Abstract

Background & Aims

Few studies have evaluated the ability of laboratory tests to predict risk of acute liver failure (ALF) among patients with drug-induced liver injury (DILI). We aimed to develop a highly sensitive model to identify DILI patients at increased risk of ALF. We compared its performance with that of Hy’s Law, which predicts severity of DILI based on levels of alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase and total bilirubin, and validated the model in a separate sample.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 15,353 Kaiser Permanente Northern California members diagnosed with DILI from 2004 through 2010, liver aminotransferase levels above the upper limit of normal, and no pre-existing liver disease. Thirty ALF events were confirmed by medical record review. Logistic regression was used to develop prognostic models for ALF based on laboratory results measured at DILI diagnosis. External validation was performed in a sample of 76 patients with DILI at the University of Pennsylvania.

Results

Hy’s Law identified patients that developed ALF with a high level of specificity (0.92) and negative predictive value (0.99), but low level of sensitivity (0.68) and positive predictive value (0.02). The model we developed, comprising data on platelet count and total bilirubin level, identified patients with ALF with a C statistic of 0.87 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76–0.96) and enabled calculation of a risk score (Drug-Induced Liver Toxicity ALF Score). We found a cut-off score that identified patients at high risk patients for ALF with a sensitivity value of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.71–0.99) and a specificity value of 0.76 (95% CI, 0.75–0.77). This cut-off score identified patients at high risk for ALF with a high level of sensitivity (0.89; 95% CI, 0.52–1.00) in the validation analysis.

Conclusions

Hy’s Law identifies patients with DILI at high risk for ALF with low sensitivity but high specificity. We developed a model (the Drug-Induced Liver Toxicity ALF Score) based on platelet count and total bilirubin level that identifies patients at increased risk for ALF with high sensitivity.

Keywords: hepatotoxicity, drug-induced liver injury, DILI, Hy’s Law, acute liver failure

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) accounts for 4–6% of adverse drug reactions.1 This adverse effect is associated with increased morbidity and can lead to acute liver failure (ALF), liver transplantation, and death.2 DILI remains a major reason for withdrawal of marketed medications.3

Despite the clinical impact of hepatotoxicity, few studies have evaluated the ability of laboratory tests to predict the risk of ALF among patients with DILI. Within the clinical trials setting, the most commonly employed method to predict a drug’s likelihood to induce severe liver injury is “Hy’s Law,” which was developed from the clinical impressions of Dr. Hyman Zimmerman.4–6 Zimmerman noted that among patients with DILI, the presence of hepatocellular injury and jaundice conferred a 10% mortality rate.4 Dr. Robert Temple of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration later specified formal biochemical criteria for Hy’s Law (alanine aminotransferase [ALT] or aspartate aminotransferase [AST] levels ≥3 times upper limit of normal [ULN] plus a total bilirubin ≥2 times ULN).5, 6 However, the sensitivity, specificity and predictive value of these empiric criteria to identify DILI patients who will develop ALF have never been assessed in population-based studies. Further, it is unknown whether a prognostic model comprised of commonly measured laboratory tests can provide more accurate risk stratification than Hy’s Law criteria.

We identified patients with suspected DILI within Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) and determined which patients progressed to ALF. Within this cohort, we evaluated the ability of Hy’s Law criteria to identify incident ALF. We then contrasted the performance of Hy’s Law criteria with that of a new prognostic model comprised of commonly measured laboratory tests, which had high sensitivity to minimize the likelihood of missing ALF events in clinical practice. Finally, we identified a separate cohort of patients with DILI at the University of Pennsylvania, determined who developed ALF, and externally validated our prognostic model in this cohort.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Sources

We conducted a retrospective cohort study within KPNC, an integrated health care organization that provides inpatient and outpatient services to Northern California residents, between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2010.7 Data collected by KPNC included: demographic information; clinician-assigned outpatient and hospital diagnoses (recorded using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] codes); procedures; inpatient and outpatient laboratory results; emergency and referral services at non-Kaiser Permanente facilities; and dispensed medications. KPNC mortality databases integrate death certificate data from the Social Security Administration Death Master File.

We conducted a separate retrospective cohort study among DILI patients seen by hepatologists in the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) Gastroenterology Division between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2014. Available data included: demographic information; outpatient and hospital ICD-9 diagnoses; procedures; inpatient and outpatient laboratory results; and dispensed drugs.

The study was approved by the KPNC and Penn Institutional Review Boards.

Study Patients

KPNC Cohort

KPNC members had a clinician-recorded outpatient or hospital diagnosis of DILI (ICD-9 code 573.3 [toxic, non-infectious hepatitis] or 573.8 [chemical/drug-induced liver disorder]), ALT or AST above ULN at DILI diagnosis, and ≥18 years of age with ≥6 months of membership at DILI diagnosis. The index date was defined as the initial DILI diagnosis date.

Because other causes of acute liver injury must be ruled out before considering DILI, we excluded patients who had: 1) pre-existing liver disease diagnosis (Supplementary Table 1) prior to the index date; 2) laboratory evidence of hepatitis B, C, or D prior to the index date; and 3) acute hepatitis A or E within 30 days prior to or after the index date. We also excluded patients who had warfarin prescribed within ±182 days of the index date (preventing identification of coagulopathy due to ALF) or no laboratory tests recorded on or within 182 days prior to the index date.

