Abstract

Objective

Computerized neuropsychological testing may facilitate screening for cognitive impairment in SLE. We used the Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics (ANAM), to compare patients with SLE, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and multiple sclerosis (MS) with healthy controls.

Methods

Patients with SLE (68), RA (33), and MS (20), were compared to 29 healthy controls. Efficiency of cognitive performance on eight ANAM subtests was examined using throughput (Tp), inverse efficiency (IE) and adjusted IE scores. The latter is more sensitive to higher cognitive functions because it adjusts for the impact of simple reaction time on performance. The results were analyzed using O’Brien’s generalized least squares test.

Results

Control subjects were the most efficient in cognitive performance. MS patients were least efficient overall (Tp and IE scores) and were less efficient than both SLE (p=0.01) and RA (p<0.01) patients, who did not differ. Adjusted IE scores were similar between SLE, RA patients and controls reflecting the impact of simple reaction time on cognitive performance. Thus, 50% of SLE patients, 61% of RA patients and 75% of MS patients were impaired on at least one ANAM subtest. Only 9% of RA patients and 11% of SLE patients were impaired on 4 or more subtests, whereas this was true for 20% of MS patients.

Conclusion

ANAM is sensitive to cognitive impairment. While such computerized testing may be a valuable screening tool, our results emphasize the lack of specificity of slowed performance as a reliable indicator of impairment of higher cognitive function in SLE patients.

Keywords: Systemic lupus erythematosus, Neuropsychiatric, Cognitive impairment, ANAM

Nervous system disease is common in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and encompasses a wide range of manifestations of which approximately 30% to 40% are attributable to SLE (1). Symptoms related to cognitive dysfunction are frequent and formal neuropsychological assessment techniques have consistently found a higher frequency of cognitive impairment in SLE patients compared to healthy and disease controls (2–6). Variability in the frequency of such deficits is due to several factors including bias in the selection of patients for study and the operational decisions for the definition of cognitive impairment.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has proposed a battery of neuropsychological tests for the assessment of cognitive function in SLE (7). Although comprehensive, there are several factors which limit the widespread use of these tests. For example, they are time consuming, require specialized training to administer and are subject to large practice effects. Although not a replacement for more detailed neuropsychological assessment, computerized neuropsychological testing may facilitate the rapid and efficient screening by non-experts of SLE patients for cognitive impairment.

The Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics (ANAM) is one such computerized test battery, comprising subtests which are modified versions of standard neuropsychological tests (8, 9). ANAM was designed to examine information processing efficiency in tasks ranging from simple reaction time, to attention/concentration, learning and memory, and executive functions (10). Most cognitive functions consist of multiple independent processes with diffuse neuroanatomical substrates, such that it can be difficult to determine exactly how a specific test score is achieved (11). However, reaction time paradigms that measure response latencies in addition to performance accuracy may be able to overcome some of these limitations and better dissociate overall slowing of performance from changes in higher-order cognitive functions. Simple and choice reaction time tasks can provide reliable, valid, and sensitive measures that have psychometric properties comparable to conventional neuropsychological tests (12, 13). Simple reaction time tasks can be used to provide a “baseline” measure that accounts for sensorimotor processing speed while choice reaction time paradigms can be used to examine efficiency within higher-order cognitive functions that may be more indicative of specific CNS damage. ANAM has been shown to be sensitive to subtle cognitive impairments in traumatic brain injury (14, 15), early dementia (16), and multiple sclerosis (MS) (17). Potential advantages of the ANAM for use in patients with SLE include its reportedly limited dependence on proficiency in English or in reading ability as well as its strong association with performance on the neuropsychological test battery recommended by the ACR (18).

As is the case for any diagnostic or screening procedure, the selection of controls is critical to the interpretation of test results. ANAM has previously been used in the evaluation of SLE patients in a limited number of studies (6, 18–22) but the inclusion of patients with other chronic diseases has been lacking. In the current study we have used ANAM to evaluate the cognitive performance of SLE patients compared to patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), MS and healthy controls. The inclusion of patients with a chronic disease lacking CNS involvement such as RA and one which specifically involves the CNS such as MS was done deliberately to compare and contrast the frequency and characteristics of impaired performance on cognitive tasks as detected by ANAM in these conditions.

