Significance

The host launches an antimicrobial defense program upon infection. A long-held belief is that pathogens prevent host recognition by remodeling their surface in response to different host microenvironments. Yet direct evidence that this happens in vivo is lacking. Here we report that the pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae modifies one of its surface molecules, the lipopolysaccharide, in the lungs of mice to evade immune surveillance. These in vivo-induced changes are lost in bacteria grown after isolation from the tissues. These lipopolysaccharide modifications contribute to survival in vivo and mediate resistance to colistin, one of the last options to treat multidrug-resistant Klebsiella. This work opens the possibility of designing novel therapeutics targeting the enzymes responsible for the in vivo lipid A pattern.

Keywords: lipid A, Klebsiella, colistin, LpxO, PhoPQ

Abstract

The outcome of an infection depends on host recognition of the pathogen, hence leading to the activation of signaling pathways controlling defense responses. A long-held belief is that the modification of the lipid A moiety of the lipopolysaccharide could help Gram-negative pathogens to evade innate immunity. However, direct evidence that this happens in vivo is lacking. Here we report the lipid A expressed in the tissues of infected mice by the human pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae. Our findings demonstrate that Klebsiella remodels its lipid A in a tissue-dependent manner. Lipid A species found in the lungs are consistent with a 2-hydroxyacyl-modified lipid A dependent on the PhoPQ-regulated oxygenase LpxO. The in vivo lipid A pattern is lost in minimally passaged bacteria isolated from the tissues. LpxO-dependent modification reduces the activation of inflammatory responses and mediates resistance to antimicrobial peptides. An lpxO mutant is attenuated in vivo thereby highlighting the importance of this lipid A modification in Klebsiella infection biology. Colistin, one of the last options to treat multidrug-resistant Klebsiella infections, triggers the in vivo lipid A pattern. Moreover, colistin-resistant isolates already express the in vivo lipid A pattern. In these isolates, LpxO-dependent lipid A modification mediates resistance to colistin. Deciphering the lipid A expressed in vivo opens the possibility of designing novel therapeutics targeting the enzymes responsible for the in vivo lipid A pattern.

The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) contains a molecular pattern recognized by the innate immune system thereby initiating host defense responses. Innate host identification of lipid A relies on the inability of bacteria to alter this component dramatically. The canonical lipid A structure activating innate LPS receptors is expressed by Escherichia coli K12 and consists of a β(1′–6)-linked disaccharide of glucosamine phosphorylated at the 1 and 4′ positions, with positions 2, 3, 2′, and 3′ acylated with R-3-hydroxymyristoyl groups (3-OH-C14). The 2′ and 3′ R-3-hydroxymyristoyl groups are acylated with laureate (C12) and myristate (C14) by the action of the acyltransferases LpxL and LpxM, respectively (1). Although the enzymes required to synthesize lipid A are conserved throughout all Gram-negative bacteria, there is heterogeneity of the lipid A structure among Gram-negative bacteria. This is due to differences in the type and length of fatty acids, in the presence of chemical moieties, or even in the removal of groups such as phosphates or fatty acids from lipid A (1–3). Well-characterized modifications include the addition of phosphoethanolamine (4), 4-aminoarabinose (5), palmitate (6), and hydroxylation by the Fe2+/α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase enzyme (LpxO) (7–9).

In vitro evidence demonstrates that increased natural diversity or heterogeneity within lipid A can produce dramatic host responses. It has been hypothesized that modification of lipid A in response to different host microenvironments helps pathogens to survive in the hostile host by camouflaging the pathogen from host immune detection, promoting antimicrobial peptide resistance and by altering outer membrane properties (3, 10, 11). However, direct evidence showing that bacteria remodel their lipid A in vivo is lacking.

Here, we set out to determine lipid A expressed in vivo by Klebsiella pneumoniae. This pathogen has been singled out by the World Health Organization as a public health threat due to the emergence of drug-resistant strains. Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates are responsible for high rates of morbidity and mortality and they represent a major therapeutic challenge, especially when the isolates are also resistant to colistin, which is the last-line antibiotic for treating K. pneumoniae infections (12). The evidence presented in this article demonstrates that Gram-negative bacteria do remodel their lipid A in vivo and that these in vivo-induced lipid A changes contribute to virulence by counteracting innate immune defenses.

Results

Analysis of K. pneumoniae Lipid A in Vivo.

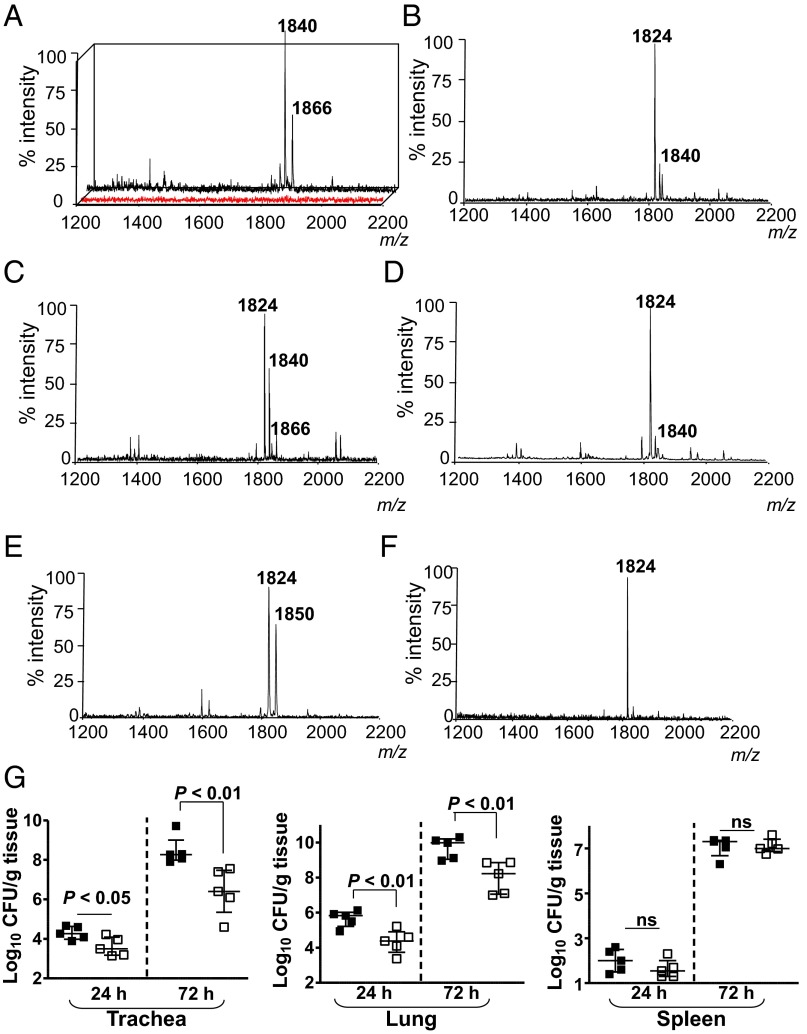

To determine the lipid A expressed in vivo by wild-type K. pneumoniae 52145 (hereafter Kp52145), mice were infected intranasally, and lipid A was extracted from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) using an ammonium hydroxide/isobutyric acid method and subjected to negative ion matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry analysis (13).The number of bacteria recovered from the lungs of infected mice was between 106 and 107 cfu per gram of tissue at 24 h postinfection. In BALFs from PBS mock-infected mice, the background noise was between 5 and 100 arbitrary units, which corresponds to an overall detection limit at a relative abundance of approximately 10% (Fig. 1A; red spectrum). Two ions of mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) 1,840 and m/z 1,866 were detected in BALFs from infected mice (Fig. 1A). Similar ions were detected when lipid A was extracted using the TRI Reagent method (14) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), when lung homogenates were analyzed (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), and at 48 h postinfection (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Consistent with previous reports (15, 16), the lipid A extracted from Kp52145 grown in lysogeny broth (LB) contained the hexaacylated species m/z 1,824 corresponding to two glucosamines, two phosphates, four R-3-hydroxymyristoyl primary acyl chains, and two myristates (C14) as secondary acyl chains (Figs. 1B and 2). The other peak (m/z 1,840) may represent a hexaacylated lipid A containing two glucosamines, two phosphates, four R-3-hydroxymyristoyl primary acyl chains, one myristate (C14), and one 2-hydroxymyristate (C14:OH) (Figs. 1B and 2). The lipid A of bacteria isolated from the lung homogenates was not exactly the same as that found in vivo (Fig. 1C), whereas the lipid A of bacteria passaged twice on LB agar plates (Fig. 1D) was identical to the lipid A from Kp52145 grown in LB (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of K. pneumoniae lipid A in vivo. Negative ion MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry spectra from: (A) BALF obtained from mock-infected animals (red spectrum) or Kp52145-infected mice (black spectrum); (B) Kp52145 grown in LB; (C) from bacteria recovered after plating the infected lung homogenate in LB agar plates for 24 h at 37 °C; (D) bacteria recovered after second passage of bacteria isolated from infected lung homogenate; (E) BALF obtained from lpxO-infected mice; (F) lpxO mutant grown in LB; and (G) bacterial loads in the tissues of infected mice (n = 5 per time point and strain). Kp52145, black symbols; 52145-ΔlpxO, white symbols. Results are reported as log colony-forming units per gram of tissue (log cfu/g). ns, not significant (P > 0.05; one-tailed t test). In A and E, results are representative of five indepedent extractions; in B–D and F, results are representative of extractions from 10 infected animals.

