Abstract

Tissue engineering is often referred to as a three-pronged discipline, with each prong corresponding to 1) a 3D material matrix (scaffold), 2) drugs that act on molecular signaling, and 3)regenerative living cells. Herein we focus on reviewing advances in controlled release of drugs from tissue engineering platforms. This review addresses advances in hydrogels and porous scaffolds that are synthesized from natural materials and synthetic polymers for the purposes of controlled release in tissue engineering. We pay special attention to efforts to reduce the burst release effect and to provide sustained and long-term release. Finally, novel approaches to controlled release are described, including devices that allow for pulsatile and sequential delivery. In addition to recent advances, limitations of current approaches and areas of further research are discussed.

Keywords: Tissue engineering, Scaffold, Biomaterials, Regenerative Medicine, Polymer, Controlled release, Drug delivery

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Tissue regeneration can be facilitated by the use of biomimetic materials that create a suitable microenvironment for the recruitment, adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of cells. This process can be further stimulated by the addition of drugs that have an influence on cellular function and tissue regeneration. For the purpose of this review, the term “drug” will be used to refer to small molecule chemicals, peptides, proteins, growth factors, cytokines, and other bioactive molecules used to support or stimulate cellular activities and new tissue regeneration.

Advanced tissue engineering systems often combine one or more of these three integral components: biomaterial matrices, living cells, and bioactive drugs. Researchers increasingly recognize the need for more spatiotemporal control over the release of drugs that directly or indirectly affect cellular signaling or tissue regeneration. Specifically, there is a growing desire to mimic the inherent complexity of natural tissue by delivering multiple drugs simultaneously, sequentially, or in multiphasic patterns. Researchers hypothesize that having fine control over the delivery of multiple stimuli over time will enhance the speed, quantity, and quality of tissue regeneration.

Tissue engineering scaffolds are being designed to serve as the 3D template and matrix microenvironment with respect to cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Incorporating a tunable drug delivery mechanism into such scaffolds may further stimulate the growth of new tissue and the repair of injury. Controlled drug delivery can be accomplished by physically or chemically adsorbing the drug onto the surface1 of the material matrix (scaffold), encapsulating the drug directly within the scaffold, or by incorporating drug delivery systems on the scaffold. The subsequent release of the drug occurs by diffusion or due to degradation of the scaffold or encapsulating material. The quantity and duration of drug released can be controlled by altering the composition of the material, the delivery system, or the methods of drug integration. Drug release kinetics and duration can further be tuned by changing the dose of the drug added or by coating the material with a substrate (e.g. heparin) that specifically or nonspecifically binds cells or drugs.

In tissue engineering, controlled release of drugs from a scaffold can accelerate the local regenerative process and circumvent the concerns over the potential undesired systemic effects of a drug in the body. Drugs must meet a minimum threshold to be effective, but due to their short half-lives in vivo, it is challenging to achieve a relevant dose at the site of injury for an extended period of time without causing unwanted side effects of over-exposure of cells and tissue that could occur when drugs are delivered systemically. Controlled release of drugs from tissue engineering scaffolds can help establish localized, clinically relevant drug concentrations for extended periods of time. The challenges in the field of controlled release lie in the ability to finely tune the release of the drug without negatively affecting the mechanical or structural properties of the scaffold and without damaging or quickly eluting the drug itself.2

A number of different types of materials have been employed to deliver drugs in a controlled manner, including porous materials and hydrogels made fromfrequently used natural and synthetic polymers. Composite materials that combine natural and synthetic materials or combine hydrogel and porous materials are also commonly used in controlled release.

The extent to which these new drug delivery systems have been tested varies from studies that only examine the basic biocompatibility, material characteristics and drug release kinetics, studies that evaluate the potential of drug delivery systems in vitro, and those that have been evaluated in vivo. These systems further differ based on whether they involve the delivery of a single drug, the simultaneous delivery of multiple drugs, the sequential delivery of multiple drugs, and the co-delivery of cells and single or multiple drugs.

This review examines the advances in controlled release of drugs for the purpose of tissue engineering, with an emphasis on recent studies within the past a few years. This article will cover advances in material synthesis that improve the ability to tune the release kinetics of drugs from various natural and synthetic material types, covering microspheres, hydrogels, porous scaffolds, nanofibrous scaffolds, and composite material systems. It will also describe scaffold surface modifications, strategies used to deliver multiple drugs and, and other novel advances. Finally, this review suggests areas in which additional research is needed to further the field of controlled release for tissue engineering.

2. Microspheres designed for controlled release

Microspheres and nanospheresare commonly used in controlled release of drugs across many clinical disciplines, including cancer treatment, infection control, inflammation control, and tissue regeneration. In tissue engineering, drugs are adsorbed to the surface of or encapsulated within the core of microspheres. Drug release from the microsphere matrix usually features a burst release associated with smaller quantities of drug attached to the surface of the microsphere, followed by a sustained release, which is associated with degradation of the polymer and release of encapsulated drug. Microspheres can be made from natural or synthetic polymers and can be made as hydrogels, solid, porous, and nanofibrous microspheres. PLGA and chitosan microspheres are frequently used for tunable drug delivery.3 When delivered in vivo, microspheres are sometimes susceptible to being cleared out of the animal and/or migrating away from the defect/implantation site. To maintain local treatment, microspheres are often combined with scaffolds or hydrogels in composite delivery systems. For this review, microspheres will be discussed in the context of their use in composite systems.

3. New hydrogel approaches that improve controlled release

Hydrogels are defined as a network of polymer chains that are hydrophilic by nature and swell in the presence of water. Increasing the crosslinking density between polymer chains or changing the polymer content can alter their physical characteristics and degradation rates, which in turn can affect their use in drug delivery. Hydrogels are attractive matrices for drug delivery and tissue engineering because they are easy to assemble from both natural and synthetic polymers and tend to be biocompatible. They are also adaptable to an injectable cell delivery system that is desirable to produce a minimally invasive treatment. However, hydrogel-based drug delivery systems usually exhibit a strong burst release of drug for a short period of time,4–6 from a few minutes up to 48 hours while total release of drugs from hydrogels may hardly extend beyond 1 week. Additionally, hydrogels are typically not adhesive for cells and proteins and they do not allow penetration by cells; instead hydrogel-based delivery systems require that cells be pre-loaded into the matrix prior to delivery. Due to these constraints, hydrogels are usually unsuitable for long-term controlled release. However, efforts are being made to adapt these materials to reduce the burst release effect and extend the length of time that a drug can be released from the material.

3.1 Efforts to reduce the burst release effect in hydrogels

The release of drugs from a hydrogel matrix occurs primarily through diffusion. A major effort in hydrogel drug delivery systems is to control the rate at which biomolecules are released from a hydrogel matrix. A conventional method for extending the duration and reducing burst effect from hydrogels is to increase the crosslinking density of the polymers. A matrix-metalloprotease (MMP)–sensitive hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel was made with varying degrees of crosslinking, which generally showed that gel degradation rate decreased as crosslink density increased.7

Effort has been made in controlling burst release through the development of a multifunctional interpenetrating polymer network.8 For example, hydrogels are synthesized from poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylate, N-isopropylacrylamide, and methacrylated alginate using ammonium persulfate and N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEDMED) as a redox initiator system. Alginate was chosen because its high number of carboxyl groups makes it sensitive to pH and therefore attractive for oral drug delivery. The redox initiator system was selected to overcome the limits of common photopolymerization methods that use a toxic photoinitiator or result in inconsistent drug delivery. These gels have been evaluated using model drugs for 24 hours at low pH (i.e., simulating gastric environment) and have not yet been tested for tissue engineering applications, which would likely require long-term sustained release.

