Abstract

The sustainability of evidence-based programs is needed to obtain long-term benefits. To assess sustainability of Go Sun Smart (GSS), an occupational skin cancer prevention program disseminated to the North American ski industry. Fifty-three of the 68 ski areas from the original dissemination trial participated in 2012 and 2013, 5 to 7 years after program distribution by enhanced or basic dissemination strategies. Sustained use was measured by: (1) on-site observation of sun protection communication and (2) an online survey with senior managers. In the sustainability assessment, sun safety communication had declined, and dissemination strategy did not affect continued use. Managers held weaker attitudes about skin cancer importance and program fit, but more managers provided free/reduced-cost sunscreen than in the dissemination trial. Manager turnover was a key factor in program discontinuance. Sustainability remains a challenge. Additional research is needed to determine the best strategies for sustainability.

Keywords: Sustainability, Dissemination, Sun protection, Workplace

INTRODUCTION

The true measure of a prevention intervention’s success is how much it reduces risky health behaviors over the long term [1]. While, a careful review of the literature reveals that many interventions are effective in the near term, few of them have taken steps to determine whether these effects were long lived [2–4]. For the past decade, the authors have been involved in the development and dissemination of a theory-based intervention for occupational sun protection among outdoor workers in the North American ski industry [5]. Under the Go Sun Smart brand (GSS), the intervention, comprised of signage and brochures, employee training, and a website, was introduced to the 365 ski areas in the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA), the leading professional association, and potentially reached over 100,000 employees, in a randomized trial comparing a Basic Dissemination Strategy of industry-standard distribution to an Enhanced Dissemination Strategy adding theory-based communication. GSS [6], in common with similar evidence-based interventions [7–9], was successful in improving workers’ sun protection practices in the near term when ski area managers implemented GSS with sufficient intensity [10, 11]. However, within 2 years’ time, many of these same managers were less likely to use GSS materials [12], raising doubts about whether the initial improvements had been reinforced over time. The only other long-term follow-ups for sun safety interventions were conducted over 3 years or less [13–15].

Sustained efforts to convince outdoor workers to practice sun protection on the job are needed for several reasons. Outdoor workers are chronically exposed to ultraviolet radiation (UV), a primary cause of skin cancer [16, 17]. Lifetime UV exposure is linked to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and possibly melanoma; intermittent, severe exposure (i.e., sunburn) may be related to melanoma, basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and SCC [18–21]. Outdoor work is associated with non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), i.e., BCC and SCC [22, 23] and possibly an elevated risk of melanoma [24]. Preventing NMSC is a priority due to its extremely high prevalence (over 3 million annually [25]), tendency to recur [26, 27], disfigurement [28], treatment costs [29], and association with other cancers [30, 31]. Unfortunately, many outdoor workers fail to practice sun safety [32, 33] and remain at high risk for skin cancer from occupational UV exposure.

As used here, sustainability refers to the continuation of a program, its activities, and structures, when financial, organizational, and technical support from external organizations has ended [1, 34]. It has been estimated that over 40 % of many health programs do not last beyond the first few years [35]. In diffusion of innovations theory (DIT) [36, 37], sustainability occurs when a program such as GSS becomes institutionalized [38, 39], the final stage in organizational adoption [38, 39] (i.e., routinizing the innovation so it becomes part of organization’s normal activities) [40]. Innovations such as GSS are more likely to be institutionalized [37, 41] (i.e., sustained) when there is significant administrative support for its adoption and when the changes within the organization that its adoption requires become an integral feature of the organization’s structure. By contrast, some organizational factors, such as management turnover [42, 43], can contribute to discontinuance.

This paper reports the results of a long-term follow-up examining the sustainability of GSS 5 to 7 years after a trial in which it was disseminated throughout North America. Best-practice recommendations for sustainability assessment were followed, including using a valid longitudinal design with randomization, measuring continuation of program components, and exploring newly created organizational procedures/policies [2, 44, 45]. Sustained program effects on employee sun protection are reported elsewhere [46].

METHODS

Sample

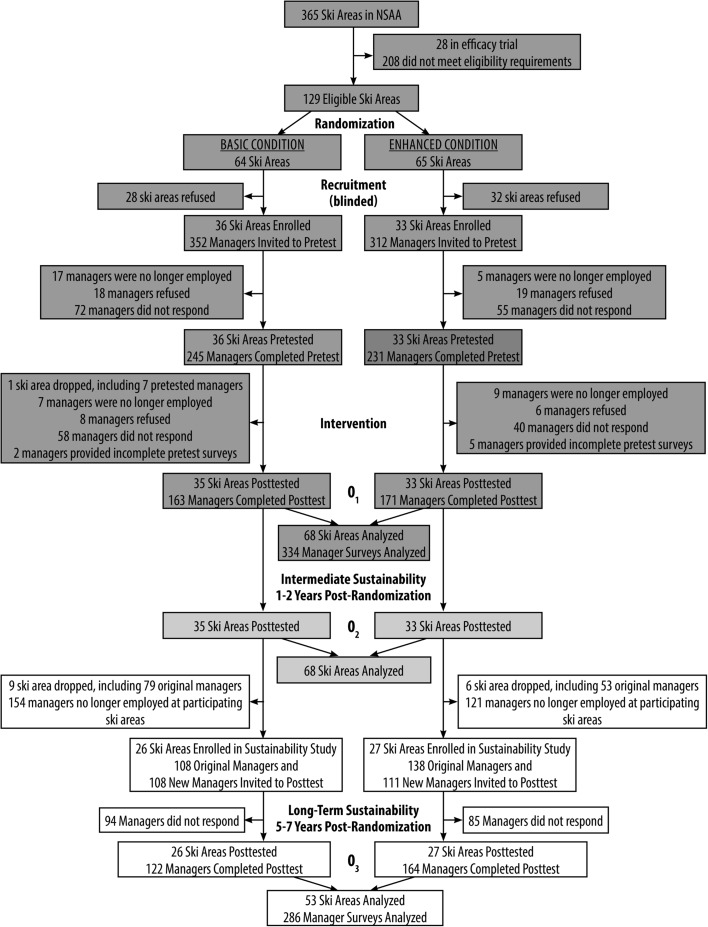

The senior-most manager (e.g., General Manager) or manager who served as the key contact for the 2004–08 GSS dissemination trial was re-contacted and invited to participate in this study. Ultimately, managers at 53 of the original 68 areas agreed to participate (77.9 %; 52 participated in 2012 and 1 delayed participation until 2013; see CONSORT diagram in Fig. 1). During recruitment, names and contact information of senior managers at the ski area were updated.

