Abstract

Stringent negative regulation of the transcription factor NF-κB is essential for maintaining cellular stress responses and homeostasis. However, the tight regulation mechanisms of IKKβ are still not clear. Here, we reported that nemo-like kinase (NLK) is a suppressor of tumor necrosis factor (TNFα)-induced NF-κB signaling by inhibiting the phosphorylation of IKKβ. Overexpression of NLK largely blocked TNFα-induced NF-κB activation, p65 nuclear localization and IκBα degradation; whereas genetic inactivation of NLK showed opposing results. Mechanistically, we identified that NLK interacted with IκB kinase (IKK)-associated complex, which in turn inhibited the assembly of the TAK1/IKKβ and thereby, diminished the IκB kinase phosphorylation. Our results indicate that NLK functions as a pivotal negative regulator in TNFα-induced activation of NF-κB via disrupting the interaction of TAK1 with IKKβ.

Keywords: NLK, NF-κB, TNFα, IKKβ, TAK1

1. Introduction

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) is a family of transcription factor complexes that regulate cell survival and proliferation. Dysregulation of NF-κB leads to chronic inflammatory diseases and development of cancer [1,2]. In the resting cells, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by binding to members of the IκB family of inhibitor proteins, which mask its nuclear localization signal (NLS) [3,4]. NF-κB consisting of p50 and p65 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by binding to IκB, an inhibitor of the nuclear localization signal. Upon various cytokine stimulations, the phosphorylated IκB protein is degraded by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway [5,6]. Degradation of IκB results in release and nuclear translocation of NF-κB, thereby activating the NF-κB target gene transcription [7–9].

TNFα is one of the major cytokines that activates the NF-κB signaling pathway. Binding of TNFα to its receptor leads to assembly of the NF-κB initial complex, which comprises TRADD, TRAF2/5 and RIP1 [10–12]. Notably, TRAF2 results in K63-linked polyubiquitination of RIP1, which then recruits TAK1 and TAB2 to phosphorylate the IκB kinase [13]. The activated IκB kinase subsequently phosphorylates IκB and promotes IκB degradation, thereby activating NF-κB [14].

The IκB kinase complex consists of two catalytic subunits IKKα/IKKβ and a regulatory subunit NEMO [15]. It is believed to play a central role in the regulation of NF-κB signaling [16,17]. IKKα/IKKβ double knockout fibroblasts fail to respond to various NF-κB activators [18]. Activation of the IκB kinase complex is strictly controlled by the TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), which phosphorylates IKKβ at the two serine residues within its activation loop [19,20]. However, how the IKKβ activity is negatively regulated under the basal conditions remains unclear.

Nemo-like kinase (NLK), a member of the MAPK family, suppresses a wide range of transcription factors including NF-κB [21]. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism by which NLK suppresses NF-κB transcriptional activity remains elusive. Here, we report that NLK competes with TAK1 to bind with IKKβ, leading to inhibition of the IKKβ phosphorylation and activation of the NF-κB signaling.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and Constructs

Recombinant TNFα (R&D systems), NLK (Bethyl), Flag, HA, Myc, GAPDH (CWBIO), IκBα, IKKα, IKKβ, p-IKKα/β, TAK1, p-TAK1, p65 (Cell Signaling), and H3 (Epitomics) were purchased from the indicated companies. The encoding 192 kinase clones were obtained from Addgene. NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid and TAK1, TAB1, IKKα/β, and TRAF2 mammalian expression plasmids were gifts from Hongbing Shu. TNF-R1, p65, NLK and its mutants were constructed by molecular cloning process.

2.2. Transfection and reporter assays

HEK293 cells (1 × 105) were seeded in 24-well plates and transfected using TurboFect (Thermo). The indicated reporter plasmid and pRL-TK were added to each transfection. After 24 h later, the dual-specific luciferase assay kit (Promega) was used for the reporter assays.

2.3. Coimmunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis

The HEK293 cells (1 × 106) were transfected and harvested in 400 µl NP40 lysis buffer (30 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40) with proteinase cocktail inhibitors (Roche). The supernatant was incubated with the indicated antibodies and Protein G beads (Roche) at 4 °C for 5 h. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and fractionated by SDS/PAGE, which was then analyzed by western blotting.

2.4. RNA sequencing and data analysis

Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed. Then, the cDNA was analyzed by Sinogenomax Co. The raw reads containing low-quality data were cleaned by removing those contain either a base of N or over half qualities below 20. Then, the resulting clean reads were mapped to the human mRNA sequences with TopHat software. The RPKM value, which is the normalized number of reads of each mRNA, was calculated and used as the expression level. Genes expressed differently between every two samples were analyzed by the DESeq R package using a cutoff of P, 0.01.

2.5. RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Cells were lysed in TRIZOL (TAKARA), and RNA was isolated according to standard protocol. Then, total RNA was used for reverse transcription according to the manufacturer's manual (Fermentas). The amount of mRNA was assayed by quantitative PCR. GAPDH: 5′-GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT (forward) and 5′-GACAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAG (reverse), B94: 5′-TCTCACTGTTGACCCT TTGGC (forward) and TGACCCG CAGAACTGGAAG (reverse), cIAP2: 5′-TCAA GTTCAAGCCAGTTACC (forward) and 5′-GACTCTGCATTTTCATCTCC (reverse), IL-6: 5′-TTCTCCACAAGCGCCTTCGGTC (forward) and 5′-TCTG TGTGGGGCGGCTACATCT (reverse), ICAM1: 5′-TCAGTGTGACCGCAGAG GACGA (forward) and 5′-TTGGGCGCCGGAAAGCTGTAGAT (reverse), TNFα: 5′-GCCGCATCGCCGTCTCCTAC (forward) and 5′-CCTCAGCCCCCTCTGG GGTC (reverse), IκBα: 5′-CGGGCTGAAGAAGGAGCGGC (forward) and 5′-ACGAGTCCCCGTCCTCGGTG (reverse), NFκB1: 5′-TGGTATCAGACGCCAT CTA (forward) and 5′-GCTGTCCTGTCCATTCTTAC (reverse), SOD2: 5′-GCACGCTTACTACCTTCAGT (forward) and 5′-CTCCCAGTTGATTACATTCC (reverse).

