Abstract

One of the greatest challenges in the field of medicine is obtaining controlled distribution of systemically administered therapeutic agents within the body. Indeed, biological barriers such as physical compartmentalization, pressure gradients, and excretion pathways adversely affect localized delivery of drugs to pathological tissue. The diverse nature of these barriers requires the use of multifunctional drug delivery vehicles that can overcome a wide range of sequential obstacles. In this review, we explore the role of multifunctionality in nanomedicine by primarily focusing on multistage vectors (MSVs). The MSV is an example of a promising therapeutic platform that incorporates several components, including a microparticle, nanoparticles, and small molecules. In particular, these components are activated in a sequential manner in order to successively address transport barriers.

Keywords: biological barriers, cancer therapy, geometrical targeting, porous silicon, transport oncophysics

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The practice of medicine is largely based on the ‘therapeutic window’ concept, which describes a range of drug concentrations that are effective against a disease without causing unacceptable adverse side effects. This concept sheds light upon an inherent limitation of therapeutic regimes: an inability to precisely control which organs, tissues, cells, and cellular organelles are exposed to systemic drugs. In this sense, treatment of disease is fundamentally a problem of drug distribution and containment, i.e. if the therapeutic agent could be exclusively directed and confined to pathological tissue, the upper dose threshold would be irrelevant. Notably, difficulties in drug transport arise due to biological barriers, which must be overcome for a therapeutic agent to reach an intended location (Fig. 1) [1-5]. For instance, in the circulatory system, drugs are exposed to mechanical/enzymatic degradation, uptake by the immune system, and renal/biliary clearance. Furthermore, once a drug has successfully crossed the vascular endothelial barrier, a process that can be further hampered by adverse oncotic pressure states, other challenges such as interstitial pressure and a network of extracellular matrix molecules are encountered. Finally, upon establishing contact with cells, drugs are subjected to additional transport obstacles, including the cell membrane, cellular organelles, and efflux pumps. Within the realm of oncology, this notion has sparked the emergence of a new field, termed transport oncophysics, which is driven by the perspective that cancer is a proliferative disease of mass transport dysregulation, mainly expressed through pathological evolution of biological barriers [1, 6]. A fundamental tenet of transport oncophysics is to selectively exploit cancer-related transport pathologies by suitable design of therapeutic agents.

Figure 1.

Select biological barriers present at various stages following intravenous injection of a drug delivery vehicle. a, In the circulatory system, the drug delivery vehicle (gray) is exposed to enzymatic degradation and uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system, which mainly consists of blood monocytes and resident macrophages in the liver and spleen. The drug delivery vehicle must then cross the endothelial barrier in order to enter tissues of the body. b, In the tissue interstitium, the drug delivery vehicle is subject to interstitial pressure and a dense network of extracellular matrix molecules. c, Upon establishing contact with cells, additional barriers such as the cell membrane, lysosomes, and efflux pumps are encountered.

Fortunately, the use of drug delivery vehicles that are more equipped at overcoming biological barriers can improve the biodistribution of drugs. The diverse nature of these barriers necessitates the development of delivery vehicles that incorporate several mechanisms for bypassing transport obstacles. In this regard, it is questionable that a single material or component would be able to execute multiple strategies for obtaining a desirable biodistribution. Rather, a platform that integrates various components could have greater potential to perform several functions. However, conventional therapeutics are rarely multicomponent structures due to the complexity involved in constructing such systems on a smaller scale that would be compatible with the requirements of human biology. In fact, it is only through nanotechnology that multifunctionality can be fully incorporated into medicine. In the context of transport oncophysics, this entails coupling of drugs to various transport-enhancing components. Notably, medicine is one of the few disciplines in which nanotechnology can result in an adaptation to increasingly larger structures, since conventional drug molecules are in the angstrom size range. On the contrary, within the computer and solar power industries, the revolutionary effects of nanotechnology stem from a reduction in the size of single entities in a larger system. Traditionally, these industries were not restricted by size constraints, enabling them to fully explore multifunctionality prior to the implementation of nanotechnology, providing a possible explanation as to why advances in medicine are in some regards lagging behind other disciplines.

In reference to drug delivery, one approach to multifunctionality is the use of multistage platforms. Since specific biological barriers are encountered at different phases throughout the drug delivery process, it is reasonable that delivery vehicles should activate distinct components at different stages. Indeed, several multistage drug delivery platforms have been designed, including the nanocell, the amplifying system, and the multistage vector (MSV). The nanocell is a sequentially activated platform consisting of a pegylated lipid nanoparticle encapsulating a polymeric nanoparticle [7]. In the first drug delivery stage, the lipid nanoparticle releases an antiangiogenic agent that blocks the formation of tumor blood vessels, subsequently initiating the second phase, wherein chemotherapeutic agents are released into the tumor microenvironment. The amplifying system, in turn, makes use of the coagulation cascade to promote tumor accumulation [8]. The first step in the drug delivery process involves induction of coagulation in tumor tissue through injection of tissue factor protein or photothermally activated gold nanoparticles, while the second step comprises the administration of doxorubicin liposomes that bind to coagulated blood.

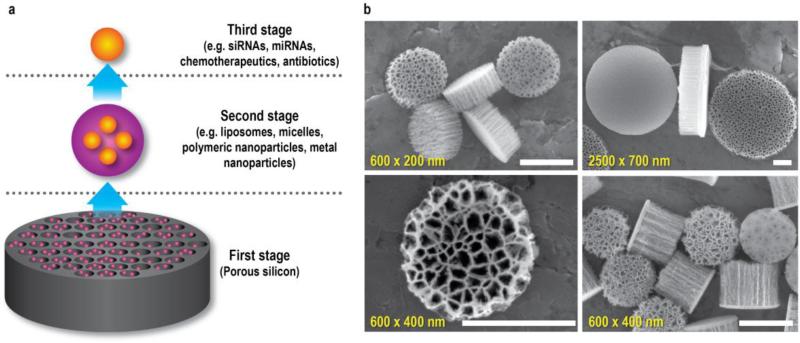

The third example of a multistage platform is the MSV system, which encompasses several components, each designed to address a different set of biological barriers (Fig. 2a). The first stage component consists of a porous silicon microparticle that can be loaded with various nanoparticles. The silicon particle preferentially binds to diseased vasculature and protects the cargo from degradation. As the silicon material gradually degrades, second stage nanoparticles are released into pathological tissue. These nanoparticles further protect the therapeutic payload from degradation and promote intracellular uptake in cancer cells. Finally, the third stage therapeutic agent is typically released upon internalization of nanoparticles into cells. The novelty of the MSV lies in the multistage setup designed to sequentially overcome biological barriers. The concurrent utilization of several targeting strategies and the implementation of personalized medicine further contribute to the novelty of this system. In essence, the MSV is not comparable to other nanodelivery systems, as it operates on a different level, i.e. it is a delivery system for nanoparticles. While there are several instances in which liposomes, micelles, dendrimers, or polymeric nanoparticles are sufficient to deliver drugs to diseased tissue, the MSV is designed to treat conditions characterized by complex transport obstacles. This review will examine ways in which multifunctionality can be incorporated into medicine by specifically discussing the MSV platform in its original embodiment. In particular, the fabrication, characterization, safety, targeting, and payload capacity of the MSV will be discussed in detail.

Figure 2.

