Abstract

This project examines how access issues, ethnicity, and geographic region affect vaccination of children by two years of age in Bolivia. Bolivia’s rich variation in culture and geography results in unequal healthcare utilization even for basic interventions such as childhood vaccination. This study utilizes secondary data from the 2008 Demographic and Health Survey for Bolivia to examine predictors of vaccination completion in children by two years of age. Using logistic regression methods, we control for health system variables (difficulty getting to a health center and type of health center as well as demographic and socio-economic covariates). The results indicated that children whose parents reported distance as a problem in obtaining health care were less likely to have completed all vaccinations. Ethnicity was not independently statistically significant, however, in a sub-analysis, people from the Quechua ethnic group were more likely to report ‘distance as a problem in obtaining healthcare.’ Surprisingly, living in a rural environment has a protective effect on completed vaccinations. However, geographic region did predict significant differences in the probability that children would be fully vaccinated; children in the region with the lowest vaccination completion coverage were 80% less likely to have completed vaccination compared to children in the best performing region, which may indicate unequal access and utilization of health services nationally. Further study of regional differences, urbanicity, and distance as a healthcare access problem will help refine implications for the Bolivian health system.

Keywords: Vaccination, Bolivia, access, ethnicity, Spanish, Quechua, Aimara, child health, health services, public health

Introduction

Childhood vaccination is a widely accepted public health intervention that is cost effective at reducing child mortality and morbidity. In 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) developed the Global Immunization Vision and Strategy (GIVS) with the goal of reaching 90% completed vaccination coverage for key childhood vaccinations in all countries by 2010 (1). The Bolivian Ministry of Health (MOH) adopted the GIVS 90% coverage target, but has not yet been able to achieve the goal. Economic, cultural, and geographic barriers have resulted in differences in healthcare access and utilization across Bolivia, and this study seeks to understand how these aspects predict differences in immunization completion (2).

The World Bank classifies Bolivia as a low middle-income country, with a per capita GDP of $2576 in 2012 (3). The majority of the population subsists on small-scale agriculture, mining, and petty trade (4). Over 50% of the country lives below the national poverty line, and over 20% live in extreme poverty, characterized by insufficient income to buy basic food requirements. Poverty is most severe in rural areas, which is likely due to the lack of adequate technology, infrastructure, job opportunities, and access to education and health and sanitation services.

Bolivia has a unique cultural makeup. It has the largest indigenous population in the Americas. In addition to Spanish, the principal cultural and ethnic groups are Quechua and Aimara, along with other smaller indigenous ethnic groups (5).

Bolivia is divided into nine sub-administrative territories called departments. Departments have some degree of autonomous power administered by the Departmental Assembly and Governor, and each department is represented in the central government through the bicameral legislature. Population and geography vary across departments. La Paz, the most populous department, has over 2 million inhabitants, while the least populous, Pando, has only 110,000 (6).

Vaccinations in low and middle income countries

Vaccination against childhood diseases is considered one of the most successful and cost effective interventions to reduce childhood morbidity and mortality globally (7). The World Health Organization estimates that vaccinations prevent 2.5 million deaths annually (8). Vaccination programs are very cost effective and have economies of scale in both developing and industrialized countries that make them highly sustainable interventions (9).

Globally, there is a general trend of increasing vaccination completion coverage. However many low and middle income countries are still short of the Global Immunization Vision and Strategy (GIVS) goal of 90% coverage, and there is substantial variation in completion coverage between and within countries (10). In many low and middle income countries, there has been a much larger increase in vaccine initiation compared to vaccination completion, so some children are only partially vaccinated (11). Children who are only partially vaccinated do not have the optimum immune benefit of the vaccinations, so studies increasingly focus on predictors of completed vaccination including the third dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine (DTP), and the third dose of polio vaccine (12).

Familial level factors have a significant impact on vaccination completion (13–14). Urban residence frequently predicts completion, as does higher socioeconomic status, higher maternal age and education (15).

