Abstract

During the Age of Mass Migration (1850–1913), the United States maintained an open border, absorbing 30 million European immigrants. Prior cross-sectional work finds that immigrants initially held lower-paid occupations than natives but converged over time. In newly assembled panel data, we show that, in fact, the average immigrant did not face a substantial occupation-based earnings penalty upon first arrival and experienced occupational advancement at the same rate as natives. Cross-sectional patterns are driven by biases from declining arrival cohort skill level and departures of negatively selected return migrants. We show that assimilation patterns vary substantially across sending countries and persist in the second generation.

I. Introduction

We study the assimilation of European immigrants in the US labor market during the Age of Mass Migration (1850–1913), one of the largest migration episodes in modern history. Almost 30 million immigrants moved to the United States during this period; by 1910, 22 percent of the US labor force was foreign-born, compared with only 17 percent today. At the time, US borders were completely open to European immigrants. Yet, much like today, contemporaries were concerned about the ability of migrants to assimilate into the US economy. Congress fought with various presidential administrations about whether to tighten immigration policies for over 30 years before finally imposing strict quotas in 1924, putting an end to the era of open borders.

Our paper challenges conventional wisdom and prior research about immigrant assimilation during this period1. The common view is that European immigrants held substantially lower-paid occupations than natives upon first arrival but that they converged with the native-born after spending some time in the United States2. Using newly assembled panel data for 21,000 natives and immigrants from 16 sending European countries, we instead find that, on average, long-term immigrants from sending countries with real wages above the European median actually held significantly higher-paid occupations than US natives upon first arrival, while immigrants from sending countries with below-median wages started out in equal or lower-paid occupations3. We find little evidence for the commonly held view that immigrants converged with natives but rather document substantial persistence of the initial earnings gap between immigrants and natives (whether positive or negative) over the life cycle. In other words, regardless of starting point, immigrants experienced occupational upgrading similar to that of natives, thereby preserving the initial gaps between immigrants and natives over time. Furthermore, this gap persisted into the second generation; when migrants from a certain source country out-performed US natives, so did second-generation migrants, and vice versa4.

Prior studies used cross-sectional data, which confound immigrant convergence to natives in the labor market with immigrant arrival cohort effects and the selection of return migrants from the migrant pool. Indeed, when we use cross-sectional data, we confirm the findings of prior studies. When contrasting these findings with those using our panel data, we conclude that the apparent convergence in a single cross section is driven by a decline in the quality of immigrant cohorts over time and the departure of negatively selected return migrants (see Borjas [1985] and Lubotsky [2007] for discussions of these sources of bias in contemporary data)5.

We conclude that the notion that immigrants faced a large initial occupational penalty during the historical Age of Mass Migration is over-stated. Even when US borders were open, the average immigrant who ended up settling in the United States long-term held occupations that commanded pay similar to that of US natives upon first arrival6. These findings suggest that migration restrictions or selection policies are not necessary to ensure strong migrants’ performance in the labor market.

At the same time, the notion that European immigrants converged with natives after spending 10–15 years in the United States is also ex-aggerated, as we find that initial immigrant-native occupational gaps persisted over time and even across generations. This pattern casts doubt on the conventional view that, in the past, immigrants who arrived with few skills were able to invest in themselves and succeed in the US economy within a single generation.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section II discusses the historical context and related literature. Section III reviews methods used to infer immigrant assimilation in cross-sectional and panel data settings and the biases associated with each. In Section IV, we describe the data construction and matching procedures. Section V presents our empirical strategy and main results on immigrant assimilation and the selection of return migrants. Section VI contains country-by-country results on assimilation and return migration. In Section VII, we assess the robustness of our main findings and present occupational transition matrices that provide more detail about how immigrants and natives moved up the occupational ladder over time. Section VIII rules out other sources of selective attrition from the panel sample beyond return migration, including selective mortality or name changes. Section IX analyzes the performance of second-generation immigrants relative to their parents, and Section X presents conclusions.

II. Immigrant Assimilation in the Early Twentieth Century: Historical Context and Related Literature

The United States absorbed 30 million migrants during the Age of Mass Migration (1850–1913). By 1910, 22 percent of the US labor force—and 38 percent of workers in nonsouthern cities—were foreign-born (compared with 17 percent today)7. Over the period, migrant-sending countries shifted toward the poorer regions of southern and eastern Europe (Hatton and Williamson 1998). Many contemporary observers expressed concerns about the concentrated poverty in immigrant neighborhoods and the low levels of education among immigrant children, many of whom left school at young ages in order to work in textiles and manufacturing (Muller 1993; Moehling 1999). Prompted by these concerns, progressive reformers championed a series of private initiatives and public legislation, including child labor laws and compulsory schooling requirements, to facilitate immigrant absorption (Lleras-Muney 2002; Carter 2008; Lleras-Muney and Shertzer 2011), while nativists instead believed that new arrivals would never be able to fit into American society (Higham 1988; Jacobson 1999).

Fears about immigrant assimilation encouraged Congress to convene a special commission in 1907 to study the social and economic conditions of the immigrant population. The resulting report concluded that immigrants, particularly from southern and eastern Europe, would be unable to assimilate, in part because of high rates of temporary and return migration8. The Immigration Commission report provided fuel for legislators seeking to restrict immigrant entry (Benton-Cohen 2010). In 1917, Congress passed a literacy test, which required potential immigrants to demonstrate the ability to read and write in any language (Goldin 1994). In 1924, Congress further restricted immigrant entry by setting a strict quota of 150,000 arrivals per year, with more slots allocated to northern and western European countries.

Since the publication of the Immigration Commission report, generations of economists and economic historians have assessed the labor market performance of this large wave of immigrant arrivals9. The earliest studies in this area (re-) analyzed the aggregate wage data published by the Immigration Commission and found that, contrary to the initial conclusions of the commission, immigrants caught up with the native-born after 10–20 years in the United States (Higgs 1971; McGouldrick and Tannen 1977; Blau 1980). Related work examined individual-level wage data from surveys conducted by state labor bureaus (Hannon 1982; Eichengreen and Gemery 1986; Hanes 1996). Although early studies of these sources found no wage convergence, Hatton (1997) argues that this discrepancy is due to specification choice. He reanalyzes the state data with two simple modifications and finds that immigrants who arrived at age 25 fully erased the wage gap with natives within 13 years in the United States10.

More recent studies on immigrant assimilation incorporate data from the federal census of population. The census offers complete industrial and geographic coverage but contains information only on occupation rather than on individual wages or earnings. Relying on the 1900 and 1910 census cross sections, Minns (2000) finds partial convergence between immigrants and natives outside of the agricultural sector11. Immigrants eliminate 30–40 percent of their (between-occupation) earnings deficit relative to natives after 15 years in the United States.

Overall, across three different data sets, the existing literature suggests that immigrant workers experienced substantial occupational and earnings convergence with the native-born in the early twentieth century. However, all these analyses compare earnings in a single cross section, a method that suffers from two potentially important sources of bias: selective return migration and changes in immigrant cohort quality over time12.

III. Inferring Immigrant Assimilation from Cross-Sectional and Panel Data

Imagine that the researcher has only a single cross section of data, say the 1920 census, from which to estimate the pace of convergence between immigrants and the native-born in the labor market. In this case, she may compare the earnings of a long-standing immigrant who arrived in the United States in 1895 to that of a recent immigrant who arrived in 1915. For illustration, let the mean earnings of a native-born worker be $100. If the immigrant who arrived in 1895 also earned $100 in 1920 while the immigrant who arrived in 1915 earned $50, the researcher could conclude that, upon arrival, migrants faced an earning penalty relative to natives that is completely erased after 25 years in the United States. However, this conclusion might mistake differential skills across arrival cohorts for true migrant assimilation; this point was first made by Douglas (1919) and was developed by Borjas (1985)13. If, for example, the long-standing migrant was a literate craftsman from Germany whereas the recent arrival was an unskilled common laborer from Italy, the difference in their earnings in 1920 may reflect permanent gaps in their skill levels rather than temporary gaps due to varying time spent in the United States.

This bias can be addressed with repeated cross-sectional observations on arrival cohorts, say by observing 1895 immigrant arrivals in both the 1900 and 1920 censuses. However, in this case, inferences on migrant assimilation may still be inaccurate because of selective return migration; this point was first made by Jasso and Rosenzweig (1988) and was investigated empirically by Lubotksy (2007)14. In the 1900 census, the 1895 migrant arrival cohort contains both temporary arrivals who will return to their home country before the 1920 census and longer-standing immigrants who will remain in the United States in 1920. By 1920, only the long-standing immigrants remain. If the temporary migrants have lower skills or exert less effort in moving up the occupational ladder in the United States, this compositional change in the repeated cross section will generate the appearance of wage growth within the cohort over time as the lower-earning migrants return to Europe15.

We emphasize that in our panel data we estimate an assimilation profile for immigrants who were in the United States in both 1900 and 1920, that is, those who remained in the United States for at least 20 years. These immigrants are of particular interest because they participate in the US labor market for many years and are more likely to raise children in the United States who then contribute to the labor force in the next generation. However, to understand the experience of the typical migrant in the United States at a point in time, a group that includes both permanent migrants and migrants who will later return to their home country, the assimilation patterns in the repeated cross sections are also of interest.

