Abstract

Estrogens act upon estrogen receptor (ER)α to inhibit feeding and improve glucose homeostasis in female animals. However, the intracellular signals that mediate these estrogenic actions remain unknown. Here, we report that anorexigenic effects of estrogens are blunted in female mice that lack ERα specifically in proopiomelanocortin (POMC) progenitor neurons. These mutant mice also develop insulin resistance and are insensitive to the glucose-regulatory effects of estrogens. Moreover, we showed that propyl pyrazole triol (an ERα agonist) stimulates the phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway specifically in POMC progenitor neurons, and that blockade of PI3K attenuates propyl pyrazole triol-induced activation of POMC neurons. Finally, we show that effects of estrogens to inhibit food intake and to improve insulin sensitivity are significantly attenuated in female mice with PI3K genetically inhibited in POMC progenitor neurons. Together, our results indicate that an ERα-PI3K cascade in POMC progenitor neurons mediates estrogenic actions to suppress food intake and improve insulin sensitivity.

Estrogens play critical roles in the regulation of body weight balance. For example, depletion of endogenous estrogens in female rodents, via ovariectomy (OVX), leads to increased body weight and hyperadiposity (1, 2). Estrogen replacement therapy can prevent obesity in OVX female animals (1). The body weight-lowering effects of estrogens are attributed both to decreased food intake and increased energy expenditure (3). The estrogenic regulation of energy balance is primarily mediated by estrogen receptor (ER)α, because the deletion of ERα, but not ERβ, leads to increased body weight and adiposity in mice (4–6). Recently, we have demonstrated that deletion of ERα from proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARH) leads to hyperphagia in female mice (7), suggesting that estrogenic actions on food intake are mediated by ERα expressed by ARH POMC progenitor neurons. However, the intracellular mechanisms in POMC progenitor neurons that mediate estrogen/ERα effects on feeding remain unclear.

Notably, estrogen-ERα signals also produce antidiabetic effects. For example, OVX female animals show impaired insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis, and these deleterious metabolic effects can be reversed by chronic estrogen replacement (8, 9). Interestingly, both humans and mice bearing loss-of-function mutations in the ERα gene develop insulin resistance and glucose intolerance (6, 10). Further, ERα knockout mice display impaired insulin sensitivity in the liver revealed by the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp (5). The antidiabetic effects of estrogens are abolished in ERα knockout mice (1). Together, these findings indicate that estrogens, via acting upon ERα, play an essential role in maintaining normal glucose homeostasis. However, the critical ERα populations and the intracellular mechanisms that mediate the antidiabetic effects of estrogens remain to be identified.

Emerging evidence suggests that the phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway may mediate effects of estrogen-ERα signals to regulate energy and glucose homeostasis. In particular, estrogen replacement increases expression of p55γ (a regulatory subunit of PI3K) in the hypothalamus of female guinea pigs (11). In addition, PI3K blockers can inhibit effects of estrogens to stimulate hypothalamic POMC neurons (11). Further, we have previously shown that both male and female mice with PI3K genetically inhibited in POMC progenitor neurons are more sensitive to obesity when challenged by high fat-diet feeding (12). Importantly, mice with inhibited PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons develop whole-body insulin resistance, and insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt in the liver is severely suppressed in mutants (12). Together, these observations led us to hypothesize that the ERα-PI3K cascade in POMC progenitor neurons mediates estrogenic effects on female body weight balance and glucose homeostasis.

To test this hypothesis, we first investigated whether ERα in POMC progenitor neurons is functionally coupled to the PI3K pathway. In addition, we used 2 mutant mouse models: one lacking ERα in POMC progenitor neurons and another with genetic inhibition of PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons. We systemically characterized effects of estrogens on food intake, body weight and insulin sensitivity in these models, and determined whether the ERα-PI3K cascade in POMC progenitor neurons is required to mediate effects of estrogens to suppress feeding and to improve glucose homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Several mouse models were used for various studies. First, POMC-Cre transgene (13) was bred onto Esr1f/f mice (14) to generate Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre and Esr1f/f littermates. Similarly, POMC-Cre transgene was bred onto Pik3caf/f mice (15) to generate Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre and Pik3caf/f littermates. These mice were used for feeding and glucose studies as outlined below. In a subset of breeding for Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre line, the Rosa26-FoxO1GFP reporter allele (16) was introduced to produce Pik3ca+/+/POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP littermates, and these mice were used for hypothalamic organotypic slice cultures and in vitro FoxO1GFP assays. We also bred POMC-Cre mice with Rosa26-FoxO1GFP reporter mice to generate POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mice, and these mice were used for intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injections and in vivo FoxO1GFP assays. POMC-EGFP transgenic mice (17) were generated by breeding POMC-EGFP mice with C57Bl/6 mice, and these mice were used for electrophysiological recordings. Most of these mouse strains were backcrossed onto C57Bl/6 background for more than 12 generations. Pik3caf/f mice were kept on a mixed C57Bl/6;129S6/SvEv background. We also purchased C57Bl/6 mice from the animal facility of Baylor College of Medicine.

Mice were weaned on chow diet (6.5% fat, 2920; Harlan) at 3–4 weeks of age. All mice were housed in a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle. Care of all animals and procedures were conformed to the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Unite States National Institutes of Health and were approved by the Animal Subjects Committee of Baylor College of Medicine.

Validation of genomic deletion of Esr1 and Pik3ca alleles in POMC cells

Female Esr1f/f, Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre, Pik3caf/f, and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane, and killed. Various tissues, including the hypothalamus, pituitary, cortex, brain stem, liver, adrenal gland, ovary, and muscle were collected. Genomic DNAs were extracted using the REDExtract-N-Amp Tissue PCR kit (XNATS; Sigma-Aldrich), followed by PCR amplification of the floxed or recombined alleles. For both Esr1 floxed and recombined alleles, we use primers: forward, CCTTCCACGAAGGTTTTGAAG and reverse, TGGAGTTGCTCAAAGCTGTCT. The floxed Esr1 allele was recognized as a 1089-bp band, and the recombined Esr1 allele was recognized as a 560-bp band. We use primers: forward, CTGTGTAGCCTAGTTTAGAGCAACCATCTA and reverse, CCTCTCTGAACAGTTCATGTT TGATGGTGA, to detect the floxed Pik3ca allele (530 bp); we used primers: forward, TCATTCTTCCCATTGCTTG and reverse, GACCGCCTCCTTACCTTTATC, to detect the recombined Pik3ca allele (947 bp).

Effects of sc 17β-estradiol

In order to examine the chronic anorexigenic effects of estrogens, 12-week-old female mice with various genotypes (Esr1f/f, Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre, Pik3caf/f, and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre) were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane. As previously described (7, 18), bilateral OVX was performed, followed by sc implantations of pellets containing 17β-estradiol (0.5 μg/d for 90 d, OVX+17β estradiol [E]) or empty pellets (OVX+vehicle [V]). These pellets were purchased from Innovative Research of America. After recovery from the surgery (7 d), daily body weight and food intake were monitored. Body composition (fat mass and lean mass) was measured by quantitative magnetic resonance before and 4–5 weeks after the surgeries.

On the day before and 4–5 weeks after the surgeries, mice were shortly fasted for 2 hours (from 8 to 10 am) to empty the stomach. Glucose levels were measured in tail blood using a One-Touch glucometer. In addition, tail blood was collected and processed to measure serum leptin, insulin, and corticosterone, using the mouse leptin ELISA kit (90030; Crystal Chem), the mouse insulin ELISA kit (90080; Crystal Chem), and the corticosterone ELISA kit (ADI-900-097; Enzo Life Sciences), respectively.

Glucose tolerance tests were performed 4–5 weeks after the surgeries, as we did before (7, 12). Briefly, mice were fasted overnight. On the next morning, mice received ip injections of 2-mg/kg glucose at 10 am. Glucose levels were measured in tail blood using a One-Touch glucometer before glucose injection (time 0) and at multiple time points afterwards (as indicated in the figures).

Euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp

Euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp studies were performed in unrestrained mice using regular human insulin (doses, 2.5 mU/kg·min body weight; Humulin R) in combination with high pressure liquid chromatography purified [3-3H]glucose as described previously (19, 20). In brief, a microcatheter was inserted into the jugular vein by survival surgery and waited for 4–5 days for complete recovery. Studies were then performed in conscious mice. Overnight-fasted conscious mice received a priming dose of HPLC-purified [3-3H] glucose (10 μCi) and then a constant infusion (0.1 μCi/min) of label glucose for approximately 2.5–3.0 hours. Blood samples were collected from the tail vein at 0, 50, and 60 minutes to measure the basal glucose production rate. After approximately 1 hour of infusion, mice were primed with regular insulin (bolus 10 mU/kg body weight) followed by an approximately 2-hour constant insulin infusion (2.5 mU/kg·min). Using a separate pump, 25% glucose were used to maintain the blood glucose level at 100–140 mg/dL, as determined every 6–9 minutes using a glucometer (LifeScan). Endogenous glucose appearance rate (EndoRa) under the basal condition and clamped condition, peripheral glucose disposal rates (Rds), and glucose infusion rate (GIR) were then measured from collected plasma.

Food intake across the estrous cycles

Gonad-intact female Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre and Pik3caf/f littermates (12 wk of age) were singly housed and fed with chow. Vaginal smear was performed daily to determine estrous state based on microscopic cytology. Daily food intake was measured for at least 3 consecutive complete estrous cycles, and averaged food intake at each estrous stage was calculated for each mouse. Note that the same experiments were not feasible in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice, because these mutant mice have irregular estrous cycles (7).

