Abstract

Objective

Experimental studies have reported potential benefit of glucagon-like peptide-1(GLP-1) receptor agonists in preventing diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN). We therefore performed a proof-of-concept pilot study to evaluate the effect of exenatide, a GLP-1 agonist, on measures of DPN and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN) in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Research Design and Methods

Forty-six T2D subjects (age 54±10 years, diabetes duration 8 ± 5 years,HbA1c 8.2 ±1.3%) with mild to moderate DPN at baseline were randomized to receive either twice daily exenatide (n=22) or daily insulin glargine (n= 24). The subjects, with similar HbA1c levels, were followed for 18 months. The primary end point was the prevalence of confirmed clinical neuropathy (CCN). Changes in measures of CAN, other measures of small fiber neuropathy such as intra-epidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD), and quality of life were also analyzed.

Results

Glucose control was similar in both groups during the study. There were no statistically significant treatment group differences in the prevalence of CCN, IENFD, measures of CAN, nerve conductions studies, or quality of life indices.

Conclusions

In this pilot study of patients with T2D and mild to moderate DPN, 18 months of exenatide treatment had no significant effect on measures of neuropathy compared with glargine treatment.

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) affects nearly two-thirds of patients with diabetes and is a major cause of poor quality of life (1) Despite the proven efficacy of intensive glucose control in delaying or preventing DPN and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN) in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D)(2-4), equal efficacy has not been shown in type 2 diabetes (T2D) (5; 6). Furthermore, patients may develop DPN and CAN despite good glucose control (5).

Among the therapeutic options available for glycemic control in subjects with T2D, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are known to stimulate insulin secretion in response to hyperglycemia, delay gastric emptying, and suppress hepatic glucose release, thus providing significant blood glucose-lowering effects with little increased risk for hypoglycemia or weight gain (7; 8). Exenatide, a synthetic form of exendin-4 and the first GLP-1 receptor agonist approved in the US, is an effective glucose-lowering agent in patients with T2D (9).

Experimental evidence indicates that exenatide may also have direct neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects which are independent of its glycemic effects (10-14). For instance, GLP-1 receptors are present on dorsal root ganglia (DRG) sensory neurons of diabetic and nondiabetic mice, sciatic nerve axons and Schwann cells, and exendin-4 increases neurite outgrowth of adult sensory neurons in vitro (10). In T1D mice with established neuropathy treated with either exendin-4 or high-dose insulin for 4 weeks, exendin-4 improved both sensory electrophysiology and measures of current perception threshold with no effect on hyperglycemia, while high-dose insulin reversed hyperglycemia but only partly improved thermal sensation and epidermal innervation and had no effect on electrophysiological abnormalities (10). However, short-term exendin-4 treatment was less effective in T2D mice with neuropathy (10). In another study, 4-week exendin-4 treatment in mice with streptozotocin-induced T1D promoted significant neurite outgrowth of DRG neurons and ameliorated the loss of intraepidermal nerve fibers (IENF) (11). It was suggested that these effects were independent of glycemia and possibly mediated via GLP-1 receptor activation and through anti-apoptosis and cAMP signaling pathways (10, 11), or via stimulating neuronal differentiation in human cells (12). GLP-1 has been also shown to modulate autonomic activity and induce changes in haemodynamic variables. For instance, Griffioen et al. showed that both acute and chronic central administration of exendin-4 increased the resting heart rate and reduced measures of heart rate variability (HRV) in mice, either by altering the inhibition of neurotransmission to cardiac vagal neurons (13) or up regulation of sympathetic outflow and downstream activation of cardiovascular responses (14).

Based on the above experimental evidence, we hypothesized that GLP-1 receptor agonists may have potential beneficial effects on measures of DPN and CAN in humans, something that has not been systematically evaluated. We therefore conducted a pilot, proof-of-concept, randomized, open-label clinical trial to evaluate the effects of exenatide on measures of DPN and CAN in subjects with T2D.

Research Design and Methods

Study Design

This single center, proof-of-concept-pilot, open-label randomized, controlled trial (NCT00855439) was conducted at the University of Michigan between July 2008 and June 2014. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All subjects signed a written consent document.

Study participants

Subjects were eligible to enroll if they were between 18 and 70 years old, had T2D with a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) > 7% and fasting blood glucose > 140 mg/dl, had followed a prior stable glucose lowering regimen that did not include insulin or a GLP-1 receptor agonist, had no known contraindications to treatment with either exenatide or insulin glargine based on FDA prescribing guidelines, and presented with mild-to-moderate DPN as defined by a score of 6 or more on the Michigan Diabetes Neuropathy Scale (MDNS), a validated scale for evaluation of diabetic neuropathy (15) described below in Methods.

Excluded were subjects with a history of kidney, pancreas, or cardiac transplantation, neuropathy independent of diabetes, or any condition other than diabetes associated with neuropathy (e.g. hepatitis C, end stage renal disease, lupus), any lower extremity amputation or severe deformity of lower extremity, HbA1c > 10%, participation in an experimental medication trial within 3 months of starting this study, undergoing therapy for malignant disease other than basal- or squamous cell carcinoma, requiring long-term glucocorticoid therapy, inability or unwillingness to comply with the protocol, and nursing mothers or pregnant women.

Intervention

Subjects were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either exenatide (n = 22) or insulin glargine (n = 24) targeting similar levels of glucose control as documented by hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). Exenatide was initiated at a fixed dose of 5 μg twice daily for 4 weeks and then increased to 10 μg twice daily for the remainder of the study if tolerated. Subjects who did not tolerate the 10 μg dose resumed the reduced 5 μg dose for the duration of the study. Insulin glargine was initiated with 10 units daily and titrated in 2-unit increments to achieve a fasting blood glucose target level of 5.6 mmol/L (100 mg/dL) without recurrent or severe hypoglycemia. The dose of any prior oral agents remained fixed, unless clinical judgment dictated they should be altered to optimize blood glucose control.

