Abstract

Exercise training influences phospholipid fatty acid composition in skeletal muscle and these changes are associated with physiological phenotypes; however, the molecular mechanism of this influence on compositional changes is poorly understood. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), a nuclear receptor coactivator, promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, the fiber-type switch to oxidative fibers, and angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Because exercise training induces these adaptations, together with increased PGC-1α, PGC-1α may contribute to the exercise-mediated change in phospholipid fatty acid composition. To determine the role of PGC-1α, we performed lipidomic analyses of skeletal muscle from genetically modified mice that overexpress PGC-1α in skeletal muscle or that carry KO alleles of PGC-1α. We found that PGC-1α affected lipid profiles in skeletal muscle and increased several phospholipid species in glycolytic muscle, namely phosphatidylcholine (PC) (18:0/22:6) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) (18:0/22:6). We also found that exercise training increased PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) in glycolytic muscle and that PGC-1α was required for these alterations. Because phospholipid fatty acid composition influences cell permeability and receptor stability at the cell membrane, these phospholipids may contribute to exercise training-mediated functional changes in the skeletal muscle.

Keywords: biochemical assays, fatty acid, lipidomics, mass spectrometry, molecular imaging, nuclear receptors, phospholipids/phosphatidylcholine, phospholipids/phosphatidylethanolamine, transcription factors, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α

Phospholipids are important structural components of membranes, and they influence a number of physical properties related to membrane function, including fluidity, permeability, and the anchoring of membrane-related proteins. Because altering dietary fatty acids (1–3) and exercise training (4–7) can both influence the composition of skeletal muscle membrane fatty acids, changes in phospholipid fatty acids may be involved in diet-induced or exercise training-induced physiological adaptation of the skeletal muscle. This effect on skeletal muscle adaptation may ultimately influence its function. Previous studies examined the effect of endurance training on the molecular species of skeletal muscle phospholipids. Exercise training increases phosphatidylcholine (PC) in muscle (8), and the effects of exercise on numerous phospholipid species in skeletal muscle have been examined in rats fed a standard chow diet (9) or a high-fat diet (10). With chow feeding, exercise training increased the abundance of two PC species (9): PC (16:0/18:1), the species also identified as an endogenous PPARα ligand in liver, and PC (16:0/18:2). In addition, exercise training with the normal chow diet enhanced the abundance of phosphatidic acid (PA) (16:0/18:2), PA (18:1/18:2), plasmenyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) (p-16:0/18:2), and phosphatidylinositol (PI) (18:0/22:5), and decreased the abundance of PE (18:0/22:6), PC (16:0/20:4), and PC (16:0/22:6) (9). With high-fat diet (10), exercise training also increased the abundance of PC (16:0/18:2), PA (18:1/18:2), and PE (p-16:0/18:2), and decreased the abundance of PE (18:0/22:6) and PC (16:0/22:6). High fat with exercise training also increased the abundance of isobaric PE (18:0/18:2) and PE (18:1/18:1) and decreased the abundance of PC (18:1/20:4), emphasizing the importance of diet in modulating the responses of skeletal muscle phospholipids to exercise. Recently, Goto-Inoue et al. (11) performed lipidomic analysis of skeletal muscle from mice subjected to chronic exercise training and high-fat diet using imaging MS (IMS) and TLC-Blot-MALDI-IMS. They found that PC (16:0/18:2), PC (18:0/22:6), and SM (d18:1/16:0) were chronic exercise training-induced lipids and, in contrast, PC (18:0/20:4) and SM (d18:1/24:1) were high-fat diet-induced lipids. The largest differences were also observed when comparing oxidative and glycolytic muscles, such as a decrease in plasmenyl-PE (16:0/20:4) and an increase in PE (18:0/22:6) in the oxidative muscle (9). Although evidence has shown that exercise training induces changes in skeletal muscle phospholipid species, it is not fully understood how exercise training induces these changes, or what roles these phospholipids play in the functional changes of exercise-trained skeletal muscle.

Exercise training stimulates physiological adaptation in skeletal muscle by affecting contractile activity (12, 13), mitochondrial function (14), metabolic regulation (15), intracellular signaling (16), and transcriptional responses (17, 18). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), identified as nuclear receptor coactivator, is expressed in brown adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, heart, kidney, and brain, and is markedly upregulated in brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle after acute exposure to cold stress (19). PGC-1α is induced in skeletal muscle by exercise (20–22) and controls many of the adaptations to physical activity. In particular, PGC-1α is activated in skeletal muscle by endurance-type activity and promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, angiogenesis, and a fiber-type switch to oxidative fibers (23, 24). Previously, we generated mice that overexpressed PGC-1α-b in skeletal muscle but not in heart (25, 26). PGC-1α-b, whose N terminus is different from that of PGC-1α-a protein, is the predominant PGC-1α isoform in skeletal muscles that is expressed in response to exercise (26). Overexpression of PGC-1α-b promoted fiber-type switch, mitochondrial biogenesis, and exercise capacity, increased the expression of fatty acid transporters, and enhanced angiogenesis and oxygen utilization kinetics in skeletal muscle (25, 27). Recently, we also found that PGC-1α-b induced branched chain amino acid metabolism, which might also be involved in endurance capacity (28). Because exercise training induces changes in skeletal muscle phospholipid species, it is possible that PGC-1α-b may be the underlying mechanism of induction. In this study, to understand how exercise training induces changes in phospholipid species, we performed lipidomics of skeletal muscle from genetically modified mice that overexpressed PGC-1α-b and mice that carry KO alleles of PGC-1α in skeletal muscle. We found that PGC-1α is involved in exercise training-induced changes in skeletal muscle phospholipid species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetically modified mice

The methods for generating transgenic mice overexpressing PGC-1α-b in skeletal muscle (PGC-1α-Tg mice) were described previously (26). The promoter for human α-skeletal actin, provided by Drs. E. C. Hardeman and K. L. Guven (Children’s Medical Research Institute, Australia) was used to express PGC-1α-b in skeletal muscle. The transgenic mice (heterozygotes, BDF 1 background) and WT C57BL6 mice were crossed and female 10–13-week-old offspring (heterozygote and WT, from the same litter) were used for the experiments. To generate skeletal muscle-specific PGC-1α KO mice (muscle PGC-1α-KO mice), we inactivated PGC-1α expression in skeletal muscles by crossing mice carrying a floxed PGC-1α allele with mice transgenic for the human α-skeletal actin promoter driven-Cre transgenic. PGC-1αflox/flox mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) (29, 30). Mice were maintained in a 12 h light/dark cycle at 22°C and were fed a normal chow diet ad libitum (CE-2; CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Mice were cared for in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and our institutional guidelines. All animal experiments were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Shizuoka (number 135024).

Voluntary exercise training

Male (9-week-old) muscle PGC-1α-KO mice and control PGC-1αflox/flox mice were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups: the sedentary control group or the training group. Mice assigned to training were housed individually in cages (22 × 9 × 8 cm) equipped with a running wheel (20 cm diameter; Shinano Co., Tokyo, Japan) for 5 weeks. The running wheel was equipped with a tachometer to determine the total running distance. Sedentary mice were housed in cages without a running wheel.

LC/MS

Lipids were extracted from the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and the soleus. Frozen muscle was homogenized and powdered in liquid nitrogen. Total lipids were extracted from homogenates with 1 ml chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v with 0.2 mg/ml butyl hydroxyl toluene) overnight. For targeted analysis of phospholipids, 0.05 mg/ml PC (17:0/17:0) was added to the chloroform/methanol for use as an internal standard. The lipid fractions were evaporated to dryness under vacuum. Samples were reconstituted in an equal volume of acetonitrile/isopropanol/water (65:30:5, v/v/v). Ten microliters of samples were injected onto the LC/MS system.

