Basic research to understand the mechanisms of normal human functioning has been called “the engine of discovery,” driving innovation and underlying many therapeutic breakthroughs. But in order for basic research findings to inform therapeutic interventions, those findings need to be translated and tested in a clinical context. The challenges of translating basic findings into clinical care are well documented, including in the high-profile 2001 Institute of Medicine report that described the “quality chasm” between scientific knowledge and quality clinical care [1].

Since this landmark report, many institutes at the NIH have developed behavioral and social science initiatives to support translational research relevant to their individual missions. In 1992, The National Institute on Aging (NIA) established the Roybal Centers for Translational Research on Aging, with the explicit goal of translating basic behavioral and social research findings into programs and practices that will improve the lives of older people and the capacity of institutions to adapt to societal aging. Support for the Roybal Centers continues, with a significant expansion of the program in 2009. In 2001, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) developed a stage model of behavioral therapy development, adapted from the phases of medications development, to support translational research in drug abuse treatment [2]. In 2009, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), in partnership with several other institutes, launched a program to support translational research on obesity called the Obesity-Related Behavioral Intervention Trials (ORBIT) program. These translational programs, and others like them across the NIH, have led to important advances for their respective communities.

Taking a closer look at some of those advances, it becomes clear that researchers working in different health areas are focusing on some of the same basic behavioral or social processes and are working in parallel to translate those basic findings into clinical interventions. Warren Bickel and colleagues [3] identify one such basic behavioral process called temporal discounting—the devaluation of a reward as a function of the delay until its receipt—and propose that it may be a trans-disease process. The evidence seems to support this proposal, with higher-than-normal temporal discounting rates being associated with a range of problematic health behaviors and conditions, including alcohol and substance abuse, psychiatric disorders, obesity, cognitive decline, and lower rates of recommended cancer screening, preventive dental visits, cholesterol testing, flu vaccination, and safer sexual behavior [4].

ESTABLISHING THE NIH COMMON FUND SCIENCE OF BEHAVIOR CHANGE INITIATIVE

In cases where a behavioral or social process seems relevant across multiple health conditions or behaviors, it would be ideal if research to translate common processes into clinical interventions for different conditions could contribute to a cumulative body of evidence. In 2008, the NIH Common Fund, administered by the Office of the NIH Director, provided an opportunity for NIH institutes and centers to work together to facilitate a cumulative, unified science of behavior change. Led by co-chairs from NIA (Richard Hodes, Director; Richard Suzman, Division Director) and the National Institute on Nursing Research (NINR; Patricia Grady, Director), the Science of Behavior Change (SOBC) working group was established. With support from the NIH Common Fund, the SOBC working group solicited recommendations from a wide range of experts on how to create a unified science of behavior change. Among the most consistent recommendations was the need for a focus on behavioral and social causal mechanisms, not just in the basic science laboratory, but also in clinical intervention development research.

During its first 5-year phase, the Science of Behavior Change initiative developed funding opportunities and hosted science meetings and symposia, to identify successful strategies for integrating tests of basic causal mechanisms into intervention studies. One challenge was to identify mechanisms (i.e., behavior change targets) that may be common to multiple health conditions. Results from funded projects, as well as SOBC-sponsored meetings, identified three broad classes of behavior change targets with greatest potential: targets broadly classified as self-regulation, stress reactivity and stress resilience, and interpersonal and social processes. In addition, activities during SOBC’s first phase highlighted the need to develop reliable and valid ways to measure whether targets have been engaged, either with experimental manipulations or interventions. These foundational activities informed the next phase of SOBC initiatives, which can be summarized as promoting an experimental medicine approach to behavior change research.

