Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between neuropsychiatric (NP) events with antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin), anti-β2 glycoprotein-I, anti-ribosomal P and anti-NR2 glutamate receptor antibodies in an international inception cohort.

Methods

NP events were identified using the ACR case definitions and clustered into central/peripheral and diffuse/focal events. Attribution of NP events was determined using decision rules of different stringency (model A and model B). Autoantibodies were measured without knowledge of NP events or their attribution.

Results

412 patients (87.3% female; mean (± SD) age of 34.9 ± 13.5 years; mean disease duration 5.0 ± 4.2 months) were studied. There were 214 NP events in 133 (32.3%) patients. NP events attributed to SLE varied from 15% (model A) to 36% (model B). There was no association between autoantibodies and NP events from all causes. However the frequency of anti-ribosomal P antibodies in patients with NP events due to SLE (model A) was 4/24 (16.6%) compared to 3/109 (2.8%) for all other NP events and 24/279 (8.6%) with no NP events (P=0.07). Furthermore anti-ribosomal P antibodies in patients with central NP events attributed to SLE (model A) was 4/20 (20%) vs. 3/107 (2.8%) for other NP events and 24/279 (8.6%) with no NP events (P = 0.04). For diffuse NP events the antibody frequencies were 3/11 (27%) compared to 4/111 (3.6%) and 24/279 (8.6%) respectively (P=0.02).

Conclusion

NP events at onset of SLE were associated with anti-ribosomal P antibodies, suggesting a pathogenetic role for this autoantibody. There was no association with other autoantibodies.

Keywords: Systemic lupus erythematosus, Neuropsychiatric, Autoantibodies, Inception cohort, Attribution

Neurological and psychiatric events are well described in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The frequency of neuropsychiatric (NP) disease, classified using the ACR case definitions, varies from 37% to 95% of patients (1–5). The clinical significance of NP events is underlined by the negative impact on health-related quality of life (3, 6) and increased mortality (7). Determining the correct attribution of NP events is a significant challenge when dealing with nervous system disease in individual SLE patients and is a critical factor in selecting the correct treatment and determining prognosis. To date there are no reliable biomarkers which can be used to make this decision.

Lupus specific mechanisms underlying NP disease include vasculopathy of intracranial vessels, local or systemic production of inflammatory mediators and the generation of specific autoantibodies (8–11). The latter include antiphospholipid antibodies, anti-ribosomal P antibodies and autoantibodies which bind to neuronal antigens such as the recently described antibodies to the NR2 glutamate receptor (12). Although there is biological plausibility and data from in vitro studies and animal studies (12–16) to implicate these autoantibodies in the causality of nervous system disease, studies of human SLE have provided inconsistent findings (17–21). Previous efforts have been limited by their cross-sectional study design, the inclusion of patients with variable disease duration, and lack of standardization in both the classification of NP events and the methodology used for autoantibody detection. Thus, in the current study we have assembled an international, inception cohort of SLE patients to examine the association between a panel of autoantibodies and nervous system events at the time of diagnosis of SLE.

Patients and Methods

Research study network

The study was conducted by members of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) (22) which consists of 30 investigators in 27 international academic medical centres. Data were collected prospectively on patients presenting with a new diagnosis of SLE. All information was submitted to the coordinating centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada and entered into a centralized Access database. Appropriate procedures were instituted to ensure data quality, management and security. Additional information on the same patients was collected concurrently as part of a study examining atherosclerosis in SLE and submitted to the coordinating centre for that study at the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Electronic data transfer occurred between the Toronto and Halifax sites and the merged datasets were available for analyses. The study protocol was approved by the Capital Health Research Ethics Board, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada and by each of the participating centre’s own institutional research ethics review boards.

Patients

All patients fulfilled four or more of the ACR classification criteria for SLE (23) and provided written informed consent. The date of diagnosis was taken as the time when these cumulative criteria were first recognized. Enrollment in the study was encouraged as close as possible to the date of diagnosis but was permitted for up to 15 months following the diagnosis. Variables which were collected included age, gender, ethnicity, education and medication history. Lupus-related variables included the ACR classification criteria for SLE (23), the SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) (24) and the SLICC/ACR damage index (SDI) (25) in patients whose disease duration was six months or longer. Routine laboratory variables included hematology, serum and urine chemistry and immunologic variables required for the generation of SLEDAI and SDI scores.

