Abstract

Background

The Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) is one of the world’s oldest nationwide hospital registries and is used extensively for research. Many studies have validated algorithms for identifying health events in the DNPR, but the reports are fragmented and no overview exists.

Objectives

To review the content, data quality, and research potential of the DNPR.

Methods

We examined the setting, history, aims, content, and classification systems of the DNPR. We searched PubMed and the Danish Medical Journal to create a bibliography of validation studies. We included also studies that were referenced in retrieved papers or known to us beforehand. Methodological considerations related to DNPR data were reviewed.

Results

During 1977–2012, the DNPR registered 8,085,603 persons, accounting for 7,268,857 inpatient, 5,953,405 outpatient, and 5,097,300 emergency department contacts. The DNPR provides nationwide longitudinal registration of detailed administrative and clinical data. It has recorded information on all patients discharged from Danish nonpsychiatric hospitals since 1977 and on psychiatric inpatients and emergency department and outpatient specialty clinic contacts since 1995. For each patient contact, one primary and optional secondary diagnoses are recorded according to the International Classification of Diseases. The DNPR provides a data source to identify diseases, examinations, certain in-hospital medical treatments, and surgical procedures. Long-term temporal trends in hospitalization and treatment rates can be studied. The positive predictive values of diseases and treatments vary widely (<15%–100%). The DNPR data are linkable at the patient level with data from other Danish administrative registries, clinical registries, randomized controlled trials, population surveys, and epidemiologic field studies – enabling researchers to reconstruct individual life and health trajectories for an entire population.

Conclusion

The DNPR is a valuable tool for epidemiological research. However, both its strengths and limitations must be considered when interpreting research results, and continuous validation of its clinical data is essential.

Keywords: epidemiological methods, medical record linkage, registries, research design, validation studies

Introduction

As the role of routine computerized health data in epidemiological research is growing,1 there is a need to examine their strengths and limitations.2,3 Typical shortcomings of such data include limited linkage possibilities, incomplete temporal or geographic coverage, restriction to selected patient groups, and lack of systematic follow-up.4–7 Among the examples, the Dutch nationwide hospital registry has been in operation since 1963, but personal records are anonymized, and therefore not linkable to other data sources.4 Also, the United Kingdom’s Clinical Practice Research Datalink has recorded detailed information on both diagnoses and prescriptions in primary care since 1987 but covers only part of the population and lacks information on patients who leave participating practices.8 In the United States, the collection of routine health data is restricted to specific age groups (eg, Medicare beneficiaries),6 income groups (eg, Medicaid beneficiaries),6 professions (eg, the Veterans Affairs),7 or members of private insurance plans (eg, Kaiser Permanente),9 often without the possibility of linkage or long-term follow-up.

In the Nordic countries, government-funded universal health care, combined with the tradition of record-keeping and individual-level linkage, has led to establishment of extensive networks of interlinkable longitudinal population-based registries covering entire nations.10,11 Patient registries with complete nationwide coverage and individual-level linkage potential have existed in Finland since 1969,12 in Sweden since 1987,13 in Iceland since 1999,14 and in Norway since 2008.15,16

The Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) is one such population-based administrative registry, which has collected data from all Danish hospitals since 1977 with complete nationwide coverage since 1978.17–19 An epidemiologist setting out to use the DNPR must be familiar with the strengths and limitations of its data. Many studies have validated algorithms for identifying health events in the DNPR, but the reports are fragmented and no overview exists. Herein, we review the content and data quality of the DNPR and its potential as a research tool in epidemiology.

Setting

Denmark had 5,580,516 inhabitants in 2012, excluding inhabitants of Greenland and the Faroe Islands.20 Although these areas are part of the Kingdom of Denmark, they are not covered by the DNPR. Since 2007, the Danish healthcare system has had three administrative levels:10,21 1) the state, responsible for legislation, national guidelines, surveillance, and health financing through the Ministry of Health; 2) the regions (n=5), responsible for delivery of primary and hospital-based care; and 3) the municipalities (n=98), responsible for a broad range of welfare services, including school health, child dental treatment, home care, primary disease prevention, and rehabilitation.

The Danish National Health Service provides tax-supported health care for the entire Danish population.10,21 Redistributionist taxation finances ~85% of overall health care costs, including access to general practitioners (GPs), hospitals, outpatient specialty clinics, and partial reimbursement of prescribed medications.21 Of note, outpatient specialty clinics include contacts from hospital-based (ambulatory) specialty clinics but not from private practice specialists or GPs. Patients’ out-of-pocket expenditures cover the remaining costs of medication and dental care.21 Except in emergencies, GPs (including on-call GPs) provide referrals to hospitals and specialists.21 Approximately 4,100 GPs and 4,600 dentists, as well as physiotherapists, chiropractors, and home nurses, work in the primary health care sector.21

The Danish Civil Registration System is a key tool for epidemiological research in Denmark.20,22 This nationwide registry of administrative information was established on April 2, 1968.20 It assigns a unique ten-digit Civil Personal Register (CPR) number to all persons residing in Denmark, allowing for technically easy, cost-effective, and exact individual-level record linkage of all Danish registries.20 The Danish Civil Registration System, which tracks and continuously updates information on migrations and vital status, permits long-term follow-up with accurate censoring at emigration or death.20

DNPR overview

History

In the early 1970s, most nonpsychiatric hospitals in Denmark established computerized Patient Administrative Systems (PASs).1 Initially, individual hospitals collected varying information. To ensure standardized data collection, the Danish Health and Medicines Authority developed a protocol for data collection, in which the unit of observation was the hospital discharge record of an individual patient.23 In 1976, all Danish counties (formerly the main administrative level, replaced by regions in 2007) were requested to submit these data to a central national hospital registry, which formed the basis for the DNPR (Danish, Landspatientregisteret).23 This registry was established in 1977 and achieved complete nationwide coverage in 1978.24

Since its establishment, different names have been used in the literature for the DNPR. Commonly used English terms include the Danish National Hospital Register,18 Danish National Health Registry,19 Danish National Patient Register,17 Danish Hospital Discharge Registry,25 and Danish National Registry of Patients.1 The official English name, as it appears in the registry declaration by the Danish Health and Medicines Authority, is the Danish National Patient Registry, DNPR. This term therefore will be used in this review.

Aims

The official aims of the DNPR are presented in Table 1.26 The primary aim is continuous monitoring of hospital and health services utilization for the Danish Health and Medicines Authority, thus providing a tool for health care planning.26 The registry is also increasingly used to monitor the occurrence of diseases and use of treatments,27 for quality assurance in the hospital sector,28 and for medical research. Since 2002, the DNPR has served as the basis for paying public and private hospitals via the Diagnosis-Related Group system.29,30 The registry also collects data for other health registries, including the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register since 1995,31 the Register of Legally Induced Abortions since 1995,32 the Medical Birth Registry since 1997,33 and the Danish Cancer Registry since 2004.34

Table 1.

Aims of the Danish National Patient Registry

| 1. Form the basis for the Danish Health and Medicines Authority’s hospital statistics |

| 2. Form the basis for health economic calculations |

| 3. Provide the Danish authorities with data to support hospital planning |

| 4. Provide data to support the authorities responsible for hospital inspection |

| 5. Monitor the frequency of various diseases and treatments |

| 6. Provide a sampling frame for longitudinal population-based and clinical research |

| 7. Facilitate quality assurance of Danish health care services |

| 8. Provide hospital physicians with access to patient’s hospitalization histories |

Updates

DNPR data are updated continuously.35 Each regional PAS is required by law to submit standardized data to the DNPR at least monthly, but in practice does so weekly or, for some hospitals, daily. As regional PASs may collect more information than is reportable to the DNPR, the contents of the PASs and the DNPR are overlapping but not identical. The overlapping data are referred to as the common content. The Danish Health and Medicines Authority reports all changes in the common content in its annual report – Common content for basic registration of hospital patients – which includes separate sections for users36 and developers.37 An overview of the registry’s content and structure is also available online.26

Reporting to the DNPR became compulsory in 2003 for private hospitals and private outpatient specialty clinics, excluding private practice specialists and GPs.38,39 Private practice specialists are only obliged to report activities that are not covered by the health insurance scheme (Danish, Sygesikringen). Despite their increasing share in the health sector, the 249 private hospitals and clinics in Denmark generated only 2.2% of the total hospital activity in 2010.40 Registration of care provided by the private sector is mandatory, regardless of whether the referring hospital is public or private, whether out-of-pocket payments are involved, or whether patients are covered by a private health insurance.38,39 However, the reporting from private hospitals and clinics is generally considered incomplete.17,41

DNPR content

Type of data

The content of the DNPR is structured, with each variable having a finite number of possible values.36,37 Information reported to the DNPR includes administrative data, diagnoses, treatments, and examinations (Table 2).26

Table 2.