2.6. Cell fractionation

The cells were fractionated with NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Thermo) following instructions of the manufacturer.

2.7. Fluorescent confocal microscopy

The HeLa cells and HCT116 cells were cultured on coverslips and transfected with cherry-NLK by TurboFect (Thermo). About 24 h later, the cells were treated with or without TNFα for 30 min and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Then, the fixed cells were incubated with the indicated antibody and observed using a confocal microscope under a × 100 oil objective.

2.8. Genetic knockout in human somatic cells

The genetic inactivation of NLK in human colorectal cancer cells HCT116 was performed following a previously described method [22, 23]. Shortly, HEK293 cells were transfected with a target vector containing two homologous arms and two packaging vectors, AAV-Helper and AAV-RC. After 3 days, the cells were collected with a scratcher and subjected to freeze–thaw in liquid nitrogen three times, then the supernatant was harvested as the rAAV stock. A total of 1 × 105 HCT116 cells were infected with rAAV virus about 2 days and were split into 6 96-well plates in order to obtain as many single clones as possible. After 2 weeks of selection in 0.5 mg/ml G418, the single clones were screened by PCR, and positive clones were amplified. Then, the clones were passaged into one well of a 24-well plate, and GFP-Cre Adenovirus was added into the well to cut the resistant gene. One allele disrupt clone were screened by PCR using proper primers. The second allele was then disrupted using the same method.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of NLK as a negative regulator of TNFα-induced NF-κB signaling

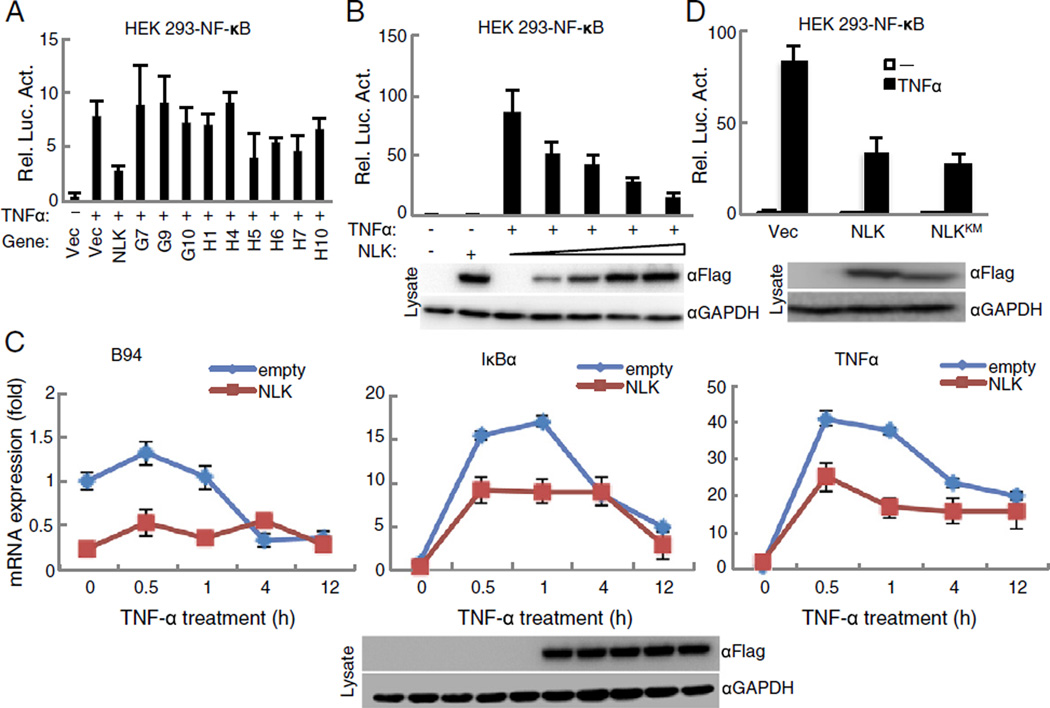

To identify potential kinases that negatively regulate NF-κB transcriptional activity, we screened approximately 200 kinase expression clones in HEK293 cells, using a NF-κB reporter assay. As shown in Fig. 1A, NLK strongly down-regulated the luciferase activity of the NF-κB reporter. Moreover, overexpression of NLK inhibited the TNFα-triggered activation of NF-κB in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). In addition, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses indicated that NLK suppressed the transcription of TNFα-induced genes including TNFα, IκBα and B94 at various time points (Fig. 1C). It is important to note here that Yasuda et al. previously showed that the inhibition of NF-κB activity by NLK was kinase-activity dependent, but their analysis was performed in the rest of the cells without TNFα stimulation [24]. Nonetheless, to address whether the kinase activity of NLK was required for suppression of the NF-κB activity with TNFα stimulation in this regard, we further expressed a NLK kinase-dead mutant (NLKK167M) [25] in the reporter system. Unexpectedly, it appeared that suppression of NF-κB activation by NLK is independent of its kinase activity, as the kinase-dead mutant NLKK167M still inhibited the NF-κB reporter activity in either HEK293 or HeLa cells (Figs. 1D and S1).

Fig. 1.