Neuropsychiatric (NP) events

An enrollment window was defined within which all NP events, some of which are inherently evanescent, were captured. To ensure inclusion of NP events which may have been a component of the presentation of lupus but which occurred prior to the accumulation of four ACR classification criteria, the enrollment window extended from 6 months prior to the date of diagnosis of SLE up to the enrollment date. As the latter could occur up to 15 months following the diagnosis of SLE, the maximum duration of the enrollment window was 21 months. The specific NP events which were identified within this time frame were based upon the ACR nomenclature and case definitions for 19 NP syndromes (26) described in SLE. Screening for all NP syndromes was done primarily by clinical evaluation and subsequent investigations were performed only if clinically warranted. In order to further improve the consistency of data collection, a checklist of NP symptoms was distributed to each of the participating sites for use during patient encounters. In the majority of cases, the diagnosis of cognitive impairment was made on the basis of clinical assessment rather than formal neuropsychological testing. The eight cognitive domains which were assessed were Simple attention, Complex attention, Memory, Visual-Spatial processing, Language, Reasoning/problem solving, Psychomotor speed and Executive functions.

The occurrence of all NP events within the enrollment window was identified and additional information was recorded. The specific information depended upon the type of NP event and was guided by the ACR glossary for the 19 NP syndromes (26). This included a list of potential etiologic factors other than SLE which were identified for exclusion, or recognized as an “association”, acknowledging that in some situations it is not possible to be definitive about attribution. Collectively, these “exclusions” and “associations” were referred to as “non-SLE factors” and were used in part to determine the eventual attribution of NP events. Patients could have more than one type of NP event but repeated episodes of the same NP event occurring within the enrollment window were recorded only once. In the latter case the time of the first episode was taken as the date of onset of the NP event.

Attribution of NP events

Participating centres were asked to report all NP events regardless of etiology and in particular no NP events were excluded on the basis that an individual investigator felt that these were not attributable to SLE. Decision rules were derived to determine the attribution of NP events which occurred within the enrollment window. Factors which were considered included: (i) onset of NP event(s) prior to the enrollment window; (ii) presence of concurrent non-SLE factor(s) which were identified as part of the ACR definitions for each NP syndrome and considered to be a likely cause or significant contributor to the event; (iii) occurrence of "minor” NP events as defined by Ainiala et al who have previously reported such events in a high frequency of normal population controls (1). These latter NP manifestations include all headaches, anxiety, mild depression (i.e. all mood disorders which fail to meet the criteria for “major depressive-like episodes”), mild cognitive impairment (deficits in less than 3 of the 8 specified cognitive domains) and polyneuropathy without electrophysiological confirmation.

The attribution of NP events to SLE and non-SLE causes was determined by two sets of decision rules of different stringency as described in detail elsewhere (6):

Attribution Model A: NP events which had their onset prior to the enrollment window or had at least one “exclusion” or “association” or were one of the NP events identified by Ainiala (1) were attributed to a non-SLE etiology.

Attribution Model B: NP events which had their onset at least 10 years prior to the diagnosis of SLE or had at least one “exclusion” or were one of the NP events identified by Ainiala (1) were attributed to a non-SLE etiology.

Determination of autoantibodies

Serum samples were collected within 5.3 ± 17.1 days (mean ± SD) days of the enrollment date. Autoantibodies, with the exception of anti-dsDNA antibodies, were measured in Dr. Joan Merrill’s laboratory at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, USA. Autoantibody determinations were made without knowledge of the occurrence of NP events or their attribution in individual patients.

ELISA for anti-NR2 antibodies

NR2 human peptide sequence, (Asp Trp Glu Tyr Ser Val Trp Leu Ser Asn)8 Lys 4 Lys2 Lys-β Ala, was synthesized using f-moc chemistry, purified by HPLC and confirmed by Edman degradation at the Molecular Biology Proteomics Facility of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK. High binding, Nunc 96-well polystyrene plates were coated with 5 ug/mL of NR2 peptide in borate buffered saline and blocked with borate buffered saline, bovine serum albumin (Fraction V, Sigma) and 1.2% Tween 80. Patient sera, positive and negative controls were added, diluted 1/100 in the same blocking buffer. Plates were washed with borate buffered saline between each step with vigorous pounding to eliminate non-specific binding. Secondary antibody was an alkaline phosphatase conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Sigma) with the addition of goat serum to block non-specific binding (doner herd, Sigma). Plates were developed using p-NPP substrate buffer (Sigma). Optical density of the enzyme-linked immune assay were read at 405 (primary wavelength) and 450 (secondary wavelength). Serial dilutions of a high binding positive control were used as a calibrator.

