Abstract

The highly enantioselective asymmetric allylic alkylation of Morita–Baylis–Hillman carbonates with anthrones is presented. The reaction is simply catalyzed by cinchona alkaloid derivatives affording the final alkylated products in good yields and excellent enantioselectivities.

Asymmetric allylic substitution has been one of the most important tools in organic chemistry since its discovery by Tsuji and Trost in the early 70 s1,2. The versatility, chemical scope, functional group tolerance, predictability and often high stereoselectivities associated with this process make it an indispensable tool in organic synthesis. However, recently Green Chemistry has become one of the major focus in order to develop new reactions. Concepts like atom economy or sustainability have become new paradigms for a new generation of chemists. For this reason, one of the common approaches to Green Chemistry is to avoid the use of transition metals such as Pd, Rh, etc. Organocatalysis has blossomed since 2000 for this reason, hundreds of new reactions have been tailored under the auspices of Green Chemistry. One of the most intriguing approaches has been the development of a metal-free allylic substitution. The use of Morita-Baylis Hillman acetates or carbonates has been extensively studied as an alternative to the Tsuji-Trost reaction. In the present work, we expand the scope of the organocatalytic allylic substitution by investigating the use of anthrones.

Anthrones, important scaffolds in natural products and medicinal chemistry, are isolated either in free form or as O- or C-glycosides from a wide variety of natural sources (e.g., plants, shrubs) like rhubarb, cassia, cascara sagrada bark, etc3,4,5,6.

From a chemical standpoint, these compounds (or their enol forms) play a central role in anthracene chemistry due to the oxidation of the central ring that affords 9,10-anthraquinones, which are valuable scaffolds of pigments or anticancer agents7,8. Reduction of anthrones gives anthracenes, which are very useful compounds for the synthesis of dyes and optoelectronic materials9,10.

The dimerization of anthrones led to the synthesis of perylenequinone building blocks of hypericin, present in the herbal remedy St. John’s wort11,12,13,14. Finally, 9-oxoanthracene has been used in the determination of sugars. Moreover, many members of the anthrone family have interesting biological properties (e.g., antimicrobials, laxatives, antipsoriatics, telomerase inhibitors or selective antitumor activity)15,16,17,18,19.

Anthrone scaffolds can be synthesized by two basic strategies: Friedel-Crafts cyclization of o-benzylbenzoic acids or partial reduction of 9,10-anthraquinones. Several groups (Tamura, Cameron, Baldwin, Rodrigo, Snieckus) made fundamental contributions by using anthrones primarily in the synthesis of anthracyclinones, aglycones of the clinically important compound class anthracyclines20,21. Functionalization at C-10 commonly requires deprotonation with a base, which affords racemic anthrones22.

Despite the importance of anthrone moieties in medicinal chemistry, their asymmetric synthesis has not been extensively studied. Only few examples of asymmetric reactions have been reported. For example, anthrones usually behave as reactive dienes, which could react with a variety of dienophiles in the presence of a chiral base in aprotic solvents, reported for the first time by Rickborn23,24.

In previous years, several research groups have focused their attention on the development of asymmetric Diels-Alder reactions with anthrones by using several catalytic systems. Building upon Rickborn’s results, Riant and Kagan investigated the effect of chiral bases in the Diels-Alder reaction between anthrones and maleimides finding that quinine or prolinol were able to catalyze the reaction with moderate enantioselectivities25,26. Later on, Yamamoto27,28 reported the use of C2-chiral 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)pyrrolidines as catalysts and Tan and coworkers reported an extremely nice and efficient Diels-Alder reaction between anthrones and maleimides catalyzed by chiral bicyclic guanidines in both examples with excellent results29.