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram for trial

Go Sun Smart program

GSS advised employees to practice sun protection on the job including using sunscreen, sunglasses, hats, and protective clothing, seeking shade, reducing time in the midday sun, and avoiding sunburning. As described previously, GSS was based on DIT and principles of persuasive communication and included posters, small decals, magnets, outdoor signage, signage for ski/snowboard schools, brochures for employees and guests, a training program with script and slides, newsletter articles, and brief messages (see materials at http://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/programDetails.do?programId=308006]).

Procedures

Ski areas (n = 68) were originally recruited to a two-group randomized trial that compared two dissemination strategies in the fall of 2004–06 in three annual waves. All ski areas received the GSS from the industry’s leading professional association (i.e., National Ski Areas Association) in 2004–07 through a Basic Dissemination Strategy (BDS). Half the ski areas were randomized by the project statistician to an Enhanced Dissemination Strategy (EDS) (n = 33 ski areas; 12 in 2004, 11 in 2005, and 10 in 2006) based on principles of DIT. An immediate posttest assessment of GSS use (O1) was performed using on-site observation in the winter during the season when they were first recruited. Senior managers were surveyed in the fall and winter, at the beginning and end of that season. All ski areas received GSS for up to 2 years after the immediate posttest. An intermediate-term follow-up assessment of GSS use (O2) using the on-site observation was performed two seasons (n = 27 in winters 2006) or one season (n = 41 ski areas in winters of 2007 or 2008) later.

From January to April of 2012, sustained use of GSS was measured (O3), which was 5 to 7 years after the immediate posttest (O1) (sustained use was assessed at 1 ski area in March 2013) using three methods. First, project staff completed an on-site observation of GSS materials and other sun protection communication. Second, the contact manager or another senior manager was interviewed using a semi-structured interview protocol. Third, in March, senior managers at the ski areas were invited to complete an online survey. Managers received two reminders over 2 weeks. All procedures were approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the San Diego State University IRB.

Go Sun Smart dissemination strategies

Two dissemination strategies were compared in the earlier dissemination trial. The BDS used the normal procedures by the industry’s professional association to distribute safety programs. It included informational booths at national and regional trade shows, promotional materials for GSS (e.g., logo magnets, lip balm, and post-it notes), 1-page informational tip sheets, and free starter kits of materials (2 per year over 3 years in October/November and January). All ski areas received GSS through the BDS from 2004–07.

The EDS included all BDS activities plus face-to-face, as well as online and phone, contact between project staff and senior managers. Based on DIT, project staff attempted to reinforce the need for occupational sun safety, gain senior managers’ commitment to use GSS, plan its implementation, and provide continued support for using GSS. Staff also sought to reduce managers’ uncertainty about GSS by describing GSS’ fit with ski area operations and connecting GSS to the NSAA’s endorsement. Staff coached managers on how best to use GSS, advised them about the importance of identifying internal champions in their employ to provide vocal support to GSS and reinforced their decisions to use GSS [37, 47]. Project staff visited the ski areas from November to January and followed up with managers by telephone and email monthly or more often through the end of March. The BDS and EDS were described in more detail elsewhere [10].

On-site observation of sustained Go Sun Smart use

The on-site observation protocol used in the dissemination trial for O1 and O2 was used to assess the visible number of GSS items the ski areas [10] were using during the sustainability assessment (O3). During a one-day visit, project staff recorded all printed GSS materials on display (i.e., 15 posters/signs, 3 brochures, 2 static, clings and 1 logo magnet were originally distributed in the earlier dissemination trial). Staff also recorded any other sun protection messages (e.g., employer-generated; commercial advertising). All locations were searched, including employee-only areas (e.g., offices, locker rooms, chair lift shacks). Staff recorded where each item was located and whether it was in an employee-only area. Three measures of program use were created by summing the counts: GSS items, non-GSS items excluding commercial advertising, and total sun protection communication. The observation protocol was validated in the earlier effectiveness trial on GSS [6].

Survey of senior managers on sun protection communication and actions

The questionnaire for managers measured their use of GSS, other sun protection messages for employees and guests, and administrative actions promoting sun safety. Using questions from the dissemination trial [10], managers reported whether they had communicated with employees about sun protection, and if so, whether they used a poster/sign, brochure, article, or message in an employee newsletter or email message or link to the GSS website. They reported on whether they conducted employee training on sun protection. In the dissemination trial, managers’ reports were validated by positive correlations with employees’ recall of sun safety messages [10]. Managers also were asked if the ski area made any of the following changes to support employee sun safety: provided free/reduced-cost sunscreen, sunglasses, or hats, conducted skin screenings, created a policy on sun safety, or included sun safety in a health/safety fair. Managers’ attitudes on occupational sun safety were assessed, i.e., employees’ susceptibility to and importance of skin cancer and characteristics of worksite sun protection education (see Table 4). Managers described their job characteristics (length of employment, work indoors/outdoors/both) and demographics (age, education, Hispanicity, race, gender).

Table 4.

Managers’ reports related to Go Sun Smart by assessment period and dissemination strategy

| Assessment period | Dissemination strategy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 547 managers at 51 ski areas)a | O1 and O3 combined (n = 547 managers at 51 ski areas)a | O3 only (n = 286 managers at 53 ski areas)b | |||||||

| O1 | O3 | p | Basic | Enhanced | p | Basic | Enhanced | p | |

| Reported use of Go Sun Smart for employees | |||||||||

| Poster or sign | 93.3 % (88.8 %,96.1 %)c | 84.9 % (78.2 %,89.8 %)c | 0.002 | 85.9 % (78.3 %,91.1 %)c | 92.8 % (88.2 %,95.7 %) | 0.016 | 76.8 % (64.7 %,85.7 %)c | 88.9 % (81.2 %,93.7 %)c | 0.017 |

| Brochure | 67.8 % (59.3 %, 75.2 %) | 58.5 % (49.6 %, 66.8 %) | 0.029 | 54.4 % (43.6 %, 64.9 %) | 71.2 % (62.6 %, 78.6 %) | 0.007 | 48.7 % (35.1 %, 62.5 %) | 67.0 % (55.4 %, 76.8 %) | 0.024 |