Antiphosphilipid and anti-ribosomal P antibodies

Lupus anticoagulant and ELISAs for anticardiolipin, anti-β2 glycoprotein-I and anti- ribosomal P protein were performed as previously described (27–29). β2 glycoprotein-I, purified from human plasma, was the gift of Drs. Naomi and Charles Esmon, and ribosomal P protein was provided by the laboratory of Dr. Morris Reichlin, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.

Anti-dsDNA antibodies

Anti-dsDNA antibodies were measured at each of the participating SLICC centers and reported as positive or negative according to the centers specific normal range.

Statistical analysis

Individual NP manifestations were categorized by attribution to SLE (model A or model B) or non-SLE causes. The distribution of patients in this hierarchy, and a no NP event class, was examined for associations with different autoantibodies. In addition the NP manifestations were clustered into subgroups for additional analyses of clinical-serologic associations. Thus, the 19 NP syndromes were arranged into central and peripheral nervous system manifestations as previously described (26). Diffuse NP syndromes were identified as aseptic meningitis, demyelinating syndrome, headache, acute confusional state, anxiety disorder, cognitive dysfunction, mood disorder and psychosis. Focal NP syndromes were cerebrovascular disease, Guillain Barré syndrome, movement disorder, myelopathy, seizure disorders, autonomic neuropathy, mononeuropathy, myasthenia gravis, cranial neuropathy, plexopathy and polyneuropathy. In view of previously reported clinical-serologic correlations the following associations were also specifically examined: (i) lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin and anti-β2-GPI with cerebrovascular disease, seizure disorders, demyelinating syndrome and movement disorder; (ii) anti-ribosomal P and anti-NR2 with mood disorder, cognitive impairment and psychosis. Reported significance levels are based on χ2 tests, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

Results

Patients

A total of 412 patients were recruited in 18 centres between October 1999 and April 2005. The median (range) number of patients enrolled in each centre was 13 (3–56). The patients were predominantly women, with a mean (± SD) age of 34.9 ± 13.5 years and a wide ethnic distribution although predominantly Caucasian (Table 1). At enrollment the mean disease duration was only 5 ± 4.2 months despite the opportunity to recruit patients up to 15 months following the diagnosis of SLE. The prevalence of individual ACR classification criteria reflected an unselected patient population. The mean SLEDAI and SDI scores revealed moderate global disease activity and minimal cumulative organ damage respectively. Therapy at the time of enrollment reflected the typical range of lupus medications.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical manifestations of SLE patients

| Number of Patients | 412 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 357 (87.3%) |

