Abstract

Purpose

To study the incidence of CVD in men at risk, with and without LUTS.

Methods

We searched all longitudinal studies describing the association between LUTS and CVD (mortality) in October 2013 and December 2014 using MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library Central Register. PRISMA criteria were met.

Results

We included five studies with 6027 men with LUTS and 18,993 men without LUTS in the meta-analyses, with a follow-up period varying from 5 to 17 years. Studies totalled 2780 CVD events. No clear association between CVD and LUTS was demonstrated [pooled effect size: hazard ratio 1.09 (95 % CI 0.90–1.31); p = 0.40]. Two other studies reported the association between nocturia and (CVD) mortality. CVD-specific mortality risk was approximately two times higher for Japanese men with nocturia (357 men aged 70 years and over, 5-year follow-up). A univariable association between nocturia and all-cause mortality was found in Dutch men, but not in age-adjusted analyses (1114 men aged 50–78 years, 13-year follow-up).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis conducted on longitudinal studies does not confirm LUTS to be a predictor of CVD in men without a history of CVD, despite the observed association between LUTS and CVD in cross-sectional studies.

Keywords: Ageing male, Cardiovascular diseases, Lower urinary tract symptoms, Systematic review/meta-analysis

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the leading cause of death globally and cause high morbidity [1]. The increasing prevalence of CVD in the ageing population necessitates the timely identification of people who are at risk [2]. It has been suggested that lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are associated with CVD and may predict cardiovascular events. These conditions share multiple risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, and advanced age [3–7]. If so, therapeutic interventions to improve LUTS at an early stage may be considered to prevent morbidity and mortality due to CVD. Also screening of men with LUTS on cardiovascular diseases will be meaningful.

The pathogenesis of LUTS is considered to be multifactorial, in which age-related changes in prostate, bladder structure, and bladder function seem to play a central role. Vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction in the pelvic vascular system might contribute to bladder dysfunction with age [3]. The risk factors for vascular diseases and atherosclerosis might also have an impact on LUTS via other mechanisms [8]. For instance, increased sympathetic activity and/or a1-adrenoreceptor activity is suggested as the common pathway for both hypertension and LUTS [9]. Nicotine, but also waking by nocturia [10, 11], increases the sympathetic nervous system activity and may contribute to LUTS via an increase in the tone of the prostate [12, 13]. Hypertension and heart failure can cause fluid shifts and hormonal and autonomic nervous disturbances, causing LUTS. Finally, neurogenic bladder dysfunction with detrusor underactivity can cause LUTS in patients with diabetes mellitus [3].

Previous studies already reported on the association between LUTS and CVD in cross-sectional settings, performed in both clinical and community-based populations [3–7, 9, 14, 15]. It remained unclear whether this association between LUTS and CVD reflects a true increased risk of CVD, or if it is mainly explained by, for example, age, which is strongly associated with both LUTS and CVD [1, 16]. The outcomes are heterogeneous [3–7]. More recently, longitudinal studies have been published.

To better understand the possible relationship between LUTS and CVD and to know whether LUTS is a precursor for CVD in people without a history of CVD, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis based on longitudinal studies. We were especially interested in determining whether LUTS could be considered as a predictor of CVD.

Methods

Search strategy/study selection

We conducted a systematic review of the literature. Potentially relevant studies were identified through a structured literature search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text keywords. The terms LUTS AND CVD AND (cohort studies OR longitudinal studies) were combined, using various synonyms presented in “Appendix 1”.

We identified articles eligible for further review by performing an initial screen of identified titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text review. In addition, we searched the reference list of all identified relevant publications on October 20, 2013, and repeated the complete search on December 10, 2014.

Inclusion, exclusion, and quality score criteria

Two investigators (IB and MV) independently assessed literature eligibility. Articles were considered for inclusion if: (1) the study included original data, published in a peer-reviewed journal (i.e. not review articles, or meeting abstracts); (2) the study was a cohort study (prospective cohort or historical cohort) consisting of male human adults; and (3) the authors reported the risk estimates of cardiovascular morbidity in LUTS patients compared with non-LUTS patients. Selected studies included all types of CVD, cardiovascular risk, and LUTS.

