposure with water pipe and cigarette smoking. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(5):765–772. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Helen G, St, Benowitz NL, Dains KM, Havel C, Peng M, Jacob P., III Nicotine and carcinogen exposure after water pipe smoking in hookah bars. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(6):1055–1066. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brockman LN, Pumper MA, Christakis DA, Moreno MA. Hookah’s new popularity among US college students: a pilot study of the characteristics of hookah smokers and their Facebook displays. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6)e001709. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Goodwin RD, Grinberg A, Shapiro J, et al. Hookah use among college students: prevalence, drug use, and mental health. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;141:16–20. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fielder RL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Predictors of initiation of hookah tobacco smoking: a one-year prospective study of first-year college women. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26(4):963. 10.1037/a0028344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Braun RE, Glassman T, Wohlwend J, Whewell A, Reindl DM. Hookah use among college students from a Midwest University. J Community Health. 2012;37(2):294–298. 10.1007/s10900-011-9444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smith JR, Edland SD, Novotny TE, et al. Increasing hookah use in California. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1876. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Biener L, Albers AB. Young adults: vulnerable new targets of tobacco marketing. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):326-330. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1448251/ Accessed January 20, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Backinger CL, Fagan P, Matthews E, Grana R. Adolescent and young adult tobacco prevention and cessation: current status and future directions. Tob Control. 2003;12(Suppl IV):iv46–iv53. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_4.iv46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Giovino GA, Henningfield JE, Tomar SL, Escobedo LG, Slade J. Epidemiology of tobacco use and dependence. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;17(1):48–65. http://epirev.oxfordjournals.org/content/17/1/48.long Accessed January 20, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Manderski B, Michelle T, Hrywna M, Delnevo CD. Hookah use among New Jersey youth: associations and changes over time. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(5):693–699. 10.5993/AJHB.36.5.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barnett TE, Smith T, He Y, et al. Evidence of emerging hookah use among university students: a cross-sectional comparison between hookah and cigarette use. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):302. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Barnett TE, Forrest JR, Porter L, Curbow BA. A multiyear assessment of hookah use prevalence among Florida high school students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(3):373–377. 10.1093/ntr/ntt188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4795. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHnationalfindingresults2012/NSDUHnationalfindingresults2012/NSDUHresults2012.pdf Accessed January 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Webb MS, Rodríguez-Esquivel D, Baker EA. Smoking cessation interventions among Hispanics in the United States: a systematic review and mini meta-analysis. Am J Health Promot. 2010;25(2):109–118. 10.4278/ajhp.090123-LIT-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey KB, Elliott JC, Garey L, Carey MP. Efficacy of alcohol interventions for first-year college students: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(2):177. 10.1037/a0035192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]