Hypothalamic ERα-p85α interaction and phosphorylation of AKT in response to i.c.v. propyl pyrazole triol (PPT)

Female C57Bl6 mice (12 wk) were anesthetized with ip injections of ketamine/xylazine cocktail (100-mg/kg ketamine and 10-mg/kg xylazine). Bilateral OVX was performed as reported before (7, 18). Under the same anesthesia, an indwelling i.c.v. guide cannula (C315; Plastics One) was stereotaxically inserted to target the lateral ventricle (0.34 mm caudal and 1 mm lateral from bregma; depth, 2.3 mm). Precise position of the i.c.v. cannulation was confirmed by demonstration of increased thirst in response to administration of angiotensin II (10 ng, 3–4 d after surgeries), as we did before (21). After a 7-day recovery from the surgery, mice were fasted overnight. On next morning (9 am), mice received i.c.v. injections of PPT (500 pmol in 1 μL) or vehicle (saline solution with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide). Thirty minutes after i.c.v. injections, mice were deeply anesthetized with inhaled isofluorane and immediately killed. Hypothalami were quickly isolated. Hypothalamic samples (900 μg) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-ERα antibody (C1355, 1:500; Millipore). Immunoprecipitates were then subjected to immunoblotting with mouse anti-ERα (1:1000; Labvision) or rabbit anti-p85α (1:2000; Cell Signaling). Total lysates (20 μg) were used as input and immunoblotted with anti-ERα and anti-p85α. To test the effects of PPT on the regulation of AKT, hypothalamic samples (20 μg) were immunoblotted with antiphospho-Akt (Thr308) rabbit mAb (1:1000; 244F9; Cell Signaling Technology) or Akt rabbit monoclonal antibody (mAb) (1:1000, 9272; Cell Signaling Technology). The levels of β-actin (mouse mAb at 1:10 000, A1978; Sigma) served as the loading control (for antibodies, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibody Table

| Peptide/Protein Target | Antigen Sequence (if Known) | Name of Antibody | Manufacturer, Catalog Number, and/or Name of Individual Providing the Antibody | Species Raised in; Monoclonal or Polyclonal | Dilution Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERα | Rabbit anti-ERα antibody | Millipore, C1355 | Rabbit | 1:500 for IP, 1:10 000 for double IF | |

| ERα | Mouse anti- ERα | Labvision | Mouse | 1:1000 for WB | |

| p85α | Rabbit anti-p85α | Cell Signaling | Rabbit | 1:2000 for WB | |

| Akt | Antiphospho-Akt (Thr308) | Cell Signaling, 244F9 | Rabbit; monoclonal | 1:1000 for WB | |

| Akt | Akt rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling, 9272 | Rabbit; monoclonal | 1:1000 for WB | |

| β-Actin | Anti-β-actin | Sigma, A1978 | Mouse; monoclonal | 1:10 000 for WB | |

| GFP | Chicken anti-GFP antibody | Aves Labs, GFP-1020 | Chicken | 1:250 for double IF | |

| GFP | Rabbit anti-GFP antibody | Invitrogen, A6455 | Rabbit | 1:20 000 for single IF |

FoxO1GFP translocation in POMC progenitor neurons in response to i.c.v. PPT

Female POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mice (12 wk) were anesthetized with ip injections of ketamine/xylazine cocktail (100-mg/kg ketamine and 10-mg/kg xylazine). Bilateral OVX and i.c.v. cannulation were performed as described above. Precise position of the i.c.v. cannulation was confirmed by demonstration of increased thirst in response to administration of angiotensin II (10 ng, 3–4 d after surgeries). After a 7-day recovery from the surgery, mice were fasted overnight. On next morning (9 am), mice received i.c.v. injections of PPT (500 pmol in 1 μL) or vehicle (1 μL). Thirty minutes after i.c.v. injections, mice were deeply anesthetized with inhaled isofluorane and perfused with saline followed by 10% formalin. Brain sections (25 μm in thickness) were collected and then subjected to dual immunofluorescence for ERα and green fluorescent protein (GFP). Briefly, brain sections were incubated with rabbit anti-ERα antibody (1:10 000 dilution; EMD Millipore) followed by biotinylated goat antirabbit IgG (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch). The complex was visualized using avidin-biotin conjugated to DyLight 594 (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch). After thorough washing, the sections were then incubated with chicken anti-GFP antibody (1:5000; Aves Labs, Inc) for 7 days at 4°C, followed by incubation in goat antichicken IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (1:250; Invitrogen) for 1.5 hours. Sections were mounted on slides and cover slipped with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) mounting medium. Fluorescence images were taken using the Leica 5500 fluorescence microscope with OptiGrid structured illumination (for antibodies, see Table 1).

Nuclear/cytoplasmic localization of GFP (forkhead box O1, FoxO1) was quantified using the published protocol (16). Briefly, fluorescence intensity was measured from the entire neuron and the nucleus (defined by DAPI staining) using MetaMorph 1.5 software. After correction for background fluorescence, a ratio between nuclear fluorescence intensity and total cell fluorescence intensity was calculated (nuclear to total [N/T] ratio) for each cell. This N/T ratio was determined from about 200 ERα(+) neurons and 200 ERα(−) neurons from each mouse. Percentage of cells was plotted against various N/T ranges. These experiments were repeated in 3 mice per group.

Hypothalamic organotypic slice cultures and FoxO1GFP translocation

The hypothalamic organotypic slices were made essentially as described before (16, 22). Briefly, Pik3ca+/+/POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mice (8–13 d of age, males and females) were decapitated, and the brains were quickly removed. Hypothalamic tissues were sectioned in depth of 250 μm on a vibratome (VT1000 S; Leica) in chilled Gey's Balanced Salt Solution (Sigma) enriched with glucose (0.5%) and KCl (30mM). The coronal slices containing the ARH were then placed on Millicell-CM filters (PICM03050; Millipore), and then maintained at an air-media interface in MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with heat-inactivated horse serum (25%; Invitrogen), glucose (32mM), and GlutaMAX (2mM; Invitrogen). Cultures were typically maintained for 10 days and were fixed with 4% formalin in PBS at 4°C overnight. After a series of PBS washes, the tissues were incubated overnight at room temperature in a rabbit anti-GFP primary antiserum (1:20 000; Invitrogen) in phosphate-buffered saline Tween 20-azide 3% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS. After washing in PBS, the tissues were incubated in Alexa Fluor 488 antirabbit IgG antibody (1:2000; Invitrogen) for 3 hours at room temperature. Tissues were mounted onto slides with Vectashield (Vector Labs) (for antibodies, see Table 1).

Whole-cell patch clamp

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed on GFP-labeled POMC neurons in the acute ARH-containing hypothalamic slices from POMC-EGFP mice. Six- to 12-week-old mice (males or females) were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and transcardially perfused (23, 24) with a modified ice-cold sucrose-based cutting solution (adjusted to pH 7.3) containing 10mM NaCl, 25mM NaHCO3, 195mM sucrose, 5mM glucose, 2.5mM KCl, 1.25mM NaH2PO4, 2mM Na pyruvate, 0.5mM CaCl2, and 7mM MgCl2 bubbled continuously with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (25). The mice were then decapitated, and the entire brain was removed and immediately submerged in ice-cold sucrose-based cutting solution. Coronal sections containing the medial amygdala (270 μm) were cut with a Microm HM 650V vibratome (Thermo Scientific). The slices were recovered for at least 1 hour at 34°C in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (adjusted to pH 7.3) containing 126mM NaCl, 2.5mM KCl, 2.4mM CaCl2, 1.2mM NaH2PO4, 1.2mM MgCl2, 11.1mM glucose, and 21.4mM NaHCO3 (26) saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 before recording.

Slices were transferred to the recording chamber and allowed to equilibrate for at least 10 minutes before recording. The slices were perfused at 34°C in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid at a flow rate of 1.8–2 mL/min. GFP-positive POMC neurons in the ARH were visualized using epifluorescence and IR-DIC imaging on an upright microscope (Eclipse FN-1; Nikon) equipped with a moveable stage (MP-285; Sutter Instrument). Patch pipettes with resistances of 5–7 MΩ were filled with intracellular solution (adjusted to pH 7.3) containing 128mM K gluconate, 10mM KCl, 10mM HEPES, 0.1mM EGTA, 2mM MgCl2, 0.05mM Na-GTP, 0.05mM Mg-ATP, and 0.003mM Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescent dyes (25). Recordings were made using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instrument), sampled using Digidata 1440A, and analyzed offline with pClamp 10.3 software (Axon Instrument). Series resistance was monitored during the recording, and the values were generally less than 10 MΩ and were not compensated. The liquid junction potential was +12.5 mV and was corrected after the experiment. Data would be excluded if the series resistance increased dramatically during the experiment or without overshoot for action potential.

PPT (100nM, 50-ms puff by about 4-ψ pressure ejection with Picospritzer III) (27, 28) was applied to the recorded cells, with or without the combination of tetrodotoxin (TTX) perfusion (1μM, 4–6 min at 2 mL/min; R&D Systems) and/or intracellular application of wortmannin (10μM).

