Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) results in devastating neurological and pathological consequences, causing major dysfunction to the motor, sensory and autonomic systems. The primary traumatic injury to the spinal cord triggers a cascade of acute and chronic degenerative events, leading to further secondary injury. Many therapeutic strategies have been developed to potentially intervene in these progressive neurodegenerative events and minimize secondary damage to the spinal cord. Additionally, significant efforts have been directed towards regenerative therapies that may facilitate neuronal repair and establish connectivity across the injury site. Despite the promise that these approaches have shown in preclinical animal models of SCI, challenges with respect to successful clinical translation still remain. The factors that could have contributed to failure include important biologic and physiologic differences between the preclinical models and the human condition, study designs that do not mirror clinical reality, discrepancies in dosing and the timing of therapeutic interventions, and dose-limiting toxicity. With a better understanding of the pathobiology of events following acute SCI, developing integrated approaches aimed at preventing secondary damage and also facilitating neurodegenerative recovery is possible, and hopefully will lead to effective treatments for this devastating injury. The focus of this review is to highlight the progress that has been made in drug therapies and delivery systems, and also cell-based and tissue engineering approaches for SCI.

Keywords: Drug Therapy, Polymers, Scaffold, Growth Factors, CNS Injury, Inflammation, Gene Therapy

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

According to the 2013 report from Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation, more than a million people in the U.S, ~0.4% of the U.S. population, are living with paralysis due to spinal cord injury (SCI) (1), with about 12,000 new cases added each year (2), and it is estimated to cost $40.5 billion annually to the healthcare industry. Disability due to SCI is a major global issue, affecting both young and elderly populations (2). In addition, military conflicts have contributed to a significant rise of combat-related spinal fractures and spinal cord injuries, imparting substantial disability in affected populations (3).

1.1. Pathology of SCI

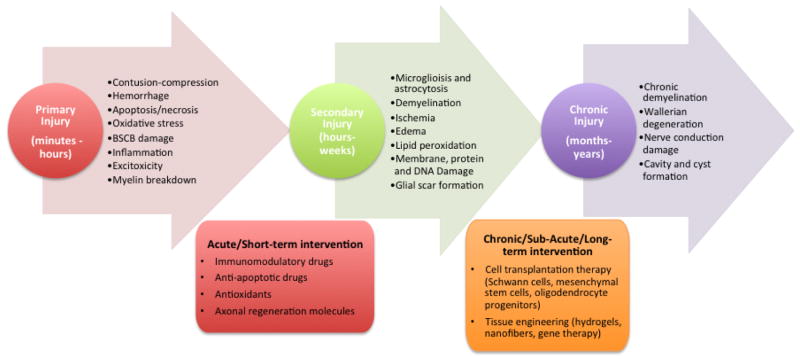

The pathophysiology of traumatic SCI involves primary and secondary damage. The primary injury is considered to be disruption of neural tissue as the immediate result of the blunt, non-penetrating mechanical forces applied at high velocity to the spinal cord as the surrounding bony/ligamentous spinal column fails. Primary mechanical trauma exerts distraction, compression, and shear forces on the spinal cord (4, 5), and can cause damage not only to the central nervous system (CNS) but also the peripheral nervous system (6). Vascular, cellular and axonal damage occurs almost instantaneously and continues to spread from the injury epicenter both radially and axially. Edema of the spinal cord occurs in parallel and may cause further disruption to spinal cord blood flow, exacerbating ischemia (7). The damaged and necrotic cells at the site of primary injury contribute to the secondary injury cascade which has an acute, intermediate and chronic phase, and spreads with time both caudal and cranial to the primary lesion (8) (Figure. 1). The secondary injury eventually leads to the formation of a glial scar (9, 10) which can further impede axonal regeneration (11). Wallerian degeneration, a post-traumatic axonal degeneration distal to the site of disruption continues over a few days to months after SCI (12).

Figure 1.

Progression of spinal cord injury response with time and different therapeutic and regenerative strategies.

1.2. Therapeutic and regenerative strategies for treatment of spinal cord injury

Following surgical interventions that include early spinal decompression and stabilization surgery (13), current treatments used for SCI can be categorized mainly as neuroprotective or neuroregenerative in nature. Neuroprotective therapies focus on impeding or preventing further progression of the secondary injury, whereas neuroregenerative therapies lay emphasis on recovering the lost or impaired functionality by repairing the broken neuronal circuitry of the spinal cord (14, 15). Preclinical research has revealed that many elements of the secondary injury cascade occur over a prolonged period of time post-injury, providing an opportunity for neuroprotective exogenous treatments to be effective if applied within this time period (10, 16). This review covers drug based therapies, both neuroprotective and neuroregenerative in nature, that target a single and/or multiple events in this timely cascade of neurodegenerative events, as shown in Figure 1. However, once the window for therapeutic intervention to prevent secondary injury cascades has passed, the focus turns towards regeneration of the injured spinal cord. Given the enormous complexity of the biological issues facing SCI repair, McDonald & Sadowsky (6) suggested a hierarchy of interventions: (i) limiting secondary damage by surgery, (ii) re-myelination of axons or compensating for it, (iii) eliminating or ablating inhibitory factors, (iv) delivering neurotrophins or growth factors to enhance neuronal growth and axonal regeneration, (v) guiding axons to establish correct connections, (vi) creating bridges by biomaterials and cell grafts to connect nerve fibers, and (vii) removing injured or dead cells. Many of the treatment options and therapies described in the review target one or the other mechanism as described above. These options depend upon the state of the patient. Early interventions following primary injury are aimed at preventing cascades of secondary degeneration, particularly drug and neuroprotective therapies, whereas at a chronic stage, it is primarily regenerative therapy such as cell-based therapies, tissue engineering, either through remyelination and/or axonal sprouting to establish neuronal connectivity and achieve functional recovery.

2. Drugs and Drug Delivery Systems

Many different drug therapies have been tested to prevent the spread of secondary injury and facilitate regeneration. Therapeutic approaches are targeted at either single and/or multiple pathways in the cascade of degenerative events, as described in Figure 1. One of the important challenges in drug therapy is to achieve an effective dose and maintain levels for sufficient time period at the lesion site to achieve therapeutic effect. Systemic administration is the obvious choice for delivering agents, provided that they can cross the blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB) (although this may also be disrupted early after injury). Oral administration for systemic delivery is also possible and obviously more convenient for the patient, although limited gut absorption and subsequent bioavailability at the impact site may influence the therapeutic effect (17). Systemically delivering comparable doses to humans as are effective in animal models may be limited by tolerance in humans and could be a limiting factor in translation of effective therapies (18, 19). Therefore, various drugs and biomolecules have been tested via epidural, intrathecal or intraspinal routes. Administration to the epidural space might provide more targeted therapy than systemic delivery, but requires that therapeutic agents are able to cross the dura, pia and arachnoid meninges that envelop the spinal cord (20). The intrathecal route also aims at better specificity by delivering the agents directly to the spinal cord. This can be achieved via continuous infusion through an indwelling intrathecal catheter, or by repeated lumbar injections. Accessing the intrathecal space in this manner does pose a risk for introducing infection and direct injury to the neural elements (21).

2.1. Therapeutic Strategies

Drug therapies focus on impeding or preventing further progression of the secondary injury by alleviating key injury mechanisms such as apoptosis, oxidative stress or inflammation (22). A few of the therapies that have been tested include erythropoietin (EPO), NSAIDs, minocycline, riluzole, estrogen, and atorvastatin (23). In general, these treatments have shown modest yet promising improvements in preclinical animal models specifically in terms of motor recovery and tissue sparing.

2.1.1. Immunomodulatory therapies

The inflammatory response to SCI is extremely complex, and its beneficial and detrimental roles in the recovery process remains incompletely understood (24). Clinically, the glucocorticoid methylprednisolone (MP) was thought to render neuroprotection by suppressing secondary inflammation and lipid peroxidation when administered at high doses within 8 hours of injury (25). Controversy around its real neurologic efficacy has plagued the use of MP for the last 15 years, and many have abandoned its use for fear of severe complications including pneumonia, sepsis, and death (26). In animal models of SCI, several other drugs that are already FDA-approved for other human diseases have shown promise as neuroprotective agents, potentially by modulating the inflammatory response. These include Rolipram, an inhibitor of phosphodiesterase type 4 proteins, FTY720, a sphingosine receptor modulator for relapsing multiple sclerosis, Imatinib, clinically used for treating leukemias and gastrointestinal stromal tumors and Atorvastatin (Lipitor), for lowering cholesterol. Investigators have noted these drugs to be associated with a reduction in inflammatory cells, inhibition of apoptosis, increased tissue sparing and enhanced locomotor recovery in animal SCI studies (27–29).