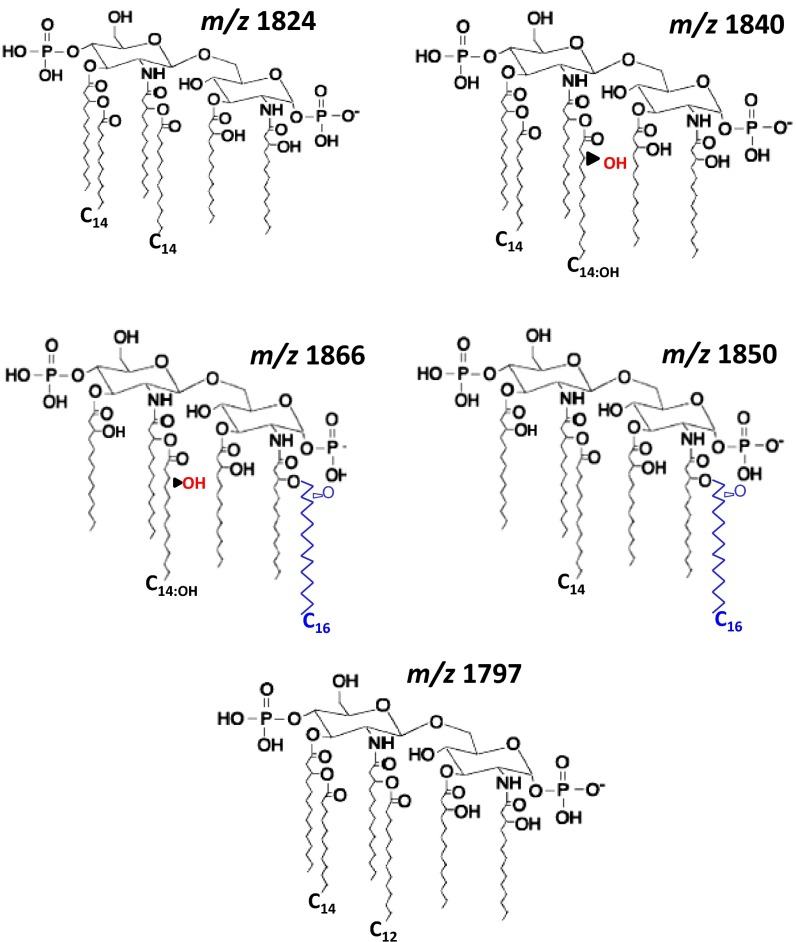

Fig. 2.

Proposed lipid A chemical structures. Proposed structures follow previously reported structures for Klebsiella (15, 16, 21) and other Gram-negative bacteria.

Species m/z 1,866, not detected in the lipid A from Klebsiella grown in LB, has been previously found in the lipid A from a K. pneumoniae lpxM mutant (16). Klebsiella LpxM catalyzes the addition of myristate (C14) to the 3′ R-3-hydroxymyristoyl (16). As expected, the lipid A species detected in the Kp52145 lpxM mutant grown in LB were m/z 1,614 and m/z 1,630, which are consistent with the lack of myristate (C14) from species m/z 1,824 and m/z 1,840, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). Other ions detected were m/z 1,850 and m/z 1,866 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A and Fig. 2), which are consistent with the addition of palmitate (C16) (m/z 239) to ions m/z 1,614 and m/z 1,630, respectively. Peaks m/z 1,630 and m/z 1,866 were detected in the lipid A extracted from lung homogenates of mice infected with the lpxM mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). PagP is the acyltransferase responsible for adding palmitate to Klebsiella lipid A (15). As anticipated, the lipid A species detected in the double mutant pagP-lpxM grown in LB lacked palmitate (C16) and the species detected, m/z 1,614 and m/z 1,630, are consistent with four R-3-hydroxymyristoyl primary acyl chains, and either one myristate (C14) or one 2-hydroxymyristate (C14:OH), respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C).

A hallmark of K. pneumoniae lipid A expressed in vivo was the presence of 2-hydroxymyristate (C14:OH). The presence of 2-hydroxyl fatty acids in the lipid A has been reported for Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium (C14:OH) (5, 7, 8), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (C12:OH) (17), and Bordetella spp. (C12:OH) (18, 19). LpxO has been identified as the oxygenase that 2-hydroxylates the C14 or C12 acyl chains. In silico analysis of the available K. pneumoniae genomes revealed the presence of an ortholog of Salmonella LpxO (64% identity, locus tag BN49_1127 Kp52145 genome), which could generate the 2-hydroxymyristate found in the lipid A. Confirming our prediction, the lipid A extracted from lung homogenates of mice infected with the lpxO mutant, strain 52145-ΔlpxO, lacked the ions containing 2-hydroxymyristate (C14:OH) (m/z 1,840 and m/z 1,866) and, instead, contained ions m/z 1,824 and m/z 1,850, a m/z difference of 16 from ions m/z 1,840 and m/z 1,866, respectively (Fig. 1E). The 52145-ΔlpxO lipid A lacked the ion m/z 1,840 when the mutant was grown in LB (Fig. 1F). Complementation of lpxO restored the m/z 1,840 species in the lipid A of 52145-ΔlpxO grown in LB (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A).

To test the importance of LpxO-dependent lipid A modification in K. pneumoniae virulence, we evaluated the ability of 52145-ΔlpxO to cause pneumonia. Mice were infected intranasally and the bacterial loads in trachea, lung, and spleen homogenates were determined at 24 and 72 h postinfection (Fig. 1G). Bacterial loads of the mutant strain were lower than those of the wild type in both the trachea and the lung (Fig. 1G). In contrast, no significant differences were found in the spleen (Fig. 1G). Interestingly, species lacking the 2-hydroxylated fatty acid, m/z 1,824 and m/z 1,797, were detected in the lipid A extracted from spleen homogenates (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D). Ion m/z 1,797 has been previously detected in Klebsiella lipid A and is consistent with two glucosamines, two phosphates, four R-3-hydroxymyristoyl primary acyl chains, and one myristate (C14) and one laureate (C12) as the secondary acyl chains (Fig. 2) (15, 16, 20, 21).

We were keen to find in vitro conditions in which Kp52145 produces a similar lipid A pattern to that found in the lungs of infected mice. Several growth conditions were tested (SI Appendix, Table S1), but only when Kp52145 was grown in M9 minimal medium with low magnesium concentration (pH 4.5) the lipid A pattern resembled that found in vivo (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). We termed this medium in vivo minimal medium (VMM). Lipid A extracted from lpxM and lpxO mutants grown in VMM contained similar species to those observed in vivo for these mutants (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D). Complementation of lpxO restored species m/z 1,840 and m/z 1,866 in the lipid A of 52145-ΔlpxO grown in VMM (SI Appendix, Fig. S3E).

LpxO Characterization.

The fact that the lipid A from the lpxM mutant contained 2-hydroxymyristate both in vivo and in vitro (m/z 1,630 and m/z 1,866) strongly suggests that Klebsiella LpxO (KpLpxO) hydroxylates the myristate (C14) on the primary 2′-linked R-3-hydroxymyristoyl group. Mass spectrometry analysis has previously shown that the nonreducing glucosamine of Klebsiella lipid A is substituted with only one (amide-linked) R-3-hydroxymyristoyl group further acylated with myristate (C14) or 2-hydroxymyristate (C14:OH) (20, 21). In good agreement, we show that KpLpxO hydroxylated Yersinia enterocolitica O:8 myristate (C14) on the primary 2′-linked R-3-hydroxymyristoyl group (peaks m/z 1,404 and m/z 1,813; SI Appendix, Fig. S4C) but not the 3′-linked E. coli C14 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). In contrast, and as reported previously (7, 8), Salmonella typhimurium LpxO (StLpxO) hydroxylated the 3′-linked E. coli C14 (peak m/z 1,813) but not Y. enterocolitica O:8 secondary acyl chains (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 E and F). Neither Y. enterocolitca O:8 nor E. coli K12 encodes an lpxO ortholog and their lipid As do not contain 2-hydroxyl fatty acids.

Transmembrane helix prediction analysis for the KpLpxO sequence predicts two transmembrane helices (one at each end of the protein) with a central domain (amino acids 19–279) containing the active site, which likely faces the cytoplasm. To find catalytically important residues, amino acids 35–236 were modeled based on the crystal structure of human Asp/Asnβ-hydroxylase (Protein Data Bank, PDB code 3RCQ) and the multiple sequence alignment shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5A. These residues were then compared with the known catalytically important residues in bovine Asp/Asnβ-hydroxylase (22), which shares ∼75% identity to human Asp/Asnβ-hydroxylase. The resulting model predicts that KpLpxO has the Asp/Asnβ-hydroxylase fold, with a typical iron-binding motif, H-X-D-X∼50-H (H155-R-D-X44-H202 in KpLpxO), in the active site cavity (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The active site residues (within 4 Å from the cavity) of KpLpxO are conserved in the multiple sequence alignment (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). To confirm that these residues are important for LpxO activity, we constructed several LpxO FLAG-tagged mutants where the conserved residues are substituted by alanine (SI Appendix, Table S2). In contrast to wild-type LpxO FLAG tagged, none of the LpxO mutants restored the presence of m/z 1,840 and m/z 1,866 in the lipid A of the lpxO mutant grown in VMM (SI Appendix, Table S2). Western blot analysis confirmed that the mutant proteins were expressed (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Taken together, our data show that the 3D fold of KpLpxO likely resembles that of human Asp/Asnβ-hydroxylase and that the active site of KpLpxO is similar to that of bovine Asp/Asnβ-hydroxylase.

Regulation of in Vivo Lipid A Pattern.

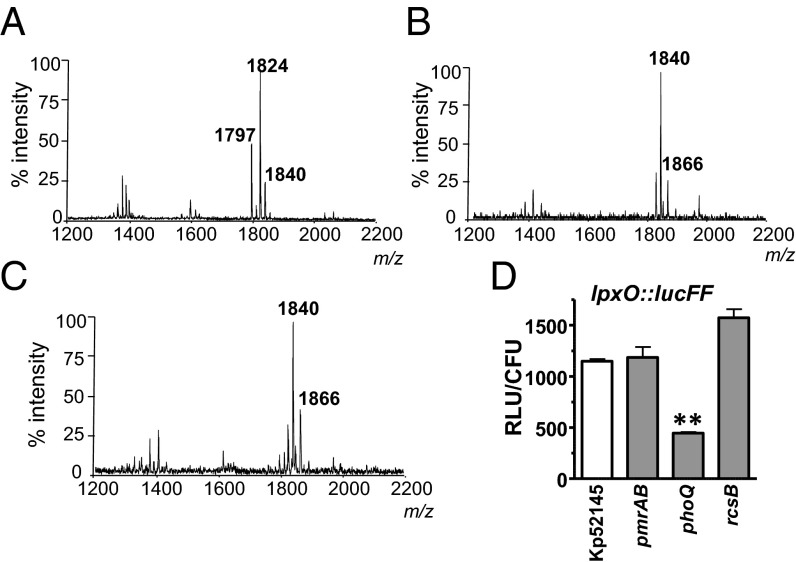

We sought to determine the signaling networks responsible for the lipid A pattern found in vivo. We have previously shown that the PhoPQ, PmrAB, and Rcs systems control the loci necessary for lipid A remodeling in K. pneumoniae (15). We asked whether any of these systems may control the K. pneumoniae lipid A pattern in vivo. Mass spectrometry analysis revealed that lipid A extracted from lung homogenates of mice infected with the phoQ mutant lacked the ion m/z 1,866 (Fig. 3A) and the other ions detected, m/z 1,824 and m/z 1,797, were not found in lung homogenates from mice infected with the wild type (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). In contrast, the lipid A extracted from mice infected with either the pmrAB (Fig. 3B) or rcsB (Fig. 3C) mutants was similar to that of the wild type, thereby suggesting that PhoPQ plays a major role in regulating K. pneumoniae lipid A plasticity in vivo. PhoPQ also regulated the lipid A pattern of K. pneumoniae cultured in VMM (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Complementation of the phoQ mutant restored the lipid A profile to that of the wild-type strain when cultured in VMM (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B).