Content of the Danish National Patient Registry

| Administrative data | |

| CPR number | Unique ten-digit personal identification number assigned at birth or upon emigration |

| Residence | Municipality and region of residence |

| Hospital and department | Hospital and department admitting the patient |

| Patient contact | Inpatient, outpatient (ambulatory), or emergency department contacts |

| Admission type | Acute or nonacute |

| Referred from/referred to | General practitioner, outpatient (ambulatory) clinic, other hospital departments, foreign hospital, no referral (eg, acute admission via ambulance), or death (only applies to “referred to” if death is declared during admission) |

| Referral period | Period from referral date to start date for hospital contact |

| Waiting time | Period from referral date to start date for treatment |

| Contact reason | Reason for the hospital contact: diagnosis, accident, act of violence, suicide attempt, late complications, unknown (eg, unconscious patient), or other (rarely used) |

| Accident | Accident description, when an accident is the contact reason |

| Time specifications | Date and time of inpatient admission/discharge, start/end date for outpatient treatment, date of arrival to/discharge from emergency department, and date of referral (if relevant) |

| Other administrative data | Home visit (AAF6) or out-of-home visit (eg, drop-in center or prison service; AAF7) Treatment status of cancers covered by national treatment guaranties: referred, examined, or under treatment |

| Diagnoses | |

| Primary diagnosis | Main reason for hospitalization. When a patient is being examined and a diagnosis is not yet confirmed, a tentative “obs pro” (observation for) diagnosis may be used (the ICD-10 “Z-codes”) |

| Secondary diagnoses | Optional diagnoses supplementing the primary diagnosis by, eg, describing the underlying chronic disease that is related to the current patient contact |

| Referral diagnosis | Diagnosis given by referring unit as the reason for referral |

| Temporary diagnoses | Diagnoses used only for ongoing nonpsychiatric outpatient contacts and never for completed contacts or for psychiatric contacts |

| Complications | Procedure-related complications, eg, perioperative bleeding or postoperative infections |

| Supplementary codes | Up to 50 codes supplementing the primary diagnosis, typically tentative diagnoses (eg, adding meningitis examination to the primary diagnosis disease of the central nervous system), drug abuse (eg, adding heroin to acute opioid intoxication), drug side effects (eg, adding acetylsalicylic acid to peptic ulcer disease), or cancer stage (eg, adding TNM stage to primary tumor diagnosis) |

| Treatments | |

| Surgery (K) | For example, surgery on the thyroid gland (KBA), lung (KGD), or coronary arteries (KFN) |

| Other treatments (B) | Patient care: eg, dress a wound with sterile bandage (BNPA40) or supra pubic catheter change (BJAZ14) Invasive procedures: eg, implantation of pacemaker (BFCA0)/cardioverter-defibrillator (BFCB0) or radiofrequency ablation (BFFB) Mechanical ventilation: invasive (BGDA0) or noninvasive (BGDA1) Cancer/immune-modulating treatments: antibody or immune-modulating therapy (BOHJ), radiation therapy (BWG), stem cell or bone marrow transplantation (BOQE and BOQF), cytostatic treatment (BWHA), and biological therapies (BWHB) Other medical treatment: eg, fibrinolysis (BOHA1) or initiation of parturition with prostaglandin (BKHD20) Telemedicine: eg, patient counseling by phone (BVAA33A), email (BVAA33B), or video (BVAA33D) Systemic psychotherapy: individual (BRSP1), couple (BRSP2), or family (BRSP3) Physiotherapy or occupational therapy (BVD) Other treatment examples: dialysis (BJFD), medical abortion (BKHD4), electroconvulsive therapy (BRXA1), total parenteral nutrition (BUAL1), and acupuncture (BAFA80) |

| Anesthesia and intensive care (N) | For example, during intensive care (NABB) |

| Examinations | |

| Radiological procedures (U) | For example, angiography (UXA), computed tomography (UXC), magnetic resonance imaging (UXM), X-ray (UXR), and ultrasound scan (UXU) |

| Temporary examinations (W) | Temporary classification of examinations |

| Other examinations (ZZ) | For example, planning rehabilitation (ZZ0175X), distortion product otoacoustic emission (ZZ7307), and cardiotocography (ZZ4233) For example, psychological evaluation (ZZ4991), semistructured diagnostic interview (ZZ4992), writing medical certificate (ZZ0182), providing preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis (ZPL0C), and procedure cancellation due to nonappearance of the patient (ZPP30) |

Abbreviations: CPR, Civil Personal Register; TNM, Classification of malignant tumours based on tumor size (T), lymph node involvement (N) and distant metastasis (M).

Administrative data include personal and admission data. The personal data include patients’ CPR numbers and municipality and region of residence. The admission data include hospital and department codes, admission type (acute or nonacute), patient contact type (inpatient, outpatient, or emergency department [ED]), referral information, contact reason, and dates of admission and discharge.

Diagnoses associated with each hospital contact are registered in the DNPR as one primary diagnosis and, when relevant, secondary diagnoses.36 The primary diagnosis is the main reason for the hospital contact. Secondary diagnoses supplement the primary diagnosis by identifying other relevant diseases related to the current hospital contact, eg, underlying chronic diseases.26,36 An exception (since 2009) is brain death (code: R991), which is registered as a diagnosis secondary to the primary underlying condition leading to brain death.36 In addition to primary and secondary diagnoses, the registry records referral, temporary, procedure-related, and supplementary diagnoses (Table 2). The discharging physician registers all diagnoses at the time of hospital discharge or at the end of an outpatient contact. However, outpatient and inpatient psychiatric contacts with long-term attendance are reported at least monthly.36 ED contacts are registered as completed hospital contacts, regardless of whether patients are transferred to another hospital department.36

Treatments include information on surgery, other treatments (eg, invasive procedures, mechanical ventilation, dialysis, cancer treatments, and psychotherapy), anesthesia, and intensive care (Table 2).

Examinations include radiological procedures and other examinations (Table 2). The attending physician/surgeon registers treatment and examination codes immediately following their completion. Thus, each treatment and examination is assigned to its own exact date, independent of the dates of admission and discharge.

Changes in content over time

Initially, the DNPR recorded information on all inpatient contacts only at nonpsychiatric (somatic) Danish departments,23 whereas psychiatric inpatient contacts were recorded in the Psychiatric Central Research Register from 1969 to 1995, after which it was merged with the DNPR.31 Registration of somatic outpatient contacts started in 1994 but was not complete (including the counties of Ribe, Ringkøbing, and Copenhagen) until 1995. Thus, since 1995, all psychiatric inpatient, psychiatric and somatic outpatient, and ED contacts in Denmark have also been reported to the DNPR.23

The personal data reported to the DNPR have remained unchanged since the registry’s establishment in 1977,36 but over time changes have been made to the admission data, diagnoses, treatments, and examinations.35

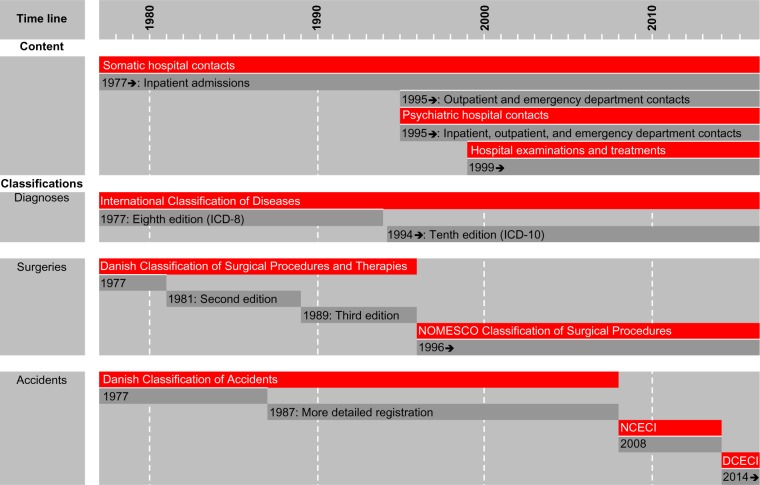

For the admission data, the first change occurred in 1987, whereby registration of patient contacts, referral information, and type of discharge was simplified (Table 3). Changes have been made almost annually thereafter, gradually expanding the registry’s content as shown in Figure 1. The most recent changes to the admission data concerned type of admission and patient contact (Table 3). As of January 1, 2014, ED patients are no longer registered separately as “patient contact type 3” but instead as acute outpatients (ie, “admission type 1” and “patient contact type 2”), whereas other outpatients are registered as nonacute outpatients (ie, “admission type 2” and patient contact type 2). Thus, a patient contact in the DNPR was defined as an inpatient contact from 1977 through 1994; an inpatient, outpatient, or ED contact from 1995 through 2013; and as an inpatient or outpatient contact thereafter.

Table 3.

Time line for patient contact and admission types in the Danish National Patient Registry

| Code | Registration period | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient contact type | ||

| Inpatient | 0 | Jan 1, 2002–ongoing |

| 24 hour patient | 0 | Jan 1, 1977–Dec 31, 2001 |

| Daytime patient | 1 | Jan 1, 1977–Dec 31, 1986 |

| Half-day patient | 1 | Jan 1, 1987–2001 |

| Outpatient | 2 | Jan 1, 1987–ongoing |

| Overnight patient | 2 | Jan 1, 1977–Dec 31, 1986 |

| Emergency department patient | 3 | Jan 1, 1987–Dec 31, 2013 |

| Admission type | ||

| Acute | 1 | Jan 1, 1987–ongoing |

| Nonacute | 2 | Jan 1, 1987–ongoing |

Figure 1.

Timeline for the content and classification systems in the Danish National Patient Registry.

Abbreviations: DCECI, Danish Classification of External Causes of Injury; ed, edition; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; NCECI, Nordic Classification of External Causes of Injury; NOMESCO, Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee.

For diagnoses, it was originally possible to register up to 19 secondary diagnoses (ie, a maximum of 20 diagnoses per contact). Since 1995, the maximum number of recordable secondary diagnoses has increased to 99 in 1995–1998, 999 in 1999–2002, and 9,999 thereafter. Although in practice this means that there is no upper limit to the number of recordable secondary diagnoses, only the first 18 secondary diagnoses are subject to reimbursement by the Danish National Health Service.42 Since the adaption of the tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) in 1994, 23% of hospital contacts have had one or more secondary diagnoses recorded. The median number of secondary diagnoses per contact in this period was 1 (interquartile range: 1–2 diagnoses).