Several groups have explored either single and/or combinatorial approaches with Rolipram and other drugs to synergistically target subsequent degenerative pathways, while exerting neuroprotection and functional recovery (30, 31). Anti-inflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin-10 (IL-10) have shown potential for treatment in SCI models (32) with efficacy in improving functional recovery and tissue preservation while reducing neuropathic pain and inflammatory cytokine levels (33, 34). Endogenous growth factor EPO has shown significant attenuation of inflammation and apoptosis, maintenance of microvasculature and tissue integrity, and improved motor activity when administered within 24 h after SCI (35, 36). EPO demonstrates a safe pharmacological profile causing decreased leucocyte infiltration and inhibiting lipid peroxidation by-products while also exhibiting hematopoietic activity which may increase the risk of thrombosis, but non-hematopoietic EPO analogues as tissue protective cytokine have been investigated (35, 37). The glycolytic enzyme chrondroitinase ABC (ChABC) has been investigated for its immunomodulatory benefits after it showed significant restoration of neuronal regeneration and plasticity by directly attacking the CSPG inhibitory activity in the glial scar in both small and large animal populations (38, 39). ChABC gene therapy significantly reduced the secondary injury and improved spinal conduction through modulation of macrophage phenotype to favor the pro-repair M2 macrophages (40).

2.1.2 Targeting axonal growth

Injured CNS myelin contains growth inhibitory molecules that impede the regeneration of injured axons (16). Some level of spontaneous re-growth has been shown to occur, but this development pattern is inconsistent due to lack of pathway guidance or molecular cues causing dysfunctional axon growth (12). One of the best-studied approaches to this problem is the neutralization of Nogo-A, a myelin associated protein, via anti-Nogo-A specific antibodies. This has been shown to enhance sprouting and regeneration of lesioned axons and unlesioned fiber tracts with substantial improvements in functional recovery in rodent and monkey SCI models (41–43). Another promising approach for encouraging axonal growth is to target downstream intracellular signaling pathways within the growth cone such as the Rho/Rac pathway. Rho antagonists such as C3-exoenzyme, fasudil, Y-27532, and ibuprofen have been found to promote improved locomotor outcome in animal models of SCI, and some of these approaches have been translated into human clinical trials. Exogenous delivery of neurotrophins has also shown potential in modulating sensorimotor physiology and plasticity of spinal cord circuits after SCI by influencing cellular processes, but most of the current therapies focus on using them in combination with other cellular transplantation strategies, as discussed in Sections 3 & 4 (44, 45).

2.1.3. Targeting apoptosis/necrosis

A few groups have explored the use of calpain inhibitors in treating SCI, based on the role it plays in the cause and progression of neuronal injury through cytoskeletal protein degradation and programmed cell death, and have shown increased tissue preservation and improved motor recovery in SCI models (46–48). Das et al. showed that pre-treatment of motoneurons with calpeptin prevented apoptosis and maintained their functionality when exposed to glutamate induced excitotoxic environment, thus providing neuroprotection in-vitro (46). Combining calpeptin with MP reported reduction in DNA fragmentation and secondary inflammation in a contusion SCI model; however, no locomotor improvements or pathological markers were investigated, which makes it difficult to analyze the mechanisms which may be at play while the treatment worked synergistically (47). Targeting and modulating signaling pathways, specifically the c-Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway involved in apoptosis (49), has shown both neuroprotection and pain attenuation (50). D-JNKI1, a cell permeable peptide inhibitor of JNK, has shown prevention of caspase3 activation, increased locomotor recovery and white matter sparing when administered 6h post-SCI in mice (51).

2.1.4. Targeting ischemia/hypoxia

Yacoub et al. used Oxycyte, an intravenous injectable perfluorocarbon, to relieve the long-lasting ischemia and hypoxia resulting post-SCI by improving the tissue oxygenation in a contusion model, and reported decreased lesion sizes with improved locomotor function and white matter preservation (52). Although they focused on the use of Oxycyte as a monotherapy, the authors proposed a combinative therapy with other immunomodulatory compounds that are already FDA approved, such as FTY 720 (27).

2.1.5. Targeting excessive iron accumulation

Damage to the blood vasculature post-SCI causes excess iron to accumulate in the spinal cord which causes iron-induced oxidative stress. Multiple groups have sought to demonstrate the involvement of iron in the progression of the secondary injury using iron chelation therapies, and have shown locomotor improvements and reduced pathologies (53–55). However oral administration of iron therapies such as chelating agents (e.g. quercitin, deferoxamine and ceruloplasmin) must be preceded with caution as it can induce negative side effects such as systemic anemia (56).

2.1.6. Targeting oxidative stress

Excessive formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is a well characterized pathological process occurring during the acute and intermediate phases of secondary SCI, causing damage to cell membrane lipids, proteins and DNA resulting in neuronal cell apoptosis and death (57, 58). Studies have been conducted to mitigate acrolein mediated oxidative damage and neuronal injury by use of acrolein scavengers, most notably hydralazine (59). Park et al. showed that daily intraperitoneal injections of hydralazine were effective in reducing acrolein levels, motor deficits and neuropathic pain in contusive SCI model (60). Hydralazine has a half-life period of a few hours (61) and this can be a limiting factor for experimental and clinical studies. Melatonin, a hormone responsible for regulating circadian rhythms, has been shown to exert a scavenging effect against hydroxyl and peroxyl radicals mediated oxidative damage (62). Apart from a decrease in lipid peroxidation, studies in contusion and compression SCI models have shown melatonin to preserve neuronal, axonal and BSCB architecture and enhance functional recovery (63–66). Another recent study has tested the efficacy of combining melatonin with exercise-based neurorehabilitation and successfully reported decrease in nitric oxide levels as well as an increase in motor neurons (67). High doses of antioxidants, Vitamins C & E (100 mg/kg/day), in an SCI model have shown to lessen the inflammatory response, but no improvements in neurological performance were observed (68).

2.1.6.1 Antioxidant enzymes

In our studies, we are exploring superoxide dismutase (SOD)- and catalase (CAT)-loaded antioxidant nanoparticles to inhibit the spread of secondary injury cascades. Normal brain and spinal tissue contain high levels of endogenous antioxidants to counteract the ROS (69) that are continuously produced due to the metabolism of excitatory amino acids and neurotransmitters (70, 71). However their levels are not sufficient to neutralize excessive ROS formed post SCI. Initially there is a transient increase in antioxidant activities, particularly of SOD and CAT post-SCI, but due to their rapid consumption and the downregulation of their genes, neuronal cells are unable to maintain the redox balance, a condition leading to oxidative stress (72). Wang et al. (73) have shown decreasing SOD and CAT activities in the injured spinal cord with time, reaching undetectable levels by 14 d post injury. Their study also reported a concomitant increase in stress proteins, known to trigger inflammation, signifying the role of SOD and CAT in neuroprotection against oxidative stress. The high levels of unsaturated lipids and fatty acids present in neuronal cells make them highly susceptible to oxidative damage (74).