Assessment of Neuropathy

DPN was assessed at baseline and at 12- and 18-month follow-up visits with assessment of symptoms and signs of DPN by a board certified neurologist as described (16), nerve conduction studies of the median (sensory and motor), peroneal motor and sural sensory nerves using a standard protocol, which included replication of baseline limb temperatures at 12 and 18 month assessments (16), and quantitative sensory testing for vibration perception (VPT) using the Vibratron II device (Physitemp Instruments, Inc.) as described (17).

The rate of IENF reinnervation after capsaicin denervation was used as an exploratory measure of small fiber neuropathy and obtained as described (18). Briefly, a baseline skin biopsy was obtained from the distal thigh in a subset of consenting T2D subjects (exenatide = 9, glargine = 11). Capsaicin was applied as a 1% topical cream and the site was covered with an occlusive dressing for 48 hours. Additional skin biopsies were obtained at 48 hours (to confirm denervation) and at 6 and 12 months of treatment (3 months and 9 months post-capsaicin respectively). All skin biopsies were obtained in a standardized fashion by a single examiner, and all IENFD evaluations were analyzed in a blinded manner by Therapath, Inc (New York, NY). In addition, the MDNS was performed at screening to confirmed eligibility as described (15). Briefly the MDNS is a 46-point exam that includes testing for vibration, 10-gram monofilament pressure, pin sensation at the great toe, deep tendon reflexes at knee and ankle, and strength. For all evaluations, 1 point was given for reduction on either side, or 2 points when the response was absent, except for pin sensation where 2 points per side were assigned if sharp sensation was absent.

CAN was evaluated at baseline, 12 months, and 18 months with the gold-standard cardiovascular reflex tests (CARTs) (the deep breathing test and the Valsalva maneuver) (19) and measures of HRV obtained during a 5-minute rest and during CARTs using the ANX 3.1 (ANSAR Inc., Philadelphia, PA). Subjects were required to fast for 8 hours and to abstain from tobacco, caffeine, and alcohol prior to testing. Blood glucose was obtained prior to testing and testing was rescheduled in the presence of hypoglycemia. Testing was performed with the subjects in a supine position, with the head of the bed elevated no more than 30 degrees. Subjects with demonstrable atrial fibrillation (n = 3 glargine) and subjects with a pacemaker (n= 1 glargine) were excluded from the CART analysis.

Neuropathy Specific Quality of Life was evaluated with the Neuropathy Specific Quality of Life Measure (NeuroQOL)(20) at baseline, and at 12 and 18 months of follow up. This self-administered, 39-item validated survey that includes: the overall impact of foot problems on quality of life, overall quality of life and 6 other primary domains: 1) painful symptoms and paresthesias; 2) reduced/lost feeling in the feet; 3) diffuse sensory motor symptoms; 4) limitations in daily activities; 5) interpersonal problems; and 6) emotional burden. For the foot problem-specific item, lower scores indicate less negative impact of foot problems on quality of life, and for overall quality of life higher scores indicate worse quality of life. Within each domain, lower scores indicate worse symptoms or greater adverse effect on quality of life (20).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of the study was the prevalence of confirmed clinical neuropathy (CCN) over 18 months. CCN was defined by a composite score comprised of at least two positive responses among symptoms, sensory signs, or absent or hypoactive reflexes consistent with a distal symmetrical polyneuropathy (16), and at least one abnormal nerve conduction study result in two anatomically distinct nerves, e.g. the sural sensory and peroneal motor nerves (defined as a amplitude < 5 μV and a conduction velocity < 40 m/sec for the sural nerve and an amplitude < 2.5 μV and a conduction velocity < 40 m/sec for the peroneal nerve).

Secondary outcomes included: a) individual electrophysiology measures assessed as continuous variables: b) VPT; c) changes in clinical neuropathy (defined as two or more positive findings among symptoms, signs, and reduced or absent deep tendon reflexes); d) changes in IENFD after capsaicin denervation; e) changes in the following measures of CAN: expiration:inspiration (E:I) ratio, Valsalva ratio, resting heart rate, standard deviation of normal RR interval (SDNN), very low frequency power (VLF), low frequency power (LF), and high frequency power (HF) and changes in quality of life measures.