Surgeries have been reported to the DNPR since 1977. Starting in 1999, diagnostic examinations and treatments were included.26,35 It became mandatory to report on many medical treatments in 2001 (including cardiac, respiratory, kidney, and cancer treatments) and on radiological examinations in 2002. The results of examinations are not included in the DNPR (Table 2). Thus, the DNPR records when a patient undergoes magnetic resonance imaging, colonoscopy, biopsy, etc, but the findings are not registered explicitly. In some cases, however, findings may implicitly be inferred from the recorded diagnoses (eg, when an ulcer diagnosis follows procedure coding for gastroscopy).

Number of patient contacts

During 1977–2012, the cumulative Danish population numbered 8,342,199 persons. During this period, 8,085,603 distinct persons were registered in the DNPR at least once. Among these, 7,268,857 (90%) persons were registered with an inpatient contact, 5,953,405 (74%) persons with an outpatient contact, and 5,097,300 (63%) persons with an ED contact. When excluding the unspecific Z-codes (factors influencing health status and contact with health services), the numbers of persons registered with inpatient, outpatient, and ED contacts were 4,610,123, 4,995,365, and 4,792,298, respectively. The distribution of all hospital contacts according to ICD category and patient contact type is shown in Table 4. The 25 most common ICD-10 diagnoses for each patient contact type are provided in Table 5.

Table 4.

Number of patients registered in the Danish National Patient Registry according to disease categories and patient contacts, 1977–2012a

| ICD-8 | ICD-10 | Disease categories | Inpatient contact, n (%) | Outpatient contact, n (%) | Emergency department contact, n (%) | Any patient contact, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | All | All diseases | 7,268,857 (100) | 5,953,405 (100) | 5,097,300 (100) | 8,085,603 (100) |

| 0–139 | A00–B99 | Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | 801,471 (11.0) | 232,080 (3.9) | 104,089 (2.0) | 975,286 (12.1) |

| 140–239 | C00–D48 | Neoplasms | 1,308,247 (18.0) | 910,226 (15.3) | 18,619 (0.4) | 1,599,930 (19.8) |

| 280–289 | D50–D89 | Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs | 351,455 (4.8) | 146,420 (2.5) | 13,779 (0.3) | 416,132 (5.1) |

| 240–279 | E00–E90 | Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases | 972,238 (13.4) | 653,091 (11.0) | 69,610 (1.4) | 1,232,964 (15.2) |

| 290–319 | F00–F99 | Mental and behavioral disorders | 575,514 (7.9) | 218,086 (3.7) | 137,711 (2.7) | 743,981 (9.2) |

| 320–359 | G00–G99 | Diseases of the nervous system | 514,425 (7.1) | 504,543 (8.5) | 90,232 (1.8) | 840,500 (10.4) |

| 360–379 | H00–H59 | Diseases of the eye and adnexa | 295,631 (4.1) | 738,413 (12.4) | 126,565 (2.5) | 997,947 (12.3) |

| 380–389 | H60–H95 | Diseases of the ear and mastoid process | 271,495 (3.7) | 547,612 (9.2) | 42,307 (0.8) | 750,109 (9.3) |

| 390–459 | I00–I99 | Diseases of the circulatory system | 1,971,447 (27.1) | 1,106,198 (18.6) | 311,333 (6.1) | 2,312,646 (28.6) |

| 460–519 | J00–J99 | Diseases of the respiratory system | 1,738,535 (23.9) | 713,021 (12.0) | 204,853 (4.0) | 2,018,882 (25.0) |

| 520–579 | K00–K93 | Diseases of the digestive system | 1,717,940 (23.6) | 1,116,975 (18.8) | 174,675 (3.4) | 2,229,186 (27.6) |

| 680–709 | L00–L99 | Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 421,034 (5.8) | 434,280 (7.3) | 190,607 (3.7) | 824,052 (10.2) |

| 710–739 | M00–M99 | Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disease | 1,178,743 (16.2) | 1,747,207 (29.3) | 440,731 (8.6) | 2,387,728 (29.5) |

| 580–629 | N00–N99 | Diseases of the genitourinary system | 1,527,088 (21.0) | 1,132,468 (19.0) | 123,847 (2.4) | 2,066,692 (25.6) |

| 630–679 | O00–O99 | Pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium | 1,287,919 (17.7) | 429,432 (7.2) | 44,587 (0.9) | 1,321,981 (16.3) |

| 760–779 | P00–P96 | Conditions originating in the perinatal period | 468,787 (6.4) | 75,901 (1.3) | 1,867 (0.0) | 490,506 (6.1) |

| 740–759 | Q00–Q99 | Congenital malformations and deformations | 274,586 (3.8) | 235,560 (4.0) | 4,116 (0.1) | 412,386 (5.1) |

| 780–799 | R00–R99 | Symptoms, signs, and findings not classified elsewhere | 1,952,537 (26.9) | 1,214,203 (20.4) | 655,075 (12.9) | 2,784,868 (34.4) |

| 800–999 | S00–T98 | External causes of injury and poisoning | 2,184,899 (30.1) | 1,751,282 (29.4) | 4,252,799 (83.4) | 5,056,701 (62.5) |

| E00–E99 | X01–Y98 | External causes of morbidity and mortality | 669,066 (9.2) | 756 (0.0) | 27,230 (0.5) | 692,424 (8.6) |

| Y00–Y99 | Z00–Z99 | Factors influencing health and contact with health services | 4,162,984 (57.3) | 4,890,778 (82.2) | 1,894,891 (37.2) | 6,104,084 (75.5) |

Notes:

The disease categories are ordered according to the ICD-10. Both primary and secondary diagnoses were included. A person (ie, one Civil Personal Register number) can contribute in several diseases categories, but only once in each cell.

Abbreviation: ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

Table 5.

The 25 most common ICD-10 diagnoses at the four-digit level in the Danish National Patient Registry, according to patient contact type, 1994–2012a

| Inpatient contact

|

Outpatient contact

|

Emergency department contact

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis (ICD-10 code)

|

n (%)

|

Diagnosis (ICD-10 code)

|

n (%)

|

Diagnosis (ICD-10 code)

|

n (%)

|

| Any | 4,610,123 (100) | Any | 4,995,365 (100) | Any | 4,792,298 (100) |

| 1. Spontaneous vertex delivery (O800) | 466,723 (10.1) | Senile cataract, unspecified (H259) | 287,008 (5.7) | Fracture of lower end of radius (S934) | 590,608 (12.3) |

| 2. Pneumonia, unspecified (J189) | 260,815 (5.7) | Presbycusis (H911) | 193,200 (3.9) | Open wound of finger(s) without damage to nail (S610) | 554,305 (11.6) |

| 3. Abdominal pain, unspecified (R108) | 159,390 (3.5) | Unilateral or unspecified inguinal hernia (K409) | 178,811 (3.6) | Contusion of finger(s) without damage to nail (S600) | 301,454 (6.3) |

| 4. Angina pectoris, unspecified (I209) | 147,605 (3.2) | Meniscus derangement due to tear or injury (M232) | 157,750 (3.2) | Contusion of wrist and hand, exclusion fingers (S602) | 263,753 (5.5) |

| 5. Acute abdomen (R100) | 146,264 (3.2) | Essential hypertension (I109) | 132,992 (2.7) | Fracture of lower end of radius (S525) | 250,339 (5.2) |

| 6. Atrial fibrillation and flutter (I489) | 142,849 (3.1) | Hearing loss, unspecified (H919) | 126,037 (2.5) | Contusion of knee (S800) | 243,863 (5.1) |

| 7. Concussion (S060) | 129,704 (2.8) | Fracture of lower end of radius (S525) | 123,682 (2.5) | Open wound of head, part unspecified (S019) | 242,506 (5.1) |

| 8. Syncope and collapse (R559) | 114,942 (2.5) | Complete or unspecified medical abortion (O049) | 121,821 (2.4) | Open wound of scalp (S010) | 241,943 (5.0) |

| 9. Stroke, unspecified (I649) | 112,366 (2.4) | Angina pectoris, unspecified (I209) | 120,765 (2.4) | Contusion of other and unspecified parts of foot (S903) | 204,344 (4.3) |

| 10. Gastroenteritis of unspecified origin (A099) | 107,339 (2.3) | Tear of meniscus (S832) | 117,493 (2.4) | Sprain and strain of finger(s) (S636) | 199,784 (4.2) |

| 11. Unilateral or unspecified inguinal hernia (K409) | 98,996 (2.1) | Abdominal pain, unspecified (R108) | 117,381 (2.3) | Fracture of other finger (S626) | 171,706 (3.6) |

| 12. Delivery by emergency cesarean section (O821) | 97,505 (2.1) | Varicose veins of lower extremities (I839) | 116,957 (2.3) | Contusion of shoulder and upper arm (S400) | 169,022 (3.5) |

| 13. Volume depletion (E869) | 95,031 (2.1) | Disc disorders with radiculopathy (M511) | 113,217 (2.3) | Sprain and strain of unspecified parts of knee (S836) | 163,976 (3.4) |

| 14. Fracture of neck of femur (S720) | 94,372 (2.0) | Asthma, unspecified (J459) | 106,652 (2.1) | Concussion (S060) | 162,564 (3.4) |

| 15. Calculus of gallbladder, no cholecystitis (K802) | 87,351 (1.9) | Hyperplasia of prostate (N409) | 106,459 (2.1) | Injury of conjunctiva and corneal abrasion (S050) | 155,675 (3.2) |