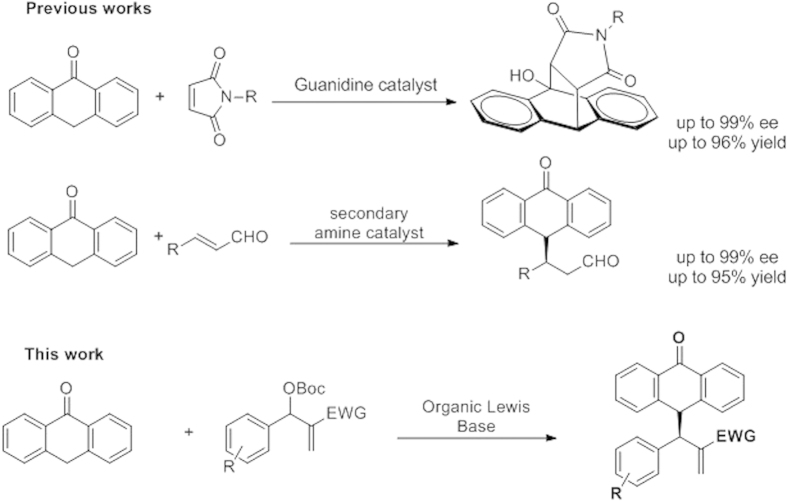

Less explored chemistry is the use of anthrones as nucleophiles in Michael addition. Shi and coworkers30 and our research group have reported the organocatalytic addition of anthrones to nitrostyrenes and to enals, respectively, with good results (Fig. 1)31,32,33.

Figure 1. Reactions with Anthrones.

Following our quest for the development of new methodologies for the synthesis of new three-dimensional scaffolds with possible applications in the pharmaceutical or agrochemical industries, and spurred on by our previous results, we envisioned that anthrones are an often missed privileged structure that could lead to very interesting structures.

Therefore, the development of efficient methods for the asymmetric synthesis of anthrones appears to be a worthy objective. As stated before, only a few examples of asymmetric reactions of anthrones or its derivatives have been reported, and most of them deal with base-catalyzed Diels-Alder reactions or Michael additions to electron-poor allenes.

In the light of these precedents and given our interest in the development of new methodologies for asymmetric organocatalysis based on our previous experience in MBH carbonates34,35,36, we decided to explore the reactivity of anthrones in organocatalyzed allylic substitutions. The reaction undergoes an SN2’-SN2’ Lewis-base-catalyzed pathway to render highly functionalized compounds, that are interesting scaffolds for medicinal and agrochemical industries.

Results

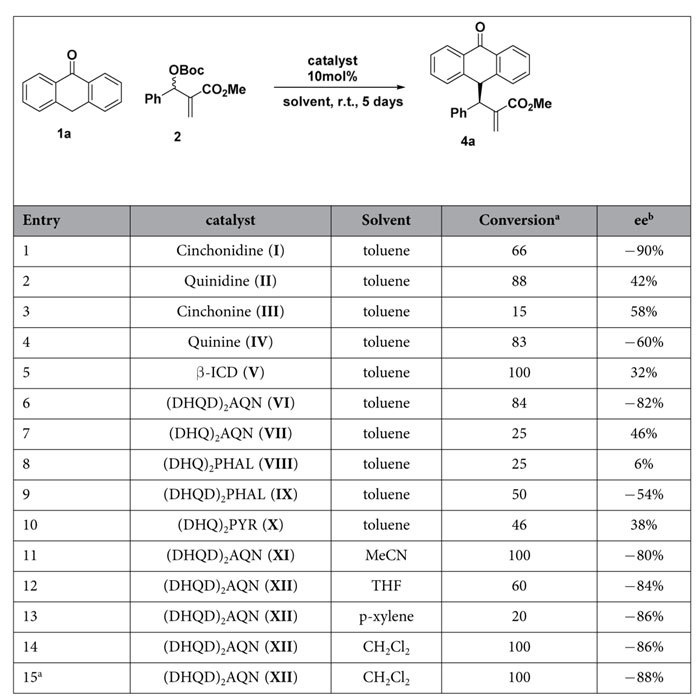

Initial experiments were performed for the quinine-catalyzed reactions of anthrone with MBH carbonate 2a. To our delight, the reaction rendered the desired compound in good conversions and with reasonable stereoselectivities after 1 week. Spurred by this result, we screened the best conditions for the reaction. We tested several Lewis bases, such as quinine, cinchonidine, β-ICD, or Sharpless ligands, at 50 °C or r.t. by using toluene as a solvent. The best catalyst was (DHQD)2AQN, which rendered the desired compound in 84% conversion and 82% ee (Table 1, entry 6). Further optimization of solvent and temperature was carried out. The best conditions were CH2Cl2 as the solvent at 0 °C, which furnished the final compound in full conversion and 88% ee after 5 d (Table 1, entry 15).

Table 1. Screening.

aConversion determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude. bEnantioselectivity determined by chiral HPLC analysis of the crude mixture. cReaction performed at 0 °C.

