Abstract

Synthetic polymers play a critical role in pharmaceutical discovery and development. Current research and applications of pharmaceutical polymers are mainly focused on their functions as excipients and inert carriers of other pharmacologically active agents. This review article surveys recent advances in alternative pharmaceutical use of polymers as pharmacologically active agents known as polymeric drugs. Emphasis is placed on the benefits of polymeric drugs that are associated with their macromolecular character and their ability to explore biologically relevant multivalency processes. We discuss the main therapeutic uses of polymeric drugs as sequestrants, antimicrobials, antivirals, and anticancer and anti-inflammatory agents.

Keywords: Polymeric drugs, Drug delivery, Polymer therapeutics, Dendrimers, Multivalency, Polymeric sequestrants, Antimicrobials, Antivirals, Gene delivery, SiRNA delivery, Cancer, Tumor delivery

1. Introduction

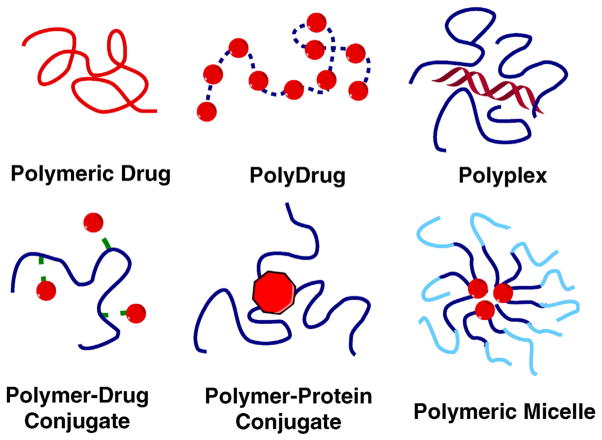

Synthetic and natural polymers play a vital part in pharmaceutical research and development. Pharmaceutical applications of polymers range from inert bulk excipients to sophisticated drug delivery technologies. Currently, polymers are overwhelmingly used in applications in which they are expected to be pharmacologically inactive and simply to aid in the delivery of existing small molecule or macromolecule drugs. Undoubtedly, polymers provide a range of benefits in drug delivery applications that result in improved drug delivery, including controlled release of drugs, adjustable pharmacokinetic and biodistribution profile, and improved drug safety (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Soluble polymers in pharmaceutical applications. Adapted from [13].

In contrast to pharmacologically inert polymers used in most drug delivery applications, polymeric drugs are polymers that exhibit pharmacological activity that can be harnessed for therapeutic benefits [2]. Polymeric drugs have a long history, going back to the 1960s when the first example of a polymeric drug entered clinical trials. Successful examples of polymeric drugs followed both rational discovery processes as in the case of polymeric sequestrants and antimicrobial agents or were the result of serendipitous discoveries as in the case of several excipients and materials previously assumed inert [3].

Despite their current niche status, polymeric drugs can bring multiple potential benefits to drug discovery not readily available with traditional small molecule drugs. Most biological targets explored for therapeutic interventions are macromolecular in nature. Binding to such targets and activation or inhibition of related signaling pathways is often determined by complex set of multivalent interactions. Unlike traditional small molecule drugs, polymers are macromolecules that fall into the size range of proteins and their repeating unit nature allows for easy incorporation of multivalent features on size scales not accessible to small molecules.

This review provides a perspective on the current state-of-the-art of the field of polymeric drugs. We focus on the design principles of synthetic polymers as applied to the current main disease areas of applications.

2. Multivalency as key feature of polymeric drugs

Biological multivalent interactions are defined as simultaneous binding between multiple ligands on one molecular or biological entity (e.g. proteins, polymer, cell, virus) and multiple corresponding receptors on another. Multivalent interactions are characteristic features of many biological processes, including attachment of viruses and bacteria to the surface of a host cell, interactions between antigens and macrophages, cell–cell interactions, and binding between transcription factors and DNA [4,5]. These interactions are reversible and occur in both activation and inhibition biological processes. In contrast to weak monovalent receptor-ligand binding, multivalent interactions generally amplify signaling transduction followed by significantly pronounced downstream activity. Such augmentation is due to enhanced affinity, cooperativity, and favorable entropy [1,4,6].

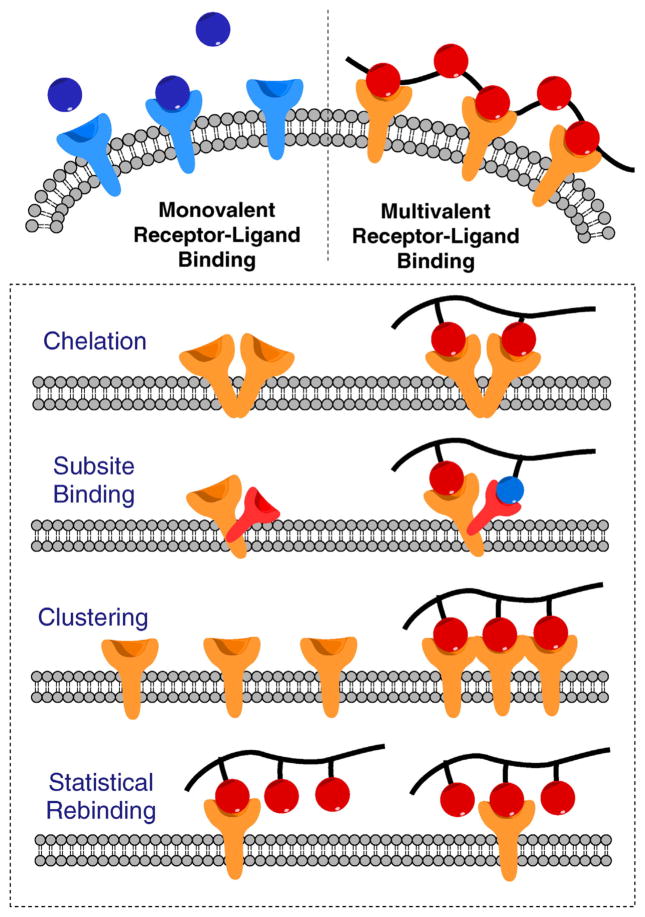

Outside of exploiting multivalency in simple applications such as polymeric sequestrants, polymeric drugs that contain multiple ligands to mimic the multivalent ligands in nature offer significant therapeutic potential (Scheme 2). Targeting multivalent receptors using small molecule drugs often requires high doses or frequent dosing regimens. More importantly, many multivalent receptors are simply not accessible for monovalent small molecule drugs. In situations where receptors require chelation mode or clustering actions for binding, small molecule (i.e., monomeric) drugs generally exhibit only marginal activity [7]. Some receptors have more than one binding pocket where monovalent drugs can only access the primary binding sites [8]. Polymeric drugs presenting multiple ligands however, can easily act simultaneously on multiple receptors or different binding subsites of one receptor. Even when the receptors are physically not close enough to be bridged by a synthetic macromolecule, a polymeric drug can still offer benefits via the mechanism of statistical rebinding. As soon as one ligand dissociates from the receptor, the adjacent ligands on the same polymer chain can bind the receptor. This process is more energy efficient than recruiting another small molecule, resulting in longer residence time of the polymeric drugs. In addition, polymeric drugs can also create steric stabilization effect in which the bulky nature of the polymers can prevent the interactions with detrimental biological entities (e.g. viruses) [9,10]. All these unique advantages of multivalent polymeric drugs may lead to faster, longer and superior pharmacological effect compared with small molecule drugs.

Scheme 2.

Monovalent vs. multivalent receptor–ligand interactions. Adapted from [1].

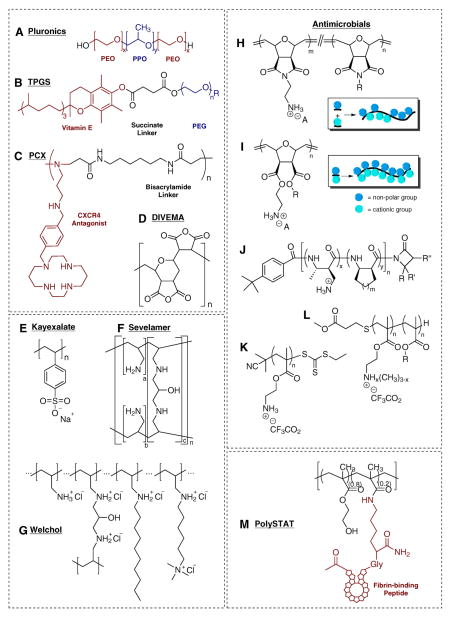

In order to take advantage of multivalency in designing polymeric drugs, one has to take into account a number of key factors, including i) the binding affinity, strength and length of a single ligand to the target receptor; ii) the number, spatial distance and three-dimensional arrangement of multiple ligands in one polymeric system; iii) the presentation and accessibility of the ligands; and iv) the potential changes to the polymer after multivalent interactions between the ligands and the target receptors [4,6]. Most of these considerations can be addressed by selecting proper molecular weights, structure and architecture of the polymers, and by appropriate selection of linkers and spacers to achieve maximum therapeutic outcomes [11]. The most widely used polymer scaffolds include linear polymers, dendrimers, dendronized polymers, polypeptides, and nanogels [12]. Among all the polymeric scaffolds, linear polymers with multiple pendent ligands were the first applied as multivalent polymeric drugs due to their flexibility and ease of controlling the ligand density and polymer chain length. Chemical structures of selected examples of polymeric drugs discussed in this review are summarized in Scheme 3.