For a set of earlier papers, we compiled a panel data set of immigrants that matched individuals from their childhood household in Europe to their adult outcomes; in this case, we were able to focus on only a single sending country, Norway (Abramitzky, Boustan, and Eriksson 2012, 2013). These data allowed us to analyze the selection of who migrates from Europe to the United States and the economic return to this migration. We found evidence of negative selection in the sense that men whose fathers did not own land or whose fathers held low-skilled occupations were more likely to migrate. We also estimated a return to migration free from between-household selection by comparing brothers, one of whom migrated and one of whom stayed in Norway; using this method, we found a return to migration of around 70 percent. In this paper, we use panel data to compare immigrants to US natives (assimilation) rather than to compare immigrants to the European sending population (selection). Furthermore, we move beyond our focus on a single country and assemble new panel data for immigrants from 16 sending countries.

IV. Data and Matching

A. Matching Men between the 1900, 1910, and 1920 US Censuses

Our analysis relies on a new panel data set that follows native-born workers and immigrants from 16 sending countries through the US censuses of 1900, 1910, and 1920. We match individuals over time by first and last name, age, and country or state of birth; details on the matching procedure are provided in Appendix A. We restrict our attention to men between the ages of 18 and 35 in 1900, an age range in which men are both old enough to be employed in 1900 and young enough to still be in the workforce in 1920. We further limit the immigrant portion of the sample to men who arrived in the United States between 1880 and 1900. For comparability with the foreign-born, 95 percent of whom live outside of the South, we exclude native-born men residing in a southern state and all black natives regardless of place of residence16. We compare results in this panel data set to similarly defined cross sections of the population drawn from the census public use samples of 1900, 1910, and 1920 (Ruggles et al. 2010).

Table 1 presents match rates and final sample sizes for each sending country and for native-born men in the panel sample. Our matching procedure generates a final sample of 20,225 immigrants and 1,650 natives. We can successfully match 16 percent of all native-born men forward from 1900 to both 1910 and 1920. For the foreign-born, the average forward match rate across countries is lower (12 percent), which is expected given that a sizable number of migrants return to Europe between 1900 and 1920. These double match rates are similar to those in Ferrie (1996) and Abramitzky et al. (2012)17.

TABLE 1.

Sample Sizes and Match Rates by Place of Birth

| Country | 1900 Number in Universe (1) |

Number Matched (2) |

Match Rate, Total (3) |

1900 Number, Unique (4) |

Match Rate, Unique (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. 1900 Source: IPUMS |

|||||

| Austria | 4,835 | 339 | .070 | 4,677 | .072 |

| England | 7,438 | 664 | .089 | 6,175 | .107 |

| France | 11,615 | 728 | .063 | 9,139 | .079 |

| Germany | 19,855 | 2,248 | .113 | 16,733 | .134 |

| Ireland | 9,737 | 861 | .088 | 6,323 | .136 |

| Italy | 7,624 | 811 | .106 | 7,042 | .115 |

| Norway | 3,541 | 425 | .120 | 2,822 | .151 |

| Russia | 5,804 | 644 | .111 | 5,203 | .124 |

| Sweden | 6,164 | 559 | .091 | 4,070 | .137 |

| US natives | 10,000 | 1,650 | .165 | 8,345 | .197 |

|

|

|||||

| B. 1900 Source: Ancestry.com |

|||||

| Belgium | 6,060 | 545 | .090 | 5,962 | .091 |

| Denmark | 34,594 | 1,980 | .058 | 17,425 | .114 |

| Finland | 23,843 | 828 | .035 | 22,197 | .037 |

| Portugal | 12,585 | 584 | .046 | 8,362 | .070 |

| Scotland | 53,091 | 4,349 | .082 | 15,529 | .280 |

| Switzerland | 22,276 | 3,311 | .149 | 20,588 | .161 |

| Wales | 17,767 | 1,342 | .076 | 9,876 | .135 |

Note.—The sample universe includes men between the ages of 18 and 35 in 1900. Immigrants must have arrived in the United States between 1880 and 1900. We exclude all blacks and native-born men living in the South. For large sending countries and the native-born, we start with the 1900 IPUMS sample (panel A). For smaller sending countries, we begin with the complete population in 1900. The text describes our matching procedure. The number of matched cases refers to men who match to both the 1910 and 1920 censuses. We report the number of unique cases by first name, last name, age, and country of birth and the match rate for this group in cols. 4 and 5.

Despite the fact that men with uncommon names are more likely to match between census years, our matched sample is reasonably representative of the population. Appendix table A1 compares the occupation-based earnings of men in the matched sample to men in the full population in 1920 (the earnings measure is described in the next section). By definition, men in both the panel data and the 1920 cross section must have survived and remained in the United States until 1920. Thus, by 1920, up to any sampling error, differences between the panel and the representative cross section must be due to an imperfect matching procedure. Among natives, the difference in the mean occupation score in the matched sample and the population in 1920 is small ($37) and statistically indistinguishable from zero. In contrast, immigrants in the matched sample have a $300 advantage over immigrants in the representative sample. Therefore, up to $300 of the occupation-based earnings differential between immigrants and natives in the panel data could be due to sample selection induced by our matching procedure.

B. Occupation and Earnings Data

We observe labor market outcomes for our matched sample in 1900, 1910, and 1920. Because these censuses do not contain individual information about wages or income, we assign individuals the median income in their reported occupation18. Table 2 reports the 10 most common occupations for our sample of matched natives and foreign-born workers. Although the top 10 occupations are similar for both groups, migrants to the United States were less likely to be farmers (18 vs. 26 percent) and more likely to be managers or foremen (14 vs. 10 percent). The native-born were also more likely to be salesmen and clerks, two occupations with high returns to fluency in English. Other common occupations in both groups include operatives and general laborers19.

TABLE 2.

Common Occupations for Natives and Foreign-Born in Matched Sample, 1920

| Natives |

Foreign-Born |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | Frequency | Percent | HISCLASS | Occupation | Frequency | Percent | HISCLASS |

| Farmer | 282 | 25.99 | 8 | Farmer | 3,141 | 18.43 | 8 |

| Manager | 89 | 8.20 | 9 | Manager | 1,863 | 10.93 | 9 |

| Laborer | 83 | 7.65 | 12 | Laborer | 1,616 | 9.48 | 12 |

| Salesman | 58 | 5.44 | 5 | Operative | 1,020 | 5.99 | 5 |

| Operative | 54 | 4.98 | 9 | Foreman | 576 | 3.38 | 3 |

| Clerical | 43 | 3.96 | 5 | Mine operative | 575 | 3.37 | 9 |

| Carpenter | 36 | 3.32 | 7 | Machinist | 550 | 3.23 | 9 |

| Machinist | 35 | 3.23 | 9 | Carpenter | 493 | 2.89 | 7 |

| Farm laborer | 33 | 3.04 | 12 | Salesman | 444 | 2.61 | 5 |

| Foreman | 21 | 1.94 | 3 | Clerical | 314 | 1.84 | 5 |

| Total (top 10) | 714 | 65.81 | 10,278 | 60.31 | |||

| Outside top 10 | 371 | 34.19 | 6,763 | 39.69 | |||

Note.—See the note to table 1 for sample restrictions. HISCLASS is a 12-part classification system indicating the social class of each occupation (van Leeuwen and Maas 2005).

Our primary source of income data is the “occupational score” variable constructed by IPUMS. This score assigns to an occupation the median income of all individuals in that job category in 1950. For ease of interpretation, we convert this measure into 2010 dollars. Using this measure, our data set contains individuals representing around 125 occupational categories. Occupation-based earnings are a reasonable proxy for “permanent” income, by which we can measure the extent to which immigrants assimilate with natives in social status.

One benefit of matching occupation to earnings in a single year is that our measure of movement up the occupational ladder will not be confounded by changes in the income distribution. Butcher and DiNardo (2002), for example, point out that much of the growth in the immigrantnative wage gap between 1970 and 1990 was due to widening income inequality (see also Lubotsky 2011). Given that immigrants today are clustered in low-skill jobs, their wages stagnated while the wages of some natives grew. Although the growth in the immigrant-native wage gap is “real” in the sense that immigrants had lower purchasing power in 1990 than they did in 1970, it does not necessarily reflect a decline in immigrants’ social standing or ability to assimilate into the US economy.

Yet our reliance on occupation-based earnings prevents us from measuring the full convergence between immigrants and natives. In particular, we are able to capture convergence due to advancement up the occupational ladder (between-occupation convergence), but we cannot measure potential convergence between immigrants and natives in the same occupation. To assess the extent of this bias, we use data from the 1970 and 1980 IPUMS samples, the first census years to record both wage data and year of immigration for the foreign-born. We find that occupation-based earnings capture around 30 percent of the initial earnings penalty in the cross section and 65 percent in repeated cross sections20. Similarly, occupation-based earnings account for 30 percent of total convergence between immigrants and natives in the cross section and can explain all of the (much lower) earnings convergence in the repeated cross sections21. It is reasonable to conclude, then, that our measure is able to capture at least 30 percent of true earnings convergence (although note that inferring occupational advancement from cross-sectional data suffers from the biases described above).

A further concern with the IPUMS occupation score variable is its anchoring to occupation-based earnings in the year 1950. The 1940s–1950s was a period of wage compression (Goldin and Margo 1992). If immigrants were clustered in low-paying occupations, the occupation score variable may understate both their initial earnings penalty and the convergence implied by moving up the occupational ladder. We address this concern by using occupation-based earnings from the 1901 Cost of Living survey as an alternative dependent variable (Preston and Haines 1991)22. We also try extrapolating the 1950 occupation-based earnings back to the early 1920s using a time series of earnings by broad occupation category (clerical, skilled blue-collar, and unskilled blue-collar) reported in Goldin and Margo (1992).

