Abstract

One out of four American children are born into poverty, but little is known about the long-term, mental health implications of early deprivation. The more time in poverty from birth-age-9, the worse mental health as emerging adults (n = 196, M = 17.30 years, 53% male). These results maintain independently of concurrent, adult income levels for self-reported externalizing symptoms and a standard learned helplessness behavioral protocol, but internalizing symptoms were unaffected by childhood poverty. We then demonstrate that part of the reason why early poverty exposure is harmful to mental health among emerging adults is because of elevated cumulative risk exposure assessed at age 13. The significant, prospective, longitudinal relations between early childhood poverty and externalizing symptoms plus learned helplessness behavior are mediated, in part, by exposure to a confluence of psychosocial (violence, family turmoil, child separation from family) and physical (noise, crowding, substandard housing) risk factors during adolescence.

A decade of stagnant wages coupled with an enduring economic recession do not bode well for future human capital (Blair & Raver, 2012; Duncan, 2012; Knudsen, Heckman, Cameron, & Shonkoff, 2006; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2009). Consider the magnitude of the problem: approximately 25% of American children currently spend all or part of their early childhood growing up in poverty (US Census, 2011) with worldwide, early childhood poverty rates much worse (WHO, 2008). The economic and human costs of early childhood poverty are immense, ranging from dramatic achievement gaps, elevated psychological distress, to greater morbidity for every major chronic physical disease, eventually resulting in premature mortality (Maholmes & King, 2012). For over half a century, scientists and practioners worldwide have documented social inequalities in physical and psychological health among adults (Adler & Rehkopf, 2008; Adler & Stewart, 2010; Braveman, Egerter, & Williams, 2011; Matthews & Gallo, 2010; WHO, 2008) as well as children (Aber, Bennett, Conley, & Li, 1997; Blair & Raver, 2012; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Chen, Matthews, & Boyce, 2002; Hertzman & Boyce, 2010; Luthar, 1999; McLoyd, 1998; Schreier & Chen, 2013; Shonkoff & Garner, 2012). Moreover, early deprivation portends elevated physical morbidity and mortality later in life, even among the upwardly mobile (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, Chen, & Matthews, 2010; Shonkoff, Boyce, & Mc Ewen, 2009).

Largely absent from research on childhood poverty and well-being is examination of the long-term implications of early deprivation and mental health among emerging adults. We have little information about whether the linkages between poverty exposure early in life shape subsequent psychological health and whether, similar to physical morbidity, this happens irrespective of adult financial circumstances. Moreover, assuming such prospective relations exist, we do not know why they happen. Herein we test two hypotheses: 1. early childhood poverty will lead to elevated psychological impairment later in life, irrespective of adult financial circumstances; 2. this prospective, longitudinal relation will be caused, in part, by exposure to higher levels of cumulative risk factors during the intervening years between early childhood poverty and emerging adulthood.

A large literature reveals both cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence of relations between childhood poverty and psychological distress (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Grant et al., 2003; Luthar, 1999; McLoyd, 1998; Wadsworth, Evans, Grant, Carter, & Duffy, in press). Overall trends suggest the impacts on externalizing relative to internalizing symptoms are more pervasive and that early and sustained early experiences of poverty are especially consequential for children’s psychological well-being (Wadsworth et al., in press). Much less is known about the long-term mental health implications of early childhood poverty, but a few studies suggest that early poverty is a risk factor for subsequent psychopathology, particularly externalizing disorders. For example, socioeconomic status at age 2 led to greater increases in antisocial behavior up to age 14; whereas depression was unaffected (Stroschein, 2005). A similar pattern of externalization data was uncovered among 5 – 12 year olds in a different sample (Schonberg & Shaw, 2007). Low SES at 2 years did not predict singular, elevated internalization or externalization trajectories from ages 2 – 12 years, but early deprivation was associated with accelerating rates of co-occurring internalization and externalization symptomotology (Franti & Henrich, 2010). In a rare, natural experiment on income and child mental health, Native American children in families receiving casino-related, income supplements in comparison to their peers without income supplements had lower levels of externalization, but internalization symptoms were unaffected (Costello, Erkanli, Copeland, & Angold, 2010). Moreover this happened both during childhood and subsequently at ages 19 and 21. In contrast to these studies, poverty early in life predicted elevated depression and anxiety at ages 14 and 21, and the greater the duration of early childhood poverty (i.e., prenatal, 6 months, 5 years), the higher the levels of adolescent and young adult internalization symptoms (Najman et al., 2010). Of additional interest to the present study, the prospective benefits of income supplements in childhood (Costello et al., 2010) or early experiences of non-poverty (Najman et al., 2010) on adult psychopathology occurred independently of concurrent adult income levels. The incorporation of statistical controls for concurrent income in these two longitudinal studies is important from a developmental perspective because the findings strongly suggest that deprivation earlier in life rather than concurrent income is what matters for adult psychopathology.