Lipidomic analysis was performed using a Q-ExactiveTM benchtop orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) equipped with an electrospray source ionization probe and an autosampler, Accela quaternary HPLC pump (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For LC analysis, an Acquity UPLC CSH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm; Waters, Milford, MA) was used. Mobile phase A consisted of water/acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) and mobile phase B consisted of isopropanol/acetonitrile (90:10, v/v). Both mobile phases, A and B, were supplemented with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid. The flow rate was 0.4 ml/min. The gradient was as follows: 10% B at 0 min, 10% B at 2 min, 50% B at 8 min, 75% B at 20 min, 90% B at 55 min, and 10% B at 60 min. For MS analysis, the spray voltage was set to 3.5 kV, the capillary temperature was set to 350°C, the S-lens radio frequency (RF) level was set to 50, and heater temperature was set to 300°C. The sheath gas flow rate was set to 40, and the auxiliary gas flow rate was set to 10. These conditions were applied to both positive and negative ionization modes. All samples were analyzed by both positive and negative ionization mode acquiring full scan MS, and the scan range was between m/z 120 and 1,200. To identify lipid species, m/z and retention time were used to obtain MS/MS data of the target peak by tandem mass spectrometric analysis. Using the LIPID MAPS online MS tool, the MS/MS data obtained were searched against a database of glycerophospholipid (http://www.lipidmaps.org/tools/ms/GP_prod_search.html) and glycerolipid (http://www.lipidmaps.org/tools/ms/GL_prod_search.html) precursor/product ions.

Targeted LC/MS/MS analysis was performed using an LCMS-8040 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) in positive ionization mode equipped with an electrospray source ionization probe, LC-30AD binary pump (Shimadzu), SIL-30AC auto sampler (Shimadzu), and CTO-20AC column oven (Shimadzu). For HPLC analysis, an Accucore RP-MS C18 column (2.6 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. The composition of the mobile phase and the flow rate were the same as above. The gradient was as follows: 40% B at 0 min, 40% B at 2 min, 52% B at 8 min, 60% B at 20 min, 100% B at 25 min, and 40% B at 30 min. For MS analysis, the nebulizer gas flow was set to 3.0 l/min, the drying gas flow was set to 15.0 l/min, the desolvation line temperature was set to 250°C, the heat block temperature was set to 400°C, and the collision-induced dissociation gas was set to 17 kPa. Target analysis of phospholipid species was operated in selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode. The details of the conditions for SRM for each phospholipid are shown in supplementary Table 1. The relative peak area for each species was normalized by the peak area of internal standard and muscle weight.

TLC analysis

For quantitative analysis of each lipid, we used conventional TLC. Briefly, total lipid extracts from each gastrocnemius dissolved in chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) were manually applied as 5 mm wide spots to silica gel 60 HPTLC plates (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The plates were developed with a solvent system consisting of methyl acetate/1-propanol/chloroform/methanol/0.25% aqueous potassium chloride (25:25:25:10:9, v/v/v/v/v) for phospholipids, whereas for neutral lipid separation, the developing solvent consisted of n-hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid (80:30:1, v/v/v). These chromatograms were sprayed with primuline reagent and lipid bands were visualized under UV light at 366 nm. The relative density of each band was quantified by Image J software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

IMS analysis

The localization of each lipid was analyzed by IMS. The developed TLC plates were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane by the TLC-blot method, as described previously (31), and transferred PVDF membranes were attached to the MALDI target plate for IMS analyses. For TLC-blot-imaging analyses, we used a QSTAR Elite high-performance hybrid quadrupole TOF mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The laser irradiated 500 times per position on the PVDF membrane. We set the spatial resolution to 400 μm. All analyses were performed in the positive ion mode within the mass ranges of m/z 400–1,200, with 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid at 50 mg/ml as a matrix. The ion images were constructed using BioMap software (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland).

The tissue blocks (gastrocnemius) were rapidly frozen in isopentane cooled by liquid nitrogen. Transverse cross-sections of 10 μm were made with a cryostat (Leica, CM1510; Germany) at −20°C. For positive-ion mode, 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid of 50 mg/ml in methanol/water (7:3, v/v) was uniformly sprayed over the muscle tissue sections with a 0.2 mm nozzle caliber airbrush (Procon Boy FWA Platinum; Mr. Hobby, Tokyo, Japan). We used a MALDI TOF/TOF-type instrument, the Ultraflex II (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA). The laser irradiated 200 times per position. All pixel sizes of imaging were 100 μm. The MS parameters were set to obtain the highest sensitivity with m/z values in the range of 400–1,000. The ion images were constructed using FlexImaging software (Bruker Daltonics). Normalization by total ion current was performed using the same software.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA preparation methods and quantitative (q)RT-PCR were performed as described previously (26). The mouse-specific primer pairs used are shown in supplementary Table 2.

Statistical analysis

For lipidomic analyses, the detected peaks were aligned according to the m/z value and normalized retention time using Signpost MS (Reifycs, Tokyo, Japan). After applying autoscaling, mean-centering, and scaling by standard deviation on a per-peak basis as pretreatment, a hierarchical clustering analysis and a principal component analysis (PCA) were conducted using JMP version 11 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). In hierarchical clustering analysis, the resulting data sets of each genotype were clustered using Euclidean distance with Ward’s method (32). The relative area value of each peak was calculated and used for the comparison between the PGC-1α-Tg and WT groups. In PCA, a score plot of the first and second principal components was generated. Statistical hypothesis testing of factor loading in PCA was performed to select species that had a statistically significant correlation to the principal component score. The P value was calculated as reported previously (33). A change trend was defined at P < 0.05. Furthermore, a Bonferroni adjustment was applied to determine the level of significance for multiple testing (the adjusted α = 0.05/97 = 0.000515 for retention time 14–29 min peaks and α = 0.05/80 = 0.000625 for retention time 30–41 min peaks).

Other data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. In case of significant differences, each group was compared with the other groups by a Student’s t-test (JMP, version 11). Values are shown as the mean ± SE.

RESULTS

Differences between lipid profiles of glycolytic and oxidative fiber and the impact of PGC-1α

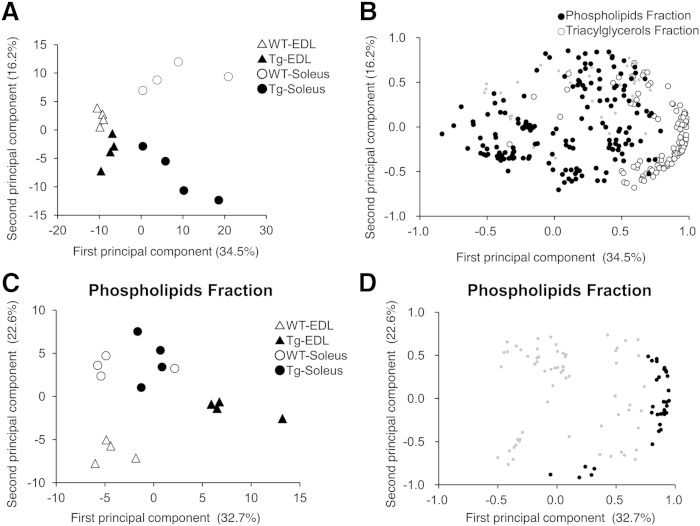

To examine the differences between the lipid profiles of glycolytic and oxidative muscle fibers such as EDL and soleus, and to determine the impact of PGC-1α on these profiles, lipidomic analyses were performed using high-resolution LC/MS that allows for accurate identification of lipid species. Figure 1A shows PCA scatter plots of the samples. The first principal component effectively and distinctly separated the mice based on muscle fiber type (x axis), and the second principal component separated the mice based on the genotype (y axis). The results suggested that overexpression of PGC-1α in the skeletal muscle caused a significant change in the overall lipid profiles of the muscle. However, the lipid profile of EDL from PGC-1α-Tg mice, which showed oxidative characteristics, was different from the profile of the originally oxidative muscle, such as the soleus. In the loading plot of this PCA (Fig. 1B), lipid species with chromatographic retention times between 14 and 29 min contributed to PGC-1α-driven alterations in the lipid profile. On the other hand, lipid species having chromatographic retention times between 30 and 41 min contributed to the differences in lipid profiles between the EDL and soleus. Because our preliminary study showed that the fractions having chromatographic retention times between 14 and 29 min contained many phospholipid species, this fraction was termed the phospholipid fraction. The fraction having chromatographic retention times between 30 and 41 min contained many TG species and was termed the TG fraction.

