Abstract

AIM: To investigate the expression of metallothioneins (MTs), which were recently thought to have close relationship with tumors, in human hepatocellular carcinoma.

METHODS: Histological specimens of 35 cases of primary human hepatocellular carcinoma with para-neoplastic liver tissue and 5 cases of normal liver were stained for MTs with monoclonal mouse anti-MTs serum (E9) by the immunohistochemical ABC technique.

RESULTS: MTs were stained in the 35 cases of HCC, including 6 cases negative (17.1%), 23 weakly positive (65.7%), and 6 strongly positive (17.1%). But MTs were stained strongly positive in all the five cases of normal liver and 35 cases of para-neoplastic liver tissue. The differences of MTs expression between HCC and normal liver tissue or para-neoplastic liver tissue were highly significant (P < 0.01). The rate of MTs expression in HCC grade I was 100 percent, higher than that in grade II (81%) and grade III and IV (78%). But the differences were not significant (P > 0.05). No obvious correlations between MTs expression in HCC and tumor size, clinical stage or serum alpha fetoprotein concentration were found (P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Decrease of MTs expression in HCC may play a role in carcinogenesis of HCC. MTs are stained heterogenously in HCC. We can choose the anticancer agents according to the MTs concentration in HCC, which may improve the results of chemotherapy for HCC.

INTRODUCTION

Metallothioneins (MTs) are a family of low-molecular weight, cysteine rich proteins which are widely distributed in various species. MTs are thought to be involved in heavy-metal detoxification, intracellular trace elements storage and scavenging free radicals. Recently, emerging data suggest that MTs have close relationship with tumors. They might play important roles in carcinogenic and apoptotic process and differentiation of tumor cells[1-12]. And besides, MTs are attributed to affording tumor cells resistance to some important chemotherapeutic agents[13]. This study is aimed to examine MTs expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and to explore its biological and clinical significance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical material

The clinical information and pathological specimens from 35 patients, whose liver tumors were removed at XiangYa Hospital from 1998 to 2000, were analyzed. All the cases were reviewed to confirm the pathological diagnosis of HCC. All the 35 specimens of HCC contained their corresponding para-neoplastic liver tissue. The ages of patients ranged from 31 to 71 years, with a mean ± SD of 49.92 ± 9.32 years. 33 were men and 2 women. According to Edmonson pathologic grading, there were 5 cases of grade I, 16 grade II and 14 grade III-IV. According to the clinical staging of UICC, there were 22 cases of stage II, 5 stage III and 8 stage IV. All the cases had positive HBsAg. This study also included 5 cases of normal liver tissue, around the hepatic hemangioma excised also in XiangYa Hospital.

Immunohistochemical determination of MTs

All the specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometre thick sections were cut from the tissue blocks, mounted onto glass slides and were used for staining. ABC technique was adopted. Briefly, 5 μm sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated first, and then were immersed in 3% H2O2 with methanol for 30 min to remove the endogenous peroxidase activity. Sections were further incubated with 10% normal goat serum for 1 hour, followed by incubation with monoclonal mouse anti-MTs serum (E9) (1:50) at 4 °C overnight. The sections were then washed in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) (0.01M, pH7.2) and they were sequentially incubated with: (1) biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG, and (2) avidin-biotin horseradish peroxidase complex following the manufacturers` instruction (ABC kit, BOSTER Ltd. Wuhan). Staining was developed by immersing slides in 0.05% 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) with 0.33% hydrogen peroxide. All slides were counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted. PBS substituted for the primary antibody was used as the negative control. According to the proportion of positively stained cells, a grade was given from I to III, with Grade I indicating less than one third of cells stained and Grade III indicating more than two thirds of cells stained. The intensity of MTs expression was also graded and given a grade for 0 to II, with Grade 0 indicating no staining, and Grade II indicating the greatest intensity of staining. A weighted score was then generated to semiquantify the MTs expression level in the tissue by multiplying the MTs intensity score with the proportion of the positively stained tumors cells. A weighted score of zero indicated no MTs staining (-), more than 3 indicated strongly positive MTs staining (++) and that between zero and 3 indicated weakly positive MTs staining (+)[14].

