Significance

The question of whether a person’s position among siblings has a lasting impact on that person’s life course has fascinated both the scientific community and the general public for >100 years. By combining large datasets from three national panels, we confirmed the effect that firstborns score higher on objectively measured intelligence and additionally found a similar effect on self-reported intellect. However, we found no birth-order effects on extraversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, or imagination. This finding contradicts lay beliefs and prominent scientific theories alike and indicates that the development of personality is less determined by the role within the family of origin than previously thought.

Keywords: birth order, personality, Big Five, within-family analyses, siblings

Abstract

This study examined the long-standing question of whether a person’s position among siblings has a lasting impact on that person’s life course. Empirical research on the relation between birth order and intelligence has convincingly documented that performances on psychometric intelligence tests decline slightly from firstborns to later-borns. By contrast, the search for birth-order effects on personality has not yet resulted in conclusive findings. We used data from three large national panels from the United States (n = 5,240), Great Britain (n = 4,489), and Germany (n = 10,457) to resolve this open research question. This database allowed us to identify even very small effects of birth order on personality with sufficiently high statistical power and to investigate whether effects emerge across different samples. We furthermore used two different analytical strategies by comparing siblings with different birth-order positions (i) within the same family (within-family design) and (ii) between different families (between-family design). In our analyses, we confirmed the expected birth-order effect on intelligence. We also observed a significant decline of a 10th of a SD in self-reported intellect with increasing birth-order position, and this effect persisted after controlling for objectively measured intelligence. Most important, however, we consistently found no birth-order effects on extraversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, or imagination. On the basis of the high statistical power and the consistent results across samples and analytical designs, we must conclude that birth order does not have a lasting effect on broad personality traits outside of the intellectual domain.

Does a person’s position among siblings have a lasting impact on that person’s life course? This question has fascinated both the scientific community and the general public for >100 y. In 1874, Francis Galton—the youngest of nine siblings—analyzed a sample of English scientists to find that firstborns were overrepresented (1). He suspected that eldest sons enjoy special treatment by their parents, allowing them to thrive intellectually. Half a century later, Alfred Adler, the second of six children, extended the psychology of birth order to personality traits (2). From his point of view, firstborns were privileged, but also burdened by feelings of excessive responsibility and a fear of dethronement and were thus prone to score high on neuroticism. Conversely, he expected later-borns, overindulged by their parents, to lack social empathy.

Since then, empirical research on the relationship between birth order and intelligence has convincingly documented that performances in psychometric intelligence tests decline slightly from firstborns to later-borns (3), an effect that has been shown repeatedly (4–6) and its underlying causes investigated in depth (7, 8) to date. By contrast, the search for birth-order effects on personality has resulted in a vast body of inconsistent findings, as documented by reviews in the 1970s and 1980s (9, 10).

Nearly 70 y after Adler’s observations, Frank Sulloway revitalized the scientific debate by proposing his Family Niche Theory of birth-order effects in 1996 (11). On the basis of evolutionary considerations, he argued that adapting to divergent roles within the family system reduces competition and facilitates cooperation, potentially enhancing a sibship’s fitness—thus, siblings are like Darwin’s finches (12). Birth order reflects disparities in age, size, and power and should therefore determine the niches that siblings occupy within the family system. These specific adaptations to family dynamics are assumed to translate into stable personality differences between siblings that depend on birth order and can be expressed in terms of the Big Five personality traits, the standard taxonomy in psychology (13), consisting of the five broad dimensions: extraversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience.

According to Sulloway’s theory, firstborns, who are physically superior to their siblings at a young age, are more likely to show dominant behavior and therefore become less agreeable. Later-borns, searching for other ways to assert themselves, tend to rely on social support and become more sociable and thus more extraverted.* Siblings compete for scarce resources, and parental favor can be a crucial part of survival. Firstborns try to please their parents by acting as surrogate parents for their siblings, a behavior that can increase conscientiousness. Predictions for imagination and intellect, both subdimensions of the Big Five trait openness to experience (14), tend to differ. Later-borns are constrained to finding an unoccupied family niche through exploration and therefore score higher on imagination. Firstborns perform better on psychometric intelligence tests and correspondingly score higher on intellect, a self-reported trait correlated with objectively measured intelligence (15). Finally, no birth-order effects on overall emotional stability were assumed (12). However, for specific emotional stability items, Sulloway (15) had predicted firstborns to be more anxious and quicker to anger, and later-borns to be more depressed, vulnerable, self-conscious, and impulsive.

Sulloway first supported his framework by analyzing the social attitudes and birth-order positions of historical figures (ref. 11; but see ref. 16). Later, Sulloway’s hypotheses about personality were confirmed by several empirical studies (12, 15, 17). Nevertheless, a considerable number of other studies have supported only part of his hypotheses or have not found any birth-order effects at all (18–22). Paulhus (23) suggested that these conflicting findings may be due to different research designs: Studies comparing individuals from different families (between-family design) supposedly lack the power to detect subtle effects on personality because large parts of the variance in personality are not caused by birth order, but by variables such as socioeconomic status and genetic predispositions. A more powerful design compares siblings from the same families who are matched on many of these potential confounding variables and share a considerable number of genes. Indeed, all studies that confirmed Sulloway’s hypotheses (12, 15, 17) applied a within-family design. However, all of these studies also assessed sibling personality in a convenient, but potentially problematic, way because ratings were collected from only one sibling per family, who rated him/herself and his/her siblings at the same time. Existing beliefs and stereotypes about birth order (24), as well as contrast effects, could easily skew such ratings. To test whether birth order has a profound impact on personality, independent assessments of each sibling’s personality should be compared. To our knowledge, only one study has actually used independent ratings of the Big Five in a within-family design thus far (21), and it found no birth-order effects. However, this finding may be the consequence of low power because the sample comprised only 69 sibling pairs.

The current study aims to settle the debate on the systematic impact of birth order on personality by overcoming all of these limitations. Specifically, (i) only data with an independent assessment of siblings’ personality were used; (ii) multiple large national panels were combined to acquire data that would be sufficient to test even small birth-order effects with adequate power; and (iii) birth-order effects on personality were tested by using both within- and between-family designs. As explained above, between-family designs are inherently less powerful, but not useless per se: According to the law of large numbers, the results of both analytical approaches should converge with increasing sample size. We therefore expected the results from the between- and within-family analyses to be consistent.

The data came from the National Child Development Study (NCDS; Great Britain; refs. 25 and 26), the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 Cohort (NLSY 97; United States; ref. 27), and the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP; Germany; refs. 28 and 29). All panels included self-report personality inventories and measures of intelligence.

Changes in personality over time—e.g., becoming more conscientious with increasing age (30)—are inherently confounded with birth order, a problem that is especially evident in a within-family design: Firstborns are, of course, always older than their later-born siblings, and this fact can cause spurious associations between birth order and personality. To rule out age effects in the NLSY and SOEP samples, we converted the personality variables into age-adjusted T scores (M = 50, SD = 10) and the results of the intelligence tests into age-adjusted intelligence quotient (IQ) scores (M = 100, SD = 15). It was not necessary to control for age in the NCDS sample because all participants were of the same age.

Another potential confounding variable is sibship size. There are more later-borns in larger sibships. Hence, differences between first- and later-borns might emerge because later-borns are more likely to be born into families with a lower socioeconomic status, which can in turn be associated with differences in intelligence and personality. For this reason, we controlled for the effects of sibship size in all between-family analyses. Because there should be no association between birth-order position and parental socioeconomic status beyond what is explained by sibship size, additional control for parental socioeconomic status was deemed unnecessary. Finally, within-family analyses did not require statistical control for sibship size because they only compare individuals from the same sibship. Individuals from families with more than four siblings were excluded from the analyses because they made up only a small part of the sample (<11%), leading to insufficient power to detect the subtle effects that would have been expected. Between-family (n = 17,030) and within-family (n = 3,156) analyses were performed on nonoverlapping samples (see Table S1 for details of the sample sizes).

Table S1.

Number of participants included in the between and within-family analyses by panel, sibship size, and birth-order position

| Sibship size | Birth order | Total by sibship size | Total | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Between-family analyses | |||||||

