Abstract

Tolerance of allografts achieved in mice via stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism relies essentially on continuous elimination of developing alloreactive T cells in the thymus (central deletion). Conversely, while only transient mixed chimerism is observed in nonhuman primates and patients, it is sufficient to ensure tolerance of kidney allografts. In this setting, it is likely that tolerance depends on peripheral regulatory mechanisms rather than thymic deletion. This implies that, in primates, upsetting the balance between inflammatory and regulatory alloimmunity could abolish tolerance and trigger the rejection of previously accepted renal allografts. In this study, six monkeys that were treated with a mixed chimerism protocol and had accepted a kidney allograft for periods of 1–10 years after withdrawal of immunosuppression received subcutaneous injections of IL-2 cytokine (0.6–3 × 106 IU/m2). This resulted in rapid rejection of previously tolerated renal transplants and was associated with an expansion and reactivation of alloreactive pro-inflammatory memory T cells in the host’s lymphoid organs and in the graft. This phenomenon was prevented by anti-CD8 antibody treatment. Finally, this process was reversible in that cessation of IL-2 administration aborted the rejection process and restored normal kidney graft function.

Introduction

Tolerance of allogeneic skin and organ transplants has been regularly achieved in laboratory rodents via nonmyeloablative conditioning, infusion of donor bone marrow along with T cell depletion and/or leukocyte costimulation blockade (1,2). In mice, tolerance relies primarily on sustained donor hematopoietic macrochimerism associated with continuous deletion of developing alloreactive T cell clones in the recipient’s thymus (3–5). Similar protocols have typically failed to achieve such stable mixed chimerism in primates, presumably due to pre-existing donor-reactive memory T cells (6–8). Nevertheless, our previous reports demonstrate that transient mixed chimerism is sufficient to ensure long-term survival of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-mismatched kidney grafts following cessation of immunosuppression in cynomolgus monkeys and patients (9,10). Remarkably, tolerant monkeys displayed donor-specific T cell unresponsiveness and accepted a skin allograft from the same but not a third-party donor, a result demonstrating that they had developed donor-specific immune tolerance (10). Yet, some monkeys ultimately exhibited de novo donor-specific antibodies (DSA) and underwent chronic humoral rejection, a phenomenon associated with the restoration of an anti-donor T cell response (11). These results suggest a lack or incomplete depletion of donor-specific T cells in monkeys tolerized via current mixed chimerism procedures. In this scenario, it is plausible that conditions such as inflammation, infection or Treg depletion, which are known to activate pro-inflammatory T cells (12–19), could restore alloreactivity by T cells and cause graft rejection in monkeys rendered tolerant via mixed chimerism.

Administration of high doses of recombinant IL-2 ranging from 5 × 107 to 109 IU/m2 has been used to enhance T cell–mediated pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic immunity (20–22). In fact, IL-2 administration impaired cyclosporin A-induced tolerance of MHC class I disparate kidney allografts in miniature swine (23). Similarly, IL-2 injections caused the rejection of otherwise spontaneously accepted liver allografts in mice (24). In contrast, in vivo inoculation of low doses of IL-2 (105–5 × 106 IU/m2) is known to expand preferentially anti-inflammatory, i.e. regulatory, CD4+FOXP3+ T cells (Tregs) owing to their expression of the high affinity IL-2 receptor (CD25) (25–28). Likewise, some recent studies show that daily administrations of low-dose IL-2 suppress chronic graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) in bone marrow–transplanted patients, presumably via Treg expansion (29). Together, these studies show that the effects of IL-2 on transplant tolerance differ dramatically depending upon the dose injected and the context of its administration.

The current study investigated the effects of IL-2 on T cell alloreactivity and maintenance of tolerance to kidney allografts induced via mixed chimerism in nonhuman primates. A series of cynomolgus monkeys treated with our mixed chimerism protocol and having accepted renal allografts for 1–10 years in the absence of immunosuppression were injected with low doses of IL-2 cytokine (0.6–3 × 106 IU/m2). This restored alloreactive inflammatory T cell responses and caused acute cellular allograft rejection. Remarkably, however, this phenomenon was reversible in that cessation of IL-2 administration aborted the rejection process and restored normal kidney graft function.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Twelve cynomolgus monkeys that weighed 3–7 kg were used (Charles River Primates, Wilmington, MA). All surgical procedures and postoperative care of animals were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of primates and were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Animal Research.

IL-2 treatments

Animals were treated with daily subcutaneous injections of IL-2 (Aldeleukin, human recombinant, 0.6 × 106 IU/m2–3 × 106 IU/m2 BSA per day, Prometheus, San Diego, CA). Serum IL-2 concentrations were measured by ELISA (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) on the third day of IL-2 treatment.

Conditioning and renal and bone marrow transplantations

Recipients subjected to this study are summarized in Table 1. The elements of our nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen have been reported in detail (10, 66). Briefly, these included TBI (1.5 Gy × 2), local TI (7 Gy), intravenous ATG (ATGAM, Pharmacia and Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI) (50 mg/kg/day) and kidney and bone marrow allotransplantation or splenocyte infusion (from the same donor), followed by a 1-month course of cyclosporine (CyA; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) maintaining therapeutic serum levels (>300 ng/mL). The recipients were also treated with anti-CD154 mAbs (h5C8, 20 mg/kg) plus ketorolac (1 mg/kg on days −1 and 0) to avoid thrombosis (the standard regimen). M5710 received belatacept (CTLA4-Ig, 20 mg/kg on day 0 and 2, 10 mg/kg on day 5 and 15) instead of anti-CD154 mAbs. In the delayed tolerance protocol, recipients were maintained on conventional immunosuppression (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and steroids) for four months followed by conditioning and bone marrow cell infusion (30,31). All recipients underwent unilateral native nephrectomy and ligation of the contralateral ureter on day 0. The remaining native (hydronephrotic) kidney was removed 60–80 days after transplantation.

Table 1.

Monkeys used in this study

| MHC matching |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient | Donor | Treatment | Graft survival at the time of IL-2 injection |

MHC I | MHC II | Haplomatched | Pathology (Pre-IL-2 treatment) |

| 2800 | 3800 | Std | >10 years | 1 | 0 | − | No rejection |

| 2108 | 2808 | Del | 730 days | 2 | 2 | + | No rejection (cell aggregates) |

| 6007 | 6307 | Del | >3 years | 1 | 0 | − | Mild CHR |

| 8907 | 3107 | Del | 1124 days | 1 | 0 | − | No rejection (cell aggregates) |

| 4109 | 4309 | Std | 544 days | 2 | 2 | + | No rejection (cell aggregates) |

| 5710 | 4609 | Std | 370 days | 0 | 0 | − | No rejection (cell aggregates) |

All recipients were conditioned and infused with bone marrow cells either at the time of (standard protocol or Std) or 4 months after (delayed protocol or Del) kidney transplantation. Column 3 indicates the number of days during which the kidney transplants had been rejection-free at the time of initiation of IL-2 treatment. The degree of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) gene matching between donors and recipients is shown in column 5 (complete MHC genotyping data are presented in Figure S1). For MHC class I, we individually considered the A and B regions on each chromosome in a given recipient/donor pair, assigning a value for degree of MHC class I matching of 0–4, with 0 indicating no sharing of A or B regions and 4 indicating sharing of both A and both B regions between recipient and donor. MHC class II DR and DQ alleles were considered as a whole given that none of the monkeys displayed any recombination between these two genes. Thus, values for degree of MHC class II matching range from 0 to 4, with 0 indicating no sharing of DP or DQ/DR and 4 indicating sharing of both DP and DQ/DR alelles. The last column indicates histological features of kidney transplants examined before recipients’ administrations with IL-2 (CHR corresponds to chronic humoral rejection).