Patients and Methods

Patients

All study subjects provided informed consent following procedures approved by the Capital District Health Authority Research Ethics Board. Sixty eight patients with SLE, 33 patients with RA, 20 patients with MS, and 29 healthy controls participated in the study. SLE and RA patients were recruited from the Dalhousie Lupus Clinic and general rheumatology clinics respectively in the Division of Rheumatology. All of these patients fulfilled the ACR classification criteria for SLE and RA respectively. Global SLE Disease Activity was measured by the SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) (23) and cumulative organ damage by the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC)/ACR damage index (24). In RA patients, disease activity and impact was assessed by the number of tender and swollen joints, ESR, CRP and Health assessment questionnaire (HAQ). MS patients were recruited from the Dalhousie MS Research Unit. All MS patients had stable, clinically definite, relapsing-onset MS according to the Poser criteria (25) and at worst required unilateral assistance to walk 100 metres. Neurologic disability was rated by the attending neurologists using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) (26). This scale allows for “grading” of impairment due to MS on a scale from 0 to 10, 0 indicating no impairment and 10 indicating death due to MS. All MS patients had an EDSS score of ≤6.0. Patients were excluded if they had co-morbid neurologic or psychiatric disorders or a history of substance abuse or learning disability. Healthy control participants who met the same exclusion criteria were recruited through local advertisements. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and reported no vision problems at the time of the study.

The following data were collected on all study participants: age, gender, ethnicity, education, medication use. In SLE and RA patients neuropsychiatric (NP) events were characterized using the ACR case definitions and were diagnosed by clinical evaluation supported with appropriate investigations as per the ACR glossary (7). Attribution of NP events to SLE and non-SLE causes was determined as previously described (27).

ANAM testing

The ANAM test battery (10) includes a variety of tasks designed to assess neurocognitive efficiency via measures of response time and accuracy. Most ANAM tasks resemble commonly used neuropsychological tests but have been modified to require a relatively simple subject-computer interface in which the required responses are either a yes/no or a same/different discrimination as indicated by pressing one of two mouse buttons. Each ANAM subtest is preceded by practice trials that include visual feedback regarding response accuracy but test trials do not include feedback. Two Simple Reaction Time (SRT; 20 trials each) tasks are administered at the beginning and at the end of the ANAM, in which participants are asked to respond as quickly as possible to a cue (“*”) in the center of the screen. Learning and recall are examined using code substitution subtests (CDS and CDD) where participants are first asked to determine whether a series of number/symbol pairings are consistent with a standard set provided at the top of the screen (CDS; 76 trials), and later to discriminate correct pairings from incorrect without the answer key (CDD; 36 trials). Working memory is assessed using both the Mathematical Processing (MTH; 20 trials) subtest, which requires participants to solve a series of mathematical operations and to determine whether the answer is greater or less than five, and using a version of the Sternberg Memory Scanning paradigm (ST6; 30 trials) that requires participants to memorize a fixed set of six upper-case letters and then determine whether letters presented later are part of this set. Sustained attention is measured using a Continuous Performance subtest (CPT; 81 trials), where individuals are presented with single digits at the rate of 950–1200 ms and are asked to indicate whether each digit is the same or different from the one that directly preceded it. Visual-spatial processing is tested using the Matching Grids (MTG; 20 trials) subtest, where participants are presented with two 4×4 block grid designs and are asked to indicate whether they are the same or different. Finally, the Match to Sample (MSP; 20 trials) subtest is used to assess short-term memory, attention, and visual-spatial discrimination. It requires participants to memorize a 4×4 block grid design and then determine which of two designs, presented after a delay of 5000–5100 ms, is the same as that studied.

Data Analysis

Each ANAM subtest generates measures of mean reaction time, accuracy, and “throughput” (Tp). Tp uses an individual’s reaction time and accuracy for a specific subtest to calculate their average number of correct responses per minute, and is thought to offer a more “stable” index of performance on a speeded test where speed-accuracy tradeoff may occur (28). However, a limitation of Tp is that, on tasks that assess higher cognitive functions (e.g., working memory or executive functions), it does not allow for differentiation between sensorimotor efficiency and mental processing efficiency. For instance, on an ANAM arithmetic task, the number of average correct responses per minute is a result of the efficiency of perceptual and motor processes (i.e., the efficiency of perceptual processing of the target and executing a motor program to press the response button) as well as the efficiency of the mental processes involved in mathematical computation and decision-making. Because Tp is calculated using mean reaction time per unit of performance time (i.e., mean RT per minute) it does not account for the contribution of sensorimotor efficiency to the final score. In clinical populations, this presents an obstacle to interpreting differences in performance efficiency both between and within groups of subjects. Sensorimotor slowing can be a relatively non-specific index of neurologic or neuromuscular impairment which can be affected to similar degree by a variety of medical conditions. As such, the utility of Tp in effectively differentiating clinically meaningful groups of subjects who differ in their cognitive efficiency can be questioned.