| NCDS | |||||||

| Personality | 2 | 1,025 | 993 | 2,018 | 4,489 | ||

| 3 | 590 | 529 | 452 | 1,571 | |||

| 4 | 244 | 282 | 220 | 154 | 900 | ||

| Intelligence | 2 | 1,571 | 1,597 | 3,168 | 7,256 | ||

| 3 | 898 | 883 | 745 | 2,526 | |||

| 4 | 409 | 506 | 364 | 283 | 1,562 | ||

| NLSY | |||||||

| Personality | 2 | 975 | 757 | 1,732 | 3,178 | ||

| 3 | 457 | 261 | 308 | 1,026 | |||

| 4 | 153 | 93 | 78 | 96 | 420 | ||

| Intelligence | 2 | 904 | 730 | 1,634 | 2,914 | ||

| 3 | 412 | 232 | 281 | 925 | |||

| 4 | 121 | 68 | 70 | 96 | 355 | ||

| SOEP | |||||||

| Personality | 2 | 2,863 | 2,351 | 5,214 | 9,363 | ||

| 3 | 1,093 | 1,021 | 786 | 2,900 | |||

| 4 | 357 | 329 | 314 | 249 | 1,249 | ||

| Intelligence | 2 | 956 | 734 | 1,690 | 3,117 | ||

| 3 | 355 | 356 | 262 | 1,001 | |||

| 4 | 134 | 120 | 109 | 91 | 454 | ||

| Combined | |||||||

| Personality | 2 | 4,863 | 4,101 | 8,964 | 17,030 | ||

| 3 | 2,140 | 1,811 | 1,546 | 5,497 | |||

| 4 | 754 | 704 | 612 | 499 | 2,569 | ||

| Intelligence | 2 | 3,441 | 3,061 | 6,492 | 13,287 | ||

| 3 | 1,665 | 1,471 | 1,288 | 4,424 | |||

| 4 | 664 | 694 | 543 | 470 | 2,371 | ||

| Within-family analyses | |||||||

| NLSY | |||||||

| Personality | 2 | 366 | 366 | 732 | 2,062 | ||

| 3 | 271 | 384 | 164 | 819 | |||

| 4 | 123 | 183 | 142 | 63 | 511 | ||

| Intelligence | 2 | 448 | 448 | 896 | 2,399 | ||

| 3 | 307 | 451 | 196 | 954 | |||

| 4 | 112 | 187 | 166 | 84 | 549 | ||

| SOEP | |||||||

| Personality | 2 | 311 | 311 | 622 | 1,094 | ||

| 3 | 119 | 128 | 103 | 350 | |||

| 4 | 36 | 37 | 28 | 21 | 122 | ||

| Combined | |||||||

| Personality | 2 | 677 | 677 | 1,354 | 3,156 | ||

| 3 | 390 | 512 | 267 | 1,169 | |||

| 4 | 159 | 220 | 170 | 84 | 633 | ||

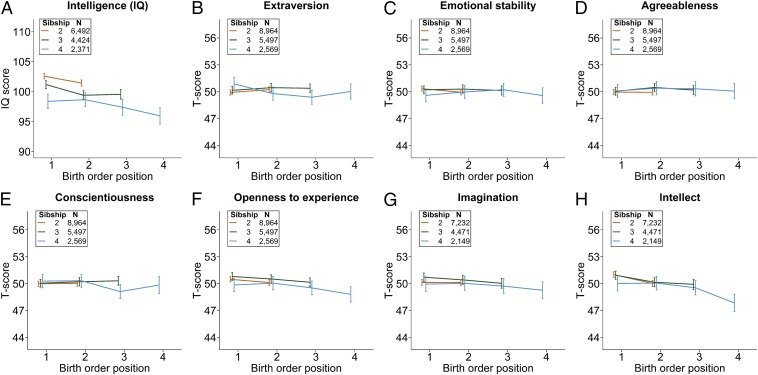

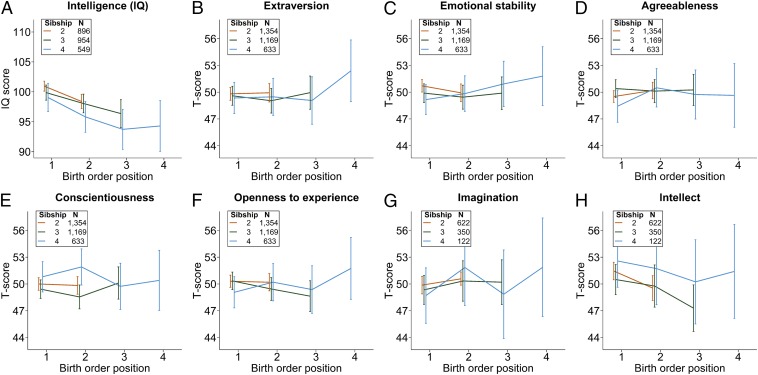

We first examined the effects of birth order on intelligence by using between-family analyses in each of the three panels, as well as in the combined sample. These analyses revealed the expected decline in IQ scores from first- to later-borns both for the combined sample (Fig. 1A) and for each separate panel (Table 1). This birth-order effect was also found in the within-family analyses (Fig. 2A and Table 1). The observed effect of ∼1.5 IQ points (i.e., 10% of a SD) for each increase in birth-order position is in line with previous findings (3–6). To illustrate this small effect, in our between-family sample of sibships of two, a randomly picked firstborn had a 52% chance of having a higher IQ than a randomly picked secondborn; conversely, a secondborn had a 48% chance of having a higher IQ than a firstborn. The effect was more prominent in our within-family sample due to the greater similarity of siblings from the same family: In sibships of two, the older sibling had a higher IQ than his or her younger sibling in 6 of 10 cases. This replicated finding not only underlines the robustness of birth-order effects on intelligence, but also indicates that our samples and analytical strategies were appropriate for detecting existing birth-order effects.

Fig. 1.

Effects of birth order position and sibship size on personality and intelligence. Mean scores and 95% confidence intervals are displayed for intelligence (A) and personality (B–H), depending on sibship size and birth-order position in the combined between-family sample that included the NCDS, NLSY, and SOEP participants. Personality variables were standardized as T-scores with a mean of 50 and SD of 10; intelligence was standardized as an IQ score with a mean of 100 and SD of 15. Birth-order effects were significant for intelligence, openness to experience, and intellect (Table 1). (B–H) Personality traits were as follows: extraversion (B), emotional stability (C), agreeableness (D), conscientiousness (E), openness to experience (F), imagination (G), and intellect (H).

Table 1.

Tests of statistical significance for effects of birth-order on intelligence and personality

| Trait | Between-family analyses | Within-family analyses | ||||||||||||

| Combined sample | NCDS | NLSY* | SOEP | Combined sample | NLSY* | SOEP† | ||||||||

| F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | |

| Intelligence (IQ) | 11.80 | <0.001 | 10.40 | <0.001 | 3.87 | 0.009 | 2.69 | 0.045 | 11.82 | <0.001 | ||||

| Extraversion | 0.62 | 0.600 | 1.10 | 0.346 | 1.50 | 0.212 | 1.53 | 0.204 | 1.87 | 0.132 | 1.88 | 0.131 | 0.22 | 0.883 |

| Emotional stability | 0.57 | 0.638 | 0.93 | 0.427 | 0.43 | 0.729 | 0.65 | 0.584 | 1.17 | 0.319 | 0.12 | 0.946 | 2.24 | 0.083 |

| Agreeableness | 0.26 | 0.858 | 1.51 | 0.209 | 0.77 | 0.512 | 2.11 | 0.096 | 0.76 | 0.517 | 0.90 | 0.442 | 0.42 | 0.740 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.25 | 0.863 | 0.83 | 0.475 | 0.48 | 0.695 | 1.23 | 0.296 | 0.17 | 0.914 | 0.13 | 0.944 | 0.15 | 0.928 |

| Openness | 3.64 | 0.012 | 3.57 | 0.014 | 0.06 | 0.979 | 1.97 | 0.116 | 1.70 | 0.164 | 1.29 | 0.277 | 0.43 | 0.733 |

| Imagination | 1.43 | 0.232 | 0.84 | 0.470 | 0.76 | 0.516 | 0.55 | 0.647 | ||||||

| Intellect | 13.32 | <0.001 | 5.32 | 0.001 | 9.33 | <0.001 | 4.59 | 0.004 | ||||||

The sample sizes used in these analyses varied between 2,914 and 17,030 for the between-family analyses and between 1,094 and 3,156 for the within-family analyses. See Table S1 for the specific sample sizes.

In the NLSY, due to the content of the questionnaire, openness to experience could not be decomposed into imagination and intellect.

In the within-family sample of the SOEP, there were not enough individuals with information on IQ (n = 141) to conduct meaningful analyses, given the small effect sizes that were expected.

Fig. 2.

Effects of birth-order position and sibship size on personality and intelligence. Predicted mean scores from fixed-effects regressions and 95% confidence intervals are displayed for intelligence (A) and personality (B–H) depending on sibship size and birth-order position in the combined within-family sample that included the NLSY and SOEP participants. Birth-order effects were significant for intelligence and intellect (Table 1). (B–H) Personality traits were as follows: extraversion (B), emotional stability (C), agreeableness (D), conscientiousness (E), openness to experience (F), imagination (G), and intellect (H).

Our main analyses for investigating the relationship between birth-order position and personality led to consistent results for four of the Big Five personality traits. Birth-order position had no significant effect on extraversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, or conscientiousness in the between-family analyses or in the within-analyses (Figs. 1 B–E and 2 B–E; Table 1). We confirmed these nil effects by conducting separate analyses for each of the three panels (Table 1). We additionally analyzed each of the three sibship sizes separately. Tables S2–S5 show the mean scores and detailed results by panel and sibship size of all between- and within-family analyses. Again, birth-order position had no consistent effect on any of these four personality traits. An additional analysis of specific emotional-stability items on which opposing birth-order effects were hypothesized by Sulloway (15) also yielded no significant results (Tables S3 and S4).

Table S2.

Mean scores and results of between-family analyses (NCDS, NLSY, and SOEP) and within-family analyses (NLSY and SOEP)

| Sib-ship size | Between-family | Within-family | |||||||||||||||

| n | Observed mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of sibship size | Effect of birth order | n | Estimated mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of birth order | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F | P | F | P | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F | P | ||||

| Extraversion | 2 | 8,964 | 49.92 | 50.23 | 2.30 | 0.129 | 1,354 | 49.81 | 49.93 | 0.05 | 0.821 | ||||||

| 3 | 5,497 | 50.15 | 50.45 | 50.39 | 0.48 | 0.618 | 1,169 | 49.60 | 49.04 | 49.94 | 0.74 | 0.478 | |||||

| 4 | 2,569 | 50.87 | 49.79 | 49.39 | 50.03 | 2.83 | 0.037 | 633 | 49.35 | 49.48 | 49.07 | 52.40 | 1.83 | 0.142 | |||

| 17,030 | 1.50 | 0.224 | 0.62 | 0.600 | 3,156 | 1.87 | 0.132 | ||||||||||

| Emotional stability | 2 | 8,964 | 50.34 | 49.95 | 3.57 | 0.059 | 1,354 | 50.71 | 49.93 | 2.41 | 0.121 | ||||||

| 3 | 5,497 | 50.22 | 50.30 | 50.14 | 0.12 | 0.884 | 1,169 | 49.89 | 49.44 | 49.89 | 0.30 | 0.743 | |||||

| 4 | 2,569 | 49.60 | 49.98 | 50.22 | 49.58 | 0.63 | 0.593 | 633 | 49.17 | 49.84 | 50.93 | 51.79 | 0.93 | 0.427 | |||

| 17,030 | 0.72 | 0.487 | 0.57 | 0.638 | 3,156 | 1.17 | 0.319 | ||||||||||

| Agreeableness | 2 | 8,964 | 49.97 | 49.93 | 0.04 | 0.852 | 1,354 | 49.51 | 50.19 | 2.07 | 0.151 | ||||||

| 3 | 5,497 | 50.05 | 50.48 | 50.18 | 0.90 | 0.405 | 1,169 | 50.40 | 50.12 | 50.25 | 0.09 | 0.910 | |||||

| 4 | 2,569 | 50.10 | 50.39 | 50.33 | 50.07 | 0.18 | 0.912 | 633 | 48.43 | 50.49 | 49.74 | 49.64 | 1.19 | 0.312 | |||

| 17,030 | 1.54 | 0.215 | 0.26 | 0.858 | 3,156 | 0.76 | 0.517 | ||||||||||

| Conscientious-ness | 2 | 8,964 | 49.99 | 50.02 | 0.00 | 0.944 | 1,354 | 50.00 | 49.84 | 0.10 | 0.753 | ||||||