| Male | 52 (12.7%) |

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 34.9 (13.5) |

| Ethnicity: | |

| Caucasian | 255 (62.5%) |

| Hispanic | 12 (2.9%) |

| Asian | 70 (17.2%) |

| Black | 56 (13.7%) |

| Other | 15 (3.7%) |

| Single/Married/Other | 177 (43.3%)/168 (41.1%)/64 (15.6) |

| Post secondary education | 273 (66.75%) |

| Disease duration (months) (mean ± SD) | 5.0 ± 4.2 |

| Number of ACR criteria (mean ± SD) | 4.9 ± 1.0 |

| Cumulative ACR manifestations | |

| Malar rash | 138 (33.7%) |

| Discoid rash | 46 (11.2%) |

| Photosensitivity | 146(35.7 %) |

| Oral/nasopharyngeal ulcers | 111 (27.1%) |

| Serositis | 306 (74.8%) |

| Arthritis | 161 (39.4%) |

| Renal disorder | 107 (26.2%) |

| Neurological disorder | 22 (5.4%) |

| Hematologic disorder | 251 (61.4%) |

| Immunologic disorder | 313 (76.5%) |

| Antinuclear antibody | 401 (98.0%) |

| SLEDAI score (mean ± SD) | 6.1 ± 5.9 |

| SLICC/ACR damage index score (mean ± SD) | 0.32 ± 0.7 |

| Medications | |

| Corticosteroids | 267 (65.3%) |

| Antimalarials | 256 (63.2%) |

| Immunosuppressants | 149 (36.9%) |

| ASA | 61 (15.0%) |

| Antidepressants | 40 (9.8%) |

| Anticonvulsants | 18 (4.4%) |

| Warfarin | 18 (4.4%) |

| Antipsychotics | 3 (0.7%) |

Neuropsychiatric (NP) manifestations

Within the enrollment window 133/412 (32.3%) patients had at least 1 NP event and 47/412 (11.4%) had 2 or more events with a maximum of 7 events. The NP events and their attribution are summarized in Table 2. There were a total of 214NP events, encompassing 14 of the 19 NP syndromes: headache (40.2%), mood disorders (14.9%), anxiety disorder (7.9%), cerebrovascular disease (6.5%), cognitive dysfunction (6.5%), acute confusional state (5.1%), seizure disorders (5.1%), polyneuropathy (3.7 %), psychosis (3.3%), mononeuropathy (2.8%), cranial neuropathy (1.9%), aseptic meningitis (0.9%), myelopathy (0.5%) and movement disorder (0.5%). The proportion of NP events attributed to SLE varied from 15% – 36% using alternate attribution models and occurred in 5.8 % [model A] – 12.9 % [model B] of patients. There were no patients with autonomic disorder, Guillain-Barré syndrome, demyelinating syndrome, myasthenia gravis or plexopathy. Of the 214 NP events 196 (91.6 %) affected the central nervous system and 18 (8.4%) involved the peripheral nervous system. The classification of events into diffuse and focal was 169 (79.0%) and 45 (21.0 %), respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics of neuropsychiatric syndromes in SLE patients as indicated by the number of NP events and their attribution using attribution models A and B

| NP events (%) regardless of attribution | NP events due to SLE (model A) | NP events due to SLE (model B without A) | NP events due to SLE (Model B) | NP events due to non-SLE causes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headache | 86 (40.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 86 |

| Mood disorders | 32 (14.9) | 3 | 12 | 15 | 17 |

| Anxiety disorder | 17 (7.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 14 (6.5) | 6 | 8 | 14 | 0 |

| Cognitive dysfunction | 14 (6.5) | 1 | 8 | 9 | 5 |

| Seizure disorder | 11 (5.1) | 4 | 5 | 9 | 2 |

| Acute confusional state | 11 (5.1) | 5 | 3 | 8 | 3 |

| Polyneuropathy | 8 (3.7) | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Psychosis | 7 (3.3) | 3 | 4 | 7 | 0 |

| Mononeuropathy | 6 (2.8) | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| Cranial neuropathy | 4 (1.9) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Aseptic meningitis | 2 (0.9) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Myelopathy | 1 (0.5) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Movement disorder | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Autonomic disorder | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Guillain-Barre syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Demyelinating syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Plexopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 214 | 32 | 45 | 77 | 137 |

- Model A: The onset of NP events prior to the enrollment window, the identification of any non-SLE factors which contributed to or were responsible for the NP event or the occurrence of a “minor” NP event as defined by Ainiala et al (1) indicated that the NP event was not attributed to SLE.

- Model B: The onset of NP events more than 10 years prior to the diagnosis of SLE, the identification of non-SLE factors which were responsible for the NP event (“exclusion factors” only) or the occurrence of a “minor” NP event as defined by Ainiala et al (1) indicated that the NP event was not attributed to SLE.

Autoantibodies and NP events

The overall prevalence of the different autoantibodies within the inception cohort is illustrated in Figure 1. This varied from 8% for anti-ribosomal P antibodies to 45% for anti-DNA antibodies. There was no significant association between the frequency of autoantibodies in patients with and without NP events due to any cause (Figure 1). In fact the prevalence of autoantibodies was usually higher in patients without NP events although this did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Frequency of autoantibodies in SLE inception cohort. The upper panel illustrates the proportion of all SLE patients with autoantibodies and the lower panel illustrates the frequency of autoantibodies in patients with and without neuropsychiatric (NP) events from all causes.

LA = lupus anticoagulant; aCL = IgG anticardiolipin antibody; aBeta-2 = anti-β2-glycoprotein I; anti-P = anti-ribosomal P antibody; aNR2 = anti-NR2 glutamate receptor antibody; aDNA = anti-DNA antibody.

