Abstract

A fluorescent reagentless biosensor for ATP has been developed, based on malonyl-coenzyme A synthetase from Rhodopseudomonas palustris as the protein scaffold and recognition element. Two 5-iodoacetamidotetramethylrhodamines were covalently bound to this protein to provide the readout. This adduct couples ATP binding to a 3.7-fold increase in fluorescence intensity with excitation at 553 nm and emission at 575 nm. It measures ATP concentrations with micromolar sensitivity and is highly selective for ATP relative to ADP. Its ability to monitor enzymatic ATP production or depletion was demonstrated in steady-state kinetic assays in which ATP is a product or substrate, respectively.

ATP is an intracellular energy source, involved in many cellular processes, including active transport, cell motility, and biosynthesis. It is also an important extracellular signaling agent in neurotransmission1 and inflammation.2 ATP is generated through several pathways such as glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation. This makes it an important assay target, and monitoring ATP production is widely used to measure enzyme activity in biochemical and cell-based applications.

Here, the design, development, and characterization of a fluorescent, reagentless biosensor for ATP are described. Such biosensors for a target molecule are single molecular species that consist minimally of a recognition element and a reporter.3 In this case, the recognition element is a protein that interacts with the target analyte, ATP, namely malonyl-coenzyme A synthetase from Rhodopseudomonas palustris (RpMatB). This protein is coupled covalently to the reporter fluorophore(s) to give a fluorescence change on ATP binding and thereby report on the ATP concentration in the medium.

RpMatB was chosen as the recognition element because of several properties, including high expression, good stability, and because it has high affinity and selectivity for ATP. Crystal structures4 show an ATP-dependent conformational change, described in detail below. This was used to design RpMatB variants with cysteine point mutations of surface residues in order to be able to incorporate thiol-reactive fluorophores at specific locations.

RpMatB belongs to the AMP-forming acyl-coenzyme A synthetase family (PF00501)5 and the ANL superfamily, which contains acyl- and aryl-coenzyme A synthetases, the adenylation domains of nonribosomal peptide synthetases, and firefly luciferase.6 RpMatB catalyzes the conversion of malonate and coenzyme A to malonyl-coenzyme A via a ping-pong mechanism, consuming ATP through a malonyl-AMP intermediate. Its other products are AMP and pyrophosphate.

Two different design strategies were tried to create a fluorescence signal to report ATP concentration in the medium. One strategy was based on the introduction of a single, environmentally sensitive fluorophore. The other relied on reversible stacked dimer formation between a pair of identical fluorophores, more particularly two tetramethylrhodamines. Both strategies have been used previously to develop reagentless biosensors. Examples include an inorganic phosphate biosensor based on the E. coli phosphate binding protein,7,8 a single-stranded DNA biosensor based on the E. coli single stranded DNA binding protein,9 and an ADP biosensor based on the bacterial actin homologue, ParM.10,11

The final form of the ATP biosensor is an adduct of RpMatB and two tetramethylrhodamines, which responds specifically to ATP with a maximum 3.7-fold fluorescence increase. Its sensitivity lies in the micromolar range, and its ability to monitor ATP production or consumption was demonstrated with steady-state kinetic assays to measure time courses, in which ATP is a product or substrate, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Design of the Biosensor Based on RpMatB

A suitable candidate for the protein recognition element of an ATP biosensor was found by comparison of ligand-bound protein structures of bacterial proteins with their corresponding ligand-free structures, as described in the Methods. If that comparison revealed a significant conformational change upon ligand binding, the protein was seen as a potential candidate for biosensor development. Such conformational changes can be harnessed to transduce ligand binding to a fluorescence change of a fluorophore reporter, local to that region of the protein so that it responds to the change in structural environment. Functional parameters, affinity and selectivity for ATP, were then considered, together with information on known mutations that block enzymatic activity.

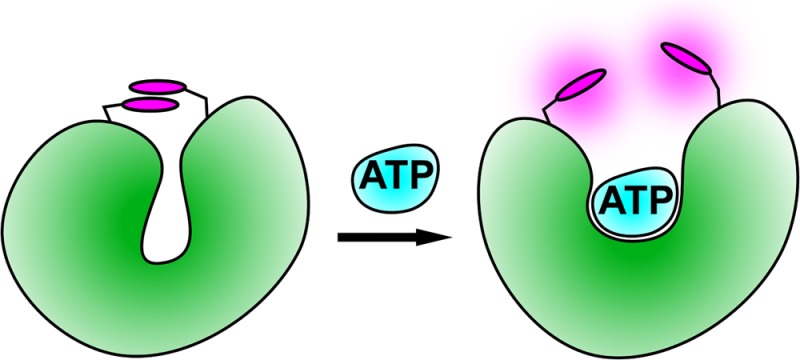

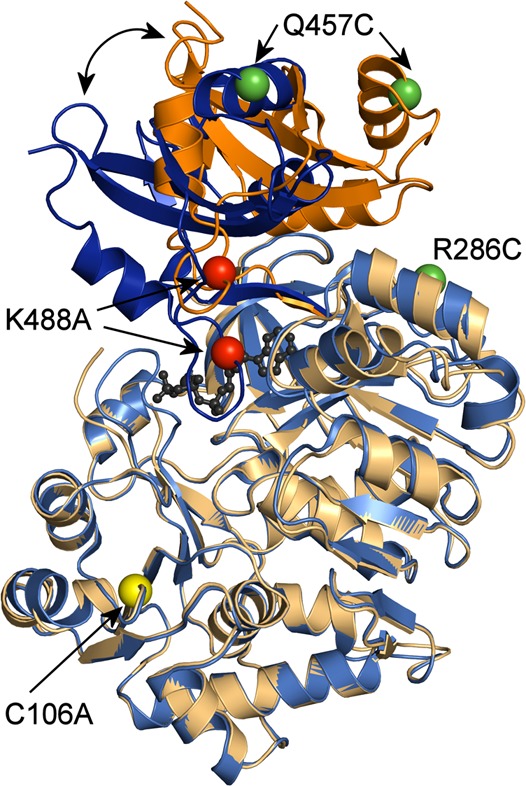

Following this analysis, RpMatB was chosen as the most suitable candidate for development of a reagentless ATP biosensor. RpMatB has been crystallized in two conformations, that is, an open form of the apoprotein and a closed form with MgATP bound4 (Figure 1). There is a significant conformational change upon MgATP binding,4 and in particular, the C-terminal “lid” domain rotates ∼20° toward the N-terminal domain closing the active site cleft.

Figure 1.

C-terminal domain rotation upon MgATP binding and position of mutations in RpMatB. Overlaid structures of RpMatB in the absence (orange) and presence (blue) of ATP,4 showing the movement of the C-terminal (lid) domain in dark colors. The N-terminal domains (amino acids 1–399) are in light colors, and MgATP is shown in black. The positions of mutations are shown as spheres. For clarity, the positions of mutations C106A and R286C are only shown in the apo conformation.