Flow cytometric analyses, detection of chimerism, and cell sorting

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), peripheral lymph nodes, spleen, and bone marrow cells were labeled with a combination of the following mAbs: CD3 PerCP (SP 34-2), CD4 PerCP (L-200), CD8 PerCP (SK1), CD8 APC (SK1), CD95 FITC (DX2), CD95 APC (DX2), and CD28PE (CD28.2) (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). Lymphocytes from the animals treated with anti-CD8 mAbs were stained with anti-CD8-PE (DK25, Dako, Inc., Carpenteria, CA). For chimerism analyses, we used an anti-MHC class I HLA mAb (H38, One Lambda, Inc, CA) reacting specifically with donor MHC class I antigens. To assess intracellular protein expression of FOXP3 (PCH101), Ki67 (B56) and CD152 (BNI3), cells were permeabilized using fixation/permeabilization solution (eBioscience). The fluorescence of the stained samples was analyzed using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer and FlowJo software. For assessing memory cell function, fresh PBMCs were gated on lymphocytes and sorted into CD16−CD95−CD28+ naïve and CD16−CD95+CD28low/high memory T cell populations using a FACS Vantage cell sorter (BD Immunocytometry System). The purity of sorted cells was consistently > 95%, as previously described (32).

Measurement of T cell–mediated alloresponses by ELISPOT

ELISPOT plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA) were precoated with 5 µg/mL of capture antibodies against γIFN (Mabtech, Sweden) in PBS and stored overnight at 4°C. Purified recipient’s T cells were co-cultured with an equal number of irradiated donor PBMCs as stimulators (1.5 × 105 cells/well), or unstimulated in medium alone, or with PHA at 1 µg/mL. After 44h of incubation, biotinylated detection antibodies (Mabtech, Sweden) were added and the spots were revealed and counted, as described elsewhere (8).

Histological analyses

The recipients, which developed irreversible rejection, were euthanized and subjected to autopsy. Biopsy, nephrectomy and autopsy sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and periodic acid Schiff (PAS) stains and scored in coded samples, using Banff 2003 and CCTT criteria. Polyclonal anti-C4d (Biomedica, Vienna) was used to detect C4d in paraffin-embedded tissues (33,34). The following antibodies were used: polyclonal rabbit anti-human CD3 (Biocare, Concord, CA, CM153A), anti-CD4 mAb (BC/IF6, Biocare, CM153A), anti-CD8 mAb (BC/IA5, Biocare, CM154A), anti-human KI67 mAb (MIB-1, Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and the clone FJK-16S anti-mouse/rat FOXP3 (eBioscience). All tissue samples were stained with PAS (20 × magnification).

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). p-values were calculated using a paired t-test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

IL-2 restores anti-donor in vitro responses of T cells obtained from monkeys tolerant of kidney allografts

In monkeys, tolerance of kidney allografts induced via transient donor multilineage hematopoietic chimerism is associated with donor-specific T cell unresponsiveness (35). In the absence of durable donor stem cell engraftment, it is plausible that tolerance relies primarily on peripheral suppression rather than thymic deletion of donor-specific T cells. This implies that tolerant monkeys possess some donor-reactive T cells whose activation could be restored under appropriate conditions. To address this, we isolated peripheral blood T cells from a series of monkeys (n = 6), which had accepted kidney allografts for more than a year without immunosuppression (Table 1). These T cells, as well as control T cells collected pretransplantation, were tested by ELISPOT for their γIFN secretion after 48h exposure to autologous, donor or third-party stimulator cells. Pretransplantation, activated T cells secreting γIFN were detected with allogeneic donor and third-party antigen-presenting cells (APCs) but not autologous APCs nor medium, as is regularly observed in primary mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLR) (36). One to ten years after transplantation, tolerant monkeys displayed no or suboptimal responses to donor stimulators even though the response to third-party was maintained (Figure 1). Next, the same in vitro MLR assays were performed in the presence of serial concentrations of recombinant human IL-2 ranging from 2.5 × 10−2 to 250 pg/mL. At 2.5 × 10−2 pg/mL and 2.5 × 10−1 pg/mL, IL-2 had no effect (Figure 1). Conversely, concentrations of 2.5 pg/mL induced a slight increase of T cell responsiveness to donor and third-party allogeneic stimulator cells but not to self-APCs. Finally, at higher concentrations (25–250 pg/mL), the anti-donor alloresponse was fully restored while enhanced responses to third-party APCs and some responses to self-APCs were now detected (Figure 1). This demonstrates a lack or incomplete depletion of pro-inflammatory donor-specific T cells in these otherwise tolerant monkeys.

Figure 1. In vitro exposure to exogenous IL-2 restores alloresponses by T cells isolated from tolerant monkeys.

Peripheral blood T cells from four tolerant monkeys were collected either pretransplantation or 1–10 years after acceptance of kidney allografts and cultured for 40 h in vitro with medium or irradiated stimulator cells derived from the recipient, the donor, or a third-party monkey. The posttransplant mixed lymphocyte reactions were conducted either in the absence of IL-2 or with serial concentrations of IL-2 (ranging from 2.5–25 000 IU/mL) as indicated on the X-axis. The frequencies of activated T cells producing γIFN were measured using ELISPOT. The results are expressed as numbers of γIFN spots per million T cells ± SD and are representative of four monkeys tested individually. p values were calculated by comparing the results obtained with and without IL-2. *Corresponds to p < 0.05 and **corresponds to p < 0.01.