V. Immigrant Assimilation in Panel Data

A. Occupational Distribution of Immigrants and Natives in 1900

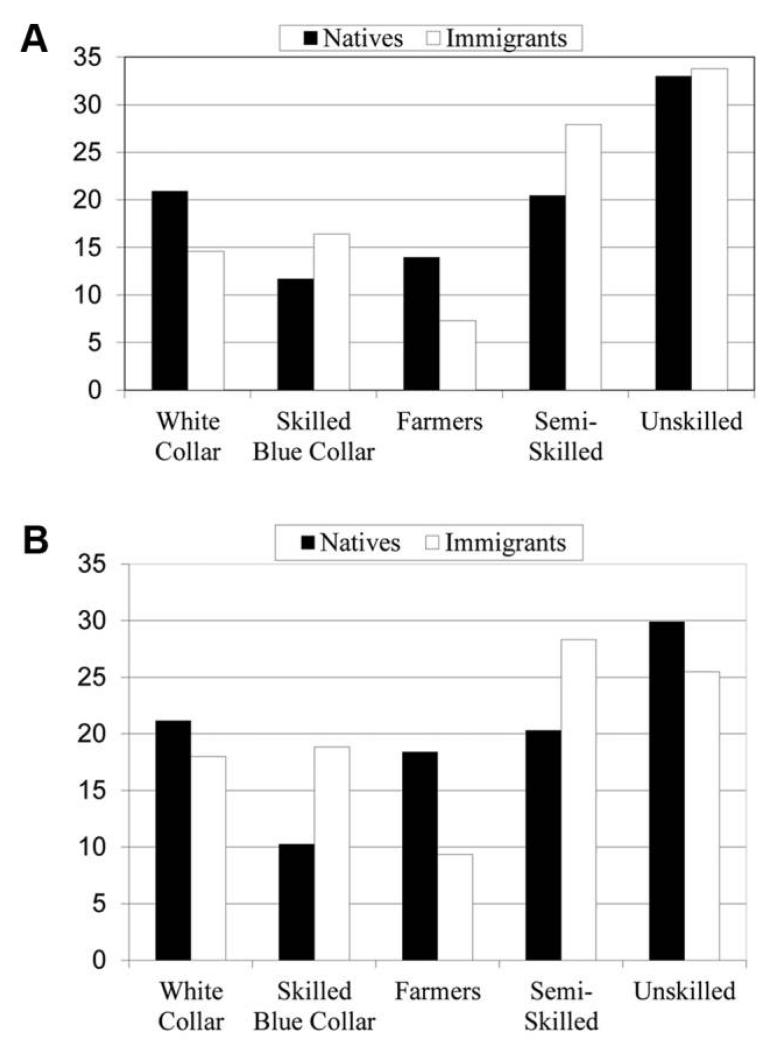

Before turning to occupation-based earnings measures, we illustrate our main findings in a series of charts in figure 1. These charts match individuals’ reported occupations to social classes using the Historical International Social Class Scheme (HISCLASS) developed by van Leeuwen and Maas (2005) and then further group these codes into five categories: white-collar, skilled blue-collar, farmers, semiskilled blue-collar, and unskilled. For reference, we also report the average earnings of these social classes in table 3. These results, and all others, are reweighted so that the panel sample reflects the actual distribution of country of origin in the 1920 population.

Fig. 1.

—Occupational distribution of natives and immigrants in cross section and panel in 1900. A, Cross section, immigrants and natives. B, Panel, immigrants and natives. C, Cross section, immigrants in early and late arrival cohorts. D, Panel, immigrants in early and late arrival cohorts.

TABLE 3.

Mean Earnings by Nativity and Social Class in 1901 and 1950 Data in Panel Sample

| 1901 ($) | 1950 ($) | |

|---|---|---|

| All immigrants | 17,939 | 22,698 |

| All natives | 18,106 | 21,357 |

| White-collar | 24,337 | 30,906 |

| Skilled blue-collar | 19,058 | 26,604 |

| Farmers | 21,324 | 12,609 |

| Semiskilled | 15,757 | 23,085 |

| Unskilled | 8,583 | 13,554 |

Note.—Figures are reported in 2010 dollars. Occupations are classified according to the HISCLASS rubric: HISCLASS 1–5 = white-collar; HISCLASS 6–7 = skilled blue-collar; HISCLASS 8 = farmers; HISCLASS 9 = semiskilled; HISCLASS 10–12 = unskilled.

Each panel of figure 1 graphs the occupational distributions of different groups of men in 1900, either in the representative cross section or in the panel sample. Figures 1A and 1B compare immigrants to the nativeborn. Although, on average, immigrants and natives held similarly paid occupations (see table 3), the native-born were more likely to hold white-collar positions (such as salesmen) likely and to be farmers, while immigrants were more to engage in skilled or semiskilled blue-collar work (carpenter, machinist). Immigrants and natives were roughly equally likely to be unskilled. These occupation distributions suggest that whether or not immigrants faced a wage penalty or a wage premium relative to natives may be sensitive to the placement of farmers in the earnings distribution.

Comparing the full population in the cross section (fig. 1A) with the panel sample (fig. 1B) informative. First, long-term immigrants were less likely than the typical immigrant in 1900 to hold unskilled positions (25 percent vs. 34 percent). The difference in the probability of engaging in unskilled work is made up by the fact that long-term immigrants are more likely to be farmers or to hold white-collar or skilled blue-collar positions. These occupational differences suggest that there was negatively selected attrition from the cross section consisting of unskilled temporary migrants who returned to Europe. Second, beyond being slightly more likely to be farmers, there are no other notable differences between the natives in the cross section and those in the panel, which is consistent with a lack of other forms of selective attrition in the data (e.g., due to mortality). Section VIII discusses other sources of potential selective attrition in more detail.

Earlier- and later-arriving immigrants are compared in figures 1C and 1D. Immigrants who arrived in the 1890s are substantially more likely than immigrants who arrived in the 1880s to be unskilled workers in 1900 (41 percent vs. 26 percent). Much of this difference is due to the lower skills of this later cohort and does not disappear with age. The gap between these arrival cohorts is smaller but still apparent among long-term immigrants in the panel sample.

B. Estimating Equation

Our main analysis compares the occupational mobility of native-born and immigrant workers. We estimate

| (1) |

where i denotes the individual, j denotes the country of origin, m is the year of arrival in the United States, t is the (census) year, and t − m is thus the number of years spent in the United States. Occupation score is a proxy for labor market earnings that varies between (but not within) occupations. The coefficients β1 through β4 relate years of labor market experience to the worker’s position on the occupational ladder23.

A vector of indicator variables γt−m separates the foreign-born into five categories according to time spent in the United States (0–5 years, 6–10 years, 11–20 years, 21–30 years, and 30 or more years), with the native-born constituting the omitted category. The sign and magnitude of the coefficient on the first dummy variable (0–5 years) indicate whether immigrants received an occupation-based earnings penalty (or premium) upon first arrival to the United States, whereas the remaining dummy variables reveal whether immigrants eventually catch up with or surpass the occupation-based earnings of natives. Our main specification divides the foreign-born into two year-of-arrival cohorts indicated by μm (arrivals before and after 1890) to allow for differences in occupation-based earnings capacity by arrival year; Section VII explores the sensitivity of the results to the choice of the number of arrival cohorts. Observations are weighted to reflect the actual distribution of country of origin in the 1920 population24.

We begin by estimating two versions of equation (1) using pooled data from the 1900, 1910, and 1920 IPUMS samples. The first specification omits the arrival cohort dummy (μm), thereby comparing immigrants in the United States for various lengths of time both between and within arrival cohorts. We refer to this specification as the “cross-section” model. We then add the arrival cohort dummy and reestimate equation (1). We refer to this specification as the “repeated cross-section” model because it follows arrival cohorts across census waves. Comparing the cross section and the repeated cross section allows us to infer how much of the initial occupational penalty can be attributed to differences in the quality of arrival cohorts. Note that, because we include country fixed effects, we measure differences in arrival cohorts within sending countries over time.

Finally, we compare the repeated cross-section results with estimates of equation (1) in the panel sample. The panel data follow individuals, rather than arrival cohorts, across census waves. Therefore, comparing the estimates in the repeated cross section and the panel allows us to infer whether and to what extent return migrants were positively or negatively selected from the immigrant population. If we observe more (less) convergence in the repeated cross section than in the panel, we can infer that the temporary migrants are drawn from the lower (upper) end of the occupation-earnings distribution, thereby leading their departure to increase (decrease) the immigrant average.

C. Occupational Convergence in Cross-Section and Panel Data

In this subsection, we estimate equation (1) using occupation-based earnings, first using data from the 1950 census and then using data from the 1901 Cost of Living survey. We show that, with both earnings measures, (1) in the cross section, immigrants initially hold lower-paid occupations but converge on natives over time; (2) following arrival cohorts from 1900 to 1920 in the repeated cross sections reduces the initial migrant disadvantage; and (3) long-term immigrants in the panel data look even closer to natives upon first arrival, closing the earnings gap completely when using the 1950 occupation-based earnings data and drawing closer to but not completely converging with natives in the 1901 earnings data. That is, the apparent immigrant disadvantage in a single cross section is driven by the lower quality of later arrival cohorts (1890s vs. 1880s) and the negative selection of temporary migrants who eventually return to Europe.