Cysteine mutations were introduced as sites for fluorophore labeling onto a background of the C106A and K488A mutations in the wild-type protein. RpMatB with the K488A active site mutation does not catalyze the adenylation half-reaction of ATP and malonate to malonyl-AMP and pyrophosphate.4 It would be expected to bind ATP but not catalyze any reaction. C106 in the wild-type protein (Figure 1) is situated in the N-terminal domain, distant from the active site but partially solvent accessible. Having shown that there is a low, but significant, degree of background labeling (6%) at this position with a maleimide, MDCC (7-diethylamino-3-((((2-maleimidyl)ethyl)amino)carbonyl)coumarin), C106 was mutated to alanine. Several variants were designed and prepared with either one or two cysteine residues introduced in order to label (His6/C106A/K488A)RpMatB with either one diethylaminocoumarin or two tetramethylrhodamines, respectively.

After examination of the ligand-bound and ligand-free RpMatB structures, sites for diethylaminocoumarin labeling were chosen, situated around the ligand-binding pocket on the C-terminal lobe, so that the fluorophore might experience an environmental change when MgATP binds. These labeled variants were tested for the fluorescence change upon ATP binding in the presence of Mg2+ (Table S1).

Sites for tetramethylrhodamine labeling were chosen so that stacking of the two fluorophores might be possible in the apo conformation and that dissociation of these stacked tetramethylrhodamines could occur on the conformational change with MgATP binding. In particular, positions were chosen with a suitable distance (∼1.5–2.0 nm) and orientation between them in the apo conformation. In addition, the distance and orientation between the chosen positions changed when MgATP binds. Following labeling with tetramethylrhodamines, results from seven different combinations are shown in Table S1.

Not all the rationally designed RpMatB mutants had an ATP-dependent fluorescence change, probably due to a combination of several factors. First, introducing a fluorophore might have an effect on protein flexibility and therefore on the conformational change upon ligand binding, either because of interaction with amino acids or because of interactions between fluorophores. Second, while comparisons between apo and ligand-bound structures indicate that most of the ANL superfamily members undergo a conformational change after binding, the interdomain geometry in apo structures is less conserved than in ligand-bound structures (Table S2). In addition, several observations indicate that the C-terminal domain is also more flexible than the N-terminal domain. This is based on the absence of clear C-terminal domain structures observable in some apo structures within the ANL superfamily and the higher average B-factor for the C-terminal domain compared to the N-terminal domain in crystal structures of these proteins (Table S2). So the precise geometry of the apo RpMatB in solution may not correspond to the crystal structure.

Finally, the single fluorophore approach requires changes in interaction between fluorophore and protein on ATP binding, which are more difficult to predict. Although the fluorophore was placed where changes in structure occur, the fact that the fluorophore can rotate around its cysteine means it may not fully experience those changes. In contrast, the positioning of the two rhodamines can be modeled more accurately, as the distance requirements for stacking are clearer for the likely arrangement of the two-ring systems.12,13

The labeled variant with the largest fluorescent increase upon MgATP-binding was (His6/C106A/R286C/Q457C/K488A)RpMatB, labeled with two 5-iodoacetamidotetramethylrhodamines (5-IATR), hereafter referred to as Rho-MatB. Both cysteine labeling positions are well-defined in the apo and MgATP-bound structures, as shown in Figure 1. R286 is in the N-terminal domain and Q457 in the C-terminal domain: the distances between these two α-carbons are 1.96 nm in the apo and 2.66 nm in the MgATP-bound conformation.

Fluorescence and Absorbance Properties of Rho-MatB with ATP

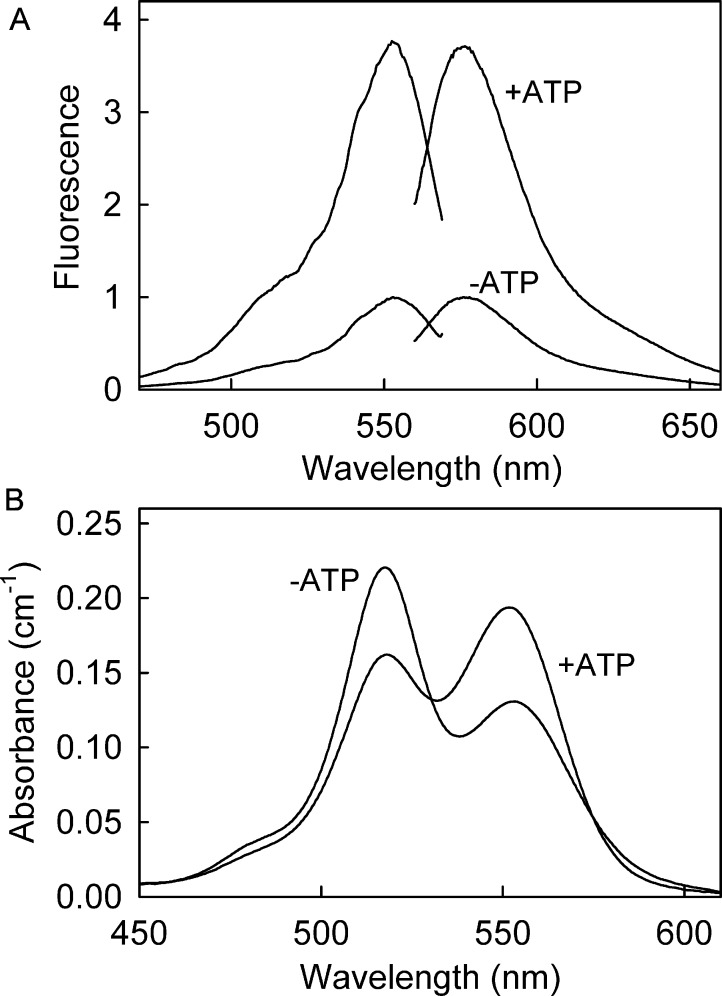

Figure 2A shows fluorescence excitation and emission spectra of Rho-MatB on the addition of ATP. The fluorescence spectra did not change shape or position, but the intensity increased 3.7-fold. The affinity for ATP was determined by measuring the fluorescence at different concentrations of ATP in a solution of Rho-MatB, and the Kd for ATP was 6.4 μM (Figure 3A and Table 1). This is higher than unlabeled RpMatB K488A (0.31 μM),4 possibly due to the extra point mutations and/or the fluorophores.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence and absorbance spectra of Rho-MatB. (A) Fluorescence excitation and emission spectra of 1 μM Rho-MatB in 50 mM Hepes at pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.3 mg mL–1 bovine serum albumin in the absence and the presence of 175 μM ATP. Excitation was at 553 nm for the emission spectra. Emission was measured at 575 nm for the excitation spectra. (B) Absorbance spectra of 1 μM Rho-MatB in the same buffer in the absence and presence of 119 μM ATP.