Power

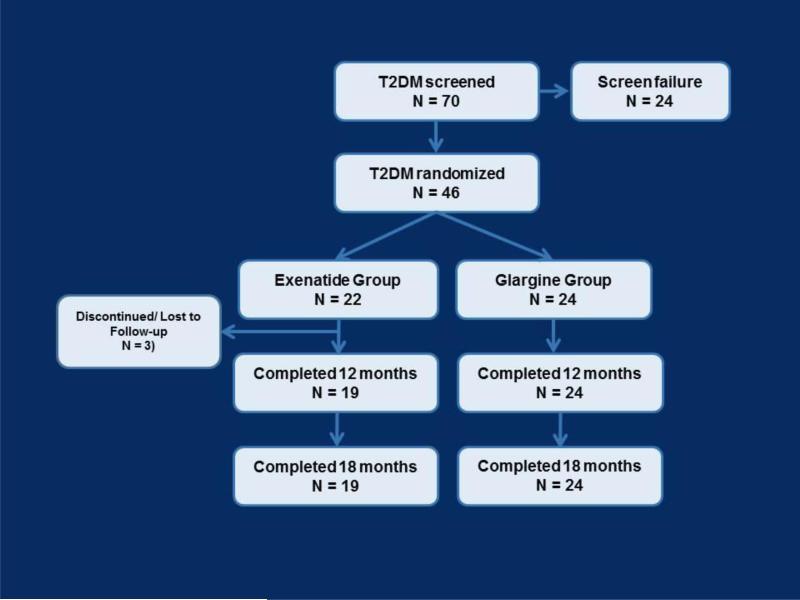

Seventy people meeting the study inclusion and exclusion criteria by preliminary screening were evaluated for inclusion in the study and 46 subjects were randomized into the trial (Figure 1). As a result, there was 90% power to identify a change of one standard deviation (SD) between treatment groups or 80% power to identify a change of 0.87 SDs in the continuous measures using a 2-tailed t-test with a 5% level of significance. With the sample sizes in this study, there was 80% power to identify a difference in the rates of CCN at the end of the study of 40%, i.e., 30% vs. 70%, using a 2-tailed test with a 5% level of significance.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were done using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC). Differences in continuous and categorical variables between the exenatide and glargine groups at baseline and change from baseline to 18 months were examined by the two sample t-test (for normally distributed variables) or Wilcoxon rank sum test(for non-normally distributed variables) and chi-square test, respectively. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD)

Results

At baseline, there were no differences in the mean age of the subjects (51±13 years for exenatide, and 54 ± 9 years for glargine), gender, race, diabetes duration, body mass index (BMI), and glycemic control (p=NS for all) (Table 1). Consistent with the inclusion criteria, all subjects presented with mild-to-moderate neuropathy, as illustrated by similar MDNS scores in both groups at baseline (22 ±11 and 24 ± 11, p=NS in the exenatide and glargine groups respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of type 2 diabetes subjects randomized to the Exenatide or Glargine treatment groups

| Variable | Exenatide (N= 22) | Glargine (N= 24) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 9 (41%) | 11 (46%) | 0.73 |

| Race | |||

| White, n (%) | 19 (86%) | 21 (87%) | 0.56 |

| Age, years | 51 ± 13 | 54 ± 9 | 0.43 |

| Diabetes Duration, years | 8 ± 5 | 7 ± 4 | 0.98 |

| Height, cm | 172 ±8 | 172 ± 11 | 0.8 |

| Weight, kg | 107 ± 13 | 110 ± 21 | 0.6 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 35 ± 3 | 37 ± 6 | 0.2 |

| Baseline HbA1c,% mmol/mol | 8.2 ± 1.1 66± 2 |

8.4 ± 1.4 68± 2 |

0.56 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 124 ± 14 | 130 ± 15 | 0.23 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 73 ± 9 | 74 ± 9 | 0.59 |

| MDNS score | 11 ± 5 | 11 ± 5 | |

| Clinical Neuropathy× | 0.54 | ||

| Definite | 19(86%) | 21(88%) | |

| Possible | 3(14%) | 2(8%) | |

| None | 0(0%) | 1(4%) | |

| Abnormal Nerve Conduction Study measures | 0.10 | ||

| 0 | 5(23%) | 0(0%) | |

| 1 | 2(9%) | 3(12%) | |

| 2 | 6(27%) | 10(42%) | |

| 3 | 9(41%) | 11(46%) | |

| Confirmed clinical neuropathy¥ | 0.4028 | ||

| Yes | 14(67%) | 18(75%) | |

| No | 8(36%) | 6(25%) | |

| Symptoms of DPN, n (%) | 21(96%) | 22(92%) | 0.60 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and n(%) for categorical variables.

BMI: body mass index, MDNS: Michigan Diabetic Neuropathy Scale; DPN: diabetic peripheral neuropathy, DTR : deep tendon reflex.

Based on focused neurological examination. Definite defined as two or more positive findings among symptoms, signs, reduced or absent deep tendon reflexes consistent with distal symmetrical peripheral neuropathy. Possible defined by one positive finding.

± Number of abnormal nerves based on any electrodiagnositic abnormality of sural sensory, peroneal motor, median sensory or median motor nerves.

Confirmed clinical neuropathy defined by presence of definite clinical neuropathy plus at least one abnormal nerve attributes in two anatomically distinct nerves (of sural, peroneal or median).

The prevalence of CCN was also similar (67% among subjects randomized to exenatide and 75% among subjects randomized to glargine). DPN symptoms were present in 21 (96%) subjects in the exenatide group and 22 (92%) subjects in the glargine group (Table 1). The exenatide and glargine groups also did not differ in any of the electrophysiological measures median (motor and sensory), sural, and peroneal nerves, or in measures of CAN (Table 2).

Table 2.

Nerve conduction and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy measures at baseline, 12 and 18 months of follow-up

| Variable | Baseline | P | 12 months | P | 18 months | P | Difference: Baseline to 18 months | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Motor Amplitude (mV) | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 9.9±3.6 | 0.09 | 9.1±3.4 | 0.29 | 9.2±3.6 | 0.12 | −0.2±1.8 | 0.49 |

| Glargine | 8.3±2.9 | 7.9 ±3.1 | 7.7 ±2.5 | −0.5±2.6 | ||||

| Median Motor CV (m/sec) | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 49.8±4.6 | 0.63 | 48.7±4.8 | 0.55 | 49.4±5.2 | 0.65 | −0.4±4.6 | 0.37 |

| Glargine | 50.5±4.4 | 49.6±4.7 | 48.5±6.9 | −1.9±5.7 | ||||

| Median Motor F Response Latency (msec) | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 30.9±2.7 | 0.85 | 30.6±2.3 | 0.59 | 31.6±3.2 | 0.71 | 0.5±2.4 | 0.94 |