Studies in many low and middle income countries have demonstrated that specific aspects of the health system predict under-vaccination, including geographic access problems and provider factors, such as communication and workload (16). Distance to health centers and poor access is one of the most frequently cited reasons for under-vaccination or non-vaccination in low and middle-income countries. Provider type, differentiated as public or private providers, was also a significant predictor in some countries. However, the effect of provider type was inconsistent across countries based on the public health investment and the importance of private providers in the health system.

Vaccination in Bolivia

The trend of increased vaccination coverage holds true for Bolivia, but it is still far short of the GIVS goal. In 2008, less than 65% of the children under 5 were fully vaccinated in La Paz, the department with the lowest completed vaccination coverage (17). An understanding of the predictors of completed vaccination in Bolivia will help to identify variation in completion and elements of the health system, individual and population characteristics that allow the variation to persist. In addition to the healthcare delivery features and familial level characteristics mentioned earlier, Bolivia’s unique cultural and geographic makeup may predict differences in completed vaccination.

Health disparities exist across the different ethnic groups in Bolivia, with indigenous groups having poorer health outcomes than the Spanish population (18). Health disparities arise as a result of direct differences in health and nutritional access, and through mitigating factors such as the influence of culture on socioeconomic status (SES), and education (19). Despite steps in recent years to improve the social and economic standing of indigenous people in Bolivia, these communities are more vulnerable to extreme poverty and food scarcity.

Bolivia’s geographic variation may also contribute to differences in vaccination. Rural communities are often isolated, resulting in significant difference in access to healthcare between rural and urban populations (20). Due to the natural environment and a lack of adequate infrastructure, geographic access to healthcare can be particularly challenging, and distance to health centers may be a large problem in receiving health care. Additionally, the decentralized nature of Bolivia’s Healthcare system relies on the departments to finance and administer public health programs such as vaccinations (21). This could result in departmental differences in available vaccination and primary care programs.

We used data from the 2008 Bolivia Demographic and Health Survey to study how these different aspects influence the odds of having completed early childhood vaccinations. We investigated whether physical access barriers, ethnicity, or department predict completed vaccination in Bolivia, and if physical access barriers varied systematically across ethnicity and department.

Methods

Data came from the 2008 Monitoring and Evaluation to Assess and Use Results Demographic and Health Surveys (MEASURE DHS) from Bolivia. Data was collected through multilevel cluster randomization, clustering on villages or neighborhoods in large cities, and randomized the households interviewed within the clusters to ensure a nationally representative sample (22). The health status and history of all children age 5 and under was reported by their mother or primary female caregiver as part of the survey administered to women.

The study sample was limited to children from 24 months old to 5 years of age (N=4, 833). The reason that the sample was restricted to children from 24 months of age is that Bolivia’s childhood vaccination schedule is complete by 24 months.