Fig. 3.

PhoPQ controls K. pneumoniae lipid A plasticity in vivo. Negative ion MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry spectra from lung homogenates of mice infected with: (A) 52145-ΔphoQGB; (B) 52145-ΔpmrAB; and (C) 52145-ΔrcsB mutants. (D) Luminescence was determined in the lung homogenates of infected mice (five mice per strain) 24 h postinfection and corrected by the number of colony-forming units. Mice were infected with Kp52145, 52145-ΔphoQGB (phoQ), 52145-ΔpmrAB (pmrAB), and 52145-ΔrcsB (rcsB) carrying the transcriptional fusion lpxO::lucFF. Results are significantly different (**P < 0.01; one-tailed t test) from the results for Kp52145. In A–C, results are representative from extractions from five infected animals.

To monitor whether PhoPQ controls lpxO expression in vivo, we constructed a transcriptional fusion in which a promoterless firefly luciferase gene (lucFF) was under the control of the lpxO promoter region; the lpxO::lucFF fusion was then introduced into K. pneumoniae strains. Mice were intranasally infected with the reporter strains and the luciferase activity in lung homogenates was measured. Luminescence was lower in lung homogenates from mice infected with the phoQ mutant than in those infected with the wild-type strain or any of the other regulatory mutants (Fig. 3D). PhoPQ also controlled the expression of lpxO in vitro because the VMM-induced increase in lpxO::lucFF activity was only observed in the wild type and not in the phoQ mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). Similar results were obtained when the lpxO mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). The activity of the transcriptional fusion phoP::lucFF and phoP mRNA levels were also up-regulated in a PhoPQ-dependent manner by growing Kp52145 in VMM (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 C and D). Complementation of the phoQ mutant restored the activities of the transcriptional fusions lpxO::lucFF and phoP::lucFF to wild-type levels. Similar results were obtained when the lpxO and phoP mRNA levels were analyzed (SI Appendix, Fig. S9).

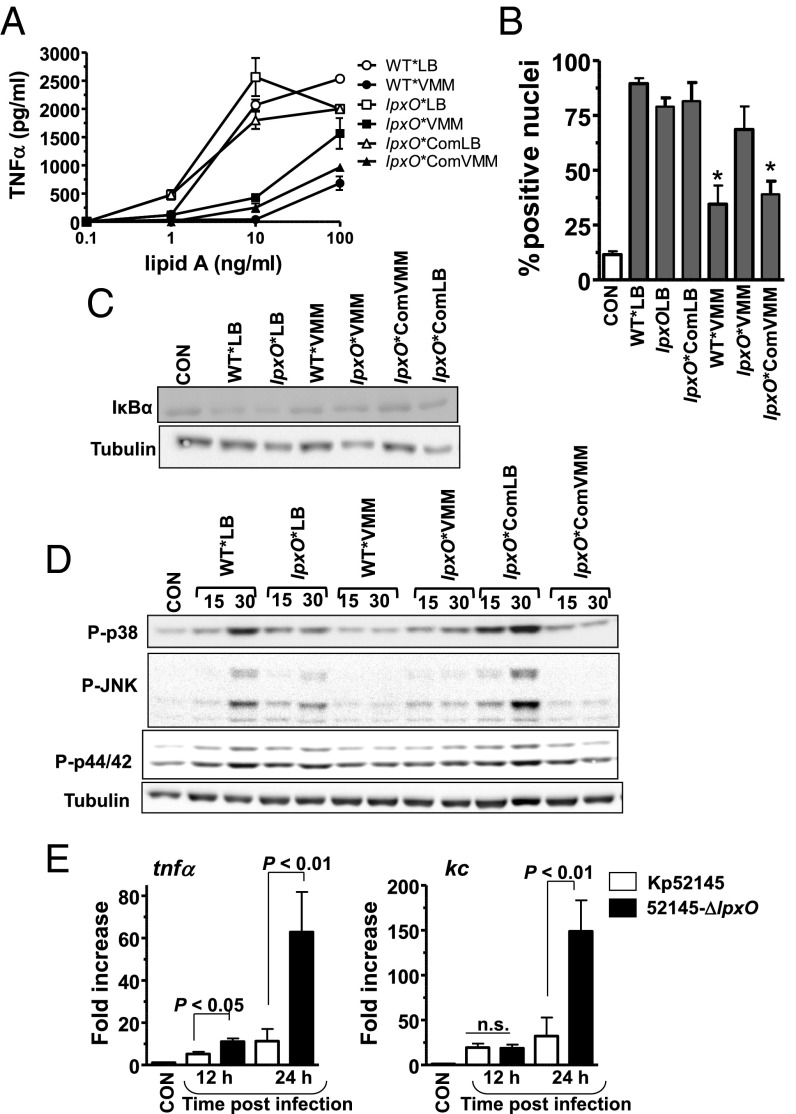

Klebsiella in Vivo Lipid A Pattern and Inflammatory Responses.

Next, we investigated the ability of the lipid A pattern found in vivo to stimulate inflammatory responses. For these experiments, lipid A was purified from Kp52145 and 52145-ΔlpxO isogenic capsule mutants (hereafter WT* and lpxO*, respectively) to avoid the copurification of the capsule polysaccharide with the LPS (23). Lipid A was also purified from the lpxO complemented strain (52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxOCom; lpxO*Com). Lipid As were purified from bacteria grown in LB or VMM. WT*VMM lipid A stimulated less TNFα secretion by macrophages than WT*LB lipid A (P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA), which induced similar levels of TNFα than lpxO*LB (P > 0.05; one-way ANOVA). lpxO*VMM lipid A induced more TNFα than lipid A from WT*VMM (P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 4A). TNFα levels induced by lipid A from lpxO*ComVMM were not signifcantly different from those induced by lipid A from WT*VMM (Fig. 4A) (P > 0.05; one-way ANOVA). We next assessed the activation of the NF-κB signaling cascade in macrophages challenged with the different lipid As. Immunolocalization of the NF-κB p65 subunit in macrophages revealed that the number of positive nuclei was significantly lower in cells challenged with WT*VMM lipid A than in those challenged with WT*LB or lpxO*VMM lipid As, which were not significantly different (P > 0.05, one-tailed t test; Fig. 4B). No significant differences were observed between cells challenged with lipid A from WT*VMM or from lpxO*ComVMM (P > 0.05, one-tailed t test; Fig. 4B). In the canonical NF-κB activation pathway, nuclear translocation of NF-κB is preceded by phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκBα. In contrast to WT*VMM lipid A, the WT*LB and lpxO*LB lipid As triggered the degradation of IκBα (Fig. 4C). The lipid A from lpxO*VMM induced higher degradation of IκBα than that from WT*VMM (Fig. 4C). LPS also activates the MAPKs p38, JNK, and p44/42 through the phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues (24). Western blot analysis revealed that WT*LB lipid A induced the phosphorylation of the MAPKs (Fig. 4D). WT*VMM lipid A triggered the phosphorylation of only p38 and p44/42, which were less apparent than those triggered by the WT*LB lipid A (Fig. 4D). The reduced activation of these inflammatory signaling cascades by the lipid A containing the in vivo pattern was partially dependent on the presence of the 2-hydroxylated lipid A species because the lpxO*VMM lipid A induced higher phosphorylation of p38 and JNK than WT*VMM lipid A (Fig. 4D). No clear differences were observed on the induction of p44/42 phosphorylation by these two lipid As (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

In vivo lipid A pattern evokes reduced inflammatory responses. (A) TNFα secretion by MH-S macrophages stimulated with different concentrations of lipid A purified from 52145-ΔwcaK2 (WT*), 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxO (lpxO*), and 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxOCom (lpxO*Com) grown in LB (white symbols) or VMM (black symbols). (B) NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation in MH-S macrophages mock treated (CON) or stimulated with lipid As (5 µg/mL) from 52145-ΔwcaK2 grown in LB (WT*LB) and VMM (WT*VMM), 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxO grown in VMM (lpxO*VMM), and LB (lpxO*LB), and the complemented strain, 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxOCom, grown in VMM (lpxO*ComVMM) and LB (lpxO*ComLB). At least 100 cells per sample and experiment were counted to determine the number of positive nuclei. (C) Immunoblot analysis of IκBα and tubulin levels in lysates of MH-S macrophages mock treated (CON) or stimulated for 60 min with lipid As (100 ng/mL) purified from 52145-ΔwcaK2 (WT*), 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxO (lpxO*), and 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxOCom (lpxO*Com) grown in LB or VMM. (D) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated MAPKs p38, JNK, and p44/42, and tubulin levels in lysates of MH-S macrophages mock treated (CON) or stimulated for the indicated times (in minutes) with the indicated lipid As (100 ng/mL). (E) kc and tnfα expressions in whole lungs of noninfected mice (five mice) or after K. pneumoniae infections (five mice per indicated strain and time point). Bars represent mean ± SEM; ns, not significant (one-way ANOVA).

Further highlighting the importance of LpxO-controlled lipid A modification to reduce host inflammatory responses, levels of tnfα mRNA were higher in lungs of mice infected with 52145-ΔlpxO than in those infected with Kp52145 (Fig. 4E). At 24 h postinfection, levels of kc mRNA were significantly different between Kp52145 and 52145-ΔlpxO-infected mice (Fig. 4E). The levels of kc and tnfa mRNAs found in the lungs of Kp52145-infected mice did not change over time [P > 0.05 for comparisons for a given cytokine (one-tailed t test)] (Fig. 4E).

Together, our findings suggest that the in vivo 2-hydroxylated lipid A elicits a limited activation of inflammatory responses both in vitro and in vivo.

Klebsiella in Vivo Lipid A Pattern and Resistance to Antimicrobial Peptides.