| 3 | 5,497 | 50.04 | 50.20 | 50.31 | 0.32 | 0.725 | 1,169 | 49.42 | 48.54 | 50.10 | 2.21 | 0.111 | |||||

| 4 | 2,569 | 50.28 | 50.32 | 49.11 | 49.84 | 2.03 | 0.108 | 633 | 50.81 | 51.91 | 49.74 | 50.40 | 1.34 | 0.262 | |||

| 17,030 | 0.81 | 0.446 | 0.25 | 0.863 | 3,156 | 0.17 | 0.914 | ||||||||||

| Openness to experience | 2 | 8,964 | 50.48 | 50.12 | 3.17 | 0.075 | 1,354 | 50.31 | 50.19 | 0.05 | 0.817 | ||||||

| 3 | 5,497 | 50.79 | 50.52 | 50.15 | 1.87 | 0.155 | 1,169 | 50.35 | 49.44 | 48.63 | 2.01 | 0.136 | |||||

| 4 | 2,569 | 49.85 | 50.05 | 49.52 | 48.80 | 1.83 | 0.140 | 633 | 49.09 | 50.20 | 49.37 | 51.75 | 1.31 | 0.272 | |||

| 17,030 | 4.12 | 0.016 | 3.64 | 0.012 | 3,156 | 1.70 | 0.164 | ||||||||||

| Imagination | 2 | 7,232 | 50.14 | 50.12 | 0.01 | 0.922 | 622 | 49.78 | 49.95 | 0.01 | 0.908 | ||||||

| 3 | 4,471 | 50.71 | 50.42 | 50.03 | 1.70 | 0.183 | 350 | 49.34 | 50.33 | 50.20 | 0.42 | 0.659 | |||||

| 4 | 2,149 | 49.94 | 50.03 | 49.72 | 49.26 | 0.60 | 0.616 | 122 | 48.70 | 51.85 | 48.85 | 51.87 | 1.13 | 0.343 | |||

| 13,852 | 2.70 | 0.067 | 1.43 | 0.232 | 1,094 | 0.55 | 0.647 | ||||||||||

| Intellect | 2 | 7,232 | 51.01 | 50.01 | 19.43 | <0.001 | 622 | 51.45 | 49.54 | 7.31 | 0.007 | ||||||

| 3 | 4,471 | 50.94 | 50.15 | 49.92 | 4.50 | 0.011 | 350 | 50.50 | 49.77 | 47.29 | 3.18 | 0.044 | |||||

| 4 | 2,149 | 50.02 | 50.06 | 49.54 | 47.85 | 5.05 | 0.002 | 122 | 52.57 | 51.72 | 50.24 | 51.41 | 0.32 | 0.808 | |||

| 13,852 | 1.84 | 0.158 | 13.32 | <0.001 | 1,094 | 4.59 | 0.004 | ||||||||||

| Intelligence (IQ) | 2 | 6,492 | 102.58 | 101.45 | 13.45 | <0.001 | 896 | 100.94 | 98.38 | 17.84 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 3 | 4,424 | 101.19 | 99.40 | 99.56 | 9.02 | <0.001 | 954 | 99.87 | 98.05 | 96.37 | 4.68 | 0.010 | |||||

| 4 | 2,371 | 98.39 | 98.66 | 97.40 | 95.96 | 2.80 | 0.039 | 549 | 99.05 | 95.81 | 93.73 | 94.29 | 3.41 | 0.018 | |||

| 13,287 | 53.54 | <0.001 | 11.80 | <0.001 | 2,399 | 11.82 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

Table S5.

Mean scores and results of between- and within-family analyses (SOEP participants)

| Sibship size | Between-family | Within-family | |||||||||||||||

| n | Observed mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of sibship size | Effect of birth order | n | Estimated mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of birth order | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F | P | F | P | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F | P | ||||

| Extraversion | 2 | 5,214 | 49.53 | 50.22 | 5.96 | 0.015 | 622 | 49.68 | 49.92 | 0.10 | 0.753 | ||||||

| 3 | 2,900 | 50.13 | 50.52 | 50.50 | 0.54 | 0.585 | 350 | 49.85 | 48.67 | 49.63 | 0.43 | 0.650 | |||||

| 4 | 1,249 | 50.92 | 50.03 | 49.85 | 50.48 | 0.81 | 0.490 | 122 | 50.01 | 48.72 | 47.79 | 50.71 | 0.39 | 0.758 | |||

| 9,363 | 2.35 | 0.095 | 1.53 | 0.205 | 1,094 | 0.22 | 0.883 | ||||||||||

| Emotional stability | 2 | 5,214 | 50.24 | 49.94 | 1.12 | 0.290 | 622 | 51.18 | 49.47 | 5.43 | 0.021 | ||||||

| 3 | 2,900 | 50.36 | 50.03 | 50.36 | 0.36 | 0.697 | 350 | 48.93 | 49.84 | 50.84 | 1.01 | 0.365 | |||||

| 4 | 1,249 | 49.43 | 50.21 | 50.47 | 49.61 | 0.83 | 0.476 | 122 | 51.59 | 49.61 | 52.70 | 53.95 | 1.07 | 0.367 | |||

| 9,363 | 0.23 | 0.798 | 0.65 | 0.584 | 1,094 | 2.24 | 0.083 | ||||||||||

| Agreeableness | 2 | 5,214 | 49.81 | 49.83 | 0.00 | 0.952 | 622 | 49.61 | 49.92 | 0.21 | 0.647 | ||||||

| 3 | 2,900 | 50.46 | 50.91 | 49.57 | 4.19 | 0.015 | 350 | 50.36 | 49.27 | 51.34 | 1.44 | 0.240 | |||||

| 4 | 1,249 | 50.58 | 50.57 | 50.69 | 49.81 | 0.43 | 0.735 | 122 | 47.90 | 52.10 | 46.36 | 50.72 | 2.39 | 0.076 | |||

| 9,363 | 6.51 | 0.002 | 2.11 | 0.096 | 1,094 | 0.42 | 0.740 | ||||||||||

| Conscientious-ness | 2 | 5,214 | 49.74 | 49.95 | 0.60 | 0.438 | 622 | 50.30 | 49.98 | 0.18 | 0.674 | ||||||

| 3 | 2,900 | 50.09 | 50.52 | 50.24 | 0.50 | 0.606 | 350 | 49.25 | 47.66 | 48.80 | 0.90 | 0.407 | |||||

| 4 | 1,249 | 49.66 | 50.97 | 49.72 | 50.69 | 1.44 | 0.231 | 122 | 49.95 | 53.30 | 50.75 | 50.48 | 1.09 | 0.361 | |||

| 9,363 | 1.99 | 0.136 | 1.23 | 0.296 | 1,094 | 0.15 | 0.928 | ||||||||||

| Openness to experience | 2 | 5,214 | 50.36 | 49.95 | 2.21 | 0.137 | 622 | 50.32 | 49.82 | 0.50 | 0.480 | ||||||

| 3 | 2,900 | 50.79 | 50.38 | 49.84 | 2.10 | 0.122 | 350 | 49.58 | 50.20 | 49.35 | 0.30 | 0.740 | |||||

| 4 | 1,249 | 49.70 | 50.29 | 50.06 | 49.13 | 0.70 | 0.554 | 122 | 49.67 | 52.05 | 49.10 | 51.97 | 0.87 | 0.460 | |||

| 9,363 | 1.23 | 0.292 | 1.97 | 0.116 | 1,094 | 0.43 | 0.733 | ||||||||||

| Imagination | 2 | 5,214 | 50.10 | 50.04 | 0.06 | 0.812 | 622 | 49.78 | 49.91 | 0.01 | 0.908 | ||||||

| 3 | 2,900 | 50.65 | 50.45 | 49.90 | 1.36 | 0.256 | 350 | 49.35 | 50.50 | 50.26 | 0.42 | 0.659 | |||||

| 4 | 1,249 | 49.66 | 50.44 | 50.05 | 49.56 | 0.50 | 0.685 | 122 | 48.72 | 51.84 | 48.84 | 51.83 | 1.13 | 0.343 | |||

| 9,363 | 1.56 | 0.210 | 0.76 | 0.516 | 1,094 | 0.55 | 0.647 | ||||||||||

| Intellect | 2 | 5,214 | 50.94 | 49.75 | 19.36 | <0.001 | 622 | 51.39 | 49.50 | 7.31 | 0.007 | ||||||

| 3 | 2,900 | 50.85 | 50.03 | 49.76 | 3.25 | 0.039 | 350 | 50.62 | 49.62 | 47.40 | 3.18 | 0.044 | |||||

| 4 | 1,249 | 49.99 | 49.76 | 50.08 | 48.35 | 1.74 | 0.157 | 122 | 52.59 | 51.74 | 50.25 | 51.41 | 0.32 | 0.808 | |||

| 9,363 | 0.40 | 0.668 | 9.33 | <0.001 | 1,094 | 4.59 | 0.004 | ||||||||||

| Intelligence (IQ) | 2 | 1,756 | 102.46 | 101.37 | 3.00 | 0.084 | |||||||||||

| 3 | 1,028 | 100.71 | 98.49 | 101.69 | 4.04 | 0.018 | |||||||||||

| 4 | 474 | 98.36 | 97.55 | 96.29 | 98.48 | 0.38 | 0.766 | ||||||||||

| 3,258 | 16.56 | <0.001 | 2.69 | 0.045 | |||||||||||||

In the within-family sample of the SOEP, there were not enough individuals with information on IQ (n = 141) to conduct meaningful analyses, given the small effect sizes that were expected.

Table S3.