The multistage vector (MSV). a, The MSV consists of three components: a porous silicon microparticle, nanoparticles, and therapeutic agents. These components are activated in a sequential manner. The first stage silicon particle is enriched in diseased vasculature, where it gradually degrades. This degradation triggers the release of second stage nanoparticles into pathological tissue. The nanoparticles are then internalized into cells, whereupon the third stage therapeutic agent is released. b, Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of unloaded MSVs with various dimensions and pore sizes. Pore size, 30 nm (upper left and lower right panel); 80 nm (upper right panel); 100 nm (lower left panel). Scale bars, 500 nm. Partially reproduced from [9] with permission. miRNA, micro RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

2. Fabrication process and particle characteristics

MSV particles are produced at our institute according to the United States Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) good manufacturing practices (cGMP) using protocols that are easily scalable for mass production. These protocols involve exposing 100 mm heavily doped silicon wafers (p++ type) with resistivity of 0.005 ohm cm to electrochemical etching in aqueous hydrofluoric acid to create pores in the silicon material [9]. A layer of silicon oxide is then deposited on the film using low-pressure chemical vapor deposition. This step is followed by photolithography and reactive-ion etching in fluorocarbon plasma to form geometrical patterns outlining particle dimensions. The top layer of the MSV is designed to be less porous in order to maintain particle integrity, since high porosity can result in particle instability (Fig. 2b) [9]. The particles are then subjected to sonication in isopropanol to release them from the silicon substrate. For large-scale production, a multilayer stack procedure can be employed, in which silicon pillars are formed through deep anisotropic etching [9, 10]. Silicon nitride can then be deposited on the entire substrate and the silicon on top of the pillar subjected to reactive-ion etching in fluorocarbon plasma. Subsequently, multilayer stacks of particles can be formed through current-controlled electrochemical etching of the pillars. This method results in a more than tenfold increase in production yield.

The characteristics of the MSV particles can be adjusted by modulating the electrochemical etching and photolitography process, as illustrated in a study where discoidal MSVs with various diameters (500–2600 nm), heights (200–700 nm), pore sizes (5–150 nm), and porosity (40-90%) were fabricated [9]. Consequently, the ability to produce MSVs with distinct dimensions and porous structures (Fig. 2b) enables generation of particles with different performance attributes, spanning nanoparticle loading capacity, drug release profile, degradation kinetics, and biodistribution. The identification of correlations between physical parameters and biological performance permits selection of the most suitable particle characteristics for a given application. As an example, increased pore size was shown to enhance loading capacity and accelerate particle degradation [11, 12]. Moreover, porous silicon-based drug delivery vehicles are especially well-suited for cancer therapy, as degradation and subsequent drug release are enhanced in response to reactive oxygen species [13], which are present in high levels in tumor tissue [14].

The MSVs can be further optimized through surface modifications, generally involving oxidation in a 30% hydrogen peroxide solution at 95 °C for 2 h followed by functionalization with molecules that can affect particle charge, degradation kinetics, and biological performance [15]. For example, 3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) modification, which endows particles with a positive charge, can be achieved by incubating particles in 2% (v/v) APTES in isopropanol for 48 h at 64 °C [15]. It was found that oxidized MSVs accumulate in similar amounts in the liver and spleen, while the deposition of APTES-modified MSVs in the spleen is twofold higher than in the liver (normalized to organ weight) [16]. Moreover, MSVs can be pegylated by incubating APTES-modified particles in methoxy polyethylene glycol (mPEG)-succinimidyl carboxy methyl ester (SCM) in acetonitrile for 1.5 h [17]. Studies have demonstrated that APTES-MSVs and PEG-MSVs degrade in 8-16 h and 24-48 h, respectively, indicating that pegylation can delay particle degradation [17, 18]. Typically, standard EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) chemistry can be used to form stable chemical linkages between the amino groups of APTES-modified MSVs and functional moieties, such as arginine [15, 19] and DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid) [20]. Additionally, various ligands can be conjugated to the surface of the MSV to increase binding to biological targets, a strategy that will be discussed in further detail in subsequent sections. Once such modifications are completed, second stage therapeutic nanoparticles can be loaded inside the silicon pores through brief sonication [21-26]. Alternatively, the pores of the silicon particle can be functionalized with polymers and nucleic acids that spontaneously assemble into nanoparticles upon degradation of the silicon material [15, 19, 27].

In accordance with cGMP regulations, protocols have been established to perform quality control and quality assurance of the MSVs. Quality control of particle fabrication includes microscopic analysis throughout the fabrication process. Moreover, during chemical surface modification steps, the following quality control measurements are employed: i) sterility assessment to ensure the absence of bacterial, yeast, and mold contaminations, ii) endotoxin quantification using the limulus amebocyte lysate assay, iii) loading capacity analysis, iv) evaluation of release profile, and v) microscopic analysis of particle morphology. Although large-scale production in compliance with cGMP regulations can be achieved, it is worth mentioning that the pharmaceutical industry has little familiarity with the use of silicon as a therapeutic material. In this regard, one of the disadvantages associated with the MSV is a lack of collaborative efforts between the pharmaceutical industry and research groups that employ silicon-based drug delivery systems. In particular, pharmaceutical companies lack knowledge about the manufacturing of silicon particles, which seems to be the main reason for disengagement in silicon-based therapeutics. Another potential drawback for the clinical translation of the MSV is the regulatory process, which could be complicated by the fact that the FDA has not yet established clear guidelines regarding the approval of multicomponent therapeutics.

3. Safety

The use of materials for medical applications requires safety assessment tests to insure biocompatibility. Since the major component of the MSV is the first stage silicon vector, the safety of this material will be discussed. Although silicon has mainly been used in the semiconductor industry, it displays several useful properties for biomedical applications, including biodegradability and tunable characteristics [28, 29]. Moreover, silicon is a naturally occurring mineral that can be found in deposits throughout the body, especially in connective tissue, where it aids in maintaining tissue homeostasis [30]. In fact, the average daily intake of silicon in the United States is 25-30 mg, mainly originating from food and beverage products such as bananas, green beans, and beer [31]. In the case of the MSV, the predominant degradation product is orthosilicic acid [11], which is the major form of silicon naturally present in humans and animals [32]. Notably, orthosilicic acid has been suggested as a potential therapeutic agent to treat high blood pressure, osteoporosis, and Alzheimer's disease [32].

It is important to make distinctions between silicon and silica (silicon dioxide) particles. The former typically exhibits a more favorable safety profile, although both particles display high biocompatibility [33]. Furthermore, silicon and silica should not be confused with silicone, a polymer made of siloxane units, which has also been used as a material for drug delivery systems [34, 35]. In regards to safety, particle size is a determining factor, as illustrated in a study in which intravenously injected silica particles in the 10 μm size range displayed acute toxicity, while 2 μm and 5 μm particles were non-toxic [36]. The observed toxic effects of the larger particles appeared to be due to particle-induced obstructions in pulmonary blood flow. Furthermore, intravenous injection of silicon/silica particles is generally well tolerated, while respiratory exposure to crystalline silica can induce inflammatory responses in the lungs [37, 38], implying that the route of administration is a critical determinant of safety.

In regards to the MSV, multiple animal studies have demonstrated a lack of acute toxicity, subacute toxicity, and immunotoxicity following intravenous administration [19, 21, 25, 27, 39]. In particular, weekly injections of 0.5 billion particles/mouse (corresponding to a silicon dose of approximately 6 mg/kg/week) for four weeks did not cause any changes in renal and hepatic biomarkers, organ histology, and the levels of more than 20 plasma cytokines [19]. Notably, the dose administered in this safety study was five times higher than that used to achieve therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, proteomic analysis of the MSV surface following incubation in plasma revealed that particle charge had a substantial impact on protein binding [16]. Specifically, MSVs that were positively charged exhibited a 25-fold increase in the levels of bound Ig light chain variable region, fibrinogen, and complement competent 1 in comparison to anionic particles. Despite the attachment of opsonins to the particle surface, extensive animal studies have demonstrated that MSVs do not cause immune reactions. In addition to analysis of immunological markers in the blood [19, 21, 25, 39], white blood cell counts [19, 25, 27] and examination of leukocyte organ infiltration did not indicate any signs of immunotoxicity [19, 25, 27, 39]. Besides displaying a favorable safety profile, the MSV can improve the tolerability of encapsulated nanoparticles. For instance, MSV-based delivery of polyethylenimine (PEI) nanoparticles was able to completely eliminate PEI-induced toxicity in vivo [19]. The MSV safety studies are supported by additional in vivo studies investigating the biocompatibility of other types of silicon particles [40-42]. In particular, non-human primates given a high intravenous dose (200 mg/kg) of Pluronic-encapsulated silicon quantum dots did not display any signs of toxicity during the three-month period in which they were monitored [40]. Interestingly, the same study uncovered changes in liver morphology in mice, indicating that different animal models respond in distinct ways to silicon quantum dots. Nonetheless, the quantum dots contained several other materials in addition to silicon crystals, making it uncertain whether it was the silicon component that caused such histological abnormalities.