In vivo IL-2 administration breaks tolerance to kidney allografts in monkeys

The observation that IL-2 restored in vitro alloreactivity of T cells from tolerant monkeys prompted us to investigate the effect of its in vivo administration on kidney graft survival and functions. We selected four monkeys that had been transplanted with an MHC-mismatched kidney (Figure S1) and treated with our mixed chimerism protocol (see Methods) either at the time of (M2800) or 4 months after renal transplantation (M2108, M6007, and M8907) (Table 1). These monkeys were tolerant of their allografts in that they had displayed stable creatinine levels (Cr: 1.0–2.0) for 1–10 years after withdrawal of immunosuppression. Furthermore, serial allograft biopsies showed no histological signs of acute cellular rejection (ACR) or chronic humoral rejection (CHR), although renal graft biopsies from M6007 revealed mild features of CHR (Figure S2). It is also noteworthy that, despite lack of tissue damage or inflammation, some mononuclear cell aggregates were detected in 3/4 monkeys (Table 1 and Figure S2). Each monkey received multiple daily subcutaneous injections of IL-2 cytokine ranging from 0.1 to 3 × 106 IU/m2. Administrations of 0.1 × 106 and 0.3 × 106 IU/m2 IL-2 doses had essentially no effect on Cr levels in M6007 (Figure 2A). In contrast, injection of 0.6 × 106 IU/m2 IL-2 induced a rapid and dramatic rise of Cr levels (Figure 2A). In fact, 0.6 × 106 IU/m2, which rapidly achieved a 200 pg/mL serum concentration (Figure S3), proved to be the minimum dose required to instigate kidney graft dysfunction in M6007. Confirming that there was dose dependency of IL-2 in inducing graft dysfunction, we decided to treat the other tolerant animals with 1 × 106 IU/m2 IL-2. Most importantly, histological examination of kidney allografts from the monkeys displaying rising Cr levels revealed the presence of severe endothelialitis, tubulitis, inflammatory cell infiltration and arterial vasculopathy, which are characteristic features of acute cellular rejection. Figure 2B–E shows representative results obtained with graft biopsies collected from M2108 (ACR grade 2). Similar histological features were observed with samples harvested from the three other recipients (Figure S4). Of note, one animal (M2800), which had maintained a tolerant state for more than 10 years without ongoing immunosuppression, did not show signs of rejection with IL-2 doses up to 1.5 × 106 IU/m2 but ultimately rejected its renal allograft upon administration of 3 × 106 IU/m2 of IL-2 cytokine (Figure 2A). It is noteworthy that no inflammation or other pathological signs were noticed in other organs (liver, pancreas, and thyroid glands). Importantly, IL-2 injections of a naïve control monkey induced no Cr level increase and no renal inflammation or tissue damage (data not shown). Therefore, in tolerant animals, IL-2 injections did not cause damage of the kidney allografts through a nonspecific inflammatory or autoimmune process.

Figure 2. IL-2 injections induce acute cellular rejection of kidney allografts in tolerant monkeys.

Four tolerant monkeys, which had displayed stable Cr levels for over 2–10 years after withdrawal of immunosuppression, received multiple subcutaneous injections of IL-2, as indicated in (A). The horizontal black bars (above each graph) indicate the doses of IL-2 administered (ranging from 0.1 to 3 × 106 IU/m2) and the duration of treatment for monkeys M6007, M2108, M8907, and M2800. Serum Cr levels (mg/dl) were recorded at different time points posttransplantation (before or after IL-2 injections). (B–E) Histological examination of the kidney allograft biopsies from monkey M2108 collected pre-IL-2 injection (B) revealed normal glomeruli, no endothelialitis in arteries and a few cell aggregates containing essentially CD3+CD4+ T cells, a few CD3+CD8+ T cells and virtually no CD20+ B cells (data not shown). Renal graft tissues examined after IL-2 injections (C–E) show acute cellular rejection (ACR, grade 2), with diffuse inflammation (C), renal artery endothelialitis (D, arrows), and vasculopathy (E). Histology results of kidney allografts from monkey M2800, M6007, and M8907 are shown in Figure S4. Tx, transplantation.

Increased frequencies of Tregs and effector memory T cells in monkeys treated with IL-2

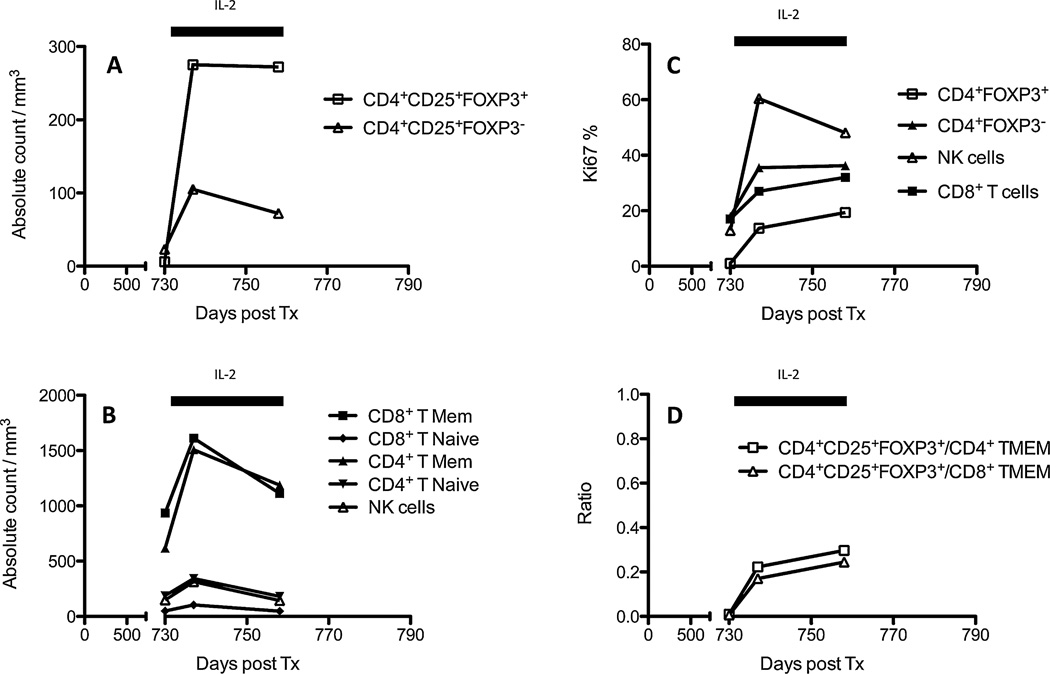

Low-dose IL-2 administration expands preferentially Tregs exhibiting the high-affinity IL-2 receptor (α–β–γ) CD25 (28,37). Nevertheless, it is possible that such treatment can also stimulate other leukocytes, including NK and some memory T cells, since some of them express CD25 as well (38,39). To test this, we measured the frequencies of various leukocyte subsets in the peripheral blood of each monkey before and during the course of IL-2 treatment. Figure 3 shows representative data obtained with M2108. Indeed, in M2108, we did detect a substantial increase in the frequency of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cells (Tregs) but also CD4+CD25+FOXP3− (Figure 3A). Actually, the number of both CD4+ and CD8+ (CD3+CD95+CD28+/−) memory T cells (TMEMs) rose dramatically within a few days after IL-2 administration (Figure 3B). Conversely, the frequencies of NK cells and CD4+ naïve T cells increased only marginally (Figure 3B). Nevertheless, over 60% of NK cells exhibited a high Ki67 expression, suggesting their ongoing proliferation (Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained with the other monkeys (Figure S5). Therefore, in addition to its effect on Tregs, low-dose IL-2 injection increased the number of TMEMs and some NK cells in monkeys’ peripheral blood.