To assess the methodological quality of included studies, a structured form was used. We chose to apply a score based on a criterion list which has been previously used in systematic reviews of observational data [17, 18]. We tailored the list by adding criteria on the completeness of data on LUTS and CVD. The list included six items on external validity, five items on internal validity, and seven items on informativity (“Appendix 2”). IB and MV independently scored all items either positive (scored as 1) or negative (scored as 0).

Data extraction

Two reviewers (IB and MV) independently extracted the following information about the studies: study characteristics (study name, authors, publication year, journal, study site, follow-up years, and number of participants), participants’ characteristics (mean age or age range), main exposure LUTS (IPSS, AUA, and nocturia), main outcome cardiovascular disease/risk (morbidity, risk, types, assessed by self-report, and medical records), and analysis strategy (statistical models, covariates included in the models). Disagreement about data extraction or the quality score of the included studies was resolved by consensus. When no or insufficient information was provided in the article, earlier publications on the same study were used for collecting lacking information, if available. For pooling of data, on our request, we received additional information from two studies (personal communication—Wehrberger et al. [19] and Lin [20]). This concerned information about hazard ratios for CVD risk in men with moderate to severe LUTS, compared to men with no or mild LUTS.

Meta-analyses

We selected studies that compared the incidence of a CVD between individuals with and without LUTS. Studies including patients with only (cardiovascular) mortality as an endpoint were considered not fully representative of CVD. Therefore, we did not include these studies in the meta-analysis but analysed these studies separately.

In all analyses, we considered methodological homogeneity. If data were pooled, statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 index. In case of substantial heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 50 %), a random effects model was applied. A fixed effects model was used when I2 < 50 %. Weighted hazard ratios (HR) were presented with 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI). Statistical analysis was performed with RevMan 5.3.

Results

Selection of studies

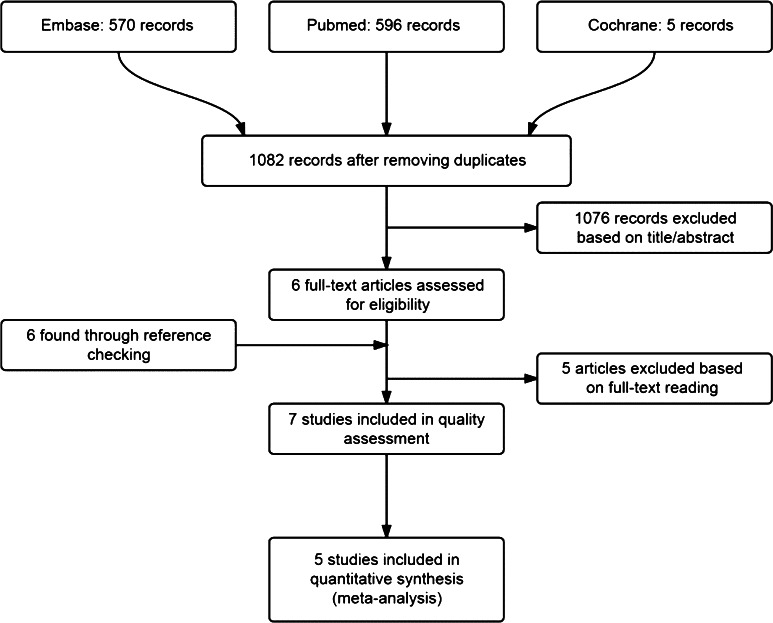

We reviewed seven studies (with 25,982 male participants) selected from 1082 initially identified publications (Fig. 1). This selection included four community-based studies [10, 19–21] and one primary care study [22]. In two other studies (1471 participants), nocturia and (CVD) mortality were assessed [23, 24]. Background information for these studies is presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection

Table 1.