KPNC patients’ follow-up began on their index date and continued until ALF, death, or 182 days after the index date (since ALF typically develops within 26 weeks of symptomatic DILI8).

University of Pennsylvania Cohort

Patients in the Penn cohort had: 1) an outpatient or hospital DILI diagnosis (ICD-9 code 573.3 or 573.8), 2) ≥18 years of age at diagnosis, and 3) no pre-existing liver disease (Supplementary Table 1). These patients’ outpatient and hospital records were reviewed by two hepatologists. DILI was confirmed if the patient had: 1) ALT or AST ≥5 times ULN on two separate occasions; 2) ingested a drug, herbal, or dietary supplement prior to DILI diagnosis, and 3) no other acute liver injury etiology.9 Follow-up began on the DILI diagnosis date and continued until ALF, death, or 182 days after the index date.

Main Study Outcome

For both cohorts, the primary outcome was incident ALF. Using medical records, a definite diagnosis of ALF was confirmed if a patient had: 1) no pre-existing liver disease, 2) coagulopathy (international normalized ratio [INR] ≥1.5) without anticoagulation therapy, and either: 3a) hepatic encephalopathy, or 3b) liver transplant due to ALF.10 The ALF date was defined as the first of either the date of hepatic encephalopathy or liver transplant date. A possible diagnosis of ALF was confirmed if a patient met criteria 1 and 2 (above) and had either: 1) altered mentation without a recorded hepatic encephalopathy diagnosis but had hepatic encephalopathy treatment (e.g., lactulose or rifaximin) with no other brain imaging abnormality, or 2) underwent liver transplant due to an unspecified etiology.10 For these patients, the ALF date was the first of either the date of initial encephalopathy treatment or liver transplant date. Patients with evidence of chronic liver disease or portal hypertension on medical record review were not classified as having ALF.

Data Collection

Clinical data

Age, sex, race, ethnicity, body mass index, serum ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, total bilirubin, and platelet count were collected from patients in the KPNC and Penn cohorts at the DILI diagnosis date.

Confirmation of ALF

ALF events were confirmed using a method that we have described.11, 12 In the KPNC cohort, patients were electronically screened for a potential ALF event if they had an inpatient INR ≥1.5 (off warfarin) and peak total bilirubin ≥5.0 mg/dL within 182 days after their DILI diagnosis. The total bilirubin cutoff for identifying potential ALF events was based on the very low likelihood of ALF occurring in the absence of a peak bilirubin level ≥5.0 mg/dL.13, 14 Given the smaller size of the Penn cohort, all of these patients’ records were evaluated for potential ALF.

Hospital records of potential ALF patients (reviewed for all data in Supplementary Table 2) were abstracted onto structured forms. Forms were independently reviewed by two hepatologists, who classified ALF events as: 1) definite, 2) possible, or 3) no event. Disagreement resulted in review by a third hepatologist to adjudicate the event. Determination of implicated drugs, herbals, or dietary supplements was based on consensus opinion by the hepatologists.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). We considered definite or possible ALF events as endpoints. At analysis, we excluded patients who had ALF confirmed on their DILI diagnosis date, since prediction of incident ALF would not be possible.

Within the KPNC cohort, we evaluated the ability of Hy’s Law criteria, present at DILI diagnosis, to identify incident ALF within 6 months from this diagnosis. Hy’s Law criteria were met if ALT or AST was ≥3 times ULN and total bilirubin was ≥2 times ULN at the index date.5, 6 We determined the accuracy of these criteria for ALF and examined the effect of modifying these cut-offs on sensitivity and specificity. We evaluated cut-offs of ALT and AST ranging from ≥50 U/L to ≥400 U/L and of total bilirubin from ≥1.0 mg/dL to ≥5.0 mg/dL.

Since Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score may predict mortality among DILI patients,15 we examined the accuracy of different MELD score cut-offs for incident ALF. Among KPNC patients who had INR measured at DILI diagnosis, MELD score was calculated by: 3.78*ln[total bilirubin (mg/dL)] + 11.2*ln[INR] + 9.57*ln[creatinine (mg/dL)] + 6.43.16

Within the KPNC cohort, we developed prognostic models for ALF comprising laboratory variables measured at DILI diagnosis, including serum ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, total bilirubin, and platelet count. Since abnormal INR is part of the definition of ALF, we did not examine it as a predictor. We created univariable models with each predictor and multivariable models comprising all combinations of predictors. Due to the low incidence of ALF and to ensure that there were at least 10 ALF events for each predictor included within multivariable models (to avoid overfitting17), we only considered models with a maximum of two predictors. The discriminative accuracy of each model was assessed by the concordance statistic (C statistic) with 95% confidence interval (CI).18 The model with the largest C statistic was selected as the final prognostic model. Model calibration was assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic.