We begin by discussing the results when occupations are matched to 1950 earnings, as presented in table 4. In the cross section, new immigrants hold occupations that earn $1,200 below natives of similar age and appear to completely make up this gap over time (col. 1, in 2010 dollars). Columns 2 and 3 pool data from the cross section and panel and report the interactions between being in the cross section (or the panel) and the indicators for years spent in the United States and for arrival cohort25. When we simply control for arrival cohort in column 2, the occupation score gap between recently arrived immigrants and natives shrinks to $400. In other words, even within sending countries, around three-quarters of the initial gap in the pooled cross section is due to the lower occupational skills of immigrants who arrived after 189026. Indeed, immigrants who arrived after 1890 had significantly lower occupation-based earnings than earlier arrivals, receiving an arrival cohort penalty of $750.

TABLE 4.

Ordinary Least Squares Estimates, Age-Earnings Profile for Natives and Foreign-Born, 1900–1920: 1950 Occupation-Based Earnings in 2010 Dollars

| Pooled Cross Section and Panel |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Right-Hand-Side Variable | Cross Section (1) |

Cross Section Coefficients (2) |

Panel Coefficients (3) |

| 0–5 years in US | −1,255.73 (143.44) |

−384.49 (187.30) |

293.51 (237.96) |

| 6–10 years in US | −734.51 (147.44) |

−2.89 (172.05) |

467.64 (213.61) |

| 11–20 years in US | −352.93 (131.27) |

173.83 (134.02) |

329.38 (150.49) |

| 21–30 years in US | −294.87 (142.10) |

128.44 (138.93) |

74.34 (150.33) |

| 30 years in US | 22.41 (184.65) |

155.77 (178.49) |

231.90 (186.55) |

| Arrive 1891+ | … | −739.18 (106.99) |

−232.77 (160.58) |

| Native-born | … | … | −153.83 (176.14) |

| Observations | 205,458 | 259,093 | |

Note.—See the table 1 note for sample restrictions. Columns report coefficients from estimation of eq. (1). Column 1 pools three cross sections (1900–1920); the regression in cols. 2 and 3 adds the matched panel sample. The coefficients in col. 2 are interactions between the right-hand-side variables listed and a dummy for being in the cross section, and col. 3 reports interactions between the right-hand-side variables and a dummy for being in the panel. The omitted category is native-born men in the cross section. Coefficients on age, census year dummies, and country-of-origin fixed effects are not shown.

Coefficients for the panel data are reported in column 3. In this case, occupation-based earnings gaps between immigrants and natives are found by subtracting the coefficient for the native-born from each coefficient for years spent in the United States. For this subsample of long-term migrants, we find no initial occupation score gap between immigrants and natives. If anything, immigrants start out about $450 ahead of natives (= 293 + 153), although a gap of this size may be partially due to differential selection into the matched sample (see Sec. IV.A)27. The immigrant-native occupation-based earnings gaps in the repeated cross section and the panel are statistically different from each other for immigrants who arrived between 0–5 and 6–10 years ago. This comparison suggests that the observed occupation-based earnings gap in the repeated cross section is capturing the negative selection of immigrants who end up returning to Europe.

Note that the difference between the 0–5 years in the United States coefficients in the panel and repeated cross section reflects the occupation-based earnings gap between long-term migrants and a weighted average of temporary and longer-term migrants. This gap can be used to back out the differential in occupation-based earnings between long-term and temporary migrants. For a country experiencing a 25 percent return migration rate (see n. 5), the gap of $678 (= 293 + 384) implies that the typical return migrant held an occupation that earned $2,700 (or 12 percent) less than the average migrant who remained in the United States28.

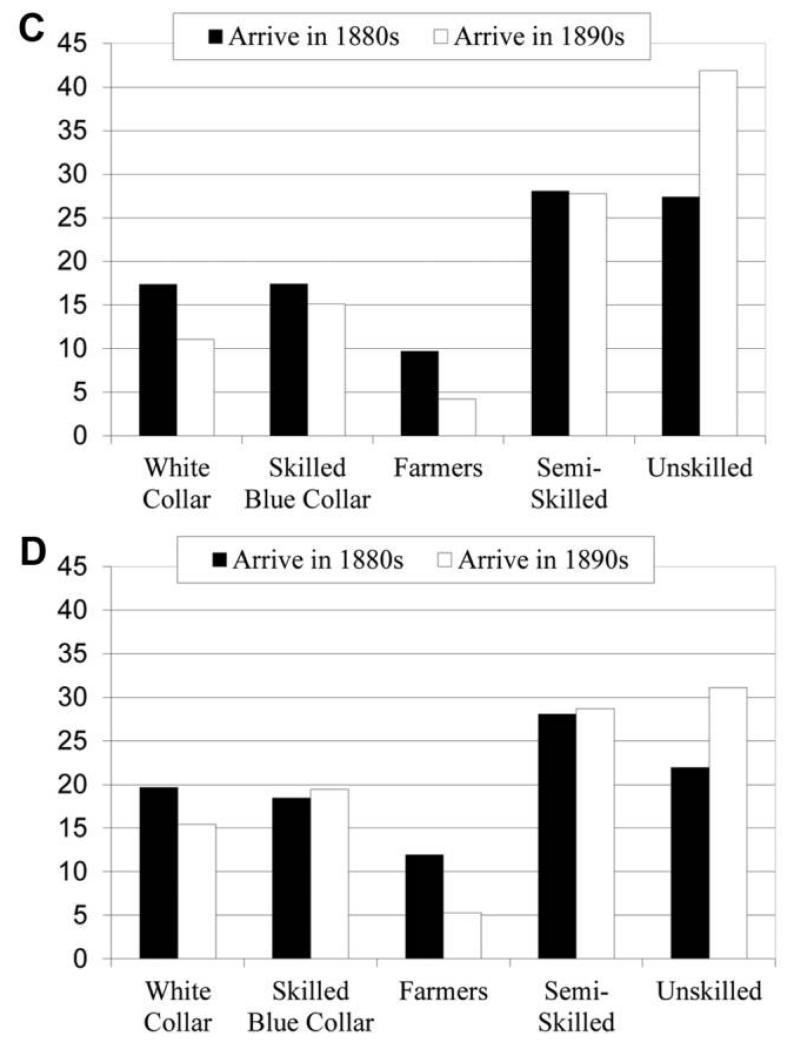

The differences in the initial immigrant-native gaps and implied rates of convergence between the cross-section and panel samples are underscored in figure 2. This figure graphs the coefficients on the 5 years in the United States dummy variables in the pooled cross section and the repeated cross sections and the difference between the native-born dummy and the years in the United States indicators for the panel sample. In graphical form, it is even easier to see that, in the cross section, immigrants appear to face an occupation score gap relative to natives upon first arrival but are able to erase this gap over time. In contrast, according to the repeated cross section line, immigrants in the pre-1890 arrival cohort experienced a much smaller occupation score gap relative to natives upon first arrival. Finally, permanent immigrants in the panel data hold slightly higher-paying occupations than natives, even upon first arrival, and retain this advantage over time. Of the $1,600 difference between the immigrant occupation-based earnings penalty observed in the cross section and the immigrant earnings premium in the panel, around 55 percent can be attributed to arrival cohort skill level (= −$384 − [−$1,255]) and the remaining 45 percent can be attributed to the negative selection of return migrants (= [$293 − $153] − [ −$384]).

Fig. 2.

—Convergence in occupation score between immigrants and native-born workers by time spent in the United States, cross-sectional and panel data, 1900–1920. The graph plots coefficients for years spent in the United States indicators in equation (1). Note that for the panel line, we subtract the native-born dummy from the years in the United States indicators (because the omitted category in that regression is natives in the panel sample). See table 4 for coefficients and standard errors.

Table 5 repeats the analysis using occupation-based earnings from the 1901 Cost of Living survey. When occupations are matched to the 1901 earnings in panel A, immigrants in the cross section appear to have a much larger initial occupation-based earnings gap with natives ($4,200 in 2010 dollars vs. $1,200 when matched to the 1950 occupation-based earnings data in table 4). Yet, despite differences in the size of the initial gap between the two data sources, we continue to find here that a large portion of the observed convergence in the cross section is driven by biases due to changes in arrival cohort skill level and negatively selected return migration.

TABLE 5.

Ordinary Least Squares Estimates, Age-Earnings Profile for Natives and Foreign-Born, 1900–1920: 1901 Occupation-Based Earnings in 2010 Dollars

| Pooled Cross Section and Panel |

Pooled Cross Section and Panel |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross Section (1) |

Repeated Cross Section (2) |

Panel (3) |

Cross Section (4) |

Repeated Cross Section (5) |

Panel (6) |

|

| A. 1901 Income |

B. 1950 Income with Adjustments |

|||||

| 0–5 years in US | −4,176.52 (122.47) |

−3,286.33 (150.51) |

−2,558.65 (200.05) |

−3,186.66 (138.04) |

−2,364.00 (175.45) |

−2,354.07 (240.66) |

| 6–10 years in US | −3,433.90 (130.80) |

−2,723.76 (144.10) |

−1,900.42 (174.11) |

−2,450.13 (144.89) |

−1,797.87 (165.09) |

−1,521.15 (206.19) |

| 11–20 years in US | −2,670.61 (117.84) |

−2,200.14 (115.74) |

−1,859.93 (124.76) |

− 1,783.47 (131.08) |

−1,361.64 (131.68) |

−1,241.91 (145.40) |

| 21–30 years in US | −2,402.06 (124.08) |

−2,032.18 (117.95) |

−1,896.77 (124.79) |

−1,540.32 (139.89) |

−1,227.39 (135.54) |

−1,127.69 (146.22) |

| 30 years in US | −1,906.83 (148.13) |

−1,773.97 (139.57) |

−1,634.05 (144.52) |

−1,146.96 (175.02) |

−1,107.02 (168.41) |

−814.98 (177.33) |

| Arrive 1891+ | … | −740.37 (82.96) |

−284.08 (127.89) |

−745.86 (97.89) |

−20.58 (150.86) |

|

| Native-born | … | … | 580.02 (200.05) |

28.22 (145.85) |

||

| Observations | 204,134 | 261,079 | 204,134 | 261,079 | ||

Note.—Columns 1–3 follow the format of table 4 using income from the 1901 Cost of Living survey. Columns 4–6 adjust the 1950 occupation-based earnings to match the Cost of Living survey in three ways: using only urban workers to calculate occupation-based earnings, using mean rather than median earnings by occupation, and using the census of agriculture rather than the census of population to infer earnings of farmers.