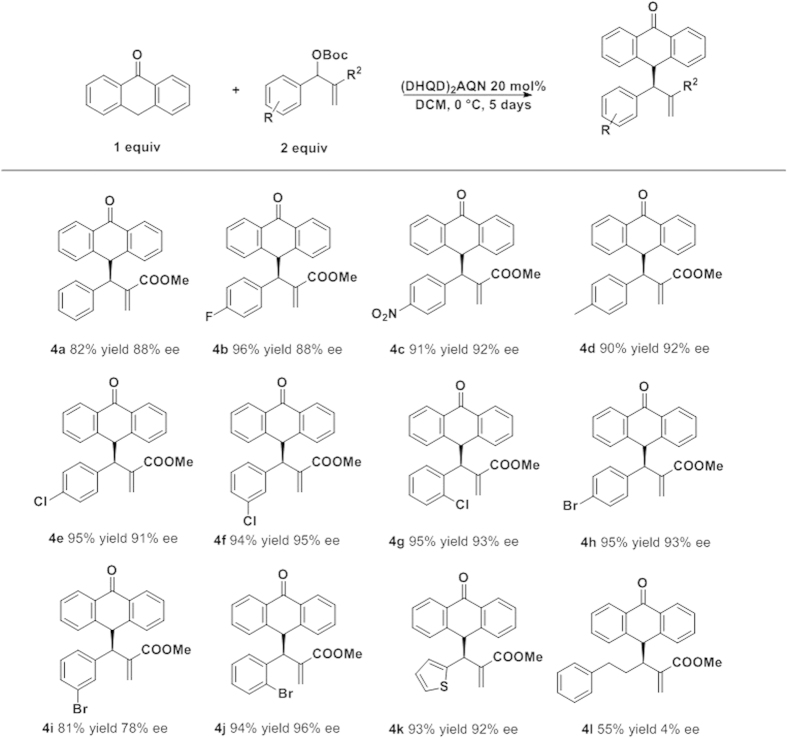

With the best conditions in hand, we proceed to study the scope of the reaction in terms of the MBH carbonate. The reaction works fine with aromatic or heteroaromatic MBH carbonates in excellent yields and enantioselectivities (Fig. 2). The reaction tolerates several substituents on the aromatic ring, for example 4-methyl derivative afforded the final addition product 4d in excellent yield and very good enantioselectivity (90% yield; 92% ee). Halide-substituted MBH carbonates rendered excellent results: 2-Cl, 3-Cl, and 4-Cl substrates gave the addition products 4e–g, respectively, in excellent yields 94–95% and enantioselectivities (91–95%). In case of Br derivatives, the results are very similar (4h, 4j), except for the 3-Br derivative (4i), which gave the worst enantioselectivity (81% yield, 78% ee). We also tested the reaction with a heteroaromatic derivative, which afforded the final compound 4k with excellent yield and enantioselectivity. The only limitation is that the use of aliphatic MBH carbonates renders the final products in good yield but in an almost racemic form (4l).

Figure 2. MBH aryl substituent scope.

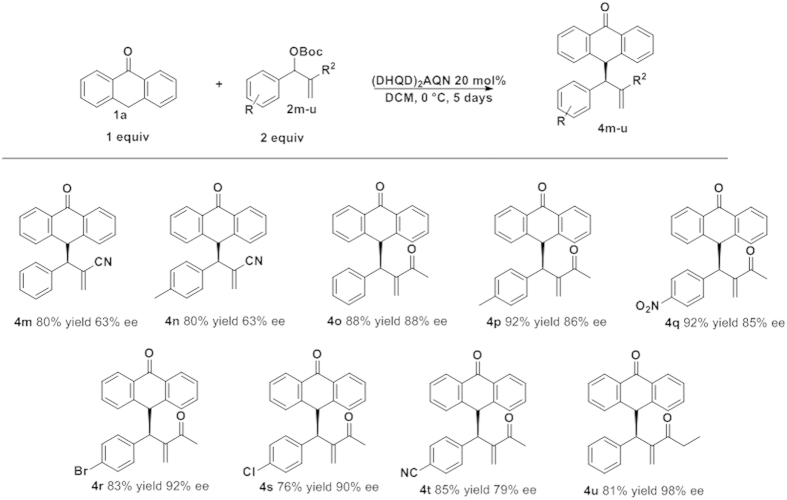

Next, we decided to study the scope of the reaction using MBH carbonates with different electron-withdrawing groups (Fig. 3). First, we tested the reaction with CN as an electron-withdrawing group. However, the results were disappointing: the final compounds were obtained with good yields and moderate enantioselectivities (4m, 4n). Then we turned our attention to ketone derivatives. In general the results obtained were quite good. For example, compound 4o was obtained in very good yield (88%) and ee (88%). The reaction with enones tolerates a wide range of substituents such as halides (4r, 4s), electron-withdrawing (4q, 4t) or electron-donating groups (4p) rendering, in all the examples, the final compounds in good yields (76–92% yield) and enantioselectivities 79–92% ee). Remarkably, when we used the ethylketone derivative (4u) we obtained the product with the highest ee (98% ee) and good yield (81%).