In order to overcome this limitation, while still providing a measure of overall performance that simultaneously takes account of speed and accuracy, we used the method first recommended by Townsend and Ashby (29) that has subsequently been referred to as “inverse efficiency” (IE) (30). IE is computed by dividing mean speed of responding by the proportion of correct responses within each subtest. Like Tp, IE accounts for any potential speed-accuracy tradeoff. However, since IE calculations are based on overall speed and accuracy (not just over a limited period of time), it is possible to “adjust” IE scores in order to minimize the influence of sensorimotor speed on the final outcome. In this study, the two Simple Reaction Time subtests (SRT_1 and SRT_2) that require perception and motor response to a simple stimulus (an asterisk) were considered to represent an index of “pure” sensorimotor speed. For each participant, the average response time on both of these subtests was used to calculate a “mean simple reaction time” score that represented overall sensorimotor speed (SRT_m=(SRT_1+SRT_2)/2). This SRT_m score was then subtracted from mean reaction time scores on individual ANAM subtests for each subject and the remaining response time was presumed to reflect the speed of mental processing required for each subtest. Adjusted IE scores were thus calculated using these “remainder reaction time” scores, in order to provide a measure of the efficiency of cognitive processing on each subtest. Unlike Tp, adjusted IE scores calculated in this manner should differentiate the effects of neurologic changes affecting cognitive processing from the effects of neurologic or other medical conditions on basic sensory and motor efficiency. Thus, differences in adjusted IE scores between clinical and control groups are more likely to reflect the specific cognitive effects of the clinical conditions.

Summary statistics and t-tests were used to examine differences in demographic characteristics of the groups. Linear regression was used to examine whether group differences in performance were affected by fatigue, as measured by the difference in SRTs at the beginning versus the end of the ANAM session for each subject. Overall group differences for all four groups as well as pairwise comparisons between groups across all subtests for both adjusted IE scores and for Tp scores were analyzed using O’Brien’s Generalized Least Squares test (31, 32). All comparisons were adjusted for age and education. The frequencies of impaired tasks based on adjusted IE scores across groups were compared. Possible predictors of impaired task performance within the three clinical groups were examined by ordinal regression. For SRT, overall group differences were examined by linear regression, adjusting for age and education. The frequency of impairment based on SRT and its relevant predictors were checked by logistic regression.

Results

Patients

Demographic characteristics, by group, are shown in Table 1. SLE patients were older than healthy controls (t=−2.14, p=0.04) and RA patients were older than MS patients (t=−2.99, p=0.004) and controls (t=−3.73, p<0.0001). The number of years of education was lower in RA patients compared to controls (t=−2.65, p=0.01), and in SLE patients compared to controls (t=−2.77, p=0.007). When these group differences in age and education were accounted for, all clinical groups had higher scores than controls on self-reported symptoms of depression (SLE: t=−2.75, p=0.007; RA: t=−2.92, p=0.005; MS: t=−2.56, p=0.02). Similarly, SLE and MS patients had higher scores than controls on self-reported anxiety (SLE: t=−2.21, p=0.03; MS: t=−2.05, p=0.05). None of these mean scores for the individual groups approached the HADS cut off scores of ≥11, recommended to identify the probable presence of depression and/or generalized anxiety disorder (33). SLE patients had mild disease activity and low cumulative organ damage as reflected by SLEDAI and SLCC/ACR damage index scores. The disease specific summary scores for RA and MS also indicated low disease activity and disability.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics and self-reported symptoms of anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) for patients and controls (mean±sd)

| SLE (n=68) | RA (n=33) | MS (n=20) | Control (n=29) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female:Male | 63:5 | 32:1 | 20:0 | 27:2 |

| Age (years) | 45.5±13.4 | 49.8±10.2 | 41.9±7.4 | 40.2±9.8 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| Caucasian | 92.6 | 93.9 | 100 | 100 |

| Other | 7.4 | 6.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Education (years) | 14.9±2.5 | 14.4±3.2 | 15.1±2.7 | 16.5±2.0 |

| Years since diagnosis | 11.9±9.5 | 12.0±11.0 | 6.9±5.1 | |

| HADS-D scores | 3.9±4.2 | 4.6±4.2 | 4.0±2.8 | 2.1±2.3 |

| HADS-A scores | 6.0±4.2 | 5.6±4.2 | 6.4±3.9 | 4.2±3.4 |

| Cumulative NP events (% patients) | 66.2 | 45.5 | 100 | 20.7 |

| Cumulative NPSLE events (% patients) | 32.4 | ------ | ------ | ------ |

| NP events < 4 weeks of assessment (% patients) | 45.6 | 30.3 | 0 | 3.4 |

| NPSLE events < 4 weeks of assessment (% patients) | 25.0 | ------ | ------ | ------ |