Scheme 3.

Chemical structures of selected examples of polymeric drugs (adapted from [137]).

3. Polymeric drugs in cancer treatment

Remarkably, the first anticancer polymeric drug, a copolymer of divinyl ether and maleic anhydride (DIVEMA) (Scheme 3D), entered clinical trials in the early 1960s [13]. Although it failed due to its severe systemic toxicity, DIVEMA marked the start of a new chapter as the earliest polymeric drug discovered for its anticancer activity [14]. Yet, despite the early efforts and even with clinical advances in related fields of polymer–drug conjugates and polymer–protein conjugates, there are currently no anticancer polymeric drugs used in the clinical practice.

3.1. Polymeric drugs with anticancer activity

The early development of DIVEMA has inspired testing of anticancer activity of variety of synthetic polymers, including poly(maleic anhydride), poly(acrylic acid–maleic anhydride) copolymers [15], poly(acrylic acid), poly(vinyl sulfate), and poly(amido amine)s [16,17]. Many of these polymers exhibited significant antitumor activity and prolonged survival in animal models either by direct toxicity to tumor cells or indirectly by activation of the immune system. Although some of these polymers entered (and failed) clinical trials, most of them remained in preclinical stages of development due to concerns about their toxicity, low efficacy, and ambiguous mechanism of action.

Discovery of cancer-specific biomarkers and their ligands promoted improved, multivalency-based design of anticancer polymeric drugs with enhanced therapeutic effect. For example, the Kopeček lab developed a series of polymeric drugs that induce apoptosis by cross-linking antigens on the cell surface [18–21]. CD20 is a known biomarker on Raji B cells of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and clustering of this non-internalizing receptor initiates apoptosis. A pair of oppositely charged pentaheptad peptides (CCE and CCK) that form antiparallel coiled-coil heterodimers was applied as a specific bio-recognition cross-linker [18]. CD20+ B cells were first bound with Fab′ fragment of CD20 antibody with a CCE peptide tail (Fab′-CCE), followed by further exposure to multivalent CCK-grafted N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymer (CCK-P). The self-assembly of CCE-CCK hybrid coiled-coil heterodimer triggered the cross-linking and clustering of the receptors (Scheme 2), resulting in cell death. Intravenous administration of Fab′-CCE followed by CCK-P enhanced the survival in SCID mice bearing human B cell NHL xenografts [19]. The approach was further explored by using hybridization of complementary morpholino oligonucleotides (MORF) to mediate the biorecognition [20]. The two components in the system, Fab′-oligoMORF1 conjugate and multivalent oligoMORF2-grafted HPMA copolymer, either administered consecutively or simultaneously, greatly reduced tumor burden in various organs and significantly prolonged survival in a systemic B cell NHL mouse model.

Other polymeric drugs that utilize ligand multivalency have been reported. Lamanna et al. have conjugated an apoptotic peptide that mimics the natural tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) by using adamantane-based dendrons as multivalent scaffolds [22]. The dendronized peptides exhibited markedly enhanced binding affinity to human TRAIL receptor 2 (TR2) when compared with the peptide alone. The binding affinity was highly correlated with the dendron generation and the number of the peptide ligands, as the trimer exhibited 1500-fold higher affinity than the monomer. The multivalent design was essential for triggering selective apoptosis in TR2+ BJAB lymphoma cells, as the monomer caused only marginal cell death. Maynard et al. have developed a linear norbornene copolymers substituted with two different oligopeptides that synergistically inhibited cell adhesion via limiting integrin-extracellular matrix protein interactions, showing promise for cancer treatment [23]. Development of polymeric drugs that inhibit chemokine receptor CXCR4 has been reported by several labs recently and promoted for their antimetastatic properties. The Kopeček lab reported multivalent HPMA copolymer with a CXCR4 inhibiting peptide BKT140 and showed considerably higher inhibitory activity than the free peptide [24]. The Oupicky lab reported multivalent polymeric CXCR4 inhibitors based on cyclam-containing poly(amido amine)s with promising activity in experimental model of pulmonary metastasis in mice [25].

3.2. Polymeric drugs as carriers for combination cancer treatment

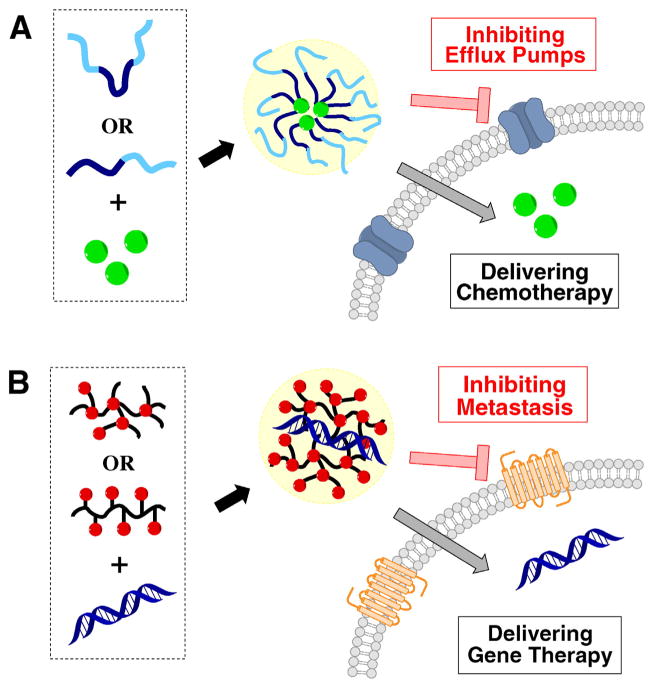

Cancer involves dynamic changes in the genome and a complex network of interactions among cancer cells and multiple cell types that form tumors. As a result, combination treatments have been proven highly effective due to their ability to affect multiple pathways involved in cancer [26]. The use of polymeric drugs both for their pharmacologic activity and for their ability to deliver existing drugs emerged as a viable strategy to combination cancer treatment. The most developed and understood dual use of polymeric drugs in combination cancer treatment is based on the work of the Kabanov lab on Pluronic block copolymers (Scheme 3A) and their micelles [27]. Pluronic micelles can solubilize and improve delivery of anticancer drugs like doxorubicin. In addition, the copolymers chemosensitize cancer cells due to their ability to inhibit drug efflux transporters such as P-gp found in multidrug-resistant (MDR) cancers [28,29]. Poly(ethylene glycol) derivative of D-α-tocopheryl (TPGS) (Scheme 3B) is a recent example of another pharmacologically active polymeric surfactant successfully used in anticancer drug delivery [30]. TPGS forms stable polymeric micelles and has been widely utilized for emulsifying, dispersing, and solubilizing poorly water-soluble drugs. As a polymeric derivative of vitamin E, TPGS has been approved by the FDA as pharmaceutical adjuvant [31]. Recently, TPGS has been recognized as a P-gp inhibitor to reverse MDR against a number of chemotherapy drugs including doxorubicin, vinblastine, paclitaxel, and colchicine [32]. Liu et al. developed paclitaxel nanocrystals using TPGS as the sole excipient to stabilize the nanocrystals and to overcome MDR in paclitaxel-resistant cancer cells and tumor models in vivo [33]. Zhu et al. also reported the dual functionality of TPGS in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles as a pore-forming agent and stabilizer that resulted in small particle size, high encapsulation efficiency and fast release of docetaxel and P-gp inhibition to overcome MDR in vivo [34] (Scheme 4A). Increasing number of similar formulations have incorporated TPGS to deliver anti-cancer drugs in multidrug resistant cancers [35–41]. Similar concept of pharmacologically active polymer surfactant using embelin, a known inhibitor of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein, was recently advanced by the Li lab [42,43].

Scheme 4.

Dual-function polymeric drugs to deliver combination anticancer therapy, such as A) pluronics or TPGS to deliver chemotherapy and function as inhibitors of efflux pumps to overcome MDR, or B) polymeric CXCR4 antagonists (PCX) to deliver gene therapy and inhibit cancer metastasis.

In addition to potentiating activity of small molecule drugs, polymeric drugs have a potential to improve activity of various anticancer gene and nucleotide therapies. Despite enormous promise, approaches based on therapeutic use of nucleotides (i.e., DNA, mRNA, siRNA, microRNA) have largely failed to advance clinical treatment of cancer. Nucleic acid delivery systems based on polycations have been subject of intensive research as safer alternatives to various viral vectors. Probably the first example of a use of polycations as polymeric drugs to deliver therapeutic genes has been reported by the Schätzlein lab in 2005 [44]. The authors demonstrated that poly(propylene imine) (PPI) dendrimers efficiently delivered TNFα plasmid and prolonged survival after systemic administration in several xenograft mouse cancer models. Interestingly, the antitumor activity was to a large extent attributed to the PPI dendrimers rather than the expressed TNFα gene. Other common polycations for gene delivery such as poly(ethylenimine) (PEI), and polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers also exhibited considerable effects on tumor regression [44]. These findings showed that the combination of cancer-targeted gene therapy with pharmacologically active polycations provides opportunities to create more efficient gene therapy.