We build upon this small foundation of prospective studies on early childhood poverty and adult mental health in two respects. One, in addition to self- or caregiver- ratings of psychological well being, we incorporated a behavioral index of learned helplessness. Uncontrollable and chaotic qualities of low-income environments are capable of interfering with a sense of competency, the belief that one is an effective agent in acting on one’s surroundings (Ackerman & Brown, 2010; Fiese, 2006; Peterson, Maier, & Seligman, 1993; White, 1959). Low-income children are more apt to grow up in chaotic residential settings that are in disrepair, noisy, crowded, cluttered, and lacking in routines and structure (Evans, 2004; Vernon-Feagans, Garrett-Peters, De Marco, & Bratsch-Hines, 2012). Thus in addition to expecting a prospective, longitudinal association between early experiences of poverty and elevated internalization and externalization symptoms during emerging adulthood, we hypothesized that experiences of early childhood poverty would also lead to greater susceptibility to learned helplessness later in life. The addition of a behavioral index of psychological well-being provides an important, multimethodological supplement to the literature on childhood poverty and mental health.

The second contribution the present study makes to the nascent literature on early childhood poverty and adult mental health is the examination of an underlying, mediational pathway to help explain why poverty might lead to subsequent, adult psychological distress. We hypothesize that one reason why early childhood poverty can lead to ill mental health in adulthood is because of a surfeit of risk exposures. A vast literature demonstrates that when children are exposed to a confluence of risk factors, their mental health suffers (Evans, Li, & Whipple, in press); Obradovic, Shaffer, & Masten, 2012; Pressman, Klebanov, & Brooks-Gunn, 2012; Sameroff, 2006). In general this literature shows that the more risk factors encountered, the worse the child’s mental health. This cumulative risk exposure – child mental health function has been demonstrated in cross-sectional, longitudinal, and with risk-reduction intervention studies (Evans et al., in press). Moreover across a wide range of behavioral and physical health outcomes, the particular constellation of risk factors does not appear to be critical; instead what seems to matter is the quantity of risk factors encountered (Evans et al., in press; Kraemer, Lowe, & Kupfer, 2005; Sameroff, 2006).

High levels of cumulative risk exposure may be a key component of the experience of early childhood poverty. Children from low-income households, relative to their more affluent peers, are exposed to a high number of cumulative risk factors, ranging from family turmoil to substandard housing (Burchinal, Roberts, Hooper, & Zeisel, 2000; Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1998); (Evans & English, 2002; Federman et al., 1996; Felner et al., 1995; Greenberg, Lengua, Coie, & Pinderhughes, 1999; Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, McCarton, & McCormick, 1998; Liaw & Brooks-Gunn, 1994; Rutter, 1979). We test whether such elevated cumulative risk exposure during early adolescence (13 years) might explain part of the expected association between early childhood poverty (birth to age 9), and subsequent psychological distress in emerging adults (17 years).

Summarizing, this study builds upon the rapidly proliferating literature on childhood poverty and psychological well-being. We examine whether early experiences of family poverty predict disturbances in mental health during emerging adulthood. We also evaluate whether these effects happen independently of adult financial circumstances across multimethodological indicators of adult psychological health. Finally, we test whether the expected, prospective longitudinal relations between early childhood poverty and emerging adult mental health are accounted for, at least in part, by elevated cumulative risk exposures accompanying childhood poverty.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were part of a longitudinal study of rural poverty, cumulative risk, and child development (Evans, 2003; Evans & Kim, 2012). The original sample (M = 9.18 years) was recruited in rural counties in upstate New York using records from public schools, the Cooperative Extension System of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Head Start program, subsidized housing, and other antipoverty programs. In this sample 50% of the participants came from families that were at or below an income-to-needs ratio of 1, which is the U.S. Federal Poverty line. The income-to-needs ratio is an annually adjusted per-capita index. The other half of the sample at recruitment came from families with income-to-needs ratios two to four times the poverty line, which represents the levels of most American families. Additional data were collected when subjects reached mean ages of 13.36 years (Wave 2) and 17.47 years (Wave 3). The final sample analyzed in the present study consisted of 196 participants (M = 17.30 years; 53% male; 95% white) at Wave 3 who had complete information on poverty, psychological symptoms, and cumulative risk exposure.