Colloidal gelatin hydrogels assembled from oppositely charged gelatin nanospheres were used to deliver bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP-2) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). The release kinetics from this delivery system depends more on the crosslinking density of the gel than the type of gelatin used.9 When evaluated in vitro, gels with high crosslinking density showed a sustained release of growth factor from the gel over a 30-day period, while also showing a minimal burst effect in BMP-2 release. The release profile of bFGF showed a stronger burst effect. This study represented an attempt to co-deliver multiple growth factors with independent release rates using a colloidal gel. The in vivo analysis of this dual delivery system did not produce conclusive evidence of a synergistic effect and additional studies to optimize this co-delivery system are needed.

The self-assembling peptide nanofiber scaffold consisting of ionic self-complimentary peptides with 16 amino acids (RADA16) was tested as a slow release hydrogel.10 The release kinetics of five model drugs were studied using diffusion experiments in vitro and mathematical models. While slow release was accomplished, it was only measured for seven days. Additional studies on RADA16-I nanofiber scaffolds involved the release of active cytokines from the hydrogel and testing their activity in vitro. The release kinetics of bFGF, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) were tested by diffusion experiments; bFGF was subsequently released from the peptide scaffold in a neural stem cell (NSC) proliferation experiment. Significant stimulation of NSC proliferation was observed for up to three weeks.11 Peptide scaffolds were also used to deliver bFGF and growth differentiation factor-5 (GDF-5) for in vivo treatment of medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury.12

3.2 Composite hydrogel – microsphere delivery systems used to deliver multiple GFs

Due to the challenges in altering the physical characteristics of hydrogels themselves to extend and control the release rate of drugs, researchers have turned to first encapsulating or adsorbing drugs in polymeric microspheres before incorporating them into the gel matrix. In these systems, the microspheres serve to control the release of the drug while the hydrogel is primarily a scaffold to retain cells in a 3D structure.

Early work using this approach involved the encapsulation of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) in poly(d, l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres and then loading these drug-containing microspheres into poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO)-based hydrogels.13 In this cartilage tissue engineering study, two growth factors were released over 15 days, stimulating chondrocyte proliferation in vitro. This study set an early example for the potential of hydrogel-microsphere composite delivery systems but also highlighted the challenges of adapting these systems to tissue engineering, including the need for dose control, loading efficiency, and optimizing growth factor release characteristics.

In a similar approach, researchers encapsulated IGF-1 and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in PLGA microspheres and integrated these microspheres along with human adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) into a hydrogel made of a tri-block copolymer of polypropylene glycol and polyethylene glycol for cardiac tissue engineering.14 The encapsulation of growth factors into microspheres muted the burst release and allowed for a sustained release over 21 days. The release of growth factors from the PLGA microspheres was attributed to the slow degradation of the polymer over time.

A more recent study used the same principle to deliver bFGF and BMP-7 loaded in chitosan (CS) nanoparticles in a gellan xanthan gel matrix. This study showed significant improvements in alkaline phosphatase activity and calcium deposition when compared to single growth factor delivery, suggesting that the dual delivery of growth factors supported better osteogenic differentiation.15 The release kinetics over 21 days showed a burst release on the first day for the hydrogel-microsphere system but demonstrated a more sustained release of BMP-7 thereafter.

These studies represent dual growth factor release from composite hydrogel systems that reduce the burst release typically associated with hydrogels, enhancing the regeneration of various tissue types. These systems are worth to be further evaluated in vivo, and efforts are needed to achieve distinct release kinetics for each factor when dual or multiple release is involved.

4. Porous scaffolds made of natural materials with controlled release capacity

Porous scaffolds are solid, three-dimensional physical structures with a porous architecture that allows infiltration, attachment, and proliferation of cells and tissue regeneration. A number of natural polymer materials have been employed as porous scaffolds for controlled release of drugs for the purposes of tissue regeneration. These include hyaluronic acid (HA), chitosan, alginate, collagen, fibrin, and others. These natural materials offer some potential advantages for tissue engineering. For example, collagen makes up a major portion of the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) of bone and other structural tissues and is therefore an attractive scaffolding material for tissue regeneration. Many efforts to use natural materials for controlled release in the form of hydrogels, as previously discussed, and porous scaffolds/microparticles are ongoing. One approach is to modify the surface of natural polymers with affinitive substrates, such as heparin, that can help control the release of drugs from the scaffold.

4.1 Reducing burst release effect

Similar to hydrogel-based delivery, there is a perceived need to reduce the burst effect and extend the length of time natural materials can be used to deliver drugs in a spatiotemporally controlled manner.

To better control the release of TGF-β3 for chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells, researchers used hollow hyaluronan (HA) microspheres prepared by a previously described method involving the removal of a polystyrene core. TGF-β3 was incorporated into the microspheres by diffusion loading.16 These HA microspheres were compared to collagen microspheres for in vitro chondrogenic differentiation. The release kinetics of the HA microspheres showed a 20% burst release on the first day followed by sustained release over 6 days. The in vitro results showed positive markers for chondrogenesis, as suggested bysignificant increases in collagen II and aggrecan expression as well as a significant decrease of collagen X expression. The authors argue that the burst release is advantageous to this application due to the need for early commitment of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) during chondrogenic differentiation. This system may be suitable for chondrogenic regeneration but remains to be evaluated for its potential for long-term release and for regeneration of other tissue types.

4.2 Sustaining release for extended treatment time period

Long-term sustained release of dexamethasone from CS nanoparticles for osteogenic differentiation was achieved when the nanoparticles were synthesized using a microfluidic device.17 Despite a moderate burst release, sustained intracellular delivery of dexamethasone was observed for up to 21 days. Significant increases in ALP activity, osteocalcin expression, and calcium deposition were observed.

Sustained long-term release of recombinant human BMP-2 (rhBMP-2) was achieved from a collagen-hydroxyapatite scaffold for 21 days. In this bone tissue regeneration study, the burst release was controlled to a minor burst in the first four hours, followed by sustained release for 21 days.18 After 7 days, the controlled release system significantly increased ALP activity and after 14 days showed significantly higher calcium concentration when cultured with MC3T3 cells. An 8-week in vivo implantation of the scaffold in a rat calvarial defect showed improved healing when compared to scaffold only (no drug) or empty defect control, with significantly greater area of new bone formed when measured by quantitative histomorphometric analysis.

While natural scaffolds offer certain advantages, they also have some specific drawbacks. In particular, natural polymers are subject to inconsistent degradation rates and many of them have limited mechanical strength.19 Natural scaffolds sometimes lead to unwanted host inflammatory responses, although ways to harness and/or reduce the inflammatory responses caused by natural materials are being studied.20–23 Alternatively, synthetic materials may overcomesome of these limitations in natural materials.

5. Synthetic polymer scaffolds allow for precise control of release kinetics

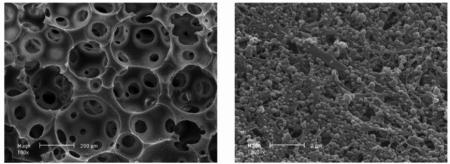

As alternatives to natural scaffolds, researchers sought to create novel synthetic polymer scaffolds that could provide the 3D microenvironment for tissue engineering while overcoming issues such as low mechanical strength and variable degradation rates.24 Many synthetic polymers, each with different structural, biological, and mechanical characteristics, have been used for this purpose. The most commonly used synthetic polymers include PLLA, poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), PLGA, and poly(caprolactone) (PCL). Scaffolds made from these polymers form porous structures. The size of macro-pores and the interporeconnectivity of the 3D structure affect the surface area and therefore the drug release kinetics. Furthermore, the porosity and interporeconnectivity affect the ability of cells to penetrate and proliferate in and on the surface of the scaffold (Figure 1A&B).25

Figure 1.

SEM images of Solid Walled (SW)-PLLA and NF-PLLA scaffolds. (A) Macroporous structure of SW-PLLA scaffolds at low magnification; (B) Solid-walled architecture of SW-PLLA scaffolds at high magnification; (C) Macroporous structure of NF-PLLA scaffolds at low magnification; and (D) Nanofibrous architecture of NF-PLLA scaffolds at high magnification.