NLK suppresses TNFα-induced NF-κB activation and the transcription levels of downstream genes independent of kinase activation. (A) NLK was identified as a candidate repressor of TNFα-induced NF-κB activation. Partial human kinase clones (Addgene) (100 ng/ml) were co-transfected into HEK293 cells with a NF-κB reporter (50 ng). 24 h later, TNFα (20 ng/ml) was added to the cells for 12 h and then analyzed by the luciferase reporter assay. The numbers G7, G9, G10, H1, H4, H5, H6, H7, and H10 represent the genes PIP5K3, NEK3, GRK6, PACSIN1, STK33, SYK, ADRBK1, RPS6KL1, and PDXK, respectively. (B) Gradually increased NLK expression inhibits TNFα-triggered NF-κB signaling. The NF-κB reporter and different doses of the Flag-NLK plasmid were co-transfected into HEK293 cells. 24 h later, TNFα (20 ng/ml) was added to the cells for 12 h and assayed by a luciferase kit. (C) NLK inhibits TNFα-induced NF-κB downstream gene transcription of TNFα, B94 and IκBα. HEK293 cells were transfected with the F-NLK plasmid (200 ng). 24 h later, TNFα (20 ng/ml) was added to the cells at indicated times before real-time PCR experiment. (D) The kinase inactivation mutant of NLK (K167M) could not rescue the inhibition of NLK to NF-κB activation. NF-κB reporter, Flag-NLK and Flag-NLK (K167M) were co-transfected into HEK293 cells. 24 h later, the cells were exposed to TNFα (20 ng/ml) for 12 h prior to the luciferase assay.

3.2. Genetic inactivation of NLK leads to increased expression of NF-κB target genes

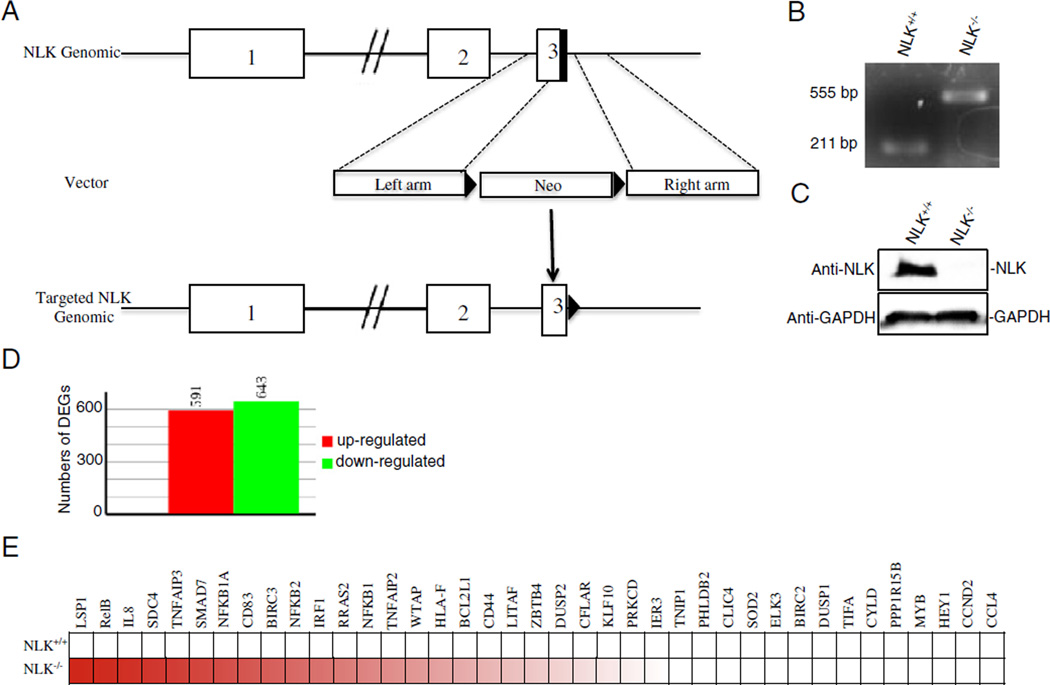

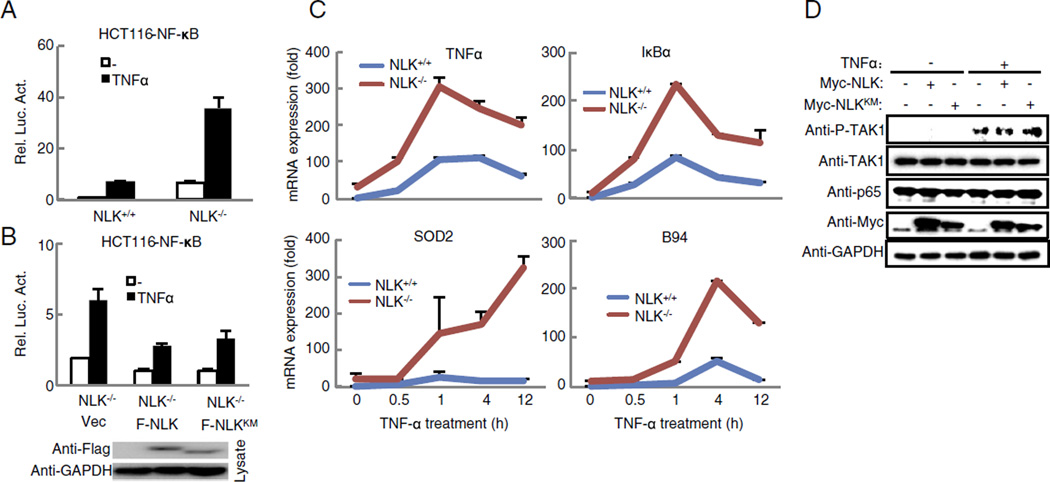

To facilitate dissection of the mechanisms by which NLK suppresses NF-κB activity, we set out to knockout NLK in HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. We chose HCT116 cells for two reasons: firstly, TNFα can activate the NF-κB signaling pathway in HCT116 cells; and secondly, HCT116 cells are widely employed for gene-targeting using rAAV-mediated homologous recombination [22,26]. In this study, both alleles of exon 3 of the NLK gene were targeted by two rounds of rAAV-mediated homolog recombination (Fig. 2A). The targeted clone was validated by both genomic PCR and Western blot analyses (Fig. 2B and C). The different gene expression was presented between the NLK−/− HCT116 cells and the wild-type cells in Fig. 2D via the RNA-seq analysis. As expected, the RNA-seq profiling analysis showed that expression levels of a set of NF-κB downstream genes, including RelB, IL8, SDC4, TNFAIP3 and NFKB1A,were elevated in the NLK−/− cells in comparison to the parental HCT116 cells (Fig. 2E). Luciferase reporter assay showed that the activity of NF-κB was higher in the NLK−/− cells in comparison to the parental HCT116 cells regardless of the TNFα stimulation (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the notion that NLK negatively regulates NF-κB signaling in a kinase-independent manner, overexpression of wild-type NLK and the NLKK167M mutant both suppressed the NF-κB reporter activity and TNFα-induced NF-κB target gene expression (i.e. TNFα, IκBα, SOD2, and B94) in the NLK−/− cells (Figs. 3B–C and S2). Taken together, these data demonstrate that NLK negatively regulates TNFα-induced NF-κB signaling cascades.