| SLEDAI | 4.4±4.2 | ------ | ------ | ------ |

| SLICC/ACR damage index | 1.3±1.9 | ------ | ------ | ------ |

| Tender joint count | ------ | 1.8±3.7 | ------ | ------ |

| Swollen joint count | ------ | 1.9±3.1 | ------ | ------ |

| ESR | ------ | 14.5±13.7 | ------ | ------ |

| CRP | ------ | 3.9±3.7 | ------ | ------ |

| HAQ | ------ | 1.0±1.1 | ------ | ------ |

| EDSS | ------ | ------ | 3.1±1.5 | ------ |

| Current medications (% patients) | ||||

| Prednisone | 16.2 | 6.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Average daily dose of prednisone (mg) | 13.0±18.9 | 5.8±2.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Biologics* | 0 | 33.3 | 80 | 0 |

| ASA (low dose) | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NSAIDs | 16.2 | 42.4 | 0 | 0 |

| COXIBs | 1.5 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Antimalarials | 48.5 | 45.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Methotrexate | 14.7 | 63.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Azathoprine | 10.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mycophenolate | 4.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Biologics: In patients with RA these were inhibitors of TNF-α (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab) and in patients with MS these were interferon β therapies or glatiramer acetate.

The potential effect of fatigue on test performance was examined by linear regression comparing group differences in the change in simple reaction time administered at the start of ANAM testing (SRT1) and simple reaction time administered at the end of the session (SRT2). Individual subjects’ mean reaction times on SRT1 were subtracted from those on SRT2 and larger differences were taken as an indication of a decline in overall speed of sensorimotor processing that could be attributed to fatigue. However, the absence of any differences between groups on SRT difference scores (p=0.82), suggested that any effects of fatigue on ANAM performance was equal across groups.