Real-time RT-PCR

A separate cohort of female Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre and Pik3caf/f littermates were decapitated, pituitaries were quickly microdissected and stored at −80°C. As described previously (21), total mRNA was isolated using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol and reverse transcription reactions were performed from 2 μg of total mRNA using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kits (Invitrogen). Samples were amplified on a CFX384 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) using SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Correct melting temperatures for all products were verified after amplification. Results were normalized against the expression of house-keeping gene cyclophilin. Primer sequences were: Pik3ca-forward, TGCAAAGAAGCTGTGGACCT and Pik3ca-reverse, CAATGACTTGCTCTGGCACA; and cyclophilin-forward, TGGAGAGCACCAAGACAGACA and cyclophilin-reverse, TGCCGGAGTCGACAATGAT.

Statistical analyses

The data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism to evaluate normal distribution and variations within and among groups. Methods of statistical analyses were chosen based on the design of each experiment and are indicated in figure legends. P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Effects of estrogen replacement in female mice lacking ERα in POMC progenitor neurons

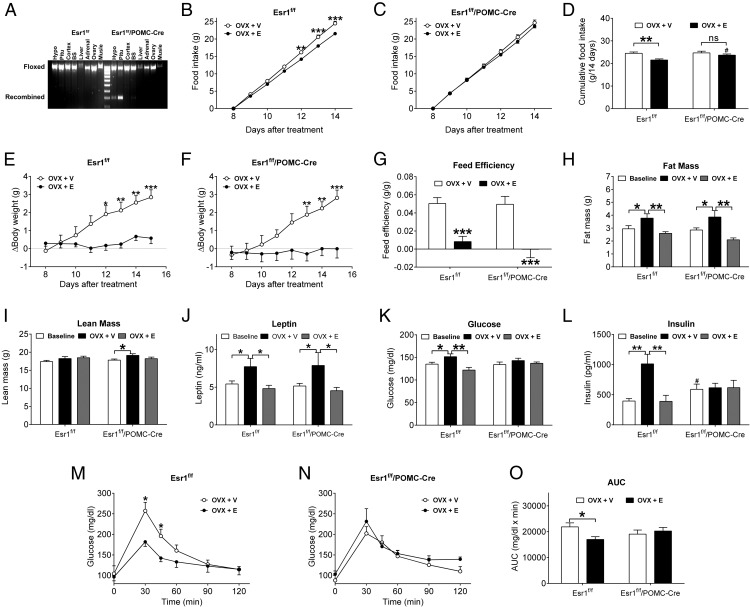

We have previously generated and validated a mutant mouse model, Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre, which lacks ERα (encoded by the Esr1 gene) selectively in POMC progenitor neurons (7). Here, we confirmed that the recombined Esr1 allele was only detected in the POMC-containing tissues, including the hypothalamus and pituitary, in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 1A). The major phenotypes of these mutant females include chronic hyperphagia and associated body weight gain compared with their littermate controls (Esr1f/f) (7). These findings suggest that ERα in POMC progenitor neurons is required to maintain normal food intake, likely by mediating estrogenic actions. Here, we examined the effects of chronic estrogen replacement on food intake in Esr1f/f and Esr1f/f /POMC-Cre female mice. To this end, female Esr1f/f and Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre littermates (12 wk of age) received bilateral OVX and were implanted with sc 17β-estradiol pellets (0.5 μg/d, OVX+E) or empty pellets (OVX+V). After a 7-day recovery, we monitored food intake and found that, OVX+E Esr1f/f mice consumed significantly less food than OVX+V Esr1f/f mice (Figure 1, B and D), whereas in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice, OVX+E failed to significantly alter food intake (Figure 1, C and D). In addition, OVX+E Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice consumed significantly more food than OVX+E Esr1f/f mice (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Effects of estrogens in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice. A, PCR amplification of genomic DNA from the hypothalamus (Hypo), pituitary (Pitu), cortex, brain stem (BS), liver, adrenal gland, ovary, and muscle of Esr1f/f and Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice. The floxed Esr1 allele (1089 bp) was detected in all tissues from both mice; the recombined Esr1 allele (560 bp) was only detected in POMC cell-containing tissues (the Hypo and Pitu). B–D, Cumulative food intake over day 8–14 in OVX+V or OVX+E Esr1f/f (B) or Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre (C) female mice. Cumulative food intake over 14 days was calculated (D). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–10 in each group. **, P < .01 and ***, P < .001 between OVX+V and OVX+E treatment within the same genotype group; #, P < .05 between 2 genotype groups treated with OVX+E in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. E and F, Changes in body weight in OVX+V or OVX+E Esr1f/f (E) or Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre (F) female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–10 in each group. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. G, Feed efficiency was calculated as changes in body weight/cumulative food intake to estimate energy expenditure. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–10 in each group. ***, P < .001 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. H, Fat mass measured at the baseline (before OVX+V or OVX+E) or 4 weeks afterwards in Esr1f/f or Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–18 in each group. *, P < .05 and **, P < .01 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. I, Lean mass measured at the baseline (before OVX+V or OVX+E) or 4 weeks afterwards in Esr1f/f or Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–18 in each group. *, P < .05 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. J, Serum leptin levels measured at the baseline (before OVX+V or OVX+E) or 4 weeks afterwards in Esr1f/f or Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–18 in each group. *, P < .05 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. K, Fed blood glucose levels measured at the baseline (before OVX+V or OVX+E) or 4 weeks afterwards in Esr1f/f or Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–18 in each group. *, P < .05 and **, P < .01 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. L, Fed serum insulin levels measured at the baseline (before OVX+V or OVX+E) or 4 weeks afterwards in Esr1f/f or Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–18 in each group. **, P < .01 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests; #, P < .05 between the baseline of Esr1αf/f and the baseline of Esr1αf/f/POMC-Cre mice in simple t tests. M and N, Glucose tolerance tests in Esr1f/f (M) or Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre (N) female mice 4 weeks after OVX+V or OXV+E treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–10 in each group. *, P < .05 in simple t tests at each time point. O, Area under the curve (AUC) of glucose tolerance tests in M and N. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–10 in each group. *, P < .05 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests.

We also monitored body weight changes in Esr1f/f and Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice treated with OVX+V or OVX+E. As expected, OVX+V Esr1f/f mice quickly gained body weight after estrogen depletion, and estrogen replacement effectively prevented this body weight gain as demonstrated by significantly reduced body weight in OVX+E Esr1f/f mice (Figure 1E). Surprisingly, body weight in OVX+E Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice was also significantly reduced compared with OVX+V Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice (Figure 1F), to a similar degree as seen in OVX+E Esr1f/f mice (Figure 1E). We estimated energy expenditure indirectly as a measure of feed efficiency. Consistent with known effects of estrogens to simulate energy expenditure (3, 30), OVX+E mice showed significantly decreased feed efficiency compared with OVX+V mice (Figure 1G). Interestingly, this OVX+E-induced decreases in feed efficiency appeared to be more robust in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre females than in Esr1f/f females (Figure 1G), which may have contributed to similar body weight reduction despite slightly higher food intake observed in OVX+E Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Consistent with alterations in body weight, we found that OVX+V significantly increased fat mass compared with the baseline (before OVX) in Esr1f/f mice, whereas OVX+E completely rescued the hyperadiposity in these mice (Figure 1H). Similarly, fat mass in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice was significantly increased by OVX+V treatment, whereas this hyperadiposity was prevented in OVX+E Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 1H). Esr1f/f mice showed comparable lean mass at baseline, after OVX+V or OVX+E treatment (Figure 1I). Notably, OVX+V treatment induced a small but significant increase in lean mass in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 1I). Consistent with changes in body weight and fat mass in both Esr1f/f and Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice, OVX+V treatment significantly elevated serum leptin levels from the baseline, and this hyperleptinemia was rescued by OVX+E treatment (Figure 1J).

We further characterized the glucose homeostasis in these mice. To this end, fed blood glucose/insulin levels (after a 2-h short fast to ensure empty stomach) were measured before (baseline) or after OVX+V/OVX+E treatment. First, we found that although the baseline glucose levels were comparable between Esr1f/f and Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 1K), baseline insulin levels in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre females were significantly higher than those in Esr1f/f females (Figure 1J). We then examined effects of estrogen depletion and replacement on glucose and insulin levels in these mice. We showed that in female Esr1f/f mice, OVX+V significantly elevated fed glucose levels compared with baseline levels (Figure 1K), which was associated with remarkable increases in insulin levels (Figure 1L). Consistent with earlier reports (1), we found that OVX+E treatment almost completely rescued the hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in female Esr1f/f mice (Figure 1, K and L). In contrast, glucose and insulin levels in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice were not altered by either OVX+V or OVX+E (Figure 1, K and L). We further tested glucose tolerance in 4 groups of mice and showed that OVX+E Esr1f/f mice had significantly improved glucose tolerance compared with OVX+V Esr1f/f females (Figure 1, M and O), whereas OVX+E Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice and OVX+V Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice showed comparable glucose tolerance (Figure 1, N and O). Together, these results indicate that female mice lacking ERα only in POMC progenitor neurons develop insulin resistance at baseline and were insensitive to glucose-regulatory effects of either estrogen depletion or replacement.