Reprinted from Biomaterials, 32(31), Jing Wang, Haiyun Ma, Xiaobing Jin, et al. The effect of scaffold architecture on odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells. 7822–7830. (2011) with permission from Elsevier.

These synthetic polymers and copolymers are used in tissue engineering and controlled release through three methods. When drugs are incorporated into matrix of the scaffold, degradation of the polymer dictates release kinetics of the drug. The scaffold walls are impregnated with drug and as the polymer degrades, drug is released. When scaffold surfaces are coated with polymer/drug layer, the release is controlled by diffusion and degradation of the coating polymer.26 The integration of microspheres into scaffolds offer a third mechanism to control the release of drugs in tissue engineering applications similar to the composite hydrogel-microsphere delivery systems. Approaches include, for example, the delivery of model drugs from a synthetic composite scaffold using polystyrene microspheres27or the delivery of FGF-2 encapsulated gelatin microspheres that are seeded onto a PCL-PLLA scaffold to support osteoblast proliferation and adhesion.28

5.1 Polymer scaffolds and microspheres with nanofibrous architecture

Synthetic polymer porous scaffolds and microspheres with nanofibrous(NF) architecture have gained increased popularity for the purposes of tissue engineering because theycreate a 3D microenvironment similar to the nanofibrouscollagen found in extracellular matrix of native tissue.29 While solid walled porous scaffold have been studied for controlled release, there is evidence that nanofibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering are superior due to their biomimetic architecture.25,30 Several excellent review articles cover the methods used to synthesize NF scaffolds and their applications for drug delivery in tissue engineering.2,31–38 In short, there are three major methods to synthesize NF scaffolds including self-assembly, electrospinning, and thermally induced phase separation. Controlled release can be accomplished by the same three methods as nonnanofibrous scaffolds. The technique of electrospinning allows researchers to directionally align fibers, which are otherwise randomly oriented. Alignment of nanofibers is advantageous for neural39 or vascular tissue regeneration.

Nanofibrous scaffolds made from natural materials40–42 or synthetic/natural blends have also been developed. A NF scaffold made from a PLLA-PCL and silk fibroin composite was used to deliver curcumin for skin regeneration.43 VEGF was delivered from a NF scaffold made from a PLLA-PCL and gelatin blend for cardiac tissue regeneration.44 A blend of PCL and gelatin was used to delivery antibiotic for bone regeneration.45 A core sheath PCL and silk fibroin blend was investigated in vitro for delivery of model drugs and shows potential for tissue engineering and drug delivery.46

5.2 Composite scaffold-microsphere delivery systems

PLGA microspheres and nanospheres (NS) have been used frequently as drug and cell carriers47. Distinct release profiles can be achieved by changing the lactic acid (LA) to glycolic acid (GA) ratio or altering the molecular weight of the polymers. Microspheres have also been used in combination with 3D scaffolds to modulate the microenvironment through drug release. An NF PLLA scaffold could be seeded with microspheres encapsulating platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)48 or nanospheres encapsulating rhBMP-749. In these two studies, the NF scaffold-micro/nanosphere combination demonstrated the in vivo capability of this system to promote soft tissue and hard tissue regeneration.

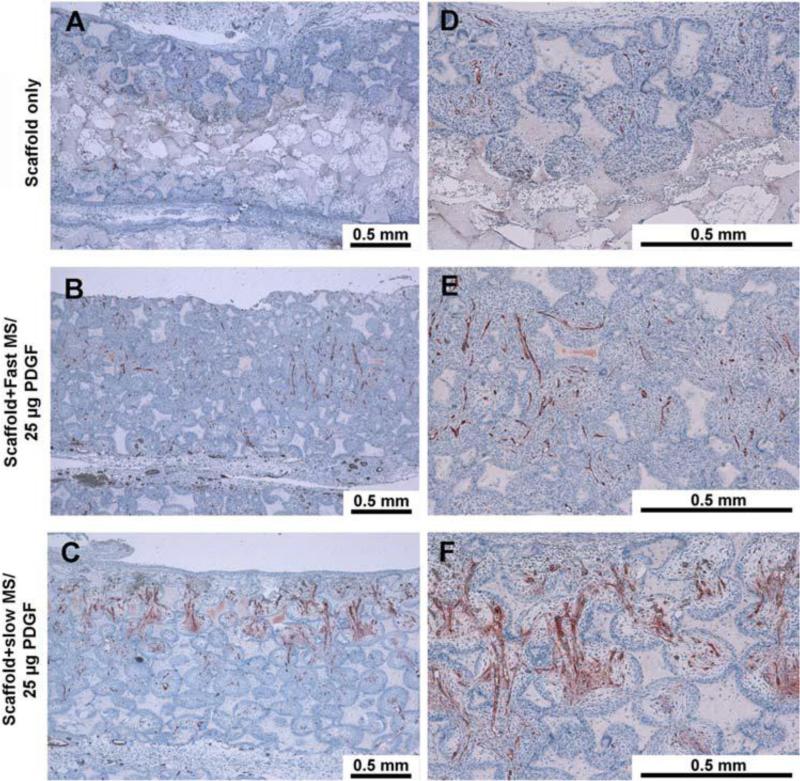

PLGA microspheres with varying molecular weights were fabricated using established double emulsion techniques. Doses ranging from 2.5μg to 25μg of PDGF were encapsulated in the microspheres and immobilized onto the NF scaffold, which was subcutaneously implanted in a rat wound model. The in vivo performance was measured at 3, 7, 14, and 21 days.50 The higher molecular weight microspheres were associated with a longer-term release of rhPDGF-BB and showed enhanced cell migration and vasculogenesis (Figure 2).51 Enhanced expression of several chemokines was found to be behind such effects.

Figure 2.

Nanofibrous scaffolds with PDGF microspheres promote vasculogenesis in vivo. Left panel is low magnification (10X), right panel is high magnification (40X). Positive Factor VIII stained blood vessels were located in the central regions of the pores within penetrated tissues. The blood vessels also permeated through the inter-openings between each pore. The group with 25 mg PDGF encapsulated in slow release PLGA microspheres had measurably more vascularization.

Reprinted from PLoS One, 3(3), Qiming Jin, Guabao Wei, Zhao Lin, et. al. Nanofibrous Scaffolds Incorporating PDGF-BB Microspheres Induce Chemokine Expression and Tissue Neogenesis In Vivo. e1729 (2008), under Creative Commons Attribution license

Nanospheres with an average diameter around 300nm were prepared using the double emulsion technique. The release of rhBMP-7 from nanospheres immobilized onto an NF scaffold (Figure 3) was evaluated for bone regeneration in a subcutaneous implantation rat model.49 The incorporation of rhBMP-7 nanospheres significantly increased new bone formation at 3 weeks and 6 weeks after implantation. At 6 weeks, the NF scaffold/rhBMP-7 nanosphere complex generated more tissue than a scaffold with directly adsorbed rhBMP-7 based on radiographic analysis. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and von Kossa staining confirmed the superior bone regeneration of the composite scaffold-nanosphere complex to control scaffolds. The in vitro release kinetics showed a moderate burst release followed by sustained release for more than 70 days. Delivery of the antibiotic drug doxycycline was also achieved by a NF scaffold-nanosphere composite system.52 Antibiotic delivery may play an important role in tissue regeneration as to protect the site of injury from infection. This combination of NF PLLA scaffolds and PLGA micro/nanospheres offers long-term delivery not attainable by other approaches. This controlled release system has the unique abilities to moderate the burst release, extend the treatment time, and provide a superior 3D microenvironment for tissue engineering.

Figure 3.

Characterization of PLGA50–64K nanospheres (NS) and nanosphere incorporated PLLA nano-fibrous scaffolds (NS-scaffolds). (A) Scanning electron micrograph of rhBMP-7 containing PLGA50–64K nanospheres; (B) Macroscopic photographs of PLLA scaffolds before (left) and after (right) nanosphere incorporation; (C, D) Scanning electron micrographs of PLLA nano-fibrous scaffolds before nanosphere incorporation at 100× (C) and 10,000× (D); (E, F) Scanning electron micrographs of PLLA nano-fibrous scaffolds after PLGA50–64K nanosphere incorporation at 100× (E) and 10,000× (F).