Group differences in performance on ANAM testing

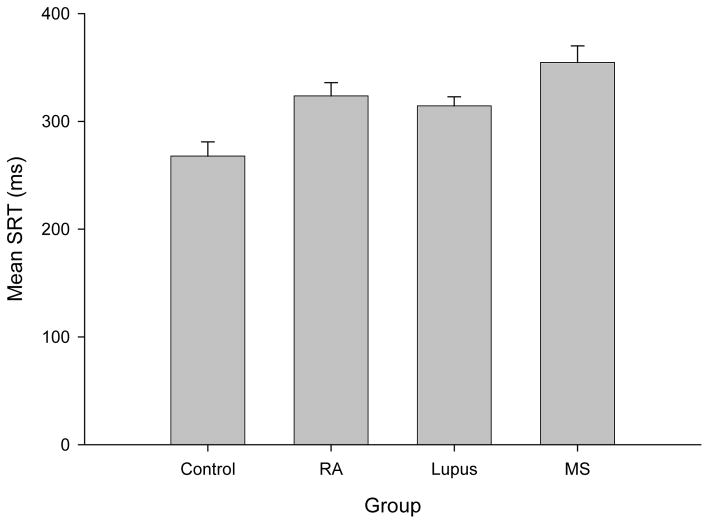

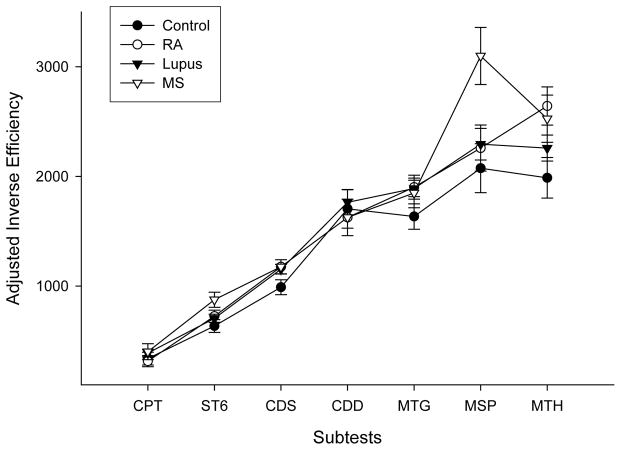

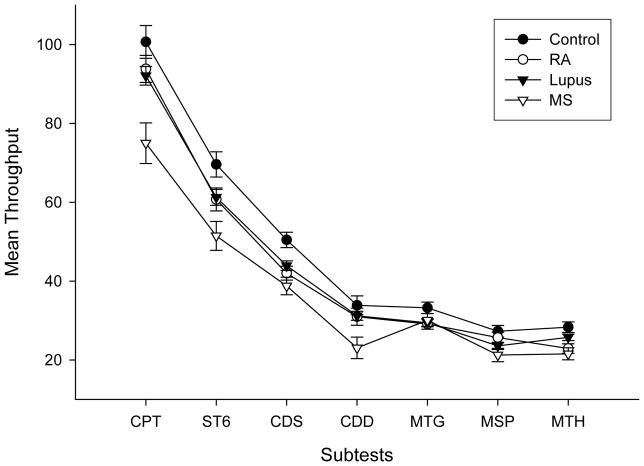

The mean SRT group differences were examined using ordinary linear regression. After controlling for the effect of age (p<0.01), controls were found to have lower mean SRT than MS (p<0.001), SLE (p<0.05) and RA (P<0.05) groups whereas the only differences between patient groups was a lower mean SRT for SLE patients than MS patients (p<0.05) (Figure 1). Average group performance on each of the ANAM subtests is illustrated in Figure 2 (for adjusted IE scores) and Figure 3 (for Tp scores). Overall group differences were found for both Tp (F(3,140)=7.49, p<0.01) and adjusted IE (F(3,138)=4.16, p=0.01). MS patients demonstrated the lowest Tp scores and the highest adjusted IE (i.e., least efficient performance among the groups), whereas controls had the highest Tp and lowest adjusted IE.

Figure 1.

Mean Simple Reaction Time (SRT) scores in minutes (ms) for the four test groups (healthy controls (Control), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (Lupus) and multiple sclerosis (MS); error bars represent Standard Error. These scores represent “average” SRT scores, calculated by combining participants’ performance on the two SRT subtests on the ANAM (SRT1+SRT2/2).

Figure 2.

Mean subtest inverse efficiency scores for the four test groups (healthy controls (Control), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (Lupus) and multiple sclerosis (MS) adjusted for simple reaction time; error bars represent Standard Error. The ANAM subtests were Continuous Performance subtest (CPT), Sternberg Memory Scanning paradigm (ST6), code substitution subtests (CDS and CDD), Matching Grids (MTG), Match to Sample (MSP), Mathematical Processing (MTH). Adjusted inverse efficiency scores were calculated by first subtracting individual average simple reaction time scores from individual average reaction time scores on the other ANAM subtests. The resulting scores were divided by the proportion of correct responses on each subtest to account for the speed-accuracy tradeoff and to reflect the efficiency of performance. Higher scores represent poorer/less efficient performance. The individual subtest data points for each group are connected for illustration purposes only.

Figure 3.

Average subtest throughput scores for the four test groups (healthy controls (Control), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (Lupus) and multiple sclerosis (MS); error bars represent Standard Error. The ANAM subtests were Continuous Performance subtest (CPT), Sternberg Memory Scanning paradigm (ST6), code substitution subtests (CDS and CDD), Matching Grids (MTG), Match to Sample (MSP), Mathematical Processing (MTH). Throughput represents the average number of correct responses per minute. The individual subtest data points for each group are connected for illustration purposes only. Higher scores represent better performance. The greater overlap between groups relative to Figure 2 (i.e. adjusted inverse efficiency scores) reflects the impact of simple reaction time differences on the performance in the ANAM subtests.

Pair-wise comparisons between the three disease groups on overall ANAM performance adjusted for age and education demonstrated lower Tp for MS patients than either SLE (t=3.03, p<0.01) or RA patients (t=4.64, p<0.01) while the SLE and RA groups did not differ (t=0.44, p>0.05). The same pattern of results held for adjusted IE scores with MS patients demonstrating higher adjusted IE scores in comparison to both SLE (t=2.54, p=0.01) and RA groups (t=3.03, p<0.01) while the SLE and RA groups once again did not differ (t=0.28; p>0.05).

Finally pair-wise comparisons between the control group and each of the three disease groups were conducted adjusting for age and education. On measures of Tp, controls differed from both the MS group (t=3.42; p<0.01) and the SLE group (t=2.53; p<0.05), but not from the RA group (t=1.10; p>0.05). However, for measures of adjusted IE, only the MS group differed from controls (t=3.55; p<0.01) while no differences in adjusted IE scores were found between controls and either SLE (t=1.52; p>0.05) or RA groups (t=0.53; p>0.05).