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed semiquantitively. Ridit test was used to determine the difference. The results were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

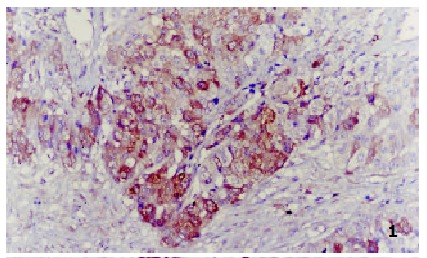

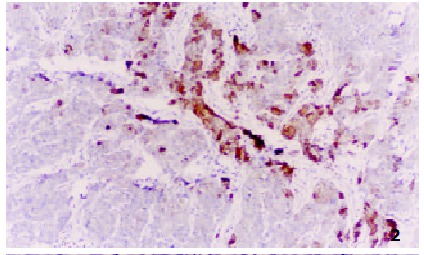

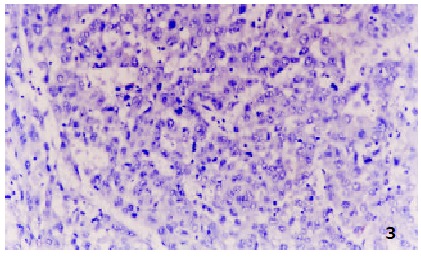

All negative control slides showed no staining for MTs, demonstrating the specificity of the monoclonal antibody E9. Strongly positive MTs immunoreactivity was observed in all the five control normal liver sections, mostly in cytoplasm with a few in nucleus. All the surrounding connective tissues, including blood vessels and bile ducts were negative for MTs staining. Twenty-nine of 35 HCC showed positive MTs staining, including 6 strongly positive (17.1%) (Figure 1), 23 weakly positive (65.7%) (Figure 2) and 6 negative (17.1%) (Figure 3). MTs expressed strongly in all the para-neoplastic liver tissue. The differences of MTs expression between HCC and para-neoplastic liver tissue or normal liver tissue were highly significant (Table 1, P < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Strongly positive staining of MTs in hepatocellular carcinoma ABC × 200.

Figure 2.

Weakly positve staining of MTs in hepatocellular carcinoma ABC × 200.

Figure 3.

Negative staining of MTs in hepatocellular carcinoma ABC × 200.

Table 1.

Levels of MTs expression in HCC, para-neoplastic and normal liver tissues

P < 0.01, vs HCC

The positive ratio of MTs expression in grade I of HCC was 100%, higher than that in grade II (81%) and grade III and IV (78%). But the differences did not reached the level of significance (P > 0.05). In addition, the differences of MTs expression in HCC with different clinical stages, tumor sizes and serum alpha fetoprotein concentration were not significant either (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between MTs expression and clinicopathologic data of HCC

|

MTs score |

||||

| n | - | + | ++ | |

| Pathologic grade | ||||

| Grade I | 5 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Grade II | 16 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Grade III-IV | 14 | 3 | 10 | 1 |

| Clinical stage | ||||

| Stage I-II | 22 | 5 | 14 | 3 |

| Stage III-IV | 13 | 1 | 9 | 3 |

| Size (mm) | ||||

| ≤ 50 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 0 |

| > 50 | 26 | 3 | 17 | 6 |

| AFP concentration (ng/mL) | ||||

| ≤ 50 | 13 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| > 50 | 22 | 3 | 17 | 2 |

DISCUSSION

Recently, much attention was paid to the association between MTs and tumors. Available information suggested that MTs might play important roles in carcinogenic and apoptotic process of some tumors[1-13,15-20]. Using immunohistochemical staining method, MTs have been localized intensively in various types of human tumors in organs and tissues such as skin, kidneys, prostate, testes, gallbladder, colon, breast and endometrium[15-32]. It was mainly attributed to loss of control of the transcription of MTs genes, which was caused by activation of some oncogenes, such as Ha-ras, in tumor cells[33]. However, the potential roles of MTs in carcinogenic process was not yet well understood[34]. Several pieces of evidence suggested that MTs could combine with and sequester those carcinogenic substances in cells. When the cells were invaded by the carcinogenic substances, many protective processes were activated to scavenge those substances. Elevation of MTs may be one of the processes[35-40]. But not all the tumors contained elevated MTs[41], such as HCC. In this study, the authors have detected MTs expression in 35 cases of HCC and their corresponding para-neoplastic liver tissue and 5 cases of normal liver tissue. The results showed that MTs were strongly positive in all the normal liver tissue and para-neoplastic liver tissue, considerabely higher than those in HCC tissue, which conformed to the finding of Deng[14]. MTs are functional proteins in liver tissue, which is involved in heavy metal detoxification. The down-regulation of MTs expression in HCC suggested that these cells probably have different proliferative or differentiated characteristics as compared to the surrounding normal hepatocytes, and MTs may be a marker of hepatocellular differentiation. In addition, this down-regulation might play a role in carcinogenic process of HCC. MTs are one of the most important intracellular free radicals scavengers, and oxidateve injury may be one of the most important causes of gene mutation. As a result, this down-regulation of MTs expression might cause accretion of oxidative in cells, which might lead to activating some oncogenes or inactivating some tumor-suppressor genes[38-40].