Panel B of table 5 explores the source of the larger initial occupation-based earnings gap between immigrants and natives in the 1901 data. In particular, we make three adjustments to the 1950 occupation-based earnings to match the attributes of the Cost of Living survey: using only urban workers to calculate occupation-based earnings; using mean, rather than median, earnings by occupation; and using the 1900 Census of Agriculture rather than the 1950 Census of Population to infer earnings of farmers. Together, these three adjustments can account for 70 percent of the difference in the estimated coefficients generated by these two income sources29. We favor the 1950 occupation-based earnings because it covers the entire population, both rural and urban, and because it places farmers below the median of the income distribution, which is consistent with the fact that, as a profession, farming was declining in earning power and social status over the early twentieth century30.

D. Geographic Location in the United States

In table 6, we adjust for aspects of immigrants’ location choices within the United States, first by controlling for state of residence and then by separately considering the urban subsample. Controlling for state of residence raises concerns about endogenous location choice; however, we believe that these specifications shed light on the mechanism underlying the occupation-based earnings difference between immigrants and natives.

TABLE 6.

Ordinary Least Squares Estimates, Age-Earnings Profile for Natives and Foreign-Born, 1900–1920, Taking Geography into Account

| Pooled Cross Section and Panel |

Pooled Cross Section and Panel |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right-Hand-Side Variable |

Cross Section (1) |

Cross Section (2) |

Panel (3) |

Cross Section (4) |

Cross Section (5) |

Panel (6) |

| A. Add State Fixed Effects |

B. Urban Residents Only |

|||||

| 0–5 years in US | −2,679.42 (154.57) |

−1,696.95 (198.43) |

−955.81 (242.28) |

−4,209.72 (179.89) |

−3,355.25 (232.60) |

−1,983.01 (304.03) |

| 6–10 years in US | −2,125.78 (158.64) |

−1,323.73 (182.91) |

−817.13 (216.28) |

−3,450.40 (180.64) |

−2,749.18 (210.87) |

−1,567.89 (266.92) |

| 11–20 years in US | −1,662.49 (141.99) |

−1,123.49 (143.23) |

−802.01 (155.94) |

−2,752.16 (161.14) |

−2,240.59 (165.61) |

−1,708.59 (187.95) |

| 21–30 years in US | −1,473.55 (153.48) |

−1,045.93 (149.28) |

−1,024.76 (155.92) |

−2,329.79 (173.94) |

−1,913.40 (170.52) |

−2,188.47 (191.53) |

| 30+ years in US | −1,059.34 (195.52) |

−955.81 (187.71) |

−804.77 (189.56) |

−1,867.16 (224.75) |

−1,748.92 (216.93) |

−2,069.28 (236.96) |

| Arrive 1891+ | … | −907.09 (110.94) |

−309.26 (161.97) |

… | −770.35 (126.49) |

−365.21 (199.18) |

| Native-born | … | … | −156.52 (172.08) |

… | … | −258.68 (238.42) |

| Observations | 194,383 | 247,378 | 110,934 | 137,726 | ||

Note.—Regressions follow the format of table 4. Panel A adds a vector of state fixed effects and panel B limits the sample to men living in urban areas in 1900. We define urban areas as counties in which at least 40 percent of the county’s residents lived in a town with a population of 2,500 or more.

Panel A of table 6 adds state fixed effects, implicitly comparing immigrants and natives who settled in the same state. This adjustment doubles the immigrant occupation-based earnings penalty in the cross section and converts the small occupation-based earnings premium into an earnings penalty of $800 for long-term immigrants in the panel sample. In a comparison of these findings to the main results in table 4, it appears that immigrants achieved earnings parity with natives by moving to locations with a well-paid mix of occupations (Borjas 2001)31. The immigrant-native occupation-based earnings gap varies by state; immigrants outearn natives in the industrial states of the Midwest (e.g., Ohio, Illinois, and Michigan) and underperform natives in industrial New England (Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island) and the Great Plains (the Dakotas, Iowa, Nebraska, and Minnesota)32. Furthermore, we find an even larger occupation-based earnings gap between immigrants and natives when restricting the sample to urban residents in panel B ($4,200 upon first arrival in the cross section and $1,700 [= −1,983 + 258] upon first arrival in the panel), perhaps because less productive immigrants settled in cities to take advantage of the larger ethnic networks and the presence of immigrant aid societies33. Note that although the immigrant occupation-based earnings penalty is larger in both cases, we continue to find that immigrants and natives experience little convergence in the panel sample and that long-term immigrants held occupations that pay more than those of the average immigrant, consistent with negatively selected return migration.

VI. Heterogeneity by Sending Country

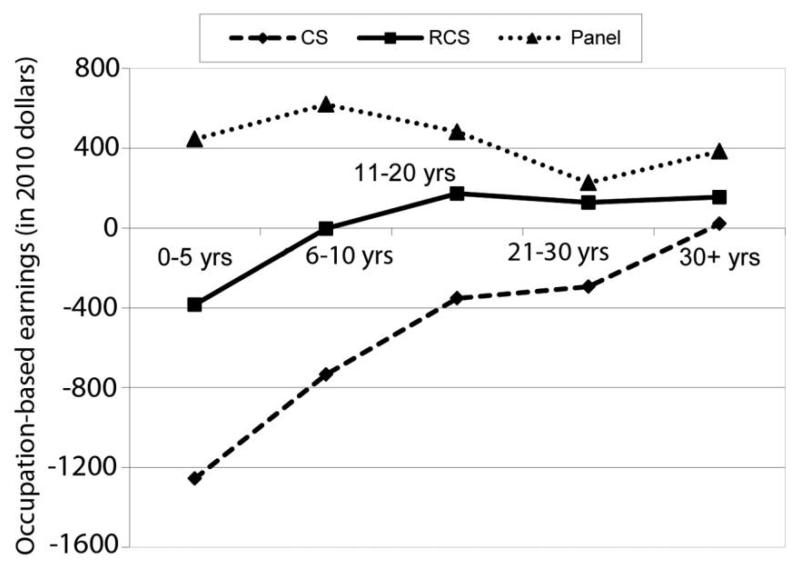

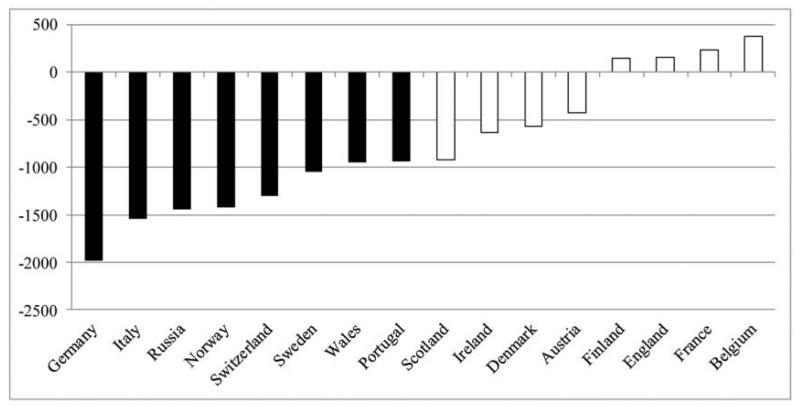

We have argued thus far that the typical long-term immigrant in the panel sample holds a slightly higher-paid occupation than the average native, even upon first arrival. However, this pattern masks substantial heterogeneity across sending countries. Figure 3 illustrates cross-country variation in the occupation-based earnings of immigrants relative to the native-born, both upon first arrival and after 30 or more years in the United States. The black bars indicate that immigrants from six of the 16 sending countries held occupations that paid significantly less than the native-born upon first arrival, immigrants from five countries held occupations that paid significantly more, and immigrants from the five remaining countries exhibited little difference in earnings power relative to natives upon first arrival.

Fig. 3.

—Earnings gap between the native- and foreign-born in the panel sample: natives versus immigrants upon first arrival (0–5 years in the United States) and after time in the United States (30+ years in the United States), by country of origin. The graph reports co-efficients on the interaction between country-of-origin fixed effects and dummy variables for being in the United States for 0–5 years or for 30+ years from regression of equation (1) in the panel sample. All coefficients for the 0–5 year interaction are significant except those for Austria, Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Sweden. None of the differences between the 0–5 year and 30+ year coefficients are significant except for those of Finland and Ireland.

We use data on real wages in the sending countries in 1880 from Williamson (1995) to subdivide the sample into richer (above-median real wages) and poorer (below-median) sending countries34. On average, long-term immigrants from poorer sending countries started out $1,700 behind natives, while immigrants from rich sending countries already held occupations that paid $800 more than those of natives upon arrival. Another potentially relevant division was between predominantly Catholic and predominantly Protestant countries. Long-term immigrants from the typical Catholic country started out $600 behind the native-born, while immigrants from Protestant countries arrived about even with natives35. Other factors that predict occupation-based earnings upon arrival are the linguistic and cultural distances between the source country and the United States36.