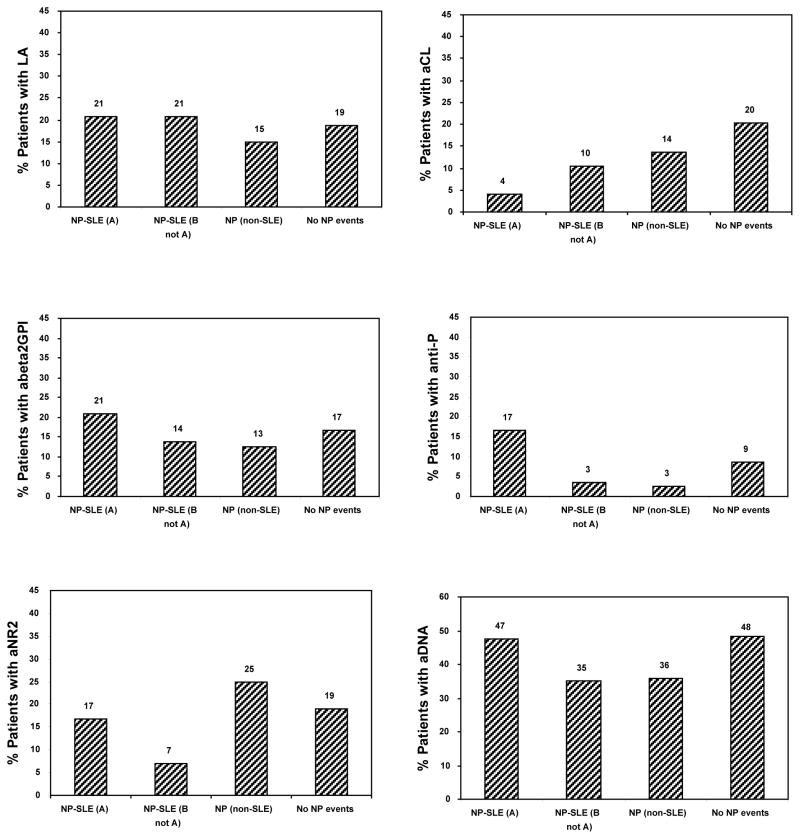

The NP events were then classified by attribution to determine if this would provide a stronger correlation with specific autoantibodies. Four mutually exclusive groups were examined: patients with NP events attributed to SLE who qualify under model A (NP-SLE (A)), patients with NP events attributed to SLE who qualify under model B but not model A (NP-SLE (B not A)), patients with NP events attributed to non-SLE causes (NP (non-SLE)) and patients with no NP events (No NP events)(Figure 2). In this analysis the only clinical-serologic association that approached significance was between NP events attributed to SLE and anti-ribosomal P antibodies (P = 0.07). The frequency of anti-ribosomal P antibodies in patients with NP events due to SLE determined using the most stringent of the two attribution models (model A) was 4/24 (16.6%) compared to 3/109 (2.8%) for patients with all other NP events and 24/279 (8.6%) in patients with no NP events. The specific events in the 4 patients with anti-ribosomal P antibodies and NP events attributed to SLE (model A) were psychosis only (1 patient), psychosis and cognitive dysfunction (1 patient), acute confusional state, myelopathy and mononeuropathy (1 patient) and cerebrovascular disease (1 patient). Stronger associations for anti-ribosomal P antibodies and NP events attributed to SLE (model A) were observed with central (P = 0.04) and diffuse (P=0.02) NP events (Figure 3). Thus for central NP events the frequency of anti-ribosomal P antibodies in patients with NP events attributed to SLE (model A) was 4/20 (20%) compared to 3/107 (2.8%) for patients with all other central NP events and 24/279 (8.6%) in patients with no NP events. For diffuse NP events the antibody frequencies were 3/11 (27%) compared to 4/111 (3.6%) and 24/279 (8.6%) respectively. Significant differential effects between central/peripheral and diffuse/focal classifications could not be detected with the small number of cases available.

Figure 2.

The frequency of autoantibodies in SLE patients with and without neuropsychiatric (NP) events. Four mutually exclusive groups were examined: patients with NP events attributed to SLE who qualify under model A (NP-SLE (A)), patients with NP events attributed to SLE who qualify under model B but not model A (NP-SLE (B not A)), patients with NP events attributed to non-SLE causes (NP (non-SLE)) and patients with no NP events (No NP events).

Model A: The onset of NP events prior to the enrollment window, the identification of any non-SLE factors which contributed to or were responsible for the NP event or the occurrence of a “minor” NP event as defined by Ainiala et al (1) indicated that the NP event was not attributed to SLE.