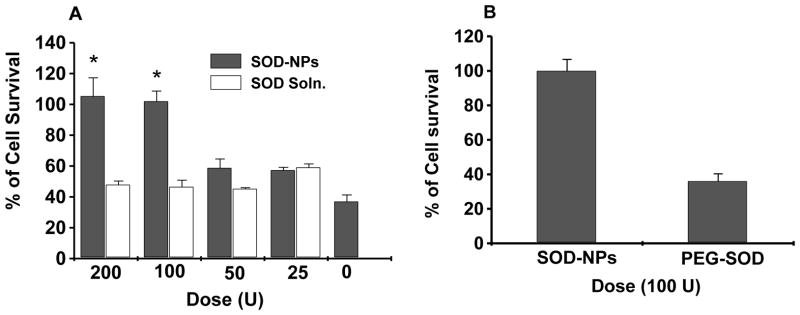

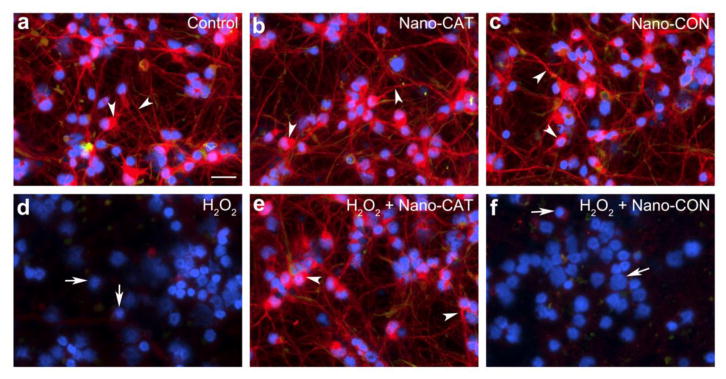

Various pharmacodynamic factors impede the straightforward use of native forms of SOD or CAT in SCI because a) their molecular weights are well below the renal glomerular filtration cutoff, resulting in their rapid clearance from systemic circulation (t1/2 of SOD in rats = 4–8 min, CAT = 8–10 min); b) they are negatively charged at physiological pH and therefore do not readily cross the cell membranes (75); and c) neurons and astrocytes do not appear to take up the native enzyme under normal conditions and hence cannot neutralize the ROS formed intracellularly (76). Different alternatives have been investigated to address these issues, e.g., PEGylation and lecithinization to improve their circulation half-life (77); however, there are limitations to these modifications, e.g., PEGylated SOD (PEG-SOD) increases the enzyme’s stability in the circulation from 6 min to 36 h, but it limits the permeability of SOD across cerebral cell membranes and SOD’s uptake by neuronal cells (78). Instability of liposomes in vivo (half-life ~4.2 hr) limits the duration of SOD activity and efficacy (79, 80). To address these issues, we have designed a sustained nano-SOD/CAT, consisting of forms of the antioxidant enzymes SOD and CAT encapsulated in biodegradable nanoparticles (NPs). In our published studies, using a hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress model, we have demonstrated complete neuroprotection with SOD-NPs, whereas SOD and PEG-SOD were ineffective (81) (Figure 2). Recently, we demonstrated a similar protective effect of CAT-NPs in human neurons (82) and astrocytes; the efficacy of encapsulated enzymes has been attributed to their efficient NP-mediated intracellular delivery and sustained protective effect (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Neuroprotective efficacy of SOD-NPs in human neurons.

(A) SOD-NPs (superoxide dismutase-loaded nanoparticles) using different doses of SOD at 6 hrs in neurons under hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress; (B) Comparative neuroprotective effect of SOD-NPs with pegylated-SOD (PEG-SOD) in neurons under hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress, Dose of SOD = 100 U (Data as mean + s.e.m.; n = 3; *P < 0.05). Figure reproduced with permission from reference (81).

Figure 3. Nano-CAT-NPs protect human neuronal cells from oxidative stress.

Primary human neurons were challenged with hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative (50 μM, 24 h) with or without 200 μg/ml Nano-CAT (catalase-loaded NPs) or Nano-CON (control NPs without CAT) and stained for microtubule associated protein 2 (MAP-2). Immuno-staining micrographs (a–f) show MAP-2 staining (red, neuronal marker; specific cytoskeletal proteins that are enriched in dendrites and essential to stabilize its shape); Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, green, astrocyte marker); and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue, nuclei). Arrow represents loss of MAP-2, neurite network or fragmented nuclei. Arrowhead represents MAP-2 enriched neurons. Images are representative of five random fields of at three donors. Scale bar = 50 μm. Reproduced with permission from reference (82).

2.1.7. Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery

In addition to our study to deliver antioxidant enzymes using NPs as described above, several other groups have explored NPs as a drug delivery system to sustain drug effect at the impact site. The small size of NPs allows them to cross cell membranes or BSCB, thus greatly extending the bioavailability of drugs in the lesion site (83). NP based delivery of MP has been explored by various groups to improve the drug efficacy while neutralizing some of the detrimental side effects that are associated with its systemic high doses. PLGA-NPs and carboxymethylchitosan/polyamidoamine dendrimers loaded with MP have shown significant reduction in the lesion size, improved behavioral outcomes, suppression of microglial and astrocytic responses and improved axon regeneration in hemisection SCI models (84, 85). Systemic administration of ferulic acid (FA)- glycol chitosan (GC) (FA-GC) NPs was reported to cause improvements in locomotion, axonal and myelin protection, attributed to the neuroprotective properties of FA and GC which extend anti-oxidative effects to prevent inflammation and excitotoxicity (86). Administration of small molecule inhibitors such as Chicago sky blue, a macrophage migration inhibitory factor, encapsulated in NPs increased white matter and blood vessel integrity post-SCI (87), but demonstrated activation of both pro- and anti-inflammatory signals which could be ascribed to dynamic changes in macrophage phenotypes while still being reparative in nature (88). Another pharmacological approach modulated the activated microglia/macrophage response in the subacute phase of inflammation by using minocycline loaded polymeric polycaprolactone NPs (89). These authors observed reduced proliferation and altered morphology from activated to resting phase in the microglia/macrophage environment, due to the antioxidant and neuroprotective effect of minocycline (90). PEG functionalized silica NPs have been used by Cho et al. (91) in crush/contusion SCI and the results show blockage of the resulting lipid peroxidation and ROS upregulation, recovery of somatosensory evoked potential conduction and maintenance of membrane structure and integrity. Another study by Wang et al. used an instraspinal injection of GDNF loaded PLGA NPs in a contusion SCI model and saw an increase in neuronal survival and locomotor improvements (92).

2.1.8. Hydrogels-mediated drug delivery

Hydrogels are three-dimensional nanostructured networks of hydrophilic polymers with superior similarity to native extracellular matrix (ECM). Due to their tunable mechanical property and degradation profile, hydrogels are used as excellent scaffolds for both drug release and cell support with good biocompatibility (Cell-based therapy utilizing hydrogels is discussed later in Section 4.1). With proper in situ gelation, hydrogels can be precisely injected to fill up the SCI lesion by exact geometrical re-shaping, which avoids more invasive surgeries that potentially exaggerate established injury. Sustained and localized release of MP was achieved by encapsulating MP into biodegradable nanoparticles, which were then embedded in an agarose hydrogel implanted into contusion injury, and significantly reduced lesion volume 7 days after injury (93). Chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) as a promising annihilator for glial scars has been incorporated in various hydrogels for sustained and controlled release, which has generated encouraging results (94, 95). Multiple studies have utilized engineered hydrogels to release neurotrophins and growth factors directly into the SCI lesion and demonstrated supplementary exogenous neurotrophins such as NT-3, VEGF, GDNF, NGF, and BDNF could facilitate locomotive recovery in SCI (96, 97). Compared with commonly used methods such as direct injection, systemic administration and intrathecal infusion, hydrogels are able to provide a sustained and tunable release of loaded growth factors (98, 99). Hydrogels are promising carriers for controlled drug release, yet investigation about their long-term safety and biocompatibility after implantation is needed for further clinical application.

2.2. Clinical trials based on drug therapies

Clinical trials for SCI using therapeutics have been underway for a number of years, although the neurological efficacy of these agents is still undetermined. A brief summary of the current clinical trials using drug therapies is provided in Table 1 below. A few of the drugs that have been or are currently being assessed include:

Table 1.

Clinical trials based on drug therapies

| TITLE | INTERVENTIONS | PHASE | ID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minocycline and Perfusion Pressure Augmentation in Acute Spinal Cord Injury | Drug: Minocycline Drug: placebo Procedure: SCPP augmentation Procedure: SCPP control |

Phase 1 Phase 2 |

NCT00559494 | |

| Minocycline in Acute Spinal Cord Injury (MASC) | Drug: Minocycline Drug: Placebo Procedure: Surgical spinal cord decompression Procedure: Maintenance of minimum mean arterial pressure (MAP) |

Phase 3 | NCT01828203 | |

| Safety of Riluzole in Patients With Acute Spinal Cord Injury | Drug: Riluzole | Phase 2 | NCT00876889 | |

| Riluzole in Spinal Cord Injury Study (RISCIS) | Drug: Riluzole Drug: Placebo |

Phase 2 Phase 3 |

NCT01597518 | |

| A Safety Study for Cethrin (BA-210) in the Treatment of Acute Thoracic and Cervical Spinal Cord Injuries | Drug: Cethrin | Phase 1 Phase 2 |

NCT00500812 | |

| Evaluation of Tolerability and Efficacy of Erythropoietin (EPO) Treatment in Spinal Shock: Comparative Study Versus Methylprednisolone (MP) | Drug: Erythropoietin Drug: Methylprednisolone |

Phase 3 | NCT00561067 | |

| Acute Safety, Tolerability, Feasibility and Pharmacokinetics of Intrath. Administered ATI355 in Patients With Acute SCI | Drug: ATI355 | Phase 1 | NCT00406016 | |

| Combination Therapy With Dalfampridine and Locomotor Training for Chronic, Motor Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury | Drug: Dalfampridine Drug: Placebo |

Phase 2 | NCT01621113 | |

Minocycline: Minocycline is a long-acting, broad-spectrum antibiotic that works through immunomodulation of microglia proliferation, reduced excitotoxicity and mitochondrial stabilization resulting in reduced apoptosis and neutralization of oxygen radicals and nitric oxide synthase inhibition (100). Pre-clinical studies have shown a neuroprotective effect in acute SCI and reduction in neuropathic pain (101, 102). A recently concluded Phase II clinical trial (NCT00559494) was able to determine safe and adequate dosage in acute SCI. The trial was not powered to establish efficacy, but there was some suggestion of a benefit to individuals with incomplete cervical SCI (100). A Phase III study is currently underway (NCT01828203), aiming to evaluate the efficacy of minocycline in improving neurological and functional outcome after acute traumatic non-penetrating cervical SCI.