Figure 3. MBH electrowithdrawing substituent scope.

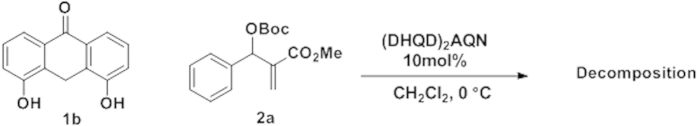

After we studied the scope of the reaction regarding the nature of the MBH carbonate, we proceed to study if we could expand the reaction to dithranol. Unfortunately when dithranol was used as a nucleophile the reaction gave complex mixtures (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Dithranol reaction with MBH carbonates.

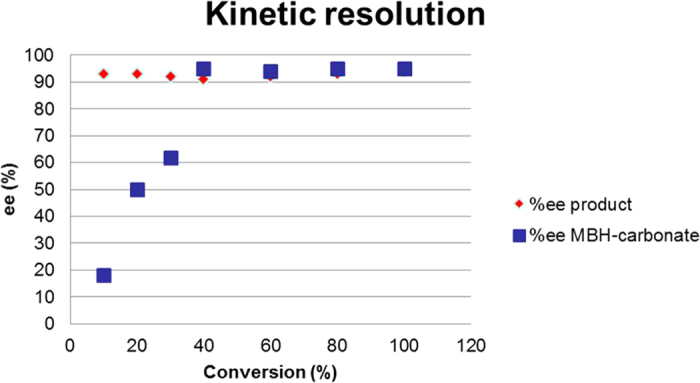

To determine the mechanism of the reaction, we performed several experiments to study the behavior of the starting materials and products during the course of the reaction. We checked the enantioselectivity of the starting material and the final product at different stages to derive a plausible mechanism pathway. As shown in Fig. 5, the enantioselectivity of the final compound is independent from the extent of conversion. This data indicates a common diastereopure intermediate in the reaction. However, the starting material increased in enantiopurity with conversion. This behavior indicates a kinetic resolution of the MBH carbonate.

Figure 5. Kinetic studies of the anthrone addition to MBH carbonates.

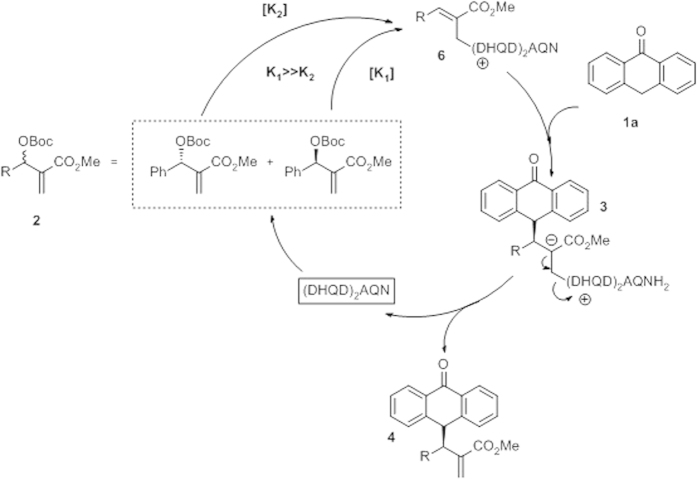

With this data in hand, we propose the following mechanism, which is in accordance with the accepted mechanism in similar reactions (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Proposed mechanism.

First, substrate 2a undergoes a conjugate addition, then elimination of the OBoc group to form CO2 and a tert-butoxide anion provides the Michael acceptor 6. This step is responsible for the observed kinetic resolution of the MBH carbonates. Next, the nucleophile 1a attacks the intermediate 6 to afford 3, and the elimination of the organocatalyst gives the final product 4.