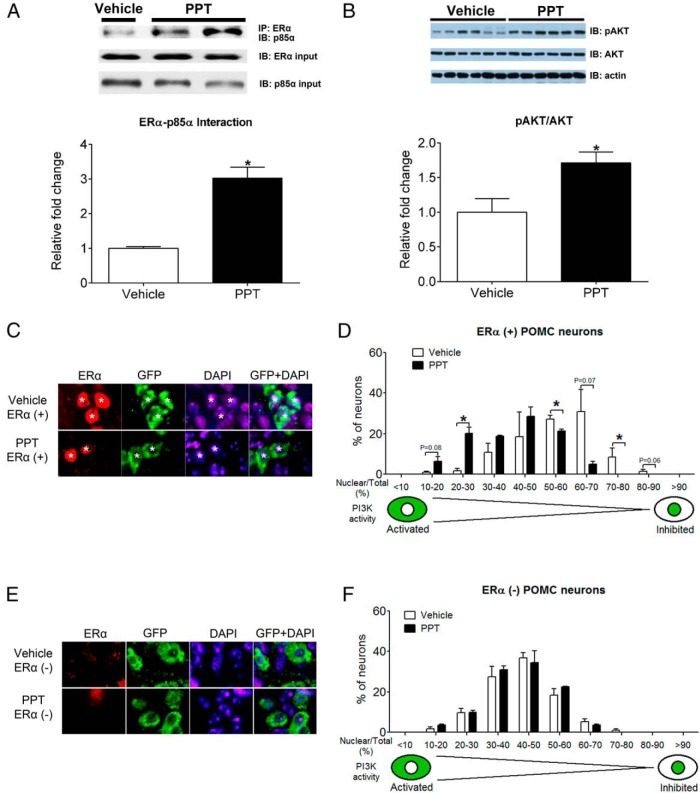

The ERα agonist stimulates the PI3K pathway in POMC progenitor neurons

In order to determine whether ERα signals activate the PI3K pathway in the hypothalamus, we tested effects of central administration of PPT, a highly selective ERα agonist (28), on the PI3K pathway in OVX C57Bl6 females. We showed that i.c.v. injections of PPT (500 pmol, 30 min) enhanced the interaction of ERα and p85α, a regulatory subunit of PI3K in the hypothalamus (Figure 2A). Further, we showed that PPT significantly increased phosphorylation of Akt, a known PI3K downstream event, whereas the total Akt levels in the hypothalamus were not affected (Figure 2B). In order to further examine effects of central administration of PPT on the PI3K pathway specifically in ARH POMC progenitor neurons, we crossed Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mice to POMC-Cre mice to generate Rosa26-FoxO1GFP/POMC-Cre reporter mice which express FoxO1GFP fusion protein only in POMC progenitor neurons (16). Because FoxO1 translocates to the cytoplasm or to the nucleus upon activation or inhibition of the PI3K pathway, respectively (31), we quantified FoxO1 (GFP) signals in the nucleus vs total cell (N/T ratio) in each POMC progenitor neuron to estimate PI3K activity. Given that only a portion of ARH POMC progenitor neurons express ERα (7), we performed dual immunohistochemistry for GFP and ERα to examine PI3K activity in ERα(+) POMC progenitor neurons and ERα(−) POMC progenitor neurons, respectively. In ERα(+) POMC progenitor neurons, i.c.v. injections of PPT (500 pmol, 30 min) significantly increased the number of neurons with activated PI3K (N/T ratio between 20% and 30%) and robustly decreased the number of neurons with inhibited PI3K activity (N/T ratio between 50% and 60% and between 70% and 80%) (Figure 2, C and D). Together, these data indicate that stimulation of ERα activates the PI3K pathway in ARH POMC progenitor neurons. Interestingly, PPT did not affect PI3K activity in ERα(−) POMC progenitor neurons compared with vehicle treatment (Figure 2, E and F), which further supports that PPT-induced PI3K activity in ERα(+) POMC progenitor neurons are likely mediated by ERα.

Figure 2.

Effects of a selective ERα agonist on the PI3K pathway in POMC progenitor neurons. A, Interaction between ERα and p85α in the hypothalamus from OVX C57Bl6 female mice 30 minutes after i.c.v. injections of PPT (500 pmol) or vehicle. Upper panel, Representative blots showing interaction between ERα and p85α, ERα inputs and p85α inputs. Lower panel, Summary quantification for ERα-p85α interaction showing relative folds calculated as the ratios of interaction blots and ERα inputs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 3–4 in each group. *, P < .05 in simple t tests. B, Phosphorylation of Akt (at Ser473) in the hypothalamus from OVX C57Bl6 female mice 30 minutes after i.c.v. injections of PPT (500 pmol) or vehicle. Total Akt and actin were measured as loading controls. Upper panel, Representative blots showing immunoblotting for pAkt, total Akt, and action. Lower panel, Summary quantification for the ratios of pAkt/Akt. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6 in each group. *, P < .05 in simple t tests. C–F, FoxO1GFP translocation in POMC progenitor neurons in OVX Rosa26-FoxO1GFP/POMC-Cre female mice 30 minutes after i.c.v. injections of PPT (500 pmol) or vehicle. C, Representative immunofluorescence images showing ERα, GFP (Foxo1GFP), DAPI, and GFP+DAPI in ERα(+) POMC progenitor neurons. Asterisks indicate cells labeled by ERα and GFP. D, Number of ERα(+) POMC progenitor neurons (% of total) showing various levels of FoxO1GFP N/T ratio. E, Representative immunofluorescence images showing ERα, GFP, DAPI, and GFP+DAPI in ERα(−) POMC progenitor neurons. F, Number of ERα (−) POMC progenitor neurons (% of total) showing various levels of FoxO1GFP N/T ratio. Note that lower N/T ratio corresponds to activated PI3K and higher N/T ratio corresponds to inhibited PI3K. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 3 mice in each group. *, P < .05 and **, P < .01 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests.

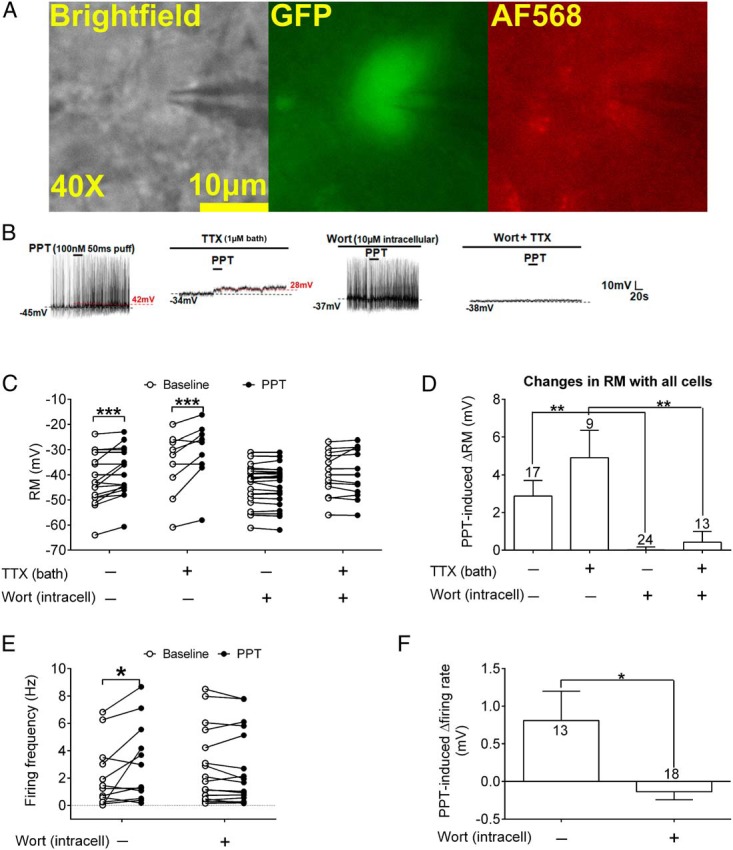

The ERα agonist stimulates POMC neurons via the PI3K pathway

We next recorded electrophysiological responses to PPT in identified POMC neurons (in POMC-EGFP brain slices) (Figure 3A). We showed that PPT (100nM, 50-ms puff) caused rapid depolarization in 9/17 POMC neurons (n = 17) (Figure 3, B–D, and Table 2). PPT's effects on the resting membrane potential were further tested in these 9 responsive POMC neurons after bath perfusion of TTX (1μM) which blocks synaptic neurotransmission. In the presence of TTX, PPT still depolarized 7/9 POMC neurons (n = 9) (Figure 3, B–D, and Table 2). To determine whether PPT-induced depolarization requires PI3K activity in POMC neurons, we blocked PI3K activity in POMC neurons with intracellular application of wortmannin (a PI3K inhibitor, 10μM). In the presence of wortmannin, PPT only depolarized 3/24 POMC neurons tested (n = 24) (Figure 3, B–D, and Table 2). Similarly, PPT only depolarized 3/13 POMC progenitor neurons that were cotreated with TTX and wortmannin (n = 13) (Figure 3, B–D, and Table 2). In POMC neurons that showed spontaneous firing at the basal condition, we also analyzed effects of PPT on firing rate. We found that PPT induced significant increases in firing rate, whereas intracellular application of wortmannin blocked these PPT-induced effects (n = 13 or 18) (Figure 3, B, E, and F). Together, these data indicate that stimulation of ERα rapidly activates POMC neurons in the ARH, and these effects at least partly require PI3K in POMC neurons.

Figure 3.

Effects of a selective ERα agonist on neural activities of ARH POMC neurons. A, ARH-containing brain slices from a POMC-EGFP mouse were used to record POMC neurons in the ARH. B, Representative electrophysiological traces in the current clamp showing effects of PPT (100nM, 50-ms puff) in the presence or absence of TTX (1μM, bath perfusion) and/or wortmannin (Wort) (10μM, intracellular application). C, Summary of membrane potential in POMC neurons at the baseline and after PPT treatment in the presence or absence of TTX and/or Wort. n = 9–24 neurons in each group. ***, P < .001 between the baseline and PPT in two-way ANOVA repeated measurements followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. D, PPT-induced changes in membrane potential in POMC neurons in the presence or absence of TTX and/or Wort. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 9–24 neurons in each group. **, P < .01 in two-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. E, Summary of firing frequency in POMC neurons at the baseline and after PPT treatment in the presence or absence of Wort. n = 13 or 18 neurons in each group. *, P < .05 between the baseline and PPT in two-way ANOVA repeated measurements followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. F, PPT-induced changes in firing frequency in POMC neurons in the presence or absence of Wort. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 13 or 18 neurons in each group. *, P < .05 in two-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests.