Reprinted from Biomaterials, 28 (12), Guobao Wei, Qiming Jin, William V. Giannobile, Peter X. Ma The enhancement of osteogenesis by nano-fibrous scaffolds incorporating rhBMP-7 nanospheres. 2087-2096. (2007) with permission from Elsevier.

6. Modifications to controlled release polymers

One common approach to changing the release kinetics of scaffold-based delivery systems is to modify the surface of the material with a substrate that binds selectively or non-selectively with drugs and other bioactive molecules. Surface modification has been used in tissue engineering approaches generally to improve the hydrophilicity, mechanical properties, and biocompatibility of a polymer scaffold. Biocompatibility is improved by increasing the ability of cells to attach, spread, proliferate, and differentiate throughout the scaffold. Frequently used surface modifiers include extracellular matrix proteins or peptides such as collagen53–55, fibronectin,56 laminin56, and gelatin54,57. Growth factors58, synthetic chemicals59, and compounds such as graphene60 have also been used to modify the surface of a scaffold matrix. Various peptides61–63, often short amino acid sequences of ECM proteins, are also used to increase biocompatibility of scaffold surfaces. Other approaches such as argon plasma64, phosphonate groups65, or cold atmospheric plasma66 modifications have also improved adhesion and cellular infiltration and proliferation on scaffolds.

While these modifications aid in improving biocompatibility of scaffold for regeneration of various tissue types, few actually have been designed to improve controlled release of drugs. In one case, modification of a PLGA scaffold with 2-N, 6-O sulfated chitosan increased adsorption of rhBMP-2 onto the scaffold and prolonged its release.67 In another example, bFGF modification of a PCL nanofibrous matrix increased cellular proliferation and attachment, and bFGF was also released over two weeks from a scaffold mineralized with hydroxyapatite and a non-mineralized scaffold.58

The addition of substrates with affinity to specific drugs, such as heparin, may help reduce the burst effect and extend and sustain drug release from a polymer scaffold.68

6.1 Heparin based delivery systems with natural scaffold materials

Heparin is a glycosaminoglycan (GAG) known to specifically bind with many enzymes, cytokines, growth factors (including bFGF and VEGF), and other proteins. It is a highly sulfated and a highly anionic linear polysaccharide69 that has varying levels of binding affinity for peptides and proteins. Controlled release of a drug from a heparin based delivery system (HBDS) is dependent on the heparin binding affinity of the drug being released. Researchers developed porous scaffolds made from collagen/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite, which were then modified with heparin and used to deliver VEGF for bone tissue engineering.69 Using an in situ or a post scaffold fabrication modification approach, heparin was incorporated into the scaffold matrix or coated the scaffold surface. VEGF was loaded onto the heparin-modified scaffolds by physical adsorption. Varying amounts of heparin were incorporated into scaffolds and each was tested in an in vitro cell proliferation study. The release kinetics of the growth factor from the scaffold was examined for 7 days and showed a reduction in burst release for scaffolds with both types of heparin modification. However, growth factor bioactivity was reduced in comparison to control levels. This study showed improved cell proliferation in the scaffolds prepared with heparin in situ but differentiation studies may further determine the potential of this approach. Furthermore, in vivo testing and long-term release experiments have yet to be undertaken.

A heparin-containing fibrin-based matrix was developed to deliver nerve growth factor in a controlled manner, as the authors hypothesized that providing a high molar excess of heparin sites would slow diffusion-based growth factor release.70 Release experiments and in vitro cellular assays conducted over 15 days showed a burst release followed by sustained release of growth factor. Neurite extension was observed in the dorsal root ganglia studies in response to the biphasic release.

Heparin has also been used in combination with fibrin to deliver TGF-β3 in an in vivo tendon-to-bone healing model.71 The in vitro release studies showed that the incorporation of the HBDS into the fibrin matrix reduced the burst release showed potential for sustained, long-term release. The delivery system was evaluated in vivo using a rat model up to 56 days. While growth factor delivery led to significant improvements in mechanical and structural properties, scar tissue reduction was not observed. Further optimization of this delivery system and increased understanding of the in vivo release kinetics are needed.

6.2 Other affinity-based controlled release systems

Heparin is frequently used to functionalize a 3D matrix for controlled release because it has affinity to many proteins. In addition to the use of heparin as a surface modifier, hydrogels and scaffold have been modified in several other ways to achieve affinity-based controlled release. These examples are covered in more detail in recent reviews of affinity-based delivery systems72,73, and include use of cyclodextrins, DNA aptamers, protein-protein interactions, ionic interactions, and others. Cyclodextrins, which are cyclic oligosaccharides, can be fabricated as hydrogels or can be used to coat devices, scaffolds, or prostheses. They have been effectively applied to deliver antibiotics while reducing burst effect and extending length of treatment.74 DNA aptamers are single stranded oligonucleotides that have high affinity for specific targets. They have been used to deliver PDGF-BB for up to 25 days in modified composite hydrogel-microparticle delivery system75 and both PDGF-BB and VEGF in a functionalized polystyrene microparticles for 10 days.76 Protein-protein interactions take advantage of peptides with specific affinity to growth factors in delivery systems to help control their release. For example, a PEG hydrogel was modified with various peptides to modulate and tune the release of bFGF for more than 30 days.77 Similarly, a peptide derived from the VEGF receptor was used to modify PEG hydrogel microspheres and regulate VEGF delivery for up to 30 days.78

7. Other novel/unique approaches to controlled release

Other approaches to controlled release are being explored for various tissue engineering applications. The spatiotemporal control of drug delivery is governed by the individual needs of a specific tissue type or mechanism of action of a drug. For example, the pulsatile treatment of parathyroid hormone (PTH) stimulates osteogenesis while a sustained delivery of the same hormone results in resorption of existing bone.79 As previously mentioned, some tissue engineering systems take advantage of a burst release to deliver a higher dose of a drug that promotes early cell differentiation. A number of highly specialized drug delivery systems are therefore being developed and some of these are highlighted below.

7.1 Multiphasic devices allow pulsatile or sequential delivery

A multi phasic device physically separates a bioactive molecule with a material film and allows the sustained, pulsatile delivery of a drug over an extended period of time. Pulsatile release of PTH is achieved in a device made of polyanhydride isolation layers and PTH-loaded alginate drug layers in a PLLA cylinder.80 Four sequential doses of PTH were released with 24 hours of separation between each pulse. This delivery system offers the additional flexibility to deliver multiple drugs and additional studies that incorporate this device into a scaffold for in vitro and in vivo tissue regeneration are ongoing.

In another approach, researchers used multilayered self-assembled polymer-based biomimetic implant to deliver rhBMP-2 and gentamicin for healing bone defects and for treatment of orthopedic implant surfaces.81 This device takes advantage of a laponite clay barrier between drug layers that prevents inter layer diffusion and allows for sustained release. In this system, antibiotic is released early in the treatment, while rhBMP-2 is released for up to 55 days. The system showed positive antibacterial activity and increased ALP activity over a 5-week study. Testing of this device in vivo and incorporation of different drugs and growth factors are needed to demonstrate the value of this approach. The addition of more layers may increase concern about the size of the device for surgical implantation.

In wound dressing, regeneration of epidermal tissue is stimulated by exposure to growth factors or other bioactive agents. A multilayered hydrogel was designed82,83 with an internal layer comprised of a gelatin and hyaluronic acid film crosslinked with genipin and loaded with proadrenomedullin N-terminal 20 peptide(PAMP), which is a natural peptide that has a proangiogenic and antimicrobial effect. An external layer comprised of biodegradable polyurethane was loaded with nanoparticles of bemiparin, which promotes the activation of VEGF and fibroblast growth factor (FGF). The internal layer slowly releases PAMP andthe external layer provides mechanical stability and releases bemiparin. This device was tested in two in vivo models for 14 days and produced promising results.