Procedures

All data were collected in participants’ homes by a pair of experimenters working independently with each participant and their mother. Only one child per household was tested. Each family’s income-to-needs ratio was assessed at each wave of data collection. For each 6 month period of the participant’s life, we also collected information on household composition and adult household members (job title, weekly working hours, and levels of education). These two data sources were used to estimate the proportion of life from birth to age 9 that the participant had lived at or below the poverty line. We defined poverty in this manner because duration of poverty appears particularly critical in childhood development.

Cumulative risk exposure

Cumulative risk exposure was calculated at Wave 2 (age 13) by exposures to three physical (noise, crowding, housing problems) and three psychosocial (family turmoil, separation from family, exposure to violence) risk factors. Noise was measured by a decibel meter over a 2 hour period in the home. Crowding was defined as the ratio of occupants/number of rooms in the home. Housing problems were assessed by trained raters on a standardized scale including structural problems, poor maintenance, cleanliness and clutter, physical hazards, and poor climatic conditions (Evans, Wells, Chan, & Saltzman, 2000). Exposure to social risks was determined by combining mother’s reports on the Life Event and Circumstances checklist (Work, Cowen, Parker, & Wyman, 1990) and youth’s reports on the Adolescent Perceived Events Scale (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001). An event was counted a single time if it was reported by the youth, the mother, or both. Multiple items (yes/no) constituted each social risk factor. For each of the six individual risk factors, risk was coded dichotomously. A score of 1 was given if the youth’s exposure was in the upper quartile for the entire sample’s distribution of continuous risk factor exposure at Wave 2, and a score of 0 was assigned for all lower levels of exposure. Cumulative risk (0-6) was then calculated by summing across the six singular risk factors.

Internalization and externalization symptoms

At Wave 3 the participant rated their internalization and externalization symptoms with the Youth Self Report Inventory (YSR) (Achenbach, 1991) on a 3 point scale from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true) on a series of questions about anxiety and depression (e.g., “I feel lonely,” “ I worry a lot,”) (α = .90) and behavioral conduct problems (e.g., “I get into many fights”) (α = .87). At Wave 1 because of the child’s age, the mother rated the child’s symptoms with the Child Behavior Questionnaire (Rutter, Tizard, & Whitmore, 1970). On a 3 point scale (0 = does not apply, 2 = certainly applies) mothers rated behavioral indications of anxiety and depression (e.g., “ often worries, worried about many things”) as well as behavioral conduct problems (e.g., “bullies other children”). These scales are among the most widely used instruments to assess psychological well-being in nonclinical populations. They have undergone extensive psychometric development across a wide range of samples (Achenbach, 1991; Boyle & Jones, 1985).

Learned helplessness

Learned helplessness was assessed with a standard behavioral protocol adapted for children (Cohen, 1980; Cohen, Evans, Stokols, & Krantz, 1986); Glass & Singer, 1972; Peterson et al., 1993). At wave 3, the participant was given a set of line drawings of geometric figures and instructed to trace over the figure lines without doubling back or lifting their pencil. The participant was given an initial practice puzzle to ensure comprehension of the task and the rules. A pile of identical puzzles was then placed in front of the young adult and he or she was instructed to use as many pieces of paper as needed to solve the puzzle. Participants were instructed to work on the puzzle until solved or until they felt unable to solve it. At that point, the participant could move on to another puzzle. Once the young adult moved on to the second puzzle, he or she could not return to the first puzzle. Unbeknownst to the participant, the first puzzle was unsolvable. The second puzzle was solvable and all subjects solved the second puzzle. The order of the two puzzles was always the same to ensure that all participants experienced success prior to completion of the protocol. A total of 15 minutes was available for the two test puzzles. This task was at the end of the experimental protocol at each wave of data collection. The number of seconds the subject persisted on the first puzzle was the index of learned helplessness. This learned helplessness measure is related to beliefs about personal control, experimental manipulations of control, and chronic exposure to uncontrollable stressors (Cohen, 1980; Cohen et al., 1986; Evans & Stecker, 2004; Glass & Singer, 1972; Peterson et al., 1993). Learned helplessness was assessed in Wave 1 by giving nine year old children 10 minutes to draw linkages between familiar pictures without doubling back or lifting their pencil. Time spent working on the first puzzle, which could not be solved, was the measure of learned helplessness. Children were also given a second, solvable puzzle to work on. Because the amount of time allocated to the learned helplessness protocols was different for Waves 1 and 3, the proportion of total time available was calculated for each wave.