The final model was used to compute a risk score, the Drug-Induced Liver Toxicity (DrILTox) ALF Score, for each patient by calculating the estimated logarithmic odds of ALF. For use in clinical care, we identified the score with >90% sensitivity and selected the cut-off with the highest specificity (“high-risk cut-off”). We selected a cut-off with high sensitivity to minimize the potential for missing ALF, an event associated with significant morbidity.8

Since liver aminotransferase levels ≥5 times ULN identify clinically important DILI and might help to exclude acute liver injury unrelated to drugs,9 we re-evaluated the performance of the DrILTox ALF Score high-risk cut-off among KPNC patients with ALT or AST ≥5 times ULN at DILI diagnosis. Further, since the mechanism of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity differs from that of other drugs, we examined the high-risk cut-off’s accuracy after excluding patients who received a prescription for acetaminophen or an acetaminophen-containing drug at DILI diagnosis.

Finally, the Penn cohort was used to externally validate the DrILTox ALF Score. We computed each patient’s DrILTox ALF Score using laboratory data collected from the date that DILI was confirmed by chart review. We determined the classification performance of Hy’s Law criteria and the DrILTox ALF Score high-risk cut-off for incident ALF in this cohort.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the KPNC Cohort

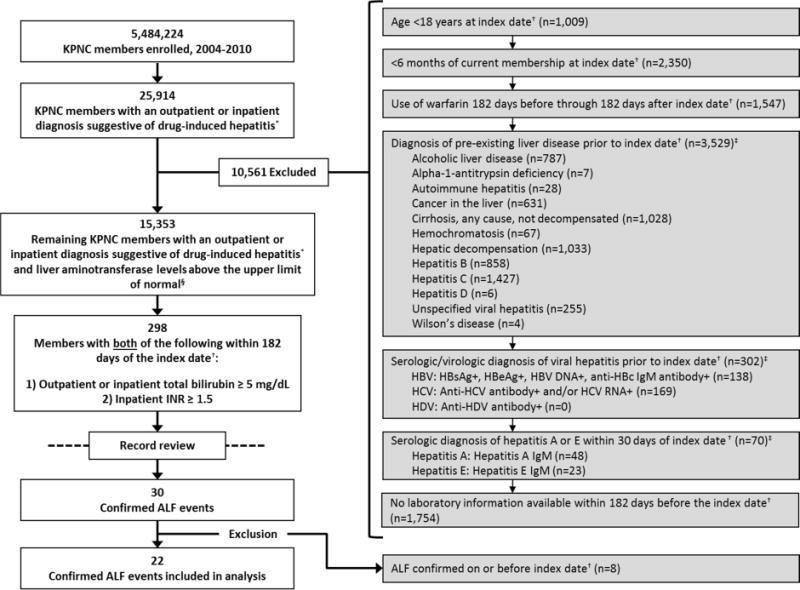

Among 5,484,224 KPNC members enrolled from 2004–2010, 25,914 (0.5%) had an inpatient or outpatient DILI diagnosis. After exclusions (Figure 1), 15,353 KPNC members with a DILI diagnosis, all of whom had AST or ALT levels above ULN, remained. In this cohort, 298 (1.9%) had a hospitalization with an INR ≥1.5 and total bilirubin ≥5.0 mg/dL within 182 days after their index date. After review of these patients’ hospital records, 30 (0.2%) developed ALF (23 definite; 7 possible). Eight (6 definite; 2 possible) were excluded because ALF was confirmed on the index date, leaving 22 (17 definite; 5 possible) ALF events for analysis among 15,345 patients with a DILI diagnosis. The median time to ALF from DILI diagnosis was 15 days (range, 4–25 days).

Fig. 1.

Selection of patients in the study.

Abbreviations: ALF=acute liver failure; HBV=hepatitis B virus; HBsAg=hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg=hepatitis B e antigen; anti-HBc=hepatitis B core antibody; HCV=hepatitis C virus; anti-HCV=hepatitis C virus antibody; HDV=hepatitis D virus; anti-HDV=hepatitis D virus antibody; ICD-9=International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; IgM=immunoglobulin M; INR=international normalized ratio; KPNC=Kaiser Permanente Northern California

*ICD-9 codes 573.3 or 573.8

†Index date = first qualifying date of drug-induced liver injury

‡Patients may have had more than one exclusionary diagnosis recorded

§The upper limits of normal of alanine and aspartate aminotransferase were determined by the assay from which each result was measured.

The characteristics of the 15,345 KPNC patients are presented in Table 1. Patients who developed ALF more commonly had higher ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin levels and lower platelet counts at the time of DILI diagnosis than those who did not develop ALF. Overall, 1,133 (7.4%) patients in the cohort died within 6 months from the index date. Among the 22 ALF patients, 9 (40.9%) underwent liver transplantation, and 5 (22.7%) others died within 6 months from the index date. Peak ALT, AST, and total bilirubin results during follow-up and implicated drugs among the 22 patients who developed ALF are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) and University of Pennsylvania (Penn) patients at DILI diagnosis, overall and by ALF status.

| Characteristic | Kaiser Permanente Northern

California (Derivation Cohort) |

University of

Pennsylvania (External Validation Cohort) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Overall (n=15,345) |