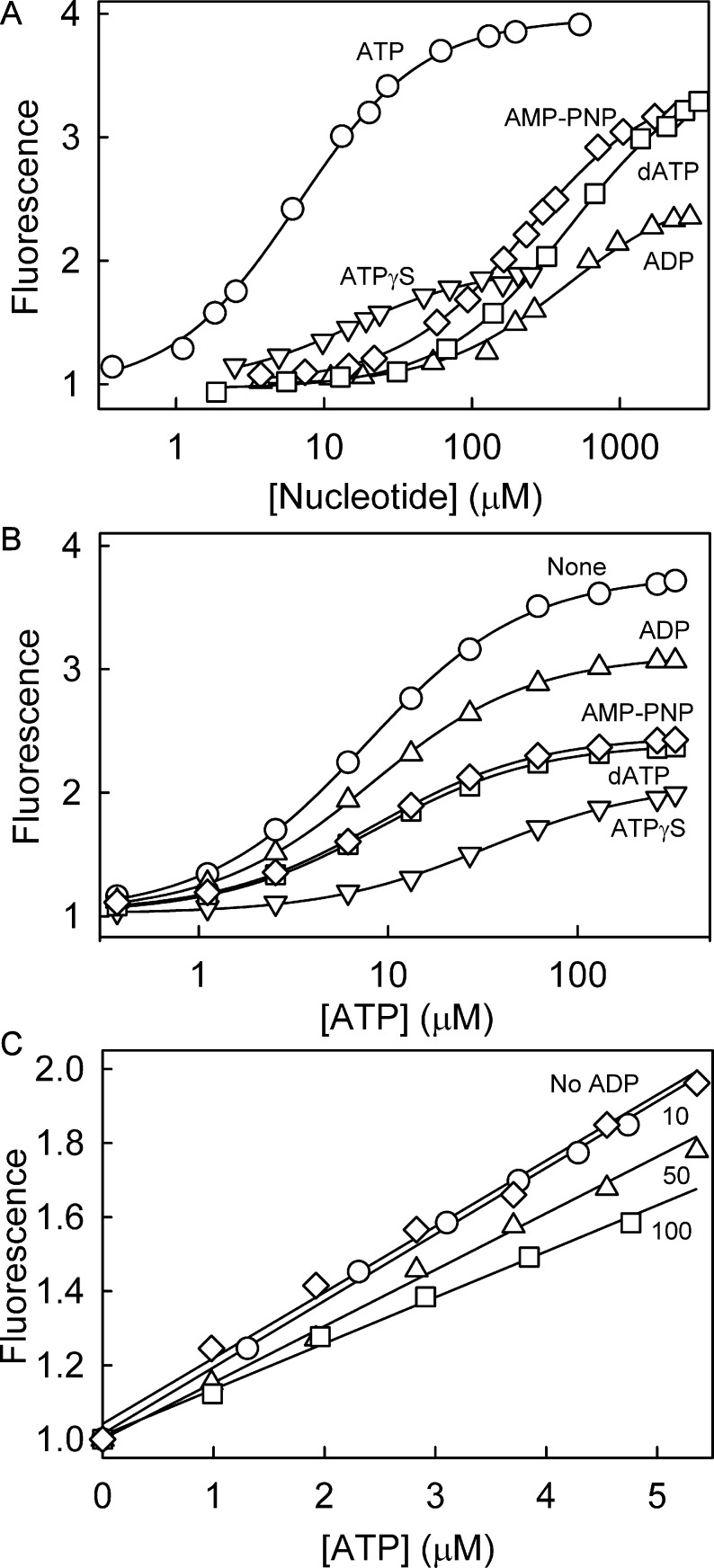

Figure 3.

Nucleotide affinity to Rho-MatB. (A) Titration of ATP (circles), ADP (up triangles), dATP (squares), ATPγS (down triangles), and AMP-PNP (diamonds) to 0.5 μM Rho-MatB in buffer as in Figure 2 at 20 °C. The dissociation constants were obtained using a quadratic binding equation (see Methods) and are listed in Table 1. (B) The effect of different nucleotides on ATP binding. 1 μM Rho-MatB in the absence (circles) and presence of 100 μM ADP, dATP, ATPγS, or AMP-PNP (symbols as above) was titrated with ATP. The apparent dissociation constants for ATP were obtained using the quadratic binding equation. The fitted curves gave the following values for apparent dissociation constant and fluorescence ratio: ADP, 7.7 ± 0.6 μM, 3.0; dATP, 9.1 ± 1.2 μM, 2.3; ATPγS, 38 ± 9 μM, 1.9; AMP-PNP, 8.2 ± 0.4 μM, 2.4. (C) Linearity of response to ATP. 2.5 μM Rho-MatB was titrated with ATP (diamonds). To test the effect of ADP, the fluorescence was measured in the presence of ADP, such that the total nucleotide concentration (ADP + ATP) was constant at 10 μM (circles), 50 μM (triangles), or 100 μM (squares).

Table 1. Fluorescence Changes and Dissociation Constants (Kd) for Binding of ATP and Other Nucleotides to Rho-MatBa.

| nucleotide | F+/F– | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| ATP | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.6 |

| ADP | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 428 ± 50 |

| dATP | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 440 ± 53 |

| ATPγS | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 16.2 ± 0.8 |

| AMP-PNP | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 253 ± 11 |

Absorbance spectra of Rho-MatB were measured for a range of ATP concentrations (Figure 2B). In the absence of nucleotide, the maximum absorbance was at 518 nm with a smaller peak at 553 nm. This is characteristic of tetramethylrhodamine stacking, corresponding qualitatively to the absorbance spectra for other stacked rhodamines.14,15 Binding ATP causes an absorbance decrease at 518 nm and an increase at 553 nm, indicating that nucleotide binding reduces the stacking, as monomeric rhodamine had its larger peak at ∼550 nm. The isosbestic point was at 532 nm.

Affinity of Rho-MatB for Other Nucleotides and Potential Ligands

The fluorescence of Rho-MatB responded to the addition of nucleotides other than ATP. There was an increase in fluorescence intensity upon the addition of ADP, dATP, ATPγS (adenosine 5′-(γ-thio)triphosphate), or AMP-PNP (adenosine 5′-(β,γ-imido)triphosphate), although the changes were smaller than with ATP. Their dissociation constants were determined by measuring the fluorescence at different concentrations of the nucleotide in a solution of Rho-MatB (Figure 3A and Table 1) and were 428 μM, 440 μM, and 253 μM for ADP, dATP, and AMP-PNP, respectively. So these nucleotides bound much more weakly than ATP. The dissociation constant of ATPγS was 16.2 μM, much more similar to ATP.

In contrast, AMP, GDP, and GTP did not significantly affect the fluorescence (Table S3). Natural non-nucleotide substrates of RpMatB, malonate, and coenzyme A, also had no effect and their presence did not inhibit the MgATP-induced fluorescence increase (Table S3). Presumably these do not induce the same conformational change as MgATP binding.

In most biological reactions in which ATP is a product, it is likely to be synthesized from ADP, and consequently, ADP will be present as a substrate in assay solutions, potentially at a much higher concentration than the ATP product. Therefore, it is important that the biosensor discriminates well against ADP, as described above. The effect of ADP on the fluorescence signal change with ATP and the affinity of ATP were also assessed. Titration curves for ATP were obtained in the presence of 100 μM ADP: the apparent Kd for ATP was similar in the absence and presence of ADP, and the response of the biosensor to ATP was only reduced slightly (Figure 3B). In addition, the influence of ATP analogues on ATP affinity was assessed. Titration curves for ATP were obtained in the presence of a fixed concentration of dATP, ATPγS, or AMP-PNP. Only ATPγS influenced the apparent Kd for ATP, increasing it ∼5-fold (Figure 3B).