General study characteristics

| Ref. no. | Year | Country | Participants | Age | Origin | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Responders/total population N/N % | Study period | Follow-up time (mean*/median~) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | 2011 | Austria | Men | Mean 47.8 (SD 11.5) | CB | Employees of large companies undergoing free of charge in. The city of Vienna. Men >30 years | Men with a history coronary heart disease, cardiac failure, intermittent claudication, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy | 2092/? | 2001–2008 | 6.1 years* (SD 1.5) |

| [10] | 2012 | USA | Men | Median 51.88; (Q1–Q3 44.8–62.8) | CB | Random sample of men aged 40–79 years in 1990, Olmsted County, MN, USA | Previous history of PCa, prostatectomy, or bladder cancer, bladder disorders or surgery, and urethral disorders or surgery | 2447/3874 (63 %) | 1990–2007 | 17.1 years~ (25th–75th: 15.2–17.4) |

| [20] | 2013 | Taiwan | Men and women | Mean 47 (SD 15) | CB | Nationwide health insurance enrolees, subjects with codes of LUTS in service claims | Subject with CVD codes | 27,318/? | 2001–2009 | 6.6 years* (SD 1.5) |

| [22] | 2014 | Netherlands | Men | Mean 56 (SD 12) | PCP | Male population aged >50, in a primary care population in the Netherlands | PCa, history of CVD | 6615/? | 1998–2008 | 8.2 years*, 11.0~ (25th–75th: 5.2–11.0) |

| [23] | 2011 | Netherlands | Men | Median 60.8 (Q1–Q3 56.0–66.2) | CB | All men aged 50–78 years from Krimpen aan den IJssel, The Netherlands | History of TURP, prostatectomy, PCa or bladder cancer, neurogenic bladder disease, or negative advice from the GP based on poor health | 1114/3924 (28.4 %) | 1995–2010 | 13.4 years~ (25th–75th: 10.3–14.1) |

| [21] | 2014 | Netherlands | Men | Mean 61.4 (SD 6.6) | CB | All men aged 50–78 years from Krimpen aan den IJssel, The Netherlands | History of prostatectomy, prostate or bladder cancer, neurogenic bladder disease, or who were unable to complete questionnaires or visit the healthcare centre | 1610/3924 (41 %) | 1995–2003 | 6.35* (range 0.1–8.34 years) total: 7945 person-years |

| [24] | 2010 | Japan | Men and women | Mean 76 (SD 4.6) | CB | All men aged >70 from Tsurugaya, Japan | Not joining the NHI system | 784/2925 (26.8 %) | 2003–2008 | 5 years* |

CB community based, PCP primary care population, CVD cardiovascular disease, GP general practitioner, PCa prostate carcinoma, NHI National Health Institute

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies: measurement instruments, applied definitions, and confounders used in the adjusted analysis

| Ref. no. | LUTS | Nocturia | CVD | Mortality | Confounders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | IPSS categories | – | ICD codes: I20–25, I60–65 | – | Age, sex, DM, cholesterol, BMI, SBP, DBP, uric acid |

| [10] | – | NVF ≥ 2 | Medical records: sudden cardiac death, MI and angiographically diagnosed coronary disease | Death certificates, autopsy reports, obituary notices, electronic death certificate data from the state of Minnesota | Age, DM, BMI, α-blockers, 5α-reductase inhibitors, OAB medications, HT |

| [20] | ICD-9-CM codes: 596.51, 788.4, 625.6, 788.32, 788.31, 788.36, 788.43, 788.33, 788.2, 788.6, 788.35, 600 | – | ICD-9 codes: 410, 411, 430, 431, 433–436 | Subjects who withdrew the NHI enrolment within 30 days after discharge from the last hospitalization were presumed dead, and the discharge date was designated as the date of death | Hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, and age |

| [22] | ICPC codes: U02, U05, U07, U13, U29, Y06, Y85 | – | ICPC codes: K74, K75, K76, K89, K90 | Medical records from the Registration Network Groningen | HT, DM, obesity, alcohol, dyslipidaemia, medication: TCA, antipsychotics, antihypertensives, diuretics, statins, LUTS medication. |