Riluzole: Riluzole is a benzothiazole anticonvulsant that works through blockage of the sodium channels, which prevents increase of intracellular sodium and calcium concentrations, thereby inhibiting excitotoxicity (103). Pre-clinical studies demonstrated a neuroprotective effect in acute SCI, reversed neuropathic pain and reduced spastic muscle activity (104, 105). A recently concluded Phase IIa clinical trial (NCT00876889) was able to determine the safety and pharmacokinetic profile of riluzole in SCI patients, which has helped in the development of a definitive efficacy study (103, 106). A Phase II and III trial (NCT01597518) is currently underway to evaluate the effect of riluzole on neurological, functional and sensory recovery on SCI patients.

Cethrin: The active component of Cethrin is a cell and BSCB permeable synthetic variant of C3 transferase, which blocks the Rho signaling pathway. This is thought to inhibit apoptosis and promote axonal regeneration (107, 108). Pre-clinical studies in acute-SCI have shown diffusion of the BA-210 into the lesion site, inactivation of Rho in a dose-dependent manner, improved tissue sparing and functional recovery (108). Cethrin is administered within a fibrin glue that is applied directly to the dura over the injury site at the time of decompressive surgery. A Phase I/II multi-center trial of Cethrin has been completed and reported improvements in motor function in a dose-dependent manner (107).

Erythropoietin: EPO, a glycoprotein hormone, has been used in numerous preclinical animal studies and has shown promising neurological recovery and tissue sparing (35, 109, 110). A recently concluded pilot study (NCT00561067) assessed the efficacy of EPO and MP in acute SCI patients. This trial was too small to realistically assess efficacy of the EPO, but it appears to be safe and well-tolerated (111).

Anti-Nogo-A antibody: Nogo-A is a myelin protein in the CNS that inhibits neurite growth (112). In arguably the most extensively studied approach to promoting CNS regeneration after SCI, it was with great expectations that a clinical trial evaluating anti-Nogo antibodies was launched. This trial (a Phase I clinical trial, Acute Safety, Tolerability, Feasibility and Pharmacokinetics of Intrathecally Administered ATI355 in Patients With Acute SCI (NCT00406016)) was completed a number of years ago and the data has not yet been published from it (112).

Dalfampridine: The tablet formulation of dalfampridine contains the active agent 4-Aminopyridine, a potassium channel blocker, and is also known by Fampridine-SR which stands for sustained release of dalfampridine. Pre-clinical studies have shown increased conduction in demyelinated axons in rats and modest tolerance of the drug with no significant differences between SCI and placebo groups in two Phase III clinical trials (113, 114). A Phase II clinical trial (NCT01621113) is currently underway to determine the safety, tolerance and efficacy of dalfampridine when used in combination with locomotor training in chronic, motor incomplete SCI patients vs. placebo controls.

3. Cell-based Therapies

The loss of neuronal tissue and the establishment of a cystic cavity at the injury site has made cell transplantation an attractive strategy for SCI. Over the last several decades, multiple lineages of cells have been tested, based on their specific functional potentials in the context of spinal cord regeneration. Cell-based therapeutic strategy has become the most important part of translational medicine and clinical trials for SCI. Grafting of somatic cells and tissues such as olfactory-ensheathing cells (OECs), Schwann cells, fetal tissues, peripheral nerves have made the SCI microenvironment more favorable for neural regeneration (115). On the other hand, neural progenitor/stem cells, embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), fibroblast-derived stem cells, etc. are all exploited for their pluripotent differentiation ability to replace neuronal lineage cells, enhance axonal regeneration and restore inter-neuron communications (116). Stem cell-based therapy is promising, yet potential side effects and safety concerns do exist, such as ethical issues, immunological rejection, and tumor formation (117). Cell transplantation can also act as a vehicle for gene delivery. Genetically modified Schwann cells and others have been attempted for SCI to promote nerve regeneration (118). Moreover, genetically engineered MSCs have also been used to deliver many factors such as neurotrophic factors, receptor tyrosine kinases, and HGF to promote survival of themselves and the regeneration of damaged neurons (119).

3.1. Neural stem/progenitor cells and oligodendrocyte progenitor cells

Neural stem/progenitor cells (NS/PCs) refer to the multipotent cells that give rise to other cells of the nervous system (120). Recently NS/PCs have been identified in the spinal cord along the central canal down to the filum terminale (FT), which originally regarded as clinically useless but now has been found to be a source of NS/PCs in both rats and human (121). NS/PCs can be expanded in a neural sphere culture system, and differentiate when adhesive substrate is provided and mitogens removed. NS/PCs derived from spinal cord give rise to a consistent “neuron: glia” ratio of 3:1(120, 122). NS/PCs are less tumorigenic than embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and have been safely used to treat patients with stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and cerebral palsy (123). To further reduce this risk, a more downstream progenitor, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) are used instead of NS/PCs for transplantation. OPCs could be obtained from human fetal NS/PCs for large scale production to meet the clinical demand (122).

3.2. Olfactory ensheathing cells and olfactory mucosa cells

Olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs) have been tested for SCI (124). During normal cell turnover, new olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) are able to extend axons to re-enter the olfactory bulb and re-synapse with second-order neurons in the glomerular layer. This process of axonal regeneration from the peripheral to central nervous system is facilitated by OECs. Recently, researchers in Poland have described their experience using cells taken from the olfactory bulb and olfactory mucosa in human SCI patients (125). In semi-transected cervical spinal cord, injected OECs induced elongating axons into the denervated caudal host tract (126). Six patients received autologous OEC transplantation in a Phase I clinical trial, of whom three patients showed signs of improvement of SCI, and two improved from ASIA-A to -C and -B (127). To overcome the difficulty to obtain OECs, olfactory mucosa cells (OMCs) were tested and have promoted axonal outgrowth (128, 129). However, OMC transplantation performed in Portugal resulted in formation of tumor-like structure, which could have been due to improper purification of cells (130).

3.3. Bone marrow stromal cells/mesenchymal stem cells

Bone marrow stromal cells and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are essentially from the same group of stem/progenitor cells, but differ in their cell procuring processes. MSCs can be conveniently obtained from bone marrow, blood, adipose and dental tissues. MSCs are able to differentiate into essentially all non-hematopoietic lineages, thus holding great clinical potential (131). Animal studies with SCI have shown that transplanted MSCs survived in the spinal cord, migrated into the host tissue and led to axonal regeneration and motor function recovery (131). MSCs have innate neuroprotective properties, as they create a favorable environment for axonal growth by the expression of a myriad of growth factors and cytokines such as neurotrophins, colony stimulating factor (CSF), interleukins, stem cell factor (SCF), NGF, BDNF, HGF and VEGF (131). They also induce angiogenesis as well as transform hostile glial environment in favor of axonal regeneration (131). In rodent studies, the effect of MSCs was more pronounced when they were grafted 7 days after injury, while IV transplantation of MSCs 4 months after SCI had no effect on motor functions as indicated by the BBB scores. It is generally proposed that this window spans between 3 days and 3 weeks after SCI (131).

3.4 Schwann cells

Schwann cells (SCs) have shown potential to myelinate axons when injected into the SCI lesion (129). Transplantation of SCs has been shown to suppresses cavity formation, promote tissue sparing, and form a bridge across the lesion site (132). SCs were able to migrate extensively in CNS and to re-myelinate axons; however, supraspinal axons failed to traverse the caudal SC-host interface, and it was difficult to maximize SC integration into the adjacent cord parenchyma (133). Further SC-precursor cells have been shown to survive, integrate and support axon growth. SCs differentiated from MSCs can meet clinical demand, while combination with other factors or cells could potentially be explored for SCI (134).