Mean scores and results of between-family analyses (NCDS participants)

| Sibship size | n | Birth order | Effect of sibship size | Effect of birth order | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F | P | F | P | |||

| Extraversion | 2 | 2,018 | 50.09 | 49.85 | 0.29 | 0.588 | ||||

| 3 | 1,571 | 50.23 | 50.02 | 50.70 | 0.58 | 0.559 | ||||

| 4 | 900 | 51.22 | 49.40 | 49.19 | 48.84 | 2.46 | 0.061 | |||

| 4,489 | 0.46 | 0.633 | 1.10 | 0.346 | ||||||

| Emotional stability | 2 | 2,018 | 50.59 | 50.11 | 1.20 | 0.274 | ||||

| 3 | 1,571 | 50.02 | 50.26 | 49.73 | 0.33 | 0.718 | ||||

| 4 | 900 | 49.95 | 50.22 | 49.62 | 48.80 | 0.72 | 0.540 | |||

| 4,489 | 0.25 | 0.776 | 0.93 | 0.427 | ||||||

| “I get upset easily“, “I get irritated easily“ | 2 | 2,010 | 49.52 | 50.40 | 3.57 | 0.059 | ||||

| 3 | 1,558 | 50.13 | 49.85 | 50.28 | 0.21 | 0.810 | ||||

| 4 | 890 | 49.77 | 49.42 | 49.79 | 51.52 | 1.59 | 0.190 | |||

| 4,458 | 0.44 | 0.643 | 1.97 | 0.117 | ||||||

| “I often feel blue“, “I seldom feel blue“ | 2 | 2,010 | 49.63 | 49.94 | 0.49 | 0.485 | ||||

| 3 | 1,558 | 49.54 | 50.03 | 50.51 | 1.17 | 0.312 | ||||

| 4 | 890 | 50.08 | 50.76 | 50.59 | 50.59 | 0.20 | 0.898 | |||

| 4,458 | 0.71 | 0.492 | 1.01 | 0.389 | ||||||

| Agreeableness | 2 | 2,018 | 50.20 | 50.03 | 0.15 | 0.703 | ||||

| 3 | 1,571 | 49.50 | 49.63 | 50.91 | 3.03 | 0.049 | ||||

| 4 | 900 | 49.79 | 50.14 | 50.12 | 49.76 | 0.10 | 0.961 | |||

| 4,489 | 0.84 | 0.433 | 1.51 | 0.209 | ||||||

| Conscientiousness | 2 | 2,018 | 50.67 | 50.15 | 1.39 | 0.239 | ||||

| 3 | 1,571 | 50.23 | 50.01 | 50.53 | 0.36 | 0.700 | ||||

| 4 | 900 | 50.38 | 49.58 | 48.67 | 48.98 | 1.24 | 0.294 | |||

| 4,489 | 1.64 | 0.194 | 0.83 | 0.475 | ||||||

| Openness to experience | 2 | 2,018 | 50.82 | 50.52 | 0.47 | 0.493 | ||||

| 3 | 1,571 | 51.08 | 50.39 | 50.22 | 1.14 | 0.321 | ||||

| 4 | 900 | 50.19 | 49.96 | 48.79 | 47.49 | 3.15 | 0.024 | |||

| 4,489 | 2.10 | 0.123 | 3.57 | 0.014 | ||||||

| Imagination | 2 | 2,018 | 50.24 | 50.32 | 0.04 | 0.849 | ||||

| 3 | 1,571 | 50.82 | 50.34 | 50.26 | 0.52 | 0.596 | ||||

| 4 | 900 | 50.36 | 49.54 | 49.25 | 48.78 | 0.98 | 0.401 | |||

| 4,489 | 1.54 | 0.214 | 0.84 | 0.470 | ||||||

| Intellect | 2 | 2,018 | 51.21 | 50.63 | 1.72 | 0.190 | ||||

| 3 | 1,571 | 51.10 | 50.38 | 50.20 | 1.28 | 0.279 | ||||

| 4 | 900 | 50.07 | 50.41 | 48.75 | 47.03 | 4.80 | 0.003 | |||

| 4,489 | 2.00 | 0.136 | 5.32 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Intelligence (IQ) | 2 | 3,168 | 103.70 | 102.71 | 3.87 | 0.050 | ||||

| 3 | 2,526 | 102.39 | 100.55 | 99.68 | 7.60 | 0.001 | ||||

| 4 | 1,562 | 99.31 | 99.23 | 98.48 | 95.40 | 4.65 | 0.003 | |||

| 7,256 | 28.03 | <0.001 | 10.40 | <0.001 | ||||||

Table S4.

Mean scores and results of between- and within-family analyses (NLSY participants)

| Sibship size | Between-family | Within-family | |||||||||||||||

| n | Observed mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of sibship size | Effect of birth order | n | Estimated mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of birth order | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F | P | F | P | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F | P | ||||

| Extraversion | 2 | 1,732 | 50.88 | 50.78 | 0.04 | 0.837 | 732 | 49.93 | 49.94 | 0.00 | 0.988 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,026 | 50.12 | 51.06 | 49.63 | 1.56 | 0.212 | 819 | 49.45 | 49.17 | 50.18 | 0.49 | 0.612 | |||||

| 4 | 420 | 50.20 | 50.14 | 48.09 | 50.79 | 1.26 | 0.287 | 511 | 48.93 | 49.56 | 49.50 | 53.22 | 1.83 | 0.142 | |||

| 3,178 | 1.03 | 0.358 | 1.50 | 0.212 | 2,062 | 1.88 | 0.131 | ||||||||||

| Emotional stability | 2 | 1,732 | 50.37 | 49.75 | 1.66 | 0.197 | 732 | 50.31 | 50.31 | 0.00 | 0.995 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,026 | 50.14 | 51.42 | 50.16 | 1.56 | 0.211 | 819 | 50.43 | 49.31 | 49.11 | 0.97 | 0.380 | |||||

| 4 | 420 | 49.46 | 48.45 | 50.89 | 50.73 | 1.30 | 0.275 | 511 | 48.55 | 49.85 | 50.52 | 51.12 | 0.68 | 0.564 | |||

| 3,178 | 1.17 | 0.311 | 0.43 | 0.729 | 2,062 | 0.12 | 0.946 | ||||||||||

| “I see myself as: anxious, easily upset” | 2 | 1,732 | 49.85 | 50.11 | 0.24 | 0.627 | 732 | 49.41 | 49.54 | 0.04 | 0.851 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,026 | 50.54 | 48.71 | 49.61 | 0.31 | 0.734 | 819 | 49.85 | 50.79 | 50.82 | 0.66 | 0.518 | |||||

| 4 | 420 | 50.80 | 52.47 | 48.87 | 49.29 | 4.36 | 0.005 | 511 | 50.75 | 50.05 | 49.94 | 49.52 | 0.16 | 0.926 | |||

| 3,178 | 2.95 | 0.053 | 2.53 | 0.055 | 2,062 | 0.14 | 0.936 | ||||||||||

| Agreeableness | 2 | 1,732 | 50.18 | 50.12 | 0.01 | 0.908 | 732 | 49.43 | 50.41 | 2.35 | 0.126 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,026 | 49.81 | 50.48 | 50.67 | 0.80 | 0.451 | 819 | 50.53 | 50.38 | 49.46 | 0.46 | 0.631 | |||||

| 4 | 420 | 49.49 | 50.50 | 49.47 | 51.24 | 0.75 | 0.521 | 511 | 48.52 | 50.20 | 50.42 | 49.30 | 0.76 | 0.517 | |||

| 3,178 | 0.29 | 0.751 | 0.77 | 0.512 | 2,062 | 0.90 | 0.442 | ||||||||||

| Conscien-tiousness | 2 | 1,732 | 50.01 | 50.05 | 0.01 | 0.927 | 732 | 49.74 | 49.71 | 0.00 | 0.971 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,026 | 49.67 | 49.36 | 50.16 | 0.46 | 0.630 | 819 | 49.42 | 48.91 | 50.89 | 1.85 | 0.158 | |||||

| 4 | 420 | 51.53 | 50.24 | 47.92 | 49.03 | 2.41 | 0.067 | 511 | 51.16 | 51.64 | 49.45 | 50.34 | 0.94 | 0.423 | |||

| 3,178 | 0.38 | 0.681 | 0.48 | 0.695 | 2,062 | 0.13 | 0.944 | ||||||||||

| Openness to experience | 2 | 1,732 | 50.48 | 50.14 | 0.53 | 0.465 | 732 | 50.30 | 50.51 | 0.09 | 0.758 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,026 | 50.44 | 51.30 | 50.85 | 0.62 | 0.537 | 819 | 50.75 | 49.18 | 48.07 | 2.89 | 0.057 | |||||

| 4 | 420 | 49.65 | 49.53 | 49.41 | 50.05 | 0.07 | 0.977 | 511 | 48.84 | 49.76 | 49.45 | 51.90 | 0.86 | 0.464 | |||

| 3,178 | 1.95 | 0.142 | 0.06 | 0.979 | 2,062 | 1.29 | 0.277 | ||||||||||

| Intelligence (IQ) | 2 | 1,634 | 100.79 | 98.76 | 7.69 | 0.006 | 896 | 100.94 | 98.38 | 17.84 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 3 | 925 | 99.01 | 96.42 | 97.25 | 2.56 | 0.078 | 954 | 99.87 | 98.05 | 96.37 | 4.68 | 0.010 | |||||

| 4 | 355 | 95.30 | 96.34 | 93.48 | 95.24 | 0.41 | 0.746 | 549 | 99.05 | 95.81 | 93.73 | 94.29 | 3.41 | 0.018 | |||

| 2,914 | 11.49 | <0.001 | 3.87 | 0.009 | 2,399 | 11.82 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

Regarding openness to experience, the fifth of the Big Five personality traits, our predictions differed for the subdimensions of intellect and imagination. Accordingly, we decomposed openness into intellect and imagination in the NCDS and the SOEP. Decomposition was not possible in the NLSY because the openness scale that was used did not contain any items that measured intellect. Whereas we observed no birth-order effects on imagination, we found significant effects on intellect in both the between- and within-family analyses (Figs. 1 G and H and 2 G and H; Table 1). We observed a decline in intellect of ∼1 T score (i.e., 10% of a SD) for each increase in birth-order position, an effect that is comparable in magnitude with the IQ effect. As a consequence of the different proportions of intellect items on the openness scales in the three samples, the analyses of the global openness to experience scale led to inconsistent results: Our analyses revealed a significant effect on openness to experience in the combined between-family sample (Fig. 1F), but panel-specific analyses showed that this effect was mainly driven by the NCDS sample and that this effect was not observable in the NLSY sample at all (Table 1).

The items used to measure intellect (e.g., NCDS, “I am quick to understand things”; SOEP, “I am someone who is eager for knowledge”) can be understood as an indirect measure of self-estimated intelligence. This idea was bolstered by the correlation between IQ scores and intellect in our study (r = 0.32, P < 0.001, in the combined between-family sample), a finding that matches meta-analytical findings on the correlation between self-estimated and objectively measured intelligence (31). To test whether the birth-order effect on self-reported intellect merely reflects differences in IQ scores, we reran the analysis on intellect, this time including IQ scores as a covariate. The effect on intellect slightly decreased in magnitude, but retained its significance, indicating that there is a genuine birth-order effect on intellect that goes beyond objectively measured intelligence (Table S6).