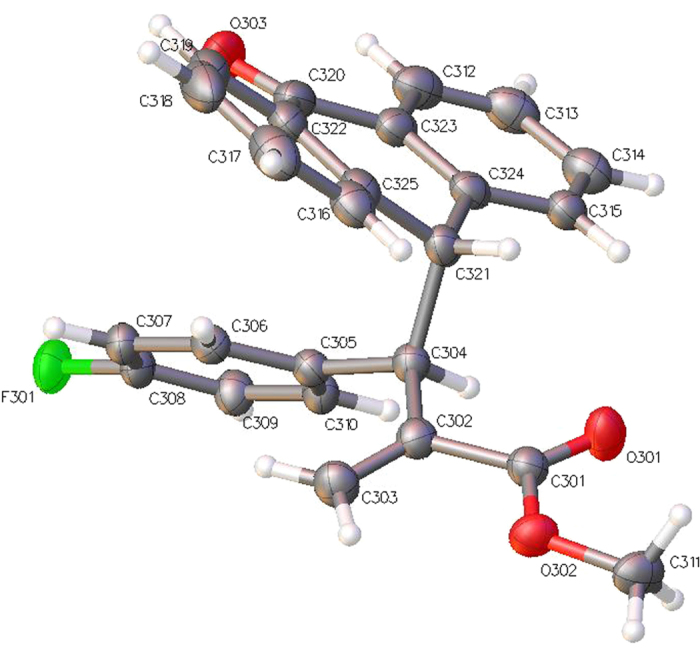

The absolute configuration of compound 4b was ascertained by single-crystal X-ray analysis (Fig. 7). The X-ray crystal structure unambiguously shows that the enantiomer obtained from the reaction with (DHQD)2AQN has an R configuration.

Figure 7. X-ray structure of compound 4b.

The displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

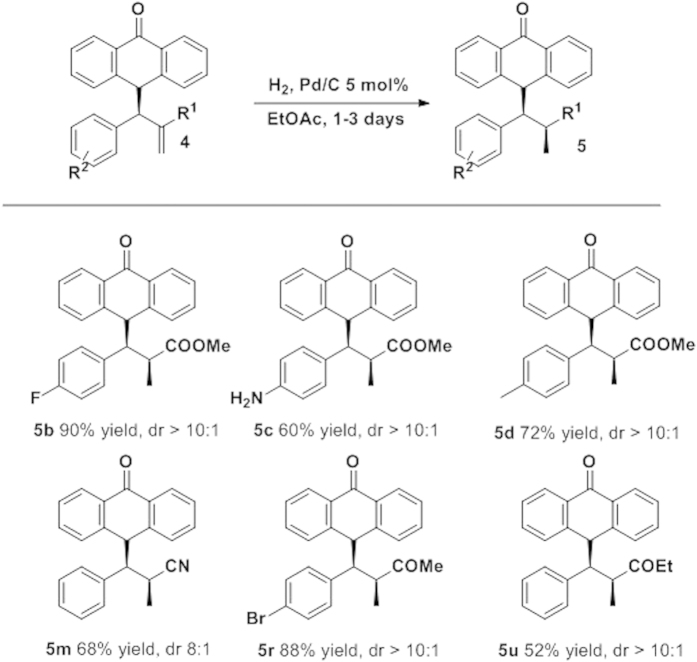

Next, we decided to study the applicability of the reaction by derivatization of compounds 4. The reduction of the double bond was achieved by treatment of compounds 4 with Pd over H2, affording the hydrogenated compounds in excellent yields and excellent to good diastereoselectivities (Fig. 8). As it is shown in Fig. 8, in all the compounds the hydrogenation renders the final products in excellent diastereoselectivities. Interestingly, the carbonyl group of the anthrone remains unreduced. Only in the example 5c a side reaction took place reducing the nitro group to amine. Remarkably the reaction shows a good group tolerance including halogens (5b,5r), cyano derivatives (5m) and ketones (5r and 5u) giving the final reduced products as almost diastereopure and with moderate to good yields (52–90%).

Figure 8. Hydrogenation of compounds 4 of the resulting adducts.