| Article/messages in newsletter or flyer | 65.8 % (55.6 %,74.7 %) | 55.5 % (44.9 %, 65.7 %) | 0.023 | 63.9 % (50.2 %, 75.6 %) | 57.6 % (45.6 %, 68.8 %) | 0.242 | 60.8 % (46.3 %, 73.6 %) | 52.7 % (40.7 %, 64.3 %) | 0.194 |

| Message sent by email or on ski area website | 40.3 % (31.4 %, 49.8 %) | 30.8 % (22.9 %, 40.1 %) | 0.028 | 38.9 % (27.9 %, 51.2 %) | 32.1 % (23.3 %, 42.3 %) | 0.186 | 31.4 % (21.1 %, 43.9 %) | 33.1 % (24.2 %, 43.4 %) | 0.410 |

| Provision of sun protection items to employees | |||||||||

| Free or reduced-cost sunscreen | 63.8 % (53.1 %, 73.3 %) | 70.8 % (61.2 %, 78.9 %) | 0.057 | 69.7 % (56.3 %, 80.4 %) | 65.0 % (52.7 %, 75.5 %) | 0.290 | 69.6 % (54.2 %, 81.6 %) | 69.5 % (56.3 %, 80.1 %) | 0.495 |

| Hat | 76.4 % (64.9 %, 85.0 %) | 56.8 % (43.6 %, 69.0 %) | <0.001 | 69.3 % (51.4 %, 82.8 %) | 64.3 % (49.1 %, 78.6 %) | 0.365 | 55.2 % (35.1 %, 73.8 %) | 52.5 % (34.8 %, 69.5 %) | 0.422 |

| Sunglasses or goggles | 13.3 % (8.8 %, 19.5 %) | 7.6 % (4.7 %, 11.9 %) | 0.014 | 10.2 % (6.1 %, 16.5 %) | 9.9 % (6.3 %,1 5.2 %) | 0.464 | 8.5 % (4.0 %, 17.2 %) | 5.7 % (2.8 %, 11.4 %) | 0.204 |

| Shade cover in work areas | 49.5 % (41.7 %, 57.3 %) | 40.9 % (33.9 %, 48.3 %) | 0.026 | 48.5 % (39.2 %57.8 %) | 41.9 % (34.1 %, 50.1 %) | 0.146 | 39.1 % (29.4 %, 49.9 %) | 39.0 % (30.9 %, 47.9 %) | 0.495 |

| Reported communication with guests | |||||||||

| Written message on a poster, sign, newsletter article, etc. | 87.3 % (81.4 %,91.6 %) | 66.5 % (57.9 %,74.1 %) | <0.001 | 73.1 % (62.7 %,81.4 %) | 83.4 % (76.2 %, 88.8 %) | 0.027 | 59.6 % (45.7 %,72.2 %) | 73.4 % (62.4 %,82.0 %) | 0.049 |

| Susceptibility and importance of skin cancer | |||||||||

| Employees likelihood of getting skin cancer (strongly agree [5]—strongly disagree [1]) | 3.09 (2.94, 3.24) | 3.23 (3.08, 3.37) | 0.054 | 3.14 (2.96, 3.31) | 3.18 (3.02, 3.33) | 0.364 | 3.30 (3.09, 3.52) | 3.19 (3.01, 3.37) | 0.207 |

| Skin cancer is an important health concern to employees (strongly agree [5]—strongly disagree [1]) | 4.13 (4.02, 4.24) | 4.16 (4.06, 4.27) | 0.319 | 4.13 (4.00, 4.25) | 4.17 (4.06, 4.28) | 0.308 | 4.10 (3.95, 4.25) | 4.12 (4.00, 4.25) | 0.407 |

| Skin cancer is an important health concern to me (strongly agree [5]—strongly disagree [1]) | 4.37 (4.26, 4.48) | 4.25 (4.15, 4.36) | 0.024 | 4.25 (4.12, 4.38) | 4.37 (4.26, 4.49) | 0.081 | 4.15 (3.98, 4.33) | 4.31 (4.16, 4.46) | 0.086 |

| Perception of characteristics of sun protection education | |||||||||

| Affordability (too expensive [1]—very affordable [5]) | 4.15 (4.02, 4.29) | 3.88 (3.76, 4.01) | <0.001 | 3.96 (3.80, 4.12) | 4.08 (3.94, 4.21) | 0.128 | 3.79 (3.57, 4.02) | 3.91 (3.72, 4.10) | 0.222 |

| Compatibility with workplace (compatible [5]—incompatible [1]) | 4.31 (4.11, 4.52) | 3.68 (3.48, 3.88) | <0.001 | 3.97 (3.72, 4.22) | 4.02 (3.80, 4.24) | 0.375 | 3.78 (3.43, 4.12) | 3.64 (3.35, 3.93) | 0.275 |

| Ease of implementation (easy [5]—difficult [1]) | 4.19 (4.04, 4.33) | 3.96 (3.83, 4.10) | 0.005 | 3.99 (3.82, 4.15) | 4.16 (4.02, 4.31) | 0.056 | 3.94 (3.70, 4.18) | 4.01 (3.81, 4.21) | 0.336 |

| Fit with company values (fits [5]—does not fit [1]) | 4.43 (4.24, 4.63) | 3.66 (3.48, 3.84) | <0.001 | 3.99 (3.76, 4.22) | 4.10 (3.90, 4.30) | 0.236 | 3.75 (3.40, 4.09) | 3.68 (3.39, 3.98) | 0.392 |

| Simplicity (too simple [1]—too complicated [5]) | 2.39 (2.27, 2.50) | 2.72 (2.61, 2.83) | <0.001 | 2.58 M (2.45, 2.70) | 2.53 M (2.42, 2.64) | 0.301 | 2.63 (2.45, 2.81) | 2.81 (2.67, 2.95) | 0.062 |

| Appropriateness for employees (appropriate [5]—inappropriate [1]) | 4.66 (4.50, 4.82) | 4.04 (3.89, 4.20) | <0.001 | 4.32 (4.13, 4.51) | 4.38 (4.21, 4.55) | 0.310 | 4.02 (3.70, 4.35) | 4.06 (3.79, 4.33) | 0.437 |

aCompleters from the 51 ski areas that participated in both the dissemination trial and sustainability assessment

bCompleters from the 53 ski areas that participated in the sustainability assessment only

c95 % confidence interval

Ski area characteristics

Descriptive information for each ski area was collected by project staff. This included the number of employees, number of female senior managers, latitude and elevation, and mean annual number of hours of sunshine (from the National Weather Service).