It simplifies application of a fluorescence biosensor if the response to concentration is approximately linear, and Figure 3C shows this is so for one set of conditions. The fluorescence response to ATP was also measured in the presence of different ADP concentrations but at constant total nucleotide concentration to mimic ADP conversion to ATP. Although the slope decreased with increasing ADP concentration, the fluorescence response to ATP remained linear in the presence of ADP over the same range (Figure 3C).

The Influence of Solution Conditions on the Fluorescent Properties of Rho-MatB

The fluorescence response to ATP was measured in different buffers over a pH range from 6.5 to 9.0 and ionic strengths from 50 to 200 mM (Table S4). Although the size of the fluorescence response changed with solution conditions, there were rather small effects on the Kd for ATP. Mg2+ is required for the fluorescence change, suggesting that MgATP is the species bound (Table S3), as might be expected because Mg2+ is a cofactor for the enzyme. Thus, Rho-MatB can be used as a biosensor for ATP under various pH and salt conditions in the presence of Mg2+.

Binding Kinetics

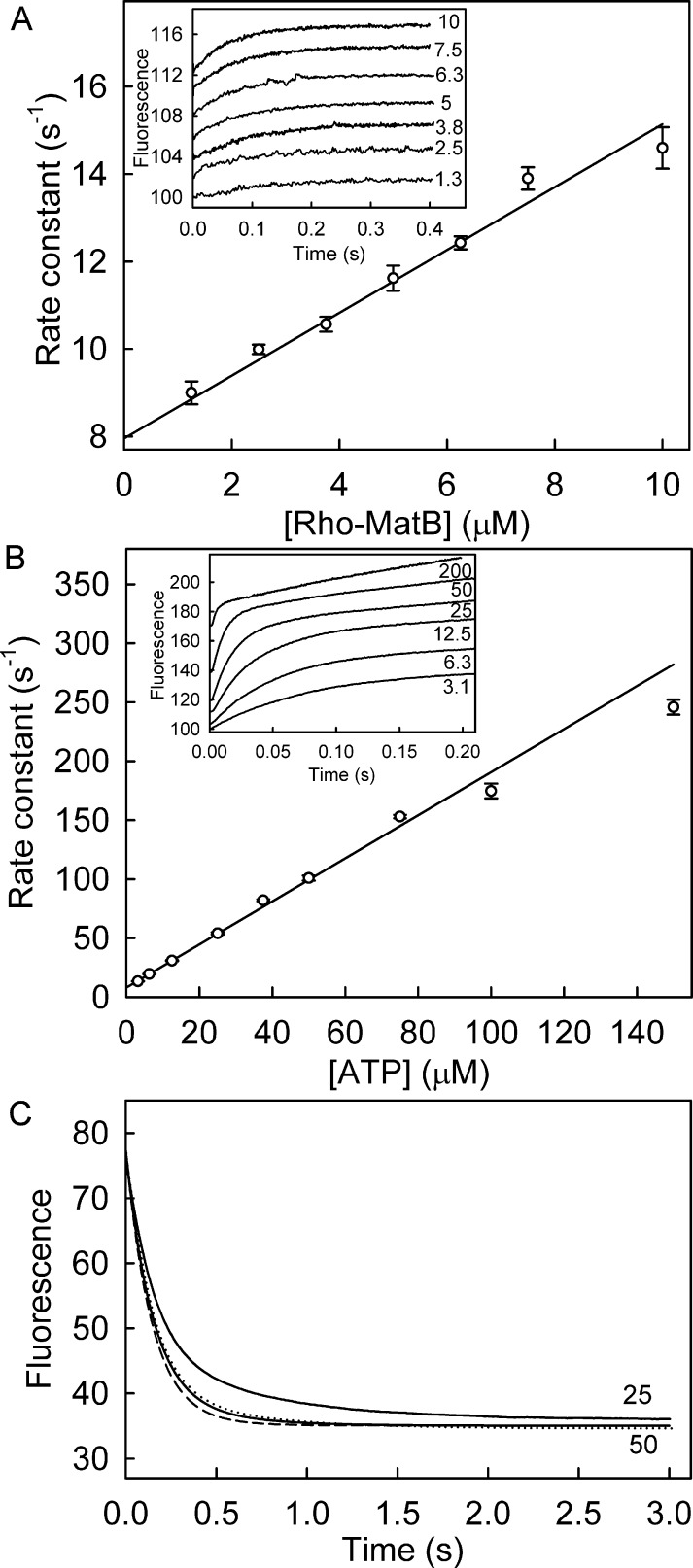

The kinetics of ATP binding were measured by stopped-flow fluorescence in order to assess the range of rates over which Rho-MatB is suitable for real-time measurements. ATP binding was measured with Rho-MatB in large excess over the nucleotide. Rapid mixing produced a monophasic, exponential increase in fluorescence over a range of Rho-MatB concentrations (Figures 4A inset and S1A). The observed rate constants increased linearly with Rho-MatB concentration (Figure 4A), giving an association rate constant of 0.72 μM–1 s–1, and the intercept was 8.0 s–1, presumably the dissociation rate constant.

Figure 4.

Association and dissociation kinetics of Rho-MatB and ATP. (A) Association kinetics under pseudo-first-order conditions over a range of Rho-MatB concentrations (shown as micromolar) in 10-fold excess over ATP at 25 °C in solution conditions as in Figure 2 using a stopped-flow apparatus. Fluorescence time courses (inset) were normalized to 100% for the initial intensity but offset by 2% from each other for clarity and were well fit with a single exponential. Data at 1.3 and 2.5 μM are averages of at least three traces. Fits are shown in Figure S1A. The observed rate constants were plotted against Rho-MatB concentration, and linear regression gave an association rate constant of 0.72 ± 0.03 μM–1 s–1 and an intercept of 7.95 ± 0.18 s–1. (B) Association time course under pseudo-first-order conditions by mixing 0.25 μM Rho-MatB with a large excess of ATP at different micromolar concentrations, as shown (inset). The time courses showed biphasic fluorescence changes. The observed rate constants for the fast phase (kobs; Figure S1B) were plotted against ATP concentration. Linear regression gave an association rate constant of 1.83 ± 0.02 μM–1 s–1, and the intercept was 8.15 ± 0.17 s–1. (C) To determine the dissociation time course, ATP (5 μM) and Rho-MatB (0.25 μM) were premixed to give the complex and then rapidly mixed with 25 μM or 50 μM (His6/C106A/K488A)RpMatB under conditions as above in a stopped-flow apparatus. The dissociation was simulated (dashed line) using the conformational selection mechanism (Figure 5A) and rate constants obtained from global fitting (Table S5), while assuming the association rate constant with the unlabeled MatB trap was the same as with Rho-MatB, but its dissociation constant was 20-fold lower to account for the tighter binding. Note that the small deviation from experimental results may be due to the two conformations of Rho-MatB having slightly different fluorescence intensities: the model assumes they have the same. The dotted line is with fluorescence of Rho-MatB1 13% less than that of Rho-MatB2.