Fig. 1.

Changes in lipid profiles of the skeletal muscles overexpressing PGC-1α. A: Score plot of PCA for all detected peaks in lipid extracts from the skeletal muscles (EDL and soleus) of WT and PGC-1α-Tg (Tg) mice. B: Loading plot of PCA for all detected peaks in skeletal muscles (EDL and soleus) from WT and Tg mice. The peaks having chromatographic retention times between 14 and 29 min (phospholipid fraction) are highlighted in black closed circles and the peaks having retention times between 30 and 41 min (TG fraction) are highlighted in open circles. C: Score plot of PCA for lipid species in the phospholipid fraction of the skeletal muscles (EDL and soleus) from WT and Tg mice. D: Loading plot of PCA for lipid species in the phospholipid fraction of the skeletal muscles (EDL and soleus) from WT and Tg mice. Statistically significant species tested for factor loading (P < 0.000515) are highlighted in black closed circles.

To identify the lipid species that contribute to PGC-1α-driven changes in lipid profile, PCA was performed using lipid species in the phospholipid and TG fractions. In PCA of the phospholipid fraction, the first principal component separated the WT and PGC-1α-Tg mice (x axis), and the differences were obvious in EDL (Fig. 1C). Statistical hypothesis testing for factor loading in the first and second principal components was performed, and the lipid species that showed statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are shown in Fig. 1D and Table 1. The phospholipids, 12 PC and 6 PE, were identified as significant in the first principal component, and 3 PC and 1 SM were identified in the second principal component. In PCA of the TG fraction, the first principal component separated EDL and soleus, and the second principal component separated soleus from WT and PGC-1α-Tg mice (data not shown). Fifty-five TGs were detected as significant in statistical hypothesis testing for factor loading in the first principal component; however, none were found to be significant in the second principal component (Table 2). The results indicated that TG molecular species might not be major factors contributing to the alteration of lipid profile by PGC-1α.

TABLE 1.

PCA identification of lipid species in the phospholipid fraction

| Retention Time (min) | m/z | Lipid Species | Adduct Ion | Factor Loading | |

| First Principal Component | Second Principal Component | ||||

| 19.28 | 706.54 | PC (14:0/16:0) | [M+H]+ | 0.32 | −0.81a |

| 20.78 | 734.57 | PC (16:0/16:0) | [M+H]+ | 0.24 | −0.79a |

| 20.92 | 804.58 | PC (16:0/18:1) | [M+HCOO]− | 0.90a | −0.04 |

| 19.84 | 758.57 | PC (16:0/18:2) | [M+H]+ | 0.81a | −0.53 |

| 19.87 | 802.56 | PC (16:0/18:2) | [M+HCOO]− | 0.88a | −0.18 |

| 19.88 | 784.58 | PC (16:0/20:3) | [M+H]+ | 0.88a | −0.36 |

| 19.67 | 782.57 | PC (16:0/20:4) | [M+H]+ | 0.19 | −0.91a |

| 22.21 | 788.62 | PC (18:0/18:1) | [M+H]+ | 0.93a | 0.26 |

| 21.26 | 786.60 | PC (18:0/18:2) | [M+H]+ | 0.95a | −0.03 |

| 21.10 | 810.60 | PC (18:0/20:4) | [M+H]+ | 0.92a | −0.17 |

| 20.77 | 836.60 | PC (18:0/22:5) | [M+H]+ | 0.92a | 0.31 |

| 20.77 | 878.59 | PC (18:0/22:6) | [M+HCOO]− | 0.84a | 0.46 |

| 19.46 | 832.58 | PC (18:1/22:6) | [M+H]+ | 0.84a | 0.22 |

| 18.29 | 830.57 | PC (18:2/22:6) | [M+H]+ | 0.86a | 0.25 |

| 19.92 | 790.56 | PC (p-16:0/22:6) | [M+H]+ | 0.84a | 0.43 |

| 19.71 | 762.51 | PE (16:0/22:6) | [M+H]+ | 0.85a | −0.19 |

| 21.12 | 794.56 | PE (18:0/22:5) | [M+H]+ | 0.91a | 0.36 |

| 21.13 | 790.54 | PE (18:0/22:6) | [M-H]− | 0.91a | 0.34 |

| 21.12 | 792.55 | PE (18:0/22:6) | [M+H]+ | 0.94a | 0.09 |

| 19.83 | 788.52 | PE (18:1/22:6) | [M-H]− | 0.90a | −0.17 |

| 20.43 | 748.53 | PE (p-16:0/22:6) | [M+H]+ | 0.86a | −0.38 |

| 20.89 | 731.61 | SM (d18:1/18:0 or d18:0/18:1) | [M+H]+ | −0.05 | −0.88a |

P < 0.000515 after Bonferroni adjustment.

TABLE 2.

PCA identification of lipid species in the TG fraction

| Retention Time (min) | m/z | Lipid Species | Adduct Ion | Factor Loading | |

| First Principal Component | Second Principal Component | ||||

| 33.13 | 794.72 | TG (14:0/16:0/16:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.96a | −0.17 |

| 35.34 | 824.76 | TG (14:0/16:0/18:0) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.97a | 0.02 |

| 31.40 | 818.72 | TG (14:0/16:1/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.96a | −0.20 |

| 33.51 | 848.76 | TG (14:0/18:1/18:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.98a | −0.02 |

| 36.53 | 862.79 | TG (15:0/18:1/18:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.86a | −0.47 |

| 34.63 | 860.77 | TG (15:1/18:1/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.93a | −0.27 |

| 35.74 | 880.74 | TG (15:1/18:1/20:5) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.87a | 0.43 |

| 35.32 | 796.74 | TG (16:0/14:0/16:0) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.92a | −0.12 |

| 37.56 | 824.77 | TG (16:0/16:0/16:0) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.95a | 0.14 |

| 35.36 | 822.75 | TG (16:0/16:0/16:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.97a | 0.05 |

| 37.58 | 852.79 | TG (16:0/16:0/18:0) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.96a | 0.10 |

| 37.58 | 850.79 | TG (16:0/16:0/18:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.96a | 0.10 |

| 35.51 | 848.77 | TG (16:0/16:0/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.98a | 0.09 |

| 33.26 | 820.74 | TG (16:0/16:1/16:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.99a | −0.01 |

| 35.43 | 850.78 | TG (16:0/16:1/18:0) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.98a | 0.09 |

| 33.56 | 846.75 | TG (16:0/16:1/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.99a | 0.01 |

| 35.36 | 854.73 | TG (16:0/17:2/18:4) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.82a | 0.51 |

| 33.51 | 888.80 | TG (16:0/18:0/18:0) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.96a | 0.23 |

| 39.82 | 878.82 | TG (16:0/18:0/18:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.90a | −0.17 |