3.5. Astrocytes, a potential candidate for cell therapy

Astrocytes are the most abundant glial cells in the CNS playing pivotal roles in maintaining homeostasis (135). Recently, astrocytes are being more and more recognized as a necessary component to promote axonal re-growth after SCI (136). Those axons that previously thought to be sealed off by glial scar actually retain their regenerative potential and could still bypass the scars a full year later (130, 135). Glial scarring can protect the injured tissues and maintain the integrity of BSCB (135), while simply removing activated astrocytes would worsen the locomotive recovery (137). Astrocyte transplantation for SCI has been attempted, which revealed the potential to promote axonal regeneration and functional recovery (138). However, due to the heterogeneity of astrocytes, further studies to determine the best choice of an appropriate subpopulation is necessary (135).

3.6. Neural conversion of somatic cells

Induced pluripotency and lineage conversion have become a very interesting strategy for the treatment of SCI (139, 140). The former refers to creating ESC-like stem cells, namely induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), by forced overexpression of certain transcription factors, which subsequently differentiate into target cells, while the latter is to transform one differentiated cell type directly into another without transitioning through a pluripotent cell state (141). The creation of iPSCS by Yamanaka et al. established a complete new approach for the treatment of many diseases including SCI (142). Forced overexpression of a variety of TFs such as OCT4, Sox2, klf4, Myc, Pax6, Ngn2, Ascl1, and Dlx2, Nanog, Brn2, Myt1l, Zfp521, etc. has been utilized to convert various cell types. Among them, Ascl1 is particularly necessary for neuronal differentiation (143). A cocktail of motor neuron transcription factors were formulated to generate motor neurons (144). Numerous differentiated cell types including hepatocytes, adult astrocytes, and fibroblasts were used to generate neurons via a transient pluripotent step (145). To date, the clinical use of iPSCs is limited due to the low efficiency of current reprogramming protocols and the need of genetic modifications, which may lead to unpredicted consequences (146).

3.7. Macrophages in SCI

Recent research indicated that macrophages could be classified into two phenotypes with distinct functionalities, namely M1 and M2 (147, 148). M1 macrophages augment inflammation and tissue destruction in SCI, whereas M2 macrophages promote tissue regeneration. Depletion of M1 macrophages was shown to improve recovery (149), while augmenting M2 phenotypes promoted motor function recovery (150). Inducers for M2 macrophages such as MCP-1, ED-Siglec-9, MSCs-conditioned medium led to significant locomotive recovery in animal model studies (151). When co-transplanted with reparative M2 macrophages, NS/PC-derived neurons integrated into the local circuitry and promoted locomotive recovery (152). A biopharmaceutical company, Proneuron sponsored Phase I clinical trials for transplantation of activated macrophages in Israel and Belgium, and a randomized controlled, multicenter, Phase II clinical trial is also going on at USA and Israel hospitals (153).

3.8. Challenges in cell-based therapy for SCI

The critical challenge is obtaining sufficient quantity of purified cells. Further, SCI creates a hostile microenvironment that could affect the survival and integration of transplanted cells (123). Research is on going to understand the dynamics of implanted cells in SCI specific microenvironment and to determine the optimal window for cell therapy, which is currently proposed as 7–10 days post injury (154). Transplanted cells have varied ability to home to the spinal cord lesion or the designated location for optimal function. From this point of view, the route for cell delivery could have significant influence upon any cell-based therapy for SCI. MSCs could home to spinal lesions after intravenous injection, but this route requires larger amount of cells to ensure adequate population in the target tissue. Substantial amount of intranasally administered MSCs could home to the spinal cord lesion within 4 weeks, but the number and therapeutic effect was significantly lower than the intrathecally delivered group (155). Direct transplantation of cells to the injured spinal cord is commonly performed, but this route could lead to secondary nerve damage from needle penetration, spinal cord dislocation, intraparenchymal pressure, volume effect of cell mass and possible cord ischemia (156). Mehta et al. reported functional improvement in 31.67% patients through subarachnoid route, which avoided direct needle injury to the cord parenchyma. However this route is challenging in chronic SCI patients (157) and suggested that an optimal protocol is required to avoid potential iatrogenic problems (157). Further, potential of a tumor-like structure formation of the transplanted cells is another challenge to overcome in order to make this approach effective and safe (158).

4. Tissue Engineering for SCI

Recent evidence indicates that the spinal cord does have minimal potential to regenerate after injury; however, due to the hostile microenvironment created by SCI, endogenous regeneration is lacking (159). Tissue engineering is aimed to rebuild damaged tissue with biocompatible scaffolds, possibly embedded with living cells (160). Numerous biomaterials have been used to develop tissue engineering scaffold for SCI including natural materials such as hyaluronic acid (HA), collagen-based matrices, chitosan, agarose, alginate, etc., as well as synthetic materials such as nitrocellulose membranes, synthetic polymers, biodegradable synthetics (131, 161). Biological grafts such as fetal spinal cord and peripheral nerve implants have also been tested. Biomaterials for SCI need to meet a list of requirements. Firstly, they must be soft enough not to compress surrounding spinal cord tissue, but structurally strong enough to sustain local fixation (162). Secondly, they must have good biocompatibility, desired porosity and permeability, and surface nanotopographies for optimal cell function (163). Thirdly, they should command a proper degradation rate in harmony with the ingrowth of supportive tissue and the extension of re-growing axons (160). Natural compound scaffolds have better performance as compared to synthetic materials in term of cell support (153, 161). In a few studies, instead of being used as cell substrate, the biomaterial scaffolds were also used for protracted release of proteins or therapeutic agents, as mentioned in previous sections (Sections 2.1.7–9) (164). The diverse types of biomaterials currently used for scaffold for SCI could be generally divided into two broad categories: hydrogels and nanofibers, the former made by process of cross-linking and polymerization, while the latter from a variety of techniques mostly based on electrospining.

4.1. Hydrogels for tissue engineering

Hydrogels are hydrophilic polymers, which physically mimic the ECM. According to their source of origin, hydrogels could be classified into natural, synthetic, and composite materials. A variety of natural materials from normal tissue or extracellular matrix have been used to form hydrogels for tissue engineering purposes such as chitosan, collagen, hyaluronic acid, elastin, alginate, fibrinogen, laminin, gelatin, and so on (98). Synthetic hydrogels can be made from different synthetic polymers such as poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL), poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), poly(hydroxethyl methacrylate) (PHEMA), polyvynilalchol (PVA), polyacrylamide, poly(hydroxypropyl methacrylate) (PHPMA), and so on (98). The purpose of placing a hydrogel is to “bridge” or fill-up the lesion to help promote functional recovery (160, 164). These hydrogels could be loaded with various pro-regenerative factors such as chondroitinase ABC, BDNF, NGF, etc (165). Compared with natural materials, synthetic hydrogels are much superior in terms of easier mass-production and property modification (166). A common drawback of synthetics is potential toxicities of contaminant or by-product, if not eliminated completely (98). Synthetic materials are often coated with natural materials to improve surface features (167). In terms of axon regeneration, biopolymers could be ranked in the order PEG>alginate-hydrogel> Matrigel™ (168).

4.2. Nanofibers and self-assembling nanofibers for tissue engineering

Nanofiber scaffolds are essentially another kind of “hydrogel”, which are composed of nanofibers. Filling the lesion with nanofiber scaffolds made by electrospinning-based techniques is drawing attention. By enabling layer-by-layer approach, 3-D tissue printing has become realizable, while with surface functionalization, they can also be a good system for drug delivery (169). Spatial orientation of nanofibers in scaffolds can have dramatic influences upon cell polarization and function as confirmed in many cell types including neural stem cells (170). The diameter of aligned nanofibers also affects cell differentiation and neurite outgrowth, as a silk fibroin scaffold with 400 nm in fiber diameter performed much better than 800 nm ones (171).

A new methodology for nanotechnology is self-assembling (peptide) nanofibers (SAPNs). All four classes of biomolecules have been explored to generate SAPNs (172), which form nanofibers, nanotubes or nanospheres (173). These materials can be injected into the lesion in liquid form and aggregate in situ into a stable nano-network with physiological salt solution or changed pH (174). They fill up cavities without secondary damage, as caused by other scaffolds (175). SAPNs are composed solely of natural peptides, thus should theoretically incur no adverse effect in the recipient (176). There are several classes of SAPN materials, such as peptide amphiphiles (PA), Fmoc-peptides, self-complementary ionic peptides, hairpin peptides, and so on (177).