Results

We first evaluated whether childhood poverty predicted mental health outcomes in emerging adulthood irrespective of current financial situation and controlling for baseline mental health levels. Because of skew (.773), the learned helplessness variables were log transformed.

The proportion of time spent in poverty from birth to age 9 significantly predicted externalizing symptoms, b (SE) = 2.75 (1.05), p < .01 and learned helplessness, b (SE) = -.17 (.05), p < .01 in emerging adulthood while controlling prior externalizing (age 9) and learned helplessness (age 9) levels, respectively. Proportion of time spent in poverty during childhood did not, however, predict internalizing symptoms in emerging adulthood, b (SE)= .34 (1.26), n.s. Inclusion of the participant’s current financial condition did not change the models. As shown in Tables 1 and 2 the effect sizes (f2) for the two statistically significant poverty effects are modest (.12, .11) (Cohen, 1988).

Table 1.

Prospective Longitudinal Mediational Analysis of Externalizing Symptoms in Emerging Adulthood (age 17) and Proportion of Time in Poverty (birth – age 9), Statistically Controlling for Externalizing Symptoms (age 9).

| Predictor | Total R2 | Δ R2 | FΔ R2 | df | B(SE) | Effect size f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of life in poverty | .11 | .03 | 6.93* | 1, 194 | 2.75*(1.05) | .12 |

| Cumulative risk | .12 | .04 | 9.81* | 1, 194 | 1.16*(.37) | .14 |

| Proportion of time in poverty controlling for cumulative risk | .13 | .01 | 1.76 | 1, 193 | 1.56(1.18) | .15 |

p <.01.

Table 2.

Prospective Longitudinal Mediational Analysis of Learned Helplessness in Emerging Adulthood (age 17) and Proportion of Time in Poverty (birth – age 9), Statistically Controlling for Learned Helplessness (age 9).

| Predictor | Total R2 | Δ R2 | FΔ R2 | df | B(SE) | Effect size f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of time in poverty | .10 | .06 | 13.28** | 1, 187 | -.17**(.05) | .11 |

| Cumulative risk | .10 | .07 | 13.44** | 1, 187 | -.06**(.02) | .11 |

| Proportion of life in poverty controlling for cumulative risk | .12 | .02 | 4.26* | 1, 186 | -.11*(.05) | .13 |

p <.05;

p <.01.

In both cases, the beta decreases when the mediator, cumulative risks, is controlled for demonstrating the intervening effect of cumulative risk. In the case of externalizing symptoms, full mediation is indicated given the partial b weight for poverty is nonsignificant with the inclusion of the mediator in the equation (see line 3, Table 1). In the case of learned helplessness, partial mediation is indicated since the b weight for poverty, although smaller, remains significant when the mediator is included in the equation (line 3, Table 2).

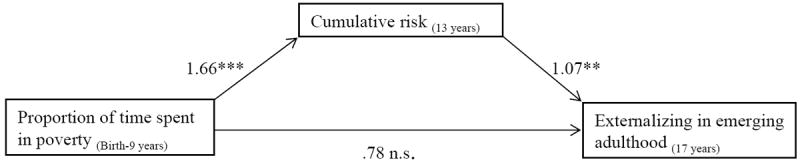

Figures 1 and 2 depict the direct and indirect models utilizing regression with robust standard error terms and a bootstrapping test for the indirect effect (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). As shown in Figure 1, cumulative risk exposure at age 13 mediated the effects of early childhood poverty on externalizing symptoms in 17 year olds. The 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect of cumulative risk exposure (.58 – 3.36) indicates that the covariance between duration of poverty was significantly attenuated.

Figure 1.

Unstandardized regression coefficients for the relations between proportion of time spent in poverty and externalizing symptoms in emerging adulthood and the mediator cumulative risk. Note these analyses are prospective, longitudinal and include an index of prior externalizing symptoms.