Theoretical framework

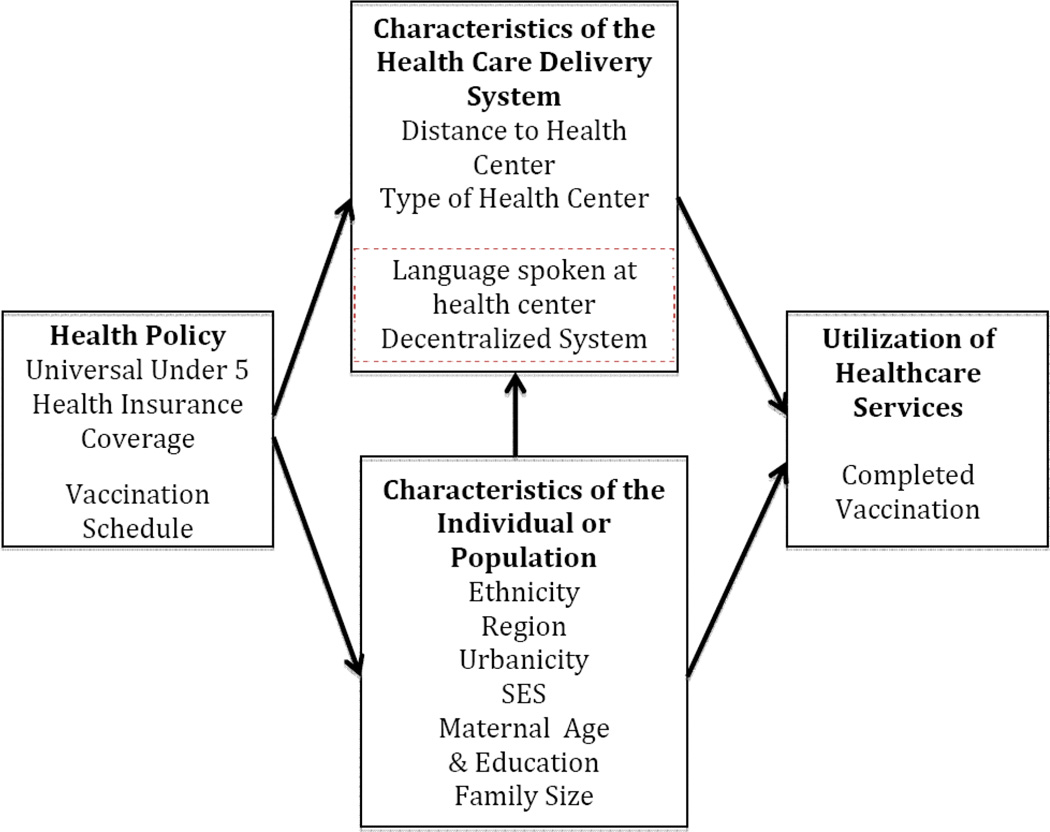

The theoretical framework (see figure 1) was an adapted version of the Aday/Anderson Access Model (23). It traced the health policy of the national vaccination schedule through characteristics of the population and health service delivery system to the resulting variable of interest: utilization of health care services. All children under the age of 5 years have health insurance, so cost of vaccination was not accounted for in this study, but should be noted for the sake of the model. Other studies have shown that the principal characteristics of the health service delivery system that influence completion were physical access and health provider type. Physical access was measured through the proxy “distance to health center is a big problem”, and provider type was categorized as public or private. Language spoken at the health center and the decentralization of Bolivia’s healthcare system are elements of the healthcare delivery system that may influence vaccination completion, but they were not explored in this study due to data limitations, so they are outlined in a light red box. Characteristics of the individual and population were also expected to affect vaccination completion. Geographic location, categorized by department, and ethnicity are important covariates that may have substantial theoretical meaning in Bolivia. Additional aspects that were considered from prior literature on vaccination completion are were familial factors and living in an urban environment. Individual level factors may also influence variation in health systems factors.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for utilization of healthcare services in Bolivia.

For example, ethnicity or geographic location influencing influences the likelihood that distance is an issue in obtaining healthcare, which could affect the final utilization of healthcare services, so that theoretical pathway is also included.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was a binary categorical variable. The categories were: complete vaccinations and incomplete vaccination. Bolivia’s vaccination schedule was adopted from World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, and is completed by 24 months. “Complete vaccination” was defined as having completed Yellow Fever vaccine, three rounds of Polio vaccine, three rounds of Diphtheria, Tetanus Toxoid, and Pertussis vaccine (DTP), a Measles Mumps and Rubella vaccine (MMR) and a Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine (BCG). The sample included children up to 5 years, so completed vaccination may have been delayed but was still completed by the time of the survey. The category “incomplete vaccination” was used if a child had no vaccinations, or some but not all vaccinations in Bolivia’s vaccination schedule by 24 months. These categories have previously been used to assess vaccination coverage in low and middle income countries, and the WHO. Vaccination status in the data comes from vaccination records card or parental recall. Vaccination records included dates of the vaccine but parental recall did not. Both records have potential bias, since parental recall tends to over report vaccination, and using only vaccination records in low and middle income countries frequently underreport vaccination. Using them in combination helps limit the effect of the bias (24).