ALF (n=22) |

No ALF (n=15,323) |

P-value | Overall (n=76) |

ALF (n=9) |

No ALF (n=67) |

P-value | |

| Median age (years, IQR) | 56 (44–69) | 47 (33–59) | 56 (44–69) | 0.10 | 45.5 (32–57) | 46.0 (38–62) | 45.0 (29–56) | 0.72 |

|

| ||||||||

| Sex (n, %) | 0.25 | 0.73 | ||||||

| Female | 8,442 (55.0%) | 16 (72.7%) | 8,426 (55.0%) | 31 (40.8%) | 3 (33.3%) | 28 (41.8%) | ||

| Male | 6,899 (45.0%) | 6 (27.3%) | 6,893 (45.0%) | 45 (59.2%) | 6 (66.7%) | 39 (58.2%) | ||

| Unknown | 4 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Race (n, %) | 0.084 | 0.58 | ||||||

| White | 9,766 (63.6%) | 13 (59.1%) | 9,753 (63.6%) | 56 (73.7%) | 7 (77.8%) | 49 (73.1%) | ||

| Asian | 2,397 (15.6%) | 4 (18.2%) | 2,393 (15.6%) | 2 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.0%) | ||

| Black or African American | 1,165 (7.6%) | 5 (22.7%) | 1,160 (7.6%) | 15 (19.7%) | 1 (11.1%) | 14 (20.9%) | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 99 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 99 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 81 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 81 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Unknown | 1,837 (12.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1,837 (12.0%) | 3 (3.9%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (3.0%) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic (n, %) | 2,851 (18.6%) | 2 (9.1%) | 2,849 (18.6%) | 0.25 | 3 (3.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (4.5%) | 0.020 |

|

| ||||||||

| Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 | 5,516 (35.9%) | 8 (36.4%) | 5,508 (35.9%) | 0.88 | 16 (21.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 15 (22.4%) | 0.28 |

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (SD) alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 162 (493) | 1,567 (2,786) | 160 (478) | 0.028 | 1,772 (2,696) | 3,627 (2,873) | 1,523 (2,594) | 0.027 |

| Not tested (n, %) | 1,756 (11.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1,756 (11.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (SD) aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 170 (549) | 2,570 (4,908) | 165 (494) | 0.032 | 2,101 (4,131) | 4,753 (4,362) | 1,745 (4,000) | 0.039 |

| Not tested (n, %) | 4,454 (29.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4,454 (29.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (SD) platelet count (/μL) | 256,000 (96,000) | 200,000 (125,000) | 256,000 (96,000) | 0.041 | 237,000 (91,000) | 176,000 (83,000) | 245,000 (90,000) | 0.033 |

| Not tested (n, %) | 1,836 (12.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1,836 (12.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (SD) alkaline phosphatase (mg/dL) | 147 (170) | 209 (110) | 147 (171) | 0.015 | 311 (386) | 140 (76) | 331 (403) | 0.0012 |

| Not tested (n, %) | 5,025 (32.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5,025 (32.8%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (SD) serum creatinine | 1.0 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.8) | 0.18 | 1.5 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.4) | 0.13 |

| Not tested (n, %) | 1,348 (8.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1,348 (8.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (SD) total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.4 (2.7) | 8.2 (7.4) | 1.4 (2.7) | <0.001 | 7.9 (8.3) | 8.4 (10.4) | 7.8 (8.0) | 0.84 |

| Not tested (n, %) | 5,422 (35.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5,422 (35.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Met Hy’s Law biochemical criteria * , † | 890 (5.8%) | 15 (68.2%) | 875 (5.7%) | <0.001 | 56 (73.7%) | 7 (77.8%) | 49 (73.1%) | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: ALF=acute liver failure; IQR=interquartile range; SD=standard deviation

Biochemical criteria for Hy’s Law were defined as an alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase ≥3 times upper limit of normal and a total bilirubin ≥2 times upper limit of normal on or prior to the date a drug-induced liver injury diagnosis was recorded. Upper limits of normal were determined by the assay from which each result was measured.

Among 11,362 patients in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California cohort tested for total bilirubin and either aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase to determine if biochemical criteria for Hy’s Law were met.

Table 2.

Demographics, liver-related laboratory results, DrILTox ALF Scores,* and determination of whether Hy’s Law criteria were met for 22 KPNC patients with a DILI diagnosis who developed ALF.

| Age (Years) |

Sex | Laboratory Results At DILI Diagnosis |

Peak† Laboratory

Results During Follow-up |

Liver Transplant |

Implicated Drug(s) | DrILTox ALF Score* |

Hy’s

Law Biochemical Criteria Met§ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST (U/L) |

ALT (U/L) |

Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) |

Platelet Count† (/109/L) |

AST (U/L) |

ALT (U/L) |

Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) |

Platelet Count† (/109/L) |

Score | Risk‡ | |||||

| 79 | Female | 1,273 | 1,340 | 25.2 | 149 | 1,273 | 1,340 | 25.2 | 97 | No | Nitrofurantoin | 3.74285 | High | Yes |

| 31 | Female | 3,977 | 1,781 | 25.0 | 239 | 6,340 | 2,308 | 25.0 | 188 | Yes | Acetaminophen-propoxyphene, erythromycin | 3.12069 | High | Yes |

| 45 | Female | 1,094 | 932 | 14.6 | 105 | 1,094 | 932 | 16.9 | 62 | No | Imatinib | 2.06150 | High | Yes |

| 84 | Male | 67 | 27 | 20.8 | 389 | 156 | 124 | 24.2 | 196 | No | Herbal (saw palmetto), acetaminophen | 1.28191 | High | No |