Figure 3. Frequencies of leukocyte subsets after IL-2 injections.

Figure 3 shows the frequencies of different leukocyte subsets (A and B, number of cells/mm3 of blood) and their proliferation status (C, Ki67 expression) measured by FACS at different time points in the peripheral blood of M2108 prior to and during the course of IL-2 treatment. The horizontal black bars indicate the duration of the IL-2 treatment (1 × 106 IU/m2). (A) The frequencies of CD4+CD25highFOXP3− T cells (effector T cells) and CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ (regulatory T cells). (B) The frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing either a naïve (CD95−) or memory (CD95+) phenotype, and the number of NK cells. (C) The percentages of Ki67-expressing cells among CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells. The results are representative of six monkeys tested individually (see additional data in Figure S4). Tx, transplantation.

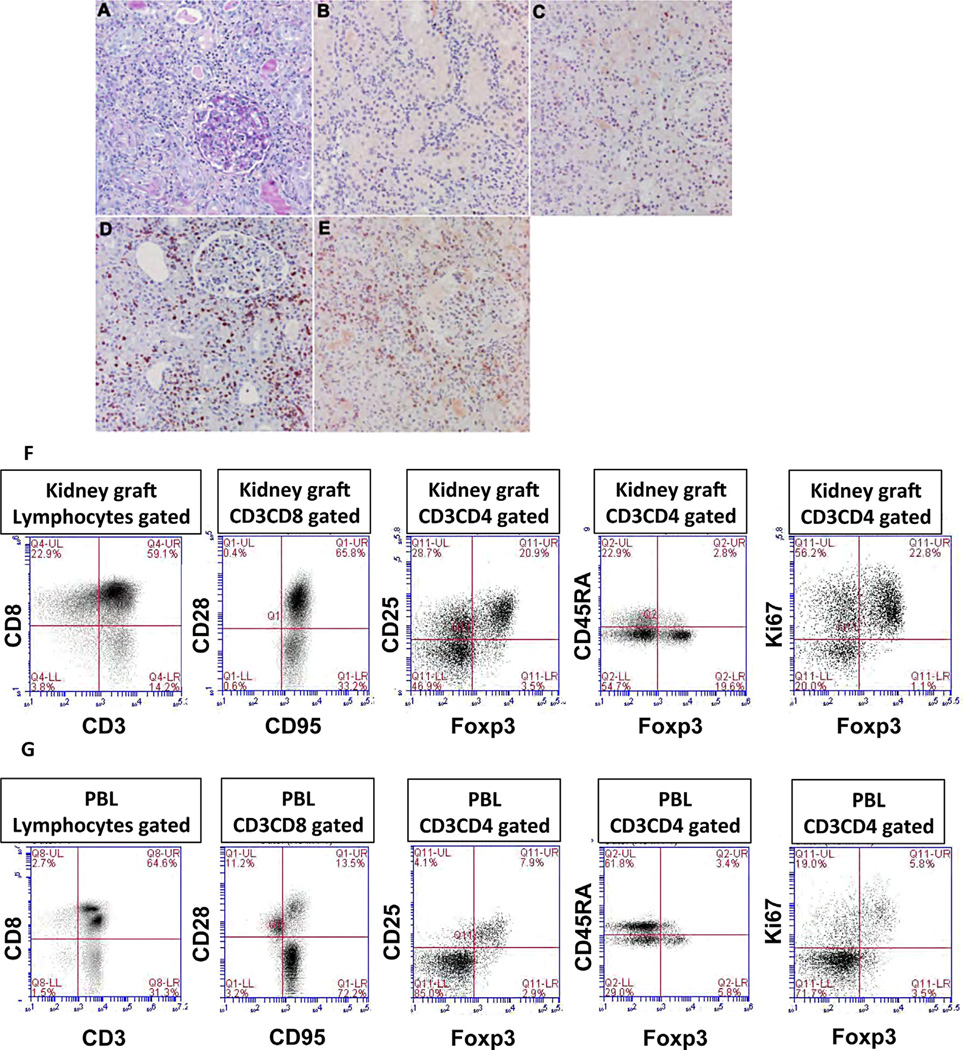

Next, peripheral blood and explanted kidney grafts were analyzed for the presence of different leukocyte subsets one day after the last IL-2 injection. Histological examination and immunostaining of kidney allografts revealed the presence of large numbers of CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, and FOXP3+ cells (Figure 4B–E, Figure 4A shows PAS staining). FACS analysis of lymphocytes isolated from kidney allografts showed that 17–20% of T cells expressed CD4, comprised primarily of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs being activated (CD45RA−) and/or proliferating (KI67+) (Figure 4F). On the other hand, the majority of T cells (50–60%) were CD8+CD95+CD28+ central memory T cells (Figure 4F). Examination of PBLs (Figure 4G) revealed two major differences: 1) most CD8+ T cells were CD95+CD28−, i.e. effector memory T cells, and 2) much fewer FOXP3− effector T cells and FOXP3+ Tregs were detected among CD4+ T cells (Figure 4F and G, middle and right panels). These results suggest that both intragraft TMEM and Tregs may be derived from a local expansion rather than infiltration from peripheral blood lymphocytes.

Figure 4. Further characterization of leukocyte subsets present in explanted kidney allografts and peripheral blood.

Histological examination and FACS were used to assess the presence and phenotype of different leukocyte subsets isolated from kidney allografts and peripheral blood during IL-2 treatment. Figure 4 shows the presence and distribution of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells as well as cells expressing FOXP3 within renal tissue allografts undergoing acute cellular rejection (ACR2) and displaying severe tubulitis, tubular necrosis, interstitial hemorrhage, and endothelialitis (not shown). (A) (PAS) shows interstitial inflammation; (B) shows rare FOXP3 staining cells; (C) shows interstitial CD8-positive T cells; (D) shows positive interstitial CD3 T cells; and (E) shows CD4-positive interstitial T cells. The first two panels of (F) (graft) and (G) (peripheral blood) show FACS profiles describing the presence of different T cell subsets, including CD3+ T cells, naïve (CD95−CD28+), and memory (central TMEM: CD95+CD28+ and effector TMEM: CD95+CD28−). The next three panels show the frequencies of regulatory T cells, CD4 gated, Tregs: CD25+FOXP3+, either resting (CD45RA+) or activated (CD45RA−) and their proliferative status examined through their coexpression of FOXP3 and Ki67 markers. These figures were obtained from the renal graft of M8907 (explanted after 14 days of IL-2 injections).