The peptide terminus can be functionalized with various ligands such as integrin receptor-binding sites (178), bone marrow homing proteins (173), IGF (179) or stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) (180), sometimes there could be more than one motif separated by a diluent section (173). SAPN scaffold could possess 1000 times more functional epitopes than natural ECM (178). A commercialized SAPN, BD PuraMatrix, derived from RADA-16, when seeded with human fetal Schwann cells, reduced astrogliosis and increased S-100 positive cells in SCI rats (181). A brief summary of the current clinical trials on cell-based, and tissue engineering approaches is provided in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Summary of clinical trials employing cell-based, and tissue engineering approaches

| TITLE | INTERVENTIONS | PHASE | ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety of Autologous Human Schwann Cells (ahSC) in Subjects With Subacute SCI | Biological: Autologous Human Schwann cells | Phase 1 | NCT01739023 |

| The Safety of ahSC in Chronic SCI With Rehabilitation | Biological: Autologous Human Schwann cells | Phase 1 | NCT02354625 |

| Safety and Effect of Adipose Tissue Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Implantation in Patients With Spinal Cord Injury | Procedure: Autologous Adipose Tissue Derived MSCs Transplantation | Phase 1/Phase 2 | NCT01769872 |

| Autologous Adipose Derived MSCs Transplantation in Patient With Spinal Cord Injury. | Other: Autologous Adipose Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells | Phase 1 | NCT01274975 |

| Transplantation of Autologous Adipose Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs) in Spinal Cord Injury Treatment | Device: Laminectomy| Device: Intradural space| Device: Intrathecal| Device: Intravenous | Phase 1/Phase 2 | NCT02034669 |

| Intrathecal Transplantation Of Autologous Adipose Tissue Derived MSC in the Patients With Spinal Cord Injury | Drug: Autologous Adipose Tissue Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells | Phase 1 | NCT01624779 |

| Autologous Bone Marrow Cell Transplantation in Persons With Acute Spinal Cord Injury- An Indian Pilot Study. | Biological: Autologous Bone Marrow Cells | Phase 1 Phase 2/ | NCT02260713 |

| Cell Transplant in Spinal Cord Injury Patients | Procedure: Autologous Bone Marrow Transplant| Procedure: Physical Therapy | Phase 1| Phase 2 | NCT00816803 |

| Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) Patients | Procedure: Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells | Phase 2 | NCT01694927 |

| Evaluation of Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury: a Pilot Study | Other: Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation | Phase 1| Phase 2 | NCT02152657 |

| Study the Safety and Efficacy of Bone Marrow Derived Autologous Cells for the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury | Biological: Transplantation of Autologous Stem Cell [MNCs]. | Phase 1| Phase 2 | NCT01833975 |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells Transplantation to Patients With Spinal Cord Injury | Biological: Bone Marrow Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells | Phase 1| Phase 2 | NCT01446640 |

| Subarachnoid Administration of Adult Autologous Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Cells Expanded in Incomplete (SCI) | Biological: Adult autologous Mesenchymal Bone Marrow Cell | Phase 1 | NCT02165904 |

| Stem Cell Therapy in Spinal Cord Injury | Biological: Autologous Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cell Transplantation | Phase 2 | NCT02009124 |

| Safety and Efficacy of Stem Cell Therapy in Spinal Cord Injury | Biological: Autologous Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cell Transplantation | Phase 1 | NCT02027246 |

| Autologous Bone Marrow Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients With Spinal Cord Injury | Procedure: Stem Cell Transplantation | Phase 1 | NCT01325103 |

| Safety and Efficacy of Autologous Bone Marrow Stem Cells in Treating Spinal Cord Injury | Procedure: Laminectomy| Procedure: Intrathecal | Phase 1/Phase 2 | NCT01186679 |

| To Study the Safety and Efficacy of autologous Bone Marrow Stem Cells in Patients With Spinal Cord Injury | Other: Bone Marrow Derived Stem Cells | Phase 1/Phase 2 | NCT01730183 |

| Safety Study of Local Administration of Autologous Bone Marrow Stromal Cells in Chronic Paraplegia | Other: Cells. | Phase 1 | NCT01909154 |

| Safety and Efficacy of Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury | Procedure: Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation | Phase 2/Phase 3 | NCT01676441 |

| Transplantation of Autologous Olfactory Ensheathing Cells in Complete Human Spinal Cord Injury | Procedure: Olfactory Mucosa Ensheathing Cell Grafting, Rehabilitation| Other: Rehabilitation | Phase 1 | NCT01231893 |

| Study of Human Central Nervous System (CNS) Stem Cell Transplantation in Cervical Spinal Cord Injury | Drug: HuCNS-SC cells | Phase 2 | NCT02163876 |

| Neural Stem Cell Transplantation in Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury | Biological: Autologous Stem cell Transplantation | Phase 1/Phase 2 | NCT02326662 |

| Long-Term Follow-Up of Transplanted Human Central Nervous System stem cells (HuCNS- SC) in Spinal Cord Trauma Subjects | Other: Observation | NCT01725880 | |

| Safety Study of Human Spinal Cord-Derived Neural Stem Cell Transplantation for the Treatment of Chronic SCI | Device: Human Spinal Cord Stem Cells. | Phase 1 | NCT01772810 |

| Study of Human Central Nervous System Stem Cells (HuCNS-SC) in Patients With Thoracic Spinal Cord Injury | Biological: HuCNS-SC cells | Phase 1/Phase 2 | NCT01321333 |

| Nerve Regeneration-Guided Collagen Scaffold and Mesenchymal Stem Cells Transplantation in Spinal Cord Injury Patients | Device: Collagen Scaffold with Stem Cells | Phase 1 | NCT02352077 |

| Difference Between Rehabilitation Therapy and Stem Cells Transplantation in Patients With Spinal Cord Injury in China | Procedure: Rehabilitation of Limb Function| Procedure: Stem Cells Transplantation | Phase 2 | NCT01393977 |

| Lithium, Cord Blood Cells and the Combination in the Treatment of Acute & Sub-acute Spinal Cord Injury | Procedure: Conventional Treatment| Drug: Lithium Carbonate Tablet| Biological: cord blood cell| Other: Placebo | Phase 1/Phase 2 | NCT01471613 |

| Different Efficacy Between Rehabilitation Therapy and Stem Cells Transplantation in Patients With SCI in China | Procedure: Cell Therapy| Other: Rehabilitation | Phase 3 | NCT01873547 |

| Safety and Feasibility of Umbilical Cord Blood Cell Transplant Into Injured Spinal Cord | Biological: Umbilical cord Blood Mononuclear Cell| Drug: Methylprednisolone| Drug: Lithium | Phase 1/Phase 2 | NCT01046786 |

| Umbilical Cord Blood Mononuclear Cell Transplant to Treat Chronic Spinal Cord Injury | Biological: Umbilical cord blood Mononuclear cell| Biological: Methylprednisolone| Drug: Lithium Carbonate Tablet | Phase 1/Phase 2 | NCT01354483 |

| Safety and Feasibility Study of Cell Therapy in Cord Tissue-Derived Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury | Biological: Intravenous and Intrathecal Human Umbilical Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells | Phase 1/Phase 2 | NCT02237547 |

5. Gene Therapy by way of Tissue Engineering

Since both transgenic cells and biomaterials can be modified to deliver transgene or gene products locally to the spinal cord, a combination of gene therapy and TE in the field of regenerative SCI is inevitably coming (182). The complexity of SCI provides numerous gene targets as potential treatments, such as nerve growth factors (NGF, BDNF, NT-3), regenerative cell adhesion molecules (L1, membrane-crossing mimetic peptide, plasticity-associated polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM)), Rho kinase inhibitors (Y-27632), transcription factors (BDNF, NT3), signaling molecules (cAMP), Nogo and LINGO-1 (182). From the point of view of tissue engineering, gene therapy for SCI could be realized in two ways: either transgenic cells delivered by supporting biomaterials as discussed above, or genetically modified tissue engineered biomaterials or scaffolds (183). PLGA scaffold loaded with NT-3 or BDNF encoding Lentivirus, significantly increased density of regenerating axons and myelination (184). A Pluronic F-127 (PF-127) hydrogel encoding Lingo-1 shRNA knocked down Lingo-1 and significantly promoted functional recovery in complete transection SCI rats (185). Other studies also indicate biomaterial-mediated gene delivery could be a promising tool for SCI (186). Tissue engineered biomaterials as a vehicle for delivery of genetic products could become a very valuable tool to manipulate almost every aspect of SCI progression and regeneration.