Statistical analysis

On-site observations of GSS materials in use at the ski areas were compared across the dissemination trial (O1 and O2) and sustainability assessment (O3). Also, the two dissemination strategies (BDS v. EDS) were compared. All comparisons were performed using PROC GLIMMIX in SAS and adjusted for organizational characteristics (number of employees was dropped because the model would not converge). Analyses were conducted first on the ski areas that participated in the sustainability assessment (i.e., completers analysis). Next, the effect of ski area dropout was assessed using imputation in which ski areas that dropped out were assigned a value of 2 × O2 − O1 to model the assumption that even though they dropped out, these ski areas continued to experience the change in program use witnessed between O1 and O2, not just the level of use at O2.

Managers’ survey responses were compared between the dissemination trial (O1) and the sustainability assessment (O3), adjusting for clustering within resorts. Managers were not surveyed at O2. This analysis used responses collected from managers successfully followed up (i.e., no imputation was made for missing values), as they were secondary measures.

When planning the dissemination trial, a 1-tailed alpha criterion was used to determine the needed sample size [10] because we planned to evaluate a directional hypothesis that that EDS was better than BDS. We did not plan on interpreting results indicative of the inferiority of EDS, because failure to reject the null hypothesis with this 1-tailed test would lead to the same conclusion as with a 2-tailed test: recommend the BDS. The same sample was used in the sustainability assessment, so a 1-tailed alpha was employed in all tests on sustainability of GSS.

RESULTS

Profile of ski areas and senior managers

The characteristics of participating ski areas are reported in Table 1. The resorts ranged in size (based on employee numbers), ownership, and elevation; were located across North America at a variety of latitudes; and a quarter of them received a large amount of sunshine hours. Reasons for non-participation included lack of interest, change in ownership/management, and low snow levels leading to late opening or early closing. A higher proportion of western ski areas (100 % west, 90 % southwest, 100 % Rocky Mountain, and 88.9 % northwest) participated than eastern ski areas (63.2 % northeast and 16.7 % central/southeast; p = 0.001). Thus, it was not surprising to find that participating ski areas had higher elevations (participated M = 5504 ft (base) and 8073 ft (summit); did not participate M = 3458 ft (base) and 4930 ft, p = 0.013 and 0.002, respectively) than non-participating ski areas.

Table 1.

Profile of ski areas and senior managers

| Resort characteristics (n = 53) | % |

|---|---|

| Number of employees (mean = 467.3, sd = 374.2) | |

| Less than 250 | 26.4 |

| 250–499 | 39.6 |

| 500–999 | 26.4 |

| 1000 or more | 7.6 |

| Percent of female managers | 25.6 |

| Manager turnover rate | 52.1 |

| Ownership type | |

| Multi-resort ownership | 20.8 |

| Single-resort ownership | 79.2 |

| Region | |

| West | 15.1 |

| Northwest | 15.1 |

| Southwest | 34.0 |

| Rocky Mountains | 11.3 |

| Northeast | 22.6 |

| Central and Southeast | 1.9 |

| Latitude of resort (mean = 42.0°N, sd = 4.3°) | |

| Base elevation (mean = 5504.3 ft., sd = 2810.9 ft) | |

| Summit elevation (mean = 8073.5 ft, sd = 3435.8 ft) | |

| Annual mean number of sunshine hours | |

| 2400 h or less | 28.3 |

| 2401–3200 h | 45.3 |

| 3201 h or more | 26.4 |

| Manager characteristics (n = 286) | % |

| Work outdoors | |

| Mostly outdoors | 33.3 |

| Outdoors and indoors equally | 30.9 |

| Mostly indoors | 35.8 |

| Involvement in decisions about workplace procedures and policy on safety and health of employees | |

| Never or rarely | 3.8 |

| Some of the time | 21.7 |

| Most or all of the time | 74.5 |

| Age (mean = 47.8, sd = 11.3) | |

| 22–39 | 23.1 |

| 41–49 | 28.9 |

| 50–59 | 31.0 |

| 60–78 | 17.0 |

| Education | |

| High school diploma or less | 8.2 |

| Trade, technical or vocational education, or some college | 39.0 |

| College graduate or postgraduate degree | 52.8 |

| Hispanic | 1.5 |

| Race | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native/First Nations | 0.7 |

| White | 98.6 |

| More than one race | 0.7 |

| Ever been told by doctor that you had skin cancer | 15.7 |

| Female | 26.9 |

A total of 465 senior managers received an invitation to complete the online survey, with 286 complying (62.2 %; n = 182 online and 104 by mail; Fig. 1). Of these, 146 were interviewed in O1 and 140 were new in O3. Given this, analyses were conducted treating the O1 versus O3 comparison as between subjects. Response rate to the O1 survey did not differ between resorts participating (69.2 %) or not participating (62.9 %) in the sustainability assessment (O3; p = 0.543). Senior managers were older, highly educated, nearly all white, and mostly male. Two thirds worked outdoors at least some of the time, and nearly all were decision makers concerning safety and health of employees. Also, 15.7 % had been diagnosed with skin cancer. Respondents held jobs ranging from the senior-most manager (e.g., president, general manager, and chief operating officer) to departmental managers (e.g., accounting, base and lift operations, ski school, and ski patrol) to personnel and safety managers (e.g., human resources and risk management; see Table 1).

Sustained use of Go Sun Smart

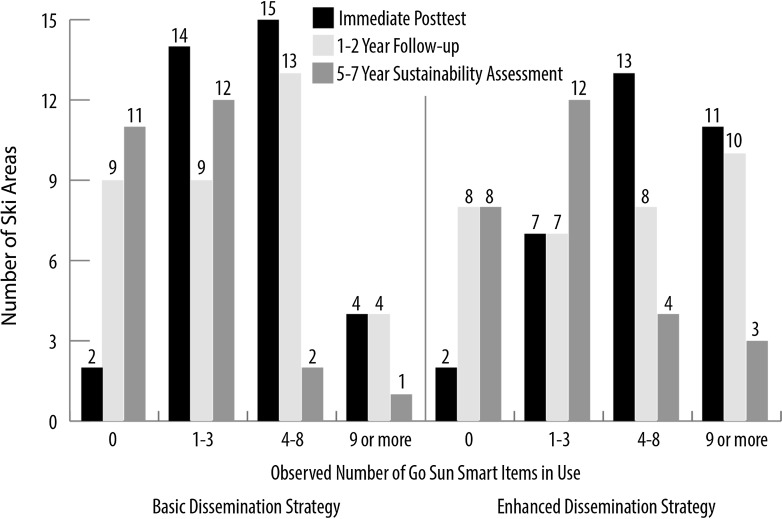

At the sustainability assessment (O3), the 53 ski areas were observed to be using 2.19 GSS items on average (M = 2.51 items using imputation, i.e., 2 × O2 − O1). Ski area use of GSS had declined substantially at the sustainability assessment in the analyses of both the ski areas completing the sustainability assessment and when imputing missing use values for those not followed up (Fig. 2 and Table 2).