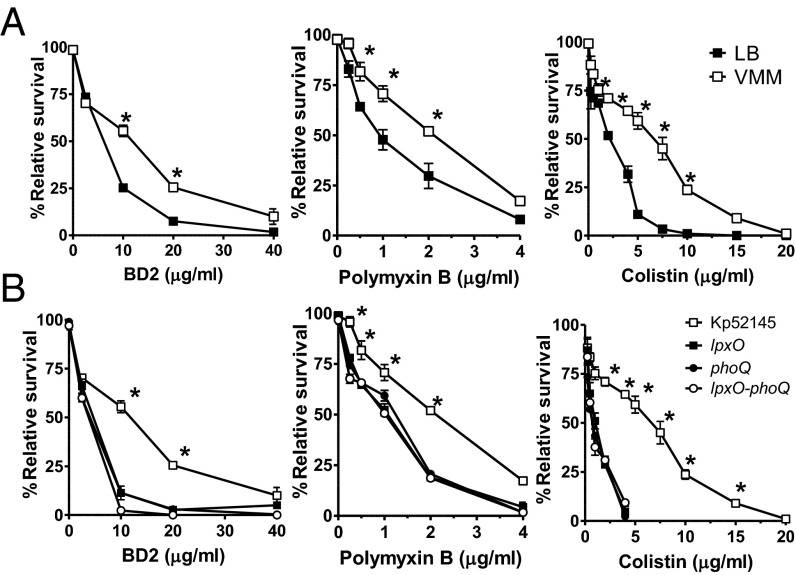

Modifications of the lipid A structure have also been linked to pathogen protection from the onslaught of host antimicrobial peptides (APs) (25). To address whether the lipid A pattern found in vivo promotes K. pneumoniae resistance to APs, bacteria grown in either LB or VMM were compared for resistance to β-defensin 2 (BD2). BD2 is a physiological cationic AP whose levels in the lung increase several fold during pneumonia (26). Indeed, Kp52145 was more resistant to BD2 when grown in VMM than in LB (Fig. 5A). Colistin (polymyxin E) and polymyxin B are two antimicrobials that share the interaction site with the anionic LPS with mammalian APs (25, 27). Resistance to colistin and polymyxin B was also promoted by growing Kp52145 in VMM (Fig. 5A). The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of BD2, colistin, and polymyxin B for Kp52145 were lower when K. pneumoniae was grown in LB (6.1 ± 0.2; 2.0 ± 0.1; and 0.9 ± 0.1, respectively) than when grown in VMM (10.0 ± 1.2; 6.6 ± 0.2; and 2.1 ± 0.2, respectively (P < 0.01 for comparisons for a given peptide; one-tailed t test). LpxO-dependent lipid A modification was responsible for the increased resistance observed in VMM because 52145-ΔlpxO was more susceptible to BD2, polymyxin B, and colistin than Kp52145 (Fig. 5B). The fact that the phoQ and lpxO-phoPQ mutants were as susceptible as the lpxO mutant to the APs tested (Fig. 5B) suggests that Kp52145 may not activate additional PhoPQ-dependent mechanisms of AP resistance when grown in VMM. The IC50 of BD2, colistin, and polymyxin B for the lpxO mutant grown in VMM (4 ± 0.2; 0.5 ± 0.1; and 1.1 ± 0.1, respectively), for the phoQ mutant grown in VMM (3.5 ± 0.4; 0.7 ± 0.4; and 1.6 ± 0.7, respectively), and for the lpxO-phopQ mutant grown in VMM (3.2 ± 0.4; 0.9 ± 0.4; and 1.1 ± 0.7, respectively) were not significantly different (P > 0.05 for comparisons for a given peptide between mutant strains; one-way ANOVA) but all of them were significantly lower than those for Kp52145 grown in VMM (P < 0.05 for comparisons for a given peptide between a mutant strain and the wild type; one-way ANOVA). In contrast, the IC50 of BD2, colistin, and polymyxin B for the lpxO complemented strain grown in VMM (9.5 ± 0.2; 7.5 ± 0.1; and 2.4 ± 0.1, respectively) and for the complemented phoQ mutant grown in VMM (11 ± 3; 5.9 ± 0.4; and 3.6 ± 0.7, respectively) were not significantly different from those for Kp52145 grown in VMM (P > 0.05 for comparisons for a given peptide between complemented strains and the wild type; one-way ANOVA).

Fig. 5.

In vivo lipid A pattern mediates resistance to antimicrobial peptides. (A) Kp52145 grown in LB (black symbols) or in VMM (white symbols) was exposed to different concentrations of BD2, polymyxin B, and colistin. (B) Different strains grown in VMM were exposed to different concentrations of BD2, polymyxin B, and colistin. In A and B graphs, each point represents the mean and SD of six samples from three independently grown batches of bacteria. In A, significant survival differences are shown (*P < 0.05; one-tailed t test) between growth media. In B, significant survival differences are shown (*P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA) between Kp52145 and any of the mutant strains: 52145-ΔphoQGB (phoQ), 52145-ΔlpxO (lpxO), 52145-ΔlpxO-ΔphoQGB (lpxO-phoQ).

Altogether, our findings highlight that the LpxO-mediated lipid A modification plays an important role in K. pneumoniae resistance to APs.

Klebsiella in Vivo Lipid A Pattern and Resistance to Colistin.

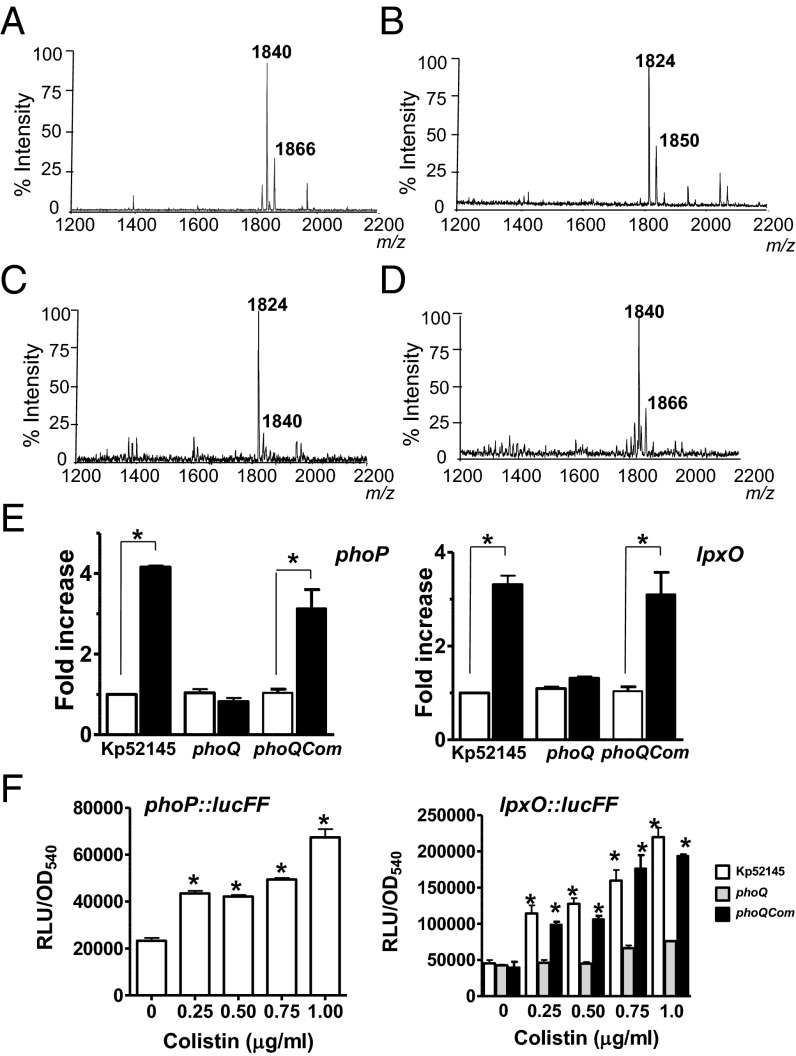

The contribution of the LpxO-dependent lipid A modification to increased colistin resistance led us to analyze whether this occurs in the clinically relevant K. pneumoniae carbapenem–colistin-resistant isolates. Lipid A from these strains was extracted and analyzed to confirm the presence of LpxO-dependent modification in carbapenem–colistin-resistant isolates. Mass spectrometry analysis revealed that lipid A from these isolates contained ions of m/z 1,840 and m/z 1,866 (Fig. 6A). As expected, the lipid A from isogenic lpxO mutants contained ions of m/z 1,824 and m/z 1,850 (a m/z difference of 16; Fig. 6B). In contrast, the lipid A extracted from seven strains that are carbapenem resistant but susceptible to colistin contained ions similar to those found in the lipid A from Kp52145 grown in LB (Fig. 6C). Further supporting the connection between LpxO-dependent lipid A modification and colistin resistance, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to colistin of the colistin-resistant isolates decreased when lpxO was mutated (SI Appendix, Table S3). Complementation of the mutants increased the MIC to colistin (SI Appendix, Table S3).

Fig. 6.

Lipid A of colistin-treated bacteria is identical to lipid A expressed by Klebsiella in the lungs. (A) Negative ion MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry spectra from: (A) a representative clinical isolate (no. 2608) of seven strains resistant to colistin grown in LB; (B) its isogenic lpxO mutant; (C) a representative clinical isolate (no. 2615) of seven strains susceptible to colistin grown in LB; and (D) Kp52145 exposed for 1 h to colistin (1 µg/mL) in LB. (E) The transcription levels of phoP and lpxO in colistin-treated Kp52145, 52145-ΔphoQGB (phoQ), or 52145-ΔphoQGBCom (phoQCom) (black bars) were determined by RT-qPCR and are shown relative to the expression levels in mock-treated bacteria (white bars). Results represent means ± SDs. *P < 0.05 (for the indicated comparison, one-way ANOVA); ns, P > 0.05 for the indicated comparison. (F) Luminescence was determined for bacteria carrying the transcriptional fusions phoP::lucFF or lpxO:lucFF exposed for 1 h to different concentrations of colistin. Results are significantly different (**P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA) from the results for nontreated bacteria. In A–D, results are representative of extractions from five independent experiments.

To explore whether colistin treatment induces the lipid A structure found in vivo, Kp52145 grown in LB was treated with colistin and the lipid A analyzed by mass spectrometry. The lipid A from colistin-treated Kp52145 gave mass peaks at m/z 1,840 and m/z 1,866 (Fig. 6D). RT-qPCR experiments showed that the levels of phoP and lpxO mRNAs were higher in colistin-treated bacteria than in control bacteria (Fig. 6E). PhoPQ governed colistin-triggered up-regulation of phoP and lpxO because colistin-induced changes were not observed in the phoQ mutant background (Fig. 6E). Colistin treatment up-regulated the expression of the phoP::lucFF and lpxO::lucFF transcriptional fusions in the wild-type background (Fig. 6F). In contrast, colistin did not up-regulate the expression of the lpxO::lucFF transcriptional fusion in the phoQ mutant (Fig. 6F). Complementation of the phoQ mutant restored the colistin-triggered up-regulation of phoP and lpxO mRNA levels and the activity the lpxO::lucFF fusion to wild-type levels (Fig. 6 E and F).