The safety of second stage vectors, such as liposomes, micelles, and polymeric nanoparticles will not be discussed here, since such topics have been extensively reviewed in the literature and several lipid-based and polymer-based nanotherapeutics have received clinical approval [43, 44]. Nevertheless, it is important to confirm the safety of these nanoparticles in the context of the MSV. Indeed, preclinical studies show no evidence of adverse effects arising from crosstalk between the first stage silicon vector and second stage nanoparticles [19, 21, 25, 39].

4. Geometrical, molecular, and biomimetic targeting strategies

Local delivery of therapeutic agents is usually challenging due to an unfavorable location and/or scattered distribution of pathological tissue. For instance, in the case of cancer, 90% of deaths are caused by metastatic lesions [45], which are impossible to individually target through local interventions. Consequently, a systemic treatment approach is required, which relies on the circulatory system for transportation. However, the ability of the circulatory system to reach any tissue within the body is also a limitation of targeted therapy, since the entire organism becomes exposed to therapeutic agents. In the late 19th century, Paul Enrich, the father of chemotherapy, envisioned a future in which ‘magic bullets’ would be used to selectively deliver drugs to diseased tissue [46]. Indeed, embedded within the ‘magic bullet’ concept is the idea of a missile-like vehicle actively seeking out a pre-programmed destination. More than a century later, modern medicine has yet to realize this vision. For example, in the case of nanoparticles, a mere 5% of the injected dose typically reaches tumor tissue [47], while this value is in the range of 0.001%-0.01% for intravenously injected antibodies [48]. Although studies have found that tumor accumulation of chemotherapeutic agents can improve 16-fold [49] and 100-fold [50] through the use of nanoparticles, the bulk of the injected dose is nonetheless deposited in healthy tissue. Ultimately, localized delivery is dependent on both the successful penetration of biological barriers and the accurate recognition of pathological tissues and cells. Consequently, there exists a pressing need to develop improved strategies for concurrently achieving the aforementioned objectives. Such strategies will be discussed in further detail below, with particular emphasis on the MSV.

4.1. Geometrical targeting strategies

In the field of nanomedicine, geometrical targeting has been used as a strategy to achieve preferential accumulation of nanoparticles within the body. In particular, this approach involves the modulation of particle size and shape. In fact, endogenous components of the circulatory system, i.e. platelets, erythrocytes, and lymphocytes, exhibit distinct geometrical features that endow them with unique transport properties. For instance, the deformability and morphological characteristics of red blood cells enables passage through small capillaries [51, 52], while the shape of activated platelets facilitates binding to injured vasculature [53, 54]. Ultimately, geometrical targeting is based on the assumption that various organs and pathological tissues display unique physical properties. For example, variations in physical characteristics can be attributed to the anatomical organization of vascular networks and structural features of individual blood vessels.

The best-known example of geometrical targeting is the utilization of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, a phenomenon that is characteristic of tumors [55-58]. The first FDA-approved nanodrug, Doxil [59], and the vast majority of clinically approved nanotheraapeutics rely on the EPR effect. Notably, the survival of tumors that are larger than a few millimeters in diameter is dependent on the successful recruitment of new blood vessels, a process termed angiogenesis [60-62]. Although the newly formed tumor endothelium is capable of supplying cancer cells with oxygen and nutrients, it lacks several features of normal blood vessels. For instance, immature vasculature typically displays reduced pericyte coverage and fewer tight junctions, consequently permitting the formation of large endothelial fenestrations (<600 nm) [63]. Indeed, the presence of such fenestrations enables increased penetration of nanoparticles into tumor tissue. The second part of the EPR effect, which involves enhanced retention of nanoparticles in tumors, is usually accredited to abnormal blood flow patterns and a lack of lymphatic drainage [64, 65]. Furthermore, it is possible that the characteristic buildup of extracellular matrix molecules in malignant tissue [66, 67] endows the tumor microenvironment with superior adhesive properties, thereby increasing nanoparticle retention. However, it is worth noting that increased interactions with extracellular matrix components may also impede nanoparticle diffusion throughout the tumor interstitium. In essence, the vast majority of nanoparticles can benefit from the EPR effect, since they fall within the size constraints of tumor fenestrations. Nevertheless, it is likely that different tumor types display considerable heterogeneity in regards to the EPR effect [68, 69]. In addition to nanoparticle size, other properties such as shape, charge, and deformability can be exploited to achieve localized delivery. Strategies that involve the modification of physical properties have commonly been referred to as passive targeting. The term ‘passive’ is mostly a reflection of the EPR effect, wherein few, if any, alterations to nanoparticle size are necessary in order to exploit this phenomenon. Likewise, nanoparticles larger than 5.5 nm can avoid renal clearance [70], which is a major biological barrier for the retention of small molecules. However, when it comes to other examples of physical targeting, particle design is anything but a passive process. Namely, small changes in physical parameters can have considerable consequences for particle biodistribution.

In the case of the MSV, physical targeting strategies have mainly relied on optimization of particle size and shape. While the second stage of the MSV can exploit the EPR effect, the first stage is designed to take advantage of unique blood flow patterns in tumors. Interestingly, the vast majority of nanoparticles designed for medical applications are spherical in shape, although spheres do not necessarily display optimal transport properties. It is notable that very few components of the vascular system resemble spherical structures. For example, most cells and biological fragments in the blood possess a discoid morphology, while albumin, the most abundant plasma protein, has a prolate ellipsoid structure [71]. These observations suggest that globular objects may be less capable of performing biological functions. It is likely that the limited contact surface of spheres dramatically reduces the occurrence of biological interactions, which lay the foundation for a well-functioning system. In the case of platelets, their discoidal structure and size (1.5-3 μm in diameter [72]) facilitate binding to inflamed vasculature [53, 54]. Moreover, these geometrical properties also induce platelets to flow within a cell-free layer close to the endothelium [73, 74]. The blood flow patterns and binding capability of platelets make them an ideal model for designing particles that target inflamed vasculature. In fact, the characteristics of the first stage MSV particle, such as size, shape, and rigidity, closely resemble those of platelets.

Mathematical modeling [75, 76] and experimental studies [77, 78] have also revealed that the first stage MSV particle exhibits increased margination against the vascular wall and improved binding to endothelial cells in comparison to spherical- or rod-shaped particles (Fig. 3a). In particular, discoidal particles tend to drift laterally alongside the vascular wall, a phenomenon that is especially evident for particles with low aspect ratios and micron-sized dimensions [75]. The probability that particles will adhere to the endothelium increases with decreasing shear rate [78]. Importantly, tumors display highly abnormal blood flow patterns that can be exploited when designing drug delivery vehicles [4]. For example, the microcirculation of normal tissues typically exhibits a shear rate larger than 100 s−1, while tumor blood vessels usually possess shear rates smaller than 100 s−1 [78, 79]. Consequently, such differences in blood flow can promote adhesion of discoidal microparticles to tumor vasculature. Accordingly, in an orthotopic mouse model of breast cancer, the first stage MSV particles displayed five times higher accumulation in tumor tissue in comparison to spherical silicon particles with similar diameters [9]. Additionally, another study demonstrated that discoidal silicon particles exhibited the highest levels of lung accumulation in comparison to cylindrical (diameter ≈ height), spherical, and quasi-hemispherical silicon particles [80].

Figure 3.