Fig 2.

Observed number of Go Sun Smart items in use by Basic and Enhanced Dissemination Strategy at Immediate Posttest (01), 1- to 2-year follow-up (02), and 5- to 7-year sustainability assessment (03)

Table 2.

Mean number of messages in use at ski areas by assessment period

| Items in usea | Completers (n = 53 ski areas) | Intent-to-treat (n = 68 ski areas)b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | O2 | O3 | p | O1 | O2 | O3 | p | |

| Go Sun Smart only | 6.77 (5.23, 8.32)c |

5.11 (3.67, 6.55)c |

2.19 (1.29, 3.09)c |

<0.001 | 6.24 (4.97, 7.50)c |

4.72 (3.48, 5.96)c |

2.51 (1.45, 3.58)c |

<0.001 |

| All Sun Safety messages | 7.68 (6.09, 9.27) |

5.38 (3.94, 6.82) |

4.94 (3.15, 6.73) |

<0.001 | 7.12 (5.81, 8.42) |

4.96 (3.71, 6.20) |

4.65 (3.05, 6.24) |

<0.001 |

aExcluding retail messages (i.e., messages advertising sunscreen, lip balm, goggles, or clothing for sale)

bFor intent-to-treat analyses, ski areas not followed up in the sustainability assessment (O3) were assigned a score equal to 2 × O2 − O1 to represent the decline in use predicted by the difference between O1 and O2 assessments in the Dissemination Trial

c95 % confidence interval

Use of any sun safety communication

When GSS materials and non-GSS sun safety messages observed at the ski areas were combined (M = 4.94 [sd = 6.50; range = 0–34] completers; M = 4.65 with imputation), the decline in sun safety messaging was smaller at the sustainability assessment but still statistically significant (Table 2).

Effect of dissemination strategy on sustained GSS use

The continued impact of the two dissemination strategies was explored at the sustainability assessment (O3 only) and by collapsing across all three assessments (O1, O2, O3). Dissemination strategy did not affect continued use of GSS (O3: BDS M = 1.69, EDS M = 2.67, p = 0.14) or the presence of any sun safety messages (O3: BDS M = 4.42, EDS M = 5.44, p = 0.29) at the sustainability assessment. However, across all three observations, use of the GSS items was higher at ski areas in the EDS than in the BDS conditions in the imputation analysis, as was use of any sun safety communication in both the completer and imputation analyses (Table 3). Further, it appears from Fig. 2 that more ski areas in the EDS group may have continued to use a relatively larger number of GSS items (9 or more) than in the BDS group.

Table 3.

Mean number of messages observed at ski areas by dissemination condition for all assessments combined

| Items in usea | Completers (n = 53 ski areas) | Intent-to-treat (n = 68 ski areas) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic | Enhanced | p | Basic | Enhanced | p | |

| Go Sun Smart only | 3.82 (2.77, 4.87)c | 5.53 (4.32, 6.74)c | 0.052 | 3.57 (2.75, 4.39)c | 5.46 (4.31, 6.62)c | 0.017 |

| All Sun Safety messages | 5.05 (3.73, 6.38) | 6.91 (5.61, 8.22) | 0.022 | 4.58 (3.56, 5.61) | 6.63 (5.39, 7.86 | 0.006 |

aExcluding retail messages (i.e., messages advertising sunscreen, lip balm, goggles, or clothing for sale)

bFor intent-to-treat analyses, ski areas not followed up in the sustainability assessment (O3) were assigned a score equal to 2 × O2 − O1 to represent the decline in use predicted by the difference between O1 and O2 assessments in the Dissemination Trial

c95 % confidence interval

Effect of management turnover on sustained GSS use

Management turnover was a barrier to sustained GSS use: high-use ski areas in the dissemination trial had lower GSS use in the sustainability assessment when ≥40 % of managers had turned over from O1 to O3; areas with no turnover continued to have high use of GSS (GSS use at O1 by management turnover interaction, p < 0.001).

Managers reports of sustained GSS use

Managers also reported a decline in GSS use at the sustainability assessment (O3) relative to reports from the immediate posttest (O1) in the dissemination trial. Managers were less likely to report using posters, brochures, newsletter articles or flyers, and messages sent by email or on ski area websites to communicate about sun safety with employees at the long-term follow-up (Table 4). Managers’ reported use of posters and brochures was higher at ski areas in the EDS than BDS condition, both at the sustainability assessment (O3 only) and when combining the dissemination trial posttest (O1) and the sustainability assessment (O3) (Table 4). Managers also reported that their communication to guests about sun safety was lower at the sustainability assessment (O3) than in the dissemination trial (O1); however, this communication was higher in the EDS than in the BDS condition (Table 4).

At the same time, we observed that managers reported weaker attitudes about the importance of skin cancer and perceived that sun protection education for employees was not as good a fit with their organization 5 to 7 years after dissemination. Specifically, at the sustainability assessment (O3), they perceived that skin cancer was less important for managers themselves and were less likely to believe that workplace sun safety education was affordable, compatible with the workplace, easy to implement, fit the company values, simple, and appropriate for employees than at the posttest of the dissemination trial (O1; Table 4).

By contrast, more managers reported providing free or reduced-cost sunscreen to employees at the sustainability assessment (O3) than in the dissemination trial (O1) (Table 4). Provision of hats, sunglasses/goggles, and shade to employees did decline at the sustainability assessment. Still, about half of the managers reported providing hats and shade in work areas (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

The GSS occupational skin cancer prevention program demonstrated only modest sustainability 5 to 7 years after its distribution. Once promotional efforts by our team and the NSAA ended, most managers stopped using all but a few of the GSS items. Managers at a small group of ski areas, however, remained committed to extensive use of the program. This is not surprising. Ski area managers face an ongoing litany of organizational priorities, both health and non-health related. Many of these, moreover, were bound to reduce the level of commitment necessary to continue a program such as GSS. Also, some of the managers, who were quick to use GSS when first introduced, may have believed that their initial efforts were sufficient in addressing the sun safety need among their employees. As a result, sun safety may have been demoted on their safety agenda by more immediate and pressing issues.