| Glargine | 31.1±2.8 | 31.1±3.2 | 31.2±3.5 | 0.2±1.7 | ||||

| Median Sensory Amplitude (μV) | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 15.5±12.7 | 0.51 | 15.0±10.9 | 0.44 | 14.3±10.7 | 0.59 | −1.6±5.8 | 0.71 |

| Glargine | 13.3±8.8 | 12.6±8.0 | 12.6±9.1 | −0.7±5.2 | ||||

| Median Sensory CV (m/sec) | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 45.0±12.5 | 0.27 | 43.8±13.6 | 0.57 | 44.9±13.6 | 0.54 | −0.03±9.5 | 0.62 |

| Glargine | 41.1±11.2 | 41.7±10.2 | 42.5±11.1 | 1.3±5.8 | ||||

| Peroneal Motor Amplitude (mV) | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 3.9±1.9 | 0.30 | 3.7±1.9 | 0.82 | 3.8±1.8 | 0.59 | −0.3±1.6 | 0.29 |

| Glargine | 3.3±2.3 | 3.9±2.7 | 3.5±2.4 | 0.2±1.5 | ||||

| Peroneal Motor CV (m/sec) | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 40.4±4.6 | 0.19 | 39.6±5.5 | 0.20 | 39.9±6.0 | 0.39 | −0.3±4.4 | 0.97 |

| Glargine | 38.2±6.2 | 37.4±5.6 | 38.4±5.9 | 0.1±4.8 | ||||

| Peroneal Motor F Response Latency (msec) | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 53.0±13.2 | 0.03 | 58.3±7.6 | 0.94 | 55.7±6.8 | 0.37 | 3.2±14.4 | 0.14 |

| Glargine | 60.2±7.3 | 58.1±9.7 | 57.7±8.2 | −2.5±8.9 | ||||

| Sural Sensory Amplitude (μV) | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 7.0±7.0 | 0.27 | 6.2±7.5 | 0.76 | 5.8±6.4 | 0.46 | −1.5±3.0 | 0.35 |

| Glargine | 5.0±4.8 | 5.6±5.6 | 4.52±4.4 | −0.5±2.6 | ||||

| Sural Sensory CV (m/sec) | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 41.0±6.7 | 0.98 | 39.2±6.2 | 0.30 | 39.2±5.3 | 0.84 | −1.4±5.6 | 0.39 |

| Glargine | 40.9±7.1 | 41.7±9.2 | 38.8±5.6 | −2.0±4.7 | ||||

| HR, beat/min | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 70±12 | 0.21 | 69±10 | 0.11 | 70±9 | 0.07 | 1±12 | 0.80 |

| Glargine | 74±8 | 74±9 | 77±10 | 3±8 | ||||

| SDNN, msec | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 43±25 | 0.59 | 43±32 | 0.12 | 40±26 | 0.80 | −1.1±28 | 0.68 |

| Glargine | 50±48 | 30±13 | 38±24 | −12.1±53 | ||||

| RMSSD, msec | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 28±21 | 0.83 | 34±35 | 0.03 | 32±36 | 0.63 | 4.9±40.2 | 0.56 |

| Glargine | 31±40 | 15±6 | 27±21 | −3.3±44.4 | ||||

| LF/HF ratio | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 4.5±3.8 | 0.11 | 4.8±4.6 | 0.29 | 4.9±5.7 | 0.93 | 0.8±5.1 | 0.10 |

| Glargine | 11.1±17.2 | 6.7±6.7 | 5.0±3.6 | −6.0±17.3 | ||||

| Valsalva ratio | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 1.4±0.5 | 0.98 | 1.4±0.3 | 0.91 | 1.3±0.2 | 0.13 | −0.4±11 | 0.63 |

| Glargine | 1.3±0.3 | 1.4±0.3 | 1.4 ±0.4 | −0.19±0.9 | ||||

| E/I ratio | ||||||||

| Exenatide | 1.2±0.3 | 0.99 | 1.1±0.1 | 0.07 | 1.1 ±0.1 | 0.13 | −0.06±0.3 | 0.21 |

| Glargine | 1.2±0.3 | 1.1±0.03 | 1.1±0.04 | −0.09±0.27 | ||||

Data are presented as mean ±SD)

HR: heart rate, SDNN: standard deviation of normal RR interval, RMSSD: root mean square difference of successive RR interval, LF: low frequency power, HF: high frequency power, E:I ratio: expiration inspiration ratio.

Effects of treatment

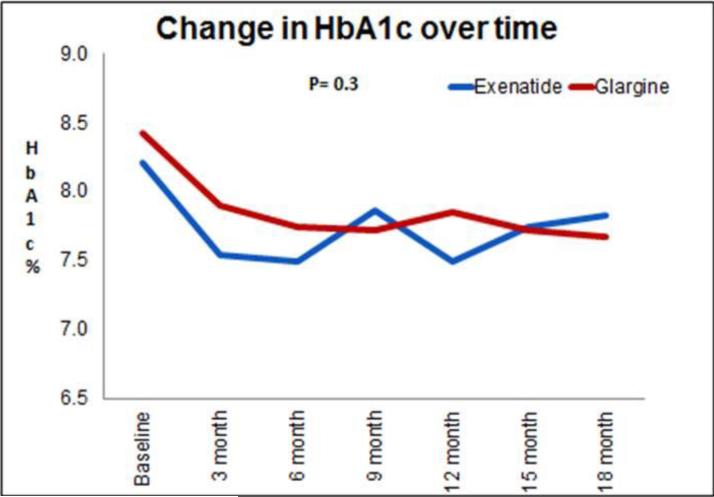

All 24 subjects randomized to the glargine group and 19 of 22 subjects randomized to the exenatide group completed the 18-month follow-up visit (Figure 1). Mean HbA1c improved in both groups at 12 and 18 months of follow-up relative to baseline, and there were no statistically significant differences in HbA1c between the exenatide- and glargine-treated groups at any time (P=0.3)(Figure 2). At 18 months the mean dose in the exenatide group was 16±7 μg /day and 38±28 units/day in the glargine group. Participants in the exenatide group experienced on average 3 kg of weight loss after first 12 months of trial, compared with an average of 2 kg weight gain in the glargine group (P=0.01). However these differences were attenuated at 18 months, to a 2 kg weight loss in the exenatide group and a 1 kg weight gain in the glargine group (P=0.07).