7.2 Magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer controlled release systems

Molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) nanoparticles are created with binding sites that have specific affinity for a target molecule. Magnetic MIPs, or MMIPs, are made by a new technique that involves encapsulating an inorganic magnetic particle with molecularly imprinted polymers. MIPs have unique chemical and physical properties, including large surface area, which make them useful for drug delivery. The introduction of an inorganic magnetic particle helps resolve inefficiencies and reduce the time in separating MIPs from solution.84 A new method of synthesizing MMIPs involves the use of a cross-linker N,N –bismethacryloylethylenediamine, which was used to prepare nanoparticles that could deliver meloxicam, a non steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, in a controlled manner. During in vitro release testing, MMIPs were exposed to simulated gastric, intestinal, and biological fluids by varying pH from 1 to 6.8 to 7.4, respectively. The release experiments were carried out for 36 hours and showed a burst release in the first 5 hours followed by a sustained release for the remainder of the experiment in gastric and intestinal simulated fluids. At a biological pH of 7.4, the burst release extended to the first 10 hours and was followed by a sustained release for up to 40 hours. This novel material may prove to be useful but release times must be extended and additional in vivo release studies are needed.

8. Areas of need for improving controlled release platforms

8.1 Sequential or simultaneous delivery of multiple drugs

The complex tissues and even a single tissue are often responsive to multiple factors at different points in time. Much of what we know about new tissue formation is learned from our understanding of pre-natal and post-natal tissue growth and formation. It is becoming increasingly clear that the ability to finely control the release of drugs and growth factors from 3D scaffolds can enhance tissue engineering and reduce healing time of injury and defects. Sequential delivery of two drugs has been explored using scaffolds, composite scaffold/hydrogel-microsphere systems, core-shell polymer matrices, and hydrogels. Several studies have examined the effect of sequential delivery of VEGF followed by PDGF for vascular tissue regeneration, including those designed to recover heart function following myocardial infarction.85–90 Other drug combinations have also been explored for sequential delivery in vascular tissue engineering.91–94 Additional systems have been designed to sequentially deliver BMPs, simvastatin, FGFs, VEGF, and other drugs in different combinations for bone/dental tissue regeneration.95–107 Few sequential delivery systems have been designed that target regeneration of other tissue types, such as neural tissue108,109 or cartilage110. Some sequential delivery systems have only been tested using model proteins or drugs.111,112 Multiphasic delivery of drugs from composite polymer systems49,113–120 allow for the delivery of more than two drugs121 or two doses of a drug. These devices can be designed as core-shell structures or multilayered devices in which drugs are separated by barrier layers.

For sequential delivery systems, considerable work has been done in the areas of vascular and bone tissue engineering. While the combination of PDGF-BB and VEGF shows promise, additional drug combinations may also enhance vascular tissue regeneration. Similarly, many combinations of drugs have been used for sequential delivery, but no single combination of drug, dose, and temporal delivery has been identified as superior to others. Optimization of these systems is needed, as is the ability to deliver more than two drugs. As controlled release systems increase in complexity, optimization of these systems will be challenging. Understanding the underlying mechanisms by which drug combination act over time is important to optimizing delivery systems. Improvements in the ability to control the temporal delivery of drugs will improve the ongoing research that supports multiple growth factor/drug release.

The types and combinations of materials used for controlled release in tissue engineering are numerous. However, many still lack the ability to extend release of drugs past 1 or 2 weeks. Surface modifications and functionalization of delivery systems provide a means for extending treatment. Heparin-based systems are most commonly used, but newer approaches have been developed. Most of these systems, however, have only been designed and evaluated for the delivery of a single drug.

Determining in vitro release kinetics is insufficient in understanding the effects of drugs released from a scaffold in vivo. Few studies, if any, examine the in vivo release kinetics, which are important to understanding the spatiotemporal control that a delivery system has. Furthermore, additional studies are needed to evaluate tissue engineering constructs with in vivo defect models. While subcutaneous implantation models provide useful data, fewer studies have tested the viability of healing injuries or critical defects within the appropriate in vivo microenvironment. Given the limitations of small animal models, studies involving large animals and human clinical trials are important to optimization of scaffolds and devices. These areas of focus are needed in future in vivo controlled release studies.

9. Conclusion and perspectives

Controlled release for tissue engineering is a growing field that is seeking new ways to improve the 3D microenvironment provided by material scaffolds and to stimulate molecular signaling of cells within these microenvironments. Increased understanding of molecular signaling is being used to develop delivery systems that finely control the spatiotemporal release of multiple drugs and enhance new tissue growth. New materials and new combinations of materials are being synthesized to achieve different release kinetics that better support regeneration of various tissue types. Material combinations, for example those that combine nanofibrous matrices with micro/nanospheres is intended to offer the control factor release and 3D microenvironment suitable for tissue engineering.