Key independent variables

The key independent variable in this study is a caregiver-reported measure for difficulty in getting to the health center due to distance. The binary variable categorized the difficulty getting to the health center due to distance as “a big problem” or “not a big problem” according to the child’s caregiver who completed the survey. This variable was a proxy for geographic access to health centers.

Covariates

Covariates account for further differences in completed vaccination. The first covariate was type of health center. This binary variable was divided into public or private health center. Private health center included private providers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and other church-run medical centers. It did not include traditional healers. The four ethnic categories were defined by language: Spanish, Quechua, Aimara, and Other. Other included individuals from indigenous groups with smaller populations, and those whose ethnicity was recorded as “foreigner” in the survey. The geographic categories were defined by the nine departments: Beni, Chuquisaca, Cochabamba, La Paz, Oruro, Pando, Potos?, Santa Cruz, and Tarija. There was no collinearity between the departments and ethnicity. Urbanicity was a binomial variable wherein urban location of residence was defined as large cities, small cities, and towns. All other locations of residence were considered rural. A wealth index was created by MEASURE DHS to accurately measure socioeconomic status in Bolivia accounting for purchasing power and standard of living. Maternal age, maternal education, and family size were family level factors that affect vaccination.

Analysis

To assess the impact of these key issues on vaccination, we performed binary logistic regression accounting for survey weights clustered at the strata of neighborhood or village, with a primary sampling unit of households. Some further analysis allowed us to examine the effect of ethnicity and geography on the probability that caregivers will report distance “is a big problem” in obtaining health care. The equations also use binomial logistic regression to account for survey weights.

Results

Table 1 provides the demographic characteristics of the study sample used in the regression analysis for the sample population adjusted for survey weights. The sample consisted of 4,883 children ages 2–5 years. The caregivers in more than half of the sample (56.56%) reported that distance “is a big problem” in receiving healthcare.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study sample N=4,883a

| Variable | n M | % | Variable | n M | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance is a Problem | 2,759 | 56.56% | Wealth Index | ||

| Public Health Center | 3, 827 | 78.36% | poorest | 1,206 | 24.68% |

| Ethnicity | poorer | 1,018 | 20.84% | ||

| Spanish | 2,876 | 58.89% | middle | 1,086 | 22.24% |

| Quechua | 1,041 | 21.32% | richer | 893.2 | 18.29% |

| Aimara | 469.2 | 9.61% | richest | 681.5 | 13.95% |

| Other | 497.7 | 10.19% | Highest Maternal Education | ||

| Department | none | 304.4 | 6.23% | ||

| Chuquisaca | 318.4 | 6.52% | primary | 2,672 | 54.70% |

| La Paz | 1368 | 28% | secondary | 1,328 | 27.19% |

| Cochabamba | 877 | 17.96% | higher | 580.3 | 11.88% |

| Oruro | 241 | 4.93% | Maternal Age | 30.05 | (0.12) |

| Potosí | 625.1 | 12.59% | Family Size | 5.579 | (0.035) |

| Tarija | 176 | 3.60% | Urban | 2,669 | 54.65% |

| Santa Cruz | 1080 | 22.11% | |||

| Beni | 176.5 | 3.61% | |||

| Pando | 32.66 | 0.67% | |||

Weighted to be nationally representative.

Most of the total sample received medical care at a Public Health Center or Hospital (78%). Ethnic and Departmental representation approximately reflect the population distribution because the survey was weighted to be nationally representative. The average maternal age is 30 years old (SD=0.12 years). The highest level of education completed by the child’s mother is primary education for over half the sample (54.7%), while only 6.23% had no education. Approximately 55% of the sample lived in urban environments.