Table S6.

Intellect scores before and after adjusting for intelligence (IQ) and results of corresponding between-family analyses (NCDS and SOEP participants)

| Sibship size | n | Mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of sibship size | Effect of birth order | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F | P | F | P | |||

| Intellect | 2 | 3,562 | 51.47 | 50.26 | 13.73 | <0.001 | ||||

| 3 | 2,435 | 51.38 | 50.41 | 49.89 | 4.81 | 0.001 | ||||

| 4 | 1,299 | 50.78 | 50.46 | 49.80 | 47.49 | 6.62 | <0.001 | |||

| 7,296 | 0.15 | 0.858 | 13.55 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Intellect, adjusted for IQ scores | 2 | 3,562 | 51.39 | 50.35 | 10.80 | 0.001 | ||||

| 3 | 2,435 | 51.18 | 50.62 | 49.90 | 3.72 | 0.024 | ||||

| 4 | 1,299 | 50.49 | 50.38 | 50.01 | 47.78 | 5.52 | 0.001 | |||

| 7,296 | 1.75 | 0.174 | 10.13 | <0.001 | ||||||

In the NLSY, we were not able to decompose openness to experience into imagination and intellect due to the content of the questionnaire. Furthermore, we were not able to investigate whether the effect on intellect persisted after adjustment for IQ in a within-family design, because (i) in the NCDS there was no within-family data included due to the design of the study; and (ii) in the within-family sample of the SOEP were not enough individuals with information on IQ (n = 141).

Previous research has frequently focused on differences between first- and later-borns, instead of distinguishing between all birth positions within a given sibship size. To test the robustness of our results, we recoded birth order to distinguish between first- and later-borns and reran both the between- and within-family analyses. The results were in line with the results of our previous analyses: Firstborns scored slightly higher on intelligence and intellect, but we observed no differences in extraversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, or imagination (Table S7). One might also assume that middle children experience less uniform birth-order effects because their position within the family changes over time. We therefore reran the between-family analyses with only the first- and last-born individuals, again replicating previous analyses (Table S8).

Table S7.

Mean scores and results of between-family analyses (NCDS, NLSY and SOEP) and within-family analyses (NLSY and SOEP) comparing first- and later-borns

| Sibship size | Between-family | Within-family | |||||||||||

| n | Observed mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of sibship size | Effect of birth order | n | Estimated mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of birth order | |||||||

| Firstborn | Later-borns | F | P | F | P | Firstborn | Later-borns | F | P | ||||

| Extraversion | 2 | 8,964 | 49.92 | 50.23 | 2.30 | 0.129 | 1,354 | 49.81 | 49.93 | 0.05 | 0.821 | ||

| 3 | 5,497 | 50.15 | 50.42 | 0.93 | 0.334 | 861 | 49.34 | 48.97 | 0.28 | 0.595 | |||

| 4 | 2,569 | 50.87 | 49.72 | 7.24 | 0.007 | 375 | 49.92 | 50.13 | 0.04 | 0.835 | |||

| 17,030 | 1.12 | 0.327 | 0.60 | 0.437 | 2,590 | 0.01 | 0.939 | ||||||

| Emotional stability | 2 | 8,964 | 50.34 | 49.95 | 3.57 | 0.059 | 1,354 | 50.71 | 49.93 | 2.41 | 0.121 | ||

| 3 | 5,497 | 50.22 | 50.22 | 0.00 | 0.950 | 861 | 50.05 | 49.69 | 0.29 | 0.589 | |||

| 4 | 2,569 | 49.60 | 49.95 | 0.68 | 0.410 | 375 | 48.73 | 49.73 | 1.08 | 0.300 | |||

| 17,030 | 1.13 | 0.323 | 1.13 | 0.288 | 2,590 | 1.14 | 0.286 | ||||||

| Agreeableness | 2 | 8,964 | 49.97 | 49.93 | 0.04 | 0.852 | 1,354 | 49.51 | 50.19 | 2.07 | 0.151 | ||

| 3 | 5,497 | 50.05 | 50.34 | 1.10 | 0.294 | 861 | 50.57 | 50.32 | 0.17 | 0.685 | |||

| 4 | 2,569 | 50.10 | 50.28 | 0.17 | 0.683 | 375 | 48.22 | 50.08 | 3.01 | 0.084 | |||

| 17,030 | 1.45 | 0.234 | 0.41 | 0.521 | 2,590 | 2.22 | 0.136 | ||||||

| Conscientious-ness | 2 | 8,964 | 49.99 | 50.02 | 0.00 | 0.944 | 1,354 | 50.00 | 49.84 | 0.10 | 0.753 | ||

| 3 | 5,497 | 50.04 | 50.25 | 0.48 | 0.488 | 861 | 49.85 | 49.30 | 0.75 | 0.387 | |||

| 4 | 2,569 | 50.28 | 49.78 | 1.20 | 0.274 | 375 | 50.77 | 51.36 | 0.34 | 0.562 | |||

| 17,030 | 0.71 | 0.491 | 0.01 | 0.935 | 2,590 | 0.25 | 0.615 | ||||||

| Openness to experience | 2 | 8,964 | 50.48 | 50.12 | 3.17 | 0.075 | 1,354 | 50.31 | 50.19 | 0.05 | 0.817 | ||

| 3 | 5,497 | 50.79 | 50.35 | 2.47 | 0.116 | 861 | 49.97 | 48.90 | 2.98 | 0.085 | |||

| 4 | 2,569 | 49.85 | 49.53 | 0.52 | 0.469 | 375 | 49.42 | 50.48 | 1.15 | 0.284 | |||

| 17,030 | 6.78 | 0.001 | 6.06 | 0.014 | 2,590 | 0.55 | 0.460 | ||||||

| Imagination | 2 | 7,232 | 50.14 | 50.12 | 0.01 | 0.922 | 622 | 49.87 | 49.95 | 0.01 | 0.908 | ||

| 3 | 4,471 | 50.71 | 50.25 | 2.35 | 0.126 | 278 | 49.28 | 50.22 | 0.86 | 0.354 | |||

| 4 | 2,149 | 49.94 | 49.72 | 0.21 | 0.650 | 100 | 49.36 | 51.69 | 1.42 | 0.238 | |||

| 13,852 | 3.09 | 0.045 | 1.19 | 0.275 | 1,000 | 0.87 | 0.353 | ||||||

| Intellect | 2 | 7,232 | 51.01 | 50.01 | 19.43 | 0.000 | 622 | 51.45 | 49.54 | 7.31 | 0.007 | ||

| 3 | 4,471 | 50.94 | 50.05 | 8.60 | 0.003 | 278 | 50.53 | 48.80 | 2.65 | 0.105 | |||

| 4 | 2,149 | 50.02 | 49.30 | 2.25 | 0.134 | 100 | 52.35 | 51.03 | 0.55 | 0.460 | |||

| 13,852 | 6.42 | 0.002 | 29.68 | <0.001 | 1,000 | 10.55 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Intelligence (IQ) | 2 | 6,492 | 102.58 | 101.45 | 13.45 | <0.001 | 896 | 100.94 | 98.38 | 17.84 | <0.001 | ||

| 3 | 4,424 | 101.19 | 99.47 | 17.71 | <0.001 | 658 | 99.74 | 97.75 | 6.15 | 0.014 | |||

| 4 | 2,371 | 98.39 | 97.51 | 2.08 | 0.150 | 252 | 97.60 | 94.03 | 6.84 | 0.010 | |||

| 13,287 | 77.72 | <0.001 | 31.04 | <0.001 | 1,806 | 29.18 | <0.001 | ||||||

Table S8.

Mean scores and results of between-family analyses comparing first- and last-borns (NCDS, NLSY, and SOEP participants)

| Sibship size | n | Observed mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of sibship size | Effect of birth order | ||||

| Firstborn | Last-born | F | P | F | P | |||

| Extraversion | 2 | 8,964 | 49.92 | 50.23 | 2.30 | 0.129 | ||

| 3 | 3,686 | 50.15 | 50.42 | 0.93 | 0.334 | |||

| 4 | 1,253 | 50.87 | 49.72 | 7.24 | 0.007 | |||

| 13,903 | 1.12 | 0.327 | 0.60 | 0.437 | ||||

| Emotional stability | 2 | 8,964 | 50.34 | 49.95 | 3.57 | 0.059 | ||

| 3 | 3,686 | 50.22 | 50.22 | 0.00 | 0.950 | |||

| 4 | 1,253 | 49.60 | 49.95 | 0.68 | 0.410 | |||

| 13,903 | 1.13 | 0.323 | 1.13 | 0.288 | ||||

| Agreeableness | 2 | 8,964 | 49.97 | 49.93 | 0.04 | 0.852 | ||

| 3 | 3,686 | 50.05 | 50.34 | 1.10 | 0.294 | |||

| 4 | 1,253 | 50.10 | 50.28 | 0.17 | 0.683 | |||

| 13,903 | 1.45 | 0.234 | 0.41 | 0.521 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | 2 | 8,964 | 49.99 | 50.02 | 0.00 | 0.944 | ||

| 3 | 3,686 | 50.04 | 50.25 | 0.48 | 0.488 | |||

| 4 | 1,253 | 50.28 | 49.78 | 1.20 | 0.274 | |||

| 13,903 | 0.71 | 0.491 | 0.01 | 0.935 | ||||

| Openness to experience | 2 | 8,964 | 50.48 | 50.12 | 3.17 | 0.075 | ||

| 3 | 3,686 | 50.79 | 50.35 | 2.47 | 0.116 | |||

| 4 | 1,253 | 49.85 | 49.53 | 0.52 | 0.469 | |||

| 13,903 | 6.78 | 0.001 | 6.06 | 0.014 | ||||

| Imagination | 2 | 7,232 | 50.14 | 50.12 | 0.01 | 0.922 | ||

| 3 | 2,921 | 50.71 | 50.25 | 2.35 | 0.126 | |||

| 4 | 1,004 | 49.94 | 49.72 | 0.21 | 0.650 | |||

| 11,157 | 3.09 | 0.045 | 1.19 | 0.275 | ||||

| Intellect | 2 | 7,232 | 51.01 | 50.01 | 19.43 | <0.001 | ||

| 3 | 2,921 | 50.94 | 50.05 | 8.60 | 0.003 | |||

| 4 | 1,004 | 50.02 | 49.30 | 2.25 | 0.134 | |||

| 11,157 | 6.42 | 0.002 | 29.68 | <0.001 | ||||

| Intelligence (IQ) | 2 | 6,492 | 102.58 | 101.45 | 13.45 | <0.001 | ||

| 3 | 2,953 | 101.19 | 99.56 | 10.29 | 0.001 | |||

| 4 | 1,134 | 98.39 | 95.96 | 6.37 | 0.012 | |||

| 10,579 | 63.45 | <0.001 | 28.88 | <0.001 | ||||

Beer and Horn (32) suggested that prenatal hypomasculinization of later-born males might lead to specific birth-order effects in pairs of male siblings: Later-borns are expected to show more female traits. To rule out the possibility that mixed or female sibships obscure such effects, we separately analyzed sibships consisting of two sisters and two brothers. The between-family analyses revealed—besides the already identified birth-order effects on intelligence and intellect—only one significant effect on the Big Five personality traits. Second-born children in male sibships of two scored higher on conscientiousness than firstborns, but this effect was not found in the within-family analyses and went counter to the predictions made by the Family Niche Theory (see Table S9 for both analyses). We thus found no support for the notion that birth-order effects on personality would be more visible in male sibships.