Fig. 2.

Genetic inactivation of NLK inHCT116 cells modifies NF-κB target genes. (A) Targeting of the NLK genomic locus and strategy. Two homologous arms (0.91 and 0.94 kb, respectively) were constructed in an AAV vector that incorporated the neomycin-resistance gene (Neo). The homologous recombination resulted in the deletion of exon 3 of NLK. (B) NLK-deficient cells were identified by genomic PCR. The lower band represents normal genotypes and the upper band represents the disrupted NLK genome. (C) The expression of NLK in the wild-type and NLK-deficient HCT116 cells. Cell lysates from different cells were analyzed by immunoblot using an anti-NLK antibody. (D) RNA sequencing assayed different genes between the NLK−/− HCT116 cells and the wild-type cells. RNA was extracted from NLK+/+ and NLK−/− cells and subjected to RNA sequencing. (E) RNA sequencing identified a number of upregulated NF-κB downstream genes in NLK−/− HCT116 cells. RNA was extracted from NLK+/+ and NLK−/− cells and subjected to RNA sequencing.

Fig. 3.

Deficiency of NLK increases TNFα-induced NF-κB activation and target gene transcription in HCT116 cells. (A) Deficiency of NLK potentiated TNFα-induced NF-κB activation. NLK+/+ and NLK−/− HCT116 cells were transfected with NF-κB reporter plasmid (50 ng). 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated with or without TNFα (20 ng/ml) for 12 h. Then luciferase experiments were performed. (B) NLK expression in NLK knockout HCT116 cells rescued NLK deficiency-caused phenotypes. NLK−/− HCT116 cells were transfected with NF-κB reporter plasmid and vector, Flag-NLK or F-NLKKM. 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated with or without TNFα (20 ng/ml) for 12 h. Then luciferase experiments were performed. (C) Deficiency of NLK potentiates TNFα-induced transcription of endogenous TNFα, B94, IκBα and SOD2 genes in HCT116 cells. NLK+/+ and NLK−/− cells were treated with or without TNFα (20 ng/ml) at the indicated times before real-time PCR experiments. (D) The expression of p65 and phosphorylation of TAK1 in HEK293 cells. Cell lysates from different cells were analyzed after TNFα treatment by immunoblot using indicated antibody. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