| 16. Spontaneous breech delivery (O802) | 86,451 (1.9) | Atrial fibrillation and flutter (I489) | 105,710 (2.1) | Open wound of eyelid and periocular area (S011) | 150,449 (3.1) |

| 17. Acute myocardial infarction, unspecified (I219) | 84,800 (1.8) | Unspecified hematuria (R319) | 105,548 (2.1) | Contusion of thorax (S202) | 149,719 (3.1) |

| 18. Cerebral infarction, unspecified (I639) | 84,001 (1.8) | Internal derangement of knee, unspecified (M239) | 104,986 (2.1) | Contusion of elbow (S500) | 147,950 (3.1) |

| 19. Complete or unspecified medical abortion (O049) | 80,284 (1.7) | Carpal tunnel syndrome (G560) | 96,247 (1.9) | Contusion of toe(s) without damage to nail (S901) | 133,673 (2.8) |

| 20. Heart failure, unspecified (I509) | 79,877 (1.7) | Calculus of gallbladder, no cholecystitis (K802) | 94,599 (1.9) | Sprain and strain of wrist (S635) | 133,174 (2.8) |

| 21. Acute appendicitis, unspecified (K359) | 74,769 (1.6) | Impingement syndrome of shoulder (M754) | 91,306 (1.8) | Superficial injury of head, part unspecified (S009) | 117,495 (2.5) |

| 22. Constipation (K590) | 73,162 (1.6) | COPD, unspecified (J449) | 89,555 (1.8) | Superficial injury of scalp (S000) | 117,118 (2.4) |

| 23. Acute cystitis (N300) | 72,768 (1.6) | Other primary gonarthrosis (M171) | 89,528 (1.8) | Open wound of other parts of wrist and hand (S618) | 116,600 (2.4) |

| 24. Vacuum extractor delivery (O814) | 69,842 (1.5) | Pain in limb (M796) | 86,225 (1.7) | Foreign body in cornea (T150) | 115,715 (2.4) |

| 25. Essential hypertension (I109) | 68,799 (1.5) | Low back pain (M545) | 85,920 (1.7) | Sprain and strain of cervical spine (S134) | 114,419 (2.4) |

Notes:

Both primary and secondary diagnoses are included. Factors influencing health status and contact with health services (Z-codes) are not included.

Abbreviation: ICD, International Classification of Diseases; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Classification systems

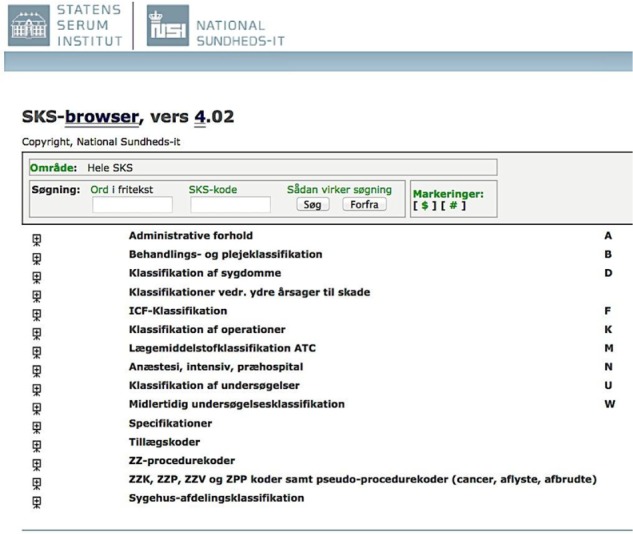

The SKS browser

The classifications used in the DNPR are provided in the Health Care Classification System (Danish, Sundheds-væsenets Klassifikations System [SKS]).43 The SKS is a collection of international, Nordic, and Danish classifications.43 SKS codes contain up to ten alphanumeric characters, the first being a letter representing a primary group, following a monohierarchical classification system.43 Thus, diagnoses are registered under “D”, surgery under “K”, other treatments under “B”, anesthesia under “N”, and examinations under “U” or “ZZ” (Table 2).36

To facilitate the search for SKS codes, the Danish National Health and Medicines Authority maintains a user-friendly SKS browser (Figure 2),44 searchable by code, by free text, or by browsing. Searching for acute myocardial infarction codes can be done by entering “DI21” or by typing the Danish or Latin term in a full phrase (akut myokardieinfarkt) or a partial phrase (eg, infarctus myo).44 Manual browsing requires clicking the main group “Classification of diseases” (group D), then “Diseases of the cardiovascular system” (I), then “Ischemic heart disease” (I20–I25), and finally “Acute myocardial infarction” (I21). The SKS browser does not include historical codes,44 but these are available online elsewhere.45

Figure 2.

User interface of the Danish Health Care Classification System (SKS browser).

Notes: Available at http://www.medinfo.dk/sks/brows.php. English translation (consecutive line order): administrative data/classifications of treatment and care/classification of diseases/classifications of external causes of injury/International Classification of Functioning (ICF)/classification of surgery/Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system/anesthesia, intensive care, prehospital care/classification of examinations/temporary classification of examinations/specifications/supplementary codes/ZZ-procedure codes/ZZK, ZZP, ZZV, and ZPP codes and pseudo procedure codes (cancer, cancelled, discontinued)/classification of hospitals and departments.

Abbreviation: SKS, Sundhedsvæsenets Klassifikations System.

Changes over time

Over time, the DNPR has adopted different classification systems for diagnoses, surgeries, and accidents (Figure 1), whereas the classification systems for radiological procedures and in-hospital medications have remained unchanged since their introduction into the DNPR.26,36

Diagnoses were classified according to the ICD-8 until the end of 1993 and the ICD-10 thereafter. The three-digit ICD-8 codes were used in a modified Danish version (with two supplementary digits), which explains in part why ICD-9 coding was never introduced in Denmark. Coding granularity improved in 1994 through introduction of the five-digit ICD-10 codes. Although the DNPR follows the current international standards for disease classification, the ICD-10 version used in Denmark often does not allow for identification of certain clinical details, such as disease severity. Supplementary codes (eg, the so-called “TUL” codes) sometimes allow for anatomical precision, eg, to identify location of a thrombosis or surgery site in right/left or upper/lower extremity, but these codes are used inconsistently. Sometimes, ABC extensions are added to specific diagnostic codes, eg, atrial fibrillation (I489B) and flutter (I489A), making the Danish version of the ICD-10 more detailed than the international ICD-10 but less detailed than the clinical modification of the ICD-10 (ICD-10-CM), which is not used in Denmark.46

Surgeries were coded according to the three consecutive editions of the Danish Classification of Surgical Procedures and Therapies, from 1977 to 1995.47 Since 1996, surgical procedures have been coded according to the Danish version of the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee Classification of Surgical Procedures.48

Accidents have been coded using the Danish Classification of Accidents. A detailed registration was introduced in 1987. The latest version of the classification, the Nordic Classification of External Causes of Injury, also included suicide attempts and violence.26 It was adopted in 2008 and used until a new Danish Classification of External Causes of Injury was incorporated in the SKS, in 2014.36,37 Although closely related to the Nordic classification in structure, the new Danish classification facilitates a simpler registration of external causes of injury.

Radiological procedures (without results) are coded according to the Danish Classification of Radiological Procedures (UX codes). This classification system follows the general principles used for registration of treatments in the SKS.36

In-hospital medication use (without dispensed dose or route of administration) is registered using different modules consistent with the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. Data on in-hospital medical treatment are not commonly used in research, except for drugs exclusively administered at hospitals, eg, fibrinolysis or cancer/immune-modulating treatments such as antibody, radiation, cytostatic, and biological therapies (Table 2). These drugs are primarily registered with a SKS treatment code, but their ATC codes can also be used as supplemental codes (eg, fibrinolysis is covered by SKS code BOHA1 and ATC code B01AD).

Data quality

Measurements of data quality

The two most common measures of data quality are validity and completeness.49 By validity we refer to the extent to which a variable measures the intended construct.49 The positive predictive value (PPV) of registration is the most frequently reported measure of the validity of records in the DNPR. It is defined as the proportion of patients registered with a disease who truly have the disease and is usually estimated using medical record review as the reference standard to confirm the presence of disease.49 The term reference standard is used here, as medical record is not always considered the gold standard in validation studies, although one must assume that it is a better representation of the truth than the registry record.

Completeness refers to the proportion of true cases of a disease that is correctly captured by the registry.49 Completeness can be measured in relation to either all individuals in the general population with a specific disease or all patients admitted/treated for the specific disease. Completeness is largely determined by the registry’s sensitivity and depends on the amount of missing data.49 Since no complete reference source exists, it is difficult to estimate the overall completeness of registry data relative to the general population. Data completeness depends on hospitalization patterns and diagnostic accuracy. Thus, conditions such as nonfatal myocardial infarction or hip fracture, which should always lead to a hospital encounter, are registered consistently in the DNPR. In contrast, lifestyle risk factors (overweight, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and physical inactivity) and conditions as hypertension or uncomplicated diabetes are often treated by GPs and are thus not completely registered.