Binding kinetics were also measured by rapidly mixing different concentrations of ATP in large excess with Rho-MatB (Figures 4B inset, S1B and S1C). The time courses of the subsequent fluorescence response were biphasic with the fast phase shown in Figure 4B (inset). The observed rate constant for the fast phase increased linearly with ATP concentration (Figure 4B), giving a slope of 1.8 μM–1 s–1 and an intercept of 8.2 s–1. This phase had somewhat similar kinetics to those with excess Rho-MatB and so presumably represents binding: the slope is the association rate constant; the intercept is the dissociation rate constant. The equilibrium dissociation constant, calculated from these values (4.5 μM), agrees well with the value from equilibrium binding data (Figure 3A and Table 1). The whole time courses fitted well to two exponentials (Figure S1B and S1C, showing different time scales). The observed rate constants for the slow phase were independent of ATP concentration with an average value of 0.88 s–1.

Binding Mechanism

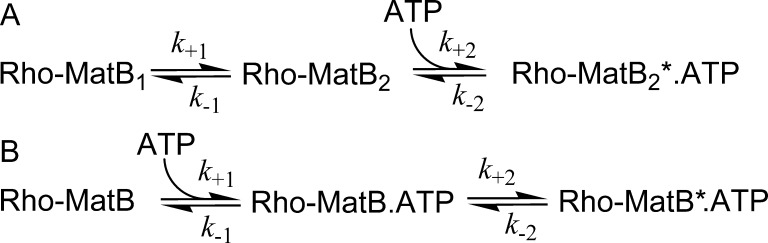

Two alternate two-step binding mechanisms (Figure 5) were considered to account for observed binding kinetics, specifically a single, fast phase with excess Rho-MatB and an additional slow phase with excess ATP. In the first model, a pre-existing conformational equilibrium in the apoprotein was followed by association of ATP to one of the conformations (“conformational selection,” Figure 5A). The second model involves a structural transition that follows ATP-binding (“induced fit,” Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Alternative two-step kinetic mechanisms for ATP binding to Rho-MatB. Rho-MatB and Rho-MatB* represent two different fluorescence states of the protein with Rho-MatB* having the higher fluorescence. (A) Conformational selection model. In the absence of ATP, the protein exists in two conformations, but only Rho-MatB2 can bind ATP. It is assumed that the fluorescence change occurs only on the second step. (B) Induced fit model. Rho-MatB binds ATP, and then the ATP-bound protein goes to the other conformation.

To distinguish between the two schemes, ATP binding kinetics were simulated for different sets of concentrations (Figure S2). While both models gave biphasic kinetics when ATP was in excess, only the conformational selection model showed a single phase with excess protein. In addition, the conformational selection model overall gave qualitatively similar shaped curves to the experimental data. Thus, the conformational selection model provided a minimal mechanism for binding. The true mechanism may be more complex, either with extra steps or fluorescence changes on both steps: the dissociation data (below) give evidence that the latter may occur.

The conformational selection model also suggests a reason for the difference in measured association rate constants with ATP or protein in excess. For the latter, the analysis of measurements with Rho-MatB in excess (Figure 4A) used the total Rho-MatB concentration. Because only a fraction of the protein can bind ATP directly, the true rate constant would be higher and may be more similar to that obtained with ATP in excess. Having concluded that the conformational selection model is the better choice, this was tested further by global fitting the association time courses over a range of concentrations with both ATP and Rho-MatB in excess (FigureS3). This provides a single set of rate constants for both steps of the mechanism, shown in Table S5. These are in reasonable agreement with the rate constants obtained in Figure 4 and could be tested by direct measurement of the dissociation kinetics, described below.

Evidence that Rho-MatB exists in multiple states was obtained from size exclusion chromatography coupled to multiangle laser light scattering data (Figure S4). Both Rho-MatB and the unlabeled protein in the absence of MgATP displayed single, broad peaks with molar mass ranging from ∼60 to 80 kDa, suggesting that there was equilibrium between different species, mainly monomer (58 kDa) possibly with some dimer. The addition of MgATP shifted the equilibrium toward monomer for the unlabeled protein. In contrast for Rho-MatB, the oligomerization changed little on ATP binding, so oligomers are unlikely to be the basis of the two conformations to explain the kinetic data.

Dissociation Kinetics of Rho-MatB.ATP

These were measured directly by rapidly mixing this complex with a large excess of unlabeled protein to trap dissociated ATP (Figure 4C). The fluorescence decreased with time. The dissociation was simulated using the conformational selection model (Figure 5A) and rate constants from the global fitting (Table S5). A better fit, giving the small second phase, was obtained assuming that the two unbound conformations of Rho-MatB had slightly different fluorescence intensities, so providing support for the model and parameters.

Enzymatic Activity

In order to confirm that the final construct, Rho-MatB, lacked enzymatic activity, as expected due to its K488A mutation, activity was measured using a coupled-enzyme assay with consumption of NADH (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide).4 Rho-MatB as well as the unlabeled variant showed no residual activity under the conditions tested (Figure S5). As a control, the similar Rho-MatB and RpMatB variants, but without the K488A mutation, showed enzymatic activity as expected.