Strategies for obtaining localized delivery of MSVs to tumor tissue. a, Geometrical targeting. The micron-sized structure and discoidal shape of MSVs enable increased margination against tumor vasculature in comparison to spherical nanoparticles. b, Molecular targeting. Targeting ligands on the surface of the MSVs promote binding to biological markers on tumor endothelium. c, Biomimetic targeting. MSVs coated with leukocyte membranes mimic leukocyte adherence to inflamed vasculature.

The precise dimensions of discoidal microparticles can be further optimized to improve biodistribution. In a mouse model of melanoma, intravenous injection of small (600 × 200 nm), medium-sized (1000 × 400 nm), and large (1800 × 600 nm) MSVs resulted in tumor accumulation levels of 1.2%, 5.1%, and 3.2% (injected dose/g tissue), respectively [77]. Furthermore, particle concentration in tumor tissue correlated with vascular adhesion strength, as measured with a flow-chamber apparatus, indicating that the capability of particles to adhere to endothelium is likely to be a critical determinant of tumor accumulation. Notably, finding an optimal balance between maximizing surface area and minimizing susceptibility to hydrodynamic dislodging forces is important for achieving superior particle-vasculature interactions [76, 78, 81], providing a possible explanation as to why the medium-sized microparticles exhibited stronger adhesion. Additionally, the small silicon particles displayed the highest liver and spleen retention, which could be due to increased clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system [77]. Indeed, the same study demonstrated that the small silicon particles were more rapidly taken up by macrophages in cell culture in comparison to the larger silicon particles.

In conclusion, the first and second stage vectors of the MSV both utilize geometrical targeting strategies. Namely, the first stage microparticle exploits abnormal blood flow patterns in tumor tissue, while the second stage nanoparticles take advantage of structural abnormalities in tumor blood vessels. The reduced shear rate in tumor vasculature enables binding of discoidal particles to the vessel wall. Once the first stage microparticle has attached to tumor endothelium, the second stage nanoparticles can enter the tumor interstitium by passing through fenestrations in the vascular wall, thus utilizing the EPR effect.

4.2. Molecular targeting strategies

Another strategy for improving the biodistribution of nanoparticles is the use of surface ligands that bind to specific biological targets associated with pathological tissue. Traditionally, this approach has been termed ‘active targeting’, although the terminology can generate confusion. Indeed, the implementation of this strategy does not involve an active targeting mechanism, since transport of systemically injected nanoparticles predominantly relies on blood flow. Instead, the main function of targeting moieties is usually to increase retention and/or cellular uptake of nanoparticles after they have reached an intended location. In this regard, the term ‘active targeting’ should not be associated with the assignment of motile properties to nanoparticles. Moreover, it is worth noting that the use of suitable functional ligands does not guarantee increased tissue retention or cellular internalization of nanoparticles, since other factors can interfere with molecular recognition. In particular, binding interactions between surface ligands and biological targets can be prevented in the presence of a dense protein corona, which forms upon nanoparticle exposure to biological fluids [82, 83]. For instance, it was shown that the binding capacity of transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles to target receptors diminishes with increasing protein concentrations [84]. Additionally, some studies have demonstrated that the conjugation of tumor-specific antibodies to nanoparticles does not increase tumor accumulation [85, 86]. Indeed, targeting ligands increase the size of nanoparticles and potentially enhance immunological activation, thereby impeding the penetration of biological barriers [1, 87]. Although the results of molecular targeting have been less impressive than initially anticipated [47, 87], this approach is likely to yield promising results when combined with other targeting strategies. In fact, several ligand-functionalized nanotherapeutics are currently undergoing clinical trials [44, 88], and the coming years will be crucial in revealing the true potential of active targeting.

For the most part, molecular targeting can be divided into two categories based on whether the target cells are part of the vasculature or parenchyma [89, 90]. Functionalization of nanoparticles with ligands that bind to endothelial cells can cause retention at an earlier stage, while targeting of parenchymal cells can promote cellular internalization in cells that from the bulk of pathological tissue. In the field of oncology, nanoparticles that bind to markers of neovasculature could have broader application than those that target a specific type of cancer [89, 90]. Furthermore, endothelial cells are less likely to cease expression of surface markers as a mechanism of drug resistance, since these cells typically display a stable genome. In essence, the above-mentioned factors should be carefully weighed when selecting which types of ligands to use. For a detailed overview on active targeting in nanomedicine, please refer to a review by Byrne et al. [89].

In regards to the MSV, molecular targeting approaches have involved the use of ligands that recognize tumor vasculature (Fig. 3b), since the first stage of the delivery vehicle is primarily designed to form vascular depots in diseased endothelium. Consequently, molecular targeting of the MSV does not interfere with the penetration of biological barriers, as can be the case for nanoparticles that are intended to cross the vessel wall. Recent studies have demonstrated that E-selectin presents a promising target for preferential accumulation of MSVs in the bone marrow [22, 91]. This endothelial marker is predominantly expressed in normal bone marrow vasculature [92] and inflamed vessels [93]. The close connection between cancer and inflammation [94] makes E-selectin a suitable marker for targeting cancerous lesions in the bone. Indeed, surface conjugation with a thioaptamer for E-selectin caused a fivefold increase in MSV accumulation in the bone marrow of mice with breast cancer bone metastasis [22]. In regards to pancreatic cancer, clinical samples and murine tumor models have revealed that tumor-associated endothelial cells and macrophages display increased levels of CD59 (human)/Ly6C (mouse) [95]. In mice bearing orthotopic pancreatic tumors, functionalization with antibodies against this glycoprotein caused tumor accumulation of MSVs to increase from 0.5% to 9.8% (injected dose/g tissue) [95].

Other strategies employed to promote docking of MSVs to tumor endothelium have exploited the immature characteristics of cancer blood vessels. The newly formed tumor endothelium displays distinct properties that differ from those of mature vasculature. For instance, αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins [96, 97] and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) [61, 98] are expressed in high levels on tumor blood vessels. The RGD (arginine-glycine-asparagine) peptide, which is a known ligand for αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins [97, 99], was used as a targeting agent for MSVs, consequently resulting in a twofold increase in tumor accumulation in a mouse model of melanoma [77]. Similarly, in a murine model of orthotopic breast cancer, conjugation with an antibody against VEGFR2 led to a threefold increase in MSV tumor accumulation [100]. Taken together, these in vivo studies indicate a clear improvement in MSV tumor accumulation as a result of molecular targeting. Nevertheless, the benefits seen with targeting ligands may not have been possible without concurrent geometrical targeting, which initially promotes interactions between MSVs and tumor endothelium. Indeed, one of the factors that makes the MSV unique is the combination of several targeting strategies (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Concurrent strategies for obtaining targeted delivery of MSVs. a, Schematic illustration of a blood vessel with red blood cells and MSVs. The discoidal shape of the MSV promotes lateral drifting of particles, resulting in recurrent interactions with endothelial cells (margination). The large surface area of the MSV stimulates non-specific and ligand-based interactions with endothelial cells, thereby enabling adhesion. The degradation of silicon releases nanoparticles, which can pass through endothelial fenestrations by exploiting the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. In summary, geometrical targeting (shape-based margination, shape-based adhesion, and the EPR effect) and molecular targeting (ligand-based adhesion) are concurrently utilized to obtain preferential accumulation of drugs. b, SEM images of MSVs adhered to tumor vasculature. Endothelial fenestrations are visible in the left image. Scale bar, 1 μm. c, Intravital microscopy images of a blood vessel at different time points. The images display MSVs at various stages in the targeting process: i) particles moving freely in the circulation, ii) particles moving at a lower speed while marginating against the endothelium, and iii) particles adhered to the vessel wall. Scale bar, 50 μm. Partially reproduced from [77] with permission.