Overall data quality

After receiving data from the hospitals, the DNPR automatically checks for missing codes, incorrect digits, errors in CPR numbers, and inconsistencies between diagnoses and sex.24 In case of errors, the records are returned to the source hospital for correction.24

The Danish Health and Medicines Authority has examined the PPVs of personal data, admission data, and diagnoses in the DNPR three times, using medical record review as the reference standard.24,50,51 The first such validation was performed in 1980 as a pilot study of 1,000 randomly sampled discharges from a single hospital (Hillerød Hospital).50 The study concluded that the validity of primary diagnoses in the DNPR was not sufficient for research.50 The secondary study validated 1,094 random discharges from a 1990 nationwide sample and found high overall correlation between admission and discharge data in the DNPR and medical records.24 The proportion of incorrect registrations was 1.4% for admission type, 8.1% for contact reason, 0.8%–8.7% for accident registration (lowest for work-related accidents), 14.8% for the “referral to” variable, and 1.5% for date of discharge. The “referral from” data were incorrect among 11.5% of nonacute patients. However, due to differing guidelines for reporting this variable, there was considerable regional variation in its validity. In the study, diagnoses and surgical procedures were categorized according to five clinical specialties covering 85% of all nonpsychiatric discharges (Table 6). A comparison of various primary diagnoses showed correct categorization at the five-digit level for 73% of all cases, increasing to 83% when alternative diagnoses were accepted. Substantial variation was observed between different clinical specialties, with the lowest PPV for medical diagnoses (66%) and the highest PPV for diagnoses associated with orthopedic surgery (83%). For all specialties, the proportion of correct diagnoses increased substantially when the comparison was made at the three-digit rather than at the five-digit level. It increased even further when secondary diagnoses were also included (Table 6). The third validation study included 420 random discharges from a nationwide sample in 2003 and focused only on admission and discharge data.51 The proportion of incorrect registrations in this sample was 3% for admission type and 8% for referral type. Data on admission/discharge dates, hospital/department codes, and CPR numbers were accurate.51

Table 6.

Summary results from the Danish Health and Medicines Authority’s evaluation of diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry in 1990 according to clinical specialties

| Clinical specialty | Positive predictive value of correct primary diagnoses

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-digit diagnosis codes

|

Three-digit diagnosis codes

|

|||

| Primary diagnosis alone (%) | Primary + two secondary diagnoses (%) | Primary diagnosis alone (%) | Primary + two secondary diagnoses (%) | |

| Medicine | 66 | 72 | 73 | 81 |

| Pediatrics | 74 | 80 | 82 | 89 |

| General surgery | 77 | 82 | 84 | 89 |

| Gynecology/obstetrics | 77 | 88 | 83 | 94 |

| Orthopedic surgery | 83 | 85 | 89 | 91 |

| Overall | 73 | 80 | 81 | 88 |

Systematic review of validated variables

The data quality of individual variables in the DNPR has been examined on an ad hoc basis.25,52–164 To provide researchers with an overview of such studies, we performed a systematic review, aiming to create a bibliography of validated administrative data, diagnoses, treatments, and examinations in the DNPR.

Figure S1 shows a flowchart for the review process, including the search strategy. We searched MEDLINE (PubMed) and the Danish Medical Journal (http://ugeskriftet.dk/udgivelser) using the Danish and the various English names for the DNPR. One author (MS) screened titles and abstracts, and when necessary the full-text papers, for inclusion in the bibliography. Because validation is often a secondary study aim and therefore not highlighted in titles, abstracts, or keywords of papers, even a comprehensive systematic search cannot identify all relevant papers. We therefore also searched the reference lists of the retrieved papers for potentially relevant articles. Finally, we included additional studies known to us beforehand. We included all studies written in English or Danish, regardless of characteristics, such as publication status or year.

Two authors (MS and SAJS) independently extracted the following data from all included papers: patient contact type (inpatient, outpatient, or ED), diagnosis type (primary vs secondary), codes/algorithms used, measure of validity (PPV/negative predictive value), measure of completeness (sensitivity/specificity), the reference standard used, and results (absolute numbers, proportions, and confidence intervals [CIs]). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus. When patient contact, diagnosis type, or codes were not specified, we contacted the corresponding authors for this information. Unspecified patient type included most often both in- and outpatient diagnoses. Unspecified diagnosis type included most often both primary and secondary diagnoses. Unconfirmed data were categorized as not available (n/a). We used extracted information as well as more detailed information from selected studies to illustrate the use of various algorithms over time and to discuss methodological considerations, in particular information bias.

Our review showed that several different methods had been used to calculate CIs for proportions. Moreover, studies varied with respect to the number of decimal points reported for CIs, while some studies failed to report CIs. To permit direct comparisons among study results, we recalculated all proportions based on the absolute numbers provided in the papers. We used Wilson’s score methods to calculate CIs with one decimal point precision.165 When lack of absolute numbers precluded recalculations, we presented the results as reported in the original reference.

We identified 114 papers, validating 1–40 codes/algorithms each and 253 in total. The bibliography of validated variables is provided in Table S1. The variables are listed in the table according to the SKS coding (ie, ICD-10 codes for diagnoses and Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee codes for surgeries) and within each variable according to study period. Recalculation of all proportions reported was possible for 89% (102/114) of all studies.

We found that the PPVs of the reported diagnoses in the DNPR ranged from below 15%137 to 100%.58,97 Some of this variation (both intervariable and intravariable variation) may result from different reference standards used. The majority of variables were examined in cross-sectional studies using medical record review as the reference standard. However, several other reference standards have also been used, including patient interviews,84,146 clinical registries,32,57,78,89,142 the Danish Cancer Registry,59,60,64,67 a military conscription research database,116 the Clinical Laboratory Information System Database,72,73,114 the Danish National Pathology Registry and Data Bank,120 the hospital pharmacy systems,160 the Danish prescription registries,79,83 GP verification,75 radiology reports,111,118 and autopsy reports.110,141 Our review revealed variation in study settings and calendar year. The study setting is important to consider, as the PPV depends on the prevalence of disease and therefore on the data’s department of origin. Thus, restriction to specialized departments, eg, rheumatology departments when examining the validity of a rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis, likely results in higher PPVs.126 Similarly, the calendar year may affect the quality of variables, given the continuous improvement in diagnostic criteria and procedures used. As examples, the validation studies indicate a temporal increase in the PPV of ulcer disease (from 84% during 1997–2001119 to 98% during 1998–200758) and of myocardial infarction (from 92% during 1979–1980,100 94% during 1982–1991,99 to almost 100% during 1996–200997). Improvements in variable completeness over time have also been documented for, eg, bacteremia (from 4.4% in 1994,25 25.1% in 2000,55 to 35.1% in 201155).

We found that the definition of a disease in registry data is not always based on ICD codes alone but may require algorithms that combine a diagnosis with admission data (eg, admission type, patient contact, and department specialty), other diagnostic specification (such as primary vs secondary diagnoses), procedures, in-hospital medical treatment (eg, chemotherapy), prescription use, previous medical history (to identify incident events), time since first diagnosis or metastasis (to identify recurrent events), pathology data (for tumor genotypes),166 or other registry data (eg, laboratory167 and cancer data34). As an example, a validation study of recurrent venous thromboembolism tested different algorithms based on the inpatient vs outpatient diagnoses, presence or absence of an ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan during admission, and postdischarge anticoagulant drug use.112 Based on the results of that study, a case of venous thromboembolism recurrence was defined as an inpatient diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism recorded >3 months after the incident venous thromboembolism event among patients with an ultrasound or CT scan performed during admission (PPV =79%).112 An algorithm for colorectal cancer recurrences combines metastasis and chemotherapy codes in the DNPR with cancer recurrence codes in the Danish National Pathology Registry (PPV =86%; sensitivity =95%).61

Lack of completeness of the DNPR in capturing certain conditions can sometimes be compensated by data linkage to other routine registries. Diabetes can be identified from at least one outpatient dispensation record for insulin or an oral antidiabetic drug (in the Danish prescription registries168) and/or by an inpatient or outpatient hospital diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes in the DNPR.76 Recent studies have supplemented the algorithm with data on glycosylated hemoglobin A1c level of ≥6.5% from the Clinical Laboratory Information System Database, increased specificity by excluding metformin-treated patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome,169 and differentiated type 1 and type 2 diabetes using information on age at diagnosis combined with insulin monotherapy.76

The large variation in data validity found in our review underscores the need to validate diagnoses and treatments before using DNPR data for research. Furthermore, validation studies may need updates, as newer diagnostic criteria and procedures may differ from those used in older validation studies.

DNPR as a research tool

Health events

Potential uses of the DNPR, according to study design, are presented in Table 7. Patient cohorts of interest may be identified, along with their medical history and outcomes. Thus, the DNPR may provide data on diseases,170,171 treatments,172 and diagnostic examinations as exposures. Seasonal variation as an exposure has also been examined.173

Table 7.

Use of the Danish National Patient Registry according to study design

| Cohort studies | Identifying study cohorts from hospitalized patients, the general population (assessed from registries or in combination with primary data collection), and family cohorts (constructed through linkage to the Danish Civil Registration System) |

| Identifying study exposures related to diseases, treatments, examinations, and seasonality | |

| Identifying disease occurrence in the general population (eg, associated with lifestyle factors identified from health surveys) or family cohorts | |

| Identifying disease outcome (recurrence or complications) in patients identified from the DNPR itself, clinical registries, or randomized trials | |

| Identifying health care utilization rates through counting frequency of inpatient/outpatient and planned/unplanned contacts | |

| Identifying temporal trends in disease incidence and use of treatments and diagnostic procedures | |

| Case–control studies | Identifying cases (and exposure from the DNPR, other registries, health surveys, or primary data collection). Risk-set sampling is possible through linkage to the Danish Civil Registration System |

| Cross-sectional studies | Identifying patient’s medical history at study entry according to diagnoses (index disease and comorbidities), treatments (in-hospital medical treatment, surgical procedures, anesthesia, and intensive care), and diagnostic procedures |

| Ecological studies | Identifying variations in health care and outcomes at the population level |

Abbreviation: DNPR, Danish National Patient Registry.