Several other studies have also shown that the MTs levels may be related to the degree of differentiation of tumor cells. For example, using immunohistochemical staining method, a distinct difference between seminoma and nonseminoma of human testicular tumors was found[21]. Well-differentiated seminoma showed litter or no staining for MTs while less differentiated nonseminoma (embryonic carcinoma) strongly expressed MTs. MTs overexpression in human breast carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, esophageal carcinoma, osteosarcoma, endometrial carcinoma and melanoma tended to correlate with poor prognosis[19,24-42]. In this study, the positive rate of MTs expression in grade I of HCC is 100 percent, higher than grade II (81%) and grade III and IV (78%), but the differences have not reach the level of significance. So the genuine relationship between MTs and differentiation of HCC remains to be further investigated.

Resistance to antineoplastic agents is one of the major obstacles to curative therapy of HCC. The development of this resistance has been explained by several factors, including increased DNA repair processes and expression of MDR gene[43]. In 1998, Kelley et al[44] found that tumor cell lines with acquired resistance to the antineoplastic agent cisplatinum overexpressed MTs and demonstrated cross-resistance to other eletrophilic anticancer agents, such as melphalan, chlorambucil. Furthermore, cells transfected with bovine papilloma virus expression vectors containing DNA encoding human MTs were resistant to electrophilic anticancer drugs mentioned above, but not to 5-fluorouracil or vincristine. Thus, overexpression of MTs represented one mechanism of resistance to a subset of clinically important anticancer drugs. Those results were substantiated by a series of other experiments[45-49]. The mechanism that MTs were involved in drug resistance might be that MTs in tumor cells could combine with those electrophilic anticancer drugs and prevent them from acting on their targets, such as DNA. In this study, we have shown that MTs expressed heterogenously in HCC, including 6 cases with strong expression, 23 with weak expression and 6 negative. The authors therefore assumed that resistance to electrophilic antineoplastic agents in a portion of HCC might be related to MTs expression in tumor tissue.

Thus, anticancer agents could be chosen according to the levels of MTs expression in order to improve the efficiency of chemotherapy for HCC. For example, electrophilic antineoplastic agents were used in the treatment of HCC without MTs and non-electrophilic antineoplastic agents were used in HCC containing high levels of MTs. However, the effect of this design remains to be determined. Recently, a gene therapy by transactivating MTs to the chemoresistant tumour cells to reverse the chemoresistance have been reported[50]. In the near future, oncologists are really able to use the knowledge about MTs in overcoming cancer.

The down-regulation of MTs expression in HCC might play roles in carcinogenesis of HCC, but its biological and clinical significance is still uncertain. A further understanding of the association between MTs expression and resistance to anticancer agents should facilitate the chemotherapy for HCC.

Footnotes

Edited by Zhang JZ

Supported by the Science Fund of Department of Science and Technology of Hunan Province, No.98ssy1008