6. Considerations for Pre-Clinical Study Development

There is obviously a compelling and urgent need for therapies to improve the neurologic outcome for SCI patients. The clinical evaluation of therapies that appear promising in a laboratory setting is a significant challenge, requiring considerable resources and time. Failure in such clinical trials is not only extremely costly but discouraging to the scientific community, patients, and potential investors. The scientific community has witnessed the failure of over 100 potential neuroprotective agents in clinical trials for stroke therapy (187), and this has prompted the establishment of guidelines for the preclinical evaluation of novel treatments (188), with the hope that adherence to a structure for drug development will enhance the rigor of therapies and improve their chances of success in humans.

Such guidelines do not formally exist in the SCI community around the preclinical study of novel therapies. One of the fundamental challenges is that we do not currently know which results in preclinical experiments predict success in human clinical trials. While many animal models exist and much experimentation is conducted in them, their ‘predictive validity’ remains unestablished. Most scientists would agree that treatments should show a robust effect in animal models before moving into human trials, but there is currently no consensus about ‘how much preclinical experimentation is enough’ to reach this threshold of robustness.

We have conducted a series of initiatives to poll the scientific community about this issue, and a number of preclinical considerations for successful translation have emerged from this (189–192). These include the following considerations: A. the use of multiple animal models. Human SCI is extremely heterogeneous, and no animal model or experimental paradigm replicates all aspects of this. Given obvious differences in the size and physiology between humans and rodents, there has been growing interest in the use of large animal and primate models of SCI. In general, there is a perception that a potential treatment is more robust if its efficacy can be demonstrated in more than one animal species. B. the use of different injury models. Again, related to the heterogeneity of human SCI in which the spinal cord can be variably damaged by many different mechanical forces (e.g. distraction, shear, contusion), it is thought that a potential treatment is more robust if its efficacy can be shown in experiments that employ different injury models (e.g. contusion, clip compression). C. the window of therapeutic efficacy. In the human setting, treatments are delivered after some inevitable delay from the time of injury. For neuroprotective agents, the efficacy is often maximal when administered before or after the time of injury. While many drugs have been shown to be efficacious in this experimental paradigm, it obviously is quite different from human reality. Treatments should therefore be shown to be efficacious in experimental studies when administered after some sort of delay from the time of injury. One important and unresolved question is how a 1-hour post-injury delay in a rodent SCI model translates into the duration of treatment delay for a human SCI patient – is it equivalent to 1 hour? 4 hours? 8 hours? Nevertheless, it is clear that treatments should be expected to work in animal models with some length of an intervention delay, and if not, this should be addressed prior to human translation. D. the demonstration of clinically meaningful efficacy: It is in many ways challenging to know what sort of treatment response in animals is ‘clinically meaningful’. Preclinical studies often identify subtle yet ‘statistically significant’ changes in behavior or non-behavioral outcomes. Generally speaking, the field views behavioral recovery to be a critical component of the demonstration of efficacy, particularly when accompanied by supportive histologic outcomes. When viewing rodent studies in particular, there is a desire to observe not just ‘statistically significant’ changes but changes in which obvious changes in locomotion are evident. One of the difficulties in rodent behavior is that even after the most severe contusion type injuries, the animals recover a considerable amount of lower extremity movement, which is quite unlike human patients. E. the demonstration of a dose-response effect: There are two issues with dose-response: establishing that efficacy is ‘dose-dependent’ (which suggests that the efficacy is indeed attributable to the therapy) and establishing the efficacy can be achieved with realistic human doses. This is a significant consideration for drug therapies, and to some extent with cell therapies as well, where an increasing “dose” of the cells typically involves a greater volume of injection into the spinal cord. F. the pharmacokinetics of therapy: Many therapeutic agents (e.g. neuronal growth factors or protective agents) have poor biological stability or pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics characteristics, and hence are not effective in providing therapeutic dose or maintaining their effect at the trauma site to promote regeneration and recovery. A comprehensive mechanistic understanding of the therapy is necessary to better modulate and anticipate the resulting biological response. It is important to monitor changes in the metabolism of the therapeutic drug to better infer its safety and efficacy. G. overcoming drug resistance: P-glycoprotein (Pgp) expression well known for its over-expression and pharmacoresistance in treatments aimed towards neurological diseases that are characterized by oxidative stress, inflammation and excitotoxicity (193, 194). Several drugs that have been assessed for SCI treatment are substrates of Pgp such as MP, riluzole and minocycline. Therefore it is conceivable to evaluate the possibility that the spinal cord can develop resistance towards Pgp thereby reducing the treatment efficacy. Dulin et al. tested this hypothesis in a contusion SCI model and observed a progressive spread of Pgp expression from 72 h up to 10 months post-SCI, which mediated a significant decline in riluzole uptake (194).

These are some of the important considerations for the preclinical development of novel therapies. Table 3 summarizes these various criteria needed for pre-clinical study design. The SCI community is currently engaged in discussions about what constitutes ‘enough’ preclinical research to justify moving forward with clinical trials, and it is expected that guidance in this important area of translation will evolve over time. Fundamentally, the community wishes to avoid the scenario of looking back at the conclusion of a failed clinical trial and wishing that basic considerations (like dose or time window of intervention) had been tested prior to initiating clinical trials.

Table 3.

Considerations for pre-clinical study design and development

| Parameters/Characteristics/Criteria for study design and to evaluate treatment efficacy | Considerations to be taken into account |

|---|---|

| Use of multiple animal models | Treatment should be tested in more than one animal |

| Use of different injury models | Treatment should be tested on different types of spinal cord injuries, e.g. cervical, contusion, clip compression etc. |

| Window of treatment | Treatment should remain efficacious with delayed administration, e.g. 1h, 3h, 6h post-SCI |

| Clinically meaningful efficacy | Treatment should be able to demonstrate significant, obvious improvements in locomotion, behavioral and non-behavioral aspects |

| Dose-response effect of therapy | Treatment doses should be realistically translatable when used in humans and efficacy should be dose- dependent |

| Pharmacokinetics of therapy | Mechanistic understanding of the treatment (pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics) should be determined, e.g. stability, release profile, metabolism changes |

| Overcoming drug resistance | Ensure that the spinal cord has not developed resistance to the drug therapy |

7. Future Outlook and Challenges

Substantial progress has been made in understanding the myriad pathological consequences after SCI as well as the advantages and limitations of various therapeutic interventions. The first challenge is to effectively inhibit the spread of secondary injury cascades. The second challenge is regeneration of the injured spinal cord and re-establishing neuronal connectivity. Since the pathology of SCI is dynamic and evolving in nature with continuous interplay between various molecular and biochemical events, treatments that are aimed at controlling just one aspect of these events are unable to regulate and control the concomitant pathways that indirectly or directly may impact the chosen pathway. A combinative approach employing the dual neuroprotective and neuroregenerative mechanisms, thus targeting multiple pathways, can provide a promising and optimal approach for the treatment of SCI. In this regard, drug delivery systems can play an important role as it can enhance drug bioavailability and specificity, sustain drug effect, can be designed to delivery combination of drugs, and mitigate serious side effects. Many of the potential therapies which have shown efficacy in preclinical studies are precluded from human studies because of unacceptable doses due to toxicity concern or unfavorable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic parameters, or very short half-life that requires unacceptable dosing regimens for human studies. These issues could potentially be addressed by designating appropriate drug delivery systems. Further, certain drug delivery systems can play a dual role of controlling delivery of neuroprotective and neurogenerative therapeutics as well as acting as a scaffold for tissue engineering and cell-based therapies to promote regeneration. While some level of spontaneous recovery does occur after SCI, the intrinsic regeneration ability of the CNS is fairly limited after trauma due to the hostile microenvironment around the lesion site. Therefore, a more articulated approach that could potentially target different degenerative pathways as well as create favorable conditions for stimulating endogenous repair mechanism, in addition to exogenous treatment such as cell-based and tissue engineering approaches, in combination with growth factors and neuroprotective agents, could potentially provide an opportunity to facilitate regeneration and achieve functional restoration after SCI.