Comparing the black to the white bars in figure 3 demonstrates that, on the whole, permanent immigrants experience little occupational growth relative to natives after spending time in the United States. Migrants from 10 countries experience a small amount of convergence relative to natives over this period, while migrants from six countries either diverge from or experience a small reversal relative to natives. Migrants from the typical poorer country, with the exception of Finland, experienced $750 of convergence with the native-born over 30 years, closing 40 percent of their initial gap, while those from the typical rich country widened their lead over natives by nearly $30037.

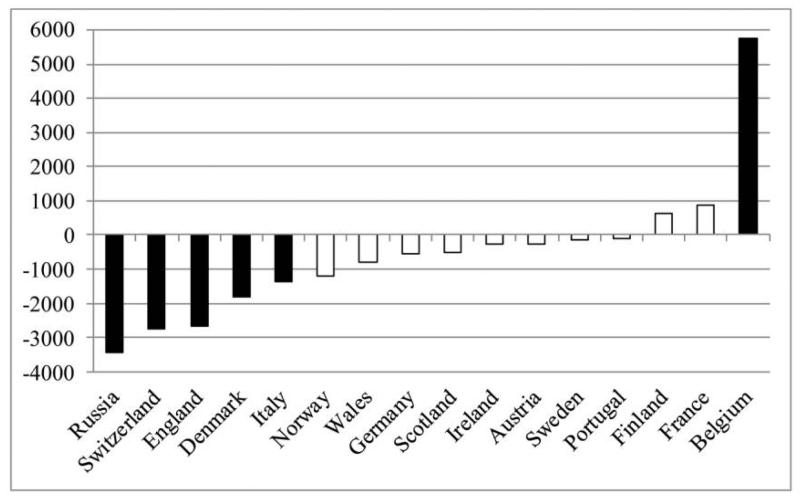

Countries also differ in the degree of change in the skills of their arrival cohorts over time and in the selectivity of their return migration. We start by examining heterogeneity in arrival cohort skill level. Figure 4 reports differences by country between immigrants who arrived between 1880 and 1884 and those who arrived between 1895 and 1900. Countries such as Russia and Italy, whose immigration waves began in large numbers only in the early 1880s, are among those with the largest decline in arrival cohort skill level over this period, perhaps because positively selected “pioneer” migrants are replaced by the more typical migrant over time. Old immigrant groups such as the English and the Irish experience smaller declines in arrival cohort skill level (or no decline at all) during this time.

Fig. 4.

—Changing quality of arrival cohorts, difference between immigrant penalty for early and late arrivals in the panel sample, by country of origin. Estimates are based on the version of equation (1) that contains country fixed effects and dummy variables for four arrival cohorts (see table 7, panel B). In addition, we interact the country fixed effects with the dummy variables for arrival cohort. The graph reports the difference between the dummy variable for arriving in the United States between 1880 and 1885 and the dummy variable for arriving in the United States between 1895 and 1900, separately by country. Differences that are significantly different from zero are in black. The sample includes observations in the panel sample.

Figure 5 explores heterogeneity in the implied selection of return migrants by sending country. In particular, we report the difference between the coefficients on the 0–5 years in the United States indicators in the cross section versus the panel sample by sending country; recall that a negative value indicates that return migrants are negatively selected. We normalize the differences for the 0–5 year indicators by the difference between the cross section and the panel for the 21–30 years in the United States indicators to account for potential biases in match quality38. The figure reveals statistically significant negative selection in the return migration flow back to five sending countries (Denmark, England, Italy, Russia, and Switzerland) and sizable positive but statistically insignificant selection to one country (Belgium). The return migrant flow to the remaining 10 countries is neutral39. The declining cohort quality among Italian immigrants, coupled with a negatively selected set of temporary migrants from Italy, may explain why the perception of Italian immigrants to the United States was so poor by the 1910s despite the fact that, as we estimate in figure 3, long-standing Italian immigrants who arrived before 1900 held occupations quite similar to those of natives.

Fig. 5.

—Implied selection of return migrants, difference between estimated convergence in panel and repeated cross-section data, by country of origin. The figure reports the difference between immigrants’ occupational upgrading relative to natives (defined as the difference between occupation-based earnings after 21–30 years and after 0–5 years) in the panel sample versus the cross section, by sending country. Results are from a regression of equation (1) that pools the panel and cross-section samples. Coefficients that are significantly different from zero are in black.

Russia is another particularly interesting case. Figure 3 shows that Russian migrants performed well in the United States upon first arrival, and figure 5 suggests that return migrants to Russia were particularly negatively selected. These patterns can be explained by the ethnic composition of the Russian migration. The Russian migrant flow is made up of two groups, Jews and non-Jews, who were primarily Poles and other nonethnic Russians. The Jewish immigrants were both higher skilled and less likely to return to Russia than their non-Jewish counterparts (Perlman 1999). In fact, only 7.1 percent of Russian Jews returned to Europe compared with 87 percent of Russian non-Jews (Gould 1980). Therefore, the return migrant flow is made up primarily of low-skilled, non-Jewish Russians.

VII. Alternative Specifications

A. Modifications to the Main Specification

Table 7 assesses the sensitivity of our main findings to a series of alternative specifications. In each case, we continue to find (1) limited convergence between immigrants and natives in the panel sample ($300 or less after 30 years in the United States) and (2) higher occupation-based earnings for long-term migrants in the panel than for the weighted average of long-term and temporary migrants in the cross sections.

TABLE 7.

Robustness for Age-Earnings Profile in Panel Sample, 1900–1920

| Cross Section (1) |

Repeated Cross Section (2) |

Panel (3) |

Cross Section (4) |

Repeated Cross Section (5) |

Panel (6) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Without Country Fixed Effects |

B. Four Arrival Cohorts |

|||||

| 0–5 years in US | −888.67 (115.93) |

−216.01 (169.86) |

558.44 (226.70) |

−1,255.73 (143.44) |

−56.53 (219.51) |

579.92 (275.95) |

| 6–10 years in US | −239.95 (108.00) |

290.97 (144.83) |

717.56 (193.05) |

−734.51 (147.44) |

11.56 (196.99) |

391.35 (239.13) |

| 11–20 years in US | 164.98 (74.66) |

507.08 (92.39) |

557.89 (115.39) |

−352.93 (131.27) |

250.91 (155.94) |

364.76 (173.98) |

| 21–30 years in US | 177.53 (92.56) |

424.65 (100.28) |

283.32 (113.96) |

−294.87 (142.10) |

176.77 (157.54) |

93.22 (170.67) |

| 30+ years in US | 373.49 (142.90) |

339.10 (148.39) |

430.04 (155.31) |

22.41 (184.65) |

211.37 (187.14) |

260.04 (196.94) |

| Arrive 1891+ | … | −660.11 (107.32) |

−137.18 (163.46) |

… | … | … |

| Native-born | … | … | −154.12 (176.14) |

… | … | −154.09 (176.14) |

|

|

||||||

| C. In(Occupation Score) |

D. Drop Child Migrants |

|||||

| 0–5 years in US | .006 (.008) |

.047 (.010) |

.084 (.012) |

−1,288.05 (144.40) |

−522.29 (192.51) |

115.65 (245.32) |

| 6–10 years in US | .028 (.007) |

.063 (.008) |

.083 (.010) |

−842.87 (149.46) |

−201.99 (178.79) |

170.87 (222.92) |

| 11–20 years in US | .041 (.006) |

.065 (.006) |

.070 (.007) |

−535.17 (135.42) |

−30.39 (146.12) |

42.86 (167.39) |

| 21–30 years in US | .034 (.006) |

.053 (.006) |

.059 (.006) |

−328.99 (147.93) |

88.91 (151.20) |

−174.59 (169.82) |

| 30+ years in US | .041 (.008) |

.046 (.008) |

.061 (.008) |

71.42 (206.36) |

188.59 (203.89) |

183.61 (221.55) |

| Arrive 1891+ | −.034 (.004) |

−.009 (.007) |

−671.59 (114.15) |

−84.89 (172.86) |

||

| Native-born | −.005 (.008) |

−153.59 (176.14) |

||||

Note.—All regressions follow the specification in table 4 with the exception of the modification listed in panel titles. In panel B, the four arrival cohorts are 1880–85, 1886–90, 1891–95, and 1896–1900. Panel D drops immigrants who arrived in the United States before age 10 or after age 40. Standard errors are in parentheses. Sample size for panels A–C is 259,093; panel D has 243,671 observations.

Thus far, we have emphasized the changes in cohort quality that occur within a sending country as the immigrant flow increases over time. More broadly, the set of sending countries contributing to US immigration may have shifted over this period, leading the skill level of entrants to decline with arrival year. We assess this possibility in panel A, which omits country-of-origin fixed effects from the regression. This modification barely alters the comparison between the coefficients in the cross section and the repeated cross section, suggesting that declines in arrival cohort skill level occur primarily within sending countries, at least for immigrants arriving before 1900. In particular, compare a difference between single and repeated cross section coefficients for recent arrivals of $870 (table 4, with country fixed effects) and $670 here (without country fixed effects). Panel B includes indicators for a series of finer arrival cohorts (arrival 1886–90, 1891–95, and 1896–1900; arrival before 1885 is the omitted category). These controls completely eliminate the occupation-based earnings gap between immigrants and natives in the repeated cross section, implying that the $1,200 earnings penalty in the cross section is entirely due to changes in arrival cohort skill level.