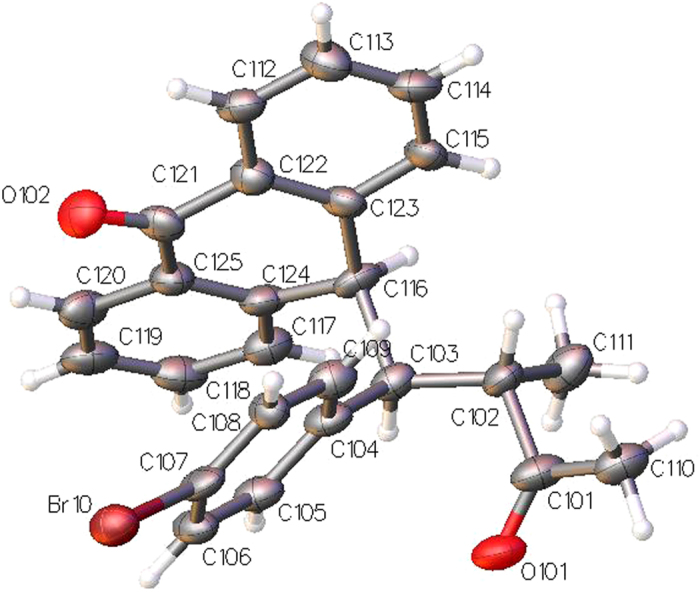

The relative configuration of compound 5r was ascertained by single-crystal X-ray analysis (Fig. 9). The X-ray crystal structure unambiguously shows that the diastereomer obtained from the hydrogenation of 4r has an (S, S) absolute configuration.

Figure 9. X-ray structure of compound 5r.

The displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Methods

General Procedure for the racemic addition of anthrones to MBH carbonates: to a solution of anthrone (1equiv, 0.1 mmol) in dichloromethane (0.1 mol/L) was added the appropriate MBH-carbonate (2 equiv, 0.2 mmol) and 1,4-diaza-bicyclo[2.2.2]octane (20 mol%, 0.02 mmol).The reaction was stirred for 3 days at 0 °C. The reaction was followed by NMR until the disappearance of starting material. The reaction mixture was purified by column chromatography (mixtures Hexane/EtOAc).

General procedure for the chiral addition of anthrones to MBH carbonates: to a solution of anthrone (1equiv, 0.1 mmol) in dichloromethane (0.1 mol/L) was added the appropriate MBH-carbonate (2 equiv, 0.2 mmol) and (DHQD)2AQN (20 mol%, 0.02 mmol).The reaction was stirred for 5 days at 0 °C. The reaction was followed by NMR until the disappearance of starting material. The reaction mixture was purified by column chromatography (mixtures Hexane/EtOAc).

General procedure for the hydrogenation of products 4: In a 2-neck round-bottom flask (RBF) product 4 (1.0 equiv) was added together with Pd/C (0.05 equiv w/w). EtOAc (1 mL, 0.065 mol/L) was added. The RBF was sealed and flushed twice with Argon. Then the reaction mixture was flushed once with H2. The rubber balloon was refilled with H2 and connected to the RBF. The reaction was monitored by TLC until the reaction completion. The mixture was filtered through Celite, washed with EtOAc and concentrated in vacuo. The mixture was purified by column chromatography (5:1 Hexane:EtOAc) (see Supplementary Information).

Crystal Data for C25H19FO3 (M = 386.40 g/mol) (4b): orthorhombic, space group P212121 (no. 19), a = 11.07781(8) Å, b = 12.29676(10) Å, c = 42.1557(3) Å, V = 5742.50(8) Å3, Z = 12, T = 100(2) K, μ(CuKα) = 0.767 mm-1, Dcalc = 1.341 g/cm3, 77409 reflections measured (4.192° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 137.932°), 10586 unique (Rint = 0.0403, Rsigma = 0.0152) which were used in all calculations. The final R1 was 0.0319 (I > 2σ(I)) and wR2 was 0.0832 (all data). Crystallographic data (excluding structure factors) for the structure 4b have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre with CCDC number 1062129. Copies of the data can be obtained, free of charge, on application to Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK, (fax: +44-(0)1223-336033 or e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Crystal Data for C25H21BrO2 (M = 433.33 g/mol) (5r): orthorhombic, space group C2221 (no. 20), a = 14.1137(4) Å, b = 14.1141(5) Å, c = 39.2592(13) Å, V = 7820.5(4) Å3, Z = 16, T = 100(2) K, μ(CuKα) = 3.001 mm-1, Dcalc = 1.472 g/cm3, 57094 reflections measured (4.502° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 137.968°), 7193 unique (Rint = 0.1076, Rsigma = 0.0386) which were used in all calculations. The final R1 was 0.0663 (I > 2σ(I)) and wR2 was 0.1868 (all data). Crystallographic data (excluding structure factors) for the structure 5r have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre with CCDC number 1403893–1403894. Copies of the data can be obtained, free of charge, on application to Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK, (fax: +44-(0)1223-336033 or e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ceban, V. et al. Expanding the scope of Metal-Free enantioselective allylic substitutions: Anthrones. Sci. Rep. 5, 16886; doi: 10.1038/srep16886 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