*p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001.

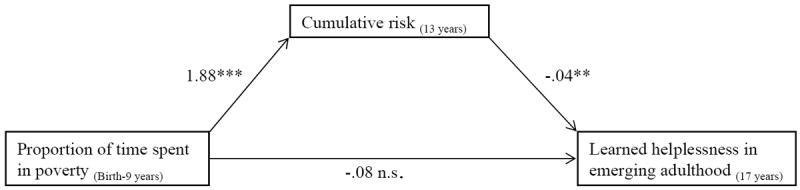

Figure 2.

Unstandardized regression coefficients for the relationship between proportion of time spent in poverty and learned helplessness in emerging adulthood as mediated by cumulative risk.

*p < .05 **p < .01***p < .001

As shown in Figure 2, cumulative risk exposure during adolescence (age 13) also accounted for some of the covariation between early childhood poverty and helplessness in emerging adulthood, 95% CI = -.16 - -.01.

Discussion

Emerging adults who grew up in poverty from birth to age 9 evidence greater externalizing symptoms and are more susceptible to learned helplessness in comparison to their more affluent counterparts (see Tables 1 and 2). These findings incorporate statistical controls for prior measures at age 9 of externalizing and learned helplessness, respectively. Changes in internalizing symptoms from age 9 to emerging adulthood, however, are unaffected by childhood poverty. Furthermore, the prospective, longitudinal mental health sequelae of early poverty appear to be mediated, at least in part, by elevated cumulative risk exposure during adolescence (see Figures 1 and 2).

Across a wide spectrum of physical and psychological indicators of well-being, low-income persons fare worse (Adler & Rehkopf, 2008; Adler & Stewart, 2010; Blair & Raver, 2012; Braveman et al., 2011; Matthews & Gallo, 2010; World Health Organization, 2008). These trends begin early in life (Aber et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2002; Hertzman & Boyce, 2010; Luthar, 1999; McLoyd, 1998; Schreier & Chen, 2013; Shonkoff & Garner, 2012). Furthermore for physical health outcomes these effects persist throughout mid-life, regardless of adult standard of living (Cohen et al., 2010; Shonkoff et al., 2009). We show that early childhood poverty sets children on a developmental trajectory of poorer behavioral adjustment in emerging adulthood. Furthermore, we have identified cumulative risk exposure as one factor that may help explain this outcome. Our study adds to the emerging data base indicating that similar to physical health, early childhood poverty is harmful for adult’s psychological well-being, independent of adult SES (Costello et al., 2010; Najman et al., 2010). The longer a nine year old child has lived in poverty, the worse his or her mental health at age 17, irrespective of adult income levels. This holds true in prospective, longitudinal analyses of externalization symptoms and a behavioral index of learned helplessness.

The null effects of childhood poverty on internalization symptoms match the overall, mixed pattern found in prior cross sectional studies (Wadsworth et al., in press) and in three longitudinal investigations (Costello et al., 2010; Fanti & Henrich, 2010;Stroschein et al., 2005). The main effects of childhood poverty on externalization symptomology replicate the large and consistent cross sectional data base (Aber et al., 1997; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Luthar, 1999; McLoyd, 1998; Wadsworth et al., in press) and match the small body of longitudinal work (Costello et al., 2010; Schonberg & Shaw, 2007; Stroschein, 2005; Fanti & Henrich, 2010).

Our prospective, longitudinal childhood poverty and learned helplessness findings are consistent with earlier survey work showing that lower SES children in comparison to their more affluent peers have diminished self-efficacy (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 2001) and lower internal locus of control (Battle & Rotter, 1963). Prior work has also shown that income (Evans, Gonnella, Marcynyszyn, Gentile, & Salpekar, 2005) as well as poverty-related risk factor exposure (Brown, 2009) are associated with learned helplessness in elementary school aged children and preschoolers, respectively.