| 41 | Female | 2,309 | 559 | 12.8 | 180 | 2,309 | 559 | 14.2 | 127 | Yes | Nevirapine, zidovudine, lamivudine, acetaminophen | 1.19939 | High | Yes |

| 76 | Male | 25 | 173 | 8.0 | 97 | 2,910 | 1,628 | 8.0 | 55 | No | Acetaminophen | 0.85677 | High | No |

| 58 | Female | 2,659 | 1,714 | 9.5 | 184 | 3,700 | 1,714 | 25.0 | 59 | Yes | Leflunamide, herbals (IsoCort, Zhi-bai), lovastatin, pantoprazole, acetaminophen | 0.54172 | High | Yes |

| 33 | Male | 330 | 771 | 8.6 | 174 | 1,204 | 771 | 16.1 | 3 | No | ** | 0.43902 | High | Yes |

| 28 | Male | 185 | 142 | 4.3 | 61 | 185 | 144 | 25.0 | 6 | No | Cisplatin, herbals | 0.39925 | High | Yes |

| 23 | Female | 12,675 | 3,000 | 5.4 | 116 | 12,675 | 9,310 | 7.2 | 97 | No | Acetaminophen | 0.22904 | High | Yes |

| 36 | Female | 2,359 | 3,498 | 6.9 | 172 | 2,359 | 3,498 | 25.0 | 144 | Yes | Ketoconazole | 0.12829 | High | Yes |

| 47 | Female | 2,579 | 1,840 | 6.2 | 162 | 5,891 | 2,670 | 11.6 | 12 | No | ** | 0.06378 | High | Yes |

| 47 | Female | 39 | 12 | 1.8 | 53 | 1,356 | 523 | 25.0 | 9 | Yes | Amoxicillin-clavulanate | −0.02274 | High | No |

| 51 | Male | 4,227 | 3,214 | 8.6 | 249 | 4,227 | 3,214 | 21.9 | 246 | Yes | ** | −0.07945 | High | Yes |

| 39 | Female | 278 | 218 | 9.0 | 268 | 278 | 218 | 24.8 | 223 | No | ** | −0.13443 | High | Yes |

| 70 | Male | 39 | 49 | 0.2 | 35 | 115 | 192 | 7.8 | 6 | No | Cytarabine, idarubicin, acetaminophen | −0.20377 | High | No |

| 59 | Female | 365 | 400 | 5.5 | 259 | 386 | 544 | 19.1 | 63 | Yes | ** | −0.74041 | High | Yes |

| 31 | Female | 20,698 | 13,049 | 3.6 | 210 | 20,698 | 13,049 | 9.3 | 115 | No | Acetaminophen | −0.76442 | High | Yes |

| 56 | Female | 235 | 187 | 0.9 | 140 | 689 | 250 | 9.5 | 48 | No | Acetaminophen | −0.79599 | High | No |

| 72 | Female | 324 | 190 | 2.7 | 231 | 5,533 | 3,778 | 17.0 | 147 | No | Ibuprofen, orlistat | −1.08141 | High | Yes |

| 29 | Female | 746 | 1,334 | 1.0 | 323 | 1,016 | 1,334 | 10.3 | 214 | Yes | ** | −2.04196 | Low | No |

| 51 | Female | 65 | 43 | 0.3 | 597 | 15,750 | 5,262 | 7.5 | 110 | No | Acetaminophen | −4.06974 | Low | No |

Abbreviations: ALT=alanine aminotransferase; AST=aspartate aminotransferase; DILI=drug-induced liver injury; DrILTox=Drug-Induced Liver Toxicity; ALF=acute liver failure

DrILTox ALF Score = −0.00691292 * platelet count (per 109/L) + 0.19091500 * total bilirubin (per 1.0 mg/dL)

For platelet count, the lowest result during follow-up is presented.

Risk score greater than −1.08141 indicated high risk of acute liver failure based on DrILTox ALF Score.

Biochemical criteria for Hy’s Law were defined as an alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase ≥3 times upper limit of normal and a total bilirubin ≥2 times upper limit of normal on the date a drug-induced liver injury diagnosis was recorded. Upper limits of normal were determined by the assay from which each result was measured.

Offending drug could not be determined among the list of drugs provided.

Accuracy of Hy’s Law Criteria and MELD Score for Incident ALF

At diagnosis of DILI, Hy’s Law criteria had high specificity (0.92; 95% CI, 0.91–0.93) and negative predictive value (0.99; 95% CI, 0.99–1.0), but low sensitivity (0.68; 95% CI, 0.45–0.86) and positive predictive value (0.02; 95% CI, 0.01–0.03), for ALF. Supplementary Table 3 presents the sensitivities and specificities of different cut-offs of total bilirubin, ALT, and AST for ALF. Total bilirubin ≥1.0 mg/dL and ALT or AST ≥50 U/L provided the highest sensitivity (0.77) for ALF.

Supplementary Table 4 reports the performance characteristics of various MELD score cutoffs. A MELD Score ≥10 had the highest sensitivity (0.84; 95% CI, 0.60–0.97) for ALF.