Figure 2.

Changes in the HbA1c levels from baseline to end of study in the exenatide (blue line) and glargine (red line) groups

There were no significant differences between exenatide and glargine groups in the primary endpoint at 12 or 18 months. In addition, no differences were observed between groups at 12 and 18 months in any of the electrophysiological measures (amplitude, conduction velocity, or F response latency) of median (motor and sensory), sural, and peroneal nerves (Table 2).

There were no significant differences in the overall IENFD at 3 and 12 months after capsaicin denervation between the exenatide and glargine groups, but there was significant regeneration in the glargine group at 12 months (improvement of 4.6±2.9 fibers/mm, P=0.002), which was less in the exenatide group (improvement of 2.1±3.5 fibers/mm at 12 months, P=0.06). This group difference accounted for a marginally higher regeneration rate with glargine (Figure 3). There were no differences in baseline characteristics among the participants who agreed to this evaluation and the entire cohort.

Figure 3.

Changes in intraepidermal nerve fiber density in the exenatide (blue line) and glargine (red line) groups

Similar to the observations on DPN measures, there was no significant effect of exenatide on any measures of CAN at 12 or 18 months of follow-up compared with glargine (Table 2). In addition, there was a non-significant group difference in resting heart rate, tending to be lower in subjects assigned to exenatide compared with glargine (70 vs. 74 bpm respectively, P=0.21).

No group differences were observed over 18 months in either the NeuroQOL scores or overall global quality of life scores. Similar scores between groups were also observed when assessing the differences in the 6 specific domains (painful symptoms and paresthesias, symptoms of reduced/lost feeling in the feet, diffuse sensory motor symptoms, limitations in daily activities, interpersonal problems and emotional burden) (Appendix Table 2).

Adverse events

During the course of the study, 82 adverse events (AEs) were reported; 26 events by 12 exenatide group subjects (1 to 4 events per subject) and 56 events by 20 glargine group subjects (1 to 6 events per subject). Among the events reported by exenatide-treated subjects, 9 events (6 subjects) met serious adverse event criteria, with one of these categorized as possibly related to treatment (hospitalization for severe diverticulitis occurring within three months of starting exenatide) and another considered unlikely related (lipaemia after 12 months of treatment with exenatide, leading to an evaluation that revealed a neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas, which was surgically removed and determined to be benign). The remaining serious AEs were categorized as unrelated to study treatment or study participation. A summary of all AEs is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Adverse events reported by subjects during the study.

| Event | Exenatide (N= 22) | Glargine (N = 24) |

|---|---|---|

| Accident/Trauma | 1 | 5 |

| Fracture left leg | 0 | 1 |

| Fracture, Right Foot | 0 | 1 |

| Jones fracture left foot | 0 | 1 |

| Laceration finger | 0 | 1 |

| MVA cervical fracture | 1 | 0 |

| Fracture wrist | 0 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular | 2 | 7 |

| CABG, 2 vessel | 0 | 1 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 1 |

| Bilateral ankle cellulitis | 0 | 1 |

| Chest pain | 0 | 1 |

| CHF exacerbation | 1 | 1 |

| NSTEMI | 0 | 1 |

| Pedal edema | 1 | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 1 |

| Dental | 2 | 0 |

| Bleeding post dental work | 1 | 0 |

| Dental infection | 1 | 0 |

| Endocrine/Metabolic | 5 | 1 |

| Severe hypoglycemia | 0 | 1 |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 1 | 0 |

| Serum creatinine increase | 1 | 0 |

| Hypothyroid | 1 | 0 |

| Thyroidectomy | 1 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | 6 | 4 |

| Cholelithiasis | 1 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 0 |

| Diverticulitis | 1 | 1 |

| Epigastric pain nausea | 0 | 1 |

| Lipasemia | 1 | 0 |

| Incarcerated ventral hernia | 0 | 1 |

| Intractable N/V with fever | 0 | 1 |

| Nausea | 2 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 | 0 |

| Persistent nausea | 1 | 0 |

| Hematologic | 0 | 1 |

| Thalassemia B Minor | 0 | 1 |

| Infection skin or soft tissue | 2 | 7 |

| Toe Infection | 1 | 1 |

| Infection, skin | 0 | 1 |

| LE cellulitis | 0 | 2 |

| Left athletes foot | 1 | 0 |

| Left toe cellulitis | 0 | 2 |

| Plantar ulcer and cellulitis | 0 | 1 |

| Mood/Psychological | 0 | 2 |

| Depression | 0 | 2 |

| Musculoskeletal | 1 | 5 |

| Back pain | 1 | 0 |

| Ganglion cyst right knee | 0 | 1 |

| Knee pain | 0 | 1 |

| Plantar fasciitis | 0 | 2 |

| Right knee pain | 0 | 1 |

| Neurological | 0 | 6 |

| CTS | 0 | 1 |

| Dizziness | 0 | 1 |

| Headache after fall | 0 | 1 |

| Left arm numbness | 0 | 1 |

| Lightheadedness | 0 | 1 |

| Neuropathic pain, worsened | 0 | 1 |

| Pregnancy | 1 | 0 |

| Renal | 1 | 0 |

| Nephrolithiasis | 1 | |

| Respiratory | 3 | 10 |

| Asthma exacerbation | 0 | 1 |

| Cold | 1 | 0 |

| Hospitalization - bronchitis | 0 | 2 |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | 0 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 | 0 |