Panel C replaces the dependent variable with the logarithm of our 1950 occupation-based earnings measure. In this case, immigrants in both the repeated cross section and the panel outearn natives upon first arrival, by 4.5 percent and 9.0 percent (= 8.5 + 0.5), respectively. Differences between the logarithm and levels specifications are driven by the concentration of natives at the top end of the occupation-based earnings distribution (see white-collar workers in fig. 1); these lucrative occupations are more heavily weighted in the levels specification.

Panel D excludes the 20 percent of the migrant sample who arrived in the United States as children before the age of 1040. Young immigrants may experience systematically different rates of assimilation as a result of heightened fluency in English or education in the US school system (Friedberg 1993; Bleakley and Chin 2010). We find that excluding child immigrants has little effect on the results.

B. Occupational Transition Matrices, 1900–1920

The main results demonstrate that long-term immigrants moved up the occupation ladder at the same rate as natives. Table 8 examines these occupational transitions directly, presenting transition matrices between 1900 and 1920 for natives and immigrants in the panel sample. As in figure 1, we use the HISCLASS classification collapsed into five categories to observe transitions between white-collar, skilled blue-collar, semiskilled blue-collar, farm, and unskilled work.

TABLE 8.

Occupational Mobility from 1900 to 1920, Immigrants and Natives in Panel

| 1920 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | White-Collar | Skilled Blue- Collar |

Farmer | Semiskilled | Unskilled | Row Total |

| A. Native-Born |

||||||

| White-collar | 66.71 (138) |

8.10 (17) |

6.67 (14) |

17.14 (36) |

2.38 (5) |

100 (210) |

| Skilled blue-collar | 19.44 (21) |

49.07 (53) |

10.19 (11) |

15.74 (17) |

5.56 (6) |

100 (108) |

| Farmer | 12.63 (24) |

4.12 (8) |

68.95 (131) |

4.74 (9) |

9.47 (18) |

100 (190) |

| Semiskilled | 25.74 (52) |

9.41 (19) |

9.41 (19) |

47.52 (96) |

7.92 (16) |

100 (202) |

| Unskilled | 17.77 (51) |

11.15 (32) |

33.80 (97) |

13.24 (38) |

24.04 (69) |

100 (287) |

| Column total | 28.69 (286) |

12.94 (129) |

27.28 (272) |

19.66 (196) |

11.43 (114) |

100 (997) |

|

|

||||||

| B. Immigrants |

||||||

| White-collar | 55.34 (1,045.44) |

12.49 (235.96) |

7.83 (148.00) |

14.50 (273.89) |

9.84 (185.84) |

100 (1,889.15) |

| Skilled blue-collar | 27.37 (611.59) |

35.84 (800.95) |

9.12 (203.86) |

16.81 (375.59) |

10.86 (242.57) |

100 (2,234.57) |

| Farmer | 12.81 (155.32) |

6.88 (83.45) |

63.20 (766.28) |

7.89 (95.61) |

9.23 (111.87) |

100 (1,212.55) |

| Semiskilled | 29.49 (1,048.43) |

13.16 (467.72) |

8.29 (294.08) |

34.41 (1,223.25) |

14.64 (520.45) |

100 (3,554.67) |

| Unskilled | 21.40 (791.17) |

12.30 (454.81) |

22.69 (838.81) |

20.16 (745.14) |

23.45 (867.13) |

100 (3,697.06) |

| Column total | 29.01 (3,651.95) |

16.23 (2,042.91) |

17.89 (2,251.76) |

21.56 (2,713.50) |

15.32 (1,927.88) |

100 (12,588) |

Note.—Occupations are classified according to the HISCLASS rubric. HISCLASS 1–5 = white-collar; HISCLASS 6–7 = skilled blue-collar; HISCLASS 8 = farmers; HISCLASS 9 = semiskilled; HISCLASS 10–12 = unskilled. Each cell reports the share of immigrants (natives) in a certain occupation class in 1900 (row) and in 1920 (column). In parentheses is the number of cases underlying each percentage. Because the immigrant figures are weighted to reflect population shares in 1920, the numbers of cases in panel B are non-integer.

The occupational transitions reveal a series of interesting patterns. First, we find that, even though immigrants and natives experience similar occupation-based earnings growth, immigrants are more likely than natives to move both up and down the occupational ladder over time. As seen in the diagonal entries, immigrants are less likely to remain in the same occupational category in 1920 that they inhabited in 1900. This pattern is true both at the top of the occupational distribution (white-collar positions) and at the lower end of the occupational scale (semi-skilled blue-collar).

Second, immigrants and natives use different rungs to move up the ladder. For example, 32 percent of immigrants who held unskilled jobs in 1900 ascend into skilled or semiskilled blue-collar work by 1920, compared with only 24 percent of similarly positioned natives. In contrast, 34 percent of formerly unskilled natives move into owner-occupier farming by 1920, compared with only 23 percent of unskilled immigrants; some of the transitions into farming for the native-born could be driven by inheriting a family farm.

As we saw in figure 1 above, natives were more likely to work in farming in 1900, while immigrants were more likely to hold skilled blue-collar positions. Over the next 20 years, natives and immigrants continue to follow these divergent strategies to get ahead. On average, though, these different paths lead to equal occupation-based earnings growth (especially if farming is treated as an occupation with below-median earnings, as in the 1950 earnings distribution).

VIII. Ruling Out Other Sources of Selective Attrition

Our empirical approach infers the direction of selection of return migrants relative to long-term migrants indirectly, by comparing occupational upgrading patterns in the repeated cross section versus the panel data. Yet, more generally, any differences between the repeated cross sections and the panel are due to selective attrition from the cross sections, which can be due to selective return migration but could also be due to selective mortality or selective name changes. We argue here that mortality and name changes are not likely to be driving the results.

Selective mortality is not a likely concern. Mortality in 1900 for this age group (ages 15–45) was fairly low and uniform across sending countries. Although the Irish were slightly more likely to die (eight per 1,000) and the Russians were slightly less likely to die (three per 1,000), mortality rates for members of other nationalities and for US natives were all around five to six per 1,000 (figures by Merriam [1903], based on the 1900 census). Furthermore, note that selective return migration is not an issue for the native-born because few US natives emigrated from the country. Therefore, one way to test for the presence of selective mortality is to compare the occupation-based earning patterns of native-born men in the repeated cross section versus the panel data. For natives, any difference between these samples can be due to selective mortality but not to out migration. We find that the occupation-based earnings of natives are similar in the repeated cross sections and the panel in all years, suggesting that selective mortality is a nonissue (at least for the native-born)41. We note that this test for selective mortality relies on the assumption that native and foreign-born men were subject to the same mortality process.

Likewise, we do not expect that selective name changes by immigrants will bias the data. First, most name changes occurred upon entry to the United States (e.g., at Ellis Island). Any such change would have taken place before we first observe migrants in the 1900 census and would thus affect neither data source. Second, men who changed their name between censuses are not likely to affect the results because name changers cannot be matched over time, so they are never included in the panel sample; name changing has nothing to do with enumeration in the census, and so name changers will always be present in the cross sections. That is, unlike men who die between census waves, name changers do not drop out of the cross-section data over time. Third, we find that, although immigrants in the panel sample have slightly more “foreign” names than their counterparts in the cross section, the small observed difference in the “foreignness” index is associated with only a $60 difference in occupation-based earnings (in 2010 dollars) and so is not quantitatively large enough to affect the results42.

IX. Second-Generation Migrants in the US Labor Market

Occupational convergence between immigrants and natives may take more than one generation. On the one hand, second-generation migrants may attain equal standing with natives because they were educated in the United States and, therefore, were likely fluent in English and may have been exposed to US norms and culture. On the other hand, occupational differences could persist over generations if, for example, second-generation migrants grew up in migrant enclaves or inherited occupational skills from their parents43.

We compare the occupation-based earnings of US-born men whose parents were born abroad to US-born men whose parents were born in the United States (hereafter referred to as US natives, even though second-generation immigrants are also born in the United States). In particular, we use our panel sample to compare first-generation immigrants to US natives and supplement this with the 1 percent IPUMS samples of the US census from 1920 to 1950, which we use to compare US natives to the cohort of children born to these first-generation immigrants44.

We estimate the following age-earnings profile separately for each group and for each country of origin:

| (2) |

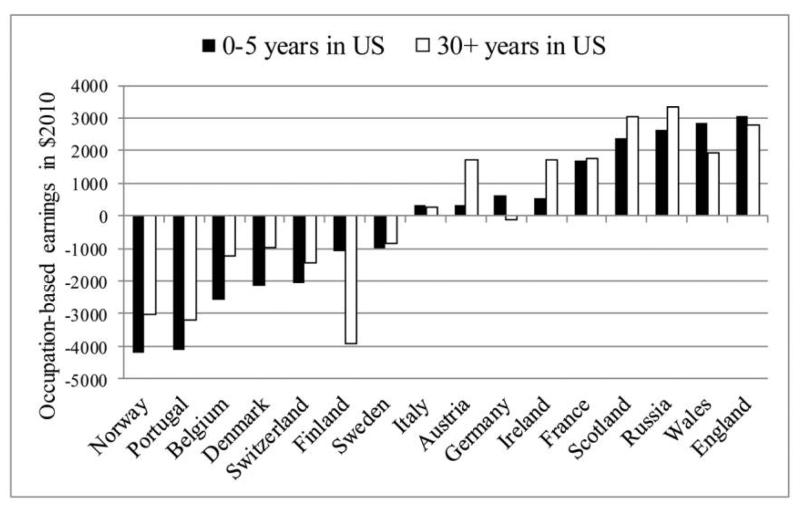

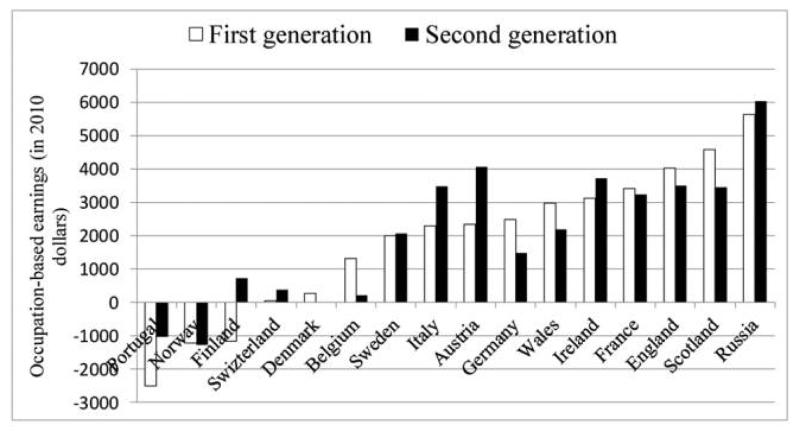

As before, our outcome variable is occupation-based earnings converted to 2010 dollars. In figure 6, we illustrate the results from equation (2) for a person who is 35 years old in either 1910 (first generation vs. natives) or 1930 (second generation vs. natives). We assume that the first-generation migrant moved to the United States in 1890.