Our group has recently reported the synthesis and development of a series of polymeric drugs that function dually as (i) polymeric antagonists of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and (ii) delivery vectors of therapeutic nucleic acids (e.g. DNA, siRNA) [25,45–48]. Mounting preclinical and clinical evidence has highlighted the critical role of CXCR4 and its chemokine ligand SDF-1 in initiating and regulating cancer invasion and metastasis. Blocking the CXCR4/SDF-1 axis by CXCR4 antagonists could effectively limit metastatic spread. Hence we have developed two generations of dual-function polymeric CXCR4 antagonists named PCX (Scheme 4B). The first generation of PCX was synthesized by direct copolymerization of an FDA-approved bicyclam CXCR4 antagonist Plerixafor (AMD3100) and a bisacrylamide linker. The more recent second generation PCX used a Boc-protected monocyclam CXCR4 antagonist to replace Plerixafor to create a linear polycation with multiple pendent CXCR4 ligands in the side chain (Scheme 3C). As a polymeric drug, PCX showed greatly enhanced CXCR4 inhibiting potency compared with the parent monomer drug, due to better presentation of the drug and the multivalent interactions (most likely due to statistical rebinding as illustrated in Scheme 2). PCX displayed anti-metastatic activity in an experimental metastatic mouse melanoma model [25] and was the first reported polymeric drug with the potential to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells in vivo [45]. In addition, both generations of PCX could form nanosized polyplexes with therapeutic nucleic acids via electrostatic interactions to mediate transfection and deliver gene therapy simultaneously. These dual-function delivery vectors represent great promise to enhance antimetastatic efficacy of a variety of cancer gene therapy methods.

4. Polymeric sequestrants

A variety of potentially harmful molecules either from the environment or diet, or generated endogenously can accumulate in the human body and cause diseases [49]. Effective and safe elimination of these species using polymers as functional sequestrants represents effective and clinically proven therapeutic strategy. Due to their macromolecular multivalent nature, such polymeric drugs demonstrate outstanding capacity and efficiency in removal of multiple target molecules. The polymers can exhibit high binding selectivity adjustable by changing their size, structure, and presence and distribution of functional groups. When given orally, these polymeric drugs are typically not absorbed in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, resulting in no or minimal toxicity [49–52]. In this section, we will summarize recent advances of polymeric drugs that act as molecular sequestrants. The chemistry of these polymeric sequestrants is highly dependent on the structure of the substrate, the charge balance and complexity of the target molecule. The main types of current polymeric sequestrants are summarized in Scheme 5.

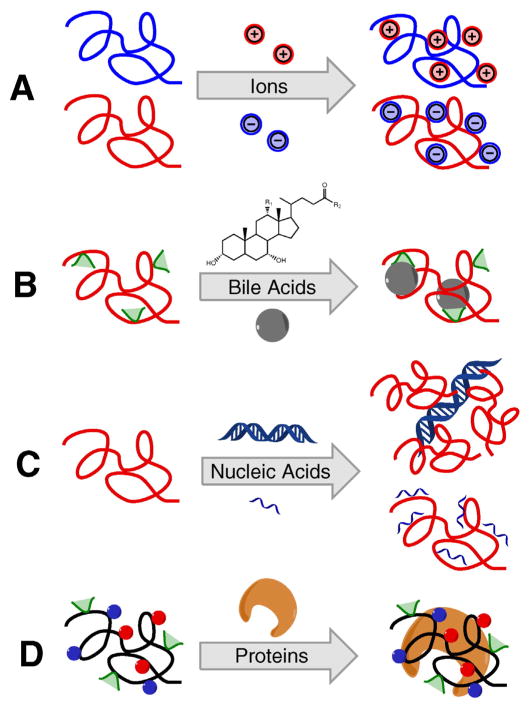

Scheme 5.

General mechanism of actions of polymeric sequestrants for binding excessive A) ions, B) bile acids, C) nucleic acids and D) proteins.

4.1. Polymeric sequestrants of inorganic ions

Excessive exposure to and accumulation of ions such as potassium, phosphate, iron and cadmium in human bodies could lead to lethal conditions such as electrolytic disorders and heavy metal intoxication. These ion-overload conditions are particularly severe in patients with kidney dysfunction, with failure to regulate ion absorption and elimination. The sequestration of these ions by polymeric drugs can be achieved via a number of different mechanisms including coordination interactions, ion-ion interactions, hydrogen bonding, and ion-aromatic interactions [53,54]. Incorporating more than one mechanism of interactions is often applied to improve binding specificity.

One of the earliest examples of polymeric sequestrants is Kayexalate®, which was approved by the FDA in 1958. It is a cation-exchange resin of sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Scheme 3E) to treat hyperkalemia (high levels of potassium in the blood that cause abnormal heart rhythm). The cross-linked polymer resin containing sodium is given orally or rectally, and used to exchange for excessive potassium in the GI tract. The formed insoluble potassium polystyrene sulfonate complexes are removed by fecal excretion, preventing potassium re-absorption into the blood and lowering serum potassium levels [55].

Hyperphosphatemia represents another severe electrolytic disorder with excessive serum phosphate levels in patients, especially those with kidney failure and undergoing dialysis. It is challenging to maintain a fine balance between dietary restriction of phosphorus and adequate daily protein uptake [56–58]. The administration of phosphate binders provides a more efficient and patient-friendly alternative treatment strategy to achieve optimal phosphate equilibrium. Several phosphate binders based on cationic metals such as lanthanum, aluminum, magnesium and calcium showed clinical efficacy, however many of them induced neurologic toxicity or metal ion overload [58,59]. The development of amine-based polycations represents a safer approach to reduce dietary phosphates in the GI tract. Sevelamer hydrochloride (Renagel®) was the first polycationic drug approved by the FDA (1998) to treat hyperphosphatemia by oral administration. It is composed of a copolymer of allylamine crosslinked with epichlorohydrin (Scheme 3F). The multiple amine groups in the polycation become partially protonated in the intestines and sequester abundant phosphate anions via ion-ion interactions and hydrogen bonding [60,61]. A number of similar amine-based polymeric sequestrants became available on the market as oral formulations, including sevelamer carbonate (Renvela®), colestilan (BindRen®) and bixalomer (Kiklin®) [62,63]. Despite their wide clinical applications, these polycationic sequestrants interact with a broad range of anionic substrates in the GI tract such as bile acids and various vitamins, which may lead to vitamin deficiency and other side effects. To enhance binding specificity, several polymeric sequestrants are under development. Inoue et al. have synthesized a cross-linked poly(allylamine) named TRK-390 that showed superior binding selectivity for phosphate, with low binding to fatty acids and bile acids [64,65]. Vidasym Inc. has developed a novel polymeric phosphate binder VS-501 that overcomes safety concerns and effectively decreases phosphate without disrupting calcium homeostasis [66]. In addition, chitosan loaded in chewing gum has emerged as a novel salivary phosphorous binder as an alternative and currently under clinical development [67].

Iron overload, also known as hemochromatosis, gives rise to a number of pathological conditions including liver cirrhosis, diabetes, cardiomyopathy and arthritis. Patients have been traditionally treated with frequent or continuous intravenous or subcutaneous dosing of deferoxamine (DFO), a small molecule iron chelator. Low patient compliance prompted development of multiple alternative approaches by conjugating small molecule iron-chelators to polymers to either improve pharmacokinetics and safety profiles or enhance coordination interactions. Several research groups have attempted to attach DFO to various biocompatible polymers, including dextran, hydroxyethyl-starch [68], PEG [69] and hyperbranched polyglycerol [70] to prolong the blood circulation time. Zhou et al. have developed a series of brushed or dendritic polymeric iron sequestrants terminated with hexadentate ligands formed from hydroxypyridinone, hydroxypyranone, and catechol and showed high selectivity for iron(III) [71,72]. Later studies revealed that polymeric sequestrants based on the hydroxypyridinone hexadentate (CP254) provide the optimum coordination interactions with iron (III) to form highly stable complexes [72,73]. Similar approaches using polymers modified with various iron-chelating motifs were reported and shown in vivo iron-binding capability in rats when given orally [74,75]. This strategy has also been extended to other metals such as aluminum, cadmium, and lead [54,76–78]. Haratake et al. have recently reported the synthesis of a hydrophilic porous polymer with phosphonic acid groups and evaluated its capability to sequester radioactive strontium-90 as post-exposure first-aid treatment in rats via oral administration [79]. In spite of all the advances mentioned above, the market is still awaiting the first polymeric drug product for heavy metal ion detoxification.