Table 2.

Number of POMC Neurons That Responded to PPT

| Treatment | Numbers (% of Total) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Depolarize | Hyperpolarize | No Response | |

| PPT | 17 | 9 (52.9%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (47.1%) |

| PPT + TTX | 9 | 7 (77.8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (12.2%) |

| PPT + Wort | 24 | 3 (12.5%)a | 0 (0%) | 21 (87.5%)a |

| PPT + Wort + TTX | 13 | 3 (23.1%)b | 0 (0%) | 10 (76.9%)b |

Abbreviation: Wort, wortmannin.

Depolarization was defined as more than 1-mV elevations in resting membrane potential within 3 minutes after 50-millisecond PPT puff application; hyperpolarization was defined as more than 1-mV reductions in resting membrane potential within 3 minutes after 50-millisencond PPT puff application; other neurons were defined no response.

P < .01 vs PPT group in χ2 test.

P < .01 vs PPT+TTX group in χ2 test.

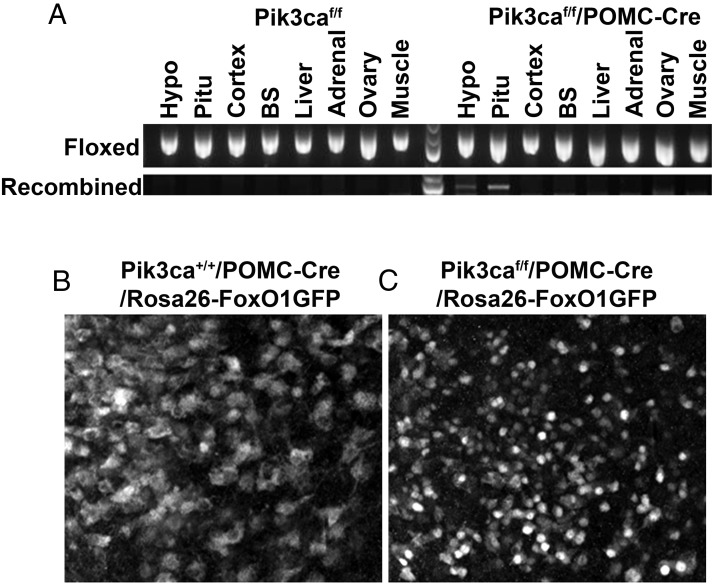

Validation of mice lacking PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons

In order to test the physiological relevance of PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons, we crossed Pik3caf/f mice with POMC-Cre mice to generate Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice, which lack p110α (a catalytic subunit of PI3K, encoded by the Pik3ca gene) only in POMC cells. We confirmed that the recombined Pik3ca allele was only detected in the POMC-containing tissues, including the hypothalamus and pituitary, in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 4A). In a subset of breeding, we introduced the Rosa26-FoxO1GFP allele to generate Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mice and Pik3ca+/+/POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mice. We showed that FoxO1GFP (demonstrated by GFP immunohistochemistry) is distributed in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm of POMC progenitor neurons of Pik3ca+/+/POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mice (Figure 4B). In contrast, FoxO1GFP is exclusively distributed in the nuclei of POMC progenitor neurons of Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mice (Figure 4C). These results indicate that deletion of p110α in POMC progenitor neurons in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice is sufficient to inhibit PI3K activity.

Figure 4.

Validation of Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice. A, PCR amplification of gDNA from the hypothalamus (Hypo), pituitary (Pitu), cortex, brain stem (BS), liver, adrenal gland, ovary, and muscle of Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice. The floxed Pik3ca allele (530 bp) was detected in all tissues from both mice; the recombined Pik3ca allele (947 bp) was only detected in POMC cell-containing tissues (the Hypo [hypothalamus] and Pitu [pituitary]). B and C, Immunofluorescence for GFP (white) in the Hypo organotypic slices cultured from Pik3ca+/+/POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mice (B) and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre/Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mice (C).

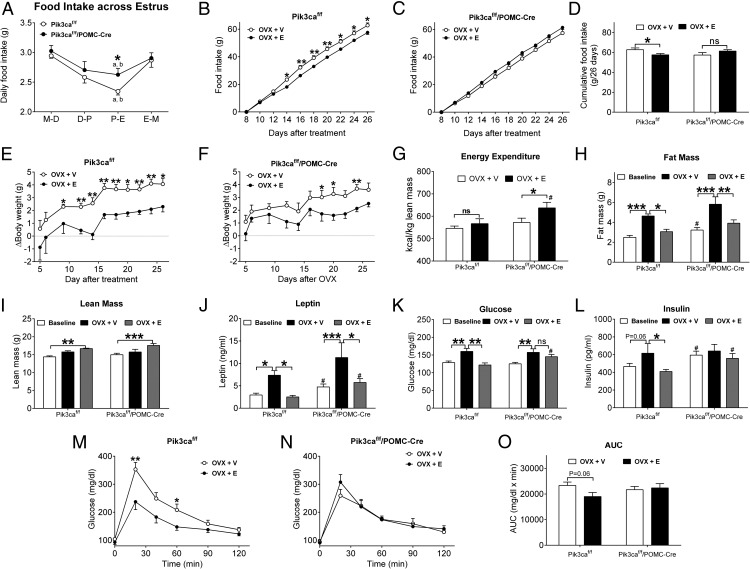

Inhibition of PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons attenuates estrous-dependent regulation on food intake in females

It has been previously reported that feeding behavior in female mice fluctuates depending on the estrous stages, and food intake significantly decreases between proestrus and estrus (32), which coincides with a surge in estrogen levels. Similar phenomena are also observed in female rats (33, 34) and women (35). Consistent with these, we showed that food intake in gonad-intact female Pik3caf/f mice (controls) was highest between metestrus and diestrus, declined during proestrus, and reached its nadir between proestrus and estrus (Figure 5A). In these mice, food intake in the proestrous-estrous (P-E) phase was significantly lower than that in metestrous-diestrous and estrous-metestrous (E-M) phases by 20% and 18%, respectively (Figure 5A). Similar estrous-dependent fluctuations in food intake were observed in gonad-intact Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice, however, with an attenuated magnitude. Thus, in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre females, food intake in the P-E phase was lower than that in the metestrous-diestrous phase and in E-M phase by only 13% and 10%, respectively (Figure 5A). Importantly, food intake in the P-E phase was significantly higher in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre females than in Pik3caf/f females (Figure 5A). It is worth noting that differences in food intake were observed only during the P-E phase, whereas food intake in most the estrous cycle was comparable between Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre females (Figure 5A). Nevertheless, these results indicate that PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons is at least partly required to mediate the estrous-dependent regulation on food intake in female mice.

Figure 5.

Effects of estrogens in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. A, Daily food intake at the different estrous stages in gonad-intact Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. M-D, metestrous-diestrous phase; D-P, diestrous-proestrous phase. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 14 or 16 in each group. a, P < .05 between P-E and M-D within the same genotype; b, P < .05 between P-E and E-M within the same genotype; *, P < .05 between 2 genotypes in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. B–D, Cumulative food intake over day 8–26 in OVX+V or OVX+E Pik3caf/f (B) or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre (C) female mice. Cumulative food intake over 26 days was calculated (D). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–8 in each group. *, P < .05 and **, P < .01 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. E and F, Changes in body weight in OVX+V or OVX+E Pik3caf/f (E) or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre (F) female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–8 in each group. *, P < .05 and **, P < .01 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. G, Averaged daily energy expenditure directly measured by Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System metabolic cages in Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice 7 days after OVX+V or OVX+E treatment. Note that energy expenditure was normalized by lean mass. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 7 in each group. *, P < .05 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests; #, P < .05 between of Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice after OVX+E in simple t tests. H, Fat mass measured at the baseline (before OVX+V or OVX+E) or 5 weeks afterwards in Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–17 in each group. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests; #, P < .05 between the baseline of Pik3caf/f and the baseline of Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice in simple t tests. I, Lean mass measured at the baseline (before OVX+V or OVX+E) or 5 weeks afterwards in Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–17 in each group. **, P < .01 and ***, P < .001 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. J, Serum leptin levels measured at the baseline (before OVX+V or OVX+E) or 5 weeks afterwards in Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–17 in each group. *, P < .05 and ***, P < .001 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests; #, P < .05 between of Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice at either the baseline or after OVX+E in simple t tests. K, Fed blood glucose levels measured at the baseline (before OVX+V or OVX+E) or 5 weeks afterwards in Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–17 in each group. **, P < .01 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests; #, P < .05 between of Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice after OVX+E in simple t tests. L, Fed serum insulin levels measured at the baseline (before OVX+V or OVX+E) or 5 weeks afterwards in Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–17 in each group. *, P < .05 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests; #, P < .05 between of Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice at either the baseline or after OVX+E in simple t tests. M and N, Glucose tolerance tests in Pik3caf/f (M) or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre (N) female mice 5 weeks after OVX+V or OVX+E treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–8 in each group. *, P < .05 and **, P < .01 in simple t tests at each time point. O, Area under the curve (AUC) of glucose tolerance tests in M and N. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–8 in each group.