AN EXPERIMENTAL MEDICINE APPROACH TO BEHAVIOR CHANGE RESEARCH

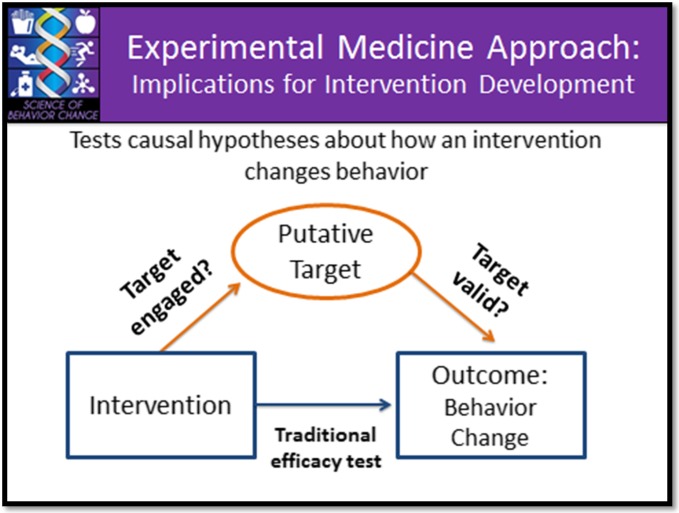

The experimental medicine approach involves four steps: (1) identifying an intervention target, (2) developing assays (measures) to permit verification of the target, (3) engaging the target through experimentation or intervention, and (4) testing the degree to which target engagement produces the desired behavior change.

The figures below illustrate the experimental medicine approach, and its implications for intervention development (Fig. 1) and measures development (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

The experimental medicine approach to intervention development involves testing both whether the intervention engages the intended target and whether target engagement leads to the desired behavior change outcome

Fig. 2.

The experimental approach requires valid measurement of target engagement, ideally with measures or assays at multiple levels

The experimental medicine approach is different from how the majority of behavior change research is typically conducted, where in general, basic mechanistic research to understand how and why behavior change occurs tends to be conducted separately from clinical behavior change intervention research. While behavioral intervention development is usually grounded in earlier research that suggests potential targets or change mechanisms (e.g., factors that are associated with the development or maintenance of the behavior of interest), intervention research often focuses on the efficacy or effectiveness of interventions on some health outcome, rather than testing explicitly whether an intervention worked by engaging a specific hypothesized change mechanism. The focus on specific health outcomes, without testing change-mechanism hypotheses, makes it challenging to apply advances in one health behavior or condition to other areas of health. Omitting tests of causal mechanisms from intervention studies also can lead to costly inefficiencies, requiring new and expensive clinical trials to test even the most incremental changes in intervention strategy or end-user population. The activities of the first phase of SOBC suggest that an experimental medicine approach may help overcome these challenges, facilitating the translation of advances in basic science to clinical intervention and translation of findings in one health condition to others.

SOBC-2 ESTABLISHES AN EXPERIMENTAL MEDICINE CONSORTIUM

January, 2015, marked the official launch of the next 5-year phase of the SOBC initiative. The first initiatives from the continuing SOBC program are four funding opportunities intended to establish a consortium focused on developing the tools required to implement an experimental medicine approach to behavior change research. Three of these funding opportunities are requests for applications (RFAs) that call for teams of scientists to develop measures or assays that allow investigators to test whether behavioral or social interventions engaged their intended targets (i.e., produced effects via the putative mechanism). These three RFAs each focused on one of the broad class of targets identified as most promising by activities in the first phase of SOBC: self-regulation, stress reactivity and stress resilience, and interpersonal and social processes. A fourth RFA supports a resource and coordinating center, responsible for maximizing collaborations across teams working on similar processes and ensuring dissemination of experimental medicine tools to the broader research community. Although the deadline for these particular funding opportunities has passed, program directors and scientists across the NIH are dedicated to promoting research that adopts an experimental medicine approach to health behavior change and to facilitating collaborations among basic and applied scientists that would promote such research. The SOBC working group encourages behavior change researchers all along the translational pipeline to explore the mission and activities of the SOBC initiative and to look for additional opportunities to get involved over the next 5 years.

References

- 1.Lamb S, Greenlick MR, McCarty D, editors. Institute of medicine’s crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: getting started and moving on from stage I. Clin Psych Sci Pract. 2005;8:133–142. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.8.2.133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Koffarnus NM, Gatchalian KM. Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a trans-disease process contributing to addiction and other disease-related vulnerabilities: emerging evidence. Pharm Ther. 2012;134:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Story GW, Vlaev I, Seymour B, Darzi A, Dolan RJ. Does temporal discounting explain unhealthy behavior? A systematic review and reinforcement learning perspective. Fron Beh Neurosci. 2014;8:1–20. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]