Acknowledgments

The study described in this review from author’s laboratory was funded by grant R01NS092033 (to VL) from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- SCI

Spinal Cord Injury

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- BSCB

Blood-spinal cord barrier

- EPO

Erythropoietin

- NSAID

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- MP

Methylprednisolone

- FDA

Food & Drug Administration

- IL-10

Interleukin-10

- ChABC

Chondroitinase ABC

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- CAT

Catalase

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- CAT

Catalase

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- PLGA

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- FA

Ferulic acid

- GC

Glycol chitosan

- GDNF

Glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor

- OEC

Olfactory-ensheathing cells

- NPC

Neural progenitor cells

- NSC

Neural stem cells

- iPSC

Induced pluripotent stem cells

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem cells

- FT

Filum terminale

- HGF

Hepatic growth factor

- NS N

Neural sphere

- ESC

Embryonic stem cells

- OPC

Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells

- OMC

Olfactory mucosa cells

- CSF

Colony stimulating factor

- SCF

Stem cell factor

- SC

Schwann cells

- PDA

Pre-differentiated astrocyte

- HA

Hyaluronic acid

- PCL

Poly-ε-caprolactone

- PHEMA

Poly hydroxethyl methacrylate

- PVA

Poly vinyl alcohol

- PHPMA

Poly hydroxypropyl methacrylate

- SAPN

Self-assembling (peptide) nanofibers

- SDF-1

Stromal cell-derived factor-1

- NGF

Nerve growth factors

- PSA-NCAM

Plasticity-associated polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule

- TF

Transcription factors

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Vinod Labhasetwar is a Co-Founder and Chief Scientific Officer of ProTransit Nanotherapy (http://www.protransitnanotherapy.com/), a start-up company established based on the technologies developed at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (Omaha, NE), his former institution and Cleveland Clinic, his current institution. If the technology described in this review from his laboratory is successful, the author and both the institutions may benefit. The conflict of interest is managed by the Conflict of Interest Committee of Cleveland Clinic in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Simonato M, Bennett J, Boulis NM, Castro MG, Fink DJ, Goins WF, et al. Progress in gene therapy for neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(5):277–91. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spinal Cord Injury Facts & Figures at a Glance. National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center (NSCISC); 2013. [05/20/2015]. Available from: https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/PublicDocuments/fact_figures_docs/Facts%202013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoenfeld AJ, Laughlin MD, McCriskin BJ, Bader JO, Waterman BR, Belmont PJ., Jr Spinal injuries in United States military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: an epidemiological investigation involving 7877 combat casualties from 2005 to 2009. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38(20):1770–8. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31829ef226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell CM, Choo AM, Tetzlaff W, Chung TE, Oxland TR. Maximum principal strain correlates with spinal cord tissue damage in contusion and dislocation injuries in the rat cervical spine. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(8):1574–85. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choo AM, Liu J, Dvorak M, Tetzlaff W, Oxland TR. Secondary pathology following contusion, dislocation, and distraction spinal cord injuries. Exp Neurol. 2008;212(2):490–506. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald JW, Sadowsky C. Spinal-cord injury. Lancet. 2002;359(9304):417–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werndle MC, Saadoun S, Phang I, Czosnyka M, Varsos GV, Czosnyka ZH, et al. Monitoring of spinal cord perfusion pressure in acute spinal cord injury: initial findings of the injured spinal cord pressure evaluation study*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(3):646–55. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Springer JE, Azbill RD, Knapp PE. Activation of the caspase-3 apoptotic cascade in traumatic spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 1999;5(8):943–6. doi: 10.1038/11387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silver J, Miller JH. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(2):146–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hausmann ON. Post-traumatic inflammation following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2003;41(7):369–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fawcett JW, Asher RA. The glial scar and central nervous system repair. Brain Res Bull. 1999;49(6):377–91. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerschensteiner M, Schwab ME, Lichtman JW, Misgeld T. In vivo imaging of axonal degeneration and regeneration in the injured spinal cord. Nat Med. 2005;11(5):572–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fehlings MG, Vaccaro A, Wilson JR, Singh A, Cadotte DW, Harrop JS, et al. Early versus delayed decompression for traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: results of the Surgical Timing in Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (STASCIS) PLoS one. 2012;7(2):e32037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon BK, Tetzlaff W, Grauer JN, Beiner J, Vaccaro AR. Pathophysiology and pharmacologic treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Spine J. 2004;4(4):451–64. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamid S, Hayek R. Role of electrical stimulation for rehabilitation and regeneration after spinal cord injury: an overview. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(9):1256–69. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0729-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thuret S, Moon LD, Gage FH. Therapeutic interventions after spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(8):628–43. doi: 10.1038/nrn1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi F, Perale G, Papa S, Forloni G, Veglianese P. Current options for drug delivery to the spinal cord. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2013;10(3):385–96. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.751372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballabh P, Braun A, Nedergaard M. The blood-brain barrier: an overview: structure, regulation, and clinical implications. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiseman DB, Dailey AT, Lundin D, Zhou J, Lipson A, Falicov A, et al. Magnesium efficacy in a rat spinal cord injury model Laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg-Spine. 2009;10(4):308–14. doi: 10.3171/spi.2009.10.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donaghue IE, Tam R, Sefton MV, Shoichet MS. Cell and biomolecule delivery for tissue repair and regeneration in the central nervous system. J Control Release. 2014;190:219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones LL, Tuszynski MH. Chronic intrathecal infusions after spinal cord injury cause scarring and compression. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;54(5):317–24. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming JC, Norenberg MD, Ramsay DA, Dekaban GA, Marcillo AE, Saenz AD, et al. The cellular inflammatory response in human spinal cords after injury. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 12):3249–69. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon BK, Okon E, Hillyer J, Mann C, Baptiste D, Weaver LC, et al. A systematic review of non-invasive pharmacologic neuroprotective treatments for acute spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28(8):1545–88. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saltzman JW, Battaglino R, Stott H, Morse LR. Neurotoxic or Neuroprotective? Current Controversies in SCI-Induced Autoimmunity. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2013;1(3):174–7. doi: 10.1007/s40141-013-0021-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, Holford TR, Young W, Baskin DS, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(20):1405–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005173222001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bydon M, Lin J, Macki M, Gokaslan ZL, Bydon A. The current role of steroids in acute spinal cord injury. World neurosurg. 2014;82(5):848–54. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KD, Chow WN, Sato-Bigbee C, Graf MR, Graham RS, Colello RJ, et al. FTY720 reduces inflammation and promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(12):2335–44. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abrams MB, Nilsson I, Lewandowski SA, Kjell J, Codeluppi S, Olson L, et al. Imatinib enhances functional outcome after spinal cord injury. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pannu R, Christie DK, Barbosa E, Singh I, Singh AK. Post-trauma Lipitor treatment prevents endothelial dysfunction, facilitates neuroprotection, and promotes locomotor recovery following spinal cord injury. J Neurochem. 2007;101(1):182–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaal SM, Garg MS, Ghosh M, Lovera L, Lopez M, Patel M, et al. The therapeutic profile of rolipram, PDE target and mechanism of action as a neuroprotectant following spinal cord injury. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e43634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iannotti CA, Clark M, Horn KP, van Rooijen N, Silver J, Steinmetz MP. A combination immunomodulatory treatment promotes neuroprotection and locomotor recovery after contusion SCI. Exp Neurol. 2011;230(1):3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson CD, Zurko JC, Hanna BF, Hellenbrand DJ, Hanna A. The therapeutic role of interleukin-10 after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(15):1311–24. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abraham KE, McMillen D, Brewer KL. The effects of endogenous interleukin-10 on gray matter damage and the development of pain behaviors following excitotoxic spinal cord injury in the mouse. Neuroscience. 2004;124(4):945–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plunkett JA, Yu CG, Easton JM, Bethea JR, Yezierski RP. Effects of interleukin-10 (IL-10) on pain behavior and gene expression following excitotoxic spinal cord injury in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2001;168(1):144–54. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matis GK, Birbilis TA. Erythropoietin in spinal cord injury. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(3):314–23. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0829-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gensel JC, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Spinal cord injury therapies in humans: an overview of current clinical trials and their potential effects on intrinsic CNS macrophages. Expert Opin Ther Tar. 2011;15(4):505–18. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.553605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaptanoglu E, Solaroglu I, Okutan O, Surucu HS, Akbiyik F, Beskonakli E. Erythropoietin exerts neuroprotection after acute spinal cord injury in rats: effect on lipid peroxidation and early ultrastructural findings. Neurosurg Rev. 2004;27(2):113–20. doi: 10.1007/s10143-003-0300-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradbury EJ, Moon LD, Popat RJ, King VR, Bennett GS, Patel PN, et al. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature. 2002;416(6881):636–40. doi: 10.1038/416636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]