| [23] | – | IPSS NVF ≥ 2 |

– | Patient files in the GP database | Age, alcohol, tobacco, DM, albuminuria, obesity, hypertension, COPD, cardiac symptoms, |

| [21] | IPSS categories | – | ATC definitions for AMI, stroke, sudden death | Patient files in the GP database | Age, alcohol, tobacco, DM, obesity, hypertension, ED |

| [24] | – | NVF ≥ 2 | Questionnaire | NHI claims history files | Age, sex, alcohol, tobacco, DM, medication, disease history, CVD history, nephropathy, malignant disease, BMI, tranquilizer, hypnotics, diuretics, functional reach |

IPSS International Prostate Symptom Score, ICD International Classification of Diseases, NVF nocturnal voiding frequency, NHI National Health Insurance, CHD cardiac heart disease, CF cardiac failure, CI intermittent claudication, DM diabetes mellitus, BMI body mass index, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, OAB overactive bladder, HT hypertension, (A)MI myocardial infarct, GP general practitioner, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICPC International Classification of Primary Care, U02 frequency, U05 other voiding symptoms, U07 other urine symptoms, U13 other bladder symptoms, U29 other urine tract symptoms, Y06 prostate symptoms, Y85 benign prostate hypertrophy, K74 angina pectoris, K75 acute myocardial infarction, K76 other/chronic coronary heart disease, K89 transient cerebral ischaemia, K90 cerebrovascular accident, ED erectile dysfunction, ATC Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration

Methodological quality assessment and description of selected studies

Table 3 shows the results of the quality assessment. The proportions scored positive were 0.71 on external validity, 0.74 on internal validity, and 0.88 on informativity. In 89 % of the items, there was a positive agreement, whereas in 11 % of the items consensus was reached after discussion between the two reviewers. None of the studies scored positive on all validity criteria.

Table 3.

Quality score criteria

| Ref. no. | Year | External validity | Internal validity | Informativity | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | Sum | g | h | i | j | k | Sum | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | Sum | Disagreement | ||

| [19] | 2011 | + | + | − | − | − | + | 3 | − | + | + | + | + | 4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | 6 | c, i, r |

| [10] | 2011 | + | + | − | − | − | + | 3 | − | + | + | + | + | 4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 7 | i, o, r |

| [20] | 2013 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | − | + | + | + | + | 4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 7 | d, h |

| [22] | 2014 | + | + | − | − | + | + | 4 | − | + | + | + | + | 4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 7 | h |

| [23] | 2012 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | − | + | + | + | + | 4 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | 6 | c, e |

| [21] | 2014 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | − | + | + | + | + | 4 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 | r |

| [24] | 2010 | + | − | − | − | − | + | 2 | − | + | − | − | + | 2 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | 4 | j, o |

| Total | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 | |||||

| Mean | 4.3 | 3.7 | 6.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Items a–r refer to the quality score criteria listed in “Appendix 2”

LUTS and CVD

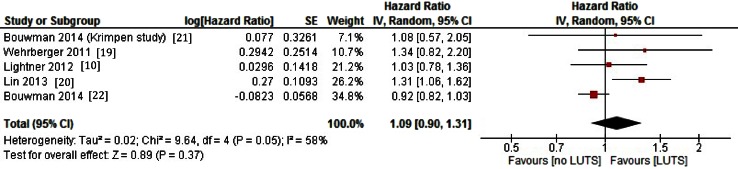

The five studies included in the meta-analysis compared CVD outcomes between in total 6027 men with LUTS and 18,993 men without LUTS. Two studies reported a median follow-up of 17.1 and 11.0 years [10, 22]; three other studies reported a mean duration of follow-up of 6.1, 6.35, and 6.6 years [19–21]. During this follow-up, a total of 2780 CVD events occurred: 646 in men with LUTS (17 %), compared to 1775 in men without LUTS (10 %). Lightner et al. [10] only report a total of 359 men with CVD in the follow-up group.