| Sinusitis | 0 | 1 |

| Status asthmaticus | 0 | 1 |

| strep throat/ear infection | 0 | 1 |

| Upper Respiratory tract Infection | 1 | 2 |

| Skin/Dermatologic | 1 | 0 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 | 0 |

| Surgical Procedure | 0 | 6 |

| Ingrown toenail extraction -bilaterally | 0 | 1 |

| Left toe amputation | 0 | 1 |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 0 | 1 |

| Nasal septal repair | 0 | 1 |

| Gastric bypass | 0 | 1 |

| Scheduled surgery | 0 | 1 |

Discussion

In this proof of concept, pilot study, treatment with the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide did not reduce the prevalence of confirmed DPN over a period of 18 months of treatment, and did not affect electrophysiology or measures of small fiber neuropathy, such as CAN and IENFD, compared to insulin glargine. In addition, exenatide had no effect on symptoms or signs of DPN, or on measure of quality of life. We did not find treatment-group differences with regard to progression (or remission) of neuropathy, as determined by standardized neurologic-focused history and physical examination, nerve conduction measures, CAN measures, or NeuroQOL, in 46 subjects with T2D randomly assigned to 18 months of treatment with exenatide or insulin glargine. An exploratory objective examining change in IENFD in skin before and after capsaicin denervation in a subset of participants also did not reveal treatment group differences, although subjects assigned to glargine experienced more regeneration after capsaicin compared with subjects assigned to exenatide. We believe this is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of exenatide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, on measures of both small and large fiber neuropathy in subjects with T2D, using very comprehensive assessments.

Emerging experimental evidence discussed above and a small human study suggested potential beneficial effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists or dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors on measures of DPN via non-glycemic effects (10-14; 21-23). However, our trial, using multiple, sensitive and specific measures for both DPN and CAN, performed under standardized conditions, failed to show any potential beneficial effect of a GLP-1 receptor agonist on DPN, CAN or neuropathy-specific quality of life. Although the high prevalence of CCN at baseline may have biased the effects of the intervention, the parametric electrophysiology measures that were used appear very robust, showed expected deterioration in both treatment groups over the short study interval (an expected consequence of diabetes over time), providing strong evidence that the study intervention was not efficacious relative to the referent treatment. Although there was a trend for a potential benefit of glargine over exenatide on the exploratory but objective small fiber measure (IENF regeneration after capsaicin), this evaluation was available only in a small subgroup of participants.

In addition, no effects were observed on any of the measures of CAN evaluated. In this study exenatide treatment was not associated with an increase in heart rate from baseline, and heart rate tended to be lower in subjects assigned to exenatide compared with glargine, although this did not reach statistical significance (Table 2). The effects on heart rate observed in this study contrast, however, with those observed in the majority of human of trials that evaluated the glucose lowering effects of GLP-1 receptor analogs involving diabetic and/or obese subjects which all reported persistent increase in heart rate, usually associated with significant decreases in systolic blood pressure, which seems to occur before weight loss (24-26). Lastly, we did not find any significant differences in any of the NeuroQOL scores in the glargine or exenatide groups. This is somewhat in contrast with other studies that reported some benefit with insulin glargine on more general quality of life measures or treatment satisfaction (27-29) whereas the NeuroQOL specifically captures neuropathy-related quality of life measures.

The treatment of diabetic neuropathy continues to be challenging, with important consequences on patients ‘morbidity and quality of life. Intensive glycemic control is essential but insufficient to completely prevent onset or progression of diabetic neuropathy (5,30). Randomized clinical trials that have evaluated a variety of disease-modifying agents for DPN or CAN have been disappointing so far (31,32). This is possibly due to the complexity of the mechanisms involved in the development and progression of DPN and CAN, inclusion of study subjects with too advanced disease, or lack of standardization in the neuropathy measures used. Therefore, finding a successful therapy for this complication is timely. Recent animal studies have shown beneficial effects on measures of neuropathy with cell transplantation therapies, such as endothelial precursor cells, bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (33), yet these findings need to be confirmed in humans.

Our study has several strengths. All neuropathy measures used in this investigation were specifically chosen, as they have been well validated and considered to be highly sensitive and specific for use in evaluations of DPN or CAN (3; 4; 15; 20), and included also measures with direct impact on patients ‘quality of life. Furthermore, all evaluations were performed uniformly by the same study staff at each outcome assessment and in a standardized fashion, reducing the risk for variability in outcome measures. Finally, the study cohort was specifically selected to ensure uniformity between treatment groups.

Weaknesses of our study are the small sample size, the relatively short duration of the intervention when placed in perspective with the natural history of DPN and CAN (34), and the high prevalence of CCN at baseline, in spite of the relatively short duration of diabetes. However, higher than expected rates for diabetes complications, including neuropathy, were reported by others even in newly diagnosed patients with T2D (35) or in patients with impaired glucose tolerance (36) and metabolic syndrome (37). These complications are likely associated with several years of exposure to hyperglycemia prior to a formal diagnosis of diabetes, and the presence of multiple co-morbidities and risk factors including hypertension, hyperlipidemia and obesity among most T2D patient (38). Given the high prevalence of CCN at baseline, only treatments that promoted improvement, not prevention, could be identified, which further highlights the relevance of the secondary measures that were included in this study design (such as regeneration shown with skin biopsy). Despite the relatively short duration of diabetes, both the groups had a similar prevalence and severity of diabetic neuropathy at baseline which could potentially be due to structural changes which might have developed in the pre-diabetic stage and explain the functional changes observed.