| 39.84 | 906.84 | TG (16:0/18:0/20:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.87a | −0.33 |

| 37.61 | 876.80 | TG (16:0/18:1/18:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.98a | 0.05 |

| 35.75 | 874.79 | TG (16:0/18:1/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.98a | 0.11 |

| 35.16 | 924.80 | TG (16:0/18:1/22:5) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.82a | −0.55 |

| 34.43 | 922.79 | TG (16:0/18:1/22:6) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.99a | −0.03 |

| 31.50 | 844.74 | TG (16:1/16:1/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.98a | −0.12 |

| 33.74 | 872.77 | TG (16:1/18:1/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 1.00a | 0.02 |

| 33.75 | 914.82 | TG (16:1/18:1/20:5) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.94a | 0.33 |

| 32.20 | 924.79 | TG (16:1/18:1/22:4) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.97a | −0.04 |

| 31.84 | 870.75 | TG (16:1/18:2/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.99a | −0.11 |

| 30.34 | 868.74 | TG (16:1/18:2/18:3) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.84a | −0.45 |

| 35.38 | 890.82 | TG (17:0/18:1/18:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.92a | 0.30 |

| 34.74 | 886.79 | TG (17:1/18:1/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.84a | −0.48 |

| 35.86 | 906.76 | TG (17:2/18:1/20:5) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.92a | 0.36 |

| 37.66 | 904.82 | TG (18:0/18:1/18:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.99a | 0.07 |

| 35.81 | 902.81 | TG (18:0/18:1/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.98a | 0.17 |

| 37.87 | 930.84 | TG (18:0/18:2/20:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.98a | 0.10 |

| 37.67 | 902.82 | TG (18:1/18:1/18:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.99a | 0.04 |

| 35.81 | 900.80 | TG (18:1/18:1/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.99a | 0.10 |

| 37.61 | 918.85 | TG (18:1/18:1/19:0) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.92a | 0.34 |

| 39.80 | 930.85 | TG (18:1/18:1/20:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.79a | −0.56 |

| 35.92 | 928.83 | TG (18:1/18:1/20:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.93a | 0.32 |

| 36.08 | 926.82 | TG (18:1/18:1/20:3) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.96a | −0.21 |

| 34.41 | 950.81 | TG (18:1/18:1/22:5) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.88a | −0.17 |

| 34.46 | 948.80 | TG (18:1/18:1/22:6) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.98a | −0.09 |

| 34.00 | 898.79 | TG (18:1/18:2/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 1.00a | 0.02 |

| 35.70 | 916.83 | TG (18:1/18:2/19:0) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.89a | 0.42 |

| 37.95 | 928.83 | TG (18:1/18:2/20:1) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.97a | −0.08 |

| 33.42 | 922.78 | TG (18:1/18:2/20:4) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.98a | −0.09 |

| 37.73 | 944.86 | TG (18:1/18:2/21:0) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.96a | 0.15 |

| 32.64 | 946.79 | TG (18:1/18:2/22:6) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.99a | −0.02 |

| 32.53 | 920.77 | TG (18:2/16:0/22:6) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.89a | −0.41 |

| 32.22 | 896.77 | TG (18:2/18:2/18:2) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.99a | −0.10 |

| 30.67 | 894.75 | TG (18:2/18:2/18:3) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.92a | −0.32 |

| 30.88 | 944.77 | TG (18:2/18:2/22:6) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.87a | −0.35 |

| 34.04 | 940.83 | TG (18:2/20:5/20:5) | [M+NH4]+ | 0.95a | 0.29 |

P < 0.000625 after Bonferroni adjustment.

Targeted analysis of phospholipids altered by PGC-1α overexpression

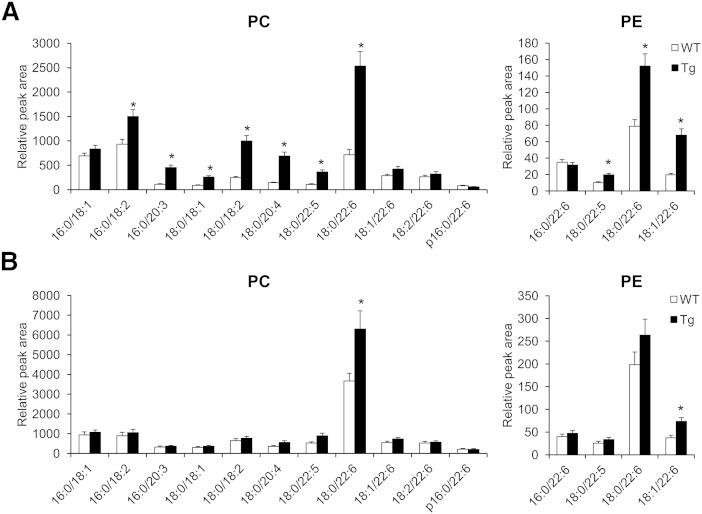

To measure the relative amount of phospholipids altered by PGC-1α overexpression in EDL and soleus, 11 PC and 5 PE, identified as significant in the first principal component, were quantitatively measured by SRM using quadrupole MS (Fig. 2). PE (p-16:0/22:6) was not determined in these samples. In EDL, 3.5- and 1.9-fold increases were observed in PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) by overexpressing PGC-1α. PC (16:0/18:2), PC (16:0/20:3), PC (18:0/18:1), PC (18:0/18:2), PC (18:0/20:4), PC (18:0/22:5), PE (18:0/22:5), and PE (18:1/22:6) also significantly increased in EDL from PGC-1α-Tg mice. In soleus, the amounts of PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) were relatively higher, and increases of PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:1/22:6) were observed by overexpressing PGC-1α.

Fig. 2.

Target analysis of phospholipids in the skeletal muscle altered by overexpression of PGC-1α. The levels of targeted phospholipids in EDL (A) and soleus (B) from WT and PGC-1α-Tg (Tg) mice analyzed in SRM mode. Values are mean ± SE (n = 4–5). *P < 0.05 (WT vs. Tg).

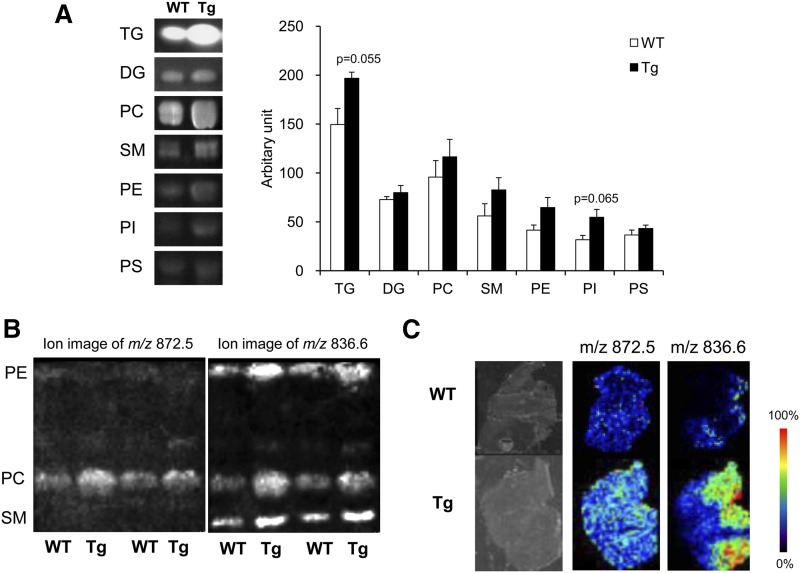

Lipid analyses by TLC and determination of PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) by TLC-blot-MALDI-IMS and IMS-based histological examination

Changes in the lipid composition of muscle might be due to an increase in membrane fraction, such as plasma membrane and mitochondrial membrane, because PGC-1α stimulated mitochondrial biogenesis. To determine whether the total amounts of PC and PE were altered by PGC-1α overexpression, lipids extracted from gastrocnemius of WT and PGC-1α-Tg mice were separated by TLC (Fig. 3A). TG increased in the muscle from PGC-1α-Tg mice (P = 0.055), but diacylglycerol (DG) content did not. In addition to PC and PE, SM, PI, and phosphatidylserine (PS) were detected with phospholipid separation. The amount of PI was slightly higher in the muscle from PGC-1α-Tg mice (P = 0.065); whereas, there were no significant differences between the genotypes in any other phospholipid classes.