Development of a New Prognostic Model for ALF: DrILTox ALF Score

Table 3 reports the discriminative ability of prognostic models comprised of one laboratory predictor and all combinations of two predictors. Models with AST, ALT, and total bilirubin alone had high discriminative ability (C statistic range, 0.83–0.85), but each had poor calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test p<0.001). The model that had the highest discrimination (C statistic, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.76–0.96) included platelet count and total bilirubin (DrILTox ALF Score =−0.00691292*platelet count [per 109/L] + 0.19091500*total bilirubin [per 1.0 mg/dL]), indicating that decreasing platelet count and increasing total bilirubin were strong predictors of incident ALF. This model closely predicted the actual observed numbers of patients with and without ALF (Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test p=0.29). The DrILTox ALF Scores at DILI diagnosis and risk stratification for the 22 KPNC patients who developed ALF are included in Table 2.

Table 3.

C statistics for prognostic models for ALF among KPNC patients with a DILI diagnosis.

| No. Predictor s in Prognostic Model | Predictors in Prognostic Model | C statistic (95% CI) | No. With ALF in Prognostic Model | No. Without ALF in Prognostic Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total bilirubin | 0.85 (0.74–0.95) | 22 | 9,901 |

| 1 | Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 0.85 (0.76–0.93) | 22 | 10,869 |

| 1 | Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 0.83 (0.72–0.93) | 22 | 13,567 |

| 1 | Alkaline phosphatase | 0.77 (0.71–0.84) | 22 | 10,298 |

| 1 | Platelet count | 0.69 (0.55–0.82) | 22 | 13,487 |

| 1 | Serum creatinine | 0.62 (0.45–0.73) | 22 | 13,975 |

| 2 | Platelet count, total bilirubin | 0.87 (0.76–0.96) | 22 | 9,391 |

| 2 | AST, total bilirubin | 0.86 (0.76–0.96) | 22 | 8,990 |

| 2 | ALT, total bilirubin | 0.86 (0.75–0.96) | 22 | 9,675 |

| 2 | Serum creatinine, total bilirubin | 0.85 (0.74–0.95) | 22 | 9,339 |

| 2 | Alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin | 0.85 (0.72–0.94) | 22 | 9,434 |

| 2 | ALT, AST | 0.84 (0.74–0.93) | 22 | 10,486 |

| 2 | Alkaline phosphatase, AST | 0.84 (0.76–0.91) | 22 | 9,220 |

| 2 | ALT, serum creatinine | 0.84 (0.72–0.93) | 22 | 12,488 |

| 2 | Alkaline phosphatase, ALT | 0.83 (0.75–0.90) | 22 | 10,057 |

| 2 | AST, serum creatinine | 0.80 (0.68–0.92) | 22 | 10,126 |

| 2 | AST, platelet count | 0.79 (0.71–0.91) | 22 | 9,985 |

| 2 | ALT, platelet count | 0.78 (0.70–0.89) | 22 | 12,017 |

| 2 | Alkaline phosphatase, serum creatinine | 0.74 (0.63–0.82) | 22 | 9,683 |

| 2 | Alkaline phosphatase, platelet count | 0.72 (0.63–0.83) | 22 | 9,727 |

| 2 | Serum creatinine, platelet count | 0.70 (0.58–0.82) | 22 | 12,745 |

Abbreviations: ALF=acute liver failure; ALT=alanine aminotransferase; AST=aspartate aminotransferase; CI=confidence interval

Within the KPNC cohort, the DrILTox ALF Score high-risk cut-off of −1.08141 had a sensitivity of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.71–0.99), specificity of 0.76 (95% CI, 0.75–0.77), negative predictive value of 0.99 (95% CI, 0.99–1.0), and positive predictive value of 0.01 (95% CI, 0.005–0.01) for incident ALF (Table 4). The classification performance for this cut-off remained unchanged when the cohort was restricted to patients with liver aminotransferase levels ≥5 times ULN at DILI diagnosis (Supplementary Table 5). The accuracy of the cut-off was also similar after exclusion of patients who received acetaminophen or an acetaminophen-containing drug (Supplementary Table 6).

Table 4.

Classification performance of the high-risk cut-off (score = −1.08141) of the DrILTox ALF Score* among KPNC patients who had platelet count and total bilirubin measured at DILI diagnosis.

| Prognostic Model | Acute Liver Failure | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | |

| High risk | 20 | 2,363 | 2,383 |

| Low risk | 2 | 7,487 | 7,489 |

|

| |||

| Total | 22 | 9,850 | 9,872 |

DrILTox ALF Score = −0.00691292 * platelet count [per 109/L] + 0.19091500 * total bilirubin [per 1.0 mg/dL] Sensitivity, 0.91 (95% CI, 0.71 – 0.99)

Specificity, 0.76 (95% CI, 0.75 – 0.77)

Positive predictive value, 0.01 (95% CI, 0.005 – 0.01)

Negative predictive value, 0.99 (95% CI, 0.99 – 1.0)

External Validation of the DrILTox ALF Score

Seventy-six Penn patients met criteria for DILI from 2008–2014 based on record review. Their characteristics are shown in Table 1. The most commonly implicated drugs/classes were acetaminophen (21 [27.6%]), anti-bacterial agents (30 [39.5%]), and herbal/dietary supplements (12 [15.8%]). Among these 76 patients, 9 (11.8%) developed ALF (9 definite; 0 possible). Peak ALT, AST, and total bilirubin results and implicated drugs among these 9 patients are presented in Supplementary Table 7. Within this validation cohort, Hy’s Law criteria had high negative predictive value (0.90; 95% CI, 0.68–0.99), moderate sensitivity (0.78; 95% CI, 0.40–0.97), and low specificity (0.27; 95% CI, 0.17–0.39) and positive predictive value (0.13; 95% CI, 0.05–0.24) for ALF. The DrILTox ALF Score high-risk cut-off of −1.08141 maintained high sensitivity (0.89; 95% CI, 0.52–1.00) for ALF (Table 5).