Table S9.

Mean scores from sibships with two children of the same sex and results of the corresponding between and within-family analyses (NLSY and SOEP participants)

| Sex | Between-family | Within-family | |||||||||

| n | Observed mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of birth order | n | Estimated mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of birth order | ||||||

| Firstborn | Second-born | F | P | Firstborn | Second-born | F | P | ||||

| Extraversion | Male | 1,625 | 48.86 | 49.45 | 1.52 | 0.218 | 339 | 48.49 | 48.67 | 0.06 | 0.805 |

| Female | 1,755 | 50.83 | 51.50 | 1.91 | 0.167 | 318 | 50.83 | 51.15 | 0.09 | 0.760 | |

| Emotional stability | Male | 1,625 | 52.50 | 51.96 | 1.51 | 0.220 | 339 | 52.60 | 52.21 | 0.15 | 0.698 |

| Female | 1,755 | 47.93 | 48.63 | 2.09 | 0.148 | 318 | 49.21 | 47.81 | 2.22 | 0.139 | |

| Agreeableness | Male | 1,625 | 47.86 | 48.11 | 0.21 | 0.646 | 339 | 47.49 | 49.14 | 2.95 | 0.087 |

| Female | 1,755 | 51.90 | 51.90 | 0.00 | 0.997 | 318 | 51.97 | 51.70 | 0.09 | 0.764 | |

| Conscientiousness | Male | 1,625 | 48.47 | 49.82 | 7.88 | 0.005 | 339 | 48.82 | 48.49 | 0.11 | 0.739 |

| Female | 1,755 | 50.98 | 50.41 | 1.50 | 0.220 | 318 | 50.65 | 51.11 | 0.19 | 0.667 | |

| Openness to experience | Male | 1,625 | 49.78 | 49.82 | 0.02 | 0.899 | 339 | 51.11 | 50.87 | 0.07 | 0.799 |

| Female | 1,755 | 51.09 | 50.63 | 0.98 | 0.321 | 318 | 49.49 | 50.59 | 1.22 | 0.271 | |

| Imagination | Male | 1,225 | 49.17 | 49.57 | 0.53 | 0.468 | 169 | 50.22 | 49.95 | 0.04 | 0.835 |

| Female | 1,349 | 51.08 | 50.85 | 0.19 | 0.664 | 150 | 50.04 | 51.92 | 2.27 | 0.136 | |

| Intellect | Male | 1,225 | 50.85 | 49.92 | 2.95 | 0.086 | 169 | 52.55 | 51.24 | 0.95 | 0.332 |

| Female | 1,349 | 51.36 | 50.04 | 6.43 | 0.011 | 150 | 50.43 | 49.53 | 0.60 | 0.442 | |

| Intelligence (IQ) | Male | 739 | 102.05 | 99.28 | 6.95 | 0.009 | 224 | 99.89 | 97.28 | 3.93 | 0.050 |

| Female | 796 | 100.16 | 101.39 | 1.46 | 0.227 | 214 | 101.68 | 98.64 | 6.09 | 0.015 | |

The NCDS sample could not be included in this analysis because it was missing information on siblings’ sex. We did not present results for families with one male and one female sibling because birth-order effects would be confounded with gender effects in these analyses.

Finally, following the claim by Healey and Ellis (33) that selecting siblings with an age gap ranging from 1.5 to 5 y provides a better test of birth-order effects, we limited our analyses to sibships in which all age gaps between consecutive siblings fell within this range. Even though the sample sizes were still high in comparison with earlier studies—with >1,600 individuals in the within-family analyses and >5,600 individuals in the between-family analyses—we again found effects on only intelligence and openness, the latter completely attributable to the subdimension intellect (Table S10).

Table S10.

Mean scores and results of between and within-family analyses after restricting the analyses to families in which all age gaps between consecutive siblings were within the range of 18–60 mo (NLSY and SOEP participants)

| Sibship size | Between-family | Within-family | |||||||||||||||

| n | Observed mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of sibship size | Effect of birth order | n | Estimated mean scores by birth-order position | Effect of birth order | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F | P | F | P | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F | P | ||||

| Extraversion | 2 | 3,984 | 49.90 | 50.34 | 2.11 | 0.146 | 1,020 | 50.31 | 49.97 | 0.32 | 0.571 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,325 | 49.94 | 50.31 | 50.99 | 1.40 | 0.247 | 510 | 49.91 | 48.72 | 48.38 | 0.76 | 0.470 | |||||

| 4 | 358 | 50.77 | 49.62 | 51.09 | 50.35 | 0.35 | 0.791 | 145 | 51.53 | 50.57 | 48.03 | 50.06 | 0.48 | 0.694 | |||

| 5,667 | 0.04 | 0.959 | 1.65 | 0.175 | 1,675 | 0.81 | 0.487 | ||||||||||

| Emotional stability | 2 | 3,984 | 50.54 | 49.92 | 3.81 | 0.051 | 1,020 | 51.26 | 50.29 | 2.77 | 0.097 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,325 | 49.93 | 49.33 | 49.50 | 0.16 | 0.853 | 510 | 49.96 | 49.42 | 50.34 | 0.32 | 0.724 | |||||

| 4 | 358 | 51.07 | 50.65 | 48.79 | 50.74 | 0.92 | 0.432 | 145 | 47.88 | 51.99 | 52.94 | 54.10 | 1.60 | 0.196 | |||

| 5,667 | 1.25 | 0.287 | 1.75 | 0.154 | 1,675 | 0.88 | 0.452 | ||||||||||

| Agreeableness | 2 | 3,984 | 50.17 | 49.72 | 1.93 | 0.165 | 1,020 | 49.45 | 50.58 | 4.28 | 0.039 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,325 | 51.00 | 50.40 | 50.73 | 0.29 | 0.748 | 510 | 51.25 | 50.10 | 51.38 | 0.96 | 0.384 | |||||

| 4 | 358 | 51.89 | 49.96 | 50.21 | 49.15 | 1.23 | 0.300 | 145 | 50.96 | 51.38 | 49.72 | 46.50 | 0.35 | 0.791 | |||

| 5,667 | 3.10 | 0.045 | 1.62 | 0.182 | 1,675 | 0.86 | 0.459 | ||||||||||

| Conscien-tiousness | 2 | 3,984 | 49.81 | 49.79 | 0.00 | 0.966 | 1,020 | 49.84 | 49.84 | 0.00 | 0.997 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,325 | 50.20 | 50.23 | 50.53 | 0.13 | 0.882 | 510 | 49.17 | 48.78 | 48.77 | 0.07 | 0.931 | |||||

| 4 | 358 | 50.71 | 49.99 | 50.51 | 50.89 | 0.14 | 0.937 | 145 | 52.61 | 49.86 | 47.47 | 50.31 | 0.96 | 0.415 | |||

| 5,667 | 0.93 | 0.394 | 0.13 | 0.940 | 1,675 | 0.36 | 0.780 | ||||||||||

| Openness to experience | 2 | 3,984 | 50.74 | 49.94 | 6.71 | 0.010 | 1,020 | 49.94 | 49.87 | 0.02 | 0.893 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,325 | 50.80 | 49.96 | 50.35 | 0.63 | 0.534 | 510 | 51.34 | 49.57 | 49.23 | 2.24 | 0.108 | |||||

| 4 | 358 | 49.48 | 50.23 | 50.18 | 48.07 | 0.70 | 0.550 | 145 | 49.37 | 51.01 | 49.36 | 52.90 | 0.58 | 0.628 | |||

| 5,667 | 0.37 | 0.692 | 2.96 | 0.031 | 1,675 | 0.87 | 0.454 | ||||||||||

| Imagination | 2 | 3,020 | 50.49 | 49.98 | 1.95 | 0.163 | 452 | 49.41 | 48.94 | 0.30 | 0.585 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,021 | 50.62 | 49.80 | 50.35 | 0.62 | 0.536 | 151 | 50.06 | 50.16 | 49.87 | 0.03 | 0.970 | |||||

| 4 | 285 | 49.49 | 50.21 | 49.69 | 49.14 | 0.12 | 0.946 | 29 | 48.32 | 48.72 | 45.19 | 50.87 | 0.40 | 0.755 | |||

| 4,326 | 0.25 | 0.778 | 0.94 | 0.423 | 632 | 0.31 | 0.815 | ||||||||||

| Intellect | 2 | 3,020 | 51.16 | 49.57 | 20.45 | <0.001 | 452 | 51.38 | 49.56 | 4.88 | 0.028 | ||||||

| 3 | 1,021 | 50.49 | 49.64 | 50.09 | 0.63 | 0.533 | 151 | 51.07 | 47.56 | 47.30 | 2.42 | 0.096 | |||||

| 4 | 285 | 51.02 | 50.30 | 50.84 | 49.01 | 0.58 | 0.631 | 29 | 51.12 | 51.56 | 47.14 | 49.80 | 0.37 | 0.776 | |||

| 4,326 | 0.60 | 0.549 | 7.30 | <0.001 | 632 | 3.27 | 0.022 | ||||||||||

| Intelligence (IQ) | 2 | 1,921 | 102.94 | 100.77 | 11.66 | <0.001 | 688 | 101.83 | 98.78 | 19.62 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 3 | 623 | 101.92 | 97.65 | 101.08 | 4.65 | <0.001 | 410 | 102.43 | 100.49 | 98.74 | 1.88 | 0.155 | |||||

| 4 | 156 | 99.07 | 100.00 | 97.51 | 96.96 | 0.29 | 0.830 | 123 | 100.72 | 101.39 | 96.52 | 97.80 | 1.07 | 0.367 | |||

| 2,700 | 4.68 | <0.001 | 6.01 | <0.001 | 1,221 | 7.36 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

The NCDS sample could not be included in this analysis because it was missing information on the age gaps between siblings.