Collectively, these results indicate that colistin promotes the lipid A changes found in vivo in a PhoPQ-dependent manner.

Discussion

The lipid A contains a molecular pattern recognized by the innate immune system thereby initiating several host defense responses. Pioneering studies demonstrated that Salmonella remodels its lipid A under changing in vitro conditions (5, 6). The knowledge that these modifcations fortify the outer membrane, mediate resistance to Aps, and evoke limited cytokine responses in vitro (3, 10, 11) led to the assumption that these lipid A structures should be produced in vivo and the loci needed for their biosynthesis should be important virulence factors (3). This rationale has informed studies in other pathogens including Yersinia, Bordetella, Helicobacter, Vibrio, Francisella, and Pseudomonas (3). The panoply of lipid A modifications include the addition of aminoarabinose, phosphoethanolamine, amino acids, palmitate, and the removal of phosphates and fatty acids by the action of specific phosphatases and deacylases, respectively (1–3). The contribution of these lipid A modifications to virulence has been established in very few cases. Thus, a question remained of whether Gram-negative pathogens do remodel their lipid A in vivo. In this work, by combining biochemistry and genetics, we have uncovered for the first time to our knowledge the lipid A expressed by a pathogen, K. pneumoniae, within host tissues. Our findings suggest that these in vivo-induced lipid A changes contribute to K. pneumoniae virulence by counteracting innate immune defenses.

K. pneumoniae expresessed two 2-hydroxylated hexaacyl lipid A species (m/z 1,840 and m/z 1,866) in the lungs of infected mice, and we have shown that LpxO is the enzyme responsible for hydroxylating the C14 on the primary 2′-linked R-3-hydroxymyristoyl group. It is noteworthy that StLpxO, one of the closest homologs to KpLpxO, hydroxylates the C14 3′-linked R-3-hydroxymyristoyl group fatty acid instead of the 2′-linked one (7, 8, and this work) thereby highlighting the need of biochemical analysis to conclusively assign the function of lipid A enzymes. The in vivo lipid A pattern was lost in in vitro minimally passaged bacteria, which emphasizes that the conditions faced by pathogens in vivo cannot be mimicked in conventional growth media such as LB. In this regard, a previous study from our laboratory explored whether APs, taken as a proxy for a likely environmental cue faced by Klebsiella in the lungs, induce lipid A changes contributing to virulence (15). However, the only lipid A species common to those found in vivo is the ion m/z 1,840. Data shown in SI Appendix, Table S1 illustrate the plasticity of Klebsiella lipid A under different growth conditions. Only when Klebsiella was grown in VMM, did the pathogen express the same lipid A pattern found in vivo as characterized by ions m/z 1,840 and m/z 1,866. Interestingly, the in vivo lipid A pattern was not observed in Klebsiella grown in a standard low magnesium medium used to study lipid A changes in other pathogens (5, 6, 28, 29). In any case, it has been reported that Salmonella up-regulates the transcription of lpxO when growing in low magnesium medium (9). By no means do we claim that VMM medium recapitulates the in vivo complex microenvironment of the infected lung. Instead we hypothesize that Klebsiella activates the same regulatory network(s) to remodel its lipid A in the lungs and when growing in VMM. Our data support the idea that the two-component system PhoPQ plays a major role in this process. It is beyond the scope of this work to identify the signal(s) sensed by Klebsiella PhoQ in vivo. Elegant structure–function studies have demonstrated that acidic pH and APs additively activate Salmonella PhoQ (30–32). Both signals are also relevant in the context of Klebsiella pneumonia. Nonetheless, a Salmonella strain carrying a PhoQ mutation rendering the protein unable to be activated by acidic pH is as virulent as the wild type (30). It is then plausible that the stimuli sensed by PhoQ in vivo are APs. However, it is important to remember that sensing may be host-compartment specific. Supporting this notion, in this work we have shown that the in vivo-induced regulatory changes are tissue specific because the Klebsiella lipid A pattern was different in the lungs compared with the spleen. The fact that the lipid A expressed by Klebsiella in the spleen is similar to that expressed by the phoQ mutant in the lungs suggests that PhoPQ-regulated systems are not required for Klebsiella survival in the spleen. A transcriptome analysis of Klebsiella in different tissues is warranted to shed light into tissue-induced Klebsiella adaptations.

Here, we demonstrate that the LpxO-dependent lipid A modification acts as a shield against innate immunity recognition thereby contributing to the panoply of K. pneumoniae systems involved in the attenuation of inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo (33–38). This lipid A modification also helps K. pneumoniae to counteract the bactericidal action of APs, including colistin, which is one of the few remaining therapeutic options available to treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant Klebsiella isolates. The fact that colistin treatment induces the lipid A pattern found in vivo warrants careful consideration on the use of this antibiotic to treat K. pneumoniae infections.

To date, no study has linked LpxO-mediated lipid A modification to AP resistance and therefore it will be interesting to know whether this is also the case for other pathogens containing 2-hydroxyl fatty acids in the lipid A. If this is the case, it is reasonable to anticipate the development of innovative antimicrobial therapeutics based on targeting LpxO. At present we can only speculate on the molecular mechanism underlying LpxO-dependent colistin resistance. The simplest explanation is that the addition of a 2-hydroxyl group in a fatty acid chain stabilizes the outer membrane. It has been argued, on the basis of the structural similarity between lipid A and sphingolipids, that this may increase the H bonding between neighboring LPS molecules, thereby resulting in bilayer stabilization (39). Lipid A modifications are thought to increase the stability of the outer membrane (39). Addition of the positively charged compounds 4-aminoarabinose or phosphoethanolamine would decrease the electrostatic repulsion between the lipid A molecules hence stabilizing the bilayer. Similarly, addition of palmitate would also stabilize the bilayer by increasing the hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions between neighboring LPS molecules. Given indirect support to this notion, the outer membrane of a Salmonella PhoP-constitutive strain is more robust than the outer membrane of a PhoP-defective mutant (10). Future research efforts will be directed to understand LpxO-mediated AP resistance.

This work further highlights the connection between virulence and antimicrobial resistance. We have shown that LpxO-dependent lipid A modification is not only important for Klebsiella survival in the lung but also mediates resistance to the clinically relevant AP colistin. The connection between virulence and antibiotic resistance has been particularly studied in the case of Pseudomonas (40, 41). A number of bacterial regulatory genes have been identified to influence both virulence and antibiotic resistance including PhoPQ (40, 41). In Klebsiella, the global regulator RamA has been recently shown to regulate not only antimicrobial resistance systems but also virulence factors including genes associated with LPS biosynthesis (42). It is then tempting to speculate that part of the success of the virulent multidrug-resistant Klebsiella clones spreading worldwide (43) may be associated with changes of their lipid A pattern to evade immune surveillance compared with other less virulent Klebsiella clones. Studies are on-going to corroborate this hypothesis.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement.

Mice were treated in accordance with the Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (Directive 2010/63/EU) and in agreement with the Bioethical Committee of the University of the Balearic Islands. This study was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the University of the Balearic Islands with authorization no. 1748.

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions.

K. pneumoniae 52145 is a clinical isolate (serotype O1:K2) belonging to the CC65K2 virulent clonal group (44, 45). The mutants 52145-ΔwcaK2, 52145-ΔphoQGB, 52145-ΔpmrAB, and 52145-ΔrcsB have been described previously (15, 46). Seven clinical isolates that were carbapenem resistant but colistin susceptible, and seven isolates that were both carbapenem resistant and colistin resistant were provided by Mehmet Doymaz (Pathology/Laboratories, Saint Vincent Medical Center, NY). Bacteria were grown in LB medium at 37 °C. When appropriate, antibiotics were added to the growth medium at the following concentrations: rifampicin (Rif) 25 µg/mL, ampicillin (Amp), 100 µg/mL for K. pneumoniae and 50 µg/mL for E. coli, kanamycin (Km) 100 µg/mL, tetracycline (Tet) 12.5 µg/mL, and chloramphenicol (Cm) 25 µg/mL. VMM medium contains 11.3 g/L M9 minimal salts (Sigma), 0.1% Ez Mix (w/v, Sigma), 0.4% glucose (w/v, Sigma), and 8 μM MgSO4, buffered in 100 mM Mes (Sigma) pH 4.5.

K. pneumoniae Mutant Construction.

Primers for mutant construction were designed based on the genome sequence of K. pneumoniae 52145 (accession no. FO834904). To obtain an lpxO mutant, two sets of primers were used to amplify two different lpxO fragments, LpxOUP (LpxOUPF 5′-CCCAGGCGCAGATTGCCCAG-3′ and LpxOUPR 5′-CGGATCCGGACTCACTATAGGGGCGATATTGAACGGCCGATG-3′; 748 bp), and LpxODown (LpxODOWNF 5′-CGGATCCGGACTCACTATAGGGGCGGTAAATGTGGAATGGTCG-3′ and LpxODOWNR 5′-TCCGTTCACTGCGTGCCCTG-3′; 952 bp) by PCR. These fragments were annealed at their overlapping region and amplified as a single fragment, which was cloned into pGEM-T Easy to obtain pGEMT∆lpxO. A kanamycin cassette was obtained as a BamHI fragment from pGEMTFRTKM (15) and was cloned into BamHI-digested pGEMT∆lpxO to generate pGEMTΔlpxOKm. The ΔlpxO::Km allele was PCR amplified using primers LpxOUPF and LpxODOWNR and 1 µg of PCR product was electroporated into either Kp51245 or 52145-ΔwcaK2 harboring the lambda-red protein-encoding plasmid pKOBEG-sacB (47). Mutants were selected onto LB agar containing kanamycin and a recombinant in which the wild-type allele was replaced by the mutant one and was selected and named 52145-∆lpxOKm and 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxOKm. The appropriate replacement of the wild-type allele by the mutant one was confirmed by PCR. pKOBEG-sacB was cured by growing the strain in LB plates without NaCl containing 10% sucrose at 30 °C. The loss of the plasmid was then checked on LB agar containing Cm. The kanamycin cassette was excised by Flp-mediated recombination using plasmid pFLP2 (48) and the generated mutants were named 52145-∆lpxO and 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxO. The 52145-∆lpxO-phoQGB double mutant was obtained by mobilizing pMAKSACΔphoPQGB (15) into 52145-∆lpxO. The replacement of the wild-type allele by the mutant one was done as previously described (15) and confirmed by PCR.

lpxO mutants in the clinical isolates were constructed by insertion-duplication. Using genomic DNA from each strain as template, an internal fragment of the lpxO gene was PCR amplified using primers KpnIntlpxOF (5′-CCGACCATTCCACATTTACC-3′) and KpnIntlpxOR (5′-TGGGCATCCTCATACCATTT-3′) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy. The fragments were obtained by EcoRI digestion and cloned into EcoRI-digested pKNOCK-Km suicide vector (49) to obtain pKNOCK-KmintlpxO. pKNOCK-KmintlpxO plasmids were mobilized into K. pneumoniae colistin resistant isolates and transconjugates were selected after growth on LB agar supplemented with Km. Integration of the suicide vector into lpxO locus by homologous recombination was confirmed by PCR.