4.2. Polymeric sequestrants of bile acids

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death around the globe. High cholesterol levels in the blood, especially high level of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, is associated with elevated risk of cardiovascular disease. Bile acids are effective targets for lowering the cholesterol since cholesterol is transformed into bile acids in the liver and clearance of bile acids promotes biosynthesis of more bile acids from circulating cholesterol to maintain normal levels [50, 80,81]. In contrast to ion sequestration where the binding mostly relies on electrostatic interactions and coordination bonding, organic small molecule substrates exhibit more structural complexity, making it possible to achieve higher binding affinity and specificity [52,54]. Cholestyramine (Questran®) was the first approved orally given bile-acid sequestrant based on anion exchange resin composed of ammonium-modified styrene-divinylbenzene copolymer. A number of polycationic bile acid sequestrants have become available since then, including colestipol (Colestid®), colestilan (BindRen®) (also approved as phosphate sequestrant), and colextran based on cationized dextran [82,83]. Although these polymeric drugs exhibited satisfactory therapeutic outcomes, the clinical efficacy is relatively low due to their weak competition against active bile acid transporter system in the GI tract [50]. This has inspired the development of colesevelam hydrochloride (Welchol®), which has become the most successful polymeric sequestrant of bile acids. Colesevam is based on hydrophobically and cationically modified crosslinked poly(allylamine) (Scheme 3G). The presence of the hydrophobic decyl groups provides secondary binding force and considerably enhances the potency. Colestimide (Cholebine®) is another successful example of such design. Today, continuing efforts are dedicated to advancing the binding capacity and affinity, as well as the safety of the polymeric bile acid sequestrants. When designing bile acid sequestrants, a few considerations need to be taken into account: i) presence of cationic groups at a proper density to ensure the electrostatic interactions with the anionic bile acids; ii) presence of hydrophobic moieties to attract the steroid skeleton of bile acids.

4.3. Polymeric sequestrants of nucleic acids

Circulating nucleic acids could potentially cause a number of pathological conditions such as inflammation. The adverse effects can be caused by nucleic acids produced as a result of endogenous processes like cell metabolism, cell death or as a result of exogenously introduced nucleic acids. Most current approaches to nucleic acid sequestration take advantage of abundant positive charges on polycations to bind and remove the negatively charged nucleic acids. The first study that explored the potential of polycations as nucleic acid sequestrants was in removal of therapeutic RNA aptamers used as anticoagulants during surgery [84]. An efficient antidote was required to counteract the aptamer activity after surgery. Complementary oligonucleotides that form stable double-stranded complexes showed promise but there were concerns about the manufacturing costs and presence of circulating RNA complexes [85,86]. An alternative strategy was to use polycations as polymeric sequestrants to capture the circulating aptamers. A library of polycations that have been traditionally used for gene delivery was screened for aptamer binding affinity. Several candidates including G3 PAMAM dendrimer and cyclodextrin-containing polycations showed high efficacy to reverse the aptamer anticoagulant activity both in vitro and in vivo via intravenous injection in a pig model [87]. These initial studies also showed that some polycations can be used as anti-inflammatory agents that inhibit activation of multiple nucleic acid-sensing toll-like receptors (TLRs) triggered by extracellular nucleic acid release by dead or dying cells. Systemic administration of the TLR-inhibiting polymers prevented fatal liver injury triggered by proinflammatory nucleic acids in mice [88]. Other irregular immune pathogenesis could also be overcome by the polycations, including systemic lupus erythematosus caused by binding of extracellular DNA and anti-DNA antibodies [89,90]. A recent report showed that topical administration of G3 PAMAM dendrimers could efficiently sequester nucleic acids that cause increase in fibroblast activation and granulation tissue contraction, resulting in decreased pathological scarring during wound healing [91]. In addition, the application of polycations as antithrombotic agents that rapidly remove prothrombotic nucleic acids together with other polyphosphates was also demonstrated in vivo and proposed as a novel strategy to prevent thrombosis after injury [92].

4.4. Polymeric sequestrants of peptides and proteins

Polymeric sequestrants have been designed to incorporate multiple recognition moieties and binding pockets for capturing circulating large complex molecules like proteins via a number of non-covalent interactions. These interactions often lead to high avidity and specificity. Due to the charge heterogeneity of proteins, the selection as well as the density and presentation of the binding moieties on the polymer are often critical for the potency of polymeric drugs. Here, we summarize the recent investigations of polymeric drugs that function as protein sequestrants.

The development of polymeric sequestrants for proteins has been mainly focused on targeting various toxins, many of which are based on multivalent design of glycopolymers, glycodendrimers and glycoclusters [93]. The Bundle lab developed a highly potent macromolecular carbohydrate ligand (named starfish) that binds with Shiga toxin produced by Escherichia coli [7,94]. The multivalent interactions between the ligand and toxin significantly amplify the inhibitory activity. The ligand was later utilized as part of polymeric drugs to further boost its pharmacologic activity and to improve pharmacokinetics after i.v. injection [95,96]. Following similar approach, several labs have prepared a variety of polymers with an inhibitory peptide of anthrax toxin as polymeric sequestrants and showed substantial increase in the efficiency when compared with the single ligand [97–100]. Recently, Hoshino et al. designed a series of polymeric sequestrants bearing various compositions of hydrophobic, anionic and cationic functional groups and studied their structure-activity relationship both in vitro and in vivo following i.v. administration for binding melittin, a toxic peptide from bee venom toxin [101,102]. This study confirmed that optimization of polymer is vital for the efficiency as well as the bio-compatibility. The balance of negative and positive charges presented on the polymer was especially important for the polymer selectivity to bind the target peptide without associating with plasma proteins and cell membranes. A number of polymeric sequestrants for Clostridium difficile toxin have also been developed based on simultaneous multivalent interactions with multiple binding pockets displayed on the toxin molecule [103,104]. Among these, Synsorb 90 and tolevamer have been clinically tested for preventing diarrhea associated with Clostridium difficile infection in the GI tract. However, neither Synsorb 90 nor tolevamer succeeded in recent Phase III clinical trials. The development of tolevamer was halted due to significant drop out of patients in the treated group and the failure of Synsorb 90 was due to insufficient efficacy compared with standard antibiotic treatment [52,105,106].

α-Gliadin is a component of gluten that has been identified as the major cause of celiac disease (CD), a chronic systemic inflammatory disorder in which the body becomes intolerant to gluten [107]. No effective pharmacological therapies are currently available for CD patients [108]. Pinier et al. synthesized copolymers of 2-(hydroxyethyl) methacrylate and styrene sulfonate and used them as α-gliadin binder to reduce inflammation via oral administration in a gluten-sensitized mouse model and ex vivo using tissues from CD patients [109]. Follow-up studies further systematically investigated the mechanism of interactions by analyzing copolymers with different compositions [110–112]. BL-7010 is a polymeric drug candidate based on these copolymers that is currently in Phase I/II clinical development by BioLineRx Ltd.

5. Polymeric drugs with antiviral activity

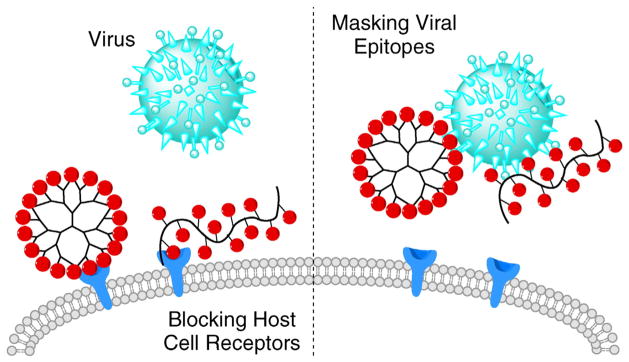

Viruses utilize concerted action of multiple surface epitopes to dock to the host cells and to facilitate cellular entry, replication of their own genetic material, and assembly of new virus particles to complete a typical viral replication cycle. Unlike small-molecule antivirals that can intervene at different stages of the viral replication (e.g. entry inhibitors, fusion inhibitors, reverse transcriptase inhibitors, integrase inhibitors) [113], antiviral polymeric drugs have been developed mainly based on interfering with the virus interactions with the host cell. Due to the high molecular weight and multivalent binding, polymers exert their antiviral activity by steric shielding of the viral surface or competitive inhibition of the interactions [52,54]. The latter could be achieved via receptors essential for viral docking and entry, either through polymer binding to the virus or the host cell, both of which leads to decreased viral entry (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Antiviral polymeric drugs inhibit viral entry by blocking interactions between the virus and the host cell.

5.1. Polymeric drugs against influenza

The Whitesides lab reported linear polyacrylamides with pendent sialic acid (SA) groups that strongly inhibited agglutination of erythrocytes by influenza virus caused by the multivalent interactions between SA and its receptor hemagglutinin (HA) [10]. The polymeric inhibitors with various molecular weights exhibited a thousand- to a million-fold higher binding affinity with the viral surface than the monomer. A follow-up study using a library of acrylic acid copolymers with SA side chains attached via different linkers showed that hydrophobic linkers greatly enhanced the multivalent binding and the antiviral activity [114]. Promising in vivo antiviral activity against H1N1 was reported subsequently [115]. Similarly, dendrimer nanogels with sizes similar to influenza virus were decorated with SA to successfully inhibit interactions with the virus [116]. Honda et al. grafted 4-guanidino-Neu5Ac2en analogs on poly-L-glutamic acid backbone to engineer multivalent polymeric inhibitors that target sialidase, another important surface glycoprotein on influenza virus essential for infective activity [117].