Figure 2 shows the results of the pooled analyses with an estimated hazard ratio of 1.09 (95 % CI 0.90–1.31), p = 0.40.

Fig. 2.

Risk (hazard ratio) of CVD according to LUTS status. Pooled hazard ratio with 95 % CI resulting from meta-analyses using generic inverse variance random effects model. Presentation in order of publication year

Nocturia and (cardiovascular) mortality

Two studies described the CVD mortality risk for men with and without nocturia [23, 24]. Nakagawa et al. [24] conducted a community-based observational study and followed 784 men aged 70 years and older, of whom 359 had nocturia. During a 5-year observation period, these men had a two times greater risk to die from CVD than the men without nocturia: HR 1.98, 95 % CI 1.09–3.59, p = 0.03. In this analysis, the authors adjusted for sex, alcohol, tobacco, diabetes, medication, CVD history, nephropathy, malignant disease, BMI, and functional reach.

Van Doorn et al. [23] conducted a similar observational study with 1114 men aged 50 years and older with an extended follow-up period of 13.4 years. At baseline, 731 had no nocturia and 383 had nocturia. During a median follow-up period, there was an association between nocturia and increased mortality rate in the univariable analysis (HR 1.63, 95 % CI 1.20–2.21, p = 0.002). This association between nocturia and all-cause mortality was not found in the model adjusting for age, COPD, hypertension, and smoking: the adjusted HR was 1.03 (95 % CI 0.75–1.42).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies does not confirm that LUTS is a precursor for CVD, as has been suggested from cross-sectional studies [3–7, 9, 14, 15]. This might implicate that the presence of LUTS in older men is no reason to start preventive cardiovascular treatment. At least, raising public awareness on CVD in men with LUTS seems not to have a scientific ground.

The number of available studies on this topic was limited; only seven cohort studies with 25,982 participants between LUTS and CVD, or nocturia and (cardiovascular) mortality were available for review. In general, longitudinal studies are more laborious and expensive to perform, but vital to analyse possible causal relationships. Earlier cross-sectional studies showed apparently clear association between LUTS and cardiovascular risk factors [3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 14, 15]. No inference can be made on the causality of such associations.

The results of longitudinal studies should also be considered with some caution. Especially, the applied statistical methods need to be sound. The preferred statistical method is survival analyses. In such analyses, time to event is the outcome. This is especially important for severe outcomes, such as CVD. In a very recent longitudinal study on this topic [7], authors concluded that LUTS severity predicts CVD. In that study, however, authors applied logistic regression analyses, instead of survival analyses. We believe that this statistical method is inferior to survival analyses and may have led to an overestimation of the studied association. Comparing proportions of events in study groups using odds ratios/logistic regression ignores time as an important factor [25]. Moreover, due to this difference, that study could not be included in the current meta-analysis.

Longitudinal studies may provide a temporal sequence of events required for revealing time-dependent relationships between LUTS and CVD or mortality. In this respect, we focussed on this temporal sequence and not on the reverse sequence of the possible negative impact of CVD (treatment) on the development of LUTS.

The absence of a clear association described in this review needs to be interpreted with some caution. The studies included in this review were based on general population samples, health registries, and one general practice population. In such populations, men with severe LUTS, as well as high-risk patients, may be underrepresented. For example, in the Wehrberger study, only 1 % of the participants had severe LUTS. This small group had a higher risk of CVD than men without LUTS [19]. Adding this group to the men with moderate LUTS, for the purpose of pooling the data in the current meta-analysis, revealed no significant difference compared to men without LUTS. Longitudinal studies in high-risk patients are lacking. Surprisingly, no data from secondary or tertiary care settings were found.