In vivo IL-2 administration restores pro-inflammatory T cell alloimmunity in tolerant monkeys

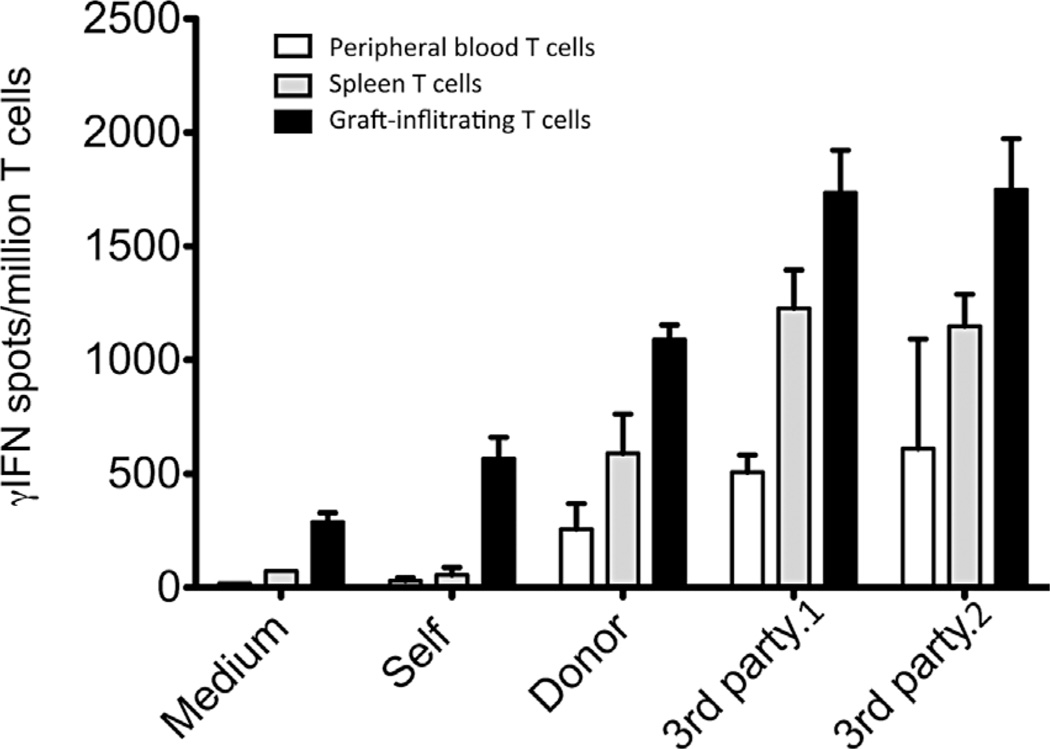

T cells isolated from the peripheral blood, spleen, and kidney allografts of two recipients whose grafts had been explanted at the time of autopsy (after a 14-day course of IL-2 injections) were sorted using MACS beads and tested by ELISPOT for their secretion of γIFN with or without challenge with irradiated APCs of self-, donor, or third-party origin (direct alloresponse), a type of response previoulsy shown to be mediated primarily by CD8+ memory T cells (32). In the absence of any stimulus (medium) or with self-APCs, some γIFN-producing T cells (200–500 cells/million T cells) were detected in the graft, indicating that these T cells were already in an activated state at the time of their collection (Figure 5, solid bars). Higher frequencies of γIFN-secreting cells (>1000 cells/million T cells) were recorded with graft-infiltrating T cells as well as peripheral blood (white bars) and spleen (grey bars) T cells challenged in vitro with allogeneic APCs derived either from the donor or two distinct third-party monkeys (3rd party 1 and 2) but not with autologous APCs (Figure 5). Therefore, IL-2 injections triggered the activation of some pro-inflammatory alloreactive T cells, including anti-donor T cells, detectable in the transplant, peripheral blood and spleen.

Figure 5. Restoration of alloresponses by T cells following IL-2 treatment.

After a 14-day course of IL-2 treatment, T cells from the peripheral blood (white bars), spleen (shaded bars), and explanted kidney allografts (solid bars) were isolated from two monkeys and tested for their ability to mount a direct alloresponse. The frequencies of T cells producing γIFN when incubated for 48h with allogeneic donor or two distinct third party allostimulators (3rd party.1 and 3rd party.2) were investigated by ELISPOT. In addition, pro-inflammatory responses by T cells exposed to control self-APCs or medium were measured. The results are expressed as numbers of γIFN spots per million T cells ± SD and are representative of two monkeys (M6007 and M8907) tested individually.

Cessation of IL-2 treatment restored allograft acceptance

In a next set of experiments, IL-2 treatment (106 IU/m2) was discontinued in three monkeys whose serum Cr levels had reached a value of 2–3 (M2800, M6007, and M4109). Typically, elevated Cr levels reveal an advanced stage of renal dysfunction associated with substantial tissue damage. Figure 6 shows representative data obtained with M4109. Arrow heads indicate the timing of graft biopsies. Remarkably, the Cr levels returned to normal values within 7 days after cessation of IL-2 injections (Figure 6A). Likewise, Cr levels of M2800 and M6007 returned to their original values (1.3 and 2.2, respectively) within 14 days after the last IL-2 injectiuon. Furthermore, graft biopsies performed 2 months after withdrawal of IL-2 cytokine showed minimal inflammatory cell infiltrates and virtually no tissue damage (Figure 6B–D). Two months after its Cr level had returned to normal, M4109 was injected with a second 14-day course of IL-2 treatment, which resulted in a rapid re-increase of its serum Cr concentration (Figure 6A). Therefore, discontinuation of IL-2 interrupted the rejection process and allowed the recovery of kidney allograft structure and function without the need for reinstitution of immunosuppressive therapy.

Figure 6. Reversal of rejection after cessation of IL-2 treatment.

IL-2 treatment was discontinued in three monkeys shortly after serum Cr levels had risen to 2–3 mg/dl (M4109, M2800, and M6007). (A) Serum Cr levels (mg/ml) for M4109 measured at different time points before, during and after IL-2 administration (106 IU/m2). After recovery of a normal Cr level, this animal received another session of 14 day-course of IL-2 treatment, which showed the same pattern of serum Cr levels. The horizontal bars indicate the duration of the IL-2 treatment. (B) (day 525), (C) (day 553), and (D) (day 615) show histological features of renal graft biopsies collected from M4109. (B) Before IL-2 treatment without rejection. (C) During IL-2 treatment with acute cellular rejection (ACR grade 1) (infiltrate with an arrow). (D) 2 months after cessation of IL-2 treatment without rejection.