Model B: The onset of NP events more than 10 years prior to the diagnosis of SLE, the identification of non-SLE factors which were responsible for the NP event (“exclusion factors” only) or the occurrence of a “minor” NP event as defined by Ainiala et al (1) indicated that the NP event was not attributed to SLE.

LA = lupus anticoagulant; aCL = IgG anticardiolipin antibody; aBeta-2 = anti-β2- glycoprotein I; anti-P = anti-ribosomal P antibody; aNR2 = anti-NR2 glutamate receptor antibody; aDNA = anti-DNA antibody.

Figure 3.

The frequency of anti-ribosomal P antibodies in SLE patients with and without central (upper panel) and diffuse (lower panel) neuropsychiatric (NP) events. Central NP manifestations have been previously described (26). Diffuse NP syndromes were identified as aseptic meningitis, demyelinating syndrome, headache, acute confusional state, anxiety disorder, cognitive dysfunction, mood disorder and psychosis.

Four mutually exclusive groups were examined: patients with NP events attributed to SLE who qualify under model A (NP-SLE (A)), patients with NP events attributed to SLE who qualify under model B but not model A (NP-SLE (B not A)), patients with NP events attributed to non-SLE causes (NP (non-SLE)) and patients with no NP events (No NP events).

Model A: The onset of NP events prior to the enrollment window, the identification of any non-SLE factors which contributed to or were responsible for the NP event or the occurrence of a “minor” NP event as defined by Ainiala et al (1) indicated that the NP event was not attributed to SLE.

Model B: The onset of NP events more than 10 years prior to the diagnosis of SLE, the identification of non-SLE factors which were responsible for the NP event (“exclusion factors” only) or the occurrence of a “minor” NP event as defined by Ainiala et al (1) indicated that the NP event was not attributed to SLE.

Analyses were also performed to examine specific a priori clinical-serologic associations. The power of these analyses are limited due to small numbers of cases but no associations could be demonstrated between lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin and anti-β2-GPI antibodies with cerebrovascular disease, seizure disorders, demyelinating syndrome or movement disorder. Similarly there was no demonstrable association between anti-NR2 antibodies with mood disorder or cognitive dysfunction.

Seven patients had psychosis which was attributed to SLE. This attribution was made in 3 patients using model A and in an additional 4 patients using model B. Two of the 3 patients in model A and 1 of the 4 patients in model B had anti-ribosomal P antibodies. The latter patient was not included under model A due to the fact that corticosteroids were identified as a potential contributing factor to the patient’s psychosis and thus recognized as an “association” as per the ACR case definition for psychosis (26). While the frequency of anti-ribosomal P antibodies in patients with psychosis (model A) compared to patients with no NP events achieved statistical significance (P = 0.02), the inclusion of this latter patient as an NP model A event, achieves a significance level of P = 0.003. Although some caution must be exercised in interpreting this finding, it indicates the importance of psychosis in explaining the observed association of anti-ribosomal P antibodies with NP events attributed to SLE.

Discussion

Several autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms likely play a role in the pathogenesis of NP-SLE (8–11). Current data suggests that antiphospholipid antibodies as measured by lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin and anti-β2-GPI antibodies cause focal NP disease (e.g. stroke, seizures) by promoting intra-vascular thrombosis. In contrast, anti-ribosomal P and possibly anti-NR2 antibodies cause diffuse NP events (e.g. psychosis, depression, cognitive impairment) through a direct effect on neuronal cells. A critical factor for the second group of autoantibodies is the ability to directly access neuronal cells either through the intra-thecal production of autoantibodies or their passage from the circulation across a permeablilized blood-brain-barrier.

The most direct evidence supporting the autoantibody hypothesis of NP-SLE is derived from studies of animal models (12–16) but the evidence from human studies is frequently conflicting or inconclusive (17–21). This may be due in part to methodological difficulties such as selection of patients for study, a lack of rigor in the characterization of NP events and inter-laboratory differences in assay technique. Thus we constituted an international disease inception cohort of SLE patients utilizing a standardized approach for the characterization of NP events and determining their attribution. Our primary objective was to examine the association between a panel of specific autoantibodies and NP-SLE events occurring around the time of diagnosis of SLE. In our data, only anti-ribosomal P antibodies provided any evidence of an association with NP events attributed to SLE.