Table 5.

Classification performance of the high-risk cut-off (score = −1.08141) of the DrILTox ALF Score* within the Penn cohort.

| Prognostic Model | Acute Liver Failure | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | |

| High risk | 8 | 46 | 54 |

| Low risk | 1 | 21 | 22 |

|

| |||

| Total | 9 | 67 | 76 |

DrILTox ALF Score = −0.00691292 * platelet count [per 109/L] + 0.19091500 * total bilirubin [per 1.0 mg/dL]

Sensitivity, 0.89 (95% CI, 0.52 – 1.00)

Specificity, 0.31 (95% CI, 0.21 – 0.44)

Positive predictive value, 0.15 (95% CI, 0.07 – 0.27)

Negative predictive value, 0.95 (95% CI, 0.77 – 1.00)

C statistic, 0.60 (95% CI 0.47 – 0.72)

DISCUSSION

In this study, the presence of Hy’s Law biochemical criteria at the time of DILI diagnosis had high specificity (0.92) and negative predictive value (0.99), but low sensitivity (0.68) and positive predictive value (0.02), for incident ALF. Modifying the cut-offs of these criteria resulted in only a modest increase in sensitivity (0.77). The DrILTox ALF Score, comprising platelet count and total bilirubin, had high discriminative ability for ALF (C statistic, 0.87). At a cut-off of −1.08141, the DrILTox ALF Score had substantially higher sensitivity for ALF (0.91) than Hy’s Law criteria (0.68) or MELD score ≥10 (0.84), while maintaining reasonable specificity. The DrILTox ALF Score cutoff of −1.08141 retained high sensitivity during external validation, which supports its potential application for risk stratification of ALF among patients with suspected DILI in clinical practice.

Hy’s Law has been the most commonly used method to identify severe hepatotoxicity signals in clinical trials.4–6 However, our analyses indicate that in clinical practice it is unable to accurately identify DILI patients at high risk of ALF. A recent analysis of 771 DILI patients in the Spanish DILI registry found that an algorithm based on AST >17.3 times ULN, total bilirubin >6.6 times ULN, and AST:ALT ratio >1.5 identified ALF patients with 80% sensitivity and 82% specificity.14

The DrILTox ALF Score provides an increased ability to identify patients with suspected DILI who are at high risk of ALF. The score is relatively easy to compute and could be utilized by providers in clinical practice. For example, if a patient with suspected DILI presented with a platelet count of 145,000 and total bilirubin of 3.0 mg/dL, the DrILTox ALF Score would be calculated using the equation: −0.00691292*platelet count [per 109/L] + 0.19091500*total bilirubin [per 1.0 mg/dL] = −0.00691292*145 + 0.19091500*3.0 = −0.4296284. This score is above the cut-off of −1.08141, indicating an increased risk of ALF.

The DrILTox ALF Score was developed to have high sensitivity so that very few DILI patients who develop ALF would be missed. The specificity of the high-risk cut-off declined in external validation (0.76 to 0.30), likely because this cohort was comprised of patients with more severe DILI. Hy’s Law specificity also decreased in external validation (0.92 to 0.27). The positive predictive value of this cut-off was low, which is not surprising given the low incidence rate of drug-induced ALF (1.61 [95% CI, 1.06–2.35] events per 1,000,000 person-years).11 However, in both the derivation and external validation cohorts, the incidence of ALF in the high-risk group identified by the DrILTox ALF Score was substantially higher compared to the incidence of drug-induced ALF in the general population11 and in persons categorized as low-risk. Strategies to manage complications of DILI could be directed toward these high-risk patients. Such patients could undergo more intensive monitoring of liver-related laboratory tests to detect evolving hepatic dysfunction earlier in the course of DILI, which might improve prognosis. Likewise, patients with high-risk scores could be referred to hepatology specialty care earlier, which might improve outcomes. High-risk patients might also be considered for earlier transfer to a liver transplant center and for treatment with N-acetylcysteine, which improves outcomes in acetaminophen- and non-acetaminophen-induced liver injury.19, 20

Platelet count and total bilirubin are both credible as predictors of ALF. Platelet count can be affected by ALF-induced inflammation and hepatic function. Within the US Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network, patients with lower platelet counts at DILI onset were more likely to experience a liver-related death or undergo liver transplantation.21 Total bilirubin reflects whole-liver functional capacity, and increasing total bilirubin can be a marker of hepatic dysfunction.