To construct a pagP mutant, a kanamycin casette flanked by FRT sites was PCR amplified using as template plasmid pKD4 (50) and primers KpnpagPF (5′-TGTCCGGAAACGCCAGCGCGTCGTTTTCATCGACCCTTAGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′) and KpnPagPR (5′-AAGTAAACTTACCGTTATTGTAGGTGCCGGGAATATAGGTCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG-3′). Primers incorporate 50 nucleotide homologous extensions to pagP. PCR product was purified, treated with DpnI, and 1 µg of PCR product was electroporated into Kp51245 harboring pKOBEG-sacB. Mutants were selected on LB agar containing kanamycin and a recombinant in which the wild-type allele was replaced by the mutant one and was selected and named 52145-∆pagPKm. The appropriate replacement of the wild-type allele by the mutant one was confirmed by PCR. pKOBEG-sacB was cured as previously described and the kanamycin casette was excised by Flp-mediated recombination. The generated mutant was named 52145-∆pagP. To confirm that pagP mutation has no polar effects, the expression of the downstream gene, cpsE, was analyzed by RT-qPCR as previously described (15).The expression of cpsE by 52145-∆pagP was similar to that by the wild-type strain.

To construct an lpxM mutant, a 2.6-kb DNA fragment encompassing lpxM was PCR amplified using primers KpnMsbBF (5′-GGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCTC-3′) and KpnMsbBR (5′-CTGTCTGCCGAAGCGCTGAC-3′), gel purified, and cloned into pGEM-T Easy to obtain pGEMTKpnmsbB. An EcoRI fragment was subcloned into EcoRI-digested pUC18 to give pUCKpnmsbB. A kanamycin resistance cassette, obtained as a 1.4-kb PstI fragment from pUC-4K (Pharmacia), was cloned into NsiI-digested pUCKpnmsbB to obtain pUCKpnmsbBGB. lpxM::GB allele was obtained by PvuII digestion and cloned into SmaI-digested pMAKSACB (51) to give pMAKSACKpnmsbBGB. This plasmid was electroporated into E. coli S17-1λpir, from which the plasmids were mobilized into K. pneumoniae 52145. Transconjugates were selected after growth on LB plates supplemented with Cm at 30 °C. The replacement of the wild-type allele by the mutant one was done as previously described (15) and confirmed by PCR. The mutant selected was named 52145-lpxMGB.

The pagP-lpxM double mutant, strain 52145-∆pagP-lpxMGB, was obtained by mobilizing pMAKSACKpnmsbBGB into 52145-∆apgP. The replacement of the wild-type allele by the mutant one was done as previously described (15) and confirmed by PCR.

Complementation of the phoQ Mutant.

To complement the phoQ mutant, a DNA fragment of 3.1 kb containing the putative promoter region and coding region of phoPQ was PCR amplified using Pfu polymerase and phosphorylated primer pair Kp52_PhoPQ_compF1 (5′-ATCCTGATGGCTGACAAGGC-3′) and Kp52_PhoPQ_compR1 (5′-TCGGGGATAAACGGTAGTGG-3′). The fragment was gel purified and cloned into SmaI-digested pGP-Tn7-Cm (52) to obtain pGP-Tn7-Cm_KpnPhoPQCom. The pTSNSK-Tp plasmid, which contains the transposase tnsABCD necessary for Tn7 transposon mobilization (52), was electroporated into the phoQ mutant. pGP-Tn7-Cm_KpnPhoPQCom plasmid was then mobilized into this strain by conjugation. Colonies were screened for resistance to Cm and sensitivity to Ap. Because the Ap cassette is located outside of the Tn7 region on the vector, sensitivity to Ap denotes the integration of the Tn7 derivative at the attTn7 site instead of incorporation of the vector into the chromosome. Confirmation of integration of the Tn7 transposon at the established attTn7 site located downstream of the glmS gene was verified by PCR as we have previously described (34). pTSNSK-Tp from the recipient strain was cured by growing bacteria at 37 °C due to the plasmid thermosensitive origin of replication pSC101. Plasmid removal was confirmed by susceptibility to Tp and the strain was named 52145-ΔphoQGBCom.

Complementation of lpxO Mutants.

To complement the lpxO mutant, a DNA fragment of 1.5 kb was PCR amplified using Pfu polymerase and phosphorylated primers LpxOUPF and LpxoDOWNR, gel purified, and cloned into the SmaI site of pGP-Tn7-Cm (52) to obtain pGP-Tn7-Cm_KpnLpxOCom. This plasmid was mobilized by conjugation into lpxO mutants, strains 52145-∆lpxO and 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxO, containing plasmid pTSNSK-Tp to obtain 52145-∆lpxOCom and 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxOCom, respectively. Integration of the Tn7 was confirmed as previously described. pGP-Tn7-Cm_KpnLpxOCom was also mobilized into the clinical isolates lpxO mutants. pTSNSK-Tp from the recipient strains was cured by growing bacteria at 37 °C.

Klebsiella lpxO was also PCR amplified using TaKaRa polymerase and primers LpxOUPF and LpxoDOWNR, gel purified, and cloned into pGEMT-Easy to obtain pGEMTKplpxOCom. A fragment, containing the putative promoter and coding region of the hydroxylase, was obtained by PvuII digestion of pGEMTKplpxOCom, gel purified, and cloned into the ScaI site of the medium copy plasmid pTM100 (53) to obtain pTMKpLpxO. Salmonella lpxO was PCR amplified using TaKaRa and primers Salm_LpxO_compF1 (5′-AGCCGTAGTAGCCCTTCAGA-3′) and Salm_LpxO_compR1 (5′-TTTCAGGGATGGATTCGCCG-3′) and cloned into pGEMT-Easy to obtain pGEMTSalLpxOCom. Subsequently a PvuII fragment was cloned into ScaI-digested pTM100 to obtain pTMSalLpxO.

For the construction of plasmid pTMLpxOFLAG, the lpxO coding region with its own promoter and a FLAG epitope sequence right before the stop codon was PCR amplified using Vent DNA polymerase and primers LpxOUPF and KpnlpxocomplFLAGR1 (5′-TTACTTGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTAAACGCGCTCCAGAT-3′). The fragment was phosphorylated, gel purified, and cloned into ScaI-digested pTM100.

pTM100 derivatives were introduced into E. coli DH5α-λpir and then mobilized into K. pneumoniae strains by triparental conjugation using the helper strain E. coli HB101/pRK2013.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

pTMLpxOFLAG was used as template and the desired mutations were introduced by inverse PCR using Vent polymerase and the following primer pairs: KpnlpxOH155F (5′-GCTCGTGCCCCCTACGCCGG-3′) and KpnlpxOH155R (5′-GCGCGGCAGACGGCTACCGT-3′); KpnlpxOD157F (5′-GCCCCCTACGCCGGCTCGCT-3′) and KpnlpxOD157R (5′-ACGAGCGCGCGGCAGACGGC-3′); KpnlpxOR164F (5′-GCCTTTGCTCTGGGCCTGGC-3′) and KpnlpxOR164R (5′-TAGCGAGCCGGCGTAGGGGG-3′); KpnlpxOH166F (5′-GCTCTGGGCCTGGCAACGCC-3′) and KpnlpxOH166R (5′-AAAGGCTAGCGAGCCGGCGT-3′); KpnlpxOW188F (5′-GCGCGCGATGGAGAAGGCGT-3′) and KpnlpxOW188R (5′-ACTGTCACGCTGGCCATCCA-3′); KpnlpxOE198F (5′-GCGACCTATATCGCCTATGC-3′) and KpnlpxOE198R (5′-GTCAAACAGCACGCCTTCTC-3′); KpnlpxOH202F (5′-GCCTATGCGGAAAATACCAG-3′) and KpnlpxOH202R (5′-GATATAGGTCGCGTCAAACA-3′); KpnlpxOR212F (5′-GCCCTGATTCTGTTCTGCGC-3′) and KpnlpxOR212R (5′-ATTCTCACCACTGGTATTTT-3′); and KpnlpxOD218F (5′-GCTATTGAACGGCCGATGCG-3′) and KpnlpxOD218R (5′-GCAGAACAGAATCAGGGCAT-3′). The name of each mutant construct includes the wild-type residue (single-letter amino acid designation) followed by the codon number and mutant residue (typically alanine). Amplifications were carried out using Vent DNA polymerase exactly as previously described (54). The lpxO gene was sequenced to confirm the generated mutations.

Isolation and Analysis of Lipid A.

Lipid As were extracted using an ammonium hydroxide/isobutyric acid method (13) or the TRI Reagent method (14) and subjected to negative ion MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis. To extract lipid A from bacteria, they were grown in 10 mL of medium until the exponential phase. Bacteria were washed once with PBS and the lipid A was extracted from the pellet using one of the mentioned protocols. To extract lipid A from organs, they were homogenized in 1 mL PBS, an aliquot was used for bacterial load determination, and the rest of the homogenate was lyophilized. BALF, obtained as previously described (55), was also lyophilized. Dry material was then used for the lipid A extraction using the aforementioned protocols. To analyze the samples, a few microliters of lipid A suspension (1 mg/mL) were desalted with a few grains of ion-exchange resin (Dowex 50W-X8; H+) in a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube. A 1-µL aliquot of the suspension (50–100 µL) was deposited on the target and covered with the same amount of dihydroxybenzoic acid matrix (Sigma Chemical) dissolved in 0.1 M citric acid. Different ratios between the samples and dihydroxybenzoic acid were used when necessary. Alternatively, lipid A was mixed with 5-chloro-2-mercapto-benzothiazole (Sigma Chemical) [20 mg/mL in chloroform/methanol (1:1, vol/vol)] at a ratio of 1:5. Each spectrum was an average of 300 shots. A peptide calibration standard (Bruker Daltonics) was used to calibrate the MALDI-TOF. Further calibration for lipid A analysis was performed externally using lipid A extracted from E. coli strain MG1655 grown in LB at 37 °C. Interpretation of the negative-ion spectra is based on earlier work showing that ions with masses higher than 1,000 gave signals proportional to the corresponding lipid A species present in the preparation (56). Important theoretical masses for the interpretation of peaks found in this study are: C14:OH, 226; C12, 182; C14, 210; and C16, 239.