Effects of estrogen replacement in female mice lacking PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons

We then examined effects of estrogen replacement on food intake in Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. OVX+E Pik3caf/f mice consumed significantly less food than OVX+V Pik3caf/f mice (Figure 5, B and D), whereas these differences were not observed between OVX+E and OVX+V Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice (Figure 5, C and D). In addition, OVX+E Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice trended to consume more food than OVX+E Pik3caf/f mice (P = .09) (Figure 5D, 2 black bars). Thus, these data indicate that PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons is required to mediate chronic effects of estrogens to suppress food intake.

We also monitored body weight changes in Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice treated with OVX+V or OVX+E. As expected, OVX+E Pik3caf/f mice showed significantly reduced body weight compared with OVX+V Pik3caf/f mice (Figure 5E). Body weight in OVX+E Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice was also significantly reduced compared with OVX+V Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 5F). Using Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS) metabolic cages, we directly measured energy expenditure in Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice 7 days after OVX+V or OVX+E treatment. Consistent with known effects of estrogens to stimulate energy expenditure (3, 30), we observed an overall stimulatory effect of OVX+E on energy expenditure (vs OVX+V) when analyzing data in both Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice (F1,24 = 4.698, P < .05 in two-way ANOVA). Interestingly, when analyzing data in each genotype, we only detected a significant stimulatory effect of OVX+E in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice but not in Pik3caf/f mice; further, energy expenditure in OVX+E Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice was significantly higher than that in OVX+E Pik3caf/f mice (Figure 5G). The enhanced energy expenditure in OVX+E Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice may have contributed to similar body weight reduction despite slightly higher food intake observed in OVX+E Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice.

Further, we found that OVX+V significantly increased fat mass compared with the baseline in Pik3caf/f mice, whereas OVX+E completely rescued the hyperadiposity in these mice (Figure 5H). Similarly, fat mass in Pik3caf/f/ POMC-Cre mice was significantly increased by OVX+V, whereas this hyperadiposity was prevented in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice treated with OVX+E (Figure 5H). Notably, Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice showed a modest but significant increase in fat mass at the baseline compared with Pik3caf/f female mice (Figure 5H). Interestingly, we observed that OVX+E modestly increased the lean mass compared with the baseline in both Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre females (Figure 5I). Consistent with the observed alterations in body weight and fat mass, serum leptin levels were significantly elevated by OVX+V, but this hyperleptinemia was rescued by OVX+E, in both Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 5J). Notably, leptin levels in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice were significantly higher than those in Pik3caf/f mice, at both the baseline and after OVX+E treatment (Figure 5J). A similar trend was observed in OVX+V Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice but without reaching statistical significance (Figure 5J).

We further characterized the glucose homeostasis in these mice. We observed that in female Pik3caf/f mice, OVX+V significantly elevated fed glucose levels compared with the baseline levels, and this hyperglycemia was rescued in OVX+E Pik3caf/f mice (Figure 5K). In Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice, OVX+V induced similar elevations in fed glucose levels, but OVX+E failed to fully rescue this hyperglycemia. Importantly, fed glucose in OVX+E Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice was significantly higher than in OVX+E Pik3caf/f mice (Figure 5K). In addition, we showed that OVX+V trended to elevate fed insulin levels in female Pik3caf/f mice, which was significantly rescued in OVX+E Pik3caf/f mice (Figure 5L). Importantly, neither OVX+V nor OVX+E treatment significantly altered insulin levels in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 5L). Interestingly, insulin levels in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice were significantly higher than Pik3caf/f mice, at both the baseline and after OVX+E treatment (Figure 5L). We further showed that OVX+E treatment significantly improved glucose tolerance in Pik3caf/f females (Figure 5, M and O), but these effects were blocked in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice (Figure 5, N and O). In summary, as expected, depletion of endogenous estrogen by OVX (OVX+V) induced hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, and impaired glucose tolerance in Pik3caf/f female mice, all of which can be rescued by estrogen replacement in OVX mice (OVX+E). In contrast, Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice developed insulin resistance at the baseline condition and were insensitive to glucose-regulatory effects of estrogen replacement.

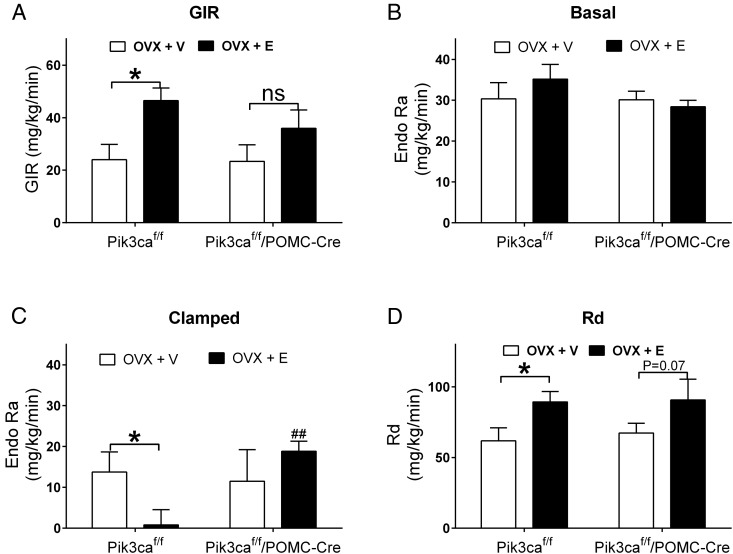

We used the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp to further evaluate insulin sensitivity in mice. In Pik3caf/f female mice, we found that estrogen replacement significantly increased the whole-body insulin sensitivity, demonstrated by elevated GIR in OVX+E group compared with OVX+V group (Figure 6A). Importantly, the insulin-sensitizing effects of OVX+E were attenuated in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice (Figure 6A). We further analyzed endogenous glucose appearance (EndoRa, largely resulting from hepatic glucose production) at the basal and clamped conditions. The basal EndoRa was comparable in all 4 groups (Figure 6B). Under the clamped condition, OVX+E induced a robust and significant reduction in EndoRa in Pik3caf/f mice compared with OVX+V Pik3caf/f mice, but these effects were abolished in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice (Figure 6C). Indeed, EndoRa in OVX+E Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice was significantly higher than that in OVX+E Pik3caf/f female mice (Figure 6C). Interestingly, OVX+E significantly increased glucose Rd in Pik3caf/f female mice, and a similar trend was also observed in OVX+E Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Effects of estrogens on hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. A, GIR in OVX+V or OVX+E Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–7 in each group. *, P < .05 in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. B, EndoRa at the basal condition in OVX+V or OVX+E Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–7 in each group. C, EndoRa during the clamped condition in OVX+V or OVX+E Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–7 in each group. *, P < .05 between OVX+V and OVX+E; ##, P < .01 between Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. D, Glucose Rd at the clamped condition in OVX+V or OVX+E Pik3caf/f or Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–7 in each group. *, P < .05 between OVX+V and OVX+E in two-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests.

Because POMC-Cre also induce DNA recombination in POMC (ACTH) cells in the pituitary, we examined the mRNA levels of p110α in the pituitary of Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre females. We detected a significant decrease in p110α mRNA in the pituitary of Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice (Figure 7A), suggesting that Pik3ca is also deleted from ACTH cells. However, no significant changes in serum corticosterone were observed in these mice after either OVX+V or OVX+E treatments (Figure 7B). Therefore, it is unlikely that the feeding and metabolic phenotypes described above are due to deletion of Pik3ca in pituitary ACTH cells.

Figure 7.

Pituitary of Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice. A, Relative mRNA levels of p110α measured by real-time RT-PCR from the pituitaries of female Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre littermates. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 5 or 7 in each group. *, P < .05 in simple t tests. B, Serum corticosterone levels measured in female Pik3caf/f and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre littermates treated with OVX+V or OVX+E mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 7–8 in each group.

Discussion

The ERα-PI3K cascade in POMC progenitor neurons regulates feeding behavior in female mice

Accumulating evidence indicates that estrogens suppress food intake in females. For example, food intake in female rodents (32–34) and in women (35) fluctuates across the estrous cycle and the lowest food intake is tightly associated with the estrogen surge. Importantly, administration of 17β-estradiol or its analogs decreases food intake in rodents (3, 36, 37). These anorexigenic effects of estrogens are believed to be mediated primarily through ERα in the brain, as central or systemic administration of the ERα agonist (PPT) suppresses food intake in rats and mice (38, 39), effects that are blocked by an ERα antagonist (40) or by genetic deletion of ERα (39). Furthermore, microinjections of the ERα agonist into the ARH suppress food intake in OVX rats (41), indicating that ERα expressed in the ARH is sufficient to mediate estrogenic actions on food intake. We have previously shown that abundant ERα is coexpressed by POMC progenitor neurons in the ARH (7). Here, we demonstrated that loss of ERα in POMC progenitor neurons blunted anorexigenic effects of 17β-estradiol. Consistently, we have previously observed that these mutant females develop chronic hyperphagia (7). Together, these data indicate that ERα expressed by ARH POMC progenitor neurons is at least partly required to mediate anorexigenic effects of estrogens.