Effect of anti-CD8 antibody treatment on IL-2-mediated rejection

The high frequency of activated alloreactive CD8+ memory T cells present in allografts undergoing rejection prompted us to test the contribution of these cells in IL-2-mediated tolerance breakdown. Two monkeys (M4109, whose graft had recovered after cessation of IL-2 treatment and M5710) (Table 1) were injected with an anti-CD8 depleting antibody (cM-T807) before the first IL-2 injection and then twice a week during the course of IL-2 treatment (106 IU/m2). It is important to note that these two animals differ in that M5710 but not M4109 displayed DSA at the time of IL-2 and anti-CD8 mAb injections (Figure S6). CM-T807 administration resulted in a rapid and complete elimination of peripheral blood CD8+ T cells in both monkeys (Figure 7A and B). In monkey M4109 (Figure 7A), despite IL-2 repeated injections, no Cr increase was observed. Histological examination of graft biopsies from M4109 revealed the absence of CD8+ T cells, whereas significant numbers of CD4+ T cells were observed. Nevertheless, minimal inflammation was noted in its transplant (Figure 7C), and C4d staining (indicating complement deposition) was negative (Figure 7D). In contrast, in M5710, while anti-CD8 mAb depleted CD8+ T cells, it did not avert rejection of the kidney allograft whose histology was typical of acute humoral and cellular rejection (Figure 7E: Capillaritis, hemorrhage, Figure 7F: C4d positive). Therefore, depletion of CD8+ T cells was sufficient to avoid IL-2–mediated rejection in tolerant monkey M4109 but it did not prevent humoral rejection of monkey M5710 that displayed DSA prior to IL-2 administration.

Figure 7. Effects of anti-CD8 mAb pretreatment on IL-2–mediated rejection.

Two tolerant monkeys (A, M4109; B, M5710) were injected with an anti-CD8 depleting antibody (cM-T807) prior to IL-2 administration and then twice a week during the course of IL-2 treatment (106 IU/m2). Of note, M4109 was studied in the previous experiment. The frequencies of CD4+ (solid triangles) and CD8+ (solid squares) memory T cells (TMEM) as well as the Cr levels (dotted blue lines) were measured at different time points after injection of anti-CD8 mAbs. The arrow heads indicate the times at which renal biopsies were obtained. (C–F) Histological features of renal graft biopsies. (C) (M4109) No acute cellular rejection. (D) No C4d staining of the peritubular capillaries. (E) (M5710) Acute rejection (ACR1) and acute humoral rejection (AHR) with acute glomerulitis (arrow). (F) Peritubular capillary C4d staining in M5710 (arrows). Tx, transplantation.

Discussion

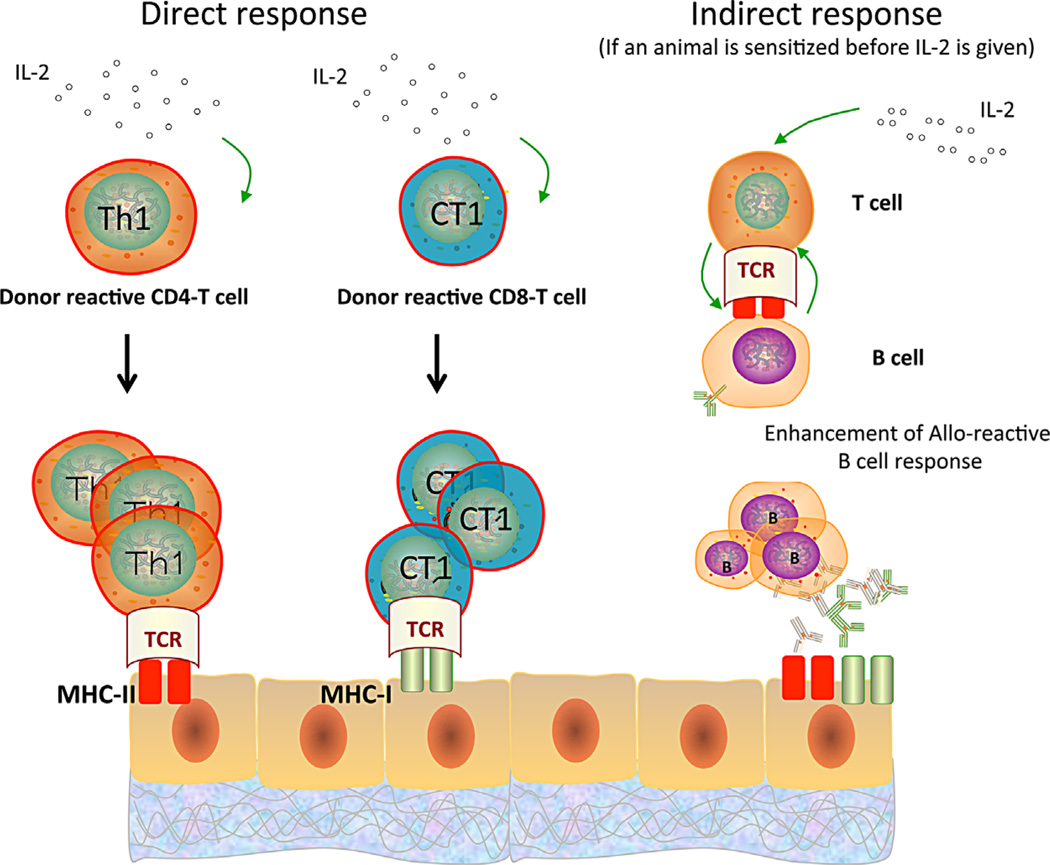

It is likely that CD8+ cells play an essential role in tolerance breakdown since IL-2–mediated rejection was prevented by the administration of depletive anti-CD8 antibodies. This corroborates previous reports showing that IL-2 mediates secondary expansion of CD8+ effector memory T cells (40,41) via a process dependent on reactivation of CD4+ memory T cells and the generation of IL-7Rα–expressing cells (42). We surmise that, in our study, CD4+ memory T cells activated directly and/or indirectly contributed to loss of tolerance by causing secondary expansion of donor-specific CD8+ effector memory T cells and enhancing alloantibody production by B cells (depicted in Figure 8). Actually, no donor-specific antibodies (DSA) were detected pre- and post-IL-2 injections in tolerant monkeys, which indicates that IL-2 alone is not sufficient to abrogate B cell tolerance. In contrast, circulating DSA were enhanced, characterized by the increase of MFI in flow cross-match test after IL-2 administration in M8907 and M6007, which had possessed DSA before IL-2 injections (Figure S6). This indicates that IL-2 activates B cells–producing donor antibodies, if present, presumably through indirect activation of some allospecific CD4+ T cells (Figure 8). In addition, IL-2 could enhance expression of donor MHC and costimulation receptors by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and thereby promote allorecognition and reactivation of some donor-specific T cells. Finally, we cannot rule out that IL-2 may have exerted some of its effect in these monkeys by expanding and potentiating NK cells that are comprised of many CD8+ cells expressing CD25 (38). However, preliminary experiments performed on one monkey (M3312) treated with an anti-CD3 immunotoxin showed that in vivo depletion of CD3+ T cells abrogated IL-2–mediated tolerance breakdown, despite NK cell expansion (Figure S7).

Figure 8. Possible mechanisms involved in IL-2–mediated breakdown of transplant tolerance.

In tolerant monkeys, IL-2 reactivates undeleted pro-inflammatory alloreactive CD4+ (TH1) and CD8+ (CT1) memory T cells, which react in a direct fashion to allogeneic major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules displayed on graft donor cells (left and middle panels). In addition, IL-2 is likely to stimulate T cells (presumably CD4+ T cells) recognizing donor antigens through indirect allorecognition, which could provide help for the activation/differentiation of memory B cells into alloantibody- producing plasma cells (right panel).