Greater helplessness in children may be a critical, but under studied reason for ubiquitous income-achievement gaps (Duncan, 2012; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Heckman, 2006) that have largely been addressed in terms of parental investments in cognitive stimulation (e.g., books, music, arts) as well as parent to child speech (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Duncan, 2012; Hoff, 2006). Low-income children may also be more likely to struggle academically because of motivational deficits related to helplessness which is a robust predictor of academic performance (Peterson et al., 1993). One potential reason for the link between early childhood poverty and a decline in motivation could be the nature of the environment of childhood poverty. Low-income children are more likely to grow up in chaotic surroundings that include relatively high levels of noise, crowding, substandard housing, coupled with fewer routines and structure in their everyday lives (Ackerman & Brown, 2010; Evans, 2004; Vernon-Feagans et al., 2012). Helplessness is caused by repeated experiences of uncontrollable and unpredictable stimuli (Cohen, 1980; Cohen et al., 1986; Evans & Stecker, 2004; Peterson et al., 1993). Future research on childhood poverty and development over the life course ought to examine the role of uncontrollable and unpredictable experiences in low SES children’s lives. The degree of structure and regularity in early life stressor exposure may matter just as much as the elevated intensities of multiple risk exposures accompanying childhood poverty (Ackerman & Brown, 2010; Fiese, 2006; Vernon-Feagans et al., 2012).

The longer nine year old children lived in poverty, the greater their exposure to cumulative risks during adolescence. This finding fits well with a large environmental justice literature documenting the disproportionate share of substandard physical and social environments low-income families live in (Evans, 2004; Sherman, 1994). This elevated cumulative risk exposure, in turn, appears to mediate the prospective relations between early childhood poverty and both externalization symptomotology and learned helplessness behaviors at age 17. These data are consistent with prior cross-sectional evidence of elevated cumulative risk factor exposure among lower- relative to higher SES children and youth (Burchinal et al., 2000; Deater-Deckard et al., 1998; Evans, 2004; Evans & English, 2002; Federman et al., 1996; Felner et al., 1995; Greenberg et al., 1999; Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, McCarton & McCormick,1998; Liaw & Brooks-Gunn, 1994; Rutter, 1979). The mediating role of cumulative risk exposure in poverty and behavioral adjustment is also consistent with the literature documenting widespread adverse mental health sequelae from cumulative risk exposure during childhood (Evans et al., in press; Obradovic et al., 2012; Pressman et al., 2012; Sameroff, 2006). Herein, we formally introduce elevated cumulative risk exposure as a viable explanatory mechanism linking early childhood poverty to compromised behavioral adjustment during emerging adulthood.

An important limitation of this study is its observational design. Although the data emanate from prospective longitudinal analyses, it is possible that one or more ‘third’ variables could be driving the childhood poverty effects on mental health during emerging adulthood. Inclusion of additional variables as statistical covariates, including maternal education, maternal mental health, maternal stress, and single parent status, had no effects on the statistically significant poverty effects reported herein. Furthermore, these effects ensue independent of concurrent, adult levels of income. Furthermore, reversing the order of terms in the mediational model (i.e., Poverty → Mental health outcome → Cumulative risk) showed that neither YSR scores or helplessness behavior mediated the link between poverty and cumulative risk. If one or more other variables were driving this mediational pathway, reversing the order of terms in the hierarchical regression equation would have yielded the same pattern of data. Recall as well that Costello et al. (2010) demonstrated positive gains in adult behavioral conduct scores in relation to a natural experiment on childhood income supplementation. Other early childhood income supplement experiments focused primarily on cognitive (Duncan, 2012) and physical health (Fernald, Gertler, & Hidrobo, 2012) outcomes have shown comparable gains.

Although the present findings extend what we currently know about early poverty and mental health, several essential questions remain. A critical task for psychologists and others interested in the behavioral impacts of poverty is to better understand the daily lives of children and families contending with financial deprivation. The present study suggests that one key and perhaps unique feature of the environment of childhood poverty is exposure to cumulative risk factors. However this process is likely a dynamic one with certain experiences precipitating other events and circumstances that further pressure the adaptive capacities of children and their families as they contend with poverty. More thinking and analysis is needed to better capture this complex, dynamic process of accumulating risk factor exposures. It is also likely that exposure to risks across multiple domains of life (e.g., home and school) are more difficult to cope with than those experienced within only one domain (Evans et al., in press). We need to develop models of developmentally salient risk domains in order to better capture the ecological context of poverty and related risk exposures.