Clinical applications for these new controlled release systems are being developed across many tissue types, including bone, cartilage, blood vessels, epidermal, cardiac, neural, and others. Porous scaffolds and hydrogels are also amenable to the development of patient-specific regenerative treatment sutilizing the potential of induced pluri potent stem cells (iPSCs).122 Advances on all three fronts of tissue engineering – material matrix design, drug delivery, and regenerative cells – will help to push the field into clinical use in the near future.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the NIH (NIDCR DE022327, DE015384, and NHLBI HL114038: PXM), DOD (W81XWH-12-2-0008: PXM) and NSF (DMR-1206575).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Motamedian SR, Hosseinpour S, Ahsaie MG, Khojasteh A. Smart scaffolds in bone tissue engineering : A systematic review of literature. World J Stem Cells. 2015;7(3):657–668. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i3.657. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v7.i3.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu J, Ma PX. Nano-fibrous tissue engineering scaffolds capable of growth factor delivery. Pharm Res. 2011;28(6):1273–1281. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0367-z. doi:10.1007/s11095-011-0367-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma G. Microencapsulation of protein drugs for drug delivery: strategy, preparation, and applications. J Control Release. 2014;193:324–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.09.003. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Xu L, Liu H, et al. Biomimetic synthesized nanoporous silica@poly(ethyleneimine)s xerogel as drug carrier: Characteristics and controlled release effect. Int J Pharm. 2014;467:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.03.045. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulyasasmita W, Cai L, Dewi RE, et al. Avidity-controlled hydrogels for injectable co-delivery of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells and growth factors. J Control Release. 2014;191:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.015. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montiel-Herrera M, Gandini A, Goycoolea FM, et al. N-(furfural) chitosan hydrogels based on Diels–Alder cycloadditions and application as microspheres for controlled drug release. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;128:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.03.052. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holloway JL, Ma H, Rai R, Burdick JA. Modulating hydrogel crosslink density and degradation to control bone morphogenetic protein delivery and in vivo bone formation. J Control Release. 2014;191:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.053. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao J, Zhao X, Guo B, Ma PX. Multi-functional Interpenetrating Polymer Network Hydrogels Based on Methacrylated Alginate for Delivery of Small Molecule Drugs and Sustained Protein Release. Biomacromolecules. 2014 doi: 10.1021/bm5006257. doi:10.1021/bm5006257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Zou Q, Boerman OC, et al. Combined delivery of BMP-2 and bFGF from nanostructured colloidal gelatin gels and its effect on bone regeneration in vivo. J Control Release. 2013;166(2):172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.12.015. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagai Y, Unsworth LD, Koutsopoulos S, Zhang S. Slow release of molecules in self-assembling peptide nanofiber scaffold. J Control Release. 2006;115:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.031. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelain F, Unsworth LD, Zhang S. Slow and sustained release of active cytokines from self-assembling peptide scaffolds. J Control Release. 2010;145(3):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.026. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saiga K, Furumatsu T, Yoshida A, Masuda S, Takihira S, Abe N. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications Combined use of bFGF and GDF-5 enhances the healing of medial collateral ligament injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;402(2):329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.026. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elisseeff J, Mcintosh W, Fu K, et al. Controlled-release of IGF-I and TGF-P 1 in a photopolymerizing hydrogel for cartilage tissue engineering. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:1098–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karam J-P, Muscari C, Sindji L, et al. Pharmacologically active microcarriers associated with thermosensitive hydrogel as a growth factor releasing biomimetic 3D scaffold for cardiac tissue-engineering. J Control Release. 2014;192:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.052. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyondi D, Webster TJ, Banerjee R. A nanoparticulate injectable hydrogel as a tissue engineering scaffold for multiple growth factor delivery for bone regeneration. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;8:47–59. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S37953. doi:10.2147/IJN.S37953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ansboro S, Hayes JS, Barron V, et al. A chondromimetic microsphere for in situ spatially controlled chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Control Release. 2014;179:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.01.023. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasani-Sadrabadi MM, Hajrezaei SP, Emami SH, et al. Enhanced osteogenic differentiation of stem cells via microfluidics synthesized nanoparticles. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol Med. 2015:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.04.005. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinlan E, Thompson EM, Matsiko A, Brien FJO, López-noriega A. Long-term controlled delivery of rhBMP-2 from collagen – hydroxyapatite scaffolds for superior bone tissue regeneration. J Control Release. 2015;207:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.028. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raftery R, O'Brien FJ, Cryan SA. Chitosan for gene delivery and orthopedic tissue engineering applications. Molecules. 2013;18(5):5611–5647. doi: 10.3390/molecules18055611. doi:10.3390/molecules18055611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos TC, Hoering B, Reise K, et al. In vivo performance of chitosan/soy-based membranes as wound dressing devices for acute skin wounds. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;19(7-8):860–869. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0651. doi:10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahmanian-Schwarz A, Held M, Knoeller T, et al. In vivo biocompatibility and biodegradation of a novel thin and mechanically stable collagen scaffold. J Biomed Mater Res - Part A. 2014;102(4):1173–1179. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34793. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.34793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daneshmandi S, Dibazar SP, Fateh S. Effects of 3-dimensional culture conditions (collagen-chitosan nano-scaffolds) on maturation of dendritic cells and their capacity to interact with T-lymphocytes. J Immunotoxicol. 2015:1–8. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2015.1045636. doi:10.3109/1547691X.2015.1045636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desai RM, Koshy ST, Hilderbrand SA, Mooney DJ, Joshi NS. Versatile click alginate hydrogels crosslinked via tetrazine–norbornene chemistry. Biomaterials. 2015;50:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.048. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(1):47–55. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. doi:10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Ma H, Jin X, et al. The effect of scaffold architecture on odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells. Biomaterials. 2011;32(31):7822–7830. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.034. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.021.Secreted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu Y, Chen J, Chen R, et al. Enhancement of VEGF-Mediated Angiogenesis by 2-N, 6-O-Sulfated Chitosan-Coated Hierarchical PLGA Scaffolds. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:9982–9990. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b02324. doi:10.1021/acsami.5b02324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ionescu LC, Lee GC, Sennett BJ, Burdick JA, Mauck RL. An anisotropic nanofiber/microsphere composite with controlled release of biomolecules for fibrous tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31(14):4113–4120. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.098. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gungor-Ozkerim PS, Balkan T, Kose GT, Sarac AS, Kok FN. Incorporation of growth factor loaded microspheres into polymeric electrospun nanofibers for tissue engineering applications. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102(6):1897–1908. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34857. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.34857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei G, Ma PX. Partially nanofibrous architecture of 3D tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2009;30(32):6426–6434. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.012. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng G, Jin X, Hu J, et al. Effects of hypoxias and scaffold architecture on rabbit mesenchymal stem cell differentiation towards a nucleus pulposus-like phenotype. Biomaterials. 2011;32(32):8182–8189. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.049. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma PX. Biomimetic Materials for Tissue Engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60(2):184–198. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.041. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, Hu J, Ma PX. Nanofiber-based delivery of bioactive agents and stem cells to bone sites. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64(12):1129–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.008. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.008.Nanofiber-based. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupte MJ, Ma PX. Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Dental and Craniofacial Applications. J Dent Res. 2012;91(3):227–234. doi: 10.1177/0022034511417441. doi:10.1177/0022034511417441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji W, Sun Y, Yang F, Jeroen JJP. Bioactive Electrospun Scaffolds Delivering Growth Factors and Genes for Tissue Engineering Applications. Pharm Res. 2011;28:1259–1272. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0320-6. doi:10.1007/s11095-010-0320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelipenko J, Kocbek P, Kristl J. Critical attributes of nanofibers : Preparation, drug loading, and tissue regeneration. Int J Pharm. 2015;484(1-2):57–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.02.043. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amler E, Filova E, Buzgo M, et al. Functionalized nanofibers as drug-delivery systems for osteochondral regeneration. Nanomedicine. 2014;9(7):1083–1094. doi: 10.2217/nnm.14.57. doi:10.2217/nnm.14.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joshi J, Kothapalli CR. Nanofibers based tissue engineering and drug delivery approaches for myocardial regeneration. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21(15):2006–2020. doi: 10.2174/1381612821666150302153138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puppi D, Zhang X, Yang L, Chiellini F, Sun X, Chiellini E. Nano/microfibrous polymeric constructs loaded with bioactive agents and designed for tissue engineering applications: a review. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2014;102(7):1562–1579. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33144. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.33144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mu Y, Wu F, Lu Y, Wei L, Yuan W. Progress of electrospun fibers as nerve conduits for neural tissue repair. Nanomedicine. 2014;9(12):1869–1883. doi: 10.2217/nnm.14.70. doi:10.2217/nnm.14.