This study has several potential limitations. First, the KPNC cohort was comprised of patients with clinician-recorded diagnoses of DILI, liver aminotransferase levels above ULN, and no other etiologies of acute liver injury. It is possible that we might have included patients who did not actually have DILI. However, in clinical practice, patients considered to have DILI by their treating clinician with no other identifiable causes of liver injury are exactly the desired target population for applying the DrILTox ALF Score. Further, the cumulative incidence of DILI in the KPNC cohort exceeded that of prior studies from outpatient clinic settings, which have reported incidences of DILI ranging from 2.3–19.1 cases per 100,000 persons.22, 23 The higher incidence of DILI in this cohort may have been due to the inclusion of patients who had diagnoses recorded in the hospital as well as in outpatient settings, our use of liver aminotransferase thresholds that were lower than those used in other studies, and the possible inclusion of patients who did not have DILI. Despite these limitations, the DrILTox ALF Score retained high sensitivity in external validation. Second, there is the potential that we might have missed KPNC patients with ALF who never developed a total bilirubin ≥5.0 mg/dL, but the likelihood of ALF occurring in the presence of a bilirubin <5.0 mg/dL is low.13, 14 Third, the derivation of our model was limited by the number of incident ALF events. Nonetheless, using only two predictors, the DrILTox ALF Score has high discriminative ability. Finally, the relatively small size of our external validation cohort resulted in wide confidence intervals for all performance characteristics.

In summary, Hy’s Law criteria at DILI diagnosis had high specificity and negative predictive value, but low sensitivity and positive predictive value, for incident ALF. A new prognostic model with platelet count and total bilirubin identified patients with DILI who are at increased risk of ALF with high sensitivity. This model is based on simple laboratory variables and demonstrated superior sensitivity to the most commonly used existing tool (Hy’s Law). Future studies should determine if use of the DrILTox ALF Score improves outcomes among patients with DILI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grant funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01 HS018372) and the National Institutes of Health (K24 DK078228)

Funding: This study was supported by research grant funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01 HS018372) and the National Institutes of Health (K24 DK078228).

List of Abbreviations in alphabetical order

- ALF

acute liver failure

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CI

confidence interval

- DILI

drug-induced liver injury

- DrILTox

drug-induced liver toxicity

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- IgM

immunoglobulin M

- INR

international normalized ratio

- KPNC

Kaiser Permanente Northern California

- ULN

upper limit of normal

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: V.L.R. obtained funding and provided study oversight. V.L.R, K.H., J.D.L, K.R.R, J.R., B.L.S, K.B.F.L, D.M.C, and D.A.C. were involved in the study concept and design. A.R.M., J.D.B., J.L.S, K.A.F, D.G., and D.M.C. were involved in the acquisition of data. V.L.R, K.H., D.M.C, D.S., J.R., and J.D.L analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors provided critical revision of the manuscript.

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Friis H, Andreasen PB. Drug-induced hepatic injury: an analysis of 1100 cases reported to the Danish Committee on Adverse Drug Reactions between 1978 and 1987. J Intern Med. 1992;232:133–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1924–34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.011. 1934 e1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplowitz N. Drug-induced liver disorders: implications for drug development and regulation. Drug Saf. 2001;24:483–90. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: The Adverse Effects of Drugs and Other Chemicals on the Liver. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reuben A. Hy’s law. Hepatology. 2004;39:574–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.20081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temple R. Hy’s law: predicting serious hepatotoxicity. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:241–3. doi: 10.1002/pds.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman G, Habel L, Boles M, et al. Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program: Division of Research, Northern California, and Center for Health Research, Northwest Division. In: Strom BL, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 3rd. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2000. pp. 263–283. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontana RJ. Acute liver failure due to drugs. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:175–87. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1073117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aithal GP, Watkins PB, Andrade RJ, et al. Case definition and phenotype standardization in drug-induced liver injury. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:806–15. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polson J, Lee WM. AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2005;41:1179–97. doi: 10.1002/hep.20703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg DS, Forde KA, Carbonari DM, et al. Population-representative incidence of drug-induced acute liver failure based on an analysis of an integrated healthcare system. Gastroenterology. 2015 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.050. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo Re V, 3rd, Carbonari DM, Forde KA, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes and laboratory tests of liver dysfunction to identify acute liver failure events. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pds.3774. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a U.S. multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2010;52:2065–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.23937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robles-Diaz M, Lucena MI, Kaplowitz N, et al. Use of Hy’s law and a new composite algorithm to predict acute liver failure in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:109–118. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.050. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong R, Lee YS, Sohn C, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease score as a predictor of short-term outcome in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:439–46. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.958094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464–70. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15:361–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee WM, Hynan LS, Rossaro L, et al. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine improves transplant-free survival in early stage non-acetaminophen acute liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:856–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.006. , 864 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bateman DN, Dear JW, Thanacoody HK, et al. Reduction of adverse effects from intravenous acetylcysteine treatment for paracetamol poisoning: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:697–704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fontana RJ, Hayashi PH, Gu J, et al. Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality within 6 months from onset. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:96–108. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.045. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sgro C, Clinard F, Ouazir K, et al. Incidence of drug-induced hepatic injuries: a French population-based study. Hepatology. 2002;36:451–5. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjornsson ES, Bergmann OM, Bjornsson HK, et al. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419–25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.006. 1425 e1–3; quiz e19–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.