LPS Purification.

LPS was purified from bacteria, 52145-ΔwcaK2, 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxO, and 52145-ΔwcaK2-∆lpxOCom grown in 2 l of LB or VMM using the water-phenol method. LPS was further purified by DNase, Rnase, and proteinase K treatments before ethanol precipitation (57). LPS was recovered by ultracentrifugation and the pellet was resuspended in water and lyophilized. LPS was repurified using phenol reextraction in the presence of deoxycholate to eliminate lipoprotein contaminants (58). This LPS did not activate the NF-κB–dependent luciferase reported gene in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with human TLR2 (59). Lipid A was obtained by acid hydrolysis (60).

Construction of Reporter Fusions.

A DNA fragment containing the promoter regions of the lpxO gene was amplified using primers ProLpxOF (5′-TGAAGGTGGAGACCTTCGTCG-3′), ProLpxOR (5′-GGAATTCCGGACAGGGAAGAATGCCGAAG-3′), and Vent polymerase, EcoRI digested, gel purified, and cloned into EcoRI–SmaI-digested pGPL01 (61). This vector contains a promoterless firefly luciferase gene (lucFF) and a R6K origin of replication. A plasmid in which lucFF was under the control of the lpxO promoter was identified by restriction digestion analysis and named pGPLKpnLpxO. The plasmid was introduced into the different Klebsiella strains used in this study by conjugation. Strains in which the suicide vector was integrated into the genome by homologous recombination were selected. This was confirmed by PCR. The phoP::lucFF transcriptional fusion has been described previously (15).

Luciferase Activity.

The reporter strains were grown on an orbital incubator shaker (180 rpm) until late log phase and, when indicated, colistin was added and the culture incubated for 1 h more. At the end of the incubation the OD at 540 nm was recorded. A 100-µL aliquot of the bacterial suspension was mixed with 100 µL of luciferase assay reagent [1 mM d-luciferin (Synchem) in 100 mM citrate buffer pH 5]. Luminescence was immediately measured with a LB9507 Luminometer (Berthold) or a Glomax 20/20 Luminometer (Promega) and expressed as relative light units (RLU)/OD540. All measurements were carried out in quintuplicate on at least three separate occasions.

For in vivo determination of luciferase activity, groups of five mice were infected with ∼1 × 106 cfu of each reporter strain. After 24 h, mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and lungs were rapidly homogenized in 500 μL PBS using an Ultra-Turrax TIO basic disperser (IKA). Serial dilutions were plated on LB-agar with rifampin to determine the number of colony-forming units. In parallel, 100 μL of the organ homogenate was mixed with 100 μL of luciferase assay reagent [1 mM d-luciferin (Synchem) in 100 mM citrate buffer, pH 5], and luminescence was immediately measured and expressed as RLU per cfu. Control experiments showed that homogenized lungs did not quench luminescence.

Structural Modeling of KpLpxO.

To search for related sequences and a crystal structure that could be used as a template for modeling, the KpLpxO sequence was used as bait to search UniProtKB and Protein Data Bank with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) at NCBI (blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). KpLpxO was also subjected to the transmembrane helix prediction server TMHMM (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/), and a homology model of the nontransmembrane part was constructed based on the crystal structure of human Asp/Asn β-hydroxylase isoform A (residues 562–758, PDB code 3RCQ). MALIGN (62) in the BODIL modeling environment (63) was used to align KpLpxO with similar sequences (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Human Asp/Asn β-hydroxylase sequence was then added to the alignment, using prealigned sequences. For modeling, all sequences, except KpLpxO and human Asp/Asn β-hydroxylase, were deleted from the alignment (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). A set of 10 models was created with MODELER (64), and the model with the lowest value of the MODELER objective function was analyzed and compared with the crystal structure of human Asp/Asn β-hydroxylase. The quality of the final model was assessed with various servers, such as QMEAN (65), ProSA-web (66), and ModFOLD (67). The active site cavity, and lining amino acids, was detected with SURFNET (68). The calculations were performed with a gap sphere with a minimum radius of 1.5 Å and maximum radius of 4.0 Å. PyMOL (version 1.4, Schrödinger) was used to prepare pictures of the 3D model.

Murine Infection Model.

Five-to-seven-week-old female CD-1 mice (Harlan) were anesthetized by i.p. injection with a mixture containing ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). Bacteria inoculi were prepared as previously described (35). Mice were inoculated intranasally with 20 μL of bacterial suspension adjusted to 107 cfu/mL. Noninfected mice were inoculated with 20 μL of PBS. At 24 h postinfection mice were killed by cervical dislocation. Tissues were rapidly dissected for bacterial load determination and half of the lungs were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until purification of RNA was carried out.

RT-qPCR.

RNA from lungs was purified exactly as previously described (35). cDNA was obtained by retrotranscription of 1 μg of total RNA using the M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Sigma). The reaction included one step to eliminate traces of genomic DNA. A total of 50 ng of cDNA was used as a template in a 25-µL reaction. RT-PCR analyses were performed with a Smart Cycler real-time PCR instrument (Cepheid) and using a KapaSYBR Fast qPCR kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Cultek). Sequences of primers used for RT-qPCR are mKC.F (5′-GACAGACTGCTCTGATGGCA-3′) and mKC.R (5′-TGCACTTCTTTTCGCACAAC-3′); and mTNFa.F (5′-CCACATCTCCCTCCAGAAAA-3′) and mTNFa.R (5′-AGGGTCTGGGCCATAGAACT-3′). The thermocycling protocol was as follows: an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 3 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C/20 s, and 60 °C/30 s. RT-qPCR analyses were performed using an iCycler real-time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad). Relative quantities of mRNAs were obtained using the comparative threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method by normalizing to hprt1 amplified using primers mHPRT1.F (5′-AAGCTTGCTGGTGAAAAGGA-3′) and mHPRT1.R (5′-TTGCGCTCATCTTAGGCTTT-3′).

Bacterial RNA was obtained as previously described (15). cDNA was obtained by retrotranscription of 2 µg of total RNA using a commercial M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Sigma), and random primers mixture (Quiagen). A total of 50 ng of cDNA was used as a template in a 25-µL reaction using a KapaSYBR Fast qPCR kit (Cultek). The thermocycling protocol was as follows; 95 °C for 3 min for hot-start polymerase activation, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 30 s. SYBR green dye fluorescence was measured at 521 nm. cDNAs were obtained from three independent extractions of mRNA and each one was amplified by RT-qPCR on two independent occasions using primer pairs Kp52_PhoP_qPCR_F1 (5′-GCGGTTACG GATCAGGGTTT-3′) and Kp52_PhoP_qPCR_R1 (5′-TACGTCACCAAGCCTTTCCA-3′) to analyze phoP expression or Kp52_LpxO_F1 qPCR (5′-GACCGCTGCTTTATC GAGGT-3′) and Kp52_LpxO_R1 qPCR (5′-CTCATCAGATGGCGTCCCAG-3′) to study lpxO expression. Relative quantities of mRNAs were obtained using the comparative threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method by normalizing to rpoB and tonB genes (15).

TNFα Stimulation Assay.

Murine alveolar macrophages MH-S (ATCC CRL-2019) were cultured as previously described (69). MH-S were seeded to 80% confluence (1 × 105 cells per well) in 96-well tissue-culture plates and stimulated with different concentrations of lipid A for 16 h. Supernatants were recovered, cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and samples were frozen at −80 °C. TNFα levels in the supernatants were determined using a commercial ELISA (eBioscience) with a sensitivity of <2 pg/mL. Experiments were run in triplicate and repeated at least three independent times.

NF-κB p65 Staining.

MH-S macrophages were seeded to 90% confluence in 24-well tissue culture plates containing a 13-mm diameter borosilicate coverslip. Cells were stimulated with lipid A (5 μg/mL) diluted in complete RPMI for 45 min. After stimulation, coverslips were washed twice with PBS, fixed for 15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, and kept at 4 °C in 14 mM NH4HCl diluted in PBS. p65 staining was carried out exactly as previously described (33). Samples were analyzed using a fluorescence microscope Leica DM6000 and images were taken with a Leica DFC350FX camera. Experiments were run in triplicate and repeated at least three independent times.

Immunoblotting.

MH-S cell extracts were obtained as previously described (69). Proteins were resolved by standard 10% SDS/PAGE and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 4% (wt/vol) skim milk in TBST and protein bands were detected with specific antibodies using chemiluminescence reagents and a GeneGnome chemiluminescence imager (Syngene). Immunostainings for IκBα and to assess phosphorylation of p38, p44/42, and JNK MAPKs were performed using polyclonal rabbit, anti- IκBα, anti-phospho-p38 antibody, anti-phospho-p44/42, and anti-phospho-JNK antibodies, respectively (all used at 1:1,000; Cell Signaling). Blots were reprobed with polyclonal antibody anti-human tubulin (1:3,000; Sigma) to control that equal amounts of proteins were loaded in each lane. Experiments were repeated three independent times.

To detect the levels of LpxO FLAG-tagged proteins, bacterial cell extracts were preparared in SDS sample buffer. The protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). A total of 80 µg of proteins was separated on 4–12% SDS/PAGE and semidry electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Membrane was blocked with 4% skim milk in PBS and stained using anti-Flag antibody (1:2,000; Sigma) following the instructions of the supplier.

Antimicrobial Peptide Susceptibility Assay.