Fig. 6.

—Convergence in occupation-based earnings across immigrant generations: first-generation and second-generation migrants versus natives, by country of origin. We estimate the regression in equation (2) separately for each group and for each country: immigrants (first generation), US natives in the same censuses and ages as the immigrants, sons of immigrants (second generation), and US natives in the same censuses and ages as the second-generation sample. The bars for the first generation represent the difference in the predicted occupation-based earnings of an immigrant who came in 1890 and is 35 years old in 1910 relative to a 35-year-old native. The bars for the second generation represent the difference in the predicted occupation-based earnings of a man born in the United States to immigrant parents relative to a man born in the United States to native parents, both of whom were 35 years old in 1930. First-generation immigrants are taken from the panel sample. Natives and second-generation immigrants come from IPUMS data in the respective census year.

Figure 6 suggests strong evidence of persistence across generations. If the first-generation immigrants outperformed natives (e.g., Russia, Scotland, England), so did the second generation and vice versa (e.g., Norway, Portugal)45. A notable exception is Finland, in which first-generation migrants held lower-paid occupations but second-generation migrants held higher-paid occupations.

X. Conclusion

We construct a new panel data set of native- and foreign-born men in the US labor market at the turn of the twentieth century, an era in which US borders were open to all European migrants. This Age of Mass Migration not only is of interest in itself, as one of the largest migration waves in modern history, but also is informative about the process of immigrant assimilation in a world without migration restrictions. Most of the previous research on this era relies on a single cross section of data and finds that immigrants started with lower-paid occupations than natives but caught up with natives after spending some time in the United States.

In our panel data set, we instead find that the average immigrant who settled in the United States long-term did not hold lower-paid occupations than US natives, even upon first arrival, and moved up the occupational ladder at the same rate as natives. We conclude that the apparent convergence in a single cross section reflects a substantial decline in the quality of migrant cohorts over this period as well as a change in the composition of the migrant pool as negatively selected return migrants left the United States over time. Our paper further demonstrates the importance of accounting for differences in migration patterns across sending countries. Long-term migrants from highly developed sending countries performed better than natives upon first arrival, while long-term migrants from poorer sending countries performed worse. Yet immigrants from all countries, regardless of their starting position, experienced little occupational convergence with natives.

Contemporaries questioned the ability of European immigrants to assimilate in the US economy and called for strict migration restrictions. Our results indicate that these concerns were unfounded: the average long-term immigrants in this era arrived with skills similar to those of natives and experienced identical rates of occupational upgrading over their life cycle. These successful outcomes suggest that migration restrictions are not necessary to ensure migrant assimilation. Yet at the same time, we also note that migrants who arrived with low skill levels did not manage to close their skill gap with natives over time. This finding undercuts the view, which is commonly held today, that past waves of European immigrants, even those who arrived with limited skills and without the ability to speak English, were able to quickly catch up with natives.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for access to census manuscripts provided by Ancestry.com and Family Search.org. We benefited from the helpful comments of participants at the University of California, Davis, Interdisciplinary Conference on Social Mobility, the Agence Française de Développement-World Bank Migration and Development Conference, the Labor Markets, Families and Children Conference at the University of Stavanger, the Economic History Association, and the National Bureau of Economic Research Development of the American Economy Summer Institute. We also thank participants of seminars at Berkeley, Caltech, Chicago, Duke, Hebrew University, Northwestern, Norwegian School of Economics, Stanford, Tel Aviv, University of Caifornia at Davis and Los Angeles, and University of Texas at Austin. We learned from conversations with Manuel Amador, Attila Ambrus, Pat Bayer, Doug Bernheim, Tim Bresnahan, Marianne Bertrand, David Card, Greg Clark, Dora Costa, Pascaline Dupas, Liran Einav, Joseph Ferrie, Erica Field, Doireann Fitzgerald, Bob Gordon, Avner Greif, Hilary Hoynes, Nir Jaimovich, Lawrence Katz, Pete Klenow, Pablo Kurlat, Aprajit Mahajan, Robert Margo, Daniel McGarry, Roy Mill, Joel Mokyr, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Seth Sanders, Izi Sin, Yannay Spitzer, Gui Woolston, Gavin Wright, and members of the UCLA KALER group. Roy Mill provided able assistance with data collection. We acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation (grant SES-0720901), the California Center for Population Research, and UCLA’s Center for Economic History. Data are provided as supplementary material online.

Appendix A

Data

This appendix describes the procedure by which we match men from the 1900 census to the 1910 and 1920 censuses. We begin by identifying a sample of men in the base year from two census sources. For large sending countries (listed in table 1, panel A), we rely on the 1900 5 percent Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS; Ruggles et al. 2010) to find immigrants from large sending countries and to randomly select a sample of 10,000 native-born men. To ensure a sufficient sample size for smaller sending countries (table 1, panel B), we instead compile the full population in the relevant age range in 1900 from the genealogy website Ancestry.com. Altogether, we identify immigrants from 16 sending countries46.

We search for viable matches for these men in 1910 and 1920 using the iterative matching strategy developed by Ferrie (1996) and employed more recently by Abramitzky et al. (2012) and Ferrie and Long (2013). More formally, our matching procedure proceeds as follows:

We begin by standardizing the first and last names of men in our 1900 samples to address orthographic differences between phonetically equivalent names using the NYSIIS algorithm (see Atack and Bateman 1992). We restrict our attention to men in 1900 who are unique by first and last name, birth year, and place of birth (either state or country) in the 1900 census. We do so because, for nonunique cases, it is impossible to determine which of the records should be linked to potential matches in 1910 and 1920. Table 1 presents information about the number of potential matches by country.

-

We identify potential matches in 1910 and 1920 by searching for all men in our 1900 sample in the 1910 and 1920 census manuscripts available from Ancestry.com. The Ancestry.com search algorithm is expansive and returns many potential matches for each case, which we cull using the iterative match procedure described in the next step47.

TABLE A1.

Comparing Matched Panel Sample with Population, 1920 Occupation-Based Earnings in 2010 DollarsDifference, Panel

Sample – Population

Mean,

Panel Sample

(1)Levels

(2)Logs

(3)Native-born $23,185 37.64

(316.41).009

(.013)Foreign-born $23,405 303.63

(131.81).019

(.006)Note.—Occupation-based earnings is based on 1950 medians, converted into 2010 dollars. Regressions in cols. 2 and 3 pool the 1920 IPUMS cross section with our matched sample and regress occupation-based earnings on a dummy variable for being in the matched sample. Standard errors are in parentheses. We match observations forward from 1900 to either the full population (for small countries) or the set of potential matches (for large countries) in 1910 and 1920 using an iterative procedure. We start by looking for a match by first name, last name, place of birth (either state or country), and exact birth year. There are three possibilities: (a) if we find a unique match, we stop and consider the observation “matched”; (b) if we find multiple matches for the same birth year, the observation is thrown out; (c) if we do not find a match at this first step, we try matching within a 1-year band (older and younger) and then with a 2-year band around the reported birth year; we accept only unique matches. If none of these attempts produces a match, the observation is discarded as unmatched.

After matching each sample in 1900 separately to 1910 and 1920, we create our final data set by restricting to men who were located in both 1910 and 1920.

Our matched sample may not be fully representative of the immigrant and native-born populations from which they are drawn. In particular, men with uncommon names are more likely to be successfully linked between censuses, and the commonness of one’s name could potentially be correlated with socioeconomic status. We assess this possibility by comparing men in the cross-sectional and panel samples in 1920. By definition, men in both the panel and repeated cross sections must have survived and remained in the United States until 1920. Thus, by 1920, up to sampling error, differences between the panel and the repeated cross sections must be due to an imperfect matching procedure.

Table A1 compares the mean occupation score of men in our cross-section and panel samples in 1920. We consider natives and the foreign-born separately and reweight the matched sample to reflect the distribution of country of origins in the 1920 population. Immigrants in the matched sample slightly outearn their native counterparts by 1920 ($23,400 vs. $23,200). Among natives, the difference in the mean occupation score in the matched sample and the population in 1920 is small ($37) and statistically indistinguishable from zero. In contrast, immigrants in the matched sample have a $300 advantage over immigrants in the representative sample48. Therefore, up to $300 of earnings differential between immigrants and natives in the panel data can be due to sample selection induced by our matching procedure.

Footnotes