4.3. Biomimetic targeting strategies

The third targeting strategy that has been used in conjunction with the MSV is based on biomimicry. As previously discussed, biologically inspired strategies for improving geometrical targeting have yielded promising results, however, biomimicry can be further exploited through imitation of biological surfaces. In particular, MSVs have been coated with cell membranes derived from leukocytes, yielding a camouflaged particle named the leukolike vector (Fig. 3c) [101]. The membrane coating caused a reduction in immunological recognition and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system, a critical biological barrier consisting of circulating monocytes and resident macrophages in the liver and spleen. In fact, a substantial amount of systemically injected particles typically accumulate in these organs due to immunological clearance [47]. Traditionally, stealth polymers, such as PEG, have been used to reduce particle opsonization, thereby decreasing macrophage uptake and prolonging blood circulation times [102-104]. Nevertheless, repeated injections of pegylated nanoparticles can give rise to the formation of antibodies against PEG, thereby resulting in accelerated clearance of these particles [105]. Additionally, studies have shown that PEG can activate the complement system, potentially causing adverse reactions in sensitive individuals [106, 107]. Notably, the leukolike vector was shown to dramatically reduce liver accumulation in comparison to uncoated MSVs [101], thereby providing a viable alternative to stealth polymers. Additionally, the membrane coated MSVs displayed increased interactions with inflamed vasculature and elevated uptake in tumor tissue [101]. Indeed, leukocytes possess membrane proteins that promote adherence to inflamed endothelium and induce transendothelial migration [108]. Proteomic analysis of the leukolike coating confirmed that such proteins were successfully transferred to the MSV surface [109], while stability studies revealed that the leukolike retained its coating following intravenous injection [101]. Notably, the membrane proteins on the MSV surface remained biologically active, as was evident from their ability to increase endothelial permeability [101]. Conceivably, such cell-like properties could permit delivery vehicles to promptly respond to dynamic changes in the microenvironment.

Future use of the leukolike in the clinical setting is likely to fall within the realm of personalized medicine in order to ensure self-recognition. In practice, this would involve obtaining coating material directly from the patient prior to therapy. Moreover, it is likely that the leukolike concept could be expanded to involve the use of membranes from other cell types, potentially enabling treatment of a broad range of pathological conditions associated with inflammation.

5. Payload diversity

A major advantage of the MSV platform is improved spatiotemporal delivery of nanotherapeutics. The binding of MSVs to inflamed vasculature results in an improvement in the spatial distribution of nanoparticles. Namely, nanoparticles are released in close proximity to pathological cells, as opposed to passing through the entire circulatory system. Likewise, the temporal distribution of nanoparticles is more desirable as a result of MSV delivery. Specifically, the gradual degradation of the porous silicon microparticles enables sustained release of nanoparticles, thereby reducing fluctuations in drug levels. Indeed, drug concentrations outside the therapeutic range can cause undesirable effects, such as toxicity (super-therapeutic levels) and reduced efficacy (subtherapeutic levels). Furthermore, prolonged periods of exposure to low drug concentrations can promote the emergence of drug resistance in cancer cells [110]. Taken together, these factors suggest that considerable benefits can be gained through the use of sustained release platforms, such as the MSV.

Another advantage of the MSV system is high versatility and wide applicability, which stem from the possibility to incorporate a broad range of different nanoparticles and therapeutic agents into the MSV. Accordingly, this enables the second stage nanoparticles to be tailored to the specific biological barriers that are associated with a given application. In fact, while the first stage of the MSV is designed to address biological barriers in the vascular compartment, the second stage is devised to overcome transport obstacles in the tissue interstitium and cell interior. Previously, in vitro and in vivo studies have employed liposomes [21-26], micelles [111], and various polymeric nanoparticles [15, 19, 27, 112] as second stage vectors in the MSV platform. Nevertheless, the application of the MSV delivery system in not restricted to the use of these nanoparticles. In actuality, the platform has also been used for the delivery of contrast agents [20, 113, 114], quantum dots [115, 116], and carbon nanotubes [116] for diagnostic and imaging purposes, indicating that the MSV would be well-suited as a theranostic platform. A major advantage of employing MSVs for imaging purposes is that the relaxivity of contrast agents can be improved as a result of geometrical confinement. Specifically, the spatial arrangement of contrast agents within the silicon pores can enhance image contrast through decreasing water mobility, increasing the clustering of the payload, and reducing contrast agent tumbling [20, 113, 114].

Similarly to the second stage, the third stage can be customized based on the molecular abnormalities that characterize a pathological condition. In particular, siRNAs [15, 19, 21-27], micro RNAs (miRNAs) [19], chemotherapeutic agents [111, 112], and antibiotics [117] have been employed as third stage payloads. Furthermore, in a variation of this drug delivery approach, gold nanoparticles were utilized both as a second stage vector and as a therapeutic agent [118]. Specifically, mice bearing orthotopic breast cancer tumors were exposed to MSVs loaded with hollow gold nanoshells. The tumors were then treated with near-infrared light to induce thermal ablation of cancer cells.

As mentioned above, the second stage nanoparticles must overcome a set of biological barriers that are encountered at a later stage following intravenous injection. Accordingly, a major advantage gained from the use of nanoparticles is enhanced protection of therapeutic agents. In particular, molecules that are sensitive to degradation, such as siRNAs and miRNAs, require protection from catabolic enzymes [119-122]. Moreover, while small molecules can easily cross the cell membrane, the bulky structure and negative charge of siRNAs and miRNAs impede cellular uptake [119, 120, 122]. Consequently, the cell membrane stands out as a predominant biological barrier for nucleic acids. However, nanoparticles can greatly facilitate intracellular uptake of therapeutic molecules through endocytosis [123, 124]. In particular, nanoparticles that possess a positive charge can form strong interactions with the cell membrane [120]. Indeed, PEI-based polyplexes that were released from the MSV promoted cellular uptake of siRNAs [15, 19, 27]. Additionally, these nanoparticles were shown to induce lysosomal escape of siRNAs [19, 27], presumably through the proton sponge effect [125] or other mechanisms of membrane damage [126, 127]. Importantly, siRNA therapeutics must be released into the cytoplasm in order to form a complex with target messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules [119, 120]. In addition, the lysosome contains a multitude of enzymes that rapidly degrade biomolecules, thereby posing a large threat to the integrity of siRNAs [119, 120]. Furthermore, nanoparticles can also increase the anticancer efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents through circumvention of efflux pumps, which are major contributors to drug resistance [128, 129]. Multidrug resistance can be prevented due to differences in pathways of intracellular uptake and trafficking between nanoparticles and free drugs.

Notably, while the second stage nanoparticles are able to overcome several biological barriers, the first stage microcomponent is necessary to ensure superior therapeutic efficacy. Indeed, studies have illustrated that the MSV consistently outperforms freely injected second stage nanoparticles. For example, in an orthotopic breast cancer model, a single injection of MSVs containing paclitaxel-loaded polymeric nanoparticles resulted in a dramatic and sustained inhibition of tumor growth over a period of 35 days [112]. On the contrary, the same study demonstrated that a single injection of paclitaxel-loaded polymeric nanoparticles failed to halt tumor growth. Additionally, the MSV particles performed better than the Chremophor EL formulation of paclitaxel that is used in the clinic [112]. Furthermore, in mice bearing orthotropic ovarian tumors, an intravenous injection of MSVs containing siRNA liposomes resulted in a sixfold increase in siRNA tumor accumulation in comparison to injection of siRNA liposomes [21]. This study also revealed that six repeated injections of siRNA liposomes with a cumulative dose of 30 μg of siRNA was necessary to achieve a similar reduction in tumor growth as a single injection of 15 μg of siRNA encapsulated in liposomes inside the MSV. Recently, liposome-loaded MSVs were used to deliver siRNA against XBP1, which plays an important role in the unfolded protein response [23]. Suppression of XBP1 inhibited tumor growth in murine models of human triple negative breast cancer. Additionally, recent work demonstrated that MSVs carrying siRNA against ribosomal protein L39 (RPL39) and myeloid leukemia factor 2 (MLF2), which are proteins involved in the nitric oxide synthase pathway, were able to decrease tumor volume, reduce metastasis, and suppress cancer stem cells in breast cancer models [24].