The measurement of autoantibodies of interest to NP-SLE was performed in a single centre with expertise in autoantibody detection in order to avoid variability in laboratory methodology. In general the prevalence of autoantibodies was lower than that reported in other lupus cohorts. Thus, the frequency of lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, anti-β2-GPI, anti-ribosomal P and anti-NR2 antibodies was 18%, 18%, 16%, 8% and 19% respectively, which is lower than that reported in previous studies of SLE patients where, for example, the prevalence was 34% (30), 44% (30), 20% (31), 17% (20) and 35% (19), respectively. However, ours is the first study to measure this complete panel of autoantibodies in a disease inception cohort which in combination with our efforts to minimize non-specific antibody binding is probably the explanation for the lower prevalence rates. With further followup the frequency of all autoantibodies in this patient cohort will very likely increase in keeping with previous longitudinal studies of SLE patients(32).

In the present study only anti-ribosomal P antibodies demonstrated any association with NP events attributed to SLE. The decision rules for attribution were clinically based and did not include information of autoantibody status. Thus, the highest frequency of anti-ribosomal P autoantibodies occurred in patients with NP events attributed to SLE, as defined using the most stringent of the attribution rules. These findings provide support for the possible role of anti-ribosomal P antibodies in NP-SLE. However, in keeping with the findings of a recent metanalysis (21) the low sensitivity limits the utility of the test which cannot be used in isolation as a reliable biomarker to determine the attribution of NP events. None of the other autoantibodies demonstrated an association with NP-SLE and in particular anticardiolipin antibodies demonstrated a negative association with NP-SLE although this did not reach statistical significance.

There are a number of limitations to our study. First, due to the lack of specificity of most of the NP events, composite arbitrary decision rules were developed as previously described (6). However, in the case of anti-ribosomal P antibody which was the only autoantibody for which there was a significant association with NP-SLE events, the pattern of the association indicated an effect in favour of NP events attributed to SLE. Second, although our disease inception cohort was of reasonable size, many of the individual NP events attributed to SLE were infrequent which limited the statistical power of the analysis. Third, as autoantibodies were determined at a single time point it is possible the some patients with an evanescent pattern of autoantibody production could have been overlooked. Finally, the study did not address whether autoantibodies were present within the intra-thecal space by sampling cerebrospinal fluid or using a circulating biomarker of blood-brain-barrier permeability.

Despite these limitations our study provides novel information on the prevalence of this unique panel of autoantibodies in an international inception cohort and found an association between NP-SLE events with anti-ribosomal P antibodies. Future studies will determine the reproducibility of this finding in an expanded disease inception cohort and whether any of these autoantibodies predict the subsequent development or course of NP events over time.

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

J.G. Hanly (Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant MOP-57752, Capital Health Research Fund), M.B. Urowitz (Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant MOP-49529, Lupus Foundation of Ontario, Ontario Lupus Association, Lupus UK, Lupus Foundation of America, Lupus Alliance Western New York, Conn Smythe Foundation, Tolfo Family (Toronto), C. Gordon (Lupus UK, arthritis research campaign, Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility in Birmingham, UK), S.C. Bae (Brain Korea 21 Program), A. Clarke (Fonds de la recherche en sante de Quebec National Scholar, Singer Family Fund for Lupus Research), S. Bernatsky (Canadian Institutes of Health Research Junior Investigator Award; Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québéc Jeune Chercheure; Canadian Arthritis Network Scholar Award; McGill University Health Centre Research Institute), D. Gladman (Canadian Institutes of Health Research), P.R. Fortin (The Arthritis Society/Institute of Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis Investigator award, Arthritis Centre of Excellence), R. Ramsey-Goldman (National Institutes of Health research grants M01-RR00048; K24 AR02318; P60 AR 48098), G. Sturfelt and O. Nived (Swedish Medical Research council grant 13489), G.S Alarcón(University of Alabama at Birmingham, grant P60AR48095), M. Petri (Hopkins Lupus Cohort grant AR 43727, Johns Hopkins University General Clinical Research Center grant MO1 RR00052).