Second annotation is made on the applied definitions of both LUTS and CVD, which differed between studies. As defined by the European Association of Urology (EAU), LUTS is a very broad concept which incorporates a range of micturition symptoms [26]. Likewise, CVD includes a broad number of diseases, not always sharing the same aetiology. Included studies did not always specify for myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, or stroke. Being unable to find an association in our review could also be due to these different aetiologies between and within LUTS and CVD. On the other hand, from a methodological point of view, applying different definitions could enhance making firm conclusions, if a clear association would have been shown in all studies. In the current review, in only one out of five studies, a significant association was found [20].

Finally, as both LUTS and CVD are believed to have a multifactorial origin [1, 16], other possible causes of CVD, such as nicotine abuse, hyperlipidaemia, BMI, and alcohol abuse, should also be considered in studying the association between LUTS and clinical CVD. Although all studies reported implementing adjustments for confounding factors such as age, gender, and smoking status, not all known cardiovascular risk factors were included in the longitudinal analyses. This might have had impact on the described associations.

So, although our review suggests that LUTS do not predict CVD in men without a history of CVD, the association between LUTS and CVD could not be ruled out.

Next to these general concerns on the available data, some methodological issues need to be mentioned as well. We have searched relevant databases, but with our search strategy, individual studies might have been overlooked. For that reason, we also checked the reference lists. We have applied a criteria list for the methodological quality assessment, previously used in comparable reviews [17, 18]. This included some arbitrary items, for example, on the availability of follow-up percentages and information on losses to follow-up. It is impossible to provide such data, for example, from registry studies, resulting in a lower quality score for such studies. Next, for the meta-analyses, we have chosen to perform pooled analyses, despite the clinical heterogeneity present. Evaluating the separate studies, however, would have led to the same conclusions, as four of the five studies showed no association. Due to the statistical heterogeneity, we needed to adjust the analyses, by performing a random effects model. We could not perform subgroup analyses.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations addressed, we conclude that the presence of LUTS does not predict CVD in older men without a history of CVD. Raising awareness for CVD in men with LUTS in the general population seems to have no evidence base. No information was found on this association in more selective clinical samples. To further address LUTS as a possible marker of underlying CVD, high-quality prospective research in a clinical setting is needed. This should be done applying generally accepted definitions of LUTS and CVD.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wehrberger group and the Lin group of providing additional data. We thank Dr. Huib Burger, epidemiologist, for his comments on this review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standard

The manuscript does not contain new clinical studies or new patient data.

Appendix 1

Search terms used

| Keyword | Synonym |

|---|---|

| CVD | (“Cardiovascular Diseases” [Mesh:NoExp]) OR (“Heart Diseases” [Mesh:NoExp]) OR (“Arrhythmias, Cardiac” [Mesh]) OR (“Heart Arrest” [Mesh]) OR (“Heart Failure” [Mesh]) OR (“Myocardial Ischemia” [Mesh]) OR (“Pulmonary Heart Disease” [Mesh]) OR (“Vascular Diseases” [Mesh:NoExp]) OR (“Arteriosclerosis” [Mesh]) OR (“Carotid Stenosis” [Mesh]) OR (“Cerebrovascular Disorders” [Mesh]) OR (“Embolism and Thrombosis” [Mesh]) OR (“Hypertension” [Mesh]) OR (“Myocardial Ischemia” [Mesh])OR “cardiovascular disease” OR “coronary heart disease” OR “ischemic heart disease” OR “coronary artery disease” OR “hypertensive heart disease” OR “cor pulmonale” OR “cerebrovascular disease” OR “peripheral arterial disease” OR “stroke” OR “atherosclerosis” OR “myocardial ischemia” OR “acute coronary syndrome” OR “angina pectoris” OR “coronary disease” OR “coronary artery disease” OR “coronary occlusion” OR “coronary stenosis” OR “coronary thrombosis” OR “myocardial infarction” OR “sudden death” |