When compared to data from our initial examination of sustainability [12], the decline in use was most pronounced in the first years following its distribution, with smaller declines in subsequent years. As others have noted [48], our findings suggest that active, long-term investments to promote heath programs such as GSS are essential for sustaining their initial effects.

That said, our team discovered that many of the ski areas provided sunscreen products to employees in their efforts to encourage employees to take precautions when working outdoors. This suggests that the dissemination of GSS may have contributed to a cultural shift in how ski area management viewed the importance of sun safety to their corporate health. As mentioned, research on DIT [36, 37] has found that the more an organization changes to accommodate an innovation, the more likely it will persist [41] and become institutionalized [37, 41].

On another front, the data gathered on sustainability also suggest factors that may have undermined sustainability, beginning with the high rate of turnover among managers. The ski industry, and perhaps similar enterprises in outdoor recreation, experiences a considerable mobility among managers. In the decade our team was involved with this industry, we grew accustomed to having to re-introduce ourselves to a new manager, scrambling to win their support, and introducing them to the GSS program. This suggests, at minimum, that the organizational stability necessary to increase the odds of an innovation such as GSS becoming an integral part of its policies about employee safety was missing.

Together, these findings call for further sustainability research to identify program components and dissemination strategies that can provide the financial, organizational, and technical support needed to sustain them. These could involve the provision external, and internal supports for program institutionalization. To be sustained, programs need to be designed to be modifiable [34] and inexpensive to continue, especially where materials have limited shelf life (e.g., signage can become damaged by weather and need replacement). Program supports might include providing message templates that can be manipulated and reprinted by employers and electronic versions of face-to-face trainings on sun safety. Also, managers should be taught the behavior change principles used in GSS so they can use them when creating their own sun protection communication.

Periodic refresher training and distribution of program materials conducted by industry professional associations could provide essential external support for program sustainability [34]. Ongoing training should prompt renewed interest in occupational sun safety, keep it on the workplace safety agenda, and restore managers’ commitment to implementation. Refresher sessions have reintroduced and maintained recommended behaviors in programs aimed at individuals [49, 50]. Further, holding this training at the annual or regional industry meetings that several employers can attend could make it cost effective and the ties with other organizations that use the program may help to sustain its use.

It also may be useful to encourage workplaces to adopt formal workplace sun safety policies as an internal administrative support for program sustainability. Policies persist even when organizational priorities shift and managers turnover by reminding managers to promote sun safety to employees and signaling the organization’s commitment to sun safety over the long term [2]. Policy development, including workplace health policies and policies requiring provision of health education programs [51, 52], has improved health outcomes [51, 53–57]. Managers should be advised to adopt policies that enact training in personal sun protection, plus environmental controls (e.g., shade and work schedules) and administrative procedures (e.g., risk assessment, supervisor training, policy review/monitoring, resource allocation, contractor compliance, and posting UV Index) [58–63]. Such policies will serve to establish both organizational and individual agendas for sun safety, integrate GSS into the workplace operations, and brand GSS as part of an organization’s culture. Finally, both refresher training and policy adoption would address two barriers to program use that appeared to produce discontinuance of GSS, i.e., management turnover and wavering commitments [42, 43]. Refreshers and policies can inform new managers about the need for occupational sun protection, show them how to use GSS to address it, and formalize the organization’s commitment to occupational sun safety. The longitudinal assessment of program sustainability by organizations is rare [13, 14, 45]. Most studies of workplace interventions have explored immediate impacts on worker knowledge and behavior [64], and no studies on skin cancer prevention have been assessed beyond 2 years.

This sustainability assessment had a few limitations, including the loss of 15 ski areas who did not agree to the 5- to 7-year follow-up and the use of self-report of program use by senior managers. However, the observational data corroborated these self-reports. While less than 20 % of the ski areas in the NSAA membership were assessed, we randomly selected from among those meeting eligibility criteria to minimize bias. Intent-to-treat methods are based on assumptions about drop outs that are not always accurate, as we found in our effectiveness trial [6]. The ski industry may limit the generalizability of the findings, e.g., operating in the winter, the season with low ambient UV, having long-standing efforts to address workplace safety, formal risk managers, and safety committees, controlling access to work areas, and having well-established communication channels. Still, it is an integral part of the large U.S. outdoor recreation industry [65] with diverse employers and workplace cultures, and many employees who routinely work (and recreate) outdoors at high elevation, in dry climates, and on reflective snow surfaces [66–69], where they receive substantial, chronic UV exposure [7]. Further, employees are mostly white with fair skin [6, 11] highly susceptible to skin cancer [70]; a large proportion are male and young, groups least likely to practice sun safety [71–74]; half reported sunburns [6, 11]; and many are long-term, low-paid seasonal workers [74], with limited health insurance. Thus, the results should generalize to other similar industries, too.

Sustainability remains a challenge for programs such as the GSS occupational sun protection program. Many employers continued to use only a small amount of program materials although several employers did supplement program materials with their own messages. Even with supplementation, program use at most workplaces was below the level that affected employees’ sun protection when it was originally disseminated. Health professionals need to plan efforts to maintain program use and overcome factors such as management turnover to make real change in the disease prevention behavior in settings such as workplaces.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA159840).

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the appropriate institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

David Buller was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and received a salary from Klein Buendel, Inc., his employer. David Buller’s spouse owns stock in Klein Buendel, Inc. Barbara Walkosz was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and received a salary from Klein Buendel, Inc., her employer. Barbara Walkosz has no financial disclosures. Peter Andersen was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and received a salary from San Diego State University, his employer. Peter Andersen has no financial disclosures. Michael Scott was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and received compensation from Mikonics, Inc. Michael Scott has no financial disclosures. Gary Cutter was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Department of Defense, received a salary from the University of Alabama, Birmingham, his employer, participated on Data and Safety Monitoring Committees focus on medical research for Apotek, Ascendis, Biogen-Idec, Cleveland Clinic, Glaxo Smith Klein Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Pharmaceuticals, Modigenetech/Prolor, Merck/Ono Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Neuren, PCT Bio, Teva, Vivus, NHLBI (Protocol Review Committee), NINDS, NMSS, and NICHD (OPRU oversight committee), and consulted, received speaking fees, and served on advisory Boards for Alexion, Allozyne, Bayer, Consortium of MS Centers (grant), Klein Buendel, Inc., Genzyme, Medimmune, Munck Wilson Mandala LLP, Novartis, Nuron Biotech, Receptos, Revalesio, Sanofi-Aventis, Spiniflex Pharmaceuticals, Somahlution, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Xenoport. Gary Cutter owns Pythagoras, Inc., a private consulting company.