All in all, we did not find any effect of birth order on extraversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, or imagination, a subdimension of openness. There was a small, but significant, decline in self-reported intellect, a second subdimension of openness. The effect on intellect persisted after controlling for IQ scores, indicating that there is a genuine birth-order effect on intellect that goes beyond objectively measured intelligence and can be observed in adults.† Zajonc and Markus (7) proposed that older siblings profit intellectually from being “teachers” to their younger siblings—a process that might also account for differences in intellectual self-concept and -estimation when children internalize their roles as “teachers” or “students.” Social comparison (34) among siblings during childhood and adolescence might be another process that specifically contributes to differences in self-estimated intelligence: Individuals may evaluate their own intellectual abilities in relation to their siblings—and this evaluation may lead to favorable outcomes for firstborn children because of their developmental advantage. This comparison could cause a stable bias in self-estimations of intelligence, with later-born children slightly underestimating and firstborn children slightly overestimating their actual cognitive abilities. These ideas are compatible with a competitive niche partitioning theory within the family, where role differentiations and shared beliefs might lead to birth-order effects on self-rated intellect that go beyond objectively measured intelligence (11, 12). Another interesting issue supporting partially independent determinants of effects on IQ scores and intellect is the finding that increasing sibship size negatively influences only IQ scores, but not intellect (Table S2). It remains a promising issue for future research to disentangle common and unique sources that influence self-estimated and objectively measured intelligence within the family system.

Our results emerged consistently in all three panels included in this study—i.e., they were replicated across three different nations, across different measures of personality and intelligence, and by assessing individuals in early adulthood (NLSY), at age 50 (NCDS), and across the whole life span (SOEP). Furthermore, results were unaffected by the choice of analytical strategy, emerged consistently in the between- and within-family analyses and for both sexes, and were corroborated by the results of several control analyses. On a methodological note, the consistent effects found for intellect demonstrate that, not only IQ measures, but brief self-report measures are also generally sensitive to detecting birth-order effects when such effects indeed exist.

Thanks to our large sample size, we achieved a power of 95% with which to detect a mean difference as subtle as 5% of a SD between first- and later-borns in our between-family analyses of personality. Furthermore, a post hoc analysis revealed that we achieved a power of >99% with which to detect effects in the size of the typical IQ score difference of 1.5 points between first- and later-borns.

With regard to the high power and the consistent pattern of results, we must conclude that birth order does not have a meaningful and lasting effect on four of five of the broad personality domains and only partly on the fifth. Thus, with the exception of intellect, the central predictions of the Family Niche Theory with regard to personality could not be confirmed by our analyses. Of course, this general conclusion does not necessarily imply that there are no specific circumstances in which birth-order effects outside of the intellectual domain might emerge.

For example, Harris proposed that birth-order effects could be visible within the family, but might not affect behavior and relationships outside of this context (ref. 35; see also ref. 36). Furthermore, birth order might primarily or exclusively affect parts of the personality system that are not accessible to self-insight or that are masked by socially desirable responding in self-reports. This hypothesis can be addressed by using other reports (17, 18, 36) or behavioral observations of personality, both of which were not included in the panels used in our samples. Other research questions include whether birth-order effects emerge (i) only in larger sibships, which are now rare, such as the ones that Galton and Adler grew up in; (ii) only when investigated in more specific personality dimensions (e.g., sensation-seeking or risk-taking); or (iii) in different cultures (our analyses were based on data from industrialized nations of the Western world). However, the predictions made by the Family Niche Theory that we tested in this study were not limited to specific contexts and were based on mechanisms that were not restricted to specific cultures. Birth-order effects under the constraints named above would call for a refinement of the theoretical framework explaining their emergence.

To conclude, birth-order position seems to have only a small impact on who we become. Both the already-documented effect on objectively measured intelligence and the previously unidentified effect on self-reported intellect found in the present study were statistically significant, but small (at ∼10% of a SD), in terms of conventional effect sizes. Whether these differences among siblings matter at the individual level (e.g., despite the average decline in IQ, the second-born of a sibling dyad will still be smarter than his or her older sibling in 4 of 10 cases) is certainly a subject for further debate (see ref. 37 for arguments that these differences are important). The main message of this article, however, is crystal clear: On the basis of the high power and the consistent results found across samples and analyses, it can be concluded that birth order does not have a meaningful and lasting effect on broad Big Five personality traits outside of the intellectual domain.

Materials and Methods

Description of the Panels.

The NCDS (25, 26) originated from the Perinatal Mortality Survey 1958 and tracks the life courses of all individuals born in Great Britain in 1958 in a particular week. The study is managed by the Centre for Longitudinal Studies and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. The NLSY 97 (27) conducted by the US Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics consists of a representative sample of US residents born during the years 1980–1984. Data collection for this panel study began in 1997 and included all household members between 12 and 16 y of age from randomly selected households. The SOEP (28, 29) is a representative panel study of private households and their members in Germany. It began in 1984 and has since been refreshed several times to ensure representativity. The study is located at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin). Our study did not require ethical approval because we analyzed existing and fully anonymous data; informed consent was obtained from participants by the respective institutions.

Assessment of Birth Order and Sibship Size.

In each sample, a proxy for social birth position was derived from available information about siblings and household composition in youth. We decided to focus on the individual’s position among the children within the household instead of biological sibling status because the expected birth-order effects on personality are supposed to stem from social rather than biological processes. In most cases, however, social birth-order position equals biological birth-order position. Furthermore, we excluded participants who were only children because they cannot be compared with any siblings and are thus uninformative for the analysis of birth-order effects. We also decided to exclude twins because they grew up in a very specific sibling configuration that likely obscures the birth-order effects hypothesized by the Family Niche Theory. In particular, twins compete for resources and family niches not only with their older and/or younger siblings but also with their other twin of the same age. Participants from households with a sibship size exceeding four children also were not included in our analyses, because they represented <11% across the three samples and therefore did not enable reliable analyses of larger families. Table S1 shows the final sample sizes.

NCDS.

Birth-order position was derived from the parental questionnaires administered in 1965 and 1969. The respondent entered the total number of children in the household under the age of 21, as well as the target child’s position among these children. For all participants included in our analyses, information about household composition was available for both years of assessment. We equated the stated number of children in the household with the variable “sibship size” and the position among those children with “birth-order position” when there was no change in those variables between the target’s age of 7 and the age of 11. Whenever data from the two assessments indicated regular family dynamics (i.e., younger children “appearing” or older children “disappearing” between 1965 and 1969), we considered these changes when determining the “sibship size” and “birth-order position” by including both siblings who were newly born between 1965 and 1969 and older siblings who moved out between 1965 and 1969. Cases with data indicating patchwork-family dynamics (i.e., younger children disappearing from the household or older children appearing) were dropped from further analysis.

NLSY.

Birth-order position was derived from data on household members and nonresidential relatives gathered in 1997. All household members marked as full, half, step, or adoptive siblings living in the household of origin in 1997 were included in the computation of birth-order position. Nonresidential full siblings were also included as long as they were older than the target because it was likely that the target and said sibling had lived together previously. An age comparison was then used to determine the target’s birth-order position. Because all household members within the targeted age range of 12–16 y were interviewed, in some cases, we had data from two or more siblings from one family. Data on these siblings were used in our within-family analyses, and the other participants were used in our between-family analyses, hence ensuring that the within- and between-family datasets were completely nonoverlapping.

SOEP.

Birth-order position was derived from a number of questions about siblings included by the SOEP for the purpose of the present study and asked in 2013. Full, half, step, and adoptive siblings were counted toward sibship size as long as targets reported having spent the first 15 y in the same household. Targets who reported having spent at least 1 y, but fewer than 15 y, with one or more siblings were dropped to exclude patchwork families. An age comparison was then used to determine the target’s birth-order position. Because all household members are included in the SOEP after they turn 17, in some cases, we had data from two or more siblings from one family. Data from these siblings were used in our within-family analyses, and the other participants were used in our between-family analyses, hence ensuring that the within- and between-family datasets were completely nonoverlapping.

Assessment of Personality.

NCDS.

Personality was assessed in 2008 at age 50. Participants completed a set of 50 items from the international personality item pool (38) to measure the Big Five personality traits. Scales were computed if at least 9 of 10 items were answered for each of the five traits. We conducted a principal axis factor analysis with oblimin rotation on the 10 items, measuring openness to experience, extracting two correlated factors (r = 0.65). On the basis of the results of this factor analysis and supported by content-related considerations, we attained a five-item measure of self-reported intellect (“I use difficult words,” loadings on the two factors of 0.58/0.00; “I have a rich vocabulary,” 0.55/0.07 ; “I am quick to understand things,” 0.32/0.23; and, reverse-coded: “I have difficulty understanding abstract ideas,” 0.68/0.04; “I am not interested in abstract ideas,” 0.60/0.00) and a five-item measure of imagination (“I am full of ideas,” −0.01/0.74; “I have excellent ideas,” −0.03/0.71; “I have a vivid imagination,” 0.05/0.48; “I spend time reflecting on things,” 0.05/0.22; and, reverse-coded: “I do not have a good imagination,” 0.10/0.45). Last, we generated two measures, each consisting of two items from the emotional stability scale on which firstborns (“I get upset easily” and “I get irritated easily”) and later-borns (“I often feel blue,” and, reverse-coded: “I seldom feel blue”) were hypothesized to score higher according to Sulloway (15). All scores were converted into T scores (M = 50; SD = 10) on the basis of the NCDS sample.

NLSY.