5.2. Polymeric drugs against HIV

Multiple approaches have been investigated in order to develop polymeric drugs to treat or prevent infections caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The best known product is SPL7013 (VivaGel®), a poly(lysine) dendrimer with broad antiviral activity against multiple HIV strains. SPL7013 is a G4 dendrimer with molecular weight 16 kDa that is substituted with 32 anionic naphthalene-3,6-disulfonate groups to block viral entry by interactions with positively-charged glycoprotein gp120 in the viral envelope [118–120]. Although the dendrimers exhibited promising anti-viral activity after vaginal administration in Phase I and II clinical trials [121–123], they ultimately failed to achieve their primary end point in Phase III. Currently, VivaGel® is still under clinical development for preventing recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. Meanwhile, condoms containing VivaGel® are already available on the market in selected countries, including Australia and Japan. Other types and generations of dendrimers presenting a number of different anionic ligands have been explored in HIV prevention and treatment [124–127]. In addition to interfering with the viral entry, some of the dendrimers were even shown to target later stages (reverse transcriptase/integrase) of the replication cycle [127]. In addition to dendrimers, negatively charged linear polymers have been also tested as blockers of HIV entry. Sulfonated polymers such as poly(vinyl sulfonate), poly(acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propanesulfonic acid), poly(anetholesulfonate), sulfated poly(vinyl alcohol), and sulfated poly(vinyl alcohol-co-acrylate) all produced effective anti-HIV activity by targeting gp120 (reviewed in [113]). Poly(naphthalene sulfate) (PRO2000) was shown to inhibit HIV-1 entry via binding with soluble CD4 [128]. HIV inhibition could also be achieved using polymers that contained carboxylate moieties such as copolymers of styrene and maleic acid [129]. Several of these polymers have entered clinical trials, but none of them succeeded clinically, mainly due to unsatisfactory efficacy [130].

In addition to anionic dendrimers, cationic dendrimers have also been successfully applied as antiviral agents. In particular, cationic dendrimers based on N-alkylated 4,4′-bipyridinium units (known as viologens) showed potent anti-HIV properties [131,132]. Structure-activity relationship study discovered that spherical dendrimers were more effective than comb-branched ones, and the selective HIV inhibitory activity was attributed to the interactions with positively charged residues of CXCR4, one of the two co-receptors for HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells. A follow-up study further explored the ability of the viologen dendrimers for dual functionality as gene delivery vectors and CXCR4 antagonists in vitro [133].

6. Polymeric drugs with antimicrobial activity

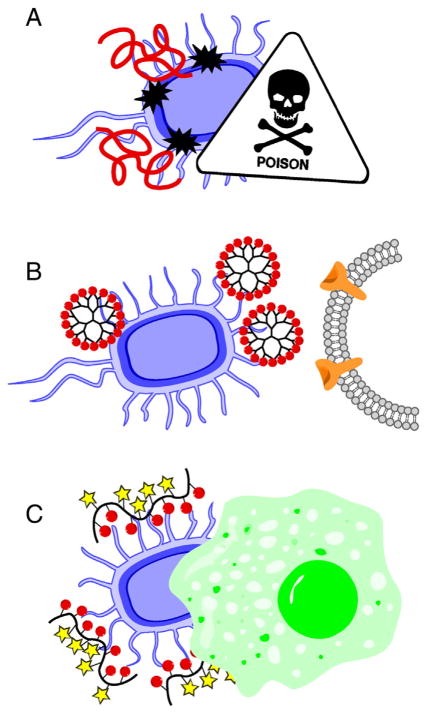

Resistance to multiple types of antimicrobial agents has emerged as a critical global healthcare problem [134]. New therapeutic strategies are urgently needed to overcome the challenges of treating infections caused by rapidly growing multi-drug resistant bacterial strains and polymeric drugs have been explored to target these pathogens. Most polymeric antimicrobials are designed to bind to the bacterial surface, either causing direct damage to the membrane, blocking interactions with host cells, or decorating the surface with biorecognizable moieties to opsonize the pathogen for phagocytosis (Scheme 7) [52].

Scheme 7.

Polymeric drugs exert antimicrobial properties by A) directly damaging bacterial membrane resulting in cell death; B) blocking interactions between the bacteria and the host cell; and C) decorating bacterial cell surface to be recognized for phagocytosis.

Ever since the discovery of innate antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), considerable efforts have been made in the development of polymeric mimics of AMPs [135]. These peptides assume α-helix folding arrangement and their antimicrobial activity is attributed to the segregation of cationic and hydrophobic moieties on the opposing sides of the helix. The segregation is critical for efficient insertion and disruption of bacterial membranes [135,136]. Synthetic polymers have been designed to mimic the naturally occurring AMPs using copolymerization of cationic and hydrophobic monomers to prepare amphiphilic random copolymers [137,138] (Scheme 3H). Alternatively, such polymers could be synthesized by using monomers carrying one cationic and one hydrophobic moiety in the same molecule [137,139] (Scheme 3I). Unlike natural AMPs, the selectivity of synthetic polymeric mimics towards pathogens over human cells remains a major challenge [140]. A series of poly(methylacrylate)s with various molecular weights and amphiphilicity was synthesized and it was found that polymers with higher lipophilicity and lower molecular weight showed better selectivity for bacterial membranes. The structure-activity study shed light on how cationic groups assist in the initial association and how hydrophobic groups form strong interactions with the lipids in the bacterial membrane [141, 142] (Scheme 3L). Additional examples of poly(methylacrylate)s [143–148], poly(norbornene)s [137,149,150], poly(β-amino acid)s [138, 151–158] (Scheme 3J) and poly(hexamethylene biguanide)s [159] with balanced charges and amphiphilicity confirmed potential of this approach to polymeric AMP mimics that selectively target certain bacteria, including multi-drug resistant strains. Some of the best performing polymers were able to achieve comparable therapeutic activity as conventional antimicrobial agents without significant toxicity concerns in vivo.

Known for their membrane-disrupting activity, cationic polymers also received significant attention as antimicrobial agents. In particular, cationic dendrimers exhibited the most promising activity, as their spherical shape together with the multiple positive charges displayed on the dendrimer surface facilitates strong interactions with peptidoglycans on the bacterial surface, leading to membrane damage [160,161]. Few cases of molecular weight- and architecture-dependent selective antimicrobial activity were reported even with a branched PEI [162,163]. Thoma et al. recently documented antimicrobial activity of a simple linear poly(aminoethyl methacrylate) both in vitro and in vivo against Staphylococcus aureus [164] (Scheme 3K).

In addition to cationic moieties, a number of other biorecognition motifs were applied to the design of antimicrobial polymers to improve interactions with available targets on the bacterial surfaces [161,165]. For example, dendrimers were modified with specific sugars to mimic surface of host cells to bind with lectins found in the bacterial membrane, thus serving as anti-adhesive agents [161,166]. Dendrimers with hydroxyl end groups could bind to O antigens on the bacterial membrane, while dendrimers with carboxylic acid groups acted as polyanions that could chelate divalent ions (e.g. Ca2+) in outer membrane of E. coli [167].

Another interesting approach to antimicrobial polymers is to use heterofunctional polymers to decorate the surface of bacteria to direct neutralizing antibodies to the pathogen to promote opsonization and elimination by macrophages. The Whitesides lab described application of such heterobifunctional polymer that presents vancomycin and introduces haptens to the surface of bacteria. The decoration of the bacteria surface allowed specific antibody recognition and boosted phagocytosis of multiple strains of Gram-positive bacteria [168].

Finally, the Alexander lab recently reported the use of bacterial redox systems to induce polymerization at cell surfaces and producing in situ-templated polymers that bind strongly to the pathogens. Such bacteria-instructed polymer synthesis could generate matching polymers for a variety of bacteria strains, representing a promising approach for designing highly selective antibacterial polymeric drugs [169].

7. Miscellaneous applications of polymeric drugs

7.1. Polymeric drugs to modulate hemostasis

Fibrin is a fibrous protein that is produced at the site of vascular injury to form a water-insoluble hydrogel as a scaffold for clot components. Transglutaminase XIIIa (FXIIIa) is a key regulator that stabilizes the clot by crosslinking through amide bonds to produce a tight fibrin network. Lai et al. have synthesized a polymer with pendent dioxolane groups capable of changing the clot structure by influencing the lateral aggregation of protofibrils. This resulted in a decrease in FXIIIa-mediated crosslinking and antithrombotic activity in vitro [170]. In contrast, the Pun lab recently reported a synthetic polymeric drug named PolySTAT that was designed to crosslink the fibrin matrix to modulate hemostasis after systemic administration [171]. PolySTAT mimicked the stabilizing effect of FXIIIa by incorporating fibrin-binding peptides to the side chain of linear water-soluble copolymers of 2-(hydroxyethyl) methacrylate (Scheme 3M). The multivalent approach of displaying 16 highly specific fibrin-binding peptides in single polymer chain allowed fast-acting, efficient and safe construction of crosslinked fibrin meshes. PolySTAT altered architecture of the fibrin network with enhanced density, stiffness and smaller pores when compared with FXIIIa. Systemic administration of PolySTAT showed enhanced hemostatic efficacy and survival in a rat model of trauma by reducing blood loss and preventing re-bleeding during fluid resuscitation. In addition, the polymeric drug also showed improved pharmacokinetic profile when compared with the peptide alone, providing prolonged blood circulation and hemostatic activity at the injury site without undesired side effects.