Test Assay: Steady-State Production of ATP by Pyruvate Kinase

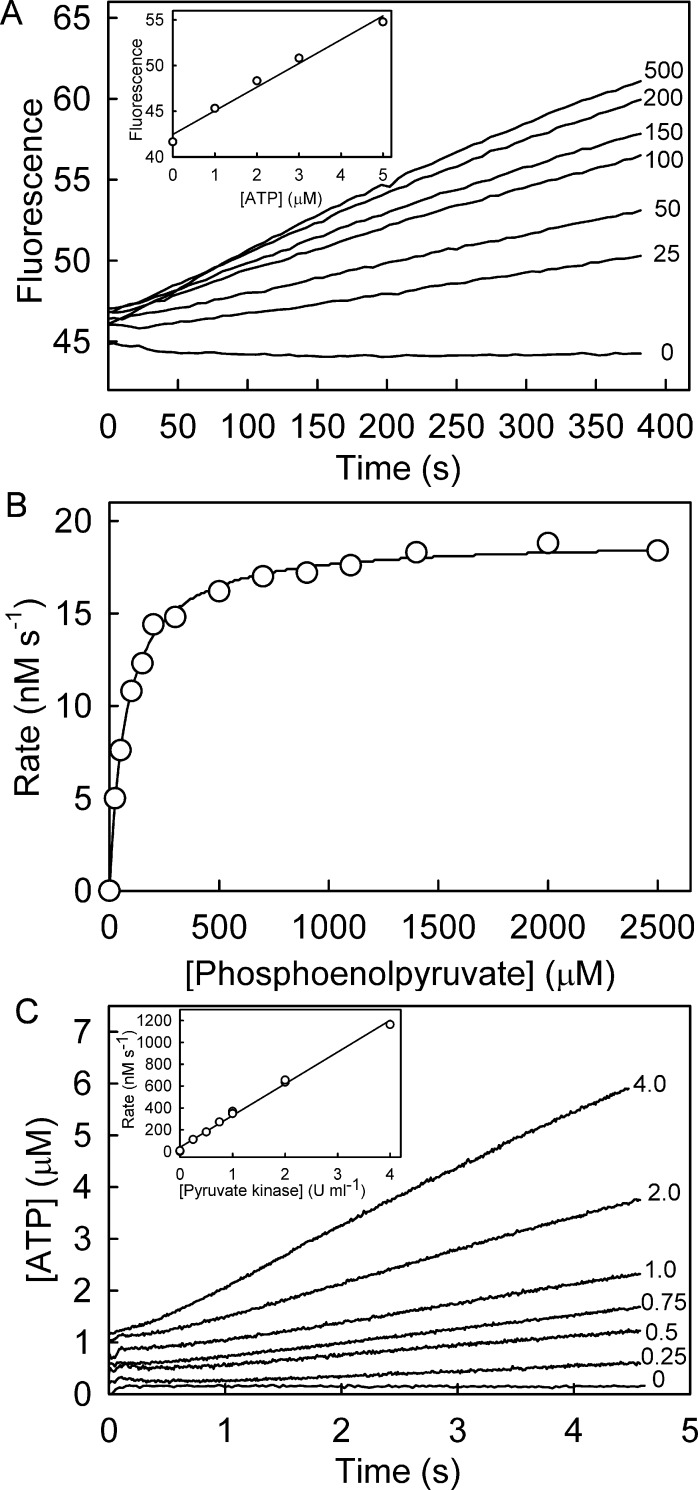

The ATP biosensor was tested in a steady-state assay in which ATP was produced from ADP and phosphoenolpyruvate, catalyzed by pyruvate kinase (Figure 6). This reaction was chosen as there is a coupled-enzyme assay for this enzyme that is well established and could be used to validate the biosensor results. The rate of ATP formation was measured at different concentrations of phosphoenolpyruvate using Rho-MatB. The resulting fluorescence traces (Figure 6A) were analyzed using a calibration curve between 0 and 5 μM ATP, obtained under similar experimental conditions (Figure 6A inset). Rates of ATP formation were plotted as a function of phosphoenolpyruvate concentration and fitted to Michaelis–Menten kinetics (Figure 6B), giving a Km of 103 μM and a specific activity of 0.76 μM s–1 U–1 mL.

Figure 6.

The production of ATP by pyruvate kinase, monitored by Rho-MatB. (A) Time courses of fluorescence change upon ATP production by pyruvate kinase at different phosphoenolpyruvate concentrations: see Methods for details. The initial rates were determined by linear regression, using the slope obtained from a linear calibration (inset). (B) The parameters Km (75.5 ± 3.4 μM) and Vmax (0.019 ± 0.002 μM s–1) were obtained from a curve fit to the Michaelis–Menten model. The average Km and Vmax values (n = 5) are 103 ± 10 μM and 0.0190 ± 0.0004 μM s–1. This gives an average specific activity of 0.76 ± 0.02 μM s–1 U–1 mL. (C) Time courses of ATP production by pyruvate kinase as monitored by Rho-MatB in a stopped-flow apparatus: see Methods for details. Traces are offset by 0.20 μM ATP from each other for clarity. Rates were determined by linear regression and were plotted versus pyruvate kinase concentration (inset).

To compare, pyruvate formation was also measured using a coupled-enzyme assay under the same solution conditions but using a higher concentration of pyruvate kinase, since this assay is much less sensitive. This assay coupled the pyruvate kinase reaction to that of lactate dehydrogenase, in which NADH reduced the pyruvate and was converted to NAD+. This assay gave a Km of 251 μM and a specific activity of 0.65 μM s–1 U–1 mL (Figure S6). The specific activity was similar to that obtained using Rho-MatB. Reasons why the Km is different for the two assays probably relate to potential product inhibition effects due to the different extents of reaction required to perform the two assays. Because the assay using the biosensor was more sensitive, only a low extent of reaction was required. In the NADH-based assay, pyruvate production was measured through lactate dehydrogenase, but with significantly less sensitivity, so the product concentrations were much higher.

In order to test the ability of Rho-MatB to assay more rapid ATP production, measurements were done with higher concentrations of pyruvate kinase (Figure 6C). The observed rate was proportional to the amount of pyruvate kinase added (Figure 6C inset), suggesting that it can measure rates of ATP formation >1 μM s–1.

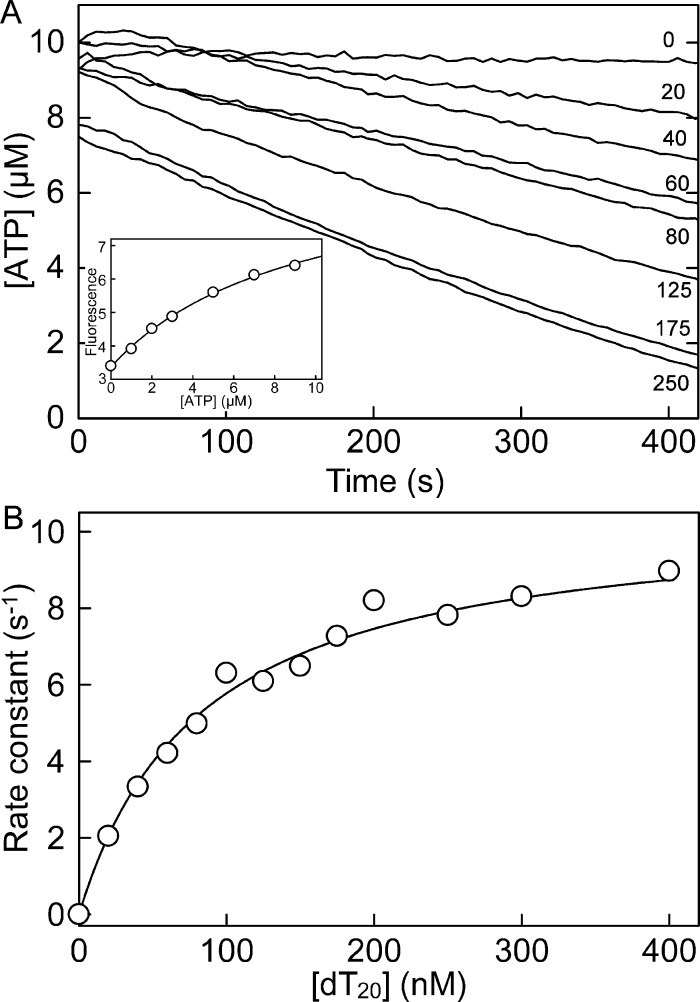

Test Assay: Steady-State ATP Depletion by PcrA

To demonstrate its ability in a different type of assay, Rho-MatB was also tested in a steady-state assay in which ATP was consumed by PcrA helicase, coupling ATP hydrolysis to translocation on DNA (Figure 7). In this case, a short oligonucleotide, dT20, was used as this activity is well characterized and comparable steady state data are available.16 The rate of ATP consumption was measured at different concentrations of dT20 using Rho-MatB. The resulting fluorescence time courses (Figure 7A) gave the rates of ATP consumption as a function of dT20 concentration (Figure 7B), producing a Km of 82.5 nM and a kcat of 10.5 s–1. These values are in good agreement with data obtained using a different assay, namely measurement of product formation.16 Although in general depletion assays are less desirable than assays that measure formation of a product, there may be cases where products are not accessible for measurement or such product assays cannot be applied due to interference.