Fig. 3.

TLC and IMS analyses. A: TLC analysis. The visible TLC bands indicate the amounts of TG, DG, PC, SM, PE, PI, and PS in skeletal muscle from WT and PGC-1α-Tg (Tg) mice (n = 3). P values are shown when P < 0.1. B: TLC-blot-MALDI-IMS analysis. The ion image of m/z 872.5 represents the amount of PC (18:0/22:6) and the image of m/z 836.6 at PE position represents the amount of PE (18:0/22:6). C: IMS-based histological examination. Tissue sections from gastrocnemius muscle from WT and Tg mice are shown. Molecular image of m/z 872.5 represents the amount and the distribution of PC (18:0/22:6) and the image of m/z 836.6 possibly represents the amount and the distribution of PE (18:0/22:6).

TLC-blot-MALDI-IMS was used to determine the quantities of PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) in the bands generated by TLC analysis. In the previous TLC-blot-MALDI-IMS, PC (18:0/22:6) was detected as [M+K]+ having an m/z of 872.5 (34) and PE (18:0/22:6) was detected as [M+2Na-H]+ having an m/z of 836.6 (35). As shown in Fig. 3B, the ion signals of m/z 872.5 were only detected at the PC positions and the signals increased in PGC-1α-Tg mice. On the other hand, the ion signals of m/z 836.6 were detected at the PE, PC, and SM positions, and these all increased in the PGC-1α-Tg mice. As in the quantitative LC/MS analyses, the amounts of PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) increased in muscle overexpressing PGC-1α, suggesting that alteration of PC and PE composition may not be due to an increase in the total amount of PC and PE, but to the change in specific molecular species.

IMS-based histological examinations were performed to determine the ion signals of m/z 872.5 and 836.6 (Fig. 3C). The signals corresponding to m/z 872.5 and 836.6 were stronger in the muscle from PGC-1α-Tg mice than from WT mice. From the ion images, distribution of PC (18:0/22:6) increased ubiquitously in the gastrocnemius by PGC-1α overexpression. The distribution of m/z 836.6, possibly including PE (18:0/22:6), also increased in the muscle of PGC-1α-Tg mice.

Exercise training-induced changes in lipid profiles and the role of PGC-1α

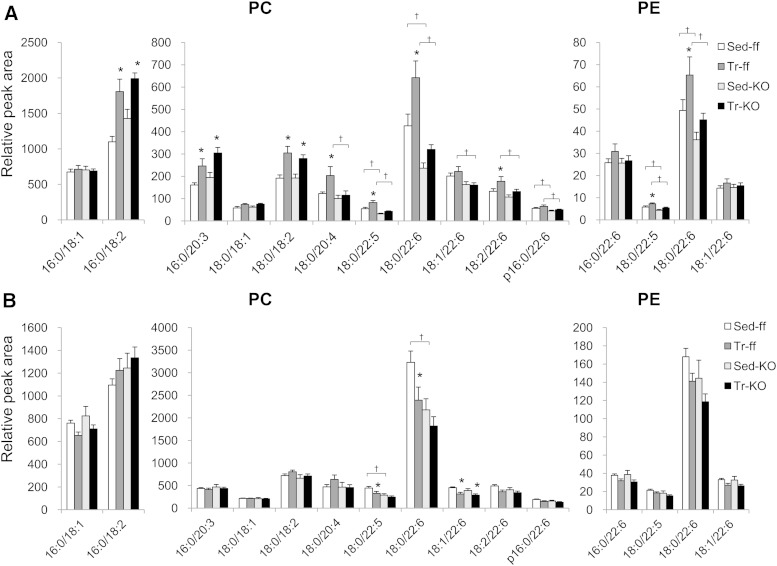

PGC-1α altered lipid profiles in skeletal muscles. Notably, several PC and PE species significantly increased in EDL overexpressing PGC-1α, as shown in Fig. 2. To determine whether exercise training-induced changes in the PC and PE profiles were similar to those observed in PGC-1α-Tg mice, and whether PGC-1α was involved in these changes, the amounts of PC and PE species in sedentary and trained muscle were measured in muscle PGC-1α-KO mice and control PGC-1αflox/flox mice. Expression of PGC-1α mRNA was not detected in muscle of PGC-1α-KO mice (supplementary Fig. 1). The averages of the daily running distances were 6.8 ± 0.6 km/day and 6.4 ± 0.5 km/day in PGC-1αflox/flox mice and muscle PGC-1α-KO mice, respectively (P = 0.7704). As shown in Fig. 4, PC (18:0/20:4), PC (18:0/22:5), PC (18:0/22:6), PC (18:2/22:6), PE (18:0/22:5), and PE (18:0/22:6) increased in trained EDL of PGC-1αflox/flox mice. However, these lipid species did not increase in trained EDL of muscle PGC-1α-KO mice, suggesting that exercise training-induced increases in these molecules were dependent on PGC-1α. PC (16:0/18:2), PC (16:0/20:3), and PC (18:0/18:2) increased in trained EDL, not only from the PGC-1αflox/flox mice, but also from the muscle PGC-1α-KO mice, suggesting that exercise training-induced changes of these lipid species did not involve PGC-1α. In soleus, exercise-induced increases were not observed in either group of mice.

Fig. 4.

PGC-1α involvement in exercise training-induced changes in targeted skeletal muscle phospholipids. Muscle PGC-1α-KO mice (KO) and control PGC-1αfl/fl mice (ff) were assigned to one of two experimental groups: sedentary control (Sed) and training groups (Tr). Mice assigned to the Tr group were housed individually in cages equipped with a running wheel for 5 weeks. The levels of targeted phospholipids in EDL (A) and soleus (B) from muscle PGC-1α-KO mice (KO) and control PGC-1αfl/fl mice (ff) analyzed in SRM mode. Values are mean ± SE (n = 9–15). *P < 0.05 (Sed vs. Tr); †P < 0.05 (ff vs. KO).