Footnotes

Implications

Implication for researchers: Assessment of program effects over several years is needed to determine whether dissemination strategies have lasting effects on health behavior that can potentially reverse disease trends.

Implications for practitioners: Competing priorities and turnover in management pose challenges to sustained use of evidence-based workplace prevention programs. Long-term efforts are needed early in program dissemination to avoid initially steep declines in program use once external support for program implementation is withdrawn.

Implication for policy makers: Creating a culture of sun safety at the workplace might be a side benefit of disseminating an evidence-based occupational sun protection program that could support sustainability of workplace disease prevention.

References

- 1.Thompson B, Winner C. Durability of community intervention programs: definitions, empirical studies, and strategic planning. In: Bracht N, editor. Health promotion at the community level: new advances. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1999. pp. 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(11):2059. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stirman SW, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellamy R. A systematic review of educational interventions for promoting sun protection knowledge, attitudes and behaviour following the QUESTS approach. Med Teach. 2005;27(3):269–275. doi: 10.1080/01421590400029558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Authors. The Go Sun Smart campaign: achieving individual and organizational change for occupational sun protection. In: Rice R, Atkin C, eds. Public Communication Campaigns. Vol 4th. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012:191–204.

- 6.Authors. Randomized trial testing a worksite sun protection program in an outdoor recreation industry. Health Educ Behav. 2005; 32(4): 514–535. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Glanz K, Buller DB, Saraiya M. Reducing ultraviolet radiation exposure among outdoor workers: state of the evidence and recommendations. Environ Heal. 2007;6(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayer J, Slymen DJ, Clapp EJ, et al. Promoting sun safety among US Postal Service letter carriers: impact of a 2-year intervention. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(3):559–565. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glanz K, Maddock JE, Lew RA, Murakami-Akatsuka L. A randomized trial of the Hawaii SunSmart program’s impact on outdoor recreation staff. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(6):973–978. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.113466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Authors. Enhancing industry-based dissemination of an occupational sun protection program with theory-based strategies employing personal contact. Am J Health Promot. 2012; 26(6): 356–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Authors. Expanding occupational sun safety to an outdoor recreation industry: a translational study of the go sun smart program. Trans Behav Med. 2012; 2(1) :10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Authors. Sustainability of the dissemination of an occupational sun protection program in a randomized trial. Health Educ Behav. 2012; 39(4): 498–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Weinstock MA, Rossi JS, Redding CA, Maddock JE. Randomized controlled community trial of the efficacy of a multicomponent stage-matched intervention to increase sun protection among beachgoers. Prev Med. 2002;35(6):584–592. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Oleski J, Bodenlos JS, Ma Y. The sunless study: a beach randomized trial of a skin cancer prevention intervention promoting sunless tanning. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(9):979. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer JA, Slymen DJ, Clapp EJ, et al. Long-term maintenance of a successful occupational sun safety intervention. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(1):88–89. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Report on Carcinogens, 13th Edition. National Toxicology Program. 2011. http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/roc/twelfth/roc12.pdf#search=carcinogens.

- 17.Diepgen TL, Fartasch M, Drexler H, Schmitt J. Occupational skin cancer induced by ultraviolet radiation and its prevention. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(Suppl 2):76–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh HK, Kligler BE, Lew RA. Sunlight and cutaneous malignant melanoma: evidence for and against causation. Photochem Photobiol. 1990;51(6):765–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kricker A, Armstrong BK, English DR, Heenan PJ. Does intermittent sun exposure cause basal cell carcinoma? A case–control study in Western Australia. Int J Cancer. 1995;60(4):489–494. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia . Primary prevention of skin cancer in Australia: report of the Sun Protection working party. Australian Government Publishing Service: Sydney; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(13):975–983. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman KJ, Bible ML, London S, Mack TM. Proportional melanoma incidence and occupation among white males in Los Angeles County (California, United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6(5):451–459. doi: 10.1007/BF00052186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walter SD, King WD, Marrett LD. Association of cutaneous malignant melanoma with intermittent exposure to ultraviolet radiation: results of a case–control study in Ontario. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(3):418–427. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beral V, Robinson N. The relationship of malignant melanoma, basal and squamous skin cancers to indoor and outdoor work. Br J Cancer. 1981;44(6):886–891. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1981.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Cancer S . Cancer facts & figures 2014. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marghoob A, Kopf AW, Bart RS, et al. Risk of another basal cell carcinoma developing after treatment of a basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(1):22–28. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70003-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karagas MR, Stukel TA, Greenberg ER, Baron JA, Mott LA, Stern RS. Risk of subsequent basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin among patients with prior skin cancer. Skin Cancer Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1992;267(24):3305–3310. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03480240067036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Essers B, Nieman F, Prins M, Smeets N, Neumann H. Perceptions of facial aesthetics in surgical patients with basal cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(9):1209–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(3):490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg CA, Greenland P, Khandekar J, Loar A, Ascensao J, Lopez AM. Association of nonmelanoma skin cancer with second malignancy. Cancer. 2004;100(1):130–138. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahn HS, Tatham LM, Patel AV, Thun MJ, Heath CW., Jr Increased cancer mortality following a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA. 1998;280(10):910–912. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.10.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salas R, Mayer JA, Hoerster KD. Sun-protective behaviors of California farmworkers. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(12):1244–1249. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000177080.58808.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duffy SA, Choi SH, Hollern R, Ronis DL. Factors associated with risky sun exposure behaviors among operating engineers. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55(9):786–792. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanh TT, Hill PS, Kay BH, Quy TM. Development of a framework for evaluating the sustainability of community-based dengue control projects. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(2):312–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savaya R, Spiro S, Elran-Barak R. Sustainability of social programs a comparative case study analysis. Am J Eval. 2008;29(4):478–493. doi: 10.1177/1098214008325126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green LW, McAlister AL. Macro-intervention to support health behavior: some theoretical perspectives and practical reflections. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(3):322–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. Vol 5th. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fennell ML. Synergy, influence, and information in the adoption of administrative innovations. Acad Manag J. 1984;27(1):113–129. doi: 10.2307/255960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howell JM, Higgins CA. Champions of technological innovations. Adm Sci Q. 1990;35(2):317–341. doi: 10.2307/2393393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheirer MA. The life cycle of an innovation: adoption versus discontinuation of the fluoride mouth rinse program in schools. J Health Soc Behav. 1990;31(2):203–215. doi: 10.2307/2137173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hutchinson JR, Huberman M. Knowledge dissemination and use in science and mathematics education: a literature review. J Sci Educ Technol. 1994;3(1):27–47. doi: 10.1007/BF01575814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.August GJ, Bloomquist ML, Lee SS, Realmuto GM, Hektner JM. Can evidence-based prevention programs be sustained in community practice settings? The early risers’ advanced-stage effectiveness trial. Prev Sci. 2006;7(2):151–165. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0024-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith DW, Redican KJ, Olsen LK. The longevity of growing healthy: an analysis of the eight original sites implementing the school health curriculum project. J Sch Health. 1992;62(3):83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1992.tb06022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rabin BA, Glasgow RE, Kerner JF, Klump MP, Brownson RC. Dissemination and implementation research on community-based cancer prevention: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):443–456. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Authors. Sustained impact of an occupational sun safety program 5–7 years on. Invited abstract presented at: UV Radiation: Effects on Human Health and the Environment Workshop; Auckland, New Zealand, 2014.