References

- 1.Ainiala H, Hietaharju A, Loukkola J, et al. Validity of the new American College of Rheumatology criteria for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes: a population-based evaluation. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(5):419–23. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200110)45:5<419::aid-art360>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brey RL, Holliday SL, Saklad AR, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes in lupus: prevalence using standardized definitions. Neurology. 2002;58(8):1214–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.8.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanly JG, McCurdy G, Fougere L, Douglas JA, Thompson K. Neuropsychiatric events in systemic lupus erythematosus: attribution and clinical significance. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(11):2156–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanna G, Bertolaccini ML, Cuadrado MJ, Laing H, Mathieu A, Hughes GR. Neuropsychiatric manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence and association with antiphospholipid antibodies. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(5):985–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sibbitt WL, Jr, Brandt JR, Johnson CR, et al. The incidence and prevalence of neuropsychiatric syndromes in pediatric onset systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(7):1536–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Sanchez-Guerrero J, et al. Neuropsychiatric events at the time of diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus: an international inception cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(1):265–73. doi: 10.1002/art.22305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernatsky S, Clarke A, Gladman DD, et al. Mortality related to cerebrovascular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2006;15(12):835–9. doi: 10.1177/0961203306073133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanly JG. Neuropsychiatric lupus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2005;31(2):273–98. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermosillo-Romo D, Brey RL. Neuropsychiatric involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2002;4(4):337–44. doi: 10.1007/s11926-002-0043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamond B, Volpe B. On the track of neuropsychiatric lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(10):2710–2. doi: 10.1002/art.11278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senecal JL, Raymond Y. The pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus: a disease in search of autoantibodies, or autoantibodies in search of a disease? J Rheumatol. 2004;31(11):2093–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeGiorgio LA, Konstantinov KN, Lee SC, Hardin JA, Volpe BT, Diamond B. A subset of lupus anti-DNA antibodies cross-reacts with the NR2 glutamate receptor in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Med. 2001;7(11):1189–93. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman J, Cohen-Armon M, Shoenfeld Y, Korczyn AD. Antiphospholipid antibodies permeabilize and depolarize brain synaptoneurosomes. Lupus. 1999;8(2):127–33. doi: 10.1191/096120399678847524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kowal C, DeGiorgio LA, Nakaoka T, et al. Cognition and immunity; antibody impairs memory. Immunity. 2004;21(2):179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzav A, Solodeev I, Brodsky O, et al. Induction of autoimmune depression in mice by anti-ribosomal P antibodies via the limbic system. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(3):938–48. doi: 10.1002/art.22419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katzav A, Chapman J, Shoenfeld Y. CNS dysfunction in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus. 2003;12(12):903–7. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu500oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denburg SD, Denburg JA. Cognitive dysfunction and antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2003;12(12):883–90. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu497oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omdal R, Brokstad K, Waterloo K, Koldingsnes W, Jonsson R, Mellgren SI. Neuropsychiatric disturbances in SLE are associated with antibodies against NMDA receptors. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12(5):392–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanly JG, Robichaud J, Fisk JD. Anti-NR2 glutamate receptor antibodies and cognitive function in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(8):1553–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnett FC, Reveille JD, Moutsopoulos HM, Georgescu L, Elkon KB. Ribosomal P autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Frequencies in different ethnic groups and clinical and immunogenetic associations. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(11):1833–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karassa FB, Afeltra A, Ambrozic A, et al. Accuracy of anti-ribosomal P protein antibody testing for the diagnosis of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: an international meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):312–24. doi: 10.1002/art.21539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isenberg D, Ramsey-Goldman R. Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Group--onwards and upwards? Lupus. 2006;15(9):606–7. doi: 10.1177/0961203306071868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35(6):630–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gladman D, Ginzler E, Goldsmith C, et al. The development and initial validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(3):363–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(4):599–608. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<599::AID-ANR2>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merrill JT, Zhang HW, Shen C, et al. Enhancement of protein S anticoagulant function by beta2-glycoprotein I, a major target antigen of antiphospholipid antibodies: beta2-glycoprotein I interferes with binding of protein S to its plasma inhibitor, C4b-bindingprotein. Thromb Haemost. 1999;81(5):748–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merrill JT, Shen C, Gugnani M, Lahita RG, Mongey AB. High prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in patients taking procainamide. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(6):1083–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erkan D, Zhang HW, Shriky RC, Merrill JT. Dual antibody reactivity to beta2-glycoprotein I and protein S: increased association with thrombotic events in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus. 2002;11(4):215–20. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu178oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Love PE, Santoro SA. Antiphospholipid antibodies: anticardiolipin and the lupus anticoagulant in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in non-SLE disorders. Prevalence and clinical significance. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(9):682–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-9-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laskin CA, Clark CA, Spitzer KA. Antiphospholipid syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus: is the whole greater than the sum of its parts? Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2005;31(2):255–72. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arbuckle MR, McClain MT, Rubertone MV, et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(16):1526–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]