V.C., M.M., G.G. and R.R. acknowledge the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) for co-financing the AI-CHEM -Chem project (No. 4061) through the INTERREG IV A France (Channel) - England cross-border cooperation Programme. J.V. thanks GAUK No. 427011. Publication is co-financed by the European Social Fund and the state budget of the Czech Republic (Project CZ.1.07/2.3.00/30.0022) This work was done under the auspices of COST Action CM0905 (ORCA).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions J.V. and R.R. conceived the experiment(s), V.C., J.T., M.M., G.G. and I.G. conducted the experiment(s), V.C., M.M, J.T., J.V. and R.R. analysed the results. M.L. and V.C. did the X-Ray analysis. J.V. and R.R. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Tsuji J., Takahashi H. & Morikawa M. Organic syntheses by means of noble metal and compounds. XVII. Reaction of n-allylpalladium chloride with nucleophiles. Tetrahedron Lett. 4387–4388; 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)71674-1, (1965). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M. & Fullerton. T. J. New synthetic reactions. Allylic alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95, 292–294, 10.1021/ja00782a080, (1973). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dagne E., Bisrat D., Viljoen A. & Van B.-E. Chemistry of Aloe species. Curr. Org. Chem. 4, 1055–1078, 10.2174/1385272003375932 (2000). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.-H., Elangovan A. & Ho T.-I. Structure-Property Relationship sin Conjugated Donor-Acceptor Molecules Based on Cyanoanthracene: Computational and Experimental Studies. J. Org. Chem. 70, 7397–7407, 10.1021/jo051183g (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenn L. et al. Anthrone C-Glucosides from Rheum emodi. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 52, 391–393, 10.1248/cpb.52.391, (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinghorn A. D. et al. Anthrone and Oxanthrone C-Glycosides from Picramnia latifolia Collected in Peru. J. Nat. Prod. 67, 352–356, 10.1021/np030479j, (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C., Lipata F. & Rohr J. The complete gene cluster of the antitumor agent gilvocarcin V and its implication for the biosynthesis of the gilvocarcins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7818–7819, 10.1021/ja034781q, (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiovanni P. C. et al. Mechanism of Mouse Skin Tumor Promotion by Chrysarobin. Cancer Res. 45, 2584–2589, (1985) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao J. V. & Giribabu L. A. et al. Combined Experimental and Computational Investigation of Anthracene Based Sensitizers for DSSC: Comparison of Cyanoacrylic and Malonic Acid Electron Withdrawing Groups onto the TiO2 Anatase (101) Surface. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 20117–20126, 10.1021/jp907498e, (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaura R., Ohnishi-Kameyama M. & Lizawa T. Construction of helical J-aggregates self-assembled from a thymidylic acid appended anthracene dye and DNA as a template. Chem. Eur. J. 15, 3729–3735, 10.1002/chem.200802537, (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezakova L., Psenak M. & Kartnig T. Effect of dianthrones and their precursors from Hypericum perforatum on lipoxygenase activity. Pharmazie 54, 711, (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskovsky P. Hypericin-a new antiviral and antitumor photosensitizer: mechanism of action and interaction with biological macromolecules. Curr. Drug Targets, 3, 55–84, 10.2174/1389450023348091, (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostinis P., Vantieghem A., Merlevede W. & de Witte P. A. M. Hypericin in cancer treatment: more light on the way. Int. J. Bio. Cell Biology 34, 221–241, 10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00126-1, (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer J. J. & Rosensopn J. Chemistry of St. John’s Wort: Hypericin and hyperforin. J. Chem. Ed. 81, 1450–1455, 10.1021/ed081p1450, (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K. & Prinz H. Antipsoriatic Anthrones with Modulated Redox Properties. 4. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Novel 9,10-Dihydro-1,8-dihydroxy-9-oxo-2-anthracenecarboxylic and –hydroxamic Acids. J. Med. Chem. 40, 2780–2787, 10.1021/JM9701785, (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron D. W. & Skene C. E. Synthesis oft he androgen-receptor antagonists (±)-WS9761 A and B. Austr. J. Chem. 49, 617–624, (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.