- 47.Fixsen DL, Blase KA, Naoom SF, Wallace F. Core implementation components. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009;19(5):531–540. doi: 10.1177/1049731509335549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sinclair C, Foley P. Skin cancer prevention in Australia. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(s3):116–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scott EJ, Dimairo M, Hind D, et al. “Booster” interventions to sustain increases in physical activity in middle-aged adults in deprived urban neighbourhoods: internal pilot and feasibility study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(129):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu L, Forbes A, While A. Patients’ experience of a telephone booster intervention to support weight management in type 2 diabetes and its acceptability. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16(4):221–223. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.004016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bauer JE, Hyland A, Quiang L, Steger C, Cummings KM. A longitudinal assessment of the impact of smoke-free worksite policies on tobacco use. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(6):1024–1029. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Engbers LH, van Poppel MN, Chin A, Paw MJM, van Mechelen W. Worksite health promotion programs with environmental changes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(1):61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boehmer TK, Luke DA, Haire-Joshu DL, Bates HS, Brownson RC. Preventing childhood obesity through state policy: predictors of bill enactment. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(4):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Floyd MF, Crespo CJ, Sallis JF. Active living research in diverse and disadvantaged communities stimulating dialogue and policy solutions. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(4):271–274. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grunbaum JA, Rutman SJ, Sathrum PR. Faculty and staff health promotion: results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2000. J Sch Health. 2001;71(7):335–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb03512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fuemmeler BF, Baffi C, Masse LC, Atienza AA, Evans WD. Employer and healthcare policy interventions aimed at adult obesity. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shain M, Kramer DM. Health promotion in the workplace: framing the concept; reviewing the evidence. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(7):643–648. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.013193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.The Cancer Council of New South Wales and Union Safe . Sun safety at work: policy on protection from ultraviolet radiation for outdoor workers. Sydney: The Cancer Council of New South Wales and Union Safe; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 59.The Cancer Council of Victoria. Skin cancer and outdoor work: a guide for employers. http://www.cancer.org.au/content/pdf/PreventingCancer/BeSunsmart/Skincanceroutdoorworkbooklet.pdf. Published January 2007. Accessed February 9, 2015.

- 60.Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety. Skin cancer and sunlight. http://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/diseases/skin_cancer.html. Published April 2, 2014. Accessed February 9, 2015.

- 61.California Department of Public Health. Outdoor-based business: sun protection policy guidelines. http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/SkinCancer/Documents/KitsOutdoor-PolicyGuidelines.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2015.

- 62.Occupational Safety & Health Administration. Protecting yourself in the sun. OSHA-3166-06R. www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3166.pdf. Published 2003. Accessed February 5, 2015.

- 63.Wallis A, Andersen P, Buller D, et al. Adoption of sun safe work place practices by local governments. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Heany CA, Goldenhar LM. Worksite health programs: working together to advance employee health. Health Educ Q. 1996;23(2):133–136. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Outdoor Industry Association. The outdoor recreation economy. http://www.asla.org/uploadedFiles/CMS/Government_Affairs/Federal_Government_Affairs/OIA_OutdoorRecEconomyReport2012.pdf. Updated 2012. Accessed January 31, 2015.

- 66.Blumthaler M, Ambach W. Human ultraviolet radiant exposure in high mountains. Atmos Environ. 1988;22(4):749–753. doi: 10.1016/0004-6981(88)90012-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kerr JB. Understanding the factors that affect surface ultraviolet radiation. Opt Eng. 2005;44(4):041002. doi: 10.1117/1.1886817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reiter R, Munzert K, Sladovic R. Results of 5-year concurrent recording of global, diffuse, and UV radiation at three levels in the Northern Alps. Theor Appl Climatol. 1982;30(1–2):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Siani AM, Casale GR, Diemiz H, et al. Personal UV exposure in high albedo alpine sites. Atmos Chem Phys. 2008;8(14):3749–3760. doi: 10.5194/acp-8-3749-2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Bajdik CD, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentary factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer: I. Basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131(2):157–163. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1995.01690140041006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Buller DB, Cokkinides V, Hall HI, et al. Prevalence of sunburn, sun protection, and indoor tanning behaviors among Americans: systematic review from national surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 Suppl 1):114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stock ML, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, et al. Sun protection intervention for highway workers: long-term efficacy of UV photography and skin cancer information on men’s protective cognitions and behavior. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(3):225–236. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9151-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coups EJ, Manne SL, Heckman CJ. Multiple skin cancer risk behaviors in the U.S. population. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ski Area Management. 2014 salary survey. SAM Web site. http://www.saminfo.com/article/2014-salary-survey. Updated 2014. Accessed February 9, 2015.