Figure 7.

The depletion of ATP by PcrA, monitored by Rho-MatB. The measurement was done at 10 μM ATP, using 1 μM Rho-MatB at different concentrations of dT20. Thus, the presence of the biosensor has little effect on the concentration of free ATP and, as the Km for ATP with PcrA is ∼3 μM, the rates at saturating dT20 can be close to maximum. (A) Time courses at nanomolar dT20 concentrations shown. Data were converted from fluorescence to [ATP] using a calibration curve (inset), with identical solution conditions at the highest concentration of dT20, fitted to a hyperbola so that the whole concentration range was accessible. (B) The rates obtained by linear regression were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten model. The average Km and kcat values (n = 3) are 82.5 ± 13.2 nM and 10.5 ± 0.6 s–1.

Summary of Rho-MatB Features to Monitor ATP Production in Vitro

The biosensor is particularly aimed at measurements of ATP formation in vitro with relatively high time resolution. This makes it suitable for a range of real-time, kinetic assays, which can be done under conditions that are close to physiological pH and ionic strength. A major advantage of reagentless biosensors is that the addition of only a single species is required to monitor the analyte, in this case ATP, thereby minimizing the likelihood of interference by extra added reagents. Conversely, there are less added reagents that might be inhibited by components of the system under study. This may be a major disadvantage when using enzyme-coupled assays, including the luciferase–luciferin system,17 or aptamer-based methods, such as in combination with nanomaterials or ribozymes.18

Rho-MatB is very specific for ATP relative to ADP. Rho-MatB has 67-fold higher affinity for ATP than ADP. In comparison, ATeam, which is a biosensor based on the epsilon subunit of the bacterial F0F1-ATP synthase sandwiched by a variant of the cyan fluorescent protein and a variant of the yellow fluorescent protein, has a 30-fold higher affinity for ATP than ADP.19

Tetramethylrhodamine has several favorable properties as a reporter. It usually has a high fluorescence quantum yield in a monomeric state. Its fluorescence is unlikely to interfere with, or be affected by, the system being studied because of excitation around 550 nm and emission around 570 nm. In addition, tetramethylrhodamine has high photostability, making it suitable for high intensity excitation or long exposure. So Rho-MatB provides a robust and sensitive way to measure ATP concentrations with high time resolution. It is suitable for assays in near physiological solution conditions and shows high discrimination against ADP.

Methods

Materials

ATP, ADP, 2′-dATP, ATPγS, AMP-PNP, NADH, and phosphoenolpyruvate were from Sigma. 6-IATR (6-iodoacetamidotetramethylrhodamine),20 MDCC, and IDCC (7-diethylamino-3-((((2-iodoacetomido)ethyl)amino)carbonyl)coumarin)21 were a gift from Dr. John Corrie (MRC National Institute for Medical research, London).

Selection of Protein Scaffold

All available structures of proteins expressed in E. coli with either ATP or an ATP analogue bound were extracted from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).22 To obtain the ligand-free structure, corresponding to each of those ligand-bound structures, the sequences of all available PDB structures of proteins expressed in E. coli were compared with the ligand-bound sequences using CD-HIT2D.23 This program identified the sequences in one database that are similar to the other database. Sequences with >90% sequence identity were considered to be the same protein, and those ligand-bound and apo structures were compared using PyMOL (Version 1.3, Schrödinger, LLC).

Preparation of RpMatB, Labeled with Fluorescent Dyes

Plasmid design, protein expression in E. coli, purification, and labeling with fluorescent dyes are described in the Supporting Information.

Absorbance and Fluorescence Measurements

Absorbance measurements were made on a Jasco V-550 UV–vis Spectrophotometer. Fluorescent measurements were obtained on a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer (Agilent Technologies), using a 3 mm path-length quartz cuvette (Hellma), unless otherwise mentioned. Excitation and emission slits were set at 5 nm. Protein and nucleotide concentrations and buffer conditions are given in the figure legends. For titrations with Rho-MatB, excitation was at 553 nm, emission at 571 nm.

Data from titrations to measure nucleotide binding were corrected for dilution and analyzed with a quadratic binding curve using Grafit software:24

where P and L are the total concentrations of protein and ligand, respectively, Kd is the dissociation constant, and Fmin and Fmax are the fluorescence intensities of the free and ligand-bound proteins, respectively.

Stopped-Flow Measurements

Stopped flow experiments were carried out using a HiTech SF-61DX2 apparatus (TgK Scientific) with a xenon–mercury lamp and operated by Kinetic Studio software (TgK Scientific). The excitation wavelength was 548 nm, and there was an OG570 cutoff filter (Schott Glass) on the emission. The concentrations in the text and figures are those in the mixing chamber. Data were fitted to theoretical equations using the Kinetic Studio software. KinTek Global Kinetic Explorer software (version 4.0)25,26 was used to simulate kinetic schemes and for global fitting: see the Supporting Information.

Steady-State Analysis of ATP Production by Pyruvate Kinase

Steady-state activity measurements of pyruvate kinase (rabbit muscle from Sigma) were obtained using fluorescence or absorbance on a CLARIOstar microplate reader (BMG Labtech). Absorbance measurements used 96-well polystyrene microplates (black, clear flat bottom, Corning). Fluorescence measurements used 96-well polystyrene microplates (black, F-bottom, Greiner). Reaction mixtures (200 μL) contained 50 mM Tris·HCl at pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.3 mg mL–1 bovine serum albumin, 250 μM ADP, 2.5 μM Rho-MatB, and various phosphoenolpyruvate concentrations. The emission at 580 nm (10 nm bandwidth) after excitation at 545 nm (10 nm bandwidth) was recorded. A calibration curve was determined using various concentrations of ATP added to the solution above in the presence of 2.5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate. Reactions were started by the addition of pyruvate kinase (0.025 U mL–1), and the change in fluorescence signal was monitored at 20 °C. Linear regression analysis was used to determine the initial velocity.

Steady-state measurements of pyruvate kinase activity were also obtained using a stopped-flow apparatus, as above. The excitation wavelength was 548 nm, and there was an OG570 cutoff filter on the emission. Reaction mixtures contained 50 mM Tris·HCl at pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.3 mg mL–1 bovine serum albumin, 250 μM ADP, 100 μM phosphoenolpyruvate, and 2.5 μM Rho-MatB. Reactions were started by the addition of pyruvate kinase, and the change in fluorescence signal was monitored at 25 °C. A calibration curve was obtained using various concentrations of ATP added to the solution as above except without pyruvate kinase.