References

- 1.Takaba K, Saeki K, Suzuki K, Wanibuchi H, Fukushima S. Significant overexpression of metallothionein and cyclin D1 and apoptosis in the early process of rat urinary bladder carcinogenesis induced by treatment with N-butyl-N- (4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine or sodium L-ascorbate. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:691–700. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jayasurya A, Bay BH, Yap WM, Tan NG, Tan BK. Proliferative potential in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: correlations with metallothionein expression and tissue zinc levels. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1809–1812. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.10.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiura T, Khalid H, Yamashita H, Tokunaga Y, Yasunaga A, Shibata S. Immunohistochemical analysis of metallothionein in astrocytic tumors in relation to tumor grade, proliferative potential, and survival. Cancer. 1998;83:2361–2369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel-Mageed AB, Agrawal KC. Activation of nuclear factor kappaB: potential role in metallothionein-mediated mitogenic response. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2335–2338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aloia TA, Harpole DH, Reed CE, Allegra C, Moore MB, Herndon JE, D'Amico TA. Tumor marker expression is predictive of survival in patients with esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:859–866. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02838-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jayasurya A, Bay BH, Yap WM, Tan NG. Correlation of metallothionein expression with apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1198–1203. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang XH, Takenaka I. Incidence of apoptosis and metallothionein expression in renal cell carcinoma. Br J Urol. 1998;81:9–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph MG, Banerjee D, Kocha W, Feld R, Stitt LW, Cherian MG. Metallothionein expression in patients with small cell carcinoma of the lung: correlation with other molecular markers and clinical outcome. Cancer. 2001;92:836–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hishikawa Y, Kohno H, Ueda S, Kimoto T, Dhar DK, Kubota H, Tachibana M, Koji T, Nagasue N. Expression of metallothionein in colorectal cancers and synchronous liver metastases. Oncology. 2001;61:162–167. doi: 10.1159/000055368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebert MP, Günther T, Hoffmann J, Yu J, Miehlke S, Schulz HU, Roessner A, Korc M, Malfertheiner P. Expression of metallothionein II in intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1995–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin R, Chow VT, Tan PH, Dheen ST, Duan W, Bay BH. Metallothionein 2A expression is associated with cell proliferation in breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:81–86. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan Y, Sinniah R, Bay BH, Singh G. Metallothionein expression and nuclear size in benign, borderline, and malignant serous ovarian tumours. J Pathol. 1999;189:60–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<60::AID-PATH387>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherian MG, Howell SB, Imura N, Klaassen CD, Koropatnick J, Lazo JS, Waalkes MP. Role of metallothionein in carcinogenesis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1994;126:1–5. doi: 10.1006/taap.1994.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng DX, Chakrabarti S, Waalkes MP, Cherian MG. Metallothionein and apoptosis in primary human hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 1998;32:340–347. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tüzel E, Kirkali Z, Yörükoglu K, Mungan MU, Sade M. Metallothionein expression in renal cell carcinoma: subcellular localization and prognostic significance. J Urol. 2001;165:1710–1713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishii K, Usui S, Yamamoto H, Sugimura Y, Tatematsu M, Hirano K. Decreases of metallothionein and aminopeptidase N in renal cancer tissues. J Biochem. 2001;129:253–258. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naito S, Koga H, Yokomizo A, Sakamoto N, Kotoh S, Nakashima M, Kiue A, Kuwano M. Molecular analysis of mechanisms regulating drug sensitivity and the development of new chemotherapy strategies for genitourinary carcinomas. World J Surg. 2000;24:1183–1186. doi: 10.1007/s002680010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssen AM, van Duijn W, Oostendorp-Van De Ruit MM, Kruidenier L, Bosman CB, Griffioen G, Lamers CB, van Krieken JH, van De Velde CJ, Verspaget HW. Metallothionein in human gastrointestinal cancer. J Pathol. 2000;192:293–300. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH712>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin R, Bay BH, Chow VT, Tan PH, Lin VC. Metallothionein 1E mRNA is highly expressed in oestrogen receptor-negative human invasive ductal breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:319–323. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ioachim EE, Kitsiou E, Carassavoglou C, Stefanaki S, Agnantis NJ. Immunohistochemical localization of metallothionein in endometrial lesions. J Pathol. 2000;191:269–273. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH616>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chin JL, Banerjee D, Kadhim SA, Kontozoglou TE, Chauvin PJ, Cherian MG. Metallothionein in testicular germ cell tumors and drug resistance. Clinical correlation. Cancer. 1993;72:3029–3035. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931115)72:10<3029::aid-cncr2820721027>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuo T, Lo SK. Immunohistochemical metallothionein expression in thymoma: correlation with histological types and cellular origin. Histopathology. 1997;30:243–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.d01-603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shukla VK, Aryya NC, Pitale A, Pandey M, Dixit VK, Reddy CD, Gautam A. Metallothionein expression in carcinoma of the gallbladder. Histopathology. 1998;33:154–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zelger B, Hittmair A, Schir M, Ofner C, Ofner D, Fritsch PO, Böcker W, Jasani B, Schmid KW. Immunohistochemically demonstrated metallothionein expression in malignant melanoma. Histopathology. 1993;23:257–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goulding H, Jasani B, Pereira H, Reid A, Galea M, Bell JA, Elston CW, Robertson JF, Blamey RW, Nicholson RA. Metallothionein expression in human breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:968–972. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douglas-Jones AG, Schmid KW, Bier B, Horgan K, Lyons K, Dallimore ND, Moneypenny IJ, Jasani B. Metallothionein expression in duct carcinoma in situ of the breast. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uozaki H, Horiuchi H, Ishida T, Iijima T, Imamura T, Machinami R. Overexpression of resistance-related proteins (metallothioneins, glutathione-S-transferase pi, heat shock protein 27, and lung resistance-related protein) in osteosarcoma. Relationship with poor prognosis. Cancer. 1997;79:2336–2344. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970615)79:12<2336::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sens MA, Somji S, Garrett SH, Beall CL, Sens DA. Metallothionein isoform 3 overexpression is associated with breast cancers having a poor prognosis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:21–26. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61668-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jasani B, Schmid KW. Significance of metallothionein overexpression in human tumours. Histopathology. 1997;31:211–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.2140848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossen K, Haerslev T, Hou-Jensen K, Jacobsen GK. Metallothionein expression in basaloid proliferations overlying dermatofibromas and in basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang XH, Jin L, Sakamoto H, Takenaka I. Immunohistochemical localization of metallothionein in human prostate cancer. J Urol. 1996;156:1679–1681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giuffrè G, Barresi G, Sturniolo GC, Sarnelli R, D'Incà R, Tuccari G. Immunohistochemical expression of metallothionein in normal human colorectal mucosa, in adenomas and in adenocarcinomas and their associated metastases. Histopathology. 1996;29:347–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1996.tb01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt CJ, Hamer DH. Cell specificity and an effect of ras on human metallothionein gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3346–3350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdel-Mageed AB, Agrawal KC. Activation of nuclear factor kappaB: potential role in metallothionein-mediated mitogenic response. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2335–2338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ioachim EE, Goussia AC, Agnantis NJ, Machera M, Tsianos EV, Kappas AM. Prognostic evaluation of metallothionein expression in human colorectal neoplasms. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:876–879. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.12.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sutoh I, Kohno H, Nakashima Y, Hishikawa Y, Tabara H, Tachibana M, Kubota H, Nagasue N. Concurrent expressions of metallothionein, glutathione S-transferase-pi, and P-glycoprotein in colorectal cancers. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:221–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02236987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hishikawa Y, Koji T, Dhar DK, Kinugasa S, Yamaguchi M, Nagasue N. Metallothionein expression correlates with metastatic and proliferative potential in squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:712–720. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCluggage WG, Maxwell P, Hamilton PW, Jasani B. High metallothionein expression is associated with features predictive of aggressive behaviour in endometrial carcinoma. Histopathology. 1999;34:51–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossman TG, Goncharova EI. Spontaneous mutagenesis in mammalian cells is caused mainly by oxidative events and can be blocked by antioxidants and metallothionein. Mutat Res. 1998;402:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang B, Satoh M, Nishimura N, Suzuki JS, Sone H, Aoki Y, Tohyama C. Metallothionein deficiency promotes mouse skin carcinogenesis induced by 7, 12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4044–4046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duncan EL, Reddel RR. Downregulation of metallothionein-IIA expression occurs at immortalization. Oncogene. 1999;18:897–903. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Floriañczyk B, Grzybowska L. Metallothione in levels in cell fractions from breast cancer tissues. Acta Oncol. 2000;39:141–143. doi: 10.1080/028418600430680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu BH, Zhang RJ, Lu DD, Chen XD, Wang NJ. Expression of mdr1 gene coded pglycoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma and its dinical significance. Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 1998;6:783–785. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelley SL, Basu A, Teicher BA, Hacker MP, Hamer DH, Lazo JS. Overexpression of metallothionein confers resistance to anticancer drugs. Science. 1988;241:1813–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.3175622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kondo Y, Kuo SM, Watkins SC, Lazo JS. Metallothionein localization and cisplatin resistance in human hormone-independent prostatic tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1995;55:474–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyazaki H, Naitoh Y, Nakahashi Y, Yanagitani S, Kuno K, Ueno Y, Okajima A, Inoue K. Induction of metallothionein isoforms in rat hepatoma cells by various anticancer drugs. J Biochem. 1998;124:65–71. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shnyder SD, Hayes AJ, Pringle J, Archer CW. P-glycoprotein and metallothionein expression and resistance to chemotherapy in osteosarcoma. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:757–759. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moriyama-Gonda N, Igawa M, Shiina H, Wada Y. Heat-induced membrane damage combined with adriamycin on prostate carcinoma PC-3 cells: correlation of cytotoxicity, permeability and P-glycoprotein or metallothionein expression. Br J Urol. 1998;82:552–559. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kikuchi Y, Hirata J, Yamamoto K, Ishii K, Kita T, Kudoh K, Tode T, Nagata I, Taniguchi K, Kuwano M. Altered expression of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase, metallothionein and topoisomerase I or II during acquisition of drug resistance to cisplatin in human ovarian cancer cells. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1997;88:213–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1997.tb00368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vandier D, Calvez V, Massade L, Gouyette A, Mickley L, Fojo T, Rixe O. Transactivation of the metallothionein promoter in cisplatin-resistant cancer cells: a specific gene therapy strategy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:642–647. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.8.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]