Furthermore, an alternative approach to MSV-based therapy is the use of porous silicon particles for immunotherapy or as cancer vaccines. Specifically, MSVs loaded with liposomes containing human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) antigen were systemically injected into mice bearing HER2-positive breast cancer tumors [130]. The results from this study demonstrate that tumor growth was inhibited and survival prolonged in response to treatment. Moreover, even greater therapeutic efficacy was achieved upon intravenous injection of dendritic cells that had been primed with antigenloaded MSVs. Additionally, the MSVs displayed a cancer preventive function, which was evident from a reduction in the formation of spontaneous tumors [130]. The proposed mechanism for enhanced therapeutic efficacy was MSV-induced phagocytosis, which triggered increased antigen cross-presentation through activation of type-I interferon (IFN-I) signaling [130]. In summary, the MSV platform permits a multipronged approach to drug delivery where vast combinations of nanoparticles and therapeutic agents can be produced, enabling a tailored solution for the treatment of a broad spectrum of medical conditions.

6. Conclusions and outlook

Localized delivery of therapeutic agents is contingent upon effective penetration of biological barriers and successful recognition of target tissues and cells. These functions must be performed in a coordinated manner in order to obtain controlled distribution of drugs. Notably, the circulatory system, the tissue interstitium, and the cell interior form three distinct compartments that each possesses a specific set of transport obstacles. In this regard, a multifunctional approach is necessary to achieve preferential accumulation of drugs in pathological tissue. In the case of the MSV, multifunctionality is realized through the integration of several components that form three sequential stages. The first stage vector consists of a porous silicon microparticle that forms vascular depots in tumor endothelium as a result of geometrical targeting. Moreover, adhesion to abnormal vasculature can be further promoted by the implementation of molecular and biomimetic targeting strategies. Gradual degradation of the silicon material results in sustained release of second stage nanoparticles that can enter tissue interstitium through vascular fenestrations. The nanoparticles further protect the therapeutic payload from degradation, aid in cellular uptake, and address intracellular barriers. The drug delivery process is finally completed upon release of the third stage therapeutic agent.

In essence, the MSV platform is able to concurrently recognize pathological tissues and overcome biological barriers. The coupling of recognition and transportenhancing properties represents a unique way of approaching drug delivery. Furthermore, the MSV can be considered an epitome of personalized medicine, due to the tunable parameters of the first stage vector and the wide variety of second stage vectors and third stage payloads that can be incorporated into the platform. While the therapeutic agents can be tailored to abnormal molecular pathways in individual patients, the microparticle and nanoparticle components can be customized to address interpatient variations in biological barriers. Indeed, modulation of the size, shape, pore size, porosity, and surface functionalization of the first stage vector represents a physics-based approach to personalization. In conclusion, the MSV enables customization of medical treatments based on the selection of distinct recognition properties, transport properties, and therapeutic agents.