Bivariate logistic regression was used to analyze predictors of completed vaccination demonstrated through odds ratios (OR) and including the 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) across the independent variables (see table 2). Controlling for all other covariates, children whose caregivers reported that distance “is a big problem” in obtaining healthcare were 25% less likely to complete the recommended vaccines than those whose caregivers reported that distance “was not a big problem”. There was no statistically significant difference in completion rates for children receiving healthcare from private health centers or public health centers. There was also no statistically significant difference in completion rates across ethnicities. Almost every regional department had statistically significant lower odds of completion relative to the omitted reference department of Chuquisaca. Chuquisaca is a smaller department with the historical capital city of Sucre, which may lend it a protective effect, but there was no systematic difference in wealth or resources as collected by DHS that explained this difference. Urbanicity was also a significant predictor of under completion, as children in urban areas are 48% less likely to receive completed vaccinations as children in rural areas.

Table 2.

Analysis of the predicting factors of completed vaccination (N=4,501)

| OR | 95% CI | P>|t| | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance Is A Problem | 0.751 | (0.607 – 0.930) | 0.009** |

| Public Health Center | 1.181 | (0.857 – 1.628) | 0.308 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Spanish | Ref | - | - |

| Quechua | 1.090 | (0.784 – 1.514) | 0.609 |

| Aimara | 0.732 | (0.496 – 1.080) | 0.116 |

| Other Ethnicity | 1.181 | (0.814 – 1.714) | 0.381 |

| Department | |||

| Chuquisaca | Ref | - | - |

| La Paz | 0.199 | (0.119 – 0.334) | <0.001*** |

| Cochabamba | 0.203 | (0.119 – 0.346) | <0.001*** |

| Oruro | 0.274 | (0.152 – 0.492) | <0.001*** |

| Potosi | 0.423 | (0.250 – 0.714) | <0.001*** |

| Tarija | 0.773 | (0.399 – 1.497) | 0.444 |

| Santa Cruz | 0.305 | (0.173 – 0.539) | <0.001*** |

| Beni | 0.397 | (0.198 – 0.749) | 0.009** |

| Pando | 0.332 | (0.166 – 0.663) | 0.002** |

| Urban | 0.507 | (0.317 – 0.814) | 0.005** |

| Wealth Index | |||

| Poorest | Ref | - | - |

| Poor | 1.133 | (0.814 – 1.577) | 0.458 |

| Middle | 1.330 | (0.810 – 2.184) | 0.259 |

| Richer | 1.514 | (0.815 – 2.810) | 0.189 |

| Richest | 1.792 | (0.865 – 3.713) | 0.116 |

| Maternal Education | |||

| None | Ref | - | - |

| Primary | 0.887 | (0.587 – 1.340) | 0.569 |

| Secondary | 1.518 | (0.931 – 2.476) | 0.094 |

| Higher | 1.456 | (0.801 – 2.647) | 0.218 |

| Maternal Age | 0.999 | (0.800 – 1.015) | 0.875 |

| Family Size | 0.995 | (0.943 – 1.050) | 0.856 |

P>0.1

P>0.05

P>0.001.

Further analysis was conducted using bivariate logistic regression to study how the independent variables predicted the outcome variable “distance to health center is a big problem” (see table 3). In this analysis, people of the Quechua ethnic group were 25% more likely to report that distance was “a big problem” in accessing healthcare at a significance level of P=0.06. Departmental differences were also apparent in this model. People in the departments of La Paz are approximately 2.5 times as likely as people in the department of Chuquisaca to report distance as a problem in accessing healthcare, and people in Cochabamba nearly 2 times as likely. Wealth significantly predicted difference in the odds that distance “is a big problem” in accessing healthcare. Compared to the poorest quintile, each subsequently increased wealth quintile indicated lowered odds that the caretaker will report that distance “is a big problem” in obtaining healthcare.

Table 3.