Although most POMC progenitor neurons reside in the ARH of the hypothalamus, a small subset of POMC progenitor neurons are also found in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) of the brain stem, which are implicated in the regulation of feeding (42). In addition, estrogens increase c-fos immunoreactivity in the NTS via ERα-mediated mechanisms (37). Notably, we showed that ERα was deleted from a few NTS POMC progenitor neurons (2 neurons per section) in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice (7). Thus, ERα expressed by NTS POMC progenitor neurons may also partially contribute to the estrogen-induced anorexia. One limitation of the experimental design is that the current models using POMC-Cre would not distinguish the roles of POMC progenitor neurons in the NTS from those in the ARH. POMC-Cre mice also express transient Cre activity in a portion of agouti-related peptide (AgRP)-expressing neurons in the ARH (43). Importantly, AgRP neurons do not express ERα (32). Thus, the transient Cre activity in AgRP neurons should not confound the phenotypes in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice. Recent evidence indicates that POMC-Cre mice also express transient Cre activity in a portion of kisspeptin-expressing neurons in the ARH (44). Although no feeding and body weight phenotypes have been reported in mice with ERα deleted selectively in kisspeptin neurons (45, 46), we could not fully exclude the possibility that a partial deletion of ERα in ARH kisspeptin neurons may also contribute to the phenotypes observed in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice.

Notably, effects of 17β-estradiol on food intake appeared to be only attenuated in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice. The residual effects of 17β-estradiol suggest that ERα in other brain regions may also contribute to the estrogen-induced anorexia. Notably, pharmacological stimulations of ERα in the preoptic area of the hypothalamus or in the dorsal raphe nuclei are also sufficient to inhibit food intake in OVX rats (41), suggesting that redundant ERα-expressing cell populations exist in the brain to mediate estrogenic actions on food intake. Alternatively, our results also suggest that other ERs contribute to the anorexia effects of 17β-estradiol. Indeed, recent evidence has implicated previously unrecognized roles of ERβ (47, 48) and G protein-coupled receptor 30 (49) in the regulation of energy homeostasis.

Emerging evidence indicates that the PI3K pathway may mediate estrogenic effects in POMC progenitor neurons. For example, the membrane impermeable estradiol-BSA stimulates excitability of POMC neurons (11, 50). The PI3K pathway at least partly mediates this effect, because estradiol-induced activation of POMC neurons is significantly blunted by the PI3K inhibitors, wortmannin and LY294002 (11). Consistent with these earlier findings, we first demonstrated that i.c.v. PPT (the ERα agonist) in OVX female mice rapidly enhanced interactions between ERα and p85α (a PI3K regulatory subunit) and stimulated phosphorylation of Akt (a PI3K downstream event) in the hypothalamus. Further, the FoxO1GFP reporter assay revealed that i.c.v. PPT enhanced FoxO1 nuclear exclusion in ERα(+) POMC progenitor neurons, suggesting elevated PI3K activity. In addition, we showed that PPT rapidly depolarized POMC neurons and increased their firing rate, and these effects were largely blocked by intracellular application of wortmannin. Together, these results provide complementary evidence that ERα is functionally coupled to the PI3K pathway in POMC progenitor neurons.

We then used the Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mouse model to test the physiological relevance of the PI3K cascade in POMC progenitor neurons in the regulation of food intake in female mice. Similar to Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre mice, suppression in food intake by OVX+E treatment was blunted in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Because Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre females displayed intact estrous cycles, we also evaluated the estrous-dependent fluctuations in food intake of these mice. We found that the suppression in food intake in the P-E phase was significantly attenuated in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Collectively, our observations in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre and Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre mice support a model that the ERα-PI3K cascade in POMC progenitor neurons at least partly mediates effects of estrogens to inhibit feeding in female mice.

Notably, despite the fact that estrogen-induced anorexia was blunted in mice lacking ERα or p110α in POMC progenitor neurons, estrogens induced comparable reductions in body weight and body fat in these mutant mice as their controls. The lack of body weight/fat phenotype can be attributed to enhanced energy expenditure in mutant OVX mice treated with E. We speculate that this increased sensitivity to estrogen-induced energy expenditure may be due to compensations in other estrogen-responsive neurons, including those in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMH) (7, 30, 51) and the medial amygdala (52), which are known to stimulate energy expenditure.

The ERα-PI3K cascade in POMC progenitor neurons mediates estrogenic actions to maintain insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis in female mice

It has been shown that estrogens, acting via ERα, improve insulin sensitivity and glucose balance in females (1). These beneficial effects of estrogens appear to be mediated by multiple ERα-expressing cell populations, including those in the fat (53) and in the liver (54). Here, we provide evidence that ERα-mediated actions in POMC progenitor neurons also contribute to the regulation of insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis. First, we found that gonad-intact Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice showed hyperinsulinemia with normal glucose levels compared with their controls, suggesting the presence of insulin resistance under the baseline condition. More importantly, we demonstrated that Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice were insensitive to the beneficial effects of estrogen replacement to lower blood glucose and insulin or to improve glucose tolerance. Together, these results indicate that ERα in POMC progenitor neurons is required to mediate estrogenic actions to maintain normal glucose homeostasis in female mice.

Notably, although estrogenic actions on insulin and glucose levels are blocked in Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female, their effects to suppress body weight gain and hyperadiposity are not affected in these mutant females. Similar segregation of glycemic control and body weight regulation has been observed in other models with genetic manipulations in POMC progenitor neurons. For example, reexpression of the leptin receptor in POMC progenitor neurons from the leptin receptor-null background, whereas only modestly reduces body weight, completely normalizes hyperglycemia (55). Similarly, deletion of the serotonin 2C receptor only in POMC neurons leads to profound insulin resistance in mice, before these mutant mice become significantly obese (56). These findings argue that POMC progenitor neurons may coordinate multiple hormonal/neural cues to regulate insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis, and these glucose-regulatory effects are independent of their roles in body weight control. Supporting this notion, effects of central melanocortins (the POMC gene products) on body weight balance vs on glycemic control are mediated by anatomically distinct neural populations expressing the melanocortin 4 receptors (57, 58).

Another major finding is that PI3K activity in POMC progenitor neurons is required to mediate estrogenic effects to regulate insulin sensitivity and glucose balance. It is noteworthy that Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice showed remarkably similar glucose/insulin profile as Esr1f/f/POMC-Cre female mice. Thus, gonad-intact Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice displayed hyperinsulinemia with normal glycemia. In addition, estrogen replacement failed to lower blood glucose/insulin or to improve glucose tolerance in mutant Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre females. These phenotypes in insulin sensitivity were further confirmed in experiments employing the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp. Consistent with earlier reports (54), we showed that estrogen replacement in control females improved the whole-body insulin sensitivity, which was accompanied with both decreased EndoRa (largely reflecting hepatic glucose production) and enhanced Rd (reflecting glucose disposal primarily in the muscle and adipose tissue) during the clamp. Interestingly, genetic inhibition of PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons (in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice) significantly attenuated estrogenic effects on the whole-body insulin sensitivity and completely blocked responses in hepatic glucose production during the clamp. Together, these results indicate that PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons is required to mediate estrogenic actions to improve insulin sensitivity primarily in the liver, which contributes to the maintenance of the whole-body insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis. Notably, PI3K in POMC progenitor neurons is not required to mediate estrogenic actions on glucose disposal, as estrogen replacement still appeared to enhance glucose disposal in Pik3caf/f/POMC-Cre female mice. We speculate that other ERα-expressing cells (eg, in the muscle and fat) or other intracellular signaling pathways may be responsible for estrogenic effects on glucose disposal.

PI3K-downstream mechanisms

The downstream events of PI3K that mediate estrogenic effects on feeding and glucose balance are not clear. One possibility is that activation of PI3K leads to increased POMC neural firing. Supporting this possibility, we observed that a puff application of PPT rapidly stimulated POMC neurons in a PI3K-dependent manner. Similarly, 17β-estradiol has been shown to increase the excitability of POMC neurons by desensitizing γ-aminobutyric acid type B receptors (11). Interestingly, these effects of 17β-estradiol are also blocked by PI3K blockers (11). In addition, it has been shown that activated PI3K in POMC neurons enhances phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate content to inhibit the ATP-sensitive potassium channel, which leads to depolarization of POMC neurons (59). Although this PI3K-phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-ATP-sensitive potassium channel cascade has been shown to mediate leptin effects on POMC neurons (59), its role in estrogenic actions remains to be examined.

Notably, we showed that central administration of PPT in OVX female mice induced a significant nuclear exclusion of the PI3K-downstream transcription factor, FoxO1, specifically in POMC progenitor neurons. Although these effects are modest compared with those of insulin as reported previously (16), these results raise the possibility that estrogens act through the PI3K-FoxO1 pathway in POMC progenitor neurons to regulate feeding and/or glucose homeostasis. Supporting this possibility, selective deletion of FoxO1 in POMC progenitor neurons leads to decreased food intake and body weight in mice (60). Thus, our findings imply that regulation of FoxO1 nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling and its downstream targets in POMC progenitor neurons may be partly responsible for mediating estrogenic effects on feeding and glucose balance.

Importantly, we found that in the presence of wortmannin, PPT still depolarized a small portion of POMC neurons (3/24 in the absence of TTX or 3/13 in the presence of TTX). Such findings suggest that other non-PI3K intracellular signals may contribute to estrogenic actions at least in a portion of POMC neurons. In fact, it has been recently reported that microinjections of 17β-estradiol directly into the VMH of rat brains inhibit the AMP-activated protein (AMPK) in the VMH, and that inhibited AMPK activity in VMH neurons mediates estrogenic actions to stimulate energy expenditure in female rats (30). Interestingly, microinjections of 17β-estradiol directly into the ARH do not alter AMPK activity (30), suggesting that intracellular mechanisms in each ERα population may be distinct.