-S. et al. Synthesis and Cytotoxicity of 9-Alkoxy-1,5-dichloroanthracene Derivatives in Murine and Human Cultured Tumor Cells. Arch. Pharm. Med. Chem. 335, 33–38, (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.-S. et al. Studies on anthracenes. 1. Human telomerase inhibition and lipid peroxidation of 9-acyloxy 1,5-dichloroanthracene derivatives. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 49, 969–973, 10.1248/cpb.49.969, (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz H. et al. Novel Benzylidene-9(10H)-anthracenones as Highly Active Antimicrotubule Agents. Synthesis, Antiproliferative Activity, and Inhibition of Tubulin Polymerization. J. Med. Chem. 46, 3382–3394, 10.1021/jm0307685, (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J. E. & Algis A. J. Approaches to the regiospecific synthesis of anthracycline antibiotics. Tetrahedron 38, 3079–3084, 10.1016/0040-4020(82)80196-8, (1982). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J. E. & Bair K. W. The use of directed metalation reactions in the synthesis of unsymmetrical anthrones and anthraquinones. Synthesis of anthracyciclinone precursors. Tetrahedron Lett. 29, 2559–2562, (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Chande M. S., Khanwelkar R. R. & Barve P. A. Synthesis of novel spiro compounds using anthrone and pyrazole-5-thione moieties: a Michael addition approach. J. Chem. Res. 8, 468–471, 10.3184/030823407X237821, (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner M. & Rickborn B. Anthrones as reactive dienes in Diels-Alder reactions. J. Org. Chem. 54, 6–9, 10.1021/jo00262a003, (1989). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner M. & Rickborn B. Base-catalyzed reactions of anthrones with dienophiles. J. Org. Chem. 55, 2662–2672, 10.1021/jo00296a024, (1990). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riant O. & Kagan H. B. Asymmetric Diels-Alder reaction catalysed by chiral bases. Tetrahedron Lett. 30, 7403–7406, 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)70709-X, (1989). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riant O. & Kagan H. B. Asymmetric base-catalyzed cycloaddition between anthrone and some dienophiles. Tetrahedron 50, 4543–4554, 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)89385-6, (1994). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uemae K., Masuda S. & Yamamoto Y. Asymmetric cycloaddition of anthrone and maleimides catalysed by C2-chiral pyrrolidines. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1, 9, 1002–1006, 10.1039/b100961n, (2001). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y. et al. Asymmetric cycloaddition of anthrone with N-substituted maleimides with C2-chiral pyrrolidines. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 8, 101–107, 10.1016/S0957-4166(96)00473-9, (1997). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C.-H. et al. Chiral Bicyclic Guanidine-Catalyzed Enantioselective Reactions of Anthrones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 13692–13693, 10.1021/ja064636n, (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M., Lei Z.-Y., Zhao M.-X. & Shi J.-W. A highly efficient asymmetric Michael addition of anthrone to nitroalkenes with cinchona organocatalysts. Tetrahedron Lett. 48, 5743–5746, 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.06.107, (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alba A.-N., Bravo N., Moyano A. & Rios R. Enantioselective addition of anthrones to α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 50, 3067–3069, 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.04.037, (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moyano A. & Rios R. et al. Bifunctional Thiourea-Catalyzed Asymmetric Addition of Anthrones to Maleimides. Adv. Synth. Catal. 352, 1102–1106, 10.1002/adsc.201000031, (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moyano A. & Rios R. et al. Asymmetric organocatalytic anthrone additions to activated alkenes. Tetrahedron 67, 2513–2529, 10.1016/j.tet.2011.02.032, (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rios R. et al. Synergistic catalysis: highly diastereoselective benzoxazole addition to Morita-Baylis-Hillman carbonates. Chem. Commun. 50, 7447–7450, 10.1039/c4cc00728j, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyano A. & Rios R. et al. Enantioselective organocatalytic asymmetric allylic alkylation. Bis(phenylsulfonyl)mathane addition to MBH carbonates. Org. Biomol Chem. 9, 7986–7989, 10.1039/c1ob06308a, (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios R. Organocatalytic enantioselective methodologies using Morita-Baylis-Hillman carbonates and acetates. Catal. Sci. Tech. 2, 267–278, 10.1039/C1CY00387A, (2012). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.