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sridhar R, Lakshminarayanan R, Madhaiyan K, Amutha Barathi V, Lim KHC, Ramakrishna S. Electrosprayed nanoparticles and electrospun nanofibers based on natural materials: applications in tissue regeneration, drug delivery and pharmaceuticals. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(3):790–814. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00226a. doi:10.1039/c4cs00226a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montero RB, Vial X, Nguyen DT, et al. bFGF-containing electrospun gelatin scaffolds with controlled nano-architectural features for directed angiogenesis. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(5):1778–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.12.008. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lai H-J, Kuan C-H, Wu H-C, et al. Tailored design of electrospun composite nanofibers with staged release of multiple angiogenic growth factors for chronic wound healing. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(10):4156–4166. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.05.001. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gandhimathi C, Venugopal JR, Bhaarathy V, Ramakrishna S, Kumar SD. Biocomposite nanofibrous strategies for the controlled release of biomolecules for skin tissue regeneration. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:4709–4722. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S65335. doi:10.2147/IJN.S65335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tian L, Prabhakaran MP, Ding X, Kai D, Ramakrishna S. Emulsion electrospun vascular endothelial growth factor encapsulated poly(l-lactic acid-co-ε-caprolactone) nanofibers for sustained release in cardiac tissue engineering. J Mater Sci. 2011;47(7):3272–3281. doi:10.1007/s10853-011-6166-4. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xue J, He M, Liu H, et al. Drug loaded homogeneous electrospun PCL/gelatin hybrid nanofiber structures for anti-infective tissue regeneration membranes. Biomaterials. 2014;35(34):9395–9405. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.060. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li L, Li H, Qian Y, et al. Electrospun poly (varepsilon-caprolactone)/silk fibroin core-sheath nanofibers and their potential applications in tissue engineering and drug release. Int J Biol Macromol. 2011;49(2):223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.04.018. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu X, Jin X, Ma PX. Nanofibrous hollow microspheres self-assembled from star-shaped polymers as injectable cell carriers for knee repair. Nat Mater. 2011;10(5):398–406. doi: 10.1038/nmat2999. doi:10.1038/nmat2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei G, Jin Q, Giannobile WV, Ma PX. Nano-fibrous scaffold for controlled delivery of recombinant human PDGF-BB. J Control Release. 2006;112(1):103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.01.011. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei G, Jin Q, Giannobile WV, Ma PX. The enhancement of osteogenesis by nano-fibrous scaffolds incorporating rhBMP-7 nanospheres. Biomaterials. 2007;28(12):2087–2096. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.12.028. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin Q, Ma PX, Giannobile WV. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Delivery via Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Soft-Tissue Repair. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2010;1:375–381. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.021.Secreted. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin Q, Wei G, Lin Z, et al. Nanofibrous Scaffolds Incorporating PDGF-BB Microspheres Induce Chemokine Expression and Tissue Neogenesis In Vivo. PLoS One. 2008;3(3):1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001729. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feng K, Sun H, Bradley M a., Dupler EJ, Giannobile WV, Ma PX. Novel antibacterial nanofibrous PLLA scaffolds. J Control Release. 2010;146(3):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.035. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawalec M, Sitkowska A, Sobota M, Sieron AL, Komar P, Kurcok P. Human procollagen type I surface-modified PHB-based non-woven textile scaffolds for cell growth: preparation and short-term biological tests. Biomed Mater. 2014;9(6):65005. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/9/6/065005. doi:10.1088/1748-6041/9/6/065005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen C-H, Lee M-Y, Shyu VB-H, Chen Y-C, Chen C-T, Chen J-P. Surface modification of polycaprolactone scaffolds fabricated via selective laser sintering for cartilage tissue engineering. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2014;40:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.04.029. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng Y, Ramos D, Lee P, Liang D, Yu X, Kumbar SG. Collagen functionalized bioactive nanofiber matrices for osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells: bone tissue engineering. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2014;10(2):287–298. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2014.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosellini E, Cristallini C, Guerra GD, Barbani N. Surface chemical immobilization of bioactive peptides on synthetic polymers for cardiac tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2015;26(9):515–533. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2015.1030991. doi:10.1080/09205063.2015.1030991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mashhadikhan M, Soleimani M, Parivar K, Yaghmaei P. ADSCs on PLLA/PCL Hybrid Nanoscaffold and Gelatin Modification: Cytocompatibility and Mechanical Properties. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2015;7(1):32–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim TH, Kim JJ, Kim HW. Basic fibroblast growth factor-loaded, mineralized biopolymer-nanofiber scaffold improves adhesion and proliferation of rat mesenchymal stem cells. Biotechnol Lett. 2014;36(2):383–390. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1366-4. doi:10.1007/s10529-013-1366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tallawi M, Rosellini E, Barbani N, et al. Strategies for the chemical and biological functionalization of scaffolds for cardiac tissue engineering: a review. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12(108):20150254. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.0254. doi:10.1098/rsif.2015.0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gu M, Liu Y, Chen T, et al. Is graphene a promising nano-material for promoting surface modification of implants or scaffold materials in bone tissue engineering? Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2014;20(5):477–491. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2013.0638. doi:10.1089/ten.TEB.2013.0638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shao Z, Zhang X, Pi Y, et al. Surface modification on polycaprolactone electrospun mesh and human decalcified bone scaffold with synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells-affinity peptide for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2015;103(1):318–329. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35177. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.35177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pan H, Zheng Q, Yang S, Guo X. Effects of functionalization of PLGA-[Asp-PEG]n copolymer surfaces with Arg-Gly-Asp peptides, hydroxyapatite nanoparticles, and BMP-2-derived peptides on cell behavior in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102(12):4526–4535. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35129. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.35129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Svobodova J, Proks V, Karabiyik O, et al. Poly(amino acid)-based fibrous scaffolds modified with surface-pendant peptides for cartilage tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2015 doi: 10.1002/term.1982. doi:10.1002/term.1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zanden C, Hellstrom Erkenstam N, Padel T, Wittgenstein J, Liu J, Kuhn HG. Stem cell responses to plasma surface modified electrospun polyurethane scaffolds. Nanomedicine. 2014;10(5):949–958. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.01.010. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mahjoubi H, Kinsella JM, Murshed M, Cerruti M. Surface modification of poly(D,L-lactic acid) scaffolds for orthopedic applications: a biocompatible, nondestructive route via diazonium chemistry. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(13):9975–9987. doi: 10.1021/am502752j. doi:10.1021/am502752j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang M, Cheng X, Zhu W, Holmes B, Keidar M, Zhang LG. Design of biomimetic and bioactive cold plasma-modified nanostructured scaffolds for enhanced osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20(5-6):1060–1071. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2013.0235. doi:10.1089/ten.TEA.2013.0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kong X, Wang J, Cao L, Yu Y, Liu C. Enhanced osteogenesis of bone morphology protein-2 in 2-N,6-O-sulfated chitosan immobilized PLGA scaffolds. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2014;122:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.07.012. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim BY, Bae JW, Park KD. Enzymatically in situ shell cross-linked micelles composed of 4-arm PPO-PEO and heparin for controlled dual drug delivery. J Control Release. 2013;172(2):535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.05.003. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Knaack S, Lode A, Hoyer B, et al. Heparin modification of a biomimetic bone matrix for controlled release of VEGF. J Biomed Mater Res - Part A. 2014;102A(10):3500–3511. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35020. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.35020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sakiyama-Elbert SE, Hubbell JA. Controlled release of nerve growth factor from a heparin-containing fibrin-based cell ingrowth matrix. J Control Release. 2000;69:149–158. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manning CN, Kim HM, Sakiyama-elbert S, Galatz LM, Havlioglu N, Thomopoulos S. Sustained Delivery of Transforming Growth Factor Beta Three Enhances Tendon-to-Bone Healing in a Rat Model. J Orthop Res. 2011;3(July):1099–1105. doi: 10.1002/jor.21301. doi:10.1002/jor.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang NX, von Recum HA. Affinity-based drug delivery. Macromol Biosci. 2011;11(3):321–332. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201000206. doi:10.1002/mabi.201000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vulic K, Shoichet MS. Affinity-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Tissue Repair and Regeneration. 2014 doi: 10.1021/bm501084u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thatiparti TR, Shoffstall AJ, von Recum HA. Cyclodextrin-based device coatings for affinity-based release of antibiotics. Biomaterials. 2010;31(8):2335–2347. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.087. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vulic K, Shoichet MS. Affinity-based drug delivery systems for tissue repair and regeneration. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15(11):3867–3880. doi: 10.1021/bm501084u. doi:10.1021/bm501084u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Battig MR, Soontornworajit B, Wang Y. Programmable release of multiple protein drugs from aptamer-functionalized hydrogels via nucleic acid hybridization. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(30):12410–12413. doi: 10.1021/ja305238a. doi:10.1021/ja305238a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lin C-C, Anseth KS. Controlling Affinity Binding with Peptide-Functionalized Poly(ethylene glycol) Hydrogels. Adv Funct Mater. 2009;19(14):2325. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200900107. doi:10.1002/adfm.200900107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Impellitteri NA, Toepke MW, Lan Levengood SK, Murphy WL. Specific VEGF sequestering and release using peptide-functionalized hydrogel microspheres. Biomaterials. 2012;33(12):3475–3484. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.032. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pettway GJ, Meganck JA, Koh AJ, Keller ET, Goldstein SA, McCauley LK. Parathyroid hormone mediates bone growth through the regulation of osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. Bone. 2008;42(4):806–818. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.11.017. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu X, Pettway GJ, McCauley LK, Ma PX. Pulsatile release of parathyroid hormone from an implantable delivery system. Biomaterials. 2007;28(28):4124–4131. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.034. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Min J, Braatz RD, Hammond PT. Biomaterials Tunable staged release of therapeutics from layer-by-layer coatings with clay interlayer barrier. Biomaterials. 2014;35(8):2507–2517. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.009. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reyes-Ortega F, Cifuentes A, Rodríguez G, et al. Acta Biomaterialia Bioactive bilayered dressing for compromised epidermal tissue regeneration with sequential activity of complementary agents. Acta Biomater. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.05.012. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Garcia-Honduvilla N, Cifuentes A, Bellon J, Bujan J, Martinez A. The angiogenesis promoter, proadrenomedullin N-terminal 20 peptide (PAMP), improves healing in both normoxic and ischemic wounds either alone or in combination with autologous stem/progenitor cells. Histol Histopathol. 2013;28(1):115–125. doi: 10.14670/HH-28.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Azodi-Deilami S, Abdouss M, Kordestani D. Synthesis and Characterization of the Magnetic Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Nanoparticles Using N, N -bis Methacryloyl Ethylenediamine as a New Cross-linking Agent for Controlled Release of Meloxicam. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;172:3271–3286. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-0769-6. doi:10.1007/s12010-014-0769-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cittadini A, Monti MG, Petrillo V, et al. Complementary therapeutic effects of dual delivery of insulin-like growth factor-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor by gelatin microspheres in experimental heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13(12):1264–1274. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr143. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfr143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Freeman I, Cohen S. The influence of the sequential delivery of angiogenic factors from affinity-binding alginate scaffolds on vascularization. Biomaterials. 2009;30(11):2122–2131. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.057. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hao X, Silva EA, Mansson-Broberg A, et al. Angiogenic effects of sequential release of VEGF-A165 and PDGF-BB with alginate hydrogels after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75(1):178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.028. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Awada HK, Johnson NR, Wang Y. Sequential delivery of angiogenic growth factors improves revascularization and heart function after myocardial infarction. J Control Release. 2015;207:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.034. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen RR, Silva EA, Yuen WW, Mooney DJ. Spatio-temporal VEGF and PDGF delivery patterns blood vessel formation and maturation. Pharm Res. 2007;24(2):258–264. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9173-4. doi:10.1007/s11095-006-9173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sun Q, Silva E a., Wang A, et al. Sustained release of multiple growth factors from injectable polymeric system as a novel therapeutic approach towards angiogenesis. Pharm Res. 2010;27(2):264–271. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-0014-0. doi:10.1007/s11095-009-0014-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Layman H, Li X, Nagar E, Vial X, Pham SM, Andreopoulos FM. Enhanced angiogenic efficacy through controlled and sustained delivery of FGF-2 and G-CSF from fibrin hydrogels containing ionic-albumin microspheres. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2012;23(1-4):185–206. doi: 10.1163/092050610X546417. doi:10.1163/092050610X546417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ruvinov E, Leor J, Cohen S. The promotion of myocardial repair by the sequential delivery of IGF-1 and HGF from an injectable alginate biomaterial in a model of acute myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 2011;32(2):565–578. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.097. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sung J, Barone PW, Kong H, Strano MS. Sequential delivery of dexamethasone and VEGF to control local tissue response for carbon nanotube fluorescence based micro-capillary implantable sensors. Biomaterials. 2009;30(4):622–631. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.052. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tengood JE, Ridenour R, Brodsky R, Russell AJ, Little SR. Sequential delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor for angiogenesis. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17(9-10):1181–1189. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0551. doi:10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Basmanav FB, Kose GT, Hasirci V. Biomaterials Sequential growth factor delivery from complexed microspheres for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4195–4204. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.017. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chang P-C, Chong LY, Dovban ASM, et al. Sequential platelet-derived growth factor-simvastatin release promotes dentoalveolar regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20(1-2):356–364. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0687. doi:10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kang MS, Kim J-H, Singh RK, Jang J-H, Kim H-W. Therapeutic-designed electrospun bone scaffolds: mesoporous bioactive nanocarriers in hollow fiber composites to sequentially deliver dual growth factors. Acta Biomater. 2015;16:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.12.028. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2014.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kempen DHR, Lu L, Heijink A, et al. Effect of local sequential VEGF and BMP-2 delivery on ectopic and orthotopic bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 2009;30(14):2816–2825. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.031. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim S, Kang Y, Krueger CA, et al. Sequential delivery of BMP-2 and IGF-1 using a chitosan gel with gelatin microspheres enhances early osteoblastic differentiation. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(5):1768–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.01.009. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pacheco H, Vedantham K, Aniket, Young A, Marriott I, El-Ghannam A. Tissue engineering scaffold for sequential release of vancomycin and rhBMP2 to treat bone infections. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102(12):4213–4223. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35092. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.35092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li L, Zhou G, Wang Y, Yang G, Ding S, Zhou S. Controlled dual delivery of BMP-2 and dexamethasone by nanoparticle-embedded electrospun nanofibers for the efficient repair of critical-sized rat calvarial defect. Biomaterials. 2015;37:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.015. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Song K, Rao N, Chen M, Huang Z, Cao Y. Enhanced bone regeneration with sequential delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor and sonic hedgehog. Injury. 2011;42(8):796–802. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.02.003. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang H, Zou Q, Boerman OC, et al. Combined delivery of BMP-2 and bFGF from nanostructured colloidal gelatin gels and its effect on bone regeneration in vivo. J Control Release. 2013;166:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.12.015. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yilgor P, Tuzlakoglu K, Reis RL, Hasirci N, Hasirci V. Incorporation of a sequential BMP-2/BMP-7 delivery system into chitosan-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30(21):3551–3559. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.024. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yilgor P, Huri G, Yasar U, et al. A biomimetic growth factor delivery strategy for enhanced regeneration of iliac crest defects. Biomed Mater. 2013;8(4):45009. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/8/4/045009. doi:10.1088/1748-6041/8/4/045009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yilgor P, Hasirci N, Hasirci V. Sequential BMP-2/BMP-7 delivery from polyester nanocapsules. J Biomed Mater Res - Part A. 2010;93:528–536. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32520. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.32520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zou Y, Brooks JL, Talwalkar V, Milbrandt TA, Puleo DA. Development of an injectable two-phase drug delivery system for sequential release of antiresorptive and osteogenic drugs. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2012;100(1):155–162. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31933. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.31933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang Y, Cooke MJ, Sachewsky N, Morshead CM, Shoichet MS. Bioengineered sequential growth factor delivery stimulates brain tissue regeneration after stroke. J Control Release. 2013;172(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.07.032. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sabo JK, Aumann TD, Kilpatrick TJ, Cate HS. Investigation of sequential growth factor delivery during cuprizone challenge in mice aimed to enhance oligodendrogliogenesis and myelin repair. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063415. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jaklenec A, Hinckfuss A, Bilgen B, Ciombor DM, Aaron R, Mathiowitz E. Sequential release of bioactive IGF-I and TGF-beta 1 from PLGA microsphere-based scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2008;29(10):1518–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.004. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nelson DM, Ma Z, Leeson CE, Wagner WR. Extended and sequential delivery of protein from injectable thermoresponsive hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2012;100(3):776–785. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34015. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.34015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tang G, Zhang H, Zhao Y, Li X, Yuan X, Wang M. Prolonged release from PLGA/HAp scaffolds containing drug-loaded PLGA/gelatin composite microspheres. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2012;23(2):419–429. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4493-2. doi:10.1007/s10856-011-4493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ozkizilcik A, Tuzlakoglu K. A new method for the production of gelatin microparticles for controlled protein release from porous polymeric scaffolds. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2014;8:242–247. doi: 10.1002/term.1524. doi:10.1002/term. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mirdailami O, Soleimani M, Dinarvand R, Reza M. Controlled release of rhEGF and rhbFGF from electrospun scaffolds for skin regeneration (Accepted article). J Biomed Mater Res - Part A. 2015:1–38. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Li Q, Zhou G, Yu X, Wang T, Xi Y, Tang Z. Porous deproteinized bovine bone scaffold with three-dimensional localized drug delivery system using chitosan microspheres Porous deproteinized bovine bone scaffold with three-dimensional localized drug delivery system using chitosan microspheres. Biomed Eng Online. 2015;14(33):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12938-015-0028-2. doi:10.1186/s12938-015-0028-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Paris JL, Román J, Manzano M, Cabañas MV, Vallet-regí M. Tuning dual-drug release from composite scaffolds for bone regeneration. Int J Pharm. 2015;486(1-2):30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.03.048. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]