Furthermore, the DNPR allows for identification of disease occurrence in the general population (risk studies),174 where the exposure information could originate from other data sources involving primary or secondary data collection, eg, military conscription cohorts175 or population-based health surveys such as the Danish Health Examination Survey,176 the “How Are You?” study,177 the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health study,178 the Soon Parents cohort,179 the Glostrup Population Studies,180 and the Copenhagen City Heart study.181 Extraordinary long-term follow-up (>35 years) for lifestyle-associated diseases is feasible.175

Using techniques similar to that in risk studies, the DNPR can be used to study outcomes in well-defined patient groups (eg, diagnostic examinations,182 recurrence,112 and complications183) and prognostic factors.170 These patient groups may be identified from the DNPR itself, other registries, or surveys. Most recently, the DNPR has also been used to gather long-term follow-up data for randomized controlled trials using clinically driven outcome detection.184 The automated event-detection feature of the DNPR allows for large, low-cost randomized trials that reflect daily clinical practice, cover a broad range of patients and end points, and include lifelong follow-up.183,185–187 As with cohort studies, DNPR data may be used to identify exposures and cases/outcomes in case– control studies112,188,189 and ecological studies182 (Table 7).

Health care planning

The administrative data related to each patient contact allow for studies of health care utilization and how health care planning may affect patient outcomes. As an example, admission rates for the most common medical conditions in Denmark have been found to be higher during the regular office hours than during the weekend hours.190 However, admissions during the weekend hours have been associated with higher mortality rates (weekend nighttime hours > weekend daytime hours > weekday out-of-hours > weekday office hours).190

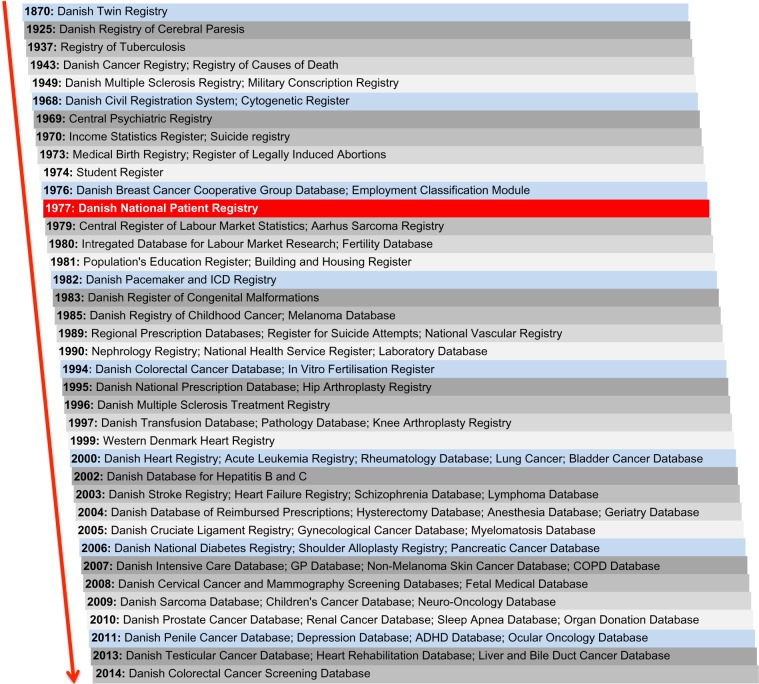

Record linkage

The availability of patient-identifiable data in the DNPR makes it technically easy to link to other Danish data sources using the CPR number.20 Because Denmark’s registries are numerous and far reaching even by the high standards of the Nordic countries,22,191 additional information on, eg, cancer staging,34 laboratory test results,167 general practice utilization,192 socioeconomic data,193–196 prescription use,197 all-cause mortality,20 and cause-specific mortality198 can easily be obtained to supplement the DNPR. Figure 3 shows the time line for the DNPR relative to selected administrative and clinical registries in Denmark, illustrating the potential for record linkage by calendar year. As shown, nationwide data can be obtained on, eg, all twins in Denmark since 1870 (the Danish Twin Registry),199 specific causes of death since 1943 (the Danish Register of Causes of Death),198 detailed cancer diagnoses since 1943 (the Danish Cancer Registry),34 migration and vital status since 1968 (the Danish Civil Registration System),20 personal income since 1970 (the Income Statistics Registry),195 labor market statistics and health services since 1980 (the Integrated Database for Labour Market Research193 and Danish National Health Service Register),192 education since 1981 (the Population’s Education Register),194 prescribed medications since 1995 (the Danish National Prescription Registry),168 and patient tissue samples and blood transfusions since 1997 (the Danish National Pathology Registry and Blood Transfusion Databases).166 The Danish clinical registries constitute the infrastructure of the National Clinical Quality Databases and the Danish Multidisciplinary Cancer Groups.200 The clinical registries contain information about individual patients used for quality improvement, research, and surveillance purposes.200 Linkage to one or more of the current 69 clinical registries thus provides detailed information on a range of procedures (eg, hip arthroplasty and hysterectomy) and diseases (eg, heart failure, stroke, diabetes, and various malignant diseases; Figure 3).200,201 Finally, individual-level linkage to data from randomized controlled trials, population surveys, and epidemiologic field studies is possible as previously described.

Figure 3.

Timeline for the initiation of selected Danish registries linkable to the Danish National Patient Registry.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; GP, general practitioner; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Methodological considerations

Methodological considerations related to the internal validity of cohort studies conducted within the DNPR are summarized subsequently and in Table 8. We also address the special methodological problems that relate to studies of temporal health trends.

Table 8.

Methodological considerations related to the internal validity of cohort studies conducted with data from the Danish National Patient Registry

| Precision | The large nationwide sample permits studies of rare diseases, disease complications, and treatment effects in subgroups of patients |

| Selection bias | The population-based coverage, within a universal health care system with virtually complete follow-up of all patients owing to the Danish Civil Registration System, reduces the risk of selection biases |

| Information bias | The risk of misclassification warrants validation of all variables used for research |

| Confounding | The registrations of diagnoses, treatments, and examinations for all hospital contacts may provide data on potential confounding factors. Seasonality may be controlled in the studies of infectious disease |

Precision

The nationwide coverage since 1978 provides sample sizes that permit studies of rare diseases, disease complications, and effects in subgroups of patients (effect modification and interactions). Of note, very rare diseases may still be difficult to study because of the relatively small size of the Danish population.202

Selection bias

Appropriate population-based study designs can reduce selection biases in cohort studies for three reasons. First, the Danish population has a relatively stable and homogeneous demography with regard to race and religion. Second, the universal health care system (and small private hospital sector)40 prevents selection bias arising from selective inclusion of specific hospitals, health insurance systems, income levels, or age groups. Third, virtually complete follow-up of all patients (with no unrecorded dropouts) is possible because the Danish Civil Registration System records vital status and migrations on a daily basis.20 Still, the cohort represented in the DNPR is only unselected for diseases that always require hospital treatment. For diseases that can be treated in general practice, cases included in the DNPR to some degree represent a selected patient group, with either high severity of the disease in question (eg, herpes zoster infections, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension) or severe comorbidity leading to a lower threshold for hospital admission compared with patients without comorbidity (eg, pneumonia in transplant patients vs in young otherwise healthy adults).

Information bias

Although it is obvious that registration and retrieval of patient information from the DNPR must be based on correct SKS codes, this task is not always easy. The SKS includes many codes that might not be mutually exclusive from a clinical point of view. For many diagnoses, it is thus necessary to be aware of potential differences in registration practice among hospital departments24 and over time.122,170,203

Before engaging in extensive retrieval and analysis of data, it is therefore important to consult clinicians from the relevant specialty to learn about current and previous coding practices. As an example, atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter have separate codes at the four-digit level. However, a large proportion of all diagnoses for atrial fibrillation or flutter are registered as “not elsewhere specified” (Danish, uden nærmere specifikation). Since ~95% of all I48 codes correspond to atrial fibrillation and only 5% to atrial flutter,104 use of the unspecified code will increase the sensitivity of the DNPR-based definition of atrial fibrillation but reduce its specificity. Hence, DNPR studies on risk of atrial fibrillation are often limited by considering atrial fibrillation and flutter as one disease entity.174 Another example is ICD-10 diagnoses of stroke (I60–I64). Approximately one-third of the cases are registered as unspecified stroke (I64),204 and among these, two-thirds are ischemic strokes.91 Inclusion of unspecified diagnoses will increase sensitivity but reduce specificity of stroke subtypes.

The introduction of the Diagnosis-Related Group system in 200229,30 regarding payment to public hospitals may have resulted in more complete registration. However, it may also have affected coding practices for some diseases and certain types of treatments. Private hospitals and clinics are potential sources of underreporting.40 Although it has been mandatory for private health care providers to report all activities since 2003, and the Danish Health and Medicines Authority runs information campaigns to promote registration,38 registration from private hospitals and clinics remains incomplete.17,41 Private hospitals offer services paid by taxes due to the rules of “free hospital choice” or as part of an agreement with a region, as well as services paid privately either by insurance companies or private parties.21,40 Services paid for by private parties have the highest degree of incomplete registration.