In addition, due to the selected inclusion criterion for neuropathy, it is possible that the stage of DPN present in the study participants was too advanced as not to be amenable to an 18-month intervention. Participants were further required to meet all current prescribing guidelines for both medications, and be willing to accept random assignment to treatment with either medication, restricting the number of suitable candidates for the study. Because nerve fiber damage leads to loss of terminal nerve fibers and alters nerve conduction velocity and amplitude before the symptoms of DPN appear, we were unable to see significant changes in these parameters in our cohort. Lastly, treatment was not masked to participants or investigators, introducing some risk for bias at all levels of the study, although the investigators that participated in the main outcomes evaluations were masked to study group. The similarities of HbA1c in both groups throughout the entire study demonstrate that glucose control efforts were unbiased. This finding also further demonstrates, that although exenatide has no added neuroprotective benefit, as it had been hypothesized, it does offer a viable and highly effective therapeutic alternative to insulin in patients with T2D.

In conclusion, in this pilot, proof-of-concept study, exenatide was not superior to insulin glargine in preventing progression of DPN or CAN in patients with T2D at similar levels of glucose control. This is possibly associated with the complexity of the mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathies which could require an integrated approach targeting multiple mechanisms for successful outcomes over a relatively short duration of follow-up. Nevertheless, this study provides some important lessons regarding selection of subjects, study design, and difficulties in translating experimental observations to human trials which may be applied to the design of future neuropathy trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the study participants for their contribution to the advancement of the research.

This study was funded as an investigator initiated trial initially by Amylin Pharmaceuticals, LLC, and then by Eli Lilly and Company, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company and Astra-Zeneca. Additional support was received from the Clinical Core of the Michigan Diabetes Research Center (Grant Number P30DK020572) and the Methods and Measurement Core of the Michigan Center for Diabetes Translational Research (Grant Number P30DK092926) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and from the A Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00855439

Author Contributions: Dr. Pop-Busui had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Pop-Busui, Feldman, Albers, Brown

Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: Martin, Pop-Busui, Albers, Feldman, Brown, Jaiswal, Callaghan

Drafting of the manuscript: Jaiswal, Martin, Pop-Busui

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Pop-Busui, Albers, Feldman, Martin, Callaghan, Brown.

Statistical analysis: Brown, Jaiswal.