Personality was assessed in 2009 (age 29–35). Participants completed the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (39) consisting of two items for each Big Five dimension. Scales were computed if no items were missing. The item “I see myself as: anxious, easily upset” from the emotional stability scale was furthermore analyzed separately to test Sulloway’s hypothesis that firstborns score higher on this specific item (15). The two items used to measure openness to experience in the NLSY—“I see myself as: open to new experiences, complex” and “…conventional, uncreative”—could not be decomposed any further because they both measure the imaginative component of openness. To control for potential nonlinear age effects, we locally regressed each of the Big Five traits as well as the specific item on age in the NLSY sample, by using the LOWESS procedure with a bandwidth of 0.5. We then converted the residuals from these regressions into T-scores, which reflect personality scores after adjusting them for normative age trends.

SOEP.

Personality was assessed in 2013 (age 18–98). Participants completed a version of the BFI-S (40) containing 16 items, including 4 items for openness and 3 for each of the remaining Big Five personality traits. We split the items measuring openness to attain a three-item measure of imagination (“I am someone who… is original, comes up with new ideas,” “…values artistic, aesthetic experiences,” and “…has an active imagination”), and used the fourth item as a measure of intellect (“…is eager for knowledge”). Scales were computed if no items were missing. Local regression was used to attain age-adjusted T-scores as described for the NLSY.

Assessment of Intelligence.

NCDS.

Intelligence was assessed in 1969 (age 11). The children were individually tested by teachers with a General Ability Test consisting of 40 verbal and 40 nonverbal items (41). We generated IQ scores (M = 100; SD = 15) from the sums of the scores of the two subtests.

NLSY.

Intelligence was assessed in 1997 and 1998. Respondents participated in the computer-adaptive form of the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (42). We calculated IQ scores from the age-sensitive summary percentile score using 59 items. The resulting scores had a slightly lower mean (M = 98.44) because the calibration sample tended to score higher than the NLSY97 sample.

SOEP.

Intelligence was assessed in 2013 with the MWT-B, a multiple-choice vocabulary test with 37 items (43). Using the same local regression procedure as used for the NLSY and SOEP personality scores, we calculated age-adjusted IQ scores from the number of correct answers.

Statistical Models.

Between-family analyses.

We ran separate ordinary least-squares regression analyses for each of the personality dimensions and intelligence. Three factor variables were entered into the model as predictors: birth-order position, sibship size, and data source. Birth-order position was coded in a way that distinguished between each position within a sibship from firstborn to fourth-born and was represented in the model by three dummy variables. This way, we were able to estimate the unique effect of each position on personality rather than only the overall linear effect. Similarly, sibship size (two to four) and data source (NCDS, NLYS, SOEP) were each represented by two dummy variables. We decided to report the results of aggregated analyses in the main table to (i) attain a number of results that would be easier to communicate, (ii) increase the power of the analyses and, (iii) prevent alpha accumulation. However, aggregating individuals from different sibship sizes also had the potential to be problematic: (i) The design inherently comprised empty cells—for example, there was no third-born in a family with only two children—and (ii) our coding was based on the assumption that, for example, second-born children in a family of two fall into the same birth-order category as second-born children in a family of three. To avoid these problems, we also analyzed birth-order effects separately for each sibship size.

Within-family analyses.

We ran fixed-effects regression models (44) to estimate within-family birth-order effects separately for each of the personality dimensions and intelligence. Birth-order position was entered as a factor variable, coded as described for the between-family analyses. Additional factor variables to control for data source and sibship size were not necessary: The fixed-effects regression estimates the within-effects by comparing only individuals from within a family who share their sibship size and are part of the same panel study.

Acknowledgments

The National Child Development Study (NCDS) data were made available by the Centre for Longitudinal Studies at the Institute of Education, University of London, and the UK Data Service. The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) data were made available by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) data were made available by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW). We thank these institutions for providing these datasets.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: All data used in this study are publicly available to scientific researchers. The NCDS data are available from the UK Data Service, ukdataservice.ac.uk; the NLSY97 data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.bls.gov/nls; and the SOEP data from the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), www.diw.de/en/soep. To achieve full transparency and to allow the reproducibility of our analyses, the scripts for replicating our data analysis are archived in the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/m2r3a.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. C.F.C. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

*Sulloway postulated an opposing effect of birth order on dominance as a facet of extraversion (15). However, because the extraversion items in the questionnaires used in this study did not include the dominance facet, we were unable to test this additional hypothesis.

†Parental age might be a potential confounding variable that is causing the effects on intelligence and intellect. For example, a higher paternal age at conception carries the risk of a higher number of new genetic mutations that might lower intelligence in later-borns. Assuming this kind of process, one would expect that spurious birth-order effects caused by differences in parental age would become larger with increasing age gaps between siblings. We tested this possibility by including the difference in age between the target person and firstborn as an additional predictor in our between- and within-family analyses of intelligence and intellect. Age differences did not significantly explain any variance above and beyond birth-order position in any of these four analyses (all P > 0.52). This result suggests that parental age is not the driving force behind the effects on intelligence and intellect.

See Commentary on page 14119.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1506451112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Galton F. English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture. Thoemmes; Bristol, UK: 1874. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler A. Characteristics of the first, second and third child. Children. 1928;3(5):14–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belmont L, Marolla FA. Birth order, family size, and intelligence. Science. 1973;182(4117):1096–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4117.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breland HM. Birth order, family configuration, and verbal achievement. Child Dev. 1974;45(4):1011–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjerkedal T, Kristensen P, Skjeret GA, Brevik JI. Intelligence test scores and birth order among young Norwegian men (conscripts) analyzed within and between families. Intelligence. 2007;35(5):503–514. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barclay KJ. A within-family analysis of birth order and intelligence using population conscription data on Swedish men. Intelligence. 2015;49(2):134–143. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zajonc RB, Markus GB. Birth order and intellectual development. Psychol Rev. 1975;82(1):74–88. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristensen P, Bjerkedal T. Explaining the relation between birth order and intelligence. Science. 2007;316(5832):1717. doi: 10.1126/science.1141493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst C, Angst J. Birth Order: Its Influence on Personality. Springer; Berlin: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schooler C. Birth order effects: Not here, not now. Psychol Bull. 1972;78(3):161–175. doi: 10.1037/h0033026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sulloway FJ. Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives. Vintage; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sulloway FJ. Why siblings are like Darwin’s finches: Birth order, sibling competition and adaptive divergence within the family. In: Buss DM, Hawley PH, editors. The Evolution of Personality and Individual Differences. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2010. pp. 87–119. [Google Scholar]

- 13.John OP, Naumann LP, Soto CJ. Paradigm shift to the integrative Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In: John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. Guilford; New York: 2008. pp. 114–158. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostendorf F, Angleitner A. Reflections on different labels for Factor V. Eur J Pers. 1994;8(4):341–349. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulloway FJ. Birth order. In: Runco MA, Pritzker SR, editors. Encyclopedia of Creativity. Academic; San Diego: 1999. pp. 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Townsend F. Birth order and rebelliousness: Reconstructing the research in “Born to Rebel”. Politics Life Sci. 2000;19(2):135–156. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulhus DL, Trapnell PD, Chen D. Birth order effects on personality and achievement within families. Psychol Sci. 1999;10(6):482–488. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jefferson T, Herbst JH, McCrae RR. Associations between birth order and personality traits: Evidence from self-reports and observer ratings. J Res Pers. 1998;32(4):498–509. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker WD. Birth-order effects in the academically talented. Gift Child Q. 1998;42(1):29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalski RL, Shackelford TK. An attempted replication of the relationships between birth order and personality. J Res Pers. 2002;36(2):182–188. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bleske-Rechek A, Kelley JA. Birth order and personality: A within-family test using independent self-reports from both firstborn and laterborn siblings. Pers Individ Dif. 2014;56:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damian RI, Roberts BW. The associations of birth order with personality and intelligence in a representative sample of U.S. high school students. J Res Pers. 2015;58:96–105. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paulhus DL. Birth order. In: Haith MM, Benson JB, editors. Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development. Academic; Amsterdam: 2008. pp. 204–211. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrera NC, Zajonc RB, Wieczorkowska G, Cichomski B. Beliefs about birth rank and their reflection in reality. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(1):142–150. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University of London 2008. National Child Development Study: Childhood Data, Sweeps 0-3, 1958–1974 (UK Data Archive, Colchester, Essex, UK)

- 26.Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University of London 2010. National Child Development Study, Sweep 8, 2008–2009 (UK Data Archive, Colchester, Essex, UK)

- 27.Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor 2013. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), 1997 cohort, 1997–2011 (rounds 1–15) (Center for Human Resource Research, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH)

- 28.Wagner GG, Frick JR, Schupp J. The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP): Evolution, scope and enhancements. J Appl Soc Sci Stud. 2007;127(1):139–169. [Google Scholar]

- 29.German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) 2014. Socio-Economic Panel, Data for Years 1984-2013 (DIW/SOEP, Berlin), Version 30 beta.

- 30.Specht J, Egloff B, Schmukle SC. Stability and change of personality across the life course: The impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the Big Five. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101(4):862–882. doi: 10.1037/a0024950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freund PA, Kasten N. How smart do you think you are? A meta-analysis on the validity of self-estimates of cognitive ability. Psychol Bull. 2012;138(2):296–321. doi: 10.1037/a0026556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beer JM, Horn JM. The influence of rearing order on personality development within two adoption cohorts. J Pers. 2000;68(4):789–819. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Healey MD, Ellis BJ. Birth order, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. Evol Hum Behav. 2007;28(1):55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat. 1954;7(2):117–140. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris JR. Context-specific learning, personality, and birth order. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2000;9(5):174–177. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marini VA, Kurtz JE. Birth order differences in normal personality traits: Perspectives from within and outside the family. Pers Individ Dif. 2011;51(8):910–914. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sulloway FJ. Psychology. Birth order and intelligence. Science. 2007;316(5832):1711–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1144749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldberg LR, et al. The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. J Res Pers. 2006;40(1):84–96. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, Swann WB. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J Res Pers. 2003;37(6):504–528. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lang FR, John D, Lüdtke O, Schupp J, Wagner GG. Short assessment of the Big Five: Robust across survey methods except telephone interviewing. Behav Res Methods. 2011;43(2):548–567. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0066-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shepherd P. 1958 National Child Development Study: Measures of Ability at Ages 7 to 16. Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University of London; London: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sands WA, Waters BK, McBride JR. Computerized Adaptive Testing: From Inquiry to Operation. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lehrl S, Triebig G, Fischer B. Multiple choice vocabulary test MWT as a valid and short test to estimate premorbid intelligence. Acta Neurol Scand. 1995;91(5):335–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1995.tb07018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allison PD. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Sage; Los Angeles: 2009. [Google Scholar]