7.2. Anti-inflammatory polymeric drugs

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a common inflammatory disease of the central nervous system. Although the cause of MS is not fully understood, the pathology is associated with overproduction of inflammatory cytokines and upregulated T cell infiltration [172]. The development of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®), which was approved by the FDA in 1996, has marked a therapeutic breakthrough in MS [173–175]. Copaxone is a synthetic copolymer of glutamic acid, lysine, alanine, and tyrosine obtained by random ring-opening copolymerization (molecular weight ~ 5–9 kDa). The copolymer successfully reduces T-cell migration to central nervous system and controls the pathogenesis of MS by antigen-specific desensitization of auto-reactive T-cells [176]. This approach has inspired further exploration of similar amino acid copolymers to treat a number of autoimmune diseases [177–182].

The Haag lab has demonstrated anti-inflammatory effect of a multivalent dendritic polyglycerol sulfates (dPGS) targeting leukocyte trafficking [183]. The authors showed that dPGS function as efficient inhibitors of selectins, cell adhesion molecules that play a crucial role in initiating and regulating leukocyte migration. The dendritic architecture of dPGS could be optimized to present 61 surface sulfate groups to facilitate high-affinity multivalent binding with L- and P-selectin and to mimic natural carbohydrate ligands. As the selectin receptor typically localizes to patches on the surface of leukocytes, dPGS could simultaneously bind multiple copies of selectin, leading to receptor clustering and proteolytic shedding [1]. In addition, dPGS also inhibited activity of complement factors C3 and C5, resulting in further reduction of inflammation. Subcutaneous administration of dPGS significantly lowered leukocyte extravasation and edema formation in a mouse model of contact dermatitis.

Rheumatoid arthritis is another disease area with successful reports of beneficial effects of polymeric drugs. Hayder et al. developed anti-inflammatory polymeric drugs based on dendrimers modified with azabisphosphonate groups to treat rheumatoid arthritis [184]. The authors showed that the dendrimers could selectively activate the amplification of natural killer cells [185], direct monocytes towards anti-inflammatory activation, upregulate the level of anti-inflammatory cytokines, and exhibit anti-osteoclastic activity. Importantly, intravenous administration of the dendrimers resulted in a highly effective and long-term (up to 3 weeks) anti-inflammatory activity.

8. Conclusions and future perspective

Although viewed with skepticism in traditional drug discovery, polymeric drugs offer potential advantages as therapeutics that stem from their ability to readily combine benefits of small-molecule drug discovery process with advantageous properties related to their macro-molecular character typically found in protein drugs. Commercial viability and regulatory feasibility of polymeric drugs have already been confirmed in multiple therapeutic areas as documented by several polymeric drug products on the market. The number of marketed polymeric drug products compares favorably with other applications of polymers in drug delivery that receive significantly higher attention in the field, such as polymeric micelles, nanoparticles, and polymer-drug conjugates.

This review article provided an overview of the main trends in the development of polymeric drugs as applied to sequestrants, anticancer, antimicrobial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory agents. The identified trends point to further growth of polymeric drugs in therapeutic areas, which can be addressed with local delivery approaches and do not require systemic absorption and distribution. Such approaches include nonabsorbable oral sequestrants, topical antimicrobials and topical antivirals (Table 1). For polymeric drugs that require systemic distribution to achieve their therapeutic effect, parenteral routes of administration will continue to dominate the field until effective methods of enhancing oral bioavailability of macromolecules are developed. Dual use of polymeric drugs in combination treatments such as the application of pharmacologically active polycations in nucleic acid delivery is likely to remain active area of academic research but the regulatory complexities of developing combination treatments will make clinical translation challenging.

Table 1.

Selected examples of clinical trials of polymeric drugs registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as of September 2015.

| Drug candidate | Sponsor | Condition | Stage | Route of administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fostrap (chitosan-based) | Nestlé Health Science | Hyperphosphatemia in patients with chronic kidney disease | 0 | Oral/chewing gum |

| CLP-1001 (cross-linked polyelectrolyte) | Sorbent Therapeutics, United States | Hyperkalemia in heart failure | 2 | Oral |

| Velphoro® (starch-based)a | Vifor Pharma, Switzerland | Hyperphosphatemia in dialysis patients with chronic kidney disease | 3 | Oral/chewable tablet |

| VivaGel® (dendrimer) | Starpharma, Australia | Recurrent bacterial vaginosis | 3 | Vaginal/muco-adhesive gel |

| BL-7010 | BioLineRx, Switzerland | Celiac disease | 1/2 | Oral |

| Vepoloxamer (MST-188) (poloxamer188) | Mast Therapeutics, United States | Subjects with sickle cell disease experiencing vaso-occlusive crisis | 3 | Intravenous |

Approved by FDA in 2013.

We anticipate future growth and expansion of the field of polymeric drugs spurred mostly by the advances in methods of controlled polymerization that allow to prepare better defined polymers than in the past. The improved control over distribution of molecular weights, sequence and distribution of ligands, and molecular architecture are particularly significant developments. To take full advantage of the therapeutic potential of multifunctional polymeric drugs, new synthetic methods to prepare sequence-defined polymers will be needed to allow better control of the spatial localization of various functionalities present in the polymeric drugs [186]. Despite our general optimism, there are multiple challenges faced in further expansion and development of polymeric drugs as a therapeutic class. First, chemical heterogeneity of polymeric drugs, especially those relying on ligand multivalency and prepared by traditional conjugation approaches, presents substantial analytical challenge and complicates structure-activity relationship studies [187]. Second, many polymeric drugs are based on non-degradable polymers and their metabolism, elimination, and toxicology are not fully understood and appreciated. Third, the relative novelty of polymeric drugs makes their commercial development challenging in a current system set up for development of small molecule drugs and unfamiliar with the peculiarities and unique features of polymers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the NIH for the financial support (R01 EB015216, R21 EB020308, R21 EB019175). Support from the Changjiang Scholar Program for D.O. is also acknowledged.