Developmental neuroscience present new tools and insights that enable us to investigate how the quality and timing of early experiences can shape the brain’s architecture and function. Given well documented covariation between childhood poverty and elevated chronic physiological stress (Blair & Raver, 2012; Evans & Kim, 2013; Evans, Chen, Miller & Seeman, 2012), it should come as no surprise that brain structure and function appear to be affected by early experiences of poverty (Hackman, Farah & Meaney, 2010 ; Gianaros & Manuck, 2010; McEwen & Gianaros, 2010). Some of this emerging work shows, for example, smaller hippocampal and larger amygdala structures as well as less connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala among adults from lower SES backgrounds. There is also indication that the ability of prefrontal cortical structures to downwardly regulate the amygdala is compromised in adults whose families were relatively deprived. The latter matches well with several recent studies showing associations between childhood poverty and disturbances in executive functioning (Evans & Kim, 2010; Lengua, 2012; Wadsworth et al., in press). A major task for researchers and clinicians concerned about the psychological sequelae of childhood poverty is to couple neuropsychological information with more in depth assessment of the dynamic ecological context that envelopes disadvantaged children and their families.

One out of four American children now grow up in poverty, and worldwide the numbers are staggering. We already know the financial and human costs of this tragedy are immense. Psychology has much to contribute in thinking about how poverty can modify critical dimensions of the personal, familial, and community contexts that children need in order to thrive. We also have good theoretical models and emerging tools to investigate how developmental trajectories of fundamental cognitive and socioemotional processes can be altered by growing up in poverty and to illuminate the central role of the brain in the interface between the human ecology of childhood poverty and human development over the life course.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the families who have been participating in this research for two decades. We thank Jana Cooperman, Kim English, Missy Globerman, Matt Kleinman, Rebecca Kurland, Melissa Medoway, Tina Merilees, Chanelle Richards, Adam Rohksar, and Amy Schreier for their assistance with data collection. This research program is supported by the W.T. Grant Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. Mac Arthur Foundation Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health, and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities, 5RC2MD00467.

Footnotes

GWE conceptualized the study and supervised data collection and analysis. RC completed data analysis. GWE and RC drafted the paper.