| LUTS | (“prostatic Hyperplasia” [Mesh]) OR (“Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms” [Mesh]) OR (“Urination Disorders” [Mesh]) OR (”Urinary bladder neck obstruction” [MeSH])OR (“Urinary Bladder, overactive” [Mesh])OR (“Polyuria” [Mesh]) OR “dysuria” OR “nocturia” OR “prostatism” OR “overactive urinary bladder” OR “overactive bladder” OR “urinary incontinence” OR “urgency” OR “Hesitancy” OR “lower urinary tract symptoms” OR “benign prostatic hyperplasia” OR “benign prostatic hypertrophy” OR “prostatic hyperplasia” OR “prostatic hypertrophy” OR “bladder outlet obstruction” OR “voiding dysfunction” OR “urinary bladder neck obstruction” OR “prostatic Hyperplasia” [Mesh] OR “Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms” [Mesh] OR “Urination Disorders” [Mesh] OR “Urinary bladder neck obstruction” [MeSH] “Urinary Bladder, overactive” [Mesh] “Polyuria” [Mesh] OR “dysuria” OR “nocturia” OR “prostatism” OR “overactive urinary bladder” OR “overactive bladder” OR “urinary incontinence” OR “urgency” OR “Hesitancy” OR “lower urinary tract symptoms” OR “benign prostatic hyperplasia” OR “benign prostatic hypertrophy” OR “prostatic hyperplasia” OR “prostatic hypertrophy” OR “bladder outlet obstruction” OR “voiding dysfunction” OR “urinary bladder neck obstruction” |

| Longitudinal studies | “Longitudinal Studies” [Mesh] OR “Longitudinal Studies” |

| Cohort studies | “Cohort Studies” [Mesh] OR “Cohort Studies” |

Appendix 2

Quality score criteria and informativitya

| External validity | |

| Selection of the study population | |

| A | Clear description of the research population?b |

| B | Inclusion and exclusion criteria described?c |

| Participants and non-responders | |

| C | Response rate >70 % or sufficient information on non-responders?d |

| D | Is there sufficient information about the follow-up percentages and comparison of who were and were not lost to follow-up? |

| Relationship with source population? | |

| E | Extrapolating results possible for the complete population?e |

| Description of the study period | |

| F | Clear description of the study period? |

| Internal validity | |

| Data collection | |

| G | Data prospectively collected? |

| Measurement instrument | |

| H | Measuring instrument for LUTSf |

| I | Measuring instrument for CVDg |

| J | Are definitions of the diseases stated? |

| Confounders | |

| K | Confounders described?h |

| Informativity i | |

| L | Clear theoretical introduction with relevant references to support the research question? |

| M | Aims of the study clearly described? |

| N | Research questions being answered? |

| O | Definition of LUTS clearly described |

| P | Definition of CVD clearly described |

| Q | Clear description of the way data were analysed? |

| R | Enough original data to evaluate their interpretation |

aItems were scored positive if clear information was presented in the articles. Unclear data are presented as “?” and consequently scored negative for the quality score summation

bClear description of source and two or more of the following: age distribution, relevant comorbidity, medication

cScored positive if both inclusion and exclusion criteria were provided

dSufficient information on non-responders: were reasons for non-response studied and presented, including information on age distribution, gender, main topic under study?

eDid the study selection procedure result in a representative sample of the study population?

fData on LUTS collected through IPSS or validated questionnaire

gData on CVD collected through validated instrument

hDescription of confounders not necessarily including actual statistical adjustment for confounders