Analysis of the predicting factors of “distance is a big problem in obtaining healthcare” (N=4,826)

| OR | 95% CI | P>|t| | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | |||

| Spanish | Ref | - | |

| Quechua | 1.255 | (0.990 – 1.590) | 0.060* |

| Aimara | 1.010 | (0.747 – 1.364) | 0.950 |

| Other Ethnicity | 0.955 | (0.725 – 1.259) | 0.743 |

| Department | |||

| Chuquisaca | Ref | - | - |

| La Paz | 2.475 | (1.706 – 3.591) | <0.001*** |

| Cochabamba | 1.959 | (1.343 – 2.857) | <0.001*** |

| Oruro | 1.234 | (0.787 – 1.936) | 0.359 |

| Potosi | 1.142 | (0.733 – 1.781) | 0.557 |

| Tarija | 1.792 | (1.155 – 2.781) | 0.009 |

| Santa Cruz | 1.786 | (1.213 – 2.631) | 0.003 |

| Beni | 1.090 | (0.666 – 2.784) | 0.731 |

| Pando | 1.471 | (0.928 – 2.332) | 0.100 |

| Urban | 0.877 | (0.632 – 2.332) | 0.430 |

| Wealth Index | |||

| Poorest | Ref | - | - |

| Poor | 0.452 | (0.333 – 0.613) | <0.001*** |

| Middle | 0.397 | (0.266 – 0.593) | <0.001*** |

| Richer | 0.278 | (0.183 – 0.424) | <0.001*** |

| Richest | 0.188 | (0.110 – 0.321) | <0.001*** |

| Maternal Education | |||

| None | Ref | - | - |

| Primary | 0.945 | (0.649 – 1.378) | 0.770 |

| Secondary | 0.779 | (0.502 – 1.210) | 0.267 |

| Higher | 0.858 | (0.539 – 1.367) | 0.519 |

| Maternal Age | 1.016 | (1.001 – 1.030) | 0.18 |

| Family Size | 1.013 | (0.970 – 1.057) | 0.544 |

P>0.1

P>0.05

P>0.001.

Discussion

Despite growth in Bolivia’s health sector and an increasing trend in increasing vaccination coverage, Bolivia has been unable to meet its goal of 90% immunization coverage.

This investigation utilized nationally representative survey data to study predictors of the binary outcome for completed vaccination by two years of age. After controlling for covariates, children whose caregiver reported distance “is a big problem” in obtaining health care were less likely to have completed vaccinations compared to children whose caregivers reported that distance “is not a big problem.” Interestingly, living in a rural environment actually has a protective effect on completed vaccinations. There were significant differences in outcomes of interest across departments.

In the primary model focusing on the outcome of completed vaccination, almost every department showed significant differences. Children in La Paz, the department with the lowest vaccination completion, are 80% less likely to have complete vaccination compared to Chuquisaca, the department with the highest completion. The variation across departments may have important implications for the health system. In 1996 Bolivia enacted decentralization health reforms as part of the country’s financial decentralization and has since worked to further decentralize the health system (25). The 2003 the Universal Mother and Child Insurance Scheme called the SUMI program further decentralized the health sector because financing occurred at municipal, departmental, and national levels. The goal of these reforms was to allow departmental governments to focus on local priorities and deliver more effective service. The substantial differences in completion of immunization programs across departments could be related to the decentralization. Departments determine which human development programs to develop and fund including health services. Local priorities and available resources drive investment in different programs, and may result in unequal access to health services nationally despite the cost effectiveness of vaccination programs.

Another important result was the lack of significance in ethnicity on the odds of completed vaccination. There has been an effort to improve access to health services for the indigenous population, and this finding suggests that there are not systematic cultural differences external to controlled covariates for income, urbanity, education, and department. However, the odds that distance “is a big problem” in obtaining health care are statistically higher for Quechua people compared to Spanish Bolivians. Though there is not a Quechua specific risk for lowered odds of completed vaccination when accounting for covariates, being Quechua puts you at a higher risk of having trouble obtaining healthcare due to distance. Having trouble obtaining healthcare due to distance may only apply to other health services, or it could in turn increases the risk of not completing vaccination. Distance as a problem in obtaining healthcare may be a result of several factors including the health system, infrastructure, and individual travel capacity. Further study of distance would be beneficial to address this and create policy recommendations that are culturally appropriate.