References

- 1.Tesfaye S, Boulton AJ, Dyck PJ, Freeman R, Horowitz M, Kempler P, Lauria G, Malik RA, Spallone V, Vinik A, Bernardi L, Valensi P. Diabetic neuropathies: update on definitions, diagnostic criteria, estimation of severity, and treatments. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2285–2293. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DCCT: The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DCCT: Effect of intensive diabetes treatment on nerve conduction in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:869–880. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DCCT: The effect of intensive diabetes therapy on measures of autonomic nervous system function in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). Diabetologia. 1998;41:416–423. doi: 10.1007/s001250050924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ang L, Jaiswal M, Martin C, Pop-Busui R. Glucose control and diabetic neuropathy: lessons from recent large clinical trials. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:528. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0528-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callaghan BC, Little AA, Feldman EL, Hughes RA. Enhanced glucose control for preventing and treating diabetic neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD007543. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007543.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baggio LL, Huang Q, Brown TJ, Drucker DJ. A recombinant human glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1-albumin protein (albugon) mimics peptidergic activation of GLP-1 receptor-dependent pathways coupled with satiety, gastrointestinal motility, and glucose homeostasis. Diabetes. 2004;53:2492–2500. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yusta B, Baggio LL, Estall JL, Koehler JA, Holland DP, Li H, Pipeleers D, Ling Z, Drucker DJ. GLP-1 receptor activation improves beta cell function and survival following induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 2006;4:391–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCormack PL. Exenatide twice daily: a review of its use in the management of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2014;74:325–351. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kan M, Guo G, Singh B, Singh V, Zochodne DW. Glucagon-like peptide 1, insulin, sensory neurons, and diabetic neuropathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:494–510. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182580673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Himeno T, Kamiya H, Naruse K, Harada N, Ozaki N, Seino Y, Shibata T, Kondo M, Kato J, Okawa T, Fukami A, Hamada Y, Inagaki N, Seino Y, Drucker DJ, Oiso Y, Nakamura J. Beneficial effects of exendin-4 on experimental polyneuropathy in diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2011;60(9):2397–406. doi: 10.2337/db10-1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luciani P, Deledda C, Benvenuti S, Cellai I, Squecco R, Monici M, Cialdai F, Luciani G, Danza G, Di Stefano C, Francini F, Peri A. Differentiating effects of the glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue exendin-4 in a human neuronal cell model. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2010;67:3711–3723. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0398-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffioen KJ, Wan R, Okun E, Wang X, Lovett-Barr MR, Li Y, Mughal MR, Mendelowitz D, Mattson MP. GLP-1 receptor stimulation depresses heart rate variability and inhibits neurotransmission to cardiac vagal neurons. Cardiovascular research. 2011;89:72–78. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto H, Lee CE, Marcus JN, Williams TD, Overton JM, Lopez ME, Hollenberg AN, Baggio L, Saper CB, Drucker DJ, Elmquist JK. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor stimulation increases blood pressure and heart rate and activates autonomic regulatory neurons. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:43–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI15595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman EL, Stevens MJ, Thomas PK, Brown MB, Canal N, Greene DA. A practical two-step quantitative clinical and electrophysiological assessment for the diagnosis and staging of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1281–1289. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.11.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albers JW, Herman WH, Pop-Busui R, Feldman EL, Martin CL, Cleary PA, Waberski BH, Lachin JM. Effect of prior intensive insulin treatment during the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) on peripheral neuropathy in type 1 diabetes during the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1090–1096. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin CL, Waberski BH, Pop-Busui R, Cleary PA, Catton S, Albers JW, Feldman EL, Herman WH. Vibration perception threshold as a measure of distal symmetrical peripheral neuropathy in type 1 diabetes: results from the DCCT/EDIC study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2635–2641. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polydefkis M, Hauer P, Sheth S, Sirdofsky M, Griffin JW, McArthur JC. The time course of epidermal nerve fibre regeneration: studies in normal controls and in people with diabetes, with and without neuropathy. Brain. 2004;127:1606–1615. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spallone V, Ziegler D, Freeman R, Bernardi L, Frontoni S, Pop-Busui R, Stevens M, Kempler P, Hilsted J, Tesfaye S, Low P, Valensi P. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: clinical impact, assessment, diagnosis, and management. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:639–653. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vileikyte L, Peyrot M, Bundy C, Rubin RR, Leventhal H, Mora P, Shaw JE, Baker P, Boulton AJ. The development and validation of a neuropathy- and foot ulcer-specific quality of life instrument. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2549–2555. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barros JI, Fechine FV, Montenegro Junior RM, do Vale OC, Fernandes VO, de Souza MH, da Cunha GH, de Moraes MO, d'Alva CB, de Moraes ME. Effect of treatment with sitagliptin on somatosensory-evoked potentials and metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arquivos brasileiros de endocrinologia e metabologia. 2014;58:369–376. doi: 10.1590/0004-2730000002914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okawa T, Kamiya H, Himeno T, Seino Y, Tsunekawa S, Hayashi Y, Harada N, Yamada Y, Inagaki N, Seino Y, Oiso Y, Nakamura J. Sensory and motor physiological functions are impaired in gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor-deficient mice. J Diabetes Investig. 2014;5(1):31–7. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jolivalt CG, Fineman M, Deacon CF, Carr RD, Calcutt NA. GLP-1 signals via ERK in peripheral nerve and prevents nerve dysfunction in diabetic mice. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(11):990–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drucker DJ, Sherman SI, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB. The safety of incretin-based therapies--review of the scientific evidence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2027–2031. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bharucha AE, Charkoudian N, Andrews CN, Camilleri M, Sletten D, Zinsmeister AR, Low PA. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1, yohimbine, and nitrergic modulation on sympathetic and parasympathetic activity in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R874–880. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00153.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cefalu WT, Buse JB, Del Prato S, Home PD, LeRoith D, Nauck MA, Raz I, Rosenstock J, Riddle MC. Beyond metformin: safety considerations in the decision-making process for selecting a second medication for type 2 diabetes management: reflections from a diabetes care editors' expert forum. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2647–2659. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng Q, Yang S, Zhao C, Wang Z, Feng Z, Li R, Ye P, Zhang S, et al. Efficacy of metformin-based oral antidiabetic drugs is not inferior to insulin glargine in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients with severe hyperglycemia after short-term intensive insulin therapy. J Diabetes. 2015;7(2):182–91. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brod M, Cobden D, Lammert M, Bushnell D, Raskin P. Examining correlates of treatment satisfaction for injectable insulin in type 2 diabetes: lessons learned from a clinical trial comparing biphasic and basal analogues. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam S. Insulin glargine: a new once-daily basal insulin for the management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Heart Dis. 2003;5(3):231–40. doi: 10.1097/01.HDX.0000074514.20750.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin CL, Albers JW, Pop-Busui R. Neuropathy and related findings in the diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:31–38. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albers JW, Pop-Busui R. Diabetic neuropathy: mechanisms, emerging treatments, and subtypes. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2014;14:473. doi: 10.1007/s11910-014-0473-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pop-Busui R. What do we know and we do not know about cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetes. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5:463–478. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kondo M, Kamiya H, Himeno T, Naruse K, Nakashima E, Watarai A, Shibata T, Tosaki T, Kato J, Okawa T, Hamada Y, Isobe K, Oiso Y, Nakamura J. Therapeutic efficacy of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells in diabetic polyneuropathy is impaired with aging or diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2015;6(2):140–9. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dyck PJ, Albers JW, Andersen H, Arezzo JC, Biessels GJ, Bril V, Feldman EL, Litchy WJ, O'Brien PC, Russell JW. Diabetic Polyneuropathies: Update on Research Definition, Diagnostic Criteria and Estimation of Severity. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011:27. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratzmann KP1, Raschke M, Gander I, Schimke E. Prevalence of peripheral and autonomic neuropathy in newly diagnosed type II (noninsulin-dependent) diabetes. J Diabet Complications. 1991;5(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/0891-6632(91)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith AG, Singleton JR. Impaired glucose tolerance and neuropathy. Neurologist. 2008;14(1):23–9. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31815a3956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith AG, Singleton JR. Idiopathic neuropathy, prediabetes and the metabolic syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2006;242(1-2):9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Callaghan B1, Feldman E. The metabolic syndrome and neuropathy: therapeutic challenges and opportunities. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(3):397–403. doi: 10.1002/ana.23986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.