It is noteworthy that prior to IL-2 administration, five of the six accepted renal transplants examined in this study (Table 1) contained cell aggregates comprised mainly of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The presence of ectopic lymphoid accumulations called tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) is regularly observed during the course of chronic inflammation triggered by autoimmunity or infections (43–45). Although TLS are regularly observed in transplanted organs, their role in rejection and/or tolerance is still unclear. Studies from F. Lakkis have provided compelling evidence of the contribution of TLS in chronic rejection of cardiac allografts (46,47). On the other hand, Treg rich organized lymphoid structures or “TOLS,” whose formation is driven by TGF-β, have been associated with tolerance in some transplant models (16,48). In this study, IL-2 administration induced γIFN secretion by intragraft donor-specific T cells (Figure 5). It is likely that reactivation of these previously “dormant” T cells led to rejection. It is important to note that in contrast to the five recipients described above, no leukocyte aggregates were detected in monkey M2800, which had accepted its renal allograft for over ten years. In fact, much greater IL-2 doses were required to disrupt tolerance in this monkey (3 × 106 IU/m2), which suggests that it had achieved a more robust state of tolerance. We surmise that exposure of this monkey to such higher doses of IL-2 also elicited rejection via a nonspecific process involving systemic inflammation and autoimmunity.

It is somewhat remarkable that cessation of IL-2 administration aborted the process of allograft rejection. Cr levels rapidly returned to normal values and renal biopsies performed two months after interruption of cytokine injections showed no inflammatory cell infiltrates and minimal tissue damage. This shows that IL-2 was more than the trigger of tolerance breakdown but that its continuous presence was necessary to perpetuate the process leading to irreversible allograft destruction. It is possible that upon IL-2 withdrawal, pro-inflammatory T cells returned to an anergic state while Tregs became reactivated. Interestingly, a study by Schietinger et al has revealed that tolerant T cells have a tolerance-specific gene profile that can be temporarily overridden under lymphopenic conditions but is inevitably reimposed upon lymphorepletion, even in the absence of tolerogen (49). Together with our study, this suggests that reestablishment of tolerance is dictated by epigenetic memory.

Expansion of CD25high Tregs and upregulation of FOXP3 expression amid primate T cells after administration of low-dose IL-2 have been documented by us and others (26,28,37,50). Actually, daily injections for 3 consecutive months of IL-2 doses ranging from 2 × 105 to 1.5 × 106 IU/m2 were shown to expand FOXP3+ Tregs and ameliorate chronic GVHD in patients transplanted with allogeneic bone marrow cells (29). At first glance, it may appear contradictory that a similar regimen elicited secondary inflammatory alloimmunity and abolished transplant tolerance in our monkeys. The fact that our monkeys received MHC-mismatched allografts while the GVHD patients were infused with MHC-identical bone marrow cells may explain this apparent discrepancy. Indeed, at the time of IL-2 administration, our monkeys displayed high frequencies of donor MHC–specific memory T cells, which were presumably absent in the patients suffering chronic GVHD. In our model, we surmise that reactivation of effector pro-inflammatory memory T cells overpowered the stimulatory effects of IL-2 on some Tregs. In addition, the preferential expansion/activation of Tregs in GVHD patients may be partly due to their leukopenic state at the time of IL-2 treatment. Altogether, these observations indicate that whether low-dose IL-2 administration is beneficial or detrimental to tolerance of alloantigens in transplantation is context-dependent.

In summary, our study shows that, despite its ability to induce Treg expansion, low-dose IL-2 injection led to rejection of renal allografts that had survived long-term without maintenance immunosuppression after induction of transient mixed chimerism in monkeys. This process was associated with the reactivation and expansion of alloreactive effector memory T cells detected in both recipients’ lymphoid organs and in the graft itself. This suggests that transplant tolerance induced via this procedure is metastable in that it may be disrupted by any combination of circumstances such as infection or inflammation, which can cause IL-2 release; an observation that has important implications for current kidney-transplanted patients rendered tolerant using a similar mixed chimerism protocol (51). Encouraging, however, was the observation that cessation of IL-2 injections applied immediately after a rise in serum creatinine was not only sufficient to prevent progressive kidney graft rejection but also to reinstate immunosuppression-free allograft survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH: U19 AI102405 and P01HL18646.

Abbreviations

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- GVHD

graft-versus-host-disease

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MLR

mixed lymphocyte reaction

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- TLS

tertiary lymphoid structure

- TOLS

Treg-rich lymphoid structure

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Figure S1: MHC haplotypes of donor–recipient pairs.

Figure S2: Presence of leukocyte aggregates in accepted kidney allografts of the six transplanted animals used in this study.

Figure S3: Serum IL-2 concentrations measured after IL-2 injections of monkeys.

Figure S4: Histological features of kidney allografts collected post-IL-2 injections in monkeys, M2800, M6007 and M8907.

Figure S5: Frequencies of different leukocyte subsets in monkeys M6007, M8907 and M2800.

Figure S6: Detection of donor-specific antibodies pre- and post-IL-2 treatments.

Figure S7: Effect of CD3+ T cell depletion on tolerance breakdown.