The protective effect of living in a rural area remains significant even when removing wealth index and education from the equation (data not shown), though the magnitude was slightly reduced. Other studies on health services in Bolivia suggest that rural areas have reduced access to health services which might contribute to a greater perceived need. This could result in funneling additional resources to vaccination campaigns in rural areas. Urban areas have resources for more complex health services, which may cause lower completed vaccination rates through two ways. It may result in reduced investment of preventative health services, such as childhood vaccination, as the funds are allocated to strengthening larger hospital systems. If larger hospitals are the primary available healthcare center, people seeking non-emergent, preventative services may be lower service priorities, which can result in lower receipt of vaccinations. The data set does not include variables such as size of health center, or insight into health services investment priorities on the village or city level, so the specific cause should be explored in further study.

Limitations

The data which made up the immunization report came from both maternal report and health card records. While prior studies have shown that utilizing a mixed report does not alter the validity or significantly bias the result, this does provide some limitations. Maternal reports did not include dates, so studying the timeliness of individual vaccinations could have produced inaccurate results. Since all vaccinations in the program were to be completed by 24 months, that became the cutoff to easily identify complete immunization by the scheduled time. As a result, this study does not include children who died before their second birthday. That presents another limitation because children who died before their second birthday could have died of vaccine preventable disease as a result of not being vaccinated. However, the policy focus for both GIVS and Bolivia is completed vaccination, so limiting the observations to children who should have had completed vaccination focuses the analysis on a policy relevant group.

The second limitation is the variable distance as a big problem in accessing healthcare is a subjective measure, and can be influenced by unmeasured aspects such as the quality of the road, the mode of transportation, and the overall distance. It is a good proxy for understanding the impact of access problems on vaccination completion and caregivers’ perceptions of their healthcare access barriers, but the subjective nature requires further study to understand what is driving the access problems.

A third limitation is that the data comes from self-reported survey data; therefore, information about the health services utilization was limited to personal experience and knowledge, as well as by the questions asked. As a result, there is inadequate data on health system specifics to explain the increased risk of not completing vaccinations for urban residents as discussed above, and the protective effect of some departments. However using DHS data allowed for a nationally representative sample of widely accepted questions that incorporate characteristics of the individual and health system in the analysis which presents a more holistic picture of the predictors of childhood vaccination in Bolivia.

Policy and practice implications

Despite the limitations, the results suggest that departmental differences remain substantial and should be addressed to achieve national immunization goals. The national scenario of decentralization in both the financial and health sectors may contribute to these differences in completion across departments. While decentralization may be more efficient, the significant departmental differences in odds of completed childhood vaccination suggest that the result is neither an equitable distribution of resources nor an effective method to achieve the national health goals.

Future research should focus on the extent decentralization policies result in lower vaccination completion rates including comparing department level programs and health structures to determine what policies are associated with better access to health services and improved health outcomes.

The results raise many questions that require further study, but they illustrate important gaps in the health system of Bolivia, most significantly differences across departments, and the surprisingly protective effect of rural areas on immunization completion. The gaps should be explored in further study to provide specific and actionable areas of improvements in the health system to bring vaccination rates to the national goal.

Conclusion

Vaccination is cost effective and provides a substantial public benefit. Bolivia is committed to achieving the GIVS goal of 90% completed vaccination, however they still fall short. The results of this paper show that access problems, urbanicity, and political regions all predict lower odds of vaccination completion. This highlights the cycle of environmental health disparities which results in inequitable vaccination completion in Bolivia. This research lays the foundation to break that cycle by identifying the elements of the personal environment and health services delivery system that result in under-vaccination. In order to close the gap between the current coverage and the goal, further studies should explore the reasons why these issues and differences persist, and what steps can be made to ameliorate them.