Steady-State Analysis of ATP Depletion by PcrA

Steady-state activity of a DNA helicase, PcrA, purified as described,16 was measured using fluorescence on a microplate reader, as described above. Reaction mixtures (200 μL) contained 50 mM Tris·HCl at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mg mL–1 bovine serum albumin, 10 μM ATP, 1.0 μM Rho-MatB, and various dT20 concentrations. Reactions were started by the addition of PcrA helicase (2 nM), and the change in fluorescence signal was monitored at 20 °C.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank L. Arnold (The Francis Crick Institute, London) for help with the CLARIOstar microplate reader, S. Howell (The Francis Crick Institute, London) for mass spectral analysis, S. Kunzelmann (The Francis Crick Institute, London) for help with experimental design and data analysis, and I. Taylor (The Francis Crick Institute, London) for help performing SEC-MALLS experiments. We thank J. Corrie (MRC National Institute for Medical Research, London) for gifts of IDCC, MDCC, and 6-IATR and J. Escalante-Semerena (University of Georgia, Athens) for providing the pRpMatB39 plasmid.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00346.

Methods, tables, and figures (PDF)

This work was supported by the Francis Crick Institute, which receives its core funding principally from Cancer Research UK, the UK Medical Research Council, and the Wellcome Trust.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Part of this work is subject of a UK patent application (1505662.5) by the Medical Research Council and the Francis Crick Institute.

Supplementary Material

References

- Burnstock G. (2012) Purinergic signalling: its unpopular beginning, its acceptance and its exciting future. BioEssays 34, 218–225 10.1002/bies.201100130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idzko M.; Ferrari D.; Eltzschig H. K. (2014) Nucleotide signalling during inflammation. Nature 509, 310–317 10.1038/nature13085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann S.; Solscheid C.; Webb M. R.. Fluorescent biosensors: design and application to motility proteins. In Fluorescent Methods Applied to Molecular Motors, Experientia Supplementum; Toseland C. P., Fili N., Eds.; Basel: Springer, 2014; Vol. 105, pp 25–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby H. A.; Rank K. C.; Rayment I.; Escalante-Semerena J. C. (2012) Structure-guided expansion of the substrate range of methylmalonyl coenzyme A synthetase (MatB) of Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 6619–6629 10.1128/AEM.01733-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D.; Bateman A.; Clements J.; Coggill P.; Eberhardt R. Y.; Eddy S. R.; Heger A.; Hetherington K.; Holm L.; Mistry J.; Sonnhammer E. L.; Tate J.; Punta M. (2014) Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(Database issue), D222–30 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulick A. M. (2009) Conformational dynamics in the Acyl-CoA synthetases, adenylation domains of non-ribosomal peptide synthetases, and firefly luciferase. ACS Chem. Biol. 4, 811–827 10.1021/cb900156h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune M.; Hunter J. L.; Corrie J. E. T.; Webb M. R. (1994) Direct, real-time measurement of rapid inorganic phosphate release using a novel fluorescent probe and its application to actomyosin subfragment 1 ATPase. Biochemistry 33, 8262–8271 10.1021/bi00193a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoh M. P.; Hunter J. L.; Corrie J. E. T.; Webb M. R. (2006) A biosensor for inorganic phosphate using a rhodamine-labeled phosphate binding protein. Biochemistry 45, 14764–14771 10.1021/bi060960j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillingham M. S.; Tibbles K. L.; Hunter J. L.; Bell J. C.; Kowalczykowski S. C.; Webb M. R. (2008) Fluorescent single-stranded DNA binding protein as a probe for sensitive, real time assays of helicase activity. Biophys. J. 95, 3330–3339 10.1529/biophysj.108.133512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann S.; Webb M. R. (2009) A biosensor for fluorescent determination of ADP with high time resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33130–33138 10.1074/jbc.M109.047118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann S.; Webb M. R. (2010) A fluorescent, reagentless biosensor for ADP based on tetramethylrhodamine-labeled ParM. ACS Chem. Biol. 5, 415–425 10.1021/cb9003173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasha M. (1963) Energy transfer mechanisms and the molecular exciton model for molecular aggregates. Radiat. Res. 20, 55–70 10.2307/3571331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasha M.; Rawls H. R.; Ashraf El-Bayoumi M. (1965) The exciton model in molecular spectroscopy. Pure Appl. Chem. 11, 371–392 10.1351/pac196511030371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn J. E.; Steinfeld J. I. (1972) Aggregation equilibria of xanthene dyes. J. Phys. Chem. 76, 762–774 10.1021/j100649a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R. W.; Kajiwara T.; Kearns D. R. (1974) Effect of dimer formation on the electronic absorption and emission spectra of ionic dyes. J. Phys. Chem. 78, 380–387 10.1021/j100597a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toseland C. P.; Martinez-Senac M. M.; Slatter A. F.; Webb M. R. (2009) The ATPase cycle of PcrA helicase and its coupling to translocation on DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 392, 1020–1032 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patergnani S.; Baldassari F.; De Marchi E.; Karkucinska-Wieckowska A.; Wieckowski M. R.; Pinton P. (2014) Methods to monitor and compare mitochondrial and glycolytic ATP production. Methods Enzymol. 542, 313–332 10.1016/B978-0-12-416618-9.00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C.; Dai S.; Wang L. (2014) Optical aptasensors for quantitative detection of small biomolecules: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 59, 64–74 10.1016/j.bios.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura H.; Huynh Nhat K. P.; Togawa H.; Saito K.; Iino R.; Kato-Yamada Y.; Nagai T.; Noji H. (2009) Visualization of ATP levels inside single living cells with fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based genetically encoded indicators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 15651–15656 10.1073/pnas.0904764106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munasinghe V. R. N.; Corrie J. E. T. (2006) Optimized synthesis of 6-iodoacetamidotetramethylrhodamine. ARKIVOC ii, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Corrie J. E. T. (1994) Thiol-reactive fluorescent probes for protein labelling. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2975–2982 10.1039/p19940002975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berman H. M.; Westbrook J.; Feng Z.; Gilliland G.; Bhat T. N.; Weissig H.; Shindyalov I. N.; Bourne P. E. (2000) The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Niu B.; Gao Y.; Fu L.; Li W. (2010) CD-HIT Suite: a web server for clustering and comparing biological sequences. Bioinformatics 26, 680–682 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherbarrow R. J.GraFit, Version 7; Erithacus Software Ltd: Horley, U.K., 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. A.; Simpson Z. B.; Blom T. (2009) Global Kinetic Explorer: A new computer program for dynamic simulation and fitting of kinetic data. Anal. Biochem. 387(1), 20–29 10.1016/j.ab.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. A.; Simpson Z. B.; Blom T. (2009) FitSpace explorer: an algorithm to evaluate multidimensional parameter space in fitting kinetic data. Anal. Biochem. 387, 30–41 10.1016/j.ab.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.