It is worth mentioning that we chose to delete p110α, but not the other PI3K catalytic subunit (p110β), because we found that loss of p110α was sufficient to block one PI3K-downstream signaling event, the FoxO1 nuclear exclusion. However, one cannot rule out the possibility that other PI3K-downstream signals, especially those mediated through p110β, may mediate a portion of estrogenic actions. Indeed, it has been reported that p110β in POMC neurons plays a more predominant role than p110α in the regulation of body weight balance (29). Thus, the physiological relevance of p110β in estrogenic actions on feeding and glucose balance remains to be elucidated.

In summary, we showed that ERα in POMC progenitor neurons is functionally coupled to the PI3K pathways. This ERα-PI3K cascade mediates estrogenic actions to activate POMC neural activities, and is partly required for the regulation of feeding behavior and insulin sensitivity in female mice. These results provided mechanistic insights regarding where and how estrogens act to prevent overeating and to improve insulin sensitivity and glucose balance, and therefore identified the ERα-PI3K cascade in POMC progenitor neurons as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of obesity and/or diabetes, at least in women.

Acknowledgments

We thank the expert assistance of Mr Firoz Vohra and the MMRU Core Director and Dr Marta Fiorotto.

Author contributions: L.Z. was involved in experimental design and most of procedure, data acquisition and analysis, and writing the manuscript; P.X. assisted in all surgical procedures; X.C. performed electrophysiological recordings; Y.Y. and A.H. assisted in coimmunoprecipitation Western blotting, and PCR experiments; Y.Xi., K.S., X.Y., F.Z., H.D., C.W., and C.Y. assisted in production of study mice and genotyping; P.S. performed euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamps; S.A.K. generated and provided the Esr1f/f mouse line; J.Z. generated and provided the Pik3caf/f mouse line; M.F. generated and provided the Rosa26-FoxO1GFP mouse line; Q.T., D.J.C., and L.C. were involved in study design and writing the manuscript; Y.Xu is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01DK093587, R01DK101379, R00DK085330, and P30 DK079638-03 (to Y.Xu); P01 DK088761 (to D.J.C.); T32CA059268 (to S.A.K.); R01DK092605 (to Q.T.); and HL051586/DK105527 (to L.C.); the US Department of Agriculture Agriculture Research Service Award 6250-51000-055 (to Y.Xu); the American Diabetes Association (Y.Xu); an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship (P.X.), an American Heart Association National Scientist Development grant (Q.T.); and the National Natural Science Foundation of China Award 81200623 (to L.Z.). The hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp study was performed in the Mouse Metabolism Core at the Diabetes Research Center, Baylor College of Medicine, which is supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant P30 DK079638. Measurements of body composition and energy expenditure were performed in the Mouse Metabolic Research Unit at the USDA/ARS Children's Nutrition Research Center, Baylor College of Medicine, which is supported by funds from the USDA ARS.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AgRP

- agouti-related peptide

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein

- ARH

- arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- E

- 17β-estradiol

- E-M

- estrous-metestrous

- EndoRa

- endogenous glucose appearance rate

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- FoxO1

- forkhead box O1

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- GIR

- glucose infusion rate

- i.c.v.

- intracerebroventricular

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- N/T

- nuclear to total

- NTS

- nucleus of the solitary tract

- OVX

- ovariectomy

- P-E

- proestrous-estrous

- PI3K

- phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase

- POMC

- proopiomelanocortin

- PPT

- propyl pyrazole triol

- Rd

- disposal rate

- TTX

- tetrodotoxin

- V

- vehicle

- VMH

- ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus.

References

- 1. Riant E, Waget A, Cogo H, Arnal JF, Burcelin R, Gourdy P. Estrogens protect against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2109–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wallen WJ, Belanger MP, Wittnich C. Sex hormones and the selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen modulate weekly body weights and food intakes in adolescent and adult rats. J Nutr. 2001;131:2351–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gao Q, Mezei G, Nie Y, et al. Anorectic estrogen mimics leptin's effect on the rewiring of melanocortin cells and Stat3 signaling in obese animals. Nat Med. 2007;13:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ogawa S, Chan J, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Estrogen increases locomotor activity in mice through estrogen receptor α: specificity for the type of activity. Endocrinology. 2003;144:230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bryzgalova G, Gao H, Ahren B, et al. Evidence that oestrogen receptor-α plays an important role in the regulation of glucose homeostasis in mice: insulin sensitivity in the liver. Diabetologia. 2006;49:588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heine PA, Taylor JA, Iwamoto GA, Lubahn DB, Cooke PS. Increased adipose tissue in male and female estrogen receptor-α knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12729–12734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xu Y, Nedungadi TP, Zhu L, et al. Distinct hypothalamic neurons mediate estrogenic effects on energy homeostasis and reproduction. Cell Metab. 2011;14:453–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wagner JD, Thomas MJ, Williams JK, Zhang L, Greaves KA, Cefalu WT. Insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular risk factors in ovariectomized monkeys with estradiol alone or combined with nomegestrol acetate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:896–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumagai S, Holmäng A, Björntorp P. The effects of oestrogen and progesterone on insulin sensitivity in female rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1993;149:91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith EP, Boyd J, Frank GR, et al. Estrogen resistance caused by a mutation in the estrogen-receptor gene in a man. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1056–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malyala A, Zhang C, Bryant DN, Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK. PI3K signaling effects in hypothalamic neurons mediated by estrogen. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:895–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hill JW, Xu Y, Preitner F, et al. Phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase signaling in hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons contributes to the regulation of glucose homeostasis. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4874–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Balthasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, et al. Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2004;42:983–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feng Y, Manka D, Wagner KU, Khan SA. Estrogen receptor-α expression in the mammary epithelium is required for ductal and alveolar morphogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14718–14723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhao JJ, Cheng H, Jia S, et al. The p110α isoform of PI3K is essential for proper growth factor signaling and oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16296–16300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fukuda M, Jones JE, Olson D, et al. Monitoring FoxO1 localization in chemically identified neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13640–13648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parton LE, Ye CP, Coppari R, et al. Glucose sensing by POMC neurons regulates glucose homeostasis and is impaired in obesity. Nature. 2007;449:228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu L, Yang Y, Xu P, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 mediates estrogenic actions to prevent body weight gain in female mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:150–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saha PK, Reddy VT, Konopleva M, Andreeff M, Chan L. The triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic-acid methyl ester has potent anti-diabetic effects in diet-induced diabetic mice and Lepr(db/db) mice. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40581–40592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim JK, Michael MD, Previs SF, et al. Redistribution of substrates to adipose tissue promotes obesity in mice with selective insulin resistance in muscle. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1791–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu Y, Hill JW, Fukuda M, et al. PI3K signaling in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus is required for normal energy homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2010;12:88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fukuda M, Williams KW, Gautron L, Elmquist JK. Induction of leptin resistance by activation of cAMP-Epac signaling. Cell Metab. 2011;13:331–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hill JW, Williams KW, Ye C, et al. Acute effects of leptin require PI3K signaling in hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1796–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang G, Drake CT, Rozenblit M, et al. Evidence that estrogen directly and indirectly modulates C1 adrenergic bulbospinal neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Brain Res. 2006;1094:163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ren H, Orozco IJ, Su Y, et al. FoxO1 target Gpr17 activates AgRP neurons to regulate food intake. Cell. 2012;149:1314–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pinto S, Roseberry AG, Liu H, et al. Rapid rewiring of arcuate nucleus feeding circuits by leptin. Science. 2004;304:110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Merlo S, Frasca G, Canonico PL, Sortino MA. Differential involvement of estrogen receptor α and estrogen receptor β in the healing promoting effect of estrogen in human keratinocytes. J Endocrinol. 2009;200:189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stauffer SR, Coletta CJ, Tedesco R, et al. Pyrazole ligands: structure-affinity/activity relationships and estrogen receptor-α-selective agonists. J Med Chem. 2000;43:4934–4947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Al-Qassab H, Smith MA, Irvine EE, et al. Dominant role of the p110β isoform of PI3K over p110α in energy homeostasis regulation by POMC and AgRP neurons. Cell Metab. 2009;10:343–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martínez de Morentin PB, González-García I, Martins L, et al. Estradiol regulates brown adipose tissue thermogenesis via hypothalamic AMPK. Cell Metab. 2014;20:41–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kau TR, Schroeder F, Ramaswamy S, et al. A chemical genetic screen identifies inhibitors of regulated nuclear export of a Forkhead transcription factor in PTEN-deficient tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:463–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Olofsson LE, Pierce AA, Xu AW. Functional requirement of AgRP and NPY neurons in ovarian cycle-dependent regulation of food intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15932–15937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Asarian L, Geary N. Cyclic estradiol treatment normalizes body weight and restores physiological patterns of spontaneous feeding and sexual receptivity in ovariectomized rats. Horm Behav. 2002;42:461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Asarian L, Geary N. Modulation of appetite by gonadal steroid hormones. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:1251–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lissner L, Stevens J, Levitsky DA, Rasmussen KM, Strupp BJ. Variation in energy intake during the menstrual cycle: implications for food-intake research. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48:956–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Finan B, Yang B, Ottaway N, et al. Targeted estrogen delivery reverses the metabolic syndrome. Nat Med. 2012;18:1847–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Asarian L, Geary N. Estradiol enhances cholecystokinin-dependent lipid-induced satiation and activates estrogen receptor-α-expressing cells in the nucleus tractus solitarius of ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5656–5666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]