Acknowledgments

Additional support for this study came from Break the Cycle of Environmental Health Disparities in Children, a project of the Southeast Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit, Innovative Solutions for Disadvantage and Disability, Sustainability Initiatives at Emory University. Research reported in this publication (to JSL) was supported by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01AI087724. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.World Health Organization United Nations Children's Fund. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Accessed October 26, 2013]. Global immunization vision and strategy 2006–2015. URL: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2005/WHO_IVB_05.05.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frias Mizutany J, Reyes J, Soto J. GAVI Annual Progress Report 2008. La Paz: Plurinational State of Bolivia; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The World Bank. World Bank Data; 2013. [Accessed 2013 Sept 25]. Data by indicators. URL: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD. [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Fund for Agricultural Development. Rural poverty in Bolivia. [Accessed 2014 Jan 17];Rural Poverty Portal. 2010 URL: http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org/country/home/tags/bolivia. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooker J. Indigenous inclusion/black exclusion: race, ethnicity and multicultural citizenship in Latin America. J Lat Am Stud. 2005;37:285–310. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Bolivia Caracteristicas de Populacion y Vivienda: Censo Nacional de Populacion y Vivienda 2012. [Accessed 2014 Jan 19];Bolivian National Institute of Statistics 2012. URL: http://www.ine.gob.bo:8081/censo2012/PDF/resultadosCPV2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloom DE, Canning D, Weston M. The value of vaccination. World Economics. 2005;6(3):15–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO, UNICEF, World Bank. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. State of the world’s vaccines and immunization. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deogaonkar R, Hutubessy R, van der Putten I, Evers S, Jit M. Systematic review of studies evaluating the broader economic impact of vaccination in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:878. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tao W, Petzold M, Forsberg BC. Routine vaccination coverage in low- and middle-income countries: further arguments for accelerating support to child vaccination services. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:20343. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.20343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark A, Sanderson C. Timing of children's vaccinations in 45 low income and middle-income countries: an analysis of survey data. Lancet. 2009;373(9674):1543–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global routine vaccination coverage, 2010. MMWR. 2011;60:1520–1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suresh K, Saxena D. Trends and determinants of immunisation coverage in India. J Indian Med Assoc. 2000;98:10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrne A, Hodge A, Jimenez-Soto E, Morgan A. What works? Strategies to increase reproductive, maternal and child health in difficult to access mountainous locations: a systematic literature review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akmatov MK, Mikolajczyk RT. Timeliness of childhood vaccinations in 31 low and middle-income countries. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2012;66:e14. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.124651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rainey JJ, Watkins M, Ryman TK, Sandhu P, Bo A, Banerjee K. Reasons related to non-vaccination and under-vaccination of children in low and middle income countries: findings from a systematic review of the published literature, 1999–2009. Vaccine. 2011;29(46):8215–8221. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochoa RCLH. Bolivia DHS: Final Report 2008. Calverton, MD: MEASURE DHS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torri MC. Health and indigenous people: intercultural health as a new paradigm toward the reduction of cultural and social marginalization? World Health Popul. 2010;12(1):30–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morales R, Aguilar AM, Calzadilla A. Geography and culture matter for malnutrition in Bolivia. Econ Hum Biol. 2004;2(3):373–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2004.10.007. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry B, Gesler W. Physical access to primary health care in Andean Bolivia. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(9):1177–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bossert TJ, Mier FR, Escalante S, Cardenas M, Guisani B, Capra K, et al. Applied research on decentralization of health care systems in Latin America: Bolivia case study. Boston, MA: Harvard School Public Health, LAC HSR Health System Reform Initiative; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.MEASURE DHS. Methodology. [Accessed 2013 Nov 13];The DHS Program. 2013 URL http://www.measuredhs.com/What-We-Do/Methodology.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9:208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miles M, Ryman TK, Dietz V, Zell E, Luman ET. Validity of vaccination cards and parental recall to estimate vaccination coverage: a systematic review of the literature. Vaccine. 2013;31(12):1560–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pooley B, Ramirez M, de Hilari C. Bolivia’s Health Reform: a response to improve access to obstetric care. Stud Health Serv Organ Policy. 2008;24:199–222. [Google Scholar]