The favorable safety profiles and superior therapeutic efficacies observed in multiple animal studies have prompted the clinical development of the MSV. The procedures for enabling large-scale production have been established and a cGMP toxicity study is currently in the course of completion. Furthermore, the initial planning stages of clinical trials are currently underway and an investigational new drug (IND) application is expected to be filed within the next 24 months. The next few years will bring several new challenges for the future development of the MSV, but also provide an avenue to potentially translate a decade of preclinical research into effective treatments for patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Houston Methodist Research Institute. Partial funds were acquired from: the Ernest Cockrell Jr. Distinguished Endowed Chair (M.F.), the US Department of Defense (W81XWH-09-1-0212, W81XWH-12-1-0414) (M.F.), the National Institute of Health (U54CA143837, U54CA151668) (M.F.), Nylands nation Finland (J.W.), Victoriastiftelsen Finland (J.W.), and the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (RP121071) (M.F. and H.S.). We sincerely thank Matthew Landry for assistance with figures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ferrari M. Frontiers in cancer nanomedicine: directing mass transport through biological barriers. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari M. Cancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:161–171. doi: 10.1038/nrc1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010;7:653–664. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sriraman SK, Aryasomayajula B, Torchilin VP. Barriers to drug delivery in solid tumors. Tissue Barriers. 2014;2:e29528. doi: 10.4161/tisb.29528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michor F, Liphardt J, Ferrari M, Widom J. What does physics have to do with cancer? Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:657–670. doi: 10.1038/nrc3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sengupta S, Eavarone D, Capila I, Zhao G, Watson N, Kiziltepe T, Sasisekharan R. Temporal targeting of tumour cells and neovasculature with a nanoscale delivery system. Nature. 2005;436:568–572. doi: 10.1038/nature03794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Maltzahn G, Park JH, Lin KY, Singh N, Schwoppe C, Mesters R, Berdel WE, Ruoslahti E, Sailor MJ, Bhatia SN. Nanoparticles that communicate in vivo to amplify tumour targeting. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:545–552. doi: 10.1038/nmat3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godin B, Chiappini C, Srinivasan S, Alexander JF, Yokoi K, Ferrari M, Decuzzi P, Liu X. Discoidal Porous Silicon Particles: Fabrication and Biodistribution in Breast Cancer Bearing Mice. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012;22:4225–4235. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201200869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiappini C, Tasciotti E, Serda RE, Brousseau L, Liu X, Ferrari M. Mesoporous silicon particles as intravascular drug delivery vectors: fabrication, in-vitro, and in-vivo assessments. Phys. Status Solidi. 2011;C(8):1826–1832. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez JO, Chiappini C, Ziemys A, Faust AM, Kojic M, Liu X, Ferrari M, Tasciotti E. Engineering multi-stage nanovectors for controlled degradation and tunable release kinetics. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8469–8477. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez JO, Evangelopoulos M, Chiappini C, Liu X, Ferrari M, Tasciotti E. Degradation and biocompatibility of multistage nanovectors in physiological systems. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2014;102:3540–3549. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzur-Balter A, Shatsberg Z, Beckerman M, Segal E, Artzi N. Mechanism of erosion of nanostructured porous silicon drug carriers in neoplastic tissues. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6208. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liou GY, Storz P. Reactive oxygen species in cancer. Free Radic. Res. 2010;44:479–496. doi: 10.3109/10715761003667554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen J, Wu X, Lee Y, Wolfram J, Mao Z, Ferrari M, Shen H. Porous silicon microparticles for delivery of siRNA therapeutics. J. Vis. Exp. 2015;15:52075. doi: 10.3791/52075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serda RE, Blanco E, Mack A, Stafford SJ, Amra S, Li Q, van de Ven A, Tanaka T, Torchilin VP, Wiktorowicz JE, Ferrari M. Proteomic analysis of serum opsonins impacting biodistribution and cellular association of porous silicon microparticles. Mol. Imaging. 2011;10:43–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godin B, Gu J, Serda RE, Bhavane R, Tasciotti E, Chiappini C, Liu X, Tanaka T, Decuzzi P, Ferrari M. Tailoring the degradation kinetics of mesoporous silicon structures through PEGylation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2010;94:1236–1243. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godin B, Gu J, Serda RE, Ferrati S, Liu X, Chiappini C, Tanaka T, Decuzzi P, Ferrari M. Multistage Mesoporous Silicon-based Nanocarriers: Biocompatibility with Immune Cells and Controlled Degradation in Physiological Fluids. Controll. Release Newsl. 2008;25:9–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen J, Xu R, Mai J, Kim HC, Guo X, Qin G, Yang Y, Wolfram J, Mu C, Xia X, Gu J, Liu X, Mao ZW, Ferrari M, Shen H. High capacity nanoporous silicon carrier for systemic delivery of gene silencing therapeutics. ACS Nano. 2013;7:9867–9880. doi: 10.1021/nn4035316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ananta JS, Godin B, Sethi R, Moriggi L, Liu X, Serda RE, Krishnamurthy R, Muthupillai R, Bolskar RD, Helm L, Ferrari M, Wilson LJ, Decuzzi P. Geometrical confinement of gadolinium-based contrast agents in nanoporous particles enhances T1 contrast. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5:815–821. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka T, Mangala LS, Vivas-Mejia PE, Nieves-Alicea R, Mann AP, Mora E, Han HD, Shahzad MM, Liu X, Bhavane R, Gu J, Fakhoury JR, Chiappini C, Lu C, Matsuo K, Godin B, Stone RL, Nick AM, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK, Ferrari M. Sustained small interfering RNA delivery by mesoporous silicon particles. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3687–3696. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mai J, Huang Y, Mu C, Zhang G, Xu R, Guo X, Xia X, Volk DE, Lokesh GL, Thiviyanathan V, Gorenstein DG, Liu X, Ferrari M, Shen H. Bone marrow endothelium-targeted therapeutics for metastatic breast cancer. J. Control. Release. 2014;187:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Iliopoulos D, Zhang Q, Tang Q, Greenblatt MB, Hatziapostolou M, Lim E, Tam WL, Ni M, Chen Y, Mai J, Shen H, Hu DZ, Adoro S, Hu B, Song M, Tan C, Landis MD, Ferrari M, Shin SJ, Brown M, Chang JC, Liu XS, Glimcher LH. XBP1 promotes triple-negative breast cancer by controlling the HIF1alpha pathway. Nature. 2014;508:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dave B, Granados-Principal S, Zhu R, Benz S, Rabizadeh S, Soon-Shiong P, Yu KD, Shao ZM, Li XX, Gilcrease M, Lai Z, Cheng YD, Huang THM, Shen HF, Liu XW, Ferrari M, Zhan M, Wong STC, Kumaraswami M, Mittal V, Chen X, Gross SS, Chang JC. Targeting RPL39 and MLF2 reduces tumor initiation and metastasis in breast cancer by inhibiting nitric oxide synthase signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:8838–8843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320769111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu R, Huang Y, Mai J, Zhang G, Guo X, Xia X, Koay EJ, Qin G, Erm DR, Li Q, Liu X, Ferrari M, Shen H. Multistage vectored siRNA targeting ataxiatelangiectasia mutated for breast cancer therapy. Small. 2013;9:1799–1808. doi: 10.1002/smll.201201510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen H, Rodriguez-Aguayo C, Xu R, Gonzalez-Villasana V, Mai J, Huang Y, Zhang G, Guo X, Bai L, Qin G, Deng X, Li Q, Erm DR, Aslan B, Liu X, Sakamoto J, Chavez-Reyes A, Han HD, Sood AK, Ferrari M, Lopez-Berestein G. Enhancing chemotherapy response with sustained EphA2 silencing using multistage vector delivery. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2013;19:1806–1815. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang M, Xu R, Xia X, Yang Y, Gu J, Qin G, Liu X, Ferrari M, Shen H. Polycation-functionalized nanoporous silicon particles for gene silencing on breast cancer cells. Biomaterials. 2014;35:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos HA, Makila E, Airaksinen AJ, Bimbo LM, Hirvonen J. Porous silicon nanoparticles for nanomedicine: preparation and biomedical applications. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2014;9:535–554. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shahbazi MA, Herranz B, Santos HA. Nanostructured porous Si-based nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery. Biomatter. 2012;2:296–312. doi: 10.4161/biom.22347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlisle EM. Silicon as an essential trace element in animal nutrition. Ciba Found. Symp. 1986;121:123–139. doi: 10.1002/9780470513323.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jugdaohsingh R, Anderson SH, Tucker KL, Elliott H, Kiel DP, Thompson RP, Powell JJ. Dietary silicon intake and absorption. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002;75:887–893. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jurkic LM, Cepanec I, Pavelic SK, Pavelic K. Biological and therapeutic effects of ortho-silicic acid and some ortho-silicic acid-releasing compounds: New perspectives for therapy. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 2013;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivanov S, Zhuravsky S, Yukina G, Tomson V, Korolev D, Galagudza M. In Vivo Toxicity of Intravenously Administered Silica and Silicon Nanoparticles. Materials. 2012;5:1873–1889. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang QY, Wang ZY, Wen F, Ren L, Li J, Teoh SH, Thian ES. Gelatin-siloxane nanoparticles to deliver nitric oxide for vascular cell regulation: synthesis, cytocompatibility, and cellular responses. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2015;103:929–938. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian XH, Wang ZG, Meng H, Wang YH, Feng W, Wei F, Huang ZC, Lin XN, Ren L. Tat peptide-decorated gelatin-siloxane nanoparticles for delivery of CGRP transgene in treatment of cerebral vasospasm. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2013;8:865–876. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S39951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin FJ, Melnik K, West T, Shapiro J, Cohen M, Boiarski AA, Ferrari M. Acute toxicity of intravenously administered microfabricated silicon dioxide drug delivery particles in mice: preliminary findings. Drugs R. D. 2005;6:71–81. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200506020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Absher MP, Trombley L, Hemenway DR, Mickey RM, Leslie KO. Biphasic cellular and tissue response of rat lungs after eight-day aerosol exposure to the silicon dioxide cristobalite. Am. J. Pathol. 1989;134:1243–1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnston CJ, Driscoll KE, Finkelstein JN, Baggs R, O'Reilly MA, Carter J, Gelein R, Oberdorster G. Pulmonary chemokine and mutagenic responses in rats after subchronic inhalation of amorphous and crystalline silica. Toxicol. Sci. 2000;56:405–413. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/56.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka T, Godin B, Bhavane R, Nieves-Alicea R, Gu J, Liu X, Chiappini C, Fakhoury JR, Amra S, Ewing A, Li Q, Fidler IJ, Ferrari M. In vivo evaluation of safety of nanoporous silicon carriers following single and multiple dose intravenous administrations in mice. Int. J. Pharm. 2010;402:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu J, Erogbogbo F, Yong KT, Ye L, Liu J, Hu R, Chen H, Hu Y, Yang Y, Yang J, Roy I, Karker NA, Swihart MT, Prasad PN. Assessing clinical prospects of silicon quantum dots: studies in mice and monkeys. ACS Nano. 2013;7:7303–7310. doi: 10.1021/nn4029234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park JH, Gu L, von Maltzahn G, Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN, Sailor MJ. Biodegradable luminescent porous silicon nanoparticles for in vivo applications. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:331–336. doi: 10.1038/nmat2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bimbo LM, Sarparanta M, Santos HA, Airaksinen AJ, Makila E, Laaksonen T, Peltonen L, Lehto VP, Hirvonen J, Salonen J. Biocompatibility of thermally hydrocarbonized porous silicon nanoparticles and their biodistribution in rats. ACS Nano. 2010;4:3023–3032. doi: 10.1021/nn901657w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weissig V, Pettinger TK, Murdock N. Nanopharmaceuticals (part 1): products on the market. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2014;9:4357–4373. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S46900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Etheridge ML, Campbell SA, Erdman AG, Haynes CL, Wolf SM, McCullough J. The big picture on nanomedicine: the state of investigational and approved nanomedicine products. Nanomedicine. 2013;9:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mehlen P, Puisieux A. Metastasis: a question of life or death. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:449–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strebhardt K, Ullrich A. Paul Ehrlich's magic bullet concept: 100 years of progress. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:473–480. doi: 10.1038/nrc2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bae YH, Park K. Targeted drug delivery to tumors: myths, reality and possibility. J. Control. Release. 2011;153:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li KC, Pandit SD, Guccione S, Bednarski MD. Molecular imaging applications in nanomedicine. Biomed. Microdevices. 2004;6:113–116. doi: 10.1023/b:bmmd.0000031747.05317.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki R, Takizawa T, Kuwata Y, Mutoh M, Ishiguro N, Utoguchi N, Shinohara A, Eriguchi M, Yanagie H, Maruyama K. Effective anti-tumor activity of oxaliplatin encapsulated in transferrin-PEG-liposome. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;346:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chau Y, Dang NM, Tan FE, Langer R. Investigation of targeting mechanism of new dextran-peptide-methotrexate conjugates using biodistribution study in matrix-metalloproteinase-overexpressing tumor xenograft model. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006;95:542–551. doi: 10.1002/jps.20548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skalak R, Branemark PI. Deformation of red blood cells in capillaries. Science. 1969;164:717–719. doi: 10.1126/science.164.3880.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suzuki Y, Tateishi N, Soutani M, Maeda N. Deformation of erythrocytes in microvessels and glass capillaries: effects of erythrocyte deformability. Microcirculation. 1996;3:49–57. doi: 10.3109/10739689609146782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maxwell MJ, Dopheide SM, Turner SJ, Jackson SP. Shear induces a unique series of morphological changes in translocating platelets: effects of morphology on translocation dynamics. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:663–669. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000201931.16535.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuwahara M, Sugimoto M, Tsuji S, Matsui H, Mizuno T, Miyata S, Yoshioka A. Platelet shape changes and adhesion under high shear flow. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002;22:329–334. doi: 10.1161/hq0202.104122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maeda H, Nakamura H, Fang J. The EPR effect for macromolecular drug delivery to solid tumors: Improvement of tumor uptake, lowering of systemic toxicity, and distinct tumor imaging in vivo. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013;65:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. J. Control. Release. 2000;65:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maeda H. Macromolecular therapeutics in cancer treatment: the EPR effect and beyond. J. Control. Release. 2012;164:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barenholz Y. Doxil(R)--the first FDA-approved nano-drug: lessons learned. J. Control. Release. 2012;160:117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roskoski R., Jr. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling in tumor progression. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2007;62:179–213. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greenblatt M, Shubi P. Tumor angiogenesis: transfilter diffusion studies in the hamster by the transparent chamber technique. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1968;41:111–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yuan F, Dellian M, Fukumura D, Leunig M, Berk DA, Torchilin VP, Jain RK. Vascular permeability in a human tumor xenograft: molecular size dependence and cutoff size. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3752–3756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fang J, Nakamura H, Maeda H. The EPR effect: Unique features of tumor blood vessels for drug delivery, factors involved, and limitations and augmentation of the effect. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011;63:136–151. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Torchilin V. Tumor delivery of macromolecular drugs based on the EPR effect. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011;63:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gilkes DM, Semenza GL, Wirtz D. Hypoxia and the extracellular matrix: drivers of tumour metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:430–439. doi: 10.1038/nrc3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bogart LK, Pourroy G, Murphy CJ, Puntes V, Pellegrino T, Rosenblum D, Peer D, Levy R. Nanoparticles for imaging, sensing, and therapeutic intervention. ACS Nano. 2014;8:3107–3122. doi: 10.1021/nn500962q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prabhakar U, Maeda H, Jain RK, Sevick-Muraca EM, Zamboni W, Farokhzad OC, Barry ST, Gabizon A, Grodzinski P, Blakey DC. Challenges and key considerations of the enhanced permeability and retention effect for nanomedicine drug delivery in oncology. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2412–2417. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, Tanaka E, Zimmer JP, Itty Ipe B, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1165–1170. doi: 10.1038/nbt1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wright AK, Thompson MR. Hydrodynamic structure of bovine serum albumin determined by transient electric birefringence. Biophys. J. 1975;15:137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(75)85797-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thon JN, Macleod H, Begonja AJ, Zhu J, Lee KC, Mogilner A, Hartwig JH, Italiano JE., Jr. Microtubule and cortical forces determine platelet size during vascular platelet production. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:852. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aarts PA, van den Broek SA, Prins GW, Kuiken GD, Sixma JJ, Heethaar RM. Blood platelets are concentrated near the wall and red blood cells, in the center in flowing blood. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:819–824. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.AlMomani T, Udaykumar HS, Marshall JS, Chandran KB. Micro-scale dynamic simulation of erythrocyte-platelet interaction in blood flow. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2008;36:905–920. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9478-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee SY, Ferrari M, Decuzzi P. Shaping nano-/micro-particles for enhanced vascular interaction in laminar flows. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:495101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/49/495101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Decuzzi P, Ferrari M. The adhesive strength of non-spherical particles mediated by specific interactions. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5307–5314. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van de Ven AL, Kim P, Haley O, Fakhoury JR, Adriani G, Schmulen J, Moloney P, Hussain F, Ferrari M, Liu X, Yun SH, Decuzzi P. Rapid tumoritropic accumulation of systemically injected plateloid particles and their biodistribution. J. Control. Release. 2012;158:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adriani G, de Tullio MD, Ferrari M, Hussain F, Pascazio G, Liu X, Decuzzi P. The preferential targeting of the diseased microvasculature by disk-like particles. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5504–5513. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sevick EM, Jain RK. Viscous resistance to blood flow in solid tumors: effect of hematocrit on intratumor blood viscosity. Cancer Res. 1989;49:3513–3519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Decuzzi P, Godin B, Tanaka T, Lee SY, Chiappini C, Liu X, Ferrari M. Size and shape effects in the biodistribution of intravascularly injected particles. J. Control. Release. 2010;141:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Decuzzi P, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Ferrari M. Intravascular delivery of particulate systems: does geometry really matter? Pharm. Res. 2009;26:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9697-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wolfram J, Yang Y, Shen J, Moten A, Chen C, Shen H, Ferrari M, Zhao Y. The nano-plasma interface: Implications of the protein corona. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2014;124:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lundqvist M, Stigler J, Elia G, Lynch I, Cedervall T, Dawson KA. Nanoparticle size and surface properties determine the protein corona with possible implications for biological impacts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:14265–14270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Salvati A, Pitek AS, Monopoli MP, Prapainop K, Bombelli FB, Hristov DR, Kelly PM, Aberg C, Mahon E, Dawson KA. Transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles lose their targeting capabilities when a biomolecule corona adsorbs on the surface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013;8:137–143. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kirpotin DB, Drummond DC, Shao Y, Shalaby MR, Hong K, Nielsen UB, Marks JD, Benz CC, Park JW. Antibody targeting of long-circulating lipidic nanoparticles does not increase tumor localization but does increase internalization in animal models. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6732–6740. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cirstoiu-Hapca A, Buchegger F, Lange N, Bossy L, Gurny R, Delie F. Benefit of anti-HER2-coated paclitaxel-loaded immuno-nanoparticles in the treatment of disseminated ovarian cancer: Therapeutic efficacy and biodistribution in mice. J. Control. Release. 2010;144:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kwon IK, Lee SC, Han B, Park K. Analysis on the current status of targeted drug delivery to tumors. J. Control. Release. 2012;164:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:771–782. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Byrne JD, Betancourt T, Brannon-Peppas L. Active targeting schemes for nanoparticle systems in cancer therapeutics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008;60:1615–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brannon-Peppas L, Blanchette JO. Nanoparticle and targeted systems for cancer therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004;56:1649–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mann AP, Tanaka T, Somasunderam A, Liu X, Gorenstein DG, Ferrari M. E-selectin-targeted porous silicon particle for nanoparticle delivery to the bone marrow. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:H278–282. doi: 10.1002/adma.201101541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schweitzer KM, Drager AM, van der Valk P, Thijsen SF, Zevenbergen A, Theijsmeijer AP, van der Schoot CE, Langenhuijsen MM. Constitutive expression of E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 on endothelial cells of hematopoietic tissues. Am. J. Pathol. 1996;148:165–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kansas GS. Selectins and their ligands: current concepts and controversies. Blood. 1996;88:3259–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yokoi K, Godin B, Oborn CJ, Alexander JF, Liu X, Fidler IJ, Ferrari M. Porous silicon nanocarriers for dual targeting tumor associated endothelial cells and macrophages in stroma of orthotopic human pancreatic cancers. Cancer Lett. 2013;334:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ruoslahti E. Specialization of tumour vasculature. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:83– 90. doi: 10.1038/nrc724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ruoslahti E. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 1996;12:697–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]