References

- Aber JL, Bennett NG, Conley DC, Li J. The effects of poverty on child health and development. Annual Review of Public Health. 1997;18:463–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the youth self report. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman BP, Brown ED. Physical and psychosocial turmoil in the home and cognitive development. In: Evans GW, Wachs TD, editors. Chaos and children’s development: Levels of analysis and mechanisms. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. U.S. disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:235–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Stewart J. Health disparities across the lifespan: Meaning, methods, and mechanisms. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:5–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Caprara GV, Pastorelli C. Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children’s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development. 2001;72:187–206. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle ES, Rotter JB. Children’s feelings of personal control as related to social class and ethnic group. Journal of Personality. 1963;31:482–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1963.tb01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Raver CC. Child development in the context of adversity. American Psychologist. 2012;67:309–318. doi: 10.1037/a0027493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M, Jones SJ. Selecting measures of emotional and behavioral disorders of children for use in general populations. Journal of Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry. 1985;26:137–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1985.tb01634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn R. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: Coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health. 2011;32:381–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ED. Persistence in the fact of academic challenge for economically disadvantaged children. Early Childhood Research. 2009;7:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Roberts JE, Hooper S, Zeisel SA. Cumulative risk and early cognitive development: A comparison of statistical risk models. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:793–807. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.6.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Matthews KA, Boyce WT. Socioeconomic differences in children’s health: How and why do these relationships change with age? Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:295–329. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Aftereffects of stress on human performance and social behavior: a review of research and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:82–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Evans GW, Stokols D, Krantz DS. Behavior, health, and environmental stress. New York: Plenum; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Chen E, Matthews KA. Childhood socioeconomic status and adult health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:37–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith J, Saltzman H, Thomsen A, Wadsworth M. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Multiple risk factors in the development of externalizing behavior problems: Group and individual differences. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:469–493. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ. Give us this day our daily breadth. Child Development. 2012;83:6–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW. The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist. 2004;59:77–92. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, English K. The environment of poverty: Multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development. 2002;73:1238–1248. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Gonnella C, Marcynyszyn LA, Gentile L, Salpekar N. The role of chaos in poverty and children’s socioemotional adjustment. Psychological Science. 2005;16:560–565. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self-regulation, and coping. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Li D, Whipple SS. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin. doi: 10.1037/a0031808. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Stecker R. The motivational consequences of environmental stress. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2004;24:143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Wells NM, Chan E, Saltzman H. Housing and mental health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:526–530. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federman M, Garner TI, Short K, Cutter WBI, Kiely J, Levine D, McMillen M. What does it mean to be poor in America? Monthly Labor Review, May. 1996:3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felner RD, Brand S, DuBois DL, Adan A, Mulhall P, Evans E. Socioeconomic disadvantage, proximal environmental experiences and socioemotional and academic adjustment in early adolescence: An investigation of mediated effects model. Child Development. 1995;66:774–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald LC, Gertler PJ, Hidrobo M. Conditional cash transfer programs: Effects on growth, health and development in young children. In: Maholmes V, King RB, editors. The Oxford handbook of poverty and child development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 569–600. [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH. Family routines and rituals. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gianaros PJ, Manuck SB. Neurobiological pathways linking socioeconomic position and health. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72:450–461. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e1a23c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DC, Singer JE. Urban stress: Experiments on noise and social stressors. New York: Academic Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Halpert JA. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:447–466. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Lengua LJ, Coie JD, Pinderhughes EE. Predicting developmental outcomes at school entry using a multiple-risk model: four american communities. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:403–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman DA, Farah MJ, Meaney MJ. Socioeconomic status and the brain: Mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:651–659. doi: 10.1038/nrn2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science. 2006;312:1900–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1128898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzman C, Boyce WT. How experience gets under the skin to create gradients in developmental health. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:329–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E. How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental Review. 2006;26:55–88. [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov P, Brooks-Gunn J, McCarton C, McCormick MC. The contribution of neighborhood and family income to developmental test scores over the first three years of life. Child Development. 1998;69:1426–1430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI, Heckman JJ, Cameron JL, Shonkoff JP. Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:10155–10162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600888103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Lowe KK, Kupfer DJ. To your health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ. Poverty, the development of effortful control, and children’s academic, social, and emotional adjustment. In: Maholmes V, King RB, editors. The Oxford handbook of poverty and child development. 2012. pp. 491–511. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw F, Brooks-Gunn J. Cumulative familial risks and low birth weight children’s cognitive and behavioral development. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:360–372. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Poverty and children’s adjustment. Los Angeles: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Maholmes V, King RB. The Oxford handbook of poverty and child development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Gallo LC. Psychological perspectives on pathways linking socioeconomic status and physical health. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61:501–530. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation:Links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:190–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Hayatbakhsh MR, Clavino A, Bor W, O’Callaghan MJ, Williams GM. Family poverty over the early life course and recurrent adolescent and young adult anxiety and depression: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1719–1723. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradovic J, Shaffer A, Masten AS. Risk and adversity in developmental psychopathology: Progress and future directions. In: Mayes LC, Lewis M, editors. The environment of human development: A handbook of theory and measurement. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2012. pp. 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Maier R, Seligman MEP. Learned helplessness. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling methods for estimating and comparing indirect effects. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman AW, Klebanov PK, Brooks-Gunn J. New approaches to the notion of environmental risk. In: Mayes LC, Lewis M, editors. A developmental environmental measurement handbook. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2012. pp. 152–172. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Beyond health care: New directions to a healthier America 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Protective factors in children’s responses to stress and disadvantage. In: Kent MW, Rolf JE, editors. Primary prevention of psychopathology. Vol. 3. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England; 1979. pp. 49–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Tizard J, Whitmore K. Education, health, and behaviour. London: Longman; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. Identifying risk and protective factors for healthy development. In: Clarke-Stewart A, Dunn J, editors. Families count. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schonberg MS, Shaw DS. Risk factors for boy’s conduct problems in poor and lower-middle-class neighborhoods. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:759–772. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier HMC, Chen E. Socioeconomic status and the health of youth: A multilevel, multidomain approach to conceptualizing pathways. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139:606–654. doi: 10.1037/a0029416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman A. Wasting america’s future. Boston: Beacon; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, Mc Ewen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon-Feagans L, Garrett-Peters P, De Marco A, Bratsch-Hines M. Children living in rural poverty: The role of chaos in early development. In: Maholmes V, King RB, editors. The Oxford handbook of poverty and child development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 448–466. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Evans GW, Grant K, Carter JS, Duffy S. Poverty and the development of psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental psychopathology. 3. New York: Wiley; in press. [Google Scholar]

- White R. Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review. 1959;66:297–333. doi: 10.1037/h0040934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Closing the gap in a generation. WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health; Geneva: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Work W, Cowen E, Parker G, Wyman P. Stress resilient children in an urban setting. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1990;11:3–17. doi: 10.1007/BF01324858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]