PGC-1α-mediated changes in acyltransferase expression in the skeletal muscle

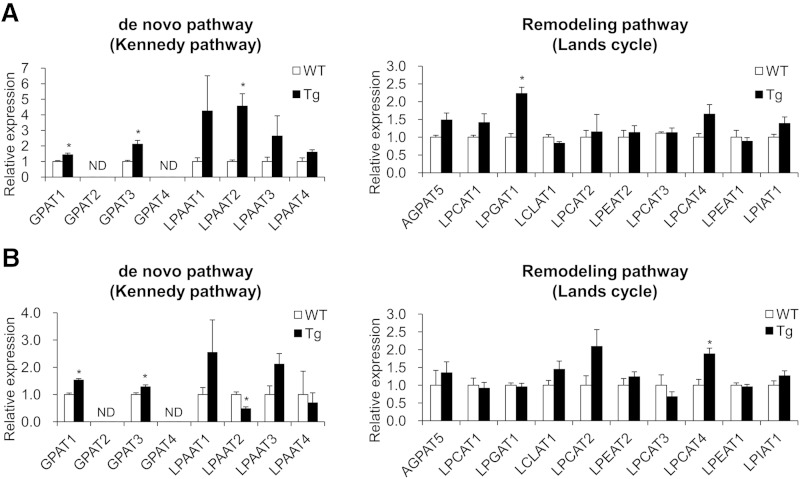

Because glycerophospholipids and TG are formed by de novo synthesis in the Kennedy pathway, and because the former are modified by the Lands cycle remodeling pathway using acyl-CoAs as donors (supplementary Fig. 2) (36), PGC-1α-mediated changes in skeletal muscle lipid profiles may be caused by changes in the expression of acyltransferases involved in the Kennedy pathway or the Lands cycle. To test this possibility, we measured the expression of glycerophosphate acyltransferase (GPAT) and lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase (LPAAT), which are components of the Kennedy pathway, and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase (LPCAT), lysophosphatidylglycerol acyltransferase, lysocardiolipin acyltransferase, lysophosphatidylethanolamine acyltransferase (LPEAT), lysophosphatidylinositol acyltransferase, and acyl glycerophosphate acyltransferase (AGPAT), which are components of the Lands cycle, using qRT-PCR (Fig. 5). Although the expressions of GPAT1, GPAT3, LPAAT2, and lysophosphatidylglycerol acyltransferase 1 in EDL and GPAT1, GPAT3, and LPCAT4 in soleus significantly increased in the muscle overexpressing PGC-1α, the expressions of the genes involved in PC and PE remodeling, AGPAT5, LPCAT, and LPEAT did not change in EDL, suggesting that PGC-1α-mediated increase in PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) in EDL cannot be explained by the expression of these genes.

Fig. 5.

Acyltransferase gene expression in the skeletal muscle overexpressing PGC-1α. Results of qRT-PCR analysis of acyltransferase expression in EDL (A) and soleus (B) from WT and PGC-1α-Tg (Tg) mice. Values are mean ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.05 (WT vs. Tg). ND, not detected.

DISCUSSION

It has been reported that exercise training modifies phospholipid species in the skeletal muscles (4–11); however, the molecular mechanisms involved in these modifications have remained unclear. In the present study, we found that overexpression of PGC-1α and exercise training altered phospholipid profiles in skeletal muscle, especially in glycolytic fiber, and some exercise-induced changes were required for PGC-1α expression. PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) were the typical phospholipid species affected by exercise training-induced PGC-1α expression in glycolytic fiber. On the other hand, several PC species, such as PC (16:0/18:2), PC (16:0/20:3), and PC (18:0/18:2), increased in exercise-trained skeletal muscle irrespective of PGC-1α expression, like the previously recognized changes in mitochondrial enzymes with training in the PCG-1α mice (37).

Previously, exercise training has been shown to increase in proportion to docosahexaenoic acid [22:6 (n-3)] in human skeletal muscle phospholipids (4, 7). For example, Andersson et al. (4) demonstrated that both the distribution of type I fibers in the skeletal muscle and the estimated physical activity level of humans were positively correlated with the percentage of docosahexaenoic acid [22:6 (n-3)], suggesting a relation between the proportion of docosahexaenoic acid [22:6 (n-3)] in human skeletal muscle phospholipids and the increase in endurance capacity with fiber type switch from glycolytic to oxidative. In the rat skeletal muscle, exercise increased the amount of PC (18:0/22:6) in EDL (11), and the content of PE (18:0/22:6) was much higher in red vastus lateralis than in white vastus lateralis (9). In the present study, we found that among phospholipids containing 22:6 fatty acids, PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) were increased by exercise training and overexpression of PGC-1α in the skeletal muscle. Furthermore, muscle PGC-1α was required for exercise-induced increase in PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) in EDL. These results suggested that exercise training-induced expression of PGC-1α changed the muscle fiber type from glycolytic to oxidative concomitantly with increase in PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6). In soleus, the involvement of PGC-1α in these changes was not observed, probably because soleus originally has characteristics of red muscle.

Both the Kennedy pathway and the Lands cycle contribute to the fatty acid composition of glycerophospholipids (supplementary Fig. 2) (38, 39). The Kennedy pathway begins with the stepwise acylation of glycerol-3-phosphate, which is catalyzed by two acyltransferases, GPAT and LPAAT, and leads to the formation of PA. PA is subsequently dephosphorylated to generate DG. The transfer of phosphocholine from cytidine diphosphate-choline to DG is a final step in the synthesis of PC. TG is also synthesized through acylation of DG. These acyltransferases have substrate specificity because saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids are normally found at sn-1, whereas polyunsaturated fatty acids are enriched at sn-2 of glycerolipids. GPAT1 prefers 16:0-CoA as a substrate (40), and GPAT3 and GPAT4 recognize a broad range of substrates, from 12:0-CoA to 18:1- or 18:2-CoA (41, 42). LPAAT1 has high activities with 14:0-, 16:0-, and 18:2-CoAs, and intermediate activities with 18:1- and 20:4-CoAs (43). LPAAT2 prefers 20:4-CoA over 16:0- or 18:0-CoA (43, 44). Two acyltransferases in the Kennedy pathway, LPAAT3 and LPAAT4, prefer 22:6-CoA as a substrate (45, 46). However, it is difficult to explain the PGC-1α-driven alteration of PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) content in muscle by these acyltransferases because expression of LPAAT3 and LPAAT4 was not induced by overexpression of PGC-1α. Furthermore, although PGC-1α-mediated increase in TG might occur if the Kennedy pathway is involved in the alteration of PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) content, we found no evidence from PCA to support the contribution of TG carrying 22:6 fatty acid moiety to the difference in the muscle from WT and PGC-1α-Tg mice (Table 2). These results suggest that the Kennedy pathway may not be involved in PGC-1α-mediated changes of PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) content in the muscle.

In addition to the acyl-CoA selectivity of GPAT and LPAAT, the Lands cycle is also involved in fatty acid diversity of glycerophospholipids. The Lands cycle provides a route for acyl remodeling to alter fatty acid composition at sn-2 of glycerophospholipids derived from the Kennedy pathway through the concerted actions of phospholipase A2 and lysophospholipid acyltransferase (LPLAT). Recently, several LPLATs were discovered and the substrate specificity was uncovered (36). For example, LPCAT3 showed higher activities with polyunsaturated fatty acyl-CoAs, 20:4-CoA and 18:2-CoA, than with saturated fatty acyl-CoA; whereas LPCAT4 and LPEAT1 had a clear preference for 18:1-CoA (47). These substrate preferences of LPLATs may explain the diversity in membrane glycerophospholipids, which vary among tissues and can change in response to external stimuli. However, the acyltransferases, which prefer 22:6-CoA as a substrate, have not been discovered in the Lands cycle. In the present study, measurements of LPLAT expression using qRT-PCR did not explain the changes of PC (18:0/22:6) and PE (18:0/22:6) content in the muscle. Further studies are required to determine the mechanisms of PGC-1α-mediated modification of the phospholipid profile in skeletal muscle.