Group Differences in Frequency of Impairment on ANAM Tasks

In order to explore potential differences between patient groups in their frequency of overall cognitive impairment on ANAM subtests, subject’s adjusted IE scores on each subtest were converted to Z scores using the distributions of the control group performance as the reference. Patients were considered impaired on an ANAM subtest if their Z score differed from controls by 1.5 or more (i.e., performance 1.5 or more standard deviations worse than the mean performance of the control group). In a separate analysis, this same approach was also used to examine impairment in mean SRT. Predictors of cognitive impairment within groups were examined using ordinal regression, with overall frequency of impaired tasks used as the outcome variable within groups. Only age was shown to be positively associated with a higher frequency of impaired tasks in all three disease groups (p<0.01). None of the other variables, including disease duration, were related to cognitive impairment within groups. The same held true for the analyses of SRT impairment with age again being the only variable associated with a higher probability of impaired SRT (p<0.01). MS patients had a greater number of impaired subtests compared to SLE (p<0.05) and a trend toward a greater number of impaired subtests compared to RA (p=0.07) patients even after adjustment for age. SLE and RA patients did not differ (p=0.58). Although 61% of RA patients and 50% of SLE patients were impaired on at least one ANAM subtest, this was in contrast to a frequency of 75% for MS patients. Only 9% of RA patients and 11% of SLE patients were impaired in four or more ANAM tasks (i.e., more than half of the tasks) whereas 20% of MS patients were impaired to this extent. For SRT, there were no differences in the proportion of impaired subjects between the patient groups (MS=45%, SLE=43%, RA=51%).

Discussion

Cognitive impairment is reported to be one of the most common manifestations of NPSLE (2–6). Although sometimes profound in individual cases the majority of patients have subtle and frequently subclinical cognitive deficits which are evanescent rather than progressive over time. Recently the use of computerized neuropsychological testing, such as ANAM, has revealed poorer performance in SLE patients compared to healthy controls (6, 18–22). Our study was designed to compare and contrast the cognitive abilities of SLE patients to those with other chronic diseases in addition to healthy controls as determined using ANAM. We have confirmed that SLE patients have slower performance on cognitive tasks but comparable performance to that found in RA patients and better than that in MS patients with mild neurologic disability. Furthermore, conventional outcomes of ANAM testing did not distinguish between the non-specific reduction of performance efficiency and more specific abnormalities in higher cognitive functions such as working memory and executive tasks.

Cognitive dysfunction, assessed using formal clinical neuropsychological assessment techniques, has been reported in up to 80% of SLE patients (34), although most studies have found a prevalence between 17 – 66% (35, 36). Many individual patients have subclinical deficits. For example, a review of 14 cross-sectional studies of cognitive function in SLE revealed subclinical cognitive impairment in 11 – 54% of patients (35). A single pattern of SLE-associated cognitive dysfunction has not been found, but commonly identified abnormalities include overall cognitive slowing, decreased attention, impaired working memory and executive dysfunction (e.g. difficulty with multitasking, organization, and planning). As the majority of SLE patients with cognitive impairment have relatively mild deficits, the careful selection and assessment of cognitive performance in control groups is of critical importance in order to define expected levels of function in healthy individuals and those with chronic diseases other than SLE. Although cognitive impairment may be viewed as a distinct subset of NPSLE it can also serve as a surrogate of overall brain health in SLE patients which may be affected by a variety of factors including other NP syndromes.

ANAM has been used in previous cross-sectional (6, 18–20, 22) and longitudinal studies (21) to evaluate cognitive performance in SLE. It has been validated by comparison with the ACR recommended battery (18–20) of neuropsychological tests and found to have a sensitivity for the detection of cognitive impairment of 76.2%, specificity of 82.8% and overall correct classification of 80% (18). The frequency of cognitive impairment reported using ANAM was 69% in adult SLE patients with a mean disease duration of 8 years (6) and 59% in childhood-onset SLE with a mean age of 16.5 years at the time of assessment (19). In adult patients studied within 9 months of SLE diagnosis cognitive impairment was present in 21% – 61% of cases, depending upon the stringency of the definition of impairment (22). All of these studies have used either published ANAM norms, derived mostly from young males in the US military (37), or healthy controls recruited from a single academic center (6) to determine the presence of cognitive impairment. In our study the frequency of cognitive impairment was 11% – 50% in SLE patients, depending up the stringency of the decision rules, when compared to locally recruited healthy controls. However, this frequency was comparable to that seen in patients with RA (9% – 61%) and lower than in MS patients (20% – 75%). That the performance of SLE patients on ANAM testing is better than in patients with stable demyelinating disease is perhaps to be expected. However, the comparable frequency of abnormalities in RA patients which does not primarily affect the central nervous system raises concerns regarding the presumed etiology of deficits detected by ANAM testing.

Cognition is the sum of intellectual functions that result in thought. It includes reception of external stimuli, information processing, learning, storage and expression. Disturbance of even one of these functions can result in disruption of normal thought production and present as cognitive dysfunction, perhaps most easily seen on sensitive timed measures of performance. In all previous studies of SLE the primary outcome of performance on ANAM subtests has been “througput” (Tp), a measure of the average number of correct responses per minute, which has been proposed as the best ANAM indicator of cognitive efficiency (10, 20). However, in the assessment of higher cognitive functions, Tp does not distinguish between reduced sensorimtor efficiency and impaired mental processing. Thus, we generated adjusted IE scores as an indicator of efficiency of mental processing that while still controlling for individual differences in speed/accuracy tradeoff, provided a measure that more clearly reflected speed of information processing. The finding that Tp scores for both MS and SLE patients differed significantly from healthy controls but that adjusted IE scores were significantly different only for MS patients suggests that slowing in ANAM performance in SLE patients is not necessarily attributable to a decline in the efficiency of mental processing alone.