In contrast to validity, the completeness of diagnoses is often higher in the DNPR than in the clinical registries.89,100,164,205,206 This higher completeness is expected since many clinical registries receive data from the DNPR. Another reason is that the law requires the national clinical registries to cover only 90% of patients with a given condition.207 Moreover, the degree of completeness varies among and within clinical registries over time.164,208

Confounding

Nonrandomized studies are susceptible to confounding by known and unknown factors.209 Therefore – irrespective of data source – the potential for confounding always needs to be addressed in the study design or analysis. The DNPR provides an opportunity to obtain information on many potential confounders, particularly comorbidities.58,210 The possibility of identifying such covariables from patients’ history of hospital encounters (back to 1977) rather than short-fixed historical windows may also result in less biased estimates.211 Still, it should be kept in mind that incomplete registration of some diagnoses and missing data on other characteristics (eg, lifestyle risk factors212) may leave substantial residual and unmeasured confounding.

Temporal health trends

As data in the DNPR currently span almost four past decades, the registry is a unique data source to monitor long-term temporal trends in use of diagnostic procedures (eg, cardiac CT angiography),164 treatments (eg, use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators),213 and disease incidence (eg, myocardial infarction).27,170 Related particularly to disease incidence, however, a number of methodological problems must be considered.

First, the DNPR only covers patients with disease episodes associated with hospital contact and thus not necessarily the total number of patients with a given disease (as described previously).

Second, lack of information on deaths occurring outside the hospital among persons with no previous hospital contact for a given disease may lead to underestimation of both the disease incidence and the disease-specific mortality. This problem is particularly important for acute critical events such as myocardial infarction.170 Still, it should be noted that a person is not considered legally dead in Denmark before a physician has confirmed clear signs of death. Thus, all patients dying in an ambulance or otherwise arriving at a hospital with no signs of life are also admitted and registered in the DNPR (even when no resuscitation is attempted at the hospital). Data linkage to the Danish Register of Causes of Death198 may help to provide a more complete picture of the incidence of acute fatal events not included in the DNPR.170

Third, it may be difficult – or even impossible – to identify incident diagnoses of chronic diseases in older patients because of immigration or the lack of hospital data before 1977. Thus, events occurring prior to 1977 are left censored if individuals are enrolled in a study and left truncated if they are not.214 On the other hand, the DNPR enables reconstruction of individual life and health trajectories of persons born in 1977 or later.

Fourth, defining incidence by “the first occurrence of the disease in the registry” leads to overestimation of incidence in the period immediately following the initiation of the DNPR, after initiation of a screening program, or after introduction of new registry codes, due to misclassification of “backlogged” prevalent cases as incident cases. Because this problem decreases with the passage of time after 1977 or with the number of screening rounds, a “washout period” before identification of incident cases may reduce the error. This source of error is less important when examining diseases of short duration, such as infections. The transition from ICD-8 to ICD-10 in 1994 and inclusion of outpatients and ED diagnoses in 1995 may similarly introduce artifacts in long-term incidence trends. Exemplifying this problem, the incidence of alcoholic cirrhosis showed no clear trend for men or women of any age from 1988 to 1993 but apparently increased by 32% in 1994 and by an additional 10% when including outpatient and ED visits.122

Fifth, changes in classification systems and diagnostic criteria and use of more sensitive diagnostic methods over time (diagnostic drift) may hamper the interpretation of secular trends in incidence. As an example, a transient increase in the observed rate of hospitalization with myocardial infarction in Denmark between 2000 and 2004 was likely attributable not to the true increase of occurrence but to new diagnostic criteria introduced in 2000, which included troponin as the main diagnostic biomarker.170,215 Similar time-trend biases have been observed for the incidence of primary liver cancer203 and advanced stages of lung cancer, the latter leading to an apparent improvement over time in stage-specific prognosis.216

Data access

The Danish Health and Medicines Authority has established guidelines for releasing data from the DNPR. Implementing the European Union Data Protection Directive (Directive 95/46/EC) on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, the Danish Act on Processing of Personal Data provides the legal basis for private and public institutions to obtain individually identifiable health data for research purposes.217 This Act protects against abuse of such data and thus balances the privacy rights of individuals and the society’s need for quality research. In order to access data from the DNPR, researchers have to apply to Research Service (Danish, Forskerservice).26,218 Use of any health data also requires project-specific permission from the Danish Data Protection Agency,217 and, in many cases, additional permission from the Danish Health and Medicines Authority to link data from various registries.26 The Danish Data Protection Agency specifies safety precautions for data processing and also sets cancellation deadlines, ensuring that data traceable to individuals will not be stored longer than required to complete a project. As well, it is necessary to obtain permission from the Danish Health and Medicines Authority and the chief physician from relevant hospital departments to retrieve medical record files for validation of DNPR data.219

Conclusion

The DNPR is a valuable tool for epidemiological research, providing longitudinal registration of diagnoses, treatments, and examinations, with complete nationwide coverage since 1978. Denmark’s constellation of universal health care, routine and long-standing registration of life and health events, and the possibility of exact individual-level linkage impart virtually unlimited research possibilities onto the DNPR. At the same time, varying completeness and validity of the individual variables underscore the need for validation of its clinical data before using the registry for research.

Supplementary materials

Flowchart for the systematic review of validation studies.

Notes: The literature search was performed on July 20, 2015 using the following search string in 1) PubMed: “Danish National Patient Registry” OR “Danish National Registry of Patients” OR “Danish National Hospital Register” OR “Danish National Health Registry” OR “Danish National Patient Register” OR “Danish Hospital Discharge Registry” OR “Danish National Hospital Registry” OR “Danish Hospital Registers”; and 2) the Danish Medical Journal: “Landspatientregisteret”.

Table S1.

Bibliography of validated administrative data, diagnoses, treatments, and examinations in the Danish National Patient Registry

| ICD codesa | Condition | Study period (contact type; diagnosis type) | ICD codes/algorithmb | nc | PPV; NPV; sensitivity; specificityd | Reference standard | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative data | |||||||

| Acute medical admission | 2009 (IN) | Acute | 127 | PPV =97.6 (93.3–99.2); NPV =90.3 (75.1–96.7); Se =97.6 (93.3–99.2); Sp =90.3 (75.1–96.7) | MR | Vest-Hansen B et al. Clin Epidemiol. 201352 | |

| Nonacute medical admission | 2009 (IN) | Nonacute | 31 | PPV =90.3 (75.1–96.7); NPV =97.6 (93.3–99.2); Se =90.3 (75.1–96.7); Sp =97.6 (93.3–99.2) | MR | Vest-Hansen B et al. Clin Epidemiol. 201352 | |

| Diagnoses | |||||||

| A00–B99: Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | |||||||

| A02 | Infections among patients diagnosed with cancer within previous 5 y (excl non-melanoma skin cancer) | 2006–2010 (IN; A) | A02.1, A02.2C, A15–A19, A20.3, A22.7, A26.7, A42.7, A28.2B, A31, A32.1, A32.7, A39.0, A40–41, A46, A49.9, A54.8D, A54.8G, A87, B00.3, B01.0, B02.1, B26.1, B35–B49, B05.1, G00–G05, H01.0, H03, H60.0, H60.1–H60.3, H62, I33, I39.8, J12–J18, K12.2, K13.0, K61, L01, L03, L08, M00, M01.1, M01.3, M72.6, M86, N10–N12, N15.1, N15.9, N30, N34, N39.0 | 266 | PPV =98.1 (95.7–99.2) overall, 80.1 (75.0–84.5) for agreement of specific infection type, 79.0 (63.7–88.9) for skin infection, 92.5 (85.3–96.3) for pneumonia, 84.4 (71.2–92.3) for sepsis | MR | Holland-Bill L et al. Ann Epidemiol. 201453 |

| A39 | Meningococcal disease | 1980–1993 (IN; A/Be) | 036.09, 036.10, 036.11, 036.12, 036.18, 036.19, 036.89, 036.99 | 296 | PPV =85.8 (81.4–89.3); Se =89.8 (85.7–92.8) | MR (ref for PPV); Notification system for communicable diseases and DNPR (ref for Se) | Sørensen HT et al. Int J Risk Saf Med. 199554 |

| A40 | Septicemia | 1994 (IN; A/Be) | A02.1, A28.2, A40–41, A42.7, A54.8, O08.0, O75.3, O85.9, P36 | 83 | PPV =21.7 (14.2–31.7); Se =4.4 (2.8–6.9) | MR; Bacteremia database | Madsen KM et al. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 199825 |

| Bacteremia | 2000–2011 (IN; A/Be) | Definite (A02.1, A28.2B, A32.7, A39.2–4, A40–1, A42.7, A49.9A, B37.7, B49.9A) or possible (predominantly, A01.0, A39.0, A41.9, A46.9, I38.9, P36, P37.5, N10.9, N30.0, N39.0, O08.0U, O08.0V, KTJA40, KTJWC00, KTJL10) | 37,740 | SeDefinite/possible =64.9 (64.5–65.3) SeDefinite =32.3 (31.9–32.7) |