3.3. NLK regulates p65/RelA nuclear localization and IκBα degradation

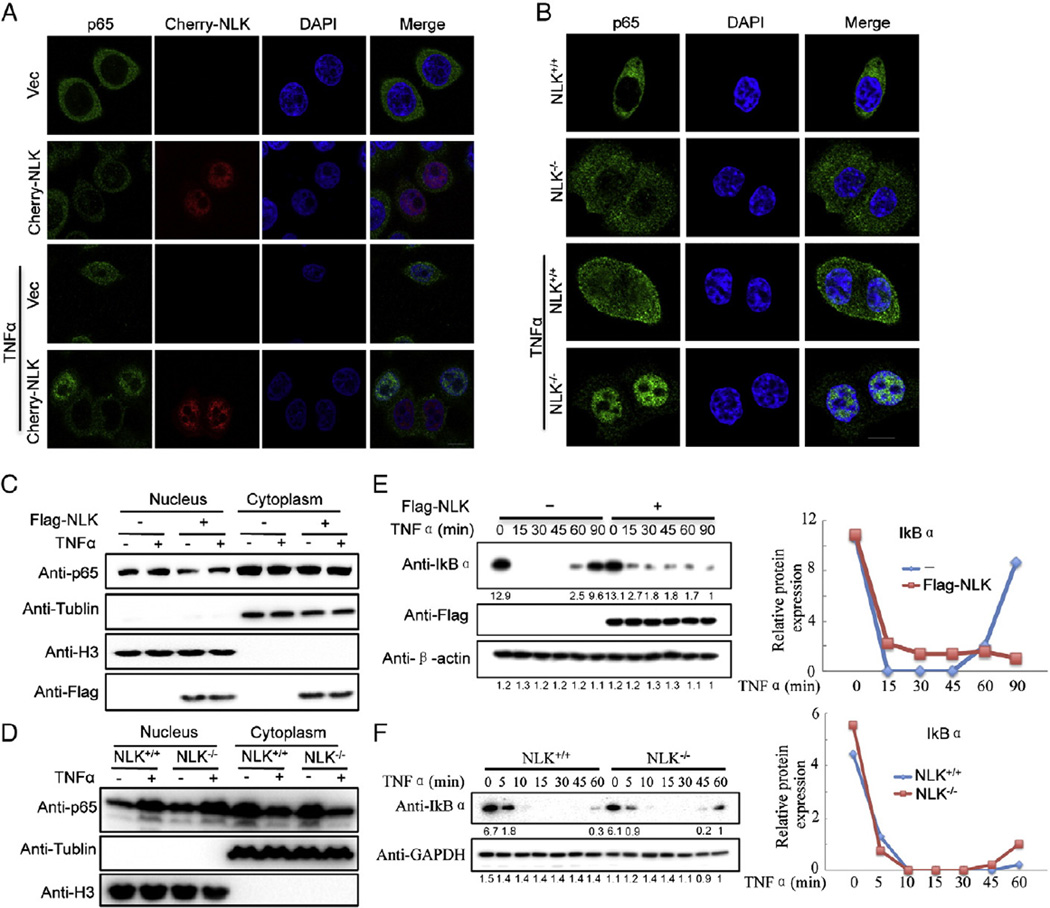

It is well recognized that the nuclear translocation of p65 is a key step to NF-κB activation. Having demonstrated that NLK negatively regulates NF-κB target gene expression, we have determined changes of the protein level in NF-κB pathway and phosphorylation of TAK1 in the presence of NLK or NLKKM after TNFα stimulation. As shown in Fig. 3D, the protein level of p65 and phosphorylation of TAK1 have not changed. Therefore we set out to determine whether NLK regulates NF-κB nuclear translocation. To this end, we examined the p65/RelA cellular localization upon TNFα treatment. The immunofluorescent staining analysis displayed that transfection of NLK significantly inhibited p65 nuclear localization in TNFα-treated cells (Fig. 4A). Similarly, TNFα facilitated p65 translocation into the nucleus in NLK−/− HCT116 cells (Fig. 4B). In parallel, we performed Western-blotting analyses to determine the contents of p65 included in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts which were collected from NLK-overexpressing 293 cells and NLK−/− HCT116 cells with or without TNFα treatment. Consistently, similar results were observed in these cells upon the indicated treatment (Fig. 4C and D). Taken together, these data indicate that NLK is involved in the TNFα-caused p65 subcellular translocalization.

Fig. 4.

NLK affects p65 translocation to the nucleus and IκBα degradation following TNFα treatment. (A) and (C) The higher expression of NLK inhibited p65 translocation to the nucleus upon the TNFα treatment. (A) The cherry-NLK was transfected into HeLa cells. After 24 h, the cells were treated with or without TNFα (20 ng/ml) for 30 min before the cells were fixed. Then, immunofluorescent staining was carried out using a p65 antibody and DAPI. (C) HEK293 cells were fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Nuclear immunoblot was performed and detected using the p65 antibody. H3 was used as the nuclear loading control. (B) and (D) Deficiency of NLK potentiates p65 translocation to the nucleus following the TNFα treatment. (B) NLK−/− HCT116 cells were treated with or without TNFα (20 ng/ml) for 15 min before the cells were fixed. Then, immunofluorescent staining was carried out using the p65 antibody and DAPI. (D) NLK−/− HCT116 cells were fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Nuclear immunoblotting was performed and detected using the p65 antibody. H3 was used as the nuclear loading control. (E) and (F) The NLK affects IκBα degradation following the TNFα treatment. HEK293 and NLK−/− HCT116 cells transfected with Flag-NLK were treated with or without TNFα at indicated times. Then the cells were lysed and subjected to immunoblotting using the IκBα antibody. The normalized figure was presented in the right line. GAPDH or β-actin was used as loading controls.

In addition, p65 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by binding IκB protein under non-stimulated conditions. Upon stimulation with cytokines, pathogens or other stress stimuli, the IκB protein is degraded and releases p65 to translocate into the nucleus [27]. Therefore, based on our above results showing that NLK influences the TNFα-induced p65 translocalization, we speculated that degradation of IκBα might be also affected by NLK. Indeed, we observed that overexpression of NLK repressed the degradation of IκBα in TNFα-treated cells (Fig. 4E); in contrast, deficiency of NLK led to the opposite results (Fig. 4F). Put together, these data suggest that NLK may affect NF-κB signaling through interrupting the degradation of IκBα.

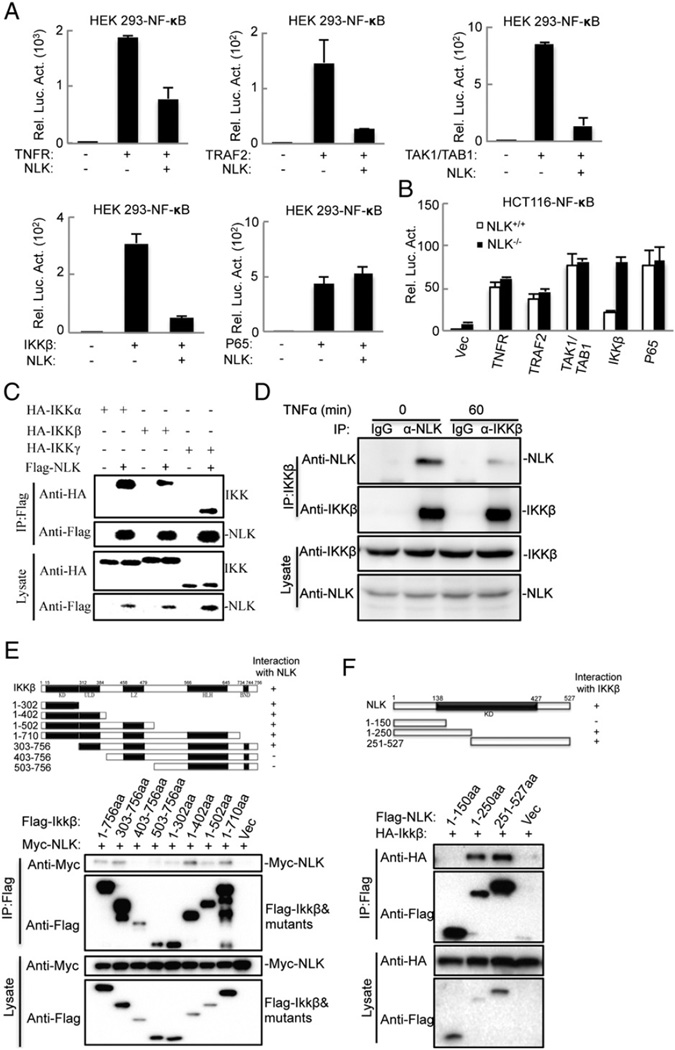

3.4. NLK interacts with the IKK complex

To further dissect the role of NLK in TNFα-induced activation of NF-κB signaling, we co-expressed several NF-κB signaling proteins in HEK293 cells in the presence or absence of NLK. We found that NLK inhibited the activation of IKKβ as well as its upstream components TNFR, TRAF2 and TAK1/TAB1. However, NLK did not repress p65-induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 5A). We also found that expression IKKβ but not p65 strongly accelerated NF-κB activation in NLK−/− HCT116 cells than in its paternal cells (Fig. 5B). Also, we examined the binding capacity of NLK to its different components, using a competitive coimmunoprecipitation. The results showed that NLK interacted with the IKK complex and TAK1/TAB1, but not with p65 (Figs. 5C and S3). Moreover, an endogenous coimmunoprecipitation analysis revealed that NLK strongly interacted with IKKβ, but TNFα stimulation reduced the NLK–IKK complex formation (Fig. 5D). This suggests that NLK may orchestrate NF-κB signaling at the IKK complex stage.