In both SLE and non-SLE populations there can be several potential causes for reduced performance of cognitive tasks other than primary central nervous system disease (38). Many of these have been addressed in the current study. For example the analyses of differences in ANAM scores between groups were adjusted for age, the strongest predictor of cognitive decline, and years of education. The potential impact of fatigue, mood, concurrent neuropsychiatric disease and disease duration was not significant. The patient groups also had comparable disease status in that patients with SLE, RA and MS all had quiescent disease activity with relatively limited disability at the time of ANAM testing. There was also considerable overlap in the medications utilized by patients with SLE land RA. Indeed it is possible that subtle non-specific neurotoxicity from chronic use of immunosuppressive agents (39, 40) may account for the non-specific cognitive slowing in some patients.

There are a number of limitations to the current study. First, formal neuropsychological assessment or neuroimaging were not used to look for clinical behavioural and neuroanatomical correlates of the abnormalities found on ANAM testing. Second, there were demographic differences, especially in age, between some groups that required adjustment in the analyses for these differences. Finally, the patients and controls did not undergo repeat testing with ANAM to determine if the differences detected remain stable over time. The strengths of our study are the use of locally recruited healthy controls rather than published norms to determine expected performance on ANAM testing, the inclusion of two distinct disease control groups in order to examine the relative severity and etiology of cognitive impairment in our SLE patients and the generation of adjusted IE scores to more specifically evaluate higher cognitive functions and the efficiency of mental processing.

What therefore is the role of ANAM in the assessment of cognitive complaints in SLE patients? It is clear from our findings and those of previous studies that ANAM is sensitive to the detection of both CNS and non-CNS causes of reduced cognitive efficiency. Furthermore, it may detect both the effects of a specific neuroanatomical injury such as demyelination or a generalized non-specific reduction in overall slowing of cognitive function which is likely present in a variety of chronic inflammatory diseases. ANAM cannot be used to determine impairment of specific domains of cognitive abilities and was not designed as a substitute for formal neuropsychological assessment. Future studies are required to determine its role in screening for cognitive impairment in SLE patients. Its value in the evaluation of changes in SLE patients’ cognitive performance over time may lie in its sensitivity, which was evident in ours and previous studies, but this will require longitudinal assessment, ideally with concurrent neuropsychological and neuroimaging investigations.

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

John G. Hanly (Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant MOP-57752, Capital Health Research Fund), Li Su (MRC(UK) grant U.1052.00.009), V. Farewell (MRC(UK) grant U.1052.00.009).