Microbiology results recorded in electronic laboratory information system | Gradel KO et al. Plos One. 201555 | |

| A41 | Gram-negative bacteremia | 1994–2012 (IN; A/B) | A41.5, A41.9B (septicemia/sepsis due to other Gram-negative organisms or urosepsis) | 100 | PPVAll =72.0 (62.5–79.9); PPVA41.5 =85.7 (74.3–92.6); PPVA41.9B =54.6 (40.1–68.3) | Microbiology results recorded in electronic laboratory information system | Søgaard KK et al. Clin Epidemiol. 201456 |

| B18.0 | HBV in HIV patients | 1995–2004 (IN/OUT; A/Be) | B18.0–B18.1 | 47 | PPV =63.8 (49.5–76.0); Se =23.3 (16.8–31.3) | Danish HIV Cohort Study | Obel N et al. BMC Med Res Methodol. 200857 |

| B18.2 | HCV in HIV patients | 1995–2004 (IN/OUT; A/Be) | B18.2 | 134 | PPV =94.0 (88.7–96.9); Se =47.7 (41.8–53.7) | Danish HIV Cohort Study | Obel N et al. BMC Med Res Methodol. 200857 |

| B20 | HIV | 1995–2004 (IN/OUT; A/Be) | B20–B24 | n/a (≥2006) | Se =98.7 (98.1–99.1) | Danish HIV Cohort Study | Obel N et al. BMC Med Res Methodol. 200857 |

| B21 | AIDS | 1998–2007 (IN/OUT; A) | B21–B24 | 50 | PPV =100 (92.9–100) | DS | Thygesen SK et al. BMC Med Res Methodol. 201158 |

| C00–D48: Neoplasms | |||||||

| C00–C75 | Any tumor | 1998–2007 (IN/OUT; A) | C00–C75 | 50 | PPV =98.0 (89.4–99.9) | DS | Thygesen SK et al. BMC Med Res Methodol. 201158 |

| 1977 (IN; A/B) | 140–239 (excl brain tumors and non-melanoma skin cancer) | 17,956 | PPV =91.7 (91.3–92.1); Se =75.8 (75.2–76.3) | DCR | Osterlind A et al. Ugeskr Laeger. 198559 | ||

| C18 | Colorectal cancer | 2001–2006 (IN/OUT;e A/Be) | C18–20 | 24,153 | PPV =88.9 (88.5–89.3); Se =93.4 (93.1–93.7) | DCR | Helqvist L et al. Eur J Cancer Care. 201260 |

| Colorectal cancer recurrences | 2001–2011 (IN/OUT/ED;e A/Be) | C76–C80, C18.9X, C20.9X, BWHA1–2, BOHJ17, BOHJ19B1 (algorithm combining metastasis and chemotherapy codes in the DNPR with cancer recurrence codes in the PD) | 70 | PPV =85.7 (75.7–92.1); NPV =99.0 (97.0–100); Se =95.2 (86.9–98.4); Sp =96.6 (93.8–98.1) | Actively followed cohort | Lash TL et al. Int J Cancer. 201461 | |

| C51–58 | Gynecological cancers | 1977–1988 (IN; A/Be) | 180, 182.0, 183 (among women undergoing gynecological surgery) | 614 | PPV =89.9 (87.3–92.0); Se =94.7 (92.6–96.2) | MR | Kjaergaard J et al. J Epidemiol Biostat. 200162 |

| C53 | Cervical cancer | 1977–1988 (IN; A/Be) | 180 (among women undergoing gynecological surgery) | 148 | PPV =88.5 (82.4–92.7); Se =94.2 (89.1–97.1) | MR | Kjaergaard J et al. J Epidemiol Biostat. 200162 |

| C54–55 | Uterus cancer | 1977–1988 (IN; A/Be) | 182.00–182.09 (among women undergoing gynecological surgery) | 261 | PPV =90.4 (86.2–93.4); Se =92.9 (89.1–95.5) | MR | Kjaergaard J et al. J Epidemiol Biostat. 200162 |

| C56 | Ovarian cancer | 1977–1988 (IN; A/Be) | 183 | 205 | PPV =90.2 (85.4–93.6); Se =97.4 (94.0–98.9) | MR | Kjaergaard J et al. J Epidemiol Biostat. 200162 |

| C61 | Prostate cancer | 1995–2012 (IN/OUT; A/B) | C61 | 240 | PPV =98.3 (95.8–99.4) | MR (histologically-/biopsy-verified) | Drljevic A et al. Clin Epidemiol 201463 |

| C64 | Urological cancer | 2004–2009 (IN/OUT; A/Be) | C64–68, D09.0–D09.1, D30.1–D30.9, D41.1–D41.9 | 41,129 | PPV =86.6 (86.3–86.9); Se =94.9 (94.7–95.2) | DCR | Gammelager H et al. Eur J Cancer Prev 201264 |

| C76–80 | Metastatic solid tumor | 1998–2007 (IN/OUT; A) | C76–C80 | 50 | PPV =100 (92.9–100) | DS | Thygesen SK et al. BMC Med Res Methodol. 201158 |

| C79.5 | Bone metastases or skeletal-related events in patients with prostate (P) or breast (B) cancer | 2000–2005 (n/a; n/a) | C79.5, BWGC1, M80.0, M84.4, M90.7, M43.9, 48.5, M54.5, M54.6, M54.9, G95.2, G95.8, KNAG (+ C61.9/C50) | 27 P; 15 B | PPVP =92.6 (76.6–97.9); NPVP =71.2 (60.0–80.4); PPVB =73.3 (48.1–89.1); NPVB =90.6 (82.5–95.2); SeP =54.4 (40.2–67.9); SpP =96.3 (87.5–99.0); SeB =57.9 (36.3–76.9); SpB =95.1 (88.0–98.1) | MR | Jensen AØ et al. Clin Epidemiol. 200965 |

| C79.5 | Bone metastases in patients with prostate cancer | 2005–2010 (IN/OUT;e A/Be) | C61 (from DCR) with prespecified PSA values, antiresorptive therapy, and bone scintigraphy, but without C77–C79 | 212 | PPVPSA >50 μg/L =9.6 (4.7–18.5) and NPVPSA <50 μg/L =98.6 (94.9–99.6) regardless of receipt of antiresorptive therapy or presence of bone scintigraphy | MR | Ehrenstein V et al. Clin Epidemiol. 201566 |

| C81.0–96.9 | Hematological cancer | 1994–1999 (IN;e Ae) | C81.0–C96.9 | 1,075 | PPV =84.5 (82.2–86.5); Se =91.5 (89.6–93.1) | DCR | Nørgaard M et al. Eur J Cancer Prev. 200567 |

| C81 | Lymphoma | 1998–2007 (IN/OUT; A) | C81–C85, C88, C90, C96 | 50 | PPV =100 (92.9–100) | DS | Thygesen SK et al. BMC Med Res Methodol. 201158 |

| C81 | Hodgkin’s disease | 1994–1999 (IN;e Ae) | C81.0–9 | 77 | PPV =71.4 (60.5–80.3); Se =88.7 (78.5–94.4) | DCR | Nørgaard M et al. Eur J Cancer Prev. 200567 |

| C82 | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 1994–1999 (IN;e Ae) | C82.0–85.9, C88.0–9, C91.1, C96.0–9 | 613 | PPV =85.3 (82.3–87.9); Se =88.2 (85.3–90.6) | DCR | Nørgaard M et al. Eur J Cancer Prev. 200567 |

| C90 | Multiple myeloma and other malignant plasma cell neoplasms | 1994–1999 (IN;e Ae) | C90.0–2 | 158 | PPV =82.3 (75.6–87.4); Se =90.9 (85.1–94.6) | DCR | Nørgaard M et al. Eur J Cancer Prev. 200567 |

| C91 | Leukemia | 1998–2007 (IN/OUT; A) | C91–C95 | 50 | PPV =100 (92.9–100) | DS | Thygesen SK et al. BMC Med Res Methodol. 201158 |

| C92 | Acute myeloid leukemia | 1994–1999 (IN;e Ae) | C92.0 | 108 | PPV =67.6 (58.3–75.7); Se =89.0 (80.4–94.1) | DCR | Nørgaard M et al. Eur J Cancer Prev. 200567 |

| D25 | Uterine fibroma | 1977–1988 (IN; A/B) | 218.99 (among women undergoing gynecological surgery) | 1,430 | PPV =92.9 (91.4–94.1); NPV =88.9 (87.8–89.9); Se =77.4 (75.4–79.4); Sp =96.8 (96.2–97.4) | DS | Kjaergaard J et al. J Clin Epidemiol. 200268 |

| D27 | Benign ovarian neoplasms | 1977–1988 (IN; A/B) | 220.99 (among women undergoing gynecological surgery) | 743 | PPV =78.2 (75.1–81.0); NPV =90.0 (89.1–90.9); Se =58.3 (55.2–61.3); Sp =95.9 (95.2–96.5) | DS | Kjaergaard J et al. J Clin Epidemiol. 200268 |

| D35.3 | Craniopharyngioma | 1985–2004 (IN/OUT;e A/Be) | 194.39, 226.21, 226.29, 253.99; D35.3, D44.4, C75.2 | 607 | PPV =30.5 (27.0–34.3); Se =95.2 (77.3–99.2) | MR (for PPV)/Se with ref to North Jutland County registry and registries of a Danish neuroendocrine center | Nielsen EH et al. J Clin Epidemiol. 201169 |

| D47.2 | Monoclonal gammopathy | 2001–2011 (IN/OUT;e A/Be) | D47.2 | 327 | PPV =82.3 (77.8–86.0); Se =16.8 (14.4–19.6) | MR (for PPV); Se with ref to Regional monoclonal gammopathy database | Gregersen H et al. Clin Epidemiol. 201370 |

| D50–D89: Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | |||||||

| D35.0A | Pheochromocytoma | 1977–1981 (IN; A/B) | 255.29 | 230 | PPV =19.1 (14.6–24.7) | MR | Andersen GS et al. Ugeskr Laeger. 198671 |

| D50.0 | Anemia caused by bleeding | 2000–2009 (IN/OUT; A/Be) | D50.0, D62.6 | 3,391 | PPV =95.4 (94.6–96.0) | LABKA | Zalfani J et al. Clin Epidemiol. 201272 |