Fig. 5.

NLK associates with IKK complex. (A) and (B) NLK inhibits TNFα-induced NF-κB activation at IKKβ level. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Then the cells were lysed and subjected to luciferase assays. (B) NLK+/+ and NLK−/− HCT116 cells were transfected with NF-κB reporter plasmid (50 ng) and the indicated plasmids. 24 h after transfection, the cells were lysed before luciferase experiments were performed. (C) NLK interaction with IKKα, IKKβ, IKKγ. The HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-IKKα, HA-IKKβ, HA-IKKγ (NEMO) and Flag-NLK. 24 h later, the cells were lysed and spun down. The supernatants were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation and subsequently immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (D) Endogenous interaction between NLK and IKKβ. HEK293 cells (3 × 107) were treated with or without TNFα (20 ng/ml) for 60 min. The supernatants were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation and subsequently immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (E) Interaction of IKKβ mutants and NLK. HEK293 cells were transfected with NLK and various IKKβ mutants. 24 h later, the cells were lysed and spun down. The supernatants were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation and subsequently immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (F) NLK mutants interacted with IKKβ. The identical experiments were performed as in panel E.

Because IKKβ is the main player in the canonical NF-κB pathway, we map the regions in IKKβ that interact with NLK. A series of IKKβ-deletion constructs were generated and co-expressed with Flag-tagged NLK. We found that the kinase domain and ubiquitin-like domain were both essential for its interaction with NLK (Fig. 5E). This was evidenced by the fact that the NLK/IKKβ complex potentially disrupted the phosphorylation of IKKβ. The domain mapping analysis further revealed that the C-terminal region of NLK was required for such an interaction (Fig. 5F).