In skeletal muscle, several studies have shown the relation between phospholipid species and physiological or pathophysiological phenotypes. For instance, a higher proportion of total n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, particularly docosahexaenoic acid [22:6 (n-3)], in skeletal muscle phospholipids has been associated with a lower fasting plasma glucose level in young children (48) and higher insulin action in rats (49). Docosahexaenoic acid [22:6 (n-3)] may have another function after being released from membrane glycerophospholipids by phospholipase A2, because D series resolvins and protectins derived from docosahexaenoic acid [22:6 (n-3)] have anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory properties (50–54). Recently, protectin DX, also derived from docosahexaenoic acid [22:6 (n-3)], was reported to stimulate the release of the prototypic myokine, interleukin-6, from skeletal muscle and thereby initiated a myokine-liver signaling axis, which blunted hepatic glucose production (55). Protectin DX also activates AMP-activated protein kinase (55), which stimulates glucose and lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle. From these facts, some of the health benefits of exercise training may be explained by PGC-1α-mediated alteration of skeletal muscle phospholipid profiles. On the other hand, a decrease in docosahexaenoic acid [22:6 (n-3)] from the skeletal muscle phospholipid fraction was observed in dystrophic mdx mice (56), and PGC-1α ameliorates muscular dystrophy in mdx mice (57). Although docosahexaenoic acid [22:6 (n-3)] has not been analyzed in the phospholipid fraction of dystrophic mdx mice overexpressing PGC-1α, it is likely that PGC-1α influences muscular dystrophy by altering phospholipid composition.

PGC-1α regulates several exercise-associated aspects of muscle function. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate the involvement of PGC-1α in the exercise-induced rearrangement of phospholipid molecular species in skeletal muscle. Our finding suggests that exercise-mediated increase in PGC-1α expression alters phospholipid profiles, and that these alterations may be one of the adaptive changes of skeletal muscle in response to endurance training. Although further studies are required, the alteration of the phospholipid profile may contribute to the endurance capacity of skeletal muscle and may partly explain the beneficial effects of exercise training.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Mr. Tomoki Sato, Mr. Yuta Nagaike, Ms. Yuri Nishimura, Ms. Eri Kobayashi, Ms. Mizuki Inoue, and Ms. Ayaka Takeuchi (University of Shizuoka) for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AGPAT