Antimicrobial peptide susceptibility was determined exactly as previously described (15). All experiments were done with duplicate samples on at least four independent occasions. The 50% inhibitory concentration of AP (IC50) was defined as the concentration producing a 50% reduction in the colony counts compared with bacteria not exposed to the antibacterial agent. Following guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Chemical Genomics Center (www.ncats.nih.gov/ncgc), IC50 of a given AP was determined from dose–response curve data fit using a standard four-parameter logistic nonlinear regression analysis. Dose–response experiments were done on four independent occasions. Results are reported as mean ± SEM.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni contrasts or the one-tailed t test or, when the requirements were not met, by the Mann–Whitney u test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were performed using Prism4 for PC (GraphPad Software).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mehmet Doymaz for sending us the K. pneumoniae clinical isolates, members of the J.A.B. laboratory for helpful discussions and support to submit the final version of this paper, and Mark Johnson for the excellent computing facilities at the Åbo Akademi University. Use of Biocenter Finland infrastructure at Åbo Akademi (bioinformatics, structural biology, and translational activities) is acknowledged. This work was funded by Sigrid Juselius Foundation (T.A.S.); the Tor, Joe, and Pentti Borg’s Foundation (T.A.S.); and Medicinska Understödsföreningen Liv och Hälsa (T.A.S. and K.M.D.). This work was also supported by a Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness Grant (Biomedicine Programme, SAF2012-39841), Marie Curie Career Integration Grant U-KARE (PCIG13-GA-2013-618162), and Queen’s University Belfast start-up funds (to J.A.B.). Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Respiratorias is an initiative from Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1508820112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Raetz CR, Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raetz CR, Reynolds CM, Trent MS, Bishop RE. Lipid A modification systems in gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:295–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Needham BD, Trent MS. Fortifying the barrier: The impact of lipid A remodelling on bacterial pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11(7):467–481. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee H, Hsu FF, Turk J, Groisman EA. The PmrA-regulated pmrC gene mediates phosphoethanolamine modification of lipid A and polymyxin resistance in Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(13):4124–4133. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4124-4133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo L, et al. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science. 1997;276(5310):250–253. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo L, et al. Lipid A acylation and bacterial resistance against vertebrate antimicrobial peptides. Cell. 1998;95(2):189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbons HS, Reynolds CM, Guan Z, Raetz CR. An inner membrane dioxygenase that generates the 2-hydroxymyristate moiety of Salmonella lipid A. Biochemistry. 2008;47(9):2814–2825. doi: 10.1021/bi702457c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibbons HS, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CR. Oxygen requirement for the biosynthesis of the S-2-hydroxymyristate moiety in Salmonella typhimurium lipid A. Function of LpxO, A new Fe2+/alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase homologue. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(42):32940–32949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbons HS, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Raetz CR. Role of Mg2+ and pH in the modification of Salmonella lipid A after endocytosis by macrophage tumour cells. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55(2):425–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murata T, Tseng W, Guina T, Miller SI, Nikaido H. PhoPQ-mediated regulation produces a more robust permeability barrier in the outer membrane of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(20):7213–7222. doi: 10.1128/JB.00973-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maeshima N, Fernandez RC. Recognition of lipid A variants by the TLR4-MD-2 receptor complex. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:3. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tzouvelekis LS, Markogiannakis A, Piperaki E, Souli M, Daikos GL. Treating infections caused by carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(9):862–872. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Hamidi A, Tirsoaga A, Novikov A, Hussein A, Caroff M. Microextraction of bacterial lipid A: Easy and rapid method for mass spectrometric characterization. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(8):1773–1778. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D500014-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi EC, Hackett M. Rapid isolation method for lipopolysaccharide and lipid A from gram-negative bacteria. Analyst (Lond) 2000;125(4):651–656. doi: 10.1039/b000368i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llobet E, Campos MA, Giménez P, Moranta D, Bengoechea JA. Analysis of the networks controlling the antimicrobial-peptide-dependent induction of Klebsiella pneumoniae virulence factors. Infect Immun. 2011;79(9):3718–3732. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05226-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clements A, et al. Secondary acylation of Klebsiella pneumoniae lipopolysaccharide contributes to sensitivity to antibacterial peptides. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(21):15569–15577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701454200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moskowitz SM, Ernst RK. The role of Pseudomonas lipopolysaccharide in cystic fibrosis airway infection. Subcell Biochem. 2010;53:241–253. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9078-2_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geurtsen J, et al. A novel secondary acyl chain in the lipopolysaccharide of Bordetella pertussis required for efficient infection of human macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(52):37875–37884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacArthur I, Jones JW, Goodlett DR, Ernst RK, Preston A. Role of pagL and lpxO in Bordetella bronchiseptica lipid A biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(18):4726–4735. doi: 10.1128/JB.01502-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helander IM, et al. Characterization of lipopolysaccharides of polymyxin-resistant and polymyxin-sensitive Klebsiella pneumoniae O3. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237(1):272–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0272n.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sforza S, et al. Determination of fatty acid positions in native lipid A by positive and negative electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2004;39(4):378–383. doi: 10.1002/jms.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGinnis K, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis of residues in a conserved region of bovine aspartyl (asparaginyl) beta-hydroxylase: Evidence that histidine 675 has a role in binding Fe2+ Biochemistry. 1996;35(13):3957–3962. doi: 10.1021/bi951520n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fresno S, et al. The ionic interaction of Klebsiella pneumoniae K2 capsule and core lipopolysaccharide. Microbiology. 2006;152(Pt 6):1807–1818. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong C, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. MAP kinases in the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:55–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091301.131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nizet V. Antimicrobial peptide resistance mechanisms of human bacterial pathogens. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2006;8(1):11–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiratsuka T, et al. Identification of human beta-defensin-2 in respiratory tract and plasma and its increase in bacterial pneumonia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249(3):943–947. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, et al. Colistin: The re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(9):589–601. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato A, Latifi T, Groisman EA. Closing the loop: The PmrA/PmrB two-component system negatively controls expression of its posttranscriptional activator PmrD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(8):4706–4711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0836837100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.García Véscovi E, Soncini FC, Groisman EA. Mg2+ as an extracellular signal: Environmental regulation of Salmonella virulence. Cell. 1996;84(1):165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hicks KG, et al. Acidic pH and divalent cation sensing by PhoQ are dispensable for systemic salmonellae virulence. eLife. 2015;4:e06792. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prost LR, Daley ME, Bader MW, Klevit RE, Miller SI. The PhoQ histidine kinases of Salmonella and Pseudomonas spp. are structurally and functionally different: Evidence that pH and antimicrobial peptide sensing contribute to mammalian pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69(2):503–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06303.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prost LR, et al. Activation of the bacterial sensor kinase PhoQ by acidic pH. Mol Cell. 2007;26(2):165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank CG, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae targets an EGF receptor-dependent pathway to subvert inflammation. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15(7):1212–1233. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomás A, et al. Functional genomic screen identifies klebsiella pneumoniae factors implicated in blocking nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) signaling. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(27):16678–16697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.621292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.March C, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae outer membrane protein A is required to prevent the activation of airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(12):9956–9967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.181008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moranta D, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae capsule polysaccharide impedes the expression of beta-defensins by airway epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2010;78(3):1135–1146. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00940-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Regueiro V, Campos MA, Pons J, Albertí S, Bengoechea JA. The uptake of a Klebsiella pneumoniae capsule polysaccharide mutant triggers an inflammatory response by human airway epithelial cells. Microbiology. 2006;152(Pt 2):555–566. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Regueiro V, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae subverts the activation of inflammatory responses in a NOD1-dependent manner. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13(1):135–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67(4):593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breidenstein EB, de la Fuente-Núñez C, Hancock RE. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: All roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19(8):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gooderham WJ, Hancock RE. Regulation of virulence and antibiotic resistance by two-component regulatory systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33(2):279–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Majumdar S, et al. Elucidation of the RamA regulon in Klebsiella pneumoniae reveals a role in LPS regulation. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(1):e1004627. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holt KE, et al. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(27):E3574–E3581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501049112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lery LM, et al. Comparative analysis of klebsiella pneumoniae genomes identifies a phospholipase D family protein as a novel virulence factor. BMC Biol. 2014;12:41–56. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brisse S, et al. Virulent clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae: Identification and evolutionary scenario based on genomic and phenotypic characterization. PLoS One. 2009;4(3):e4982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Llobet E, Tomás JM, Bengoechea JA. Capsule polysaccharide is a bacterial decoy for antimicrobial peptides. Microbiology. 2008;154(Pt 12):3877–3886. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Derbise A, Lesic B, Dacheux D, Ghigo JM, Carniel E. A rapid and simple method for inactivating chromosomal genes in Yersinia. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;38(2):113–116. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoang TT, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: Application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene. 1998;212(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alexeyev MF. The pKNOCK series of broad-host-range mobilizable suicide vectors for gene knockout and targeted DNA insertion into the chromosome of gram-negative bacteria. Biotechniques. 1999;26(5):824–826, 828. doi: 10.2144/99265bm05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(12):6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Favre D, Viret JF. Gene replacement in gram-negative bacteria: The pMAKSAC vectors. Biotechniques. 2000;28(2):198–200, 202, 204. doi: 10.2144/00282bm02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crépin S, Harel J, Dozois CM. Chromosomal complementation using Tn7 transposon vectors in Enterobacteriaceae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(17):6001–6008. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00986-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Michiels T, Wattiau P, Brasseur R, Ruysschaert JM, Cornelis G. Secretion of yop proteins by yersiniae. Infect Immun. 1990;58(9):2840–2849. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.2840-2849.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Byrappa S, Gavin DK, Gupta KC. A highly efficient procedure for site-specific mutagenesis of full-length plasmids using Vent DNA polymerase. Genome Res. 1995;5(4):404–407. doi: 10.1101/gr.5.4.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cai S, Batra S, Wakamatsu N, Pacher P, Jeyaseelan S. NLRC4 inflammasome-mediated production of IL-1β modulates mucosal immunity in the lung against gram-negative bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2012;188(11):5623–5635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindner B. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry of lipopolysaccharides. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;145:311–325. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-052-7:311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bengoechea JA, Díaz R, Moriyón I. Outer membrane differences between pathogenic and environmental Yersinia enterocolitica biogroups probed with hydrophobic permeants and polycationic peptides. Infect Immun. 1996;64(12):4891–4899. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4891-4899.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hirschfeld M, Ma Y, Weis JH, Vogel SN, Weis JJ. Cutting edge: Repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 2000;165(2):618–622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tirsoaga A, et al. Simple method for repurification of endotoxins for biological use. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(6):1803–1808. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02452-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caroff M, Tacken A, Szabó L. Detergent-accelerated hydrolysis of bacterial endotoxins and determination of the anomeric configuration of the glycosyl phosphate present in the “isolated lipid A” fragment of the Bordetella pertussis endotoxin. Carbohydr Res. 1988;175(2):273–282. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(88)84149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gunn JS, Miller SI. PhoP-PhoQ activates transcription of pmrAB, encoding a two-component regulatory system involved in Salmonella typhimurium antimicrobial peptide resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178(23):6857–6864. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6857-6864.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnson MS, May AC, Rodionov MA, Overington JP. Discrimination of common protein folds: Application of protein structure to sequence/structure comparisons. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:575–598. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lehtonen JV, et al. BODIL: A molecular modeling environment for structure-function analysis and drug design. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2004;18(6):401–419. doi: 10.1007/s10822-004-3752-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]