References

- 1.Kiessling LL, Gestwicki JE, Strong LE. Synthetic multivalent ligands as probes of signal transduction. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2348–2368. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncan R, Vicent MJ. Polymer therapeutics-prospects for 21st century: the end of the beginning. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(1):60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeo Y, Kim BK. Drug carriers: not an innocent delivery man. AAPS J. 2015;17:1096–1104. doi: 10.1208/s12248-015-9789-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mammen M, Choi SK, Whitesides GM. Polyvalent interactions in biological systems: implications for design and use of multivalent ligands and inhibitors. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:2754–2794. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vorup-Jensen T. On the roles of polyvalent binding in immune recognition: perspectives in the nanoscience of immunology and the immune response to nanomedicines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1759–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fasting C, Schalley CA, Weber M, Seitz O, Hecht S, Koksch B, Dernedde J, Graf C, Knapp EW, Haag R. Multivalency as a chemical organization and action principle. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:10472–10498. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitov PI, Sadowska JM, Mulvey G, Armstrong GD, Ling H, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Bundle DR. Shiga-like toxins are neutralized by tailored multivalent carbohydrate ligands. Nature. 2000;403:669–672. doi: 10.1038/35001095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee AL, Eiler D, Roy BC, Jia X, Haldar MK, Mallik S, Srivastava D. Spacer-based selectivity in the binding of “two-prong” ligands to recombinant human carbonic anhydrase I. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2005;44(9):3211–3224. doi: 10.1021/bi047737b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mammen M, Dahmann G, Whitesides GM. Effective inhibitors of hemagglutina-tion by influenza virus synthesized from polymers having active ester groups. Insight into mechanism of inhibition. J Med Chem. 1995;38:4179–4190. doi: 10.1021/jm00021a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigal GB, Mammen M, Dahmann G, Whitesides GM. Polyacrylamides bearing pendant α-sialoside groups strongly inhibit agglutination of erythrocytes by influenza virus: the strong inhibition reflects enhanced binding through cooperative polyvalent interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3789–3800. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joshi A, Vance D, Rai P, Thiyagarajan A, Kane RS. The design of polyvalent therapeutics. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:7738–7747. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine PM, Carberry TP, Holub JM, Kirshenbaum K. Crafting precise multivalent architectures. Med Chem Commun. 2013;4:493–509. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan R. The dawning era of polymer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:347–360. doi: 10.1038/nrd1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslow D. Biologically active synthetic polymers. Pure Appl Chem. 1976;46:103–113. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ottenbrite R, Goodell E, Munson A. A comparative study of antitumour and toxicologic properties of related polyanions. Polymer. 1977;18:461–466. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seymour L. Review: synthetic polymers with intrinsic anticancer activity. J Bioact Compat Polym. 1991;6:178–216. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferruti P. Poly(amidoamine)s: past, present, and perspectives. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem. 2013;51:2319–2353. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu K, Liu J, Johnson RN, Yang J, Kopeček J. Drug-free macromolecular therapeutics: induction of apoptosis by coiled-coil-mediated cross-linking of antigens on the cell surface. Angew Chem. 2010;122:1493–1497. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu K, Yang J, Liu J, Kopeček J. Coiled-coil based drug-free macromolecular therapeutics: in vivo efficacy. J Control Release. 2012;157:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu TW, Yang J, Zhang R, Sima M, Kopeček J. Cell surface self-assembly of hybrid nanoconjugates via oligonucleotide hybridization induces apoptosis. ACS Nano. 2013;8:719–730. doi: 10.1021/nn4053827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu TW, Yang J, Kopeček J. Anti-CD20 multivalent HPMA copolymer-FAB′ conjugates for the direct induction of apoptosis. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7174–7181. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamanna G, Smulski CR, Chekkat N, Estieu-Gionnet K, Guichard G, Fournel S, Bianco A. Multimerization of an apoptogenic TRAIL-mimicking peptide by using adamantane-based dendrons. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:1762–1768. doi: 10.1002/chem.201202415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maynard HD, Okada SY, Grubbs RH. Inhibition of cell adhesion to fibronectin by oligopeptide-substituted polynorbornenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1275–1279. doi: 10.1021/ja003305m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng Z-H, Kopeček Ji. HPMA copolymer CXCR4 antagonist conjugates substantially inhibited the migration of prostate cancer cells. ACS Macro Lett. 2014;3:1240–1243. doi: 10.1021/mz5006537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Oupicky D. Effect of biodegradability on CXCR4 antagonism, transfection efficacy and antimetastatic activity of polymeric plerixafor. Biomaterials. 2014;35:5572–5579. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miles D, von Minckwitz G, Seidman AD. Combination versus sequential single-agent therapy in metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2002;7:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alakhova DY, Kabanov AV. Pluronics and MDR reversal: an update. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:2566–2578. doi: 10.1021/mp500298q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Pluronic block copolymers: evolution of drug delivery concept from inert nanocarriers to biological response modifiers. J Control Release. 2008;130:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Batrakova EV, Li S, Brynskikh AM, Sharma AK, Li Y, Boska M, Gong N, Mosley RL, Alakhov VY, Gendelman HE, Kabanov AV. Effects of pluronic and doxorubicin on drug uptake, cellular metabolism, apoptosis and tumor inhibition in animal models of MDR cancers. J Control Release. 2010;143:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu J, Zhao W, Liu H, Marquez R, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Li J, Xie W, Venkataramanan R, Xu L, Li S. An improved D-α-tocopherol-based nanocarrier for targeted delivery of doxorubicin with reversal of multidrug resistance. J Control Release. 2014;196:272–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo Y, Luo J, Tan S, Otieno BO, Zhang Z. The applications of vitamin E TPGS in drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;49:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dintaman JM, Silverman JA. Inhibition of P-glycoprotein by D-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS) Pharm Res. 1999;16:1550–1556. doi: 10.1023/a:1015000503629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Huang L, Liu F. Paclitaxel nanocrystals for overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:863–869. doi: 10.1021/mp100012s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu H, Chen H, Zeng X, Wang Z, Zhang X, Wu Y, Gao Y, Zhang J, Liu K, Liu R. Co-delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs with vitamin E TPGS by porous PLGA nano-particles for enhanced chemotherapy against multi-drug resistance. Biomaterials. 2014;35:2391–2400. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saxena V, Hussain MD. Poloxamer 407/TPGS mixed micelles for delivery of gambogic acid to breast and multidrug-resistant cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:713. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S28745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen J, Yin Q, Chen L, Zhang Z, Li Y. Co-delivery of paclitaxel and survivin shRNA by pluronic P85-PEI/TPGS complex nanoparticles to overcome drug resistance in lung cancer. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8613–8624. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma Y, Liu D, Wang D, Wang Y, Fu Q, Fallon JK, Yang X, He Z, Liu F. Combinational delivery of hydrophobic and hydrophilic anticancer drugs in single nano-emulsions to treat MDR in cancer. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:2623–2630. doi: 10.1021/mp400778r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duhem N, Danhier F, Préat V. Vitamin E-based nanomedicines for anti-cancer drug delivery. J Control Release. 2014;182:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang X, Liang Y, Feng X, Zhang R, Jin X, Sun L. Co-delivery of docetaxel and poloxamer 235 by PLGA-TPGS nanoparticles for breast cancer treatment. Mater Sci Eng C. 2015;49:348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo Y, Chu M, Tan S, Zhao S, Liu H, Otieno BO, Yang X, Xu C, Zhang Z. Chitosang-TPGS nanoparticles for anticancer drug delivery and overcoming multidrug resistance. Mol Pharm. 2013;11:59–70. doi: 10.1021/mp400514t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gill KK, Kaddoumi A, Nazzal S. Mixed micelles of PEG 2000-DSPE and vitamin-E TPGS for concurrent delivery of paclitaxel and parthenolide: enhanced chemo-senstization and antitumor efficacy against non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2012;46:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu J, Zhao W, Huang Y, Liu H, Marquez R, Gibbs RB, Li J, Venkataramanan R, Xu L, Li S, Li S. Targeted delivery of doxorubicin by folic acid-decorated dual functional nanocarrier. Mol Pharm. 2014;111:4164–4178. doi: 10.1021/mp500389v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu J, Huang Y, Zhao W, Marquez RT, Meng X, Li J, Gao X, Venkataramanan R, Wang Z, Li S. PEG-derivatized embelin as a nanomicellar carrier for delivery of paclitaxel to breast and prostate cancers. Biomaterials. 2013;34:1591–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dufes C, Keith WN, Bilsland A, Proutski I, Uchegbu IF, Schatzlein AG. Synthetic anticancer gene medicine exploits intrinsic antitumor activity of cationic vector to cure established tumors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8079–8084. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Hazeldine ST, Li J, Oupicky D. Development of functional poly(amido amine) CXCR4 antagonists with the ability to mobilize leukocytes and deliver nucleic acids. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2015;4:729–738. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201400608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J, Zhu Y, Hazeldine ST, Li C, Oupicky D. Dual-function CXCR4 antagonist polyplexes to deliver gene therapy and inhibit cancer cell invasion. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:8740–8743. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Li J, Oupicky D. Polymeric plerixafor: effect of PEGylation on CXCR4 antagonism, cancer cell invasion, and DNA transfection. Pharm Res. 2014;31:3538–3548. doi: 10.1007/s11095-014-1440-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Li J, Chen Y, Oupicky D. Balancing polymer hydrophobicity for ligand presentation and siRNA delivery in dual function CXCR4 inhibiting polyplexes. Biomater Sci. 2015;3:1114–1123. doi: 10.1039/C5BM00003C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dhal PK, Holmes-Farley SR, Huval CC, Jozefiak TH. Polymer Therapeutics I. Springer; 2006. pp. 9–58. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dhal PK, Huval CC, Holmes-Farley SR. Biologically active polymeric sequestrants: design, synthesis, and therapeutic applications. Pure Appl Chem. 2007;79:1521–1530. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu S, Maheshwari R, Kiick KL. Polymer-based therapeutics. Macromolecules. 2009;42:3–13. doi: 10.1021/ma801782q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bertrand N, Colin P, Ranger M, Leblond J. Supramolecular Systems in Biomedical Fields. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge UK: 2013. pp. 483–517. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneider HJ. Binding mechanisms in supramolecular complexes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:3924–3977. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bertrand N, Gauthier MA, Bouvet C, Moreau P, Petitjean A, Leroux JC, Leblond J. New pharmaceutical applications for macromolecular binders. J Control Release. 2011;155:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watson M, Abbott KC, Yuan CM. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t: potassium binding resins in hyperkalemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1723–1726. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03700410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalaitzidis RG, Elisaf MS. Hyperphosphatemia and phosphate binders: effectiveness and safety. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;30:109–112. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.841667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waheed AA, Pedraza F, Lenz O, Isakova T. Phosphate control in end-stage renal disease: barriers and opportunities. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:2961–2968. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tonelli M, Pannu N, Manns B. Oral phosphate binders in patients with kidney failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1312–1324. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0912522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bellasi A, Kooienga L, Block GA. Phosphate binders: new products and challenges. Hemodial Int. 2006;10:225–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2006.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Amin N. The impact of improved phosphorus control: use of sevelamer hydrochloride in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:340–345. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosenbaum D, Holmes-Farley S, Mandeville W, Pitruzzello M, Goldberg D. Effect of RenaGel, a non-absorbable, cross-linked, polymeric phosphate binder, on urinary phosphorus excretion in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:961–964. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.5.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suki WN, Zabaneh R, Cangiano JL, Reed J, Fischer D, Garrett L, Ling BN, Chasan-Taber S, Dillon MA, Blair AT. Effects of sevelamer and calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1130–1137. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Locatelli F, Spasovski G, Dimkovic N, Wanner C, Dellanna F, Pontoriero G. The effects of colestilan versus placebo and sevelamer in patients with CKD 5D and hyperphosphataemia: a 1-year prospective randomized study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;29:1061–1073. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inoue A, Minakami S, Kanno T, Suyama K. Highly selective and low-swelling phosphate-binding polymer for hyperphosphatemia therapy. Chem Lett. 2012;41:932–933. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakaki J, Yamaguchi S, Torii Y, Inoue A, Minakami S, Kanno T, Murakami M, Tsuzuki M, Mochizuki H, Suyama K. Effect of fatty acids on the phosphate binding of TRK-390, a novel, highly selective phosphate-binding polymer. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;714:312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wong JRW, Chen YW, Gaffin R, Hall A, Wong JT, Xiong J, Wessale JL. VS-501: a novel, nonabsorbed, calcium- and aluminum-free, highly effective phosphate binder derived from natural plant polymer. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2014;2:e00042. doi: 10.1002/prp2.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Savica V, Calò LA, Monardo P, Davis PA, Granata A, Santoro D, Savica R, Musolino R, Comelli MC, Bellinghieri G. Salivary phosphate-binding chewing gum reduces hyperphosphatemia in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:639–644. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hallaway PE, Eaton JW, Panter SS, Hedlund BE. Modulation of deferoxamine toxicity and clearance by covalent attachment to biocompatible polymers. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:10108–10112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rossi NAA, Mustafa I, Jackson JK, Burt HM, Horte SA, Scott MD, Kizhakkedathu JN. In vitro chelating, cytotoxicity, and blood compatibility of degradable poly (ethylene glycol)-based macromolecular iron chelators. Biomaterials. 2009;30:638–648. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Imran ul-haq M, Hamilton JL, Lai BFL, Shenoi RA, Horte S, Constantinescu I, Leitch HA, Kizhakkedathu JN. Design of Long Circulating Nontoxic Dendritic Polymers for the Removal of Iron in Vivo. ACS Nano. 2013;7:10704–10716. doi: 10.1021/nn4035074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou T, Neubert H, Liu DY, Liu ZD, Ma YM, Kong XL, Luo W, Hider RC. Iron binding dendrimers: a novel approach for the treatment of haemochromatosis. J Med Chem. 2006;49:4171–4182. doi: 10.1021/jm0600949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhou T, Winkelmann G, Dai ZY, Hider RC. Design of clinically useful macromolecular iron chelators. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;63:893–903. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou T, Kong XL, Liu ZD, Liu DY, Hider RC. Synthesis and iron (III)-chelating properties of novel 3-hydroxypyridin-4-one hexadentate ligand-containing copolymers. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1372–1380. doi: 10.1021/bm701122u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Polomoscanik SC, Cannon CP, Neenan TX, Holmes-Farley SR, Mandeville WH, Dhal PK. Hydroxamic acid-containing hydrogels for nonabsorbed iron chelation therapy: synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:2946–2953. doi: 10.1021/bm050036p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lim J, Venditto VJ, Simanek EE. Synthesis and characterization of a triazine dendrimer that sequesters iron (III) using 12 desferrioxamine B groups. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:5749–5753. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Siao F, Lu J, Wang J, Inbaraj BS, Chen B. In vitro binding of heavy metals by an edible biopolymer poly (γ-glutamic acid) J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:777–784. doi: 10.1021/jf803006r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rajan YC, Inbaraj BS, Chen BH. In vitro adsorption of aluminum by an edible biopolymer poly (γ-glutamic acid) J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:4803–4811. doi: 10.1021/jf5011484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang H, Wang Y, Zhao M, Wu J, Zhang X, Gui L, Zheng M, Li L, Liu J, Peng S. synthesis and in vivo lead detoxification evaluation of poly-α,β-dl-aspartyl-l-methionine. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:471–477. doi: 10.1021/tx2005037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haratake M, Hatanaka E, Fuchigami T, Akashi M, Nakayama M. A Strontium-90 sequestrant for first-aid treatment of radiation emergency. Chem Pharm Bull. 2012;60:1258–1263. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c12-00430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mendonça PV, Serra AC, Silva CL, Simões S, Coelho JFJ. Polymeric bile acid sequestrants—synthesis using conventional methods and new approaches based on “controlled”/living radical polymerization. Prog Polym Sci. 2013;38:445–461. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Insull W., Jr Clinical utility of bile acid sequestrants in the treatment of dyslipidemia: a scientific review. South Med J. 2006;99:257–273. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000208120.73327.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dhal PK, Polomoscanik SC, Avila LZ, Holmes-Farley SR, Miller RJ. Functional polymers as therapeutic agents: concept to market place. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:1121–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mendonça PV, Serra AC, Silva CL, Simões S, Coelho JF. Polymeric bile acid sequestrants—synthesis using conventional methods and new approaches based on “controlled”/living radical polymerization. Prog Polym Sci. 2013;38:445–461. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rusconi CP, Scardino E, Layzer J, Pitoc GA, Ortel TL, Monroe D, Sullenger BA. RNA aptamers as reversible antagonists of coagulation factor IXa. Nature. 2002;419:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rusconi CP, Roberts JD, Pitoc GA, Nimjee SM, White RR, Quick G, Scardino E, Fay WP, Sullenger BA. Antidote-mediated control of an anticoagulant aptamer in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1423–1428. doi: 10.1038/nbt1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dyke CK, Steinhubl SR, Kleiman NS, Cannon RO, Aberle LG, Lin M, Myles SK, Melloni C, Harrington RA, Alexander JH. First-in-human experience of an antidote-controlled anticoagulant using RNA aptamer technology a phase 1a pharmacodynamic evaluation of a drug-antidote pair for the controlled regulation of factor IXa activity. Circulation. 2006;114:2490–2497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oney S, Lam RT, Bompiani KM, Blake CM, Quick G, Heidel JD, Liu JYC, Mack BC, Davis ME, Leong KW. Development of universal antidotes to control aptamer activity. Nat Med. 2009;15:1224–1228. doi: 10.1038/nm.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee J, Sohn JW, Zhang Y, Leong KW, Pisetsky D, Sullenger BA. Nucleic acid-binding polymers as anti-inflammatory agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:14055–14060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105777108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stearns NA, Lee J, Leong KW, Sullenger BA, Pisetsky DS. The inhibition of anti-DNA binding to DNA by nucleic acid binding polymers. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pisetsky DS, Lee J, Leong KW, Sullenger BA. Nucleic acid-binding polymers as anti-inflammatory agents: reducing the danger of nuclear attack. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8:1–3. doi: 10.1586/eci.11.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Holl EK, Bond JE, Selim MA, Ehanire T, Sullenger B, Levinson H. The nucleic acid scavenger polyamidoamine third-generation dendrimer inhibits fibroblast activation and granulation tissue contraction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:420e–433e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jain S, Pitoc GA, Holl EK, Zhang Y, Borst L, Leong KW, Lee J, Sullenger BA. Nucleic acid scavengers inhibit thrombosis without increasing bleeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:12938–12943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204928109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Branson TR, Turnbull WB. Bacterial toxin inhibitors based on multivalent scaffolds. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:4613–4622. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35430f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mulvey GL, Marcato P, Kitov PI, Sadowska J, Bundle DR, Armstrong GD. Assessment in mice of the therapeutic potential of tailored, multivalent Shiga toxin carbohydrate ligands. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:640–649. doi: 10.1086/373996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kitov PI, Paszkiewicz E, Sadowska JM, Deng Z, Ahmed M, Narain R, Griener TP, Mulvey GL, Armstrong GD, Bundle DR. Impact of the nature and size of the polymeric backbone on the ability of heterobifunctional ligands to mediate Shiga toxin and serum amyloid P component ternary complex formation. Toxins. 2011;3:1065–1088. doi: 10.3390/toxins3091065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kitov PI, Mulvey GL, Griener TP, Lipinski T, Solomon D, Paszkiewicz E, Jacobson JM, Sadowska JM, Suzuki M, Yamamura K-i. In vivo supramolecular templating enhances the activity of multivalent ligands: a potential therapeutic against the Escherichia coli O157 AB5 toxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:16837–16842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804919105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mourez M, Kane RS, Mogridge J, Metallo S, Deschatelets P, Sellman BR, Whitesides GM, Collier RJ. Designing a polyvalent inhibitor of anthrax toxin. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:958–961. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gujraty KV, Joshi A, Saraph A, Poon V, Mogridge J, Kane RS. Synthesis of poly-valent inhibitors of controlled molecular weight: structure-activity relationship for inhibitors of anthrax toxin. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2082–2085. doi: 10.1021/bm060210p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Joshi A, Saraph A, Poon V, Mogridge J, Kane RS. Synthesis of potent inhibitors of anthrax toxin based on poly-L-glutamic acid. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:1265–1269. doi: 10.1021/bc060042y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gujraty KV, Yanjarappa MJ, Saraph A, Joshi A, Mogridge J, Kane RS. Synthesis of homopolymers and copolymers containing an active ester of acrylic acid by RAFT: scaffolds for controlling polyvalent ligand display. J Polym Sci Part A: Polym Chem. 2008;46:7249–7257. doi: 10.1002/pola.23031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hoshino Y, Koide H, Furuya K, Haberaecker WW, Lee SH, Kodama T, Kanazawa H, Oku N, Shea KJ. The rational design of a synthetic polymer nanoparticle that neutralizes a toxic peptide in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:33–38. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112828109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hoshino Y, Koide H, Urakami T, Kanazawa H, Kodama T, Oku N, Shea KJ. Recognition, neutralization, and clearance of target peptides in the bloodstream of living mice by molecularly imprinted polymer nanoparticles: a plastic antibody. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6644–6645. doi: 10.1021/ja102148f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kiessling LL, Gestwicki JE, Strong LE. Synthetic multivalent ligands in the exploration of cell-surface interactions. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2000;4:696–703. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Braunlin W, Xu Q, Hook P, Fitzpatrick R, Klinger JD, Burrier R, Kurtz CB. Toxin binding of tolevamer, a polyanionic drug that protects against antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Biophys J. 2004;87:534–539. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.041277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Weiss K. Toxin-binding treatment for Clostridium difficile: a review including reports of studies with tolevamer. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Duncan R. Polymer therapeutics: top 10 selling pharmaceuticals—what next? J Control Release. 2014;190:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]