- acyl glycerophosphate acyltransferase

- DG

- diacylglycerol

- EDL

- extensor digitorum longus

- GPAT

- glycerophosphate acyltransferase

- IMS

- imaging MS

- LPAAT

- lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase

- LPCAT

- lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase

- LPEAT

- lysophosphatidylethanolamine acyltransferase

- LPLAT

- lysophospholipid acyltransferase

- PA

- phosphatidic acid

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PCA

- principal component analysis

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- PGC-1α

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α

- PI

- phosphatidylinositol

- PS

- phosphatidylserine

- PVDF

- polyvinylidene difluoride

- SRM

- selected reaction monitoring

- Tg

- transgenic

This study was supported by the Council for Science, Technology, and Innovation (CSTI), Cross-ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion program (SIP, number 14533567); “Technologies for creating next-generation agriculture, forestry, and fisheries” (funding agency: Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution, National Agriculture and Food Research Organization, NARO); and the Tojuro Iijima Foundation for Food Science and Technology (Chiba, Japan). This study was also supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI, numbers 26282184, 26560400, 25116712, and 21300240) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT, Tokyo), the Uehara Memorial Foundation (Tokyo, Japan), the Kao Research Council for the Study of Healthcare Science (Tokyo, Japan, number A-31006), and a University of Shizuoka Grant for Scientific and Educational Research.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson A., Nalsen C., Tengblad S., and Vessby B.. 2002. Fatty acid composition of skeletal muscle reflects dietary fat composition in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 76: 1222–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayre K. J., and Hulbert A. J.. 1996. Dietary fatty acid profile influences the composition of skeletal muscle phospholipids in rats. J. Nutr. 126: 653–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan D. A., and Storlien L. H.. 1993. Dietary lipid profile is a determinant of tissue phospholipid fatty acid composition and rate of weight gain in rats. J. Nutr. 123: 512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson A., Sjodin A., Hedman A., Olsson R., and Vessby B.. 2000. Fatty acid profile of skeletal muscle phospholipids in trained and untrained young men. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 279: E744–E751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson A., Sjodin A., Olsson R., and Vessby B.. 1998. Effects of physical exercise on phospholipid fatty acid composition in skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 274: E432–E438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helge J. W., Ayre K. J., Hulbert A. J., Kiens B., and Storlien L. H.. 1999. Regular exercise modulates muscle membrane phospholipid profile in rats. J. Nutr. 129: 1636–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helge J. W., Wu B. J., Willer M., Daugaard J. R., Storlien L. H., and Kiens B.. 2001. Training affects muscle phospholipid fatty acid composition in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 90: 670–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan T. E., Short F. A., and Cobb L. A.. 1969. Effect of long-term exercise on skeletal muscle lipid composition. Am. J. Physiol. 216: 82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell T. W., Turner N., Hulbert A. J., Else P. L., Hawley J. A., Lee J. S., Bruce C. R., and Blanksby S. J.. 2004. Exercise alters the profile of phospholipid molecular species in rat skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 97: 1823–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell T. W., Turner N., Else P. L., Hulbert A. J., Hawley J. A., Lee J. S., Bruce C. R., and Blanksby S. J.. 2010. The effect of exercise on the skeletal muscle phospholipidome of rats fed a high-fat diet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 11: 3954–3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goto-Inoue N., Yamada K., Inagaki A., Furuichi Y., Ogino S., Manabe Y., Setou M., and Fujii N. L.. 2013. Lipidomics analysis revealed the phospholipid compositional changes in muscle by chronic exercise and high-fat diet. Sci. Rep. 3: 3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flück M., and Hoppeler H.. 2003. Molecular basis of skeletal muscle plasticity–from gene to form and function. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 146: 159–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffey V. G., and Hawley J. A.. 2007. The molecular bases of training adaptation. Sports Med. 37: 737–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spina R. J., Chi M. M., Hopkins M. G., Nemeth P. M., Lowry O. H., and Holloszy J. O.. 1996. Mitochondrial enzymes increase in muscle in response to 7-10 days of cycle exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 80: 2250–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green H. J., Helyar R., Ball-Burnett M., Kowalchuk N., Symon S., and Farrance B.. 1992. Metabolic adaptations to training precede changes in muscle mitochondrial capacity. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 72: 484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benziane B., Burton T. J., Scanlan B., Galuska D., Canny B. J., Chibalin A. V., Zierath J. R., and Stepto N. K.. 2008. Divergent cell signaling after short-term intensified endurance training in human skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 295: E1427–E1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilegaard H., Saltin B., and Neufer P. D.. 2003. Exercise induces transient transcriptional activation of the PGC-1alpha gene in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 546: 851–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrès R., Yan J., Egan B., Treebak J. T., Rasmussen M., Fritz T., Caidahl K., Krook A., O’Gorman D. J., and Zierath J. R.. 2012. Acute exercise remodels promoter methylation in human skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 15: 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Z., Puigserver P., Andersson U., Zhang C., Adelmant G., Mootha V., Troy A., Cinti S., Lowell B., Scarpulla R. C., et al. 1999. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 98: 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goto M., Terada S., Kato M., Katoh M., Yokozeki T., Tabata I., and Shimokawa T.. 2000. cDNA Cloning and mRNA analysis of PGC-1 in epitrochlearis muscle in swimming-exercised rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 274: 350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miura S., Kawanaka K., Kai Y., Tamura M., Goto M., Shiuchi T., Minokoshi Y., and Ezaki O.. 2007. An increase in murine skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha) mRNA in response to exercise is mediated by beta-adrenergic receptor activation. Endocrinology. 148: 3441–3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baar K., Wende A. R., Jones T. E., Marison M., Nolte L. A., Chen M., Kelly D. P., and Holloszy J. O.. 2002. Adaptations of skeletal muscle to exercise: rapid increase in the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. FASEB J. 16: 1879–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puigserver P., Wu Z., Park C. W., Graves R., Wright M., and Spiegelman B. M.. 1998. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 92: 829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chinsomboon J., Ruas J., Gupta R. K., Thom R., Shoag J., Rowe G. C., Sawada N., Raghuram S., and Arany Z.. 2009. The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha mediates exercise-induced angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106: 21401–21406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tadaishi M., Miura S., Kai Y., Kano Y., Oishi Y., and Ezaki O.. 2011. Skeletal muscle-specific expression of PGC-1alpha-b, an exercise-responsive isoform, increases exercise capacity and peak oxygen uptake. PLoS One. 6: e28290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miura S., Kai Y., Kamei Y., and Ezaki O.. 2008. Isoform-specific increases in murine skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha) mRNA in response to beta2-adrenergic receptor activation and exercise. Endocrinology. 149: 4527–4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kano Y., Miura S., Eshima H., Ezaki O., and Poole D. C.. 2014. The effects of PGC-1alpha on control of microvascular P(O2) kinetics following onset of muscle contractions. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 117: 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatazawa Y., Tadaishi M., Nagaike Y., Morita A., Ogawa Y., Ezaki O., Takai-Igarashi T., Kitaura Y., Shimomura Y., Kamei Y., et al. 2014. PGC-1alpha-mediated branched-chain amino acid metabolism in the skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 9: e91006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Handschin C., Choi C. S., Chin S., Kim S., Kawamori D., Kurpad A. J., Neubauer N., Hu J., Mootha V. K., Kim Y. B., et al. 2007. Abnormal glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle-specific PGC-1alpha knockout mice reveals skeletal muscle-pancreatic beta cell crosstalk. J. Clin. Invest. 117: 3463–3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawada N., Jiang A., Takizawa F., Safdar A., Manika A., Tesmenitsky Y., Kang K. T., Bischoff J., Kalwa H., Sartoretto J. L., et al. 2014. Endothelial PGC-1alpha mediates vascular dysfunction in diabetes. Cell Metab. 19: 246–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goto-Inoue N., Hayasaka T., Taki T., Gonzalez T. V., and Setou M.. 2009. A new lipidomics approach by thin-layer chromatography-blot-matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization imaging mass spectrometry for analyzing detailed patterns of phospholipid molecular species. J. Chromatogr. A. 1216: 7096–7101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward J. H. 1963. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58: 236–244. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto H., Fujimori T., Sato H., Ishikawa G., Kami K., and Ohashi Y.. 2014. Statistical hypothesis testing of factor loading in principal component analysis and its application to metabolite set enrichment analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 15: 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayasaka T., Goto-Inoue N., Sugiura Y., Zaima N., Nakanishi H., Ohishi K., Nakanishi S., Naito T., Taguchi R., and Setou M.. 2008. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization quadrupole ion trap time-of-flight (MALDI-QIT-TOF)-based imaging mass spectrometry reveals a layered distribution of phospholipid molecular species in the mouse retina. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 22: 3415–3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaima N., Goto-Inoue N., Adachi K., and Setou M.. 2011. Selective analysis of lipids by thin-layer chromatography blot matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization imaging mass spectrometry. J. Oleo Sci. 60: 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shindou H., and Shimizu T.. 2009. Acyl-CoA:lysophospholipid acyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leick L., Wojtaszewski J. F., Johansen S. T., Kiilerich K., Comes G., Hellsten Y., Hidalgo J., and Pilegaard H.. 2008. PGC-1alpha is not mandatory for exercise- and training-induced adaptive gene responses in mouse skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 294: E463–E474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kennedy E. P. 1961. Biosynthesis of complex lipids. Fed. Proc. 20: 934–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lands W. E. 1958. Metabolism of glycerolipides; a comparison of lecithin and triglyceride synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 231: 883–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coleman R. A., and Lee D. P.. 2004. Enzymes of triacylglycerol synthesis and their regulation. Prog. Lipid Res. 43: 134–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao J., Li J. L., Li D., Tobin J. F., and Gimeno R. E.. 2006. Molecular identification of microsomal acyl-CoA:glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, a key enzyme in de novo triacylglycerol synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103: 19695–19700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y. Q., Kuo M. S., Li S., Bui H. H., Peake D. A., Sanders P. E., Thibodeaux S. J., Chu S., Qian Y. W., Zhao Y., et al. 2008. AGPAT6 is a novel microsomal glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 10048–10057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hollenback D., Bonham L., Law L., Rossnagle E., Romero L., Carew H., Tompkins C. K., Leung D. W., Singer J. W., and White T.. 2006. Substrate specificity of lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase beta - evidence from membrane and whole cell assays. J. Lipid Res. 47: 593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eberhardt C., Gray P. W., and Tjoelker L. W.. 1997. Human lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase. cDNA cloning, expression, and localization to chromosome 9q34.3. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 20299–20305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koeberle A., Shindou H., Harayama T., Yuki K., and Shimizu T.. 2012. Polyunsaturated fatty acids are incorporated into maturating male mouse germ cells by lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase 3. FASEB J. 26: 169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eto M., Shindou H., and Shimizu T.. 2014. A novel lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase enzyme (LPAAT4) with a possible role for incorporating docosahexaenoic acid into brain glycerophospholipids. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 443: 718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hishikawa D., Shindou H., Kobayashi S., Nakanishi H., Taguchi R., and Shimizu T.. 2008. Discovery of a lysophospholipid acyltransferase family essential for membrane asymmetry and diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105: 2830–2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baur L. A., O’Connor J., Pan D. A., Kriketos A. D., and Storlien L. H.. 1998. The fatty acid composition of skeletal muscle membrane phospholipid: its relationship with the type of feeding and plasma glucose levels in young children. Metabolism. 47: 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Storlien L. H., Jenkins A. B., Chisholm D. J., Pascoe W. S., Khouri S., and Kraegen E. W.. 1991. Influence of dietary fat composition on development of insulin resistance in rats. Relationship to muscle triglyceride and omega-3 fatty acids in muscle phospholipid. Diabetes. 40: 280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.VanRollins M., and Murphy R. C.. 1984. Autooxidation of docosahexaenoic acid: analysis of ten isomers of hydroxydocosahexaenoate. J. Lipid Res. 25: 507–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mukherjee P. K., Marcheselli V. L., Serhan C. N., and Bazan N. G.. 2004. Neuroprotectin D1: a docosahexaenoic acid-derived docosatriene protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101: 8491–8496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marcheselli V. L., Hong S., Lukiw W. J., Tian X. H., Gronert K., Musto A., Hardy M., Gimenez J. M., Chiang N., Serhan C. N., et al. 2003. Novel docosanoids inhibit brain ischemia-reperfusion-mediated leukocyte infiltration and pro-inflammatory gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 43807–43817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hong S., Gronert K., Devchand P. R., Moussignac R. L., and Serhan C. N.. 2003. Novel docosatrienes and 17S-resolvins generated from docosahexaenoic acid in murine brain, human blood, and glial cells. Autacoids in anti-inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 14677–14687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Serhan C. N., Hong S., Gronert K., Colgan S. P., Devchand P. R., Mirick G., and Moussignac R. L.. 2002. Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J. Exp. Med. 196: 1025–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White P. J., St-Pierre P., Charbonneau A., Mitchell P. L., St-Amand E., Marcotte B., and Marette A.. 2014. Protectin DX alleviates insulin resistance by activating a myokine-liver glucoregulatory axis. Nat. Med. 20: 664–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tuazon M. A., and Henderson G. C.. 2012. Fatty acid profile of skeletal muscle phospholipid is altered in mdx mice and is predictive of disease markers. Metabolism. 61: 801–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Handschin C., Kobayashi Y. M., Chin S., Seale P., Campbell K. P., and Spiegelman B. M.. 2007. PGC-1alpha regulates the neuromuscular junction program and ameliorates Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Genes Dev. 21: 770–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.