iInformativity was not included in the quality score

Contributor Information

Iris I. Bouwman, Phone: +31.50.3632963, Email: iibouwman@hotmail.com

Maarten J. H. Voskamp, Email: maartenvoskamp@gmail.com

Boudewijn J. Kollen, Email: b.j.kollen@umcg.nl

Rien J. M. Nijman, Email: j.m.nijman@umcg.nl

Wouter K. van der Heide, Email: w.k.van.der.heide@umcg.nl

Marco H. Blanker, Phone: +31.50.3632963, Email: blanker@belvederelaan.nl

References

- 1.Laslett LJ, Alagona P, Clark BA, et al. The worldwide environment of cardiovascular disease: prevalence, diagnosis, therapy, and policy issues: a report from the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:S1–S49. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould CL, Hofman KJ. The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA. 2004;291:2616–2622. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponholzer A, Temml C, Wehrberger C, et al. The association between vascular risk factors and lower urinary tract symptoms in both sexes. Eur Urol. 2006;50:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandfeldt L, Hahn RG. Cardiovascular risk factors correlate with prostate size in men with bladder outlet obstruction. BJU Int. 2003;50:64–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karatas OF, Bayrak O, Cimentepe EUD. An insidious risk factor for cardiovascular disease: benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Cardiol. 2010;144:452. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng CF, Wong A, Li ML, et al. The prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in male patients who have lower urinary tract symptoms. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:421–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kupelian V, Araujo AB, Wittert GA, McKinlay B. Association of moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms with incident type 2 diabetes and heart disease. J Urol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu S, Tsounapi P, Shimizu T, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms, benign prostatic hyperplasia/benign prostatic enlargement and erectile dysfunction: are these conditions related to vascular dysfunction? Int J Urol. 2014;21:856–864. doi: 10.1111/iju.12501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S, Jeong JY, Choi YJ, et al. Association between lower urinary tract symptoms and vascular risk factors in aging men: the Hallym Aging Study. Korean J Urol. 2010;51:477–482. doi: 10.4111/kju.2010.51.7.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lightner DJ, Krambeck AE, Jacobson DJ, et al. Nocturia is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease and death. BJU Int. 2012;110:848–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kupelian V, Fitzgerald MP, Kaplan SA, et al. Association of nocturia and mortality: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol. 2011;185:571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohrmann S, Smit E, Giovannucci E, Platz EA. Association between markers of the metabolic syndrome and lower urinary tract symptoms in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:310–316. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michel MC, Heemann U, Schumacher H, et al. Association of hypertension with symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004;172:1390–1393. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000139995.85780.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbons EP, Colen J, Nelson JB, Benoit RM. Correlation between risk factors for vascular disease and the American Urological Association Symptom Score. BJU Int. 2007;99:97–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kupelian V, Rosen RC, Link CL, et al. Association of urological symptoms and chronic illness in men and women: contributions of symptom severity and duration—results from the BACH Survey. J Urol. 2009;181:694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapple CR, Wein AJ, Abrams P, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms revisited: a broader clinical perspective. Eur Urol. 2008;54:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prins J, Blanker MH, Bohnen AM, et al. Review Prevalence of erectile dysfunction: a systematic review of population-based studies. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14:422–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofmeester I, Kollen BJ, Steffens MG, et al. The association between nocturia and nocturnal polyuria in clinical and epidemiological studies: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Urol. 2014;191:1028–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wehrberger C, Temml C, Gutjahr G, et al. Is there an association between lower urinary tract symptoms and cardiovascular risk in men? A cross sectional and longitudinal analysis. Urology. 2011;78:1063–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin H-J, Weng S-F, Yang C-M, Wu M-P. Risk of hospitalization for acute cardiovascular events among subjects with lower urinary tract symptoms: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e66661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouwman II, Blanker MH, Schouten BWV, et al. Are lower urinary tract symptoms associated with cardiovascular disease in the Dutch general population? Results from the Krimpen study. World J Urol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00345-014-1398-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouwman II, Kollen BJ, van der Meer K, et al. Are lower urinary tract symptoms in men associated with cardiovascular diseases in a primary care population: a registry study. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Doorn B, Kok ET, Blanker MH, et al. Mortality in older men with nocturia. A 15-year followup of the Krimpen study. J Urol. 2012;187:1727–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakagawa H, Niu K, Hozawa A, et al. Impact of nocturia on bone fracture and mortality in older individuals: a Japanese longitudinal cohort study. J Urol. 2010;184:1413–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allison P (SAS institute inc. (2010) Survival analysis using SAS. 336

- 26.Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, et al. EAU guidelines on the treatment and follow-up of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol. 2013;64:118–140. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]