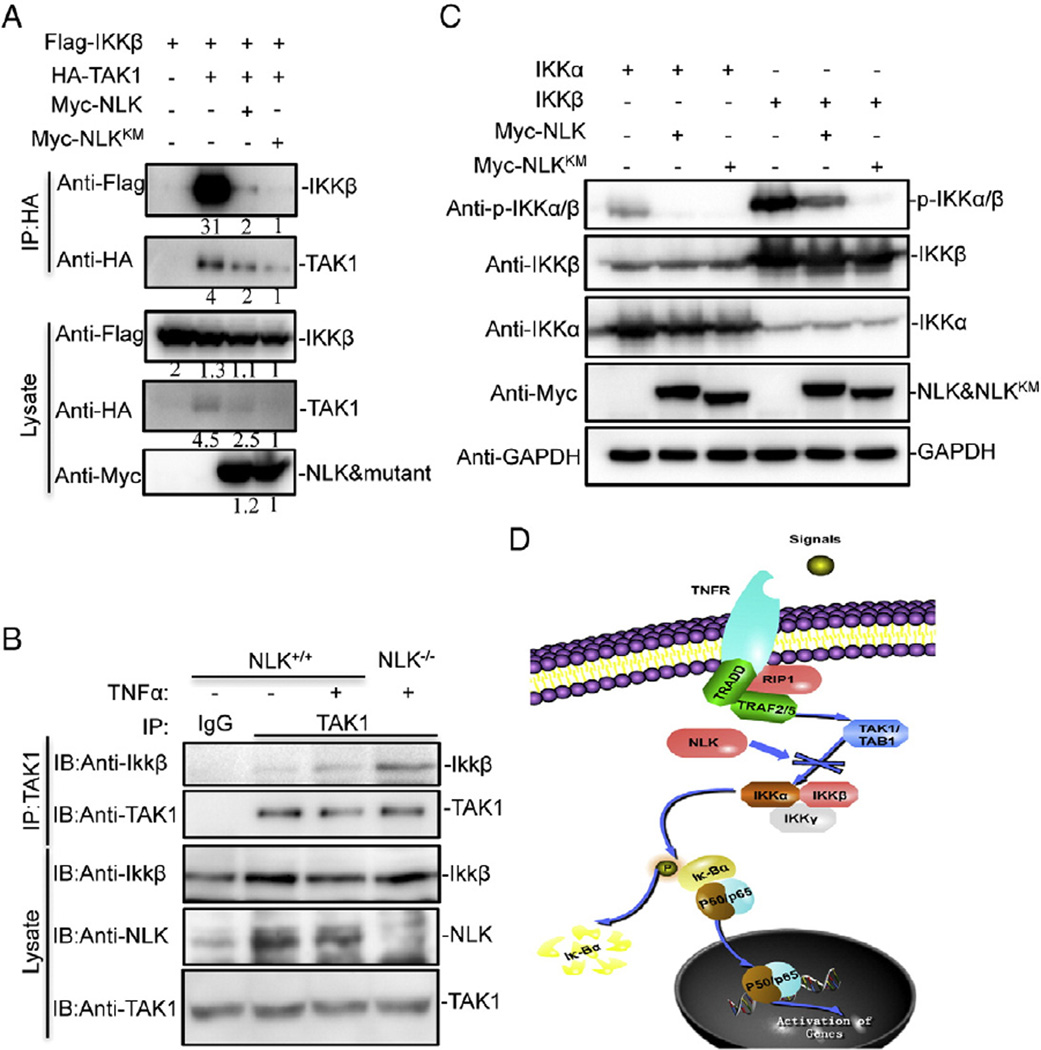

3.5. NLK disrupts the interaction between TAK1 and IKKβ

It has been demonstrated that NLK associates with TAK1 and as a consequence, negatively regulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [28, 29]. In the TNFα-induced NF-κB signaling cascade, the TAK1-mediated activation of downstream kinases (IKKα and IKKβ) is the central event that transmits the signal to activate p65 [30]. The data presented above suggest that NLK may be tightly associated with the IKK complex. However, whether NLK can influence the assembly of TAK1/IKK complex remains unclear. To this end, we co-transfected Flag-tagged IKKβ and HA-tagged TAK1 into HEK293 cells, together with either Myc-tagged NLK or NLK mutants. Co-IP results exhibited that overexpression of NLK significantly attenuated assembly of TAK1/IKKβ (Fig. 6A). We next determined whether deficiency of NLK enhanced the recruitment of TAK1 to IKKβ, and found that loss of NLK promoted the TNFα-induced association of TAK1 with IKKβ (Fig. 6B). In similar experiments, we observed that NLK also attenuated assembly of TAK1/IKKα (Fig. S4). In addition, we found that NLK did not affect the interaction of NEMO with IKKα/IKKβ (Fig. S5).

Fig. 6.

NLK affects the interaction between TAK1 and IKKβ and IκB kinase phosphorylation. (A) and (B) NLK affected the assembly of TAK1 and IKKβ. (A) Myc-NLK, Flag-IKKβ and HA-TAK1 were transfected into HEK293 cells. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag-beads and immunoblotted with the indicated antibody. (B) NLK+/+ and NLK−/− HCT116 cells (5 × 107) were treated with or without TNFα (20 ng/ml) for 30 min. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with TAK1 antibody or IgG and protein G followed by immuno-blotting with the indicated antibody. (C) NLK inhibits the phosphorylation of IKKα and IKKβ. HEK293 cells were transfected with IKKα, IKKβ with or without Myc-NLK and Myc-NLKKM. Then the phosphorylation levels of IKKα and IKKβ were detected by immunoblots. GAPDH was used as the loading control.

To confirm the regulation of NLK-mediated regulation of NF-κB signaling through disrupting the IKK complex, we further analyzed the phosphorylation of IKKα and IKKβ in NLK- and its mutant-overexpressing cells. Consistently, markedly decreased IKKα and IKKβ phosphorylation was observed in the presence of either NLK or NLK mutants (Fig. 6C). Collectively, these data indicate that NLK negatively regulates TNFα-induced NF-κB activation through disrupting the TAK1/IKK complex (Fig. 6D),which consequently impairs the IKK phosphorylation and its downstream signal cascades.

4. Discussion

The NF-κB pathway, strictly controlled by the IKK complex, is crucial to cell survival, proliferation, inflammation and immune regulation. In particular, negative regulation of the NF-κB pathway is well appreciated to avoid cellular damage induced by over-activation of inflammatory cytokines. In the present study, we identified NLK as a new negative regulator in the TNFα-induced NF-κB activation.

We observed that overexpression of NLK inhibited TNFα-induced activation of NF-κB and its downstream gene expression. Conversely, knockdown of endogenous NLK expression enhanced the transcriptional activity of NF-κB in response to TNFα. The luciferase reporter analysis further indicated that restoration of NLK in NLK−/− HCT116 cells attenuated the TNFα-triggered activation of NF-κB. Moreover, the RNA sequencing analysis revealed that a set of NF-κB target genes were dys-regulated in NLK−/− HCT116 cells, compared with wild-type HCT116 cells. Collectively, these results provide first evidence that NLK is a suppressor of the NF-κB pathway.

IKKβ is responsible for IκBα phosphorylation and subsequent degradation, which causes p65 translocation to the nucleus [31]. Our results presented in this study indicate that overexpression of NLK retards the degradation of IκBα, and inhibits p65 translocation to the nucleus in response to TNFα stimulation. In addition, we provide evidence showing that NLK physically interacts with the IKK complex. The interaction between NLK and the IKK complex affected phosphorylation of the IKK complex by TAK1. However, how does NLK disrupt the TAK1–IKK complex formation is not very clear. Previously, it has been reported that TAK1 phosphorylates IKKβ and thereby transmits its signals [19]. We have known that NLK binds to the N-terminal region of IKKβ, but whether owing to binding of the IKKβ N-terminal region led to reduction of TAK1 bind to IKK complex is unknown. In other words, TAK1 may bind this region. On the other hand, IKKβ is likely to impact the TAK1/NLK complex by the IKK binding region of NLK. This needs further more experiments to prove it. In the present study, we showed that NLK was involved in the regulation of the TAK1–IKKβ signaling pathway through interfering with the assembly of the TAK1/IKK complexes rather than the NEMO/IKK complexes.

Our data suggest that NLK negatively regulates TAK1-mediated IKKβ phosphorylation by competing with TAK1 to bind to IKKβ. Interestingly, in the absence of TNFα, deficiency of NLK promoted NF-κB activation, compared with wild-type cells. This implicates that the activation of NF-κB is tightly controlled by NLK under physiological conditions. However, although NLK is profoundly involved in NF-κB signaling, the NLK mRNA levels were not altered in NF-κB-activated cells (Fig. S6). Perhaps, TNFα-mediated modification of TAK1 may alter the phosphorylation levels of NLK, which may affect the binding affinity between NLK and IKKβ. In addition, the NLK activity and cellular localization under physiological conditions also need to detect and more studies are necessary to further clarify this question.