References

- 1.Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Bae SC, Gordon C, Wallace DJ, et al. Neuropsychiatric events at the time of diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus: an international inception cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(1):265–73. doi: 10.1002/art.22305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbotte RM, Denburg SD, Denburg JA. Prevalence of cognitive impairment in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174(6):357–64. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198606000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanly JG, Fisk JD, Sherwood G, Jones E, Jones JV, Eastwood B. Cognitive impairment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(4):562–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginsburg KS, Wright EA, Larson MG, Fossel AH, Albert M, Schur PH, et al. A controlled study of the prevalence of cognitive dysfunction in randomly selected patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35(7):776–82. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kozora E, Thompson LL, West SG, Kotzin BL. Analysis of cognitive and psychological deficits in systemic lupus erythematosus patients without overt central nervous system disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(12):2035–45. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brey RL, Holliday SL, Saklad AR, Navarrete MG, Hermosillo-Romo D, Stallworth CL, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes in lupus: prevalence using standardized definitions. Neurology. 2002;58(8):1214–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.8.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(4):599–608. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<599::AID-ANR2>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reeves DL, Winter KP, Bleiberg J, Kane RL. ANAM genogram: historical perspectives, description, and current endeavors. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22 (Suppl 1):S15–37. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves DL, Kane R, Winter K. Automated neuropsychological assessment metrics (ANAM V3.11a/96) user’s manual:clinical and neurotoxicology subset. San Diego, CA: National Cognitive Foundation; 1996. (Report No. NCRF-SR-96-01) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bleiberg J, Kane RL, Reeves DL, Garmoe WS, Halpern E. Factor analysis of computerized and traditional tests used in mild brain injury research. Clin Neuropsychol. 2000;14(3):287–94. doi: 10.1076/1385-4046(200008)14:3;1-P;FT287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuss DT, Levine B. Adult clinical neuropsychology: lessons from studies of the frontal lobes. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:401–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reicker LI, Tombaugh TN, Walker L, Freedman MS. Reaction time: An alternative method for assessing the effects of multiple sclerosis on information processing speed. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(5):655–64. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tombaugh TN, Rees L, Stormer P, Harrison AG, Smith A. The effects of mild and severe traumatic brain injury on speed of information processing as measured by the computerized tests of information processing (CTIP) Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(1):25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bleiberg J, Garmoe WS, Halpern EL, Reeves DL, Nadler JD. Consistency of within-day and across-day performance after mild brain injury. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1997;10(4):247–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levinson DM, Reeves DL. Monitoring recovery from traumatic brain injury using automated neuropsychological assessment metrics (ANAM V1.0) Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1997;12(2):155–66. doi: 10.1093/arclin/12.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levinson D, Reeves D, Watson J, Harrison M. Automated neuropsychological assessment metrics (ANAM) measures of cognitive effects of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2005;20(3):403–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilken JA, Kane R, Sullivan CL, Wallin M, Usiskin JB, Quig ME, et al. The utility of computerized neuropsychological assessment of cognitive dysfunction in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003;9(2):119–27. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms893oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roebuck-Spencer TM, Yarboro C, Nowak M, Takada K, Jacobs G, Lapteva L, et al. Use of computerized assessment to predict neuropsychological functioning and emotional distress in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(3):434–41. doi: 10.1002/art.21992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunner HI, Ruth NM, German A, Nelson S, Passo MH, Roebuck-Spencer T, et al. Initial validation of the Pediatric Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics for childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(7):1174–82. doi: 10.1002/art.23005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holliday SL, Navarrete MG, Hermosillo-Romo D, Valdez CR, Saklad AR, Escalante A, et al. Validating a computerized neuropsychological test battery for mixed ethnic lupus patients. Lupus. 2003;12(9):697–703. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu442oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaurin EY, Holliday SL, Williams P, Brey RL. Predictors of cognitive dysfunction in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurology. 2005;64(2):297–303. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149640.78684.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petri M, Naqibuddin M, Carson KA, Sampedro M, Wallace DJ, Weisman MH, et al. Cognitive function in a systemic lupus erythematosus inception cohort. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(9):1776–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35(6):630–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gladman D, Ginzler E, Goldsmith C, Fortin P, Liang M, Urowitz M, et al. The development and initial validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(3):363–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poser CM, Paty DW, Scheinberg L, McDonald WI, Davis FA, Ebers GC, et al. New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols. Ann Neurol. 1983;13(3):227–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–52. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanly JG, Su L, Farewell V, McCurdy G, Fougere L, Thompson K. Prospective study of neuropsychiatric events in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(7):1449–59. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorne DR. Throughput: a simple performance index with desirable characteristics. Behav Res Methods. 2006;38(4):569–73. doi: 10.3758/bf03193886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Townsend JT, Ashby FG. Stochastic modeling of elementary psychological processes. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christie J, Klein R. Familiarity and attention: does what we know affect what we notice? Mem Cognit. 1995;23(5):547–50. doi: 10.3758/bf03197256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Brien PC. Procedures for comparing samples with multiple endpoints. Biometrics. 1984;40(4):1079–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dallow NS, Leonov SL, Roger JH. Practical usage of O’Brien’s OLS and GLS statistics in clinical trials. Pharm Stat. 2008;7(1):53–68. doi: 10.1002/pst.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ainiala H, Hietaharju A, Loukkola J, Peltola J, Korpela M, Metsanoja R, et al. Validity of the new American College of Rheumatology criteria for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes: a population-based evaluation. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(5):419–23. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200110)45:5<419::aid-art360>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denburg SD, Denburg JA. Cognitive dysfunction and antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2003;12(12):883–90. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu497oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanly JG, Liang MH. Cognitive disorders in systemic lupus erythematosus. Epidemiologic and clinical issues. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;823:60–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reeves DL, Bleiberg J, Roebuck-Spencer T, Cernich AN, Schwab K, Ivins B, et al. Reference values for performance on the Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics V3.0 in an active duty military sample. Mil Med. 2006;171(10):982–94. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.10.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanly JG, Harrison MJ. Management of neuropsychiatric lupus. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19(5):799–821. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Correa DD, Ahles TA. Cognitive adverse effects of chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2007;1(1):57–62. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32813a328f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lofstad GE, Reinfjell T, Hestad K, Diseth TH. Cognitive outcome in children and adolescents treated for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with chemotherapy only. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(1):180–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]