References

- 1.Sykes M, Sachs DH. Mixed allogeneic chimerism as an approach to transplantation tolerance. Immunol Today. 1988;9:23–27. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(88)91352-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qin SX, Cobbold S, Benjamin R, Waldmann H. Induction of classical transplantation tolerance in the adult. J Exp Med. 1989;169:779–794. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomita Y, Khan A, Sykes M. Role of intrathymic clonal deletion and peripheral anergy in transplantation tolerance induced by bone marrow transplantation in mice conditioned with a nonmyeloablative regimen. J Immunol. 1994;153:1087–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan A, Tomita Y, Sykes M. Thymic dependence of loss of tolerance in mixed allogeneic bone marrow chimeras after depletion of donor antigen. Peripheral mechanisms do not contribute to maintenance of tolerance. Transplantation. 1996;62:380–387. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199608150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharabi Y, Abraham VS, Sykes M, Sachs DH. Mixed allogeneic chimeras prepared by a nonmyeloablative regimen: Requirement for chimerism to maintain tolerance. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1992;9:191–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams AB, Williams MA, Jones TR, et al. Heterologous immunity provides a potent barrier to transplantation tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1887–1895. doi: 10.1172/JCI17477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valujskikh A, Lakkis FG. In remembrance of things past: Memory T cells and transplant rejection. Immunol Rev. 2003;196:65–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-065x.2003.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadazdin O, Boskovic S, Murakami T, et al. Host alloreactivememory T cells influence tolerance to kidney allografts in nonhuman primates. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:86ra51. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Colvin RB, et al. Mixed allogeneic chimerism and renal allograft tolerance in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation. 1995;59:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawai T, Sogawa H, Boskovic S, et al. CD154 blockade for induction of mixed chimerism and prolonged renal allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1391–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadazdin O, Boskovic S, Wee SL, et al. Contributions of direct and indirect alloresponses to chronic rejection of kidney allografts in nonhuman primates. J Immunol. 2011;187:4589–4597. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benichou G, Tonsho M, Tocco G, Nadazdin O, Madsen JC. Innate immunity and resistance to tolerogenesis in allotransplantation. Front Immunol. 2012;3:73. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed EB, Daniels M, Alegre ML, Chong AS. Bacterial infections, alloimmunity, and transplantation tolerance. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2011;25:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed EB, Wang T, Daniels M, Alegre ML, Chong AS. IL-6 induced by Staphylococcus aureus infection prevents the induction of skin allograft acceptance in mice. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:936–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaRosa DF, Rahman AH, Turka LA. The innate immune system in allograft rejection and tolerance. J Immunol. 2007;178:7503–7509. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyajima M, Chase CM, Alessandrini A, et al. Early acceptance of renal allografts in mice is dependent on foxp3(+) cells. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1635–1645. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kingsley CI, Karim M, Bushell AR, Wood KJ. CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells prevent graft rejection: CTLA-4- and IL-10-dependent immunoregulation of alloresponses. J Immunol. 2002;168:1080–1086. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood KJ, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in transplantation tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:199–210. doi: 10.1038/nri1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsang JY, Tanriver Y, Jiang S, et al. Indefinite mouse heart allograft survival in recipient treated with CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells with indirect allospecificity and short term immunosuppression. Transplant Immunol. 2009;21:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cesana GC, DeRaffele G, Cohen S, et al. Characterization of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients treated with high-dose interleukin-2 for metastatic melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1169–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDermott DF. The application of high-dose interleukin-2 for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2009;26:13–17. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monk P, Lam E, Mortazavi A, et al. A phase I study of high-dose interleukin-2 with sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and melanoma. J Immunother. 2014;37:180–186. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gianello PR, Blancho G, Fishbein JF, et al. Mechanism of cyclosporin-induced tolerance to primarily vascularized allografts in miniature swine. Effect of administration of exogenous IL-2. J Immunol. 1994;153:4788–4797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian S, Lu L, Fu F, et al. Apoptosis within spontaneously accepted mouse liver allografts: Evidence for deletion of cytotoxic T cells and implications for tolerance induction. J Immunol. 1997;158:4654–4661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zorn E, Nelson EA, Mohseni M, et al. IL-2 regulates FOXP3 expression in human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells through a STAT-dependent mechanism and induces the expansion of these cells in vivo. Blood. 2006;108:1571–1579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao W, Lin JX, Leonard WJ. Interleukin-2 at the crossroads of effector responses, tolerance, and immunotherapy. Immunity. 2013;38:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aoyama A, Klarin D, Yamada Y, et al. Low-dose IL-2 for in vivo expansion of CD4(+) and CD8(+) regulatory T cells in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:2532–2537. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koreth J, Matsuoka K, Kim HT, et al. Interleukin-2 and regulatory T cells in graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2055–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawai T, Sogawa H, Boskovic S, et al. CD154 blockade for induction of mixed chimerism and prolonged renal allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1391–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koyama I, Nadazdin O, Boskovic S, et al. Depletion of CD8 memory T cells for induction of tolerance of a previously transplanted kidney allograft. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1055–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nadazdin O, Boskovic S, Murakami T, et al. Phenotype, distribution and alloreactive properties of memory T cells from cynomolgus monkeys. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1375–1384. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Racusen LC, Colvin RB, Solez K, et al. Antibody-mediated rejection criteria—An addition to the Banff 97 classification of renal allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:708–714. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colvin RB, Cohen AH, Saiontz C, et al. Evaluation of pathologic criteria for acute renal allograft rejection: Reproducibility, sensitivity, and clinical correlation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1930–1941. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V8121930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ochiai T, Benichou G, Cosimi AB, Kawai T. Induction of allograft tolerance in nonhuman primates and humans. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4248–4253. doi: 10.2741/2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benichou G, Valujskikh A, Heeger PS. Contributions of direct and indirect T cell alloreactivity during allograft rejection in mice. J Immunol. 1999;162:352–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zorn E, Mohseni M, Kim H, et al. Combined CD4+ donor lymphocyte infusion and low-dose recombinant IL-2 expand FOXP3+ regulatory T cells following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:382–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.12.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamada Y, Aoyama A, Tocco G, et al. Differential effects of denileukin diftitox IL-2 immunotoxin on NK and regulatory T cells in nonhuman primates. J Immunol. 2012;188:6063–6070. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herndler-Brandstetter D, Schwaiger S, Veel E, et al. CD25-expressing CD8+ T cells are potent memory cells in old age. J Immunol. 2005;175:1566–1574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blachere NE, Morris HK, Braun D, et al. IL-2 is required for the activation of memory CD8+ T cells via antigen cross-presentation. J Immunol. 2006;176:7288–7300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams MA, Tyznik AJ, Bevan MJ. Interleukin-2 signals during priming are required for secondary expansion of CD8+ memory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:890–893. doi: 10.1038/nature04790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dooms H, Wolslegel K, Lin P, Abbas AK. Interleukin-2 enhances CD4+ T cell memory by promoting the generation of IL-7R alpha-expressing cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:547–557. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruddle NH. Lymphoid neo-organogenesis: Lymphotoxin’s role in inflammation and development. Immunol Res. 1999;19:119–125. doi: 10.1007/BF02786481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hjelmstrom P. Lymphoid neogenesis: De novo formation of lymphoid tissue in chronic inflammation through expression of homing chemokines. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weyand CM, Kurtin PJ, Goronzy JJ. Ectopic lymphoid organogenesis: A fast track for autoimmunity. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:787–793. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61751-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nasr IW, Reel M, Oberbarnscheidt MH, et al. Tertiary lymphoid tissues generate effector and memory T cells that lead to allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1071–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanamori Y, Ishimaru K, Nanno M, et al. Identification of novel lymphoid tissues in murine intestinal mucosa where clusters of c-kit+ IL-7R+ Thy1+ lympho-hemopoietic progenitors develop. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1449–1459. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li W, Bribriesco AC, Nava RG, et al. Lung transplant acceptance is facilitated by early events in the graft and is associated with lymphoid neogenesis. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:544–554. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schietinger A, Delrow JJ, Basom RS, et al. Rescued tolerant CD8 T cells are preprogrammed to reestablish the tolerant state. Science. 2012;335:723–727. doi: 10.1126/science.1214277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saadoun D, Rosenzwajg M, Joly F, et al. Regulatory T-cell responses to low-dose interleukin-2 in HCV-induced vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2067–2077. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Spitzer TR, et al. HLA-mismatched renal transplantation without maintenance immunosuppression. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:353–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.