In summary, we report here that NLK contributes to maintenance of cellular homeostasis in response to inflammation. NLK balances the elevated phosphorylation of IκB kinases, which acts like a brake to avoid NF-κB over-activation that leads to the aberrant inflammatory response. Given that both TAK1 and IKK complexes are involved in IL-1β- and virus-mediated signaling, the activation of NLK not only regulates the TNFα-induced NF-κB activation, but also likewise participates in IL-1β- and virus-mediated signaling. In this context, the kinase activation of NLK is not necessary for the TNFα-induced NF-κB activation regulation. However, we demonstrate that NLK regulates NF-κB activation by interfering with IKKα and β phosphorylation. Nevertheless, our findings may provide a new perspective to insight into the roles of NLK in TNFα-mediated inflammatory processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Zhenghe Wang for helpful discussions and critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (2011CB944404), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81270306, 30971499), the Trans-Century Training Program Foundation for the Talents by the State Education Commission (NCET-10-0655), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (204275771).

Footnotes

Authors' contributions

S.-Z.L., R.-L.D and X.-D.Z. designed the research; S.-Z.L., H.-H.Z., Y.S., J.-B.L., N.-N.X., and B.-X.J. performed the research; S.-Z.L., H.-H.Z., and X.-D.Z. analyzed the data; S.-Z.L., H.-H.Z., G.-C. F, R.-L.D and X.-D.Z. wrote the paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.028.

References

- 1.Baldwin AS. Control of oncogenesis and cancer therapy resistance by the transcription factor NF-kappaB. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:241–246. doi: 10.1172/JCI11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karin M, Greten FR. NF-κB: linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:749–759. doi: 10.1038/nri1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinz M, Scheidereit C. The IkappaB kinase complex in NF-kappaB regulation and beyond. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:46–461. doi: 10.1002/embr.201337983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan F, Lenardo MJ. The nuclear signaling of NF-kappaB: current knowledge, new insights, and future perspectives. Cell Res. 2010;20:24–33. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zandi E, Chen Y, Karin M. Direct phosphorylation of IkappaB by IKKalpha and IKKbeta: discrimination between free and NF-kappaB-bound substrate. Science. 1998;281:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shambharkar PB, Blonska M, Pappu BP, Li H, You Y, Sakurai H, Darnay BG, Hara H, Penninger J, Lin X. Phosphorylation and ubiquitination of the IkappaB kinase complex by two distinct signaling pathways. EMBO J. 2007;26:1794–1805. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Q, Verma IM. NF-κB regulation in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:725–734. doi: 10.1038/nri910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li D. Selective degradation of the IkappaB kinase (IKK) by autophagy. Cell Res. 2006;16:855–856. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tergaonkar V, Bottero V, Ikawa M, Li Q, Verma IM. IkappaB kinase-independent IkappaBalpha degradation pathway: functional NF-kappaB activity and implications for cancer therapy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:8070–8083. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8070-8083.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker RG, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. NF-kappaB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2011;13:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao X, Pobezinskaya YL, Morgan MJ, Liu ZG. The role of TRADD in TRAIL-induced apoptosis and signaling. FASEB J. 2011;25:1353–1358. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-170480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin WJ, Su YW, Lu YC, Hao Z, Chio II, Chen NJ, Brustle A, Li WY, Mak TW. Crucial role for TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) in regulating NFkappaB2 signaling that contributes to autoimmunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:18354–18359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109427108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen ZJ. Ubiquitination in signaling to and activation of IKK. Immunol. Rev. 2012;246:95–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Israel A. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a000158. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiDonato JA, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf DM, Zandi E, Karin M. A cytokine-responsive IκB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-κB. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zandi E, Rothwarf DM, Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Karin M. The IκB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, necessary for IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Cell. 1997;91:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, Estepa G, Memet S, Israel A, Verma IM. Complete lack of NF-κB activity in IKK1 and IKK2 double-deficient mice: additional defect in neurulation. Gene Dev. 2000;14:1729–1733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takaesu G, Surabhi RM, Park K-J, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Gaynor RB. TAK1 is critical for IκB kinase-mediated activation of the NF-κB pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;326:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, Deng L, Hong M, Akkaraju GR, Inoue J-i, Chen ZJ. TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature. 2001;412:346–351. doi: 10.1038/35085597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brott BK, Pinsky BA, Erikson RL. Nlk is a murine protein kinase related to Erk/MAP kinases and localized in the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:963–968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rago C, Vogelstein B, Bunz F. Genetic knockouts and knockins in human somatic cells. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2734–2746. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Guo C, Chen Y, Shulha HP, Schnetz MP, LaFramboise T, Bartels CF, Markowitz S, Weng Z, Scacheri PC. Epitope tagging of endogenous proteins for genome-wide ChIP-chip studies. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:163–165. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yasuda J, Yokoo H, Yamada T, Kitabayashi I, Sekiya T, Ichikawa H. Nemo-like kinase suppresses a wide range of transcription factors, including nuclear factor-kappaB. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishitani S, Inaba K, Matsumoto K, Ishitani T. Homodimerization of nemo-like kinase is essential for activation and nuclear localization. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2011;22:266–277. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasileva A, Linden RM, Jessberger R. Homologous recombination is required for AAV-mediated gene targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3345–3360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Z, Hagler J, Palombella VJ, Melandri F, Scherer D, Ballard D, Maniatis T. Signal-induced site-specific phosphorylation targets I kappa B alpha to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Gene Dev. 1995;9:1586–1597. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishitani T, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Nagai S-i, Nishita M, Meneghini M, Barker N, Waterman M, Bowerman B, Clevers H, Shibuya H. The TAK1-NLK-MAPK-related pathway antagonizes signalling between β-catenin and transcription factor TCF. Nature. 1999;399:798–802. doi: 10.1038/21674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada M, Ohkawara B, Ichimura N, Hyodo-Miura J, Urushiyama S, Shirakabe K, Shibuya H. Negative regulation of Wnt signalling by HMG2L1, a novel NLK-binding protein. Genes Cells. 2003;8:677–684. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scherer DC, Brockman JA, Chen Z, Maniatis T, Ballard DW. Signal-induced degradation of I kappa B alpha requires site-specific ubiquitination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995;92:11259–11263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Chen Y, Karin M. Positive and negative regulation of IκB kinase activity through IKKβ subunit phosphorylation. Science. 1999;284:309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.